ABSTRACT

We aim to identify and validate the key dimensions of the employer brand scale in Romania, based upon an online survey with 310 participants. Confirmatory factor analysis and regression analysis are used to demonstrate that the measurement of employer brand used in Western contexts needs to be adjusted in Romania. A second order construct shows that only four dimensions are relevant: development, social, economic, and interest value (not the application value). We recommend changes to the scale of employer attractiveness and demonstrate that the modified scale predicts positive work outcomes, such as job satisfaction, which further underscores its relevance for employee recruitment. The insights are important for practitioners in Romania, as they provide an appropriate tool for evaluating and designing employer branding strategies. Our results confirm the importance of employer branding strategies in the form of employer attractiveness dimension enhancements for recruitment and retention. Our research also expands knowledge on employer branding by showing that employer attractiveness is associated with positive work outcomes.

Introduction

Employer branding has been presented as a strategic tool in human resources management to attract and retain talented employees (Michaels et al., Citation2001; Tanwar & Prasad, Citation2017; von Wallpach et al., Citation2017). It is also on the agenda of practitioners, including recruiting firms, government, employment bodies and human resources professionals, as a way of applying branding principles to the employee–employer relationships (CIPD, Citation2009). Hence, various practitioner indexes have been developed around the world to assess employer brand attractiveness (i.e. Great Place to Work, TNS Gallup’s Index of the Most Attractive Employer, Canada’s Top 100 Employers, and Britain’s Top Employers).

However, the concept still lacks academic work that probes its nature, structure, mechanisms, and validity. Additionally, prior studies have primarily researched Western contexts (Ambler & Barrow, Citation1996; Berthon et al., Citation2005; Turban et al., Citation1998), with little consideration of how it is understood or applied in developing countries. We therefore ask if employer attractiveness dimensions hold in Romania – a developing Eastern European context – and assess its ability to predict positive work outcomes. In doing so, we address a common methodological problem for researchers, i.e. how to make use of existing (very often US centric) measures in very different cultural contexts. This is important as developing countries and related economic, social, and legal factors make simplistic application of models based upon developed markets (such as the U.S.) an imperfect choice.

We therefore build on Berthon et al. (Citation2005) work who developed and validated a multi-item scale to identify and operationalise the components of employer attractiveness (the EmpAt Scale). Berthon et al. (Citation2005) identified five distinct dimensions of employer attractiveness (i.e. interest, social, economic, development, and application value), and provided evidence on the validity and reliability of their scale. They also encouraged further research to improve and refine the scale, and our study does this by focussing on Romania. Using a dataset collected in the banking sector, we analyse the dimensions of the employer attractiveness scale. Results demonstrate that Berthon et al. (Citation2005) application value dimension does not fit with the Romanian data. Thus, only interest, social, economic and development are modelled in our work. Results additionally show the link between the modified employer attractiveness scale, and employee outcomes such as job satisfaction and the intent to apply for a job. Thus, the results confirm the importance of employer branding strategies in the form of employer attractiveness dimension enhancements for recruitment. The view that more research is needed to establish the antecedents of employer brands has been established (Rampl & Kenning, Citation2014), and whilst a framework has been developed identifying these factors (such as employer attractiveness) and their impact on company performance (Biswas & Suar, Citation2016), our research further expands knowledge on employer branding by showing that employer attractiveness is associated with positive work outcomes, such as job satisfaction.

Hence, we make several contributions. Firstly, we identify the employer branding dimensions that are relevant in Romania, expanding knowledge on employer attractiveness in a unique context that has a high unemployment rate (especially in the young), is characterised by ‘a brain drain phenomenon’ and has high staff mobility between sectors. Secondly, by validating the existing scale of employer attractiveness, we provide a refined measure that shows the application value is not relevant (methodological contribution). Prior studies on employer branding in Romania tend to only present descriptive statistics of large surveys, or are exploratory (based on secondary data, website analysis, or a few short interviews, see Balan, Citation2013; Turnea et al., Citation2020; Tőkés, Citation2020). Hence, our work paves the way towards a more sophisticated measurement that can be used in future studies. Thirdly, the insights generated are important for HR practitioners in an Eastern European country as they provide an appropriate tool for evaluating and designing employer branding strategies, especially the need to avoid emphasis on ‘application value’, which might otherwise be seen as an obvious differentiator (practical contribution). Finally, we show that the modified employer attractiveness scale predicts positive work outcomes such as job satisfaction.

The paper proceeds as follows. The first section outlines the theoretical underpinnings by reviewing the literature on employer branding. The variables used and the results are then explained. Finally, we end with discussion of findings, conclusions, and areas for further research.

Literature review

Employer branding

The scope and application of branding has increased over recent years to the point where branding may be viewed as a cultural phenomenon driven by the incongruities and synergies among managers, employees, consumers, and other stakeholders (Tanwar & Prasad, Citation2017). The increased relevance of employer branding, which essentially concerns the application of branding principles and practices in the area of human resources management (HRM) (Backhaus & Tikoo, Citation2004) is therefore logical. The important role of employees in brand identity has long been recognised (von Wallpach et al., Citation2017), but as employers increasingly treat human resources as a strategic issue (Michaels et al., Citation2001), the role of employer branding to attract and retain employees has grown (Berthon et al., Citation2005).

Employer branding is defined as ‘the package of functional, economic and psychological benefits provided by employment, and identified with the employing company’ (Ambler & Barrow, Citation1996, p. 187). According to Backhaus and Tikoo (Citation2004), employer branding refers to the unique and exclusive features of an employer and encompasses distinctive characteristics of the company’s employment offerings and/or environment that will differentiate it from competitors. These definitions allow for further inquiries as to whether companies could offer unique employment offerings in a market largely regulated and defined by legislation.

An employer brand is further conceptualised as a set of attributes and qualities (often intangible) that makes an organisation distinctive, promises a particular kind of employment experience, and appeals to those people who will thrive and perform best in its culture (CIPD, Citation2009). In other words, it represents the image and appropriate set of economic and non-material (psychological, symbolic) advantages distinguishing the company in the labour market. For Sullivan (Citation2004), employer branding is a strategy to manage stakeholders’ awareness, perceptions, opinions, and beliefs with regards to a particular organisation.

Martin et al. (Citation2011, p. 3618) also explain that a good employer brand should be known among key stakeholders for providing a ‘high quality employment experience’, and a ‘distinctive organisational identity’, which employees value, engage with and feel confident about, and are happy to promote to others. This means that employers need to create a high-quality employment experience, but the authors somewhat vaguely explain what the employment experience is and what high quality indicates, leaving the question around how this experience is created and associated benefits unanswered. As organisations include people working towards specific corporate goals in specific cultural environments, this experience is created differently in various socio-economic contexts, and it is highly dependent on the employees working in the company, its internal policies and culture.

Furthermore, in assessing employer branding, Moroko and Uncles (Citation2008) address the substructure of the psychological contract in the relationship between employee and employer. In their view, psychological contracts are individual beliefs regarding reciprocal obligations. Rousseau (Citation1990) argues that the relationship between employer and employee principles become contractual when the individual believes that he or she owes the employer certain contributions (i.e. work, commitment) in return for certain inducements (i.e. pay, job security). These reciprocal obligations are being formed during the recruitment process, and, as Moroko and Uncles (Citation2008) emphasise, can be based on explicit statements of the company alongside informal and imprecise information (i.e. from external recruiters, word-of mouth sources, press and popular media). Employees are therefore more likely to be committed to an organisation and satisfied with their job when the employer fulfils its requirement (Tanwar & Prasad, Citation2017), in other words, when they will psychologically accept the proposed employment offering. Robinson and Rousseau (Citation1994) note that when the psychological contract is broken, engagement and productivity may decline. Researchers suggest that if an employer fails to deliver its employer brand promise to new staff and acts in an inconsistent way in validating its employment decision, it is likely that the post-entry performance of employees will be negatively affected and staff turnover will increase (Backhaus & Tikoo, Citation2004) as the psychological contract is perceived to be violated or broken.

An empirical measurement tool for employer branding has been presented by Berthon et al. (Citation2005) and identifies five dimensions of employer attractiveness: interest, social, economic, development and application value. ‘Interest value’ refers to ‘the extent to which an individual is attracted to an employer that provides an exciting work environment, novel work practices and that makes use of its employee’s creativity to produce high-quality, innovative products and services’ (Berthon et al., Citation2005, p. 161). ‘Social value’ is ‘the extent to which an individual is attracted to an employer that provides a working environment that is fun, happy, provides good collegial relationships and a team atmosphere’ (Berthon et al., Citation2005, p. 161). However, the value of a ‘fun working environment’ varies with the cultural and economic context and therefore needs examining in the specific country context (Graham & Cascio, Citation2018).

‘Economic value’ measures ‘the extent to which an individual is attracted to an employer that provides above-average salary, compensation package, job security and promotional opportunities’ (Berthon et al., Citation2005, pp. 161–162). ‘Development value’ is ‘the extent to which an individual is attracted to an employer that provides recognition, self-worth and confidence, coupled with a career-enhancing experience and a springboard to future employment’ (Berthon et al., Citation2005, p. 162). Lastly, ‘Application value’ is ‘the extent to which an individual is attracted to an employer that provides an opportunity for the employee to apply what they have learned and to teach others, in an environment that is both customer orientated and humanitarian’ (Berthon et al., Citation2005, p. 162).

The above conceptualisations of employer branding and the associated dimensions presented by Berthon et al. (Citation2005) imply a set of often intangible attributes and qualities representing the image and appropriate set of economic and non-material advantages (psychological, or symbolic), distinguishing an employer in the labour market. However, such intangible attributes are subject to interpretations that may exhibit specificities in different countries.

The importance of employer branding

Over recent years employment levels have been high in many developed countries, and competition to recruit and retain skilled employees is likely to increase as many populations age (Wilden et al., Citation2010). Organisations therefore need to treat human resources as a key issue (Michaels et al., Citation2001) that is almost as critical as competition for customers (Berthon et al., Citation2005). As organisations want to be seen as attractive employers (Lievens & Highhouse, Citation2003), employer branding has become an important tool (Backhaus & Tikoo, Citation2004). This is a concept based on the assumption that human capital adds value to the organisation, and, through skilful investment in human capital, organisational performance can be enhanced (Backhaus & Tikoo, Citation2004).

The benefits of employer branding can be explained further through the selection-attraction-attrition model (ASA; Schneider, Citation1987). The ASA model is a person-based model of the organisation, linked to the individual (Ployhart et al., Citation2006) and predicts organisations’ strive towards homogeneity in knowledge, skills, abilities and other competencies through three interrelated processes: attraction, selection and attrition. In this paper, we focus on the attraction element. Attraction involves the fit between persons’ characteristics and an organisation’s characteristics (Ployhart et al., Citation2006). A key tenet of the ASA model is that individuals will be attracted to organisations characterised by values in congruence with their own values. This idea of value congruence is commonly captured through fit, i.e. person-organisation fit, person-environment fit, and person-job fit (Kristof‐Brown et al., Citation2005; Westerman & Cyr, Citation2004). The person-organisation fit should inform any employer branding strategy and employer brands therefore link to a key decision of how to operationalise the person organisation fit components (Cable and Judge, Citation1996). A critical use of employer branding thus will help to send signals to potential employees that enable them to assess their fit with the company (Westerman & Cyr, Citation2004).

Organisations with a positively perceived employer brand will attract more talented applicants (Cable & Turban, Citation2003; Turban & Greening, Citation1997) and can reduce recruitment costs by improving the recruitment performance (Knox & Freeman, Citation2006). Such positive perceptions of the employer brand also contribute to employee retention, reduce staff turnover (Berthon et al., Citation2005) and improve organisational culture (Backhaus & Tikoo, Citation2004). Moreover, employer brand is found to exert positive influences on applicant perceptions of recruiter behaviours (Turban et al., Citation1998) and it is a significant predictor of early decisions made by new recruits about their employers (Gatewood et al., Citation1993). Employer branding also builds trust in leadership and impacts individual, team, and organisational engagement (Gittell et al., Citation2010). Martin et al. (Citation2011) also argue that employer branding has the potential to help organisations become responsive and build social capital, thus contributing to the innovation agenda and transformative business model change. Grigore and Stancu (Citation2011) show the positive role that corporate social responsibility plays in employers’ brand.

Ultimately, the application of branding principles to human resources produces a system that invites managers to communicate internally in a way that permits employees to feel proud to work for a desirable and attractive employer.

Employer branding and organisational attractiveness

Conceptually, there have been differences between the constructs of employer image, employer brand and employer attractiveness. For example, Gatewood et al. (Citation1993) carefully distinguish between corporate image and recruiting image (which is a type of employer image). Also, Backhaus and Tikoo (Citation2004) carefully distinguish brand-associations, employer brand, and employer image. Furthermore, Cable and Turban (Citation2003) use the term ‘firm reputation’, that is more closely related to the corporate image (perceived by customers), rather the employer image (perceived by job seekers). Finally, Lievens and Highhouse (Citation2003) define the term ‘corporate employment image’ which, again, is a facet of the broader theoretical construct ‘corporate image’. Thus, there are some important variances between these theoretical constructs. In this section, we provide an overview of each concept.

Viewing employer branding as a manifestation of organisational identity, Albert and Whetten (Citation1985) express its central, enduring, and distinctive character, and suggest that it may help employees to identify themselves with the values of the employer. To support this, Backhaus and Tikoo (Citation2004) place employer branding within organisational identity, and they suggest the two concepts are complementary. In addition, Knox and Freeman (Citation2006) found a positive correlation between an attractive employer brand image and candidate’s likelihood to apply for jobs. If an organisation has a strong positive employer brand, it can increase its ability to not only attract, but also to retain and engage people (Ambler & Barrow, Citation1996; Backhaus & Tikoo, Citation2004).

The synthesis of conceptualisations of employer branding reveals the preoccupations on identifying factors, motives, and rationales that influence the attractiveness of an organisation to potential employees. Organisational attractiveness denotes ‘the envisioned benefits that a potential employee sees in working for a specific organization’ (Berthon et al., Citation2005, p. 156). Jiang et al. (Citation2011) also see it as a force that draws applicants’ attention to employer branding and encourages existing employees to stay loyal to a company.

For researchers considering organisational attractiveness and employer branding, organisational attractiveness is thought of as an antecedent of the more general concept of employer brand equity (Berthon et al., Citation2005). These views express a significant development in the way organisational attractiveness is understood, and recently, it has gained increasing interest from researchers in HRM and organisational behaviour (Lievens et al., Citation2007; Moroko & Uncles, Citation2009). As organisations seek to attract new employees and retain existing staff, employment branding grows in importance. Berthon et al. (Citation2005) note that this objective can be achieved effectively when organisations understand the factors underpinning employer attractiveness.

Organisational attractiveness is therefore regarded as a multi-dimensional construct. There are various attempts to identify the distinct dimensions of organisational attractiveness (Berthon et al., Citation2005; Sivertzen et al., Citation2013) in building employer branding. Aiming to bridge the research streams on organisational identity and employer branding, Lievens et al. (Citation2007) used the instrumental – symbolic framework to study factors relating to both employer image and organisational identity. Their findings support the idea that both instrumental (i.e. team/sports activities, structure, and job security) and symbolic (i.e. excitement, competence, and ruggedness) image dimensions predict applicants’ attraction to the organisation, whereas symbolic perceived identity dimensions best predict employees’ identification with the organisation. Jiang et al. (Citation2011) proposed that organisational attractiveness has two dimensions: internal attractiveness (for existing employees) and external attractiveness (for external applicants), and both dimensions should be measured separately, along with intentions to choose the workplace and intentions to stay in the workplace.

Applications of employer branding in Romania

Theory needs to recognise local context and possible variations in practice (Husain et al., Citation2023; Grigore et al., Citation2021a, Citation2021b). There are very few studies that specifically consider employer branding in Romania. For example, Turnea et al. (Citation2020) study the rewards that play a role in attracting young and talented employees. The authors discuss the high levels of unemployment and turnover in the Romanian workforce, particularly in the young segments. At the end of May 2020, the unemployment rate of the young Romanians was 17.6%, higher than the EU rate of 15.7%. Drawing on a survey with 245 masters and PhD students from Iasi city, their study shows that attractive employment offers include competitive salaries, learning and career development, or programme flexibility. Additionally, good social relationships and working environment contribute to the employees’ wellbeing. The study also reveals that the combination of a competitive salary and opportunities for personal development increases the companies’ abilities to recruit and retain talented young Romanians.

In another study, Tőkés (Citation2020) explores the software and IT companies in Romania (one of the fastest growing sectors in the country), which have a competitive advantage over employers from other sectors given their ability to offer significant financial and non-financial benefits. Drawing on a content analysis of 110 software and IT corporate websites (2018, Cluj-Napoca city), Tőkés argues that, due to the growing shortage of labour force and despite these attractive benefits, many IT companies are still struggling to attract and retain employees. The author shows how the large international IT companies operating in Romania have a complex employer brand identity used to attract workforce. On the other hand, medium or small (local) companies have more basic employer brand identity, merely formulated as answers to the request of the labour market, and so failing to attract staff via websites.

Finally, Balan (Citation2013) sets out to identify whether there is a generational difference in how employer brands are perceived, and to reveal the various attributes of employer brands. Considering the results of a large online survey with 8,762 respondents conducted by a consultancy, Balan notes that the most desired employers in Romania are IT companies, banks, and tax consulting/auditors. Romanians have a pragmatic approach when seeking employment, focusing on short-term and tangible rewards/benefits. For example, the highest criteria for selecting an employer are salary package (47.12%), corporate reputation (36.59%), training opportunities (36.33%), job security (35.86%) or good working environment (29.20%), whilst a creative and dynamic working environment, or the allocation of mentors for professional development matter less. In a Eurobarometer study (2013), the most attractive companies for business studies included 5 banks. Balan concludes that research on employer brands in Romania (other than descriptive statistics offered by consultancies), is scarce and calls for more research on employer brand differentiation that organisations can use to integrate in their strategies to attract talented employees.

Romania therefore provides a unique context, with a high unemployment rate (especially in young Romanians), characterised by ‘a brain drain phenomenon’, and with a high staff mobility. As noted above, prior studies on employer branding in Romania tend to only present descriptive statistics of large surveys, or is exploratory (based on secondary data, website analysis, or a few short interviews). As such, an application of a sophisticated scale in this context, expands employer branding knowledge and practice in Romania.

Research context: an overview of Romania

The Eastern European countries had similar conditions in terms of the performance of the labour market under communism (Savić & Zubović, Citation2015). These conditions were characterised by ‘shortage of labour, no open unemployment, very high level of unionisation, and no employment protection’ (Savić & Zubović, Citation2015). Since the fall of communism, these countries have worked towards political and economic integration with the ‘West’ and membership of the European Union (Grigore et al., Citation2021a; Stoian & Zaharia, Citation2012). Eastern European countries are still facing political and economic, as well as negative demographic changes, with an increase in ageing population, significant migration of working force, and with a higher education system that is perceived by employers as not compatible with the requirements of the labour market (Savić & Zubović, Citation2015). In many cases, multinational companies instilled their practices in the local subsidiaries, but this ‘adoption’ of practices took place in a system where the principles of socialist political economies were present within firms and their institutional fabric (Stoian and Zaharia, Citation2012), including high levels of corruption and fraud (European Commision, 2017). For example, using Bauman’s ethics (adiaphora and moral distancing) and Borţun’s view on Romanianness, Grigore et al. (Citation2021a) reveal the issue of corruption and individualism in Romanian corporate social responsibility practice. The authors note that managers paradoxically feel the ‘moral impulse to do good’ at the same time as exhibiting self-interest and careerism, which they feel are deeply rooted in the social and cultural context. This ambivalence then leads to unintended consequences in CSR practice, i.e. a potential for corruption and ‘collateral beneficiaries’, or those vulnerable groups in society that are supported through short-term, promotional CSR activities. Their study, although not on employer branding, reveals that Romanians prefer money, or financial packages to working conditions. Stoian and Zaharia (Citation2015) and Grigore et al. (Citation2021a) and Ahmad et al. (Citation2012) call for more research into the various business practices in this unique context.

The Romanian labour market has changed in the last few years. The number of graduates who get employment has decreased more than 50% compared to 2008, and the brain drain phenomenon continues to grow. Employers want to attract talented employees, and to keep employees motivated and they also recognise the importance and impact of strong employer brands, and as such have started investing in developing these (Hipo, Citation2015). A study by Manpower Group (Citation2015) on ‘talent deficit’ shows that organisations in Romania are struggling to attract suitable employees for available jobs. In this respect, Romania is in the top five countries in the world and the first one in Europe in terms of talent deficit (Manpower Group, Citation2015). Employees further predict that this trend will be growing in the following years, which leads to reduced organisational competitiveness and productivity, personnel fluctuations, and a decline in organisational innovation and creativity (Manpower Group, Citation2015).

We chose ING bank for our analysis as it represents a typical example of a multinational company that instilled subsidiaries in several post-communist (transition) countries (including Romania, Bulgaria, Cehia, Slovakia, and Hungary), to acquire legitimacy by introducing responsible behaviour towards employees – a key internal stakeholder whose rights are important in maintaining the integrity and long-term financial and societal performance of firms. Dow Jones Sustainability Index named ING among world leaders in the category ‘Banks’ (ING, Citation2016). The bank also has a well-known brand, with positive recognition from customers and other stakeholders in a variety of countries (ING, Citation2016).

Method

We investigate the applicability of the EmpAt scale in Romania. Hence, we did not develop a priori hypotheses. It was not pragmatic to start the process with a qualitative pre-study which is sometimes recommended in full scale development papers (Hinkin, Citation1998). Rather, we examine the structure and dimensionality of the existing EmpAt scale and probe the relationship between employer attractiveness and intention to seek employment with the company. This approach enables us to investigate to what extent the psychometric properties of the existing scale hold in the Romanian context.

Participants and procedure

The online survey was conducted in May 2015 with the aim of identifying the key dimensions of employer attractiveness for a bank in Romania. Additionally, the sample is suitable to investigate the effect of employer attractiveness on the intention to seek employment with a bank. Respondents rated their perception of employer attractiveness for one multinational bank. Excluding the incomplete answers, the final sample included 310 participants with and average age of 40.8, including 162 females and 148 males, 214 employed and 96 unemployed. This sample is particularly suitable because employed respondents are invited to think about an alternative employer, and unemployed respondents would naturally evaluate whether the chosen bank would be an attractive employer for them. displays descriptive statistics.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations.

Measures

If not indicated otherwise, all constructs were measured using seven-point Likert scales (1=strongly disagree, 7=strongly agree). Our research objective centres on identifying the key dimensions of attractiveness in employer attractiveness in Romania. Furthermore, the study identifies the effect of employer attractiveness on the intention to seek employment. To achieve this, we applied the 25-item employer attractiveness scale (EmpAt) developed and validated by Berthon et al. (Citation2005) in the US (see above). Items were adapted such that they referred to our chosen bank specifically.

Four additional constructs were included. First, we used two items to measure participants’ intention to seek employment with the bank (‘I would love to work for this company’, ‘I would be proud to work for this company’). This measure yields a Cronbach alpha of 0.95. Second, we used three global measures of frequently assessed employee attitudes. These are the likelihood of job satisfaction (‘If I worked for this company, I would be satisfied with my job’), commitment (‘If I worked for this company, I would be highly committed to my job’), and intention to quit (‘If I worked for this company, I would never think to quit’). Such global single item measures have been shown to perform adequately well when compared to multi-item measures, especially with respect to job satisfaction (Wanous et al., Citation1997). The intention to seek employment with a company scale was developed based on Sen et al. (Citation2006), and the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (Porter et al., Citation1974), and was previously employed in other studies (Alniacik et al., Citation2011).

Control variables

We used a standard set of control variables. Respondents were asked to indicate their age and gender. Additionally, respondents indicated their marital status (married, divorced, not married, widowed), and their highest level of education (doctorate, university, high school, post-high school, and professional school). Finally, we controlled for whether respondents were employed or on.

As a further check, the questionnaire asked the respondents whether they know this bank, or whether they own an account or a loan with this bank. Indeed, the results demonstrate that all respondents know this bank, and 30% of the sample own either an account, or a loan with the bank. This bank was selected as it has the best reputation as employer in banking sector in Romania, and the bank has recently received international recognition for best management of employer brand and its internal communication.

Potential for common method bias and countermeasures

Our data is cross-sectional, and thus results point towards associations and not causal effects. However, our primary aim was to model employer attractiveness in the East European context for which the cross-sectional data is suitable. The cross-sectional nature of the data further gives potentially rise to common method bias. The issue of common method bias is debated, with some considering concerns related to it as being exaggerated (Spector, Citation2006). Nonetheless, we thought it would be advisable to take some countermeasures. Following recommendations by Podsakoff et al. (Citation2012), and Conway and Lance (Citation2010), we used trustworthy items and made sure that items of related constructs appear in different parts of the survey. We benefitted from online survey tool use during data collection, which allowed for some item sets to be randomized. We also ran a Harman’s single factor test on the variables included in the regression models. Results do not support the existence of common method bias as the largest amount of variance a single factor explains is approximately 17%.

Keeping the shortcomings of such a posthoc-statistical test in mind, we want to point to some recent methodological studies highlighting effects that limit the influence of common method bias. For example, Lance and Siminovsky (Citation2015) point out the opposite effects of common method bias and measurement error. While the former inflates relations between variables the latter deflates them and thus the two effects offset each other. Furthermore, after running several simulations, Siemsen et al. (Citation2010, p. 472) conclude that common method bias is ‘less of a problem in OLS models with many independent variables, especially if these are not highly correlated’. With very few exceptions the variables in our data display rather small correlations. Correlations of our main variable employer attraction with other independent variables are low (the highest being high school degree with r = 0.15). Hence, we conclude that the combination of precautionary measures at the design stage, in combination with statistical tests and consideration of recent method studies offered an acceptable level of protection, and thus common method bias is of no concern.

Analysis and results

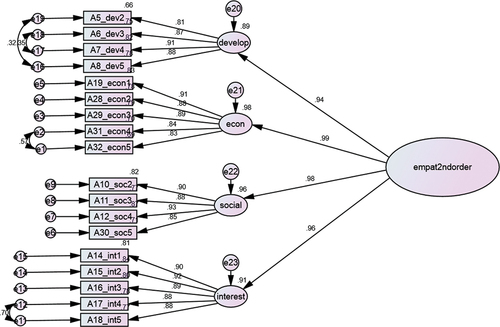

In a first step, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis modelling employer attractiveness as a second order factor. Results are displayed in . To fit the model, we had to eliminate one item from the development value subscale and one item from the social value subscale. As such, the ‘development’ and ‘social’ value measures work in our Romanian sample with minor modifications (the item ‘fun at the workplace’ is dropped from the social dimension, and ‘perceived recognition’ is dropped from the development dimension). Additionally, the application value had to be removed completely. We made this decision as the analyses revealed high levels of collinearity of the application value dimension, which impacted negatively of the fit values of the overall mode. Thus, the final employer attractiveness second-order construct consists of four dimensions (i.e. development value, social value, economic value, and interest value).

Overall, the factor loadings are above 0.8 throughout and the model displays satisfactory fit levels (CFI=.929, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .035, TLI = .915). Reliabilities (Cronbach’s alpha) for the subscales were 0.93 for development value, 0.94 for economic value, 0.93 for social value and 0.95 for interest value.

In a second step, we used OLS regressions to investigate the relation between employer attractiveness and the intention to seek employment and job satisfaction. The rationale for this analysis is that the revised scale of employer attractiveness should be able to predict both job satisfaction and employment intention in the Romanian context. The estimation strategy is as follows. We present two models for each dependent variable. The first estimates the model using the full set of control variables, and the second adds our main variable employer attractiveness.

The results displayed in show significant associations between employer attractiveness and job satisfaction, and the intent to seek employment with the bank. It is also noteworthy that models 1 and 3 only using the control variables fail the F-test rendering those models meaningless. However, once employer attractiveness joins the set of predictors the models show good fit and predictive capabilities. Of the control variables it is noteworthy that only age and marital status (divorced) display significant associations with the intent to apply, but are insignificant with respect to job satisfaction. We also ran robustness checks on the subsample of unemployed respondents. Results do not change materially and thus for reasons of space are not displayed here. Hence, overall, we conclude that employer attractiveness in Romania can be effectively modelled using our revised Berthon et al. (Citation2005) scale.

Table 2. Regression of employer attraction on job satisfaction and intent to apply.

Discussion

Our aim was to identify the key dimensions of employer attractiveness for a bank in Romania This study therefore adapts Berthon et al. (Citation2005) employer attraction measure to an East European context, i.e. Romania. Results show that the construct can be measured with modifications of the original scale. The ‘application value’ dimension is revealed not to matter in this context. We unpack these results and the implications for managers below.

Our findings show that the ‘economic value’ is particularly important to respondents. One explanation is that Romanians have been deprived of wealth, and see obtaining an above-average salary, a good compensation package, or job security as benefits of internationalisation. After all, EU membership and then the entry of international corporations (such as ING, the bank in this study) promised such economic benefits. This result is consistent with previous employer branding studies in Romania (Turnea et al., Citation2020; Tőkés, Citation2020) and with Balan’s (Citation2013) observation that Romanians have a pragmatic approach when seeking employment, focusing on short-term and tangible financial benefits. Secondly, the ‘interest value’, which places value on an exciting work environment, novel work practices, creativity to produce high-quality products, is relevant. This distances Romanians from the past where they had few career opportunities and rather bureaucratic jobs with little space for innovation and autonomy. Such desire for an ‘exciting work environment’ might be stronger in the younger Romanians who wish to distance themselves from the bureaucratic organisations of the past.

The ‘social value’ is significant as Romanians like fun, they are social, and this is the more enduring aspect of collectivism in Romanian culture. Indeed, a recent study conducted by Balan (Citation2013) shows that amongst the most significant factors in choosing an employer is a pleasant, friendly, fun working environment (55% out of 14.691 respondents with business, social sciences, engineering, and IT expertise). This is important as implementing ‘fun’ is discretionary and could differentiate employers that might otherwise be perceived as similar to help retain talent (Tews et al., Citation2021). As the Romanian job market evolves to reflect the culture, differentiation is likely to become important, so this is essentially ‘future proofing’ in the Romanian context. In short, ‘fun’ may help to create a unique and favourable employer brand, and organizations need to understand cultures so they can position their employer brands according to the needs and priorities of the people in them (Graham & Cascio, Citation2018).

Finally, the last relevant dimension is ‘development dimension’ and is again seen in the new individualism that emerged after communist (see Grigore et al., Citation2021a), or the outward looking optimistic Romanian mentality that values recognition, self-worth, confidence, and career enhancement. These dimensions were validated in other employer branding studies (including in the West), but what is interesting to note in our study, is this new individualism that distances younger Romanians from their past (where lives were organised by the state) and introduces them into capitalist structures.

The ‘application value’, which measures the ‘extent to which an individual is attracted to an employer that provides an opportunity for the employee to apply what they have learned and to teach others, in an environment that is both customer orientated and humanitarian’ (Berthon et al., Citation2005), does not seem to matter to Romanian employees. This is a significant difference when compared to other countries where the scale was applied. The explanation lies in various aspects of the national and business culture. For instance, the humanitarian aspect and ‘giving back’ to society is not prominent in post-communist economies (Grigore et al., Citation2021a; Stoian & Zaharia, Citation2012). Individuals were used to shortage and scarcity during communism under state control, and hence they feel a need to compensate for the lack through acquiring for themselves (Stoian & Zaharia, Citation2012). For example, Grigore et al. (Citation2021a) note this new form of individualism, where managers want to progress their careers, and are interested in obtaining good salaries, but they are also gregarious and want to have fun with others. This is important as a fun working environment can be a powerful differentiator. ‘Fun’ has been argued to have a positive impact on recruiting Millennials (Tews et al., Citation2012) and for increasing on-the-job informal learning. This indirectly reduces turnover through increased affective organizational commitment (Tews et al., Citation2017). Moreover, the slow development of HRM principles in the Eastern Europe indicates a limitation of the ‘internal customer’ concept, suggesting that employees lack awareness of it, and they experience low levels of engagement, trust, and commitment in the companies where the authoritative managerial styles are ‘normalised’ or ‘preferred’ (Boia, Citation2013).

The findings can also be considered in terms of contrasts with the context of the original Berthon et al. (Citation2005) study where employment levels and overall standard of living were often high, making economic benefits less of a priority because they are assumed, or guaranteed. Or to put it another way, other employer branding dimensions can be considered only when pay is high, and we see that this is the case in Western countries. This was not the case in Romania, and this underpins a more functional, pragmatic attitude to employment where economic value is key. When work is precarious and pay seen as low, then economic dimension is a priority. As the Romanian economy and associated jobs market become more developed, it seems likely that other values such as social and development (and even the currently less important application value) may develop greater significance. This is an interesting proposition for future benchmarking research.

Our analyses further provide evidence for the modified scale to predict job satisfaction and intent to apply. These results are in line with previous research on employer branding and attraction (Cable & Turban, Citation2003), and underscore the value of employer branding as an approach that generates desirable employee attitudes and candidate behaviours (Gittell et al., Citation2010). Therefore, we support the strategic role ascribed to employer branding techniques and its relevance for HRM practices, in particular recruitment. Overall, the set of features of the employing company reflected in the modified employer attraction scale makes it attractive to current or prospective employees and intermediaries in the labour market, such as recruiting firms, government employment bodies, and representatives of the professional HR community (Kucherov et al., Citation2012).

However, our results also reveal those specific aspects of employer branding that will produce a successful attraction campaign in Romania (‘economic’, ‘interest’, ‘social’ and ‘development’ value), and which dimensions should be ignored (‘application value’) in communications to potential candidates. As Balan (Citation2013) notes, knowing which criteria is most important for potential employees offers very useful input in the employer differentiation process. Aspects such as ‘giving back to society’, or ‘an opportunity to teach others what you have learnt, or apply that at a tertiary institution’ (higher education is seen not to provide useful work skills, so there is little potential for application, see above), or ‘working for a customer-orientated organisation’ related to an employer branding that are proved to be effective in Western contexts, might in fact alienate potential candidates, and detract them from applying for a job promoted in this way. Savuica (2019), for example, shows that young employees do not consider the area they have studied when choosing a job, but rather the salary received. On the other side, employers tend to ignore the academic area of specialisation of potential employees in favour of their work experience, previous training, and extracurricular activities. All these characteristics are unique to our context. Therefore, our study has implications for HRM or marketing managers working in Romania as they provide an appropriate and sophisticated tool for evaluating and designing employer branding strategies, by drawing on these dimensions valued by potential candidates.

This further suggests that employer branding – like any branding – strategies must adapt to local cultural specificities. Indeed, Maxwell and Knox (Citation2009) suggest that conceptualisations of employer branding that only focus on attributes related to employment are overly restrictive. The authors found that employees considered their organisation’s employer brand to be more attractive when the organisation was perceived to be successful, when they valued the attributes of the organisation’s product or service, and when they construed its external image as being attractive. Many of the latter aspects, Maxwell and Knox (Citation2009) suggest, are culturally biased. Our results indeed respond to calls for the cultural sensitivity of employer branding activities (Sivertzen et al., Citation2013). The evidence provided here shows positive associations between employer attractiveness and the likelihood of job satisfaction. This finding highlights the internal side effects strong employer branding activities may be able to generate. Hence, our findings are also in line with research by Backhaus and Tikoo (Citation2004) and Martin et al. (Citation2011).

Future research direction might also consider studies with highly knowledgeable employees at different stages in their career (junior or senior practitioners) to better understand how they perceive their work and the employer brand. Depending upon career stage this work would link to extant attraction-selection attribution/person-organisation fit theory, but would need to address the potential paradox that if being a ‘strong’ employer brand involves attracting and retaining the most talented employees within the organisation (and all such employees are potentially highly skilled and knowledgeable), who will undertake more mundane jobs? Similarly, loss of such talented employees may influence the employer brand that may be explored, and this could be the objective of future research. By drawing on an existing measure we may have overlooked other cultural aspects that may enrich the conceptual domain of employer attractiveness. Future research can therefore focus on qualitive, depth interviews with employers, and/or employees that could then lead to new employer branding dimensions.

Conclusion

This work has highlighted the importance of employer branding, through validating the existing scale of employer attractiveness and providing further evidence of its strategic value in optimising human resource management performance. We also empirically show that the modified employer attractiveness scale has a potential to predict important positive work outcomes, such as job satisfaction. However, this study is undertaken in Romania, and therefore results in a modified version scale of value to academics, as well as human resources or marketing managers, as they provide an appropriate tool for evaluating and designing employer branding strategies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Georgiana Grigore

Georgiana Grigore is Associate Professor in Marketing. Georgiana’s research has focused on the intersections between corporate social responsibility and marketing, including changes that result from digital media. She has also examined the experiences of those working in responsibility roles in different European cultures, noting how their lived experiences impact on how corporate social responsibility gets done.

Chris Chapleo

Chris Chapleo is Professor of Societal Marketing at Bournemouth University. He has published widely in international journals on marketing and branding, particularly on non-profit organisations and the education sector. He has also presented key notes and conference papers at many conferences, and has combined this with consultancy and enterprise work for leading organisations. His current work concerns consumer behaviour around choices in health and green behaviours.

Fabian Homberg

Fabian Homberg is Full Professor of Human Resource Management and Organisational Behaviour at LUISS University, Department of Business and Management. His current research interests are public service motivation, sector attraction and incentives in private and public sector organizations. He is associate editor of Evidence-based HRM, and the Review of Managerial Science. He is Editorial Board Member of the Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory and Human Relations.

Umit Alniacik

Umit Alniacik is Professor of Marketing in the Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences, Kocaeli University. He obtained his Ph.D. in Business Administration from Gebze Institute of Technology. His research areas include: marketing, management of enterprises, strategic marketing and brand management.

Alin Stancu

Alin Stancu is Professor of Corporate Social Responsibility and Public Relations in the Department of Marketing from The Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Romania. His main areas of research include: customer care, corporate responsibility and public relations. He is the co-founder of The International Conference on Social Responsibility, Ethics and Sustainable Business (www.csrconferences.org) and co-editor of the book series: Palgrave Studies in Governance, Leadership and Responsibility.

References

- Ahmad, J., Ali, I., Grigore, G. F., & Stancu, A. (2012). Studying Consumers' Ecological Consciousness–A Comparative Analysis of Romania, Malaysia and Pakistan. Amfiteatru Economic Journal, 14(31), 84–98.

- Albert, S., & Whetten, D. A. (1985). Organizational identity. In L. L. Cummings & B. M. Staw (Eds.), Research in organizational behavior (pp. 263–295). JAI Press.

- Alniacik, U., Alniacik, E., & Genc, N. (2011). How corporate social responsibility information influences stakeholders’ intentions. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 18(4), 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.245

- Ambler, T., & Barrow, S. (1996). The employer brand. Journal of Brand Management, 4(3), 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.1996.42

- Backhaus, K., & Tikoo, S. (2004). Conceptualizing and researching employer branding. Career Development International, 9(5), 501–517. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430410550754

- Balan, C. (2013), A marketing perspective of the employer brand in Romania, In International conference of the institute for business administration, Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania, 41–49.

- Berthon, P., Ewing, M., & Hah, L. L. (2005). Captivating company: Dimensions of attractiveness in employer branding. International Journal of Advertising, 24(2), 151–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2005.11072912

- Biswas, M., & Suar, D. (2016). Antecedents and consequences of employer branding. Journal of Business Ethics, 136(1), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2502-3

- Boia, L. (2013). Mitul democrației. Humanitas.

- Cable, D. M., & Judge, T. A. (1996). Person–organization fit, job choice decisions, and organizational entry. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 67(3), 294–311.

- Cable, D. M., & Turban, D. B. (2003). The value of organizational image in the recruitment context: A brand equity perspective. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33(11), 2244–2266. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01883.x

- CIPD. (2009), Employer branding: maintaining the momentum, Hot Topics Report, Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development.

- Conway, J. M., & Lance, C. E. (2010). What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(3), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9181-6

- Gatewood, R. D., Gowan, M. A., & Lautenschlager, G. J. (1993). Corporate image, recruitment image and initial job choice decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 36(2), 414–427. https://doi.org/10.2307/256530

- Gittell, J. H., Seidner, R., & Wimbush, J. (2010). A relational model of how high-performance work systems work. Organization Science, 21(2), 490–506. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0446

- Graham, B. Z., & Cascio, W. F. (2018). The employer-branding journey: Its relationship with cross-cultural branding, brand reputation, and brand repair. Management Research: Journal of the Iberoamerican Academy of Management, 16(4), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRJIAM-09-2017-0779

- Grigore, G., Molesworth, M., Vontea, A., Basnawi, A. H., Celep, O., & Jesudoss, S. P. (2021a). Corporate social responsibility in liquid times: The case of Romania. Journal of Business Ethics, 174(4), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04926-w

- Grigore, G., Molesworth, M., Vonțea, A., Basnawi, A. H., Celep, O., & Jesudoss, S. P. (2021b). Drama and discounting in the relational dynamics of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 174, 65–88.

- Grigore, G. F., & Stancu, A. (2011). THE ROLE OF CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY IN BUILDING EMPLOYER'S BRAND. Transformations in Business & Economics, 10.

- Hinkin, T. R. (1998). A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organizational Research Methods, 1(1), 104–121.

- HIPO. (2015), “Topul celor mai doriti angajatori in 2015”, available at: http://www.hipo.ro/locuri-de-munca/vizualizareArticol/1682/Topul-celor-mai-doriti-angajatori-in-2015 (Retrieved September 1, 2017).

- Husain, S., Molesworth, M., & Grigore, G. (2023). Expanding knowledge of institutional complexity through the hyphen-spaces opened up by participant videography. Journal of Marketing Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2023.2241474

- ING. (2016), ING group annual report 2016, Retrieved September 1, 2017 from. https://www.ingbank.pl/_fileserver/item/1117155

- Jiang, T., Iles, P., & Lu, L. (2011). Employer-brand equity, organizational attractiveness and talent management in the Zhejiang private sector, China. Journal of Technology Management in China, 6(1), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1108/17468771111105686

- Knox, S., & Freeman, C. (2006). Measuring and managing employer brand image in the service industry. Journal of Marketing Management, 22(7–8), 695–716. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725706778612103

- Kristof‐Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(2), 281–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2005.00672.x

- Kucherov, D., Zavyalova, E., & Garavan, T. N. (2012). HRD practices and talent management in the companies with the employer brand. European Journal of Training & Development, 36(1), 86–104. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090591211192647

- Lance, C. E., & Siminovsky, A. B. (2015). Use of “independent” measures does not solve the shared method bias problem. In More statistical and methodological myths and urban legends (pp. 276–291). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203775851

- Lievens, F., & Highhouse, S. (2003). The relation of instrumental and symbolic attributes to a company’s attractiveness as an employer. Personnel Psychology, 56(1), 75–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00144.x

- Lievens, F., Van Hoye, G., & Anseel, F. (2007). Organizational identity and employer image: Towards a unifying framework. British Journal of Management, 18(1), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2007.00525.x

- Manpower Group. (2015), Talent deficit, Manpower Group, Retrieved September 1, 2017. https://candidate.manpower.com/wps/wcm/connect/308df630-4cc4-46f8-bcd8-91c1643c006b/2015+Studiul+privind+deficitul+de+talente±+Global+EMEA+Romania.pdf?MOD=AJPERES

- Martin, G., Gollan, P. J., & Grigg, K. (2011). Is there a bigger and better future for employer branding? Facing up to innovation, corporate reputations and wicked problems in SHRM. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 22(17), 3618–3637. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.560880

- Maxwell, R., & Knox, S. (2009). Motivating employees to” live the brand“: A comparative case study of employer brand attractiveness within the firm. Journal of Marketing Management, 25(9–10), 893–907. https://doi.org/10.1362/026725709X479282

- Michaels, E., Handfiels-Jones, H., & Axelrod, B. (2001). The War for Talents. Harvard Business School Press.

- Moroko, L., & Uncles, M. D. (2008). Characteristics of successful employer brands. Journal of Brand Management, 16, 160–175.

- Moroko, L., & Uncles, M. D. (2009). Employer branding and market segmentation. Journal of Brand Management, 17(3), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2009.10

- Ployhart, R. E., Weekley, J. A., & Baughman, K. (2006). The structure and function of human capital emergence: A multilevel examination of the attraction-selection-attrition model. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 661–677. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.22083023

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Porter, L. W., Steers, R. M., Mowday, R. T., & Boulian, P. V. (1974). Organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and turnover among psychiatric technicians. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59(5), 603. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0037335

- Rampl, V. L., & Kenning, P. (2014). Employer brand trust and affect: Linking brand personality to employer brand attractiveness. European Journal of Marketing, 48(1/2), 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-02-2012-0113

- Robinson, S. L., & Rousseau, D. M. (1994). Violating the psychological contract: Not the exception but the norm. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(3), 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030150306

- Rousseau, D. M. (1990). New hire perceptions of their own and their employer’s obligations: A study of psychological contracts. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 11(5), 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030110506

- Savić, M., & Zubović, J. (2015). Comparative analysis of labour markets in South East Europe. Procedia Economics and Finance, 22, 388–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00309-3

- Schneider, B. (1987). The people make the place. Personnel Psychology, 40(3), 437–453.

- Sen, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Korschun, D. (2006). The role of corporate social responsibility in strengthening multiple stakeholder relationships: A field experiment. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 158–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070305284978

- Siemsen, E., Roth, A., & Oliveira, P. (2010). Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 456–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428109351241

- Sivertzen, A. M., Nilsen, E. R., Olafsen, A. H., Roper, S., & Vacas de Ca, L., (2013). Employer branding: Employer attractiveness and the use of social media. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 22(7), 473–483. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-09-2013-0393

- Spector, P. E. (2006). Method variance in organizational research: Truth or urban legend? Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105284955

- Stoian, C., & Zaharia, R. M. (2012). CSR development in post‐communist economies: Employees’ expectations regarding corporate socially responsible behaviour–the case of Romania. Business Ethics: A European Review, 21(4), 380–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12000

- Sullivan, J. (2004). Eight elements of a successful employment brand. ER Daily, 23(2), 501–517.

- Tanwar, K., & Prasad, A. (2017). Employer brand scale development and validation: A second-order factor approach. Personnel Review, 46(2), 389–409. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-03-2015-0065

- Tews, M. J., Jolly, P. M., & Stafford, K. (2021). Fun in the workplace and employee turnover: Is less managed fun better? Employee Relations: The International Journal, 43(5), 979–995. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-02-2020-0059

- Tews, M. J., Michel, J. W., & Bartlett, A. (2012). The fundamental role of workplace fun in applicant attraction. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 19(1), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051811431828

- Tews, M. J., Michel, J. W., & Noe, R. A. (2017). Does fun promote learning? The relationship between fun in the workplace and informal learning. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 98, 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.09.006

- Tőkés, G. E. (2020). Employer brand and identity of software and IT Companies from CLUJ-NAPOCA as reflected in their website content. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Braşov, Series VII: Social Sciences and Law, 13(1), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.31926/but.ssl.2020.13.62.3.19

- Turban, D. B., Forret, M. L., & Hendrickson, C. L. (1998). Applicant attraction to firms: Influences of organization reputation, job and organizational attributes, and recruiter behaviors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 52(1), 24–44. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1996.1555

- Turban, D. B., & Greening, D. W. (1997). Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Academy of Management Journal, 40(3), 658–672. https://doi.org/10.2307/257057

- Turnea, E.-S., Prodan, A., Boldureanu, G., Ciulu, R., Arustei, C. C., & Boldureanu, D. (2020). The Importance of Organizational Rewards on Attracting and Retaining Students at Work. Transformations in Business & Economics, 19(2B (50B)), 42–59.

- von Wallpach, S., Voyer, B., Kastanakis, M., & Mühlbacher, H. (2017). Co-creating stakeholder and brand identities: Introduction to the special section. Journal of Business Research, 70, 395–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.08.028

- Wanous, J. P., Reichers, A. E., & Hudy, M. J. (1997). Overall Job Satisfaction: How good are single-item measures? Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(2), 247–252. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.2.247

- Westerman, J. W., & Cyr, L. A. (2004). An integrative analysis of person–organization fit theories. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 12(3), 252–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0965-075X.2004.279_1.x

- Wilden, R., Gudergan, S., & Lings, I. (2010). Employer branding: Strategic implications for staff recruitment. Journal of Marketing Management, 26(1–2), 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/02672570903577091