Abstract

In a digital society, adolescents’ lives are heavily influenced by various multimodal texts published on social media platforms. Digital texts challenge conventional forms of literacy teaching while requiring new forms of critical media literacy. Previous research has shown that teachers require professional development and support to include critical media literacy in the classroom. In this article, we report the findings from a study of two lower secondary school teachers and their students (n = 43; ages 13–14) in Norway. The study explored a framework for increasing students’ understanding of multimodal texts and meaning making on social media. Drawing on theories of social semiotics, multimodality, and critical literacy, the study explored how students developed meta-semiotic competence to scaffold their ability to critically deconstruct, challenge, and produce multimodal, digital texts. The study indicates that multimodal analysis and production of self-representations can be an effective framework for developing critical media literacy in the classroom. The study demonstrates that students can compose intricate texts that are distinct from social media images when supported to understand the meanings behind the symbols they employ. It highlights specific kinds of semiotic understandings that must be introduced to students to enable them to approach social media texts analytically and critically.

1. Introduction

Society is becoming increasingly digital and multimodal given the accessibility, rapid production, and circulation of texts by everyday users, particularly on social media. Adolescents are the most frequent users of social media, dedicating significant time to creating, sharing, and viewing images on these platforms (Bell Citation2019; Paxton et al. Citation2022). Both teachers and students need to learn how digital communication technologies influence the nature of literacy practices (Snow and Moje Citation2010; Vasquez et al. Citation2013; Mills Citation2016; Nagle Citation2018). Digital technology calls for knowledge of expanded multimodal grammars as well as critical pedagogy (Cope & Kalantzis, Citation2009; The New London Group, Citation2000; Van Leeuwen Citation2017).

The focus of this study was critical media literacy, specifically concerning how individuals construct self-representations through visual and verbal means in online contexts, such as social media. Self-representation concerns how individuals communicate information about themselves to others (Baumeister Citation1982). Users can create and share images on social media to represent themselves (Bell Citation2019). Young people view self-representations by celebrities and influencers on social media. They post images of themselves through digital networks connected to their offline social lives (Scholes et al. Citation2022). Social media feeds now display images of both celebrities and influencers alongside regular adolescents and their friends. Albers et al. (Citation2018, p. 223) argued that images play a significant role in the digital world and should be subject to critical discussion.

In this research study, we explored how students could be guided in their interpretations of others’ depictions of themselves and in their critical construction of their personal online social identities (Cummins and Early Citation2011, Vasquez et al. Citation2019, p. 306) by connecting critical literacy practices in school to multimodal texts that are important in many students’ lives. The presented research included lower secondary Norwegian school teachers and their adolescent students (ages 13–14). The objective was to provide students with a deeper understanding of how multimodal texts work and might influence them and other people in social media spaces.

2. Critical media literacy

Digital technologies and media have changed the lives of children and youth with consequences for their communication and learning. In the 21st century, language teachers need to prepare students for literacy demands related to information shared in digital media and popular culture. Critical media literacy is a progressive educational response that expands the notion of literacy to include different forms of mass communication, popular culture, and new technologies and could refer to critical analysis of the relationships between media and audiences, information, and power, as well as students’ alternative media production (Garcia et al. Citation2013, p. 111).

The wide variety of texts, issues, and topics that capture learners’ interests online is found to be relevant for critical analysis, as social media spaces are never neutral (Nagle Citation2018, p. 91), and children internalise cultural norms (Albers et al. Citation2018, p. 225). Nevertheless, previous research has shown that few teacher education programs are preparing new teachers for critical evaluation of various media and information sources (Foley Citation2017; Share and Mamikonyan Citation2020). A study of how English teachers in the United States apply critical media literacy to their teaching practice indicates that implementing critical approaches in the classroom is challenging, even for teachers who attended courses in critical media literacy. In an online survey including both elementary- and secondary-level teachers (n = 185), most of the respondents reported that they included various media in their lessons, but far fewer teachers reported that they had analysed media critically to address questions of power and ideology (Share and Mamikonyan Citation2020). Recent studies have explored how students could uncover the critical potential of various kinds of media texts, such as short films (Mantei and Kervin Citation2016), advertisements (Brown Citation2022), and pop music videos (Kelly and Currie Citation2021). In an action research-based study, Elmore and Coleman (Citation2019) explored eighth-grade students’ rhetoric analysis of political memes and found that such tasks could support students’ critical media literacy skills. Students were able to perceive ‘them versus us’ arguments, how the memes evoked pathos, and how visual elements were arranged strategically in the memes. Most of these empirical classroom studies conclude that media texts could provide an entry point for the introduction of critical media skills. However, teachers need to expand their understanding of what constitutes text, as well as how to scaffold critical approaches in the classroom.

Social media literacy differs in specific ways from other forms of media literacy. When media literacy is defined as the ability to access, analyse, and produce information (Cho et al. Citation2022, p. 2), to critically appraise and evaluate media content, and to consume and use media accordingly (Paxton et al. Citation2022, p. 159), social media literacy is seen as an extended concept with a different social function. Social media texts are particularly powerful due to their highly visual nature, the personalised user-targeted and commercial content, and the invitation for users to create their own content and receive feedback (Paxton et al. Citation2022, p. 159). The technological and semiotic affordances of information shared on social media also challenge conventional forms of literacy teaching. Previous research has shown that many teachers currently have little experience with analysing visual representations and struggle to uncover underlying discourses and ideologies in visual and commercial texts (Harste and Albers Citation2012; Albers et al. Citation2018).

Cho et al. (Citation2022) suggested a conceptual framework for social media literacy that has implications for research as well as education. Within this framework, several aspects are mentioned, such as knowledge about the self and its relationship with social media content, understanding of the medium and its technological affordances, and awareness of the multiple realities and content generated through social media (Cho et al. Citation2022). Social media literacy is still a growing field of empirical investigation (Paxton et al. Citation2022, p. 159). In this study, we explored how students could build social media literacy through critical production, and the deconstruction of multimodal self-representations.

3. Critical production of multimodal texts

Research by the New London Group argues that students should become active and critical designers of meaning (Cope and Kalantzis Citation2009, p. 175). The value of teaching students to produce powerful digital multimodal texts in the language classroom is well documented (Mills Citation2015; Mills and Unsworth Citation2018; Veum et al. Citation2020). Giving students the opportunity to produce texts that matter to them affords a sense of interest, agency, and control over meaning making. Former research has shown that teachers play a necessary role in guiding students in the digital multimodal composing process (Lim and Nguyen Citation2022. p. 4).

The process of designing multimodal texts can be taught in a way that demonstrates the importance of critical awareness because multimodal text production is connected to language, identity, and power (Van Leeuwen Citation2017, p. 10; Vasquez et al. Citation2019, p. 302). By allowing students to choose formats and semiotic resources, they can gain a better understanding of how texts are constructed and how text producers position themselves and their readers or viewers (Janks Citation2010, p. 156). Critical media production involves students creating alternative media texts that challenge dominant narratives in their social worlds while learning the semiotic codes of multimodal representation. By creating alternative texts, students might examine popular culture and the media industry and question hierarchies and structures of power that influence their production (Stewart et al. Citation2021, p. 109).

The context of the present study was Norwegian lower secondary schooling. Norway was among the first countries in the world where digital competence was referred to as a core element in a national curriculum, and approaches to multimodal texts are also included in the curriculum (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2020a; Erstad and Silseth Citation2022, p. 31). However, existing Scandinavian research has demonstrated a need for developing educational conceptual tools to give teachers and students access to the semiotic repertoires to communicate meaning across an array of multimodal digital text formats and genres (Elf et al. Citation2018).

4. Research questions

Our study is guided by the following two research questions:

RQ1: How can teachers scaffold and evaluate students’ social media self-representations?

RQ2: How can students use, describe, and reflect on semiotic resources in their self-representations?

5. The study

The current study presents findings from a two-phased project on critical media literacy in lower secondary school in Norway. The project followed a design-based research approach (Plomp Citation2006), aiming to develop research-based solutions to complex problems and improve students’ learning processes. In the first phase of the project, six teachers from three lower secondary schools and four researchers participated in a 1-day workshop, co-designing lesson plans. In the second phase, the co-designed lessons plans were implemented in Norwegian Language classrooms by the participating teachers. Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data. Parental consent was obtained for the students, and the parents received an information letter. Consent was also obtained from the participating teachers.

5.1. Site and participants

The data were collected in the second phase of the project, which was based on the co-designed lesson plans and teaching practices that two teachers implemented in two classes with 43 students (13–14 years old). The teachers and students were recruited through an existing collaboration between university teacher education institutions and public secondary schools. The teachers were selected for their special interest in developing critical media literacy. Since 2020, critical thinking and critical literacy have been emphasised as particularly important issues in the Norwegian National Curriculum for primary and secondary education (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2020b).

5.2. Teacher workshop

Prior to the workshop, the teachers received pre-training material, such as video introductions, a list of conceptual tools for multimodal analysis of images, and current examples of self-representations of public figures in social media that were familiar to teens. Concepts from the multimodal framework were provided in Norwegian, based on already existing translations (see, e.g. Maagerø and Tønnessen Citation2014). The teachers participated in a 1-day workshop, where teachers and researchers worked closely together. Due to covid restrictions, the workshop was carried out as a webinar on Zoom. First, the researchers held a PowerPoint presentation online, modelling multimodal analysis of self-representations from social media. Second, teachers worked in pairs in breakout rooms, analysing texts by using available resources from the pretraining material. The available concepts are well established within social semiotics and multimodal analysis (Van Leeuwen & Jewitt, Citation2001; Machin and Mayr Citation2012; Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2021), including salience and colour (compositional meaning), action and vector (representational meaning), and size of frame, angle, and gaze (interactional meaning). Teachers were also requested to design lesson plans spanning four sessions (4 × 45 minutes). Finally, the teachers shared their multimodal analysis and lesson plans in a common online session and received feedback from the researchers.

5.3. Lesson implementation

The co-designed lesson plan involved two stages. First, critical analysis of social media texts was introduced and modelled by the teachers. Second, each student produced two texts: (a) a self-representational image and (b) a text analysis task containing a schematic descriptive analysis of the semiotic choices made and the student’s written reflections on the effects of these semiotic choices (see ). The lesson plan included several concepts from social semiotics, following Kress and van Leeuwen (Citation2021), supported by critical media literacy theory (Freebody and Luke Citation2003; Janks Citation2010; Janks et al. Citation2013). The students used concepts to analyse model texts from social media, applied these to their own multimodal designing of self-representations, and reflected on their use of these design principles.

Table 1. Template for students’ multimodal analysis.

5.4. Learning resources

The teachers designed three types of learning resources in collaboration with the researchers: (a) a task inviting students to create a self-representation, (b) a template for students’ multimodal analysis (see ), and (c) a list of key concepts for multimodal analysis. The task invited the students to create multimodal identity texts that could challenge dominant and stereotypical self-presentations in social media. Students could use various production technologies, digital or analogue. The restriction that students could not show their faces challenged them to think creatively about alternative ways of presenting their identity (Stewart et al. Citation2021; Cho et al. Citation2022). There were also ethical reasons for the restriction: Teachers and researchers wanted to ensure that the students could produce and share their texts without compromising their anonymity.

The aim of the second student learning task was to provide insight into the students’ ability to use the new terms and concepts to describe their own images and to reflect on the effects of the choices made in the image production process (Janks Citation2010). Therefore, the teachers designed a template for students’ multimodal analysis (see ). The analytic activity included two levels, inspired by the Barthesian concepts of denotation and connotation (Barthes Citation1997; Van Leeuwen Citation2005). At the first level, students responded to the denotative question, ‘What do you see in the image?’ The students described their application of semiotic principles in their images, such as gaze, size of frame, and salience. At the second level, the students interpreted the meaning of each chosen resource by responding to the question, ‘What does it mean?’ Here, the students were asked to explore the connotative meaning potential of the semiotic resources they used in their own images (see ). The task was not to be viewed as a complete text analysis comprising all possible elements of multimodal design. Rather, the task was designed to support the learners’ first multimodal analysis, providing useful and valuable information about the students’ abilities to understand connotative and denotative meanings.

Teachers explicitly taught and modelled a small sample of key concepts accessible to the early adolescent students. The students learned that salience in images refers to the perceived importance or emphasis of something in the visual composition. The salience of the visual objects in an image guides our eyes, determining our reading pattern, starting with the elements of the highest salience and moving down the scale (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2021, pp. 210–220). Regarding colour, students learned that especially saturation and contrast are variables that affect mood, perceived intensity, and salience (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2021, pp. 236–251).

Teachers explained how images could express action through narrative or conceptual structures or a combination of the two. Narrative structures typically contain a vector – a line in an image that functions as a visual process. The presence of a vector gives the image a narrative quality (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2021, pp. 55–75).

Students also learned about various ways of representing interactional meaning. Size of frame refers to the viewer’s perceived proximity to the subjects in an image. Students learned how close shots are zoomed in on a detail, medium shots show a little context, and long shots place the focal participant in a wider setting. The size of frame governs how one relates to the object in focus and its context (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2021, pp. 123–124).

Angle determines relations of power in an image. An object may be shown from the front, the side, behind, above (bird’s-eye view), or below (worm’s-eye view). Horizontal angle determines to what extent we feel as if we engage with the object or person. Vertical angle determines the extent to which a person or thing appears to be powerful. Objects viewed from below tend to be perceived as more powerful (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2021, pp. 133–140).

The students were taught how the type of gaze influences the feeling of involvement in an image. If the image directly addresses the observer, it functions as a demand. If the image simply displays something for the observer to see, it functions as an offer (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2021, pp. 115–121).

6. Data collection and analysis

Two categories of qualitative data sets were collected: teacher interviews and student-created texts with multimodal analysis. Each data set is matched with the research question they are used to address. provides an overview.

Table 2. Data matched to research questions.

6.1. Semi-Structured interview with teachers

A 25-minute semi-structured interview with two teachers from the same school was conducted shortly after the lesson implementation. The interview protocol included questions such as, ‘Could you describe the lesson plan that you used in your classroom that was based on the workshop?’, ‘In what way do you believe that your approach contributes, or does not contribute, to strengthening the students’ critical approach to text?’, and ‘What could you share with other teachers who will be working with self-representation and visual analysis in the classroom?’

The teacher interviews were transcribed and translated into English for analysis in NVivo 12. Thematic analysis was used to systematically identify, organise, and describe the themes and patterns in the teacher interviews about their application of critical literacy and multimodal semiotics in their text analysis work with the students (Guest et al. Citation2012). Inductive coding broadly separated the teachers’ recounting of the research task (the lesson plan activities and assignment) from teachers’ perceptions related to critical literacy pedagogy (Freebody and Luke Citation2003; Janks Citation2010; Janks et al. Citation2013). Deductive coding also involved grouping the teachers’ reflections on the concepts of denotation and connotation (Barthes Citation1997; Van Leeuwen Citation2005). provides example themes informing the analysis of teachers’ multimodal and critical literacy pedagogy.

Table 3. Themes informing the analysis of teachers’ multimodal and critical literacy pedagogy.

6.2. Student self-representations and schematic analysis

The student data informing the second research question aimed to understand the students’ application of multimodal and critical text analysis to their self-representations. Year 8 school students each created a self-representational image (n = 43) and then completed a schematic descriptive analysis of their semiotic choices. The students’ written responses were translated into English and thematically analysed by the researchers using NVivo 12 software. Deductive thematic coding was informed by Kress and van Leeuwen (Citation2021) visual design elements (e.g. theme, gaze, vectors, visual salience) to analyse the students’ application of multimodal and critical literacy concepts in their written reflections about their self-representational images. The codes applied to the students’ texts were not inductively derived because the students were provided with the multimodal categories to systematically scaffold the text analysis task. For each category, students could include a denotative and connotative response (see ).

Table 4. Multimodal semiotic themes applied to students’ critical self-representations.

7. Findings

The findings are presented in two sections that are matched to the research questions. In the first section, we present findings regarding how teachers can scaffold and evaluate students’ social media self-representations (RQ1). In the second section, we present findings of how students used, described, and reflected on semiotic resources in their self-representations (RQ2).

7.1. Scaffolding and evaluating students’ social media self-representations

The first stage of the scaffolding was to introduce texts from social media and explain to students how these texts are relevant to classroom activities. Analysis of the interviews identified that the teachers, Johanna and Linda (pseudonyms), were initially unfamiliar with the use of social media texts in the classroom, but the workshop inspired them to discuss examples of social media self-representations in class. One teacher analysed Instagram images of male and female soldiers in the Norwegian Armed Forces. The other considered Norwegian pop stars’ construction of identity on Instagram. After the lesson implementation, the teachers saw the importance of including analysis of real-life, recognisable content such as ‘informal’ images or popular social media texts in the classroom: Johanna explained, ‘After all, we’re used to talking about complex texts in Norwegian class, but examining social media instead, like we did here, is a good idea in my opinion…. I think it’s incredibly important to dare teach about this at school and to analyse it.’ Linda concluded that social media texts engaged her students: ‘Doing an analysis with pictures they recognise from their own world. I think it was a huge success.’

7.1.1. Modelling multimodal Text analysis

The teachers found it difficult to explain to their students the concept that reality can be constructed through visuals and that images are not neutral (Albers et al. Citation2018, p. 223; Janks et al. Citation2013, p. 63). Some students were sceptical that social media influencers critically consider the construction of their social media identities using the kinds of techniques taught in class and were initially overwhelmed by the approach to multimodal analysis. Multimodal concepts were, therefore, introduced step by step, and text analysis was modelled explicitly in class. Linda found this modelling to be crucial: ‘I think the students need to see that we are doing the analysis together, and they need us to demonstrate how new technical terms are used.’

The teachers started by focusing on the students’ awareness of how the construction of visual communication is motivated. Several familiar texts from the students’ digital lives were shown in class, and the teachers let their students first make their own textual observations. Johanna explained how she introduced her lesson using two popular Instagram profiles, interpreting the authors’ intended meanings in the words and images.

Based on instructions in the workshop, the teachers then modelled the multimodal analysis on two levels, description (denotation) and interpretation (connotation) (Barthes Citation1997). The teachers determined that simplification of the concepts was necessary. Johanna concluded: ‘After all, the most important thing is not for the students to be able to use those specific terms but that they understand the advantage of talking about what you see before interpreting it, or before you start trying to figure out what it means’.

7.1.2. Scaffolding critical approaches to social media

The most engaging part of the lesson was, according to these teachers, when students took part in critical literacy discussions in class. The teachers found that conceptual tools from social semiotics were helpful but had to be followed by strategic questions to guide the students in the critical analysis. By being introduced to examples of texts posted by influencers and celebrities that the students know from social media, the students also became aware of commercial interests of social media texts producers. Linda explained, ‘I think the introductory lesson made them a lot more aware. We also talked about how the products that Vegard Harm uses are placed in the picture. It may have been that context perhaps, the influence of advertising, that actually made them observant, and they began to talk a lot about it using other examples.’ Both teachers believed that the lesson plan they designed in cooperation with the researchers could prepare the students for critical engagement on social media platforms. Linda emphasised, ‘After all, a lot of social media has an age limit of 13, but most young people have an account in these channels before they turn 13, unfortunately. So, we need to keep up with reality and make them aware of this. So that they’ll be prepared when they open an account or if they already have one.’ Both teachers concluded that they had mostly positive experiences with including social media texts in their teaching. However, they emphasised that students and classes differ, and lesson plans as well as forms of scaffolding must be flexible.

7.2. Semiotic resources in students’ self-representations

The images produced by the students were materially different. Some of the students made drawings or painted, and many took photographs. Several also used images they found online, both photographic and non-photographic. Many students also used a combination of several types of material. Despite using different production technologies (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2021), the students all handed in their images digitally. The data set therefore consists of digital images, but some of them involved drawing, painting, or photography in the production phase. The student texts were coded according to how they represented the following themes: participants (characters or objects), gaze, size of frame, angle, highlight/salience, and vector. All of these themes were represented in the student texts that make up the present material. We found that there was great variation when it came to how many of the themes were represented in each text and to what extent and how thoroughly the students commented on each of them in their own analyses. In the following, we shall comment on the use of these themes in three example texts, and these are examples of best practice in these classrooms. The reason we focus on three examples that were regarded as good by the teachers and researchers is that they together provide examples of all the themes and usages we observed in the material as a whole and, thus, can serve to shed light on what can be achieved by working with a classroom task such as this.

7.2.1. Student texts

The task invited the students to extend their range of semiotic resources (Janks Citation2010, p. 156). Although our systematic analysis and NVivo coding spanned all 43 student self-representations, we will in this article refer to a sample of three students’ texts that are representative of the themes that the students’ addressed in their scaffolded multimodal analysis. The three texts also represent the varied media selected by the students – drawings, collages, and photographs – and are illustrative of the range of semiotic resources applied by the students.

7.2.1.1. Text 1: A bubble of icons

This image () shows a person with long, blonde hair blowing a pink bubble. Inside the bubble are eight different icons resembling a horseshoe, a leaf, a palette and paintbrush, a necklace, a family, a heart, a mandala, and some musical notes. The icons are drawn in grey pencil, while the rest of the image seems to be composed using colour pencils and watercolour.

7.2.1.2. Text 2: Emojis, logos, and clip art

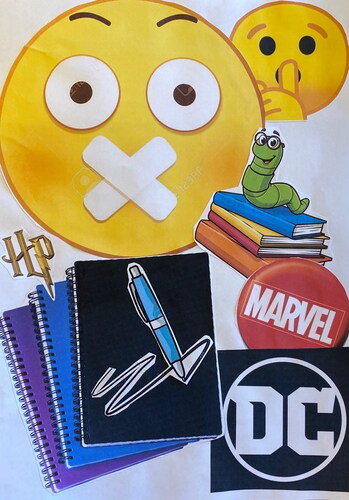

This image () is a collage of digital elements that have been printed and cut out, assembled physically, and then photographed. There are two emojis: One is a face with the mouth taped shut by two pieces of tape that form a cross, and the other is a face that makes a ‘hush’ gesture with an index finger over the mouth. There are three recognisable logos: the logos of the franchises DC comics, Marvel, and Harry Potter. Although DC and Marvel were originally comic book publishers and Harry Potter was originally a character in the book series by J. K. Rowling, all three logos also represent successful franchises connected to blockbuster movies. The image also contains other visual elements: There is a stack of books and a pen, and another stack of books with a ‘bookworm’ – a worm wearing glasses – on top.

Figure 2. Student text 2.

7.2.1.3. Text 3: A jumping person

This photograph (), of a person jumping, is taken slightly from below and against the light so that the person becomes a silhouette. The entire body is visible and looks to be caught mid-leap, swaying the back, and reaching behind with both arms and legs, toes pointed as in a ballet pose. The background is a blue sky with white clouds.

7.2.2. Salience

In the students’ texts, we see variations in what they chose to make salient: It is not always a representation of their physical self but often something that symbolises them in some way. Salience is determined by several variables, such as size, placement, and colour.

In Texts 1 and 2, there are several objects depicted, and salience is determined by the size and placement of each element. In Text 3, only one object is depicted – the jumping body – made salient due to centralised position and contrast. In Texts 1 and 2, both size and placement determine salience, making the bubble most salient in Text 1 and the largest emoji placed top left the most salient feature in Text 2.

In their response to the text analysis task, the students show awareness of how salience is created in the images and of the meaning potential of the most salient element. For Text 1, the student said, ‘The bubble is the focus’, and for Text 2, ‘One of the emojis is huge; the largest item in the picture and it’s at the top…. Light and dark colours emphasize the elements.’ In Text 3, the student described the following: ‘The person is very emphasized because the background is bright and neutral, and the person is dark. The person also takes up a lot of space in the image and is centred in the image.’

Some of the students also showed awareness of the connotative level of salience. For example, Student 1 said that ‘the bubble gum bubble is a sign that means nothing lasts forever (the things inside the bubble can change).’ In other words, the student noted that the things in life that one values are in a state of flux and can change over time, like a bubble that serves as a metaphor for temporality.

7.2.3. Size of frame

The students used size of frame in their images to focus on items or activities, to give salience to various features, and to establish context. Texts 1 and 3 appear as opposites: The first is a close-up, and the latter a long shot. In Text 1, the viewer appears to be close to the bubble and the head but a little distance away from each icon contained within the bubble. This creates an interesting effect where we are simultaneously close to the person’s values and looking at them from a distance. In Text 3, the movement of the body is as if it is suspended in mid-air but seen from a distance. The student emphasised in their response that the image shows ‘physical activity (something which I love).’ Student 1 said that the close-up can ‘maybe feel like one gets a little closer to the person and start to think about what they’re thinking of.’

In Text 2, we see all the elements in full perspective, so there is no perceived closeness to them, yet the student discerned in their written analysis that the shot is a close-up. This may be because the most salient feature in the image is an emoji, which could be described as a close-up of a face. The student elaborated, ‘The [size of frame] gives a clear overview of my interests and hobbies and tells something about me in a discreet way.’ This quote shows awareness of the effects of size of frame.

7.2.4. Angle

The students used angles in their texts to determine power relations and mood. Both Texts 1 and 2 show a neutral angle. A neutral angle puts the viewer on an equal level with the person or object depicted. The image in Text 3 is taken from a slightly low angle, giving the impression that the depicted person is free and powerful.

In Text 1, the student says the angle creates closeness and identification between the viewer and the objects. Both Texts 1 and 2 are photographs taken of a physical image that is lying on a worktop, so in one sense, both images also employ the bird’s-eye angle, and the effect of this may be a centring of the techniques used (drawing/painting in Text 1 and collage in Text 2). It can also function as an over-the-shoulder angle (Unsworth Citation2013), as we see the finished image from the creator’s point of view as they take the picture.

7.2.5. Colour

The students mainly used colour as naturalistic representations of the world, but also to influence mood. Text 1 uses pastel hues, and the main colour is the soft pink of the bubble. The use of pastel colours creates associations with the soft, the quiet, and the unintrusive. Text 2 uses saturated hues that create a less naturalistic representation. This use of colour could be seen as contrasting what the student says about ‘telling a little about myself in a discreet way’ but may also be the student’s way of representing themselves in very generic terms. The student wrote, ‘The emojis show that I can keep secrets, but also that I don’t like to disclose too much about myself unless I really trust the person.’

Text 3 uses bright light in the background to reduce the colour in the image, creating contrast, because the subject almost becomes a silhouette. The background is a naturalistically represented sky, and the student lists this as something that is important to her: ‘a beautiful sky (something I love taking photos of).’ Many of the students recognise their own use of contrast, and most interpret it as a way of creating salience.

7.2.6. Gaze

In many of the students’ images, the represented participants do not address the viewer directly, such as in Text 1, where the person has closed eyes, and in Text 3, where the person’s face is obscured by shadow. In Text 1, the student writes that the closed eyes may indicate that the person ‘is relaxed or thinking (thinking about what is in the bubble).’ In Text 3, the student wrote that the gaze is directed at the camera, but that this is obscured by shadow, and said that ‘the head is directed towards the camera, so this might mean that the person wants the viewer to look them in the eyes, but at the same time not, you can’t see them properly.’

In Text 2, there are three instances of direct gaze from the two emojis and the bookworm depicted. These directly address the viewer and demand interaction. Student 2 commented on the direct gaze and said this shows awareness that they are being looked at.

7.2.7. Action (vector)

The data set contains both conceptual and narrative structures. In Text 1, the action depicted is blowing a bubble. The image is conceptual, communicating the important values of the student. They commented that ‘the eyes are closed, but the head is tilted upwards,’ which shows awareness of the fact that gaze can also create vectors. Text 2 can best be described as a conceptual image, with no overarching narrative. The student pointed out the local vectors created by the hushing finger across the mouth of one of the emojis and the bookworm’s climb onto the stack of books. Text 3 has a clear narrative structure, as the person’s body creates a vector, which gives the impression of movement. Movement is greatly emphasised in the student’s text analysis, which calls the action ‘jumping’, ‘being active’, ‘moving’, and ‘dancing’.

8. Discussion

In this study, we have explored how teachers could implement critical media literacy in the classroom to deepen students’ understanding of the power of multimodal texts shared in social media. We were guided by the research questions on how teachers can scaffold and evaluate students’ social media self-representations (RQ1) and how students can use, describe, and reflect on semiotic resources in their self-representations (RQ2). In response to the first question, we found that a high level of scaffolding is needed when students approach social media texts analytically and critically. By using strategic questions regarding the explicit and implicit agenda behind the text (Mills Citation2015, pp. 178–179), the teachers activated students’ prior experiences with social media texts and integrated new knowledge of critical media literacy and multimodal analysis. This form of scaffolding supported students’ literacy engagement (Cummins and Early Citation2011, pp. 35–36). The teachers experienced that their students mostly engaged in class discussions of visual communication in Instagram texts.

However, some students doubted the strategic and motivated nature of semiotic choices in visual communication. This finding underlines the importance of including social media texts in critical literacy work because such texts are powerful but still often regarded as natural and unimportant (Nagle Citation2018; Cho et al. Citation2022; Paxton et al. Citation2022). In this study, students were introduced to a framework of concepts from social semiotics, and they were encouraged to do multimodal analysis of self-representations in social media, as well as of their own texts. The teachers experienced that well-supported simplification of the concepts was crucial to success when using multimodal metalanguage to increase students’ critical awareness of meaning. By modifying the concepts, the teacher made the input more comprehensible to the students in the construction of their own identity texts (Cummins and Early Citation2011, p. 35).

In response to the second question, our findings suggests that students can create varied and complex texts that differ from social media images and that they are often aware of the meaning potential of the semiotic resources they use. The analysis of students’ own self-representations demonstrates that students were able to use a variety of semiotic resources in deliberate ways to design a multimodal representation of themselves (Bezemer and Kress Citation2010; Mills Citation2015). The students’ texts were communicative, relatable, and strategic in the sense that they used the visual tools afforded by the production materials to construct rich texts that are possible to interpret. The fact that the artefacts we examined were so varied indicates both creativity and multimodal literacy.

The student-created self-representations are different from those we are accustomed to seeing on social media. Self-representations in social media typically involve a selfie, a visual genre that evolved with the introduction of the smartphone (Rettberg Citation2014; Veum and Undrum Citation2018). Asking the students to distance themselves from this convention encouraged them to use varied media formats, employing production techniques other than photography, such as drawing/painting and collage.

The students chose to represent themselves through references to values, such as family and nature, and personality traits, such as being shy and being active, rather than just how they look or what they do. They focused on what Van Leeuwen calls individual identity, which typically involves a person’s uniqueness and inward qualities, rather than their socially constructed identity (Van Leeuwen, Citation2021, pp. 11–18). Guiding students to create representations that differ from those they have seen on social media can introduce alternative ways of constructing identity and make them aware of what effects different ways of constructing identity can have (Cummins and Early Citation2011; Cho et al. Citation2022). Our analyses show that students can achieve a certain level of understanding of their own strategies, something that may eventually lead to transformation and lasting change in how students understand texts and text production (Janks Citation2010). Our starting point for creating the students’ text analysis activity was Barthes (Citation1997) terms denotation and connotation. This separation of a sign’s surface meaning from its cultural and associated meanings proved fruitful, as it enabled students to delve deeper into their self-representations and look for meaning potential.

9. Conclusion

This study has addressed how students can build critical media literacy through analysis and production of self-representations. The findings have implications for both educational practice and research in critical media literacy. The study supports former research in emphasising how technological and semiotic affordances of social media information challenge the conventional forms of literacy teaching (Cho et al. Citation2022; Paxton et al. Citation2022). In our study, we found that the teachers were not familiar with implementing multimodal social media texts in their teaching and that their students doubted that visual communication is motivated. This finding corresponds with earlier findings that indicate a need for expanding teachers’ and students’ understandings of what constitutes text and how to deconstruct visual and multimodal texts in the classroom (Harste and Albers Citation2012; Mantei and Kervin Citation2016; Albers et al. Citation2018). Our study also underlines earlier findings that have documented that it is challenging for teachers to implement critical approaches to media texts in their teaching, especially when it comes to addressing questions of power and ideology (Share and Mamikonyan Citation2020).

We found that the cyclical process of analysing texts, creating one’s own texts, and then analysing one’s own creation (Janks Citation2010, p. 183) proved a productive framework. By analysing and creating self-representations, students had the opportunity to reflect on their semiotic choices as critical agents (Pandya and Ávila Citation2014, p. xxi; Mills Citation2015, p. 179). Previous research has demonstrated a need for development of semiotic conceptual tools in Scandinavian schools (Elf et al. Citation2018). Because our findings suggest that students can put analytic terms to good use in a relatively short time, this can inspire teachers to introduce more advanced metalanguage for critical multimodal analysis of media texts (Elf et al. Citation2018, p. 96).

In this study, we took up the challenge of previous research indicating that professional development is crucial to support teachers’ competencies to design for meaningful learning experiences using social media texts (Stewart et al. Citation2021; Lim and Nguyen Citation2022), providing an exemplar for supporting both teachers’ and students’ critical media literacy from a multimodal perspective. The study contributes to the growing literature on critical and social media literacy (Nagle Citation2018; Cho et al. Citation2022; Paxton et al. Citation2022) by providing a framework for developing adolescents’ awareness of how they and others represent themselves on social media. More research on applications of critical media literacy is needed. One key is to give students the multimodal analytical tools and critical awareness of various kinds of media texts to support the popular everyday literacy practices of adolescents in a digital age.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albers P, Vasquez VM, Harste JC. 2018. Critically reading image in digital spaces and digital times. In: Mills K, Stornaiuolo A, Smith A, Pandya JZ, editors. Handbook of writing, literacies and education in digital cultures. New York: Routledge. p. 223–234.

- Barthes R. 1997. The eiffel tower. In: Barthes R, editor. The eiffel tower: and other mythologies. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 3–17.

- Baumeister RF. 1982. A self-presentational view of social phenomena. Psychol Bull. 91(1):3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.91.1.3

- Bell BT. 2019. “You take fifty photos, delete forty nine and use one”: A qualitative study of adolescent image-sharing practices on social media. Int J Child-Comput Interact. 20(2019):64–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcci.2019.03.002

- Bezemer J, Kress G. 2010. Changing text: A social semiotic analysis of textbooks. Design Learn. 3(1-2):10–29. https://doi.org/10.16993/dfl.26

- Brown CW. 2022. Taking action through redesign: Norwegian EFL learners engaging in critical visual literacy practices. J Visual Literacy. 41(2):91–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/1051144X.2021.1994732

- Cho H, Cannon J, Lopez R, Li W. 2022. Social media literacy: A conceptual framework. New Media Soc,. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211068530

- Cope B, Kalantzis M. 2009. “Multiliteracies”: New literacies, new learning. Pedag An Inter J. 4(3):164–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/15544800903076044

- Cummins J, Early M. 2011. Identity texts: The collaborative creation of power in multilingual schools. London: Trentham Books Ltd.

- Elf NF, Gilje Ø, Olin-Scheller C, Slotte A. 2018. Nordisk status og forskningsperspektiver i L1: Multimodalitet i styredokumenter og klasseromsprakss. In: Rogne M, Waage LR, editors. Multimodalitet i skole og fritidstekstar. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget, LNU. p. 71–104.

- Elmore PG, Coleman JM. 2019. Middle School Students’ Analysis of Political Memes to Support Critical Media Literacy. J Adolescent & Adult Lit. 63(1):29–40. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/48555651. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.948

- Foley Y. 2017. Critical literacy. In: Street BV, May S, editors. Literacies and language education. 3rd ed. Cham: Springer. p. 109–120.

- Erstad O, Silseth K. 2022. Transformation and unresolved tension. Children, school and technology. In: Kumpulainen K, Kajamaa A, Erstad O, Mäkitalo Å, Drotner K, Jakobsdóttir S, editors. Nordic childhoods in the digital age. The Netherlands: Routledge. p. 30–40. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003145257.

- Freebody P, Luke A. 2003. Literacy as engaging with new forms of life: The ‘four roles’ model. In Bull G, Anstey M, editors. The literacy lexicon. Sydney: Prentice Hall. p. 52–65.

- Garcia A, Seglem R, Share J. 2013. Transforming teaching and learning through critical media literacy pedagogy. LL. 6(2):109–124. https://doi.org/10.36510/learnland.v6i2.608

- Guest G, MacQueen K, Namey E. 2012. Applied thematic analysis. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications.

- Harste JC, Albers P. 2012. “I’m Riskin’ It” Teachers take on consumerism. J Adolescent Adult Lit. 56(5):381–390. https://doi.org/10.1002/JAAL.149

- Janks H. 2010. Literacy and power. New York: Routledge.

- Janks H, Dixon K, Ferreira A, Granville S, Newfield D. 2013. Doing critical literacy: texts and activities for students and teachers. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203118627.

- Kelly DM, Currie DH. 2021. Beyond stereotype analysis in critical media literacy: case study of reading and writing gender in pop music videos. Gender and Education. 33(6):676–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2020.1831443

- Kress G, van Leeuwen T. 2021. Reading images: The grammar of visual design. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

- Lim FV, Nguyen TTH. 2022. ‘If you have the freedom, you don’t need to even think hard’ – considerations in designing for student agency through digital multimodal composing in the language classroom. Lang Educ. 37(4):409–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2022.2107875

- Maagerø E, Tønnessen ES. 2014. Multimodal tekstkompetanse [Multimodal textual competence]. Kristiansand: Portal forlag.

- Machin D, Mayr A. 2012. How to do critical discourse analysis: a multimodal introduction. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Ltd.

- Mantei J, Kervin L. 2016. Re-examining “Redesign” in critical literacy lessons with grade 6 students. ELR. 5(3):83–97. https://doi.org/10.5430/elr.v5n3p83

- Mills KA. 2015. Doing digital composition on the social web. In: Cope B, Kalantzis M, editors. A pedagogy of multiliteracies: learning by design. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 172–185.

- Mills KA. 2016. Literacy theories for the digital age. Social, critical, multimodal, spatial, material and sensory lenses. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Mills KA, Unsworth L. 2018. iPad animations: powerful multimodal practices for adolescent literacy and emotional language. J Adolescent & Adult Lit. 61(6):609–620. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.717

- Nagle J. 2018. Twitter, cyber-violence, and the need for a critical social media literacy in teacher education: A review of the literature. Teach Teacher Educ. 76:86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.08.014

- The New London Group. 2000. A pedagogy of multiliteracies designing social futures. In: Cope B, Kalantzis M, editors. Multiliteracies. literacy learning and the design of social futures. Cambridge: Routledge. p. 9–37.

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. 2020a. Curriculum in the subject Norwegian [Læreplan i norsk].https://www.udir.no/lk20/nor01-06.

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. 2020b. Core curriculum – values and principles for primary and secondary education. https://www.udir.no/lk20/overordnet-del/om-overordnet-del/?lang=eng.

- Pandya JZ, Ávila, J, editors. 2014. Moving critical literacies forward: A new look at praxis across contexts. New York: Routledge.

- Plomp T. 2006. Educational design research: An introduction. In: Plomp T, Nieveen N, editors. Educational design research. Enschede: Netherlands Institute for Curriculum Development (SLO). p. 11–50.

- Paxton, J., McLean, S.A., Rodgers, R.F. 2022. “My critical filter buffers your app filter”: social media literacy as a protective factor for body image. Body Image, 40:158–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.12.009

- Rettberg JW. 2014. Seeing ourselves through technology: How we use selfies, blogs and wearable devices to see and shape ourselves. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Scholes L, Mills KA, Wallace E. 2022. Boys’ gaming identities and opportunities for learning. Learn Media Technol. 47(2):163–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2021.1936017

- Share J, Mamikonyan T. 2020. Preparing English teachers with critical media literacy for the digital age. Contemp Issues Technol Teacher Educ. 20(1):37–54.

- Snow C, Moje E. 2010. Why is everyone talking about adolescent literacy? Phi Delta Kappan. 91(6):66–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171009100616

- Stewart OG, Scharber C, Share J, Crampton A. 2021. Critical media production. In: Pandya JZ, Mora RA, Alford J, Golden NA, de Roock RS, editors. The handbook of critical literacies. New York: Routledge. p. 105–115. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003023425.

- Stornaiuolo A, Hull G, Hall M. 2018. Cosmopolitan practices, networks, and flows of literacies. In: Mills KA, Stornaiuolo A, Smith A, Pandya JZ, editors. Handbook of writing, literacies, and education in digital cultures. New York: Routledge. p. 13–25. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315465258.

- Unsworth L. 2013. Point of view in picture books and animated movie adaptations. Scan. 32(1):28–37.

- Van Leeuwen T, Jewitt C. 2001. Handbook of visual analysis. London: SAGE.

- Van Leeuwen T. 2021. Multimodality and identity. London: Routledge.

- Van Leeuwen T. 2017. Multimodal literacy. Viden Om Literacy. 21:4–10. https://www.videnomlaesning.dk/tidsskrift/tidsskrift-nr-21-multimodale-tekster/

- Van Leeuwen T. 2005. Introducing social semiotics. London: Routledge.

- Vasquez VM, Janks H, Comber B. 2019. Critical literacy as a way of being and doing. Lang Arts. 96(5):300–311. https://doi.org/10.58680/la201930093

- Vasquez VM, Tate SL, Harste JC. 2013. Negotiating critical literacies with teachers. New York and London: Routledge.

- Veum A, Undrum LVM. 2018. The selfie as a global discourse. Discourse Soc. 29(1):86–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926517725979

- Veum A, Siljan HH, Maagerø E. 2020. Who am I? How newly arrived immigrant students construct themselves through multimodal texts. Scand J Educ Res. 65(6):1004–1019. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1788147