ABSTRACT

Due to the minimal role of statutory city-regional planning in Finland, the Finnish state promotes inter-municipal, integrated planning of land-use, housing and transportation in the biggest city regions by a strategic planning instrument and a contractual policy tool called MAL procedure. MAL procedure includes MAL agreements, where the central government agrees to fund transportation infrastructure, while the municipalities in the city-regions commit to certain planning principles. MAL policy has advanced sustainability goals in planning, but it has also been argued to be prone to legitimacy problems as MAL negotiations take place behind the backs of citizens. The article discusses the structure of the MAL policy, assessing the ways in which this structure supports the legitimacy of the policy. It focuses on the interplay of strategic and communicative rationalities in the MAL procedure, starting from the observation that the theorists of strategic planning have focused predominately on communicative rationality as the legitimacy basis of planning. This paper aims to show that from a broader, structural perspective, both rationalities – and the way in which they interact – have a role in maintaining the legitimacy of planning. The article builds on theoretical studies and interviews with actors engaged in the MAL procedure.

Introduction

The role of city-regions as engines of economic growth on regional, national or even mega-regional scale is widely recognized today (e.g. Harrison Citation2007; Scott Citation2001; Scott et al. Citation2001; Ward and Jonas Citation2004). As such, many national governments have actively promoted the growth of major city-regions in their jurisdictions (e.g. Brenner Citation2003). Furthermore, city-regional scale has been argued to be relevant for tackling sustainability issues in urbanization (e.g. Janssen-Jansen and Hutton Citation2011; Ravetz Citation2013; Wheeler Citation2000). Therefore, many national governments intervene in the steering of growth in urban regions today. This is the case also in Finland, which is the contextual locus of this article.

The Finnish administrative system does not formally recognize city-regions. Regions exist in the Finnish administrative system, but their coverage typically extends far beyond functional urban regions, and their powers are weak when compared to local governments and the central state. Local governments have considerable powers, especially in matters of land-use planning. Municipalities in the major city regions in Finland have some legal obligations related to city-regional planning, but they have been generally reluctant to engage in joint plan-making (Mattila and Heinilä Citation2022). Research has shown that municipal planning in Finnish city-regions is affected by competition over investments and taxpayers and that this competition has led to unsustainable and inefficient urban sprawl (e.g. Hytönen et al. Citation2016; Mäntysalo et al. Citation2010).

For these reasons, the central government of Finland has introduced a contractual policy instrument called MAL procedure – ‘M’ referring to land-use (maankäyttö), ‘A’ to housing (asuminen) and ‘L’ to transport (liikenne). The procedure is purported to support city-regional cooperation in planning. This cooperation, in turn, is expected to advance climate-friendly growth, sufficient and affordable housing provision and the use of sustainable modes of transportation in the large Finnish city-regions (Ympäristöministeriö Citationn.d.).

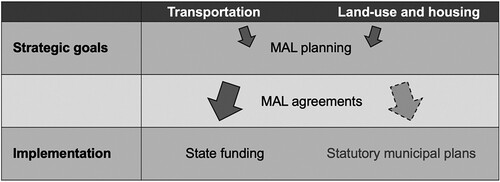

MAL procedure is a strategic planning and policy instrument consisting of two parts. First, it contains MAL planning and MAL plans, which are mainly non-statutory plans for land-use, housing and transportation, drafted collaboratively by the municipalities in the participating urban regions. Second, it entails agreements between the central government and the municipalities in the participating urban regions. These agreements are expected to be based on MAL plans. In the agreements, the central government commits to co-fund transportation infrastructure and other projects in the growing urban regions, and in return, the municipalities commit, most importantly, to plan a certain number of housing units in locations that are accessible by public transportation and supportive of walking and bicycling. This structure makes the MAL procedure, a strategic planning instrument. It differentiates between the choice of strategically important planning goals and the tools for their implementation. Implementation leans, in particular, on the state’s co-funding of transport infrastructure.

MAL procedure has been argued to be an effective instrument for advancing cooperation in city-regional planning and promoting the sustainability and functionality of city-regions (Hemminki and Lönnqvist Citation2022; Tiitu et al. Citation2023; Vatilo, Mattila, and Jalasto Citation2022). Nonetheless, researchers have criticized the procedure for compromising the democratic and participation-oriented qualities of planning. This is because, first, the MAL procedure is a state-led procedure. It can be therefore argued to prioritize state-level interests rather than interests articulated in the context of local democracy (Davoudi, Kallio, and Häkli Citation2021). Furthermore, MAL agreement negotiations involve only selected key actors from different levels and sectors of governance (Bäcklund et al. Citation2018; Vaattovaara et al. Citation2021). In addition, MAL planning is not a statutory form of planning, and it thus does not include mandatory public participation procedures (Bäcklund et al. Citation2018).

In this article, we focus on meta-governance practiced by the Finnish state through MAL policy, asking whether and in which ways the central government makes space for democracy and deliberation in the architecture of the MAL procedure, and where the MAL procedure leans on deal-making that follows the logic of economic incentives, or command-and-control approaches of traditional administration. Furthermore, we ask how these approaches contribute to the legitimacy of MAL policy. The theoretical framework for answering this question is the interplay of two rationalities in strategic planning procedures: strategic rationality and communicative rationality. These forms of rationality have been discussed especially by Habermas (Citation1984), whose works have been an important point of departure for many planning theorists, including theorists of communicative planning (e.g. Forester Citation1989; Citation1993; Healey Citation1992; Citation1996; Citation1997; Sager Citation1994) and strategic spatial planning (e.g. Albrechts Citation2003; Healey Citation1996; Citation1997; Citation2007). Communicative rationality, in particular, has been frequently discussed by planning theorists since it has been argued to be the form of rationality that provides the basis for the legitimacy of public planning or any other form of public governance (Mattila Citation2020). However, strategic rationality, too, can be assumed to have a legitimate role in planning, especially when an issue is strategic planning.

This article is structured as follows. It first examines the Habermasian theory of rationalities, assessing the suitability of the theory for analyzing and developing strategic planning. It introduces a novel way of utilizing the Habermasian framework to assess the qualities of strategic planning at macro-level, focusing on policy structures rather than on individual communicative processes. The paper then briefly introduces the history of the MAL procedure and moves on to examine how the key actors – especially state-level actors – in the MAL procedure perceive the structure of the MAL policy in terms of the spaces that the procedure establishes for strategic and communicative rationalities respectively. Finally, the article concludes with an assessment of whether and how the structure of the MAL procedure may give rise to legitimacy problems.

Strategic and communicative rationalities: a Habermasian approach

In his Theory of Communicative Action (Citation1984; Citation1987), Habermas approaches the concept of rationality by building on two basic intuitions concerning rational behaviour. People are said to behave rationally, on the one hand, when they use knowledge to find means for achieving ends that they want to achieve, and on the other hand, when they use knowledge communicatively, interacting with other people to reach a reasoned agreement (Habermas Citation1984, 8–22). From this point of departure, Habermas develops his differentiation between two forms of rationality, strategic and communicative one and two alternative action-orientations, as well as two mechanisms of action coordination based on the respective rationalities.

Strategic rationality is a representative of success-oriented means-ends rationality. Habermas discusses means-ends rationality first in terms of instrumental rationality and the related instrumental action characterized by ‘informed disposition over, and intelligent adaptation to, conditions of a contingent environment’ (Habermas Citation1984, 10). When the environment of success-oriented action is a social world, Habermas (Citation1984, 285 and passim) calls it strategic action, which builds on strategic rationality, a mode of rationality that manifests itself in such behaviour where we ‘calculate how others will act or can be made to act in ways that either facilitate or hinder the successful pursuit of our personal aims’ (Ingram Citation2019, 432).

Habermas’s contribution to the modern discourse on rationality is the concept of communicative rationality, and the related form of action, communicative action, where ‘the actions of the agents involved are coordinated not through egocentric calculations of success but through acts of reaching understanding’ (Habermas Citation1984, 286). In this case, rational behaviour manifests itself not as attempts to find means to reach pre-set goals but as attempts to achieve understanding through discourse, including for instance attempts to form or revise common goal settings by providing reasons and justifications, as well as challenging argumentatively justifications provided by other actors (cf. Habermas Citation1984, 10–15).

In Habermas’s theory, communicative rationality is a more fundamental form of rationality than success-oriented rationalities. Communicative rationality is inherent in our language use, and ‘carries with it connotations based ultimately on the central experience of the unconstrained, unifying, consensus-bringing force of argumentative speech’ (Habermas Citation1984, 10). Habermas grounds the consensus-bringing force on the idea of ‘validity claims’ that speakers in rational argumentation implicitly or explicitly raise related to truth (what they say is true), authenticity or sincerity (they mean what they say) and normative rightness (what they say is appropriate in the normative context at hand or that the normative context is itself legitimate) (Habermas Citation1984, 15–16, 99–100).

The two rationalities in strategic spatial planning

Communicative rationality is useful for action coordination – including coordination taking place through spatial planning – especially because in the Habermasian theory, not only questions concerning factual validity but also those concerning normative validity have a prospect of rationally motivated agreement. Normative goal setting has been traditionally a key issue for strategic planning which typically builds on the differentiation between the selection of strategic goals and the operational implementation of the goals (e.g. Albrechts Citation2010; Bryson Citation1988; Kaufman and Jacobs Citation1987; Mintzberg Citation1994). As such, it is not surprising that strategic spatial planning literature has emphasized the role of communicative rationality and deliberative decision-making in planning, where efficient implementation of plans can be advanced by communicative processes through which the actors come to share the reasons for the decisions and can be thus expected to be committed to these decisions (e.g. Albrechts Citation2004; Citation2010; Healey Citation1996; Citation1997; Citation2007).

Nonetheless, strategic rationality has been present in the strategic planning literature, too, especially when the selection of means of implementation has been discussed. In addition, strategic planning literature today typically implies that there are some general goals that are typically not questioned when the goal setting is discussed, such as the need for cities, regions and other spatial units to succeed in the global competition between places (Albrechts Citation2004; Albrechts and Balducci Citation2013; Healey Citation2007; Kunzmann Citation2013). Even though such success often requires cooperation between actors in different places and scales, this cooperation is often strategically rational rather than communicatively rational (Granqvist et al. Citation2021). Strategically rational action brings about efficiency in the achievement of goals, and it can be thus associated with the ‘output legitimacy’ of governance processes, whereas communicatively rational action strengthens the ‘input legitimacy’ of these processes (cf. Scharpf Citation1999).

Given the competitive and efficiency-oriented settings of contemporary spatial planning, it is not surprising that several critics have questioned the relevance of communicative rationality for spatial planning in practice. One of the theoretical reasons for this has been that Habermas himself thought communicative action-coordination to be relevant in the action realm of the ‘lifeworld’, ‘the transcendental site where speaker and hearer meet, where they reciprocally raise claims […] settle their disagreements, and arrive at agreements’ (Habermas Citation1987, 126), while giving strategic rationality a central role in the action realm of the ‘system’. With the ‘system’ he referred to the modern systems of economy and administration, where coordination is based on ‘delinguistified’ steering media of money and power (Habermas Citation1987, 154, 171, 184, et passim). As the critics have pointed out, the systems of economy and administration are the primary realm of spatial planning, the fact of which reduces the possibilities of communicatively rational action coordination to emerge in the field of planning (e.g. Hillier Citation2002; Citation2003; Huxley Citation2000; Phelps and Tewdwr-Jones Citation2000).

Habermas, however, never argued that there is no space for communicative rationality in economic or administrative institutions; he rather acknowledged that communicative and strategic interactions are typically intertwined in practice (Habermas Citation1982, 236). Planning theorists such as Forester (e.g. Citation1989; Citation1998) and Sager (Citation2013) have emphasized in their work that in addition to having roles as public officials, planners can be politically active and ethically responsible citizens, and that there is leeway for this role too in the communicative interactions included in their planning work. It makes sense to argue that this holds true especially when at issue is informal, procedurally non-regulated strategic planning, though there is of course no guarantee that planners would make use of the possibility to resort to communicative rationality; they can surely just as well rely on strategic rationality.

It is important to note that Habermas is not suggesting that communicative rationality alone – without systemic steering media of money and power – could guide collective action coordination in complex and pluralist societies. The constant risk of disagreement would make coordination too inefficient (e.g. Habermas Citation1987, 183). However, Habermas (Citation1987, 266–282) also argues that the steering practiced through the systems is legitimate only when the systems are ultimately anchored in the lifewordly, consensus-producing communicative processes. Hence, Habermas is interested in the junctures or ‘hinges’ between the action coordination mechanisms based, on the one hand, on communicative rationality and, on the other hand, on strategic rationality (see Habermas Citation1996, 56).

When analyzing strategic and communicative rationalities in strategic planning – and in MAL procedure in particular – we use the Habermasian ideas concerning the interplay of the two rationalities as a heuristic framework, acknowledging that Habermas’s view of the interplay of the two rationalities is not directly applicable to the context of strategic planning. One of the reasons for this is that Habermas (Citation1996) locates the junctures between rationalities in law or binding regulation, whereas strategic planning in the case of MAL procedure – and also more generally, in the context of the European discourse on strategic planning – is typically understood as non-statutory and legally non-binding planning (Albrechts Citation2004; Citation2010; see also Kunzmann Citation2013). As we will suggest, this may in fact be a weak point in the strategic structure of MAL policy. In our analysis, we lean on such key scholars of strategic planning as Healey (Citation2009) and Albrechts (Citation2010) who have argued that instead of attempting to anchor strategic planning on either of these two rationalities alone, attention needs to be directed to the interplay of rationalities in strategic planning.

MAL policy as a contractual urban policy

Contractual policies for steering the development of growing urban regions are not a new invention. The UK-based contractual policies, such as City Deals promoting growth and infrastructure development, have been discussed intensively in the research literature on strategic urban development during the past decade (e.g. Deas Citation2014; O'Brien and Pike Citation2015; Waite and Morgan Citation2019). City Deals have been criticized for being oriented towards growth at the expense of sustainability (Waite and Morgan Citation2019), for replacing politics and citizen participation by management by the elites (Deas Citation2014) and for appearing as they would shift power to local-level actors, while, in reality, they sustain the centralization of power through the state-led funding mechanisms (Waite and Morgan Citation2019). The notion of ‘deal’ reveals that this governance tradition leans on strategic rationality. Deals rely on the steering media of money, and deals are made based on existing interests rather than on communicatively rational, critical discussions about the pre-selected interests and policy goals. If the critics are right, deal-making in City Deals takes place in the framework of the strategic interests of the state that meta-governs the deal-making procedure and controls its goals, rules and structures (cf. Waite and Morgan Citation2019).

Critical scholars have identified a similar pattern in the Finnish contractual urban policies. It has been argued that in the Finnish contractual policies, the state has created an image of equality- and dialogue-based communicative relation between the state and local or regional level actors, while in reality, the state and its strategic interests dominate the agenda setting and the communicative space (Soininvaara Citation2022; see also Bäcklund, Kanninen, and Hanell Citation2023; Vaattovaara et al. Citation2021). MAL policy, in particular, has been criticized for its prioritization of the state’s economic interests as it promotes the growth of city-regions without properly consulting local democratic decision-making organs or local publics (Bäcklund, Kanninen, and Hanell Citation2023; Davoudi, Kallio, and Häkli Citation2021; see also Bäcklund et al. Citation2018).

Even though this criticism resonates with the international research on contractual urban policies, it differs considerably from the justifications that Nordic governments have given to their contractual policies on land-use, housing and transport during the recent decades. Central governments in Norway, Finland and Sweden have made efforts for more than a decade to design long-term contractual policies to render agreement procedures concerning co-funding of infrastructure more transparent, structured and sustainability oriented (Smas et al. Citation2017). Norway, in particular, is known for its long-term policy in land-use, housing and transport systems development, a policy that is currently implemented through Urban Growth Agreements (Smas et al. Citation2017; Tønnesen et al. Citation2019; Westskog et al. Citation2020). Even though the Norwegian policy, too, has been criticized for prioritizing the state’s strategic interests, the state has responded to this criticism by reshaping contractual policies to make the position of the state and the local partners more equal and by broadening the agenda – based on the dialogue between partners – beyond growth and infrastructure development to ambitious mobility, sustainability and climate goals (Westskog et al. Citation2020; see also Tønnesen et al. Citation2019).

Instead of associating the Finnish MAL policy at the outset with state-dictated growth-first policies that lean on strategic rationality only, we will next investigate whether and at which points in the architecture of the MAL policy the Finnish state-level actors aim to create spaces for communicatively rational interaction between the parties. This investigation is done through interviews with key actors in MAL policy especially at the state level. Before the analysis of the interviews, however, a few words are needed about the development of the MAL procedure in Finland.

The history of MAL policy

Like its Nordic counterparts, the Finnish MAL policy has developed gradually through experiments. Even though some initiatives for developing a systematic approach to contractual practices in land-use, housing and transportation infrastructure were made already in the late 1990s, MAL policy started to form only in the 2000s, when the Government of Finland had largely failed to promote planning cooperation between municipalities by means of legal regulation. The so-called PARAS Act (Act on Restructuring Local Government 169/2007) encouraged municipalities in urban regions to merge, but the number of mergers resulting from the act was fewer than expected (Government of Finland Citation2009). However, due to this act, the municipalities in the large city-regions started to collaboratively draft various types of city-regional plans, plans that are used as background material for MAL agreements today.

The follow-up report on the PARAS project (Government of Finland Citation2009) called for more support for the planning cooperation in big city-regions. Contractual policy on land use, housing and transportation had already been launched in the Helsinki urban region, and the report suggested an extension of the policy to the urban regions of Tampere and Turku. The Parliament eventually decided to include not only these two regions but also the Oulu region in the policy that became known as the MAL procedure.

The Government of Finland made the first MAL agreements for the periods of 2012–2015 with Helsinki and Turku regions, and 2013–2015 with Tampere and Oulu regions. The parties in these agreements – described then as letters of intent – were the municipalities in these city-regions and the Ministry of Transport and Communications, the Ministry of the Environment, Finnish Transport Authority, Centres for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment (state actors at the regional level) and the Housing Finance and Development Centre of Finland (ARA). In the Helsinki region, Helsinki Regional Transport Authority was also a party to the agreement.

Recently, the time span for the MAL agreements was extended from four to twelve years to strengthen the long-term, strategic vision behind the agreements, and to establish a connection between MAL procedure and the new national transport plan, Liikenne 12, which is also drafted for twelve years period. In addition, three new city regions – Jyväskylä, Lahti and Kuopio regions – were introduced to the MAL procedure (Vatilo, Mattila, and Jalasto Citation2022). From the part of the central state, some new organizations have joined the procedure, most importantly, the Ministry of Finance, which has been expected to strengthen the commitment of the state to the economic aspects of the agreement.

Nonetheless, legislative means for the advancement of city-regional planning have not been completely rejected. The Land-use and Building Act (132/1999) of Finland has been under reform for several years at the time of writing this article. One of the goals of this reform was originally to introduce statutory city-regional plans with mandatory public participation for those city-regions that are participating in the MAL procedure (Government of Finland Citation2021). MAL agreements would have remained as an extra-legal support mechanism for city-regional planning. Even though the formalization of city-regional planning was considered to make MAL planning procedures more uniform and transparent and to provide a remedy for the potential democracy deficits of city-regional planning, the establishment of statutory city-regional planning was heavily criticized by local authorities. The formalization of city-regional plans was therefore rejected. Moreover, the whole project of reforming the planning law was put on hold in 2022 due to political disagreements. MAL procedure, however, appears as well institutionalized in the Finnish planning culture despite its lack of legal basis (Hemminki and Lönnqvist Citation2022; Vatilo, Mattila, and Jalasto Citation2022).

Key actors’ views on the rationalities and coordination mechanisms in the MAL procedure

In what follows, we analyze the interviews of 24 key actors in the MAL procedure. The interviews were held as part of an evaluation of the MAL policy commissioned by the Government of Finland in Spring 2022. The evaluation focused especially on the meta-governance level of the MAL procedure and the functioning of the overall architecture of the policy. Therefore, we chose to interview mainly state-level actors, who have been responsible for structuring the procedure and, as such, also responsible for the alleged legitimacy deficits of the MAL procedure. We were interested in hearing how they justified and assessed the structure of the MAL procedure and whether these justifications and assessments included responses to the criticisms concerning the lack of democratic accountability, the ‘structural’ silencing of the local actors’ voices and the potential legitimacy deficits of MAL procedure. The interviewees were asked not to hide their personal views on the issues discussed in the interviews, especially in the case that these views differed from the views that their organizations held.

We interviewed six officials from the Ministry of the Environment, five officials from the Ministry of Transport and Communications, two officials from the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment, one official from the Ministry of Finance, four officials from the Centres of Economic Development, Transport and the Environment, one from the Finnish Transport Infrastructure Agency and one from the Housing Finance and Development Centre of Finland. In addition to these state-level actors, we interviewed two officials working for the Helsinki Regional Transport Authority and two officials working for regional councils, which are in some regions involved in the drafting of city-regional plans. Local-level actors were not included because our aim was to look at the MAL procedure from a macro-level perspective rather than from the grass-roots perspective and because there was research available on local-level actors’ views on the MAL procedure (Bäcklund, Kanninen, and Hanell Citation2023; Hemminki and Lönnqvist Citation2022).

The semi-structured interviews were held in Finnish. Interview excerpts in this article are translated into English by the authors. In the interviews, the themes discussed were, in particular, the effectiveness, legitimacy and democratic qualities of the MAL procedure. We also discussed the quality of cooperation between the actors and the structures that were supposed to facilitate the cooperation. Rationalities, by contrast, were not an explicit theme in the interviews. Before selecting the Habermasian rationalities as our analytical framework, our approach was abductive (Timmermans and Tavory Citation2012). When coding and analyzing the material, we went back and forth between the material and theories/conceptual categories, clarifying the categories used for the coding through an iterative process.

In the interview material, mentions concerning two different steering mechanisms appeared frequently: the dialogue-based (communicative steering), and the incentive-based (money as a steering media). Oftentimes, the interviewees attempted to describe the logic of the MAL procedure in terms of either one of these two steering mechanisms, and they were typically slightly puzzled about the co-existence of the two mechanisms in the process. This fact suggested to us that a conceptualization of this co-existence is needed to increase the actors’ understanding of the process. In addition, regulation-based steering (power as a steering media) came up, even though it does not currently have a position in the MAL procedure.

When making associations between the category of dialogue-based action-coordination mechanisms and the Habermasian communicatively rational action, we acknowledged that Habermasian theory is a normative theory including idealizations that cannot be realized as such. Hence, in our analysis, we were searching for observations concerning prevailing action orientations and aspirations towards each type of rationality.

Views on the overall functioning of the MAL procedure’s architecture

All the interviewees held that MAL policy has strengthened the cooperation and the mutual trust between, first, municipalities in the participating city-regions, secondly, the state-level and local-level actors, and thirdly, sectors of administration at various levels of administration. All interviewees reported, though, that communication in all these relations still calls for further development, especially as regards qualities that can be associated with communicative rationality.

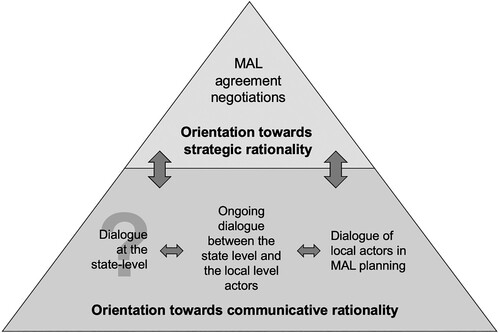

While interviewees recognized that the agreement-related negotiations – the ‘deal-making’ processes – taking place once in every four-year period and forming the most visible part of the MAL procedure were typically saturated with strategic interests, they also highlighted the role of the constantly ongoing longer-term process of communication between the state and municipalities. They held that in this process, the goals and rules of the MAL procedure could be negotiated in an open, inclusive and dialogical manner. The identified features that can be associated with communicative rationality were especially the orientation towards agreement on the points of departure as well as on the normative goals of the process, and the long-term building of trust between the parties:

MAL procedure has been highly effective. […] The central strength of the MAL procedure is its long tradition. […] Communication is a valuable instrument; it enables the emergence of common will and shared goals. MAL procedure is on the top of all urban policy instruments that we have. (Official, Ministry of the Environment)

You can see the history there, and we are making progress all the time. This [MAL procedure] has been an excellent instrument for creating a dialogue between the municipalities, and between the state and municipalities. (Official, Ministry of the Environment)

MAL agreements are only the top of the iceberg. It is important to be certain about the commitments and common goals, but even more important is the continuing dialogue. (Official, Ministry of Transport and Communications)

While the continuous dialogue between the municipalities and the state included in MAL procedure can be interpreted to have moved towards communicatively rational processes over the years, our interviews suggest that single MAL agreement procedures, by contrast, can be still classified as processes that lean towards strategic rationality, though the existence of these processes in the MAL policy architecture was seen to be based on the more general, ideally communicatively rational dialogue between parties (see ). Strategic interests that formed the core of negotiations concerning single agreements were often seen as a prerequisite for the dialogue to start at all and to mature into a communicatively rational process later:

Agreement negotiations are a good instrument for getting things going. Only if the parties see a catch there will they come to the table in the first place. (Official, Ministry of Transport and Communications)

Figure 1. The interplay of strategically and communicatively rational processes in the architecture of the MAL policy.

The central state has been accused of being fragmented in separate sectors of administration in the negotiations, but the municipalities have also often difficulties in forming a common will. […] When the agreement negotiations start, both parties should have decided about their goals and frameworks of negotiation. (Official, Ministry of Transport and Communications)

The latest agreement negotiations did not go as planned. My own team had disagreements. This needs development. […] There were new people who did not understand, or even want to understand why this is important for the state. (Official, Ministry of the Environment)

I really do not know how to put this politely. Let’s just say that the cooperation between ministries was difficult from the beginning to the end. […] There was a time that we had to leave the agreement negotiations to go and settle our internal disagreements. (Official, Ministry of Finance)

The local actors have been also reported to have been frustrated about the lack of ‘common will’ amongst the organizations representing the central state (Hemminki and Lönnqvist Citation2022). Municipalities, however, have MAL planning preceding the MAL agreement negotiations. This enables the local actors, at least in principle, to form their ‘common will’ before the negotiations start.

Views on the interplay of MAL planning and MAL agreements

In the city-regional level of the MAL procedure, the differentiation of the (ideally) communicatively rational and strategically rational processes can be observed – based on the interviews – as the division between MAL planning and MAL agreements (). While the negotiations concerning the agreements were often described as revolving around strategic interests, the interviewees thought that more emphasis should be given to MAL planning as a platform for such processes where the actors move beyond their strategic interests, and which can in this respect be associated with communicative rationality:

MAL procedure has given rise to a dialogue between municipalities. It has made them to cooperate. […] I believe there is less suboptimization now, and this can be seen in the city-regional structural plans and other plans. (Official, Ministry of the Environment)

Some interviewees pointed out that to strengthen the communicatively rational quality of the dialogue in city-regions and to facilitate the emergence of supra-local interests or will, state actors should be present in the city-regional MAL planning process more than they are today. In the best case, this would have the consequence that the wishes of the municipalities are not unrealistic and that their ‘common will’ does not contradict the potentially more generalizable state-level goals in the agreement negotiations:

Transportation systems planning and city-regional planning … I really support all that, however we wish to name those plans, and whatever is the process of drafting the plans. […] We need that, and the state must participate in that. (Official, Ministry of Transport and Communications)

I think we are now going to the direction that the state is more involved in MAL planning, so that the interests of the state are reflected in the plans, and we would not need to open the discussion concerning the planning goals at the agreement phase. […] I have tried to avoid intervening in those local affairs that are not my business, yet I want to make sure that the whole makes sense and that the interests of the state are included in plans. (Official, Ministry of the Environment)

Views on the informality of MAL procedure

The desirability of the formalization of city-regional planning divided opinions in the interviews. The informality of the MAL procedure was appreciated because it was thought to facilitate the emergence of a non-coerced discussion ideally leading to a common vision and mutual trust both between the state and the local-level actors and between the municipalities in city-regions. Formalized processes, in turn, were often argued to foster strategic action:

Partnership-based procedures are instruments for building common visions. It does not work if it is mandatory. […] Partnerships make the actors realize that they are all on the same side of the table. Legally mandated and compulsory practices often produce juxtapositions between parties. (Official, Ministry of the Environment)

However, the fact that informal procedures do not produce legally binding outcomes troubled at least some of the interviewees representing the Centres for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment (state-level organization operating in regions and supervising and facilitating local planning). They pointed out that legally non-binding outcomes leave the municipalities with a possibility to withdraw from the agreements later if the agreements turn out to be against their strategic interests:

I definitely think that we need agreements here. But sometimes when I go through municipalities’ plans, I am a bit puzzled about the fact that municipalities refer to MAL agreements whenever it is in their interests, but they also draft local plans that do not comply with MAL agreements, forgetting all about the agreement. And we must remind them of the agreement. (Official, Centre of Economic Development, Transport and the Environment)

There are no sanctions included in the MAL agreements. But we monitor the goal-attainment. When we observe non-compliance, there is nothing we can do about it. […] Statutory, legally binding city-regional plans would ensure compliance. (Official, Centre of Economic Development, Transport and the Environment)

Carrots are better than sticks, just as they are when you raise children. But we have had a lot of discussion about the fact that there are no sanctions in MAL agreements. What can we do in the case that the goals are not met? (Official, Ministry of the Environment)

Views on the democratic quality of the MAL procedure

When the interviewees were asked about potential legitimacy problems following from the informality of the process, and especially from the lack of statutory public participation schemes, most of the interviewees asserted that more efforts should be made to inform the public about the MAL procedure and to make its decision-making structures more transparent. Many interviewees thought that statutory city-regional plans would solve this problem, but they also stated that there are other means for making the processes of decision-making more transparent and inclusive.

However, many interviewees referred to the fact that MAL plans and agreements are not binding and that the issues of democratic accountability and legitimacy should be primarily discussed in the context of legally binding municipal plans, which include statutory public engagement procedures:

I do not buy this criticism. Even though there are agreements that are made behind closed doors, all the formal plans and transport infrastructure projects have mandatory participatory mechanisms. All the things that are decided will be later opened to public participation in the formal planning processes. (Official, Helsinki Regional Transport Authority)

Many interviewees referred to the fact that the legitimacy of the MAL process is grounded on the mechanisms of representative democracy and that political decision-makers have a mandate to make certain public decisions. Most importantly, local governments have the power to decide about local-level land-use plans within the limits of the law, and the national parliament has budgetary power to decide about the investments specified in the MAL agreements, though its powers do not extend to the whole 12 years’ time that the MAL policy currently aims to cover. In addition to the logic of representative democracy, the scales of democracy were brought up by some interviewees. Some of them implied that the current criticism concerning the democracy deficit of MAL procedure mistakenly associates democracy with local democracy only, whereas the state level of democracy is for some reason regarded as less important by the critics:

The logic in this procedure is not that local actors decide by themselves that ‘if you get this, I should get that’. Instead, MAL procedure relies on openly discussed broader-level goals, on the decision-making powers of the parliament, and on the government programme. (Official, Ministry of Transport and Communications)

Some interviewees, however, stated that local-level democracy is important, but that the MAL procedure rather strengthens than threatens it, because the MAL procedure leaves more leeway for local democratic decision-making than does, for instance, legal regulation:

National political decision making can be blind to local affairs. […] MAL procedure is exactly an attempt to give attention to the local realities, and that’s where we have the second tier of democracy after the state level. (Official, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment)

It is important to have a transparent process; knowledge must be provided to the public. But citizen participation in the MAL procedure is a tricky issue. […] The knowledge that the citizens bring to the process is typically very detailed. It is valid knowledge, but it is difficult to see how it serves the national needs […] or what is its connection to city-regional planning needs. (Official, Finnish Transport Infrastructure Agency)

Discussion and conclusions

In this article, we have studied how the Habermasian concepts of strategic and communicative rationalities are reflected, first, in the research literature on strategic planning and policy making, and second, in the architecture of the Finnish MAL procedure. In so doing, our aim has been twofold. First, we have aimed to show that the Habermasian framework of rationalities is relevant not only for analyzing individual planning or policy discourses, but can also usefully contribute to the structural-level policy analysis. More precisely, the Habermasian framework suggests that rather than debating whether strategic planning can be based on communicative rationality, theories of strategic planning should examine how to structure policies so that they are communicatively rational as regards their goal setting and strategically rational as regards their implementation mechanisms. In other words, the question is how to improve both the input legitimacy and the output legitimacy of the policy (cf. Scharpf Citation1999). Second, we analyzed the interviews with the key actors involved in the MAL policy in order to find out how these seemingly contradictory rationalities find – or could be made to find – their places in the MAL policy structures.

In our interview analysis, we have discussed the interplay of the two rationalities in the MAL procedure pertaining to the relationships between, first, the state and the municipalities, second, municipalities in city-regions, and third, between the different state-level actors. As regards the relation between the state and municipalities, the interviews indicated that the current MAL procedure originates from MAL agreement negotiations that have been – and still are – mainly guided by strategic rationality and the pre-established strategic interests of the two parties. However, according to our interviewees, MAL agreement negotiations have given rise to a long-term dialogical partnership between the state and municipalities over the years. In this partnership, the actors have been at least temporarily able to rise above their strategic interests and discuss critically and reflectively their interests and the policy goals and the rules of the MAL procedure in a manner that has at least occasionally approached the features associated with communicatively rational discussion.

As regards the relation between municipalities in city-regions, MAL planning ideally provides a forum for the local-level actors to focus on the formation of their ‘common will’. According to the interviews, municipalities in the MAL city-regions have managed to establish agreements concerning their common visions relatively successfully at least when compared to the situation before the establishment of the MAL procedure. However, it remained unclear to the interviewees how broad and inclusive these consensuses were. Most interviewees were not troubled by the potential lack of citizen participation in the formation of city-regional will. Public engagement was mainly seen as an issue that is relevant for local, statutory land-use planning. While this view can be justified by the fact that city-regional planning and MAL agreements are not legally binding, unlike local land-use planning decisions, it signals a gap in the strategic architecture of the MAL procedure. The question is whether the MAL procedure can be viewed as an efficient and effective way of planning if the parties do not put their trust in the bindingness of the decisions made in this procedure.

What was missing from the structure of the MAL procedure, was a forum where the state-level actors could come together to discuss what the state wants from the MAL procedure. This might explain why the meta-governance of the MAL procedure appeared as relatively weak in the interviews. Thus, our interviews did not support the view that the state’s strategic interests saturate the MAL procedure, as some researchers have suggested (cf. Davoudi, Kallio, and Häkli Citation2021; see also Soininvaara Citation2022). The state-level actors’ analyses of the strengths and weaknesses of the MAL policy’s architecture rather suggested that the municipalities are the powerful actors in the MAL procedure.

The lack of such processes or fora where the state-level vision and the goals of the MAL policy could be formed brings us back to the role of the legislative powers at the state level and the failed attempts to solve the problems related to the steering of city-regional growth by legislative means. The state-level actors’ interviews brought to the fore the inefficiencies in the MAL procedure related to non-compliance at the local level. This raises the question of whether the state should support MAL policy by binding regulatory tools. In the Habermasian framework, binding law belongs to the steering mechanisms that lean on strategic rationality, but that can be legitimate when anchored in communicative rationality. However, in the Finnish case, such anchoring seems to be difficult to achieve in the absence of deliberative fora for discussing the state-level interests. One of the goals of MAL policy should therefore be the establishment or strengthening of such discursive fora where various kinds of actors could come together to discuss the national needs in the integrated planning of land-use, transportation and housing. For the accomplishment of this goal, it is important that even if the negotiations related to MAL agreements would take place behind closed doors, the longer-term discussion on the strategic development of MAL policy does not take place behind the backs of the citizens and the stakeholders of planning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albrechts, L. 2003. “Planning and Power: Towards an Emancipatory Planning Approach.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 21 (6): 905–924. doi:10.1068/c29m.

- Albrechts, L. 2004. “Strategic (Spatial) Planning Reexamined.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 31 (5): 743–758. doi:10.1068/b3065.

- Albrechts, L. 2010. “How to Enhance Creativity, Diversity and Sustainability in Spatial Planning: Strategic Planning Revisited.” In Making Strategies in Spatial Planning. Urban and Landscape Perspectives, Vol 9, edited by M. Cerreta, G. Concilio, and V. Monno, 3–25. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Albrechts, L., and A. Balducci. 2013. “Practicing Strategic Planning: In Search of Critical Features to Explain the Strategic Character of Plans.” DisP – the Planning Review 49 (3): 16–27. doi:10.1080/02513625.2013.859001

- Barber, B. 1984. Strong Democracy. Participatory Politics of a New Age. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bäcklund, P., L. Häikiö, H. Leino, and V. Kanninen. 2018. “Bypassing Publicity for Getting Things Done: Between Informal and Formal Planning Practices in Finland.” Planning Practice & Research 33 (3): 309–325. doi:10.1080/02697459.2017.1378978

- Bäcklund, P., V. Kanninen, and T. Hanell. 2023. “Accepting Depoliticisation? Council Members’ Attitudes Towards Public-Public Contracts in Spatial Planning.” Planning Theory & Practice 24 (2): 173–189. doi:10.1080/14649357.2023.2199459

- Brenner, N. 2003. “Standortpolitik, State Rescaling and the New Metropolitan Governance in Western Europe.” disP - The Planning Review 39 (152): 15–25. doi:10.1080/02513625.2003.10556830

- Bryson, J. 1988. “A Strategic Planning Process for Public and Non-profit Organizations.” Long Range Planning 21 (1): 73–81. doi:10.1016/0024-6301(88)90061-1

- Davoudi, S., K. Kallio, and J. Häkli. 2021. “Performing a Neoliberal City-Regional Imaginary: The Case of Tampere Tramway Project.” Space and Polity 25 (1): 112–131. doi:10.1080/13562576.2021.1885373

- Deas, I. 2014. “The Search for Territorial Fixes in Subnational Governance: City-Regions and the Disputed Emergence of Post-Political Consensus in Manchester, England.” Urban Studies 51 (11): 2285–2314. doi:10.1177/0042098013510956

- Forester, J. 1989. Planning in the Face of Power. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Forester, J. 1993. Critical Theory, Public Policy and Planning Practice. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Forester, J. 1998. “Rationality, Dialogue and Learning: What Community and Environmental Mediators Can Teach Us About the Practice of Civil Society.” Accessed October 25th, 2023. https://courses2.cit.cornell.edu/fit117/documents/samples_planning/RationalityDialogueLearning.pdf.

- Government of Finland. 2009. Valtioneuvoston selonteko kunta- ja palvelurakenneuudistuksesta. VNS 9/2009.

- Government of Finland. 2021. Luonnos hallituksen esityksestä kaavoitus- ja rakentamislaiksi. Accessed October 25th, 2023. https://www.lausuntopalvelu.fi/FI/Proposal/DownloadProposalAttachment?proposalId=17b78d7d-ad1b-41fb-8b5b-a9e7e0c798fd&attachmentId=16515.

- Granqvist, K., H. Mattila, R. Mäntysalo, A. Hirvensalo, S. Teerikangas, and H. Kalliomäki. 2021. “Multiple Dimensions of Strategic Spatial Planning: Local Authorities Navigating Between Rationalities in Competitive and Collaborative Settings.” Planning Theory and Practice 22 (2): 173–190. doi:10.1080/14649357.2021.1904148

- Habermas, J. 1982. “A Reply to My Critics.” In Habermas. Critical Debates, edited by J. B. Thompson, and D. Held, 219–283. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Habermas, J. 1984. The Theory of Communicative Action Vol. 1. Reason and the Rationalization of Society. Transl. T. McCarthy. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

- Habermas, J. 1987. The Theory of Communicative Action Vol. 2. Critique of Functionalist Reason. Transl. T. McCarthy. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

- Habermas, J. 1996. Between Facts and Norms. Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Transl. W. Rehg. Oxford: Polity Press.

- Harrison, J. 2007. “From Competitive Regions to Competitive City-Regions: A New Orthodoxy, But Some Old Mistakes.” Journal of Economic Geography 7 (3): 311–332. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbm005

- Healey, P. 1992. “Planning Through Debate.” Town Planning Review 63 (2): 143–162. doi:10.3828/tpr.63.2.422x602303814821

- Healey, P. 1996. “The Communicative Turn in Planning Theory and Its Implications for Spatial Strategy Formation.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 23 (2): 217–234. doi:10.1068/b230217.

- Healey, P. 1997. Collaborative Planning. Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies. London: Macmillan.

- Healey, P. 2007. Urban Complexity and Spatial Strategies. Towards Relational Planning of our Times. Oxon: Routledge.

- Healey, P. 2009. “In Search of the ‘Strategic’ in Spatial Strategy Making.” Planning Theory & Practice 10 (4): 439–457. doi:10.1080/14649350903417191

- Healey, P. 2015. “Civic Capacity, Place Governance and Progressive Localism.” In Reconsidering Localism, edited by S. Davoudi, and A. Madanipour, 105–125. New York, N.Y: Routledge.

- Hemminki, M., and H. Lönnqvist. 2022. MAL-sopimusmenettelyn tila ja kehittämistarpeet. Acta 280. Helsinki: Kuntaliitto.

- Hillier, J. 2002. Shadows of Power. An Allegory of Prudence in Land-Use Planning. London: Routledge.

- Hillier, J. 2003. “’Agon’izing Over Consensus: Why Habermasian Ideals Cannot Be ‘Real’?” Planning Theory 2 (1): 37–59. doi:10.1177/1473095203002001005

- Huxley, M. 2000. “The Limits to Communicative Planning.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 19 (4): 369–377. doi:10.1177/0739456X0001900406

- Hytönen, J., R. Mäntysalo, L. Peltonen, V. Kanninen, P. Niemi, and M. Simanainen. 2016. “Defensive Routines in Land Use Policy Steering in Finnish Urban Regions.” European Urban and Regional Studies 23 (1): 40–55. doi:10.1177/0969776413490424

- Ingram, D. 2019. “Strategic Rationality.” In The Cambridge Habermas Lexicon, edited by A. Allen, and E. Mendieta, 432–434. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316771303.113

- Innes, J., S. Connick, and D. Booher. 2007. “Informality as Planning Strategy.” Journal of the American Planning Association 73 (2): 195–210. doi:10.1080/01944360708976153

- Janssen-Jansen, L., and T. Hutton. 2011. “Rethinking the Metropolis: Reconfiguring the Governance Structures of the Twenty-First-Century City-Region.” International Planning Studies 16 (3): 201–215. DOI:10.1080/13563475.2011.591140

- Kaufman, J., and H. Jacobs. 1987. “A Public Planning Perspective on Strategic Planning.” Journal of the American Planning Association 53 (1): 23–33. doi:10.1080/01944368708976632

- Kunzmann, K. 2013. “Strategic Planning: A Chance for Spatial Innovation and Creativity.” disP – The Planning Review 49 (3): 28–31. doi:10.1080/02513625.2013.859003

- Mattila, H. 2020. “Habermas Revisited: Resurrecting the Contested Roots of Communicative Planning Theory.” Progress in Planning 141: 1–29. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2019.04.001.

- Mattila, H., and A. Heinilä. 2022. “Soft Spaces, Soft Planning, Soft Law: Examining the Institutionalisation of City-Regional Planning in Finland.” Land Use Policy 119: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2022.106156.

- Mäntysalo, R., L. Peltonen, V. Kanninen, P. Niemi, J. Hytönen, and M. Simanainen. 2010. Keskuskaupungin ja kehyskunnan jännitteiset kytkennät. Paras-ARTTU-ohjelman tutkimuksia nro 2. Kuntaliitto.

- Mintzberg, H. 1994. The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning. New York: Prentice Hill.

- O'Brien, P., and A. Pike. 2015. “City Deals, Decentralisation and the Governance of Local Infrastructure Funding and Financing in the UK.” National Institute Economic Review 233 (1): R14–R26. doi:10.1177/002795011523300103

- Pateman, C. 1970. Participation and Democratic Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Phelps, N., and M. Tewdwr-Jones. 2000. “Scratching the Surface of Collaborative and Associative Governance: Identifying the Diversity of Social Action in Institutional in Institutional Capacity Building.” Environment and Planning A 32 (1): 111–130. doi:10.1068/a31175

- Ravetz, J. 2013. City-Region 2020: Integrated Planning for a Sustainable Environment. Milton Park & New York: Routledge.

- Sager, T. 1994. Communicative Planning Theory. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Sager, T. 2013. Reviving Critical Planning Theory. London: Routledge.

- Scharpf, F. 1999. Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? New York: Oxford University Press.

- Scott, A. 2001. Global City-Regions: Trends, Theory, Policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Scott, A., J. Agnew, E. Soja, and M. Storper. 2001. “Global City-Regions.” In Global City-Regions, edited by A. J. Scott, 11–30. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Smas, L., C. Fredricsson, L. Perjo, T. Anderson, J. Grunfelder, and C. Dymén. 2017. Urban Contractual Policies in Northern Europe. Nordregio Working Paper 2017:3.

- Soininvaara, I. 2022. “The Political Geographies of Strategic Partnerships: City Deals and Non-Deals.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 40 (5): 1165–1181. doi:10.1177/23996544211064743

- Tiitu, M., A. Pätynen, M. Friipyöli, and A. Rehunen. 2023. “Seurantakatsaus MAL-sopimusten vaikuttavuudesta.” Ympäristöministeriön julkaisuja 2023: 21. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-361-414-7

- Timmermans, S., and I. Tavory. 2012. “Theory Construction in Qualitative Research.” Sociological Theory 30 (3): 167–186. doi:10.1177/0735275112457914

- Tønnesen, A., J. Krogstad, P. Christiansen, and K. Isaksson. 2019. “National Goals and Tools to Fulfil Them: A Study of Opportunities and Pitfalls in Norwegian Metagovernance of Urban Mobility.” Transport Policy 81 (C): 35–44. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2019.05.018.

- Vaattovaara, M., A. Joutsiniemi, J. Airaksinen, and M. Wilenius. 2021. Kaupunki politiikassa –Yhteiskunta, ihminen ja ihana kaupunki. Tampere: Vastapaino.

- Vatilo, M., H. Mattila, and P. Jalasto. 2022. Edunvalvonnasta yhteisen hyvän tavoitteluun? MAL-sopimusmenettelyn arviointi- ja kehittämisselvitys 2022. Valtioneuvoston julkaisuja 2022:47.

- Waite, D., and K. Morgan. 2019. “City Deals in the Polycentric State: The Spaces and Politics of Metrophilia in the UK.” European Urban and Regional Studies 26 (4): 382–399. doi:10.1177/096977641879

- Ward, K., and A. Jonas. 2004. “Competitive City-Regionalism as a Politics of Space. A Critical Reinterpretation of the New Regionalism.” Environment and Planning A. Economy and Space 36 (12): 2119–2139. doi:10.1068/a36223.

- Westskog, H., H. Amundsen, P. Christiansen, and A. Tønnesen. 2020. “Urban Contractual Agreements as an Adaptive Governance Strategy: Under What Conditions Do They Work in Multi-Level Cooperation?” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 22 (4): 554–567. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2020.1784115

- Wheeler, S. 2000. “Planning for Metropolitan Sustainability.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 20 (2): 133–145. DOI:10.1177/0739456X0002000201

- Ympäristöministeriö. n.d. Maankäytön, asumisen ja liikenteen sopimukset. Accessed October 25th, 2023. https://ym.fi/maankayton-asumisen-ja-liikenteen-sopimukset.