Abstract

The 2011 Libyan civil war prompted a reassessment of the normative foundation of the EU's conventional arms export control regime as armaments manufactured in Europe were used by Gaddafi's forces during the war. The EU's foreign policy identity is based, partly, upon a common approach to arms export involving respect for common criteria for export licences. Yet, prior to the civil war, considerable amounts of military equipment had been exported by member states to Libya, notwithstanding grounds for restraint on the basis of several of the criteria. This article traces member states' arms export to Libya during 2005–2010 to explore whether member states favoured restraint or export promotion. It concludes that although aware of the risks of exporting, in a competitive market for military goods, member states sought commercial advantage over restraint, and comprehensively violated export control principles. This casts doubts on assertions of the EU acting as a “normative power”.

1. Introduction

The February 2011 eruption of civil war in Libya cast a spotlight on European Union (EU) member states’ arms sales to the country. When protests against his regime began in Benghazi on 15 February 2011, as part of the broader movement of pro-democracy uprisings of the Arab Spring, Colonel Gaddafi launched an armed crackdown on demonstrators, and within days a civil war engulfed most of the urban areas of the country. In the weeks after the onset of the civil war, media and civil society attention was drawn towards the over a billion Euros worth of armaments originating in EU member states that were put on display as they were used in the crackdown against the anti-Gaddafi demonstrators. Up until 2004 the Gaddafi regime had been subject to long-standing United Nations (UN; 1992–2003) and EU (1986–2004) arms embargoes due to its support for terrorist organizations. When the civil war began these sanctions had been lifted. However, as Europe-manufactured weapons were used by Gaddafi’s forces against the Libyan population during the civil war, controversy arose because arms export had taken place despite the problematic record of the long-standing Gaddafi regime, and despite the existence of a comprehensive EU conventional arms export control regime laying out best practice standards for arms export. Under this regime, which had developed under the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) since the early 1990s, member states had committed to restraint in case of a risk that the armaments transferred could be used for repressive purposes or cause internal and/or regional instability, i.e. exactly the types of actions they were used for in Libya. Interpreted according to their “spirit”, critics argued, the provisions of the export control regime, as laid out in the EU Code of Conduct on Arms Exports and later the Council Common Position 2008/944/CFSP, should have prevented many of the transfers to Libya. Eventually, the arms sales sparked widespread calls from civil society for a revision of the EU’s export control regime so as to fill the loopholes that had enabled risk miscalculations and permissive export practices to Gaddafi.

Ironically, the export control regime was initially triggered by European countries’ weapons sales to Iraq prior to the 1990–1991 First Gulf War. Europe-manufactured weaponry contributed to Saddam Hussein’s military capability, and were a concern when European troops fought Iraqi forces during the First Gulf War (Cornish Citation1995). This had illuminated the inadequacies of purely national arms export control efforts (and in many cases, the lack thereof), and the need for coordinated export controls to prevent another Iraq. The regime that came out of this environment has been gradually strengthened over the past two decades, signalling increased commitment to conventional arms export control among EU member states. Arms export to the Gaddafi regime had taken place notwithstanding this regime. This triggered the accusation – by media, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and academia – that member states had prioritized material interests over the moral considerations they were preaching, and that the normative power was engaging in organized hypocrisy.

The arming of Libya in the years prior to the civil war raises important questions about the relationship between restraint and export in member states’ arms export. In this article we trace member states’ exports and export control policies to Libya between 2005 and 2010, the years between the previous arms embargoes and the civil war (under which new arms embargoes were invoked), in order to explore the extent to which member states favoured restraint or export. By looking into the grounds for restraint in arms export to Libya, export licence denials,Footnote1 the aggregate quantity of exported weapons, and the nature and potential usage of the exported weapons, we obtain a good picture of the relationship between risk assessments and arms export to the country, on the basis of which judgements about the relationship between restraint and export – and eventually compliance with regime provisions – can be made.

The theoretical discussion we address – the relationship between norms and interests in the foreign policies of states – is old but persistently salient, particularly when the object matter is the EU. A thriving debate takes place between those maintaining that the EU conducts its foreign policy on the basis of norms and those arguing that norms are undermined when states are faced with more pressing material temptations. The arms trade is a powerful test case of commitment to norms since it serves strategic, economic, and industrial material interests, but in some circumstances also compromises security, undermines development, and facilitates grave violations of human rights. This makes it one of the most controversial of all trades. Given the high profile of the arms trade and its consequences, there is a surprising paucity of scholarly scrutiny of how adopted norms on arms export work (or not) in practice. This article contributes to reducing this research void. Particularly, case studies assessing how norms and material incentives interplay in arms export to countries of concern can provide important understanding to how normative power and material incentives work in practice.

The following section presents our theoretical assumptions about factors likely to motivate the export and control of conventional weapons. We proceed with accounting for the norms that apply to the arms export of member states, which provide the indicators upon which we assess performance. We then trace and debate member states’ restraint and export, respectively, in the arms export to Libya. We conclude that notwithstanding grounds for greater restrictiveness in the arms export to Libya, individual member states favoured narrow economic and strategic interests over the pursuit of endorsed multilateral values.

2. Normative power and organized hypocrisy

What logic drives the EU’s foreign policy? Is the EU driven by norms? Do the strategic interests of individual member states trump endorsed values? These are frequently asked questions. Considerable academic attention has been devoted to assessing the image of the EU as a “civilian power” (Duchêne Citation1972, Citation1973, Bull Citation1982) and as a “normative power” (Manners Citation2002, Citation2008, Youngs Citation2004). According to Manners (Citation2002), the EU pursues its core values through economic and diplomatic foreign policy strategies to such an extent that we can speak of a “Normative Power Europe” (NPE). Following Manners (Citation2002, p. 241):

[t]he EU has gone further towards making its external relations informed by, and conditional on, a catalogue of norms which come closer to those of the European convention on human rights and fundamental freedoms […] and the universal declaration of human rights […] than most other actors in world politics.

The NPE assumption sees the EU and its member states as motivated by a “logic of appropriateness”, in which political action is understood as “a product of rules, roles and identities” (Krasner Citation1999, p. 5). In the words of Krasner (Citation1999, p. 5), “the question is not how can I maximize my self-interest but rather, given who or what I am, how should I act in this particular circumstance”. Consequently, the EU will act on the basis of the moral values and the identities inhabiting it. At the broadest level, the “appropriate” norms generally believed to influence EU strategy and action relate to the values of democracy, the rule of law, social justice, human rights, fundamental freedoms, and multilateralism, which were first stated in the 1973 Copenhagen Declaration (King Citation1999, Manners Citation2002). Notwithstanding possible intra-EU variation over the strength of the various norms, following the NPE assumption, these liberal values are at the core of the overall EU normative framework. They define what the EU conceives of as “good behaviour” – a conception upon which it acts – and permeate all parts of EU’s law, foreign policy positions, and engagements, including the EU’s common approach towards conventional arms export control. As the next section shows, the conventional arms export control regime itself contains language that resonates the values that the NPE assumptions are built upon. Proponents of the NPE will therefore argue that the export control regime, laying out moral correctives for the arms trade to adjust by, is deliberately designed on the basis of underlying identity and norms. If indeed it is the case that states act on the basis of NPE appropriateness, we can therefore expect to find that arms export practices comply with the norms of the export control regime in the sense that if there are grounds for restraint (of all or some types of weaponry) on the basis of conditions addressed by the regime, weapons will not be exported.

A number of critical studies have shown how the NPE, rather than a reflection of reality, is an exaggerated construct which is severely threatened when ideals meet interests (see Kagan Citation2003, Forsberg and Herd Citation2005, Hyde-Price Citation2006, Citation2008, Erickson Citation2013). Rather than evidence in support of behaviour based on the logic of appropriateness and NPE, these studies find that member states’ foreign policies express the rational pursuit of material interests. Accordingly, the motivational logic underlying their foreign policies is better described as “logic of consequences”, in which political action is embedded in rational calculating behaviour in pursuit of instrumental and material gain (Krasner Citation1999). Pointing at the fact that ethical agendas will be pursued only if they do not come at the expense of these interests, the findings of these studies echo the anticipation of structural realism, to which multilateral norms are not a check on state interests, but a product of them (Waltz Citation1979, Mearsheimer Citation1994). Following structural realism, states may embrace norms in order to look good or to coordinate behaviour, but what ultimately counts in foreign policy is securing more fundamental interests of power, security, and survival. Consequently, norms tend to work only at the margins, in areas of low politics, ruling out effective cooperation in areas where cooperation can have real or perceived implications for member states’ security and foreign policy strategies (Mearsheimer Citation1994). If states act on the basis of consequentialism they will calculate what kind of action yields the greatest benefits in terms of material gain, such as economic profit and security. If the benefits of exporting to problematic recipients perceivably exceed the benefits of restraint, states will export notwithstanding norms.

Scholarly debates on whether NPE reflects on reality suggest that some issue areas lend themselves more easily than others to the argument that the EU acts as a normative power. Empirical evidence suggests that the EU acts on the basis of NPE and logic of appropriateness in cases where the costs of doing so were low or the norms in question were relatively uncontroversial, such as in the area of death penalty (Manners Citation2002, Menon et al. Citation2004, Scheipers and Siccurelli Citation2007). Empirical evidence moreover suggests that priorities may differ in issue areas wherein states risk losing revenue or risk a real or perceived weakening of their strategic positions (Hyde-Price Citation2006, Citation2008, Erickson Citation2013). This may potentially threaten the pursuit of norms in arms export control due to the nature of the arms trade; arms export indirectly serves the exporter’s security through enhancing a defence-industrial base, and can be strategically beneficial through cementing relations with the recipient state. As post-cold war European defence industries have relied heavily on exports to offset low defence budgets (Cornish Citation1995), arms export is vital to serve such foreign policy goals. Defence industries also generate revenue and jobs; thus, securing lucrative contracts may have positive domestic ripple effects on the exporting country. Indeed, defence job losses would be unwarranted for any EU government in the context of recent years’ economic recession, which led to cuts in defence-industrial spending and reinforced the export dependence (Jackson Citation2013). In the arms export to Libya, member states were clearly balancing moral and material considerations.

3. The EU conventional arms export control regime

Arms export control has traditionally been the concern of national governments, and has been closely associated with national security and sovereignty. During the formation of the European Economic Community, European states enshrined and institutionalized national sovereignty over the production and transfer of arms through Article 223 of the 1957 Treaty of Rome (currently Article 346 of the Treaty of Lisbon). Article 346 allows a member state to take all necessary measures “it considers necessary for the protection of the essential interests of its security which are connected with the production of or trade in arms, munitions and war material”. A common approach to conventional arms export nevertheless developed from the early 1990s onwards. The trigger was the “boomerang effect” of weapons exported to Iraq prior to the First Gulf War and the scandals that followed in its aftermath (Bauer Citation2003, Holm Citation2006). Other influences were calls for a moral order to the arms trade following its negative association with human security and development (Garcia Citation2011), as well as calls from the defence industry in member states for a level playing field for industry. The logic in the level playing field rationale was that common export control norms would reduce competitive disadvantages through subjecting European manufacturers to equally stringent rules in the contracting and competitive post-cold war armaments market (Davis Citation2002, p. 251, Bauer Citation2003, p. 66).

The specific export rules member states were subject to in the 2005–2010 period were those currently laid out in Council Common Position 2008/944/CFSP (CP; Council of the European Union Citation2008). The CP dates back to 1991 and efforts taken within the intergovernmental European Political Cooperation (EPC) process, when the Ad Hoc Working Group on Conventional Arms Export (later turned into the Council Working Group on Arms Export [COARM]) was mandated to compare national positions and practices, and explore possibilities for coordinated action on arms export control (Cornish Citation1995, p. 20–21).Footnote2 The result was the identification of eight “common criteria” (presented later), whose purpose and application were not specified until June 1998. By 1998, the combination of examples of dubious transfers, export scandals, and a broader international norms cascade promoting conventional arms export control triggered the adoption by the Council of the European Union (Council) of the politically binding EU Code of Conduct on Arms Exports (CoC) as a Council Declaration. The CoC formalized the application of the eight criteria, in addition to establishing several operative provisions (mechanisms for consultation and transparency) meant to promote implementation and convergence. Member states were asked but not required to consider the eight criteria when deciding whether or not to issue export licences (Council of the European Union Citation1998). This changed in 2008, in the middle of the time period under scrutiny in this article, when the CoC – following pressure for a stronger and more binding commitment after multiple revelations about dubious transfers, also after 1998 – was replaced by the legally binding CP. Member states were now obliged to apply the following eight criteria on a case-by-case basis when considering export licence requests for items on the EU Common Military List (described in brief below):

Respect for the international obligations and commitments of member states;

Respect for human rights conditions in the country of final destination as well as respect by that country of international humanitarian law;

Internal situation in the country of final destination, as a function of the existence of tensions or armed conflicts;

Preservation of regional peace, security, and stability;

National security of member states and of territories whose external relations are the responsibility of a member state, as well as that of friendly and allied countries;

Behaviour of the buyer country with regard to the international community, as regards in particular its attitude to terrorism, the nature of its alliances, and respect for international law;

Existence of a risk that the military technology or equipment will be diverted within the buyer country or re-exported under undesirable conditions;

Compatibility of the exports with the technical and economic capacity of the buyer, taking into account the desirability that states should meet their legitimate security and defence needs with the least diversion of human and economic resources for armaments.Footnote3

Common positions and joint actions, introduced by the Maastricht Treaty, per definition belong to the legal instruments of the Council under the CFSP.Footnote4 Once unanimously adopted, Article 29 of the Treaty of the European Union (TEU) states that “member states shall [emphasis added] ensure that their national policies conform to [common positions and joint actions]”. However, it is up to governments to determine the extent to which CP and JA language is to be transposed into national law, and member states retain sovereignty over interpreting the export control criteria and issuing licences. The combination of a fairly high level of obligation but decentralized enforcement relates to the intergovernmental nature of the CFSP, which also exempts the CP and the JA from European Commission infringement proceedings and the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice (Lustgarten Citation2013). The persistence of Article 346 stands as a further symbol of the preference for sovereignty in this area. Despite the weak legal status resulting from intergovernmental design, the adoption of the CP was interpreted as an increased commitment to arms export control, thus raising anticipations about intentions to comply.

Arguably, the most important elements of the CoC/CP, setting it apart from other regional agreements (and the JA), are efforts taken under the auspices of COARM to harmonize the interpretation of the eight criteria. First, a denial notification mechanism requires bilateral consultations when a state considers the granting of an export licence that is “essentially identical” to a licence another member state has denied within the past three years (so as to prevent undercutting). Second, several documents facilitate harmonization in the implementation of the CoC/CP, such as the Common Military List, an extensive document listing the equipment covered by the CoC/CP. This list is a vital element in ensuring that member states apply the CoC/CP to the same equipment. In addition, COARM has since 2003 published a lengthy and periodically updated user’s guide to the implementation of the CoC and CP. In the user’s guide, principles briefly stated in the CoC/CP have been buttressed by reams of common practices detailing how they should be interpreted. Also, the Official Journal of the European Union publishes a consolidated annual report on the implementation of the CP which is compiled by COARM on the basis of member states’ annual reports. The annual reports – that serve as the major basis for our assessment of export practices to Libya – include a detailed summary of the data on arms export provided by member states, as well as aggregate data on licence denials. Third, one of the most powerful aspects of the CoC and CP is the socialization of officials from disparate member states around the export control norms – taking place both in the bilateral consultations and in the regular general discussion at monthly COARM meetings – that has arguably facilitated the development of shared understandings of interpretation of the licensing criteria (Bauer Citation2003).Footnote5 Annual meetings between COARM and civil society also give civil society the opportunity to pose questions about confidential COARM activities.

It is not difficult to spot a potential clash between the requirements imposed by the regime and the pursuit of narrow economic and strategic interests which may encourage exports to dubious regimes unless these are perceived as direct threats to member states and their interests. The following sections describe and analyze the arms export of member states and the level of restraint during 2005–2010.

4. An emerging market

Libya was for years subject to long-standing UNFootnote6 and EUFootnote7 arms embargoes due to its support of terrorist organizations. The lifting of the embargoes was preceded by three events: Gaddafi (1) accepted responsibility for a series of terrorist attacks against Europe and the USA, (2) presented himself as a partner in the war on terror, and (3) announced the dismantling of Libya’s weapons of mass destruction programmes. With the regime appearing to turn its back on its long-standing pariah status, the main reasons underlying the EU and UN arms embargoes were removed, and a major policy shift towards Libya arose. In the following years Libya made its entrance into the diplomatic embrace of the EU, its member states, and the wider international community. In January 2008 and March 2009 Libya held the rotating presidency of the UN Security Council, and 2008 marked the beginning for EU–Libya talks about a framework agreement aiming at strengthening bilateral relations (European Commission Citation2009). Gaddafi was, in short, to become socialized into the right values and proper behaviour. This change also illustrated a vital aspect: during these years European states believed – or were hopeful – that Gaddafi was on a normalization path. This was a factor that was likely to affect, along with export control norms and material incentives, the export approach vis-à-vis Gaddafi. Moreover, it was anticipated that Libya would seek to exploit the lifted sanctions to modernize its conventional weapons arsenal which had mostly been procured from the Soviet Union in the 1970s and early 1980s (Lutterbeck Citation2009, Holtom et al. Citation2010). This could, however, not happen without willing suppliers. After the embargoes were lifted, EU member states could, in theory, start to export arms to Libya. However, as shown below, Libya posed a clear risk under several of the criteria of the CoC and the CP, also during 2005–2010. Of the eight common criteria, we focus on all but the first, third, and eighth.Footnote8 Examples of actual exports contravening the criteria are considered later.

4.1. Grounds for restraint

A key means of assessing risk is to assess a regime’s current actions in combination with its history. This approach is at the heart of the EU’s export control regime. The CoC and CP call for assessment of the “record” of the buyer country with respect to the conditions in the licensing criteria (Council of the European Union Citation2008). The user’s guide to the CP further details that there is intra-EU agreement on the importance of examining a regime’s history and past record when assessing the risks associated with internal repression, violations of human rights and of international humanitarian law, armed conflict with neighbouring states, weapons being supplied to organizations involved in terrorism or organized crime, and diversion to unauthorized end-users (Council of the European Union Citation2009). Importantly, the past record of Libya was of particular relevance because Gaddafi's four-decade-long reign implied that his regime held a continuity which did not exist in the vast majority of other states, wherein a change in leadership may well represent a definitive break from the past. Assessments of history would hence have played a major role – along with current conditions – in the risk assessments. In the following, we assess the grounds for restraint based on these criteria.

4.1.1. Respect for human rights in the country of final destination as well as respect by that country of international humanitarian law (criterion 2)

Under criterion 2, member states were required to consider the human rights conditions in the receiving country, “exercise special caution and vigilance […] where serious violations of human rights have been established”, and abstain from exporting under a “clear risk” that the equipment exported might be used for internal repression. Over the period 2005–2010 human rights monitoring reports consistently highlighted serious human rights violations in Libya. These included routine torture of detainees, imprisonment of people engaged in peaceful political activity, shooting and killing of demonstrators, “severe” curtailment of freedom of association and expression (including bans of independent NGOs and media sources), and arbitrary arrest.Footnote9 Furthermore, an examination of the long-term human rights trends shows that the situation in Libya had been unchanged throughout the period in question. The Political Terror Scale (Gibney et al. Citation2013) gave Libya the same assessment every year during 2000–2010, considering it to be a state in which “[t]here is extensive political imprisonment, or a recent history of such imprisonment. Execution or other political murders and brutality may be common. Unlimited detention, with or without a trial, for political views is accepted”. Similarly, the widely used Polity IV scale (Gleditsch Citation2013), which measures the extent to which a state is democratic or authoritarian on a scale from 10 (full democracy) to −10 (full autocracy), gave Libya a value of −7 throughout all of Gaddafi’s reign. While Colonel Gaddafi made a show of re-engaging with the West, throughout the 2000s, there was no significant change in Libya’s governance.

The important distinction in criterion 2 is the risk of the equipment exported being used for internal repression. The equipment of greatest relevance to criterion 2 is that used by police and military to facilitate human rights violations. Of particular interest is equipment such as small arms (Amnesty International Citation2010, p. 5) and armoured vehicles which are used when detaining individuals.

4.1.2. Preservation of regional peace, security, and stability (criterion 4); and national security of the member states and of territories whose external relations are the responsibility of a member state, as well as that of friendly and allied countries (criterion 5)

Both criteria 4 and 5 concern the likelihood that exported armaments will be used aggressively against another country. Libya has a long record of conflict with its neighbours. As Sturman (Citation2003) writes, “[d]uring Gaddafi’s leadership, Libya has been in conflict with almost all of [its] neighbors”. Under Gaddafi Libya had invaded neighbouring Chad several times; annexed part of the territory of Niger; had a week-long border war with Egypt; deployed troops to Uganda to support President Idi Amin; deployed troops to the Central African Republic; supported military coups in Ghana, the Gambia, and Niger; and had territorial disputes with neighbouring Algeria, Niger, and Tunisia (Solomon and Swart Citation2005; Sturman Citation2003). This long history of intervention in armed conflict is of direct relevance to the instruction in the user’s guide, which states that EU governments should assess whether a potential recipient has “tried to resolve the issue through peaceful means, […] tried in the past to assert by force its territorial claim, or […] threatened to pursue its territorial claim by force” (Council of the European Union Citation2009, p. 63). Export of many types of major conventional weapons, such as fighter aircraft and armoured vehicles, could influence Libya’s offensive capabilities to affect regional peace and the security of EU member states and their friends, allies, and territories abroad.

4.1.3. Behaviour of the buyer country with regard to the international community, as regards in particular its attitude to terrorism, the nature of its alliances, and respect for international law (criterion 6)

The previous UN and EU arms embargoes were enacted following Libya’s support for terrorist activities, specifically the bombing of a Berlin discotheque and of an airliner flying above the UK. Libya’s sponsorship of international terrorist organizations during the 1970s–1990s is summarized by Blanchard and Zanotti (Citation2011), who describe there were:

training camps in Libya and other Libyan government support for a panoply of terrorist groups including the Abu Nidal Organization, the Red Army Faction, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC), and the Irish Republic Army. Libyan-sponsored bombings and assassinations also drew sharp international criticism, especially killings of Libyan dissidents and the bombings of Pan Am Flight 103 and UTA Flight 772 in the late 1980s.

4.1.4. Existence of a risk that the military technology or equipment will be diverted within the buyer country or re-exported under undesirable conditions (criterion 7)

In addition to the above acts, the Gaddafi regime had been involved in supplying arms to opposition movements in Sudan, Somalia, Algeria, Mauritania, Mali, Senegal, and Tunisia (Solomon and Swart Citation2005). In particular, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Libya supplied arms to the embargoed Charles Taylor’s regime in Liberia, and to the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) in Sierra Leone via Liberia and Burkina Faso. The final report of the Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Citation2004, p. 76–77) notes that “Liberia, Burkina Faso and Libya constituted a network of support for the RUF” and further that:

Arms and ammunitions were flown from Libya via Burkina Faso and Liberia to the RUF. […] In December 1998 two Ukrainian planes loaded with arms and ammunition from Libya flew into Monrovia at midnight. The arms and ammunitions were then loaded into four trailer trucks […]. Three of the trucks went to Lofa country from where the arms and ammunitions were transported to the RUF base in Kono.

To sum up this section, Libya was by no means an unproblematic recipient of military equipment in 2005–2010 with respect to the most relevant licensing criteria. A policy of cautious restraint, such as that followed by the USA, was appropriate until seeing how the course taken on by Gaddafi evolved. Instead, several EU governments appeared to view the Gaddafi regime as an export bonanza.

4.2. Restraint

Upon receiving export licence applications, a government either issues a full or partial approval and exports, or issues a licence denial if exporting is deemed too risky on the basis of one or more licensing criteria. It is possible to see considerations of Libya’s past and present records on the conditions addressed in the licensing criteria being made in the export licence denials to Libya during 2005–2010. Information on licence denials is limited due to imperfect transparency,Footnote10 and also does not perfectly match what is being denied, as a formal denial will not be issued in cases where applicants receive an informal denial. The available information is presented in and the remainder of this section.

contains the information available in the EU’s consolidated reports compiled by COARM. The denials show intra-EU recognition that Libya remained a problematic destination for a number of reasons, and that member states thus exerted some level of carefulness. Nevertheless, the ratio between denials and approvals has consistently and increasingly favoured approvals, suggesting an export-friendly approach in the majority of cases. Human rights conditions were cited most frequently as the reason for denial, followed by the risk of diversion, the national security of member states and allies (presumably a reference to states in North Africa with relationships with EU member states), considerations of regional stability, and the behaviour of the regime with respect to the international community. Over the period 2005–2010, diversion became the second most frequently cited criterion.

Table 1. Licence denials and authorizations reported by EU member states.

National reports provide more detailed information on denials and reasons thereof. While these vary, Germany, in particular, has provided more data on licence denials to Libya than other EU exporters. As shown by , Germany in total denied 20 licences during 2005–2010 (no denials in 2005), and where a reason was given there is a clear emphasis upon the risks of use for internal repression, in wars involving other states in the region, or diversion. Notably, the denials in 2008 were reported to be for contracts worth some EUR 131 million, exceeding the value of granted licences (Germany Citation2009). Despite being one of the world’s largest producers and exporters of small arms, Germany also did not license exports of small arms to Libya – a clear indication that it did not consider Libya an appropriate destination for that type of equipment.

Table 2. Licence denials reported by Germany, 2006–2010.

The UK in 2007 denied four licences for large-calibre ammunition, electronic equipment, and dual-use items (technology with both civilian and military applications) under the auspices of criterion 5 (national security of member states and allies) and criterion 7 (risk of diversion; United Kingdom Citation2008a). The UK stopped reporting grounds for licence denials after 2007. In 2008–2010 equipment denied by the UK to Libya included assault rifles, weapon (night) sights, gun-laying equipment, gun mountings, weapon sight mounts, military image intensifier equipment, military utility aircraft, small arms ammunition, sporting rifles, and equipment and components for these.Footnote11 In October through December 2008 alone the UK denied the transfer of 130,000 assault rifles (United Kingdom Citation2008b), arguably because of “[concern] that the intention may be to re-export the weapons, particularly to armed rebel factions backed by Khartoum and/or Ndjamena in the Chad/Sudan conflict” (Doward Citation2011). Assault rifles could be used, inter alia, for violations of criteria 2 and 7.

Overall, there was a tendency to deny material that could directly be used for internal repression, in armed conflict, or be diverted. Both the UK and Germany, for instance, reported denials of small arms (such as assault rifles) and ammunition, which would most likely be used by police or military units to detain civilians or suppress riots. Denials were also made by both states for military vehicles. These details are important, because as is shown below, this did not prevent exports of similar equipment by other EU member states.

Cautious sentiment was also expressed through debates within COARM about a post-embargo toolbox. Initially, this idea came up in 2004 in connection with the contested arms embargo on China, where a post-embargo toolbox was intended to prevent a notable rise in exports to accommodate the concerns of those objecting the upheaval of the embargo. The toolbox would entail detailed information exchange every three months on granted export licences (quantity and type of the military equipment, the end-use, and the end-user; Anthony and Bauer Citation2005, Bromley Citation2012). As the embargo on Libya was the first to be lifted following these discussions, NGOs lobbied for a toolbox on Libya. The issue was on the agenda of annual meetings between COARM and civil society (the so-called “COARM–NGO” meetings). As discussions in COARM are confidential it is difficult to know how far this debate came in COARM, but political interest in the toolbox was quite low, and it was never adopted. The issue came up again following the 2011 Libyan civil war, with NGOs maintaining that recent export practices highlighted the need for exactly such a tool. However, political interest still appears to be lacking.

5. Scrambling for market shares

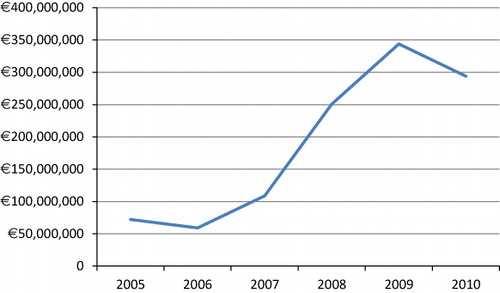

, based on consolidated reports for 2005 through 2010, reveals a remarkable increase in the value of granted export licences from member states to Libya during these years. During 2005–2010, the total value of arms export licences granted to Libya from EU member states was approximately EUR 1130 million.Footnote12 The annual totals are influenced by Bulgaria joining the EU in 2007, but the overall trend is robust to the exclusion of Bulgaria. Moreover, between 2005 and 2010 there was a slight increase in transparency, that is, improvement in reporting, but not one which could explain the increase (Lazarevic Citation2012, p. 294). In general, deficiencies in transparency in arms export by EU member states concern a lack of specificity caused by the use of broad weapons categories rather than detailed descriptions, and reliance upon licensing and financial data (rather than number of units and actual deliveries). This means that it would be very unlikely for there to have been large-scale “covert” exports to Libya by EU member states during 2005–2010 which were not reported at all.

Note: For all EU states, data compiled from the consolidated annual reports.

Libya evidently was a clear cause for concern regarding the risks that exported equipment might be used for internal repression, in armed conflict with states in the region, or be diverted to unauthorized end-users; these concerns were reflected in the licence denials. lists examples of actual exports of materiel likely to be used in these circumstances. Although Germany and the UK had denied substantial amounts of small arms, there were major transfers of small arms from Belgium, France, and Italy. These weapons could be directly used for both internal repression inside Libya, and in wars with its neighbours; moreover small arms are the weapons most suitable for diversion to non-state groups in Africa. Similarly, anti-tank MILAN missiles supplied by France would play a direct role in interstate warfare and would also be attractive for non-state groups. Supplies of ammunition are essential for any sustained police or military operation and can also be diverted, and while some ammunition was denied by the UK and Germany, significant supplies were reported to have been exported by France, Italy, Spain, and even the UK. The refurbishment of jet fighters in Libya’s air force provided by France would have enhanced Libya’s ability to threaten its neighbours; similarly the helicopters provided by Italy could have provided transport of armed forces in Libya’s desert border regions. The military vehicles exported by the UK, Italy, and Germany could have been used by police or military units for internal repression. Finally, the tactical communications system exported by the UK would have dramatically improved the Libyan army’s ability to coordinate and fight a regional or internal opponent.

Table 3. Exports of military equipment from EU member states to Libya 2005–2010.

The manner in which Gaddafi was very actively courted by the leading EU arms exporting states promoting the export of a range of military equipment to Libya soon after the UN and EU arms embargoes were lifted is telling for our assessment of the relationship between norms and material incentives in the arms export towards Libya because it suggests that the licence denials presented above constitute exceptions in an overall export-friendly environment. The heads of government of the UK, France, and Italy visited Gaddafi, accompanied by representatives from arms companies and rumours of considerable arms deals (Holtom et al. Citation2008, p. 302). As described by Martinez (Citation2008, p. 130), there appeared to be a tough competition for market shares. A leaked UK Ministry of Defence report from late 2006 described Libya as a “priority area” for arms export from the UK (Guardian Citation2011), and during the 2010 LibDex arms fair in Tripoli over half of the exhibitors were from the UK (Wezeman Citation2011). High officials, such as Prime Minister Tony Blair, played a major role in marketing UK defence products. The Telegraph reported that the UK Government in 2010 had even directly approached Khamis Gaddafi, the son of Colonel Gaddafi and military commander of the 32nd Brigade, in order to offer arms deals (Telegraph Citation2011). The 32nd Brigade committed serious human rights violations during the 2011 civil war. Interestingly, official UK documents even show a case wherein an export licence for armoured military vehicles was granted after extensive deliberations because the delivery might be problematic on the basis of criterion 2 (United Kingdom Citation2009). The UK reported that:

[a]n export licence was received for Armoured Personnel Carriers and components for the Libyan police. […] We have concerns with Libya’s human rights record. Particularly relevant was an incident in 2006 where the police handled a riot situation poorly resulting in the deaths of civilians.

[w]hilst a risk remained that these vehicles could be used in poorly managed crowd control situations, it was assessed that the training provided sufficiently mitigated the risk, and that the vehicles and the training combined gave the Libyan authorities the ability to exercise control without resort to lethal force. There remain wider human rights risks in Libya, but it was judged very unlikely that these vehicles would be used to carry out abuses. (United Kingdom Citation2009)

Since the uprisings and demonstrations began, the Government has been vigorously backpedalling on its arms exports to North Africa and the Middle East […] We conclude that both the present Government and its predecessor misjudged the risk that arms approved for export to certain authoritarian countries in North Africa and the Middle East might be used for internal repression. We further conclude that the Government’s decision to revoke a considerable number of arms export licenses to […] Libya […] is very welcome. (House of Commons Citation2011)

Among the most controversial of the licences granted to the Gaddafi regime was a Belgian small arms deal illustrating clearly how commercial interests had overridden Belgian commitments under the CoC/CP. In May 2008, Belgian FN Herstal signed a EUR 12 million contract for the delivery of small arms to Gaddafi’s 32nd Brigade. In a confidential report of February 2009, the advisory commission monitoring Walloon compliance with Belgian and EU arms export laws strongly disallowed most of the deal over its breaching criteria 2 (human rights) and 7 (diversion; Spleeters Citation2012). Nevertheless, the Walloon Government – which is both the licensing authority and sole owner of FN Herstal – decided to issue the licence in June 2009 following pressure from FN Herstal and the regional labour unions (Amnesty International Citation2011, Spleeters Citation2012). One month later, a federal court rescinded the licence, but the delivery had already taken place. The deal was widely criticized for undermining Walloon and Belgian legislation and EU norms.

Another controversial deal was the export of Spanish cluster munitions. In April 2011 the NGO Human Rights Watch and a reporter for the New York Times reported that Spanish-made MAT-120 cluster munitions had been used by the Gaddafi regime’s forces against civilians in Misrata during the civil war (Chivers Citation2011a). The 2008 Cluster Munitions Convention (CMC) had banned the use and transfer of such weapons; thus initially it was a mystery how the munitions had found their way into Libya. Investigation unveiled that the cluster munitions had been transferred by Spain in 2006 and 2008 (Chivers Citation2011b, Mines Action Canada Citation2011, p. 168–169). At the intercessional meeting of the CMC in June 2011, Spain made a full statement in which it regretted the use of Spanish cluster munitions in Libya. Interestingly, the last shipment was made two months prior to the adoption of the CMC, and three months before Spain announced a moratorium on transfers of cluster munitions (Mines Action Canada Citation2011, p. 169). As New York Times reporter Chris Chivers (Citation2011b) put it:

As Spain was considering entering the convention banning cluster munitions, one of its cluster-munitions manufacturers was busily marketing its stock. The Spanish government, on the cusp of deciding to ban cluster munitions, then approved the transfer of MAT-120s to Libya with just months to spare.

6. Conclusions

Despite multiple reasons for cautious arms export to Libya on the basis of the principles of the CoC/CP, EU member states, faced with new market opportunities and a competitive export environment, began to very actively market and export arms to the country. Clearly, Gaddafi indulged in a buyer’s market. As securing lucrative arms deals became an option, member states seemed to have forgotten the Gaddafi regime’s four-decade-long history as an unpredictable pariah regime with a well-documented record of human rights violations and support of brutal regimes.

Normative power may explain some of the export licensing denials. The denials nevertheless were relatively scarce when compared to what was actually exported, and there was very little interest in establishing a post-embargo toolbox. Indeed, the scrambling for market shares immediately following the embargo upheavals fits uneasily with NPE appropriateness. Our findings underpin the supposition that norms were trumped for the sake of material and strategic benefits, and that the arms trade in practice may be a case of exception to the NPE. The MILANs exported by France, the small arms exported by Belgium, and the Spanish cluster munitions are only a few concrete examples of deals that were problematic under several of the export principles, but that were still pushed through with governmental blessing in order to provide a boost to the exporter’s defence industry. Recalling that the export control regime was seen not only as a direct tool through which to establish a moral order to the arms trade and to enhance security, but also as an indirect tool through which to establish a level playing field that could reduce the competitive disadvantages facing the European arms industry, these findings could suggest that the level playing field rationale underlying the export control regime is very strong, at the expense of the moral and security rationales. This would be at odds with a framing of the export control regime as a tool through which to purely promote a “responsible”_ arms export. Indeed, the occasional denials only serve to demonstrate that exports took place notwithstanding awareness that the export was not unproblematic towards the background of the licensing criteria.

The arming of Libya is a stunning case because it took place at the same time as the EU was promoting democracy in Libya (Martinez Citation2008) and increasing commitment to arms export control both at home and abroad. Paradoxically, the events in Libya generated questions similar to those that came to influence the formation of the export control regime in the first place, and history seemed to repeat itself. A notable difference, though, is that an export control regime was in place and was directed at preventing transfers to dubious actors. The case of EU arms sales to Libya is therefore a testimony that the precautionary moral underlying the arms export control regime may not be sufficient to outweigh material temptations. This, ultimately, has grave consequences for the credibility of the export control regime and the normative power of the EU.

Notes on contributors

Susanne Therese Hansen has a background in international relations and is a Ph.D. research fellow at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, where she conducts research on compliance with conventional arms export control regimes, focusing on the European Union.

Nicholas Marsh is a research fellow at the Peace Research Institute Oslo where he has worked on the arms trade since 2001. He runs the NISAT database project, which tracks the international trade in small arms and light weapons. He has done extensive research on armaments related issues, particularly on the link between acquisition and conflict, and has participated in several multilateral conferences on the arms trade.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Halvard Buhaug, Sibylle Bauer, Espen Moe, and Jørgen Jensehaugen and an anonymous reviewer for comments on drafts of this paper. The authors would also like to thank the Flemish Peace Institute for organizing a seminar on armaments issues concerning Libya in 2012. Previous versions of the article were presented at the Jan Tinbergen Peace Science Conference, Berlin, June 2012, and at the Annual Convention of the International Studies Association, San Francisco, April 2013. All mistakes remain the responsibility of the authors.

Notes

1. A “denial” refers to the non-approval of an export licence application.

2. This process was parallel to the intergovernmental conference leading to the Maastricht Treaty and the adoption of the EU and the CFSP.

3. There is a hierarchy in the criteria in that criteria 1–4 are automatic triggers for denial while criteria 5–8 have merely to be taken into account or considered, and thus need not result in a rejection of a licence application. This is reflected in the wording of the texts of the CoC and the CP.

4. The Treaty of Lisbon has since then altered the language – instead of adopting “common positions” and “joint actions” the Council now adopts “decisions” on positions and actions (Article 29 TEU). The legal nature of common positions adopted in the pre-Lisbon period remains unaltered.

5. For accounts on how the mechanisms of socialization perform within the EU, see for instance International Organization, volume 59, issue 4, 2005.

6. For the UN embargo, see UN Security Council Resolution 731 (1992). The UN arms embargo had already been suspended but not lifted in April 1999, since the Gaddafi regime had accommodated some of the key requirements for lifting the embargo.

7. For the EU embargo, see the Statement by Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the Twelve on International Terrorism and the Crisis in the Mediterranean, European Political Cooperation Presidency, 14 April 1986.

8. Criterion 1 concerns respect for the international obligations, in particular UN sanctions. This was not relevant after the UN embargo was lifted. Criterion 3 concerns the existence of armed conflict within a country, and this was excluded as Libya did not experience civil war until 2011. Criterion 8 concerns the financial and technical capacity of Libya to purchase the equipment. As an oil-rich middle-income state, Libya was deemed not to be of particular concern.

9. Information from annual human rights reports published by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and the US State Department.

10. Denials notifications to COARM are included in a confidential database.

11. Data from the UK Department of Business, Innovation and Skills Strategic Export Controls database. Downloaded from https://www.exportcontroldb.bis.gov.uk/sdb/fox/sdb/SDBHOME 3 June 2014.

12. The EU annual reports contain information only on the exports of equipment listed in the Common Military List. However, this list has a very broad coverage.

References

- Amnesty International, 2010. Killer facts: the impact of the irresponsible arms trade on lives, tights and livelihoods. London: Amnesty International.

- Amnesty International, 2011. Arms transfers to the Middle East and North Africa. Lessons for an effective arms trade treaty. London: Amnesty International.

- Anthony, I. and Bauer, S., 2005. Transfer controls. In: SIPRI yearbook 2005. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 699–719.

- Bauer, S., 2003. The Europeanisation of arms export practices and its impact on democratic accountability. Thesis (PhD). Université Libre de Bruxelles and Freie Universität Berlin.

- Bennhold, K., 2005. France looks for deals with Libya's military. New York Times, 7 Feb.

- Blanchard, C. and Zanotti, J., 2011. Libya: background and U.S. relations. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

- Bromley, M., 2012. The review of the EU common position on arms exports: prospects for strengthened controls. Non-proliferation papers, no. 7. Brussels: EU Non-Proliferation Consortium.

- Bull, H., 1982. Civilian power Europe: a contradiction in terms? Journal of common market studies, 12 (2), 146–164.

- Chivers, C., 2011a. Qaddafi troops fire cluster bombs into civilian areas. New York Times, 15 Apr.

- Chivers, C., 2011b. Following up, part 2. Down the rabbit hole: arms exports and Qaddafi’s cluster bombs. New York Times [online]. Available from: http://atwar.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/06/22/following-up-part-ii-down-the-rabbit-hole-arms-exports-and-qaddafis-cluster-bombs/ [Accessed 7 July 2013].

- Cornish, P., 1995. The arms trade and Europe. London: The Royal Institute of International Affairs.

- Council of the European Union, 1998. European Union code of conduct on arms exports. Brussels: Council of the European Union.

- Council of the European Union, 2008. Council common position 2008/944/CFSP of 8 December 2008 defining common rules governing control of exports of military technology and equipment. Brussels: Council of the European Union.

- Council of the European Union, 2009. User's guide to council common position 2008/944/CFSP defining common rules governing the control of exports of military technology and equipment. Brussels: Council of the European Union.

- Davis, I., 2002. The regulation of arms and dual-use exports. Germany, Sweden and the UK. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Doward, J., 2011. British gun dealer investigated in US over AK-47 empire. The Guardian, 20 Feb.

- Duchêne, F., 1972. Europe’s role in world peace. In: R. Mayne, ed. Europe tomorrow: sixteen Europeans look ahead. London: Fontana.

- Duchêne, F., 1973. The European community and the uncertainties of interdependence. In: M. Kohnstamm and W. Hager, eds. A nation writ large? Foreign-policy problems before the European community. London: Macmillan, 32–47.

- European Commission, 2001. Small arms and light weapons. The response of the European Union. Luxembourg: European Commission.

- European Commission, 2009. Concept note Libya [online]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/world/enp/mid_term_review/final_concept_note_libya_en.pdf [Accessed 3 December 2013].

- Erickson, J.L., 2013. Market imperative meets normative power: human rights and European arms transfer policy. European journal of international relations, 19 (2), 209–234. 10.1177/1354066111415883

- Forsberg, T. and Herd, G.P., 2005. The EU, human rights, and the Russo-Chechen conflict. Political science quarterly, 120 (3), 455–478. 10.1002/j.1538-165X.2005.tb00554.x

- Garcia D., 2011. Disarmament diplomacy and human security. Regimes, norms and moral progress in international relations. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Germany, 2009. Bericht der Bundesregierung über ihre Exportpolitik für konventionelle Rüstungsgüter im Jahre 2008 [Report of the Federal Government over its export policy for conventional military equipment in 2008]. Berlin: Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie.

- Gibney, M., Cornett, L., Wood, R., and Haschke, P., 2013. Political terror scale 1976–2012. Available from: http://www.politicalterrorscale.org/ [Accessed 3 June 2014].

- Gleditsch, K.S., 2013. Modified Polity P4 and P4D Data, Version 4.0., Available from: http://privatewww.essex.ac.uk/∼ksg/Polity.html [Accessed 3 June 2014].

- Guardian, 2011. UK firm defends Libya military sales. The Guardian, 21 Feb.

- Guisnel, J., 2011. Kadhafi, un client de choix pour les armes françaises [Gaddafi, a client of choice for French arms]. Le Point, 22 Feb.

- Holm, K., 2006. Europeanising export controls: the impact of the European Union code of conduct on arms exports in Belgium, Germany and Italy. European security, 15 (2), 213–234. 10.1080/09662830600903793

- Holtom, P., Bromley, M., and Wezeman, P.D., 2008. International arms transfers. In: SIPRI yearbook 2008. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 293–333.

- Holtom, P., et al., 2010. International arms transfers. In: SIPRI yearbook 2010. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 285–329.

- House of Commons, 2011. Scrutiny of arms export controls (2011): UK strategic export controls annual report 2009, quarterly reports for 2010, licensing policy and review of export control legislation. First Joint Report of Session 2010–2011.

- Hyde-Price, A., 2006. ‘Normative’ power Europe: a realist critique. Journal of European public policy, 13 (2), 217–234. 10.1080/13501760500451634

- Hyde-Price, A., 2008. A ‘tragic actor’? A realist perspective on ‘ethical power Europe’. International affairs, 84 (1), 29–44. 10.1111/j.1468-2346.2008.00687.x

- International Defence Review, 2007. ‘Libya contracts Alenia Aermacchi to overhaul trainer aircraft.’ International Defence Review, 6 Aug.

- Jackson, S., 2013. Key developments in the main arms-producing countries, 2011–2012. In: SIPRI yearbook 2013. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 205–217.

- Jane’s Defence Industry, 2007. ‘Dassault reveals Rafale talks with Libya.’ Jane’s Defence Industry, 31 Aug.

- Jane's Defence Industry, 2008. GDUK confirms Libyan communications deal. Jane's Defence Industry, 9 May.

- Jane's Defence Weekly, 2006. Finmeccanica establishes joint venture in Libya. Jane's Defence Weekly, 20 Jan.

- Jane's Defence Weekly, 2007. France agrees Libyan arms sale. Jane’s Defence Weekly, 6 Aug.

- Kagan, R., 2003. Of paradise and power. America and Europe in the new world order. New York, NY: Knopf.

- King, T., 1999. Human rights in European foreign policy: success or failure for post-modern diplomacy? European journal of international law, 10 (2), 313–337. 10.1093/ejil/10.2.313

- Krasner, S., 1999. Sovereignty: organized hypocrisy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Lazarevic, J., 2012. Point by point trends in transparency. In: Glenn McDonald, et al., eds. Small arms survey 2012. Moving targets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 282–311.

- Lustgarten, L., 2013. The European Union, the member states and the arms trade: a study in law and policy. European law review, 4, 521–541.

- Lutterbeck, D., 2009. Arming Libya: transfers of conventional weapons past and present. Contemporary security policy, 30 (3), 505–528. 10.1080/13523260903327451

- Manners, I., 2002. Normative power Europe: a contradiction in terms? Journal of common market studies, 40 (2), 235–258. 10.1111/1468-5965.00353

- Manners, I., 2008. The normative ethics of the European Union. International affairs, 84 (1), 45–60. 10.1111/j.1468-2346.2008.00688.x

- Marsh, N., 2007. Conflict specific capital: the role of weapons acquisition in civil war. International studies perspectives, 8 (1), 54–72. 10.1111/j.1528-3585.2007.00269.x

- Martinez, L., 2008. European Union’s exportation of democratic norms. The case of North Africa. In: Z. Laïdi, ed. EU foreign policy in a globalized world. Normative power and social preferences. London: Routledge, 118–133.

- Mearsheimer, J.J., 1994. The false promise of international institutions. International security, 19 (3), 5–49. 10.2307/2539078

- Menon, A., Nicolaïdis, K., and Walsh, J., 2004. In defence of Europe – a response to Kagan. Journal of European affairs, 2 (3), 5–14.

- Mines Action Canada, 2011. Cluster munition monitor 2011. Ottawa: Mines Action Canada.

- Rettman, A., 2011. Italy-Libya arms deal shows weakness of EU code. EUObserver. Available from: http://euobserver.com/news/31915 [Accessed 3 June 2014].

- Rosso, R. and Dessey, O., 2007. Des Rafale à la Libye... si Washington le veut. L’Express, 14 Dec.

- Scheipers, S. and Siccurelli, D., 2007. Normative power Europe: a credible Utopia? Journal of common market studies, 45 (2), 435–457. 10.1111/j.1468-5965.2007.00717.x

- Sierra Leone Truth & Reconciliation Commission, 2004. Report of the Sierra Leone truth & reconciliation commission. Volume 3B.

- Solomon, H. and Swart, G., 2005. Libya’s foreign policy in flux. African affairs, 104 (416), 469–492. 10.1093/afraf/adi006

- Spleeters, D., 2012. Profit and proliferation: a special report on Belgian arms in the Arab uprising, part I. New York Times [online]. Available from: http://atwar.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/04/05/profit-and-proliferation-a-special-report-on-belgian-arms-in-the-arab-uprising-part-i/?smid=tw-nytimesatwar&seid=auto [Accessed 5 May 2012].

- Sturman, K., 2003. The rise of Libya as a regional player. African security review, 12 (2), 109–112. 10.1080/10246029.2003.9627226

- Takeyh, R., 2001. ‘The rogue who came in from the cold’. Foreign affairs 80 (3), 62–72. 10.2307/20050151

- Telegraph, 2011. How Britain courted, armed and trained a Libyan Monster. The Telegraph, 25 Sep.

- United Kingdom, 2008a. United Kingdom strategic export controls export licence decisions during 2007 by country of destination. London: Department for Business Innovation and Skills.

- United Kingdom, 2008b. Strategic export controls country pivot report 1st October 2008 – 31st Dec 2008. London: Department for Business Innovation and Skills.

- United Kingdom, 2009. United Kingdom strategic export controls annual report 2008. London: Department for Business Innovation and Skills.

- United States, 2008. Country reports on terrorism 2007. Washington, DC: Bureau of Counterterrorism.

- UNSC, 2003. Report of the Panel of Experts appointed pursuant to paragraph 25 of Security Council resolution 1478 (2003) concerning Liberia. S/2003/397.

- Waltz, K., 1979. Theory of international politics. New York: Random House.

- Wezeman, P.D., 2011. Libya: lessons in controlling the arms trade. Available from: http://www.sipri.org/media/newsletter/essay/march11 [Accessed 3 Dec 2013].

- Youngs, R., 2004. Normative dynamics and strategic interests in the EU’s external identity’. Journal of common market studies, 42 (2), 415–435. 10.1111/j.1468-5965.2004.00494.x