ABSTRACT

Liverpool hosted the European Capital of Cultural (ECoC) in 2008, four years after the city was granted UNESCO World Heritage Site status. A decade later the city council celebrated the anniversary of hosting, while at the same time UNESCO debated the imminent delisting of the city’s world heritage site. Concentrating on data collected during this anniversary year, this paper critically examines the extent to which an ECoC legacy narrative in the city remains intrinsically linked to an economic regeneration-dominated understanding of the role of culture that has changed very little since the bidding and hosting process. Large scale events and visitor economy strategies dominate the cultural offer, whilst heritage, in particular the World Heritage Site, is at best drawn upon in property or tourism led redevelopment advertisement, or, at worst, seen as negatively competing with the progress of a perceived city ‘renaissance’. This article draws upon cross sector multi-stakeholder mapping workshops, interviews and document analysis to explore how a selective legacy narrative continues to affect the development of a more embedded approach to cultural heritage within the city.

1. Introduction

In 2018 Liverpool City Council (LCC) celebrated the ten year anniversary of Liverpool 08, the hosting of the European Capital of Culture (ECoC). Described by one community stakeholder as ‘all about making another big splash’,Footnote1 the Liverpool 18 anniversary events and associated statements sought to focus attention on Liverpool as a destination, a place that had, in the words of the Council’s culture department Culture Liverpool ‘got its swagger back’ and, by 2018, the emphasis remained on ‘putting us quite rightly as a cultural exemplar on a national and international stage’.Footnote2 That same year, the UNESCO World Heritage annual meeting met to discuss the proposal for the imminent de-listing of Liverpool’s World Heritage Site. Inscribed in 2004, by 2012 it was on the world heritage in danger list and facing delisting by 2017. It is the environment that enabled these two quite different, but in several ways linked, events in 2017–2018 that this article explores in order to critically assess the extent to which the rhetoric of one negatively impacted on the realities of another.

This paper draws upon case study specific and regionally focused in-depth qualitative data collected precisely during the time of the ten year anniversary (2017–2018). As this coincided with the proposed de-listing of the UNESCO WHS and brought to the fore differences in the way the city is (re)presented, it provides a lens through which to explore the city’s official legacy narrative of ECoC and set this against multi-stakeholder perspectives. Furthermore, this paper seeks to explore how the rhetoric of a success legacy continues to impact on the development of both culture and heritage within the city and the city region. Here the paper critically explores the enduring faith in culture as a driver for economic regeneration. It investigates how this has played a contributing role in the endangerment of the WHS and has hampered the understanding of wider heritage sites and practices in the city beyond the economic or touristic. To do this, it examines data from regional cross sector stakeholder mapping workshops alongside with interviews, document analysis and participant observations.

Firstly, the paper sets out the methodology utilized, including details of the mapping workshops and of the stakeholders and sectors involved. This is followed by an overview of the ECoC award and the context of Liverpool and the city’s WHS via relevant literature. The article then discusses findings relating to the understanding, environment and challenges for culture and heritage in the city. Finally, the paper discusses the impact of what is here argued to be a highly selective legacy narrative. The paper contends that the use of evaluation and development of a selective success narrative can impact cultural and heritage policies. Economic strategies in the city still fail to engage fully with the idea of embedded or intrinsic cultural offer, preferencing a perceived need to buy in or add cultural value, and this approach is inherently linked to the city’s hosting of ECoC. Here the paper suggests that a prevailing narrative of Liverpool 08 can also be seen to be reflected in both policy and academic discourse which, be it either from an overtly positive or a more critical viewpoint, has discussed the Liverpool ECoC as an almost mythical case in itself, devoid of wider context, and with this has largely failed to explore the impact of this on heritage practices and debates.

2. Definitions and methodology

This section introduces the definitions of ECoC, cultural heritage and governance that are used in the article. It provides details regarding the research methods as well. The data was gathered as part of a thematic project exploring shifts in cultural governance and investigated any shifts in the role and use of culture in related and unrelated policies and strategies in the city since the hosting of Liverpool 08. Whilst the data collected crosses several areas, this paper concentrates on the findings that relate to cultural heritage, economic development and ECoC legacy.

The ECoC programme, an annual award made to two European cities, was developed in 1985 and, according to the EU Commission’s ECoC factsheet ‘Being a European Capital of Culture brings fresh life to these cities, boosting their cultural, social and economic development’ (EU Citation2020, 1). Held for one year, the award involves a programme of cultural events in the host city. Intrinsically bound up with this, certainly since the Glasgow 1990 ECoC, is the concept of urban regeneration and the (re)marketing of elements of a city (e.g. as more creative, more investment worthy or a tourist destination). Cities may adopt a different emphasis and not all take the same route. Fitjar, Rommetvedt, and Berg (Citation2013), for example, discuss how the host city Stavenger had the mission ‘to focus firmly on culture which is in complete juxtaposition with its partner ECOC city, Liverpool, whose bid was based on economic regeneration’ (Citation2013: 66). Largely though, as Boland (Citation2010) points out, ECoC is indicative of policy approaches that utilize culture for economic development and propagate a notion of regeneration via cultural programmes. In terms of the expectations of hosting ECoC, the associated narratives of regeneration or culture or creativity as a driver are ever present (see Degen and Garcia Citation2012, here in relation to the ‘Barcelona Model’). This also has impacts on the built environment, with new structures or changes to existing sites. As Jones and Ponzini (Citation2018) assert, mega-events can often lead to the bypassing of usual procedures in terms of changes to the built environment or the management of heritage sites (434), highlighting a gap in both literature and policy which might examine the often delicate balance between heritage preservation and mega-event planning.

Tensions between social, cultural and economic development have been explored within a wider and oft critiqued shift of the cultural policy paradigm towards the creative industries. Especially in, though not confined to, the U.K. this was framed by New Labour policy of the late 1990s onwards, and the establishment of the Department of Media, Culture and Sport and a particular vision and policy relating to a newly (re) defined cultural and creative industries and creative economy. This focus on creative industries as significant to the economy also coincided, with and encompassed shifts in, city spatial planning. The notion of creative areas in the predominantly urban setting drew upon the ‘creative class’ discourse (Florida Citation2002) and creative clustering models (e.g. from Porter Citation1998) which led in part to gentrification, city branding and selective regeneration policies (see Peck Citation2005 for an early discussion and critique). The policy and planning interventions that went along with this have and continue to be critically discussed (see Flew and Cunningham Citation2010; Pratt Citation2010; Hesmondhalgh and Pratt Citation2005).

There has since been a move, at least within EU Cohesion Policy and funding discourse, towards a more distinct place-based regional policy development (for a discussion of the territorial approach see McCann and Ortega-Argiles Citation2015; Lazzeroni et al. Citation2013). Here existing tangible and intangible cultural heritage assets are seen as key to a regional advantage and distinctiveness. In England, devolution towards regional governance structures and locally elected ‘Metro Mayors’ have shifted policy towards the more regionally relevant and distinctive, encompassing moves towards so-called inclusive growth. In the Liverpool City Region, in terms of culture, this led to a ‘1% Pledge for Culture’ (1% of the budget), and the development of regionally distinctive initiatives (e.g. a ‘Boroughs of Culture’ award) that seek to redress the balance and focus away from the city centre. However, the CCIs and associated redevelopment discourse still dominates city, and increasingly town, planning and expectations, often irrespective of any critical mass of such industries.

In the context of this article, heritage is defined as something externally attributed, that is classified, listed and maintained by national or international bodies such as Historic England or UNESCO. This is not exhaustive of the meanings or values of heritage and is by no means uncomplex. What is constituted as heritage and by whom is subject to all manner of negotiations and contestations which this paper does not cover (see Harrison Citation2010 for a discussion of world heritage; Smith Citation2006 and the discussion of heritage as externally attributed and curated; Harvey Citation2001 and heritage as a negotiated product of its time). As Harrison comments: ‘For every object of tangible heritage there is also an intangible heritage that ‘wraps’ around it the language we use to describe it’ (Citation2010, 10). Within this, and especially in relation to national and world heritage, there is a tension between who defines, participates in or accesses heritage in both its tangible and intangible forms (see Beardslee Citation2016 and the discussion of local practices). Beyond the intangible memories and practices bound up with physical space, there are also complexities relating to those excluded from or represented within it.

Governance is here understood as a term for and means of defining, describing and analysing processes and frameworks in relation to specific subjects or policy fields, broadly defined as ‘the co-ordination, regulation, or steering of affairs between actors’ in a specific sector or place, such as urban governance (Obeng-Odoom Citation2010, 204; see also Alasuutari Citation2015; Hall and Taylor Citation1996). Within this definition, governance encompasses the relationships across sectors and networks of actors within the governance process. As Söpper (Citation2014) stresses, there is a need to understand not only the structures of governance and their constituent parts but also the collaborative processes themselves, an identification and analysis of why actors collaborate and the rationale for networks (Citation2014, 57). This may include the role of specific people or functions – see for example Jayne’s (Citation2012) discussion of democratically elected mayors and urban governance, or the role of individualism and leadership (see Peck Citation1995; also, for geographical relevance, Cocks Citation2013). More specifically in relation to culture, Baltà Portolés, Čopič, and Srakar (Citation2014) explore the notion of cultural governance, suggesting that the concept ‘defies precise definition’ (183) and that the exploration of it requires a multidisciplinary approach, mainly due to the fact that it crosses a number of different theoretical areas. Alongside the creative industries discourse they also identify a shift in the cultural policy paradigm (and with it potential consequences). In relation to culture and cities, they highlight the increasing complexity of cultural governance, wherein cultural policy and decisions making processes are tied to the economic (see also Sacco, Tavano Blessi, and Nuccio Citation2009).

In order to undertake a multi-stakeholder cultural governance analysis that reflected these complexities, there was a need to explore and expand upon the perspectives of those within the governance structure itself, via qualitative network mapping in some form (see Oancea Citation2011; Oancea, Florez Petour, and Atkinson Citation2017; Wheddon and Faubert Citation2009). After exploration of the key sectors that had been involved in both the initial Liverpool 08 bid as well as an overview of contemporary active stakeholders within the city and city region, the cultural governance ecosystem was defined for this research as being constituent of Business and Economy, Government and Policy, University and Research, Arts and Cultural Organisation and Civil Society/ Community Groups (see also literature on the quadruple helix and co-production models in terms of defining stakeholders and understanding processes and flows e.g. Colapinto and Porlezza Citation2012; Carayannis and Campbell Citation2009). These sectors and stakeholders often merged and were not exhaustive of the different actors and organizations. The majority were involved in the ‘08 bid or events, however, the workshops purposefully included participants who had not been involved in these in order to encompass contemporary perspectives that were less likely to defend or contest certain positions or perspectives. This was an important factor, as several participants had very strong and long-held opinions on ECoC.

In terms of stakeholders, sectors and mapping participants it is important to note that, inevitably, several shifts had taken place across the decade in terms of regional and national governance, austerity and funding cuts to city councils. The ECoC year had coincided with the culmination of vast cultural and entertainment infrastructural regeneration such as the opening of the Liverpool One shopping centre and the Liverpool Arena and Convention Centre 2008. Key economic organizations during the bidding process shifted in name or merged in function – for example the Arts, Culture and Media Enterprise, The Mersey Partnership and the North West Regional Development Agency no longer exist, merging instead into organizations such as Liverpool Vision, or replaced by new structures such as the Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP). The election of a city mayor in 2012 was followed in 2017 by that of a Metro Mayor for the devolved Liverpool City Region (LCR). Some networks that were part of ‘08 demonstrated a continuity, e.g. LARC (Liverpool Arts Regeneration Consortium), COol (Creative Organisations of Liverpool, developed from SMAC, Small and Medium Arts Collective), both discussed below and LCC’s Culture Liverpool department. LCC had set up the Liverpool Culture Company to co-ordinate and deliver ECoC (as the managing and commissioning body). The Culture Company was replaced by Culture Liverpool in 2009.

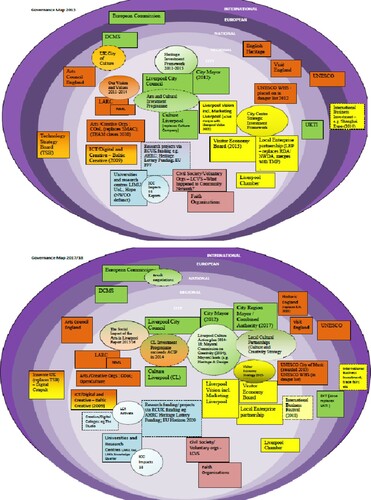

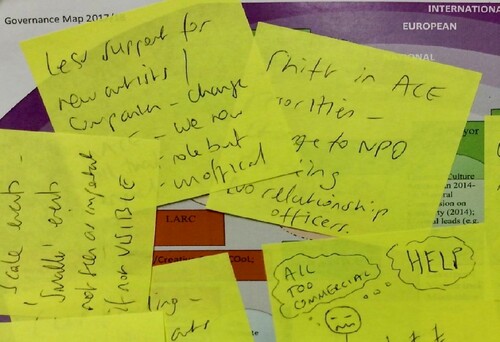

Three ‘snapshot’ map visualizations were created for the workshops – 2008, 2013, 2017/18 (see Image 1). These included organizations, events, policies or networks within the local, regional, national and international scale. These were in no way complete, rather they were merely intended to initiate debate around what or who might be missing. In addition to group discussions, participants were asked to contribute post-it notes highlighting any key shifts or concerns and to draw their own network maps noting any details specific to their sector or experience that were not covered in the workshops (see image 2, example of a network map drawn by the participant; image 3, post-it notes placed on the map) ( and ).

A total of 8 mapping workshops were undertaken in 2018, with a total of 44 participants drawn from the identified ecosystem. Of these, three took place at the University of Liverpool. These included: Liverpool Local Enterprise Partnership; MerseyCare (National Health Services Foundation); Liverpool Bid Company, Liverpool Arena Conference Centre; Baltic Creative CIC; the Fabric Quarter development; local universities (Liverpool Hope University, John Moores University, University of Liverpool); British Music Experience; Dadafest, a disability arts organization. Two arts and culture sector-specific workshops took place within prescheduled meetings. The first was a LARC meeting where most of the city’s larger arts and cultural organizations were present (the Bluecoat Gallery, Everyman and Playhouse Theatres, National Museums Liverpool (NML), Liverpool Philharmonic, Culture Liverpool, FACT, the Unity Theatre; Culture Liverpool also present). The second was at a COol meeting which included 18 participants drawn from smaller independent arts and cultural groups in the city and city region. Three individual workshops were undertaken at stakeholder sites (NML, LCC and Liverpool Vision).

An interview with Engage, a Liverpool Waterfront Residents Association and Community Interest Company (CIC) was also conducted in 2018 and is drawn upon. Participant observation at four city centre debates on the WHS (2017/2018), attendance at a ‘City Branding’ event (2017) and a large anniversary symposium (2018) are also explored here, as is a content analysis of the use of culture, and heritage, as a theme or as a thematic area within official strategy or policy documents from 2008 to 2018.

3. Overview: the ECoC legacy in the context of Liverpool

3.1 Evaluation and ‘08

In terms of ECoC, definitions and evaluations of impact and legacy can be problematic. Some measurable outcomes, for example, tourism, tend to peak and then even out, as Falk and Hagsten (Citation2017) discuss in relation to overnight stays in ECoC hosting cities (see also Jones and Ponzini Citation2018, 437). In general, there is, as Fitjar, Rommetvedt, and Berg (Citation2013) comment, a lack of rigorous evaluations of social outcomes across mega-events. Whilst hosting a mega-event such as ECoC may attract investments and improvements to infrastructure, it is the intangible legacy that is a main outcome – and this is, as Ferrari and Guala (Citation2017) discuss, far more difficult to identify or measure. Much also depends, as Németh (Citation2016) points out, on the governance networks (and power relationships) developed prior to and during the event.

For Liverpool ‘08 several claims were made, but little was – or can be – tangibly linked to the hosting of ECoC despite a large-scale Impacts ‘08 evaluation programme commissioned by the city council. Connolly (Citation2013) points out that projected economic returns for Liverpool 08 ‘were rarely questioned and Impacts ‘08 fails to present any detailed breakdown of the numbers or types of jobs created by Liverpool’s hosting of COC08’ (173). He argues:

Because the cultural planning model offered by Liverpool was theoretically incompatible it was, subsequently, practically undeliverable. Before the ‘Liverpool model’ can be assessed, it is essential that there is clarity as to what this ‘model’ actually is. Part of this is to clarify why Liverpool abandoned the approach which won the city its bid, and on which its initial planning was based. The academic study of Liverpool 08’s long-term benefit – Impacts08 – fails to do this in any way. (178)

Literature has in turn extolled and criticized the lead up to, hosting and evaluation of ‘08. Some take a critical approach in relation to the event and/or the evaluation (see Boland Citation2010); others utilize the event and indeed the Impacts 08 data as a gateway or overview (see Liu Citation2016) or expand on research undertaken during the Impacts’08 programme (see O’Brien Citation2010). Arguably the existence of a commissioned evaluation programme contributed to Liverpool ‘08 being discussed as something of its own case. Another reason for the highly case-study-centric approach is the perceived uniqueness of the case as a city that underwent many well-documented years of decline. Uniqueness and specificity are key to understanding processes, however, they should not add to an already problematic legacy narrative which, when based on exceptionalism, becomes difficult to constructively unpick. More recently and informatively, several studies have gone beyond this and drawn upon thematically relevant international case study cities (see Jones Citation2020, discussed below; Urbančíková Citation2018), thereby understanding and critiquing approaches, expectations or divergences across different examples.

3.2 Liverpool: city context

Most overviews of Liverpool begin with phrases similar to ‘once a great port city’. Its waterfront location on the North West of England made it a centre for commercial trading during the British Empire and this aspect of the city’s past forms the basis of its UNESCO World Heritage Status. The shipping industry shifted and declined in the twentieth century, and with it Liverpool’s docks and related industries. The city was bombed during the Second World War, with large-scale damage caused to several areas. There followed a well-documented post war decline: widespread unemployment, depopulation, riots and the move towards a proposed ‘managed decline’ of the Thatcher era. Through interventions by the then Minister for Merseyside various public-private interventions and regeneration initiatives ensued. These initiatives were a cornerstone in subsequent understandings of entrepreneurial regeneration in the city and region, based on property-led regeneration, competition and private investment. Large public funds were also funnelled into the city via European Council funding from the 1990s onwards (EU Objective II and Objective I funding).

Sykes and colleague’s (Citation2013) city profile of Liverpool explores the city within the context of national averages and indices of multiple deprivation. These highlight continuing challenges in terms of education, health and employment. The authors comment on the narrative of regeneration which ‘has become the city’s dominant, if seldom quantified or questioned, objective’ (Citation2013, 300). The emphasis on regeneration still prevails, overshadowing the need to develop existing sites or initiatives. As Mulhearn and Franco (Citation2018) in their paper exploring the boom in purpose-built student accommodation in Liverpool comment ‘Objective 1 status is no longer justified given that local GDP levels have closed on the EU average. In the EU’s terminology, the locality needs to now think about strategies to consolidate growth rather than engender recovery’ (Citation2018, 480).

Whilst Liverpool is no longer ranked as the most deprived local authority in England, in the 2019 indices of deprivation the city was the 4th most deprived local authority in England (by rank; 3rd by average score) and has the 2nd highest number of areas in the most deprived 10% (English Indices of Deprivation, statistical release, Sept 2019). Indices and national averages are important to situate and understand the challenges which Liverpool has faced and still faces. They are also key in assessing the veracity of the wider claims for cultural regeneration and impacts on participation, health, tourism and on wider economic activity. Here, as Boland (Citation2010) comments ‘notwithstanding a flood of investment and a period of economic growth Liverpool remains a polarised city on key socio-economic indicators (e.g. jobs, unemployment, incapacity benefits, housing and health’) which ‘fail to chime with the rhetoric of Liverpool as a renaissance city’ (636). This echoes Connolly’s (Citation2013) comments in relation to Glasgow’s ECoC hosting that ‘The espoused economic successes of Glasgow stand in stark contrast to contemporary health and poverty statistics which suggest that the approach adopted by the city has resulted in social and economic polarization’. (Citation2013, 169)

Imbalances in representation and power relationships furthermore negatively affect inclusive development strategies. In the case of Liverpool, these power relationships pre-dated ECoC and, in the words of one economic sector stakeholder consulted during the research workshops, fitted into ‘a dysfunctional space’. This is of course not singular to Liverpool. As Németh (Citation2016) points out:

A mega-event, and especially a cultural one such as the ECOC, has the potential to reach and mobilize various segments of the society and to bring to the surface diverse constellations of both openly declared and internalized power relations. (Németh Citation2016, 55)

3.3 Heritage, planning and the ‘Plaque on the Wall’

For Liverpool heritage necessarily includes colonial histories, the city having played a central role in British Imperialism and the slave trade- attested to in its UNESCO listing and explored in its museums, for example in NML’s International Slavery Museum and the Museum of Liverpool (see Arnold de Simine Citation2012 and Seaton Citation2001 for a discussion of heritage tourism in relation to slavery).

The Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City WHS, constituent of six areas and associated buildings in the historic centre and docklands, was listed by UNESCO in 2004 under Criteria II, II and IV (see http//whc.unesco.org/en/list/1150). The Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) of the site – what defines it as worthy of world heritage status according to UNESCOs criteria – is the significance of Liverpool as a major world trading centre and port in the eighteenth, nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. At the time of the ECoC bid, Liverpool’s WHS was on the ‘tentative list’ awaiting UNESCO designation. It was present in the ECoC bid document (Liverpool Culture Company Citation2004) as a case study and would go on to form a small part of the Liverpool ‘08 event programme (via the Creative Communities, Heritage and Welcome Team) with a number of educational and community-focused events. It was never embedded within the ECoC celebrations and did not involve local heritage actors in any significant way. As Jones (Citation2020), using case study comparison sites of heritage and ECoC in Genoa, Istanbul and Liverpool, comments

The city planned a massive city regeneration program around the event, but the city’s heritage, of which there is a significant amount, did not take on a central role and was largely left out of the narrative of the event.’ (115)

Often, as Jones and Ponzini (Citation2018) comment, there can be a disconnect between mega-event planning and urban heritage, partly due to the difficulty in merging the two policies, with conflicting goals and ‘certain tunnel vision in both fields’ (442/3). In Liverpool’s case, there was an existent complex issue of cultural heritage buildings and sites and regeneration. Indeed, it commenced soon after the Second World War. As Rodwell points out there was

Disuse and decay in the historic docklands, untreated bomb damage, and planning blight resulting from misguided and destructive redevelopment schemes combined by the 1990s to leave a legacy of serious scars and lack of coherence in the city’s urban geography. (Citation2014: 22)

fiercely contested demolition of a pre-First World War cinema front age and neighbouring buildings also of architectural interest (…) Other objections include the potential for PBSA to undermine the aesthetics of an area that still retains a number of notable nineteenth century buildings that are slowly being brought back into use. (Citation2018, 489)

It has been reported several times that the city’s major has referred WHS status as a plaque on the wall, or, as in the below newspaper reports written some four years apart, a certificate in the town hall:

Cllr Anderson made clear his priorities for 2012. He said: “Turning Peel Holdings (the developer) away doesn’t say to the world that Liverpool is a thriving modern city. It says we’re a city that is stuck in the past (…) The Lib-Dems would turn away 20,000 jobs and £5bn of regeneration, all for the sake of a certificate on the wall in the Town Hall. I say that’s madness. Whatever happens in 2012, let me be absolutely clear about one thing: we will back Liverpool Waters. (Liverpool Echo Citation2012)

The mayor of Liverpool has dismissed the concerns of “luddite” campaigners who warned a new development could cost the city its UNESCO world heritage status, claiming a “certificate on the wall” did little to boost the area’s prospects. (Perraudin Citation2016)

It should be noted though that whilst the waterfront development plans were the problematic aspect (or outcome) there were issues with the initial listing (for a discussion of this, see Rodwell Citation2008; Gaillard and Rodwell Citation2015) and with the communication of the site’s importance locally. A report conducted in 2013–2014 (ICC Citation2014) found that the site was neither locally embedded (its WHS values were poorly communicated) nor was it valued or marketed by the city. The lack of communication is significant. As Schoch (Citation2014), in relation to the delisting of the Dresden Elbe Valley, comments there is a need for implementation and co-ordination of the meaning and requirements of the UNESCO convention across all levels. This is something that never happened in Liverpool.

4. From 08 to 18: findings from the Qualitative data

4.1 Whose World Heritage? Discussions around delisting

In the mapping workshops, one cultural stakeholder commented that WHS designation: ‘was in the long term of things possibly more important than being the ECoC but it was seen as politically dispensable until recently’. This recent shift towards some sort of action or response only occurred when the WHS faced de-listing.

Engage Liverpool, the aforementioned resident’s association, who as Speake and Pentaraki (Citation2017) contend have ‘an important and to-date, under-reported, story to tell of the encouragement and facilitation of city centre residents’ voices’ (46), was central in highlighting the need for action. Under the title ‘A Status Worth Fighting For’ they staged three seminars in the city in 2017 (followed by three more in 2018). Key UNESCO representatives were invited (UNESCO’s voice had until then not been heard in the city), alongside local policy makers, academics and property developers. Also present were representatives or examples from other WHS heritage sites. The seminars, each held in buildings within the WHS, highlighted the fact that until this point little to no open discussion had taken place. Questions from the public were invited and in the first seminar (Oct 2017) the first question posed to the panel asked why the council allowed development to go ahead even after UNESCO’s 2012 warning (to which the councillor responded that for a city that had witnessed several years of economic decline the old buildings represented a success and that there was a need to try and build that again in a new way). Another local resident commented that she didn’t understand why ‘generic, glass fronted’ buildings were being built, instead she wanted ‘people to come to Liverpool and know they are in Liverpool’. Throughout the event attendees were given time to talk to each and share their thoughts– these ranged from concerns about perception of the city through to the impact of the waterfront development on the wider environment. There was, however, little to no coverage of the seminars in the local press.

The LCC did respond to the threat of de-listing via the appointment of a ‘World Heritage Taskforce’, a ‘Mayoral Lead for Heritage’ and the submission of a Desired State of Conservation Report (DSOCR) to UNESCO. Based on the DSOCR, the 42nd Session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee decided the site would not be delisted, it would however remain on the World Heritage in Danger list.Footnote3 The DSOCR had promised a new interpretation and communication strategy, measures to reinforce planning permission procedure, a ‘skyline’ policy and, crucially, the increasing engagement of civil society, via Engage Liverpool CIC and Merseyside Civic Society. It should be noted that in the UNESCO draft decision it was stated that whilst there was a positive move to safeguard the site, several measures in the DSOCR were not complete or relied on documents still in preparation (see UNESCO Citation2018, 4–7). Whilst these did suggest some shifts, they do not appear to have fundamentally altered the city council’s actions or perspectives. Plans remain in place for the building of a stadium on the waterfront which would still present issues in terms of the long-term fate of the WHS.

4.2 A world city? Enduring narratives of competition

In LCC and LCR documents, statements and presentations after ECoC (2008–2018), there remained a strong emphasis on how the city must become a more outward-looking international place rather than concentrating on local issues. Here world heritage, and other designated heritage buildings, are framed as a local or internal issue, the concerns of ‘luddite’ campaigners (as in the above-cited newspaper). Heritage becomes valuable only when situated within the economy, else it remains seen as something that won’t yield. A world city is in effect here purely understood as one which invites international investment and development.

Across several documents from 2008 to 2018, there is a consistent use of the notion of a global or world city, at times as a preferred or binary option i.e. the city sees opportunities and its role as more international than national. Keywords replicate those made in strategies and publications from bid to hosting year and include repetitions of phrases such as ‘global city’ ‘international’ ‘world city’ ‘ambitious in focus’ and ‘Liverpool as destination’.Footnote4 This was further explored in a city branding exercise that took place in 2017–2018 which suggested that ‘The narrative should also recognise and reflect the extraordinary pace and scale of the changes taking place in the global economy - and show that Liverpool is at the forefront of many of them’. (Heseltine Institute, Liverpool Branding Report to Marketing Liverpool Citation2016, 6)

Comments made by LCC and Culture Liverpool representatives in focus groups undertaken in 2016 also underlined the opinion that ‘Liverpool is its own thing’ and that the city is internationally known and there is no need for comparison with other U.K. cities.Footnote5 Similarly, a key LCR representative interviewed in 2018 in relation to the Liverpool 08 anniversary commented: ‘we’re a global brand; an international player’ and that there is a need to ‘set ourselves against what’s happening in Rome, Barcelona – not down the road’ (Workshop, 2018). This is at odds with a more contemporary regional development narrative that understands inclusive development beyond the city centre and periphery. Distinctiveness is conflated with marketability rather than embedded internal (local) value and assets. Here the city’s approach is in some ways frozen in time and remains bound to the ECoC bid (and the decades before) where city competition and redevelopment were seen as the only way forward, unheeding of Pratt’s (Citation2011) warning to cities: ‘to escape from the limitations of ‘cookbook’ approaches to creative cities based upon narrow branding or place marketing (…) consider instead a more nuanced approach that is sensitive to local cultures and differences’ (Pratt Citation2011, 123).

4.3 The ECoC legacy narrative

Culture is the city’s USP [Unique Selling Proposition] and has made Liverpool globally famous (…) It is the rocket fuel for regeneration. (LCC, Inclusive Growth Plan Citation2018, 81)

WeFootnote6 made culture the driver for regeneration and development so we instantly connected culture to the market economy (…) we saw culture through the prism of ‘how can we get more investment?’, with the discussion about sustainability or what was best never really taking place. (Community Stakeholder, Workshop 2018)

The balance between the social and economic since 08, a lot of these organisations are economic outward facing organizations yet actually ECoC was about creating more opportunities for the 3rd party social sector that I think was probably closer in 08 and now is wider. If ‘08 was all about these organisations (…) you would hope that by 2013 those parts of the city that were more disaffected before 08 would have become more integrated, empowered within that space but they’ve probably become less empowered, less relevant in that space. (Economic Organisation Stakeholder, Workshop 2018)

It’s that view, isn’t it, that culture is the rocket fuel of regeneration, so we keep getting told, which is great and we have big events but actually the grass roots in the city and the cultural organisations where’s the leadership for them and where’s the support for them?. (Mapping Workshop 2018)

To stay ahead, Liverpool needs to continually renew its offer and sustain investment in its heritage and visitor assets, deliver transformative infrastructure projects and innovative cultural programming. (LCC, Inclusive Growth Plan Citation2018, 82)

Related to this, a contrasting issue across all workshops was the role of large events within the city’s cultural offer and strategy development and a perceived lack of support for grass roots organizations. For several community artists and cultural groups, there was a shared concern that funds might have instead been steered towards more local or potentially more lasting initiatives. This was at the time also framed by the closure of Hope St, a community arts venue that had formed the original meeting place for COoL (at that point SMAC) during 2008. One example of this can be seen in the individual post note exercise undertaken in the COol workshop. Here a local arts stakeholder wrote: ‘Commercial big scale events – ‘smaller’ events not then as important if not VISIBLE’; ‘Local Authority Arts Officers being cut; little arts commissions from the city/less open calls’ (Image 4) ().

For LCC and Culture Liverpool representatives, the focus on large events is presented as positive. It is seen as proof of the city’s confidence in bidding for and hosting large-scale events or awards and building on ECoC experience and networks. The words ‘greater confidence’ are peppered across interviews with LCC stakeholders, drawing upon their expertise in the production and delivery of large events. The city’s top-down event-led focus is perceived by other stakeholders as more problematic. In a diplomatic exploration of this, National Museums Liverpool (NML) pointed out that in the Inclusive Growth Plan there was no real mention of the museums (other than a blockbuster Terracotta Warriors exhibition held in 2018). They suggested that in addition to one off or annual events the city should highlight the constant presence of the museums that is there for visitors as well as local communities. Others were less diplomatic. Referring to the city’s approach as ‘events as strategy’, several stakeholders – from across cultural and economic organizations – criticized the emphasis on sourcing external companies to provide large scale events. Referring to the ‘Giants’ spectacle (a popular large-scale marionette parade that was held in the city in 2012, 2014 and then in the anniversary year 2018) one stakeholder commented:

You can’t just keep getting the f***ing Giants back year after year and saying that’s what we do, that’s what Liverpool’s famous for. How long will that last for until the penny drops that anybody that has money can buy that stuff in. (Mapping workshop, 2018)

5. Conclusion: ‘It’s very interesting to me, what have we really become since 08?'

This question, posed during one of the research workshops, moves the article towards a reflective conclusion that returns to the issue of legacy narratives. In 2006, an audit commission report into LCC Cultural Services referred to an uncertain future, concluding that cultural planning was dominated by ECoC. It warned that it was not clear what the city council and their partners meant by ambitions to be ‘world class’ or a ‘premier EU city’ and found that ‘within the cultural programme there is a tension between the large scale ‘wow’ events and the need to tackle the multiple causes of deprivation at local level’ (Audit Commission Report Citation2006: 36). Post ECoC these concerns not only remain, they have become further embedded.

The ten-year anniversary of Liverpool ‘08 might have presented an opportunity for a critical reappraisal, coinciding as it did with the proposed delisting of the UNESCO site, concerns about increased student accommodation building and associated issues confronting historic buildings, the loss of several community arts sites and the continuing challenges of deprivation framed by extensive funding cuts. Instead, older and to a large extent unsubstantiated claims were showcased. A lack of tangible evidence was deftly overlooked in the celebrations and symposium referred to at the beginning of this article, with statements such ‘swagger’, ‘renaissance’ or ‘city confidence’ reinforcing how the preferred city narrative having long since prevailed in the public discourse at the expense of other evaluations. Two years later, there is seemingly nothing that this ‘swagger’ and the ‘rocket fuel’ cannot be said to remedy.Footnote7 A focus on visitor economy or ‘wow’ events that fail to take into account the different meanings and values of the city’s embedded tangible and intangible heritage was further illustrated in July 2020 when the council approved plans for a city centre zipwire ride that resulted in opposition from several figures from cultural, heritage and community groups on the grounds that it would ‘mutilate’ the site and would cross several memorial sites and reflective spaces, in effect constituting a move towards ‘Disneyfication’.Footnote8 There remains a focus on development despite rather than with the urban heritage site. This is not singular to Liverpool, of course. As Jones and Ponzini (Citation2018) suggest, there is too great a distance in both research and policy between mega-event studies and heritage, despite an increased overlap across the two and urgency for discussion and action. The use of mega-events as an economic and touristic intervention is also not singular to Liverpool. However, the continuing use of an ECoC success narrative – and with it an explicit reliance on and expectation of culture led (re)development – is embedded within the city’s approach.

At its heart the above question ‘what have we really become since ‘08’ must remain a learning process for all cities hosting large scale events such as ECoC. A focus on the often already embedded expectations and resultant limitations of measuring impact is necessary, as is the issue of comparison. A recognition that being site-specific remains important, but that this must go hand in hand with the need for a dialogue that goes beyond notions of competition towards one that preferences shared learning rather than the promise of replicating of a perceived success. How other ECoC hosting cities utilized their heritage or foregrounded more democratic local networks is essential here not to provide templates, but to open up discussions and challenge or amplify narratives post event (see comparisons by Jones Citation2020; Fitjar, Rommetvedt, and Berg Citation2013, both discussed above, see also Öztürk and Terhorst Citation2012 in relation to tourism). The espoused success of Liverpool ‘08 and resultant propagation of a top down ECoC legacy narrative damaged a more multifaceted engagement with built heritage and with the communities and practices associated with it. This was consolidated by an initial lack of wider contextualization of the event or the selection of given effects rather than others. A blinkered emphasis was placed on an ongoing city renaissance, one which is always in progress and as such never fully assessed. From large-scale tourism-focused cultural events through to controversial property-led investment strategies, the ECoC legacy narrative was used to capitalize on the buzzwords of heritage and culture whilst simultaneously attempting to reduce them to a binary choice between progress and preservation.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank colleagues at the Institute of Cultural Capital (ICC) where this research was undertaken and funded. It formed a thematic part of a larger study, with other team members exploring different themes in relation to the decade since Liverpool 08. No final reports have yet been published at the time of writing. This paper only discusses findings from the Cultural Governance and Heritage and Planning thematic projects which were undertaken and analysed by the author, it does not draw upon any other results.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Interview with a Liverpool Community Residents Association stakeholder, 2018

2 See the following for the use of these phrases, written at the time of the 2018 event https://www.cultureliverpool.co.uk/liverpool2018/culture-the-catalyst-of-liverpools-re-introduction-to-the-world/ and https://www.cultureliverpool.co.uk/news/liverpool-2018-ten-years-in-the-making/

3 see http://whc.unesco.org/en/sessions/42com/ for details of this meeting. Since writing this article the UNESCO World Heritage Committee met in July 2021 and made the decision to delete the Liverpool WHS- see https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/2314/. This development occurred during final corrections of the article and could no longer be included in the discussions.

4 Documents consulted include: LCC (2008) Cultural Legacy Scrutiny Panel; Liverpool First/LCC (2010) Liverpool Cultural Strategy Delivery Plan: 2010–2014 Stakeholder Summary; LCC (2011) Vision aims, priorities and values: Our Vision; LCC (2012) Report to Select Committee (Culture and Tourism) Cultural Strategy 2012/13 (LCC, committee meeting 19/06/ 2012); LCR/ LEP (November 2014) Visitor Economy Strategy and Destination Management Plan; Culture Liverpool/LCC (Undated) Liverpool Culture Action Plan 2014–2018; LCC (October 2017) Ten Streets Supplementary Planning Document; LCR (Citation2018) Culture and Creativity Strategy Framework (Draft); LCC (March 2018) Mayor of Liverpool Inclusive Growth Plan

5 Focus group /Interview not conducted or planned by the author. Full recordings and transcription were accessed as part of this research.

6 Here the stakeholder is referring to the city as ‘we’

7 See comments made, at the height of the Covid pandemic, by Culture Liverpool https://www.themj.co.uk/Liverpool-has-come-out-fighting-on-culture/218279

8 See, for example, news coverage of this https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-merseyside-53516228

References

- Alasuutari, P. 2015. “The Discursive Side of New Institutionalism.” Cultural Sociology 9 (2): 162–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975514561805

- Arnold de Simine, S. 2012. “The ‘Moving’ Image Empathy and Projection in the International Slavery Museum, Liverpool.” Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society 4 (2): 23–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.3167/jemms.2012.040203

- Audit Commission Report. 2006. Local Government Service Inspection Report. Cultural Services LCC.

- Baltà Portolés, J., V. Čopič, and A. Srakar. 2014. “Literature Review on Cultural Governance and Cities.” Kult-ur 1 (1): 183–200. doi:https://doi.org/10.6035/Kult-ur.2014.1.1.9

- Beardslee, T. 2016. “Whom Does Heritage Empower, and Whom Does it Silence? Intangible Cultural Heritage at the Jemaa el Fnaa, Marrakech.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 22 (2): 89–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2015.1037333

- Boland, P. 2010. “‘Capital of Culture—you Must be Having a Laugh!’ Challenging the Official Rhetoric of Liverpool as the 2008 European Cultural Capital.” Social & Cultural Geography 11 (7): 627–645. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2010.508562

- Carayannis, E., and D. Campbell. 2009. “‘Mode 3’ and ‘Quadruple Helix': Toward a 21st Century Fractal Innovation Ecosystem.” International Journal of Technology Management 46 (3–4): 201–234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2009.023374

- Cocks, M. 2013. “Conceptualizing the Role of Key Individuals in Urban Governance: Cases from the Economic Regeneration of Liverpool, UK.” European Planning Studies 21 (4): 575–595. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.722955

- Colapinto, C., and C. Porlezza. 2012. “Innovation in Creative Industries: From the Quadruple Helix Model to the Systems Theory.” Journal of the Knowledge Economy 3: 343–353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-011-0051-x

- Connolly, M. 2013. “The ‘Liverpool Model(s)’: Cultural Planning, Liverpool and Capital of Culture 2008.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 19 (2): 162–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2011.638982

- Degen, M., and M. Garcia. 2012. “The Transformation of the ‘Barcelona Model’: An Analysis of Culture, Urban Regeneration and Governance.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36 (5): 1022–1038. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01152.x

- EU Commission. 2020. “European Capitals of Culture (Factsheet).” https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/creative-europe/sites/default/files/2020_cult ecoc_factsheet_12.08.20_en.pdf

- Falk, N., and E. Hagsten. 2017. “Measuring the Impact of the European Capital of Culture Programme on Overnight Stays: Evidence for the Last two Decades.” European Planning Studies 25 (12): 2175–2191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1349738

- Ferrari, S., and C. Guala. 2017. “Mega-Events and Their Legacy: Image and Tourism in Genoa, Turin and Milan.” Leisure Studies 36 (1): 119–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2015.1037788

- Fitjar, R., H. Rommetvedt, and C. Berg. 2013. “European Capitals of Culture: Elitism or Inclusion? The Case of Stavanger2008.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 19 (1): 63–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2011.600755

- Flew, T., and S. Cunningham. 2010. “Creative Industries After the First Decade of Debate.” The Information Society 26 (2): 113–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01972240903562753

- Florida, R. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class: and how It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community, and Everyday Life. New York: Basic Books.

- Gaillard, B., and D. Rodwell. 2015. “A Failure of Process? Comprehending the Issues Fostering Heritage Conflict in Dresden Elbe Valley and Liverpool Maritime Mercantile City World Heritage Sites.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 6 (1): 16–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1179/1756750515Z.00000000066

- Hall, P., and R. Taylor. 1996. “Political Science and the Three new Institutionalisms.” Political Studies 44 (5): 936–957. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00343.x

- Harrison, R. 2010. “What is Heritage?” In Understanding the Politics of Heritage, edited by R. Harrison, 5–42. Manchester: Manchester University Press in association with the Open University.

- Harvey, D. 2001. “Heritage Pasts and Heritage Presents: Temporality, Meaning and the Scope of Heritage Studies.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 7 (4): 319–338. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13581650120105534

- Heseltine Institute. 2016. The Liverpool Brand, What is it and why does it Matter? https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/media/livacuk/publicpolicyamppractice/Liverpool,Brand,Report.pdf

- Hesmondhalgh, D., and A. Pratt. 2005. “Cultural Industries and Cultural Policy.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 11: 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10286630500067598

- Institute of Cultural Capital. 2014. Heritage, Pride and Place. Exploring the contribution of World Heritage Site status to Liverpool’s sense of place and future development. http://iccliverpool.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/ICC-WHS-FINALREPORT.pdf

- Jayne, M. 2012. “Mayors and Urban Governance: Discursive Power, Identity and Local Politics.” Social & Cultural Geography 13 (1): 29–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2011.635800

- Jones, Z. 2020. Cultural Mega-Events: Opportunities and Risks for Heritage Cities. London: Routledge.

- Jones, Z., and D. Ponzini. 2018. “Mega-events and the Preservation of Urban Heritage: Literature Gaps, Potential Overlaps, and a Call for Further Research.” Journal of Planning Literature 33 (4): 433–450. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412218779603

- Lazzeroni, M., N. Bellini, G. Cortesi, and A. Loffredo. 2013. “The Territorial Approach to Cultural Economy: New Opportunities for the Development of Small Towns.” European Planning Studies 21 (4): 452–472. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.722920

- LCR. 2018. Culture and Creativity Strategy and Framework Draft for Consultation. https://www.liverpoolcityregion-ca.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/DRAFT_LCR_Culture_Creativity_Strategy.pdf

- Liu, Y. 2016. “Event and Quality of Life: A Case Study of Liverpool as the 2008 European Capital of Culture.” Applied Research Quality Life 11: 707–721. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-015-9391-1

- Liverpool City Council. March 2018. Mayor of Liverpool Inclusive Growth Plan- A Strong and Growing City Built on Fairness. https://liverpool.gov.uk/council/strategies-plans-and-policies/inclusive-growth-plan/

- Liverpool Culture Company. 2004. The World in One City (ECoC Bid Document).

- Liverpool Echo. 2012. Liverpool Council Leader Joe Anderson says City Would Sacrifice World Heritage Status for Liverpool Waters Scheme in New Year report, Jan 2, 2012. https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/liverpool-council-leader-joe-anderson-3354111

- McCann, P., and R. Ortega-Argiles. 2015. “Smart Specialization, Regional Growth and Applications to European Union Cohesion Policy.” Regional Studies 49 (8): 1291–1302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.799769

- Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. September 2019. The English Indices of Deprivation 2019 - Statistical Release.

- Mulhearn, C., and M. Franco. 2018. “If you Build it Will They Come? The Boom in Purpose-Built Student Accommodation in Central Liverpool: Destudentification, Studentification and the Future of the City.” Local Economy 33 (5): 477–495. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094218792740

- Németh, A. 2016. “European Capitals of Culture – Digging Deeper Into the Governance of the Mega-Event.” Territory, Politics, Governance 4 (1): 52–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2014.992804

- Oancea, A. 2011. Interpretations and Practices of Research Impact Across the Range of Disciplines Report. Oxford: Oxford University.

- Oancea, A., T. Florez Petour, and J. Atkinson. 2017. “Qualitative Network Analysis Tools for the Configurative Articulation of Cultural Value and Impact from Research.” Research Evaluation 26 (4): 302–315. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvx014

- Obeng-Odoom, F. 2010. “On the Origin, Meaning, and Evaluation of Urban Governance.” Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift Norwegian Journal of Geography 66 (4): 204–212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2012.707989

- O’Brien, D. 2010. “‘No Cultural Policy to Speak of’ – Liverpool 2008.” Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events 2 (2): 113–128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2010.482271

- Öztürk, H., and P. Terhorst. 2012. “Variety of Urban Tourism Development Trajectories: Antalya, Amsterdam and Liverpool Compared.” European Planning Studies 20 (4): 665–683. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.665037

- Peck, J. 1995. “Moving and shaking: business élites, state localism and urban privatism.” Progress in Human Geography 19 (1): 16–46. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/030913259501900102

- Peck, J. 2005. “Struggling with the Creative Class.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 2 (4): 740–770. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2005.00620.x

- Perraudin, F. 2016. “Opponents of New Liverpool Tower Block are Luddites, says Mayor.” The Guardian, October 12. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/oct/12/opponents-of-new-liverpool-tower-block-are-luddites-says-mayor

- Porter, M. 1998. “Clusters and the New Economics of Competition.” Harvard Business Review 76 (6): 77–90. https://hbr.org/1998/11/clusters-and-the-new-economics-of-competition

- Pratt, A. 2010. “Creative Cities: Tensions Within and Between Social, Cultural and Economic Development. A Critical Reading of the UK Experience.” City, Culture and Society 1: 13–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2010.04.001

- Pratt, A. 2011. “The Cultural Contradictions of the Creative City.” City, Culture and Society 2 (3): 123–130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2011.08.002

- Rodwell, D. 2014. “Negative impacts of World Heritage Branding: Liverpool - an unfolding tragedy?” In Between dream and reality: Debating the impact of World Heritage Listing. Primitive Tider Special Edition. edited by Hølleland, Herdis and Solheim, Steinar, 19–34. Oslo: Reprosentralen.

- Rodwell, D. 2008. “Urban Regeneration and the Management of Change.” Journal of Architectural Conservation 14 (2): 83–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13556207.2008.10785025

- Sacco, P., G. Tavano Blessi, and M. Nuccio. 2009. “Cultural Policies and Local Planning Strategies: What Is the Role of Culture in Local Sustainable Development?” The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 39 (1): 45–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.3200/JAML.39.1.45-64

- Schoch, D. 2014. “Whose World Heritage? Dresden’s Waldschlößchen Bridge and UNESCO’s Delisting of the Dresden Elbe Valley.” International Journal of Cultural Property 2: 199–223. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S094073911400006X

- Seaton, A. 2001. “Sources of Slavery-Destinations of Slavery.” International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration 2 (3-4): 107–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1300/J149v02n03_05

- Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. New York: Routledge.

- Söpper, K. 2014. “Governance and Culture – a New Approach to Understanding Structures of Collaboration.” European Spatial Research and Policy 21 (1): 53–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.2478/esrp-2014-0005

- Speake, J., and M. Pentaraki. 2017. “Living (in) the City Centre, Neoliberal Urbanism, Engage Liverpool and Citizen Engagement with Urban Change in Liverpool, UK.” Human Geographies 11 (1): 41–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5719/hgeo.2017.111.3

- Sykes, O., J. Brown, M. Cocks, D. Shaw, and C. Couch. 2013. “A City Profile of Liverpool.” Cities 35: 299–318. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.03.013

- UNESCO. 2018. World Heritage 42 COM (WHC/18/42.COM/7A.Add), Paris 28th May 2018. http://whc.unesco.org/archive/2018/whc18-42com-7AAdd-en.pdf

- Urbančíková, N. November 2018. “European Capitals of Culture: What are Their Individualities?” Theoretical & Empirical Researches in Urban Management 13 (4): 43–55.

- Wheddon, J., and J. Faubert. 2009. “Framing Experience: Concept Maps, Mind Maps, and Data Collection in Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8 (3): 68–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800307