ABSTRACT

Pressing sustainability challenges and increased influence of neoliberal ideas in planning have resulted in strong demands to ‘speed up’, and increase efficiency in, planning processes. Meanwhile, the reported risks that such emphasis on speed have for participatory decision-making and continuous calls for increased deliberation in planning, following the ideas of communicative planning theory, suggest that planning processes ought to ‘slow down’. These dual pressures for swift and slow planning have been discussed within Nordic planning studies as an ‘either-or’ tension by which decision-making processes are either swift yet exclusive and technical-based and/or market-driven or participatory and deliberative but time-consuming. This paper provides insights into how deliberative planners navigate the double pressure for swift and slow planning in the design of participatory planning processes. It is based on a case study in Uppsala, Sweden where demands for swift decision-making and for participation following deliberative ideals were noticeable. The case study shows planners striving in different ways to balance the contradicting demands for swift and slow planning through their process design choices. These findings provide inspiration to reimagine the deliberative turn in planning as a ‘balancing act’ between equally important demands for participation and deliberation, and for faster and more efficient planning.

Introduction

Planners are increasingly challenged by a double pressure caused by seemingly contradictory demands for ‘swift’ and ‘slow’ planning processes. On the one hand, increased involvement of private actors along the lines of neoliberal agendas and New Public Management plus the need to meet urgent sustainability challenges such as rapid urbanization, housing shortages, climate change or pressing socioeconomic problems, have resulted in pressures to ‘speed up’ decision-making in order to deliver faster results (Mäntysalo et al. Citation2015; Falleth, Hanssen, and Saglie Citation2010; Falleth and Saglie Citation2011). On the other hand, the reported risks that such emphasis on speed have for participatory decision-making (Niitamo Citation2021; Grange Citation2017; Metzger et al. Citation2016), in addition to calls for deliberative processes that can revitalize democracy in planning (Innes and Booher Citation2016; Mellanplatsprojektet Citation2013), suggest that planning ought to slow down.

The double pressure for swift and slow planning, has caught great attention in Nordic planning research over the last decade. Complaints about slow and inefficient planning processes and the need to address urgent challenges through swift decision-making have been at the centre of political debates and revisions of planning legislation and procedures. However, Nordic planning scholars have found that the emphasis on swift processes often prioritizes exclusive, technical-based and market-driven decision-making and works against democratic principles of inclusion and participation upon which most Nordic planning legislation is founded (Grange Citation2017; Niitamo Citation2021; Falleth, Hanssen, and Saglie Citation2010; Falleth and Saglie Citation2011; Sager Citation2009).

In Sweden, the pressure for swift planning has been confronted by scholars who argue that ‘it is in times of crisis when it is especially important not to rush’ (Metzger et al. Citation2016). In other Nordic countries, scholars have equally questioned whether swift processes can be truly justified if they subjugate public participation (Niitamo Citation2021). Such opposition follows an alternative demand for more participation and deliberation in planning, in line with Communicative Planning Theory and its continued call for a ‘deliberative turn’ away from expert-based decision-making.

As in other Nordic countries (Sager Citation2009; Puustinen et al. Citation2017; Fiskaa Citation2005), deliberative ideals have been promoted in Sweden by planning scholars (e.g. Mellanplatsprojektet Citation2013; Stenberg and Fryk Citation2012; Abrahamsson Citation2012) and part of the professional community (see Tahvilzadeh Citation2015). Planning policies and guidelines echo such calls, for example, by advancing the use of ‘citizens dialogues’ (medborgardialog in Swedish), a type of deliberative process encouraged by the National Board of Housing, Building and Planning and the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (Boverket Citation2021; SALAR Citation2019, Citation2011). These dialogues attempt to include the public in discussions, knowledge sharing, co-planning and decision-making. They often occur before and complementary to the legally required consultation period in which planning proposals are made available to concerned stakeholders. In contrast to the demands for swift planning, calls for participation and deliberation (through, e.g. citizen dialogues) imply more time-consuming planning processes (Innes Citation2004; Sager Citation2009; Baker, Coaffee, and Sherriff Citation2007; Brand and Gaffikin Citation2007); that is, they are slow rather than swift.

Nordic planning scholars have shown how the contradicting demands for swift and slow planning often result in an either-or tension between either swift yet exclusive, technical-based and market-driven planning or slow participation and deliberation (Mäntysalo et al. Citation2015; Mäntysalo, Saglie, and Cars Citation2011; Falleth and Saglie Citation2011). Such tension has created increasingly difficult situations for planners; particularly in the design of participatory processes, as planners need to navigate the contradicting demands for swift and slow planning when making process design choices on who gets to participate, how they participate and for which purpose (Sager Citation2009). Being able to handle the double pressure for swift and slow planning is thus a key challenge for the deliberative planners responsible for designing and making choices on the why’s, where’s, when’s and how’s of participation in planning.

The aim of this paper is to provide insights into how deliberative planners are affected by and address the double pressure for swift and slow planning in the design of participatory planning processes. We examine a case study focusing on the design of a citizen dialogue for the redevelopment of a highly populated suburban area in Uppsala, Sweden, including the process design choices made by the deliberative planners managing the process. The case is relevant for our aim as demands for both swift and slow planning were noticeable in the need to address housing shortages and pressing socioeconomic problems, and the municipality’s intention, as well as an external actor’s push, for participation beyond simple consultation.

Our case study complements previous research in Nordic countries in which the double pressures for swift and slow planning have been studied in relation to discursive and legislative tensions between deliberative ideals, including those of communicative planning theory, on the one hand, and neoliberal agendas and New Public Management, on the other (e.g. Grange Citation2017; Falleth and Saglie Citation2011; Falleth, Hanssen, and Saglie Citation2010; Mäntysalo and Saglie Citation2010). Our focus on process design provides concrete insights into how deliberative planners are affected by and navigate the demands for swift and slow planning in their everyday practice.

The following section expands on the deliberative turn in planning in relation to discussions on the double pressure for swift and slow planning in Nordic countries. After describing the data and methods used in the study, the case of the citizen dialogue process for the Gottsunda Programme Plan (GPP) in Uppsala, Sweden, is presented. The case study shows that the contradicting demands of the double pressure were indeed a challenge for planners. Yet, the case also shows planners’ attempts to balance the double pressure through their process design choices. These findings are then discussed, including implications for the deliberative turn in planning.

The deliberative turn and the double pressure for swift and slow planning

Since the 1990s, the deliberative turn in planning has made a significant impact in the development of planning theory and practice. Driven by the ideas of communicative planning theory, the deliberative turn entails a normative shift from rational and hierarchical expert-driven planning towards participatory and deliberative decision-making (Brand and Gaffikin Citation2007). While different streams of communicative planning theory have developed, the initial normative streams of communicative planning theory drew on Habermas’ theory of communicative action and placed planners at the centre of the deliberative turn; shifting their role towards facilitators who design and manage processes that involve a wide range of participants and perspectives, promote face-to-face deliberation around issues of common concern and seek to find solutions through consensus building (Sager Citation2009; Innes and Booher Citation2016).

These normative streams have been followed by critical approaches to communicative planning theory, questioning in great part its Habermasian roots and its ability to address the ‘realpolitik’ of planning (e.g. Westin Citation2022; Brand and Gaffikin Citation2007; Connelly and Richardson Citation2004; Flyvbjerg and Richardson Citation2002). Leading communicative planning scholars responded to the critique by both modifying how they relate to Habermasian ideals and by elaborating on how their respective versions of communicative planning deal, for example, with power and conflicts (see Healy’s sociological institutionalism Citation2005, Citation2003, Innes’ alternative dispute resolution Citation2004; Innes and Booher Citation2016, Citation2015, and Forester’s critical pragmatism, Citation2017, Citation2013). Even so, it is still the Habermasian stream of communicative planning that is linked to the deliberative turn and is brought to the fore in planning discussions, both internationally (e.g. Mattila Citation2020; Westin Citation2022; Innes and Booher Citation2016; Brand and Gaffikin Citation2007) and in Nordic countries (Niitamo Citation2021; Sager Citation2011, Citation2009; Falleth and Saglie Citation2011).

With the increasing influence that neoliberal and market-oriented agendas have in planning and the need to address urgent urban challenges such as rapid urbanization, housing shortages or pressing socioeconomic problems, there have been significant efforts that seek to improve the efficiency upon which planning decisions are made and implemented (Falleth, Hanssen, and Saglie Citation2010; Grange Citation2017; Mäntysalo et al. Citation2015; Mäntysalo and Saglie Citation2010). Efficiency has long been a goal of planning, including participatory planning (Tahvilzadeh Citation2015). In this new context, however, efficiency is associated more with planning processes that allow speedy decision-making and expert-driven and economic-based decisiveness. According to Falleth and Saglie’s (Citation2011) study of the Norwegian planning system, efficiency ‘seems to be regarded simply as a matter of time consumption in the planning process’ where ‘time-consuming political and democratic planning processes are seen as major bureaucratic obstacles, reducing the effectiveness of project planning’ (60). Similar views on efficiency can be seen in other Nordic countries where emphasis has been on reducing institutional and procedural barriers, often in relation to participation, for enabling swift delivery of solutions (Grange Citation2017; Sager Citation2009).

In Nordic planning research, the double pressure for swift and slow planning, has been associated in different ways to discursive and legislative tensions between democracy and efficiency (Falleth and Saglie Citation2011), between input-oriented or output-oriented legitimacy (Mäntysalo, Saglie, and Cars Citation2011), or between the deliberative ideals of communicative planning theory and the neoliberal realities of New Public Management (Sager Citation2009; Mäntysalo et al. Citation2015). Most of these studies conclude with a predominance of swift processes which come at the expense of the democratic ideals advocated in Nordic planning legislation. Such predominance, can even be seen in concrete Nordic urban projects that aimed at enhancing citizen participation, but where efficiency, in the sense of swift decision-making, took precedence over broad involvement, inclusion of dissenting voices, and thorough deliberation of problems and solutions (Metzger, Soneryd, and Linke Citation2017; Niitamo Citation2021).

Studies have also pointed to the difficulties that the double pressure places on planners. Mäntysalo et al. (Citation2015), described the tensions between planning discourses emphasizing faster forms of planning and more time-consuming processes following deliberative ideals as a risk to Nordic planners who ‘may become torn between two opposite directions’ (360). Similarly, Sager (Citation2009) claims that Nordic planners are ‘currently under cross pressure from conflicting values and expectations’ (65) noting the influence that both communicative planning theory and New Public Management play in planning. In her analysis of the Swedish planning system, Grange (Citation2017) considers the neoliberal-driven pressure for speed and efficiency as a democratic problem that threatens to ‘silence’ planners and reduce their discretion to forward participation and the interests of the city.

Nordic research thus predominantly portrays the double pressures for swift and slow planning as two competing and seemingly incompatible demands that result in a tension for either swift yet exclusive, technical-based and market-driven planning or slow participation and deliberation (see also Falleth and Saglie Citation2011; Falleth, Hanssen, and Saglie Citation2010; Mäntysalo and Saglie Citation2010). Similar ‘either-or’ tensions are seen elsewhere, for example in the UK where planning agendas promote participatory planning but also extol the need for swift decision-making without explaining how the two can be made compatible (Brand and Gaffikin Citation2007; Baker, Coaffee, and Sherriff Citation2007).

Communicative planning theory provides little guidance on how planners can navigate the double pressure in their everyday practice (Sager Citation2009). As argued by Metzger, Soneryd, and Linke (Citation2017), the theory was ‘built upon an implicit (and sometimes explicit) promise to deliver both deepened democracy and inclusion and process efficiency by facilitating a continuous, broad dialogue between all relevant stakeholders’ (2524). They claim, however, that deliberative practice has rarely lived up to that promise. A similar claim is made by Tahvilzadeh (Citation2015) who also found that ‘generating efficiency’ is among the main motives for increasing participation in Swedish planning. Efficiency was nonetheless seen as being responsive to the needs and preferences of local residents to avoid opposition and implementation delays, instead of the previously described views of efficiency in terms accomplishing fast decisions with the least amount of time and effort.

The view of generating efficiency by responding to local demands can be easily found in most of the literature promoting communicative planning’s normative ideals. However, efficiency in terms of the time and resources needed in participatory processes has not been in focus. It is rather assumed that these processes require more time and effort than technical-based ones (Sager Citation2009; Innes and Booher Citation2016; Innes Citation2004). Acknowledging that participation will inevitably be more time-consuming, some scholars argue that making participants aware of the returns on the time invested in participatory planning processes is key to successful participation (Baker, Coaffee, and Sherriff Citation2007). Arguably, it is due to the view that communicative planning-based practices are and need to be ‘slow’ (in order to achieve their benefits), that Metzger, Soneryd, and Linke (Citation2017) detect an unresolved tension between communicative planning’s goals of enhancing democracy and pursuing efficient projects through participation.

Some Nordic scholars have suggested ways to handle the ‘either-or’ tensions of the double pressure. Sager (Citation2009) suggests that the task for planners is to perform balancing acts or forge workable compromises between the ideals of participation and time and cost-effective decision-making. However, his balancing act seems to be achieved by emphasizing involvement and dialogue at the expense of efficiency and cost-effectiveness, in line with the Habermasian stream of communicative planning theory. Contrary to this one-sided approach for more participation, Mäntysalo, Saglie, and Cars (Citation2011) see the tensions and incompatibility of the double pressure as a legitimate condition in itself. Hence they propose the idea of ‘agonistic reflectivity’ (following Mouffe’s agonistic pluralism); a kind of reflective meta-communication where the task for planners is to openly acknowledge the tensions of the double pressure and enable political debates and planning processes where their contradictions are continually discussed and addressed in an agonistic manner without actually necessarily being resolved. For Grange (Citation2017), planners’ role should not be to perform balancing acts or create space for reflective meta-communication. Drawing on Foucault’s work on the concept of parrhesia or fearless speech, she suggests that planners should resist and counterbalance the pressure for market-driven efficiency by daring to problematize neoliberal politics and speak truth to power in the interest of others.

This study seeks to examine how planners are affected by and address the above-described tension between swift and slow planning in their everyday practice and explore if this mirrors to the scholarly based suggestions to handle the double pressure.

Data and methods

The case study of the Gottsunda Plan Programme (GPP) and its citizen dialogue process is based on ethnographic research inspired by Forester’s (Citation2013, Citation2017) focus on ‘practice stories’ and its critical pragmatic emphasis on what planners do and how they handle the challenges of their work. Data collection was performed between 2015 and 2017, from the start to the end of the GPP citizen dialogue process. As it is often the case in Sweden, this citizen dialogue process was used for developing the decisions and planning documents for the Gottsunda area, before the law-obliging consultation period. As this study is concerned with how planners’ design of the dialogue processes were affected by and address the tension between swift and slow planning, neither the consultation period, nor the actual results of the dialogue process, in terms of planning decisions or participatory results are discussed in detail. The analysis is based on participatory observations of different kind of meetings, 10 in total, were decisions about the design and implementation of the dialogue process were made. Participant observations were also conducted in several of the dialogue process activities when implemented. Research material also included two semi-structured formal interviews with the planners coordinating the GPP dialogue process as well as numerous informal conversations with other planners of the GPP and consultants involved in the design and implementation of the process. The material also includes substantial document studies of policy papers, meeting minutes, reports and various forms of correspondence between GPP planners and other actors involved in the design and implementation of the GPP dialogue process and its different activities. By combining these different methods, we expand Forester’s (Citation2013, Citation2017) focus on planner’s oral accounts, and aimed at obtaining a richer picture of what planners actually did.

Case study – the Gottsunda Programme Plan

Since the mid-2000s, Swedish cities have experienced rapid urban growth due to accelerated urbanization and migration. Accordingly, national and local efforts have sought to ‘speed up’ urban development and address the urgent demands for new housing. Uppsala municipality is one such urban area where the population is expected to grow by 60% (approximately 135,000 new inhabitants) by 2050. This rapid growth demonstrates the need for fast decisions indicative of swift planning, as called for by the Chair of the Municipal Council in the introduction to the 2016 Comprehensive Plan:

Uppsala is an attractive municipality, and the population is growing rapidly. Therefore, we need to build at a high pace.

Pressing socioeconomic challenges have also added pressure for swift planning in Gottsunda. Housing around 15,000 inhabitants, Gottsunda has a disproportionate percentage of low income and immigrant households and has long experienced socioeconomic problems like unemployment, low levels of education, segregation and vandalism. In 2015, Gottsunda became one of the 20 neighbourhoods nationwide to be included in the police report of Sweden’s ‘Most Vulnerable Areas’. Such categorization directed urgent national and local state intervention to the area and placed pressure on the municipality to improve conditions for residents.

To address both the urgent demand for new housing and the pressing socioeconomic problems, the Municipal Council of Uppsala approved the development of what is known as the Programme Plan for the Gottsunda area in 2015. Following guidelines from the Swedish planning law, the Gottsunda Programme Plan (GPP) was to establish the overall vision for the physical development of the area and the parameters for future detail plans regarding housing, public space and infrastructure projects. As part of the GPP, the Municipal Council mandated the planning of up to 5000 new housing units, responding to the pressure for building new housing fast. The mandate also instructed a social sustainability focus to the plan, implying a holistic approach combining physical and social strategies based on residents’ needs and priorities (Uppsala Municipality Citation2015).

Despite the pressure to approve the GPP swiftly, the Municipal Council also called for a more participatory planning process, requesting involvement and collaboration with residents local organizations, property owners and developers, and municipal departments (Uppsala Municipality Citation2015). However, there were no concrete recommendations for how to implement such a participatory process. This mandate implied going beyond the consultation period mandated by national planning law which only requires municipalities to consult stakeholders or ‘legitimate concerned’ actors on a planning proposal (Metzger, Soneryd, and Linke Citation2017). This type of consultation is far from the inclusive and deliberative (slow planning) processes advocated for in Swedish planning policy and communicative planning theory. Most consultations lack broad involvement of stakeholders and do not provide room for deliberation of issues or solutions beyond those being proposed (Tahvilzadeh Citation2015).

While the GPP would require a consultation period before its final approval, planners sought to carry out a citizen dialogueFootnote1 for allowing more participation and deliberation throughout the planning process. Furthermore, to support these efforts the planners enrolled in a capacity-building network focusing on participatory decision-making coordinated by the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SALAR), an organization representing and supporting local and regional administrations nationwide. Despite the magnitude and complexity of the project, planners were given just over a year to carry out the dialogue process and be ready with all the documentation of the plan before the December 2016 deadline to move on to the next phase of approving the GPP: the consultation period. This did not give the planners much time to work with this project, considering that smaller and less complex plans take in average between one and two years (SALAR Citation2016) and do not include the same intentions for broad participation as the GPP.

Process design: swift and slow planning in the GPP citizen dialogue

The process design of the GPP citizen dialogue unravelled in three different stages. In the first stage, planners attempted to design a process to advance the ideals of slow planning beyond the consultation period mandated by law, whilst also managing the pressure to reach swift decisions. The second stage shows how GPP planners revised their process design based on their involvement in the SALAR capacity-building network. The third stage focuses on the final design choices concerning the implementation of key activities as the deadline for the completion of the citizen dialogue process approached.

First design of the GPP citizen dialogue: planners’ push to advance slow planning

GPP planners’ first proposal for the process design was based on the one hand, on the democratic values and views of participation held by planners, and, on the other, on their estimation of what was in their capacity to do within the given mandate and the deadline established before the start of the consultation period. Despite GPP planners’ self-expressed lack of experience with designing and managing citizen dialogues, they were keen to carry out an inclusive participatory process that went beyond the legally mandated consultation. Their design wanted to address the limitations of consultation, referred by one of the planners as processes where ‘only certain groups participate’ and that ‘can be used to make people feel like they are able to influence decisions when they are not’. Hence, another GPP planner expressed the ‘need of measures to increase democracy or how people can influence their life’s surroundings’.

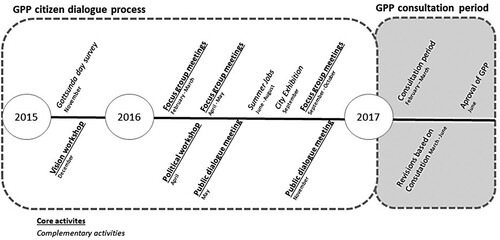

The first design of the citizen dialogue process focused on three core participatory activities that would take place before the consultation period: focus group meetings, workshops, and public dialogue meetings (see ). In addition to the core activities, the planners also carried out a handful of complementary activities to gather and disseminate information, such as resident surveys and outdoor exhibits of plans in progress. As these activities were periphery to the dialogue process, they are outside the scope of this paper.

Figure 1. Activities and timeline of initial GPP process design (adapted from Uppsala Municipality Citation2019b).

The focus group meetings emphasized the inclusion of underrepresented social groups, including young and elderly residents and those with an immigrant background. One planner explained this emphasis by suggesting that these are the groups ‘that have less of a say in society’ as well as ‘the ones that are most difficult to reach and most difficult to get to be excited about participating in such a project [referring to the GPP]’. In the workshops the planners aimed to address the Municipal Council mandate on involving actors invested in the area’s development through two sessions; one with representatives from public and private organizations, including developers, operating in the area (vision workshop) and another with politicians and high-level civil servants (politician’s meeting). Finally, in the public dialogue meetings, the planners would provide room for the general public to be informed and consulted about the progress of the GPP.

In the initial process design, planners conceived the three core activities as interrelated. The focus group meetings and the workshops would serve to gather insights about the neighbourhood and act as a base for the development of the GPP. Focus group meetings were nonetheless conceived as central in the first process design; it was the setting where planners intended to test and discuss their ideas for the GPP, with the outcomes of the focus group discussions influencing the design and content of the public dialogue meetings. Hence, focus group meetings were scheduled in the initial process design before every public dialogue meeting (see ). The prominence of the focus group meetings was one manner in which the planners attempted to respond to the pressure for slow planning; making the process more inclusive and broadening the range of stakeholders by reaching out to underrepresented social groups and providing them opportunities to engage in more direct dialogue.

By the start of 2016, the vision workshop had been conducted with the participation of 30 representatives from public and private organizations operating in the area. Focus was on collecting ideas to guide the physical transformation, including identifying strengths and weaknesses of the area as well as discussing what a socially sustainable Gottsunda would be like (Uppsala Municipality Citation2019b). Although the workshop mainly gathered ideas and information that would be used by the planners in the development of the GPP, it shows another attempt to respond to the pressure for slow planning; particularly as expressed in the Municipal Council’s mandate to have a social sustainability focus and involve actors invested in the area’s development.

Following this activity, the GPP planners joined the SALAR capacity-building network for developing inclusive and deliberative forms of decision-making. SALAR is among the most important organizations engaged in the development of participatory policies and practices in Sweden. GPP planners thought of their involvement in the SALAR network as an opportunity to receive support in the design and implementation of their citizen dialogue.

SALAR’s input to the design of the GPP citizen dialogue: the pressure for more slow planning

The SALAR capacity-building network had the aim of helping municipalities incorporate more participatory processes into decision-making, advocating for the inclusion of comprehensive deliberative processes such as citizen dialogues. The SALAR support revolved around their model for citizen dialogue (SALAR Citation2011) and highlighted three main components for process design: Gathering perspectives, focusing on ‘hot topics’, and facilitating deliberative workshops (). The input of the SALAR experts was shaped by this framework in the feedback they gave the GPP planners during different capacity-building workshops and individual advisory meetings.

Table 1. SALAR’s main components for process design.

The GPP planners first consulted the SALAR experts prior to the first round of focus group meetings with underrepresented social groups. Planners presented the focus groups as an activity to gather opinions concerning positive and negative places in Gottsunda, providing input for developing the vision for the area’s physical transformation. However, during the consultation with the SALAR experts, the GPP planners expressed uncertainty about how to facilitate the focus groups. They also had doubts on the intended key role of the focus group meetings in the overall process design.

The experts gave feedback based on the model for citizen dialogues. For example, one questioned planners’ focus on gathering information about physical aspects of Gottsunda. The experts suggested that rather, the process should open up the discussion to all issues of interest. Considering the socioeconomic situation of many residents in Gottsunda, the experts were keen to see a process that allowed participants to identify and engage with complex issues or hot topics beyond the area’s physical transformation. Similarly, another expert noted that the focus groups seemed to be ‘standalone activities’ compared to the continuous deliberative working-group-based process suggested in the SALAR model. In this manner, the SALAR experts placed increasing pressure for what we have labelled slow planning.

GPP planners welcomed the input of the experts. However, they also expressed concerns about inviting resident input on complex socioeconomic issues as the SALAR experts suggest. As one of them noted: ‘it can be difficult to make this work in the municipal operations, especially if the issues [referring to potential hot topics] do not “fit” into the specific responsibilities of the planning department’. The latter implied technical-driven and physical planning-oriented practices. They also worried that addressing these diverse and potentially controversial social issues would require more time than planned. Beyond the deadline, planners were keen to act swiftly and reach tangible actions that could solve the urgent problems of the area. During a process design meeting, one planner described this urgency as a ‘time-problematic’ where planners needed ‘to have the possibility and force to be able to respond and “do something” [about the urgent issues in the area] in a short time frame’. This quote illustrates the way that the pressure for swift planning was also held in planers’ own intentions to reach decisions and solve problems quickly.

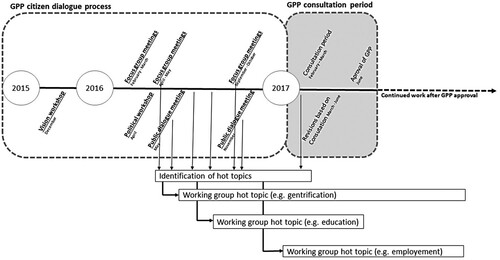

Planners revised the GPP process design, trying to respond to these concerns and to the input from the SALAR experts. The revision emphasized the need to gather perspectives for identifying hot topics focusing mainly on socioeconomic issues (). The identification of hot topics was meant to happen in all future activities of the GPP process generating a more open form of discussion where all actors were able to introduce their own topics of interest. These topics would then be open to discussion through deliberative workshops that would complement the focus on the physical development of the area and continue after the GPP was approved.

Figure 2. Revised process design after SALAR input (adapted from Uppsala Municipality Citation2019b)

Before implementing the revised process design, GPP planners thought it was important to get the approval of their superiors and other municipal departments. They presented the revised process design at the planned politician’s meeting which included politicians and high-level civil servants at different municipal departments. As a strategy to forward their intentions of creating open deliberation around socioeconomic topics, GPP planners invited the SALAR experts to present their model for citizen dialogue and conduct a facilitated session to identify hot topics with the workshop participants.

Following this intervention, GPP planners received widespread support for implementation of the SALAR-based revision of the process design. However, the planners were still concerned about opening up the dialogue process to resident-identified hot topics because they predicted that many of these, e.g. low quality education, unemployment, segregation and gentrification risks, would be outside of the responsibilities of the Planning Department and would not be possible to address within the time-frame of the GPP. In a succeeding process design meeting, one of the GPP planners thus questioned if ‘they had sufficient knowledge and time to arrange and facilitate’ the parallel hot topic working groups. Despite the approval of superiors, it was still unclear how, and even if, the hot topics working group discussions would happen within the short time-frame of the GPP process.

The deadline is close: from ideals to a pragmatic and compromising balancing act

After getting approval for the SALAR-influenced revision of the process design, GPP planners started to plan for the first round of focus group meetings. Planners decided to maintain their focus on the physical development of Gottsunda and the gathering of information about positive and negative places. However, following SALAR’s ideas, GPP planners gave instructions to the facilitators of the focus group meetings to ‘carefully listen for key issues or “hot topics” that could emerge’ in the discussion. The intention, however, was not for these hot topics to be discussed in detail in the meetings due to fears of opening the process up to issues that required solutions beyond the physical transformation.

The first round of focus group meetings with underrepresented groups was carried out in May 2016. Four focus group meetings were conducted with small children and their parents, teenagers, elderly residents, and an ethnic association. The compiled results of the focus groups show that discussions were kept to identifying places that participants’ considered as important to them or that they wanted to be improved with very few references to socioeconomic problems (Uppsala Municipality Citation2019b, 25–29). This indicates that despite an interest in opening up to more socially related issues, the conversations in the meetings themselves still returned to the physical-oriented focus that was criticized by the SALAR experts.

Furthermore, although these focus group meetings had a central role in the initial GPP process design, and were planned before each public dialogue meeting, ultimately only the initial round was conducted. This occurred despite recognition amongst the planners that this first round had not been sufficient to involve all the most difficult to reach groups. The GPP planners mentioned two main reasons for dropping the focus groups from the process design. First, the GPP planner who was driving the idea of the focus groups left the department and no one else felt that they had the capacity or time to implement focus groups. Secondly, there had been a political decision to increase the number of housing units from 5000 to 7000. This implied a revision of most of the planning work conducted so far, acting as a major push for swift planning as there was only time left in the remaining process to implement the two already announced public dialogue meetings.

GPP planners still intended to design the public dialogue meetings to be more deliberative and to go beyond a focus on physical planning, by incorporating hot topic discussions, as suggested by the SALAR experts. The planners saw the hot topic discussions as a way to address the social sustainability focus mandated by the Municipal Council. Accordingly, the planners arranged two advisory meetings with the SALAR experts before each of the public dialogue meetings to receive input on their design ideas. These meetings surrounded similar tensions and ended in similar results: the conclusion that more open and in depth facilitated discussions could not be planned in the process time-frame. The draft design for the public dialogue meetings included two main components: a plenary presentation of the work-in-progress of the GPP and an exhibition with thematic stands (four around the physical development and one for identifying hot topics). The idea was that participants could travel freely between the stands and, if they wished, have one-on-one conversations with civil servants responsible for each theme. However, the SALAR experts’ feedback suggested a more deliberative process could be achieved by moving away from the one-on-one character of the exhibition-based design. Experts also wanted the socioeconomic questions and hot topics to be more central to the meetings. Hence, they suggested adding to the design of the meeting periodical facilitated discussions on these topics with diverse participants.

However, the planners felt it was too difficult to incorporate the facilitated discussions. Between the first consultation with the SALAR experts and the following open dialogue meeting, there were only three weeks to implement their suggestions. According to the planners, there was not enough time to enrol civil servants from outside of the planning department with expertise in the social questions that the hot topics would address and who would be best suited to participate in such a discussion. During the advisory meeting, the planners also stressed the need to have a design that ‘they could control’ with topics ‘that were within their responsibility’. In this case, the pressure for swift planning took the concrete form of limitations in time as well as expertise and responsibilities beyond the physical aspects of the plan which discouraged planners from enacting more open and deliberative forms of dialogue at these meetings. Following the first public dialogue meeting which was carried out in line with planners’ original exhibition-based design, the second public dialogue meeting was meant to provide discussions among residents, politicians and civil servants working with more social and economic issues. However, in this instance similar issues of time and prioritization of physical aspects arose, leading again to an exhibition-based process design where social issues were only discussed through one–one conversations between residents and the invited politicians and civil servants.

In a meeting with the SALAR experts, the planners reflected on how the double pressure for swift and slow planning had come to a head in this final stage, as follows:

If one wants to be harsh, we could say that we are only doing this open dialogue meeting because we have said [to the public] that we are. We are also in this collaboration with SALAR and need to put focus on it [participation and dialogue]. That is a harsh way to put things, but when there is so much to do, this is how one thinks.

As this quote indicates, when faced with time pressure planners’ intentions of creating a more open and deliberative process was reduced and shifted towards only delivering what had been promised. Similarly during this discussion, planners expressed that the time pressure had led to compromises in the overall process design and that the priority was to attain what was required in the Swedish Planning law, in terms of consultation around physical aspects of plans, and meeting the deadline dictated by the Municipal Council. This led to sacrifices when it came to slow planning initiatives including the Municipal Council’s mandate for the GPP to have a focus on social sustainability and attempts to incorporate the SALAR ideas of hot topics and deliberative activities. According to the planners, social sustainability questions were mainly to be tied to physical aspects of the plan like mix-income housing or lively public spaces; while broader social sustainability issues in relation to discrimination, safety or potential gentrification would be addressed in an appendix to the GPP. The implementation of the hot topic working groups was to be postponed after the approval of the GPP, so decisions about the content of the appendix would not be discussed with the public. The appendix would rather be based on information about social issues and hot topics collected throughout the GPP process, and particularly in the vision workshop. In line with the revised process design, the appendix was to serve as a base for the hot topic working group discussions that would continue after the approval of the GPP. The second dialogue meeting was the last activity planned for the GPP participatory process. Planners met the deadline that was set for their process and despite not being able to include all the SALAR suggestions in their process design they felt that the process went well and were proud of what was done.

Concluding discussion

The case study provides insights into how deliberative planners are affected by and navigate the demands for swift and slow planning in their everyday practice; particularly, when making choices regarding the design and implementation of participatory processes. As discussed below, these insights are a critical pragmatic (Forester Citation2013, Citation2017) development of other Nordic studies focusing on the tensions between discourses and legislation pushing for more participatory and deliberative planning processes, on the one hand, and faster and more efficient decision-making, on the other.

The case study’s focus on process design showed that the tensions identified by Nordic studies at the level of discourse or legislation are clearly present in and affect deliberative planners’ choices on who gets to participate in planning, how they participate and for what purpose. The case showed that at this level of planning practice these pressures co-exist and are dynamic; they manifest themselves or become activated in different ways and at different stages of process design. Pressures for both swift and slow were evident at the outset of the GPP citizen dialogue through the Municipal Council’s mandate to address urgent housing and socioeconomic problems and to increase participation in decision-making. The dual pressures were also apparent in the initial intentions of the GPP planners and their ambition to simultaneously ‘increase democracy’ but also achieve swift outcomes that could solve the urgent problems of the area. Increased pressure for slow planning was seen when new and influential actors, the SALAR experts, were enrolled and pushed for more deliberation and openness to issues beyond physical transformation. Such a push for slow planning was nonetheless soon counterbalanced by the need to keep to established deadlines, meet new requirements in the number of housing units and fulfil the technical and physical-oriented focus required by the Swedish planning law.

The dual pressures for swift and slow planning are often associated with discourses more or less aligned with communicative planning theory, and neoliberalism or new public management (Falleth and Saglie Citation2011; Sager Citation2009). Our case study shows different ways in which such discourses playout in process design, in terms of what was expected with regard to participation and deliberation or faster and more efficient decision-making. For example, the call for more participation of the Municipal Council mandate did not imply the same levels of involvement and openness to discuss all issues as the model for citizen dialogue encouraged by the SALAR experts, or even the participatory ideas and ambitions of the GPP planners themselves. This follows Tahvilzadeh’s (Citation2015) and Niitamo’s (Citation2021) observations that there are different notions of what is meant by participation even within the same municipality or planning project.

Similarly, pressures for swift and efficient processes can result in political attempts to change legislation or limit planning process in a way that reduces participation (as described by Grange Citation2017). However, the case shows that even when there is an intention to advance participation, pressures for swift planning can lead to ‘pragmatic exclusion’ with regard to issues that can be discussed, how deliberation takes place or which outcomes are produced (Connelly and Richardson Citation2004). In our case, pragmatic exclusion was seen in the way that process design choices were used to keep the participatory processes within controlled boundaries so that decisions could be made quickly within expected deadlines. Examples of this were GPP planners’ hesitance to open up the citizen dialogue to issues beyond the physical transformation of the area or their choice to design participatory activities in a way that deliberation could be easy to manage (e.g. through exhibition stands and one-on-one conversations). This shows process design as an intrinsic power-laden activity, and highlights the well-known critique of viewing deliberative planners as neutral facilitators, instead of actors who inevitably exercise power (Flyvbjerg and Richardson Citation2002; Westin Citation2022).

Such pragmatic exclusion can also be related to the fact that planning practices in Uppsala, as in many other cities, are more geared towards the ‘building discourse’ identified by Falleth and Saglie (Citation2011). These scholars link this discourse to the economic-driven pressures for efficiency, which, as in our case, result in decision-making procedures with emphasis on time limits and meeting legal requirements. Such legal requirements also tend to favour swift decision-making processes since Swedish planning law only mandates limited consultation on the technical aspects of a project, while broad inclusion, deliberation and openness to issues beyond physical planning are merely a policy recommendation (see also Tahvilzadeh Citation2015; Mäntysalo, Saglie, and Cars Citation2011).

Overall, these findings show that even in projects where the double pressure for swift and slow planning is evident, there is a prevalence of swift expert-based decision-making over participation and deliberation. However, our focus on process design showed how this prevalence mainly occurred when the process was reaching its deadline. Here planners had to forgo some of their intentions to make the process more inclusive, including the key role planned for the focus group meetings or their intention to create more opportunities for deliberation around hot topics as suggested in the revised process design.

The fact that there were process design choices and revisions favouring more inclusion and deliberation shows that the prevalence of swift planning did not occur without planners attempting to counterbalance it. Beyond these design choices and revisions, planners’ efforts to make the process more participatory also included enrolling participatory experts in the process design and seeking support from superiors to make the process more deliberative and open to socioeconomic topics. These counterbalancing efforts show that deliberative planners, such as the ones of the GPP, are not making process design choices that favour pressures to make planning more efficient over pressures for more participation or vice-versa. Rather they are performing a balancing act in which they are trying to address both pressures in the best way they can.

These findings provide a different take on previous academic discussions that tend to frame the dual pressures for swift processes and deliberation as an either-or tension, with planners having to follow one or the other. In Nordic planning research, this framing often results in a one-sided push back against efforts to speed up planning processes (e.g. Niitamo Citation2021; Sager Citation2009). Such either-or framing can also be found in the Habermasian strand of communicative planning theory, where the benefits of participation are described as only achievable through processes that keep close to the ideals of collaborative rationality (e.g. Innes and Booher Citation2016). We support the push back towards attempts to subjugate participation on behalf of efficiency. We also appreciate the normative guidance that communicative planning theory continues to provide for advancing deliberative forms of planning. However, we wonder if these approaches are too one-sided and if instead Nordic planning studies and, more generally, the deliberative turn, should be more aligned with the balancing act of the GPP planners and their attempts to respond to the dual pressures without necessarily favouring one over the other.

From our study, we argue that this balancing act requires acceptance of the necessity to make planning more efficient and capable to swiftly address urgent sustainability challenges, albeit in a democratic way. This echoes Mäntysalo, Saglie, and Cars (Citation2011) who see the tensions created by the pressures for participation and deliberation, and for faster more efficient forms of decision-making as intrinsic to planning. Hence, they claim the need to see the motives behind the pressures as valid and legitimate. Our study did not show that GPP planners were openly acknowledging and creating a process for discussing the double pressure in an agonistic manner, as Mäntysalo, Saglie, and Cars (Citation2011) recommend. However, their efforts to respond to both pressures through their process design suggest that planners saw these as legitimate and worth addressing in the best way they could.

From this, we argue that accepting the legitimacy of the demands for swift and slow planning is crucial in view of the pressing problems of areas like Gottsunda, but also considering the sudden challenges that may arise from climate change, or massive migration as experienced in Europe in the last decade. By this, we do not imply a return to the expert-driven planning processes that led to the deliberative turn. We still believe that there should be time for deliberation even in times of urgency. From our study, we nevertheless see the need to reimagine the deliberative turn in planning as a ‘balancing act’ between equally important demands for participation and deliberation, and for faster and more efficient planning.

Our study provides some inspiration on how such balancing act could look. Our findings show that attempts to balance the double pressure for swift and slow planning are more like walking a tight rope rather than reaching a perfect equilibrium on a balancing scale. The case showed planners undertaking such a tight rope walk across different process design stages with the pressure for swift planning on one side and the pressure for slow on the other. As planners take steps forward, they sway from side to side, from swift to slow and vice-versa. They shift their weight to one side or the other, trying to counteract the forces to keep upright without necessarily aiming for a perfect balance. They were not putting more weight on the side of participation as suggested by Sager (Citation2009) or in line with the Habermasian stream of communicative planning (e.g. Innes and Booher Citation2016). Neither were they fearlessly resisting the neoliberal push for more efficient planning as proposed by Grange’s (Citation2017). GPP planners were rather trying to find strategies such as involving experts, pursuing support from superiors and constantly assessing and revising their design choices for addressing, but not necessarily solving the tension, as suggested by Mäntysalo, Saglie, and Cars (Citation2011), albeit without having open meta-communicative reflections or debates. The latter is something that deliberative planners could strive for as part of their balancing act.

Another example of addressing the either-or tension was to conceive the balancing act along several interrelated planning processes in a given area instead of limiting it to one distinct process. In this sense the prioritization of one of the pressures in one process can be compensated in another; as suggested by Parkinson’s and Mansbridge’s (Citation2012) deliberative systems and their view that no single episode of deliberation, however ideally constituted, can achieve deliberative capacity sufficient to legitimate most of the decisions and policies that governments adopt. This was seen in the revision of the initial process design and the decision to continue work with hot topics even after the approval of the GPP. In this example, deliberative workshops focusing on hot topics such as security, well-being, and the prevention of gentrification were ultimately removed from the GPP process to meet the deadline, but relocated to future planning activities (see Uppsala Municipality Citation2019a; Uppsala Municipality Citation2019b, 77–88).

GPP planners’ balancing act shows how many deliberative planners handle the tensions inherent in the realpolitik of planning. Our ethnographic approach and methodological focus on ‘what planners do’ (following Forester Citation2013, Citation2017) left aside many other factors of the double pressure that could have affected GPP planners’ ways of handling them, such as the positions and actions of politicians, developers or residents towards participation, or differences between the more macro neoliberal and deliberative discourses described in Nordic planning research and how they operate in Uppsala’s and Gottsunda’s local context. We nonetheless see our focus on the critical (in terms of decisive but also not taken-for-granted) design choices that planners make when pursuing deliberative ideals, albeit within what is realistic, as important to forward Forester’s critical pragmatic approach, in part as response to the critiques of the deliberative turn, with its ‘practice bias’ (Citation2017) and its call to spend ‘less time presuming impossibility and more time exploring actual possibility’ (Citation2013, 7). With regard to balancing the double pressure for swift and slow planning, ‘actual possibility’ seems to be less in line with the one-sided push of the Habermasian stream of communicative planning theory or of the critics of the neoliberal emphasis on efficiency. Instead, reimagining the deliberative turn as a balancing act is more aligned with Mäntysalo et al.’s (Citation2011, Citation2015) agonistic approach to planning where the contradicting demands of the double pressure are acknowledged as legitimate and addressed without necessary solving them or creating a perfect equilibrium.

Developing the deliberative turn as a balancing act, requires fewer focus on promoting or questioning the normative ideals of communicative planning theory, which as mentioned earlier is still at the fore in planning discussions in Nordic countries and internationally. Instead, it encourages the pragmatic and practice-near approach of scholars addressing similar either-or tensions currently experienced by deliberative planners in their everyday practices concerning, for example, power, conflicts, consensus or neutrality (e.g. Westin et al. Citation2021, Moore Citation2012; Connelly and Richardson Citation2004). We hope that planning scholars and practitioners who are engaged in, or see the need for, these kinds of developments find our paper, with its focus on process design, as a useful contribution in such endeavour.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Citizen dialogue is a direct translation of the Swedish concept ‘medborgardialog’ that incorporates open dialogues with residents in planning processes. This process, however, is also open to non-citizen residents and stakeholders. We want to highlight this point as it removes any contradiction with the idea that this process sought to include under represented social groups who may or may not be citizens.

References

- Abrahamsson, H. 2012. “Cities as Nodes for Global Governance or Battlefields for Social Conflicts? The Role of Dialogue in Social Sustainability.” In IFHP 56th World Congress: Inclusive Cities in a Global World Gothenburg.

- Baker, M., J. Coaffee, and G. Sherriff. 2007. “Achieving Successful Participation in the New UK Spatial Planning System.” Planning Practice & Research 22: 79–93. doi:10.1080/02697450601173371.

- Boverket. 2021. Medborgardialog [Online]. Accessed 10 December 2021. https://www.boverket.se/sv/PBL-kunskapsbanken/teman/medborgardialog/.

- Brand, R., and F. Gaffikin. 2007. “Collaborative Planning in an Uncollaborative World.” Planning Theory 6: 282–313. doi:10.1177/1473095207082036.

- Connelly, S., and T. Richardson. 2004. “Exclusion: The Necessary Difference Between Ideal and Practical Consensus.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 47: 3–17. doi:10.1080/0964056042000189772.

- Falleth, E., G. Hanssen, and I. Saglie. 2010. “Challenges to Democracy in Market-oriented Urban Planning in Norway.” European Planning Studies 18: 737–753. doi:10.1080/09654311003607729.

- Falleth, E., and I.-L. Saglie. 2011. “Democracy or Efficiency: Contradictory National Guidelines in Urban Planning in Norway.” Urban Research & Practice 4: 58–71. doi:10.1080/17535069.2011.550541.

- Fiskaa, H. 2005. “Past and Future for Public Participation in Norwegian Physical Planning.” European Planning Studies 13: 157–174. doi:10.1080/0965431042000312451.

- Flyvbjerg, B., and T. Richardson. 2002. “Planning and Foucault: In Search of the Dark Side of Planning Theory.” In Planning Futures: New Directions for Planning Theory, edited by P. Allmendinger and M. Tewdwr-Jones, 44–62. London: Routledge.

- Forester, J. 2013. “On the Theory and Practice of Critical Pragmatism: Deliberative Practice and Creative Negotiations.” Planning Theory 12: 5–22. doi:10.1177/1473095212448750.

- Forester, J. 2017. On the Evolution of a Critical Pragmatism. Encounters in Planning Thought, 16 Autobiographical Essays from Key Thinkers in Spatial Planning. New York: Routledge.

- Grange, K. 2017. “Planners – A Silenced Profession? The Politicisation of Planning and the Need for Fearless Speech.” Planning Theory 16: 275–295. doi:10.1177/1473095215626465.

- Healey, P. 2003. “Collaborative Planning in Perspective.” Planning Theory 2: 101–123. doi:10.1177/14730952030022002.

- Healey, P. 2005. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies. Gordonsville: Palgrave.

- Innes, J. 2004. “Consensus Building: Clarifications for the Critics.” Planning Theory 3: 5–20. doi:10.1177/1473095204042315.

- Innes, J., and D. Booher. 2015. “A Turning Point for Planning Theory? Overcoming Dividing Discourses.” Planning Theory 14: 195–213. doi:10.1177/1473095213519356.

- Innes, J., and D. Booher. 2016. “Collaborative Rationality as a Strategy for Working with Wicked Problems.” Landscape and Urban Planning 154: 8–10. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.03.016.

- Kühn, M. 2020. “Agonistic Planning Theory Revisited: The Planner’s Role in Dealing with Conflict.” Planning Theory 20: 143–156. doi:10.1177/1473095220953201.

- Mattila, H. 2020. “Habermas Revisited: Resurrecting the Contested Roots of Communicative Planning Theory.” Progress in Planning 141: 1–25.

- Mäntysalo, R., K. Jarenko, K. Nilsson, and I.-L. Saglie. 2015. “Legitimacy of Informal Strategic Urban Planning: Observations from Finland, Sweden and Norway.” European Planning Studies 23: 349–366. doi:10.1080/09654313.2013.861808.

- Mäntysalo, R., and I.-L. Saglie. 2010. “Private Influence Preceding Public Involvement: Strategies for Legitimizing Preliminary Partnership Arrangements in Urban Housing Planning in Norway and Finland.” Planning Theory & Practice 11: 317–338. doi:10.1080/14649357.2010.500123.

- Mäntysalo, R., I.-L. Saglie, and G. Cars. 2011. “Between Input Legitimacy and Output Efficiency: Defensive Routines and Agonistic Reflectivity in Nordic Land-Use Planning.” European Planning Studies 19: 2109–2126. doi:10.1080/09654313.2011.632906.

- Mellanplatsprojektet. 2013. Framtiden är redan här: hur invånare kan bli medskapare i stadens utveckling [Online]. Accessed December 2017. http://www.mellanplats.se/.

- Metzger, J., I.-M. Eriksson, K. Grange, M. Håkansson, and K. Nilsson. 2016. “Riskabelt när alla ropar på snabbt byggande.” Svenska Dagbladet, April 23. Accessed December 10, 2020. https://www.svd.se/a/RxGna/riskabelt-nar-alla-ropar-pa-snabbt-byggande.

- Metzger, J., L. Soneryd, and S. Linke. 2017. “The Legitimization of Concern: A Flexible Framework for Investigating the Enactment of Stakeholders in Environmental Planning and Governance Processes.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49: 2517–2535. doi:10.1177/0308518X17727284.

- Moore, A. 2012. “Following from the Front: Theorizing Deliberative Facilitation.” Critical Policy Studies 6: 146–162. doi:10.1080/19460171.2012.689735.

- Niitamo, A. 2021. “Planning in No One’s Backyard: Municipal Planners’ Discourses of Participation in Brownfield Projects in Helsinki, Amsterdam and Copenhagen.” European Planning Studies 29: 844–861. doi:10.1080/09654313.2020.1792842.

- Parkinson, J., and J. Mansbridge. 2012. Deliberative Systems: Deliberative Democracy at the Large Scale. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Puustinen, S., R. Mäntysalo, J. Hytönen, and K. Jarenko. 2017. “The ‘Deliberative Bureaucrat’: Deliberative Democracy and Institutional Trust in the Jurisdiction of the Finnish Planner.” Planning Theory & Practice 18: 71–88. doi:10.1080/14649357.2016.1245437.

- Sager, T. 2009. “Planners’ Role: Torn Between Dialogical Ideals and Neo-Liberal Realities.” European Planning Studies 17: 65–84. doi:10.1080/09654310802513948.

- Salar. 2011. Medborgardialog som del i styrprocessen. Stockholm: SALAR. Swedish Association for Local Authorities and regions.

- Salar. 2016. Planläggning och tidsåtsgång 2016. SALAR, Swedish Association for Local Authorities and Regions.

- Salar. 2019. Medborgardialog i styrning: för ett stärkt demokratiskt samhälle. SALAR, Swedish Association for Local Authorities and Regions.

- Stenberg, J., and L. Fryk. 2012. “Urban Empowerment Through Community Outreach in Teaching and Design.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 46: 3284–3289. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.052.

- Tahvilzadeh, N. 2015. “Understanding Participatory Governance Arrangements in Urban Politics: Idealist and Cynical Perspectives on the Politics of Citizen Dialogues in Göteborg, Sweden.” Urban Research & Practice 8: 238–254.

- Uppsala Municipality. 2015. Programme Plan for Gottsunda with Focus on Social Sustainability. KSN-2015-0654. Uppsala.

- Uppsala Municipality. 2019a. Citizen Dialogue on Security in Gottsunda [Online]. Accessed 31 January 2022. https://www.uppsala.se/kommun-och-politik/publikationer/dialoger/medborgardialog-om-trygghet-i-gottsunda/.

- Uppsala Municipality. 2019b. Results Citizen Dialogue – Programme plan Gottsunda. Uppsala.

- Westin, M. 2022. “The Framing of Power in Communicative Planning Theory: Analysing the Work of John Forester, Patsy Healey and Judith Innes.” Planning Theory 21 (2): 132–154. doi:10.1177/14730952211043219.

- Westin, M., A. Mutter, C. Calderon, and A. Hellquist. 2021. “‘Let us be led by the Residents’: Swedish Dialogue Experts’ Stories about Power, Justification and Ambivalence.” Nordic Journal of Urban Studies 1: 113–130. doi:10.18261/issn.2703-8866-2021-02-02.