ABSTRACT

In contemporary planning, the development of soft regions through inter-municipal collaborations plays an increasingly important role. However, as previous research has shown, local borders and local jurisdiction are likely to remain as part and parcel of the new region. This paper argues the need to consider the geography of such local borders, to reveal asymmetries which could weaken the opportunities for inter-municipal collaboration. Following relational geography, we argue that the municipalities don’t necessarily share the same border; if understood as a relational effect, the border plays different roles for each municipality. With this in mind, we offer a case study of how a Swedish local border is being negotiated within planning. The case of Kumla and Hallsberg reveals how one municipality is active in trying to negotiate the border, whereas the other procrastinates around any action which do not lie in their interest. The result is a border haunted by decades of poorly coordinated, even provocative, planning actions. Our study opens up for a discussion on asymmetries and a relational understanding of the geography (and history) of planning, as well as for further studies of the interplay between the renegotiation of the local borders within emerging soft regions.

Introduction

Over the past decades, research on soft regions has made important contributions to an understanding of the new geography of planning (Healey Citation2007; Allmendinger and Haughton Citation2009; Haughton et al. Citation2010; Heley Citation2013; Paasi and Zimmerbauer Citation2016; Zimmerbauer and Paasi Citation2020). This research pays attention to how soft spaces and fuzzy boundaries have emerged within spatial planning, as a response to new needs in a world of increased mobility, new challenges in providing infrastructures and social services, neoliberal approaches in planning and increased attention to network governance. Yet, as Zimmerbauer and Paasi (Citation2020) illustrate, territorial thinking and local borders linger within this new geography. This is especially apparent in land-use planning, as it grapples with the terrain, the domain structure, shadows of past planning, and the boundaries of its jurisdiction. This is where the suboptimal structure of the ‘old’ geography comes to the fore when various actors (from politicians to business executives) start to think in terms of a soft region. At least some functions of the local borders need to be renegotiated to make it possible for a soft region to be successful (Zimmerbauer and Paasi Citation2020). This paper calls for detailed studies of the geography of such local borders, to better understand the potentials for inter-municipal collaborations concerning land-use planning, as part of the development of soft regions.

Despite its importance, this messy geography and the slow process of renegotiations of old borders seems to have been largely overlooked in research on soft regions. In addition, planning-related cases of local borders are almost absent in border studies (Haselsberger Citation2014; though see Ruming and Houston Citation2013 and Steele, Alizadeh, and Eslami-Andargoli Citation2013).

One reason for this could be found in the particular kind of relational geography which has informed the main strand of these research fields. In conceptualizing the soft region, relationality has played a key role, stressing the heterogeneous constitution of the region, its performative character and multiple and networked geography. In such descriptions, emphasis is usually put on its fleeting, open or network character. The same language is found in the parallel development of border studies into an interdisciplinary field studying the ever ongoing processes of bordering, in which studies of the border as such are decentred in favour of examinations of multiple processes of boundary-making (see e.g. Brambilla Citation2015 or Newman Citation2006 for an overview). As Lehtinen (Citation2011) notes, in the new spatial vocabulary of an (immanent) relational geography, flows, fluidity, emergence and mobility have gained ontological status. Malpas (Citation2012, 229) describes this strand of relational geography as being characterized by ‘a heady swirl of spatial trajectories and flows, in which boundaries, if they remain at all, take on highly uncertain status’. Thrift illustrates this fluid geography when he proclaims that ‘every space is in constant motion. There is no static and stabilized space’ (Citation2006, 141). Symptomatically, this also comes with a statement that boundaries are out of date: ‘there is no such thing as a boundary. All spaces are porous to a greater or lesser degree.’ Consequently, Zimmerbauer & Paasi (Citation2020, 2) note that the research discourse ‘has given rise to a somewhat biased understanding that contemporary planning is about making new “flexible” spaces that undermine established territorially bounded spatial entities’. For Paasi and his colleagues, this has led to a call for a combination of a relational and territorial understanding of the region and its boundaries (e.g. Paasi and Zimmerbauer Citation2016). By doing so, they provide a base for empirical studies which acknowledge the importance of everything from concrete borders to fleeting and elusive relations beyond the territory, in line with what Brenner, Madden, and Wachsmuth (Citation2011) refer to as an empirical approach to relational theories. While such an approach is not unusual in contemporary planning studies it nevertheless comes at a high price; as their studies of topography and relationality are based on separate ontological assumptions, there is no theoretical base for examining the interplay between the topography of the border and the emerging soft region.

We argue for the need to interpret the topography, materiality and history with the same lens of relational geography as the soft region in order to understand the role of the local borders. This is not a foreign approach in border studies: there are plenty of general discussions on borders and bordering which do mention these dimensions of the phenomena (see e.g. Ruming and Houston Citation2013; Steele, Alizadeh, and Eslami-Andargoli Citation2013; Haselsberger Citation2014; Scott and Sohn Citation2019), but with a ‘processual ontology’ (Brambilla Citation2015) in focus, there is nevertheless always a risk of their roles being undervalued. Therefore, another set of literature can be helpful to centre these aspects which we argue are of key importance for land-use planning. Several ANT-inspired studies provide useful inspiration, as their material semantics open up for studies of the heterogeneous networking which characterizes the planning process and its places (Murdoch Citation2006). For this study, we find inspiration in Metzger’s ‘radical relational-materialist’ approach in his study of emerging soft regions (Citation2013), Hommel’s examination of the complexity of obduracy (Citation2008), Beauregard’s elaborations on the role of matter and place in planning (Citation2015) and discussions on maintenance and repair (Graham and Thrift Citation2007; Qviström Citation2018). These studies reveal the historical particularity and materiality of place, or of place as an effect of ongoing and sedimented processes, processes which cannot be reduced to a matter of verbal pronouncements. As Beauregard (Citation2015, 92) notes,

Places emerge as heterogeneous assemblages of humans and nonhuman things come together (Law Citation2002), much as a potential landfill site identified through map overlays becomes more and more real as tests and studies are done, the owner of the property is approached, the state environmental protection agency is notified, and the site is publicly discussed. (see also Metzger Citation2013)

Such a place-based approach opens up for examinations of the role of the geography of planning, taking into consideration how the places are enacted in planning (as being, for instance ‘close’ and ‘hot’, or ‘marginal’ and ‘problematic’) or of how the history of previous conflicts and actors is still present and shapes the understanding of possible futures (Bickerstaff Citation2012). It brings to the fore the slow process of developing a place for a certain development by dismantling previous networks and by entangling it to new actors and other places (Qviström Citation2018).

By following the course of events we can trace the border as an effect of heterogeneous networking (Murdoch Citation2006). Importantly, while two municipalities share a border, they will enact it in different ways (cf. Rumford Citation2012 for a related discussion within border studies). This goes for the region and the state too, who will conceptualize the inter-municipal border in question in yet other ways (compare Valverde Citation2009 on scales). To question a local border is not simply to call for a ‘wider perspective’ (the region instead of the local level), but ultimately for another cause. Thus, by understanding the border as a relational effect we reveal how it can be a ‘matter of concern’ for one partner (constraining its ability to thrive and grow) and just a ‘matter of fact’ for the other (see Latour Citation2004, on these concepts). Therefore, the interest in overcoming a border is not necessarily shared, and the opinions on why, how and when to revise a border are likely to differ. Differences in enacting the border can, over time, result in a contested terrain. The discrepancies, in how the geography is understood, in municipal concerns and abilities to act, etc., are referred to as asymmetries in this paper.

Given the ANT-inspired approach, we follow this research tradition by offering a case-study based on primarily ethnographic material. Our case reveals how the geography of the territory and the border has been enacted in different ways in two municipalities (Kumla and Hallsberg), and how this has resulted in an asymmetric geography which affects the collaborations within land-use planning. In the case study, we do this in three ways. First, we examine the different relational positions of the municipalities within the emerging soft region, and the tension this causes, especially at the border in question. Second, we provide an interpretation of two approaches of handling the border issues – as a matter of procrastination and provocation respectively. Approaches which clearly relate to the municipalities’ different relational positions. Finally, we show how decades of asymmetric planning have resulted in a haunted border, which constrain collaboration, and even hinder discussions concerning the border.

Methods and material

This paper studies a border which, in the name of functional regions or regional enlargement, should have been overcome (one way or the other) several decades ago. It is based on a single case study of two municipalities, Hallsberg and Kumla, with a long history of border-related conflicts and collaborations. The study details the geography with the help of three main sources; interviews, document analysis and examinations of map and plans. The documents are primarily public documents in the form of municipal comprehensive plans, detailed development plans, investigations, reports, decisions and minutes as well as official statistics and governmental reports, bills and legislation.

Ten semi-structured interviews (Kvale Citation2009) with leading politicians and officials from both municipalities were conducted during spring 2017. One additional interview with an official from the County Administrative Board was conducted in February 2018. The purpose of the latter interview was to obtain an independent reconciliation of the interview knowledge gained in both municipalities. All interviews were carried out by a spatial planner with many years of experience in border conflicts, albeit in another part of the country. These experiences have been important for the problem formulation, for asking relevant questions, but also for understanding the complexity of the case in question. The analysis was performed by both authors. The interviews offered not only insights into the planning process and how it is perceived by various actors, but they also helped us to find new relevant public documents and to understand and verify the contents of public documents, and vice versa.

The study complements (and draws on) previously conducted research on inter-municipal collaborations in Sweden, which has explored collaborations (primarily in sectors other than spatial planning) and the reforms of merging municipalities in Sweden (Gossas Citation2006; Anell and Mattisson Citation2009; Erlingsson, Ödalen, and Wångmar Citation2015). The interest in local municipalities is not surprising given their key role in Swedish administration in general and in spatial planning in particular, as explained below. However, in these studies the geography has gained limited attention, and the way the borders are being negotiated in local planning has not previously been studied.

Swedish planning at the border

Spatial planning in Sweden is mainly a municipal concern. The municipalities are expected to plan and govern where, how and when urban development can take place. Building permits are granted pursuant to legally binding detailed development plans, which in turn are based on a more general comprehensive plan (SFS Citation2010:900).

A governing regional planning level is absent and the regional planning that does occur is voluntary, except for the region of Stockholm and (since 2019) the region of Scania (Blücher Citation2006; SFS Citation2010:900). National and regional interests are expressed in policies and strategic documents that are to be considered primarily in the municipal comprehensive planning. The state has an advisory and controlling role in both comprehensive and detailed development planning. Through the County Administrative Boards (CAB) the municipalities are provided with advice as well as being reviewed. When municipalities are in the process of developing a new plan, the CAB have the authority and obligation to intervene and, when it comes to detailed development plans, even cancel the plan if, amongst other things, ‘the regulation of such matters as the use of land and water areas relating to several municipalities is not appropriately coordinated’ (SFS Citation2010:900, Chapter 11, Section 10, unofficial translation).

The premise of the legal provisions is that boundary-crossing municipal matters should be highlighted and investigated jointly by the concerned municipalities (SOU Citation2018:46). There are some uncertainties regarding the grounds for the intervention of the CABs which relates to whether the CABs are to intervene on their own initiative – regardless if any of the municipalities concerned have raised an issue – or whether they are to act only in cases where the municipalities take the initiative and raise disagreements or questions that need inter-municipal coordination (SOU Citation2018:46; SOU Citation2005:77). It is relatively uncommon for insufficient inter-municipal coordination to lead to comments and interventions by a CAB. During the past ten years scarcely eight percent of the municipal comprehensive plans reviewed have comments on such lack of coordination. However, the majority of these comments did not refer to municipal interests but rather matters of national interests needing inter-municipal coordination according to the CAB (Boverket Citation2008–2019).

Even if municipalities in Sweden to some extent do collaborate regarding spatial planning, research and public inquiries indicate that joint planning is primarily conducted at an overarching level and does not address issues involving prioritization or resolving conflicts of interest (SOU Citation2005:77; Lindstenz Citation2008), or fails because of conflicts of interest, political disunity and competition (Gossas Citation2006). The same tendencies appear in other European countries as shown in studies of, among others, Hulst & Van Montfort (Citation2007; Citation2012) who claim that collaborations take place in planning forums where decisions can be made in consensus and local autonomy is not threatened.

Mapping out the asymmetries

Following Balibar’s notion that ‘borders are everywhere’ (Citation1998), recent research within border studies illustrates that borders are not only to be found at the edge but all over the territory, constituted in broader social practice and discourses (e.g. Paasi Citation2009; Rumford Citation2012).Thus, to understand the asymmetries which characterize the enactment of the border, a brief examination of the thrust for an expanding soft region is required. This first section maps out asymmetries beyond the specific border, not least with conventional (Euclidean) maps. Yet, we use these maps to tease out relations between sites, relations which are also expressed by the interviewees.

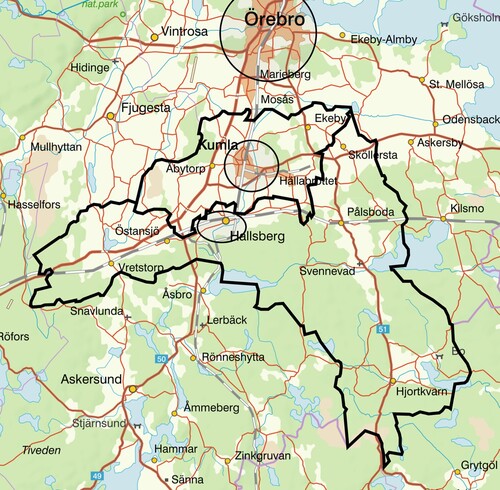

The neighbouring municipalities Hallsberg and Kumla are situated in the southern part of Örebro County. They are both relatively small in relation to the municipality of Örebro which is the regional centre (see ). The municipality of Hallsberg has about 15,900 inhabitants and the corresponding figure for Kumla is 21,700 (SCB Citation2020a; Citation2020b).

Figure 1. The territories of the two municipalities (enhanced black lines). The towns Örebro, Kumla and Hallsberg are circled in order to highlight the geographical relations. Map source: Lantmäteriets Geografiska SverigeData, 2020-01-24. Scale: 1 cm equals 4.2 km.

The town of Kumla is centrally located within the municipality, along the railroad between Hallsberg and Örebro. The close proximity to Örebro has a great significance for its growth capacity: fast communications and attractive housing, at a lower cost than can be found in Örebro, encourages young families with children, among others, to settle in Kumla (Kumla kommun Citation2011a). The orientation towards Örebro also appears in the municipality's comprehensive plan, where the development of housing and business development is clearly assigned to the northern parts of the municipality (Kumla kommun Citation2011b).

The town of Hallsberg lies and pushes alongside the northern border towards the municipality of Kumla – see . Originally, the border at this point was located in line with the railroad, immediately north of the track area. However, the location of the border has been adjusted on several occasions over the years (Hallsbergs kommun Citation2016; Citation2011). The argument for adjustments has been that new land is needed for enterprises in close proximity to the railway, but housing areas have also been built on land that has been incorporated through the border adjustments. The orientation towards the north can be seen also in Hallsberg’s future development plans (Hallsbergs kommun Citation2011; Citation2016). This causes evident asymmetries as Kumla, for its part, has limited interest in developing these areas.

Hallsberg and Kumla constitute, together with the municipality of Örebro and nine other municipalities, the Region Örebro County (RÖC), which has the same territorial demarcation as the County Administrative Board of Örebro. RÖC represents the regional political level and this ‘hard’ region is primarily responsible for public health care and also works with public transportation, infrastructure and regional growth. The region's policy documents describe regional enlargement both as an ongoing phenomenon and as a stated goal in itself, on the grounds that it is the large labour market regions that have the best conditions for growth (Region Örebro Citation2018; Citation2011).

The municipalities of Hallsberg and Kumla have been part of the same local labour market for several years and have developed a number of formal collaborations with each other and with other municipalities in the region. Collaboration takes place in various sectors – including fire department, education, and technical services (Hallsbergs kommun Citation2020; Kumla kommun Citation2020). In 2015 a contractual cooperation between Hallsberg and Kumla was introduced in the areas of spatial planning, building-permission and environmental and health protection. This cooperation is governed by separate political committees in each municipality while the administration is shared. Staff are employed and located in Kumla, from which Hallsberg in practice buys these services. The goal is to gradually deepen the cooperation with an ambition for a future joint political committee in this sector (Hallsbergs kommun Citation2016).

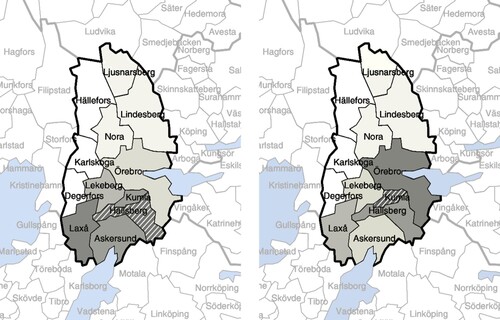

The different inter-municipal cooperations carried out by Hallsberg and Kumla (see ) weave a number of different webs of ‘thin regions’ – sectorial collaborations that bridge the territorial boundaries of the individual municipalities (Gossas Citation2006) and contribute to overcoming their barrier effects, or in other words – soften the ‘hard' space (cf. Paasi and Zimmerbauer Citation2016 and Zimmerbauer and Paasi Citation2020, though on another scale).

Figure 2. The geography of formal inter-municipal cooperation according to Hallsberg, to the left, and Kumla, to the right. A darker shading represents a greater amount of collaborations – from 1 to 7, White = 0. The thick black contour represents the geographical demarcation of Örebro County. Map source: SCB. Scale: 1 cm equals 26 km.

These inter-municipal networks differ both in terms of who they collaborate with and what they collaborate on. The differences also illustrate their different relations to Örebro, which is of crucial importance since it superimposes and exaggerates the local border asymmetries of Hallsberg and Kumla. This asymmetry is described by several of the interviewees in terms of ‘ … advantage of being close to Örebro’ when discussing growth and competition (Politician 1, Hallsberg; Politician 4, Kumla; Official 2, Hallsberg).

We notice the demand, that when people want to buy land and so on, that we still have vacant plots towards Hallsberg [within the Municipality of Kumla] … .while we have a long waiting list in the north part towards Örebro.

(Politician 4, Kumla).

… you keep an eye on each other a little, it's a bit of a village feud here … … Kumla, they have the advantage of being close to Örebro.

(Official 2, Hallsberg).

Thus, even if the two municipalities do collaborate they are simultaneously competing – not least to attract companies and new taxpaying residents (Official 4, Kumla; Politician 2, Hallsberg). This competition tends to obscure ongoing cooperation as well as the incentive for potential new initiatives. Previous research and practice indicates that inter-municipal collaboration occurs when it is expected to lead to mutual gain and not when there are conflicts of interest among the municipalities (SOU Citation2005:77; Lindstenz Citation2008; Rader Olsson and Cars Citation2011).

Procrastinations

Hallsberg’s development has since the 1860s been hampered by the fact that the municipality’s development plans have been intimately connected with demands for adjustment of the municipal border facing Kumla.

(Hallsbergs kommun Citation2011, 53).

This quote from Hallsberg’s previous comprehensive plan can be understood as an expression of frustration over the territorial preconditions. In the consultation proposal that preceded the adopted plan, Hallsberg expressed this frustration even more clearly by letting the land-use map show urban development interests that crossed the municipal border and reached into the territory of Kumla (Hallsbergs kommun Citation2008). Kumla replied diplomatically that the proposed urban development, of course, still requires a discussion with Kumla and the County Administrative Board on how this development and eventual border adjustments can be implemented (Hallsbergs kommun Citation2008; Citation2010).

According to Swedish legislation such inter-municipal conflicts shall attract the attention of the County Administrative Board (CAB), and consequently, the CAB of Örebro called the two municipalities for a meeting to initiate a dialogue. The minutes from this meeting provide a rare official note of the border conflict. The report states that Hallsberg, in the consultation proposal, wanted to present ‘a draft for border adjustment, or rather a direction/goal to strive for’. Furthermore, the municipality expressed a wish for adjustments of the border in the future, in order to facilitate a development of Brändåsen (LST Citation2011) – see . Kumla on their part announced that their main interest regarding urban growth is towards the north but they nevertheless share some urgent inter-municipal matters in the southern municipal parts – such as industrial railroad tracks and sewerage issues. Therefore, they argued, ‘The most important thing for Kumla is that Hallsberg takes the initiative to discuss the border issue because it is primarily in Hallsberg's interest’. In addition, Kumla brings up one matter of concern: the fact that Hallsberg is purchasing properties in the border zone within the municipality of Kumla. As will be discussed in the next chapter, such land ownership opens up for incremental border adjustments, which is why the municipality calls for information of such purchases.

Figure 3. Map showing the towns of Kumla and Hallsberg, the municipal border (enhanced black line) and development sites: 1 – Brändåsen, 2 – Tälleleden/Ulvsätter, 3 – Rala, 4 – Kvarntorp. Map source: Lantmäteriets Geografiska SverigeData, översiktskarta 2020-01-24. Scale: 1 cm equals 1.5 km.

The meeting ended with an agreement that Hallsberg should, in its comprehensive plan, remove development areas located within the municipality of Kumla (see ). In addition, it was decided that officials from both municipalities should meet (in May-11) to come up with a proposal on how to solve the ‘urgent’ need of border adjustments for the development of an industrial area. Finally, larger cross-border issues (eg logistics areas) should be jointly investigated in the longer term, for example through an in-depth comprehensive plan (LST Citation2011).

One of Hallsberǵs main matters of concern at the border was their vision to develop Tälleleden/Ulvsätter further west into Brändåsen within the territory of Kumla. In Hallsberg's comprehensive plan, this is referred to as a desired development of the area to become the ‘Hallsberg Logistic Center’ (Hallsbergs kommun Citation2011). The ambition to develop the logistic centre via joint municipal planning in the form of an in-depth comprehensive plan has, according to the interviewees, remained alive since the meeting with the County Administrative Board in 2011. In 2012, the then-management in Hallsberg was prepared to start the work and presented to Kumla an idea of such a plan. The question led to discussions about opportunities to adjust the municipal boundary instead – by exchanging territory with each other – in areas where mutual benefit could be found. Discussions were ongoing between officials in both municipalities during the fall and winter 2012–2013, but no concrete planning or investigations were initiated. A few years later, in connection with the work on a new comprehensive plan, the question of Brändåsen, as well as other border-related issues, surfaced once again (Hallsbergs kommun Citation2016). The plan states that in 2016, the municipalities of Hallsberg and Kumla ‘will begin a dialogue regarding the border between the two municipalities’ (Hallsbergs kommun Citation2016).

It is Brändåsen … the land around Brändåsen, that we would like to continue working with …

(Official 1, Hallsberg).

Despite the agreements made in 2011, the major cross-border issues had still not been solved at the time of the interviews six years later. Several interviewees in Hallsberg point out logistics and business development further west into Brändåsen as a strategically important issue for both the municipality and the region (Politician 1; Politician 2; Official 1; Official 2). The intended development is mentioned as being in progress but no formal political assignment to start planning has yet been given.

Yes, we want an assignment from the politicians, and we’re not getting that. We don’t get any assignments! And if Kumla doesn’t want to do anything then we can’t move forward in this matter.

(Official 1, Hallsberg).

Hallsberg is dependent on the cooperation with Kumla, and Kumla seems to procrastinate on the issue, even though they also have reasons to discuss border adjustments. Kumla has a special interest in the eastern part of its territory, in the industrial area Kvarntorp which is situated close to the border of the more rural areas of the municipality of Hallsberg (Kumla kommun Citation2011a). The officials in Kumla thus have a local governmental assignment to discuss the border issues with Hallsberg, but the organization feels that the internal discussions are fruitless:

We do have an assignment and we do have a steering group where we will discuss these border issues, eh, between Kumla and Hallsberg. I think that if we had been allowed to just solve that question on its own, we would have solved it. I think we would have been able to see it in a rational effective light and would have found some way to come to an agreement. But we’re not managing to do that. Because we know that it won’t be possible as there’s too much politics involved in the whole thing. I’ve even made the point that we could sit down for ten meetings and still get absolutely nowhere, huh …

(Official 3, Kumla).

So even if Kumla has its own interests in discussing border issues, and is aware of and positively aligned with Hallsberg’s development plans, not much happens. Municipal border adjustments are considered difficult issues, the consequences of which must be carefully studied (Politician 5, Kumla; Politician 4, Kumla).

Yes, and actually we didńt want to do that [investigate and plan at Brändåsen], it has never been part of our plans that we should develop it, because it is a bit far from us, it has been more in Hallsberg's interest … But when you look at it, really … , border issues, where it pays off the most for us, is in the discussions with Örebro … , because that´s where things happen.

(Politician 4, Kumla).

Nothing in the interviews suggests that Kumla deliberately delay the issue of border adjustments (or collaboration concerning the Brändåsen site), but they have practical reasons to do so: Brändåsen is not a matter of concern for Kumla, and as time and resources are always limited, this matter does not end up on the shortlist of most pressing issues to take care of. With such everyday down-prioritizations and procrastinations the marginal status of the Hallsberg border is maintained in the politics and planning of Kumla. In addition, as one of the politicians pointed out: border issues are ‘complicated’. As the following sections will show, this could be another way of saying that the border is a contested terrain after decades of partly uncoordinated and therefore asymmetric planning actions.

Provocations

There are several ways to solve potential border conflicts in land-use planning. The Planning and Building Act assumes it will be based on joint efforts of the two municipalities. Joint efforts, however, presume simultaneous expectations of mutual gain as an incentive to allocate time and resources according to a common schedule (SOU Citation2005:77; Lindstenz Citation2008; Rader Olsson and Cars Citation2011). Our case reveals two different ways of understanding the Hallsberg/Kumla border, which hinders not only an agreement but the very motives for initiating (or prioritizing) such a dialogue. As a consequence of this asymmetry, Hallsberg is left to take the initiatives, initiatives which easily provoke their neighbour. This section explores (intentional and unintentional) provocations as an approach.

A major border adjustment, initiated in 1965, is a case in point. It was initiated unilaterally with a letter from Hallsberg to the Legal, Financial and Administrative Services Agency (LFASA, Swedish: Kammarkollegiet) requesting that land areas of 1,130 hectares to be transferred from Kumla to Hallsberg in order to enable an efficient urban development. The proposal was not approved, either by Kumla, or the County Administrative Board. An inquiry was then initiated by the LFASA whereby the municipalities eventually agreed on a more limited divisional change to the mutual benefit of both parties. This resulted in a border adjustment in 1977 in which Hallsberg got its entire industrial area gathered within the municipality. In exchange Kumla was given new land in the eastern part of the municipality and the opportunity to plan for the development of Kvarntorp’s industrial area (Kumla kommun Citation2011c).

Another (unintended) provocation took place in 2001–2002 when Hallsberg bought a number of properties within the territory of Kumla. Following the purchases Hallsberg applied to merge these properties with another property on the other side of the border within the municipality of Hallsberg – a property formation procedure which would also result in a revised municipal border. Since the area did not house any residents and neither the County Administrative Board nor the municipality of Kumla had formal objections to the proposed border adjustment, it was implemented in 2003. This made it possible for Hallsberg to develop the industrial area Tälleleden/Ulvsätter (ibid). Although no formal objections were raised, the purchases nevertheless caused a lingering annoyance in Kumla. This annoyance came to the fore in connection with the detailed planning of the area, ten years later, and then resulted in Hallsberg reversing and not implementing yet another planned property merger which would have resulted in further border adjustments. The idea was to incorporate a tie-shaped property (see ) into their own territory and thereby make detailed planning of the entire site possible, but instead, the tie-shaped part was left un-planned within the territory of Kumla, though it is still owned by Hallsberg (Politician 2, Hallsberg; Politician 3, Hallsberg; Official 1, Hallsberg; Official 2, Hallsberg).

Figure 4. Map from the detailed plan ‘Norr om Tälleleden'. The tie-shaped area is surrounded by a red circle (upper left). The municipal border is enhanced with a dotted bold dark red line (Hallsbergs kommun Citation2014). Scale: 1 cm equals 120 m.

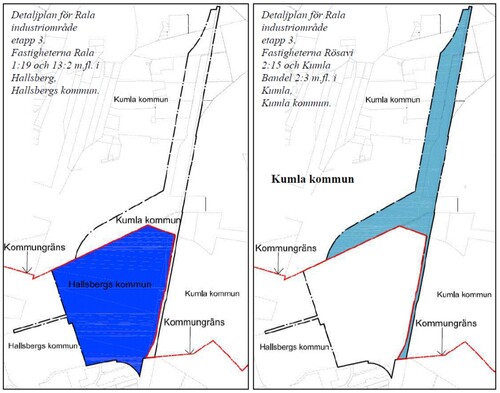

Another example where provocation was used concerns the planning of the Rala industrial area (see and ). The matter originated in the urgent need for border adjustments that was discussed at the previously-described meeting with the CAB in 2011. This time the issue was not resolved by border adjustment, but by both municipalities simultaneously producing synchronized detailed plans – one on each side of the border in a joint and parallel process. This could be interpreted as a successful intervention made by the CAB. However, in the interviews, it is not the CAB, but another actor that is highlighted as being crucial in order for this cooperation to take place: Several of the interviewees mentioned a large multinational company as being a driving force as they bought the land and proposed an establishment that would create a large number of jobs presumed to benefit both municipalities (Official 2, Hallsberg; Politician 2, Hallsberg).

Rala and the Train Alliance development was, right from the start, a very large project that would create between 500 to 800 new jobs … the establishment was so large that it really brought great benefits with it, it was in the borderland between both Hallsberg and Kumla, so we had detailed plans made from both sides and it was a very good collaboration.

(Politician 2, Hallsberg).

Symptomatically, and in accordance to prior research (e.g. Lindstenz Citation2008; Rader Olsson and Cars Citation2011): Once a joint interest was defined then the border issue turned out to be relatively easy to solve. As illustrates, the ‘hard’ border can easily be softened in such cases (compare e.g. Zimmerbauer and Paasi Citation2020).

Figure 5. Illustration from the synchronized detailed plans for Rala industrial area, showing the distribution of the site in each municipality (Hallsbergs kommun Citation2012). The red line represents the municipal border. Scale: 1 cm equals 330 m.

Several concrete results and actual agreements have thus begun, when viewed from Kumla’s perspective, as a provocation. This also applies to the previously described question of a continued development of Tälleleden/Ulvsätter into Brändåsen. After Hallsberg in 2008 suggested industrial development within the neighbouring municipality’s territory, the claims were described as a more legitimate inter-municipal interest in the later comprehensive plan (Hallsbergs kommun Citation2008; Citation2016). What started as a provocative land claim led to an intervention by the County Administrative Board and has evolved into an inter-municipal interest. Thus, there are re-evaluations of interests and simultaneous renegotiations of the border going on here, driven, not least, by provocations. This involves slow and fragile processes that may come to a halt or even be reversed if the political viewpoints or other circumstances change.

Perhaps a provocative approach is a necessity for the border to be questioned and renegotiated at all? Especially when joint efforts and mutual gain are out of reach as a starting point. But provocation comes at a high price, as will be discussed in the next section.

Haunted by the past

Hallsberg has provoked Kumla more than once to make a change. Our interviews show that these provocations linger. Furthermore, they are narrated in ways which make inter-municipal collaboration difficult. In interviews in Hallsberg the border issue is frequently described as sensitive:

But when you get to the topic of municipal borders, it becomes sensitive, which is how it feels to me … that it is politically sensitive.

(Official 2, Hallsberg).

The caution on Hallsberg’s part, the seemingly exaggerated regard for Kumla and the fear of causing even more provocation is matched by Kumla’s irritation over previous property purchases and border adjustments (Official 5, Kumla). Several interviewees return to an incident some years ago when a number of inhabitants switched municipal affiliation as a result of a border adjustment (Politician 2, Hallsberg; Politician 3, Hallsberg; Politician 4, Kumla; Politician 5, Kumla; Official 1, Hallsberg; Official 3, Kumla; Official 4, Kumla).

It went wrong … At first we had collaborations and so on, and we made a municipal border adjustment with the intention that there would be another adjustment where we would gain some residents … and this has not happened so far, so that question is still relevant really.

(Politician 5, Kumla).

It was an exchange that we did with Hallsberg, where they got a whole group of residents and then didńt give anything back in exchange … … . I think it was at a time when it was very good for Hallsberg to get this land from us, um … , and they didn’t have anything really good to trade back, and it was assumed that this would stay in the memory, for later. But the memory probably slipped away, ha-ha … Or the good will did.

(Politician 4, Kumla).

One of the officials in Kumla mentions a rumour that one hundred inhabitants had to shift municipality due to this border regulation, and argues that the politicians would like to see as many new inhabitants from Hallsberg:

… The history with these 100 inhabitants that were transferred from Kumla to Hallsberg … . it’s like an irritating splinter that you can’t get rid of.

(Official 4, Kumla).

In Hallsberg, they are said to be, if not unknowing, then at least less informed:

And where this feeling of injustice comes from, it's like that they, in some way, still feel .., eh not really .., eh .., fairly treated eh, in Kumla. It's hard to understand. When I pose questions, so to speak, to Kumla, on this matter, they cannot give me a real answer, hm. There is some old history there that I have not really.., have not yet understood.

(Official 1, Hallsberg).

So I dońt know what is true and what is not … , but I mean, there will be discussions and those discussions will live on … Kumla probably experiences an injustice, but I dońt think there is any.

(Politician 2, Hallsberg).

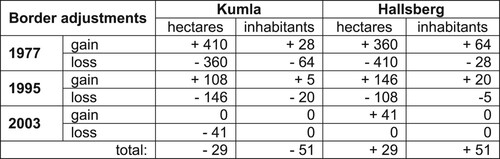

One may have to go far back in history to understand why this is still provocative and why the feeling of injustice lingers. Significant border adjustments have been made on several previous occasions during the twentieth century; 1927, 1928, 1947 and 1965. In all of these cases land has been transferred from Kumla to Hallsberg, totalling about 850–900 hectares, and some of these changes have also included inhabitants (Kumla kommun Citation2011c; Hallsbergs kommun Citation2011). However, when Kumla in 2011 compiled a report regarding earlier border adjustments, they focused on the three most recent occasions and the consequences they have had for the distribution of the territories and the number of inhabitants (Kumla kommun Citation2011c) ().

Figure 6 . The three most recent border adjustments and their consequences for area and population. Source: Kumla kommun (Citation2011c).

In total, Kumla has lost 51 inhabitants and 29 hectares of its territory through three border adjustments since the 1970s. The first two led to a number of people having to change municipal affiliation, wherefore the financial consequences were investigated. At the 1977 adjustment, the differences in tax revenue were assessed to be marginal and compensation not needed. After the 1995 border adjustment, however, financial compensation was paid from Hallsberg to Kumla for a number of years as a result of lost tax revenue.

The boundary adjustment in 2003 is, as previously described, a result of a number of strategic land purchases and property mergers made by Hallsberg (Kumla kommun Citation2011c). Even if Kumla did not oppose the mergers at the time, the strategic land purchases are seen as provocative today:

The municipality of Hallsberg … ., they have bought some land in Kumla, also on that west side, and that is just the type of thing that is a little provoking …

(Politician 5, Kumla).

How should we understand this conflict? It might not be correct to argue that the border is in the ‘shadow of past planning’ (Qviström Citation2010), as the report made by Kumla provides limited (if any) support for the current narrative. It is not primarily a matter of revising past wrongdoings. Indeed, the factual report was not mentioned by the interviewees in Kumla, but brought to the fore by an interviewee in Hallsberg. The narrative (and concerns) in Kumla and Hallsberg are clearly independent of documented border adjustments. Rather, it seems as if decades of procrastinations and provocations haunt the current border conflict (cf. Bickerstaff Citation2012). These feelings of wrongdoings, vague narratives and anecdotes are far from easy to bring to the light: they cannot easily be resolved and yet they need to be taken seriously if aiming for a fruitful dialogue, as they clearly obscure the dialogue today.

As a result, the politicians and officials in Hallsberg have to walk on eggshells because of the history, and how it is being narrated. The haunted conflict, in combination with the asymmetric geography, explains the deadlock: the dialogue is hindered due to the different notions about how much any ‘debt’ needs to be repaid by Hallsberg in upcoming negotiations (Official 3, Kumla).

It is not just the border that is being re-created in this process. The case of Kumla and Hallsberg shows that border renegotiation also feeds competition and leads to old conflicts being revived and re-created. The negotiation thus perpetuates and reinforces contradictions, encourages territorial thinking and makes the local border linger (cf. Zimmerbauer and Paasi Citation2020). Something that, in turn, may have an impact on other inter-municipal cooperation and the relationship between municipalities and other actors in general.

Conclusion

With the thrust for regional enlargements and soft regions, new geographies will be inscribed in which some towns are central and others are peripheral. This uneven geography is likely to spur provocations, and cause conflicts, at the local borders. Such asymmetries need to be understood as part and parcel of the development of soft regions, and need to be addressed to improve the collaboration more generally. With this in mind, the paper contributes to a relational understanding of the border, which brings in notions of history, domain structure and morphology, issues which in other studies have been associated with a complementary (or competing) perspective of topography. This opens up for a discussion on asymmetries, and for further studies of the interplay between the renegotiation of the local borders within emerging soft regions.

By following the course of events this paper has detailed the geography of planning concerning a contested local border zone between the two municipalities Hallsberg and Kumla. The case describes how the municipalities enact the border differently, not least due to different geographical settings where only one of the municipalities is constrained by the border. This asymmetry has forced Hallsberg to be proactive, and even provocative, to make adjustments or collaborations across the border feasible. Unfortunately, such provocations linger, and may affect collaborations beyond the border issue.

The relational approach helps us to notice that the asymmetric geography isn’t just something that was there from the start. It isn’t only a matter of distances and accessibility, e.g. closeness to the regional centre. Rather, this geography has been enacted for a long time, in different ways, and has thus resulted in a haunted border, a source of frustration and annoyance in the attempts to bridge differences in the soft region. In the case studied, historically rooted and embedded contradictions haunt the conversation in a deeper way than ‘plain’ conflicts of interest, and thereby, from time to time, cause procrastination and rule out possibilities for negotiations, coordinated planning or any other collaborative actions – it takes two to tango.

We argue that a relational understanding of the geography (and history) of planning can be a considerable complement to recent discussions in planning theory on e.g. deliberative or agonistic planning, to facilitate inter-municipal and cross-border planning in general. Furthermore, as border/bordering studies show, the conflicts are not always centred at the border. Therefore, to understand the enduring conflicts, it might be more fruitful to examine the asymmetric geographies of the municipalities and their planning more generally, to gain a better understanding of the differences and potential arenas for a dialogue.

In relation to planning practice, our observations to some degree contrast with the current Swedish legislation and praxis, which is based on a notion of a rational spatial planning where inter-municipal matters will be jointly investigated and solved. Such planning, we argue, presumes symmetries regarding municipal concerns, abilities to act and how the geography is understood. In emerging soft regions, such conditions are likely to be rarer in favour of emerging asymmetries. However, it is not the ambition of this paper to demonstrate how to achieve inter-municipal coordination in practice or to propose changes in legislation. This paper though demonstrates that a relational understanding of the border and the local geography is crucial for managing border related conflicts – thereby also wishing for a planning legislation and practice that better pays attention to and takes into account the geography and asymmetry of local borders.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allmendinger, P., and G. Haughton. 2009. “Soft Spaces, Fuzzy Boundaries, and Metagovernance: The New Spatial Planning in the Thames Gateway.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 41 (3): 617–633. doi:10.1068/a40208

- Anell, A., and O. Mattisson. 2009. Samverkan i kommuner och landsting – en kunskapsöversikt (Cooperation in Municipalities and County Councils: An Overview). Lund: Studentlitteratur AB.

- Balibar, É. 1998. “The Borders of Europe.” In Cosmopolitics: Thinking and Feeling Beyond the Nation, edited by P. Cheah, and B. Robbins, 216–229. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Beauregard, R. A. 2015. Planning Matter: Acting with Things. London: The University of Chicago Press, Ltd.

- Bickerstaff, K. 2012. ““Because We’ve got History Here”: Nuclear Waste, Cooperative Siting, and the Relational Geography of a Complex Issue.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 44: 2611–2628. doi:10.1068/a44583

- Blücher, G. 2006. “1900-talet – det kommunala planmonopolets århundrade (The 20th Century: Era of Sweden’s Municipal Planning Monopoly).” In Planering med nya förutsättningar: Ny lagstiftning, nya värderingar, edited by G. Blücher, and G. Graninger, 133–155. Vadstena: Stiftelsen Vadstena Forum för Samhällsbyggande.

- Boverket. 2008–2019. Summaries of planning and building questionnaire surveys for the years 2008–2010 and 2012–2019. Reports for the years 2013–2019 are available at https://www.boverket.se/sv/om-boverket/publicerat-av-boverket/oppna-data/plan–och-byggenkaten/ (accessed 22 June 2020). Earlier reports were received directly from an employee at Boverket

- Brambilla, C. 2015. “Exploring the Critical Potential of the Borderscapes Concept.” Geopolitics 20 (1): 14–34. doi:10.1080/14650045.2014.884561

- Brenner, N., D. J. Madden, and D. Wachsmuth. 2011. “Assemblage Urbanism and the Challenges of Critical Urban Theory.” City 15: 225–240. doi:10.1080/13604813.2011.568717

- Erlingsson, G. Ó., J. Ödalen, and E. Wångmar. 2015. “Understanding Large-Scale Institutional Change.” Scandinavian Journal of History 40 (2): 195–214. doi:10.1080/03468755.2015.1016551

- Gossas, M. 2006. Kommunal samverkan och statlig nätverksstyrning (Municipal cooperation and state network governance), Doctoral dissertation, Uppsala University.

- Graham, S., and N. Thrift. 2007. “Out of Order: Understanding Repair and Maintenance.” Theory, Culture & Society 24: 1–25. doi:10.1177/0263276407075954

- Hallsbergs kommun. 2008. Samrådshandling Översiktsplan Hallsbergs kommun (Comprehensive plan, consultation proposal), Strategiutskottet.

- Hallsbergs kommun. 2010. Samrådsredogörelse Översiktsplan (Comprehensive plan, consultation report), Kommunstyrelsens Strategiutskott.

- Hallsbergs kommun. 2011. ÖP Hallsbergs kommun 2010-2020 (Comprehensive plan), antagen av kommunfullmäktige 2011-05-16.

- Hallsbergs kommun. 2012. Detaljplan för Rala industriområde etapp 3 (Detailed plan), antagen av kommunfullmäktige 2012-12-17. Available at https://www.hallsberg.se/download/18.5a322074160e4121cd3cec6a/1516720117552/rala_industriomrade_etapp_3_planbeskrivning.pdf (accessed 24 August 2020)

- Hallsbergs kommun. 2014. Detaljplan för område norr om Tälleleden (Detailed plan), antagen av kommunfullmäktige 2014-04-28. Available at https://www.hallsberg.se/download/18.5a322074160e4121cd3cde6d/1516715987784/norr_talleleden_plankarta.pdf (accessed 24 August 2020)

- Hallsbergs kommun. 2016. Översiktsplan för Hallsbergs kommun (Comprehensive plan), antagen av kommunfullmäktige 2016-11-28. Available at https://www.hallsberg.se/download/18.2812fcf2160e442bbb4e3d92/1516810562345/%C3%96versiktsplan%20f%C3%B6r%20Hallsbergs%20kommun.pdf (accessed 24 August 2020)

- Hallsbergs kommun. 2020. Kommunens organisation (The municipal organization), web information. https://www.hallsberg.se/organisation-och-styrning/kommunens-organisation.html (accessed 24 April 2020)

- Haselsberger, B. 2014. “Decoding Borders. Appreciating Border Impacts on Space and People.” Planning Theory & Practice 15 (4): 505–526. doi:10.1080/14649357.2014.963652

- Haughton, G., P. Allmendiger, D. Counsell, and G. Vigar. 2010. The New Spatial Planning: Territorial Management with Soft Spaces and Fuzzy Boundaries. London: Routledge.

- Healey, P. 2007. Urban Complexity and Spatial Strategies. London: Routledge.

- Heley, J. 2013. “Soft Spaces, Fuzzy Boundaries and Spatial Governance in Post-Devolution Wales.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37: 1325–1348. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01149.x

- Hulst, R., and A. Van Montfort. 2007. “Inter-Municipal Cooperation: A Widespread Phenomenon.” In Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Europe, edited by R. Hulst, and A. Van Montfort, 1–21. Netherlands: Springer.

- Hulst, R., and A. Van Montfort. 2012. “Institutional Features of Inter-Municipal Cooperation: Cooperative Arrangements and Their National Contexts.” Public Policy and Administration 27 (2): 121–144. doi:10.1177/0952076711403026

- Kumla kommun. 2011a. Kumla 25 000 Översiktsplan för Kumla kommun Del 2 – Planeringsförutsättningar och riktlinjer (Comprehensive plan, part 2), adopted by the municipal council 2011-02-14.

- Kumla kommun. 2011b. Kumla 25 000 Översiktsplan för Kumla kommun Del 3 – Kartbilagor (Comprehensive plan, part 3), adopted by the municipal council 2011-02-14.

- Kumla kommun. 2011c. Markbyten och fastighetsköp berörande Hallsbergs kommun och Kumla kommun (Land exchanges and property purchases concerning the municipality of Hallsberg and the municipality of Kumla), rapport, kommunledningskontoret, 2011-11-01.

- Kumla kommun. 2020. Bolag och kommunalförbund (Companies and municipal cooperations), web information. Available at https://www.kumla.se/kommun-och-politik/kommunens-organisation/bolag-och-kommunalforbund.html (accessed 24 April 2020)

- Kvale, S. 2009. Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun (The Qualitative Research Interview). Lund: Studentlitteratur AB.

- Latour, B. 2004. “Why has Critique run out of Steam? From Matters of Fact to Matters of Concern.” Critical Inquiry 30 (2): 225–248. doi:10.1086/421123

- Law, J. 2002. “Objects and Spaces.” Theory, Culture and Society 19: 91–105.

- Lehtinen, A. 2011. “From Relations to Dissociations in Spatial Thinking: Sámi ‘Geographs’ and the Promise of Concentric Geographies.” Fennia 189 (2): 14–30.

- Lindstenz, B. 2008. Samspel: regionalt och mellankommunalt samarbete i Stockholms län under ett drygt kvartssekel (Interaction: Regional and Inter-Municipal Cooperation in Stockholm County for Just over a Quarter of a Century). Stockholm: Libris.

- LST. 2011. Minnesanteckningar från möte gällande gränsjustering mellan Hallsbergs och Kumla kommun (Minutes from meeting regarding border adjustment between the municipalities of Hallsberg and Kumla). Länsstyrelsen Örebro (Örebro County Administrative Board), Camilla Johansson, 2011-03-04.

- Malpas, J. 2012. “Putting Space in Place: Philosophical Topography and Relational Geography.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 30: 226–242. doi:10.1068/d20810

- Metzger, J. 2013. “Raising the Regional Leviathan: A Relational-Materialist Conceptualization of Regions-in-Becoming as Publics-in-Stabilization.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37: 1368–1395. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12038

- Murdoch, J. 2006. Post-structuralist Geography: a Guide to Relational Space. London: Sage.

- Newman, D. 2006. “The Lines That Continue to Separate us: Borders in our ‘Borderless’ World.” Progress in Human Geography 30 (2): 143–161. doi:10.1191/0309132506ph599xx

- Paasi, A. 2009. “Bounded Spaces in a ‘Borderless World’: Border Studies, Power and the Anatomy of Territory.” Journal of Power 2 (2): 213–234. doi:10.1080/17540290903064275

- Paasi, A., and K. Zimmerbauer. 2016. “Penumbral Borders and Planning Paradoxes: Relational Thinking and the Question of Borders in Spatial Planning.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 48: 75–93. doi:10.1177/0308518X15594805

- Qviström, M. 2010. “Shadows of Planning: on Landscape/Planning History and Inherited Landscape Ambiguities at the Urban Fringe’.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 92 (3): 219–235. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0467.2010.00349.x

- Qviström, M. 2018. “Farming Ruins: a Landscape Study of Incremental Urbanisation.” Landscape Research 43 (5): 575–586. doi:10.1080/01426397.2017.1353959

- Rader Olsson, A., and G. Cars. 2011. “Polycentric Spatial Development: Institutional Challenges to Intermunicipal Cooperation.” Jahrbuch für Regionalwissenschaft 31: 155–171. doi:10.1007/s10037-011-0054-x

- Region Örebro. 2011. Regional Översiktlig Planering - rumsligt perspektiv på Utvecklingsstrategi för Örebroregionen (Regional Comprehensive Planning – a spatial perspective on Development Strategy for the Region Örebro County). Available at https://www.regionorebrolan.se/PageFiles/1204663/Regional_%c3%b6versiktlig_planering_R%c3%96P.pdf?epslanguage=sv (accessed 27 April 2020)

- Region Örebro. 2018. Tillväxt och hållbar utveckling i Örebro län - Regional utvecklingsstrategi 2018–2030 (Growth and sustainable development in the county of Örebro - Regional development strategy 2018–2030). Available at https://www.regionorebrolan.se/Files-sv/%c3%96rebro%20l%c3%a4ns%20landsting/Regional%20utveckling/Regional%20utvecklingsstrategi/Dokument/2018/RUS%20f%c3%b6r%20webb.pdf (accessed 27 April 2020)

- Rumford, C. 2012. “Towards a Multiperspectival Study of Borders.” Geopolitics 17 (4): 887–902. doi:10.1080/14650045.2012.660584

- Ruming, K., and D. Houston. 2013. “Enacting Planning Borders: Consolidation and Resistance in Ku-Ring-gai, Sydney.” Australian Planner 50 (2): 123–129. doi:10.1080/07293682.2013.776985

- SCB. 2020a. Population and land area within localities, by locality. Every fifth year 1960–2019, Statistiska centralbyrån, SCB (Statistics Sweden). Available at http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/en/ssd/START__MI__MI0810__MI0810A/LandarealTatortN/ (accessed 20 May 2020)

- SCB. 2020b. Kommuner i siffror (Municipalities in figures), Statistiska centralbyrån, SCB (Statistics Sweden). Available at https://www.scb.se/hitta-statistik/sverige-i-siffror/kommuner-i-siffror/#?region1=1861®ion2=1881 (accessed 20 May 2020)

- Scott, J. W., and C. Sohn. 2019. “Place-making and the Bordering of Urban Space: Interpreting the Emergence of new Neighbourhoods in Berlin and Budapest.” European Urban and Regional Studies 26 (3): 297–313. doi:10.1177/0969776418764577

- SFS (The Swedish Code of Statutes). 2010:900. Plan- och bygglag (Planning and Building Act), Finansdepartementet (Swedish Ministry of Finance). Available at https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/plan–och-bygglag-2010900_sfs-2010-900 (accessed 20 December 2019)

- SOU (Swedish Govt. Official Report). 2005:77. Får jag lov? Om planering och byggande (Shall we dance? About planning and Building), Näringsdepartementet (Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation) 2005. Available at https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2005/09/sou-200577/ (accessed 14 January 2020)

- SOU (Swedish Govt. Official Report). 2018:46. En utvecklad översiktsplanering (A Comprehensive Planning Further Developed), Näringsdepartementet (Ministry of Enterprise and Innovation) 2018. Available at https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2018/05/sou-201846/ (accessed 14 January 2020)

- Steele, W., T. Alizadeh, and L. Eslami-Andargoli. 2013. “Planning Across Borders.” Australian Planner 50 (2): 96–102. doi:10.1080/07293682.2013.776977

- Thrift, N. 2006. “Space.” Theory, Culture & Society 23 (2-3): 139–146. doi:10.1177/0263276406063780

- Valverde, M. 2009. “Jurisdiction and Scale: Legal ‘Technicalities’ as Resources for Theory.” Social and Legal Studies 18 (2): 139–157. doi:10.1177/0964663909103622

- Zimmerbauer, K., and A. Paasi. 2020. “Hard Work with Soft Spaces (and Vice Versa): Problematizing the Transforming Planning Spaces.” European Planning Studies 28 (4): 771–789. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1653827