Abstract

Solo-living employees are a growing segment of the workforce, yet their work-life experiences are under-researched. Taking a biographical narrative approach, we interviewed 35 solo-livers from different countries to explore their transition to homeworking during the Covid-19 lockdowns. Drawing upon the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model and key concepts from the work-life interface literature, we explored both lost/reduced and new/increased job and personal demands and resources at this time. We found that the transition to homeworking during lockdown created several challenges for solo-living staff, often exacerbated by changes to the demands and resources of others – namely those with childcare responsibilities. We argue that ‘sense of entitlement to support for work-life balance’ is an important personal resource, which impacts the work-life interface, and which solo-living staff often lack. Our findings offer solo-friendly recommendations for organisational practice.

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic, and associated changes to employment, workloads and ways of working have had significant impacts on the work-life interface. Considerable academic, practitioner and media attention was paid to extended enforced homeworking during mandatory Government ‘stay at home’/lockdown orders in 2020 and beyond, often highlighting the challenges this posed to working parents, who had to accommodate additional childcare and home-schooling demands (i.e. Hjálmsdóttir & Bjarnadóttir, Citation2021; Nieuwenhuis & Yerkes, Citation2021; Dawes et al., Citation2021; Young, Citation2021). Less attention was given to the specific experiences of employees who live alone, despite being the fastest-growing demographic group in many developed countries (Jack et al., Citation2021; Eurostat, 2020; ONS, Citation2019; US Census, Citation2021).

The limited prior research suggests this group face unique job demands and work-life challenges, as well as experiencing many of the job demands and work-life challenges reported more broadly in the literature. Wilkinson et al. (Citation2017) reported that solo-living employees in the UK often worked long hours and were expected to travel at short notice. They felt that their non-work time demands (e.g. friendship building and maintenance, dating, domestic requirements) were not seen as legitimate reasons for requiring flexibility at work, or for refusing requests to work additional hours, unlike the demands of working parents. Similar perceptions of time availability were reported in other contexts (Akanji, et al. 2019; Casper & Swanberg, Citation2009). In the UK context, many solo-living employees were seen to share their employers’ ‘needs’ based distributive justice stance (that working parents need more support), informed by the legislative stance on work-family support, which historically prioritised parents. They therefore often volunteered for extra work/staying late and/or failed to perceive differential treatment that advantaged working parents as unfair; hence not complaining (to potentially improve their situation) or engaging in backlash behaviours (Wilkinson et al., Citation2018). Where unfairness or discrimination is perceived however, it can affect self-esteem and increase stress (Akanji et al., Citation2020; Casper & Swansberg, 2009). Wilkinson et al. (Citation2017) reported other work-life issues for solo-living staff, such as heightened vulnerability at work. They can be vulnerable financially, as the sole earner in the household, and vulnerable in terms of identity. In the absence of partner and parenting roles in the home domain, and the social support and interaction such roles provide, threats to work identity can be experienced as especially significant and negative.

These demands and challenges are likely exacerbated by the pandemic and enforced homeworking context. In many industries, additional work requirements (directly due to the pandemic and/or new ways of working), were combined with increased absence levels, necessitating work reallocation. Where additional headcount cannot be secured, solo-living employees might pick up a significant proportion of extra work, due to widespread awareness of the challenges faced by working parents at this time, and the prevalence of special family-friendly provisions (Coe et al., Citation2021; Nieuwenhuis & Yerkes, Citation2021; Kollewe, Citation2021). The perceived lack of legitimacy around their own work-life issues (Wilkinson et al., Citation2017) might make solo-livers feel reluctant to report their own struggles. There are also significant threats to job security and income, with widespread redundancies, furlough and salary reduction schemes (Nieuwenhuis & Yerkes, Citation2021; Powell & Francis-Devine, Citation2021; CIPD, Citation2020), which are worrying for solo-livers. With many non-work activities around community, leisure and friendship compromised by the stay-at-home order, it is possible that solo-living staff might attach greater importance to their job role, making them more vulnerable to disappointments in the work domain (Wilkinson et al., Citation2017) and to working longer hours. Single individuals may primarily fulfil their need for relatedness in the work role, possibly with similar co-workers (Wilson & Bauman, 2015); this relatedness is compromised by remote working.

There are also unique non-work challenges for solo-livers. Loneliness is commonly reported amongst the single and childless, with negative wellbeing consequences (Anchor et al., 2018; ONS, Citation2020a), and this has been exacerbated by the social isolation imposed by lockdown measures (Carnevale & Hatak, Citation2020; Gao & Sai, Citation2020). Kamin et al. (Citation2021) explored the cognitive, affective, and behavioural responses of solo-living women in lockdown in Slovenia, noting how a lack of embodied interaction gave rise to dysphoric feelings. Loneliness is compounded when friends are less available, due to their own increased demands at home (e.g. childcare) and/or where common vehicles for interaction (e.g. activities outside the home) are curtailed. Furthermore, negatively-perceived emotions that are felt more broadly at such time, such as anxiety, depression, vulnerability and fear because plans are put on hold (which for single people might include meeting a partner), might be escalated when there is no one sharing the home to alleviate. There might also be a felt lack of purpose at this time (Carnevale & Hatak, Citation2020), compounded by the unknown duration of lockdown (Kamin et al., Citation2021). There are additional challenges posed by a small living space, which is common when living alone (Preece et al., Citation2021), including lack of space for different functions (including homeworking), potentially making it harder to ‘unplug’ from work.

Carnevale and Hatak (Citation2020) called for organisations to consider the unique challenges and demands that single and childless employees face during Covid-19, yet there is little empirical research for organisations to draw upon. This paper aimed to qualitatively explore this issue, focusing on solo-living employees forced to work from home full-time, specifically during the first few months of the first global ‘stay at home orders’ in 2020.

We aimed to: (1) Utilise the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017) and key concepts from the work-life interface literature (Geurts et al., Citation2005) as a conceptual lens to qualitatively explore experiences and perceptions of solo-living staff transitioning to homeworking; (2) Identify job and non-work demands and resources that were lost/reduced and gained/increased during the transition; and how individuals responded to these changes; 3) Explore the impact on the work-life interface; and 4) Consider implications for organisations.

Our contributions to knowledge are: (1) The identification of changes to demands and resources which seem significant to the work-life experience of solo-living staff forced to work from home at the start of the Covid-19 pandemic; (2) Recognition of how changes to the demands/resources of certain employees (with children) impact upon the demands/resources of others (solo-living); (3) The identification of ‘sense of entitlement to support for work-life balance’ as an important personal resource, which impacts the work-life interface; and (4) Solo-friendly recommendations for organisational practice.

Job demands-resources model

The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model (originally Demerouti et al., Citation2001) has been applied to a range of occupational settings (see Lesener et al., Citation2019 for a review) and posits that occupational characteristics can be classified into job demands or job resources, having positive (motivational) or negative (health impairment) outcomes (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007; Schaufeli & Tari, Citation2014).

Job demands are the organisational factors of the job that are associated with physiological and/or psychological outcomes because they require sustained physical/mental effort and are associated with certain physiological and/or psychological costs (Demerouti et al., Citation2001), for example, work overload, physical or emotional job demands. LePine et al. (Citation2005) distinguish between challenging job demands which are motivational (that cost effort but potentially promote personal growth and achievement), and hindering job demands, which are health impairing. Something like increased workload could be classed as either, depending on context, the resources of the individual and their preferences.

Job resources refer to physical, psychological, social, or organisational aspects of the job that are functional in achieving work goals, reduce job demands and the associated costs, or stimulate personal growth, learning, and development (Baker & Demerouti, 2017). These may be at the organisational level (e.g. job security, flexible working policies); workgroup level (e.g. supervisor and co‐worker support); job/role level (e.g. role clarity, autonomy, skill variety); and task level (e.g. performance feedback) (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2007). Job resources particularly influence motivation when job demands are high (they are most needed) (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017), but there can be complicated interaction effects, with resources turning into demands. For example, information availability is seen as a job resource, but if there is a lack of, or an overload of information, it can be viewed as a hindering demand.

Because most psychological approaches assume that human behaviour results from an interaction between personal and environmental factors, the model was extended to incorporate personal resources, the psychological characteristics associated with resiliency and which refer to the ability to control and impact one’s environment (Schaufeli & Tari, Citation2014), such as optimism and self-efficacy, which play a similar role as job resources (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017). Strengths-use (van Woerkom et al., Citation2016) is another personal resource, which can act as a buffer against the health-impairment process of the JD-R model. Strengths are personality traits that are manifested in episodes of personal excellence. Perceived organisational support for strength-use is recognised as a job resource (van Woerkom & Meyers, Citation2015). Workers also have personal demands: ‘the requirements that individuals set for their own performance and behaviour… associated with physical and psychological costs’ (Barbier et al., Citation2013:751), such as perfectionism, emotional instability, and workaholism.

JD-Rs can be affected in a bottom-up way via the individual strategies of employees. This is somewhat different to psychological characteristics, being rather about behaviours. Research identifies a range of strategies for improving JD-R outcomes. One is job crafting (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Citation2001), which can be task crafting, relationship crafting, or cognitive crafting (adjusting the meaning ascribed to work) (see Tims et al., Citation2012). Demerouti (Citation2015) adds boundary management (managing the boundaries between work and home, to help detach from work); coping (problem-focused, emotion-focused, or avoidance); recovery (relaxation, social activities); and goal selection, optimization and compensation—for aiding goal achievement. There is also the possibility of self-undermining behaviours. The non-work situation of the employee is important when thinking of these strategies. Partners and children have a key role in employee psychological detachment from work during off-work time (Hahn & Dormann, Citation2013). During lockdown, cohabiting might influence other individual strategies/behaviours, such as coping, compensation, and the time for/nature of recovery. Yet, limited studies have considered solo-living staff explicitly. More research is needed, to potentially inform training interventions (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017).

Most JD-R studies have been quantitative in nature—setting out a specific set of demands/resources, and testing their impact on worker wellbeing or performance outcomes, with fewer adopting qualitative approaches (e.g. Daniels et al., Citation2013; Servaty et al., Citation2018). Quantitative studies make it hard to explore nuances in individual employee experiences, such as whether a specific job demand is challenging or hindering (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017), or whether access to a particular organisation-level job resource (e.g. flexible working policy) manifests in utilisation, or this being undermined by things like workplace culture/norms; individual sense of entitlement; and/or unsupportive line managers who block take up or make inadequate adjustment (Kossek et al., Citation2011). Adopting qualitative methods to explore JD-Rs can uncover complex interactions, and their purposes which might otherwise be ignored, resulting in possible extensions to the model (Daniels et al., Citation2013). Likewise, it allows for different emerging resources/demands to be identified.

The work-life interface, and relation to JD-R

The work-life interface literature has amassed a considerable number of terms for articulating the relationship between the work and non-work domains. Most research has adopted a restricted conception of both ‘work’ and ‘life’, which does not take account of recent developments in life worlds, working arrangements and employment relationships (Kelliher, et al. 2018). Furthermore, in general there is a ‘work-family’ focus rather than ‘work-life’ exploration (Powell et al., Citation2019). This focus could be seen early in the Covid-19 pandemic, with considerable emphasis on the work-life challenges posed by home-schooling and childcare disruption (i.e. Hjálmsdóttir & Bjarnadóttir, Citation2021). We focus our study on a new work and life context (mandatory full-time homeworking during national lockdown) and focus on ‘life’ factors beyond parenting. We focus on solo-livers, whose family (if any) live elsewhere, and where contact/activities outside the home are limited and/or technologically mediated.

The literature makes a distinction between negative interactions between the two domains, i.e. conflict (especially time- and strain-based) (Greenhaus & Beutell, Citation1985) or negative spillover (Edwards & Rothbard, Citation2000); and positive interactions, i.e. facilitation and enrichment (via additional skills, status enhancement and status security) (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006) or positive spillover (Grzywacz & Marks, Citation2000). It also acknowledges direction of travel. Geurts et al. (Citation2005) classify the ‘work/non-work interface’ in terms of ‘interaction’ which can be negative and/or positive. They integrate the JD-R model into their conceptualising, and crucially recognise how home (or non-work) demands and resources can positively or negatively influence work. This means that in the transition to mandatory homeworking in a national lockdown, we need to consider changes to non-work demands and resources as well as job ones.

Much of Geurts and Demerouti (Citation2003) discussion around non-work demands/resources focuses on spouses/children. Spousal support to discuss work problems at home can help individuals cope better with their work pressures, while participation in multiple roles provides more opportunities and resources that can be used to promote growth and better functioning in other life domains. Moreover, working mothers experience greater happiness because of their dual roles than other women. These non-work resources are not available for solo-living staff and although they may have other life roles (see below), lockdown is likely to have made these less immediate/accessible.

Guerts, et al. (2005) developed a measure of home characteristics including home pressure (i.e. quantitative workload at home), home control (i.e. possibilities to deal with unexpected problems at home), and home support (i.e. support received from people in one’s private life). Demerouti et al. (Citation2018:126) acknowledged that ‘individuals may engage in very diverse roles and activities not restricted to home or family when participating in their nonwork domain, which yet are not well reflected in existing scales’, and that the significance of any role will vary from person to person, due to time investment and other factors. Indeed, single, childless employees are more likely to identify with their personal, non-family roles than employees with other family structures (Wilson & Baumann, Citation2015). Papers cite a range of roles and non-work activities alongside family ones, including religious roles, community involvement, friendships, leisure, self-development, and student roles (i.e. Greenhaus & Kossek, Citation2014).

As well as limited studies on the complexities of the non-work domain, Geurts and Demerouti (Citation2003) note the prevalence of cross-sectional and correlational studies as a limitation in work-life interface research. Such studies do not enable exploration of how the work/non-work interface may change over time, or indeed the impact of ‘critical events’. Our qualitative design, exploring the work-life implications of the transition to homeworking during the ‘critical event’ of Covid-19 lockdown, adds to this literature. The qualitative design also helps explicate how negative and positive interaction between both domains may occur simultaneously within the same persons (Demerouti & Geurts, Citation2004).

Conceptual framework

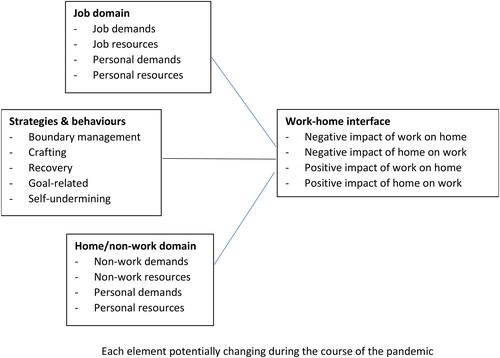

We explore changes to demands and resources in both the job and non-work/home domains, and how these affect the work-life interface. We also explore how personal demands/resources and individual strategies—directed at managing demands/resources in either domain and/or the boundary—may have influence. We draw on Geurts et al. (Citation2005) categories of positive and negative interaction to explain the effect of changes and strategies on the work-life interface ().

Research context: homeworking in a pandemic

The timing and context of this study are important as data collection took place during the Covid-19 pandemic. By the end of March 2020 over 100 countries had introduced full or localised lockdowns which involved the shutdown of parts of the economy, travel and social restrictions (BBC, Citation2020). Workers were encouraged to work from home, regardless of whether a country introduced a national lockdown. While only a minority of jobs could be carried out at home because of the nature of the work, data suggests that homeworking increased in most countries. The ONS (2020 b) reported 47% of UK employees doing some work from home in April 2020, 86% of which was attributed to Covid-19. During the same time-period in the US, working from home increased from 17% pre-pandemic to 44%. Participants in this study who lived in the UK, Poland and India entered national lockdown from mid-March 2020, while those who lived in the US and Brazil experienced localised lockdowns (BBC, Citation2020). While the length of lockdowns varied across countries, when data collection for this study took place (May to July 2020) all participants were working exclusively at home.

As remote working has been an employment feature for some time, there is a considerable body of research which can provide insight into job demands and resources likely affected by a transition from employer premises to homeworking, including some that utilise the JD-R model (i.e. Sardeshmukh et al., Citation2012; Van Steenbergen et al., Citation2018). A paradox has been observed in relation to remote worker wellbeing and the work-life interface, with increased flexibility, autonomy, engagement, productivity, and work-life balance in some (Coenen & Kok, Citation2014) being set against blurring work-life boundaries, work intensification and/or longer hours (Golden et al., Citation2006; Falstead & Henseke, 2017), exacerbated by increased technology use and technostress (Suh & Lee, Citation2017). Other challenges include deterioration of relationships with co-workers/supervisors (Golden, Citation2006) leading to reduced support and increased loneliness (Mann & Holdsworth, Citation2003). Remote work is not the same as mandatory homeworking however. Remote working often provides a degree of location flexibility (including the option of days in the office and other locations), and most research has focussed on a requested, permanent arrangement, that management/employees have been able to plan/prepare for. Furthermore, some of the challenges associated with remote working are linked to the employee being ‘other’ to the rest of the team/workforce, such as career progression concerns (Golden et al., Citation2008). The mandatory transition to homeworking, at very short notice, for often entire departments/workforces provides a unique research context. General studies of wellbeing and the work-life interface for remote workers during covid have highlighted a number of concerns, including work intensification; ‘always on’ expectations; mental health implication; professional isolation; challenges in balancing non-work commitments; technostress; and issues around finding suitable private workspace (See Shirmohammadi et al., Citation2022 for review). Most studies fail to consider living arrangement beyond parental status, and hence provide little evidence of the experience of solo-living staff. Studies have also noted the challenges for remote/virtual managers, in terms of monitoring dispersed teams and individualising support for those who are struggling—often with little or no training for this role (Gallup, 2022). This can increase manager workloads, at a time when capacity is stretched in other ways, and when their own non-work demands are likely increasing (Pass & Ridgway, Citation2022).

Method

Consistent with the aims of the study, we adopted an interpretivist epistemological position to explore the experiences of solo-living workers as they transitioned to homeworking from their normal place of work. We used an exploratory, qualitative research design to collect data that was context sensitive (Cooke, Citation2018) given that it was obtained during a pandemic under the circumstances of national lockdowns. Following Wengraf (Citation2011), we used a biographical narrative approach to facilitate our understanding of the participants’ experiences and perceptions of working and living alone. This approach was chosen to identify issues the participants found important, rather than imposing our own frame of reference.

Recruitment, sampling procedure and participants

Given the context, we adopted a purposive approach to recruit solo-livers, utilising social media and existing networks. Following University research ethics approval, details of the study were shared across the authors’ and institution’s research social media accounts. The first author also approached the administrator of a large, global ‘singles network’ on Facebook, who authorised promotion of the study amongst group members. Individuals who expressed an interest in taking part were sent a participant information sheet outlining the study purpose, sampling criteria, how their data would be managed and their rights to withdraw. Participants were assured of anonymity and interview transcripts were duly anonymised. The inclusion criteria were that participants lived alone, were employed, and were required to work from home due to the pandemic. Participants returned a completed consent form prior to interview. We also used snowball sampling as a recruitment strategy - upon completion of the interviews, participants were asked if they could refer other solo-livers to the research. shows the participant characteristics. Interviews were conducted virtually, allowing us to recruit participants outside the UK gaining a range of perspectives. Some of the participants had a degree of location flexibility prior to the pandemic, but this equated to hybrid working, with 1–2 days per week spent outside of the workplace, either at home or a café. Mandatory full-time homeworking was new to all participants.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Data collection and analysis

In-depth interviews were conducted by the first and third authors, typically lasting an hour. Our narrative interviewing approach involved an open-ended question in terms of: ‘what work, and life outside of work, was like for you before the pandemic lockdown, and how has this changed—what work, and life outside of work, is like now’. Follow-up questions elicited more detail of their perceptions of living alone at this time, the importance of work, workload, work-life boundaries, impact of technology, financial concerns, perceptions of fairness, contacts with manager, colleagues, friends and family.

The data were organised and analysed using template analysis (King, Citation2004), a type of thematic analysis that involves categorising, and coding textual data in relation to identified themes. Firstly, all the authors read and re-read the interview transcripts for familiarisation with the data, then discussed and reflected upon the data. Following this reflective process, the next phase involved interpretation of the data. Running through the participant accounts were factors which they identified as facilitating or exacerbating, that provided insight into their transition to homeworking. We categorised these as resources and demands. The first author carried out preliminary thematic coding of the data based on the JD-R conceptual model. Themes were organised into ‘meaningful clusters’ (King & Brooks, Citation2017: 226) in terms of demands and resources (job and personal) specifically focusing on existing, new/enhanced, and lost/diminished aspects identified by respondents. The template was further refined following further discussions around how demand/resource changes intersected with the work-life interface, and personal strategies. The participants’ narratives, and our interpretation, were understood as socially constructed, in line with our epistemological position. While we draw upon the JD-R and Geurts et al. (Citation2005) work-life interaction conceptual models to facilitate our interpretation of the data and present an account, this is not intended as definitive.

We sought credibility of our data by allowing solo-livers space to express themselves freely about their experiences of homeworking during lockdown, clarifying key issues with participants during the interview. In addition, the second author read through all the interview transcripts and agreed that the interpretation was useful in making sense of the data.

Findings

This section presents our findings relating to participant perceptions of job and personal demand/resource changes during the transition to homeworking; how they reacted to these changes; and the impact on both work and home (negative or positive). We focus our discussion on elements that are specific to/exacerbated by solo-living status. Whilst the sample included demographic diversity and several national contexts, the similarity of experiences was striking. As such, and due to word constraints, the findings focus on themes in the sample as a whole.

Negative influence on the work-life interface

A key demand raised by participants was the additional workload they experienced. Participants described how the nature of their work went through a fundamental change in a relatively short space of time, as face-to-face interactions moved online. Those working in education referred to the time it took to learn new technologies, and how teaching sessions took longer to prepare and (re)record. Work became more ‘intensive’ as educators transitioned to online teaching. P2 referenced back-to-back ‘emergency meetings’, with P7 referring to the online move as ‘absolutely manic’ resulting in ‘a lot of meetings, a lot of decisions that were being made and then changed’. As such, most workload increase was experienced as a hindering demand (LePine et al., Citation2005).

Measures were introduced by some employers to help those with parental and caring responsibilities, like flexible and/or reduced hours (including ‘special leave’ arrangements). While participants recognised this need for those colleagues, they also noted that if uptake was high, it impacted their own workload further, as work was reallocated, especially if they worked in smaller teams:

that does put a lot more pressure on those of us that are still working five days a week…I don’t get special leave…because I don’t have kids, and I don’t have a reason to take that special leave. So it’s been full on for 12 weeks (P29).

Participants noted examples of workplace policies or communications that excluded/ignored their needs which provoked feelings of unfairness. These were ostensibly job resources for all employees at this challenging time, which backfired in the case of solo-livers. One example came from P13 and concerned a pay cut decision linked to the pandemic, with an exemption for employees whose partner had lost their job/income (job resource of financial security). Her sense of unfairness was strong:

these suck for single people. Like this really screws me over…obviously they’re not going to help me…I was fuming.

A similar issue at the team-level was mentioned by P15:

I mentioned this to my supervisor, […] when they’re talking about people in general they’re like ‘hey have a good weekend, spend time with your family’, just saying nice things, but without realising that not everybody is quarantining with somebody. […] Just FYI, when things like that are said it makes me feel a little bit bad.

Additional technology use was identified as an increased job demand as meetings were held virtually, and increased meeting volume. For many, this was accompanied by a need to learn new technologies, or to use technology in different ways. Whilst this was experienced as a challenging demand (LePine et al., Citation2005) for some (a new opportunity, and developing their skillset), many considered it to be a hindering demand, reporting technology overload and technostress. This had a specific negative work-home impact for solo-livers because it discouraged technology use outside of work, and this was the primary route to social interaction with friends and family. Ultimately, this reduced their opportunities for social support (non-work resource) at a time when this was already significantly disrupted. P5 reflected upon the term ‘Zoomed out’, and the implications for their non-work experience:

It’s back-to-back [zoom calls at work], and your head at the end of the day is about to explode. You’re knackered. [….] I was getting to the point where some of the lads were like ‘are we having a Zoom tonight?’, and I’d be like ‘ah, I’ve been on it all day, I can’t see straight. I love you, but I can’t’.

my manager has three kids that he’s home-schooling, so I’m not going to ring him up and moan about my stiff neck [laughs]. He’s got enough on his plate, hasn’t he? (P8)

We mentioned the job resource of financial security above. This was a concern for many participants—in terms of redundancy or pay reduction (actual, threatened or perceived possible). Whilst co-habiting employees also face financial pressures, the potential of redundancy was perceived as more significant for solo-livers: ‘I don’t have anybody else to fall back on’ whereas ‘a married person, I think, at least you have your husband or wife to help with the payments if they’re still working’ (P11). As P24 argued: ‘Because I’m single…I kind of know that whilst I’m not vulnerable from a health perspective, I am vulnerable financially’. Participants felt these concerns were not acknowledged in their organisations, as evident in the pay cut example cited earlier. Concerns over potential changes to job resources (in a time of change/uncertainty), as well as actual changes, can have an impact on behaviours and the work-life interface (worries spilling over into non-work time).

Positive influence on the work-life interface and strategies

The transition to homeworking provided flexibility (increased job resource) that was positive for many. Working from home had been unavailable to many before lockdown, or for some, where it was potentially available, it was not previously utilised. P20 stated:

…I think as a single person I have hesitated to ask for flexibility, like, ‘oh, I want to work from home today just because, right?’… I didn’t feel comfortable asking for that. Compared to people who had reasons like ‘my child is ill’ or whatever.

Interestingly, where no explicit message was provided by the employer/manager on working hours, several participants seized the opportunity to incorporate flexibility to a greater extent, as a form of job crafting (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, Citation2001) to accommodate preferences and non-work needs. This indicates some sense of entitlement to work-life balance, which for certain participants, emerged over time in this new work-life context:

I did initially stick to nine to five, and then perhaps, when there weren’t so many emails, I just thought, well, actually I don’t have to stick rigidly, I could finish at four and actually go for a walk. (P9)

I thought, OK I’m going to log off, […] do a home workout or watch an episode of something on Netflix, and then come back to this…And nobody gave me any flack for it (P16)

[I set] up my therapy area at the start of the day, and tak[e] it down at the end. I get dressed in the same way as I would for work, and put my makeup on, and then get dressed into my chill out clothes at the end of the day.

There was also evidence of other work-life strategies employed in the sample. Many of the participants engaged in non-work/home crafting (see Demerouti et al. 2019), in terms of relationships and activities, to maximise their own wellbeing. This is likely to have positive spillover effects in the workplace. Another strategy employed was compensation (Demerouti, Citation2015), with the job increasing in perceived importance as resources/roles were reduced/less available in the home domain:

All you have in this particular situation is your job…the job is more important than anything else because that seems to be the only thing that you can depend on (P49)

Patterns and change over time

There did not seem to be any specific factor that explained why some participants experienced the transition in a more positive or negative way, including whether the individual had experienced remote/hybrid working before the pandemic. Vaziri et al. (Citation2020) quantitatively explored changes to the work–family interface during the Covid-19 pandemic, for mainly married employees, and noted that negative transitions were more likely where individuals had high segmentation preferences, engaged in emotion-focused coping, experienced higher technostress, and had less compassionate supervisors. In our study, the most influential factors appeared to be the importance and nature of non-work activities pre-pandemic, and how much these were affected by the lockdown and changes to work; changes to workload; whether employees made use of temporal flexibility (either due to organisation policy, management support or job crafting); and the nature of communications with management and colleagues.

The narratives collected in this study illustrated how JD-Rs, non-work demands and resources, and individual strategies, were evolving for participants. Individuals reported changes to workloads, organisational policies, team communications, manager contact, and other important job factors over time, from the point of lockdown to the point of interview. They also reported changes to lockdown rules (i.e. the introduction of ‘support bubbles’ for those who live alone in the UK in June 2020Footnote1), and changes to how they responded to the new way of life. It is possible that some of the participants who seemed to be struggling the most with the transition, might have adapted better over time.

Discussion

Our findings highlight several challenges for solo-living staff, caused by changes to job and non-work demands and resources (and their interactions) associated with a mandatory transition to homeworking. Whilst many of the demands cited were not specific to solo-livers, such as increased workload, increased technology use, and financial insecurity, these caused unique challenges for solos due to their intersection with their specific living arrangement, at this time. For example, increased workloads and technology use limited the time that individuals were willing/able to use technology outside of work to communicate with friends and family—and for this demographic, that was the primary route to social support.

As with prior research on the experiences of solo-living staff, sense of entitlement to support for the work-life interface and perceptions of fairness were key themes in our data (Wilkinson et al., Citation2017; Wilkinson et al., Citation2018; Casper & Swanberg, Citation2009; Akanji et al. 2019). Whilst work demands changed for many employees due to the pandemic, there was a clear sense that the needs of working parents were seen to be prioritised. Whilst some participants reported inclusive workplace policies (especially around increased temporal flexibility, or a temporary reduction in some workloads whilst people adjusted to the pandemic/lockdown-induced changes), these were a minority. Most reported workloads being increased due to covering for colleagues with family commitments, potential temporal flexibility being undermined by the flexibility of others (due to their family commitments), and exclusionary new resources/supports that were ostensibly for all. It can be concluded that organisational-level support for personal work-life balance is a job resource that is often more available to working parents.

A sense of entitlement to support for work-life balance is arguably a related personal resource, that has not been acknowledged in prior JD-R research. Personal resources are the psychological characteristics that are associated with resiliency and which refer to the ability to control and impact one’s environment (Schaufeli & Tari, Citation2014). Sense of entitlement to support arguably gives the power to take advantage of available policies and/or engage in job crafting, and is influenced by organisational culture, management actions and team norms. Some participants in our sample seized the opportunity for temporal flexibility, even without overt ‘permission’ from their employers. They adapted their work routine to take advantage of opportunities in the non-work domain for activities that were positive to their wellbeing. Others appeared to have a sense of entitlement to support, but felt betrayed by their employer for not delivering, hence reporting negative emotions and unfairness. Whilst Wilkinson et al. (Citation2018) found such sense of unfairness to be limited, due to a general perception that parents need support more, it could be that the pandemic has levelled the playing field in terms of the perceived importance of wellbeing for all, influenced by social narratives around self-care at a difficult time. The negatively-perceived emotion of inequity/sense of unfairness is likely to ‘spillover’ into the non-work domain, and may negatively impact wellbeing (perhaps exacerbated where there is no one in the home domain to ‘vent’ to). This issue could be further explored in future research. Other participants appeared to have little sense of entitlement to support for their work-life interface, and sometimes struggled with the change to their work and non-work demands and new work-life boundaries (having ineffective personal strategies). Where managers are not regularly checking in on their employees and offering support, this has potentially negative effects on employee wellbeing and productivity. Job crafting will only be a reality if employees are encouraged to do this and have the skills.

Contributions

This paper contributes a qualitative exploration of the interaction of job and non-work demands and resources and personal work-life strategies on the work-life interface, at a time of considerable change to each, due to the ‘critical event’ (Geurts & Demerouti, Citation2003) of Covid-19 lockdowns. The focus is an understudied group in organisation studies—employees who live alone.

We contribute to the JD-R literature by identifying organisational-level support for personal work-life balance as a job resource, and how this is not equal for all. This has relevance for all workers, but perhaps most notably those with stigmatized family identities (see Anand and Mitra, 2021). We show how the JD-Rs of certain employee groups can have an impact on other groups and highlight the importance of social comparison in assessment of changing demands/resources. Finally, we contribute sense of entitlement to support as a personal resource.

We contribute to the work-life balance literature, and especially the work of Guerts and colleagues, by identifying non-work demands and resources that are important to consider when investigating how job roles intersect with employee domestic situation, beyond parental status. We identify personal isolation; size of the home; social support within the home; and ability to engage in activities/roles outside the home (including activities like regular weekends away) as potentially influential in terms of how work demands affect an employee. More broadly, we add to the limited studies focusing on the work-life interface of solo-living employees. Our qualitative methodology in a unique context allowed us to explicate varied work-life strategies that solo-living employees employ to deal with disruption to both their work and non-work lives, some of which may need monitoring/support. We contribute to the remote working literature by identifying a lack of consideration for cohabitation status in most studies, as a distinct variable from parental status (presence of children). This will be important to consider with hybrid working potentially becoming the ‘new normal’ post-pandemic.

Our conceptual framework and findings could inform largescale quantitative studies which compare the experiences of solo-living staff to other demographic groups, in a range of employment contexts, including remote and hybrid working.

Implications for practice

Organisations should consider their suite of policies, practices and work-life balance provisions to ensure they genuinely cater for the needs of all staff, paying particular attention to work-life/flexibility policies that are ostensibly for all, but in practice may be normatively reserved for those with young children. Senior managers, HR, and internal marketing functions should consider perceptions of fairness, and consider solo-living employees as a distinct group with unique needs when thinking of workplace policies and communications, to ensure that positive intentions do not backfire. Casper et al. (Citation2007) define one key component of a singles-friendly culture (at work) as equal respect for non-work roles. Focus groups could be held with solo-living staff to gauge perception of current policies and culture.

Increased job demands need to be given careful consideration when it comes to any crisis/change situation. Work should be done to ensure that additional demands are avoided or offset by the alleviation of other demands and/or additional resources. If increased workload is inevitable, and additional headcount is not an option, can non-essential tasks be removed, or deadlines extended? Is there opportunity for new skills-use, to make an increase in workload feel like a challenge, rather than hindering, demand, or increased social support or shared meaning (Anchor, et al. 2018)? Care should be taken that steps to ease the demands of one cohort, do not increase demands for another.

In times of change (job and/or personal), managers should have regular communications with each affected employee, to discuss demands and resources, work-life interactions, and what supports might be needed. Care should be taken to ensure that communication is perceived as necessary, and the frequency appropriate, to avoid fatigue (Waizenegger et al., Citation2020; Bennett et al., Citation2021). Managers could raise awareness through team discussions of the various challenges that may be experienced by colleagues, along with the potential impacts of certain practices. Focussing on general challenges allows for a wider discussion of potential issues, but is less likely to breach privacy preferences. There could also be coaching for all staff on strategies to improve the work-life interface, as well as coping strategies for future crisis contexts (Vaziri et al., Citation2020).

Employers could consider offering specific support to address non-work demands around loneliness and isolation. Relationship-oriented HR systems, such as network-development, training, and feedback to strengthen meaning and purpose, social clubs/groups at work and connecting employees to volunteer opportunities/community involvement groups, might help staff prepare for further unanticipated events that lead to feelings of social exclusion (Carneval & Hatak, 2020; Wilson & Baumann, Citation2015). These could form part of what Pass and Ridgway (Citation2022) call an ‘umbrella of engagement practices’, which allow individualized take-up and reduce pressure on line managers. Employees can be involved in the design.

Limitations

One limitation of the study is the self-selection nature of participation. A representative sample of all solo-living employees was challenging to achieve, as those who were struggling the most might have been too depressed or busy to participate. Similarly, individuals who felt that their job had not changed much, and who were not struggling at this time, might have thought they had nothing much to say, hence not volunteered. Our study took place at a unique time of enforced homeworking during a global pandemic and as such is not generalisable. However, our findings are transferable to work situations where organisations mandate working at home and highlight the importance of planning largescale changes to the way work is done; ensuring perceived fairness in new policies (via inclusion in design); and supporting managers to support the needs of different employee groups, including those who live alone. In addition, our approach could be utilised to explore employee narratives of other significant organisational, job (i.e. expatriation) and/or personal-life (i.e. divorce) changes, where demands and resources in the work and/or non-work domains significantly change, to explore the interactions, employee work-life strategies, and the impact on the work-life interface.

Conclusion

In this article we used the Job Demands-Resources model (Bakker & Demerouti, Citation2017) and key concepts from the work-life interface literature (Geurts et al., Citation2005) as a conceptual lens to explore the narratives of 35 solo-living staff transitioning to enforced homeworking during the first national lockdowns in connection with Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. We sought to identify job and non-work demands and resources that were lost/reduced and gained/increased during the transition; how individuals responded to these changes; and explore the impact on the work-life interface.

We identified several changes to job-demands and resources linked to the transition to enforced homeworking which were especially problematic in terms of the work-life interface of solo-living staff: 1) additional workload, exacerbated by parent colleagues using special provisions; 2) additional work-related technology use, which negatively impacted technology use for social support in the non-work domain; 3) reduced embodied social support from colleagues; 4) reduced line manager support; 5) loss of the designated work space in the office; and 6) reduced financial security. The key changes to non-work demands and resources were an increase in isolation; reduced social support; and loss of/reduction in the salience of activities and roles other than worker. Loss of personal resources can exacerbate the impact of work demands, and new demands (such as isolation) can have an impact psychologically, can spillover into the work domain, and can influence personal demands (such as workaholism). The challenges were offset for some by the temporal flexibility afforded by remote working, and personal strategies such as job crafting, creative segmentation strategies, non-work/relationship crafting and avoidance.

Novel emerging findings concerned the impact of changes to colleague/manager JD-Rs on individual employee JD-Rs and work-life interface; the impact of perceptions of fairness over resource allocation; and the impact of sense of entitlement to support for the work-life interface—which we term a ‘personal resource’.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Editor and the anonymous reviewers for their advice and support through the publications process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and analysed during this study are not publicly available due to the terms of the ethical approval granted by [name] University Ethics Committee

Notes

1 On 13th June 2020, people in the UK who lived alone were permitted to form a ‘support bubble’ with another household, without being in breach of lockdown rules.

References

- Akanji, B., Mordi, C., Simpson, R., Adisa, T. A., & Oruh, E. S. (2020). Time biases: Exploring the work–life balance of single Nigerian managers and professionals. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 35(2), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-12-2018-0537

- Anand, S., & Mitra, A. (2022). No family left behind: Flexibility i-deals for employees with stigmatized family identities. Human Relations, 75(5), 956–988. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726721999708

- Bakker, A. M., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands‐Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- Bakker, A. M., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285.

- Barbier, M., Hansez, I., Chmiel, N., & Demerouti, E. (2013). Performance expectations, personal resources, and job resources: How do they predict work engagement? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(6), 750–762. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.704675

- BBC (2020). ‘Coronavirus: The world in lockdown in maps and charts’. 7 April 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-52103747.

- Bennett, A. A., Campion, E. D., Keeler, K. R., & Keener, S. K. (2021). Videoconference Fatigue? Exploring Changes in Fatigue after Videoconference Meetings during COVID-19. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(3), 330–344.

- Carnevale, J. B., & Hatak, I. (2020). Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: Implications for human resource management. Journal of Business Research, 116, 183–187.

- Casper, W. J., & Swanberg, J. E. (2009). Single childfree adults: The work-life stress of an unexpected group. In Antoniou, A. G., Cooper, C. L, Chrousos, G. P., Speilberger, C. D., & Eysenck, M. W. (Eds.), Handbook of managerial behavior and occupational health (pp. 95–107). Edward Elgar.

- Casper, W. J., Weltman, D., & Kwesiga, E. (2007). Beyond family-friendly: The construct and measurement of singles-friendly work culture. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70(3), 478–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.01.001

- CIPD (2020). Reward in the time of Covid-19. CIPD Voice, Issue, 23. Online: https://www.cipd.co.uk/news-views/cipd-voice/issue-23/reward-during-covid19#gref

- Coe, E., Enomoto, K., Herbig, B., & Stueland, J. (2021). COVID-19 and burnout are straining the mental health of employed parents, Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/covid-19-and-burnout-are-straining-the-mental-health-of-employed-parents?cid=eml-web.

- Coenen, M., & Kok, R. A. (2014). Workplace flexibility and new product development performance: The role of telework and flexible work schedules. European Management Journal, 32(4), 564–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2013.12.003

- Cooke, F. L. (2018). Concepts, contexts, and mindsets: Putting human resource management research in perspectives. Human Resource Management Journal, 28(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12163

- Daniels, K., Glover, J., Beesley, N., Wimalasiri, V., Cohen, L., Cheyne, A., & Hislop, D. (2013). Utilizing job resources: Qualitative evidence of the roles of job control and social support in problem solving. Work & Stress, 27(2), 200–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2013.792471

- Dawes, J., May, T., McKinlay, A., Fancourt, D., & Burton, A. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health and wellbeing of parents with young children: A qualitative interview study. BMC Psychology, 9(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00701-8

- Demerouti, E. (2015). Strategies used by individuals to prevent burnout. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 45(10), 1106–1112. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12494

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.499

- Demerouti, E., Corts, I. M., & Boz, M. (2018). A closer look at key concepts of the work-nonwork interface. In Current Issues in Work and Organizational Psychology. (pp. 124–139). Routledge.

- Demerouti, E., & Geurts, S. (2004). Towards a typology of work-home interaction. Community, Work & Family, 7(3), 285–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/1366880042000295727

- Demerouti, E., Hewett, R., Haun, V., De Gieter, S., Rodríguez-Sánchez, A., & Skakon, J. (2020). From job crafting to home crafting: A daily diary study among six European countries. Human Relations, 73(7), 1010–1035. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719848809

- Dumas, T., & Perry-Smith, J. (2018). The paradox of family structure and plans after work: Why single childless employees may be the least absorbed at work. Academy of Management Journal, 61(4), 1231–1252. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0086

- Edwards, J. R., & Rothbard, N. P. (2000). Mechanisms linking work and family: Clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. The Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 178–199. https://doi.org/10.2307/259269

- Eurostat (2021). Household Statistics Explained. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Household_composition_statistics

- Gao, G., & Sai, L. (2020). Towards a ‘virtual’ world: Social isolation and struggles during the COVID‐19 pandemic as single women living alone. Gender, Work, and Organization, 27(5), 754–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12468

- Gallup (2021). State of the Global Workplace 2021 Report. Gallup. Available at: https://www.gallup.com/workplace/349484/state-of-the-global-workplace.aspx

- Golden, T. D. (2006). The role of relationships in understanding telecommuter satisfaction. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.369

- Golden, T. D., Veiga, J. F., & Dino, R. N. (2008). The impact of professional isolation on teleworkers job performance and turnover intentions: Does time spent teleworking, interacting face-to-face time, or having access to communication-enhancing technology matter? The Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1412–1421. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012722

- Golden, T. D., Veiga, J. F., & Simsek, Z. (2006). Telecommuting’s differential impact on work-family conflict: Is there no place like home? The Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1340–1350.

- Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. The Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/258214

- Greenhaus, J. H., & Kossek, E. E. (2014). The contemporary career: A work–home perspective. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 361–388. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091324

- Grzywacz, J. G., & Marks, N. F. (2000). Reconceptualizing the work–family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.111

- Geurts, S. A., & Demerouti, E. (2003). Work/non-work interface: A review of theories and findings. In Marc J. Schabracq, Jacques A.M. Winnubst, Cary L. Cooper The handbook of work and health psychology., pp: 279–312. John Wiley & Sons.

- Geurts, S. A., Taris, T. W., Kompier, M. A., Dikkers, J. S., Van Hooff, M. L., & Kinnunen, U. M. (2005). Work-home interaction from a work psychological perspective: Development and validation of a new questionnaire, the SWING. Work & Stress, 19(4), 319–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370500410208

- Hahn, V. C., & Dormann, C. (2013). The role of partners and children for employees’ psychological detachment from work and well-being. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(1), 26–36. 10.1037/a0030650

- Hjálmsdóttir, A., & Bjarnadóttir, V. S. (2021). “I have turned into a foreman here at home”: Families and work–life balance in times of COVID‐19 in a gender equality paradise. Gender, Work, and Organization, 28(1), 268–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12552

- Jack, T., Ivanova, D., Gram-Hanssen, K., & Buchs, M. (2021). As the number of people living alone goes up globally, what this might mean for the environment. https://www.firstpost.com/living/as-number-of-people-living-alone-goes-up-globally-what-this-might-mean-for-the-environment-9421531.html

- Kamin, T., Perger, N., Debevec, L., & Tivadar, B. (2021). Alone in a time of pandemic: Solo-living women coping with physical isolation. Qualitative Health Research, 31(2), 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732320971603

- Kelliher, C., Richardson, J., & Boiarintseva, G. (2019). All of work? All of life? Reconceptualising work‐life balance for the 21st century. Human Resource Management Journal, 29(2), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12215

- King, N. (2004). Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In C. Cassell & G. Symon (Eds.), Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research. (pp. 256270). Sage.

- King, N., & Brooks, J. (2017). & Thematic analysis in organisational research. In Cassell, C., Cunliffe, A. L., & Grandy, G. (Eds.). The sage handbook of qualitative business and management research methods. Sage.

- Kollewe, J. (2021). Zurich insurance firm offers fully paid ‘lockdown leave’ in UK. The Guardian. Online: https://www.theguardian.com/business/2021/jan/06/zurich-insurance-firm-fully-paid-lockdown-leave-uk-parents-carers-covid

- Kossek, E. E., Pichler, S., Bodner, T., & Hammer, L. B. (2011). Workplace social support and work–family conflict: A meta‐analysis clarifying the influence of general and work–family‐specific supervisor and organizational support. Personnel Psychology, 64(2), 289–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01211.x

- LePine, J. A., Podsakoff, N. P., & LePine, M. A. (2005). A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 48(5), 764–775. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.18803921

- Lesener, T., Gusy, B., & Wolter, C. (2019). The job demands-resources model: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Work & Stress, 33(1), 76–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2018.1529065

- Mann, S., & Holdsworth, L. (2003). The psychological impact of teleworking: Stress, emotions and health. New Technology, Work, and Employment, 18(3), 196–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-005X.00121

- Nieuwenhuis, R., & Yerkes, M. A. (2021). Workers’ well-being in the context of the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Community, Work & Family, 24(2), 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2021.1880049

- ONS (2019). The cost of living alone. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/families/articles/thecostoflivingalone/2019-04-04

- ONS () Coronavirus and loneliness (2020a)., Great Britain: 3 April to 3 May 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/bulletins/coronavirusandlonelinessgreatbritain/3aprilto3may2020

- ONS (2020b). Coronavirus and homeworking in the UK: April 2020. Statistical Bulletin. https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/coronavirusandhomeworkingintheuk/april2020.

- Pass, S., & Ridgway, M. (2022). An informed discussion on the impact of COVID-19 and ‘enforced’ remote working on employee engagement. Human Resource Development International, 25(2), 254–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2022.2048605

- Powell, G. N., Greenhaus, J. H., Allen, T. D., & Johnson, R. E. (2019). Advancing and expanding work-life theory from multiple perspectives. Academy of Management Review, 44(1), 54–71. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2018.0310

- Powell, A., & Francis-Devine, B. (2021). ‘Coronavirus: Impact on the labour market’ Commons Library Research Briefing, UK Government. Online: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8898/CBP-8898.pdf

- Preece, J., McKee, K., Robinson, D., & Flint, J. (2021). Urban rhythms in a small home: COVID-19 as a mechanism of exception. Urban Studies, Onlinefirst 004209802110181. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211018136

- Sardeshmukh, S. R., Sharma, D., & Golden, T. D. (2012). Impact of telework on exhaustion and job engagement: A job demands and job resources model. New Technology, Work and Employment, 27(3), 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-005X.2012.00284.x

- Schaufeli, W. B., & Tari, T. W. (2014). A Critical Review of the Job Demands-Resources Model: Implications for Improving Work and Health., In Bauer, GF. & Hammig, O. (Eds.), Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health: A transdisciplinary approach. Ch 4 (pp. 43–68). Springer.

- Servaty, R., Perger, G., Harth, V., & Mache, S. (2018). Working in a cocoon: (Co)working conditions of office nomads–a health related qualitative study of shared working environments. Work (Reading, Mass.), 60(4), 527–538. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-182760

- Shirmohammadi, M., Au, W. C., & Beigi, M. (2022). Remote work and work-life balance: Lessons learned from the covid-19 pandemic and suggestions for HRD practitioners. Human Resource Development International, 25(2), 163–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2022.2047380

- Suh, A., & Lee, J. (2017). Understanding teleworkers’ technostress and its influence on job satisfaction. Internet Research, 27(1), 140–159.

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

- US Census (2021)., Living arrangements over the decades. Released Nov 29 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/2021/comm/living-arrangements-over-the-decades.html

- Van Steenbergen, E. F., van der Ven, C., Peeters, M. C. W., & Taris, T. W. (2018). Transitioning towards new ways of working: Do job demands, job resources, burnout, and engagement change? Psychological Reports, 121(4), 736–766. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294117740134

- van Woerkom, M., & Meyers, M. C. (2015). My strengths count! Effects of a strengths‐based psychological climate on positive affect and job performance. Human Resource Management, 54(1), 81–103. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21623

- van Woerkom, M., Oerlemans, W., & Bakker, A. B. (2016). Strengths use and work engagement: A weekly diary study. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(3), 384–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2015.1089862

- Vaziri, H., Casper, W. J., Wayne, J. H., & Matthews, R. A. (2020). Changes to the work–family interface during the COVID-19 pandemic: Examining predictors and implications using latent transition analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(10), 1073–1087. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000819

- Waizenegger, L., McKenna, B., Cai, W., & Bendz, T. (2020). An Affordance Perspective of Team Collaboration and Enforced Working from Home during COVID-19. European Journal of Information Systems, 29(4), 429–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1800417

- Wengraf, T. (2011). Interviewing for life-histories, lived periods and situations, and ongoing personal experiencing using the Biographic-Narrative Interpretive Method (BNIM): The BNIM Short Guide bound with The BNIM Detailed Manual, version 11.07. Available at: [email protected]

- Wilkinson, K., Tomlinson, J., & Gardiner, J. (2017). Exploring the work-life challenges and dilemmas faced by managers and professionals who live alone. Work, Employment and Society, 31(4), 640–656. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017016677942

- Wilkinson, K., Tomlinson, J., & Gardiner, J. (2018). The perceived fairness of work–life balance policies: A UK case study of solo‐living managers and professionals without children. Human Resource Management Journal, 28(2), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12181

- Wilson, K. S., & Baumann, H. M. (2015). Capturing a more complete view of employees’ lives outside of work: The introduction and development of new interrole conflict constructs. Personnel Psychology, 68(2), 235–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12080

- Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2001). Crafting a job: Revisioning employees as active crafters of their work. The Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 179–201. https://doi.org/10.2307/259118

- Young, S. (2021). ‘Coronavirus: How to work from home when you have children’ The Independent. Online: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/coronavirus-working-from-home-parents-children-tips-routine-a9414261.html