ABSTRACT

In this paper, we identify the patterns of change agency in peripheral regions and the forces shaping them. The following are the main research questions: (a) what are the patterns of local change agency like in peripheral regions and (b) what causes patterns of local change agency? We seek answers to these questions by carrying out a detailed analysis of trinity of change agency in Lapland, Finland. We show how the pattern of it evolves in time, and how, in a crisis, new modes of agency surface and key actors need to learn new ways of intervening. Change agents need to build confidence and mobilize resources, capabilities and power. The empirical study follows a longitudinal single case study design. The empirical data were based on 15 interviews of the national and local/regional development agencies as well as from firms and research/educational organizations. Additionally, the written material from the Internet, relevant journals, related newspaper articles and respective policy documents were analysed. The empirical analysis identifies the main phases of path development in Eastern Lapland, key actors in different phases and their agency.

1. Introduction

In this article, we aim to shed light on the factors that shape the patterns of change agency in regions. In other words, we aim to identify combinations of actors and their activities, which form regular, intelligible and discernible modes of agency typical for a place and time in question. Earlier studies show that patterns of agency differ significantly between cities and regions, being shaped, for example, by governance structures (Bellandi et al., Citation2021), informal networks (Potluka, Citation2021), history (Hidle & Normann, Citation2013) or politics (Sancino et al., Citation2021). How and why agency is different from place to place, from region to region and from city to city is a central question, with the research on various aspects of change agency mounting rapidly.

In recent years, economic geographers and regional development scholars have addressed increased attention to agency, the aim being to balance the overly structures-oriented research by finding ways to study the recursive relationship between structures and agency. Morgan (Citation1997) and Cooke (Citation1998) highlighted some time ago the importance of regional animateurs and networks, developing informal institutions for economic development. More recently, Isaksen et al. (Citation2019) distinguished system-level agency from firm-level agency, Huggins and Thompson (Citation2019) discussed the behavioural principles of agency and Moulaert et al. (Citation2016) presented a model aiming at integrating agency, structures, institutions and discourse. Additionally, place leadership has received more attention than ever (Collinge & Gibney, Citation2010; Beer et al., Citation2019) and studies focusing on the different dimensions of institutional agency have been increasing steadily (e.g. Benneworth et al., Citation2017).

Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) integrated three independent modes of change agency into an integrated theory – trinity of change agency. Trinity of change agency is a combination of innovative entrepreneurship (Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000), institutional entrepreneurship (Battilana et al., Citation2009) and place leadership (Collinge & Gibney, Citation2010). Beer, Barnes and Horne (Citation2021), for their part, integrated trinity of change agency with Moulaert et al.’s ASID model, constructing a three-dimensional model for a study of place-based industrial strategies and economic trajectories. In this article, we draw on the trinity of change agency while also being conscious of other forms of agency and acknowledging the presence and importance of maintenance agency and resistance to change as important forms of agency in regional development (Bækkelund, Citation2021; Bellandi et al., Citation2021).

As temporality has emerged as central in studies focusing on agency, we contextualize our search for patterns of agency in the literature on path development. Essentially, we are not aiming to contribute to the literature on path development but use it to position agency in the course in which a region is moving. In this way, we endorse Hassink et al. (Citation2019), who highlighted the need to explore how multiple actors construct development paths (see also Dawley, Citation2014).

The rapidly expanding body of path development literature has focussed mainly on core regions (Isaksen, Citation2015), while path development and related agency in peripheral regions has not received similar attention from scholarly communities (Isaksen & Trippl, Citation2017). Peripheral regions are not, by definition, embedded in agglomeration economies, the main economic clusters or sophisticated innovation systems found elsewhere (Isaksen & Karlsen, Citation2016). They therefore have difficulties connecting to the global economy and thus struggle to adjust to a changing economic landscape (Isaksen, Citation2015). Consequently, peripheral regions may be even more dependent on deliberate local/regional change agency than the growing core regions. In practice, they often struggle due to weakness, or the absence of it. However, peripherally located firms or local development agencies may be innovative and active in experimenting with novel ways of promoting economic development (Shearmur, Citation2015), but proactive agency to improve preconditions for future development is often fragile.

The main objective of the article is to identify the patterns of agency in peripheral regions and the forces shaping them. The research questions are as follows: (a) what are the patterns of local change agency like in peripheral regions and (b) what causes patterns of local change agency? We seek answers to these questions by carrying out a detailed analysis of path development and related agency in Eastern Lapland, Finland. Our research questions allow exploratory testing of the propositions embedded in the emerging trinity of change agency theory; heuristic propositions in an emerging research area do not allow straightforward verification of them. Instead, this study is an intensive endeavour to understand the dynamics of local change agency in the context of path development in a peripheral region.

2. Path development in peripheral regions

The concept of path development highlights how institutional and industrial structures shape regional development. From a locational perspective, peripheral regions are commonly located far away from main growth centres, and, from a relational perspective, peripheral regions are weakly connected to main business and knowledge hubs and policy shaping and making networks. From an economic perspective, peripheral regions’ innovation capacity is limited, as research and development (R&D) volumes are at a low level and support organizations are small and poorly resourced or located elsewhere (Tödtling & Trippl, Citation2005; Henning et al., Citation2013; Isaksen & Trippl, Citation2017). In other words, peripheral regions have organizationally thin, dysfunctional, or completely absent innovation systems (Tödtling & Trippl, Citation2005; Phelps et al., Citation2018), and often are dominated by resource-based industries. They are resource peripheries, regions and communities whose existence is based on the natural resources and their extraction and utilization (Neil & Tykkyläinen Citation1998). For all these reasons, processes of inertia at the system and firm levels shape development trajectories of peripheral regions (Phelps & Fuller, Citation2016). The emergence of self-reinforcing effects and historical contingency directs how technology, industry or regional economies evolve along one path but not another (Martin, Citation2010); actors are directed by the selective logic of past development dynamics (Augsdorfer, Citation2005).

Peripheral regions are trapped by their history, but, still, it would be important not to see them as negative mirrors of cities that grow on structures accumulated over time. Following Galster’s (Citation2018) propositions, we see peripheral regions as ‘demographically selective’ (population loss comprise of more advantaged households), ‘psychologically conservative’ (local people try to conserve their threatened resources), ‘dynamically nonlinear’ (socially problematic behaviours and residential disinvestment jump when population changes exceed thresholds), ‘asymmetrically scalable’ (for political, financial, physical and technological reasons), and ‘informally decentralized’ (local people supplement the shrinking services with other means) (Galster, Citation2018). Importantly, as Galster (Citation2018) also proposed, shrinking places are ‘minimally controlled’, as standard policy instruments are not enough to solve their problems.

For the above reasons, peripheral regions are often locked into their past paths, and need external investments to unlock them from their past paths (Isaksen, Citation2015). If the concept of path dependency leads us to look back in time, path development turns our gaze towards the future. Broadly speaking, path development is about the emergence and growth of new industries and economic activities in regions (MacKinnon et al., Citation2019). In other words, it is about intertwined and coevolving firms and support actors and institutions that are established and legitimized beyond emergence and are facing the early stages of growth and developing new processes and products (Steen & Hansen, Citation2018, p. 191; Binz et al., Citation2016). As Blažek et al. (Citation2020) remind, the path development literature has dealt mainly with, and actively conceptualized, positive development paths (upgrading, diversification or creation) (Grillitsch & Asheim, Citation2018), while many regions experience negative development trajectories. Many peripheral regions do not have the capacity to pursue path creation or significant unrelated path diversification (Isaksen & Trippl, Citation2017) but are trapped by downward spirals.

Blažek et al. (Citation2020) proposed three forms of negative paths. First, path downgrading refers to corporations and SMEs adjusting to changes in their markets by removing or reducing their R&D activities in the region. It may also be the outcome of what Blažek et al. (Citation2020) call re-specialization strategy, which involves businesses shifting to lower-cost production. The second downward path in the Blažek et al. (Citation2020) typology is path contraction, which refers to the shrinkage of a regional industry caused by lost positions and consequent pulling back from some market segments. In path contraction, key companies retain their core capabilities and innovative functions but become more specialized in segments where they are competitive, often in more low volume niches than previously. In essence, path contraction is about narrowing the product/service portfolio. Third, key economic activities in a region may relocate to more favourable locations (path delocalization), potentially leading also to further disinvestments and brain drain processes. Blažek et al. (Citation2020) argued that we should better understand negative path dynamics, as they initiate difficult-to-turn-around downward spirals, making the regional asset base less favourable for future higher-value economic activities and thereby severely damaging long-term regional competitiveness. The ‘booms and busts’ in resource peripheries are related to the fluctuation of the external demand and prices of the natural resources, disruptions in market access, transportation, and technologies, in addition to many other external factors also affecting other types of regions (e.g. Halonen Citation2019).

It is also important to scrutinize institutional path development, which provides the mindsets, normative expectations, playground and rules of the game for industrial path developments (Sotarauta & Suvinen, Citation2019). Institutional path development includes both regional and external influences, which are central in compensating for institutional thinness. As important are national-level policy interventions and support mechanisms, and organizational development in a region (Dawley et al., Citation2015; MacKinnon et al., Citation2019; Isaksen & Trippl, Citation2017; Vale & Carvalho, Citation2013). Drawing on Content and Frenken (Citation2016), Carvalho and Vale (Citation2018) maintained that ‘regions are more likely to move into industries to which they are institutionally related, namely as actors that can make use of previous arrangements and practices, and simultaneously face little resistance from incumbent industries’ actors and policies’.

3. Trinity of change agency

Agency is a process of acting and related roles, positions or functions. Giddens (Citation1984, p. 9) related agency directly to an individual actor by maintaining: ‘whatever happened would not have happened if that individual had not intervened’. We are not pushing that far but are interested in the capacity of individuals, groups of individuals and organizations to act intentionally and meaningfully for their regions and intended and unintended consequences of their actions (Gregory et al., Citation2009). We seek to identify ‘mindful deviations’ by agents (Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001). We also follow Huggins and Thompson (Citation2019; Citation2020), who see human agency as spatially bounded. They argue that ‘cities and regions themselves produce a spatially bounded rationality that determines the forms and types of human agency apparent in a given city or region’, and subsequently the nature of knowledge, innovation and development (Huggins & Thompson, Citation2019, p. 31). We are interested in how location in a peripheral region is bounding and shaping local change agency.

As path development is about change, change agency has adopted a central position in agency-oriented studies. However, as Bækkelund (Citation2021) and Jolly et al. (Citation2020) reminded, reproduction and maintenance are also playing central roles in regional development (Coe & Jordhus-Lier, Citation2011). Kurikka and Grillitsch (Citation2021) stated that reproductive agency is not only about resistance to change (Jolly et al., Citation2020), as it is often seen, but also includes activities having value for a region. Reproductive agency may trigger incremental changes, but its transformative change potential is limited (Kurikka & Grillitsch, Citation2021). Benner (Citation2021) summarized maintenance and reproductive agency as forms of stability agency. Moreover, it is important to acknowledge that various forms of agency coexist and may represent contradictory interests (Baumgartinger-Seiringer et al., Citation2020). Additionally, actors may take on different roles than their counterparts in some other regions; we should not associate certain roles to certain individuals or organizations without proper scrutiny (Sotarauta et al. Citation2021). Also, the roles actors are playing in a system may change in time. All in all, the rapidly emerging body of literature shows the many faces of agency in regional economic development and highlights the importance of shedding additional light on it in many different contexts.

In this article, we draw on trinity of change agency: innovative entrepreneurship, institutional entrepreneurship and place leadership (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). There is extensive literature showing that innovative entrepreneurship is a vital force of change (Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000; Audretsch et al., Citation2011). When pushing their own businesses forward, innovative entrepreneurs influence all path development types in a variety of ways (e.g. Foray et al., Citation2009; Feldman, Citation2014). Of course, multinational companies, small and medium-sized enterprises and micro enterprises come in many shapes, sizes and degrees of innovativeness. They play varying roles in local economies or global production networks (Fuller & Phelps, Citation2018), and therefore the category of ‘innovative entrepreneurship’ needs to be approached as a broad focusing device for more context-specific scrutiny of its manifestations in relation to a specific path and place. The same goes with institutional entrepreneurship, which Sotarauta and Mustikkamäki (Citation2015) concluded to be a multi-actor process in time. It is important to understand the actual mode of agency related to institutional entrepreneurship. It is about changing regulative, normative and cultural-cognitive institutions in a specific context, and thus it does not refer to public actors as such. Moreover, it is crucial to keep in mind that the entrepreneurial dimension stresses the risk-seeking and opportunity-searching nature of institutional entrepreneurship. It is not about a specific actor in specific region but intentions to change institutional arrangements, as new development paths call for institutional changes, involving removal of obstacles or laying the play-ground for something new. Therefore, the role of institutional entrepreneurship has been highlighted and investigated in many studies (Battilana et al., Citation2009). Institutional entrepreneurs work, in collaboration with other actors, to change normative, regulative and cognitive-cultural institutions for regional development (Sotarauta & Pulkkinen, Citation2011).

Regional path development is a multi-actor and multi-interest constellation, being characterized by fragmented rather than coherent processes (see Beer et al., Citation2020). Therefore, Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) added place-based leadership as the third mode of change agency in their theory. Place leaders orchestrate actions in complex networks, and, as Sotarauta and Beer (Citation2021) maintained, ‘pool competencies, powers and resources to benefit both the actors’ individual objectives and a region more broadly’ (see also Gibney & Nicholds, Citation2021; Hambleton, Citation2015). Place leadership aims to make sure that place-based intentions are identified, pooled and if possible, achieved. It resembles, for example, institutional leadership, which however is not by definition as tightly tied to place-based ambitions as place leadership is.

From the perspective of local and regional development, it is also important to differentiate between assigned and non-assigned leaders. Assigned leaders are granted the authority to exercise power on behalf of some collective to work for a place, while non-assigned leaders gain their leadership position without having formal power because of the ways other people respond to them. Non-assigned leaders seize the power despite their lack of institutional and/or resource power. To become a place leader, a formal leader with an assignment needs to aim to influence actors beyond the formal delegation and responsibilities, instead using the power and resources they possess, because of their formal position, to achieve a wider impact through, with and by other actors. In other words, they do what they are supposed to do, but they also consciously aim to reach beyond their authorization (Sotarauta, Citation2016) ().

Table 1. Three types of change agency in a nutshell (applying Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020).

4. Methodology, data, and the case

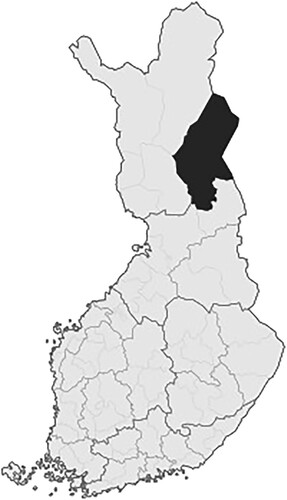

We scrutinize local change agency in Eastern Lapland, Finland. Eastern Lapland is one of Finland’s sub-regions and comprises five independent municipalities. The Finnish classification of regions recognizes 18 regions and 70 sub-regions. According to Eurostat, sub-regions are level 1 local area units (LAU1). We discuss local agency when referring to activities in our case-region, and regional when referring to the entirety of Lapland.

As this study is primarily about understanding the dynamics of agency over time, we follow a descriptive single-case study approach with instrumental and longitudinal design (Flyvbjerg, Citation2006; Klenke, Citation2008). Descriptive case studies are relevant when the research question requires a detailed and in-depth depiction of a social phenomenon (Yin, Citation2016). The instrumental case design is applied when the focus is on the dynamics of a given issue and the main ambition to increase general understanding of it (Klenke, Citation2008, 59). In other words, we are keen to identify the dynamics of local change agency and use a particular peripheral region in this effort. But, to some extent, we also have a sub-unit of analysis, a peripheral region tackling an industrial crisis. Hence, our case study is also embedded by nature, involving units of analysis at more than one level (Yin, Citation2016).

Krehl and Weck (Citation2020) argue that comparative case studies ought to meet the minimum standards better than often is the case, including solid theoretical framework and a careful case study selection being in sync with the theory, a well-set objective for comparison and the ambition to generalize. They argue further that increased transparency would support both academic quality and potential for policy recommendations. We endorse their arguments and emphasize the importance of publishing the theoretical and methodologal underpinnings as well as empirical results in several outlets to provide in-depth and versatile understanding what the study was about. This article presents the observations from one of the cases of an extensive comparative case study – Regional Growth Against All Odds (ReGrow) – that focused on statistically selected 12 case regions in Finland, Norway and Sweden. Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) constructed the theory, the methodology has been discussed in several articles (Grillitsch, Rekers & Sotarauta, Citation2021; Grillitsch et al., Citation2021; Sotarauta & Grillitsch, Citationforth.) and the empirical results of comparisons and individual case studies are being published when writing this article (e.g. Sotarauta et al., Citation2021; Grillitsch, Asheim & Nielsen, Citation2022; Grillitsch et al., Citationforth.; Kurikka et al. Citationforth.).

In this specific case study, the longitudinal approach led us to search for the schematic similarities and differences between patterns of change agency in different phases of path development in Eastern Lapland. We approached change agency as a nexus between sub-regional development paths and national/global forces and pressures. We first studied the case by collecting and analysing extensive secondary materials, such as relevant newspaper articles, earlier studies and relevant policy documents. Drawing on these secondary materials, we identified the main phases and features of the development path and outlined the patterns of agency for the second phase of the study. In the second phase, from March to December 2019, we carried out 15 semi-structured interviews in the case sub-region to inform us about the recent developments in Eastern Lapland (phases 2 and 3, see the next section), including a national-level policy maker and CEO of a major corporation. The interviewees represented local and regional authorities (8), firms (4), local media (1) and national-level organizations (2).

Eastern Lapland is in northern Finland by the Russian border (see ), with a population of 15,655 in 2020, having decreased by 32% from 2000 (StatFin, Citation2021). It is peripherally located far from the main cities of Finland. According to the Finnish spatial classification of rural areas (Suomen maaseututyypit, 2006), Eastern Lapland belongs to the category of ‘sparsely populated rural areas’. In the sub-region, there were three branch plants of major corporations, which were all closed and thus Eastern Lapland is one of those places, which has experienced the dark side of a local branch plant economy (Phelps, Atienza & Arias, Citation2018). In the 2020s, it does not have a high number of SMEs, and growth-oriented enterprises are especially few. Traditionally, small-scale operations (for example, reindeer herding and natural products) and large industrial corporations have been the main sources of livelihood in the sub-region. In the 2010s and 2020s, Eastern Lapland relies strongly on public sector employment, which accounted for 39% of all jobs in 2019 (30% in Finland) (StatFin, Citation2021). In addition, agriculture still plays a significant but decreasing role in employment, whereas forestry-related jobs have remained steady. The unemployment rate has been high, standing between 15% and 27% over the last 20 years, but showing positive development since 2016, when the number of jobs turned to growth after a long negative period (StatFin, Citation2021). The average education level in Eastern Lapland is significantly lower than the Finnish average. There are no higher education institutions in the sub-region, only secondary-level education; that is, upper secondary schools and a vocational school, which is a local unit of the regional Lapland Education Centre.

5. Formation of a regional development path in Eastern Lapland

In this section, which covers a period of approximately 60 years, we briefly describe the formation of regional development in Eastern Lapland. We divided the development path of Eastern Lapland into three main phases: the era of industrialization, the era of external shocks and the era of reproduction of the old path and new openings. In the analysis of change agency, we focus on the second and third phases, but as the first phase still shapes agency today, we also briefly describe its basic tenets.

5.1. The era of industrialization (from the 1960s to the first plant closure in 2002)

The industrialization of Eastern Lapland began in the 1950s and 1960s alongside state industrialization and regional development policy, which remained strong until the 1980s and, to some extent, the 1990s. Finland has had visible south/north and east/west dichotomies for centuries (Nenonen, Citation2018), with the Eastern and Northern parts of the country lagging. Regional policy has for a long time aimed at helping peripheral regions deal with the long distances to markets and an inadequate supply of skilled labour (Mønnesland, Citation1994). The era of industrialization in Eastern Lapland characterizes well the early regional policies in Finland. During this era, Eastern Lapland was the consistent target of regional policy subsidies, the aim of which was to promote industrialization and the construction of an industrial path, especially in forest-related industries, but also in other fields of economic activity.

The industrialization of Eastern Lapland began in the 1950s, when the State of Finland harnessed the Kemijoki River to produce hydropower and in 1965 established a state-owned pulp factory in Kemijärvi. It, and its various incarnations, became the economic engine of the sub-region, reflecting simultaneously the strong industrialization policy and the nature of Eastern Lapland as a resource periphery. The second wave of industrialization occurred in the 1980s, when Orion (pharmaceuticals) (1984) and Salcomp electronics (1985) began their operations in Eastern Lapland. The State of Finland subsidized the establishment of new plants, assisting corporations to change their ‘value capture trajectories’ (Coe & Yeung, Citation2015) to support the development of a peripheral region. These new industrial activities were not related to the natural resources of the sub-region, but they diversified the economic structure of Eastern Lapland. In the 1990s, electronics manufacturing grew with the rapidly expanding Nokia-led Finnish mobile phone industry. Nokia acquired Salcomp in 1983 (Salcomp, Citation2021), which employed (at most) approximately 800 people in Kemijärvi.

Finland experienced a fierce economic recession in the early 1990s (see Honkapohja & Koskela, Citation1999) and joined the EU in 1995; the consequent changes in regional policy were clear. Direct subsidies for industries, having been instrumental for Eastern Lapland, decreased, and the Finnish regional policy shifted to emphasize endogenous development, including a strong focus on innovation, technology and the competitiveness of regions (Tervo, Citation2005). A new programme-based regional policy changed the relational position of Eastern Finland, as the top-down regional policy structures had been one of its most important playing fields. The new regional policy was challenging for geographically peripheral places, as they did not have many local actors capable in exploiting the new modes of policy. In other words, the institutional path on which Eastern Lapland had been evolving for several decades began to change, with consequences surfacing later (Kurikka, Sotarauta & Kolehmainen, Citation2021).

This era was characterized by the steady construction of an institutional set-up for industrial path development, followed by the extension of attracted industrial activities. The forest/pulp, electronics and medicine manufacturing industries, as well as ski resorts, were established. The main causal drivers were the attraction of external investments supported by state subsidies, and the utilization of natural resources, hydropower, forests, minerals and northern scenery (tourism). The main activities were controlled primarily by the state and private corporations, with local actors responding actively to this positive industrial development.

5.2. The era of external shocks (plant closures from 2002 to 2008)

The beginning of the new millennium was characterized by path delocalization and contraction. Major corporations made decisions based on the market situation and cost-efficiency, resulting in the closure of the pharmaceutical (2002), electronics (2004) and pulp (2008) factories. The closure of the pulp mill was criticized at the time and later on, as the global demand for pulp-based new materials had risen. Additionally, the Sokli phosphate deposits were sold to foreign investors in 2007, sparking intense local criticism.

All in all, over 1,500 jobs disappeared from 2000 to 2010. Some positive developments also occurred that provided local actors with some hope for the future, but these were insufficient to compensate for the losses caused by the plant closures. The positive events included the opening of the Salla Border Crossing Point between Finland and Russia (2002), large investments in the Pyhä Ski Resort (from 2004 to 2010) and the airing of a popular TV series, ‘Taivaan tulet’ (‘The Fires of the Sky’), which achieved substantial national visibility and was filmed in Kemijärvi from 2005 to 2013. The development efforts in this era were mostly defensive and aimed at path continuation, resulting in path delocalization.

5.3. Reproduction of the old path and new openings (post plant closures, 2009->)

The closures of plants left a huge vacuum in Eastern Lapland (for more about the impacts of plant closures, see e.g. Tomaney, Pike & Cornford Citation1999; Beer, Citation2018; Beer et al. Citation2019). The sub-region became even more dependent on public employment, and its decreasing population became increasingly evident. As Eastern Lapland had been for a long-time home to large industries (relatively speaking), it did not have an established tradition of entrepreneurship, and the number of SMEs in the sub-region was low. A sawmill of Keitele Group Ltd (2014) and a refrigeration equipment manufacturer, Porkka Ltd (2015), located their activities in Kemijärvi, drawing on available premises and labour (Hautala, Citation2020). There were also indications of an emerging cultural industry – for example, the French-Finnish movie ‘Ailo’ was filmed in Eastern Lapland in 2018, and efforts have subsequently been made to market Eastern Lapland as a location for film production. The Sokli mine received an environmental licence in 2018, but opening of the mine has not proceeded. Tourism has the potential for growth, as other parts of Lapland have shown. The ski resorts received investments, year-round tourism became more popular, and the number of foreign tourists increased. All three ski resorts – Pyhä, Suomu and Salla – grew (Kurikka, Sotarauta & Kolehmainen, Citation2021).

In sum, the third phase was about post-industrial path delocalization, about a decreasing and aging population. The decay was caused by gradual transformation in the global demand and cost-structures for the main products of the three corporations (Orion, Salcomp and Stora Enso), leading them to change their strategies and to close factories in Eastern Lapland. The corporations moved production to cheaper-cost countries or reduced overall capacity. In 10 years, Eastern Lapland became trapped by its past path. Additionally, the formal systems of regional policy that had earlier created a way for Eastern Lapland to interact with national-level resource holders and decision-makers had changed, and thus local actors struggled to access national resources and wider influence networks.

6. Change agency underpinning key events

In this section, to dig deeper into the pattern of local change agency, we focus in more detail on specific events. The events describe distinctive characteristics of local trinity of change agency and its causal power (or lack of it) to path development. Instead of analysing changes in global production networks or the strategies of multinational enterprises, our main interest is to analyse what local actors attempted to do to counteract the effects of plant closures and shift onto a new path.

6.1. The closure of a paper mill

First, we focus on the decline following the closure of Stora Enso’s (a Finnish-Swedish corporation) paper mill in 2008 and efforts to continue the pulp path. The Stora Enso pulp mill was an essential part of the industrial identity of Kemijärvi.

Stora Enso used raw material from the region but also imported it from Western Russia. In 2007, the price of wood was high because of Russian wood tariffs. Moreover, and importantly, paper consumption had begun to decline globally. Stora Enso began to reduce capacities in several locations around the world. In Eastern Lapland, the mill had been in operation since 1965, employing 220 people in 2007; when including indirect operations like transportation and harvesting, the employment effects of the closure were approximately 1,000 people. Even years later, interpretations about the closure differ:

In print paper the market shrunk 7% a year in Europe … In regions where the demand drops, further investments are not profitable. And then the Russian wood tariffs and availability of Finnish wood … the purchase cost of lumber rose about 50–60% in six months … Altogether, the changes in the field of Stora Enso cost 16,000 jobs globally, of which 50% were in Finland. (a company representative)

The pulp mill fell, and it was incomprehensible because it was a unit that was making profits for the mother company, was energy self-sufficient and in the middle of growing raw material. State-ownership was 35% and the state did not even use its power to save the mill in this situation. And later, the director who made the closure decision admitted that it had been a mistake. (a national level politician from the region)

The closure generated a social movement called ‘Massaliike’ (‘Mass movement’) to protest the changes. The movement was led by the Chairman of the Municipal Board (a prominent formal place leader) and a few other leading actors. They were very visible and gained public sympathy in the national media. The core group also actively lobbied Stora Enso and Finnish ministers, as the state owned a large share of the company. In addition, the Municipal Council of Kemijärvi offered to buy Stora Enso’s facilities and machinery so that the manufacture of pulp could continue if a new entrepreneur could be located and attracted to Eastern Lapland. However, the defensive actions – reproductive agency aiming at short-term path continuation – did not change the outcome. Stora Enso did not reverse its decision, and the state did not intervene. To support the sub-region following the standard regional policy procedure, to release targeted funding the state designated Eastern Lapland as an ‘abrupt structural change region’. Over five million euros of state money, matched by the same amount from Stora Enso, were invested in an extra-regional company (Arctos Group Ltd) that promised to begin the manufacture of laminated beams in the vacant pulp mill space and to provide new jobs. However, the new company faced challenges from its onset, having difficulties launching its production and, in addition, receiving no support from the ‘mass movement’ people and the municipality, subsequently going bankrupt in 2013. The state also supported employment in the sub-region by establishing a national service centre of the Social Insurance Institution of Finland (2009) in Kemijärvi.

6.2. A new company and a plan to have a large-scale biorefinery

With the dust settling, a place leader – one of the lead actors of the mass movement – had as his ambition the boosting of a new beginning for the sub-region’s pulp industry. He began to work with his personal network, with the goal of establishing not a traditional pulp mill, but a large-scale biorefinery in the sub-region. The main premise was that the new mill should meet all the established contemporary standards for a circular bioeconomy. The main causal drivers were partially technological, as new pulp technologies had emerged and continuously evolved, and partially agential, as local actors had adopted a more proactive role and were looking for new opportunities and partnerships. Increasing global demand in emerging markets for new pulp-based materials provided local actors with opportunities.

The lead champion of the new mill had previously held a position as a forestry advisor in the Finnish Forest Center.Footnote1 In 2013, he (labelled a Forest Champion) conducted a small project intended to explore opportunities pertaining to Lapland’s forests, and calculations showed that there was indeed potential for a major effort in Eastern Lapland. Pulp researchers at Aalto University (Helsinki Metropolitan Area) joined in the planning of the new mill, their role being central in the plan to utilize a new kind of technology accompanied with a novel production method for generating higher-value bio-products. Consequently, Boreal Bioref Ltd was founded in 2016, with the ambition to generate approximately 200 jobs and over 1000 indirect jobs. Its founders were local actors, including the Forest Champion and a retired mayor/governor/parliament member. The municipal development company, Kemijärven Kehitys Oy (Kemijärvi Development Ltd), became a shareholder too. As Boreal Bioref did not have much capital, it set a goal to raise €1.000 million in investments, mainly from China, but also from elsewhere. A Chinese state-owned company, Camce, backed by the Chinese National Investment Bank, was involved in negotiations, but eventually did not invest in Boreal Bioref. Camce wanted to be a majority shareholder, but the local and other Western investors were not willing to allow a Chinese partner to have the majority (Kemijärven sellutehdashanke hyytyi, Citation2021). Moreover, there were several competing large pulp mill projects around Finland, and as wood resources are limited, not all of them could be executed. Therefore, it was also a matter of speed, of who would be first to get their licences and funding. The biorefinery in Kemijärvi would be the most peripheral of the planned pulp mills.

What made the founding of the new company possible was, first, the timing, which was optimal for a modern biorefinery, with global demand for new biomaterials increasing. Second, in 2015, the Forest Champion, with his partners from Aalto University, participated in the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment’s competition to create new bioproduct opportunities, for which they earned second place. This success in the national competition paved the way for negotiations with potential funders and enhanced the credibility of the project. Third, the Municipal Council of Kemijärvi supported the idea and provided modest funding and, eventually, some risk capital to prepare for founding a new company. Fourth, the Forest Champion, as a CEO of Boreal Bioref Ltd, was strongly encouraged by local people, likely because of the large local network generated during the mass movement. Fifth, Finnish Cabinet members, including the Prime Minister, encouraged them to move forward with the biorefinery project. The state considered the project to be important and made a €200 million commitment to improve transportation infrastructure, provided that the mill would be established. Moreover, Boreal Bioref Ltd had an R&D network consisting of researchers and development companies interested in new technology and business models related to a forest-based bioeconomy. The company gained visibility and was contacted by interested parties from around the world, such as universities, related firms and research institutes, offering their partnership in terms of innovations and technologies to be tested in the next-generation pulp mill. Last but not least, Boreal Bioref was very bold in its active contacting of international and domestic investors

Let’s think about this really, a billion-euro investment. If we can take this to the goal – when we can get this to the goal, totally penniless people have just launched this. The development company gave the first small investment to this company. We are not talking about any basic pulp factory here. It is just the compulsory bad thing here that we need to have, so that we can access the real high-value products. (a development company representative)

In 2021, according to local media (Kasurinen, Citation2021), after a series of political debates and company arrangements, Vataset Teollisuus Ltd took over the project from Boreal Bioref Ltd and established a new company, Kemijärven Biojalostamo Ltd (Biorefinery of Kemijärvi). As of the writing of this article in 2021, €200 million investments are being negotiated and, according to Vataset Ltd, the plan and hope is to raise the remaining €800 million so that the mill can open in 2024 (see High earnings and sustainability meet, 2021).

6.3. Forestin eco-industry park

Alongside finding a way to establish a new biorefinery in Kemijärvi, Boreal Bioref Ltd (later Vataset Teollisuus Ltd), the Municipal Council of Kemijärvi and other municipalities in Eastern Lapland began, in collaboration, to promote Forestin Eco-industry Park in Kemijärvi, the local development company (Kemijärven Kehitys Ltd) coordinating the development activities. The company created business concepts for the park and started searching for companies to adopt them. The lessons learned from past experiences revealed that one plant is not enough, and that an industrial symbiosis is needed to provide added value and commitment to the region. A wood-based business ecosystem is planned to include several collaborating companies following principles of the circular economy and turning into a new growth engine for Eastern Lapland.

If and when we go forward with the construction of the biorefinery, the next step from the developer’s perspective would be this ‘Forestin’ concept. We are talking about developing an eco-industry park around Keitele and Boreal Bioref … This is a super interesting project because we are talking about next generation products. How we can really reduce the carbon footprint, replace plastic products, add wood-based ingredients to food, medicine, cosmetics and so on. (a development company representative)

Related to the eco-industry park, we have made these business model cards, or what should one call them, productized concepts. We have everything there, all components that you can take and start a business here. We have negotiated much in advance … We are not selling just a site, we are selling a service package. Come here and you will have all this ready around you, synergies with these companies. (a development company representative)

While the planned biorefinery was seen to form the heart of the industry park, its establishment was slow going. Therefore, the Municipal Council of Kemijärvi and the local development agency worked to attract other companies to relocate to the eco-industry park. The major step thus far was the Finnish family-owned company Keitele Group’s new sawmill, and a glue-laminated beam factory in Kemijärvi, established in 2014, employing approximately 120 people in 2020 (Hautala, Citation2020). The Keitele Group built a sawmill in Kemijärvi primarily because of the location’s good wood resources and railroad. Moreover, the Municipal Council, with the support of the Regional Council of Lapland, negotiated with the state about electrifying and constructing a new railroad track and a new wood terminal at the industry park, and with Stora Enso about selling a land area needed for the industrial park. Since the early 2020s, an ERDF-funded ‘Forestin’ project has been in operation to further develop the concept of the eco-industry park.

The interviewees viewed the local political atmosphere as rather volatile, which could complicate the decision-making in the municipal council and pose its own set of challenges. The Centre Party is the leading political force in Kemijärvi, while the Left Alliance is the second most influential party. The Left Alliance having a key position in local politics is rare in the 2020s Finland. Considering the long and colourful industrial history of Kemijärvi, a viable labour movement is a natural consequence of it, as is the low threshold to mobilize demonstrations. Relatedly, when faced with threats and experiencing unfair treatment by external actors, the local mechanisms of influence are not so much channelled through business associations or other formal channels, as is often the case in Finland, but through ad hoc social movements. A representative example is the ‘train rebellion’, which mobilized locals to protest the termination of the last passenger train connections to Kemijärvi. Similarly, the ‘mass movement’, fighting very visibly on all fronts the closure of the pulp mill, was a typical form of agency in Eastern Lapland.

We are so far away here. We are in a way united, but concerning the ‘Masters of Helsinki’, we are ununited because we don’t like them. And we have proof that this is the right attitude. (retired mayor of a municipality)

When facing threats, there has been a lot to do together. ‘Train rebellion’ and ‘Mass movement’ indicate that … when there is a threat or something else, people have come together. (a person involved in social movements)

The people of Kemijärvi did not understand this at all (the pulp mill closure decision). They thought that if they began a total hassle, the decision would be called off. (ministry official)

The biorefinery and eco-industry park are a manifestation of a more future-oriented and proactive effort, the main ambition being, in path development vocabulary, ‘to upgrade the industrial path by climbing the global production chain’ (Grillitsch & Asheim, Citation2018). On the other hand, these developments are connected to Eastern Lapland’s position as a resource periphery, but in a tone of renewal. The place leaders and their support group, who launched the process and began to mobilize funding, required expertise (technology) and support from institutional power holders. At first, the main strategy was to continue past path but was revised to focus on upgrading the industrial path and to provide the potential diversification with a platform (a biorefinery and ecosystem evolving on it), as has been done in Northern Central Finland (see Sotarauta & Suvinen, Citation2019).

7. Discussion of the empirical observations

Drawing on a descriptive case study that presents a formation story about a particular industrial path and related agency in a specific place at a specific time (Rutzou & Elder-Vass, Citation2019), we were not in a position to formulate generalizable causal claims. However, we were able to show how local agency and the industrial path coevolve through many phases and a myriad of processes, each phase reflecting its logic and core actions and decisions. Furthermore, we were able to identify groups of individuals, working more than many to provide the sub-region with opportunities to diversify its economy. We did not underline idiosyncratic stories of individual heroes. We did not stress deterministic structural explanations either (for contrasting perspectives on path development, see Mahoney Citation2000 and Garud et al., Citation2010). Nevertheless, we revealed how structures privilege some actors and their strategies and enable some actions over others. Consciously or unconsciously, actors working for change need to adapt to disparities of privileging structures and policies through strategic-contextual analysis and related practices when choosing a course of action. These observations are in line with Jessop’s (Citation2001; see also Lagendijk, Citation2007) notions on strategic-relational approach. In line with Garud et al. (Citation2010), we highlight the incessantly emerging nature of path development and argue that local actors operate across the temporal horizon. They combine elements from the past while seeking for and constructing the future. In doing so, local change agents deliberately reach beyond their spheres of influence and local circles to mobilize local and extra-regional resources, knowledge and competences. Despite being locally oriented, local change agency is multi-scalar by nature (see e.g. Hassink et al., Citation2019), actors reaching multi-scalar knowledge bases and funding opportunities for path development (e.g. Chen & Hassink, Citation2020).

For small peripheral communities and regions being dependent on their natural resources and facing extreme difficulties, Eastern Lapland is a representative case. Before the era of external shocks, placeless corporate leaders made decisions that favoured Eastern Lapland, and the financial support of the very place-oriented State of Finland (at that time) eased the decision-making.

Whether it is about protecting or harnessing the environment, decisions are often made somewhere else than at the local or regional level. In a good and bad sense, we have been led by others. (a national-level politician from the region)

Entrepreneurial spirit is missing, and people are used to having big employers. Now they are waiting for the Bioref to come … when someone begins to plan entrepreneurship, the lack of capital is huge. This place is not a region worth investing in … somehow, the atmosphere here is oppressive because of state dependency and the dependency on big projects. It’s just about waiting, and there is a lack of independent initiatives. (a local developer)

The past-oriented narratives failing to persuade the external powerholders, local actors moved to envision a diversified future through narratives and vision building on a rapidly emerging understanding of new forms of bioeconomy, instead of those drawing on the past pulp-related days of glory. In this way, local change agency in Eastern Lapland reflects well Emirbayer and Mische’s (Citation1998) notion on agency as temporally constructed engagement, both reproducing and transforming the prevailing imaginaries and narratives. By necessity, local change agency operates in between the past visions (cognitive lock in) and future expectations; the former being strongly embedded in the local socio-political-economic fabric of a place, the latter being open for (heated) local debates and dependent on extra-regional resources and knowledge.

The dust settling, place leaders turned their gaze to mobilizing a support community for an upgraded pulp path and related forest-based bioeconomy ecosystem. They realized how important such a group of actors is, combining different expertise and having ‘a feeling of fellowship with others because of sharing common attitudes, interests and objectives in terms of willingness to assist the process with all possible means at their disposal’ (Sotarauta & Mustikkamäki, Citation2015, p. 350). The support community consisted of the municipal council (formal power), local development company (coordination) and academics from Aalto University (expertise) to upgrade the development strategy, the main ambition being to fit the globally emerging forest-based bioeconomy thinking into the local reality. In doing so, the champions of change, both assigned and non-assigned, assumed and earned the role of place leaders.

In sum, first, place leaders mobilized and coordinated demonstrations to protest and reverse the decisions but learnt to mobilize local powers and external thinking and expertise to construct a more positive concept for the future. A support community does not materialize out of thin air but calls for skilled place leaders to convince and persuade very different actors, with varying capacities and capabilities, to join the development efforts. Place leaders not only mobilized thinking and formal powerholders but also worked to raise funding for a grand investment. Place leadership emerged to improve the local capacity of entrepreneurship, both institutional and innovative. To enhance the process, some of the place leaders were willing to take the financial risk on the identified business opportunities and turned innovative entrepreneurs themselves. We summarize the pattern of Trinity of Change Agency in Eastern Lapland in .

Table 2. The pattern of trinity of change agency in Eastern Lapland.

8. Conclusions

Any analysis on agency needs to reveal the hidden order of processes, not satisfying to see only the formal policies. Identification of the patterns of agency allows us to dig deeper in the reciprocal interaction of structures and agency (potentially a causal power). As, in our research work, the generalization builds on substantive interpretation of both individual and a set of cases, drawing on all empirical, contextual and theoretical knowledge related to them (Rutten, Citation2021), it is central to carefully study a single case to understand how agency evolves in time, not to approach agency as static and industries as dynamic. Otherwise, we would turn a blind eye on the diversity of actors and their strategies, and assume that agency is more or less the same, while its structures that differ. In-depth single cases provide a ground for the comparisons.

Therefore, this study adds to the literature on regional development by investigating the patterns of trinity of change agency in a peripheral region. Our results show how a strong top-down influence weakens the local capacity to act (see Beer & Clover, Citation2014); being a recipient of top-down support and dominated by branch plants of major corporations is not fertile soil in which to learn the art of place leadership and institutional entrepreneurship. Being dependent on the external actors is typical for resource peripheries (Halonen Citation2019). Of course, it is highly unlikely that Eastern Lapland would have been industrialized without strong external support, and it remains to be seen how well the local champions of change will cope with the huge challenges they are facing.

We also show how the pattern of trinity of change agency changes in time, and how path-dependent it is; the modes of action and influence learnt in the past prevail in a dramatically changed situation. However, our study also provides hope that old patterns of agency may change, even if these processes are often slow and painful. The crisis can offer a window for change. In a crisis, place leaders may surface, and they will be required to learn new ways of acting. They are needed to build confidence and mobilize resources, capabilities and power. Importantly, the theory of trinity of change agency does not posit fixed relationships or conceptual boundaries between the three forms of agency or attach the three types of change agency to specific organizations. It allows for the identification and analysis of different forms of change agency and their relationships in differing conditions, in different times and places. In varying contingencies, different actors may earn or take on respective roles by their actions.

To secure the future success of their own organizations, placeless leaders make placeless decisions according to their own criteria (Hambleton, Citation2015), unintentionally causing havoc in respective localities. All too often, peripheral regions are seen as places without a future, as places where the game is over, or as places that have been left behind (Rodriguez-Pose, Citation2018). The negative industrial paths in Eastern Lapland have, understandably, generated sustained pessimism. Some older people encourage the young to leave – ‘there is nothing for you here’. If peripheral regions are seen as passive ‘victims’ of their locational destiny (Willet & Lang, Citation2017), and ‘if local people see themselves as powerless and voiceless’, the local capacity to act – to formulate development strategies, locate and exploit external opportunities and mobilize collective action – will remain at a low level. Consequently, ‘the future will turn out as discussed’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Finnish Forest Centre is a state-funded organization covering the whole country, ‘promoting forestry and related livelihoods, advising landowners on how to care for and benefit from their forests and the ecosystems therein, collecting and sharing data related to Finland's forests and enforcing forestry legislation.’ (Finnish Forest Centre – information on Finnish Forests, Citation2021).

References

- Audretsch, D., I. Grilo, and A. Roy Thurik. 2011. “Globalization, Entrepreneurship, and the Region.” In Handbook of Research on Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, edited by M. Fritsch, 11–32. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Augsdorfer, P. 2005. “Bootlegging and Path Dependency.” Research Policy 34 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2004.09.010

- Bækkelund, N. 2021. “Change Agency and Reproductive Agency in the Course of Industrial Path Evolution.” Regional Studies, doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1893291.

- Battilana, J., B. Leca, and E. Boxenbaum. 2009. “How Actors Change Institutions: Towards a Theory of Institutional Entrepreneurship.” The Academy of Management Annals 3: 65–107. doi:10.5465/19416520903053598

- Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S., L. Fuenfschilling, J. Miörner, and M. Trippl. 2020. “Reconsidering Structural Conditions: Institutional Infrastructure for Innovation-Based Industrial Path Renewal.” PEGIS – Papers in Economic Geography and Innovation Studies 2020/01. Accessed December 27, 2021. http://www-sre.wu.ac.at/sre-disc/geo-disc-2021_09.pdf.

- Beer, A. 2018. “The Closure of the Australian car Manufacturing Industry: Redundancy, Policy and Community Impacts.” Australian Geographer 49 (3): 419–438. doi:10.1080/00049182.2017.1402452

- Beer, A., S. Ayres, T. Clower, F. Faller, A. Sancino, and M. Sotarauta. 2019. “Place Leadership and Regional Economic Development: A Framework for Cross-Regional Analysis.” Regional Studies 53 (2): 171–182. doi:10.1080/00343404.2018.1447662

- Beer, A., T. Barnes, and S. Horne. 2021. “Place-based Industrial Strategy and Economic Trajectory: Advancing Agency-Based Approaches.” Regional Studies, doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1947485.

- Beer, A., and T. Clower. 2014. “Mobilising Leadership in Cities and Regions.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 1 (1): 10–34.

- Beer, A., F. McKenzie, J. Blažek, M. Sotarauta, and S. Ayres. 2020. Every Place Matters: Towards Effective Place-Based Policy. Regional Studies Policy Impact Books; Milton Park: Taylor & Francis.

- Beer, A., S. Weller, T. Barnes, I. Onur, J. Ratcliffe, D. Bailey, and M. Sotarauta. 2019. “The Urban and Regional Impacts of Plant Closures: New Methods and Perspectives.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 6 (1): 380–394. doi:10.1080/21681376.2019.1622440

- Bellandi, M., M. Plechero, and E. Santini. 2021. “Forms of Place Leadership in Local Productive Systems: From Endogenous Rerouting to Deliberate Resistance to Change.” Regional Studies 55 (7): 1327–1336. doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1896696

- Benner, M. 2021. “Revisiting Path-as-process: A Railroad Track Model of Path Development, Transformation, and Agency.” PEGIS – Papers in Economic Geography and Innovation Studies. Accessed December 27, 2021. http://www-sre.wu.ac.at/sre-disc/geo-disc-2021_09.pdf.

- Benneworth, P., R. Pinheiro, and J. Karlsen. 2017. “Strategic Agency and Institutional Change: Investigating the Role of Universities in Regional Innovation Systems (RISs).” Regional Studies 51 (2): 235–248. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1215599

- Binz, C., B. Truffer, and L. Coenen. 2016. “Path Creation as a Process of Resource Alignment and Anchoring – Industry Formation for Onsite Water Recycling in Beijing.” Economic Geography 92 (2): 172–200. doi:10.1080/00130095.2015.1103177

- Blažek, J., V. Květoň, S. Baumgartinger-Seiringer, and M. Trippl. 2020. “The Dark Side of Regional Industrial Path Development: Towards a Typology of Trajectories of Decline.” European Planning Studies 28 (8): 1455–1473. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1685466

- Carvalho, L., and M. Vale. 2018. “Biotech by Bricolage? Agency, Institutional Relatedness and new Path Development in Peripheral Regions.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11 (2): 275–295. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsy009

- Chen, Y., and R. Hassink. 2020. “Multi-scalar Knowledge Bases for New Regional Industrial Path Development: Toward a Typology.” European Planning Studies 28 (12): 2489–2507. doi:10.1080/09654313.2020.1724265

- Coe, N., and D. Jordhus-Lier. 2011. “Constrained Agency? Re-Evaluating the Geographies of Labour.” Progress in Human Geography 35: 211–233. doi:10.1177/0309132510366746

- Coe, N., and H. Yeung. 2015. Global Production Networks: Theorizing Economic Development in an Interconnected World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Collinge, C., and J. Gibney. 2010. “Connecting Place, Policy and Leadership.” Policy Studies 31 (4): 379–391. doi:10.1080/01442871003723259

- Content, J., and K. Frenken. 2016. “Related Variety and Economic Development: A Literature Review.” European Planning Studies 24 (12): 1–16. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1246517

- Cooke, P. 1998. “The New Wave of Regional Innovation Networks: Analysis, Characteristics and Strategy.” Small Business Economics 8: 159–171. doi:10.1007/BF00394424

- Dawley, S. 2014. “Creating New Paths? Offshore Wind, Policy Activism, and Peripheral Region Development.” Economic Geography 90 (1): 91–112. doi:10.1111/ecge.12028

- Dawley, S., D. MacKinnon, A. Cumbers, and A. Pike. 2015. “Policy Activism and Regional Path Creation: The Promotion of Offshore Wind in North East England and Scotland.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 8 (2): 257–272. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsu036

- Emirbayer, M., and A. Mische. 1998. “What is Agency?” American Journal of Sociology 103: 962–1023. doi:10.1086/231294

- Feldman, M. 2014. “The Character of Innovative Places: Entrepreneurial Strategy, Economic Development, and Prosperity.” Small Business Economics 43: 9–20. doi:10.1007/s11187-014-9574-4

- Finnish Forest Centre – information on Finnish Forests. 2021. https://www.metsakeskus.fi/en

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (2): 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363

- Foray, D., P. David, and B. Hall. 2009. “Smart Specialisation: The Concept.” Knowledge Economists Policy Brief 9: 100.

- Fuller, C., and N. Phelps. 2018. “Revisiting the Multinational Enterprise in Global Production Networks.” Journal of Economic Geography 18: 139–161. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbx024

- Galster, G. 2018. “Why Shrinking Cities Are Not Mirror Images of Growing Cities: A Research Agenda of Six Testable Propositions.” Urban Affairs Review 55 (1): 355–372. doi:10.1177/1078087417720543

- Garud, R., and P. Karnoe. 2001. “Path Creation as a Process of Mindful Deviation.” In Path Dependence and Creation, edited by R. Garud and P. Karnøe, 1–39. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Garud, R., A. Kumaraswamy, and P. Karnøe. 2010. “Path Dependence or Path Creation?” Journal of Management Studies 47: 760–774. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00914.x

- Gibney, J., and A. Nicholds. 2021. “Re-imagining Place Leadership as a Social Purpose.” In Handbook on City and Regional Leadership, edited by M. Sotarauta and A. Beer, 71–90. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Cambridge: Policy Press.

- Gregory, D., R. Johnston, G. Pratt, M. Watts, and S. Wathmore. 2009. The Dictionary of Human Geography. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Grillitsch, M., and B. Asheim. 2018. “Place-based Innovation Policy for Industrial Diversification in Regions.” European Planning Studies 26 (8): 1638–1662. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1484892

- Grillitsch, M., B. Asheim, and H. Nielsen. 2022. “Temporality of Agency in Regional Development.” European Urban and Regional Studies 29 (1): 107–125. doi:10.1177/09697764211028884

- Grillitsch, M., M. Martynovich, R. Fitjar, and S. Haus-Reve. 2021. “The Black Box of Regional Growth.” Journal of Geographical Systems 23 (3): 425–464. doi:10.1007/s10109-020-00341-3

- Grillitsch, M., J. Rekers, and M. Sotarauta. 2021. “Investigating Agency: Methodological and Empirical Challenges.” In Handbook on City and Regional Leadership, edited by M. Sotarauta and A. Beer, 302–323. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Grillitsch, M., and M. Sotarauta. 2020. “Trinity of Change Agency, Regional Development Paths and Opportunity Spaces.” Progress in Human Geography 44 (4): 704–723. doi:10.1177/0309132519853870

- Grillitsch, M., M. Sotarauta, B. Asheim, R. Fitjar, S. Haus-Reve, J. Kolehmainen, H. Kurikka, et al. (forthcoming). “Agency and Economic Change in Regions: Using Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) to Identify Routes to New Path Development.” A paper under review for a journal.

- Halonen, M. 2019. Booming, Busting – Turning, Surviving? Socio-Economic Evolution and Resilience of a Forested Resource Periphery in Finland. Publications of the University of Eastern Finland, Dissertations in Social Sciences and Business Studies No 205. Joensuu: University of Eastern Finland.

- Hambleton, R. 2015. Leading the Inclusive City. Place-Based Innovation for a Bounded Planet. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Hassink, R., A. Isaksen, and M. Trippl. 2019. “Towards a Comprehensive Understanding of new Regional Industrial Path Development.” Regional Studies 53 (11): 1636–1645. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704

- Hautala, E. 2020. Keitele Groupin Kemijärven saha on suurin sahapuun käyttöpiste Lapissa. Koti-Lappi, 2020-09-17.

- Henning, M., E. Stam, and R. Wenting. 2013. Path dependence research in regional economic development: Cacophony or knowledge accumulation?. Regional Studies 47 (8) 1348–1362.

- Hidle, K., and R. Normann. 2013. “Who Can Govern? Comparing Network Governance Leadership in two Norwegian City Regions.” European Planning Studies 21 (2): 115–130. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.722924

- Honkapohja, S., and E. Koskela. 1999. “The Economic Crisis of the 1990s in Finland.” Economic Policy 14: 400–436. doi:10.1111/1468-0327.00054

- Huggins, R., and P. Thompson. 2019. “The Behavioural Foundations of Urban and Regional Development: Culture, Psychology and Agency.” Journal of Economic Geography 19 (1): 121–146. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbx040

- Huggins, R., and P. Thompson. 2020. “Human Agency, Entrepreneurship, and Regional Development: A Behavioural Perspective on Economic Evolution and Innovative Transformation.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 32 (7): 573–589. doi:10.1080/08985626.2019.1687758

- Isaksen, A. 2015. “Industrial Development in Thin Regions: Trapped in Path Extension?” Journal of Economic Geography 15 (3): 585–600. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbu026

- Isaksen, A., S. Jakobsen, R. Njös, and R. Norman. 2019. “Regional Industrial Restructuring Resulting from Individual and System Agency.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 32 (1): 48–65. doi:10.1080/13511610.2018.1496322

- Isaksen, A., and J. Karlsen. 2016. “Handbook on the Geographies of Innovation.” In Handbook on the Geographies of Innovation, edited by R. Shearmur, C. Carrincazeaux, and D. Doloreux, 277–291. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Isaksen, A., and M. Trippl. 2017. “Exogenously led and Policy-Supported new Path Development in Peripheral Regions: Analytical and Synthetic Routes.” Economic Geography 93 (5): 436–457. doi:10.1080/00130095.2016.1154443

- Jessop, B. 2001. “Institutional Re(turns) and the Strategic-Relational Approach.” Environment and Planning A 33: 1213–1235. doi:10.1068/a32183

- Jolly, S., M. Grillitsch, and T. Hansen. 2020. “Agency and Actors in Regional Industrial Path Development: A Framework and Longitudinal Analysis.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 111 (4): 176–188.

- Kasurinen, S. 2021. Rahoittajilla vankka luottamus Kemijärven sellutehdashankkeeseen. Koti-Lappi. 15 May 2021. https://www.kotilappi.fi/artikkeli/rahoittajilla-vankka-luottamus-kemijarven-sellutehdashankkeeseen-199833279/

- Kemijärven sellutehdashanke hyytyi, kun läntiset sijoittajat eivät halunneet pääosakkaaksi Kiinan valtionyhtiötä. YLE News, 3 February. 2021. https://yle.fi/uutiset/3-11771090

- Klenke, K. 2008. Qualitative Research in the Study of Leadership. Bingley: Emerald Group.

- Krehl, A., and S. Weck. 2020. “Doing Comparative Case Study Research in Urban and Regional Studies: What Can be Learnt from Practice?” European Planning Studies 28 (9): 1858–1876. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1699909

- Kurikka, H., and M. Grillitsch. 2021. “Resilience in the Periphery: What an Agency Perspective Can Bring to the Table.” In Economic Resilience in Regions and Organisations, edited by R. Wink, 147–171. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Kurikka, H., J. Kolehmainen, M. Sotarauta, H. Nielsen, and M. Nilsson. (Forthcoming). Perceiving regional opportunity spaces – Observations from Nordic regions. A paper under review for a journal.

- Kurikka, K., M. Sotarauta, and Jari Kolehmainen. 2021. “Eastern Lapland sub-Region.” In Toimijuus ja mahdollisuuksien tilat aluekehityksessä: Miten kehittyä vastoin kaikkia oletuksia? Sente-julkaisuja 35/2021, edited by M. Sotarauta, H. Kurikka, J. Kolehmainen, and S. Sopanen, 147–171. Tampere: Tampereen yliopisto.

- Lagendijk, A. 2007. “The Accident of the Region: A Strategic Relational Perspective on the Construction of the Region’s Significance.” Regional Studies 41 (9): 1193–1207. doi:10.1080/00343400701675579

- MacKinnon, D., S. Dawley, A. Pike, and A. Cumbers. 2019. “Rethinking Path Creation: A Geographical Political Economy Approach.” Economic Geography 95: 113–135. doi:10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294

- Martin, R. and P. Sunley. 2010. The place of path dependence in an evolutionary perspective on the economic landscape. In The handbook of evolutionary economic geography, edited by R. Boschma, and R. Martin, 62–92. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Mahoney, J. 2000. “Path Dependence in Historical Sociology.” Theory and Society 29 (4): 507–548. doi:10.1023/A:1007113830879

- Männistö, J. 2002. Voluntaristinen alueellinen innovaatiojärjestelmä: Tapaustutkimus Oulun ICT-klusterista. Acta universitatis lappoensis 46. Rovaniemi.

- Miörner, J. 2020. “Contextualizing Agency in new Path Development: How System Selectivity Shapes Regional Reconfiguration Capacity.” Regional Studies, 1–13. doi:10.1080/00343404.2020.1854713.

- Morgan, K. 1997. “The Regional Animateur: Taking Stock of the Welsh Development Agency.” Regional & Federal Studies 7 (2): 70–94. doi:10.1080/13597569708421006

- Moulaert, F., B. Jessop, and A. Mehmood. 2016. “Agency, Structure, Institutions, Discourse (ASID) in Urban and Regional Development.” International Journal of Urban Sciences 20 (2): 167–187. doi:10.1080/12265934.2016.1182054

- Mønnesland, J. 1994. Regional Policy in the Nordic Countries. Nordrefo 4/1994. Holstebro: Nordfefo.

- Neil, D., and M. Tykkyläinen. 1998. Local Economic Development: A Geographical Comparison of Rural Community Restructuring. Tokyo: United Nations U.P.

- Nenonen, M. 2018. “Alueiden Suomi 1500-2000.” In Suomen rakennehistoria: Näkökulmia muutokseen ja jatkuvuuteen (1400-2000), edited by P. Haapala, 67–91. Tampere: Vastapaino.

- Phelps, N., M. Atienza, and M. Arias. 2018. “An Invitation to the Dark Side of Economic Geography.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 50 (1): 236–244. doi:10.1177/0308518X17739007

- Phelps, N., and C. Fuller. 2016. “Inertia and Change in Multinational Enterprise Subsidiary Capabilities: An Evolutionary Economic Geography Framework.” Journal of Economic Geography 16: 109–130. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbv002

- Potluka, O. 2021. “Roles of Formal and Informal Leadership: Civil Society Leadership Interaction with Political Leadership on Local Development.” In Handbook on City and Regional Leadership, edited by M. Sotarauta and A. Beer, 91–107. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2018. “The Revenge of the Places That Don’t Matter (and What to Do About It).” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11 (1): 189–209. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsx024

- Rutten, R. 2021. “Uncertainty, Possibility, and Causal Power in QCA.” Sociological Methods & Research, Online First, 1–30. doi:10.1177/00491241211031268.

- Rutzou, T., and D. Elder-Vass. 2019. “On Assemblages and Things: Fluidity, Stability, Causation Stories, and Formation Stories.” Sociological Theory 37 (4): 401–424. doi:10.1177/0735275119888250

- Salcomp. 2021. History. Accessed 29 October 2021. https://salcomp.com/history/.

- Sancino, A., L. Budd, and M. Pagani. 2021. “Place Leadership, Policy-Making and Politics.” In Handbook on City and Regional Leadership, edited by M. Sotarauta and A. Beer, 57–70. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Shane, S., and S. Venkataraman. 2000. “The Promise of Entrepreneurship as a Field of Research.” The Academy of Management Review 25: 217–226.

- Shearmur, R. 2015. “Far from the Madding Crowd: Slow Innovators, Information Value, and the Geography of Innovation.” Growth and Change 46 (3): 424–442. doi:10.1111/grow.12097

- Sotarauta, M. 2012. Policy Learning and the ‘Cluster Flavoured Innovation Policy’ in Finland. Environment & Planning C: Government and Policy 30 (5), 780–795.

- Sotarauta, M. 2016. Leadership and the City: Power, Strategy and Networks in the Making of Knowledge Cities. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Sotarauta, M., and A. Beer. 2021. “Introduction to City and Regional Leadership.” In Handbook on City and Regional Leadership, edited by M. Sotarauta and A. Beer, 2–18. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Sotarauta, M., and M. Grillitsch. Forthcoming. “Path Tracing in the Study of Agency and Structures: Methodological Considerations.” A paper under review for a journal.

- Sotarauta, M., and N. Mustikkamäki. 2015. “Institutional Entrepreneurship, Power, and Knowledge in Innovation Systems: Institutionalization of Regenerative Medicine in Tampere, Finland.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 33 (2): 342–357. doi:10.1068/c12297r

- Sotarauta, M., and R. Pulkkinen. 2011. “Institutional Entrepreneurship for Knowledge Regions: In Search of a Fresh Set of Questions for Regional Innovation Studies.” Environment & Planning C: Government and Policy 29 (1): 96–112. doi:10.1068/c1066r

- Sotarauta, M., and N. Suvinen. 2019. “Place Leadership and the Challenge of Transformation: Policy Platforms and Innovation Ecosystems in Promotion of Green Growth.” European Planning Studies 27 (9): 1748–1767. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1634006

- Sotarauta, M., N. Suvinen, S. Jolly, and T. Hansen. 2021. “The Many Roles of Change Agency in the Game of Green Path Development in the North.” European Urban and Regional Studies 28 (2): 92–110. doi:10.1177/0969776420944995

- StatFin. 2021. Väestötilastot (population statistics). https://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/fi/StatFin/.

- Steen, M. 2016. “Reconsidering Path Creation in Economic Geography: Aspects of Agency, Temporality and Methods.” European Planning Studies 24 (9): 1605–1622. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1204427

- Steen, M., and G. Hansen. 2018. “Barriers to Path Creation: The Case of Offshore Wind Power in Norway.” Economic Geography 94 (2): 188–210. doi:10.1080/00130095.2017.1416953

- Tervo, H. 2005. “Regional Policy Lessons from Finland.” In Regional Disparities in Small Countries, edited by D. B. Portnov Felsenstein, 267–282. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Tomaney, J., A. Pike, and J. Cornford. 1999. “Plant Closure and the Local Economy: The Case of Swan Hunter on Tyneside.” Regional Studies 33 (5): 401–411. doi:10.1080/00343409950081257

- Tödtling, F., and M. Trippl. 2005. “One Size Fits All? Towards a Differentiated Regional Innovation Policy Approach.” Research Policy 34: 1203–1219. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2005.01.018

- Vale, M., and L. Carvalho. 2013. “Knowledge Networks and Processes of Anchoring in Portuguese Biotechnology.” Regional Studies 47 (7): 1018–1033. doi:10.1080/00343404.2011.644237

- Willet, J., and T. Lang. 2017. “Peripheralisation: A Politics of Place, Affect, Perception and Representation.” Sociologias Ruralis 58: 2.

- Yin, R. 2016. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. 6th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.