ABSTRACT

Increasingly, misinformation is a pressing security problem. Different types of counter-disinformation strategies have been proposed and tested in a growing number of studies. The findings from these studies, however, are limited to predominantly North American and Western European contexts where ordinary people are recipients of mis- or disinformation. There is a considerable gap in our understanding of the susceptibility to false information in closed communities like state security forces. To remedy this problem, the aim of this study is twofold: (1) examine the susceptibility of Czech members of armed security forces to misinformation and (2) in this context, test the effectiveness of two types of counter-disinformation strategies: prebunking and persuasive communication. We present a survey experiment of 618 officers from the Czech police and army. While we do not find support for the effect of persuasion or prebunking on perceived information accuracy, we show that the use of positive persuasion creates a gap in how police and army officers evaluate false and biased statements. The results offer an evaluation of the resilience of the Czech security forces to mis- and disinformation and suggest developing tailored approaches to counter disinformation in Czechia and elsewhere.

Introduction

Security implications of misinformation have come to the forefront of academic and public policy debates. While the severity of the problem differs across countries, available data suggest that Western Europe and North America tend to do well in media literacy as opposed to Central, Eastern, and Southern Europe that are most vulnerable to mis- and disinformation (Lessenski Citation2022). For example, the belief in conspiracy theories has been an increasing problem in Slovakia whose society is vulnerable to Russian influence (Euronews Citation2023). In neighbouring Czechia, while the public is aware of the existence of disinformation, people lack an understanding of misinformation’s impact as well as the motivations and mechanisms behind its spread (Euroskop Citation2022). In the 2021 Czech parliamentary election, about 46 per cent of surveyed Czechs believed at least one made-up political attack peddled by various conspiracy websites (STEM Citation2021).

The spread of mis- and disinformationFootnote1 coupled with a high susceptibility of the public to believe in false claims poses a growing security threat to states. On the one hand, misinformed key public figures, whether high-level state officials, bureaucrats or various state personnel, make suboptimal decisions that may jeopardise effective state administration and even state security (Pantazi et al. Citation2021). On the other hand, in democratic societies, the misinformed or purposefully deceived public may reject some beneficial policies or force their government into suboptimal decisions through, for example, electoral pressure or protest behaviour (Vasu et al. Citation2018, Dowling and Legrand Citation2023). Long-term internal security implications are the erosion of trust in society, government or democratic systems and potential internal destabilisation (e.g. Hunter Citation2023).

The susceptibility of state security structures and personnel to misinformation is especially problematic for national security. There is a lack of literature on the vulnerability of political elites, including state personnel, to disinformation. While some scholars have investigated the intentional use of disinformation by the state (i.e. covert action) (Landon-Murray et al. Citation2019), we know very little about how misinformation affects the inner workings of the state, whether in security or other areas. By focusing on state security personnel, this article begins to fill this gap in our understanding of the vulnerability of state structures to misinformation. We use Czechia as an illustrative case to answer two research questions: How susceptible are state security forces to mis- and disinformation? How effective are counter-disinformation strategies among members of state security communities?

To answer these questions, we conduct a survey experiment of 618 officers in active service in the Police of the Czech Republic (525 adults) and the Czech Army (93 adults). In the survey, we evaluate both the susceptibility of these officers to misinformation and the effectiveness of two types of counter-disinformation strategies: prebunking and persuasive communication. As per the prevailing literature, we expect that both generic prebunking (i.e. the use of targeted messages to preemptively debunk misinformation) and persuasive communication will increase respondents’ ability to recognise false claims, albeit to different degrees. We also hypothesise that officers exposed to any of these counter-disinformation strategies will be less likely to exhibit biased opinions about their service.

We strive to make two types of contributions to the existing knowledge: (1) we offer an insight into the closed world of security communities where research access tends to be difficult but where the impact of misinformation may shape state security in potentially profound ways and (2) we test the effectiveness of common counter-disinformation strategies to advance the practical stream of literature on mis- and disinformation. While the results of our experiment are not statistically significant, thanks to our pre-treatment we find that Czech police and army officers trust public broadcasters considerably more than disinformation portals and that they are also able to identify false messages, albeit not flawlessly. The findings are, therefore, generally encouraging in their implications for Czech national security as they reveal some resistance to disinformation among state security personnel. Our findings also highlight the significance of a further evaluation of common counter-disinformation strategies – especially in different societal contexts – since the effectiveness of these strategies seems to differ both across and within different (security) communities.

Countering disinformation, building resilience: a theoretical background

Both misinformation (i.e. spread of false information) and disinformation (i.e. intentional spread of false information) are increasingly pressing societal problems with implications for voting behaviour, disaster preparedness, climate change mitigation and public health, among many other things (Sawano et al. Citation2019, Wilson and Wiysonge Citation2020, Zimmermann and Kohring Citation2020, Lewandowsky Citation2021). Misinformation has also had adverse effects on security, for example, with some violence and vandalism following the spread of false claims in Asia (Dixit and Max Citation2018, Mozur Citation2018). Disinformation targeting the state’s military, intelligence agencies, border protection services or the police jeopardises state security. At the minimum, misinformed security personnel are more likely to make suboptimal decisions, with adverse downstream effects on the society that they are tasked to protect.

In general, strategies to counter disinformation can be divided into engaging (or responsive) and disengaging (or alternative), with the former being much more common. Prevailing counter-disinformation strategies discussed in the literature are of the responsive type as they involve some type of a response to the existing disinformation threat – either against the message or the messenger (or both) where the aim is to target the original strategy’s critical vulnerabilities in the same environment in which the false messages occur (Schmitt et al. Citation2018, Curtis Citation2021). These strategies frequently involve short-term or immediate activities like debunking (correcting false statements, fact-checking), turning the tables (the use of humour or sarcasm to discredit the opponent), disrupting the disinformation network and blocking the opponent’s messages (Chan et al. Citation2017, Bjola Citation2019, Nieminen and Rapeli Citation2019, Saurwein and Spencer-Smith Citation2020, Walter et al. Citation2020, Bor et al. Citation2021).

Relatively less attention has been paid to disengaging counter-disinformation strategies although these are rooted in decades-old psychological research (McGuire Citation1961, Citation1970, McGuire and Papageorgis Citation1962). In the long-term, these strategies may involve prevention campaigns such as educational programmes and various media support initiatives, or even legal solutions like speech laws and censorship (McGeehan Citation2018, Stray Citation2019, Bor et al. Citation2021, Greene et al. Citation2021, Fitzpatrick et al. Citation2022). The idea is the inoculation of the public against disinformation – building resistance to harmful persuasive messages to improve individuals’ psychological resistance and sentiment (Guan et al. Citation2021). Short-term inoculation strategies involve so-called prebunking where individuals are exposed to messages designed to teach them to recognise misleading claims if they are exposed to them in the future. Training people to recognise false claims helps them become resistant to mis- and disinformation in different contexts (Roozenbeek et al. Citation2020).

Disengaging type of messaging does not tend to directly address specific disinformation messages and it sometimes promotes its own narrative (Stray Citation2019). Unlike prebunking, at the core of these strategies are alternative narratives that vary depending on specific socio-political contexts, from endorsing some type of morality to promoting particular worldviews. For example, Hellman and Wagnsson (Citation2017, p. 160) explain that the role of one disengaging strategy – naturalising – is “to maintain and spread values by being a good example, and the values promoted tend to be depicted as universal”. This approach “seeks to construct advantageous narratives mainly about the state and its worldview, [showing] foreign audiences a positive and appealing image of the nation and thus boost[ing] the state and its worldview in the long term” (Hellman and Wagnsson Citation2017, p. 160). In other words, some disengaging counter-disinformation strategies are a type of persuasive communication.

Persuasive communication is a type of communication meant to “persuade” the target audience in order to achieve some objective; it includes propaganda but also other types of communication like advertising or political campaigning (Martin Citation1971). When countering disinformation, the logic behind persuasive narratives is that pointing out false messages may not be as effective as providing alternative (and positive) narratives. These may not only inoculate individuals against mis- and disinformation but also dislodge false narratives from society (Stray Citation2019). Such alternative narratives are, of course, problematic for their potential to turn into propaganda or even misinformation itself.

The experimental literature on counter-disinformation strategies tends to focus on the effectiveness (or impact) of fact-checking (i.e. debunking) in different contexts, from US legislature and US elections to political advertising and social media (Fridkin et al. Citation2015, Nyhan and Reifler Citation2015, Wintersieck Citation2017, Margolin et al. Citation2018). There has also been a recent uptick in scholarly interest in prebunking, with promising experimental results on its effectiveness (Compton et al. Citation2021, Lewandowsky and van der Linden Citation2021). However, the findings from these studies are limited to predominantly North American and Western European contexts where ordinary people are recipients of mis- or disinformation. There is a considerable gap in our understanding of the susceptibility to mis- and disinformation in closed communities like state security forces and, broadly speaking, the political elites. In the Central European context, studies are lacking on what strategies may be effective in countering the spread of mis- or disinformation among these types of individuals.

Hypotheses

This study primarily evaluates two disengaging counter-disinformation strategies: prebunking and persuasive communication that focuses on patriotism. We test the effectiveness of these strategies on a group of Czech police and army officers through an evaluation of three hypotheses, as discussed below. To gain a better understanding of the problem of misinformation among the Czech security forces we also measure how likely the members of these security communities are to attribute credibility or truthfulness to misinformation.

The logic of prebunking is rooted in McGuire’s (Citation1961) “inoculation theory” and specifically the use of vaccines to build antibodies against viruses. Like with vaccines and viruses, individuals can be inoculated against misinformation, developing antibodies (i.e. mental resistance) as they are exposed to a weakened persuasive attack (e.g. Pfau Citation1997). Prebunking thus means preemptively debunking misinformation. Generally, inoculation against misinformation is a two-step process that involves warning of an upcoming challenge to the recipient’s thinking or beliefs (i.e. generic inoculation messages) and an explanation of how misleading works (i.e. specific inoculation messages) (Amazeen et al. Citation2022). The latter could be done, for example, through an explanation of inconsistencies in reasoning, exposure of misleading strategies or refutation of false claims along with the provision of alternative explanations (e.g. Swire et al. Citation2017, Tay et al. Citation2022).

Research has shown that prebunking – and especially generic inoculation messages that contain only forewarning without refutation – is effective in a wide variety of contexts and issue areas (see Amazeen et al. Citation2022). These include public health, crisis communication, conspiracy theories and radicalisation – the last being particularly pertinent to the Central European context (Braddock Citation2019, Basol et al. Citation2021, Saleh et al. Citation2021). Right-wing radicalisation towards extremism among the Czech armed forces is of increasing concern although the full extent of this trend is not known and there are very few observed cases (Mareš Citation2009, Citation2018, Liederkerke Citation2016). Our research thus has potential practical implications since we expect generic prebunking among state security personnel to be an effective counter-disinformation strategy. Our first hypothesis aligns with this expectation:

H1: Generic prebunking (i.e. messages with only forewarning and without refutation) is likely to increase an individual’s ability to recognize truthful claims.

In studies on the effectiveness of persuasive communication, the dependent variable tends to vary and includes, for example, regime stability, the outcome of democratic elections, revolutions and terrorist recruitment (Conway et al. Citation2012, Houck et al. Citation2017, Huang Citation2018). In our case, if inoculation against false messages works, we should observe the target audience to be more likely to recognise a false claim after exposure to a positive persuasive message.

Persuasive communication is generally effective when the source is credible and trustworthy, but it is chiefly the characteristics of the target audience that determine the persuasiveness of the message (Martin Citation1971). A crucial factor is the motivation that influences how individuals process incoming messages. There is a large literature on motivated reasoning (Kunda Citation1990), which explains how individuals’ prior attitudes and beliefs affect their judgements, decisions and behaviours (e.g. Slothuus and de Vreese Citation2010, Dieckmann et al. Citation2017). Various factors, such as cognitive biases, values, norms or identities, shape individuals’ motivations for processing messages (Sinatra et al. Citation2014). As per the logic of motivated reasoning, we expect that the members of state security forces will be more prone to accept messages in line with their pre-existing beliefs and attitudes. Patriotic individuals, for example, are more likely to accept messages that highlight the positive image of one’s country. Studies on the characteristics of individuals serving in the Czech state security forces are lacking, but we expect that motivated reasoning may dampen the effectiveness of persuasive communication among some individuals much like it dampens the effectiveness of debunking and specific inoculation messages (generic prebunking seems to be more immune to motivated reasoning) (Coddington et al. Citation2014, Amazeen et al. Citation2022). This suggests our second hypothesis:

H2: Persuasive communication is likely to increase an individual’s ability to recognize truthful claims but less so than generic prebunking.

H3: Individuals exposed to prebunking or relevant persuasive communication are more likely to exhibit unbiased opinions about their respective line of work.

The experiment: design and procedures

Experimental design

To test our hypotheses, we examine three experimental conditions, two of which are treatment conditions (generic prebunking and positive persuasive messaging). The control group was a pure control group without any treatment at all. The treatment conditions are embedded in purposively designed humorous messages – i.e. memes. Memes are an increasingly common vehicle for persuasive messaging; they are “bite sized nuggets of political ideology and culture that are easily digestible and spread by netizens” (DeCook Citation2018, p. 485). We have chosen memes as our vehicle for counter-disinformation strategies for two reasons. First, these messages tend to combine simple language, culturally meaningful pictures or symbols and humour, which are all characteristics that the extant literature has linked to effective messaging (Houck et al. Citation2017, DeCook Citation2018, Bjola Citation2019). Second, Lewandowsky (Citation2021) suggests art, including novel ways of presenting narratives, as an effective means of communication against mis- and disinformation. To maximise external validity, we have adapted existing memes circulating on the Czech social media sites.

Our experimental sample was divided into three groups. The first treatment group received a generic prebunking message embedded in a meme. This message consists of a forewarning, which aims to warn the recipients that some groups use misleading tactics to shape people’s opinions. Our meme focuses on seemingly legitimate newspaper articles that may contain hidden misinformation intentionally spread by Russian actors. The second treatment group received a positive persuasive message. The meme chosen for this group was designed to build and/or enhance moral values and principles, which – if aligned with pre-existing beliefs and attitudes – should increase this group’s resistance to misinformation. Specifically, our meme depicts patriotic attitudes in enduring the 2022 energy crisis together. In line with the logic of positive persuasive narratives, the meme projects unity, strength and resilience of the Czechs as national values and commendable traits in the face of national hardship.

We recognise that focusing on Russia may make our tested strategies somewhat less disengaging. Our objective was to create memes around narratives relevant to the geopolitical and socio-economic contexts at the time of the experiment. Making the memes relatable should increase their effectiveness (DeCook Citation2018). This, however, does not change the nature of the general prebunking message as it still warns its audience of the impending disinformation. With respect to our persuasive narrative, while we place it in the context of the 2022 energy crisis triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the overwhelming focus of the message is on one’s own narrative and positive image without explicitly contrasting it with the other side’s narrative. This meets the criteria for this strategy (e.g. Hellman and Wagnsson Citation2017, p. 160). Both treatments can be found in Appendix 1.

Experimental procedures

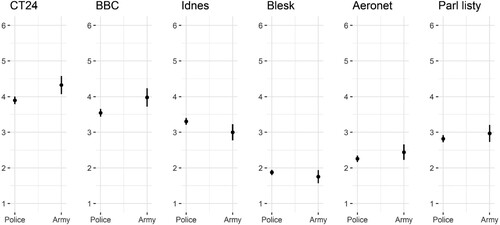

Prior to evaluating the effectiveness of counter-disinformation strategies we wanted to better understand the extent to which members of the Czech security forces consume and recognise misinformation. To this end, in the pre-treatment part of the questionnaire, we included questions about respondents’ degree of trust in select online media sources. Specifically, we asked the participants to express their trust in two public broadcasters (CT24 as the main news channel of the public Czech Television and BBC as a renowned foreign media), two private Czech media (the news portal Idnes.cz and the most popular tabloid in Czechia, Blesk.cz), and two disinformation portals (Aeronet and Parlamentni listy). The participants expressed their trust on a 1–6 scale with higher values indicating higher trust.

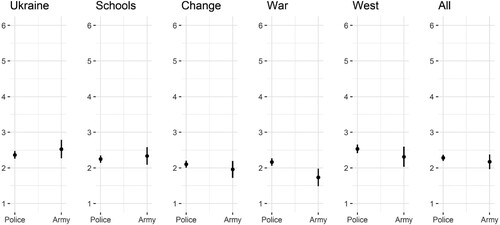

We also asked the respondents to read a series of short false messages (five in total) taken directly from Twitter (included in Appendix 2). These messages contained misrepresentations and objectively false information on several popular topics: financial help to Ukraine at the expense of Czech families, state propaganda in public schools, a change from peace to war in Czechia (as a result of a recent election), the USA using the Czech army as “a useful idiot” for war and the Czech prime minister’s servile attitude towards the West. The objective was to see how much the respondents believed that the messages correspond to reality. They answered on a 1–6 scale with 1 meaning does not correspond at all and 6 meaning fully corresponds. Higher values thus indicate that the participants believe the stories reflect reality.

For the experiment itself, we have two dependent variables. The first one is the ability to assess the truthfulness of information. Following Stecula et al. (Citation2020), we measure this ability through perceived information accuracy. We presented the respondents with a set of false or misleading claims commonly found on the Czech social media sites about the 2022 energy crisis in Europe and asked them to rate the claims’ perceived accuracy. We asked: To what extent do you agree with the following statements related to the previous message from social media? The response categories were strongly disagree, disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, agree and strongly agree. We constructed a scale from 0 to 1 (most misinformed) that averaged the responses.

With respect to our second dependent variable, we are interested in seeing whether inoculation affects intended behaviour among state security personnel, and specifically these individuals’ willingness to carry out their duties in an unbiased way. To measure this variable, we presented the participants with a series of claims related to their service duties and asked them to what extent they agreed with these claims. The list differed slightly for the members of the police vs the army to accurately reflect their operational environments. The claims were that Ukrainian refugees should be deported immediately after committing a crime or misdemeanour; citizens of the Russian Federation should not be allowed into the Czech Republic at all; pro-Ukraine demonstrations should be banned and disbanded immediately; using coercion during interrogation of Ukrainians can often lead to better results; when dispersing pro-Russian demonstrations, coercive means should be deployed as quickly as possible. The response categories were strongly disagree, disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, agree and strongly agree. We constructed a scale from 0 to 1 (most disagree) that averaged the responses.

Our experimental protocol followed standard procedures, including standard ethical procedures. After consenting to participate in this study, respondents completed a background questionnaire on basic socio-economic characteristics, professional traits, news consumption habits and political attitudes. They were then randomly assigned to one of three experimental conditions. Following Amazeen et al. (Citation2022), we asked respondents to imagine that they logged into their Facebook account and saw the presented meme. After that, respondents received a brief report (another Facebook post) and were asked to read it carefully. The report contained false and misleading claims about the 2022 energy crisis in Europe (adapted from the relevant prevailing claims on the Czech social media sites). We followed the treatment conditions with two manipulation checks to see whether respondents understood the treatment. Respondents were then asked to evaluate the truthfulness (i.e. perceived accuracy) of some of the claims from the report.

Results

We fielded the experiment in the summer of 2023 to a sample of 525 adults in active service in the Police of the Czech Republic. For comparative purposes and to gain a broader understanding of the problem of misinformation among the Czech security personnel, we also included a sample of 93 members of the Czech Army in active service. Therefore, our total sample is 618.

The police sample was attained by recruiting respondents from different police branches, including the organised crime unit, the counter-terrorism unit, the riot police, the patrol service and the training service. Respondents for the army sample were recruited mainly from the participants in training courses organised by the University of Defense of the Czech Republic. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Data were collected using either electronic or paper versions of the questionnaire, based on the preference of the surveyed unit.

Three-quarters of the sample are men. The sample consists primarily of younger security officers with three-quarters below 40 years of age. In terms of education, the largest group are the participants who completed high school (365), followed by holders of Master’s (141) and Bachelor’s (96) degrees. Almost 39% of the respondents have a university education. Given some potential impact of these socio-demographic features on individuals’ information processing (Guess et al. Citation2019, Roozenbeek and van der Linden Citation2019), we use sex, age and education as control variables in the regression models below.

Our pre-treatment questions about respondents’ trust in news media reveal that in general, public broadcasters enjoy the highest levels of trust among the surveyed Czech security personnel. On the 1–6 scale, CT24 obtained a mean value of 3.96, followed by BBC with 3.61. Respondents’ trust in disinformation portals is considerably lower although the score for Parlamentni listy (2.84) is not far behind Idnes.cz (3.26). Respondents expressed the lowest trust in the tabloid Blesk (1.86), which is in line with the general sentiment towards tabloids in Czech society (Boček Citation2017).

plots the results for members of both the police and the army. While the levels of trust in media are similar for both groups, soldiers express a slightly higher trust in both public broadcasters than the police officers, and the opposite is true regarding the private news portal Idnes.cz. We observe no significant difference in trust in the disinformation portals and the tabloid. Members of the army are thus found to be somewhat more trusting when it comes to information provided by public institutions.

With respect to respondents’ ability to recognise misinformation, we find that they mostly identify the presented messages as false or inaccurate. The mean values for each message ranged from 2.08 to 2.50. A tweet about a post-electoral change leading to conflict (“change” in ) received the lowest score, while the highest value was assigned to a tweet mocking the Czech Prime Minister and depicting him as a servant of his Western masters (“West” in ).

presents separate results for the members of the police and the army. The plot consists of six parts, with the last one representing mean assessments of all five tweets. The figure shows almost no difference between the police and army officers. The only exemption is the fourth message – its focus is the Czech Army, which, supported by the national government, wants to drag Czechia into war, acting as a useful idiot for the USA. For this tweet, the police officers’ answers have a mean value of 2.16, while the score for soldiers is significantly lower (p < .01) at 1.73.

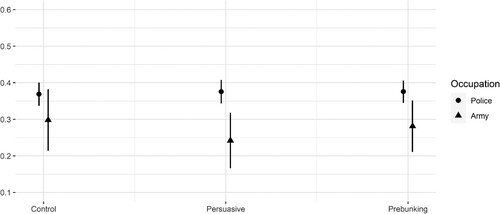

Next, we present the results of our experiment. The first dependent variable captures the ability of respondents to identify the truthfulness (or accuracy) of four false or misleading claims about the 2022 energy crisis circulating on Czech social media. For each participant, we calculate the mean value of their four answers. Note that the dependent variable is a 0–1 scale with higher values indicating that the respondents assess the claims as trustworthy, i.e. they do not identify them as misinformation. Model 1 includes only the experimental treatments and the control variables. Its results () indicate that both types of messages (i.e. positive persuasion and generic prebunking) are without any effect. For the control group that received no treatment, the measured score is .269. In the case of the group that received a positive persuasive treatment, the score is .265, and almost the same goes for the prebunking group (.271). None of the effects is statistically significant.

Table 1. Assessment of perceived information accuracy.

Model 2 has an expanded specification as it includes an interaction term between the treatments and the participants’ occupations. plots the results of the interaction. Among the members of the police force none of the treatments has any impact on the dependent variable. The estimated values of the perceived information accuracy range from .375 to .382. For soldiers, a slightly different pattern emerges. It is true that none of the treatments has a statistically significant effect on the dependent variable; however, the estimated values show that the use of positive persuasive messaging makes a difference between police officers and soldiers. While for the former we find a score of .382, for the latter the value is .248, i.e. it is lower by more than 13 percentage points. A similar but smaller gap is found for the group with the generic prebunking treatment; however, in this case, the difference between police officers and soldiers is at the edge of statistical significance. Although we do not find support for H1 and H2, our results indicate that inoculation can potentially lead to differences in how members of different forces assess the accuracy of information and how resistant they are to mis- and disinformation.

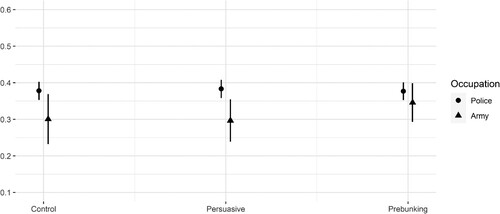

Our second dependent variable measures the extent to which the respondents agree with five statements that reflect select institutional norms and procedures. The mean value of all the answers was calculated and normalised to a 0–1 scale with higher values indicating higher agreement with the presented statements. presents the results. Model 3 includes only our treatments and the control variables. The score of .424 in the control group signals that respondents disagree with the statements they were asked to evaluate. Application of either treatment has no impact on this outcome as none of the effects is significant and meaningful.

Table 2. Agreement with biased statements.

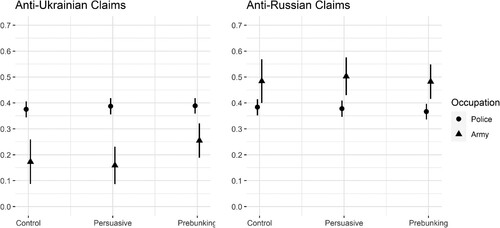

Model 4 adds an interaction term between the experimental treatments and the participants’ occupations. As shows, the findings add little when compared to Model 3, which treats participants as a homogeneous group regardless of their professional assignment. We find that treatments have no impact on how either members of the police force or the army agree with the presented statements. While we find that the adoption of positive persuasive messaging produces a gap between the two professions, compared to the outcomes for perceived information accuracy (), this difference between the police officers and soldiers is smaller and it is at the edge of statistical significance.

A possible explanation of the different impacts of positive persuasion in Models 2 and 4 may lie in the nature of the claims the participants had to consider. In the first dependent variable, all claims were false or misleading, so similarly high (or low) scores by the participants indicated their consistency in how they treated these messages. The second dependent variable, however, is built from five responses, and the statements differ in their content. Out of the five items, three present an anti-Ukrainian stance whereas the remaining two have anti-Russian character.

To test whether this affects our results, we split our second dependent variable into two: pro-Ukrainian and pro-Russian bias. We calculated the mean for responses to three anti-Ukrainian statements and normalised them to a 0–1 scale and we did the same for the two anti-Russian statements. Given the nature of these statements, attitudes towards them should be opposite. Normally, people who hold a pro-Ukrainian stance are anti-Russian and vice versa; therefore, the values of the two variables should be negatively correlated. Surprisingly, we find a positive correlation of r = .283 (p < .001) for the police officers. For soldiers, we find no such correlation (r = −.060, p > .050). This suggests that the surveyed police officers either agree with anti-Ukrainian and anti-Russian messages simultaneously or they refuse them all.

We calculated two more models (shown in Appendix 3), one for each part of our second dependent variable. Both have the same specification as Model 4. plots the results from these models, which show a substantial difference between the police and army members. On the one hand, the scores by police officers are almost constant across messages with respect to the character of statements they evaluated and the experimental group they were assigned to. In none of the scenarios does the measured agreement of police officers with the presented statements change compared to the respective control group. Members of the police are thus found to be generally less supportive of all the statements they evaluated as their scores in the two models vary between .370 and .392.

On the contrary, members of the army express strikingly different attitudes. The soldiers agree to a substantially larger extent with the procedures and norms that are anti-Russian rather than anti-Ukrainian. While in Model 5 (covers anti-Ukrainian statements) their scores vary between .163 and .258, in Model 6 (covers anti-Russian messages) the agreement of soldiers with such procedures ranges from .486 to .507. While the results for police officers are stable regardless of the nature of the statements, the extent of agreement of soldiers with the same messages strongly depends on their nature in light of the Russian attack on Ukraine. Importantly in our experiment, we find that in comparison to the control group, it is the positive persuasive treatment that increases the gap between the two professions. This outcome suggests that positive persuasion has a larger potential to affect the behaviour and attitudes of the armed forces than generic prebunking.

We also find some effect of the control variables on participants’ ability to identify misinformation.Footnote2 Our results show that women, older people and those with lower levels of education are less able to identify misinformation. We also find that women and fewer educated individuals express a higher agreement with biased statements, but we find no effect of age. In sum, the socio-demographic variables we used as controls partly contribute to our understanding of how security personnel view information accuracy. Although their effects and significance vary across our models, these outcomes indicate that different social groups, including within security communities, exhibit varying resistance to misinformation. This aligns with some of the general extant literature, particularly concerning the relationship between age and susceptibility to false information. Brashier and Schacter (Citation2020), for example, explore cognitive declines, social changes and digital illiteracy as some of the main reasons why older adults engage more frequently with fake news. For example, with increasing age some cognitive processes like recollection decline. Older individuals are also likely to misunderstand how algorithms bring forth information online and how sharing information on the Internet indicates endorsement.

Discussion and conclusion

This article begins to shed light on the internal vulnerability of the state to mis- and disinformation, particularly among state security communities. We focused specifically on the Czech police and army to evaluate how susceptible the state security personnel are to disinformation and how effective prevailing counter-disinformation strategies are in this context. The latter also served as a general test of strategies that scholars deem particularly effective in combating disinformation. To this end, we conducted a survey experiment of 618 officers from the Czech police and army.

Our results are generally positive; they reveal that the surveyed security personnel trust public broadcasters considerably more than disinformation portals. Comparing soldiers and police officers, we found that the former have slightly higher trust in public broadcasters, while the latter prefer commercial news. Both groups are also able to identify – to a large but not full extent – false messages. This finding is encouraging in its implication for national security as it reveals some resistance to mis- and disinformation among state security personnel in Czechia.

The results of the experiment show that both positive persuasion and generic prebunking are without any statistically significant effect when used within the Czech security communities. Among the members of the police force none of the treatments had any impact on perceived information accuracy. Similarly, among army officers, the treatments had no statistically significant effect on perceived information accuracy; however, the use of positive persuasive messaging makes a difference when police and army officers are compared. Our results thus indicate that inoculation against mis- and disinformation may matter for the ability of members of different security communities to assess the accuracy of information (whether it is false or biased), thus influencing how resistant they are to mis- and disinformation. However, the composition of our army sample may have affected these results as it includes a relatively higher representation of more educated and higher-ranked officers.

Other factors that may have affected our results include prior training concerning misinformation and the level of institutional trust (e.g. Roozenbeek et al. Citation2020). To the best of our knowledge, our study participants had not received any specific counter-disinformation training above what they would encounter in their regular professional training. However, given the differences between the police and army respondents, this is a possibility worth further investigating. While the Czech army and police enjoy similar levels of public trust (as of January 2024, 62% and 70% of Czechs trusted the army and the police, respectively) (STEM Citation2024), we have access to no available data on the levels of institutional trust among the surveyed security personnel. We thus leave it for further research.

There are very few studies on perceptions of closed security community members towards mis- and disinformation. A major obstacle is the difficulty of access, which prevented us from obtaining a larger sample for our survey experiment. The size of this sample is a considerable limitation of this study. Another limitation is our inability to generalise across security communities within and outside of Czechia since our sample is not representative. When combined, the Czech police and army have more than 67 thousand members (Policie ČR Citation2022, MO ČR Citation2023). To enhance the external validity of our study, it would be ideal to obtain a random sample from this pool. However, due to challenges with access to participants we had to rely on a convenience sample. Nonetheless, we have identified similarities between our sample and the known characteristics of the Czech security personnel. For example, one-fifth of our participants are women, which is similar to their representation in the Czech army and police (Armáda ČR Citation2019). At last, we do consider our sample adequate for our research objective, even though we acknowledge its convenient nature.

Another limitation of our findings pertains to our selection of false messages from Twitter. While each message was somehow false or misleading, some of them presented false claims as opinions, which may have affected our respondents.Footnote3 For example, one message states: “Some people are concerned with the prime minister’s broken English. But I think he doesn’t even need better English. At every meeting with his Western bosses, it’s enough for him to just say ‘Yes.’” This message is false in claiming that the Czech prime minister is working for Western actors, but it is presented as an opinion. Some respondents may have therefore reacted to the message for different reasons, but their answers should still reflect their perception of reality (which we were after). In general, people tend to struggle with distinguishing between facts and opinions and facts themselves can be interpreted in different ways (e.g. Merpert et al. Citation2018). From a counter-disinformation perspective, this is likely more important in fact-checking where fact-checkers need to be able to correctly distinguish (mis)information from opinion to be able to flag it (Walter and Salovich Citation2021).

The messages’ tone rather than content may have also affected our results. For example, it is possible that a negative evaluation by soldiers of one of the messages is due to its mocking tone when referring to the Czech Army:

So our little army with mercenaries wants to have a war? It is supported by the war government of the [expletive] coalition, which is driving the republic into a war … Fulfilling the role of a useful idiot, behind whom stands the USA … Go to hell with war!

Our findings, while limited, make both general and specific contributions to the existing knowledge. First, we test the effectiveness of those counter-disinformation strategies that are most frequently believed to be effective in lowering individual vulnerability to disinformation. Our findings do not confirm this effectiveness. Yet, because of our relatively small sample and the specificity of the sampled individuals (i.e. state security officials), our findings do not discredit the effectiveness of counter-disinformation strategies but highlight the need for caution when it comes to their applicability across different types of communities.

Second, our study also suggests that different counter-disinformation strategies may be effective to a different degree (or not effective at all, or even counter-productive) when applied to different groups of security personnel. These communities are not homogenous and just as we might expect different results and reactions to various stimuli and treatments from security forces when compared to the general public, it is reasonable to expect differences even within the security forces themselves, as indicated by our research. This underscores the necessity for comprehensive research and testing of these counter-disinformation strategies prior to their implementation. It is worth considering tailored approaches to the specific dynamics within different segments of the state security forces, whether in Czechia or elsewhere.

Human research participants

The requirement for approval from an independent ethics committee was not required by the authors’ home institution. Standard ethical procedures have been followed and relevant documentation is available upon request.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. We are also grateful to Dominik Stecula for his advice and insights on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials. Some data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Generally, misinformation is understood as false information, while disinformation is false information spread intentionally.

2 We can exclude the possibility that sex, age and education have any impact on our independent variables, i.e. our experimental treatments. All participants were randomly assigned to one of the three groups. Balance tests (available upon request) show that the groups do not significantly differ by any of the three variables.

3 Our key distinguishing characteristic between misinformation and opinion messages is verifiability, i.e. a false piece of information should be verifiable based on, for example, some historical data or statistics.

References

- Amazeen, M., Krishna, A., and Eschmann, R., 2022. Cutting the bunk: comparing the solo and aggregate effects of prebunking and debunking Covid-19 vaccine misinformation. Science communication, 44 (4), 387–417.

- Armáda ČR, 2019. Ženy v Armádě České republiky. Kolik jich je, jaké úkoly plní, jak jsou úspěšné? 18 September. Available from: https://www.czdefence.cz/clanek/zeny-v-armade-ceske-republiky-kolik-jich-je-jake-ukoly-plni-jak-jsou-uspesne

- Basol, M., et al., 2021. Towards psychological herd immunity: cross-cultural evidence for two prebunking interventions against COVID-19 misinformation. Big data & society, 8 (1): 1–18.

- Bjola, C., 2019. The ‘dark side’ of digital diplomacy: countering disinformation and propaganda. ARI 5/2019, 1–10.

- Boček, J., 2017. Studie: Důvěra v média je rekordně nízká. Nevěří jim mladí dospělí nebo voliči levice. 9 March. Available from: https://interaktivni.rozhlas.cz/duvera-mediim/www/

- Bor, A., et al., 2021. Fact-checking videos reduce belief in, but not the sharing of fake news on Twitter. Unpublished manuscript.

- Braddock, K., 2019. Vaccinating against hate: using attitudinal inoculation to confer resistance to persuasion by extremist propaganda. Terrorism and political violence, 34 (2): 1–23.

- Brashier, N. and Schacter, D.L., 2020. Aging in an era of fake news. Current directions in psychological science, 29 (3), 316–323.

- Chan, M., et al., 2017. Debunking: a meta-analysis of the psychological efficacy of messages countering misinformation. Psychological science, 28 (11): 1–16.

- Coddington, M., Molyneux, L., and Lawrence, R., 2014. Fact checking the campaign: how political reporters use Twitter to set the record straight (or not). The international journal of press/politics, 19 (4), 391–409.

- Compton, J., Wigley, S., and Samoilenko, S., 2021. Inoculation theory and public relations. Public relations review, 47 (5), 102116.

- Conway, L., III, et al., 2012. Does complex or simple rhetoric win elections? An integrative complexity analysis of U.S. presidential campaigns. Political psychology, 33 (5), 599–618.

- Curtis, J., 2021. Springing the ‘Tacitus trap’: countering Chinese state-sponsored disinformation. Small wars & insurgencies, 32 (2), 229–265.

- DeCook, J., 2018. Memes and symbolic violence: #proudboys and the use of memes for propaganda and the construction of collective identity. Learning, media and technology, 43 (4), 485–504.

- Dieckmann, N., et al., 2017. Seeing what you want to see: how imprecise uncertainty ranges enhance motivated reasoning. Risk analysis, 37 (3), 471–486.

- Dixit, P. and Max, R., 2018. How WhatsApp destroyed a village. BuzzFeed News, 10 September. Available from: https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/pranavdixit/whatsapp-destroyed-village-lynchings-rainpada-india

- Dowling, M. and Legrand, T., 2023. “I do not consent”: political legitimacy, misinformation, and the compliance challenge in Australia’s Covid-19 policy response. Policy and society, 42 (3), 319–333.

- Euronews, 2023. Pro-Russia disinformation floods Slovakia ahead of crucial parliamentary election. Euronews, 29 September. Available from: https://www.euronews.com/2023/09/29/pro-russia-disinformation-floods-slovakia-ahead-of-crucial-parliamentary-elections

- Euroskop, 2022. Čeští experti zveřejnili Desatero pro lepší porozumění a čelení dezinformacím. Euroskop, 21 February. Available from: https://euroskop.cz/2022/02/21/cesti-experti-zverejnili-desatero-pro-lepsi-porozumeni-a-celeni-dezinformacim/

- Fitzpatrick, M., Gill, R., and Giles, J., 2022. Information warfare: lessons in inoculation to disinformation. Parameters, 52 (1), 105–117.

- Fridkin, K., Kenney, P., and Wintersieck, A., 2015. Liar, liar, pants on fire: how fact-checking influences citizens’ reactions to negative advertising. Political communication, 32, 127–151.

- Greene, S., et al., 2021. Mapping fake news and disinformation in the Western Balkans and identifying ways to effectively counter them. The European Parliament's Committee on Foreign Affairs, EP/EXPO/AFET/FWC/2019-01/Lot1/R/01.

- Guan, T., Liu, T., and Randong, Y., 2021. Facing disinformation: five methods to counter conspiracy theories amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Media education research journal, 69, 67–78.

- Guess, A.M., Nagler, J., and Tucker, J., 2019. Less than you think: prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Science advances, 5 (1), eaau4586.

- Hellman, M. and Wagnsson, C., 2017. How can European states respond to Russian information warfare? An analytical framework. European security, 26 (2), 153–170.

- Houck, S., Repke, S., and Conway, L., 2017. Understanding what makes terrorist groups’ propaganda effective: an integrative complexity analysis of ISIL and Al Qaeda. Journal of policing, intelligence and counter terrorism, 12 (2), 105–118.

- Huang, H., 2018. The pathology of hard propaganda. The journal of politics, 80 (3), 1034–1038.

- Hunter, L., 2023. Social media, disinformation, and democracy: how different types of social media usage affect democracy cross-nationally. Democratization, 30 (6), 1040–1072.

- Kunda, Z., 1990. The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological bulletin, 108 (3), 480–498.

- Landon-Murray, M., Mujkic, E., and Nussbaum, B., 2019. Disinformation in contemporary U.S. foreign policy: impacts and ethics in an era of fake news, social media, and artificial intelligence. Public integrity, 21 (5), 512–522.

- Lessenski, M., 2022. How it started, how it is going: media literacy index 2022. Policy Brief 57. Available from: https://osis.bg/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/HowItStarted_MediaLiteracyIndex2022_ENG_.pdf

- Lewandowsky, S., 2021. Climate change disinformation and how to combat it. Annual review of public health, 42, 1–21.

- Lewandowsky, S. and van der Linden, S., 2021. Countering misinformation and fake news through inoculation and prebunking. European review of social psychology, 32 (2), 348–384.

- Liederkerke, A., 2016. The paramilitary phenomenon in Central and Eastern Europe. The Polish quarterly of international affairs, 25 (2), 25–34.

- Mareš, M., 2018. Radicalization in the armed forces: lessons from the Czech Republic and Germany in the Central European context. Vojenské Rozhledy, 27 (3), 25–36.

- Mareš, M., 2009. Hrozba politického extremismu z hlediska Ozbrojených sil České republiky. Vojenské rozhledy, 18 (2), 138–151.

- Margolin, D., Hannak, A., and Weber, I., 2018. Political fact-checking on Twitter: When do corrections have an effect? Political communication, 35, 196–219.

- Martin, J., 1971. Effectiveness of international propaganda. The annals of the American academy of political and social science, 398, 61–70.

- McGeehan, T., 2018. Countering Russian disinformation. Parameters, 48 (1), 49–57.

- McGuire, W., 1961. The effectiveness of supportive and refutational defenses in immunizing and restoring beliefs against persuasion. Sociometry, 24 (2), 184–197.

- McGuire, W., 1970. Vaccine for brainwash. Psychology today, 3 (9), 36–64.

- McGuire, W. and Papageorgis, D., 1962. Effectiveness of forewarning in developing resistance to persuasion. Public opinion quarterly, 26, 24–34.

- Merpert, A., et al., 2018. Is that even checkable? An experimental study in identifying checkable statements in political discourse. Communication research reports, 35 (1), 48–57.

- MO ČR, 2023. Vývoj skutečných počtů osob v resortu MO ČR v letech 1992–2022. 11 January. Available from: https://mocr.army.cz/dokumenty-a-legislativa/vyvoj-skutecnych-poctu-osob-v-resortu-mo-cr-v-letech-1992—2017-129653/

- Mozur, P., 2018. A genocide incited on Facebook, with posts from Myanmar’s military. The New York Times. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/15/technology/myanmar-facebook-genocide.html

- Nieminen, S. and Rapeli, L., 2019. Fighting misperceptions and doubting journalists’ objectivity: a review of fact-checking literature. Political studies review, 17 (3), 296–309.

- Nyhan, B. and Reifler, J., 2015. The effect of fact-checking on elites: a field experiment on U.S. state legislators. American journal of political science, 59 (3), 628–640.

- Pantazi, M., Hale, S., and Klein, O., 2021. Social and cognitive aspects of the vulnerability to political misinformation. Political psychology, 42 (S1), 267–304.

- Pfau, M., 1997. The inoculation model of resistance to influence. Progress in communication sciences, 13, 133–172.

- Policie ČR, 2022. Početní stavy příslušníků Policie České republiky. Available from: https://www.policie.cz/clanek/pocetni-stavy-prislusniku-policie-ceske-republiky.aspx

- Roozenbeek, J., van der Linden, S., and Nygren, T., 2020. Prebunking interventions based on the psychological theory of “inoculation” can reduce susceptibility to misinformation across cultures. The Harvard Kennedy school (HKS) misinformation review, 1 (2), 1–23.

- Roozenbeek, J., et al., 2020. Susceptibility to misinformation about COVID-19 around the world. Royal society open science, 7, 201199.

- Roozenbeek, J. and van der Linden, S., 2019. Fake news game confers psychological resistance against online misinformation. Palgrave communications, 5 (1), 65. doi:10.1057/s41599-019-0279-9.

- Saleh, N., et al., 2021. Active inoculation boosts attitudinal resistance against extremist persuasion techniques: a novel approach towards the prevention of violent extremism. Behavioural public policy, 8 (3): 1–24.

- Saurwein, F. and Spencer-Smith, Ch, 2020. Combating disinformation on social media: multilevel governance and distributed accountability in Europe. Digital journalism, 8 (6), 820–841.

- Sawano, T., et al., 2019. Combating ‘fake news’ and social stigma after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant incident—the importance of accurate longitudinal clinical data. QJM: An international journal of medicine, 112, 479–481.

- Schmitt, J., et al., 2018. Counter-messages as prevention or promotion of extremism?! The potential role of YouTube: recommendation algorithms. Journal of communication, 68, 780–808.

- Sinatra, G., Kienhues, D., and Hofer, B., 2014. Addressing challenges to public understanding of science: epistemic cognition, motivated reasoning, and conceptual change. Educational psychologist, 49 (2), 123–138.

- Slothuus, R. and de Vreese, C., 2010. Political parties, motivated reasoning, and issue framing effects. The journal of politics, 72 (3), 630–645.

- Stecula, D., Kuru, O., and Jamieson, K., 2020. How trust in experts and media use affect acceptance of common anti-vaccination claims. The Harvard Kennedy school misinformation review, 1 (1), 1–11.

- STEM, 2021. Velká část občanů uvěřila předvolebním útokům na konspiračních serverech, ukazuje nový průzkum. 16 December. Available from: https://www.stem.cz/velka-cast-obcanu-uverila-predvolebnim-utokum-na-konspiracnich-serverech-ukazuje-novy-pruzkum/

- STEM, 2024. Důvěra v armádu klesá, mezi mladými je však na vysokých číslech. 14 March. Available from: https://www.stem.cz/duvera-v-armadu-klesa-mezi-mladymi-je-vsak-na-vysokych-cislech/

- Stray, J., 2019. Institutional counter disinformation strategies in a networked democracy. In: Proceedings of WWW ‘19: the web conference (WWW ‘19), 13 May, San Francisco, USA. New York, NY: ACM, 1020–1025.

- Swire, B., et al., 2017. Processing political misinformation: comprehending the Trump phenomenon. Royal society open science, 4 (3), 160802.

- Tay, L.Q., et al., 2022. A comparison of prebunking and debunking interventions for implied versus explicit misinformation. British journal of psychology, 113, 591–607.

- Vasu, N., et al., 2018. Fake news: national security in the post-truth era. S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Policy Report. Available from: https://www.rsis.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/PR180313_Fake-News_WEB.pdf

- Walter, N., et al., 2020. Fact-checking: a meta-analysis of what works and for whom. Political communication, 37 (3), 350–375.

- Walter, N. and Salovich, N., 2021. Unchecked vs. uncheckable: how opinion-based claims can impede corrections of misinformation. Mass communication and society, 24 (4), 500–526.

- Wilson, S. and Wiysonge, C., 2020. Social media and vaccine hesitancy. BMJ global health, 5 (10), e004206.

- Wintersieck, A., 2017. Debating the truth: the impact of fact-checking during electoral debates. American politics research, 45 (2), 304–331.

- Zimmermann, F. and Kohring, M., 2020. Mistrust, disinforming news, and vote choice: a panel survey on the origins and consequences of believing disinformation in the 2017 German Parliamentary Election. Political communication, 37 (2), 215–237.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Experimental treatments

Appendix 2. Pre-treatment: false messages (in Czech)

Ukraine:

(Translation: A Ukrainian family of four is getting 90k [Czech crowns] a month to cover their living expenses. The prime minister’s advisor is suggesting that people find a second job. There is something rotten in this state.)

Schools:

(Translation: State schools don’t educate children. They are indoctrinating them with state propaganda. Mainstream media news is not informative. They brainwash people with lies and false reports. It’s all lies.)

Change:

(Translation: Are you happy? So people voted for change. And the change from years of peace, fundamentally prosperous years, is poverty and war. So thanks, little [expletive] coalition supporters. You are welcome … “The chief of the general staff, Řehka, warns: Czechia must prepare for a great war!”)

War:

(Translation: So our little army with mercenaries wants to have a war? It is supported by the war government of the [expletive]coalition, which is driving the republic into a war … Fulfilling the role of a useful idiot, behind whom stands the USA … Go to hell with war!)

The West:

(Translation: Some people are concerned with the prime minister’s broken English. But I think he doesn’t even need better English. At every meeting with his Western bosses, it’s enough for him to just say “Yes”.)

Appendix 3

Table A1. Agreement with biased anti-Ukrainian and anti-Russian statements.