Abstract

Prior research in Applied Linguistics has explored how teachers mobilise diverse resources in order to make connections between the students’ out-of-school knowledge and experiences and the abstract content knowledge. Nevertheless, how teachers can transcend the boundaries of disciplinary knowledge by incorporating relevant content knowledge from other academic subjects to facilitate students’ learning of new content knowledge is a topic that is under-researched in the field. Adopting translanguaging as an analytical perspective, this study examines how the creation of a translanguaging space can afford opportunities for an English-Medium-Instruction (EMI) teacher to connect content-related knowledge for supporting students’ learning of new historical knowledge in EMI Western History classrooms. The data is based on a larger linguistic ethnographic project in a Hong Kong EMI secondary Western History classroom. Multimodal Conversation Analysis is used to analyse the classroom interaction data. The classroom interaction data is triangulated with the video-stimulated-recall-interviews that are analysed with Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. This paper argues that a translanguaging classroom space can be created for activating students’ prior learnt subject knowledge for supporting students’ learning of new academic knowledge. Such a translanguaging space provides opportunities for classroom participants to not only engage in fluid language practices, but also encourages the teacher and students to bring in multiple epistemologies that help students understand new academic knowledge in a new classroom interactional context.

1. Introduction

Generally understood as the use of English to teach academic subjects in contexts in which the first language (L1) of the majority of the population is not English, English Medium Instruction (EMI) has become a global education phenomenon (Dearden Citation2014; Macaro et al. Citation2018; Macaro Citation2020). Though EMI tends to adopt a monolingual ideology which constraints the use of languages other than English during instruction, researchers have found tensions between the policy and practice of EMI concerning the issue of language choice by teachers and students (e.g. Aizawa and Rose Citation2019). Recent research has demonstrated how EMI teachers and students use multiple linguistic, multimodal and sociocultural resources to challenge the imposed EMI policy and free themselves up through using multiple resources that they have access to in learning content knowledge. For example, Tai and Li (Citation2021a, Citation2021b, Citation2021c) studies in Hong Kong (HK) EMI secondary mathematics classrooms have noted how EMI teachers mobilise linguistic resources other than English and diverse semiotic resources to support multilingual students’ learning of new academic knowledge.

Prior research studies have demonstrated how teachers can bring outside knowledge or everyday life experience into EMI classrooms for scaffolding students’ learning of academic knowledge. Lin (Citation2006) has illustrated how EMI science teachers employ students’ L1 to help students learn the technical scientific terms by connecting them with everyday life knowledge or real-life experiences familiar to the students. Tai and Li (Citation2020) study is one of the very few studies that adopt translanguaging as an analytical perspective to investigate how an EMI teacher’s translanguaging practices can afford opportunities for him to integrate out-of-school knowledge and experience into the EMI mathematics lessons in order to enhance students’ learning of abstract mathematical concepts. Nevertheless, there is a lack of research that explicates how EMI teachers can bring the different content-related knowledge that students have learnt from other academic subjects into the teaching of new academic knowledge, thereby linking students’ past learning experiences and past knowledge and consolidating students’ content learning.

Based on the data collected from a larger linguistic ethnographic study in a Hong Kong EMI secondary Western History classroom, this paper adopts translanguaging as an analytical perspective in order to address the following research question:

How does the EMI Western History teacher connect different content-related knowledge that students have learnt from different timescales for scaffolding students’ learning of new academic knowledge?

Multimodal Conversation Analysis (MCA) is used to conduct a detailed analysis of the classroom discourse. The analyses of the classroom discourse are triangulated with the video-stimulated-recall-interview data which are analysed using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) in order to provide additional insights into the teacher’s reflections on his pedagogical strategies. Understanding how teachers can mobilise translanguaging practices for connecting relevant content knowledge or concepts from other curricula to the teaching of new content knowledge can offer insights into ways to transform the classroom into an inclusive translanguaging space (Tai Citation2022a) for transcending disciplinary boundaries, recognising the value of different kinds of content knowledge and broadening students’ perspectives.

2. Bringing prior knowledge and experiences into classroom interaction

Research in applied linguistics has studied how teachers can connect students’ prior knowledge and life experiences and the subject knowledge that they learn in school in order to engage students’ learning. In the context of English-for-Speakers-of-Other-Languages (ESOL) classrooms, Cooke and Wallace (Citation2004) argue that the students bring to the class considerable cultural, linguistic and life experience resources in the ESOL classrooms to facilitate the process of meaning-making. Similarly, Tai and Brandt (Citation2018) examine how an ESOL teacher employs embodied enactments in an adult beginning-level ESOL lesson in order to explain how the specific vocabulary items can be deployed in particular social contexts and hence bridging the gap between classroom interaction and real-life L2 use. Moreover, Waring and Yu (Citation2018) argue that engaging in life outside the ESOL classroom is an important resource for learning target linguistic items and fostering conversation, which is crucial for promoting students’ L2 development.

Scholars in educational research have also coined the term ‘cross-curricular connection’ which emphasises the teacher’s conscious effort to connect knowledge, principles and/or values from different academic disciplines to facilitate the teaching of a central topic or theme (Jacobs Citation1989). It aims to address some of the recurring issues in education, including fragmentation and isolated skill sets governed by separate academic disciplines (Haynes Citation2002). That is, the cross-curricular connection encourages teachers to transcend rigid subject boundaries and tap into students’ prior knowledge and skills that are gained from other subject teachings. In doing so, it builds students’ knowledge and understanding of the new subject knowledge and its relationship to other discipline(s) (e.g. Gardner and Mansilla Citation1994; Vella Citation2015). Although existing research has provided some empirical evidence in terms of how teachers can bring the outside into the classroom for facilitating content and language learning, these research studies focus on the role of connecting everyday life knowledge or out-of-school knowledge with academic knowledge. There remains a limited understanding of how teachers and students bring in relevant content knowledge that is learnt or acquired from other subjects in order to enable students to recognise how the new knowledge is related to their prior learnt content knowledge from other academic subjects. In order to fill in the research gap, I specifically examine how a translanguaging space can afford opportunities for an EMI Western History teacher to transcend disciplinary knowledge by drawing on students’ prior historical knowledge that they have learnt in Chinese History lessons for enhancing students’ understanding of the historical events in the West.

3. Translanguaging in EMI classroom interactions

The notion, translanguaging, derives from the Welsh term ‘trawsieithu’ which initially referred to pedagogical practice in bilingual classrooms where teachers and students deliberately altered languages of input and output (Williams Citation1994). As a Welsh-inspired notion, translanguaging views language as a multilingual, multimodal, multisensory and multi-semiotic entity which enables intelligibility beyond the named languages and language varieties (Li Citation2018). Translanguaging also encompasses different terminology to define language alternation, including ‘code-switching’ and ‘code-meshing’, that commonly explain the use of L1 as a result of a deficiency in L2. Instead of translating from one named language to another, translanguaging highlights the dynamic and fluid knowledge-building processes through the employment of various multilingual resources, including different registers, variations, and ways of speaking, as well as multimodal resources, such as gestures and body movements (Li Citation2018; Tai and Li Citation2021a, Citation2021b, Citation2021c). From a translanguaging lens, multilinguals are provided agency to employ various linguistic and semiotic resources creatively and critically to challenge the traditional configurations, categories, and power structures, and construct new meanings through interactions. For instance, multilinguals can borrow and rework each other’s words, appropriate and re-appropriate gestures, signs, and images from all sources for enabling sense- and meaning-making.

As a pedagogical resource, translanguaging encourages teachers and students to use their available multilingual, multimodal, multi-sensory and multi-semiotic resources to challenge the monolingual language education policy, equalise the hierarchy of languages in the classrooms and enable students’ full participation in creating meanings during classroom interactions. The act of translanguaging is transformative in nature as it creates a translanguaging space for classroom participants to bring together different sociocultural dimensions, including multilinguals’ linguistic, cognitive and social skills, their knowledge and experience, attitudes and beliefs, values and identities as resources in the process of constructing meaning (Li Citation2011). Such a translanguaging space is created for and created by translanguaging and this can potentially give voice to students who are silenced by the monolingual policy in multilingual classrooms (Li and Zhu Citation2013). Hence, translanguaging can be a way for fostering equity and social justice. According to García, Johnson, and Seltzer (Citation2017), teachers need to take proactive actions in order to create a translanguaging space in the classrooms. They propose three features, translanguaging stance, translanguaging design, and translanguaging shifts, for promoting dynamic translanguaging practices. A translanguaging stance refers to the teacher’s philosophical orientation that is informed by beliefs of joint collaboration. This entails aspects such as students’ multilingual practices and cultural understanding, students’ families and communities and teachers’ understanding of the classroom as a transformative space for fostering equity. The translanguaging stance highlights the value of the linguistic and cultural knowledge that language users already have as legitimate resources for providing alternative points of reference for knowledge production and enabling students’ success in education. As García et al. (Citation2021) argue, through rejecting the raciolinguistic ideologies that have enregistered bi/multilinguals as deficient, translanguaging encourages us to attend to racialised bi/multilinguals’ knowledge and abilities instead of trying to remediate them. García, Johnson, and Seltzer (Citation2017) also emphasise the significance of including translanguaging design in planning their lessons, and also a translanguaging shift, which refers to the teacher’s ability to make moment-by-moment decisions in classrooms based on students’ learning needs and feedback. The theorisation of translanguaging shift aligns with Tai’s (Citation2022b) reconceptualization of teacher contingency which highlights the teacher’s ability in orchestrating the available linguistic and multimodal resources to construct pedagogical actions spontaneously, with the aim of managing instructional efficacy and facilitating students’ learning opportunities.

Additionally, Cenoz and Gorter (Citation2017) have argued that translanguaging can be sustainable for promoting and protecting minority languages when teachers are adopting appropriate pedagogical strategies. They have developed five guiding principles for teachers to balance between using resources from the multilingual students’ repertoire and creating contexts for facilitating the use of minority languages in educational contexts where students need to develop literacy skills in at least two languages (the majority and the minority) and also communicative competence for using minority language for engaging in informal interaction. The guiding principles include: 1) designing breathing spaces for employing the minority language at school; 2) using the minority languages through translanguaging; 3) using multilinguals’ resources to reinforce all linguistic knowledge through enriching students’ metalinguistic awareness and activating students’ prior linguistic knowledge; 4) enhancing students’ language awareness and 5) making the connection between spontaneous and pedagogical translanguaging in order to raise students’ awareness regarding the use of minority languages in different situational contexts.

As Macaro (Citation2018: 19) suggests, EMI is defined as ‘the use of the English language to teach academic subjects (other than English itself) in countries or jurisdictions where the L1 of the majority of the population is not English’. Based on this perspective, EMI teachers are encouraged to limit their L1 use in order to create authentic communicative contexts for the use of English (i.e. the target L2). This can potentially support students in developing higher English proficiency levels while concurrently achieving content learning. However, recent scholarship on translanguaging pedagogy has been arguing that a flexible and multilingual pedagogy facilitates rather than hinders learning, both of the L2 and the subject matter, than a monolingual-only approach (e.g. García and Li Citation2014; Li Citation2018).

In comparison to studies on the use of L1 in L2 learning settings (e.g. Ustunel and Seedhouse Citation2005), there are fewer studies which investigate L1 use in the EMI context. These studies typically employ naturalistic observations to investigate teachers’ spontaneous use of L1 in order to identify good pedagogical practices (e.g. Lin Citation2006; Gierlinger Citation2015; Lo Citation2015; Lo and Lin Citation2019). For example, Lo (Citation2015) aims to understand whether EMI teachers can use L1 appropriately to address their students’ needs. Through conducting discourse analysis to study the classroom interaction qualitatively, it is noticeable that the EMI teachers tend to switch to L1 for explaining difficult concepts and subject-specific vocabulary in order to make the content comprehensible for the students. More recently, Lo and Lin (Citation2019) explore how EMI teachers teaching various content subjects can systematically use L1 in order to maximise the effectiveness of EMI both in content and language learning. The findings illuminate that strategic use of the combination of the L1 and the L2 is particularly beneficial for low English proficiency students who needed more language support.

Recent research has investigated the construction of translanguaging spaces in EMI classrooms. A study by Jakonen Szabó and Laihonen (Citation2018) has investigated how a student’s translanguaging practices subvert the English-only norm in a junior secondary Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) history classroom in Finland and is treated as ‘language mixing’ by other peers. The analysis illustrates that the student’s translanguaging practices involve deploying a wide range of linguistic resources, through combining lexical items and grammar of English and Finnish and uttering English words with a stereotypical Finnish accent, to create a linguistic form which is highly creative and hybrid. Tai and Li (Citation2020) reveal the ways the EMI mathematics teacher constructs an integrated translanguaging space by bringing the students’ everyday life knowledge into the EMI institutional learning space in order to turn the classroom into a lived experience. This allows the teacher to create a translanguaging space for bringing out-of-school knowledge as a legitimate resource in the classroom where the teacher and students fully build on their social, cognitive and linguistic knowledge for scaffolding content learning. Tai’s (Citation2022b) study reconceptualises the notion of teacher contingency and argues that the process of how the teacher contingently responds to the unexpected outcomes that arise in real-time interactions is a process of translanguaging. The study focuses on teacher contingency in creating a translanguaging space for expanding the EMI history teacher’s choice and agency for utilising diverse linguistic and multimodal resources for constructing his contingent actions.

Although there are considerable studies on the ways for creating translanguaging spaces in supporting students’ content and language learning, there is a distinctive lack of research which examines how a translanguaging space can be created to bring relevant content knowledge from other subjects into the EMI classrooms for facilitating the learning of new content knowledge. Building on Tai and Li (Citation2020) study on bringing out-of-school knowledge into EMI classrooms, this study specifically examines how a translanguaging space can enable the EMI Western History teacher to transcend disciplinary boundaries and make a cross-curricular connection in order to enrich students’ understanding of new western historical events.

4. EMI in Hong Kong

Whilst medium-of-instruction policies in HK are broadly set for primary and university education, the medium-of-instruction policy at the secondary level has gone through immense changes (Poon Citation2010). HK’s secondary schools have witnessed three key stages in development with regard to medium-of-instruction policies. These include: (1) the laissez-faire policy prior to 1994; (2) the compulsory Chinese-Medium-Instruction (CMI) policy during 1998–2010 which allowed 114 secondary schools to use EMI to teach content subjects while the remaining 307 schools were mandated to use CMI; and (3) the fine-tuning medium-of-instruction policy since 2010. The fine-tuning policy is in part responding to the parental desire for their children to be educated in EMI settings. Under the fine-tuning policy, secondary schools are allowed to offer EMI classes, partial-English-medium classes (i.e. one or two subjects conducted in EMI) and/or CMI classes. CMI schools have the autonomy in selecting their medium-of-instruction for content subjects if they have met certain criteria (Education Bureau Citation2009). As a result, many secondary schools are offering EMI classes and it is estimated that approximately 30% of the schools are using EMI for all grade levels and around 40% of the schools are adopting EMI for at least one content subject.

Research studies (e.g. Poon, Lau, and Chu Citation2013; Chan Citation2013, Citation2014) have demonstrated that the fine-tuning policy has its limitations. Although the government has provided specific criteria for schools to provide EMI classes, placing students into EMI classes does not mean that learning will take place in the classrooms automatically (Chan Citation2013, Citation2014). Therefore, this investigation aims to demonstrate how a translanguaging approach can be adopted at the local level in order to resolve the difficulties that are currently faced by teachers and students in teaching and learning through EMI.

5. Data and methodology

5.1. Data collection

Data were collected at a prestigious EMI secondary school in HK. The school is a local EMI secondary school, which provides education from year 7 to year 12 based on the curriculum guides set by the HK Education Bureau. The school uses English to deliver most of the lessons (excluding Chinese language and literature, Chinese History, liberal studies and Mandarin classes), and school assessments are evaluated through English. The school’s language policy emphasises promoting students’ English proficiency and the English department has developed a number of initiatives in order to create a rich English-speaking environment for all teachers and students. For instance, all teachers are expected to use English as the only code for teaching content subjects. The reason for selecting this school was because I was well aware of the school’s organisational structure and the school curriculum.

The HK Education Bureau Curriculum Development Council proposed Chinese History and Western History as two separate academic subjects. According to the Chinese History curriculum guide, year 7 students are expected to learn about the historical period from pre-historic times to the Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties. The learning focus is on the origin of the Chinese ethnicities and the formation of early regimes. On the other hand, the Western History curriculum expects year 7 students to learn about the ancient period from the pre-historic period to the 14th century. The learning focus is on the birth and continuous development of regional civilisations in contributing to the progress of contemporary human civilisation.

The Western History teacher who agreed to participate in this study has taught for more than 21 years at the participating school and serves as Head of Western History at the school. He is a native speaker of Cantonese, fluent in English. He attended EMI schools for his own secondary and university education. A one-hour semi-structured interview was conducted with the teacher before classroom observation in order to understand the teacher’s attitudes towards using multiple languages in the EMI Western History classroom.

In the selected year 7 class, there were 30 students and, according to the teacher, students’ English proficiency level and general academic performance were below average among their cohort. This class was selected since the students were willing to allow observation of the class when asked. Although their academic performance was below average, in comparison to other classes in the same cohort, the students in this class displayed their willingness in contributing to the class discussion, which could potentially allow an understanding of how a translanguaging space could be carved out during classroom interactions. These students had received at least 6 years of primary education, where Cantonese was employed as the Medium-of-instruction and English was taught as an L2. All students spoke Cantonese as their L1 and were born in HK. Classroom observations were carried out in the year 7 class for two months from October to November 2020. Eleven 30-min lessons were observed and video-recorded. Informal interviews were carried out with the teacher and students during the observational period in order to obtain information regarding the observed lessons. A one-hour post-video-stimulated-recall-interview was conducted with the teacher in order to allow the researcher and the teacher to achieve a shared understanding of the roles of the teachers’ own translanguaging practices in the EMI Western History classroom.

An important issue related to my subjectivity has to be addressed. As a former student of this school, I can draw on that position and on my experience as a qualified English-as-a-second-language teacher to provide a type of insider view. While I understand my subjective position could lead to possible bias, I attempt to ‘bracket’ my assumptions or biases during the data analysis stage (Larkin, Eatough, and Osborn Citation2011). That is, through ‘bracketing’ my pre-existing expectations or prejudices, I aimed to provide in-depth and complex interpretations of different translanguaging practices through MCA analysis and member check by video-stimulated-recall-interviews.

5.2. Data analysis

This study combines Multimodal Conversation Analysis (MCA) with Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) to investigate the complexity of translanguaging practices. The combination of MCA and IPA is inspired by Li’s (Citation2011) proposal of moment analysis. Moment analysis, which draws on the analytical approaches of MCA and IPA, focuses on analysing how language users break boundaries between named languages and non-linguistic semiotic systems in particular moments of social interaction. Li (Citation2011) argues that it is important to understand what prompts a specific social action at a particular moment of the interaction and the consequence of the action. In order to carry out the analysis, researchers need to collect various data sources. As Li (Citation2011) suggests, researchers need to collect both the observation and audio/video recordings of naturally occurring interactions and metalanguaging data (i.e. speakers’ commentaries on their language use). Collecting metalanguaging data enables researchers to better understand the process of language users attempting to make sense of their experiences.

MCA is used as the main analytical framework in the present study. MCA adopts an emic/participant-relevant perspective in order to focus on ‘how social order is co-constructed by the members of a social group’ (Brouwer and Wagner Citation2004: 30) through conducting fine-grained analysis of the social interaction. The analytic stance of MCA requires researchers not to pre-theorise the relevance and importance of language-in-use, which entails semiotic resources including eye gaze and gestures. The analytical focus must be on sequences instead of on isolated turns or utterances (Hutchby and Wooffitt Citation1998). MCA extends Conversation Analysis by incorporating multimodal actions, such as gaze, gestures and manipulations of objects, in which the translanguaging perspective perceives multimodal actions as integral to social interaction as linguistic utterances. The data were transcribed using Jefferson’s (Citation2004) and Mondada’s (Citation2018) transcription conventions (see Appendix). In the analysis, I also employed screenshots from the video recordings to illustrate multimodal interactions in the EMI Western History classrooms.

I triangulate the MCA findings with the video-stimulated-recall-interview data which was analysed using IPA. IPA allows us to understand how the teacher views his translanguaging practices at particular moments in the interactions. IPA follows a dual interpretation process called ‘double hermeneutic’. This requires researchers to try to make sense of the participants trying to make sense of their world (Smith, Flowers, and Larkin Citation2013). This allows analysts to take an emic approach to make sense of the teacher’s personal experience. In order to present the IPA analysis in a reader-friendly way, a table with four columns was designed in order to help readers to comprehend how the researcher made sense of the EMI teacher attempting to make sense of his own teaching practices. From left to right, the first column included the classroom interaction transcripts. The second column entailed the video-stimulated-recall-interview excerpts. The third column demonstrated the teacher’s perspectives on his pedagogical practices at that moment of the classroom interaction. The last column recorded the researcher’s own interpretations of the teacher’s perspectives, which corresponds to IPA’s two-stage interpretation process (i.e. double hermeneutic).

6. Analysis

Two classroom extracts are analysed in order to illustrate how the EMI history teacher creates a translanguaging space by bringing related content knowledge into the teaching of new academic knowledge (Extract 1) and facilitating students’ initiatives in making connections between the new content knowledge and their prior learnt subject knowledge (Extract 2). These extracts are typical examples of the interaction. The analysed extracts are interrelated to illustrate the typical instances of translanguaging practices in the EMI classroom (ten Have Citation1990).

Extract 1: Drawing on Related Historical Knowledge to Scaffold Content Knowledge

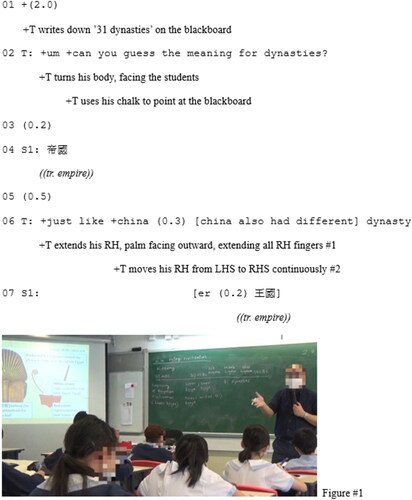

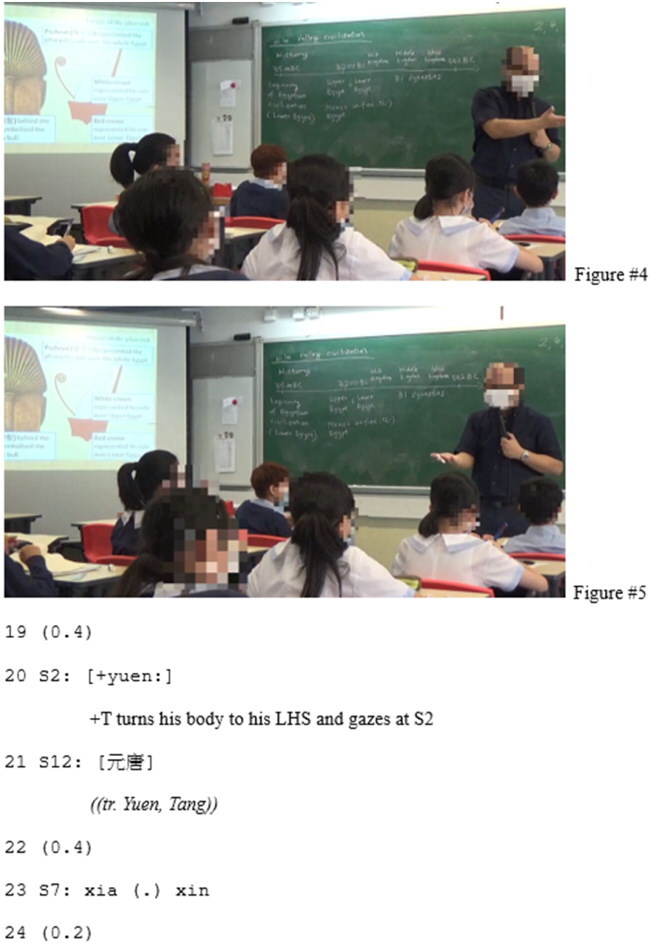

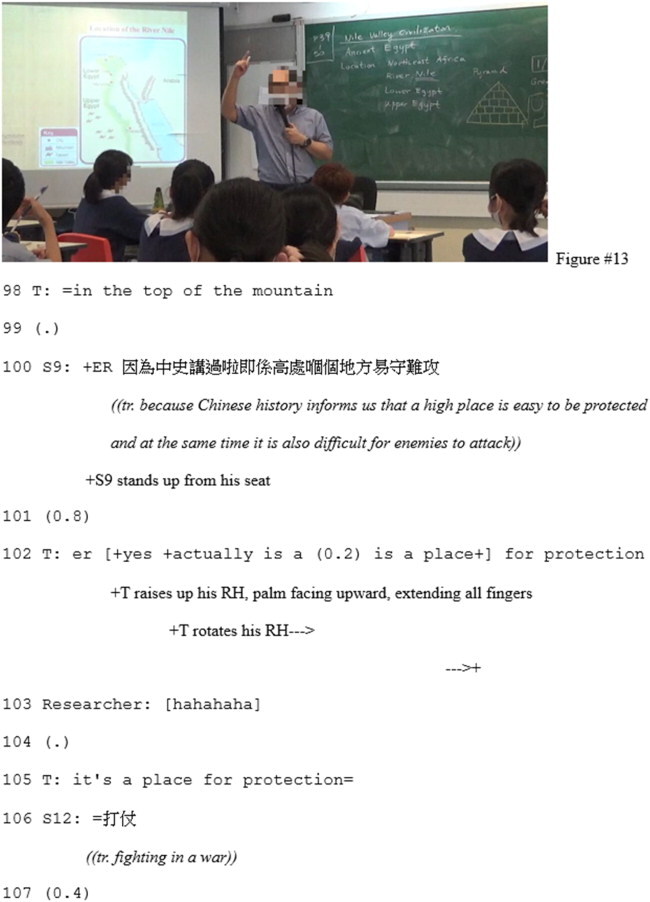

Prior to the extract, the teacher (Mr. PangFootnote1) was introducing the development of the Nile Valley civilization. The PowerPoint slide () illustrates the symbolisms of the different features of the Pharaoh’s crown. On the blackboard, Mr. Pang constructed a timeline which included important events that happened in the 3500BC, 3200BC and 320BC. T subsequently introduced the fact that Egypt had 31 dynasties. In lines 1-2, Mr. Pang writes down ‘31 dynasties’ on the timeline and he invites students to guess the meaning of the word ‘dynasties’.

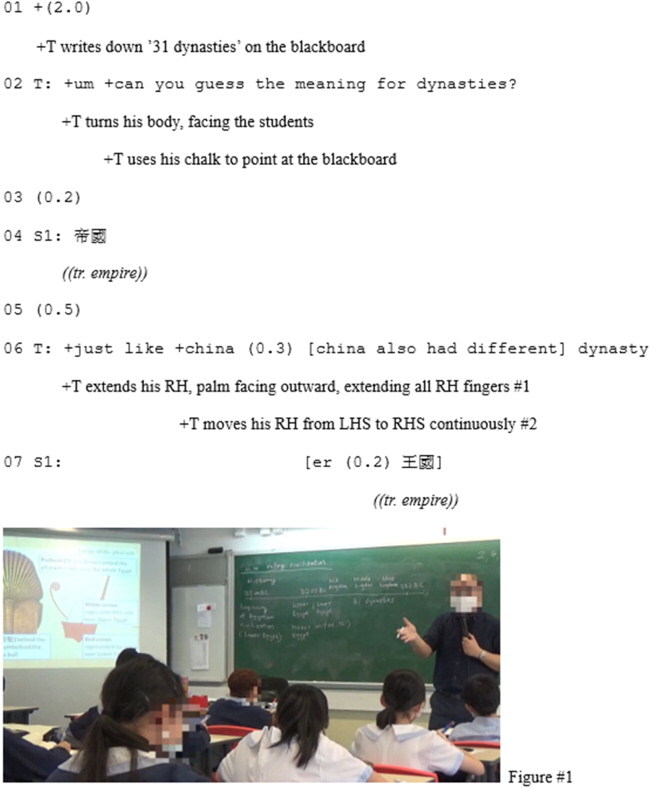

In the extract, it is evident that students (e.g. student 1, Cherry and student 12, Ken) use Cantonese to respond to Mr. Pang (e.g. lines 4, 7, 8, and 9), while Mr. Pang uses both Cantonese and English to provide feedback (e.g. line 6 and 10) plus initiating a Designedly Incomplete Utterance (DIU) ‘in china we have:’ (Koshik Citation2002), to invite students to think about the dynasties in Chinese History (line 10). So far, it is evidenced that the students are using Cantonese to respond to Mr. Pang’s question, but Mr. Pang attempts to deploy English to respond to student’s questions, hence orienting to English as the medium-of-interaction in the classroom (Bonacina and Gafaranga Citation2011).

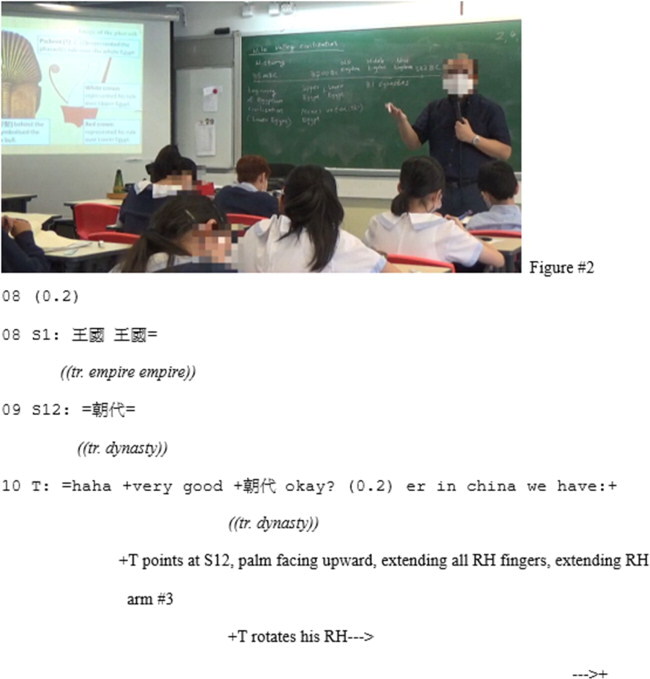

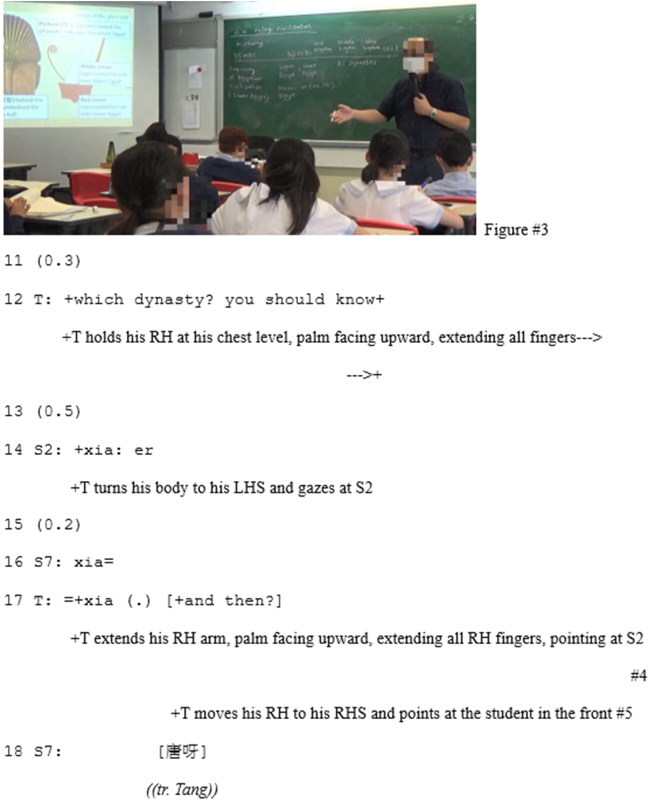

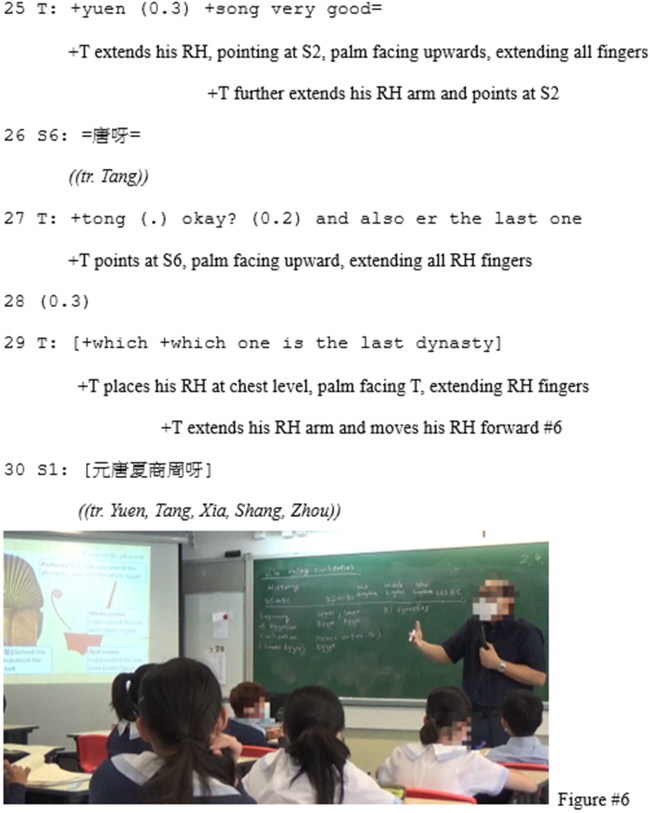

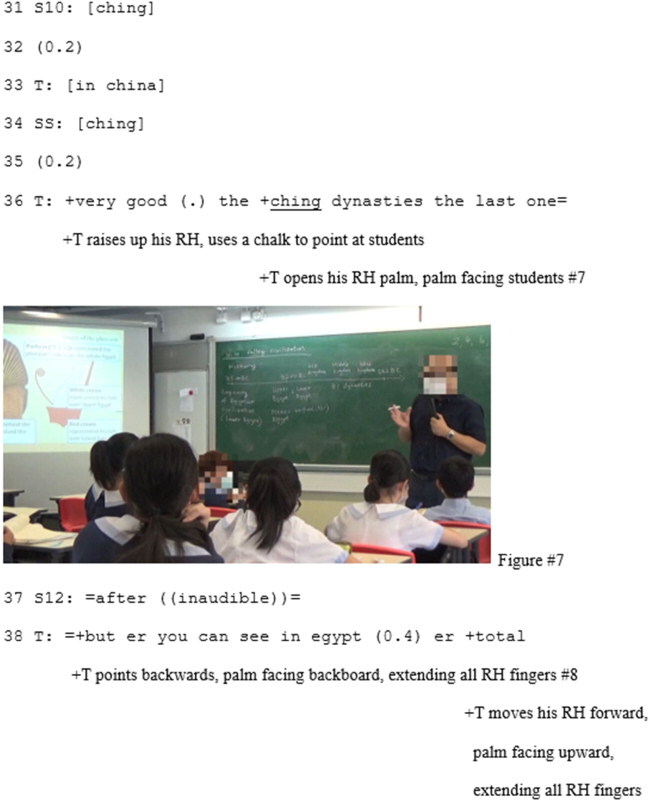

After a short pause (line 11), Mr. Pang notices that his use of DIU fails to elicit any response from students. He then forms a question, ‘which dynasty?’, and clearly states that ‘you should know’ (line 12), which implies that all students in the class should have prior knowledge about the Chinese dynasties. Here, it is evident that Mr. Pang is trying to bring students’ prior knowledge into the learning of Egyptian History. It is possible that Mr. Pang assumes students to have learnt Chinese dynasties in their Chinese History class. Student 2 (Jerry) takes a turn to initiate a response ‘Xia’, which is the first dynasty in Chinese History. Jerry’s response is positively evaluated by Mr. Pang (line 17) and several students begin to offer their responses in either Cantonese or English, such as ‘唐呀 (Tang)’ in line 18, ‘Yuen’ in line 20, ‘元唐 (Yuen and Tang)’ in line 21 and ‘Xia’ and ‘Xin’ dynasties in line 23. In line 25, Mr. Pang acknowledges students’ contributions by repeating their responses (lines 25 and 27).

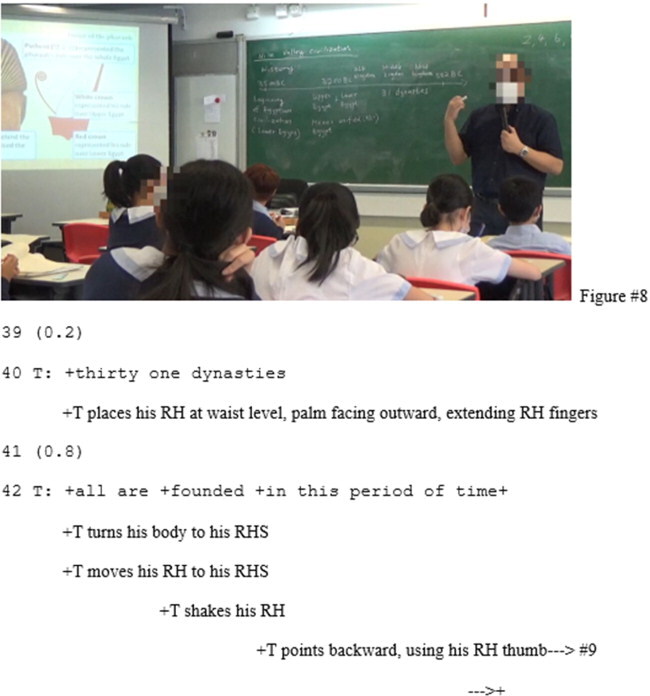

In lines 27 and 29, Mr. Pang prompts students to name the last dynasty in China. He invites students to look at the timeline on the blackboard which presents the historical timeline of the development of the Egyptian civilisation. By pointing backward (figure #8) and verbally inviting students to imagine ‘Egypt’ on the blackboard as he says ‘but er you can see in egypt’ (line 38), Mr. Pang is bringing students back to the learning of Egyptian History by metaphorically referring to the timeline as Egypt. After stating the fact that there are ‘thirty one dynasties’ in Egypt (line 40), Mr. Pang repeats his gesture by pointing backwards with his thumb to draw student’s attention to the timeline on the blackboard while verbally saying that these dynasties ‘are founded in this period of time’ (line 42).

This extract reveals that Mr. Pang brings students’ prior knowledge of Chinese dynasties into the teaching of ancient Egyptian History. Since Mr. Pang is aware that Chinese dynasties are taught in Chinese History lessons, he utilised this knowledge to encourage students to bring in knowledge learnt in other content areas to this translanguaging space. By doing so, Mr. Pang mobilises various multimodal resources (pointing for acknowledging student’s contributions and extending arms to invite responses) alongside his follow-up questions in English and repetition of students’ Cantonese responses to engage students in learning the meaning of dynasty and the existence of various dynasties in Egyptian History. It is evident that the students display their understanding of the meaning of ‘dynasty’ as they use Cantonese to offer examples of different Chinese dynasties. In the video-stimulated-recall-interview, Mr. Pang comments on his rationale for drawing on Chinese History to facilitate his teaching ():

Mr. Pang explains that bringing the historical knowledge that students have learnt from the Chinese History lessons into the classroom can help them to understand the ancient Egyptian dynasties. It is possible that Mr. Pang is aware of the Chinese History curriculum and having such an awareness allows him to draw on Chinese dynasties as an example to scaffold students’ understanding of ‘dynasty’ in Egyptian history. As shown in the MCA analysis, Mr. Pang successfully draws on students’ funds of knowledge and engages students’ learning as students are able to provide examples of different Chinese dynasties. Hence, by bringing relevant historical knowledge into the history classroom, this affords Mr. Pang to construct a translanguaging space. Such a space allows Mr. Pang to understand and assess the current state of the student’s knowledge in the learning process.

Extract 2: Facilitating the Students’ Initiatives in Bringing related Historical Knowledge into the Learning of New Historical Knowledge

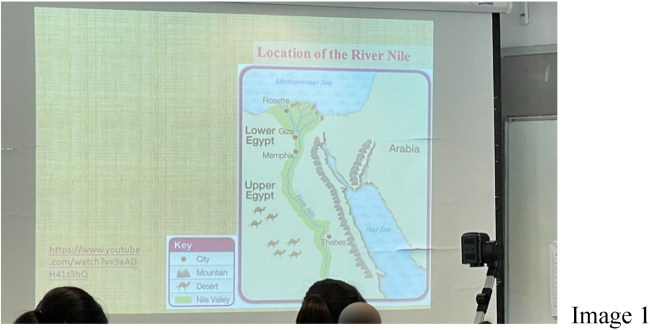

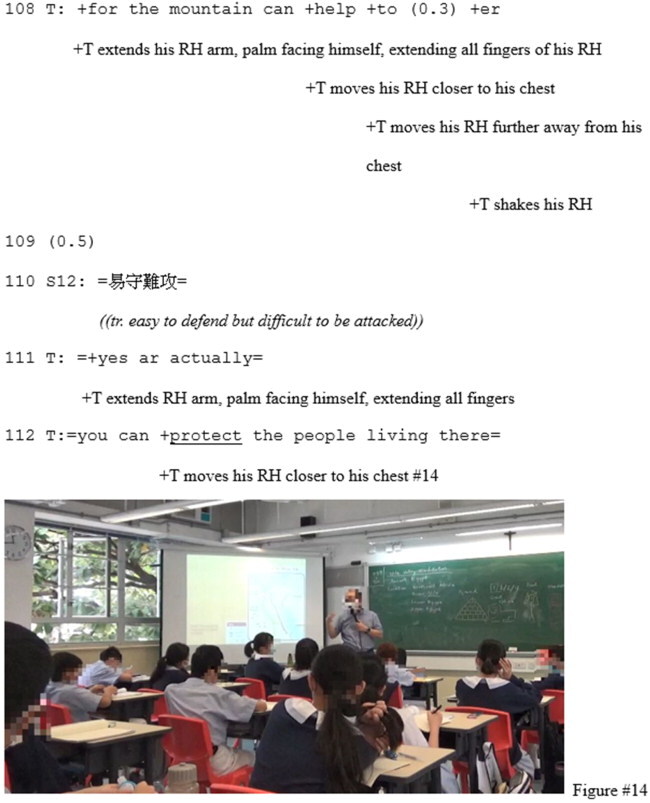

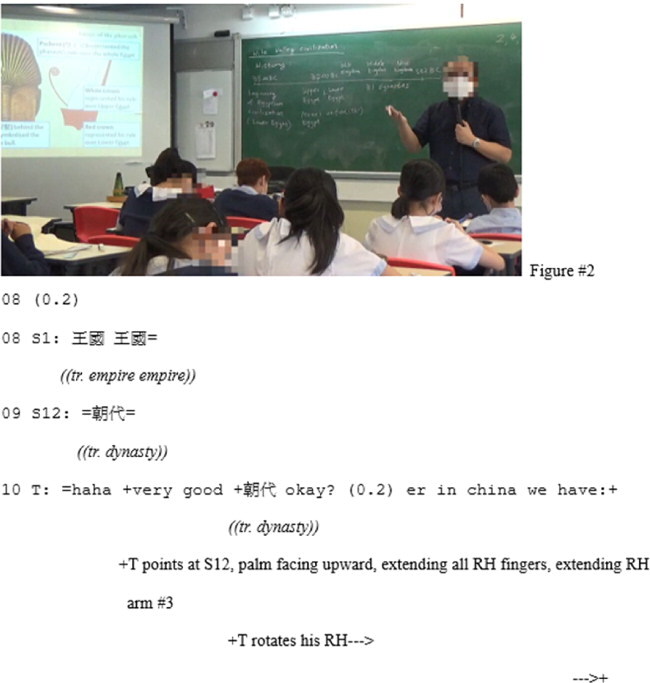

Prior to the extract, Mr. Pang was directing students’ on the PowerPoint on the screen which displayed the map of the Nile Valley civilization (see Image 1). Mr. Pang explained the geographical features surrounding the Nile, including the river, the large mountain and the desert located in Upper Egypt. In line 54, Mr. Pang invites students to discuss which location the students would like to live in if they were ancient Egyptians.

Extract 2

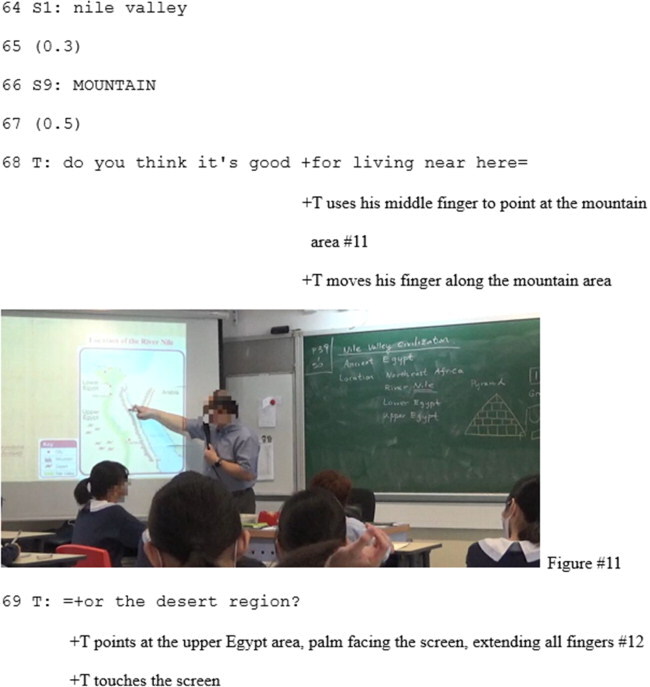

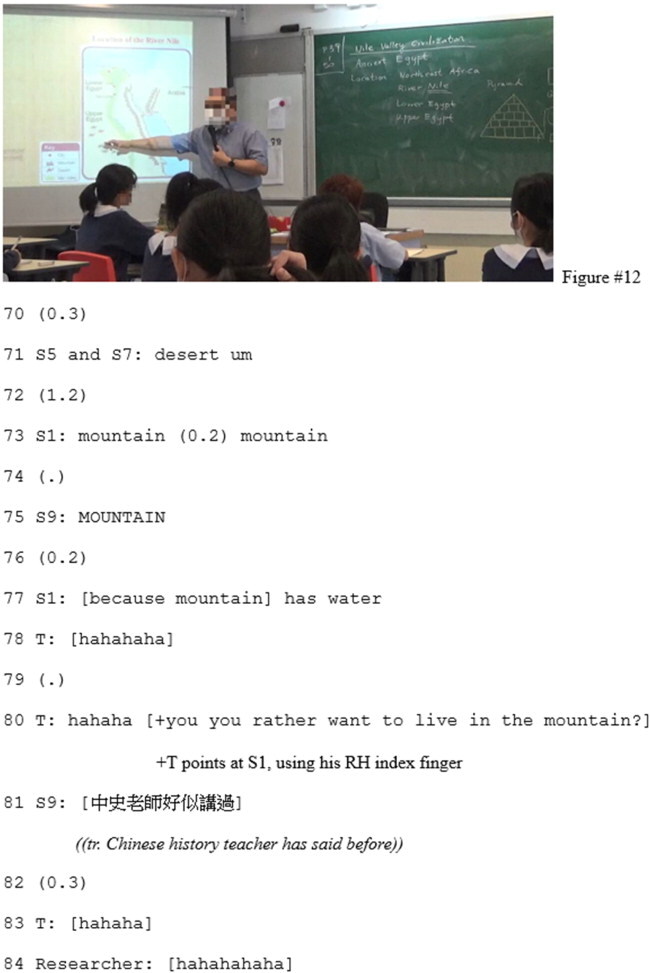

In lines 54-62, Mr. Pang initiates a direct question and invites students to think about the location where they would settle if they wished to make a living. Students are given three options to choose from. They can either live near the river, at the top of the mountain or in the desert region. Mr. Pang rephrases the question (lines 68-69) and points to the mountain area (figure #11) and ‘the desert region’ (line 69, figure #12) in order to prompt further students’ responses. This leads to several students taking up turns (lines 71-77) in expressing their preferences. Particularly, Cherry offers a brief explanation of the reason for living at the top of a mountain, “because mountain has water” (line 77). Mr. Pang first laughs in response to Cherry’s answer and nominates Cherry to further explain her preference in choosing to live in the mountain (line 80).

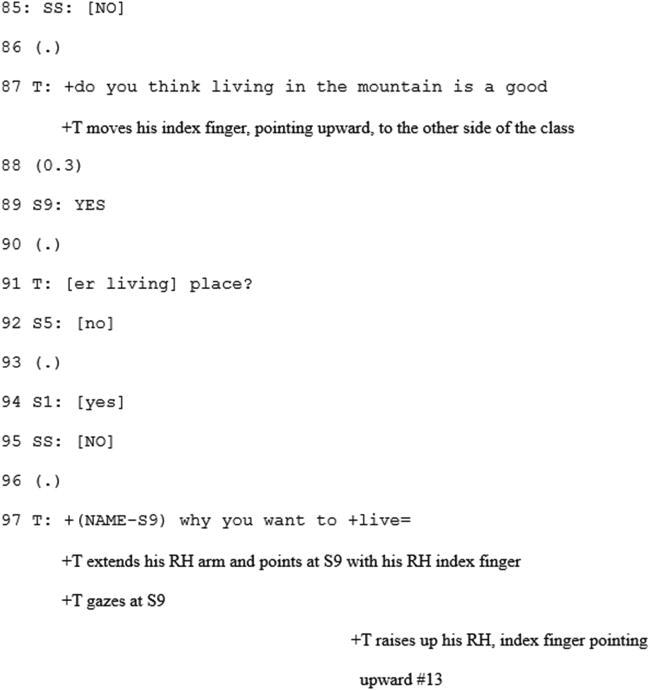

In line 81, student 9 (John) uses Cantonese to express his thought about Mr. Pang’s question. Specifically, he refers to the knowledge that he has gained from his Chinese History lessons in order to make sense of Cherry’s preferred choice. Mr. Pang initiates the same question again in lines 87 and 91 which potentially invites Cherry’s participation in the class discussion. Instead, John takes the turn and switches back to English as he enunciates ‘YES’ in a loud volume to highlight his preference (line 89). This prompts Mr. Pang to invite John to elaborate on his preference to live in the mountain (lines 97-98). In line 100, John deploys Cantonese to respond to Mr. Pang’s question in lines 97-98. In particular, John recalls his Chinese History teacher explaining the role of a mountain range as a natural border to defend against attackers in wartime (line 100). Despite subverting the English-only EMI policy, John’s use of Cantonese, rather than L2 English, enables him to fluently construct the abstract argument for the whole class. This is possibly because John’s low English proficiency prevents him from expressing such an abstract argument in L2 English (fieldnotes).

In lines 102 and 105, Mr. Pang ties S9’s answer to the content subject by translating the Chinese idiom ‘易守難攻’ in English to the whole class, saying that it ‘is a place for protection’. This leads to an uptake from student 12 (Jerry) when he utters ‘打仗’ (i.e. fighting in a war)’ in Cantonese (line 106). Although Jerry does not employ the equivalent English translation that was verbally provided by Mr. Pang in line 102, such a translanguaging practice reflects Jerry’s understanding of the role of a mountain range in a battle. Mr. Pang continues his explanation by clarifying that the mountain can be a site for protecting ‘the people living there’ (lines 108-112). It is interesting to note that as Mr. Pang enunciates the verb ‘protect’ with stress, his gestural movement is in harmony with what is saying about protecting the people (line 112). By first extending his right arm (line 111) and then bringing it closer to his chest (Figure #14), Mr. Pang’s gestural movements metaphorically refer to the people retreating back to the mountain for safety reasons. Mr. Pang’s use of gesture further reinforces the strategic role of a mountain in defending against attackers in wartime.

Extract 2 reveals how John brings in relevant knowledge that he has learnt from his Chinese History teacher in order to justify his argument for living in the mountain if he were living in ancient Egypt. It is evidenced that Mr. Pang creates a translanguaging space by allowing students to deploy Cantonese to construct their responses, and mobilizing various semiotic resources, including gestural resources and the map of Nile valley in order to scaffold students’ understanding. Such a space is maintained by students’ use of diverse linguistic resources (i.e. English and Cantonese) for responding to Mr. Pang’s questions. It can be suggested that the creation of a translanguaging space enables Mr. Pang and students in the class to make sense of the connection between the knowledge about Chinese History brought by John and the historical knowledge related to ancient Egypt. In the video-stimulated-recall-interview, Mr. Pang reflects on the student’s uninvited initiative in bringing Chinese History into the learning of ancient Egyptian civilisation ():

Mr. Pang explains that he was expecting students to declare a preference for living near the ‘river’, since it is the preferred answer which reflects the historical fact in ancient Egypt. This demonstrates that the pedagogical goal for Mr. Pang at the moment of the interaction is to guide students in realising the benefits of living in river valleys which leads to the rise of ancient civilisation. Nevertheless, Mr. Pang notices that the students are offering different kinds of responses. This is reflected in the MCA analysis where some students suggest living on the top of the mountain. Although Mr. Pang considers the students’ responses as dis-preferred, Mr. Pang acknowledges that some of the student’s responses can be seen as valid. In the interview (lines 2-3), the researcher recalls his prior experiences in learning Chinese History as a year 7 secondary school student at the participating school. The Chinese History curriculum has a unit which covers the nature of different battles. Chinese historians argue that Chinese soldiers would choose to live in the mountain in defending against attackers during wartime. Mr. Pang recognises that such information comes from Chinese History, and he acknowledges that the students are able to use relevant content knowledge to support their argument. This is possibly the main reason which motivates Mr. Pang to allow students to translanguage in the interaction. Such a translanguaging space affords the students to bring in other subject knowledge in order to construct their arguments regarding the benefits of living in the mountain over living in river valleys.

7. Discussion and conclusion

The aim of the study is to illuminate how the EMI teacher constructs a translanguaging space which affords to bring relevant content knowledge that students have learnt into the learning of new historical knowledge in Western History lessons. Extract 1 illuminates the ways in which the teacher brings in relevant knowledge from the Chinese History curriculum to facilitate students’ understanding of the discipline-specific term ‘dynasty’. Throughout the process, the teacher repeatedly utilizes pointing gestures, Cantonese translations of the discipline-specific term, ‘dynasty’, and follow-up questions in English to engage students to identify the different dynasties in Chinese History. In the extract, it is noticeable that the teacher also allows several students to use Cantonese to name the dynasties in Chinese History. Although students’ Cantonese responses go against the monolingual EMI policy, such a multilingual translanguaging practice enables the teacher to assess the student’s understanding of the meaning of ‘dynasty’ and implicitly assists students to understand the Egyptian dynasties. In Extract 2, the teacher facilitates the process of students connecting their prior learnt knowledge from Chinese History lessons with the hypothetical question (i.e. the location that they would like to live if they were ancient Egyptians). Such a process involves the students using Cantonese as a linguistic resource to bring in relevant concepts and a specific idiom (i.e. ‘易守難攻’, easy to defend but difficult to be attacked) from Chinese History. The teacher’s translanguaging practices heavily rely on diverse gestural and visual resources which enable him to take the students’ Cantonese contributions and reify them by reframing them with more pedagogically relevant terminology in target L2 English.

A persisting concern for teaching Western History through an L2 is how EMI history teachers can facilitate classroom discussion in and through an L2. In particular, students are still developing their knowledge of L2 historical language and their L2 English proficiency while concurrently learning abstract historical recounts of the events (Tai Citation2022b). This paper argues that a translanguaging space can be created in an EMI classroom for activating students’ prior learnt subject knowledge for supporting students’ learning of new academic knowledge. Such a translanguaging space provides opportunities for classroom participants to not only mobilise a range of multilingual and multimodal resources to engage in fluid language practices, but also encourages teachers to bring in multiple epistemologies that help students understand the Western History lessons. This is reflected in the video-stimulated-recall-interviews where the teacher acknowledges the benefits of making cross-curricular links in assisting students to draw on the knowledge that they have learnt from other academic subjects to create relationships among various sources of information ( and ). Students are given the opportunity to expand their knowledge base and connect what they have learnt with what they are learning at the moment of the classroom interaction. Such an argument reinforces the value of creating a translanguaging space for transforming students’ old understanding and generating new knowledge (Li Citation2018; Zhu, Li, and Jankowicz-Pytel Citation2020). As Li (Citation2018) and Tai and Li (Citation2020) argue, the creation of a translanguaging space involves both teacher and students to bring in different sociocultural dimensions, including different kinds of academic knowledge and everyday life knowledge, as resources to challenge the monolingual EMI policy in their efforts to make the academic knowledge more relevant to the student’s learning experience.

Table 1. Video-stimulated-recall-interview (Extract 1).

Table 2. Video-stimulated-recall-interview (Extract 2).

It is vital to note that this study does not reveal any evidence that linking academic knowledge from one subject to another subject through translanguaging can result in better content and language learning. Although Chinese History and Western History are considered two subjects at the participating school and both subjects have different course objectives, it can be suggested that the study does not include any examples of how the teacher and students explicitly connect the subject-specific knowledge from a range of academic disciplines, such as science and geography, into the teaching and learning of Western History. Nevertheless, it is possible that integrating students’ prior learnt academic knowledge gained from subject teaching into the learning of new content knowledge in other subjects can potentially allow students to transcend the boundaries of disciplinary knowledge, advance students’ understanding of subject-specific concepts and expand the students’ perspectives as they recognise the relevance of different academic knowledge in learning new content knowledge. Future research can 1) explore how the creation of a translanguaging space in EMI classrooms enables teachers and students to connect a wide range of academic knowledge from different subjects into the learning of new content knowledge and 2) assess the learning outcomes of connecting relevant content knowledge from other subjects through translanguaging in EMI classrooms.

The findings contribute to the current literature on translanguaging and EMI education in numerous ways. The nature of EMI policy goes against the notion of translanguaging which challenges the necessity of only using one named language (i.e. English as the L2) as the medium to teach content subjects. The EMI policy may restrict opportunities for teachers and students with shared linguistic and cultural backgrounds to communicate effectively. As Li (Citation2021) argues, the promotion of English ‘as the language of science, knowledge, and internationalization is an ideological act’ (178) and such a monolingual policy contributes to the institutionalization of linguistic and social inequalities. Theoretically, the findings of this study show that the EMI classroom can turn into a translanguaging space where students and teachers engage in multiple meaning-making systems and potentially bring in different content knowledge from other content subjects in order to scaffold the learning and teaching of new content knowledge. Methodologically, this study highlights how adopting the translanguaging perspective can assist us to shift our attention from using different linguistic codes for promoting content learning to the way that teachers can create diverse multilingual, multimodal and multisensory sign-making practices for making learning accessible for all students in an EMI classroom. Adopting translanguaging as an analytical perspective emphasizes the need for researchers to pay attention to the details of how the teachers interact with the environment and how they orchestrate different multilingual resources, orient and adapt their bodies in relation to the students and artefacts in the classroom in order to understand cross-curricular connection as a dynamical process of deepening students’ content learning (Tai and Li Citation2021b, Citation2021c; Tai Citation2022a, Citation2022b, Tai and Wong Citation2022; Tai Citation2023; Tai and Li CitationForthcoming; Tai CitationForthcoming). Regarding pedagogical implications, teachers in culturally and linguistically diverse classrooms will benefit from the findings of this study due to the potential of translanguaging space in embracing diverse linguistic and multimodal repertoire for meaning-making, transcending subject-related barriers in students’ minds, and maximizing students’ ability to make connections between academic knowledge that are gained from other subject lessons. The findings draw attention to the significance of raising EMI teachers’ awareness of the pedagogical philosophies of constructing a translanguaging space for expanding students’ multilingual and multimodal repertoire and creating a learning experience which is relevant and meaningful to students.

Acknowledgement

First and foremost, I would like to thank the EMI history teacher and students who participated in this study. Thanks must also be given to Professor Rita Elaine Silver, Editor of Language and Education, and anonymous reviewers who took time to give feedback on our work. I would like to thank Mr. Ivan Liu and Ms. Katie Lor for offering me ideas and input for this paper. The work described in this paper was supported by the UK Economic and Social Research Council (Grant Reference: ES/P000592/1).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 In this study, I used pseudonyms to refer to all classroom participants and omit all potentially identifying details. The teacher is ‘Mr. Pang’; student 1 is Cherry; student 2 is Ken; student 5 is Andrew; student 6 is Will; student 7 is Kason; student 9 is John; student 10 is Taylor; student 12 is Jerry.

References

- Aizawa, I., and H. Rose. 2019. “An Analysis of Japan’s English as Medium of Instruction Initiatives within Higher Education: The Gap between Meso-Level Policy and Micro-Level Practice.” Higher Education 77 (6): 1125–1142. doi:10.1007/s10734-018-0323-5.

- Bonacina, F., and J. Gafaranga. 2011. “Medium of Instruction’ versus ‘Medium of Classroom Interaction’: Language Choice in a French Complementary School Classroom in Scotland.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 14 (3): 319–334. doi:10.1080/13670050.2010.502222.

- Brouwer, C. E., and J. Wagner. 2004. “Developmental Issues in Second Language Conversation.” Journal of Applied Linguistics 1 (1): 29–47. doi:10.1558/japl.1.1.29.55873.

- Cenoz, J., and D. Gorter. 2017. “Minority Languages and Sustainable Translanguaging: Threat or Opportunity?” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 38 (10): 901–912. doi:10.1080/01434632.2017.1284855.

- Chan, J. Y. H. 2013. “A Week in the Life of a ‘Finely Tuned’ Secondary School in Hong Kong.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 34 (5): 411–430. doi:10.1080/01434632.2013.770518.

- Chan, J. Y. H. 2014. “Fine-Tuning Language Policy in Hong Kong Education: Stakeholders’ Perceptions, Practices and Challenges.” Language and Education 28 (5): 459–476. doi:10.1080/09500782.2014.904872.

- Cooke, M., and C. Wallace. 2004. “Inside Out/outside: A Study of Reading in ESOL Classrooms.” In English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL): Case Studies of Provision, Learners’ Needs and Resources, edited by C. Roberts, M. Baynham, P. Shrubshall, D. Barton, P. Chopra, M. Cooke, R. Hodge, K. Pitt, P. Schellekens, C. Wallace, and S. Whitfield, 94–113. London: NRDC.

- Dearden, J. 2014. English as a Medium of Instruction: A Growing Global Phenomenon. London: British Council. https://www.britishcouncil.es/sites/default/files/british_council_english_as_a_medium_of_instruction.pdf

- Education Bureau. 2009. Fine-Tuning the Medium of Instruction for Secondary Schools (Education Bureau Circular No. 6/2009). Hong Kong: Government Printer.

- García, O., and W. Li. 2014. Translanguaging: Language, Bilingualism and Education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- García, O., N. Flores, K. Seltzer, W. Li, R. Otheguy, and J. Rosa. 2021. “Rejecting Abyssal Thinking in the Language and Education of Racialized Bilinguals: A Manifesto.” Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 18 (3): 203–228. doi:10.1080/15427587.2021.1935957.

- García, O., S. I. Johnson, and K. Seltzer. 2017. The Translanguaging Classroom: Leveraging Student Bilingualism for Learning. Philadelphia, PA: Caslon.

- Gardner, H., and V. B. Mansilla. 1994. “Teaching for Understanding in the Disciplines and beyond.” Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education 96 (2): 198–218. doi:10.1177/016146819409600212.

- Gierlinger, E. 2015. “‘You Can Speak German, Sir’: On the Complexity of Teachers’ L1 Use in CLIL.” Language and Education 29 (4): 347–368. doi:10.1080/09500782.2015.1023733.

- Haynes, C. 2002. Innovations in Interdisciplinary Teaching. Westport, CT: Oryx Press.

- Hutchby, I., and R. Wooffitt. 1998. Conversation Analysis: Principles, Practices and Applications. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Jacobs, H. H. 1989. “The Growing Need for Interdisciplinary Curriculum Content.” In Interdisciplinary Curriculum: Design and Implementation, edited by H. H. Jacobs, 1–11. USA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

- Jakonen, T., T. P. Szabó, and P. Laihonen. 2018. “Translanguaging in everyday practice.” In Translanguaging as Playful Subversion of a Monolingual Norm in the Classroom, edited by G. Mazzaferro. Springer.

- Jefferson, G. 2004. “Glossary of Transcript Symbols with an Introduction.” In Conversation Analysis: Studies from the First Generation, edited by G. Lerner, 14–31. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

- Koshik, I. 2002. “Designedly Incomplete Utterances: A Pedagogical Practice for Eliciting Knowledge Displays in Error Correction Sequences.” Research on Language & Social Interaction 35 (3): 277–309. doi:10.1207/S15327973RLSI3503_2.

- Larkin, M., V. Eatough, and M. Osborn. 2011. “Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis and Embodied, Active, Situated Cognition.” Theory & Psychology 21 (3): 318–337. doi:10.1177/0959354310377544.

- Li, W. 2011. “Moment Analysis and Translanguaging Space: Discursive Construction of Identities by Multilingual Chinese Youth in Britain.” Journal of Pragmatics 43: 1222–1235.

- Li, W. 2018. “Translanguaging as a Practical Theory of Language.” Applied Linguistics 39: 9–30.

- Li, W. 2021. “Translanguaging as a Political Stance: Implications for English Language Education.” ELT Journal 76 (2): 172–182.

- Li, W., and H. Zhu. 2013. “Translanguaging Identities: Creating Transnational Space through Flexible Multilingual Practices Amongst Chinese University Students in the UK.” Applied Linguistics 34 (5): 516–535. doi:10.1093/applin/amt022.

- Lin, A. M. Y. 2006. “Beyond Linguistic Purism in Language-in-Education Policy and Practice: Exploring Bilingual Pedagogies in a Hong Kong Science Classroom.” Language and Education 20 (4): 287–305. doi:10.2167/le643.0.

- Lo, Y. Y. 2015. “How Much L1 is Too Much? – Teachers’ Language Use in Response to Students’ Abilities and Classroom Interaction in CLIL.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 18 (3): 270–288. doi:10.1080/13670050.2014.988112.

- Lo, Y. Y., and A. M. Y. Lin. 2019. “Curriculum Genres and Task Structure as Frameworks to Analyse Teachers’ Use of L1 in CBI Classrooms.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22 (1): 78–90. doi:10.1080/13670050.2018.1509940.

- Macaro, E. 2018. English Medium Instruction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Macaro, E. 2020. “Exploring the Role of Language in English Medium Instruction.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23 (3): 263–276. doi:10.1080/13670050.2019.1620678.

- Macaro, E., S. Curle, J. Pun, J. An, and J. Dearden. 2018. “A Systematic Review of English Medium Instruction in Higher Education.” Language Teaching 51 (1): 36–76. doi:10.1017/S0261444817000350.

- Mondada, L. 2018. “Multiple Temporalities of Language and Body in Interaction: Challenges for Transcribing Multimodality.” Research on Language and Social Interaction 51 (1): 85–106. doi:10.1080/08351813.2018.1413878.

- Poon, A. Y. K. 2010. “Language Use, Language Policy and Planning in Hong Kong.” Current Issues in Language Planning 11 (1): 1–66. doi:10.1080/14664201003682327.

- Poon, A. Y. K., C. M. Y. Lau, and D. H. W. Chu. 2013. “Impact of the Fine-Tuning Medium-of-Instruction Policy on Learning: Some Preliminary Findings.” Literacy Information and Computer Education Journal 4 (1): 1037–1045. doi:10.20533/licej.2040.2589.2013.0138.

- Smith, J. A., P. Flowers, and M. Larkin. 2013. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method, and Research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Tai, K. W. H. 2022a. “Translanguaging as Inclusive Pedagogical Practices in English Medium Instruction Science and Mathematics Classrooms for Linguistically and Culturally Diverse Students.” Research in Science Education 52 (3): 975–1012. doi:10.1007/s11165-021-10018-6.

- Tai, K. W. H. 2022b. “A Translanguaging Perspective on Teacher Contingency in Hong Kong English Medium Instruction History Classrooms.” Applied Linguistics. Epub ahead of Print.

- Tai, K. W. H. 2023. “Managing Classroom Misbehaviours in the Hong Kong English Medium Instruction Secondary Classrooms: A Translanguaging Perspective.” System 113: 102959–102935. doi:10.1016/j.system.2022.102959.

- Tai, K. W. H., and A. Brandt. 2018. “Creating an Imaginary Context: Teacher’s Use of Embodied Enactments in Addressing a Learner’s Initiatives in a Beginner-Level Adult ESOL Classroom.” Classroom Discourse 9 (3): 244–266. doi:10.1080/19463014.2018.1496345.

- Tai, K. W. H., and C. Y. Wong. 2022. “Empowering Students through the Construction of a Translanguaging Space in an English as a First Language Classroom.” Applied Linguistics. Epub ahead of Print.

- Tai, K. W. H., and W. Li. 2020. “Bringing the Outside in: Connecting Students’ out-of-School Knowledge and Experience through Translanguaging in Hong Kong English Medium Instruction Mathematics Classes.” System 95: 102364–102332. doi:10.1016/j.system.2020.102364.

- Tai, K. W. H., and W. Li. 2021a. “Constructing Playful Talk through Translanguaging in the English Medium Instruction Mathematics Classrooms.” Applied Linguistics 42 (4): 607–640. doi:10.1093/applin/amaa043.

- Tai, K. W. H., and W. Li. 2021b. “Co-Learning in Hong Kong English Medium Instruction Mathematics Secondary Classrooms: A Translanguaging Perspective.” Language and Education 35 (3): 241–267. doi:10.1080/09500782.2020.1837860.

- Tai, K. W. H., and W. Li. 2021c. “The Affordances of iPad for Constructing a Technology-Mediated Space in Hong Kong English Medium Instruction Secondary Classrooms: A Translanguaging View.” Language Teaching Research: 136216882110278. Epub ahead of Print. doi:10.1177/13621688211027851.

- Tai, K. W. H., and W. Li. Forthcoming. “Embodied Enactment of Hypothetical Scenario in English Medium Instruction Secondary Mathematics Classrooms: A Translanguaging Approach.” Language Teaching Research. Epub ahead of Print.

- Tai, K. W. H., Forthcoming, June 2023. Combining Multimodal Conversation Analysis and Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: A Methodological Framework for Researching Translanguaging in Multilingual Classrooms. London: Routledge.

- ten Have, P. 1990. “Methodological Issues in Conversation Analysis.” Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique 27 (1): 23–51. doi:10.1177/075910639002700102.

- Ustunel, E., and P. Seedhouse. 2005. “Why That, in That Language, Right Now? Code-Switching and Pedagogical Focus.” International Journal of Applied Linguistics 15 (3): 302–325. doi:10.1111/j.1473-4192.2005.00093.x.

- Vella, Y. 2015. “How Do Students Learn History? The Problem with Teaching History as Part of an Integrated or Interdisciplinary Cross Curricular Pedagogical Approach.” International Journal of Historical Learning Teaching and Research 13 (1): 60–68.

- Waring, H. Z., and D. Yu. 2018. “Life Outside the Classroom as a Resource for Language Learning.” The Language Learning Journal 46 (5): 660–671. doi:10.1080/09571736.2016.1172332.

- Williams, C. 1994. “An evaluation of Teaching and Learning Methods in the Context of Bilingual Secondary Education.” PhD thesis, University of Wales, Bangor.

- Zhu, H., W. Li, and D. Jankowicz-Pytel. 2020. “Translanguaging and Embodied Teaching and Learning: Lessons from a Multilingual Karate Club in London.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23 (1): 65–80. doi:10.1080/13670050.2019.1599811.