ABSTRACT

National approaches to prevent terrorism, extremism, and radicalisation have changed considerably over the last decades. Previous studies mapping these changes have primarily relied on empirical analyses of formal policy and political processes. This case-study of Sweden takes an alternative route, and analyses a dataset of 1405 Swedish newspaper articles (1985–2019) using a new institutional theory and social movement theory framework. Therethrough, the paper is able to provide new insights into the emergence and development of an institutional issue field concerned with the prevention of terrorism, extremism, and radicalisation. More specifically, the paper highlights the unstable, fragmented, dynamic and contested character of the field’s development. Frames containing the problems and solutions considered most important during each of the field’s five stages are identified, and the subsequent institutional and organisational consequences are discussed. The paper also considers how terror attacks and other extremism-related events impact the institutionalisation and alternation of dominant frames, and identifies the translation and development of an inclusive vocabulary as pivotal to mobilising a broad and diverse set of actors to co-produce preventive efforts.

1. Introduction

Over the last decades, the prevention of terrorism, extremism, and radicalisation (PTER) has emerged a highly prioritised security and social challenge for European states (Balestrini Citation2020). PTER has traditionally been considered a responsibility for organisational actors from the societal security field (e.g. the intelligence, military, and police services). However, most contemporary national policies have adopted a “whole-society approach” in which such actors are complemented by, and encouraged to collaborate with, social welfare actors (e.g. schools, social services, youth centres, integration units, and civil society organisations; Sivenbring and Andersson Malmros Citation2019). Typically, the “soft side” of counter-terrorism gathers its objectives and measures under the policy banners “Preventing Violent Extremism” (PVE) or “Countering Violent Extremism” (CVE) (Herz Citation2016). Consequently, PTER represents a policy issue exposed to considerable changes. Research mapping changes of contemporary counter-terrorism and PVE/CVE approaches have primarily relied on empirical analyses of formal policy and political processes (e.g. Nohrstedt and Hansén Citation2010, Bossong Citation2012, Strandh and Eklund Citation2015, Malkki Citation2016). While this stream of research brings valuable insights, it often fails to properly address important factors and processes of change located outside the formal political arena.

On the subject of change, terror attacks and other extremism-related events (TEEs) are identified as central (e.g. Birkland Citation2004, Argomaniz Citation2009, Hassan Citation2010, Spencer Citation2010, Citation2012, Brinson and Stohl Citation2012, Smith et al. Citation2019). For example, Hassan (Citation2010) notices the development of the European Union’s counter-terrorism strategy being “dynamic and diverse, arising as a response to crises and evolving over time” (p. 445). Other literature highlights how TEEs provide elite actors with windows of opportunities to impose their versions on how PTER is to be organised (Crenshaw Citation2001, Birkland Citation2004, Hassan Citation2010). With this literature in consideration, TEEs are, however, typically threated as “context” and located at the background section of most papers concerned with PTER, with connections to change only being hinted or taken-for-granted (e.g. Lindekilde Citation2012, Harris-Hogan et al. Citation2016, Sivenbring and Andersson Malmros Citation2019). Furthermore, the literature on TEEs generally conveys a binary understanding of how such events matters: attacks and events are portrayed as either disruptive or not, and scholarly attention is almost exclusively directed towards attacks that trigger change (e.g. Birkland Citation2004, Argomaniz Citation2009, Hassan Citation2010), while other non-disruptive events are largely overlooked, both empirically and theoretically.

To provide new insights into the development of PTER efforts in Europe, the paper aims to discern how PTER has been framed and constructed in media over time, and analyse how dominant frames are impacted by TEEs. To achieve this, the paper uses a case-study design focusing the emergence and development of an institutional issue field (Hoffman Citation1999) concerned with PTER in Sweden. Sweden makes for an intriguing case to explore how PTER efforts have developed. The country has a long and violent history of right-wing extremism (Mattsson and Johansson Citation2019), has among the world’s highest per capita numbers of foreign fighters in Syria/Iraq (Gustafsson and Ranstorp Citation2017), and has, similar to many of its European neighbours, launched extensive public efforts to prevent violent extremism in the twenty-first century (Andersson Malmros and Mattsson Citation2017). A dataset of 1405 Swedish newspaper articles (1985–2019) is analysed using a new institutional theory and social movement theory framework. The paper provides an in-depth, contextualised, discursive, and institutional perspective on development and change, and demonstrates the multiple effects of TEEs on field processes. Furthermore, the analysis highlights how the institutionalisation of specific meaning structures in media is related to major changes in public efforts to PTER, and discusses how the introduction and development of a new vocabulary impacted the field. Consequently, the theoretical and methodological approach of the paper does not only provide new insights into field development and change, but also offer context and explanatory power to political decision-making on the subject. While previous research indicates dominant media constructions to have an impact on the political arena (Spencer Citation2012), the institutional analysis offered here refines present understandings of how and why.

The following two sections present the paper’s theoretical framework and how they shape the paper’s analysis, followed by an explanation of the study’s data and methods. The subsequent “Findings” section is divided into five parts: “Field emergence, 1999–2001”, “Field expansion, 2002–2009”, “Field alignment, 2010–2013”, “Field mobilisation, 2014–2016”, and “Field juridification, 2017–June 2019”. Based on the findings, the paper then more broadly discusses the relationship between TEEs and field processes, ending in a conclusion summarising the paper’s main contributions.

1.1. Issue fields and institutional infrastructure

The paper conceptualises PTER as an institutional issue field. In new institutional theory, the field concept is fundamentally and “vitally connected to the agenda of understanding institutional processes” (Scott Citation2014, p. 219), and most institutional scholars agree that the field is the central construct of organisational life: the social space where the institutions and meanings that guide organisational behaviour are located, debated and developed (Hoffman Citation1999, Scott Citation2014). As scholarly attention turned to institutional change in the 1990s, Hoffman (Citation1999) proposed that fields form around issues (e.g. PTER and the climate crisis) and are “centres of debates in which competing interests negotiate over issue interpretation. As a result, competing institutions may lie within individual populations (or classes of constituencies) that inhabit a field” (p. 351). Because field members come from multiple sectors and have divergent interests, the institutional infrastructure of issue fields is typically fragmented or contested (Hinings et al. Citation2017, Zietsma et al. Citation2017).

The institutional infrastructure of a field is here understood as the “set of institutions” (Hinings et al. Citation2017, p. 169) that guides the field’s processes and governs its interactions, including both cognitive and structural elements. The cognitive elements are the central logics and meaning structures that guide conceptions of what the field is about, and of the actions and identities considered appropriate. Central meaning structures are also manifested in, and by, the structural elements of the infrastructure, for example, the formal and informal governance units (e.g. national coordinators and experts) and the social arenas of interaction (e.g. conferences and professional networks) that facilitate the governance of field processes (Hinings et al. Citation2017, Zietsma et al. Citation2017). Depending on how elaborated the infrastructure is, Hinings et al. (Citation2017) distinguished between four field conditions: established, contested, aligned, and fragmented. Established fields have a highly institutionalised infrastructure with formal and informal governance elements, and shared conceptions of what the field is about and what beliefs and actions are considered appropriate. In cases in which the field conditions can be considered contested, the institutional infrastructure is elaborated but is inhabited by actors with clearly competing conceptions of the meanings that should dominate the field. In aligned fields, actors share common ideas about the field, but the structural elements of the institutional infrastructure are not particularly elaborated. Finally, in fragmented issue fields, the institutional infrastructure is weakly elaborated and members are guided by diverse conceptions of what the field is about and of what is considered legitimate behaviour. Members of issue fields will exploit contested and fragmented conditions and “can be expected to propose and seek to mobilise consensus around a particular conception” (Fligstein and McAdam Citation2012, p. 10), struggling with one another to shape meaning (Meyer and Höllerer Citation2010).

Conditions in fields are not static but develop in a nonlinear fashion. For example, a field can develop from a contested condition into an aligning or established one, before reverting to its previous state or entering a new one (Zietsma et al. Citation2017). Often, such changes are triggered by critical events that, for example, allow new actors to enter the field (Hoffman Citation1999) or new governmental policies and structures to form (Nigam and Ocasio Citation2010).

1.2. Critical events and frames

The emergence or change of fields is often prompted by exogenous shocks (Fligstein and McAdam Citation2012, Zietsma et al. Citation2017), disruptive events (Hoffman Citation1999), environmental jolts (Meyer Citation1982), or, as used here, critical events (Pride Citation1995). In line with a social constructivist understanding of how events become disruptive (see also Hoffman Citation1999, Hoffman and Ocasio Citation2001, Munir Citation2005), social movement scholar Pride (Citation1995) highlighted how the primary impact of critical events is that they direct public attention towards social issues that can be connected to them (see also Crenshaw Citation2001). Defined as “contextually dramatic happenings” (Pride Citation1995, p. 5), critical events represent “radical discontinuities in the real world that attract attention” (p. 6), for example, environmental disasters, epidemics/pandemics, ground-breaking technical or medical innovations, economic depressions, wars, major changes in public policy, and terror attacks. Actors with an interest in these issues will compete over issue and event interpretation and, depending on the outcome of this competition, critical events may have redefining or re-establishing effects on field change. Event redefinition results in radical shifts in “public and elite perceptions of reality” (Pride Citation1995, p. 7), while event re-establishment results in intense conflict, but with no substantial change in perceptions of reality noted as an outcome. Hence, a central idea in Pride’s (Citation1995) work is that events themselves are not inherently redefining, but become so.

Therefore, meaning construction is central to understanding the impact of events on fields. Such construction is enacted through framing: communicative action that shapes the frames that serve as “schemata of interpretation” (Goffman Citation1974, p. 21) and help actors understand and allocate meaning to occurrences in their social life and in the world (Gamson and Modigliani Citation1989). Frames also help actors locate and identify problems and possible solutions (Snow and Benford Citation1988). Here, Snow and Benford (Citation1988) distinguished between diagnostic framing (“the identification of a problem and the attribution of blame”, p. 200) and prognostic framing (“a proposed solution to the diagnosed problem that specifies what needs to be done”, p. 199). Some frames, if scaled up and widely shared among field members, will gain a hegemonic and potentially institutionalised status. Lounsbury et al. (Citation2003) conceptualised such “master frames” as field frames. A field frame is an element of discourse that has “the durability and stickiness of an institutional logic, but akin to strategic framing, it is endogenous to field actors and is subject to change and modification” (Lounsbury et al. Citation2003, p. 72). Once formed, a field frame confers a dominant order on meaning systems in a field, constituting the appropriate way to think and act concerning a particular issue at a given time and place.

To put this framework in relation to my study, I situate the PTER field as an institutional issue field, characterised by active struggles over meaning between actors from multiple fields. Such meanings are gathered and communicated through framing activities in which problems are identified, solutions proposed, and accountability assigned. Some frames become hegemonic and evolve into field frames, here understood as the cognitive elements of the field’s infrastructure, which become constitutive for the involved actors’ perceptions and actions. Critical events, such as terror attacks, are understood as catalysts of change in the field, as they provide openings for alternative frames to gain support.

2. Methodology

The data analysed comprise 1405 newspaper articles collected from seven of the biggest newspapers and news agencies in Sweden. The use of newspaper articles is common in research on issue fields (Hoffman Citation1999, Meyer and Höllerer Citation2010), as data from mainstream media are suitable for tracking and understanding the historical development of such fields (Grodal Citation2007, Meyer and Höllerer Citation2010). Also, this data source constitutes “a structured social space” (Meyer and Höllerer Citation2010, p. 1245) for mobilising the legitimacy of specific constructions of social reality and “reflects the available framings and brings to light actors’ efforts to elicit support for their claims” (Meyer and Höllerer Citation2010, p. 1245). Using newspaper articles to track field-level changes also harmonises with previous findings in counter-terrorism studies, where the media has been identified as an important arena for actors interested in affecting policy processes and responses to terrorism (Crenshaw Citation2001, Spencer Citation2010).

The newspaper articles were collected through Mediearkivet (The media archive; author’s translation), an online archive of various forms of media output in Sweden. In line with my analytical emphasis on framing, I concentrated on opinion-oriented articles (e.g. debate articles, personal stories, opinion pieces, and editorials) from six of Sweden’s largest newspapers: Aftonbladet, Dagens Nyheter, Expressen, Göteborgs-Posten, Svenska Dagbladet, and Sydsvenskan. Arguably, the spaces for opinion-making in these newspapers constitute a concentrated and central space for framing activities. However, frames are also present in regular news reporting, and the TEE that become news reflect the topics considered relevant at a given time and place. Therefore, regular news reports from the biggest news agency in Sweden (Tidningarnas Telegrambyrå) were also included in the material.

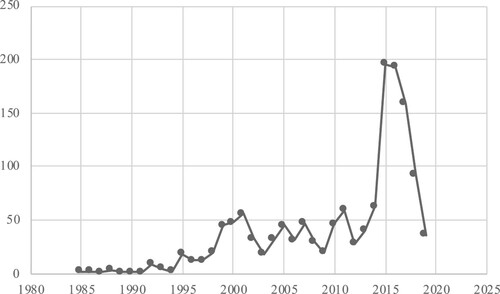

To collect articles addressing the PTER field, I conducted broad searches in Mediearkivet. In these, the most central terms associated with “prevention” (e.g. counter*, prevent*) were combined with terms associated with different forms of extremism (e.g. nazi*, jihad*) or the phenomenon in general (e.g. radicali*, extremi*, terror*). The list of search words was continuously refined during the data collection as my awareness of key terms grew. Appendix 1 contains the complete list of search words. These searches identified 11,497 unique articles. For every hit, I screened the title and read the sentences that included the search words to learn whether the article met the inclusion criteria: (1) type of article (i.e. opinion-oriented texts in newspapers and news reports from Tidningarnas Telegrambyrå), (2) articles concerning TEE in Sweden, and (3) articles concerning PTER. This step was followed by a full reading of the identified articles to ensure their validity before further analysis. This process resulted in a database of 968 opinion-oriented texts and 437 news agency reports (1405 articles in total) published from 1985 to June 2019 (mean 40.25 per year, median 29 per year). The opinion-oriented articles were relatively evenly distributed among Aftonbladet (n = 167), Dagens Nyheter (n = 175), Expressen (n = 131), Göteborgs-Posten (n = 195), Svenska Dagbladet (n = 167), and Sydsvenskan (n = 133) ().

The selection of data sources entails limitations. Mediearkivet gathers articles from 1982 onwards, excluding material before this date. However, this would likely not affect the findings, as I have identified 1999 as the year of field emergence. It is hard to set an exact starting date for any institutional field (Grodal Citation2007), the PTER field being no exception. The choice of 1999 relates to the paper’s theoretical focus on issue fields, as 1999 was the first year when PTER was consistently and frequently recognised in the media (i.e. a minimum of 20 articles/year). Another important limitation in the paper concerns translation of quotes from Swedish to English. In such processes, important nuances risk being lost, which, to some degree, can alter the meaning of the original quote and thereby impact the findings.

Following this step, all media articles were subject to content analysis, a method in the intersection between qualitative and quantitative methods (Duriau et al. Citation2007). Content analysis is particularly suitable for studying change over time (Duriau et al. Citation2007), in keeping with the purpose of this paper. Inspired by Suddaby and Greenwood (Citation2005), I conducted a two-level analysis of the data. The first level was quantitative and used a textual analysis of the manifest content of all articles, focusing on three categories: (1) the actors/sectors in focus (e.g. schools, teachers, social services, social workers, and police), (2) the problems and issues of interest (e.g. radicalisation, terrorism, extremism, militant Islamism, and right-wing extremism), and (3) the main events reported (e.g. 9/11, Stockholm 2010, and Oslo 2011). The hits were then cross-checked to validate their inclusion in each category.

When developing the word strings coupled to each category (see Appendix 2), I drew on Suddaby and Greenwood’s (Citation2005) description of institutional vocabularies as “structures of words, expressions, and meanings used to articulate a particular logic or means of interpreting reality” (p. 43). Put differently, words are connected to certain meanings, and the analysis of how often and when certain words occur helps in mapping field development. The same rationale was applied to TEEs: knowledge of the frequency and intensity of reported and discussed events helps us understand what types of events matter for the field at what time.

In the second level of the analysis, I was interested in the latent content of the media articles. This required an interpretive approach, assisted by a discourse analysis applied to all debate articles (n = 136) in Dagens Nyheter and Aftonbladet, the two newspapers with the most readers in Sweden. Here, discourse refers to an interrelated body of texts (i.e. the debate articles), constituted by words, speech, abstractions, notions, concepts, labels, and categorisations, expressing and assembling the meanings central to a field (Maguire and Hardy Citation2009). Accordingly, the discourse analysis aimed to discern the dominant meaning structures (i.e. field frames) in the analysed material. When a field frame is replaced or altered, it implies a change of discourse, a new way of “talking about a topic and … a particular kind of knowledge about a topic” (du Gay Citation1996, p. 43). I read the articles in full and, building on my theoretical framework, coded and analysed the material in relation to the following categories: (a) prognostic framing, (b) diagnostic framing, (c) conflicts over meaning and values, (d) actors and their subject positions, and (e) the interpretation and construction of events. Building on insights from this analysis, the condition of each identified stage of the field was categorised as either aligned, fragmented, contested or established (Hinings et al. Citation2017).

To provide readers with a processual view of field development, the findings are presented as a chronological narrative in sections reflecting the five identified stages, with a shift of stage representing a considerable change in the field frame.

3. Findings

3.1 Field emergence, 1999–2001

Three important but qualitatively different events were central in directing intensified interest towards the PTER field. In 1999, two lethal attacksFootnote1by neo-Nazis increased already growing national attention to right-wing extremism. The overall prognostic framing of these events and the issue of right-wing extremism suggested that the growth of this milieu should be prevented by increasing education about historical Nazism, the Holocaust, racism, and human rights. Following this, the government launched several national initiatives to improve the knowledge of right-wing extremism in society, most prominently in schools.

The surge of right-wing extremism was portrayed as a youth problem, with its roots in social problems, misguidance in life, and deficient knowledge. Right-wing extremists were viewed as objects rather than subjects and, in a sense, as victims of alienation, defective environments, and poor upbringing. This framing of the issue was aligned with the second general prognostic framing, which suggested that right-wing extremists should be handled with “soft measures” (Herz Citation2016). Dialogue and relationship-building were central tools in efforts both to prevent at-risk youth from getting involved in right-wing extremism and to assist those ready to leave the milieu. The use of soft measures to prevent right-wing extremism was criticised by those calling for harsher measures. This criticism most prominently targeted the legal sector, calling for more stringent laws to disrupt and prohibit neo-Nazi propaganda, especially white-power music and magazines. In turn, this provoked debate around democratic rights in general and freedom of speech in particular, and about how these rights should apply to neo-Nazis.

In 2001, two more events occurred that left a significant mark on the field. In June 2001, the city of Gothenburg hosted an international meeting attended by U.S. President George W. Bush and other government leaders. The meeting resulted in violent clashes between police and demonstrators, many of whom were connected to left-wing extremist movements. The ensuing debate centred not on how to prevent people from engaging in left-wing violence, but rather on how the event could have been better handled by police and prevented from escalating. This framing diverged markedly from that related to right-wing extremism, which centred on social efforts to prevent young people’s engagement. The other event, the combined terror attacks against the USA. on September 11 (9/11), is often considered the starting point of most historically oriented research on PTER.

Taken together, there is a clear before and after 9/11: before, the PTER field had emerged with a relatively shared conception of how to fight right-wing extremism; after, societal security actors entered the field and it became highly fragmented, guided by diverse logics and belonging to different infrastructures.

3.2. Field expansion, 2002–2009

The massive attention to the events of 9/11 resulted most directly in an expansion of the PTER field. Before 9/11, there is not a single mention in the studied newspapers of militant Islamism as an issue meriting preventive efforts in Sweden. From being almost exclusively centred on domestic political extremism and the use of soft measures by educational services, the field became dominated in this stage by an emphasis on international terrorism perpetrated by militant Islamist organisations and the use of surveillance to discover and control them.

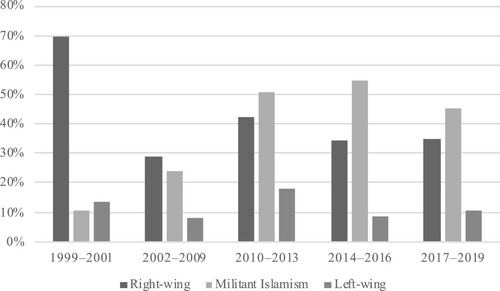

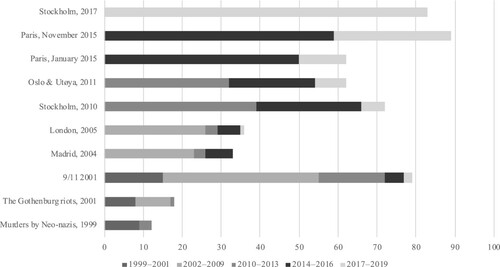

With 9/11 and the later bombings in Madrid and London in 2004 and 2005, militant Islamism, along with right-wing extremism, was framed as a central target of PTER efforts in Sweden. Militant Islamism and right-wing extremism are manifested almost equally in the data from this stage, but this balance later shifts as militant Islamism becomes the centre of attention in the field in all later stages ().

The diagnostic framing of the newly emerged threat of “terrorism” (rather than “extremism”, as used for right-wing threats) from militant Islamism did not treat it as a domestic problem, but as a foreign one that threatened Sweden from abroad. As an example of this perception, the Swedish Minister of Justice proposed that Sweden should prevent terrorist attacks by supporting deprived people in the Middle East:

Basically, terrorism, like almost every other crime, depends on social causes. It is therefore important that Sweden continues to work to prevent terrorism from occurring at all … To reduce the suffering in the Middle East, the government has also taken the initiative to organise a donor conference for Lebanon … I am convinced that the main breeding grounds for terrorist organisations are poverty and exclusion. (Bodström Citation2006, p. 30)

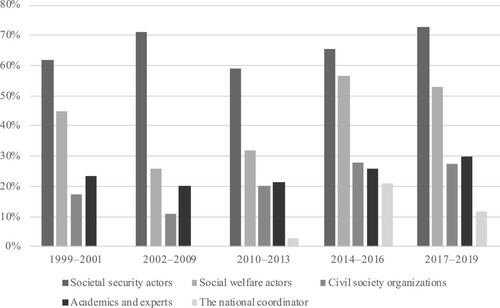

The major conflict at this stage of the field’s development was between the need to protect Sweden and the cost it would inflict on citizens’ privacy. The focus on societal security during this stage effectively led to the dominance of security actors and perspectives. This represented a considerable change from the previous stage, when schools and education played a key role. Educational services continued to matter during this stage, but almost exclusively in countering right-wing extremism.

To sum up, the institutional infrastructure was still highly fragmented. Central events (i.e. the terror attacks in Madrid and London) during this period did not have a redefining impact, but rather a supportive one in relation to already dominant field frames. On the other hand, 9/11 was still heavily debated, becoming an event that now could be considered elusive: actors attached divergent framings to the event, many pointing towards the increased securitisation that had followed.

3.3. Field alignment, 2010–2013

In Stockholm in mid-December 2010, Sweden experienced its first attack by a homegrown terrorist. Only the terrorist died in the suicide bomb attack, but it shifted attention in the field from how Sweden should prevent terrorist attacks from outside its borders, to how to prevent its own citizens from turning to terrorism. Only about two weeks after the attack in Stockholm, Swedish security police arrested four Swedish citizens on their way to carry out an attack on Jyllands-Posten, which had published caricatures of the Prophet Mohammed in 2005.

While the field emergence stage (1999–2001) targeted young people in racist milieus and the field expansion stage (2002–2009) targeted international terrorists, this stage led to a particular interest in young people of Muslim heritage living in Swedish suburbs. More specifically, the diagnostic framing in the field became dominated by the question of why Swedes of Muslim heritage and beliefs would be willing to engage in terrorism:

The general picture of terrorists is still that of young men from the Arab world threatening democratic societies in the Western world. Therefore, many were shocked when they discovered that a suicide bomber may be a young man who had grown up in Europe … I think it may even be easier to recruit suicide bombers in Stockholm’s segregated suburbs than in Muslim countries. (Pekgul Citation2010, p. 42)

The prognostic framing during this stage rebalanced the focus to include the hard measures typical of the field expansion stage (2002–2009) by calling for a combination of hard and soft measures in PTER. The knowledge of radicalisation processes, extremist milieus, and violent ideologies was also identified as central to building societal capacity for PTER. The perceived knowledge and organisational deficits led to a number of policy actions: a national action plan against “violence-affirming extremism”Footnote3 was adopted in 2011 (Swedish Ministry of Culture Citation2011), government-commissioned research was published and distributed (e.g. Ranstorp and Hyllengren Citation2013), and state investigations were initiated. Together, these efforts outlined the first step towards “a whole-society approach” in which societal security actors and social welfare actors were to collaborate in PTER.

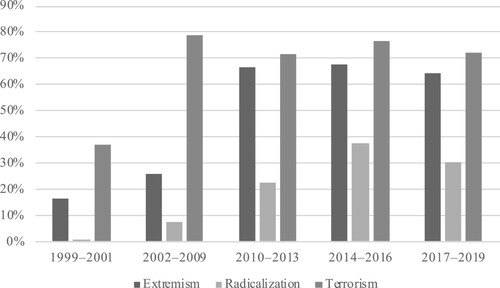

In comparison with previous stages, which were characterised by fragmentation among actors, phenomena, and milieus of focus, this stage saw the field starting to develop a comprehensive discursive and organisational framework for dealing with all issues concerning PTER. This represented a considerable change: militant Islamism, right-wing extremism, and left-wing extremism were to be understood as parts of the same challenge, leading to a less fragmented field and more general, rather than milieu-specific, preventive approaches (for a critique of this approach, see the debate article by Lööw et al. Citation2013). The field began to develop its own vocabulary, characterised by the consistent use of certain concepts and terms, during this stage. The most influential concepts were “radicalisation” and “violence-affirming extremism”, around which theories, policies, and practices emerged and developed. The introduction of the radicalisation concept led to increased media and public interest in and debate on the pathways to politically and religious-motivated violence. This, in turn, led to renewed interest in the work of social welfare actors and soft measures: if there were a defined pathway to extremism and terrorism, perhaps it could be blocked before the threat materialised as violence ().

The previously mentioned focus on young Muslims in Sweden was far from uncontroversial. Many claimed it was based on prejudiced and stereotypical images of Muslims and their beliefs and community in Sweden, while those initiating the discussion spoke of a general reluctance to ask questions about Islam. If the main conflict in the previous stage centred on societal security versus citizens’ right to privacy, this stage came to discuss Islam and Muslims in general and their inclusion in Swedish society in particular.

To sum up, a slightly more elaborated and coherent institutional infrastructure emerged during this stage. Central to this progress was the development of a common vocabulary, which helped link previously fragmented perspectives and actors. Triggering this development were the redefining events in Stockholm in 2010 and Oslo in 2011, and the associated framings erased the previous separation between right-wing extremism and militant Islamic extremism.

3.4. Field mobilisation, 2014–2016

In July 2014, a national coordinator was appointed to safeguard democracy from violent extremism. In turn, the vocabulary established in the previous stage was now materialised in public offices. The appointment coincided with an increased emphasis on foreign fighters travelling to jihadi groups in Syria and Iraq. In 2015 and 2016, this was followed by terror attacks in Paris, Brussels, and Copenhagen. Consequently, media attention to PTER increased. From 2010 to 2014, the number of articles about PTER in the data ranged from 28 to 63 per year; in 2015, that number rose to 196, representing over a three-fold increase in attention to the field. Compared with previous stages, when questions regarding PTER were primarily directed towards politicians, the national coordinator was now perceived as having overall responsibility for preventive work. This led to the national coordinator becoming a crucial actor in framing the issue. Subsequent opportunities for framing emerged in a clear pattern: any global, national, or local terrorist/extremist event was followed by media questions to the national coordinator about what it would mean to Sweden, and what was being done, or needed to be done, to prevent a similar event from happening in Sweden.

The national coordinator, inspired and supported by other elite actors, proposed municipalities to take a leading role in preventive efforts. Rather than highlighting specific sectors of the municipal organisation (as during previous stages), PTER very rapidly became a general municipal responsibility: in the two previous stages, municipalities were mentioned in only 9% of the articles, but in the field mobilisation stage, they were mentioned in 34%.

Swedish municipalities were framed as slow and ineffective in responding to the challenge, and debaters framed the underlying reason as a general reluctance to discuss questions concerning the militant-Islamism milieu. In contrast, Danish municipalities were portrayed as role models for PTER:

For many years, we have seen a great need for better measures in Sweden to prevent people being drawn to radicalisation. In Sweden, these measures are still looming at the discussion stage. This is a late, neglected lesson Swedish municipalities must learn … Copenhagen and Aarhus are far ahead of Swedish municipalities in preventive work … Municipalities must take greater responsibility for developing structured preventive work to find solutions to these problems. (Ranstorp and Hyllengren Citation2015, p. 6)

also shows the increasingly important roles that academics and experts were beginning to play, as debaters, resource people for opinion-makers, and educators for professionals. The expert community also became more diverse in terms of disciplines and perspectives, and new research centres and groups with a specific interest in PTER were established in universities. Academics helped fuel the most important conflict in this stage, which centred on the balance between hard and soft measures in PTER. The roles of social welfare professionals (e.g. teachers and social workers) were especially debated. Critics noted the many problems associated with tasking such professionals with identifying signs of radicalisation and handling them from a security perspective, while actors from the security field noted the need to develop early warning systems to report individuals perceived to be at risk. In April 2017, the character of these framing activities was disrupted by a terror attack in central Stockholm that killed five people. The demographic and legal status of the offender, Rakhmat Akilov, a 39-year-old “illegal” immigrant, became central to the framing activities that followed.

Taken together, this period saw the forming of a more elaborated institutional infrastructure strengthened by new governmental policies and actors. However, the field remained contested, as different perspectives on how to implement PTER dominated the debate. The two terror attacks in Paris in 2015 attracted massive public attention, but the framings did not alter the direction of the field; instead, they had a supportive impact on established field frames.

3.5. Field juridification, 2017–June 2019

After the terror attack in Stockholm in April 2017, the diagnostic and prognostic framings were heavily influenced by the fact that the perpetrator was not a Swedish citizen. Akilov had come to Sweden in 2014 as an asylum seeker, received an expulsion decision in January 2017, but had remained in Sweden. Hence, little in the framing perspectives of the previous stage fit his profile, since it was unlikely that early prevention efforts by municipalities or other social welfare actors could have prevented the attack. Therefore, responses to the attack came to resemble those during the field expansion stage (2002–2009), explicitly stressing the role and work of societal security actors and debate about new laws and more extensive surveillance tools. In two respects, however, these responses clearly differed from those of 2002–2009.

Swedish migration policy came under scrutiny as an important facilitator of the attack, and undocumented immigrants were identified as a new group at risk of committing terror offences. Also, the April 2017 attack coincided and was partly aligned with increasing attention to the return of Swedish foreign fighters and their families from the war in Syria and Iraq. As they returned, the problems of charging them with crimes they might have committed became obvious and heavily discussed in the media.

The key framings in this stage concentrated on the Islamist milieu, the need for more resources for the security police, and new laws and regulations to help societal security actors discharge their PTER tasks. However, the framings also newly considered the role of civil society organisations (CSOs). During the initial stages of the field (1999–2013), CSOs were predominantly framed as actors that could help with PTER, but during the field mobilisation stage (2014–2016), their role was questioned as several debaters suggested that they were part of the problem, rather than the solution. Such claims, grounded in accusations that extremist and/or undemocratic messages were promoted mainly by Muslim organisations that had received public grants for their operations, increased in this latest stage.

Along with the conflict about whether CSOs were part of the solution or the problem, a similar conflict about democratic rights recurred. As in the field expansion stage (2002–2009), proposals for tougher laws and surveillance were met with some scepticism, but the arguments were more subtle than before. Proposals often encountered general but hesitant agreement, with a warning about how the measures could affect the democratic rights of citizens. In particular, the right to association shifted from being an almost non-existent topic in previous stages to a central topic in current discussions. This debate was mainly ignited after proposals to criminalise association with terrorist and violent extremist organisations (e.g. the Nordic Resistance Movement). Critics argued that removing the absolute right to organise would constitute an intrusion on the democratic rights of Swedes, while those supporting the proposal argued that freedom of association was never meant to encompass the organisation of those who threaten to overthrow democratic rule.

To sum up, the field returned to a more fragmented condition, with a strong focus on societal security actors and legal actions against terrorists and extremists. Previous lines of conflict seemed to enter a state of ceasefire (cf. Meyer and Höllerer Citation2010), with the differences in perspective remaining, although less vocally expressed.

4. Discussion

In the following discussion, I consider two themes and discuss how they relate to the field’s development: the multiple effects of critical events, and new vocabulary as a key factor to the elaboration of the field’s infrastructure.

4.1. The multiple effects of critical events on field processes

Here, I discuss how TEEs, even when not triggering change, can significantly affect field-level processes. This is not to suggest that events “do” anything on their own; rather, they rely on actors with certain interests, i.e. “sponsors” of frames (Munir Citation2005), to become relevant. The section builds on Pride’s (Citation1995) framework on critical events, but expands it by identifying three types of TEEs: redefining, supportive, and contentious events.

Redefining events echo Pride’s (Citation1995) original category, and are the events most similar to Hoffman’s (Citation1999) popular notion of events that are disruptive in their impact. Most of the frames highlighted here existed before a given TEE, but the event produced opportunities for actors to (re)introduce existing frames that diverge from the temporarily dominant field frames. The redefining events identified here are often the subject of massive social attention, and thereby function as both scene and spotlight – platform and focus – to bring certain frames to field members’ attention. The terror attacks of 9/11 in New York and of 2010 in Stockholm are both examples of redefining events, after which the field changed direction and focus. Consequently, for an event to have a redefining impact, its associated frames must break from the currently dominant perspectives. Taken together, the present findings strongly support research identifying TEEs as catalysts for change in the PTER field (e.g. Crenshaw Citation2001, Birkland Citation2004, Argomaniz Citation2009, Hassan Citation2010).

Supportive events are critical events that might attract substantial attention, for example, the terror attacks in Madrid in 2004, London in 2005, and Paris in 2015, but do not produce a distinctive change in the overall framing of the field. Instead, these events support established frames, having an institutionalising effect. Put differently, such events elicit “more of the same” reactions from stakeholders, reactions that consolidate, rather than change, frames. Here, sponsors of certain frames use supportive events as examples or evidence to uphold their preferred frames. For example, in several debate articles, the Liberal Party in Sweden framed terrorism as a European issue that should be addressed by establishing a “European FBI”. In response to major terror attacks, Party representatives repeatedly wrote pieces suggesting the formation of a common European police force to effectively address the issue.

Contentious events partly resonate with Pride’s (Citation1995) idea of re-establishing events, but contain more latitude for prolonged conflict between issue field members and improve our understanding of the impact of such events on field processes. Contentious events are aligned with multiple, divergent frames, often leading to considerable conflict over interpretation. A contentious event has characteristics that engage multiple actors and invite several, often conflicting, diagnostic and prognostic framings. Consequently, contentious events can cause long-term polarisation and increased fragmentation of the field and, therefore, have a considerable impact on field processes. For example, the framings after the terror attack in Stockholm in 2010 led to the collision of two conflicting diagnostic frames, one suggesting that the attack was an expression of rising levels of radical Islamic ideology in the Muslim community, and another suggesting that Muslims were the greatest victims of the attack due to the ensuing discrimination. Such conflict can hinder fields from developing from a contested or fragmented condition, to a more elaborated condition with the potential to foster effective actions ().

The findings also indicate that redefining, supportive, and contentious events are dynamic and demarked by porous boundaries such that their classification can shift with time. A redefining event can eventually become a contentious or supportive event, and a contentious event can, after much conflict, become a redefining event as the dust settles and one side emerges as the winner. For example, 9/11 was initially a redefining event, prompting radical change in the view of how to protect society from terrorism. In the next five or so years, 9/11 became a contentious event as debaters began to argue that the government had used 9/11 as an opportunity to circumscribe citizens’ personal integrity and advance state control. After the terror attack in Stockholm in 2010, 9/11 re-emerged in the public debate and was invoked to support calls for more surveillance. Here, Hoffman and Ocasio’s (Citation2001) early suggestion that “events can be retroactively enacted to fit the new social structures” (p. 431) is adequate; TEEs are not static, but can be reframed and re-used for new and old purposes. This is important to consider in relation to the study of impacts of TEEs on PTER, since the way in which TEEs are framed and discursively constructed “makes certain responses appear more appropriate than others” (Spencer Citation2012, p. 410). In the coming section, this observation will be further elaborated.

4.2. Events, vocabulary, and institutional infrastructure

Following the attack in Stockholm in 2010, which was conducted by a Swedish citizen, framing activities centred on understanding and conceptualising pathways to extremism and terrorism: Why did a quiet and seemingly “normal” small-town resident choose to blow himself up in a crowded shopping street in the capital? As portrayed in the findings, radicalisation here emerged as the dominant explanation of the social, ideological, psychological, economic, and cultural drivers underpinning the process leading to people attacking their own country. At the international policy level, the concept of radicalisation had already been incorporated in the discourse on terrorism and extremism (Kundnani Citation2012). However, in Sweden, the extant vocabulary at the time was insufficient to make sense of the events (cf. Nigam and Ocasio Citation2010), effectively leading to the intensified translation and use of the radicalisation concept. This illustrates how critical events can intensify the translation of new vocabulary, in turn helping to rationalise the problems to which events draw attention (Hoffman and Ocasio Citation2001).

An associated example of a new term, emerging at the same time as radicalisation, was the establishment of violence-affirming extremism. This label, originally developed by the Swedish Security Police (Citation2010), grouped all illegal acts (including non-violent ones, such as financing terrorism) and extremist milieus under one label. Previous labels used by the field distinguished between different milieus and phenomena of interest (e.g. right-wing extremism and militant Islamic extremism/terrorism), in turn, affecting what actors were considered responsible for handling what issue. Notably, teachers were instructed to prevent right-wing extremism through education, while the security police and military were tasked with detecting and eliminating threats from militant Islamic terrorism (see “Field expansion, 2002–2009”). Here, the introduction of the concept of violence-affirming extremism resulted in the deconstruction of previous dominant categorisations (i.e. right-wing extremism, left-wing extremism, and militant Islamic terrorism), which were relabelled and reframed in a single category. While combating militant Islamic terrorism felt distant and inappropriate for teachers in Swedish schools, preventing the radicalisation processes leading to militant Islamic extremism was largely coherent with the professional logic guiding their work (Sivenbring and Andersson Malmros Citation2019). These observations also align with previous findings in new institutional theory recognising the translation or development of new labels and vocabulary as “a critical mechanism” (Nigam and Ocasio Citation2010, p. 838) underpinning field-level change (Greenwood et al. Citation2002, Meyer and Höllerer Citation2010).

While emphasising the impact that the introduction of the concepts of radicalisation and violence-affirming extremism had on the cognitive elements of the institutional infrastructure (i.e. the field frames), it also makes sense to briefly review how the structural elements were affected (Hinings et al. Citation2017). Several examples stand out. Notably, a national coordinator, appointed in 2014 to safeguard democracy from violence-affirming extremism, now operates as a formal regulator of the field. This office eventually developed standards for what practices and beliefs were to be considered appropriate (Andersson Malmros and Mattsson Citation2017). The data analysed here also include debate articles written by the national coordinator, in which this actor estimated how well the municipalities were meeting these standards and highlighted some actors as more successful than others (e.g. Sahlin Citation2016). This type of status differentiating effectively helped exert institutional pressure for field actors to comply with the demands of the national coordinator (Andersson Malmros and Mattsson Citation2017). Conferences and similar events, another pivotal component of a field’s infrastructure (Hinings et al. Citation2017), on radicalisation and violence-affirming extremism have proliferated, and today represent central spaces for developing collective meaning-making and spreading fashionable “best practices” and knowledge (Davies Citation2018). Similarly, training for professionals and other local-level actors in detecting and combating diverse manifestations of radicalisation and violence-affirming extremism are plentiful (Herz Citation2016), and can be interpreted as a response to recurring media calls for more knowledge among frontline workers (see “Field alignment, 2010–2013”, ). This is aligned with the increasingly important role that academics and experts have come to play (see ). Those experts with the most social status eventually developed into what can be considered an informal governance body, validating and commenting, in the media, on policy proposals and efforts by policymakers (e.g. Ranstorp and Hyllengren Citation2015).

Table 1. Summary of findings.

In counter-terrorism research, the consequences of “radicalisation” and “violent extremism” entering public discourse and policy have been extensively explored and discussed (e.g. Kundnani Citation2012, Lindekilde Citation2012, Heath-Kelly Citation2013, Andersson Malmros Citation2019). Adding to this body of literature, this paper demonstrates the concepts’ structuring effects on the field’s infrastructure (as discussed above), and their role in localising PTER efforts. Most significantly, the idea of a radicalisation process transformed PTER to a local problem demanding local solutions, which organisationally resulted in municipalities becoming framed as key actors. The municipalities resisting to co-produce PTER efforts were publicly questioned and criticised in media by the field’s regulator and informal governance units (see also Andersson Malmros and Mattsson Citation2017). In hindsight, it is interesting to consider the result of this process: 134 of 290 Swedish municipalities developed CVE policies between 2015 and 2017, without any formal policy motivating them to do so (Andersson Malmros and Mattsson Citation2017). Hence, the rapidly expanded role of municipalities in PTER noticed during the Field Mobilisation-stage (2014–2016) was not a direct result of formal policy changes by national politicians, but can instead be interpreted as a consequence of radicalisation becoming integrated into the then existing field frame.

With the above example in mind, the paper does not imply politicians to be mere passive followers of dominant media representations. As partly accounted for previously in the paper, there are numerous examples in the data of politicians promoting specific frames in the media. On the basis of such data, it is clear that politicians use media platforms as a complementary, and sometimes alternative, arena for doing politics on PTER. This observation serves as a testimony of the complex interplay between political actors, dominant frames in the media, and policy change on PTER. The nature of this relationship deserves for more scholarly attention and firmly underlines the importance of incorporating new empirical data in the study of the PTER field.

5. Conclusion

The analysis of the PTER field presented in this paper portrays an unstable, fragmented, contested and conflicted field with changes triggered by TEEs. This portrayal contrasts the rational, stable accounts of the field’s development often presented in policy-centred research. Furthermore, the paper discerns the problems and solutions considered important and appropriate during each of the field’s five stages and illustrates how specific organisational actors were affected. Since previous literature suggests national policymaking on PTER as sensitive and reactive to different forms of institutional pressure (Crenshaw Citation2001, Malkki Citation2016, Smith et al. Citation2019), paying attention to how PTER is framed in media can help further our understanding of when and why policymakers on different levels act the way they do. The findings also exemplify the benefits of studying the development of the field from multiple theoretical and methodological approaches, as it unlocks the potential to explore new important facets, processes and actors relating to the field’s development.

The findings support literature identifying TEEs as key factors for change, but expands it by highlighting how such events can trigger translation and development of a new vocabulary (see also Spencer Citation2012). Since any significant societal challenge require “coordinated and sustained effort from multiple and diverse stakeholders toward a clearly articulated problem or goal” (George et al. Citation2016, p. 1881), this paper demonstrates how the establishment of a common, inclusive language is essential to mobilising and aligning stakeholders originating from different fields. Since fields are to be considered as the central space for mobilising the collective action necessary to resolve or counter societal challenges (Grodal and O’Mahony Citation2017), such insights are not only of value for the organising of PTER in other contexts but should also benefit policymaking and research concerned with other challenges and issues.

The paper also contributes to research on the impacts of critical events on field processes in general, and to counter-terrorism literature concerned with TEEs in particular. Three types of TEEs are identified and conceptualised in accordance with their respective impacts on field frames: redefining, supportive, and contentious events. With few exceptions, scholars have paid empirical and theoretical attention to events that result in major changes in fields (i.e. redefining events), whereas non-redefining events have received less attention. This paper shows that this focus is unhelpful. An important direction for future research is, therefore, to further consider how non-redefining TEEs matter for field processes.

Finally, while the study’s generalisability is limited by its singular case-study design, it has the potential to inform the understanding of field development in other geographical contexts and in relation to other issues. This includes the multiple impacts of critical events on field processes noted, and the importance of language to mobilise action and align fields. However, given the differences in national approaches to PTER noticed in previous research (e.g. Foley Citation2009, O’Brian Citation2016, Sivenbring and Andersson Mattsson Citation2019), the national context will affect how events are interpreted and how the fields develop. Why, how and what aspects (e.g. social, cultural, political and economic) of the national context that matters, remains an important task for future research.

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my gratitude to colleagues and conference participants who have helped develop this paper. The useful comments that I received when presenting the paper at the European Sociological Association’s 2019 conference in Manchester greatly helped advance my methodological approach. I also want to thank Jennie Sivenbring (Segerstedt Institute, University of Gothenburg) for her reflections on the paper’s contributions to terrorism studies, Patrik Zapata and Carina Abrahamson Löfström (School of Public Administration, University of Gothenburg) for helping me improve the structure of the paper, and Susanne Boch Waldorff (Department of Organization, Copenhagen Business School) for the feedback and comments on the theoretical contribution of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In May 1999, two police officers were shot dead outside Malexander by three neo-Nazis. Later in October, Björn Söderberg, a 41-year-old syndicalist, was killed by two neo-Nazis.

2 Försvarets Radioanstalt (the National Defense Radio Establishment), responsible for electronic surveillance.

3 The term “violence-affirming” (våldsbejakande) extremism was originally used by the Swedish security police to “distinguish acts and activities that may threaten security – such as supporting or participating in ideologically motivated acts of violence – by those who are not violent, but who can be problematic from other perspectives” (Swedish Security Police Citation2010, p. 26).

References

- Andersson Malmros, R., 2019. From idea to policy: Scandinavian municipalities translating radicalization. Journal for deradicalization (18), 38–73.

- Andersson Malmros, R. and Mattsson, C., 2017. Från ord till handlingsplan – En rapport om kommunala handlingsplaner mot våldsbejakande extremism [From words to action plan: a report on municipal action plans against violent extremism]. Stockholm: Sveriges kommuner och landsting.

- Argomaniz, J., 2009. Post-9/11 institutionalization of European Union counter-terrorism: emergence, acceleration and inertia. European security, 18 (2), 151–172.

- Balestrini, P.P., 2020. Public opinion and terrorism: does the national economic, societal and political context really matter? European security, 29 (2), 189–211.

- Birkland, T., 2004. “The world changed today”: agenda-setting and policy change in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks. Review of policy research, 21 (2), 179–200.

- Bodström, T. 2006. Terrorismen slår mot demokratin [Terrorism strikes against democracy]. Aftonbladet, 12 August, p. 30.

- Bossong, R., ed. 2012. The evolution of EU counter-terrorism: European security policy after 9/11. London: Routledge.

- Brinson, M.E. and Stohl, M., 2012. Media framing of terrorism: implications for public opinion, civil liberties, and counterterrorism policies. Journal of international and intercultural communication, 5 (4), 270–290.

- Crenshaw, M., 2001. Counterterrorism policy and the political process. Studies in conflict and terrorism, 24 (5), 329–337.

- Davies, L., 2018. Review of educational initiatives in counter-extremism internationally: what works? Gothenburg: The Segerstedt Institute, University of Gothenburg.

- Du Gay, P., 1996. Consumption and identity at work. London: Sage.

- Duriau, V., Reger, R., and Pfarrer, M., 2007. A content analysis of the content analysis literature in organization studies: research themes, data sources, and methodological refinements. Organizational research methods, 10 (1), 5–34.

- Fligstein, N. and McAdam, D., 2012. A theory of fields. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Foley, F., 2009. Reforming counterterrorism: institutions and organizational routines in Britain and France. Security studies, 18 (3), 435–478.

- Gamson, W.A. and Modigliani, A., 1989. Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power: a constructionist approach. American journal of sociology, 95 (1), 1–37.

- George, G., et al., 2016. Understanding and tackling societal grand challenges through management research. Academy of management journal, 59 (6), 1880–1895.

- Goffman, E., 1974. Frame analysis: an essay on the organization of experience. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Greenwood, R., Suddaby, R., and Hinings, C.R., 2002. Theorizing change: the role of professional associations in the transformation of institutionalized fields. Academy of management journal, 45 (1), 58–80.

- Grodal, S., 2007. The emergence of a new organizational field: labels, meaning and emotions in nanotechnology. Thesis (PhD). Stanford University.

- Grodal, S. and O’Mahony, S., 2017. How does a grand challenge become displaced? explaining the duality of field mobilization. Academy of management journal, 60 (5), 1801–1827.

- Gustafsson, L. and Ranstorp, M., 2017. Swedish foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq. Stockholm: Center for Asymmetric Threat Studies, Swedish Defense University.

- Harris-Hogan, S., Barrelle, K., and Zammit, A., 2016. What is countering violent extremism? exploring CVE policy and practice in Australia. Behavioral sciences of terrorism and political aggression, 8 (1), 6–24.

- Hassan, O., 2010. Constructing crises (in) securitising terror: the punctuated evolution of EU counter-terror strategy. European security, 19 (3), 445–466.

- Heath-Kelly, C., 2013. Counter-terrorism and the counterfactual: producing the “radicalisation”discourse and the UK PREVENT strategy. The British journal of politics and international relations, 15 (3), 394–415.

- Herz, M., 2016. Socialt arbete, pedagogik och arbetet mot så kallad våldsbejakande extremism: En översyn [Social work, pedagogy and the work against so-called violent extremism: a review]. Gothenburg: The Segerstedt Institute, University of Gothenburg.

- Hinings, C.R., Logue, D.M., and Zietsma, C., 2017. Fields, institutional infrastructure and governance. In: R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, T. Lawrence, and R. Meyer, eds. The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism. London: Sage, 163–189.

- Hoffman, A., 1999. Institutional evolution and change: environmentalism and the U.S. chemical industry. Academy of management journal, 42 (4), 351–371.

- Hoffman, A.J. and Ocasio, W., 2001. Not all events are attended equally: toward a middle-range theory of industry attention to external events. Organization science, 12 (4), 414–434.

- Kundnani, A., 2012. Radicalisation: the journey of a concept. Race & class, 54 (2), 3–25.

- Lindekilde, L., 2012. Introduction: assessing the effectiveness of counter–radicalisation policies in northwestern Europe. Critical studies on terrorism, 5 (3), 335–344.

- Lööw, H., Mattsson, C., and Poohl, D. 2013. Olika slag av extremism kräver olika slags åtgärder [Different forms of extremism demands different measures]. Dagens Nyheter, 15 December, p. 6.

- Lounsbury, M., Ventresca, M., and Hirsch, P.M., 2003. Social movements, field frames and industry emergence: a cultural–political perspective on US recycling. Socio-economic review, 1 (1), 71–104.

- Maguire, S. and Hardy, C., 2009. Discourse and deinstitutionalization: the decline of DDT. Academy of management journal, 52 (1), 148–178.

- Malkki, L., 2016. International pressure to perform: counterterrorism policy development in Finland. Studies in conflict & terrorism, 39 (4), 342–362.

- Mattsson, C. and Johansson, T., 2019. Life trajectories into and out of contemporary neo-Nazism: becoming and unbecoming the hateful other. London: Routledge.

- Meyer, A., 1982. Adapting to environmental jolts. Administrative science quarterly, 27 (4), 515–537.

- Meyer, R.E. and Höllerer, M.A., 2010. Meaning structures in a contested issue field: a topographic map of shareholder value in Austria. Academy of management journal, 53 (6), 1241–1262.

- Munir, K.A., 2005. The social construction of events: a study of institutional change in the photographic field. Organization studies, 26 (1), 93–112.

- Nigam, A. and Ocasio, W., 2010. Event attention, environmental sensemaking, and change in institutional logics: an inductive analysis of the effects of public attention to Clinton’s health care reform initiative. Organization science, 21 (4), 823–841.

- Nohrstedt, D. and Hansén, D., 2010. Converging under pressure? Counterterrorism policy developments in the European Union member states. Public administration, 88 (1), 190–210.

- O'Brien, P., 2016. Counter-terrorism in Europe: the elusive search for order. European security, 25 (3), 366–384.

- Pekgul, C. 2010. De skapar en kränkt muslimsk identitet [They create a violated Muslim identity]. Aftonbladet, 18 December, p. 42.

- Pride, R.A., 1995. How activists and media frame social problems: critical events versus performance trends for schools. Political communication, 12 (1), 5–26.

- Ranstorp, M. and Hyllengren, P., 2013. Förebyggande av våldsbejakande extremism i tredjeland: Åtgärder för att förhindra att personer ansluter sig till väpnade extremistgrupper i konfliktzoner [Prevention of violent extremism in third countries: measures to prevent people from joining armed extremist groups in conflict zones]. Stockholm: Swedish National Defence College.

- Ranstorp, M. and Hyllengren, P. 2015. Stort behov förebygga radikalisering i Sverige [Great need to prevent radicalisation in Sweden]. Dagens Nyheter, 16 February, p. 6.

- Sahlin, M. 2016. Många kommuner saknar en plan mot extremism [Many municipalities lack a policy against extremism]. Dagens Nyheter, 20 April, p. 6.

- Scott, W.R., 2014. Institutions and organizations: ideas, interests, and identities. London: Sage.

- Sivenbring, J. and Andersson Malmros, R., 2019. Mixing logics: multiagency approaches for countering violent extremism. Gothenburg: The Segerstedt Institute, University of Gothenburg.

- Smith, B.K., Stohl, M., and Al-Gharbi, M., 2019. Discourses on countering violent extremism: the strategic interplay between fear and security after 9/11. Critical Studies on terrorism, 12 (1), 151–168.

- Snow, D.A. and Benford, R.D., 1988. Ideology, frame resonance, and participant mobilization. International social movement research, 1 (1), 197–217.

- Spencer, A., 2010. The tabloid terrorist: the predicative construction of new terrorism in the media. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Spencer, A., 2012. The social construction of terrorism: media, metaphors and policy implications. Journal of international relations and development, 15 (3), 393–419.

- Strandh, V. and Eklund, N., 2015. Swedish counterterrorism policy: an intersection between prevention and mitigation? Studies in conflict and terrorism, 38 (5), 359–379.

- Suddaby, R. and Greenwood, R., 2005. Rhetorical strategies of legitimacy. Administrative science quarterly, 50 (1), 35–67.

- Swedish Ministry of Culture. 2011. Handlingsplan för att värna demokrati mot våldsbejakande extremism [Action plan to protect democracy against violent extremism]. (Report No. Skr. 2011/12:44). Available from: https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/skrivelse/2011/12/skr.-20111244/ [Accessed 31 August 2020].

- Swedish Security Police. 2010. Våldsbejakande islamistisk extremism i sverige [Violent-affirming Islamic extremism in Sweden]. Available from: https://www.cve.se/download/18.62c6cfa2166eca5d70e2160/1547452379244/Säpo%20Våldsbejakande%20islamistisk%20extremism%202010.pdf [Accessed 31 August 2020].

- Vermeulen, F., 2014. Suspect communities – targeting violent extremism at the local level: policies of engagement in Amsterdam, Berlin, and London. Terrorism and political violence, 26 (2), 286–306.

- Zietsma, C., et al., 2017. Field or fields? Building the scaffolding for cumulation of research on institutional fields. Academy of management annals, 11 (1), 391–450.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strings in Mediearkivet

Appendix 2. Search strings in the database

2A. Actors

2B. Events

2C. Extremist milieu of focus

2D. Phenomena of focus