ABSTRACT

The goal of this paper is to describe and analyze the relationship between ability tracking and student social trust, in the context of low-income students in developing countries. Drawing on the results from a longitudinal study among 1,436 low-income students across 132 schools in rural China, we found a significant lack of interpersonal trust and confidence in public institutions among poor rural young adults. We also found that slow-tracked students have a significantly lower level of social trust, comprised of interpersonal trust and confidence in public institutions, relative to their fast-tracked peers. This disparity might further widen the gap between relatively privileged students who stay in school and less privileged students who drop out of school. These results suggest that making high school accessible to more students may improve social trust among rural low-income young adults.

Introduction

Ability tracking, also known as streaming or ability grouping, describes the school or classroom practice under which students are sorted into different groups based on their prior academic performance, as measured by grades or standardized test scores (Trautwein, Lüdtke, Marsh, Köller, & Baumert, Citation2006).Footnote1 For example, fast-tracked students are those with higher academic achievement; in contrast, slow-tracked students are those with lower academic achievement (Trautwein et al., Citation2006). Ability tracking is one of the most common practices in secondary schools in developing countries (Arteaga & Glewwe, Citation2014; Banerjee & Duflo, Citation2011; Glewwe, Hanushek, Humpage, & Ravina, Citation2013; Hanushek & Wößmann, Citation2006). The impact of ability tracking on student outcomes is contentious in the education literature. Supporters of ability tracking suggest that tracking improves academic performance for all students, because course curriculum and teacher efforts can be better targeted to students’ different ability levels (e.g., Booij, Leuven, & Oosterbeek, Citation2017; Duflo, Dupas, & Kremer, Citation2011). Critics of ability tracking argue that these systems have negative impacts on slow-tracked students, by reducing positive peer effects, reducing student self-esteem, and inhibiting upward mobility for students of lower socioeconomic status (e.g., Hanushek & Wößmann, Citation2006).

Many studies have analyzed the impact of ability tracking on students’ academic performance, with mixed results (Duflo et al., Citation2011; Epple, Newlon, & Romano, Citation2002; Figlio & Page, Citation2002; Hoffer, Citation1992; Kulik & Kulik, Citation1982; Slavin, Citation1990; West & Wößmann, Citation2006). In a meta-analysis of 52 studies carried out in secondary schools in developed countries (primarily correlational studies), Kulik and Kulik (Citation1982) concluded that the average effect of ability tracking on student test scores is rather small. In contrast, in a recent experimental study conducted in Kenya in 121 primary schools, Duflo et al. (Citation2011) found that tracking students by their prior academic achievement over 18 months raised the scores of all students, even those assigned to lower achieving tracks.

While the literature is unclear about the effect of tracking on academic achievement, there is evidence that ability tracking can have negative effects on important non-cognitive outcomes in slow-tracked students. For example, prior studies have shown that the most significant consequence of being placed in the slow track is an increased risk of dropping out of school (Brown & Park, Citation2002; Filmer, Citation2000; McPartland, Citation1993; H. Wang et al., Citation2015). Slow-tracked students have also been shown to have elevated levels of psychological stress, such as anxiety and depression (Kokko, Tremblay, Lacourse, Nagin, & Vitaro, Citation2006; H. Wang et al., Citation2015). Other work documented that student self-esteem and confidence are significantly correlated with their position in the tracking system (Oakes, Citation1985; Van Houtte, Demanet, & Stevens, Citation2012). It has also been shown that slow-tracked students often become more aggressive, more impulsive, and exhibit more antisocial behavior than fast-tracked and non-tracked students (Kokko & Pulkkinen, Citation2000; Kokko et al., Citation2006).

We hypothesize that the social trust of students in different tracks may be impacted by the same mechanisms that drive the aforementioned negative non-cognitive outcomes in slow-tracked students. Social trust is generally understood as a set of values, faith, and confidence that we place in others or in public institutions, and which promotes collective action and civic engagement (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992; Burns, Kinder, & Rahn, Citation2003; Coleman, Citation1988; Putnam, Citation1993). Prior studies have argued that social trust manifests itself in individuals as a tight reciprocal relationship between levels of civic engagement, interpersonal trust, and other pro-social attitudes (Bourdieu & Wacquant, Citation1992; Brehm & Rahn, Citation1997; Putnam, Citation1993). Social trust has been shown to be an important contributor to a country’s development (Woolcock, Citation1998). At a microlevel, social trust reduces transaction costs (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, & Vishny, Citation1997; Zak & Knack, Citation2001), improves contract enforcement, and facilitates credit for individual investors (Knack & Keefer, Citation1995). At a macrolevel, social trust fosters social cohesion – which may improve the efficiency of public administration (Inglehart, Citation1999; Putnam, Citation1993).

Prior work has established a positive relationship between educational attainment and social trust. Education transmits social trust in the form of social rules, trust, and norms (Cantoni & Yuchtman, Citation2013; Helliwell & Putnam, Citation2007; Leigh, Citation2006). For example, in developed countries such as the United States, the UK, and Australia, education promotes greater civic participation, larger and more diverse social networks, and higher levels of social trust (Baum, Parker, Modra, Murray, & Bush, Citation2000; Hall, Citation1999; Halpern, Citation2005; Y. Li, Pickels, & Savage, Citation2005).

What has not been examined, to our knowledge, is whether student social trust might also be influenced by their differential treatment in schools, particularly in those that use ability tracking. Early studies (since the 1970s) have argued that the day-to-day experiences of students in tracked education systems could promote very different social attitudes and expectations between groups (Bernstein, Citation1975; Bowles & Gintis, Citation1976; Oakes, Citation1982). In competitive education systems, if a student is placed in the slow track, s/he is often assigned less effective or less motivated teachers (Klusmann, Kunter, Trautwein, Lüdtke, & Baumert, Citation2008; Talbert & Ennis, Citation1990), are more likely to be ignored by their teachers (Hallinan, Citation1996; Kerckhoff & Glennie, Citation1999), are reprimanded more often or more harshly than fast-tracked students (Shi et al., Citation2015), and are sometimes even encouraged to drop out of school by their teachers (Bowditch, Citation1993). Slow-tracked students may thus begin to have lower levels of trust in others and confidence in the institutions that they are attending. By contrast, if a student is placed in the fast track, given more attention, and treated preferentially by teachers, peers, and parents, s/he may hold more favorable values towards school, peers, and even social institutions around them (Fortin, Marcotte, Potvin, Royer, & Joly, Citation2006; Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, Citation1997; Kraft & Rogers, Citation2015; Vickers, Citation1994).

Despite the prevalence of ability tracking in developing countries, and its important role in student outcomes, to our knowledge, there has been almost no study about ability tracking and student social trust in a developing country context. Few quantitative studies have rigorously analyzed how ability tracking may affect the social trust of students ‒ whether slow or fast tracked. Our study therefore aims to fill gaps in the literature on understanding the relationship between ability tracking and student social trust in developing countries by examining a large longitudinal sample of rural, low-income young students. To meet this goal, we have three specific objectives. First, we aim to measure levels of social trust in low-income students who recently finished attending (or dropped out of) junior high school. Second, we compare levels of social trust between fast- and slow-tracked junior high school students. Third, we discuss the implications on social trust of having students go through a tracking system.

In this paper, we focus on the context of rural China. Studying the relationship between secondary schooling experience and social trust formation in rural China may provide a unique opportunity for several reasons. First, because 70% of school-aged children in China grow up in rural areas, investigating rural students’ social trust greatly informs our understanding of China’s future labor force (Khor et al., Citation2016). Second, ability tracking and high-stakes matriculation exams have been prevalent in China’s secondary education system for many years. The rigidity of China’s fast-tracked educational system, as well as the high social value placed on academic achievement in Chinese culture, may be particularly likely to create different environments for fast-tracked and slow-tracked students (and the differences in the experiences that students in different tracks have might lead to different levels of social trust).

However, it is important to note that there are other effects at work in schools that may also influence student social trust. In particular, there is evidence that social trust can vary on the basis of their socioeconomic status (SES; Grootaert, Citation2001; Narayan, Citation1997). Past research has shown that low-SES students also tend to have lower levels of social trust. Because our research mainly focuses on the relationship between ability tracking and social trust, we sought to reduce this complexity by focusing on a single socioeconomic group. Consequently, in the rest of this paper, we have chosen to look at low-income students within tracked schools, as less parental support and lower parental educational backgrounds may make them particularly vulnerable to the negative effects of being slow tracked (Brown & Park, Citation2002; Grootaert, Citation2001; Tarabini, Citation2010; Tilak, Citation2001; Wilson, Citation1996). By limiting our sample to low-income students, we expected that differences in SES across students will not bias our results.

Ability tracking in China’s rural junior high schools

Ability tracking was long the norm in junior high schools in China (Cheung & Rudowicz, Citation2003; Ding & Lehrer, Citation2007; Lai, Citation2007; Shanmai Wang, Citation2008). However, in recent years, international opinion turned against ability tracking for the youngest age groups (Fiedler, Lange, & Winebrenner, Citation2002). Similar sentiments also emerged in China. In 2006, to fight the perceived negative effects of tracking on younger children, China’s central government explicitly prohibited junior high schools and primary schools from tracking students according to their ability (Ministry of Education, Citation2006). According to policy, formal tracking is only allowed at the level of high school or above. No junior high school teachers or principals are allowed to group students according to their ability.

In spite of this policy, the incentives given to junior high school principals and teachers strongly encourage ability tracking. This is particularly true in rural secondary schools, where teachers’ and school principals’ salaries are rather low and partially determined by performance, often measured as high school admission rates (X. Wang et al., Citation2011; Xu, Hu, & Mao, Citation2009). Studies have shown that reputations and prospects for officials, principals, and teachers in China are almost exclusively determined by their ability to cultivate high-achieving students who are likely to gain admission into prestigious high schools and universities (Tsang, Citation2000). The challenge for students (and their teachers) is fully focused on a period of time at the end of junior high school, during which students take a high-stakes exam that determines high school admission. The odds of success are low. For instance, recent studies have shown that in poor rural counties, less than half of junior high graduates are able to gain admission to high school (F. Li et al., Citation2017; Mo et al., Citation2013). Only students who are successful on this exam have any chance of charting a course towards the greater opportunity and social status offered by a college education (Loyalka et al., Citation2014; X. Wang, Liu, Zhang, Shi, & Rozelle, Citation2013; Ye, Citation2013).

As a result of this reality, principals and teachers are incentivized to focus their energies disproportionately on the best students through ability tracking. For example, on a day-to-day basis, ability tracking occurs when fast- and slow-tracked students are taught in different classrooms with different teachers. Within the same classroom, fast-tracked students may be moved to the front seats, and slow-tracked students may be forced to sit in the back. In China’s secondary schools, class size is often rather large (53 students per teacher on average; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Citation2012). Teachers seldom walk to the back of the classroom or pay attention to the slow-tracked students. Other studies have shown that teachers in Chinese schools spend more time with (Stevenson, Lee, & Chen, Citation1994; Xue & Ding, Citation2009); provide more tutoring for (Dang & Rogers, Citation2008; Lei, Citation2005; Tsang, Ding, & Shen, Citation2010; Zhang, Citation2013); give greater encouragement to (Lee, Yin, & Zhang, Citation2009; H. Wang et al., Citation2015); and generally provide a more supportive environment to (Tang, Citation1991) high-achieving students relative to their peers.

Low-performing students, by contrast, receive less attention. These students are often taught by less experienced teachers (H. Wang et al., Citation2015) and are given almost no encouragement from teachers or principal (Sangui Wang, Zeng, Shi, Luo, & Zhang, Citation2012; W. Yi, Citation2011). In rural schools where teaching styles are especially strict, qualitative research reveals that harsh physical punishment is commonplace for low-performing students (Shi et al., Citation2015). In the most extreme cases, slow-tracked students are actively encouraged to drop out of school to improve school’s testing statistics (D. Liu, Citation2014). Low-achieving students drop out of school at high rates (H. Wang et al., Citation2015) and have lower self-confidence and self-esteem (Cheng, Citation1997; Wong & Watkins, Citation2001) than fast-tracked students. Indeed, researchers have documented that this sort of “informal tracking” is pervasive in junior high schools across China (Dello-Iacovo, Citation2009; H. Liu & Wu, Citation2006; Yu & Suen, Citation2005; Yuen-Yee & Watkins, Citation1994).

Faced with this system, how do teachers decide which students deserve their time and effort? In other words, how do teachers decide student track placement in this informal tracking system? First, and most obviously, student track placement is determined by prior academic achievement (Betts & Shkolnik, Citation2000; Oakes, Citation1985; Slavin, Citation1993). In Chinese junior high schools, students are generally asked to take an exam (usually mathematics) at the beginning of junior high school to determine their prior academic ability for the purpose of tracking placement (Xinhua, Citation2010). Student motivation also matters: Students who are more motivated to go to high school are more likely to get placed in the fast track (H. Yi et al., Citation2015). Higher SES students are also more likely to be fast tracked, both due to the association between SES and academic achievement and due to the fact that social biases lead teachers and principals to expect students with wealthier and better educated parents to do better in the long run (Dang & Rogers, Citation2008; Tsang et al., Citation2010).

Due to this competitive environment, we believe that ability tracking produces variable levels of social trust among low-income students in different tracks in junior high schools in rural China. At the very age at which students begin to form their own beliefs (as separate from their parents) and start to understand society around them (Chen, Cen, Li, & He, Citation2005), fast-tracked education in China places students into two very different environments. Fast-tracked students are in an environment that is encouraging and that involves a great deal of positive interaction with authority figures; slow-tracked students are in an environment that may be characterized by verbal abuse, physical violence, apathy, and negative and contentious relationships between adults and children.

Research design

Sampling and data collection

We conducted our study in 132 rural, public junior high schools across 15 nationally designated low-income counties (71 in Shaanxi province and 61 Hebei province).Footnote2 Shaanxi is located in northwest China and has a gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of 27,133 yuan (4,000 USD), while Hebei is located in central China with a GDP per capita of 28,668 yuan (4,320 USD; China National Bureau of Statistics, Citation2011). These two provinces are different in location and socioeconomic status, and they are typical of counties in northern China, allowing us to generalize our findings to other similar counties in rural China.

The study was conducted in two rounds of surveys. In the first round, we surveyed all seventh-grade students, comprising a total of 473 classes across all 132 schools. After this baseline survey, we identified four students from the lowest income households within each class. These low-income students were to be the subjects of focus in our study. We conducted a follow-up survey 3 years later, in which we focused mainly on the subsample of the low-income students.

Baseline survey

In the baseline survey, we measured all students’ academic performance, and their individual and family characteristics. The first portion was a 30-min standardized math test containing items from the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS).Footnote3 The TIMSS test is a formal mathematics test metric, which covers six content areas, including fractions and number sense, measurement, proportionality, data representation, analysis, probability, geometry, and algebra (TIMSS 2007; Mullis et al., Citation2007). It has been used to measure trends in mathematics achievement at the fourth- and eighth-grade levels worldwide since 1995 (Beaton et al., Citation1996; Martin, Mullis, & Foy, Citation2009). There are more than 30 countries and regions that participated and were consulted in designing this standardized assessment system to ensure its broad applicability and reliability (Beaton et al., Citation1996; Martin & Preuschof, Citation2007). In our study, we selected 25 items from the eighth-grade TIMSS 2007. Before administering the mathematics test, we gathered a group of junior high school math teachers and verified that all of the questions we chose were relevant to their math curricula. The test was both strictly proctored (by our survey team) and timed.

The second portion of the baseline survey was a questionnaire measuring individual and family characteristics, including gender, age, parent education level, and migration status. These variables are often used to explain student-level educational outcomes (Behrman & Rosenzweig, Citation2002; Currie & Thomas, Citation2000; H. Yi et al., Citation2012) and social trust (Bowlby, Citation1988; Hall, Citation1999; Sampson & Laub, Citation1995). A description of all demographic variables used is provided in Appendix 1.

Third, we created our subsample of low-income studentsFootnote4 using the following protocol: (a) we asked students’ homeroom teachers from each class to fill out a questionnaire that specifically asked them to list the poorest five students within their class based on observation; (b) we had all seventh-grade students complete a survey at the beginning of the school year (in early October 2010), in which they were asked to fill out a checklist of major household durable assets; (c) we used principal component analysis (PCA), adjusting for the fact that all variables were dichotomous and not continuous, to calculate a single ranking of family assets from each student’s checklist (Kolenikov & Angeles, Citation2009). We matched the homeroom teachers’ list of lowest income students with our family assets rankings, to produce a subsample of the lowest income students in each class.

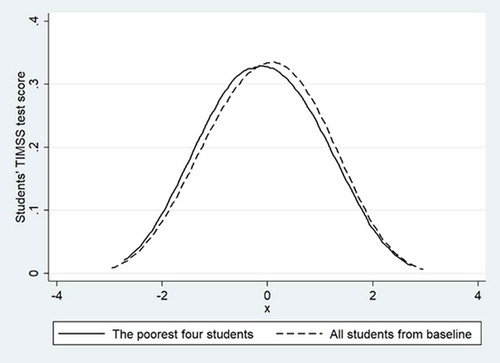

We repeated a process of randomly selecting low-income students from this pool, and comparing their TIMSS scores to that of the full sample, until we produced a sample of 1,892 low-income students from 473 classes in 132 schools, which was representative of the full sample in terms of academic achievement (TIMSS scores). shows that the low-income students performed at a lower level than the full sample of students. The distribution of low-income student scores is normal and is similar to that of the full sample of students.

Figure 1. Comparison of student TIMSS test score between poor sample students and full sample students.

Data source: authors’ survey.

Our sampling procedures first ensured that our subjects were all low-income students with no significant difference in SES; we thus removed the potential confounding effect of SES as an indicator for school tracking and an influence on student social trust from our study. Second, our subsample of students had a representative TIMSS scores distribution as the full sample. This distribution was also wide enough to ensure that we would see variability in students’ tracking status due purely to students’ ability.

Follow-up survey

The second-round survey, which was only administered to the subsample of low-income students, was conducted in October 2013, shortly after the students had graduated from junior high school and immediately after the students who went to high school had enrolled. This survey was conducted in two steps: first, we ascertained students’ current educational statuses. We coded whether students had: (a) enrolled into academic high school (henceforth high school), (b) left school before the end of junior high school, or (c) left the schooling system after graduating from junior high school.Footnote5 We visited all the students who had matriculated into high school in person to confirm their status and administered the social trust survey; we solicited the help of previous teachers and classmates to track down students who were no longer in school, and administered the social trust survey by either interviewing them over the phone or visiting them at their current place of work/residence. In the first wave of this follow-up survey, we made contact with 81% of the sample (1,528 students). Due to financial constraints, we were only able to conduct a second follow-up wave, which reached 25% of the remaining 19% of our subsample (62 sample students). We visited each of these 62 students in person to administer the social trust survey. Therefore, 9% of our sample (154 sample students) were lost to attrition and our sample for analysis comprised 1,436 students. We weighted our analysis to account for attrition.Footnote6

At the time of the second-round survey (3 years after the first-round survey), about 50% of the students (792) had enrolled in high school. Of the remaining students, 26% (401) never graduated from junior high school and about 24% of students (380) finished junior high but did not enroll in high school. In sum, half of the students (781) did not continue their studies.Footnote7

Measuring social trust

We focused on two narrowly defined attitudes that are important components of social trust: interpersonal trust and confidence in public institutions. We chose these two narrowly defined indicators because they are the core concepts used in past research on social trust (Glaeser, Laibson, Scheinkman, & Soutter, Citation2000), and surveys of these two indicators have been conducted in several dozen countries as part of the World Value Survey (WVS). Knack and Keefer (Citation1997) also provided empirical support for the validity of these indicators in an experiment conducted in various European countries and the United States.Footnote8 In our study, social trust indicators were based on questions taken directly from the World Value Survey.

We measured student social trust, using either face-to-face or phone interviews, so that each student could answer without the influence of other peers, teachers, or principal. To measure interpersonal trust, we asked the question: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you cannot be too careful in dealing with other people?” To measure confidence in public institutions, we asked: “I am going to name some institutions in this country. As far as the people running these institutions are concerned, would you say you have a great deal of confidence, only some confidence, or hardly any confidence at all in them?” The following institutions were listed: educational institutions, the media, banks and financial institutions, and the government. Detailed summaries of students’ responses to the social trust interview questions are presented in , and further details on the distributions of these results can be found in Appendix 1.

Table 1. Description of social trust variables.

Estimation strategy

Student track placement

As we explained above, although ability tracking is pervasive in China’s junior high schools, it is technically/legally prohibited. It is therefore impossible for researchers to directly collect explicit information about student tracking from students or teachers. The words “fast track” and “slow track” have never been used inside schools. As a consequence, school principals and teachers are often unwilling to respond to questions about it – in either formal interviews or in written surveys. They will almost all admit, confidentially, that there is still fast tracking inside classes in their school, but they will not do so “on the record”.

Therefore, to identify whether students were fast tracked or slow tracked during junior high school, we adopted an approach in which we sought to mimic the way teachers would identify students (early in their junior high careers) to either put them on the fast or slow track. As detailed above, international evidence (as well as studies in China) has shown that teachers in tracked schooling systems assign students to either the fast or slow track on the basis of pre-existing criteria including test scores, student motivation, and parents’ educational and occupational backgrounds.

In our analysis, we therefore used information from the baseline survey (administered when students were in Grade 7 in junior high school) to predict who ultimately (3 years later) would matriculate into high school. To do this, we first used a probit regression model to explain the observed relationship between baseline student characteristics and the later educational status of students (i.e., whether a student matriculated into high school):Footnote9

where Mij represents student i at school j’s educational status after the end of junior high school (at the time of our second-round survey). In our analysis, Mij is equal to one if a student matriculated into high school, and Mij is equal to zero if a student did not continue on to high school. In Equation (1), Sij, Pij, and Hij are vectors of baseline student, parent, and family background characteristics. The full list of demographic variables is presented in Appendix 1. represents school fixed effects, and εi is the regression error term.

Once we had estimated the relationship between students’ educational status and their observed background characteristics, we predicted whether students would be placed on the fast or slow track. Specifically, we used students’ observed background characteristics, along with the coefficients from Equation (1), (,

,

,

, and θj), to produce these predictions according to the following formula:

is an estimated probability that the student was assigned to the fast track. It is important to note that in this formulation,

ranges from zero to one.

This analysis produced reasonable predictions of ultimate educational statuses for each student. However, it produced a continuous variable. We therefore then used the method proposed in Wooldridge (Citation2010) to choose a cutoff point (ρ) that allowed us to divide the students into two categories: those who were most likely to continue on to high school (fast track) and those who were least likely to continue on to high school (slow track). Conceptually, this method enabled us to maximize the percent of students who were correctly predicted. Specifically, using this approach, if was larger than a set probability threshold at which the maximum percent was correctly predicted, the student was assigned to the fast track (Ti = 1). If

was lower, the student was assigned to the slow track (Ti = 0).

We then counted the false predictions, that is, cases in which a student was assigned to the fast (or slow) track but did not (or did) matriculate into high school. Then we calculated the false-prediction rate (number of incorrectly predicted students divided by all students) over each probability threshold and plotted a decision curve. We then chose the probability threshold cutoff (ρ) that gave us the lowest false-prediction rate (or the maximum percent correctly predicted).

We present the probit regression results in . In running this regression, we found that the probability value ρ = 0.55 gave us the lowest false-prediction rate (21%, ). This means that our model correctly predicted a student’s high school matriculation from their baseline characteristics 79% of the time. We determined that 788 students in our sample were fast tracked (, row 1, column 3) and 648 students were slow tracked (, row 2, column 3).

Table 2. The determinants of student track placement, probit regression.

Table 3. Predicted student track placement.

We found that of the 788 students predicted to be fast tracked, 173 ultimately did not matriculate into high school. Henceforth, we call these students underachievers: They were fast tracked during junior high school but failed to live up to their potential, by not gaining admission to high school. Of the 648 slow-tracked students, 137 did end up matriculating into high school in spite of their less impressive baseline characteristics. Hereafter, we call these students overachievers: They exceeded their baseline potential by gaining admission to high school, against the odds. In the final section of the paper, as a robustness check of our analysis, we looked in particular at the under- and overachievers to see whether their defiance of original expectations was related to different levels of social trust as compared to the students who performed as predicted by their backgrounds.

Tracking and student social trust

Once we assigned each student to be fast or slow tracked, we analyzed how student tracking was related to student social trust at the end of junior high school. To do so, we conducted ordinary least square (OLS) regression analyses using the following model:

In Equation (3), Yij is the outcome variable that we are interested in. Tij is the dummy treatment variable, which has a value of 1 if students were predicted to be fast tracked (≥ 0.55), or 0 if they were predicted to be slow tracked (

˂ 0.55).

is the same vector of student, parent, and family characteristics from Equation (1). We also controlled for school fixed effects (

) and clustered standard errors at the school level.

Results

Social trust among rural young adults in China

Overall, we found a significant lack of interpersonal trust among the rural low-income junior high school students in China. About half of the sample students reported that most people cannot be trusted (49%, , row 1, column 1). With regard to students’ confidence in public institutions, the results were even worse. Over two thirds of students distrust public institutions (, rows 2 to 5, column 1). Specifically, only 36% of students reported that they are confident in educational institutions. More than 60% of our sample students distrust schools. Only 19% of students reported that they trust the media (, row 3, column 1). The confidence of students in banks and financial institutions and in the government is, unsurprisingly, similarly low, 40% and 38%, respectively, for this sample of rural low-income students (, rows 4 to 5, column 1).

Table 4. Differences in social trust between fast-tracked and slow-tracked students.

Tracking and social trust

Descriptive analysis

We found that ability tracking is highly correlated with social trust. Specifically, fast-tracked students had significantly higher levels of interpersonal trust than their slow-tracked peers. For example, the interpersonal trust of fast-tracked students was 17 percentage points higher than that of their slow-tracked peers (, row 1, column 4). About 59% of fast-tracked students believed that “most people can be trusted”, while only 42% of slow-tracked students believed the same (, row 1, columns 2 and 3). The gap in confidence in public institutions was even wider. We found that only 20% of slow-tracked students trust educational institutions (, row 2, column 3). Fast-tracked students had almost three times (30 percentage points) higher probability than slow-tracked students of feeling confident in educational institutions (, row 2, column 4).

Similar results could also be found for student confidence in other public institutions. For example, descriptive analyses showed that fast-tracked students were 11 percentage points higher than slow-tracked students in their confidence in the media (, row 3, column 4), 17 percentage points higher than slow-tracked students in their confidence in banks and financial institutions (, row 4, column 4), and 22 percentage points higher in their confidence in the government (, row 5, column 4).

Multivariate analysis

After controlling for individual, parent, and family characteristics, as well as school fixed effects, we found that fast-tracked students were still, on average, 15 percentage points higher than slow-tracked students in their interpersonal trust (, row 1, column 1). This result provides evidence that ability tracking is positively associated with student social trust.

Table 5. The correlation between student track and social trust, OLS results.

The OLS regression results for student confidence in public institutions were consistent with those for interpersonal trust, and robust. As shown in , fast-tracked students were 15 percentage points higher in confidence in the schooling system (row 1, column 2); 7 percentage points higher in confidence in the media (row 1, column 3); 13 percentage points higher in confidence in banks and financial institutions (row 1, column 4); and 16 percentage points higher in confidence in the government (row 1, column 5) than slow-tracked students. All of these results were significant at the α = 0.1 level or higher.

Disappointment, overachievement, and social trust

In the preceding section, we examined the relationship between ability tracking (a decision that we are assuming is typically made early on in junior high school) and student social trust (which is measured after matriculation into high school). However, there might be an additional effect to consider. In a competitive education system where schooling outcomes are primarily determined by a single high-stakes test, the impact of tracking may be tempered by unexpected results on that test. If a fast-tracked student fails to realize his or her goal of matriculating into high school, their social trust might be negatively impacted.Footnote10 Conversely, a slow-tracked student who unexpectedly makes it into high school by doing well on the exam may experience positive impacts on their social trust. To yield some insights about these potential disappointment and overachievement effects on student social trust, in the following section we have performed two robustness checks.

Robustness analysis

In this subsection, we examined the robustness of our results in two ways. First, instead of examining social trust by ability tracking, we simply divided the observations into those students that went to high school and those that did not. We did this because it is possible that social trust may be affected by the mere fact of being able to matriculate into high school or not. In addition, matriculation into high school was much more observable than participation in the fast or slow track. Second, we examined the impact of ability tracking on social trust, but we recognized that the expectations of being on a track (which we assume has a positive effect on social trust) may not always be realized. Specifically, we examined what happens to social trust when a fast-tracked student does not get into high school, conversely, what happens to social trust when a slow-tracked student makes it into high school.

Going to high school or not

When we split the sample into those who went to high school and those who did not, the results were similar to those obtained in the ability tracking analysis (see Appendix 2). For example, we found that students who matriculated into high schools were 22 percentage points higher than students who did not matriculate into high schools in interpersonal trust (Appendix 2, row 1, column 1). We found the same pattern of results for student confidence in public institutions. Students who matriculated into high school had 34 percentage points higher confidence in educational institutions relative to their peers who did not matriculate into high school (Appendix 2, row 1, column 2). These students’ confidence in the media was 13 percentage points higher, confidence in banks and financial institutions was 21 percentage points higher, and confidence in the government was 24 percentage points higher (Appendix 2, rows 3 to 5, column 3) than those who did not matriculate into high school. These results held after we controlled for student individual, parents, and family characteristics and school fixed effects using OLS regression (Appendix 2, rows 1 to 5, column 4).

Unrealized expectations

An issue that has received attention in other countries that have ability tracking systems and high-stakes exams is the effect of realized or unrealized student expectations (Clarke, Haney, & Madaus, Citation2000; H. Liu & Wu, Citation2006; Yu & Suen, Citation2005). If student tracking creates a certain amount of positive (or negative) social trust for high-performing (or low-performing) students, what happens to that level of trust when a fast-tracked student fails to pass the high-stakes exam at the end of the program? Conversely, what happens to low levels of trust when a slow-tracked student somehow manages to pass the high-stakes exam against the odds? Is the trust (or lack of trust) that is fostered during a student’s experience in the tracked school system reversed or maintained under such circumstances?

To investigate this possibility, we examined and compared the levels of social trust of underachievers (fast-tracked students who did not get into high school) and overachievers (slow-tracked students who got into high school against the odds). We found a significant positive relationship between social trust and overachievement. That is, slow-tracked students who managed to get into high school had 21 percentage points higher interpersonal trust than slow-tracked students who did not get into high school (, row 1, column 3). The same relationship held for confidence in public institutions. Overachieving slow-tracked students had 27 percentage points higher confidence in educational institutions relative to their other slow-tracked peers (, row 2, column 3). Their confidence in the media was 9 percentage points higher, their confidence in banks and financial institutions was 24 percentage points higher, and their confidence in the government was 28 percentage points higher (, rows 3 to 5, column 3) than that of their non-overachieving slow-tracked peers. In fact, we found that the “overachievement” effect on social trust was actually larger than the “tracking” effect on social trust for some outcomes (, column 4 vs. , column 3), such as interpersonal trust (21 – 17 = 4 percentage points), confidence in banks and financial institutions (24 – 17 = 7 percentage points), and confidence in the government (28 – 22 = 6 percentage points).

Table 6. Overachievers and underachievers: comparison of social trust.

Underachieving appeared to have a negative effect on social trust. Fast-tracked students who failed to matriculate into high school showed significantly lower levels of interpersonal trust relative to their fast-tracked peers who did get into high school (20 percentage points, , row 1, column 6). This negative relationship held for confidence in public institutions. Underachievers showed significantly lower levels of confidence in educational institutions (37 percentage points, , row 2, column 6), lower confidence in the media (13 percentage points, , row 3, column 6), lower confidence in banks and financial institutions (27 percentage points, , row 4, column 6), and lower confidence in the government (21 percentage points, , row 5, column 6). The magnitude of these negative effects was even higher than the positive effects observed for overachieving slow-tracked students.

We present the multivariate analysis in Appendix 3. The adjusted model (with controls for individual, parents, and family characteristics, as well as school fixed effects) produced results of similar magnitudes that were statistically significant. All observed negative impacts for the underachievers were significant at the α = 0.01 level.

Conclusion and implications

Drawing on data from 1,436 low-income students in rural China, our study investigated social trust among this demographic and examined the relationship between ability tracking of students and their social trust. In general, we find a significant lack of interpersonal trust among rural low-income young adults. Their confidence in public institutions is even lower. We also find that there is a strong relationship between their ability tracking during junior high school and their social trust. Students who are fast tracked while in school have significantly higher interpersonal trust and confidence in public institutions relative to students who are slow tracked, even when controlling for student, parent, and family characteristics. Furthermore, we find that student expectations matter. Students whose baseline characteristics make them more likely to gain admission to high school, such as by having more motivation to enroll, or better academic performance, experience a significant reduction in social trust when they are unsuccessful in that effort. Students whose baseline characteristics make them less likely to gain admission to high school experience a rather positive gain in social trust when they are unexpectedly able to get into high school.

Implications of findings

Why is there such a low rate of social trust among rural low-income students? And what is the mechanism behind ability tracking’s relationship to student social trust? While the results admittedly only suggest correlation and not a causal relationship, we believe it might be the case that in China’s rural secondary schools, ability tracking substantially decreases student social trust. In fact, the international literature would support such a conjecture.

First, recent studies conducted on the German secondary education system show significant advantages for academic track students in terms of teacher qualification (Klusmann et al., Citation2008) and cognitively demanding instruction (Retelsdorf, Butler, Streblow, & Schiefele, Citation2010). That is, slow-tracked students are often assigned to teachers who are impatient, less engaged with their work, and even depressed under certain circumstances (Klusmann et al., Citation2008). In contrast, fast-tracked students are often equipped with more effective teachers in the sense that these teachers have higher levels of work engagement and resilience to stress (Hallberg & Schaufeli, Citation2006; Shuell, Citation1996). The same disparities between fast-tracked and slow-tracked students might also exist in China’s rural secondary schools.

Second, research has shown that there exist strong composition effects, or peer effects, in ability tracking when high-achieving students are grouped together (Trautwein et al., Citation2006). For example, grouping together high-achieving students who enjoy a more favorable social background creates more positive interactions among these students (Maaz, Trautwein, Lüdtke, & Baumert, Citation2008; Trautwein et al., Citation2006). However, slow-tracked students might be isolated from high-achieving peers, and such negative school environments around slow-tracked students might create further antisocial behaviors (Shi et al., Citation2015). Although we did not directly observe compositional effects of ability tracking in our study, other studies on China’s rural secondary education system have documented this phenomenon (Ding & Lehrer, Citation2007). Ability tracking might further widen the gap between relatively privileged students who are staying in school and the less privileged students who are dropping out.

Third, we find that student expectations matter. In a competitive education system, such as China’s, academic success is perceived as the only channel by which rural students may pursue a more successful career path in the future. Unexpected failure might destroy these students’ self-confidence and self-esteem (Mueller & Dweck, Citation1998). For example, Lam, Yim, Law, and Cheung (Citation2004) found that students in China’s secondary education system and above experience more dramatic decreases in their self-confidence and self-esteem when they fail to meet their expected goals (achieving higher grades). This finding further aligns with our findings that fast-tracked students who fail to matriculate into high school might show even lower social trust. On the other hand, we observe that slow-tracked students who unexpectedly matriculate into high school have higher levels of social trust than their slow-tracked peers who do not get into high school. This may suggest that making high school accessible to more students would have a positive impact on improving social trust among the rural low-income young population.

Limitations for future researches

Although we examined the relationship between ability tracking and student social trust from various perspectives, our study is not without limitations. First, due to the fact that it is impossible for researchers to quantitatively capture the exact placement of students in their ability tracks, in our study we mimic the way teachers and school principals would identify students and place them in different tracks. We believe that the predictions in our study are rather convincing as our model produces a rather low false prediction rate. However, if and when more objective measures of student ability tracking are available, we would recommend using these more objective measures to assess the relationship between ability tracking and social trust.

Second, focusing on the low-income students in these two provinces enables us to reduce or minimize the potential correlation between family SES and student social trust. However, this also limits our sample’s generalizability to the population of rural young adults in China. We must therefore be cautious when interpreting these results in the context of broader populations. However, since this is the first study to examine social trust among rural young adults in China, we believe that it should still be of interest to the field.

Third, in our study we focused on student social trust. However, there are many other sociopsychological outcomes (e.g., student self-efficacy, grit, self-confidence, etc.) that are equally important for understanding ability tracking and its consequence on student outcomes in a developing country context. On the other hand, ability tracking is an important general school practice, along with teacher behavior, school institutional arrangements, parents’ nurturing behaviors, peer effects, and so on. All of these practices are strongly interrelated with ability tracking, and significantly affect student performance. Therefore, we believe a more structured and theory-based research framework should be established and applied in guiding future empirical research on ability tracking and student outcomes. More empirical research is also needed in the developing country context to yield a more comprehensive understanding about ability tracking and its associated impacts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fan Li

Fan Li is currently a post-doctoral research fellow at Development Economics Group, Wageningen University and Research. Fan Li received his PhD from LICOS-Centre for Institutions and Economic Performance, KU Leuven, Belgium. His research interests are mainly focusing on rural development and higher education financing in China.

Prashant Loyalka

Prashant Loyalka is a faculty member of the Rural Education Action Program, a Centre Research Fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, and assistant Professor (Research) at the Graduate School of Education, Stanford University. His research focuses on examining and addressing inequalities in the education of youth and on understanding and improving the quality of education received by youth in a range of countries including China, Russia, and India. Among his various projects, he is currently leading a large-scale international, comparative study to assess and improve student learning in higher education. He also frequently conducts large-scale evaluations of educational programs and policies.

Hongmei Yi

Hongmei Yi is Associate Professor at the China Centre for Agricultural Policy, School of Advanced Agricultural Sciences, Peking University. Her research agenda addresses questions on the building of human capital (education and health) in rural China through rigorous impact evaluation.

Yaojiang Shi

Yaojiang Shi is Professor of Economics at Shaanxi Normal University, China. He is the Director of the Centre for Experimental Economics in Education (CEEE). His work is focused on China’s education reforms and using empirical research to identify important leverage points for education policy that address the needs of the rural poor.

Natalie Johnson

Natalie Johnson is project manager at Rural Education Action Project (REAP) at Stanford University. She has extensive experience managing development projects in rural China, and her research interests are mainly focusing on preventing dropout and improving education quality in rural China.

Scott Rozelle

Scott Rozelle holds the Helen Farnsworth Endowed Professorship at Stanford University and is Senior Fellow in the Food Security and Environment Program and the Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center, Freeman Spogli Institute (FSI) for International Studies. Rozelle spends most of his time co-directing the Rural Education Action Project (REAP). Currently, his work on poverty has its full focus on human capital, including issues of rural health, nutrition, and education.

Notes

1. Ability tracking can happen in various forms. For example, students may be sorted on socioeconomic class, prior academic performance, other personal characteristics, or a combination of any of these. In our study, we specifically focus on ability tracking in China’s secondary education system, which is based on academic performance.

2. There were 18 schools in Hebei that were excluded due to the fact that the number of seventh-grade students was less than 50, and schools might be merged with some other schools in the near future.

3. We chose math test scores because they are one of the most common outcome variables used to proxy educational performance in the literature (Glewwe & Kremer, Citation2006; Rivkin, Hanushek, & Kain, Citation2005; Schultz, Citation2004).

4. Although we were concerned about the effect that restricting our sample to low-income students would have on the external validity of our study, we did this in order to avoid the bias of socioeconomic status (Betts & Shkolnik, Citation2000; Sirin, Citation2005), and disentangle the relationships between ability tracking and social trust and family SES and social trust.

5. We focus on academic high schools (rather than vocational high schools) because they are ascribed higher social value in Chinese society.

6. In our analysis, students were weighted using the analytical weights calculated in Stata 13.1 MP. We also used multiple imputations to deal with missing data. Specifically, we used the mean, median, and regression predictions to impute missing values. Regression results with imputed data were consistent with those produced without imputation.

7. Re-entering the schooling system after dropping out is possible in China, but very uncommon.

8. Knack and Keefer (Citation1997) found that, across countries and regions, trust is strikingly correlated with the number of wallets that were “lost” and subsequently returned with their contents intact.

9. All statistical analysis (e.g., regression analysis, probit analysis, and probit prediction) was conducted with Stata 13.1 MP, and basic figures were generated using Excel.

10. Fast-tracked students may fail to achieve their goal of matriculating into high school for various reasons. For example, students might not be able to pass high-stakes exams, as we have argued that this competitive exam system often frustrates students (F. Li et al., Citation2017; Mo et al., Citation2013). Students may not matriculate into high school simply because the cost of high schools is beyond their family’s capability (C. Liu et al., Citation2009), and indeed opportunity costs are increasing quickly in China (H. Yi et al., Citation2012).

References

- Alesina, A., & La Ferrara, E. (2000). The determinants of trust (Working Paper No. 7621). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w7621. Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w7621

- Arteaga, I., & Glewwe, P. (2014). Achievement gap between indigenous and non-indigenous children in Peru: An analysis of young lives survey data (Working Paper No. 130). Oxford, UK: Young Lives. Retrieved from http://repositorio.minedu.gob.pe/handle/123456789/4493

- Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2011). Why aren’t children learning. Development Outreach, 13(1), 36–44. doi:10.1596/1020-797X_13_1_36

- Baum, F., Parker, C., Modra, C., Murray, C., & Bush, R. (2000). Families, social capital and health. In I. Winter (Ed.), Social capital and public policy in Australia (pp. 250–275). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Beaton, A. E., Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Gonzalez, E. J., Kelly, D. L., & Smith, T. A. (1996). Mathematics achievement in the middle school years: IEA’s Third International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS). Chestnut Hill, MA: Center for the Study of Testing, Evaluation, and Educational Policy, Boston College.

- Behrman J. R., & Rosenzweig, M. R. (2002). Does increasing women’s schooling raise the schooling of the next generation? American Economic Review, 92(1), 323–334. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3083336

- Bernstein, B. (1975). Class, codes and control: Towards a theory of educational transmission (Vol. 3). London, UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Retrieved from https://epdf.tips/towards-a-theory-of-educational-transmissions-class-codes-and-control.html

- Betts, J. R., & Shkolnik, J. L. (2000). The effects of ability grouping on student achievement and resource allocation in secondary schools. Economics of Education Review, 19(1), 1–15. doi:10.1016/S0272-7757(98)00044-2

- Booij, A. S., Leuven, E., & Oosterbeek, H. (2017). Ability peer effects in university: Evidence from a randomized experiment. The Review of Economic Studies, 84(2), 547–578. doi:10.1093/restud/rdw045

- Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. J. D. (1992). An invitation to reflexive sociology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Bowditch, C. (1993). Getting rid of troublemakers: High school disciplinary procedures and the production of dropouts. Social Problems, 40(4), 493–509. doi:10.2307/3096864

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. London, UK: Routledge.

- Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (1976). Schooling in capitalist America: Educational reform and the contradiction of economic life. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Brehm, J., & Rahn, W. (1997). Individual-level evidence for the causes and consequences of social capital. American Journal of Political Science, 41(3), 999–1023. doi:10.2307/2111684

- Brown, P. H., & Park, A. (2002). Education and poverty in rural China. Economics of Education Review, 21(6), 523–541. doi:10.1016/S0272-7757(01)00040-1

- Burns, N., Kinder, D., & Rahn, W. (2003, April). Social trust and democratic politics. Paper prepared for the Annual Meeting of the Mid-West Political Science Association, Chicago, IL. Retrieved from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.203.4681&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Cantoni, D., & Yuchtman, N. (2013). The political economy of educational content and development: Lessons from history. Journal of Development Economics, 104, 233–244. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2013.04.004

- Chen, X., Cen, G., Li, D., & He, Y. (2005). Social functioning and adjustment in Chinese children: The imprint of historical time. Child Development, 76(1), 182–195. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00838.x

- Cheng, L. (1997). How does washback influence teaching? Implications for Hong Kong. Language and Education, 11(1), 38–54. doi:10.1080/09500789708666717

- Cheung, C.-K., & Rudowicz, E. (2003). Academic outcomes of ability grouping among junior high school students in Hong Kong. The Journal of Educational Research, 96(4), 241–254. doi:10.1080/00220670309598813

- China National Bureau of Statistics. (2011). China statistical yearbook – 2011. Retrieved from http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2011/indexch.htm

- Clarke, M., Haney, W., & Madaus, G. (2000). High stakes testing and high school completion. National Board on Educational Testing and Public Policy: Statements, 1(3), 1–12. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED456139

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology), 94(1), S95–S120. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2780243

- Currie, J., & Thomas, D. (2000). School quality and the longer-term effects of head start. Journal of Human Resources, 35(4), 755–774. doi:10.2307/146372

- Dang, H.-A., & Rogers, F. H. (2008). The growing phenomenon of private tutoring: Does it deepen human capital, widen inequalities, or waste resources? The World Bank Research Observer, 23(2), 161–200. doi:10.1093/wbro/lkn004

- Dello-Iacovo, B. (2009). Curriculum reform and “quality education” in China: An overview. International Journal of Educational Development, 29(3), 241–249. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2008.02.008

- Ding, W., & Lehrer, S. F. (2007). Do peers affect student achievement in China’s secondary schools? The Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(2), 300–312. doi:10.1162/rest.89.2.300

- Duflo, E., Dupas, P., & Kremer, M. (2011). Peer effects, teacher incentives, and the impact of tracking: Evidence from a randomized evaluation in Kenya. The American Economic Review, 101(5), 1739–1774. doi:10.1257/aer.101.5.1739

- Epple, D., Newlon, E., & Romano, R. (2002). Ability tracking, school competition, and the distribution of educational benefits. Journal of Public Economics, 83(1), 1–48. doi:10.1016/S0047-2727(00)00175-4

- Fiedler, E. D., Lange, R. E., & Winebrenner, S. (2002). In search of reality: Unraveling the myths about tracking, ability grouping, and the gifted. Roeper Review, 24(3), 108–111. doi:10.1080/02783190209554142

- Figlio, D. N., & Page, M. E. (2002). School choice and the distributional effects of ability tracking: Does separation increase inequality? Journal of Urban Economics, 51(3), 497–514. doi:10.1006/juec.2001.2255

- Filmer, D. (2000). The structure of social disparities in education: Gender and wealth (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2268). Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=629118

- Fortin, L., Marcotte, D., Potvin, P., Royer, E., & Joly J. (2006). Typology of students at risk of dropping out of school: Description by personal, family and school factors. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 21(4), 363–383. doi:10.1007/BF03173508

- Glaeser, E. L., Laibson, D. I., Scheinkman, J. A., & Soutter, C. L. (2000). Measuring trust. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 811–846. doi:10.1162/003355300554926

- Glewwe, P., Hanushek, E. A., Humpage, S., & Ravina, R. (2013). School resources and educational outcomes in developing countries: A review of the literature from 1990 to 2010. In P. Glewwe (Ed.), Education policy in developing countries (pp. 13–64). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Glewwe, P., & Kremer, M. (2006). Schools, teachers, and education outcomes in developing countries. In E. A. Hanushek & F. Welch (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of education (Vol. 2, pp. 945–1017). Amsterdam: North-Holland. doi:10.1016/S1574-0692(06)02016-2

- Grootaert, C. (2001). Social capital: The missing link. In P. Dekker & E. M. Uslaner (Eds.), Social capital and participation in everyday life (pp. 9–29). London: Routledge.

- Hall, P. A. (1999). Social capital in Britain. British Journal of Political Science, 29(3), 417–461. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/194145

- Hallberg, U. E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2006). “Same same” but different? Can work engagement be discriminated from job involvement and organizational commitment? European Psychologist, 11(2), 119–127. doi:10.1027/1016-9040.11.2.119

- Hallinan, M. T. (1996). Track mobility in secondary school. Social Forces, 74(3), 983–1002. doi:10.1093/sf/74.3.983

- Halpern, D. (2005). Social capital. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Hanushek, E. A., & Wößmann, L. (2006). Does educational tracking affect performance and inequality? Differences-in-differences evidence across countries. The Economic Journal, 116(510), C63–C76. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2006.01076.x

- Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (2007). Education and social capital. Eastern Economic Journal, 33(1), 1–19. doi:10.1057/eej.2007.1

- Hoffer, T. B. (1992). Middle school ability grouping and student achievement in science and mathematics. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 14(3), 205–227. doi:10.3102/01623737014003205

- Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., & Sandler, H. M. (1997). Why do parents become involved in their children’s education? Review of Educational Research, 67(1), 3–42. doi:10.3102/00346543067001003

- Inglehart, R. (1999). Trust, well-being and democracy. In M. E. Warren (Ed.), Democracy and trust (pp. 88–120). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Kerckhoff, A. C., & Glennie, E. (1999). The Matthew effect in American education. Research in Sociology of Education and Socialization, 12, 35–66.

- Khor, N., Pang, L., Liu, C., Chang, F., Mo, D., Loyalka, P., & Rozelle, S. (2016). China’s looming human capital crisis: Upper secondary educational attainment rates and the middle-income trap. The China Quarterly, 228, 905–926. doi:10.1017/S0305741016001119

- Klusmann, U., Kunter, M., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., & Baumert, J. (2008). Teachers’ occupational well-being and quality of instruction: The important role of self-regulatory patterns. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(3), 702–715. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.100.3.702

- Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1995). Institutions and economic performance: Cross-country tests using alternative institutional measures. Economics & Politics, 7(3), 207–227. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0343.1995.tb00111.x

- Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1251–1288. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2951271

- Kokko, K., & Pulkkinen, L. (2000). Aggression in childhood and long-term unemployment in adulthood: A cycle of maladaptation and some protective factors. Developmental Psychology, 36(4), 463–472. doi:10.1037//0012-1649.36.4.463

- Kokko, K., Tremblay, R. E., Lacourse, E., Nagin, D. S., & Vitaro, F. (2006). Trajectories of prosocial behavior and physical aggression in middle childhood: Links to adolescent school dropout and physical violence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16(3), 403–428. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00500.x

- Kolenikov, S., & Angeles, G. (2009). Socioeconomic status measurement with discrete proxy variables: Is principal component analysis a reliable answer? Review of Income and Wealth, 55(1), 128–165. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4991.2008.00309.x

- Kraft, M. A., & Rogers, T. (2015). The underutilized potential of teacher-to-parent communication: Evidence from a field experiment. Economics of Education Review, 47, 49–63. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2015.04.001

- Kulik, C.-L. C., & Kulik, J. (1982). Effects of ability grouping on secondary school students: A meta-analysis of evaluation findings. American Educational Research Journal, 19(3), 415–428. doi:10.3102/00028312019003415

- Lai, F. (2007). How do classroom peers affect student outcomes? Evidence from a natural experiment in Beijing’s middle schools. Retrieved from https://www.aeaweb.org/annual_mtg_papers/2008/2008_447.pdf

- Lam, S.-F., Yim, P.-S., Law, J. S. F., & Cheung, R. W. Y. (2004). The effects of competition on achievement motivation in Chinese classroom. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74(2), 281–296. doi:10.1348/000709904773839888

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). Trust in large organizations. The American Economic Review, 87(2), 333–338. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2950941

- Lee, J. C.-K., Yin, H., & Zhang, Z. (2009). Exploring the influence of the classroom environment on students’ motivation and self-regulated learning in Hong Kong. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 18(2), 219–232. doi:10.3860/taper.v18i2.1324

- Lei, W. (2005). Expenditure on private tutoring for senior secondary students: Determinants and policy implications. Education and Economy, 2005(1), 39–42. [in Chinese]. Retrieved from http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTotal-JYJI200501009.htm

- Leigh, A. (2006). Trust, inequality and ethnic heterogeneity. Economic Record, 82(258), 268–280. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4932.2006.00339.x

- Li, F., Song, Y., Yi, H., Wei, J., Zhang, L., Shi, Y., … Rozelle, S. (2017). The impact of conditional cash transfers on the matriculation of junior high school students into rural China’s high schools. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 9(1), 41–60. doi:10.1080/19439342.2016.1231701

- Li, Y., Pickels, A., & Savage, M. (2005). Social capital and social trust in Britain. European Sociological Review, 21(2), 109–123. doi:10.1093/esr/jci007

- Liu, C., Zhang, L., Luo, R., Rozelle, S., Sharbono, B., & Shi, Y. (2009). Development challenges, tuition barriers, and high school education in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 29(4), 503–520. doi:10.1080/02188790903312698

- Liu, D. (2014). Secrets behind slow-tracked students matriculated into vocational high school [in Chinese]. Retrieved from http://www.jyb.cn/zyjy/zjsd/201407/t20140710_589800.html

- Liu, H., & Wu, Q. (2006). Consequences of college entrance exams in China and the reform challenges. KEDI Journal of Educational Policy, 3(1), 7–21.

- Loyalka, P., Shi, Z., Chu, J., Johnson, N., Wei, J., & Rozelle, S. (2014). Is the high school admissions process fair? Explaining inequalities in elite high school enrollments in developing countries (Working Paper No. 276). Stanford, CA: Rural Education Action Program (REAP), Stanford University. Retrieved from https://reap.fsi.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/276-is_the_high_school_admissions_process_fair.pdf

- Maaz, K., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., & Baumert, J. (2008). Educational transitions and differential environments: How explicit between-school tracking contributes to social inequality in educational outcomes. Child Development Perspectives, 2(2), 99–106. doi:10.1111/j.1750-8606.2008.00048.x

- Martin, M. O., Mullis, I. V. S., & Foy, P. (with Olson, J. F., Preuschoff, C., Erberber, E., Arora, A., & Galia, J.). (2009). TIMSS 2007 international mathematics report: Findings from IEA’s Trends in International Mathematics And Science Study at the fourth and eighth grades. Chestnut Hill, MA: TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College.

- Martin, M. O., & Preuschoff, C. (2007). Creating the TIMSS 2007 background indices. In J. F. Olson, M. O. Martin, & I. V. S. Mullis (Eds.), TIMSS 2007 technical report (pp. 281–338). Chestnut Hill, MA: TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College.

- McPartland, J. (1993). Dropout prevention in theory and practice. Baltimore, MD: Center for Research on Effective Schooling for Disadvantage Students.

- Ministry of Education. (2006). Compulsory education law of the People’s Republic of China. Beijing, China: Author. Retrieved from http://old.moe.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/moe_2803/200907/49979.html

- Mo, D., Zhang, L., Yi, H., Luo, R., Rozelle, S., & Brinton C. (2013). School dropouts and conditional cash transfers: Evidence from a randomised controlled trial in rural China’s junior high schools. The Journal of Development Studies, 49(2), 190–207. doi:10.1080/00220388.2012.724166

- Mueller, C. M., & Dweck, C. S. (1998). Praise for intelligence can undermine children’s motivation and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 33–52. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.33

- Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Ruddock, G. J., O’Sullivan, C. Y., Arora, A., & Erberber, E. (2007). TIMSS 2007 assessment frameworks. Chestnut Hill, MA: TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College. Retrieved from https://timssandpirls.bc.edu/TIMSS2007/frameworks.html

- Narayan, D. (1997). Voices of the poor: Poverty and social capital in Tanzania. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Oakes, J. (1982). The reproduction of inequity: The content of secondary school tracking. The Urban Review, 14(2), 107–120. doi:10.1007/BF02174647

- Oakes, J. (1985). Keeping track: How schools structure inequality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Organisation for Economic and Co-operation Development. (2012). Education at a glance 2012: OECD indicators. Paris, France: Author. doi:10.1787/eag-2012-en

- Putnam, R. (1993). The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. The American Prospect, 4(13), 35–42. Retrieved from http://staskulesh.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/prosperouscommunity.pdf

- Retelsdorf, J., Butler, R., Streblow, L., & Schiefele, U. (2010). Teachers’ goal orientations for teaching: Associations with instructional practices, interest in teaching, and burnout. Learning and Instruction, 20(1), 30–46. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2009.01.001

- Rivkin, S. G., Hanushek, E. A., & Kain, J. F. (2005). Teachers, schools, and academic achievement. Econometrica, 73(2), 417–458. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0262.2005.00584.x

- Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1995). Crime in the making: Pathways and turning points through life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Schultz, T. (2004). School subsidies for the poor: Evaluating the Mexican Progresa poverty program. Journal of Development Economics, 74(1), 199–250. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2003.12.009

- Shi, Y., Zhang, L., Ma, Y., Yi, H., Liu, C., Johnson, N., … Rozelle, S. (2015). Dropping out of rural China’s secondary schools: A mixed-methods analysis. The China Quarterly, 224, 1048–1069. doi:10.1017/S0305741015001277

- Shuell, T. J. (1996). Teaching and learning in a classroom context. In D. C. Berliner & R. C. Calfee (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 726–764). New York, NY: Macmillan. doi:10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/02449-9

- Sirin, S. R. (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 417–453. doi:10.3102/00346543075003417

- Slavin, R. E. (1990). Achievement effects of ability grouping in secondary schools: A best-evidence synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 60(3), 471–499. doi:10.3102/00346543060003471

- Slavin, R. E. (1993). Ability grouping in the middle grades: Achievement effects and alternatives. The Elementary School Journal, 93(5), 535–552. doi:10.1086/461739

- Stevenson, H. W., Lee, S.-Y., & Chen, C. (1994). Education of gifted and talented students in mainland China, Taiwan, and Japan. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 17(2), 104–130. doi:10.1177/016235329401700203

- Talbert, J. E., & Ennis, M. (1990, April). Teacher tracking: Exacerbating inequalities in the high school. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Boston, MA.

- Tang, T. (1991). Students’ perceptions of the learning context and their effects on approaches to learning: A phenomenographic study ( Unpublished doctoral dissertation). The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

- Tarabini, A. (2010). Education and poverty in the global development agenda: Emergence, evolution and consolidation. International Journal of Educational Development, 30(2), 204–212. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.04.009

- Tilak, J. B. G. (2001). Education and development: Lessons from Asian experience. Indian Social Science Review, 3(2), 219–266.

- Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Marsh, H. W., Köller, O., & Baumert, J. (2006). Tracking, grading, and student motivation: Using group composition and status to predict self-concept and interest in ninth-grade mathematics. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(4), 788–806. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.98.4.788

- Tsang, M. C. (2000). Education and national development in China since 1949: Oscillating policies and enduring dilemmas. China Review, 579–618. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23453384

- Tsang, M. C., Ding, X., & Shen, H. (2010). Urban-rural disparities in private tutoring of lower-secondary students. Education and Economics, 2010(2), 7–11. [in Chinese]. Retrieved from http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-JYJI201002002.htm

- Van Houtte, M., Demanet, J., & Stevens, P. A. J. (2012). Self-esteem of academic and vocational students: Does within-school tracking sharpen the difference? Acta Sociologica, 55(1), 73–89. doi:10.1177/0001699311431595

- Vickers, H. S. (1994). Young children at risk: Differences in family functioning. The Journal of Educational Research, 87(5), 262–270. doi:10.1080/00220671.1994.9941253

- Wang, H., Yang, C., He, F., Shi, Y., Qu, Q., Rozelle, S., & Chu, J. (2015). Mental health and dropout behavior: A cross-sectional study of junior high students in northwest rural China. International Journal of Educational Development, 41(1), 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.12.005

- Wang, S. [Sangui], Zeng, J., Shi, Y., Luo, R., & Zhang, L. (2012). Poor western regions pupils’ differences in gender, health and education. Journal of Agrotechnical Economics, 6(1), 4–14. [in Chinese]

- Wang, S. [Shanmai]. (2008). Analysis on the policy of “key schools” in Chinese basic education. Educational Research, 3(338), 64–66. [in Chinese].

- Wang, X., Liu, C., Zhang, L., Luo, R., Glauben, T., Shi, Y., Rozelle, S., & Sharbono, B. (2011). What is keeping the poor out of college? Enrollment rates, educational barriers and college matriculation in China. China Agricultural Economic Review, 3(2), 131–149. doi:10.1108/17561371111131281

- Wang, X., Liu, C., Zhang, L., Shi, Y., & Rozelle, S. (2013). College is a rich, Han, urban, male club: Research notes from a census survey of four tier one colleges in China. The China Quarterly, 214, 456–470. doi:10.1017/S0305741013000647

- West, M. R., & Wöβmann, L. (2006). Which school systems sort weaker students into smaller classes? International evidence. European Journal of Political Economy, 22(4), 944–968. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2005.07.002

- Wilson, W. J. (1996). When work disappears: The world of the new urban poor. New York, NY: Alfred Knopf.

- Wong, M. S. W., & Watkins, D. (2001). Self-esteem and ability grouping: A Hong Kong investigation of the Big Fish Little Pond effect. Educational Psychology, 21(1), 79–87. doi:10.1080/01443410123082

- Woolcock, M. (1998). Social capital and economic development: Toward a theoretical synthesis and policy framework. Theory and Society, 27(2), 151–208. doi:10.1023/A:1006884930135

- Wooldridge, J. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Xinhua. (2010). Setting up the “key schools”, exams for tracking placement [in Chinese: Qiao Li Ming Mu She “Zhong Dian Ban”, Fen Ban Kao Shi Pai Man Kai Xue Ji]. Retrieved from http://education.news.cn/2015-09/06/c_128198766.htm

- Xu, T., Hu, N., & Mao, M. (2009). The pay-for-performance reform in China’s compulsory education: Rewarding us with our own money? China Southern Daily. Retrieved from http://www.jyb.cn/basc/sd/200911/t20091112_323118.html

- Xue, H., & Ding, X. (2009). A study on additional instruction for students in cities and towns in China. Educational Research, 30(1), 39–46. [in Chinese]