ABSTRACT

The last three decades reveal a burgeoning body of research that critically examines the role of private actors in the governance of public space. Contributing to this work, this paper shows how an increasing number of outdoor retail markets in the Netherlands have become typified by forms of physical and symbolic exclusion, although these outcomes are achieved by different methods and practices than direct private appropriation and provision. Through the creation of non-profit quasi-autonomous non-governmental organizations (quangos), more and more local governments have delegated their responsibilities for the management and regulation of markets to trader-run organizations; a process called ‘autonomization’. Based on semi-structured interviews, participant observation and documentary research, the paper traces the main motivations behind, as well as the implications of, this process. It points to the sometimes ambivalent nature of quangos, in which a selected number of market traders stipulate what type of participation in markets is appropriate. The concept of ‘soft’ privatization is developed to denote autonomization as it does not directly exclude traders and visitors, but instead creates a particular governance regime and sense-scape that attracts certain people and excludes others.

1. Introduction

‘Welcome to the most beautiful market of the Netherlands: Valkenswaard! Come on, shake your hips!’ − It is a sunny Thursday in September 2021 when two performers called Los del Sol try to bring a Mexican atmosphere to the village’s central outdoor retail market by means of their music, dance and colourful appearance. This is not a particularly unusual event in Valkenswaard, a small town located in the south of the Netherlands. Since the responsibility for the management of the market has been delegated from the local government to a trader-run organization in 2014 – a process we call ‘autonomization’ in this paper – much ‘shopertainment’ such as live music and street comedy has been added to the selling activities on the market. This exemplifies the market’s new slogan: ‘Every Thursday’s a party’.

Valkenswaard is not the only town in the Netherlands that has an autonomized market. In the last decade, 50 other autonomized markets have steadily emerged, while tens of markets are currently in the process of autonomization. Although institutional actors generally regard this as a desirable – and even essential – trend to counteract the overall decline of market trading in the country, it raises many questions regarding the politics of public space, including its management and public accessibility.

Governance regimes that transfer responsibilities for public spaces away from the public to the private sector have long been criticized by planners and geographers for causing the ongoing commodification and securitization of public space (e.g. Sorkin Citation1992; Low and Smith Citation2006; Loughran Citation2014). Although recent studies call for a more nuanced view of the negative connotations of privatization (e.g. Leclercq, Pojani, and van Bueren Citation2020), the dominant discourse is still based on the notion that everyday urban life in public space has increasingly been appropriated by the private market (Dovey Citation2016). However, not only the private sector is involved in the politics of public space. In recent years, we have witnessed the involvement of a wide range of different stakeholders in the management of public space (De Magalhães Citation2010), also including individual citizens and entrepreneurs.

This paper contributes to this body of literature by exploring a relatively new, ‘softer’ variation of privatization: the autonomization (in Dutch: verzelfstandiging) of public space through the creation of non-profit quasi-autonomous non-governmental organizations; also known as quangos (Barker Citation1982). Drawing on research that is part of an international research project on outdoor markets in several European countries,Footnote1 this paper aims to answer the following research question: ‘What are the main motivations behind, and the implications of, the autonomization of outdoor markets in the Netherlands?’

Our analysis shows that many different stakeholders make use of strikingly similar motivations to underscore the need for, and effectiveness of, autonomization, thereby rendering forms of managerial governance self-evident. Through a process of ‘institutional mirroring’ (Uitermark and Duyvendak Citation2008), the emphasis on entrepreneurial and business-like governance of public space has become manifest. We argue that the discursive celebration and apparent self-evidence of these governance principles lead to a situation in which autonomization is not so much judged on the basis of its implications for participation and inclusion, but rather on how well it can be presented to (prospective) partners and municipalities. Although autonomization often leads to more cost-effectiveness, it also puts potential constraints on equal access to markets and their governance process. The findings are based on a range of qualitative methods, including ethnographic fieldwork in the Valkenswaard market and semi-structured interviews with policy makers, representatives of the trade union, and professionals throughout the Netherlands.

This paper continues with a discussion of existing literature on the emergence and implications of complex public space governance arrangements. Section 3 introduces the research methodology. Section 4 sketches how autonomized markets have emerged and spread throughout the Netherlands, especially in not-so-urban areas. Section 5 outlines the main motivations to do so, while Section 6 illustrates the effects. In Section 7, we conclude what autonomization as a softer form of privatization means for democratic participation in the production of public space.

2. Theoretical background: state-of-the-art

2.1. Hybrid forms of public space governance: the case of autonomization

It is commonplace to argue that the nature of government has fundamentally changed in Europe over the last decades. While in the post-war period local governments formed the core of a stable governmental framework, they are now considered as one of many actors in the governance of public services. In the Netherlands, processes of local reorganization took effect in the early 1980s when Dutch authorities were faced with fiscal stringency due to the economic recession. These reorganizations were accompanied by a set of steering instruments, including management by objectives, competitive evaluations, and the establishment of public-private contracts (Hendriks and Tops Citation2003). In the same period, the previously dominant role of Dutch governmental bodies in urban development and planning transitioned towards a more facilitating one, resulting in the emergence of diversified planning practices similar to Anglo-Saxon countries to attract higher-income residents, businesses and investors (Heurkens and Hobma Citation2014). Through this process, responsibility has increasingly been devolved from the local government to private sector entities, arms’-length organizations of government, and civil society organizations (Van Melik and van der Krabben Citation2016).

Zamanifard, Alizadeh, and Bosman (Citation2018) have developed a ‘public space governance framework’ to address the complexity and multiplicity of the newly emerged governance arrangements. The authors roughly outline four structure arrangements, while being sensitive to fact that these different governance structures continuously transform and might shape into one another over the course of time. The first structure arrangement is labelled as traditional governance, where ownership and responsibility for the development and management of public space are fully concentrated in the public sector, such as the local government. In market-based governance, it is not the public but the private sector that owns, develops and manages public space. In the two other structure arrangements, the boundaries between the public and private sector are less clearly defined. Managerial governance refers to a situation in which local governments devolve management responsibilities to arm’s-length organizations of government or semi-private entities established by government. In the last structure arrangement, called governance through networks, a wide variety of stakeholders ranging from the public and private sectors to civil society organizations are involved in the ownership and management of public space. Examples may include public spaces that are co-managed and -funded by the local government, trustees and/or local communities, such as community gardens.

In this article, we particularly focus on the third structure arrangement that has become a popular, yet relatively underexplored, governance mechanism to manage and control outdoor markets in the Netherlands: the case of autonomization. Autonomization can be understood as an instrument of managerial governance and is usually subdivided into two main categories: internal and external autonomization. Internal autonomization gives managerial freedom to sub-units within governmental organizations that remain part of the political structure of the government. External autonomization refers to the establishment of quangos that operate at a distance from the government without an immediate hierarchical relationship (Van Thiel Citation2004).

Compared to internally autonomized organizations, externally autonomized quangos are more often allowed to make their own, independent decisions on management and policy implementation. In general, local governments tend to have a strong preference for external autonomization (Van Thiel Citation2004). Based on private law, municipalities can establish non-profit quangos for executive tasks, meaning that they emerge from the decentralization of local government responsibilities. Moreover, quangos operate beyond the legal restrictions as implemented by public administrations and are often allowed to perform legal acts, such as the creation and enforcement of rules and contract systems.

Although a substantive body of literature on the autonomization of governmental management in Europe has emerged within the field of public administration, it is still unknown how this process impacts the governance and outcomes of public spaces. When we direct the attention to studies on public space, it could be argued that autonomization resembles the management of public space as business improvement districts (BIDs); an increasingly dominant governance form that initially emerged in Canada and the US in the 1970s. BIDs are formed when locations that are legally public are put under the (semi-) private management of district commissions. These commissions often consist of a number of people who own real estate or businesses in the area of public space. By levying additional taxes upon property owners, commission members gain the financial resources to privately manage these spaces. Generally, implemented measures aim at raising property values and perceptions of safety, spending the budget on sanitation, street cleaning, security staff and advertisement.

In Europe, BIDS appeared at the beginning of the 2000s in several countries, such as Germany, Ireland, UK and Turkey (e.g. see Mörçol, Vollmer, and Mallinson Citation2022). The literature on BIDs has mainly focused on the process of international proliferation, with a particular focus on global circuits of policy mobilities and the integration of BIDs as a new governance mechanism in the wider context of neoliberalization processes (e.g. McCann and Ward Citation2013; Stein et al. Citation2017; Peyroux Citation2012). While the spread and proliferation of BIDs are rightly situated in what might be termed neoliberal political-economic contexts, it is important to note that their specific development is contingent upon targeted policies, site-specific decision-making processes and lobbying practices.

In this regard, Kizildere and Chiodelli’s (Citation2018) study of the birth and evolution of a BID in Beyoglu, Istanbul, has made clear that its emergence was not related to the activities of international agencies promoting this kind of policy tool. Instead, as the authors note,

the devolution of power over the management of the area to private stakeholders seems to have been due more to pragmatic and contextual needs linked to the final difficulties of the Beyoglu Municipality in maintaining the public space than to a predetermined ideological decision. (Kizildere and Chiodelli Citation2018, 794)

This suggests that the spread of BIDs does not only occur through the motion and adaptation of an overarching ‘neoliberal model’, but also in response to context-specific factors, such as the decline of city and town centres and the inability of local governments to meet organizational and financial challenges.

Notwithstanding the importance of the differences related to the emergence and continued evolution of BIDs in the European context, quangos are quite similar to BID commissions insofar as they consist of elected or appointed board members that are enabled to execute previous governmental tasks. Yet in the case of outdoor markets, quangos do not typically consist of real estate owners. Instead, quango boards are often formed by a number of the entrepreneurs of the markets themselves: the market traders. As such, traders-run quangos do not finance themselves by means of additional taxes but by means of market rents.

Clough and Vanderbeck (Citation2006) approach BIDs as models of ‘limited’ privatization of public space management. Although the newly formed commissions have substantial power over the day-to-day operations of the spaces they manage, they are also constraint in this management ‘insofar as those spaces remain public in the eyes of the law’ (Clough and Vanderbeck Citation2006, 2266). Indeed, BID commissions and quangos do not own public space, meaning that they cannot be closed-off to the general public by means of limiting physical access or charging admission to the districts. Yet, the question remains how this ‘soft’ form of public space privatization through the establishment of quangos has specifically developed in the European context and what the effects are.

2.2. Implications of hybrid public space governance

The changes in public space management as described above have divided scholars on the expected functions of public space (Carmona Citation2010). The degree of equal access to public space and its governance process are two main topics of discussion within this debate. While some have criticized the increasing involvement of the (semi-) private sector in the development and management of public space for causing commodification and exclusion (e.g. Sorkin Citation1992; Low and Smith Citation2006; Loughran Citation2014), others have rebutted these critiques by arguing that it does not necessarily pose a threat to the publicness of public space and might instead provide opportunities for quality enhancement and better management (e.g. Banerjee Citation2001; Van Melik, van Aalst, and van Weesep Citation2009; Leclercq and Pojani Citation2021).

Studies of outdoor markets tend to connect to the first strand of this debate (Guimarães Citation2018; González Citation2020). Markets are thought of as important public spaces that not only provide affordable products accessible to a wide range of customers but also offer opportunities for people from different social-economic and cultural backgrounds to encounter one another (Watson Citation2009). Markets have, at the same time, increasingly been heralded as urban regeneration models to attract more affluent visitors and tourists. González (Citation2020) points to the danger of these transformations that erode their important role as public meeting places, especially for lower-income groups. Guimarães (Citation2018) has shown, for example, how the lack of will on behalf of the municipality of Lisbon to rehabilitate the city’s markets opened the door to the participation of corporate interests. Although Guimarães does not report evidence of immediate displacement of traders and visitors due to the involvement of private actors, his findings do show that markets would never have been destined to decline if they had received adequate levels of public investments in the first place.

However, displacement does not only operate at a physical level; it can also be symbolic. Studies on place-based displacement of residents, visitors and entrepreneurs in gentrifying (retail) spaces have shown how they can come to experience a sense of estrangement from their surroundings as a result of private redevelopment processes. In a study of the regeneration of a district in Barcelona, Degen (Citation2003) concludes that public spaces can be redeveloped in ways that are devoid of immediate physical exclusion, but still work to symbolically exclude those who do not appear to belong in the newly formed ‘sense-scapes’. Since the redevelopment of markets often facilitates the appropriation of public space by hegemonic agents whose main interests are to accommodate the demands and needs of new high-income visitors and residents (Van Eck Citation2021), the provision of new products and cultural tastes is at risk of being perceived by long-standing users of public space as a threat to their own way of living and affordances (Tartari, Pedrini, and Sacco Citation2021).

For others, the reinvention of public spaces is not necessarily a condition for physical or symbolic exclusion. Banerjee (Citation2001, 15) has argued that an important function of public space is enjoyment, catering to our ‘desire for relaxation, social contact, entertainment, leisure, and simply having a good time’. For Banerjee, it does not matter whether this function of entertainment and leisure takes place in a public or private space (Carmona Citation2010). Similarly, Leclercq and Pojani (Citation2021) study of various privatized public spaces in Liverpool, the United Kingdom, indicates that users often appreciate these areas for the clean and entertaining environment they offer. They conclude that private spaces can often be characterized as vital social spaces in which people engage in daily encounters.

The degree of access to the governance process is the second main source of debate among researchers. As has become clear, governments often decentralize power with private actors (including businesses, district commissions, quangos, public-private partnerships, community organizations, etc.) in the expectation of administrative, political and economic returns. The same is true for their partners. Quangos, for example, can receive several benefits from the autonomization trend, such as greater efficiency, better targeting of services to client needs, and increased legitimacy and autonomy. In this sense it could be argued that decentralization processes are more ‘public’ since a plurality of actors – beyond the government – is involved in decision-making and governance (Leclercq, Pojani, and van Bueren Citation2020). However, common criticisms are that when voting rights and decision-making power are shifted away from publicly-elected representatives to private bodies, the risks increase that the interests and needs of local people may be ignored (Geddes Citation2006; Falleth, Hanssen, and Saglie Citation2010).

Incompatibilities between the local government, quangos and the citizenry can thus pose thorny problems for the establishment of horizontal power relations in the management of markets (Miraftab Citation2004). Such unequal power relations can result in a situation where markets become typified by dominant board members of quangos who now bear new responsibility for the regulation and management of the market. When their choices and actions do not reflect the interests and needs of existing traders, residents and visitors, markets can change in ways that make it difficult for (some) of them to use the market as they would like and are used to. These forms of democratic illegitimacy may, in turn, facilitate mechanisms of symbolic and physical exclusion as discussed above.

Yet, even if this might happen, it is important to bear in mind that local governments hold decision-making power to delegate (partial) governance of markets to quangos on their behalf. In fact, the creation of quangos is always authorized by local governmental authorities, which therefore remain accountable for this decision. From this point of view, some crucial questions emerge: how and why have local governments exactly decided to confer management of markets to quangos? And are the advantages of autonomization (for instance, improvement of physical environment or better targeting of visitors’ needs) sufficient to justify the devolution of power from a public to a private body? These questions informed the overarching research question and the subsequent analysis presented in this article.

3. Data and methods

We employed a multimethod approach to study the autonomization of outdoor retail markets in the Netherlands. To analyse and contextualize the motives behind the autonomization of markets in local decision-making processes, we used journalistic accounts, policy reports and press releases. In order to better understand and validate the narratives of the autonomization process, we conducted 15 in-depth interviews with representatives of the national trade union (Centrale Vereniging voor Ambulante Handel, CVAH), board members of quangos, and local administrators and elected officials. For these interviews, we made use of standardized topics, covering the respondents’ assessments of (municipal) rules and regulations pertaining to markets, the choice of autonomization as a governance form over others, and the relationship between autonomization and the everyday activities of traders in markets.

We also draw on ethnographic research carried out as part of an international research collaboration that comprises a comparative study of outdoor markets in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Switzerland and Spain. Between October 2019 and 2021, we conducted an ethnographic study of the Valkenswaard market to give a sense of the everyday effects of autonomization. Valkenswaard is a small village located in the south of the Netherlands with approximately 31,000 inhabitants. The market takes place every Thursday (from 9 am to 5 pm) and hosts 75 market stalls. The market was autonomized in 2014 and has since then been run by an independent quango in which a number of traders are represented (Stichting Weekmarkt Valkenswaard). Since the establishment of the traders-run quango, the market operates collectively as evidenced by its active social media accounts (such as Facebook and Twitter) and the organization of additional activities on the market to stimulate the market’s festive atmosphere. Valkenswaard was one of the first autonomized markets in the Netherlands and is generally seen as a success story.

At least once per month, with the exception of lockdown periods in the COVID-19 pandemic, the first author spent three to four hours at this market. This resulted in about 50 h of participant observation. In addition, approximately 30 unstructured interviews with traders were conducted on site. The conversations revolved around their own views on the market and its everyday management, their daily activities, and the likes and dislikes of market trading. All quotes in this paper were translated from Dutch by the authors. To respect the respondents’ anonymity, we refer to their profession instead of using their real names.

4. The development of autonomized markets in the Netherlands

Many research agencies, governmental bodies and newspapers have written about the decline of market trading in the Netherlands due to an aging trader population and the competition of big retail platforms and supermarkets. Although the net turnover rates of the ambulant trade sector show an upward trend, especially the non-food branches (such as textile and clothing) suffer from continuous declining turnover rates (CBS Citation2017). In order to turn the tide, the former Dutch Interest Organization for Retail (Hoofdbedrijfschap Detailhandel; HBD) emphasized the need to manage markets in more ‘entrepreneurial’, ‘business-like’ and ‘customer-oriented’ ways in contrast to the existing dominant model of governing markets. In this traditional governance model, municipalities have sole authority over the ownership and management of markets, whereby they issue (temporary and permanent) licenses to individual traders.Footnote2 These licenses allow traders to work against the payment of market rents and under the condition that they adhere to specific rules as outlined in municipal Market Statutes.

In 2007, HBD launched a report entitled ‘The market has a future’ in which expected and desired visions of the future were outlined. One of the most important expected trends was the increased role of private parties in the management of markets:

Involving private parties in the organization can improve the quality and resilience of markets in the future. We can learn a lot from the ways in which shopping malls are managed, for example in relation to the recruitment of new entrepreneurs and the optimalization of retail mixes and shopping routes. Moreover, an independent, private, manager can impose higher demands on (the quality of) traders. (HBD Citation2007, 9)

At the same time, HBD cautioned against a market-based governance model in which private parties fully own and manage markets. This could result in higher market rents and therefore homogenization of product demand (HBD Citation2007, 10). Moreover, as HBD outlined in a later publication (HBD Citation2010, 13), for-profit private organizations benefit from an efficient market organization, which might result in a situation where ‘their own interests take precedence over public interests’. The best solution was found in a ‘hybrid public-private-like management form’ (HBD Citation2007, 9) in which the municipality remains the owner of the market terrain, but devolves management responsibilities to non-profit private parties. The idea of establishing traders-run quangos to reach this goal emerged in 2010 in close collaboration with the national trade union.

For this idea, there has not been any direct or indirect reference to the international model of BIDs, for instance through promotional activities of some international ‘transfer agents’ (McCann and Ward Citation2013). Instead, HBD and CVAH referred to the context of declining market trade numbers while contrasting this situation with the economically successful conduct of private shopping malls and supermarkets. The market manager of Valkenswaard explained that this idea also fits in a longer national trend of municipal retrenchement to reduce public expenditures (see Hendriks and Tops Citation2003): ‘Municipalities had to cut back on many different terrains due to the economic crisis [of 2008], from football clubs and libraries to swimming pools. In the same vein, [reducing] municipal costs for market management has become a target’ (Binnenlands Bestuur Citation2019). In this sense, the devolution of power over the management of markets to private organizations should be considered as a response to the contextual needs of several actors instead of being part of a predetermined neoliberal policy model (see Kizildere and Chiodelli Citation2018). Yet, at the same time, this shift has happened in a longer process of ‘neoliberalization’, where principles of deregulation, decentralization and contractual role divisions between the public and private sector have become dominant governance tools since the 1980s (Heurkens and Hobma Citation2014).

In 2010, HBD and CVAH launched two pilot projects to experiment with autonomization as the new governance model to minimize management costs and attract more visitors. HBD and the trade union entered into an agreement with two municipalities, respectively the City of Amsterdam and the Municipality of Haaksbergen, a small town located in the east of the Netherlands. On the basis of these pilot projects, Amsterdam agreed to establish a completely new market with a new governance structure (Siermarkt), whereas Haaksbergen decided to change the governance structure of its already existing central market.

In both locations, quangos were established in which traders are self-organized. The Municipality of Haaksbergen dissolved both its existing market regulations and all licenses of traders. Accordingly, it entered into a cooperation agreement with the newly established quango. Decisions on managerial freedom are laid down in this agreement between the municipality and quango, thereby giving the latter legal authority to manage markets. Measures include rules and regulations pertaining to the selection of new traders who want to sell on the market, desired behaviours, cleaning standards, hygiene measures, spatial distribution of market stalls, and the physical appearance of the market (see for example cooperation agreement Municipality of Valkenswaard Citation2014).

In July 2012, the liberal conservative party VVD applauded the success of the new autonomized market in Amsterdam and presented a proposal carrying the name ‘Leave it to the market’ to Amsterdam City Council (Municipality of Amsterdam Citation2014, 6). In this document, the party recommends to autonomize all markets in the city as the standard governance model. In 2020, the Social Liberals (D66) dusted off VVD’s proposal in an opinion article entitled ‘Help the market with less rules!’, again urging the municipality to stimulate autonomization because of the perceived – yet unspecified – ‘innovative private initiatives’ that evolve in self-governed market structures (D66 Citation2020). In this period of time, three more autonomized markets have been established in Amsterdam, including the upscale and biological Pure Markt, ZuiderMRKT, and Zuidas Markt. These markets can be characterized as festival marketplaces, selling (among others) ‘juicy burgers’, ‘fresh oysters with a glass of bubbly’, and ‘cold beers’ (https://puremarkt.nl/). The role of the local government, in the view of the (liberal) parties, is to promote these sorts of markets that contribute to the symbolic marketing of the city as ‘creative’ and ‘vibrant’; characteristics that specifically cater to the consumption needs and choices of more affluent city residents.

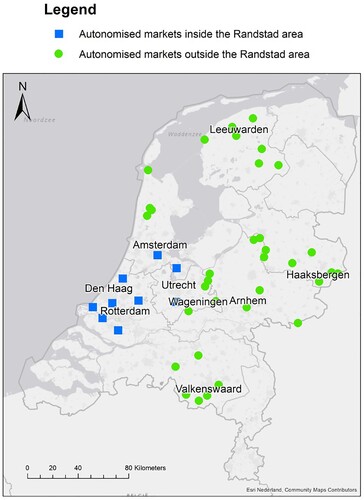

Notwithstanding these developments in Amsterdam, the autonomization process has especially gained traction in the not-so-urban areas of the Netherlands. Out of the total number of 51 autonomized markets, only 12 are located in the Randstad metropolitan area (the polycentric urban region encapsulating the four biggest cities in the Netherlands: Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht). This spatial distribution of autonomized markets () is not a coincidence, but the result of active lobbying practices by several dominant actors.

Figure 1. Map of autonomized markets in the Netherlands. Based on data from the Markt van Morgen (2021).

The board members of Haaksbergen’s newly established quango were particularly active in sharing information about the successes of autonomization throughout the region. In an interview, a board member explained that traders and municipal actors of surrounding villages started to visit the market in Haaksbergen to gain knowledge about autonomization. Based on the emergent discussions, the trade union decided to establish a subsidiary foundation in 2012, called De Markt van Morgen (DMvM, the Market of Tomorrow). This foundation joins up and supports market traders and municipal actors in the process towards autonomization, while promoting this trend throughout the country.

Uitermark and Duyvendak (Citation2008, 116) call this ‘institutional mirroring’, referring to the process through which ‘adherents of a certain discourse seek to create institutions that reflect its assumptions and conceptions’. Since 2012, DMvM has autonomized approximately 80% of all markets in the Netherlands as visualized in . Asking one of DMvM’s board members why most of these markets are located in not-so-urban areas, he responded:

The reason is probably the comprehensive governmental apparatuses that surround [urban] markets. In cities, there are so many people, so many civil servants – market managers, community service officials — involved in [the management of] markets. As soon as these markets are spun off [after autonomization], what will happen to these jobs? In smaller places, there are no [separate] municipal departments for market affairs. … So, the autonomization of markets in towns and villages is easier and faster.

Whereas Brenner and Theodore (Citation2002, 368) have noted that cities are the most ‘important geographical targets’ for restructuring processes of neoliberal policy experiments, the findings show that the autonomization of markets has especially taken place in not-so-urban areas. In addition to the extensive regional exchange of information about autonomization in not-so-urban areas, this could also be explained because the (partial) dismantling – or ‘rolling back’ (Brenner and Theodore Citation2002, 362) – of extant governmental arrangements encounters less institutional barriers and friction in not-so-urban areas.

5. Motivations behind autonomization

Above, we have shown how autonomization has spread throughout the Netherlands as a result of institutional mirroring and site-specific lobbying practices to counteract the declining turnover rates and cost inefficiency of many ‘traditional’ municipality-owned and -managed markets. However, this only provides us with a general idea of how the identified problems of markets are institutionally dealt with. It does not tell us what kind of framing takes place and how a sense of urgency has been generated among institutional actors. Below, we exhibit how DMvM board members, policy makers and market managers made use of three different but interrelated motivations to justify the autonomization of markets.

First, interviewed institutional actors pointed to the importance of the liberation of ‘traditional rules’ and associated ‘demunicipalization’ of market management. Here, the trade union notes that ‘in many municipalities market management is part of the department of permits and enforcement’ where ‘[t]oo little policy attention is paid to the [economic] functioning of the market’ (DTNP Citation2018, 18, 20). A board member of DMvM echoed this statement, arguing that municipal departments generally do not have ‘affinity’ with markets and do not provide ‘quality standards’ for their development. Qualifying the work of market managers on municipality-owned markets, he expounded (emphasis added): ‘Don’t be mistaken, municipal market managers are no ‘real’ market managers. In most cases they are simply law enforcers […] There’s no long-term vision. There’s no rule that proclaims: ‘If you [market trader] don’t contribute to the collective success of the market, there’s no place for you’. The main characteristic of autonomization is captured most precisely in this statement. It transforms the problem of ‘unsuccessful’ markets and traders into one that has less to do with the provision of material resources than with a lack of entrepreneurial skills and responsibilities (Van Eck Citation2021).

Importantly, not only the trade union and DMvM argue that municipal rules and regulations are incompatible with the entrepreneurial management of markets. Municipalities themselves also make use of this line of reasoning to explain the need for autonomization. Motivating the decision to autonomize the weekly market of Valkenswaard, a former policy maker working for the department of Economic Affairs wrote to the municipal council that the ‘sluggish administrative procedures of the municipality block the economic potentialities of the market’. This follows a clear anti-red tape rhetoric, which sees state bureaucracies and regulation as the main obstacles to business-friendly markets.

Second, and closely related to the deregulation and outsourcing of municipal tasks, is the argument that the autonomization of markets is financially beneficial. In most cases, markets that are owned and managed by municipalities are not breakeven, meaning that the revenues generated from market rents do not cover the costs to organize and manage markets. Such costs include, among others, the cleaning of the market square, hiring of a market manager, and maintaining/repairing technical installations. The contracting out of these tasks to quangos significantly reduces municipal expenditures. According to the market manager of Valkenswaard, the quango is way more efficient in cleaning the market square and maintaining technical installations. In an interview, he noted that the quango saves 30,000 euros on cleaning costs each year, money they now use for marketing and promotion.

Third, there is a general tendency to represent market trading as a rather old-fashioned and outdated profession that should transition to the flexible, service-based industry of the last decade. In the Netherlands, this representation is closely aligned with the ‘seniority principle’ of contract systems that municipalities generally use in Market Statutes to select new market traders. According to this principle, market traders acquire more rights (such as favourable market spots or permanent permits) based on the length of trading on the market (see Van Eck, van Melik, and Schapendonk Citation2023). Being critical of this principle, a board member of the trade union derided the seniority system as an ‘old fashioned principle that blocks innovation on the market’. In contrast, quangos can develop their own criteria with regard to the selection of new traders. This allows, as argued by a board member of Haaksbergen’s quango, for a more flexible allocation of ‘non-traditional’ traders selling and providing new products and service activities:

Many established family businesses die out eventually. That’s because this traditional generation hasn’t adjusted to the online and service-oriented world. I’m convinced that many markets can become more attractive and stronger. Think of hairdressers, for example. In Leeuwarden [autonomized market in the northern part of the country], there’s a mobile stand where a hairdresser works. … He has a great location in the city center and only pays 15 euros on market rent [each day]. He’s laughing all the way to the bank. By doing things like this, you can make markets interesting again. It’s a real niche.

In sum, a wide variety of actors make use of different, yet closely associated, motives to show how autonomization is effective. Through the citation and re-citation of these motives, autonomization has actualized itself more and more, and consequently autonomization seems to have become a valid governance form of markets.

6. Implications of autonomization

The different strands of motivations discussed above lead to a situation in which autonomization is judged on the basis of how well it can be presented to (prospective) partners and municipalities instead of on the basis of its effects on participation and inclusion. However, our findings show that while autonomization is being pushed forward as ‘the’ solution to declining market trade, it certainly also facilitates mechanisms of symbolic and physical exclusion. This applies both to the management and daily organization of the market.

The process towards autonomization always starts with the creation of a working group to find support for the autonomization of the market. According to a DMvM board member, this working group consists of: (1) approximately six invited market traders who are in most cases members of already existing market committees; (2) a policy maker and/or deputy mayor of the municipality; and (3) a representative of local shopkeepers. During several sessions, the working group not only deliberates about the favourable solutions that autonomized markets might offer, but it also negotiates new rules, develops new norms with regard to access to, and appropriate behaviour on, the market, and devises new conceptions of legitimate municipal intervention.

An interviewed legal advisor explained that the democratic dilemma of autonomization is predominantly linked to this first stage of working group sessions, which includes the formulation of a new market management plan up until a final proposal is submitted for approval to the local government. In most cases, the negotiations take place behind closed doors, neither accessible to the general public nor to most of the traders, thereby limiting public or democratic transparency and accountability (Geddes Citation2006; see also Falleth, Hanssen, and Saglie Citation2010). Although all traders are invited during the final working group session to vote for the quango’s board by means of show of hands, a DMvM representative acknowledged that only the most ‘engaged’ traders who have been involved in all working group sessions eventually end up in representing the board. Importantly, this implies that participation of all traders is reduced to opposition to the proposed autonomization plans, where the main content has already been agreed upon between DMvM, municipal actors and the (prospective) board members of the new quango. A board member of Valkenswaard’s quango explained that the board – existing of five middle-aged men – came into existence ‘quite tacitly’ this way, and gets extended every three years since ‘only a few traders are interested to become board member’.

The case of the failed autonomization process of the market in Wageningen, a small city in the centre of the Netherlands, further exemplifies that autonomization sometimes lacks democratic legitimacy. Commissioned by the audit of the Municipality of Wageningen, research by Bastiaans, Franssen, and Kusters (Citation2015, 21) has shown that attendance of the working group sessions by traders was extremely limited (less than 20 per cent). During the final vote for the quango’s board, only seven out of 50 traders were present, who would all serve on the board. Based on a small sample survey research, it turned out that only 12 per cent of the traders actually agreed with the autonomization of the market, meaning that a 50 per cent acceptance rate for autonomization as proposed by the municipality was not reached (Bastiaans, Franssen, and Kusters Citation2015, 23). Accordingly, the plan for autonomization was cancelled.

The asymmetry between board members of the quango and traders has resulted in instances of unequal power relations and alleged forms of conflicts of interests. This became evident during a dispute on the autonomized market of Arnhem, a middle-sized city located east of Wageningen. In 2019, a market trader applied for a selling location on the market that had been created after a buyout initiated by the quango’s board. The quango refused to allocate the trader to this location, as the market already had too many stalls in the market branch of the applying trader. As a response, the trader accused the board of ‘abuse of power’ and ‘favoritism’ and demanded immediate financial accountability (De Gelderlander Citation2019). Commenting on this conflict, a municipal councillor commented:

Before, the municipality devised the rules. Now [after autonomization], we no longer have an objective entity that can interfere when a conflict of interests occurs. When something goes wrong on the market, it is very likely that the board of traders gets accused of conflict of interests, or at least gives semblance of it, even when the board acts with integrity. (De Gelderlander Citation2019)

As soon as the Market Statute gets dismantled, you simply transfer power. This means that the municipality has less control over the market. … We have less sight into the functioning of the board. … Very often, you see that 50-year-old men, who have been selling on the market for generations, become board members. Or the Spakenburg-clique [referring to traders working in capital-intensive fish businesses] gets in charge. That can result in a situation where young, starting entrepreneurs with very good ideas can no longer access the market.

However, these findings do not exclude the fact that instances of favouritism and abuse of power do not occur on municipality-owned and -managed markets. In 2010, seven market managers of municipal markets in Amsterdam got arrested for fraud and bribery when they allocated certain traders to the best market locations in exchange for money. Because these market managers were part of the municipal department of market affairs, the municipality could directly respond and reorganize by implementing a rotation system for market managers in an effort to curb corruption (Het Parool Citation2010). The municipal officials of Arnhem and Nijmegen warn that it is more difficult on autonomized markets to directly intervene when such practices of exclusion occur, since quangos are placed outside the influence of the political arena.

During our field observations in Valkenswaard, we also came across other examples of exclusion, which are related to particular qualifications for entry to autonomized markets which go beyond mere registration at the municipal department. For example, when a Belgian trader pitched his business plan to the quango’s board in Valkenswaard, he was asked to come up with different arguments why he would be a ‘qualitative’ complement to the market. He replied that he would be the only trader selling a wide range of fruit syrups, including sorts that are only available in Belgium and not in the Netherlands. To strengthen this argument, he said: ‘And I already have everything I need: a table and parasol, that’s all!’ The latter argument apparently dissatisfied one board member, who responded: ‘That’s not how it works here. You have to rent a proper tent for this type of business, which is not the same as a simple table and parasol’ (Fieldnotes, emphasis added).

Also more subtle forms of exclusion can be observed as a result of the strategy of creating a festive sense scape. With board members often only representing a part of the traders as described above, there is a risk that traders do not support new initiatives organized at the market. With respect to the weekly artists performing at the Valkenswaard market, such as Los del Sol described in the introduction, a trader complained: ‘We have different entertainers each week. But this particular one [a man dressed in black costume with golden stripes singing songs of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Simon & Garfunkel] has already performed four, five times here’. After a short pause, the trader continued: ‘You know, he sings at a distance now, but if he comes closer, it disrupts my sales. I can hardly make myself heard’. This view is certainly not shared by all; other traders indicated that they like the convivial atmosphere the performers and artists bring, and emphasized that the weekly performances and festivities help attract a high number of Belgian tourists and families that spend considerable money on the market. Moreover, our observations show that market visitors also seem to enjoy the performances, as a crowd gathered around the artist and two women even started dancing on the music ().

This indicates that autonomized markets remain important social spaces in which visitors engage in lively encounters and enjoy the created shopertainment. While privately managed spaces are oft-criticized in academic literature, this result indicates that autonomized public spaces can be a valuable means to revive central public spaces in towns and cities. This conclusion is in line with the findings of Leclercq and Pojani (2020) who studied the user experiences of three privatized public spaces in Liverpool. Yet, for traders, autonomization can lead to inequalities to access the market and its governance process. The latter relates to the creation and nature of quangos, which in the current form constraints possibilities for all traders to democratically participate. The latter is related to the creation of a festive sense scape. This is built on entrepreneurial and business-like strategies that concretely redefine markets in such a way that they can physically (in the case of the Belgian trader) and symbolically (the complaining trader) exclude traders, and possibly also visitors.

7. Discussion and conclusions

After years of governmental disinvestments across Europe, markets have lately been rediscovered as potential key drivers of change in terms of economic development and regeneration (Guimarães Citation2018; González Citation2020). While certain – often urban – markets experience a resurgence in the Netherlands, other not-so-urban markets show signs of decay (DTNP Citation2018). Especially the non-food sector suffers from declining turnover rates, a trend that has only been worsened by the coronavirus lockdowns and restrictions (Van Eck, van Melik, and Schapendonk Citation2020). The dominant solution for the revival of markets has been found in ‘autonomization’, a managerial governance principle that delegates responsibilities for the management of markets from the local government to non-profit, traders-run quangos.

This paper has shown that autonomization is framed as having many advantages: within the dominant discourse, traders’ quangos are considered to be more professional, cost-efficient and flexible in contrast to the ‘traditional’ and ‘sluggish’ rules of municipalities managing markets. We have shown how autonomization has gained influence through ‘institutional mirroring’ (Uitermark and Duyvendak Citation2008) and site-specific lobbying practices in the context of declining trade numbers and a longer process of neoliberalization in which municipalities have increasingly adapted principles of deregulation and decentralization to reduce public expenditures and become more cost-efficient (Heurkens and Hobma Citation2014). Yet, it is important to note that institutional proponents cautioned against a fully market-based governance model in which private for-profit parties both own and manage markets. They argued that this could result in higher market rents and homogenization of public space; forms of direct exclusion and commodification that also many scholars have criticized (e.g. Sorkin Citation1992; Low and Smith Citation2006; Loughran Citation2014).

Instead, the former Dutch Interest Organization for Retail (HBD) and the national trade union started to experiment with a ‘soft’ form of privatization in which local governments remain the owners of the market, yet devolve responsibilities for its management to traders-run quangos. Through this process, management has become indeed more cost-efficient through which additional events, such as live music and street comedy, can be financed. Our fieldwork in the autonomized market of Valkenswaard confirms that visitors seem to enjoy the shopping and entertainment opportunities that this governance model provides (see also Leclerq and Pojani 2020).

Yet, we also observed instances of exclusion with regard to access to markets and their governance process, especially for market traders. Some traders – which was the case in Valkenswaard – are neither interested nor qualified to make a meaningful contribution to the governance of markets. This can result in a chasm between the interests and decisions of the quango board and the rest of the traders, such as the case of Wageningen has illustrated. Moreover, the conflict on the market in Arnhem has made clear that these claims ignore the structural inequalities and instances of favouritism that can emerge in quango boards that make it difficult for all traders to get their arguments heard, and that privileges long-established traders who are able to articulate their interests in the management of markets (see Geddes Citation2006). In order to enhance the political acceptance of autonomization, and to minimize the asymmetry in resources available for participation, we would argue that public hearings on autonomization should be accessible to all market traders right from the start. Indeed, as argued by Falleth, Hanssen, and Saglie (Citation2010, 749): ‘A minimum prerequisite [for democratic legitimacy] is that all relevant arguments are available when decisions are actually made, in order to argue for the final weighting of arguments towards those affected’.

With regard to access to public space, we have shown that autonomized markets such as Valkenswaard have a certain festive sense-scape (Degen Citation2003) where street musicians and comedians turn the market into a thematized ‘party’ rather than a place to mainly congregate or buy groceries. Future research could provide more structural insights into how existing traders and customers of autonomized markets value these forms of shopertainment or that they mainly serve a different – more affluent and tourist-oriented – audience. We would like to re-iterate Degen’s (Citation2003, 879) argument that exclusion or inclusion of markets is fostered through the experience of public space, where the imposition and control of new practices as articulated by quango boards are often disguised as, and justified by, entrepreneurial innovation and thematization. Even though self-management appears very democratic, new forms of public space management come with new in- and exclusionary mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewer(s) and editors, our colleagues of the MMP project, and in particular Joris Schapendonk, for their comments and suggestions. Many thanks also to DMvM for providing us with geographical data on autonomized markets in the Netherlands, as well as to Kevin Raaphorst for his invested time in creating the corresponding map.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Moving MarketPlaces (MMP): Following the Everyday Production of Inclusive Public Spaces. For more information, see: https://fass.open.ac.uk/research/projects/moving- marketplaces.

2 Since the introduction of an EU-law, municipalities are no longer allowed to issue permanent contracts to market traders. On this issue, see Van Eck, van Melik, and Schapendonk (Citation2023).

References

- Banerjee, T. 2001. “The Future of Public Space: Beyond Invented Streets and Reinvented Places.” Journal of the American Planning Association 67 (1): 9–24. doi:10.1080/01944360108976352.

- Barker, A. 1982. Quangos in Britain. London: MacMillan.

- Bastiaans, G., R. Franssen, and E. Kusters. 2015. “Onderzoek naar het proces van verzelfstandiging van de warenmarkt in Wageningen” [Study of the autonomization of the retail market in Wageningen]. https://adoc.pub/hierbij-bieden-wij-u-de-bestuurlijke-nota-aan-van-het-onderz.html

- Binnenlands Bestuur. 2019. “Gemeenten geven markt uit handen” [Municipalities autonomize markets]. Binnenlands Bestuur, March 8.

- Brenner, N., and N. Theodore. 2002. “Cities and Geographies of “Actually Existing Neoliberalism”.” Antipode 34 (3): 349–379. doi:10.1111/1467-8330.00246.

- Carmona, M. 2010. “Contemporary Public Space: Critique and Classification, Part One: Critique.” Journal of Urban Design 15 (1): 123–148. doi:10.1080/13574800903435651.

- CBS. 2017. “Werknemers- en ondernemerskenmerken markthandel” [Characteristics of employees and employers in market trade]. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/maatwerk/2017/48/maatwerk-brancheverenigingen-cvah-rapport-december-2017

- Clough, N., and R. Vanderbeck. 2006. “Managing Politics and Consumption in Business Improvement Districts: The Geographies of Political Activism on Burlington, Vermont’s Church Street Marketplace.” Urban Studies 43 (12): 2261–2284. doi:10.1080/00420980600936517.

- D66. 2020. “Help de Markt Met Minder Regels!” [Help the Market with Less Rules!]. https://amsterdam.d66.nl/opinie-help-de-markt-met-minder-regels/

- De Gelderlander. 2019. “Politiek ‘voorzichtig’ bezorgd over kemphanen op de Arnhemse market” [Political Worries About Doves on the Market in Arnhem]. De Gelderlander, May 5. https://www.gelderlander.nl/arnhem/politiek-voorzichtig-bezorgd-over-kemphanen-op-arnhemse-markt~abc6c1bd/?cb=52eb351c9c21afb1eb728fe116e34696&auth_rd = 1

- De Magalhães, C. 2010. “Public Space and the Contracting-Out of Publicness: A Framework for Analysis.” Journal of Urban Design 15 (4): 559–574. doi:10.1080/13574809.2010.502347.

- Degen, M. 2003. “Fighting for the Global Catwalk: Formalizing Public Life in Castlefield (Manchester) and Diluting Public Life in el Raval (Barcelona).” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27: 867–880. doi:10.1111/j.0309-1317.2003.00488.x.

- Dovey, K. 2016. Urban Design Thinking: A Conceptual Toolkit. London: Bloomsbury.

- DTNP. 2018. “Proeven & Ontmoeten: Cijfers en achtergronden ambulante handel” [Taste & Meet: Numbers and Background Characteristics of Ambulant Trade]. https://www.retailinsiders.nl/docs/1ec0fd29-7de9-4802-8180-c858e2469ce4.pdf

- Falleth, E., G. Hanssen, and I. Saglie. 2010. “Challenges to Democracy in Market-Oriented Urban Planning in Norway.” European Planning Studies 18 (5): 737–753. doi:10.1080/096543110036077729.

- Geddes, M. 2006. “Partnership and the Limits to Local Governance in England: Institutionalist Analysis and Neoliberalism.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 30 (1): 76–97. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2006.00645.x.

- González, S. 2020. “Contested Marketplaces: Retail Spaces at the Global Urban Margins.” Progress in Human Geography 44 (5): 877–897. doi:10.1177/0309132519859444.

- Guimarães, P. 2018. “The Transformation of Retail Markets in Lisbon: An Analysis Through the Lens of Retail Gentrification.” European Planning Studies 26 (7): 1450–1470. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1474177.

- HBD. 2007. “De markt heeft toekomst: Trends en toekomstbeelden van de warenmarkt in 2015" [The Market Has a Future: Trends and Future Scenarios of Retail Markets in 2015]. https://docplayer.nl/132236-De-markt-heeft-toekomst.html

- HBD. 2010. “De Markt van Morgen: Werkboek voor een vernieuwde of nieuwe markt” [The Market of Tomorrow: Workbook for a Renewed or New Market]. https://irpcdn.multiscreensite.com/df23a9fe/files/uploaded/Werkboek_oprichtingsproces_nieuwe_markt_november_2010_compleet.pdf

- Hendriks, F., and P. Tops. 2003. “Local Public Management Reforms in the Netherlands: Fads, Fashions and Winds of Change.” Public Administration 81 (2): 301–323. doi:10.1111/1467-9299.00348.

- Het Parool. 2010. “Corruptie op alle markten in Amsterdam” [Corruption on all markets in Amsterdam]. Het Parool, December 2.

- Heurkens, E., and F. Hobma. 2014. “Private Sector-led Urban Development Projects: Comparative Insights from Planning Practices in the Netherlands and the UK.” Planning Practice and Research 29 (4): 350–369. doi:10.1080/02697459.2014.932196.

- Kizildere, D., and F. Chiodelli. 2018. “Discrete Emergence of Neoliberal Policies on Public Space: An Informal Business Improvement District in Istanbul, Turkey.” Urban Geography 39 (5): 783–802. doi:10.1080/02723638.2017.1395611.

- Leclercq, E., and D. Pojani. 2021. “Public Space Privatisation: Are Users Concerned?” Journal of Urbanism 0 (00): 1–18. doi:10.1080/17549175.2021.1933572.

- Leclercq, E., D. Pojani, and E. van Bueren. 2020. “Is Public Space Privatization Always Bad for the Public? Mixed Evidence from the United Kingdom.” Cities 100: 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2020.102649.

- Loughran, K. 2014. “Parks for Profit: The High Line, Growth Machines, and the Uneven Development of Urban Public Space.” City & Community 13: 49–68. doi:10.1111/cico.12050.

- Low, S., and N. Smith. 2006. The Politics of Public Space. London: Routledge.

- McCann, E., and K. Ward. 2013. “A Multi-Disciplinary Approach to Policy Transfer Research: Geographies, Assemblages, Mobilities and Mutations.” Policy Studies 34 (1): 2–18. doi:10.1080/01442872.2012.748563.

- Miraftab, F. 2004. “Public-Private Partnerships: The Trojan Horse of Neoliberal Development?” Journal of Planning Education and Research 24: 89–101. doi:10.1177/0739456X04267173.

- Mörçol, G., A. Vollmer, and D. Mallinson. 2022. “Business Improvement District Enabling Laws in the United States and Germany: A Comparative Analysis of Policy Learning.” Urban Affairs Review 58 (4): 1096–1123. doi:10.1177/10780874211025551.

- Municipality of Amsterdam. 2014. “Markten op afstand” [Autonomized markets]. https://adoc.pub/gemeente-amsterdam-1.html

- Municipality of Valkenswaard. 2014. “Samenwerkingsovereenkomst Weekmarkt Valkenswaard” [Cooperation agreement Market Valkenswaard]. https://docplayer.nl/36275502-Samenwerkingsovereenkomst-weekmarkt-valkenswaard.html

- Peyroux, E. 2012. “Legitimating Business Improvement Districts in Johannesburg: A Discursive Perspective on Urban Regeneration and Policy Transfer.” European Urban and Regional Studies 19 (2): 181–194. doi:10.1177/0969776411420034.

- Sorkin, M. 1992. Variations on a Theme Park: The New American City and the End of Public Space. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Stein, C., B. Michel, G. Glasze, and R. Pütz. 2017. ““Learning from Failed Policy Mobilities: Contradictions, Resistances and Unintended Outcomes in the Transfer of “Business Improvement Districts” to Germany.” European Urban and Regional Studies 24 (1): 35–49. doi:10.1177/0969776415596797.

- Tartari, M., S. Pedrini, and P. Sacco. 2021. “Urban ‘Beautification’ and its Discontents: The Erosion of Urban Commons in Milan.” European Planning Studies 0: 00. doi:10.1080/09654313.2021.1990215.

- Uitermark, J., and J. Duyvendak. 2008. “Citizen Participation in a Mediated Age: Neighbourhood Governance in The Netherlands.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 32 (1): 114–134. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2007.00743.x.

- Van Eck, E. 2021. ““That Market has No Quality”: Performative Place Frames, Racialisation, and Affective Re-inscriptions in an Outdoor Retail Market in Amsterdam.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 47 (2): 547–561. doi:10.1111/tran.12515.

- Van Eck, E., R. van Melik, and J. Schapendonk. 2020. “Marketplaces as Public Spaces in Times of the Covid-19 Coronavirus Outbreak: First Reflections.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 111 (3): 373–386. doi:10.1111/tesg.12431.

- Van Eck, E., R. van Melik, and J. Schapendonk. 2023. “The Multi-Scalar Nature of Policy im/Mobilities: Regulating ‘Local’ Markets in the Netherlands.” In Marketplaces: Movements, Representations and Practices, edited by C. Sezer and R. van Melik, 150–160. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781003197058-13.

- Van Melik, R., I. van Aalst, and J. van Weesep. 2009. “The Private Sector and Public Space in Dutch City Centers.” Cities 26: 202–209. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2009.04.002.

- Van Melik, R., and E. van der Krabben. 2016. “Co-production of Public Space: Policy Translations from New York City to the Netherlands.” Town Planning Review 87 (2): 139–158. doi:10.3828/tpr.2016.12.

- Van Thiel, S. 2004. “Quangos in Dutch Government.” In Unbundled Government: A Critical Analysis of the Global Trend to Agencies, Quangos and Contractualism, edited by C. Pollitt and C. Talbot, 167–183. London: Routledge.

- Watson, S. 2009. “The Magic of the Marketplace: Sociality in a Neglected Public Space.” Urban Studies 46 (8): 1577–1591. doi:10.1177/0042098009105506.

- Zamanifard, H., T. Alizadeh, and C. Bosman. 2018. “Towards a Framework of Public Space Governance.” Cities 78: 155–165. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2018.02.010.