ABSTRACT

This article analyzes the implementation of a novel concept in Norwegian planning and building law (PBA), the Regional Planning Strategy (RPS), which was introduced before the 2011-2015 electoral period. How the RPS was understood and implemented is the focus of this analysis. This article presents new knowledge of how new strategic elements unfold within a country’s legal framework through its implementation in practice. We add to the planning-theory dialogue by discussing translation by regional re-contextualization in the implementation of a new element in regional strategic planning (Røvik Citation1998, Citation2002). A study of the implementation of the RPS over three ‘generations’ (2011-2022) reveals interesting and surprising differences. Drawing on translation theory, we find that the translation, contextualization, and re-contextualization of the PBA with respect to the implementation of RPSs were diverse in 2011/12, that there was a convergence in the second generation, and that diversity reappears in new ways in the third generation. This article confirms how a new idea like RPS develops in regional planning processes is dependent on the central government’s need and ability to manage the counties’ RPS work, as well as the counties’ need and ability to make regional adjustments and to set their own political priorities.

1. Introduction

1.1. Regional planning strategies (RPS) – research question

The growing interest in Europe in strategic planning, both in practice and in theory (see Albrechts Citation2012; Healey Citation2009; Balducci, Fedeli, and Pasqui Citation2011; Abis and Garau Citation2016), has contributed to the understanding of and our interest in the research on a new statutory strategic element in regional planning in Norway, Regional Planning Strategies (RPSs). This article analyzes the implementation of the RPS concept in Norwegian planning and building law, which was introduced before the 2011-2015 electoral period, as an institutional change of the regional planning system. By following the implementation practice for all Norwegian regions over three generations of RPSs from 2011 to 2022, we have addressed the following research question: As a new statutory strategic tool in the Planning and Building Act (PBA), how have the RPSs been understood and implemented? To our knowledge, Norway provides a unique case because neither an Anglo-American nor a European country has introduced the equivalent of this statutory tool at the regional planning level.

This article presents knowledge of how new strategic elements unfold within a country’s law through its implementation in practice. Moreover, we have contributed to the field of planning theory by analyzing translation as regional re-contextualization in the implementation of a new element in regional strategic planning (Røvik Citation1998, Citation2002).

This article begins with Section 1, which addresses the context of strategic planning in Europe and how Norway’s launching of the RPSs is a part of this movement. Section 1 also describes the Norwegian regional planning system briefly. In Section 2 we introduce the position of translation theory, which is applied to understand how the implementation has unfolded in Norway, combined with relevant perspectives on the co-creation of strategic planning. In section 3, we present the methods and data. Section 4 presents the analysis of the diversity of translations of the three generations of RPSs in light of the government’s understanding of the ‘master model’ and includes illustrative examples. We then discuss the implications of these translations in section 5 and conclude in section 6.

1.2. New types of strategic planning in Europe

Strategic Planning (STP) has to some extent held a subordinate and vague position. According to Albrechts (Citation2009), strategic spatial planning evolved in the 1960s and 1970s toward a system of comprehensive planning in several western European countries that integrated nearly everything at different administrative levels. When the neo-liberal paradigm replaced Keynesian-Fordism in the 1980s, Europe witnessed a retreat from both public intervention and strategic spatial planning (Albrechts Citation2009).

By the turn of the 1990s, STP experienced a renaissance. The EU launched many STP processes, such as the ESDP (European Spatial Development Perspective). Since 2000, the EU has developed, adopted, and implemented other strategic documents. Planning researchers broadly agree that this has led to greater European interest in strategic spatial planning today (see e.g. Albrechts Citation2012; Healey Citation2009; Balducci, Fedeli, and Pasqui Citation2011; Abis and Garau Citation2016).

Though there are many interpretations of STP, this statement captures the essential points: ‘ … action-oriented instead of plan-oriented, transformative instead of regulative, selectively visionary instead of comprehensive, to cope with uncertainty instead of fixing certainties, and to deal with relational space instead of the essentialist spaces of ‘zoning’ or given administrative boundaries. It is characterized by networked and co- productive governance, to transgressing boundaries between the public, private and the third sector, and between the sectors and scales within the government, as well.’ (Mäntysalo, Kangasoja, and Kanninen Citation2015).

There seem to be indications in planning research that we are about to see new styles of strategic planning: a combination of traditional and new approaches to planning of sustainable development, regional development, and ‘new’ regional politics based on the contemporary development of critical thinking and practical experiences in Europe (see Albrechts Citation2006a, Citation2006b; Healey Citation2006a, Citation2006b; Olesen and Richardson Citation2012; Mäntysalo, Kangasoja, and Kanninen Citation2015a; Purkarthofer, Humer, and Mäntysalo Citation2021).

Strategies, policies, and plans are increasingly realized in collaborative settings and processes of co-production. Here, we use the term of co-creation (Aastvedt and Higdem Citation2022), even though it has been used interchangeably with co-production (Albrechts Citation2012). Co-creation goes right to the core of strategic regional planning in the call for collaborative innovation (Sørensen and Torfing Citation2007), where all public bodies and all community organizations are exhorted to participate and contribute to more innovative and transformative practices (Albrechts Citation2006a).

Strategic spatial planning has since the early 1990s developed into an exercise in persuasive storytelling (Olesen Citation2017). The increased interest in strategic planning in the 1990s was often linked to the intended persuasiveness of spatial strategies. These strategies relied on spatial concepts and metaphors with supportive storylines that sought to gain attention and to mobilize actors around the central ideas, thus transforming how key actors thought and acted in urban areas (Healey Citation2009; Olesen Citation2017).

Regardless of planning styles, politicians seem increasingly to be in favour of STP by using plans as a frame of reference during decision-making processes (Desmidt and Meyfroodt Citation2021). Experiences with local and regional STP processes show they can be imaginative and suitable for framing citizen participation and stakeholder collaboration (Lingua and Balz Citation2019) and that transformative, innovative, and visionary STP processes can cope with wicked problems (Klijn and Koppenjan Citation2020).

1.3. A renewal and strengthening of Norwegian strategic planning

In Norway, STP has been present both in the field of practice since the 1970s (Kommunal- og regionaldepartementet Citation2001; Kommunal- og arbeidsdepartementet Citation1997), and in the field of theory (Amdam and Veggeland Citation1998, Citation2011). The Norwegian planning system is based on the Planning and Building Act (PBA Citation2008), which designates the planning system as the main tool for directing societal and territorial (spatial) development in municipalities and counties (Kommunal- og Regionaldepartementet Citation2002; Kommunal- og Moderniseringsdepartementet Citation2015; Higdem Citation2018). Local and regional elected bodies (municipality council and county council) are the main planning authorities (PBA Citation2008; Hanssen and Aaarsæther Citation2019). A distinct Norwegian example of a ‘strategic turn’ in planning has been the RPSs, which the government of Norway introduced in the revised PBA of 2008.

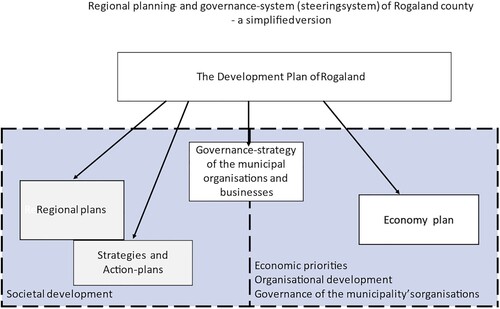

The regional planning system of Norway is illustrated in . RPS is thus defined in the statutory text section 7-1: ‘ … [RPS] shall give an account of important regional development trends and challenges, assess long-term development potentials and determine which issues are to be addressed through further regional planning’ (PBA Citation2008).

Figure 1. The Regional Planning System of Norway (Higdem Citation2018).

The regional planning authority is required to prepare a RPS every four years in close cooperation with the municipalities, the county governor, regional state, and other state bodies. The county council may also invite other organizations and institutions to participate. A RPS usually comprises these main chapters: 1) A knowledge base about the situation in the regional community; 2) An assessment of important regional development features and challenges; 3) An assessment of long-term development opportunities; 4) A presentation and assessment of National Expectations for Regional and Municipal planning (NE); 5) A decision on long-term development goals; and 6) A decision on which issues should be addressed through further regional planning.

Section 6-1 of the PBA describes the National Expectations for Regional and Municipal planning (NE) (see point 4 above). Every four years the government sends to the county councils and municipalities a proposal stating the requirements and expectations for regional and municipal planning. This proposal specifies the key challenges and policy themes for the next period that will advance the implementation of national policy. The NE also clarifies the latitude the county councils and municipalities have within the boundaries of national policy. The main intention for introducing the RPS into the regional planning system was to make the political priorities for regional planning more visible by focusing on the vital challenges and increase regional planning’s efficiency and flexibility within the framework set by the NE (Miljøverndepartementet Citation2007–Citation2008).

How to increase the efficiency of regional planning with respect to the former PBA and its practices was heavily debated (see Falleth and Johnsen Citation1996; Higdem Citation2001; Asmervik and Hagen Citation2001; Vike Citation1995; Røsnes Citation2001). Additionally, the government strengthened the principle that regionally elected bodies must bear a significant responsibility for the development of their respective region. Finally, the RPSs were understood as a better instrument for regionally adapted implementations of the central state’s policies and a tool for coordination between the major planning actors of the region (Miljøverndepartementet Citation2004).

Planning by necessity, rather than planning by duty, was prioritized, hence the strategic orientation (NOU Citation2003:14). Accordingly, the RPS included an overview of how the prioritized planning challenges should be followed up by planning instruments (Miljøverndepartementet Citation2004).

2. Theoretical position

We employ translation theory, a part of Scandinavian institutionalism (Czarniawska and Sevón Citation2005), to analyze the implementation of a new statutory strategic tool in the PBA. We shall also present the theoretical foundation for co-created strategic planning, including storytelling, which illustrates the core intentions of this new statutory strategic tool.

2.1. Translation theory and institutional theory

The Norwegian planning system is a hybrid system comprising different but side-by-side logics of steering and directing (Mahoney and Thelen Citation2010; Hanssen, Hofstad, and Higdem Citation2018). Regional planning in this context is a mediating meso-level process in a multi-level democracy (Hanssen, Hofstad, and Higdem Citation2018). Moreover, national political ambitions of addressing complex societal challenges, such as sustainable development, need to be translated into regional and local contexts (Healey Citation2006a), and to find their arena in regional planning. A networked multi-actor system where civil actors and interests are also included is addressed by planning as well as institutional scholars (see Healey Citation1998; Sagalyn Citation2007; Bevir, Rhodes, and Weller Citation2003; Rhodes Citation1991; Sørensen and Torfing Citation2005, Citation2007). Furthermore, the logic of co-creating the future through networks and partnerships is prominent in regional planning (Hanssen, Hofstad, and Higdem Citation2018; Higdem Citation2014, Citation2018).

Our point of departure is the understanding of implementation of new ideas, models, and concepts in the public sector as translational processes, where ideas are conceptualized in the implementing phase (Røvik Citation1998, Citation2007). Translation theory focuses on the circulation of ideas or recipes, and what organizations like national or regional governments may do with these ideas (Røvik Citation2002, Citation2016; Czarniawska and Sevón Citation2005). Ideas and recipes that travel may be rejected or, as in the case of the RPS, be translated to fit into a national and subsequently a regional context (Czarniawska and Joerges Citation1996; Czarniawska and Sevón Citation1996). We argue that the notion of translation is fruitful for analyzing how the introduction of a new idea like the introduction of the RPS in the regional planning system unfolded. We also identify the RPS as equally a new concept for strategic planning at the national level and a tool for strategic planning at the regional level.

Looking to the Danish model of municipal planning strategies as a starting point, the government recast the Danish example into the concept of RPA as a ‘master version’ (Røvik Citation1998) in the first interpretative stage.

The development of a RPS (PBA Citation2008) depends mainly on the national framing through the PBA, and subsequently the counties’ implementation. The implementing logic is thus a top-down process from the central government to the county level. In this top-down chain of translation within a hierarchical structure, the freedom of translation is presumably limited (Mahoney and Thelen Citation2010; Røvik Citation1998, Citation2016). There is room for local adjustments (Røvik Citation1998), but the national government (in this case) may develop mechanisms to control the implementation. The chain of interpretation will develop sequentially as a stimulus-response situation, where the contextualization of a concept and tool will proceed in steps from one hierarchical level to another. The possible translators are multiple, even in a hierarchical public order (Røvik Citation1998; Hardy, Phillips, and Lawrence Citation1998). Thus, ideas and discourses about how this new element of an RPS is to be understood and handled in practice will presumably take many forms and will be contextualized and even re-contextualized (Røvik Citation1998, Citation2007) into a new framework at several stages.

Another relevant concept is ‘regional tailoring’ – a widely used term in Norwegian within both regional research and regional planning, developmental, and innovational work (Bukve and Amdam Citation2004). ‘Tailor made’ implies that regional planning and development work is adapted to the regional context according to what is considered to be best and most appropriate for this particular regional society. The opposite is national unified management from above, that is, the same for all regions, or ‘regional ready-made’.

The room for regional tailoring also depends on the central government’s managerial and control mechanisms, like the NE. In addition, the implementation of the RPS may influence how the regional planning system is perceived and how it works in practice as a form of further regional institutionalization of a certain regional planning practice. This implies that we may find diverse forms of RPSs and therewith forms that may add to the hybridity of the regional planning system of Norway.

2.2. Co-created strategic planning

One vital part of the RPS concept is linked to co-production, or co-creation, within this multi-actor and multi-layered system. The term has been used for many years in different contexts and in different intellectual traditions, from co-production in the delivery of services to co-production as a political strategy and a method of planning (Mitlin Citation2008; Watson Citation2014; Higdem Citation2014, Citation2018; Hanssen, Hofstad, and Higdem Citation2018; Aastvedt and Higdem Citation2022).

As mentioned earlier in section 1.2. we use the term of co-creation (Aastvedt and Higdem Citation2022), even though it has been used interchangeably with co-production (Albrechts Citation2012). The activity of co-creation is used to ‘enhance the production of public value for example in terms of visions, plans and policies’ (Aastvedt and Higdem Citation2022, 60). It emphasizes the substantial engagement of citizens and grassroots organizations (Le Galés Citation2002; Higdem Citation2014) and a process ‘more realistically grounded in citizen preference’ (Irvin and Stansbury Citation2004, 55).

As mentioned above, co-creation captures an essential element of the RPS and regional planning where all public bodies and community organizations are called to participate and contribute to more innovative and transformative practices (Albrechts Citation2006a). In this sense, it is an expression of a development of collaborative and communicative planning (Watson Citation2014). This new procedural practice reflects our understanding of relational complexity (Healey Citation2006a), in that such planning ‘needs to be highly selective, focusing on the distinctive histories and geographies of the relational dynamics of a particular place. It may recognize borders and cohesions, but also the tensions, exclusions and conflicts which these generate’ (Healey Citation2006b, 542).

It is also worthwhile pointing out that distinctive stories or storytelling is closely linked to both coproduction and co-creation, and to key planning concepts like dialogical, collaborative, and communicative planning (Healey Citation1997; Forester Citation1999; Sager Citation2013; Harper and Stein Citation2012). These concepts and related theories are also clearly relevant in the analysis of strategic planning. Albrechts, Healey, and Kunzmann (Citation2003) argue that much of the power of strategic spatial planning lies in its use of concepts and images to mobilize and fix attention. Planning fundamentally revolves around the successful use of language – spoken, written or as maps and images (Hellspong Citation1992, Citation1995; Ramirez Citation1995a, Citation1995b; Asmervik and Hagen Citation2001).

3. Method and data

Our evaluation of the RPS work is limited to (1) the process leading up to the RPS adopted by the county council in all the counties, (2) the product, the actual RPS document, and (3) the national approval – relevant only for the first generation. The requirement for national approval was later abolished, and the county council itself now approves the RPS.

We have assessed the RPS work in light of the relevant legislation, the PBA, and the NE. Both the law and the specific national letter of expectations place demands and expectations on the county councils, which ultimately adopt the final RPS text. We have examined how the RPS is understood, interpreted, and implemented as practice, that is, as the planning strategy process and the adopted planning strategy document.

At the same time, the entire RPS institute rests on a necessary premise that many different actors actually do their part by understanding, interpreting, and implementing the planning strategy.

Our data comprises documents about and from the RPS processes in all the counties in Norway. There were 19 counties until 2018, 18 until 2020, and 11 until 2024. We examine the process up to and including the adopted RPSs. We have not included an investigation of how the adopted RPSs have been followed up or the impact they have had on regional planning activity in the four-year electoral period for which the RPS applies.

Our data is based on the study of these documents: (1) the PBA of 2008 with changes, preparatory work for the PBA, and the guidance material for the RPS; (2) all RPSs developed in 2011-2012, 2015-2016, and 2019-2020, and the case papers following the discussion and the adoption of the RPSs; (3) the ‘National Expectations of Local and Regional Planning’ and the central state’s letters of final approval to each RPS developed in 2011-2012.

The data from the first and second RPS generations has been published in Norwegian from the now-finalized EVAPLAN-research project (Higdem and Hagen Citation2017; Higdem and Jacobsen Kvalvik Citation2018). Research on the third generation RPS and the analysis of the whole timespan are therefore new.

4. Analysis

To classify the RPSs, we have developed a list of criteria of key elements related to the RPSs. The criteria are taken from 1) what is expected of RPSs in the PBA as a process, as a document, and as an element of a comprehensive regional planning system, and 2) what is expected of the follow-up and implementation of NE.

4.1. The first generation of RPS 2011/12

The two main dimensions of how the counties have implemented the RPSs are (1) whether or to what degree the counties have complied with the PBA’s provisions of the RPS, and (2) whether or to what degree the counties have addressed, answered, and complied with the NE. shows the implementation status for the first round with RPSs. The two dimensions (axes) constitute (1) the ‘master model’ of how an RPS is to be understood and implemented – the procedural and model axis – and (2) the substantial axis, meaning the central government’s expectations of what policy themes the RPS is to encompass and assess. In the scheme below, the two dimensions are the two axes that form the four-field table below.

Table 1. RPS first generation 2011-2012. The counties’ four types of adaptations to implementation.

On the horizontal (x) axis (PBA), the law-abiding counties comply with the law’s provisions, whereas the disobedient deviate from these or have significant shortcomings. The disobedient counties either do not follow up the process provisions in the law – that is, that the RPS must be prepared in cooperation with organizations, the municipalities, the county governor, regional state, and other state bodies – or they deviate when it comes to the design of the document and the overall regional planning system.

On the vertical (y) axis (NE), the dutiful are those counties that address, answer, and comply with national policy expectations and adhere to it. The independent are those that regard the national policy expectations through their own regional context and interpretative and translational frame. The independent also tend to offer the central government policy advice or demands based on their assessment of the regional development challenges ahead. They put forth policy recommendations for issues where the central state holds the authority, such as policy means and measures for agriculture, fishery or employment.

Consequently, four different types of adaptations emerge. We have called the four types as follows: the loyal, the challengers, the heretical, and the policy-developers. There are different degrees and sorts of adaptations within each main type, since there is a continuum along both axes. These are ideal types, therefore. The presence of RPSs in each group illustrates the vast diversity of implementing practices in this first round in 2011-2012. Before describing these types, we need to mention that Norway had 19 counties until 2018, then 18 counties until 2020, and since January 1, 2020, there are 11 counties.

The loyal – 6 counties – were the counties that complied both with the law and with the NE. However, we find that there are many forms of loyalty. For instance, a county may be loyal to the NE while also raising critical questions and demanding a closer dialogue with the central government.

The challengers – 4 counties – represented the combination loyal and disobedient; though they are loyal to the NE, they contested the interpretations of the RPS according to the PBA and the guidance booklet.

The policy-developers – 6 counties – are independent and law-abiding, meaning that the execution of the RPS was according to the PBA, but they took an independent stand from the NE. Their own professional and political analyses and understandings rather than those of the NE influenced their picture of the actual challenges for their county. An example from two counties in the middle of Norway illustrate that translation is the dominant view regarding the NE. By way of introduction to this view in the RPSs, they referred to the Government Cabinet’s own directive: ‘The Government Cabinet has in earlier directives on regional planning stated that the goals and directions the central state points to will not be equally important in all counties and municipalities.’ Therefore, the main issues for the county and municipal planning were the counties’ and the municipalities’ own policies. Accordingly, the counties interpreted the power of direction of the NE and the counties’ own legitimate use of discretion as follows: ‘The Government Cabinet therefore expects that those who participate in the planning processes to develop good comprehensive solutions in a regional and local perspective. Consequently, the Cabinet paves the way for local and regional competence represented by the local and regional political bodies and the elected representatives to practice the necessary discretion and to provide for local and regional added value.’

The heretical – 3 counties, complied neither with the PBA’s provisions of a regional planning strategy nor with the NE. They asserted their own political and planning methodological realities. The challengers and the heretical had in common the development of an STP rather than an RPS to come. We also observed examples where central actors such as the county politicians, the county as an organization, the municipalities, and the regional partnerships utilized the goals and strategies of the RPS as a planning document in their own planning (Bråtå et al. Citation2014; Higdem and Hagen Citation2015). In contrast, the two types differed on a central provision of the PBA: the challengers had also worked out an overview of which plans were to be made during the four-year period to come, which was a planning strategy.

Regardless of this diversity, the government approved all RPSs of the first generation, as our analysis of the letters of approval show (Higdem and Hagen Citation2017). However, the government’s feedback identified these deviations and deficiencies: a) the absence of an overview of future planning tasks, b) the failure to account for the NE, c) national challenges not resulting in regional planning, and d) the presence of too many plans or plans that do not accord with the PBA.

4.2. The second generation of RPS 2015/16

Convergence is the leading characteristic of the second generation of RPSs (Higdem and Jacobsen Kvalvik Citation2018). One probable reason for this development was the government’s thorough feedback to the first-generation RPSs. All the counties’ RPSs were approved, but they also received advice on improvements. The most disobedient received specific advice about necessary changes (see last paragraph in section 4.1. above). The data shows that the counties chose to listen to this advice in the second round of RPSs.

Another reason for the convergence could also be the exchanges that took place after the first round. Planners and politicians had met, and they discussed and learned from each other while also choosing to abide by what the government had reported to them. All this led to a kind of uniformization. A more unified opinion of the right way of conducting RPS processes and designing RPS documents emerged in the regional community of planners and politicians.

The government adjusted the PBA with effect from 1 January 2017. The requirement for national approval was removed, giving the county councils the final authority (PBA Citation2008). However, this took place after the counties had conducted their second round of RPSs, starting in autumn 2015 and ending in spring-summer 2016. Thus this development first became relevant for the third-generation RPSs.

The government had also previously revised PBA section 7.1, adding ‘to take a stand on long-term development goals’ in § 7.1 (Lovdata lov/2008-06-27-71). This came into effect from 1 January 2015. Thus, the RPS could develop more in the direction of becoming a planning document instead of a strategy for the future planning tasks of the county. This change in the law may have contributed to more divergence, or more ‘regional tailor-made’ elements, by giving the counties an expanded scope for RPS process and content. However, at this point, the convergence mechanisms were probably stronger. This change in the law first contributed to more divergence in the third generation RPS.

4.3. The third generation of RPS 2019/20

In 2015, the UN’s member states announced the 17 goals of sustainable development for 2030, and in 2019 the NE (2019- 2023) was launched (Nasjonale forventninger 2019-2023).

Because of the UN’s 17 goals, a new NE, and the two major changes in the PBA (presented above in section 4.3.), it was interesting to observe in the third generation of RPSs the renewed development of diverse practices between counties and wider translations of the RPSs, as well as quite new adaptations. See .

Table 2. RPS third generation 2019-2020. The counties’ four types of adaptations to implementation.

In the third generation of RPSs, our analysis shows there were no adaptations and no translations in the Loyal category. No RPSs complied both with the law and the NE of 2019. However, we find RPAs in the three other categories.

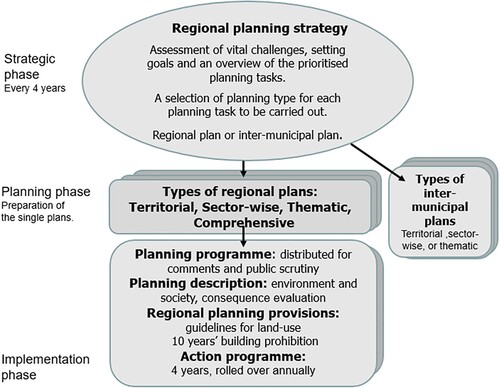

The challengers – 3 counties – disputed the goals of RPSs according to the PBA, but were loyal to the NE. These counties translated the RPS from a strategy of future planning tasks into a plan for the county. In doing so the counties’ political planning authority discussed and decided upon a common strategic spatial plan which set the direction for the counties themselves, the regional state bodies, and the local municipalities. For example, one county called their RPS ‘The development plan for Rogaland’ (Rogaland fylkeskommune Citation2021), see .

The RPS, which was introduced as a strategy in the revised PBA of 2008, had become a regional plan for the challengers. In a way, it is a return to the situation before the RPS was introduced into Norwegian planning legislation and its associated practice.

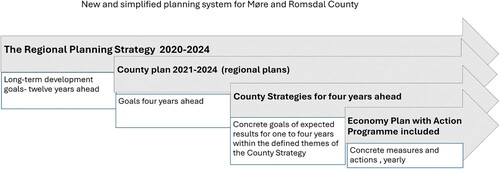

The policy-developers – 4 counties – abided by the PBA’s expectations regarding the understanding of an RPS, but they neglected to take the NE into account. The UN’s goals of sustainable development (UN17) were implemented as superior to the NE. The RPSs in the policy-maker group focused on how the UN17 were to be implemented in the RPS. The policy-developers shared another characteristic in that the RPS also consisted of an independent understanding of the county’s regional planning system, which not only applies, but also extends the PBA. One example is how Møre and Romsdal county developed its planning system (see ). They placed the RPS at the top of the planning hierarchy, as prescribed by the PBA. This was thus a translation within the law-abiding column (see ). They chose to retain the traditional comprehensive county plan that was required by law until the RPS was introduced. In addition, they inserted a self-developed third level in the planning hierarchy – County Strategies – before the next statutory period, the four-year economic plan with action programme.

Figure 3. Policy-developers – Translations of the RPS into the regional planning system in Møre og Romsdal County.

The Heretical – 4 counties – were both disobedient to and independent of the RPS provisions of the PBA and NE, though in varying degrees. At the same time, we must note that the same counties took the UN17 into account. This meant that all Norwegian counties, regardless of how they chose to translate the RPS provisions and NE, related loyally to the UN17 in their RPS documents.

5. Discussion

We have noted how the Norwegian model derived its first interpretative stage from the Danish model of municipal planning strategies by recasting it to the concept of not a local but a Regional Planning Strategy, the RPS, as a ‘master version’ (Røvik Citation1998). Both the RPS and the NE were written into the planning legislation, and a new phase of Norwegian regional planning was introduced.

By drawing on translation theory, we can now turn to an account of the translation, contextualization, and re-contextualization regarding the RPS and the NE.

5.1. The theories have strong descriptive power

After carrying out this RPS study, we can confirm that the notion of translation is fruitful for analyzing how the introduction of the RPS in the regional planning system unfolded (Røvik Citation2002, Citation2016; Czarniawska and Sevón Citation2005; Czarniawska and Joerges Citation1996; Czarniawska and Sevón, Citation1996). We are left with the unequivocal impression that the theoretical contributions presented in section 2.1. effectively explain the translation, contextualization, and re-contextualization that had occurred when introducing the RPS in Norwegian regional planning.

The implementation of the RPS and the NE in the Norwegian hybrid planning system – characterized by side-by-side logics of steering and directing (Mahony & Thelen, 2010; Hanssen, Hofstad, and Higdem Citation2018), the presence of mediating meso-level process in a multi-level democracy (Hanssen, Hofstad, and Higdem Citation2018), and the intention for the national and regional political goals to address complex societal challenges – inherently involve translation, contextualization, and re-contextualization (Healey Citation2006a). This will inevitably lead to some differences.

Furthermore, our RPS study has confirmed that planning theories understood as co-creating stories about the past, the present, and the future through networks and partnerships also have substantial descriptive power in studies of Norwegian regional planning. Co-creation captures RPS-process ideals.

Not least, our research shows that the third generation of RPS is characterized by strong storytelling ambitions. The planners and politicians came to realize how important ‘persuasive storytelling’ is – orally, textually, and visually, through pictures, figures, tables, videos and so on (see Throgmorton Citation1992; Healey Citation2009; Olesen Citation2017). Persuasive storytelling is particularly demanding because the RPS process constantly involves many participating actors from several different environments who may well have different ways of communicating. Hence, we view the RPS as a planning situation with a high degree of ‘relational complexity’ (Healey Citation2006b; Bevir, Rhodes, and Weller Citation2003; Higdem Citation2015; Higdem and Sandkjær Hanssen Citation2014) that impacts the storytelling.

5.2. Varying degree of diversification by implementation

Our theoretical stance predicted a certain degree of diversification. Nevertheless, the diversification was larger than expected because of the intentions of the government when introducing the RPS and the NE. This diversification seems to be particularly notable in the third round with RPS.

This theoretical stance also confirms that what results from the various RPS processes depends mainly on the national framing through the PBA, including governmental managerial and control mechanisms, and subsequently the counties’ implementation (Mahoney and Thelen Citation2010; Røvik Citation1998, Citation2016).

In our RPS study, we have clearly confirmed that the understanding and implementation of this new element of RPS by the many different actors who participated in these co-creation processes varied considerably (Røvik Citation1998, Citation2007). This variation seems to be particularly prominent in the third generation of RPS.

This variety supports the already vast evidence in the literature of the challenges concerning top-down implementation (see Hill Citation2013; Røvik Citation1998). Since this hierarchy consists of publicly elected regional bodies with a certain degree of autonomy from the central government (the counties and the municipalities), the counties take the liberty to translate the PBA into their own regional contexts. Both regional politicians and planners thus shared a common desire for a certain degree of autonomy in their implementation of this new tool.

5.2.1. Law-abiding

In section 4, and , we analyzed RPS along two axes, with the x-axis indicating the degree of regional adjustment given by law. One explanation for the fact that a third of the counties in the third generation acted disobediently is that they chose to maintain the county planning tradition, where the RPS was contextualized and formed as a long-term plan. This adaptation can also point to a regional need, both professionally and politically, for comprehensive regional planning based on regional political assessments of challenges and ambitions. Though the current PBA downplays holistic planning built upon a region’s own defined premises, these counties have taken a shortcut by using the RPS as the overall and comprehensive strategic plan and have translated the law in a way that is useful for their own regional needs or demands.

Therefore, we argue that the realization of new regional planning system may not fulfil the intended consistency between strategies for planning and the planning itself, and instead contributes to hybridization. The central government has also contributed to hybridization with the latest amendments in the PBA since 2014 by requiring long-term development goals to be stated in the RPS for the future (cf. 5.2.3).

5.2.2. NE-abiding

Compliance along the other axis, the NE, is quite another story. Since the late 1990s, national authorities have expected the counties to develop a regional policy based on the region’s own challenges and resources. This constitutes a ‘regime shift’ from a national allocation or re-distribution of resources for regional development to a more endogenous and regional resource-based approach (Bukve and Amdam Citation2004) in collaboration with both public and private actors. Several White Papers have stressed this shift (Kommunal- og Regionaldepartementet Citation2001, Citation2002; NOU Citation2003:14), and since 2015 the counties’ strategic and direction-setting function for regional planning has been paramount. The counties are obliged to provide a comprehensive assessment and contextualization of the many priorities of the central state with respect to actual regional challenges (Kommunal- og Moderniseringsdepartementet Citation2015).

In this sense, the counties’ re-contextualization of the NE materialized as expected. The interesting findings here lie in the government’s response in the first generation of RPS. We find that the letters of final approval show that the government’s limited acceptance of contextualization. In other words, they reveal a narrow interpretation of the regional freedom (and expectation) to assess the national goals into the actual regional situation. The central government is torn between the notion of (and need for) flexibility in planning and the need for control or direction setting in policy- and strategy-making. Here, the need for setting a direction won.

Research shows that it is quite common for the government to speak equivocally when it comes to regional and local self-government. It both pays tribute to local and ‘regional tailoring’ and at the same time emphasizes the important role counties and municipalities have to play in ensuring the implementation of national policy.

Therefore, county politicians and planners can rightly claim that they are loyal implementers of national policy when they contextualize RPS in the sense that they are ‘independent’ concerning NE, but loyal to various regional policy White Papers (see above).

The above analysis illustrates that the national storytelling about RPSs – the legal text, booklet of guidance t-1495, NE, conferences, and seminars – lacks rhetorical power. The national storytelling can override neither the counties’ own regional political prioritizations nor competing national regional political signals in the various White Papers. The counties choose to co-create their own political frames for regional development, their own regional plans, and their own stories about the past, the present, and the future.

5.2.3. Governmental managerial and control mechanisms

Seen in retrospect, if the government concludes that diversification has gone too far in the third generation of RPS, they should analyze the consequences of the revisions of the PBA that came into effect on 1 January 2017. The requirement for national approval was removed, and the county councils were granted final authority (Statutory Data Act/2008-06-27-71).

The government did not disapprove of any of the RPSs in the first round, but they also provided thorough commentaries on what they deemed positive and in accordance with the PBA and the NE, and what they thought should be changed and improved. Consequently, the counties experienced a narrowing of the latitude for regional contextualization (Røvik Citation1998). The central government re-contextualized the counties’ space of action by their role as approving authority and by thorough corrections and feedback of what was lacking.

The government succeeded with its feedback in its call for stronger loyalty to the national legislation and expectations. From diversity in the initial implementing stage, we find convergence in the second generation (2015-2016) into the categories Loyal or Translators. The RPSs represent an almost identical story about the present and the future as we find in the NE and in the PBA. The challenges and the long-term developmental goals are the same, and few counties made clear their thematic and political priorities.

The cause of the vast diversity in the first generation may also be understood as a lack of understanding among all those who participated in the various RPS processes of what the new tool, RPS, was supposed to do. In the second round the planners, politicians, and all other participants have learned their lessons. Loyal translation requires that the participants understand and are able to implement what is required in the legal text and letter of expectations.

In the third generation, the counties and all other actors who participated in RPS processes have built up a knowledge of the legal intentions of RPS and NE, but also of the opportunities that lie in designing RPS in line with their own regional political ambitions. When the government lacks the tools to correct the counties, there is room for the counties to be both independent and disobedient.

6. Conclusion

The RPS was introduced before the 2011-2015 electoral period as an institutional change in the regional planning system. It has indisputably established itself as a popular change among the majority of politicians and planners for renewing and strengthening the strategic aspects of the counties’ societal planning.

We have confirmed that the central government’s need and ability to manage the counties’ RPS work and the county municipalities’ ability and need to make regional adjustments affects how a new idea like the RPS develops in regional planning processes. All the other participants in the RPS processes have also contributed to translations and interpretations.

Furthermore, our observed RPS practices demonstrate the explanatory power of theories of translation and re-contextualization in implementation (see Røvik Citation1998; Hardy, Phillips, and Lawrence Citation1998). They describe a specific strategy element within Norwegian regional planning in a relevant and precise way.

We also note that the rise in diverse practices between counties and the wider translation of the RPSs, as well as quite new adaptations or figurations of the third generation, illustrate that the regional planning authorities actively use the RPS as a tool for regional tailor-made policies, thereby taking greater responsibility for their own societal development. As a strategic activity, the RPS provides an arena where the knowledge base, long-term goals, and strategies are co-created through storytelling between a broad set of actors at the county level.

Our research also suggests that central authorities generally value regional RPS variations. Our data, however, also indicates that both the regional and national governments evade regional political governance to a certain extent, even though the variations could (or should) have implications for the PBA – a fact that should also engage the national government.

Finally, it is important to remember that the main intention for introducing the RPS into the regional planning system was to set targets for the political priorities for regional planning by focusing on the vital challenges and increasing regional planning’s efficiency and flexibility within the framework set by the NE (Ministry of the Environment, 2007–2008). We argue therefore that all four ideal groups of translation (see )– loyal, challengers, policy-developers, and heretical – should become more aware of the necessity for regional planning’s main activity. That is how the counties in their Regional Planning Strategy practice, may become brave in their regional tailor-made policy-making role, and enhance their ability to prioritize their most important regional planning tasks accordingly.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aastvedt, A., and U. Higdem. 2022. “Co-creation, Collaborative Innovation and Open Innovation in the Public Sector: A Perspective on Distinctions and the Convergence of Definitions.” Nordic Journal of Innovation in the Public Sector 1: 53–68.

- Abis, E., and C. Garau. 2016. “An Assessment of the Effectiveness of Strategic Spatial Planning: A Study of Sardinian Municipalities.” European Planning Studies 24: 1.

- Albrechts, L. 2006a. “Shifts in Strategic Spatial Planning? Some Evidence from Europe and Australia.” Environment and Planning A 38 (6): 1149–1170.

- Albrechts, L. 2006b. “Bridge the gap: From Spatial Planning to Strategic Projects.” European Planning Studies 14 (10): 1487–1500.

- Albrechts, L. 2009. “From Strategic Spatial Plans to Spatial Strategies.” Planning Theory & Practice 10: 142–145.

- Albrechts, L. 2012. “Reframing Strategic Spatial Planning by Using a Copoduction Perspective.” Planning Theory 12 (1): 46–63.

- Albrechts, L., P. Healey, and K. Kunzmann. 2003. “Strategic Spatial Planning and Regional Governance in Europe.” Journal of the American Planning Association 69 (2): 113–129. doi:10.1080/01944360308976301.

- Amdam, J., and N. Veggeland. 1998. Teorier om samfunnsplanlegging. [Theories on Planning]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Amdam, J., and N. Veggeland. 2011. Teorier om samfunnsstyring og planlegging. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Asmervik, S., and A. Hagen. 2001. “Planning as Rhetoric: An Examination of the Rhetoric of County Planning in Norway.” Housing, Theory and Society 18: 148–157.

- Balducci, A., V. Fedeli, and G. Pasqui. 2011. Strategic Planning for Contemporary Urban Regions: City of Cities: A Project for Milan. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.

- Bevir, M., R. Rhodes, and P. Weller. 2003. “Traditions of Governance: Interpreting the Changing Role of the Public Sector.” Public Administration 81: 1–17.

- Bråtå, H., U. Higdem, K. Gløtvold-Solbu, and M. Stokke. 2014. Partnerskap - positivt for regional utvikling og utfordrende for kommunal forankring. En evaluering av partnerskapsinstituttet i Oppland. Lillehammer: Østlandsforskning.

- Bukve, O., and R. Amdam. 2004. “Regimeskifte på norsk. [A shift in regimes of Norwegian regional policy].” In Det regionalpolitiske regimeskiftet - tilfellet Norge. [The Shift in Regimes of Norwegian Regional Policy], edited by R. Amdam, and O. Bukve, 311–329. Trondheim: Tapir.

- Czarniawska, B., and B. Joerges. 1996. “Travel of Ideas.” In Translating Organizational Change, edited by B. Czarniawska, and G. Sevón. Mouton: Walter de Gruyter.

- Czarniawska, B., and G. Sevón. 2005. Global Ideas: How Ideas, Objects and Practices Travel in a Global Economy. Copenhagen: Liber & Copenhagen Business School Press.

- Desmidt, S., and K. Meyfroodt. 2021. “What Motivates Politicians to use Strategic Plans as a Decision-Making Tool? Insights from the Theory of Planned Behaviour.” Public Management Review 23: 447–474.

- Falleth, E., and V. Johnsen. 1996. Samordning eller retorikk? Evaluering av fylkesplanene 1996 - 99. [Coordination or rhetoric? Evaluation of County plans 1996-99]. Oslo: Norsk Institutt for By- og Regionforskning.

- Forester, J. 1999. The Deliberative Practitioner: Encouraging Participatory Planning Processes. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Hanssen, G., and N. Aaarsæther. eds. 2019. Plan- og bygningsloven. Fungerer loven etter intensjonene? Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Hanssen, G., H. Hofstad, and U. Higdem. 2018. “Regional Plan.” In Plan- og bygningsloven. Fungerer loven etter intensjonene?, edited by G. Hanssen, and N. Aaarsæther. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Hardy, C., N. Phillips, and T. Lawrence. 1998. “Distinguishing Trust and Power in Interorganizational Relations: Forms and Facades of Trust.” In Trust Within and Between Organizations, edited by C. Lane, and R. Bachmann. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Harper, T., and S. Stein. 2012. Dialogical Planning In A Fragmented Society: Critically Liberal, Pragmatic, Incremental. London: London Transaction Publishers.

- Healey, P. 1997. Collobrative Planning. London: MacMillian.

- Healey, P. 1998. “Building Institutional Capacity Through Collaborative Approaches to Urban Planning.” Environment and Planning 30: 1531–1546.

- Healey, P. 2006a. “Transforming Governance: Challenges of Institutional Adaptation and a new Politics of Space.” European Planning Studies 14 (3): 299–320.

- Healey, P. 2006b. “Relational Complexity and the Imaginative Power of Strategic Spatial Planning.” European Planning Studies 14 (4): 525–546.

- Healey, P. 2009. “The Pragmatic Tradition in Planning Thought.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 28: 277–292.

- Hellspong, L. 1992. Konsten att tala. Övingsbok i praktisk retorik. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Hellspong, L. 1995. “Retorik och praktisk logik.” Nordplan Meddelande 4.

- Higdem, U. 2001. “Planlegging på fylkesnivå. [Planning on County level].” In planlegging.no! Innføring i samfunnsplanlegging, edited by N. Aarsæter, and A. Hagen. Oslo: Kommuneforlaget.

- Higdem, U. 2014. “The co-Creation of Regional Futures: Facilitating Action Research in Regional Foresight.” Futures (57): 41–50.

- Higdem, U. 2015. “Assessing the Impact on Political Partnerships on Coordinated Meta-Governance of Regional Government.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration 19: 89–109.

- Higdem, U. 2018. “Regional planlegging – mellom stat og kommune.” In Plan og samfunn, edited by N. Aarsæther, E. Falleth, T. Nyseth, and R. Kristiansen. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Higdem, U., and A. Hagen. 2015. Oppfølging av Regional planstrategi for Oppland, 2012 - 2016 - en vurdering. Working paper. Lillehammer: Høgskolen i Lillehammer.

- Higdem, U., and A. Hagen. 2017. “Variasjon, mangfold og hybriditet. Implementering av regional planstrategi i Norge.” Kart og Plan 77 (1): 40–53.

- Higdem, U., and K. Jacobsen Kvalvik. 2018. “Regional planstrategi – strategi for planlegging eller ny fylkesplan?” In Plan- og bygningsloven 2008 – fungerer loven etter intensjonene?, edited by G. Hanssen, and N. Aaarsæther. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Higdem, U., and G. Sandkjær Hanssen. 2014. “Handling the Two Conflicting Discourses of Partnerships and Participation in Regional Planning.” European Planning Studies 22: 1444–1461.

- Hill, M. 2013. The Public Policy Process. Essex: Pearson.

- Irvin, R., and J. Stansbury. 2004. “Citizen Participation in Decision Making: Is it Worth the Effort?” European Political Science 64 (1): 55–65. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2004.00346.x.

- Klijn, E., and J. Koppenjan. 2020. “Debate: Strategic Planning After the Governance Revolution.” Public Money & Management 40: 260–261.

- Kommunal- OG Regionaldepartementet. 2001. St. meld. nr. 34 (2000 - 2001)Om distrikts- og regionalpolitikken. Oslo: Kommunal-og Regionaldepartementet.

- Kommunal- OG Regionaldepartementet. 2002. St.meld.nr.19 (2001-2002) Nye oppgaver for lokaldemokratiet - regionalt og lokalt nivå. Oslo: Kommunal- Regionaldepartementet.

- Kommunal-OG Arbeidsdepartementet. 1997. St. meld. nr. 31 (1996 - 1997) Om distrikts- og regionalpolitikken. [White paper on the rural-and regional policy]. Oslo: Kommunal- og arbeidsdepartementet.

- Kommunal-OG Moderniseringsdepartementet. 2015. Meld.St. 22 (2015-2016). Nye folkevalgte regioner - rolle, struktur og oppgaver. (New regions - role, structure and tasks]. In: Moderniseringsdepartementet, K.-O. (ed.). Oslo: Statens forvaltningstjeneste.

- Le Galés, P. 2002. European Cities: Social Conflicts and Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lingua, V., and V. Balz, eds. 2019. Shaping Regional Futures. Designing and Visioning in Governance Rescaling. Berlin: Springer.

- Lovdata lov/2008-06-27-71. URL: https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/2008-06-27-71, 12.02.2024

- Mahoney, J., and K. Thelen. 2010. Explaining Institutional Change: Ambiguity, Agency, and Power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mäntysalo, R., J. Kangasoja, and V. Kanninen. 2015a. “The Paradox og Strategic Spatial Planning: A Theoretical Outline with a View on Finland.” Planning Theory & Pratice 16 (2).

- Miljøverndepartementet. 2004. Ot.prp.nr 47 (2003 - 2004). Om lov om endringer i plan- og bygningsloven (konsekvensutredninger). In: Miljøverndepartementet (ed.). Oslo: Statens Forvaltningstjeneste.

- Miljøverndepartementet. 2007-2008. Ot.prp. nr 32 (2007-2008) Om lov om planlegging og bygesaksbehandling (plan-og bygningsloven) (plandelen). [On law of planning- and building ]. In: Miljøverndepartementet (ed.). Oslo: Statens forvaltningstjeneste.

- Mitlin, D. 2008. “With and Beyond the State: Coproduction as a Route to Political Influence, Power and Transformation for Grassroots Organizations.” Environment and Urbanization 20: 339–360.

- NOU. 2003:14. Bedre kommunal og regional planlegging etter plan-og bygningsloven. The planning law's suggestion part 11. Oslo.

- Olesen, K. 2017. “Talk to the Hand: Strategic Planning as Persuasive Storytelling of the Loop City.” European Planning Studies 25: 6.

- Olesen, K., and T. Richardson. 2012. “Strategic Planning in Transition: Contested Rationalities and Spatial Logics in Twenty-First Century Danish Planning Experiments.” European Planning Studies 20: 10.

- PBA. 2008. Lov om planlegging og byggesaksbehandling [The Planning-and building act].

- Purkarthofer, E., A. Humer, and R. Mäntysalo. 2021. “Regional Planning: An Arena of Interests, Institutions and Relations.” Regional Studies 55: 773–777.

- Ramírez, J. 1995a. “Skapande mening: Bidrag til en humanvetenskaplig handlings- og planeringsteori.” Stockholm, Nordplan Avhandling 13 (1).

- Ramírez, J. 1995b. “Skapande mening. En begreppsgenealogisk undersöking om rationalitet, vetenskap och planering.” Stockholm, Nordplan Avhandling 13 (2).

- Rhodes, R. 1991. “Policy Networks and sub-Central Government.” In Markets, Hierarchies & Networks. The Coordination of Social Life, edited by G. Thompson, J. Frances, R. Levacic, and J. Michell. London: SAGE Publications.

- Rogaland Fylkeskommune. 2021. Regional Utviklingsplan for Rogaland -regional planstrategi 2021-2024. https://www.rogfk.no/vare-tjenester/planlegging/utviklingsplan-for-rogaland-regional-planstrategi/

- Røsnes, A. 2001. “Norsk regional planlegging - umulig enhet eller mulig mangfold? [Regional Planning in Norway - an Impossible Unity or a Possible Diversity?].” Kart og Plan 94: 213–228.

- Røvik, K. 1998. Moderne organisasjoner. Trender i organisasjonstenkningen ved årtusenskiftet. [Modern Organisations. Trends in Organisational Thinking at a new Millenium]. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Røvik, K. 2002. “The Secrets of the Winners: Management Ideas That Flow.” In The Expansion of Management Knowledge. Carriers, Flows, and Sources, edited by K. Sahlin-Andersson, and L. Engwall, 113–143. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Røvik, K. 2007. Trender og translasjoner : ideer som former det 21. århundrets organisasjon. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Røvik, K. 2016. “Knowledge Transfer as Translation: Review and Elements of an Instrumental Theory.” International Journal of Management Reviews 18 (3): 290–310. doi:10.1111/ijmr.12097.

- Sagalyn, L. 2007. “Public/Private Development. Lessons from History, Research and Practice.” Journal of the American Planning Association 73: 7–22.

- Sager, T. 2013. Reviving Critical Planning Theory. Dealing with Pressure, Neo-Liberalism, and Responsibility in Communicative Planning. London: Routledge.

- Sørensen, E., and J. Torfing. 2005. “The Democtratic Anchorage of Governance Networks.” Scandinavian Political Studies 28: 195–218.

- Sørensen, E., and J. Torfing, eds. 2007. Theories of Democtratic Network Governance. Houndmills: Palgrave.

- Throgmorton, J. 1992. “Planning as Persuasive Storytelling About the Future: Negotiating an Electric Power Rate Settlement in Illinois.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 12: 17–31.

- Vike, H. 1995. Evaluering av fylkesplan for Telemark. En vurdering av plan og prosess. [Evaluation of the County Plan of Telemark. An Assessment of the Plan and the Process]. Bø: Telemarksforskning.

- Watson, V. 2014. “Co-production and Collaboration in Planning – The Difference.” Planning Theory & Pratice 15: 1.