ABSTRACT

Many European planning schools recently celebrated their 50th anniversary: a sign that planning education became a distinct and established discipline in Europe. Simultaneously, political regimes, paradigms, cultures, and economies continue fuelling mixed connotations within the planning sector. Additionally, growing wicked problems in built areas emphasize an even greater need for well-trained planners. These challenges span climate crises, wars, authoritarian regimes, socio-political instability, and constantly changing global geopolitics. The increasingly complex demands on planners are highly pertinent for Young Academics (YA). They require political, regulatory, and technical knowledge to navigate the profession. To support them and represent their voices in planning debates, the YA network (YAN) of AESOP was established in 2003. We, the current Coordination Team, use this paper to voice our take on the question of what planning challenges dominate and what can be done to prepare YAs better for the future. Building on plenty discussions within the YAN, literature, and AESOP’s activities at large, we propose: A challenge compilation for the profession, a list of core capacities, and a framework for future education. This shall aid in enabling YAs and educators today to set the foundation for planning sustainable and people-centered settlements tomorrow.

1. Introduction

After its emergence in the first part of the twentieth century as a discipline, spatial planning has become a solid profession and an established practice. European societies are challenged by the climate crises, conflicts, authoritarian regimes, socio-political instability, constantly changing global geopolitics and economic developments, to just name a few of the wicked spatial problems facing cities and societies. This results in growing and increasingly complex demands on planners. In fact, the ‘concept of “wicked issues”, originally developed in the field of urban planning’ by Rittel and Webber (Citation1973) (Bore and Wright Citation2009, 241). According to Bore and Wright (Citation2009, page), wicked as a term explains the complexity of issues faced in urban planning, whereas each problem ‘is essentially unique and every solution is a one-shot operation which is either better or worse’. As such, ‘wicked problems are ill understood until a solution is found’. This interpretations reflects a transformation in the philosophy of the planning (and design) field from the previously knowledge technical and rational approach to planning that represents the ‘modernist or “Fordist” paradigm’ towards ‘a “postmodern” perspective’ that is non-linear (page); postulating that professional skills are better ‘expressed as the framing of the problem to be addressed, and that wicked problems may be resolved by the time the problem is identified, conjectured and defined’ (Coyne Citation2005; in Bore and Wright Citation2009). Moreover, Coyne (Citation2005) suggests that this understanding reflects the ‘challenge occurring in the late 1960s and early 1970s to the authority of science, presented in Kuhn’s work on scientific revolutions’ (Kuhn Citation1970 cited in Bore and Wright Citation2009). This results in growing and complex demands on planners. Young planners and scholars are especially impacted as they require increasingly complex political, regulatory, and technical and non-technical knowledge to navigate their profession effectively. Additionally, building on the premise that ‘planning is a discipline that distinguishes itself from other academic disciplines because of its focus on the future’ (Nguyen and Sanchez Citation2022), there is a greater need for well-trained and skilled planners due to the continuous increase of wicked spatial problems reflecting complex futures (Innes and Booher Citation2016). According to Bore and Wright (Citation2009, page) ‘[t]he literature on “wicked issues” does not fully recognize the difficulties with reflective practice and that in education which extols reflective practice, is not aware of the “wicked” nature of the problems which confront teachers and schools’. As such they ‘argue for is a fresh understanding of the underlying nature of problems and issues in education so that more appropriate solutions and techniques can be developed or devised for their resolution’. In a similar plea, we argue in this article that the emergence of the Young Academics (YA) network of AESOP originated from the need of young planner address wicked challenges of European planning as they emerge.

To respond to such rising needs and simultaneously grow and represent the next generation within the Association of European Schools of Planning (AESOP), the Young Academics (YA) network was established in 2003 to support YAs by providing an intellectual platform and introducing YAs to the international planning culture and community. The YA team members are elected for a duration of two years to act as the Coordination Team (CT). The YA Team is usually made of six individuals at doctoral or postdoctoral level who come from different sub-fields and countries, including non-European. It works on facilitating events, exchanges, and projects for the YA community to respond to these needs. In this context, we collaborate in this article to share our perspectives and insights on the challenges that face YAs in the current point in time. Hence, we address four main questions in this article:

What critical challenges (will) dominate YAs careers?

What capacities do todays and tomorrows YAs need to respond to these challenges?

What should be done by whom to face current and future challenges?

How YAs position themselves and are they part of the change in our discipline and profession (research and practice)?

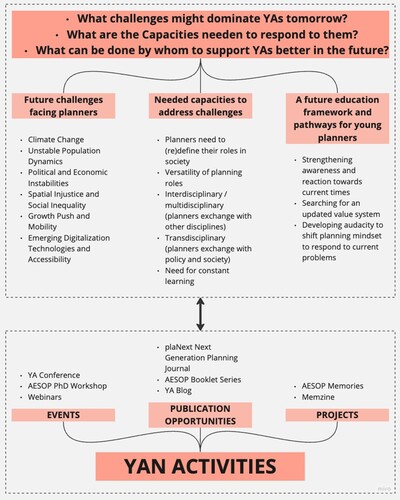

We draw on our own experience as YA CT combined with the countless AESOP events, discussions, roundtables, and PhD workshops that have been taking place since the emergence of the YA Team at AESOP. It is important to note that we do not claim to write on behalf of all YAs but instead attempt to provide a snapshot of current discussion subjects and concerns. Following an outline of the activities of the YAN and its ambition and contribution to facing current challenges, we make three contributions in this paper: First, we compile critical challenges facing future planning generations and discuss the role of YAs in tackling wicked spatial problems. Then, we elaborate on the needed future capacities and knowledge for planning/planners. Finally, we propose a tentative future education framework and situate our own activities therein.

2. The AESOP Young Academics Network

The development and implementation of pathways requires the integrated and targeted collaboration of various stakeholders. Educational institutions must prepare students, professional institutions and firms must develop new capacities of employees as part of continued professional development, and planners themselves, both practitioners and scholars, are in charge to find the most adequate responses to complex challenges. Here, we discuss how the YAN of the AESOP supports young individuals in this process and simultaneously provides opportunities for institutions to better access and exchange with the next generation of planning professionals.

The YAN is foremost providing a platform for young planners to interact with like-minded people from Europe and beyond, institutions, as well as AESOP, while offering opportunities for fostering their academic and professional growth. Active for 20 years, it was one of the forming elements for a generation of planning scholars and practitioners; many of them staying in touch with the network until today. YAN evolved from an initiative of several passionate individuals to a network with more than 2,000 members in 2023, with regularly elected members of the Coordination Team and its own charter framing its activities and its relationship with AESOP. In its humble beginnings, YAN organized its first Conference in 2007 and its activities since then expanded to annual conferences with more than 200 applications, its own publications, seminars, active involvement with main AESOP events and other endeavours aiming to expand its reach to regional and supra-regional structures and provide a broader range of opportunities for its members.

The scope of YAN’s activities stands on three pillars. Firstly, organizing and co-hosting events for young scholars, such as YA Conference, AESOP PhD Workshops, or webinars where participants get actively involved, obtain feedback for their work and expand their professional and personal network. Secondly, offering multiple publication opportunities such as the plaNext – Next Generation Planning journal, Booklet series or YAN Blog with over 250 contributions, or contributing as editor or reviewer to gain experience related to academic publishing. Lastly, several projects have been launched and some transformed into regular AESOP events. The latest project is AESOP Memories where we collect the memories of AESOP’s founding members in an intergenerational way and present them in an accessible and inspiring way, for the community and wider audiences. Preparing young scholars for the new challenges and improving their skills comes mainly from direct experience or indirect knowledge obtained from like-minded individuals. In this broad range of activities, YAN strives to support its members in their training needs. YAN’s mission is to foster capacity development of members by providing training and opportunities for honing their technical skills, networking, and cultural skills, as well as building experiences with working across disciplines and cultures. We believe that scholars need to be at ease in international environments with everything it entails, from language skills to acknowledging and embracing the diversity of cultures, ways of thinking and working among various professional disciplines.

During the last years, COVID-19 paused some activities but was motivated to test innovative formats and adjust event organization. For young scholars in particular, online exchanges bring additional benefits of lifting participation barriers linked to travel cost and participation fees. Furthermore, it was never easier to get in touch with senior academics from around the globe. This issue of inclusivity shall be further strengthened by continuing and increasingly providing a range of free events (online events and YAN Conference being free of charge) as well as various bursaries and travel grants to apply for.

3. Future challenges facing planners

The planning profession as a scientific discipline is constantly transformed by ever-changing conditions, interdisciplinarity, multidisciplinary, transdisciplinary, and context dependency just to name a few. Spatial planning is an interdisciplinary field that draws on a wide range of disciplines, including but not limited to architecture, geography, sociology, economics, and political science, to understand and address the complex issues facing cities and rural communities. Additionally, many emerging fields such as geo-environmental engineering, spatial science, environmental engineering link planning with other well-established areas, such as urban ecology, urban sociology, urban economics, urban management, urban policy.

Planning as accommodating different views and perspectives has a paramount role in tackling them (Innes and Booher Citation2016). In this role, spatial planners and young academics need to direct their perspective towards key challenges (). Here is a glimpse of key challenges in a much more clear classified manner that is necessary in order to help YAs to better position themselves in responding to these challenges. Both existing and future challenges that young planners face are classified based on their origins in this section. First group of challenges stem from contemporary global challenges that have comparatively immediate impact on real-life such as Climate Change, Unstable Population Dynamics, Political and Economic Instabilities that have impact on every country and context. The second group contains namely contextual boundaries exemplified as social, economic and ethical expectations from planning, varying political and legislative systems. This group involves topics such as Spatial Injustice and Social Inequality, Growth Push and Mobility. Last but not least, third group of challenges stem from maintaining/sustaining planning research facing external limitations as funding, accessibility to tools as in Emerging Digitalization Technologies and Accessibility.

Table 1. A glimpse of key challenges that need to be tackled by urban planners.

The interpretation of planning as a social science and a normative practice varies across different countries and regions. Its role in society is context-dependent, particularly in areas where planning has historically been used as a tool for political powers to promote their views and beliefs, leading to mixed opinions and uncertainty. In the European context, the interpretation of planning as a social science can vary between countries and regions. The historical use of planning as a tool for political powers to promote their views and beliefs can also be observed in some European areas, leading to mixed opinions and uncertainty about the role of planning in society. Understanding these regional differences in the interpretation of planning and its role in society is essential to develop effective and contextually appropriate planning strategies. By acknowledging these differences, planners can gain a better understanding of the local context and build planning approaches tailored to the region's specific needs, leading to more successful and sustainable planning outcomes.

Regardless of geographical context, there are many critical challenges in spatial planning, most notably contemporary global challenges, contextual boundaries and sustainability of planning research from global to local perspectives listed in . Some of them and wicked spatial problems remain the same or are in a different disguise, and there is rich evidence about various approaches of dealing with them across the world.

In terms of climate change related global challenges, for instance, Rees (Citation2018) addresses the inadequacies of urban and regional planning in terms of underdeveloped biophysical groundwork, misguided neoliberal formulation of economic planning, lack of sense of common good and prevailed individual and corporate benefits, rational-comprehensive model of policy planning against the challenges of Anthropocene era. Planning for this era requires ‘to re-conceive cities – or better, urban regions – as self-renewing, regenerative human ecosystems’ (Rees Citation2018, 57–58).

In terms of population dynamics differ one place to another, planners need to find ways both to accommodate growth and shrinkage in sustainable and equitable ways. Population is an important aspect and component of planning. Related literature about population shrinkage is unclear to some extent. While population growth has been accepted as leading to urban growth organically, decrease in population does not cause urban shrinkage immediately (Sousa and Pinho Citation2015). Gurrutxaga (Citation2020) recaptures that the concept of shrinkage is not only a rural phenomenon, but also a concept that concerns urban areas. His research emphasizes the importance of addressing population decline in urban and rural areas as additional criteria for scrutinizing socio-economic dynamics of planning. Complementary research shows also that more places are exposed to long-term demographic changes than anticipated and planning cultures could be better equipped to respond to the needs by having more realistic and sustainable focus from growth towards shrinkage (Pallagst et al. Citation2021).

In terms of political and economic challenges, where do the planning practice and the planner stand in the complex neoliberal framework? Kunzmann (Citation2016) discusses the role of neoliberal politic and economic environment on devitalizing the planning in society. Also, Eraydın (Citation2021) highlights the practice-related discontent among planning scholars by disentangling its reasons. There are firstly neoliberalism-induced democratic deficits, expanded inequalities, and exclusion of particular groups from decision-making. Then, there is the inability of existing planning systems and decision-makers unwillingness to respond to public needs, which results in disappointment (Eraydın Citation2021).

The endless push to grow contributes also to the previous discussion about political and economic instabilities. Savini, Ferreira, and von Schönfeld (Citation2022) discuss the difficulty of unlinking economic growth from planning and welfare for planners, decision making bodies and communities in terms of post-growth planning perspective. According to Savini, Ferreira, and von Schönfeld (Citation2022), growth dependency in planning is a major challenge. Even if growth induced wealth is redistributed relatively in a few areas to some extent, this does not necessarily mean that there are no social and ecological damages composed from growth. In line with previous challenges, many places are facing growth pressure, with negative consequences affecting planning and planners.

To tackle wicked socio-spatial challenges such as climate change and spatial inequalities, planners must adopt better planning policies. Better planning practices will be promoted, according to Houston et al. (Citation2018, 203), by reviving projects for decolonizing urban space, initializing environmental justice discourse by constructing the knowledge together with ‘the messy contexts of multispecies entanglement, and becoming world urban realities, to inform critical conversations.’ The way Houston et al. (Citation2018) piece together, planning should be reconsidered in the Anthropocene era by extending its engagement beyond human-centric towards more deepened ecological and environmentalist.

Planning is context-dependent, particularly in geographies where planning was used for decades as a tool for political powers to introduce their views and convictions. Some mixed connotations and dubiousness still remain (Najjar Citation2019). Differences in approaches to spatial planning between regions, countries or political regimes create encounters at some points like Global North and South approaches to planning (Rees Citation2018). As Mukhopadhyay et al. (Citation2021, 7) state, ‘ … knowledge produced from the South was not globally circulated due to multiple constraints’, such as rooted publishing and referencing systems, unbalanced resources, and prevailing traditional northern planning theory in education. With the emerging digitalization technologies, different methods and tools are integrated in planning research and application. What could be the challenges of such methods and tools? Hersperger et al. (Citation2022) scrutinize planning practice side of digitalization of land use planning in terms of efficiency, transparency and innovation. Insightful concerns are raised for the future of planning about the creation of guides to process data, risk of standardization of planning, unpredictable changes in power dynamics of stakeholders, unwanted shift towards ‘technocratic planning practice’ (2551) and such. In addition to these, YAs, who are trying to keep up with the changing conditions, face difficulties while trying to protect the values related to the essence of the profession. Most planners also have difficulties in accessing new technologies in the first place.

In this context, young planners are increasingly expected to deal with and tackle these contemporary challenges. Therefore, in the next section we share needed capacities to address these challenges.

4. Needed capacities to address challenges

Building on the premise that ‘the future of humankind was, in large measure, determined by the quality of education received’ (Hall Citation1904, p. xv), in this section we discuss what skills and capacities need to be addressed by planning education institutions in support of young planners to face the aforementioned challenges and wicked spatial problems discussed above.

4.1. Planners need to (re)define their roles in society

Planning as a discipline is understood differently across countries and regions due to the role that planning is expected to fulfil and the varying realization thereof across time and space. Today, the role of planner is much more complex as various actors are becoming part of planning processes and planning processes become more democratic and inclusive, and the scope of planning problems is increasing. Expectations of the public and other stakeholders are much higher, more people have their say in the decisions, social media and other technological developments put planners and their work into the spotlight. Planner’s role is not easily defined as it is changing in various stages of the planning processes. For instance, Marcuse (Citation2011) reveals that modern planning is shaped around three approaches: a technical one, a social reform one, and a social justice one, while these can be intertwined and emerge at different or similar times. In the technocratic planning approaches, the planner is seen as a professional or an expert with special training and expertise, as well as an intermediate member who could use a toolbox with specific technical training, as the society perceives and expects. In a highly complex world reflecting the broader shift towards acknowledging interdisciplinarity and cooperation among professions as vital for dealing with complex spatial problems, such view and expectations cause a mismatch between the expectations and realities. In these environments, planning needs to put an emphasis on proving itself as a set of tools, by acting on spatial control, that improve the quality of life of people and be able to help society overcome the challenges lying ahead.

4.2. Versatility of planning roles

The role of a planner in contemporary society varies, too, and planners need to fulfil multiple roles in various projects and stages of a project. No longer a possessor of all the necessary knowledge, planning profession has more facilitating role (planner as an enabler or moderator) (Brenner Citation2014; Marcuse Citation2011; Watson Citation2022), advocacy role (planner as an advocate for a specific group of individuals), political role (mediating among political views or advocating for a selected group) and many others (Biesbroek, Swart, and Van der Knaap Citation2009; Davoudi, Crawford, and Mehmood Citation2009; Hamrouni Citation2013). Building on this, contemporary planners can play the role of mediators not only among different stakeholders but also across different disciplinary boundaries, further necessitating the next generation planners to have knowledge of other disciplines besides planning instead of dealing with planning as a branch of architecture or engineering. Moreover, with ever increasing complexity, more rapid pace of changes in the society, developments in technology, global interconnectedness, the range of roles that planners fulfil is ever expanding. Not keeping up with the latest technological advancements or not being up-to-date with recent trends are making it more difficult to be a good planner or not to miss out.

4.3. Interdisciplinarity/multidisciplinary (planners exchange with other disciplines)

One of the persistent challenges that the field of spatial planning and spatial planners are expected to deal with are wicked spatial problems (Innes and Booher Citation2016; see also Wilson Citation2010), such as those presented in . With the continuous increase of these challenges across scales, there is a greater need for well-trained and skilled planners. This requires a variety of skill sets, and that’s where interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary engagement, linking the practice of planning with other disciplines, comes in (Galan and Kotze Citation2022; Salaj et al. Citation2010), making planning more ‘applicable’ (Lawrence Citation2010). Multidisciplinarity is about providing multiple perspectives on an issue (Chen et al. Citation2019; see also Pinson Citation2004). Interdisciplinarity means the integration of knowledge and methods from diverse diciplines through real synthesis (see Jensenius Citation2012; Stember Citation1991; Abernethy et al. Citation2005). As such ‘the interdisciplinary approach is uniquely different from a multidisciplinary approach, which is the teaching of topics from more than one discipline in parallel to the other, nor is it a crossdisciplinary approach, where one discipline is crossed with the subject matter of another’ (Jones Citation2010, 1; see also Salaj et al. Citation2010). According to Chen et al. (Citation2019, 922), ‘[i]deally, an educational program in the urban field thus consists of multidisciplinary as well as interdisciplinary components’ (see also Lawrence Citation2010). In response to the need for interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary planning practices, planning education programs and planning studies at graduate level, interdisciplinary shall provide an opportunity for students to explore programs are important. In this way, meeting with different approaches, encounters with experts from different disciplines (see among others Galan and Kotze Citation2022; Taylor et al. Citation2021). Broadening the interdisciplinary perspectives of young planners will permit them to gain interdisciplinary knowledge and methodologies as well as getting an opportunity to learn the skills associated with other disciplines (see Wilson Citation2010). The knowledge and skills that young planners can gain from such interdisciplinary education include widening students’ understanding, learning tolerance for dealing with peers from different background, enhancing their communication abilities, leadership and collaboration skills, as well as allowing students to achieve higher order, advanced, and integrated thinking skills and increasing the achievement between (and across) disciplines (see Boyer and Bishop Citation2004; Jones Citation2010; Staples Citation2005). Hence, students learn to develop the ability to innovate and solve real-world problems (Staples Citation2005; Youngblood Citation2007) as well as ‘develop lifelong learning skills’ (Duerr Citation2008, 177). As Jones (Citation2010, 78) puts it ‘[i]nterdisciplinary techniques are not only important for a student to learn any one single discipline or solve problem in a synthesized manner, but it also enriches a student’s lifelong learning habits, academic skills, and personal growth’. In fact, the need for interdisciplinary education is not specific to the field of planning, according to Bear and Skorton Citation2019 – ‘[t]he world needs students with interdisciplinary education’.

4.4. Transdisciplinary (planners exchange with policy and society)

Compared to inter- (collaboration) and multidisciplinarity (exchange), transdisciplinary calls for transcending disciplinary borders, or even the eradication thereof. Transdisciplinary provides the ways in which diverse and multistakeholders and their knowledge can foster successful planning practice (Lawrence Citation2010; Patorniti, Stevens, and Salmon Citation2018). According to del Cerro Santamaría (Citation2020, 19) transdisciplinarity ‘is a mode of inquiry, practice, and learning that places ethics, aesthetics, and creativity inside, not outside, of disciplinary and professional work’. Patorniti, Stevens, and Salmon (Citation2018, 292) shares several examples of urban projects ‘that have arguably been more successful because of a transdisciplinary approach’ such as Polk (Citation2014), Smith and Jenkins (Citation2015), Stauffacher et al. (Citation2008), Tötzer, Sedlacek, and Knoflacher (Citation2011), and Walter and Scholz (Citation2007). Patorniti, Stevens, and Salmon (Citation2018, 294) demonstrate that ‘transdisciplinary views are required to assemble the wide-ranging perceptions of a complex urban system”. In a similar plea, Després, Vachon, and Fortin (Citation2010, 33) argue that planning (and architecture) ‘are predisposed disciplines and professions for implementing transdisciplinarity’. They illustrate that this can be achieved by ‘issuing back and forth between practice-based research and evidence-based design through collaborative processes’ (33). In fact, some scholars (e.g. Wamsler Citation2017 and many others) link transdisciplinarity with (knowledge) co-production. Moreover, many scholars suggest that transdisciplinarity is about considering the theoretical and practical knowledge across disciplines (see for example: Gibbons et al. Citation1994; Pohl and Hadorn Citation2007) as well as considering the exchanges between science-policy (see for example: Patel et al. Citation2020). Similar to the arguments above that interdisciplinarity and multidisciplinary in planning practices and education makes it more applicable, applying transdisciplinary is also perceived to make the field more applicable and relevant to meeting current city and societal challenges (Bore and Wright Citation2009; Lawrence Citation2010), moreover it makes it more relevant for policy (see among another Bore and Wright Citation2009). Also in a similar plea to interdisciplinarity and multidisciplinary, planning education shall equip its students with the needed transdisciplinary skills such as recognizing multiple and plural perspectives (of actors and disciplines), understanding the processes of understanding decision making, gaining the ability to reflect on and affect policy implications as well as understanding the complexity of urban challenges (based on Bore and Wright Citation2009).

4.4. Need for constant learning

New knowledge is produced today more quickly than ever before. No one is expected to memorize all of this, particularly considering that all information is accessible today with several clicks on your mobile device. Shockingly, we are facing a different challenge – how to navigate and critically approach any new information, what requires a different type of knowledge that seems to be often overlooked. The available knowledge (theoretical views, case studies, practical examples etc.) is virtually unlimited and young planners need to hone the skills of using it and translating it into action while considering the context dependencies. International exchanges and collaborations can help to achieve these goals as young planners are immersed into challenging environments and are expected to learn from others and at the same time to contribute with their knowledge. At the same time, new trends continue to emerge constantly (e.g. 15-minute-city, garden city, smart city) (Lopez et al. Citation2021). Planners are sometimes too quick to adopt or invite new concepts (or names thereof), rather following trends than considering the actual changes behind. Thus, in addition to continuous learning, planners further need to be trained to distinguish between the mass of information and balance between old, foundational and continuously relevant knowledge, and innovative and powerful new findings, without confounding the two too often. Lastly, an inherent part of learning is critical reflection of ones actions in terms of individual action as well as collective practice of planning. Planners are often perceived as experts while ruminating the effects of their work on society is not always considered and deserves attention in the planning education.

5. A future education framework and pathways for young planners

After discussing a wide set of the challenges that young planners are facing, as well as the needed capacities to correspond, the important question to answer is ‘How to get there?’. We provide our perspective by bridging the two previous sections to a future education framework and pathways which could be suitable for young planners to position themselves. This section critically summarizes the previous state of planning education, its current position and proposes some steps to be taken for the future. In this section there is a number of topics that will support young planners in their future steps and spark a discussion about their positions for the future of planning.

We pose the following questions in order to navigate the discussion in this section:

What are the future steps in terms of opportunities, new approaches and practices for planning?

How can future education framework be shaped in terms of building capacity and knowledge to cope with the challenges?

How can young planners become more ambitious in achieving their goals?

Much research in the field scrutinizes existing planning education in terms of knowledge, methods and application. Planning education usually equips planning students with generalized knowledge and skills on the multidimensional topics in the field (Taşan-Kok and Oranje Citation2018). This does not necessarily make planning education less efficient, yet it does provide insufficient competence to some extent. Complexities make it hard to obtain and sustain knowledge since knowledge is constantly evolving. In response thereto, there are calls for new pedagogies across disciplines (Lamb and Vodicka Citation2021). According to Frank (Citation2022), planning should become more collaborative and communicative while supporting public participation and interdisciplinarity.

For the future of planning, although there are different discussions about the need for updated and thought through planning education in different contexts and in response to the future challenges (Frank Citation2022; Frank and Silver Citation2018); the role of young practitioners and scholars in planning and the ways they position themselves after their education in different geographies have not been discussed properly. We aim to contribute to this issue with our position.

Planners in a transdisciplinary milieu cannot learn and practice everything in detail. However, creating an open transdisciplinary and collaborative system that allows planners to experiment within their capacities and deepen their knowledge in areas where they have greater talent and interest should be a priority for planning education. To achieve this, it is essential to strengthen ties with public, private, and non-governmental bodies and rethink institutional schemes so that inter-institutional communication and interdisciplinary perspectives become stronger in the future. At the same time, the contextual relationship of a focus area to the greater planning field must be ensured. Frank (Citation2022) proposes three dimensions to achieve such system:

Strengthening ties with public, private, and non-governmental bodies and rethinking institutional schemes so that inter-institutional communication and interdisciplinary perspectives become stronger in the future.

Updating the analytical framework by emphasizing the inclusion of all actors in the planning education process.

Fostering a pedagogical approach that strengthens an exchange with diverse real-life planning projects.

Planning undergraduate education should be in constant change and transformation according to the current conditions. In order to establish a stronger relationship between planning undergraduate education and practice, arrangements should be made to allow group students close to graduation to work in the field. There are some recent approaches/practices supporting this idea by encouraging final year undergraduate students to do internships in an institution that makes an agreement with the university in advance for 6 months period, such as planning departments in the state or private planning offices. This allows undergrads to achieve both experience and connections in the field and get a solid idea of what the planner is actually doing in the real-world. In addition, they get the chance to experience the problems in practice while they are still studying in order to discover the points that do not match in the planning understanding of the country, they are in with what is taught in theory, and to be a bridge between theory and practice. In this context, planners who want to continue in the academic world can include real practice planning problems in theory as they have already experienced them.

Moreover, spatial planning has an authentic identity and is a discipline with its own dimensions such as ‘practical context, spatial norms, knowledge and action’ (Salet Citation2014, 293). Salet states (cf. Frank Citation2022) that the consistent interrelation between contextual perceptions of spatial focus, knowledge, and action – supported by new ways of social contact – makes spatial planning authentic. Essentially, there are challenges in ensuring that this authenticity is acknowledged and recognized by the students. Although each planning issue needs to be critically addressed within its context and certain rules, how much this can be achieved with the existing education system is another research topic.

We propose three pathways of how a young planner can prepare for what is to come:

Strengthening awareness and reaction towards current times,

Searching for an updated value system,

Developing audacity to shift planning mindset to respond to current problems.

There will be more challenges in increasing manner that expected to encounter in the future since the planning discipline is intertwined with life. YAs should demand specialization areas from the setting in which they work/live/exist, such realities as disaster management, climate crisis, spatial justice, forced migration that urgently need to be addressed in formal curricula and informal ways of learning. We must seek an updated value system that is more equitable as well as increased awareness of what is actually happening around us. The aspiration that YAs are a part of change and that they are positioned wholeheartedly for this is of great importance in shaping the future planning mindset.

7. Discussion and conclusion

We are standing on the verge of – or are already in – a crisis greater than we have ever faced on a global level: the climate crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic puts additional pressure on human settlements, especially from economical to social perspectives. This highlights that it gets harder to sustain the lives we had before or even requires significant downscaling; at least for the majority of the global population. Environmental threats on humankind require a rapid change in the uncontested value system of planning to incorporate the limits of our planetary boundaries. Safeguarding and managing natural resources while working towards more people-centered places constitutes the key task of current and future planners and scholars (Frank and Silver Citation2018).

In this paper, we set out to find answers to the question of what challenges might dominate the future and what can be done to prepare YAs better. We addressed this through the lens of the Young Academics Network of AESOP and introduced six systemic challenges and six overarching capacities for next generation planning practitioners and scholars (). We attempted to translate this into a future education framework that emphasizes transdisciplinarity, the contextualized balance between generalist and specialist knowledge, and the link between practice and theory, while emphasizing the need for constant re-evaluation and emancipation of the role of planners.

While only constituting one puzzle piece of the overall needed action, AESOP activities continue to assist addressing some recurring issues, including developing capacities such as transdisciplinarity or international knowledge exchange, or tackling systemic challenges such climate change or social injustice. While the scale and significance today are unprecedented, problems also challenged planners in the past. To just name a few, past health crises, (cold) wars, or the 70s oil crisis had a significant impact on our practices.

The significance of present and future challenges requires a multipronged approach, calling upon planning schools, associations, professional establishments, planning offices, and the planner itself, young or experienced. In the context of the AESOP YAN, we continue with the well-established programs while exploring what some of the most adequate support initiatives could be. Some of the current activities span (1) the stronger regionalization to better incorporate geographical and socio-cultural differences, (2) the increasing prioritization and enabling of transdisciplinary across activities, and (3) the strengthening of global links to support the increasing number of members from other continents who study or work in Europe, or members who participating in AESOP activities and left to other countries. Further, the globalization of knowledge but simultaneously emancipation of regional planning theories, such as in Global South planning, as well as a necessary skill to un- and relearn for planners from the North who work in other cultural, societal or political contexts, is already today a crucial skill and is expected to become even more so. With this, we target to contribute positively to the next 50 years of the planning discipline to support the planning practitioners and scholars of tomorrow and help getting them as prepared as possible for the wicked spatial problems that await them.

Acknowledgements

This position paper has been written by the current Coordination Team but summarizes the work and exchanges of many. We express our gratitude to all preceding CT members, volunteers, partners, supporting institutions, and AESOP as well as its member schools for the continuous support and care for young academics in the planning field.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Abernethy, B., Baker, J. and Côté, J. 2005. “Transfer of Pattern Recall Skills May Contribute to the Development of Sport Expertise.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 19, 705–718. doi:10.1002/acp.1102

- Bear, A., and D. Skorton. 2019. “The World Needs Students with Interdisciplinary Education.” Issues in Science and Technology 35 (2): 60–62.

- Biesbroek, G., R. Swart, and W. Van der Knaap. 2009. “The Mitigation–Adaptation Dichotomy and the Role of Spatial Planning.” Habitat International 33 (3): 230–237. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2008.10.001

- Bore, A., and N. Wright. 2009. “The Wicked and Complex in Education: Developing a Transdisciplinary Perspective for Policy Formulation, Implementation and Professional Practice.” Journal of Education for Teaching 35 (3): 241–256. doi:10.1080/02607470903091286

- Boyer, S., and B. Bishop. 2004. “Young Adolescent Voices: Students’ Perceptions of Interdisciplinary Teaming.” RMLE 1. doi:10.1080/19404476.2004.11658176

- Brenner, N. 2012. “What is Critical Urban Theory?” In Cities for People, not for Profit, edited by Neil Brenner, Peter Marcuse, and Margit Mayer, 11–23. Routledge.

- Chen, Y., T. Daamen, E. Heurkens, and W. Verheul. 2019. “Interdisciplinary and Experiential Learning in Urban Development Management Education.” International Journal of Technology and Design Education 30: 919–936. doi:10.1007/s10798-019-09541-5

- Coyne, R. 2005. “Wicked Problems Revisited.” Design Studies 26: 5–17. doi:10.1016/j.destud.2004.06.005

- Davoudi, S., J. Crawford, and A. Mehmood, eds. 2009. Planning for Climate Change: Strategies for Mitigation and Adaptation for Spatial Planners. London: Earthscan.

- del Cerro Santamaría, G. 2020. “Complexity and Transdisciplinarity: The Case of Iconic Urban Megaprojects.” Transdisciplinary Journal of Engineering & Science 11. doi:10.22545/2020/0131

- Després, C., G. Vachon, and A. Fortin. 2011. “Implementing Transdisciplinarity: Architecture and Urban Planning at Work.” Transdisciplinary Knowledge Production in Architecture and Urbanism: Towards Hybrid Modes of Inquiry, 33–49. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-0104-5_3

- Duerr, Laura. 2008. “Interdisciplinary Instruction, Educational Horizons.” http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/3e/0c/3a.pdf

- Eraydın, A. 2021. “Searching for Alternatives: What is a Way Out of the Impasse in Planning and Planning Practice?” Megaron 16: 4. doi:10.14744/MEGARON.2021.15807

- Frank, A. 2022. “Learning to Learn Collaboratively.” Planning Practice and Research 37 (4): 484–488. doi:10.1080/02697459.2022.2076795.

- Frank, A., and C. Silver. 2018. Urban Planning Education Beginnings, Global Movement and Future Prospects. Cham: Springer.

- Galan, J., and D. Kotze. 2022. “Pedagogy of Planning Studios for Multidisciplinary, Research-Oriented.” Personalized, and Intensive Learning. Journal of Planning Education and Research. doi:10.1177/0739456X221082502.

- Gibbons, M., C. Limoges, H. Nowonty, S. Shwartzman, P. Scott, and M. Trow. 1994. The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies. Stockholm: Sage.

- Gurrutxaga, M. 2020. “Incorporating the Life-Course Approach Into Shrinking Cities Assessment: The Uneven Geographies of Urban Population Decline.” European Planning Studies 28 (4): 732–748. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1634007.

- Hall, G. S. 1904. “Adolescence: Its psychology and its relation to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion & education.” New York: D. Appleton & Co.

- Hamrouni, I. 2013. The Shifting Role of Planners with and Through Development Aid Corporations in MENA Region Context. Cairo: IUSD.

- Hersperger, A., C. Thurnheer-Wittenwiler, S. Tobias, S. Folvig, and C. Fertner. 2022. “Digitalization in Land-use Planning: Effects of Digital Plan Data on Efficiency, Transparency and Innovation.” European Planning Studies 30 (12): 2537–2553. doi:10.1080/09654313.2021.2016640

- Houston, D., J. Hillier, D. MacCallum, W. Steele, and J. Byrne. 2018. “Make Kin, not Cities! Multispecies Entanglements and ‘Becoming-World’ in Planning Theory.” Planning Theory 17 (2): 190–212. doi:10.1177/1473095216688042.

- Innes, J., and D. Booher. 2016. “Collaborative Rationality as a Strategy for Working with Wicked Problems.” Landscape and Urban Planning 154: 8–10. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.03.016

- Jensenius, A. 2012. “Disciplinarities: Intra, Cross, Multi, Inter, Trans.” Message posted to http://www.arj.no/2012/03/12/disciplinarities-2/

- Jones, C. 2010. “Interdisciplinary Approach-Advantages, Disadvantages, and the Future Benefits of Interdisciplinary Studies.” Essai 7 (1): 26.

- Kuhn, T. 1970. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kunzmann, K. 2016. “Crisis and Urban Planning?” A Commentary. European Planning Studies 24 (7): 1313–1318. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1168787.

- Lamb, T., and G. Vodicka. 2021. “Education for 21st Century Urban and Spatial Planning: Critical Postmodern Pedagogies.” Teaching Urban and Regional Planning, 20–38. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Lawrence, R. 2010. “Deciphering Interdisciplinary and Transdisciplinary Contributions.” Transdisciplinary Journal of Engineering & Science 1. doi:10.22545/2010/0003

- Lopez, C., N. Le Bot, O. Soulard, P. Detavernier, A. Heil Selimanovski, F. Tedeschi, Ph. Bihouix, and A. Papay. 2021. La Ville Low-Tech. Paris: ADEME, Institut Paris Region, AREP.

- Marcuse, P. 2011. “The Three Historic Currents of City Planning.” In The New Blackwell Companion to the City, edited by Gary Bridge, Sophie Watson, 643–655. Hoboken: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Mukhopadhyay, C., C. Belingardi, G. Papparaldo, and M. Hendawy, eds. 2021. Special Issue: Planning Practices and Theories from the Global South. Conversations in Planning Theory and Practice Booklet Project. Dortmund: Association of European School of Planning, Young Academic Network.

- Najjar, R. 2019. “Planning, Power, and Politics (3P): Critical Review of the Hidden Role of Spatial Planning in Conflict Areas.” In Land Use: Assessing the Past, Envisioning the Future, edited by Luis Loures, 217–239. London: IntechOpen.

- Nguyen, M., and T. Sanchez. “Alternative Planning Futures: Planning the Next Century.” Accessed December 10, 2022. https://journals.sagepub.com/pb-assets/cmscontent/JPL/JPLCFPPlanningintheNextCentury-1662047505867.pdf

- Pallagst, K., R. Fleschurz, S. Nothof, and T. Uemura. 2021. “Shrinking Cities: Implications for Planning Cultures?” Urban Studies 58 (1): 164–181. doi:10.1177/0042098019885549

- Patel, Z., N. Marrengane, W. Smit, and P. Anderson, 2020. “Knowledge Co-Production in Sub-Saharan African Cities: Building Capacity for the Urban Age.” In Sustainability Challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa II. Science for Sustainable Societies, edited by H. T. Andersen, and H. Nolmark, et al., 189–214. Singapore: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-5358-5_8.

- Patorniti, N., N. Stevens, and P. Salmon. 2018. “A Sociotechnical Systems Approach to Understand Complex Urban Systems: A Global Transdisciplinary Perspective.” Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries 28 (6): 281–296. doi:10.1002/hfm.20742

- Pinson, D. 2004. “Urban Planning: An ‘Undisciplined’discipline?” Futures 36 (4): 503–513. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2003.10.008

- Pohl, C., and G. Hadorn. 2007. Principles for Designing Transdisciplinary Research. Munich: Oekom.

- Polk, M. 2014. “Achieving the Promise of Transdisciplinarity: A Critical Exploration of the Relationship Between Transdisciplinary Research and Societal Problem Solving.” Sustainability Science 9 (4): 439–451. doi:10.1007/s11625-014-0247-7

- Rees, W. 2018. ““Planning in the Anthropocene”.” In 2018. The Routledge Handbook of Planning Theory, edited by M. Gunder, A. Madanipour, and V. Watson, 41–52. London: Routledge.

- Rittel, H., and M. Webber. 1973. “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.” Policy Sciences 4: 155–169. doi:10.1007/BF01405730

- Salaj, A., A. Fošner, J. Jurca, I. Karčnik, I. Razpotnik, and L. Žvegla. 2010. “Knowledge, Skills and Competence in Spatial Planning.” Urbani Izziv 21 (1): 61–69. doi:10.5379/urbani-izziv-2010-21-01-006

- Salet, W. 2014. “The Authenticity of Spatial Planning Knowledge.” European Planning Studies 22 (2): 293–305. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.741567.

- Savini, F., A. Ferreira, and K. von Schönfeld, eds. 2022. Post-growth Planning: Cities Beyond the Market Economy. London: Routledge.

- Smith, H., and P. Jenkins. 2015. “Trans-disciplinary Research and Strategic Urban Expansion Planning in a Context of Weak Institutional Capacity: Case Study of Huambo, Angola.” Habitat International 46: 244–251. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2014.10.006.

- Sousa, S., and P. Pinho. 2015. “Planning for Shrinkage: Paradox or Paradigm.” European Planning Studies 23 (1): 12–32. doi:10.1080/09654313.2013.820082.

- Stember, M. 1991. “Advancing the social sciences through the interdisciplinary enterprise.” The Social Sciences Journal 28(1): 1–14. doi:10.1016/0362-3319(91)90040-B

- Staples, Hilary, 2005. “The Integration of Biomimicry as a Solution-Oriented Approach to the Environmental Science Curriculum for High School Students.” http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_01/0000019b/80/1b/c2/3d.pdf.

- Stauffacher, M., T. Flüeler, P. Krütli, and R. Scholz. 2008. “Analytic and Dynamic Approach to Collaboration: A Transdisciplinary Case Study on Sustainable Landscape Development in a Swiss Prealpine Region.” Systemic Practice and Action Research 21 (6): 409–422. doi:10.1007/s11213-008-9107-7

- Taşan-Kok, T., and M. Oranje. 2018. From Student to Urban Planner: Young Practitioners’ Reflections on Contemporary Ethical Challenges. London: Routledge.

- Taylor, J., S. Jokela, M. Laine, J. Rajaniemi, P. Jokinen, L. Häikiö, and A. Lönnqvist. 2021. “Learning and Teaching Interdisciplinary Skills in Sustainable Urban Development—The Case of Tampere University, Finland.” Sustainability 13 (3): 1180. doi:10.3390/su13031180

- Tötzer, T., S. Sedlacek, and M. Knoflacher. 2011. “Designing the Future – A Reflection of a Transdisciplinary Case Study in Austria.” Futures 43 (8): 840–852. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2011.05.026

- Walter, A., and R. Scholz. 2007. “Critical Success Conditions of Collabora- Tive Methods: A Comparative Evaluation of Transport Planning Projects.” Transportation 34 (2): 195–212. doi:10.1007/s11116-006-9000-0

- Wamsler, C. 2017. “Stakeholder Involvement in Strategic Adaptation Planning: Transdisciplinarity and co-Production at Stake?” Environmental Science & Policy 75: 148–157. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2017.03.016

- Watson, V. 2002. “Do we Learn from Planning Practice? The Contribution of the “Practice Movement” to Planning Theory.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 22 (2): 178–187. doi:10.1177/0739456X02238446.

- Wilson, A. 2010. Knowledge Power: Interdisciplinary Education for a Complex World. London: Routledge.

- Youngblood, Dawn. 2007. “Interdisciplinary Studies and the Bridging Disciplines: A Matter of Process.” Journal of Research Practice 3 (2). http://www.eric.ed.gov/ERICWebPortal/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno = EJ800366