Abstract

Ableist microaggressions are ubiquitous experiences for workers with an impairment, chronic illness or neurodivergence in the daily execution of their job. These (un)intended everyday (non)verbal negative messages based on disability status affectively disable people, momentarily and with lasting effects on mental health and positive identity. Past research provided either psychological accounts, locating the origins of microaggression in the minds of individuals, failing to highlight the role of an ableist society, or sociological accounts, stressing exclusionary structures and marginalising discourses, neglecting to fully account for the inner experience. This paper puts forward an alternative, combined account by empirically zooming in on three vignettes in work contexts. It contributes to expanding knowledge on subtle forms of ableism, showing the entanglement between material arrangements, negative co-worker affect, and their internalisation by the disabled worker. By locating the microaggression concept firmly in the structural oppression of ableist societies, we hope to inspire organisational programs aimed at detecting and preventing microaggressions. Finally, we prepare the ground for future research to look into even more subtle forms of disability-based discrimination present in everyday interactions.

Points of interest

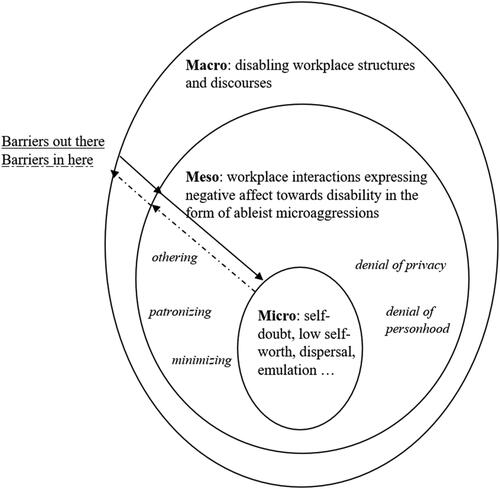

This study explores how barriers in the environment and negative interactions from colleagues impact individuals with disabilities, chronic illnesses, and neurodivergences in the workplace, leading them to internalise feelings of inadequacy and create their own barriers.

One way this happens is through small but hurtful actions known as ableist microaggressions, which can come from co-workers, supervisors, or others. These actions include making someone feel like an outsider, talking down to them, or disregarding their dignity or privacy.

The findings show that these microaggressions play a big role in maintaining unfair treatment of disabled individuals at work, even if they are not intended to be harmful.

It is crucial for managers to recognise and address these behaviours to create a more inclusive work environment.

Introduction

There is a growing awareness of disabled people’s rights, including their right to freely chosen work, yet progress in terms of employment rates and quality of jobs remains low (Geiger, Van Der Wel, and Tøge Citation2017). Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to have aggravated these inequalities (Jones Citation2022). The dominant approaches in management and organisation studies that aim to explain such inequalities focus on psychological processes of stereotyping and stigma (Beatty et al. Citation2019), showing a tendency to reduce the social phenomena of discrimination to personal properties located in the human mind rather than reproduced through practices (Janssens and Steyaert Citation2019). Important in this regard is ‘the social model of disability’, a paradigm that calls attention to the way disabilities are socially created through a maladapted society, putting a burden on top of people’s biological impairment and leading to unnecessary and preventable exclusion in every domain of life (Shakespeare Citation2006). Studies inspired by this model help turn the gaze of researchers and policymakers towards the role of structural, material barriers (Barnes and Mercer Citation2005; Van Laer, Jammaers, and Hoeven Citation2022), as well as discursive barriers equating disability to inability in the workplace (Jammaers Citation2023b; Williams and Mavin Citation2012). Although such sociological approaches are more attuned to historical power inequalities, they tend to neglect the more private, personal experiences as well as the role of emotion and affect in the lives of disabled people (Goodley Citation2014; Watermeyer and Swartz Citation2008). Yet, disabled people themselves have been calling out negative emotions and affect, such as condescension and sentimentality, as key contributors to structural hierarchies of oppression for decades (see, e.g. Pulrang Citation2022).

To bridge this conceptual gap and develop an understanding of ableism - the systematic designing of the world, its physical environment and social conventions ‘with a nondisabled person in mind’ (Goodley Citation2020, 78) - at the very nexus of social and emotional forces, this study investigates the role of affect in the workplace experience of disabled workers in waged and self-employment contexts. This role of affect in the workplace has received more attention in recent years following the ‘affective turn’ (Fotaki, Kenny, and Vachhani Citation2017), seeing affect as ‘a substrate of potential bodily responses, often autonomic responses, in excess of consciousness’ (Clough and Halley Citation2007, 2). In the field of management and organisation studies, such studies highlight affect as a device for managerial control in neoliberal capitalist societies. They bring to attention the affective experience of marginalised subjects beyond the mere level of representing subjective feelings (e.g. van Amsterdam, van Eck, and Meldgaard Kjær Citation2023). So far, however, these affective work experiences of disabled people, which we label as affective disablism when they concern negative, excluding behaviours and attitudes specifically directed towards disabled people, remain understudied. Feminist disability scholars, however, have constructed an understanding hereof as the hurt following daily structural exclusion and oppressive affective reactions and comments by others, which is likely to, at least partly, result in self-injury through internalisation of the idea that disability is inherently negative (Campbell Citation2009; Reeve Citation2002, Citation2013).

One form of affective disablism that has grasped the attention of practitioners and academics recently is microaggression (Conover, Israel, and Nylund-Gibson Citation2017; Lett, Tamaian, and Klest Citation2020; Kattari Citation2020; Washington, Birch, and Roberts Citation2020). Although predominantly used when referring to experiences of racial minorities, these ‘brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioural, and environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults to the target person or group’ (Sue et al. Citation2007, 273) are known to impact the daily lives of disabled people as well (Keller and Galgay Citation2010). In our paper, we stress the structural perspective on microaggressions that allows us to grasp how such ‘micro’ everyday interactions are not only embedded in but also perpetuate structural hierarchies of oppression (McClure and Rini Citation2020; McTernan Citation2018). Hence, the concept of microaggressions allows one to grasp how comments, gestures, and sociomaterial arrangements that might easily slip the attention do, in fact, perpetuate disablist societies. Yet no study, to the best of our knowledge, has explored the socially repeated phenomenon of ableist microaggression as a form of affective disablism in the workplace. In a time where overt forms of discrimination against disabled people are in decline due to improved legal awareness, the study of benevolent (Hein and Ansari Citation2022) and indirect and subtle forms of ableism (Jammaers Citation2023a) becomes key.

In an aim to understand the affective aspects of our society that culturally devalue some bodies and label them as lacking in contexts of work (Goodley Citation2014; Jammaers and Zanoni Citation2021), we scrutinise 51 interviews with waged and self-employed workers who identify as having a disability or chronic illness for instances of ableist microaggression. We zoom in on three ‘affect-rich’ vignettes to study in detail the process of ableist microaggression through a lens of affective disablism, paying close attention to the personal lived experience of the disabled person involved. In scrutinising these vignettes in-depth, we contribute both to existing knowledge on ableist microaggressions as well as diversity and inclusion in management and organisation studies in various ways. This study adds to the debate on subtle forms of ableism at work (Hein and Ansari Citation2022; Jammaers Citation2023a), demonstrating the entanglement between material arrangements, negative co-worker affect, and their internalisation by the disabled worker. By giving an in-depth account of the origins of ableist microaggressions at work, located in the ableist symbolic order, we offer a critical view of the concept that connects the structural aspects of affect with the structural aspects of microaggressions. Although the latter concept is sometimes dismissed as a managerial buzzword or euphemism, we believe that a structural take on the concept is a powerful tool for ‘identifying, disrupting and dismantling’ (Pérez Huber and Solorzano Citation2015, 297) the affective ableism that marginalises disabled people in the everyday context of work.

Theory

Affect as power in organisation studies

While there is a long tradition of taking emotions and moods into account when analysing organisational behaviour (Ashforth and Humphrey Citation1995; Menges and Kilduff Citation2015), leading to concepts like affective climate (Parke and Seo Citation2017) and affective culture (Ashkanasy and Härtel Citation2014), the turn to a more critical reading of affect in organisation and management studies is rather recent. Among the origins of this are discussions of affective labour (Negri Citation1999) and feminist studies of emotional work (Hochschild Citation1983). Accordingly, affect is conceptualised with a focus on power and on the affective experience of marginalised subjects. Questioning an individualistic understanding of affect, critical approaches ‘expand on individual-oriented, psychological and emotional conceptions by examining affect as transpersonal – an intensity or active force that is continually made and unmade’ (Keevers and Sykes Citation2016, 1647). Affect is thus ‘something other than subjective feelings’ as they account for bodily sensations that arise when encountering other humans or nonhumans as well as in encountering written or verbal texts (Katila, Kuismin, and Valtonen Citation2020, 1309–1313), circulating and thereby creating ‘affective economies’ (Ahmed Citation2004). Affect then works through and within the body, first occurring as a bodily sensation or ‘state of action-readiness’ and then being translated into an emotion that can be observed (Katila, Kuismin, and Valtonen Citation2020, 1313). Hence, we follow Ahmed’s (Citation2013, 4) urge ‘to reflect on the processes whereby “being emotional” comes to be seen as a characteristic of some bodies and not others’.

In this tradition of research, affect is shown to be readily used by organisational actors as ‘subtle device for governing individuals’ (Mühlhoff and Slaby Citation2018, 155). Such studies have demonstrated how workers come to monitor themselves through their affect (Carr and Kelan Citation2023, 262) and how affect is moulded to fit the individualisation, privatisation and financialisation of late capitalist societies (Clough et al. Citation2007; see also Waters-Lynch and Duff Citation2021). To grasp the complexity of how affects structure and are structured by social relations, researchers urge to look beyond the level of representation in order to understand how sensible forces structure organisations and work relations (Beyes and Steyaert Citation2012), as affect is crucial in orienting individuals and preparing not only their thoughts but also their actions (Keevers and Sykes Citation2016). An interesting example in this regard is a study by van Amsterdam, van Eck, and Meldgaard Kjær (Citation2023), which highlights how ‘the living, feeling, material, and sensate body’ is embedded in power relations (Fotaki and Pullen Citation2019, 6). They investigate how affects like shame ‘for not fitting in’ of self-identifying fat women employees become an essential ‘part of collective and affective histories of marginalisation’ (van Amsterdam, van Eck, and Meldgaard Kjær Citation2023, 593) in the workplace. Affect, however, does not only serve the reproduction of existing power relations. Feminist studies elaborating on the possibilities of affective solidarity engage with affects like ‘misery, rage, passion, pleasure’ that motivate a desire for transformation and eventually political action (Fleischmann et al. Citation2022; Hemmings Citation2012, 150; Vachhani and Pullen Citation2019).

From material and discursive toward affective disablism in the workplace

The ‘social model of disability’ gained adherence among activists and academics from the ‘70s onwards and has since been regarded as a revolutionary catalyst for transforming earlier understandings of disability as a medical abnormality and personal tragedy (Shakespeare Citation2006; Thomas Citation2007). Fuelled with a belief in disability as a social construction, scholars have looked for explanations for the socio-economic disadvantage of disabled people within the capitalist mode of work (Barnes and Mercer Citation2005), evolutions of capitalist societies (Harpur and Blanck Citation2020), national policies and legislation (Samoy and Waterplas Citation2012) and the educational system (Byrne Citation2022). On an organisational level, explanations have taken into account the materiality of the built business environment (Klinksiek, Jammaers, and Taskin Citation2023), corporate culture (Schur, Kruse, and Blanck Citation2013), and various Human Resources (HR) policies, including disability inclusion practices (Jammaers, Zanoni, and Williams Citation2021; Jammaers Citation2023b).

In line with the rise of more diverse, eclectic versions of the social model, as a consequence of an increasing number of criticisms about its overreliance on historical materialism (e.g. Goodley Citation2014; Thomas Citation2007), more studies started to investigate the role of language in the disablement of workers with impairments. Such studies examine, for instance, how unemployed disabled people are pushed even further away from employment in labour market policies (Holmqvist, Maravelias, and Skålén Citation2013; Scholz and Ingold Citation2021). Other studies point out the discursive constructions of people in paid work as ‘Other’, ‘incompetent’ and ‘unproductive’ workers (Dobusch Citation2017; Jammaers and Zanoni Citation2021; Mik-Meyer Citation2016) and the possibility for such negative assumptions by stakeholders persisting even in situations of self-employment (Jammaers and Zanoni Citation2020) or when people’s impairment clearly poses a business advantage (Jammaers and Williams Citation2023).

Building on the work of feminist disability scholars like Carol Thomas (1999, Citation2007), Donna Reeve (Citation2002, Citation2006) and Kafer (Citation2013), more attention is now being paid to the ‘barriers in here’ experienced by disabled people - albeit so far mostly outside the context of paid work (Goodley and Runswick-Cole Citation2011; Scholz and Ingold Citation2021). They bring to the foreground affective forms of disablism which stem from having to deal with structural exclusion on a daily basis and hurtful comments by others (Reeve Citation2013), including ‘representations that lead them to bless me, pity me, or refuse to see me altogether’ (Kafer Citation2013, 2). One result of negative affective reactions (e.g. fear, pity, disgust) towards disabled people can be the internalisation of negative beliefs leading to a negative sense of self, shame, low self-confidence and lack of psychological well-being (Thomas Citation2007; Hughes Citation2012; Sanmiquel-Molinero and Pujol-Tarrés Citation2020). When disabled people themselves reproduce the idea that disability is inherently negative, rather than realising that negative self-views are socially constructed by oppressive socio-economic systems, they unwillingly partake in the process of ableism (Campbell Citation2009). Common responses are distancing from other disabled people, as mixing is interpreted as a negative choice (also known as dispersal) or ‘passing’ by attempting to reach a state of near-able-bodiedness (also known as emulation) (ibid.). Both coping strategies, however, reinforce separation and leave hegemonic ideas about the superiority of so-called ‘able-bodied’ people unchallenged (ibid.). Using the terms ‘able-bodied’ and ‘disabled’ risks reconstructing a false and unhelpful binary (Shildrick Citation2009), yet we use them here to analytically investigate ableism. It should, however, be pointed out that many people who are identified as disabled by others do not themselves appropriate such a term, whilst some people who do identify as disabled may ‘pass’ as able-bodied or are even refused the label, for instance, by government administration.

Ableist microaggression as a structural phenomenon

The concept of ‘microaggression’ was first coined by Pierce (Citation1974) to describe racist ‘put-downs, done in an automatic, preconscious, or unconscious fashion’ and gained momentum in the 2000s through the work of Derald Wing Sue et al. (Citation2007). Rooted in psychology and psychiatry, current conceptualisations delimit what constitutes a microaggression based on the intent of the perpetrator (‘psychological accounts’) or they focus on the perception of the ‘victim’ (‘experiential accounts’) (McClure and Rini Citation2020). Since words like ‘victim’ may unwillingly contribute to the act of victimisation, we use them with caution (Alcoff and Gray Citation1993; Goodley Citation2003) in the context of microaggressions. Although the repeated, often well-intended messages that constitute microaggressions may seem harmless or trivial to the outsider, they bring real harm to the target and are ubiquitous across their daily working life (Kim and Meister Citation2023; Lui and Quezada Citation2019; Washington, Birch, and Roberts Citation2020), especially in an era where overt displays of discrimination have become less tolerated due to legislation.

While early accounts focused on racism, later developments started to include various axes of oppression (Pérez Huber and Solorzano Citation2015). Accordingly, also ‘ableist microaggressions’ were advanced more recently, and scales have been developed to highlight the negative impact on mental health that small and implicit interactions involving ableism can have on disabled people (Conover, Israel, and Nylund-Gibson Citation2017; Kattari Citation2020). To illustrate ableist microaggressions in a work context, Keller and Galgay (Citation2010) give the autobiographical example of a business meeting between a long-established group of co-workers and a new administrator who extends his hand to a blind co-worker with no one stepping in except for someone whispering ‘he is blind’, leaving the blind person embarrassed and upset. They reason that such a ‘subtle act of insensitivity’ affects disabled people severely (Keller and Galgay Citation2010, 243), as it operates from an unconscious ableist worldview assuming disabled people are cognitively limited, helpless or childlike. The co-workers’ silence alludes to denial and invalidation of disabled people’s experiential reality whilst revealing their discomfort with disability and a preference to keep it out of sight (Keller and Galgay Citation2010). Similarly, Kafer (Citation2013) explains the violence done by casting disability as a pitiable misfortune, as she recounts a professor dismissing her paper proposal on disability, patting her on the arm and urging her to ‘heal’ and overcome instead of researching disability. More recently, Zeyen and Branzei (Citation2023, 779) demonstrate how resisting mundane micro-aggressions took ‘so much effort and energy that it often culminated in body breakdowns’. These seemingly small microinequities should thus be seen as everyday (hidden) messages that reinforce the status quo of ableism when left unaddressed.

Accordingly, in our approach, we aim at advancing a structural understanding of microaggressions (McClure and Rini Citation2020) that highlights that the ‘micro’ in microaggression only refers to their often subtle and unnoticeable character, but neither to their ‘micro’ impact nor to their decontextualisation. In contrast – and similar to the above discussion on the social understanding of affect – microaggressions must be understood as both embedded in and reproducing oppressive social structures (see Pérez Huber and Solorzano Citation2015 for a discussion focussing on racism). So instead of seeing an individualised ‘mental state’ of either the ‘perpetrators’ or ‘victims’ of microaggressions, our paper explores their role in maintaining ableist societies. Microaggressions can, thus, be seen as having a ‘particular functional role in oppressive social structures’ as they ‘remind marginalised people of their vulnerable position in social hierarchies’ (McClure and Rini Citation2020, 6). Even if they position individuals in established hierarchies of oppression, microaggressions are often hard to identify, and thus hard to combat, what McTernan (Citation2018) calls the ‘innocuousness of microaggressions’.

Hence, there is an urgent practical need for research to extend knowledge about social oppression as expressed through psycho-emotional barriers at the private – yet social – level (Watermeyer Citation2012). Such affective disablism should not be reduced to individual cognition or emotion, as this ignores ‘the cultural investments within the affects of disability and disablism’ (Goodley Citation2014, 64) or, as we would add, with ableist microaggressions in this regard. In this sense, being depressed or feeling devalued is never simply the result of an impairment, but also of how such an impairment is embodied and materialised in a specific socio-cultural space (Goodley Citation2014) and how subtle interactions with both other individuals as well as the socio-material environment structure this state. To enhance the social understanding of everyday affective disablism, we reflect on experiences of ableist microaggressions at work through a qualitative lens.

Method

This study is part of a larger project invested in researching ableist structures of work. The context of the study is Flanders (the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium), a region for which the employment rate of disabled people stood at 49.2% in 2021, which is low compared to the 80.2% employment rate of non-disabled people in the same year. The first author conducted 51 interviews with people in a wide variety of service jobs, both in the context of self- and waged employment, with a wide variety of impairments, chronic illnesses and neurodivergences. The term neurodivergence is used to refer to cognitive profiles that do not conform to the ‘neurotypical’ norm, meaning the brain functions in a non-standard way, encompassing conditions such as ADHD, autism, dyspraxia, or dyslexia (Singer Citation1999). The criteria for inclusion of respondents were that they self-identified as an employee or business owner with a disability, chronic illness or neurodivergence. Sampling occurred in a variety of ways, from targeted spreads of call-for-respondents letters inside disability-friendly organisations, to snowball sampling and social media posts. The average length of interviews was 66 min. The interviews were recorded with the permission of the respondents and transcribed ‘word-by-word’, with attention to expressed emotions from both interviewer and interviewee. This could, for instance, mean that moments of ‘unease’ experienced by the interviewer or interviewee materialised through a range of displayed emotions (crying, laughter, …) and less tangible affect (awkward silence, difficulties in finding the right words, …) were documented in the transcription process. In addition, the first author kept a notebook with afterthoughts and general feelings about the interview, which she systematically updated after each interview had taken place.

For the purpose of this study, the 51 interviews were selectively coded (Bougie and Sekaran Citation2019), loosely following the items identified in the ‘ableist microaggression scale’ of Conover, Israel, and Nylund-Gibson (Citation2017) and Keller and Galgay (Citation2010). Most commonly identified microaggressions in the dataset were well-intended forms of ‘helplessness’ (e.g. admiration related to coming to work every day despite their disability, for their positive mindset ‘in the face of misfortune’, for their ability to speak, etc.) and ‘otherisation’ (being stared at by customers, disbelief when seeing a disabled manager or entrepreneur) often containing elements of surprise that reveal hidden messages of low societal expectations about disabled people. As common were indications of ‘minimisation’ of disabled workers’ health-related needs by co-workers, thereby nullifying their lived embodied realities, an issue well documented in the existing literature as ‘denial of reasonable accommodation’ (Robert and Harlan Citation2006; Jammaers Citation2023b). Although ‘denial of personhood’ and ‘denial of privacy’ also arose from the interviews, they were less common forms of microaggressions in our sample (yet see Lourens and Zeyen Citation2024 for an interesting case on the latter).

To describe the process of how ableist microaggressions lead to affective disablism in more detail, we zoom in on three interviews that were rich in ‘affective character’, giving a lively description and anecdotal evidence of microaggressions. We thus made a conscious decision to put a magnifying glass on a few cases to do justice to the complexity of the phenomenon under study. Criteria that were used in the selection of the three interviews, besides their affective character, were the type of impairment (visible/invisible, physical/cognitive, acquired/congenital), age (beginning, mid and end of career), gender (male/female/non-binary), employment setting (public administration, self-employed, private creative sector), and type of microaggression (helplessness/otherisation/minimisation/privacy denial/personhood denial). For the purpose of analytical clarity, we focus here on ableist microaggressions that are not so subtle nor well-intended, as these were easier to identify and deconstruct. The three interviews were turned into three summarising vignettes (which were translated from Dutch to English) to document the hostile, ableist normativity in the context of work and illustrate how people with impairments, chronic illnesses or neurodivergences become disabled through affect. The names used in the finding section are pseudonyms to safeguard the anonymity of respondents. via email respondents were provided with the opportunity to verify how their vignette would be used. As the third respondent withdrew their participation at a very late stage in the publication process, a fictitious persona and vignette were created, inspired by local media events of 2022, which dealt with the same type of microaggression described by the original respondent, and carried the same core message.

Findings

In what follows, we illustrate the process of affective disablement in the workplace through ableist microaggression (see for a schematic representation) based on the vignettes of three respondents. Their narratives stood out as particularly interesting because of their overall affect-rich character, putting a magnifying glass on how psychological ‘barriers in here’ work and are imbricated with socio-material ‘barriers out there’, potentially limiting the careers of disabled people.

Figure 1. Schematic overview of the process of affective disablement through ableist micro-aggression in the workplace, potentially limiting people’s careers.

Vignette 1: coming to terms with diminished productivity as a person with physical impairments

In the first vignette, Marjan explains the difficulties she experiences at the end of her career in coming to terms with her diminished health and abilities. Although Marjan had been occasionally experiencing health-related problems due to hearing loss and Axial Spondyloarthritis, a painful, chronic arthritis that mainly affects the joints of the spine, it was not until the age of 55, when diagnosed with fibromyalgia, that her doctor advised her to request accommodations in her work environment. Having worked for the same employer for over 35 years in multiple different jobs, Marjan assured us she knew the business well and took pride in all of the different projects she had instigated for her employer. Yet, the evidence of such positive work-related affect was missing from the rest of the interview, which soon became overshadowed by feelings of grief and loss, as Marjan was unable to see what she had left to offer to the organisation due to her deteriorating condition. The interview was paused on numerous occasions because of the emotional state Marjan was in whilst narrating her career path. Consider the following excerpt, which reveals how increasing pressures for efficiency inside the organisation coincide with a worsening self-view, related to the affect surrounding accommodation:

We work in teams but this organisation is changing so much, new open office plans, people retiring without being replaced, working more efficiently, savings, lots of change, lots of people being relocated, subsidiaries closing, I mean it’s a great source of tension within the teams… I get to leave work fifteen minutes earlier sometimes if I need to get physiotherapy, and I don’t have to sit at the front desk or take minutes during meetings. I find for myself that I am not valuable to the team, and my boss also complains about it, she says “you have your adjusted work package, but for the team, I mean, the loss in productivity for the team is not substituted”. So I have to take on less work, but it’s at the cost of my team.

I am left with so much guilt, so much! And there is a lack of understanding. At one point I asked my supervisor if people knew why I was exempt from such tasks, I mean I don’t want to shout it around, what I’ve got, I have my pride, but I feel like others don’t understand the necessity of it if they aren’t told.

A co-worker of ours got cancer and had been out of the office for treatment for a long time. One day, someone said “you know, I’m pretty sure that she is exaggerating this cancer thing to not have to come in for work”. Such a reaction you know… it leaves me… it makes me think “What must these people say about me behind my back?” you know… It really hurt me. It makes me very, very angry as well. It was such a confronting experience…

I used to be so driven, very driven. I would work on weekends, just to ensure the program would run smoothly. I have been working here my whole life, have taken so much initiative, have helped build so many different projects for the company. But that ambition is gone, I’ve given up. And that is frustrating for the co-workers, because you have to be so flexible around here, take on additional tasks when someone is ill. And I used to do all that, but now I can’t. I systematically say ‘no, I can’t’. And there is no understanding of it. I am left with so much guilt. I want to retire really, really! All I do is survive. There is no pleasure anymore in this work, … just the feeling of decrease… I used to be such a hard-working person, and I have to learn to accept it, but no one else is accepting it here, and it’s hard, it’s oh so hard [starts crying].

Vignette 2: being bullied into self-employment as a neuro-diverse person

The second vignette presents the story of Bert, who self-identifies as a neuro-diverse entrepreneur. Already as a young boy, Bert experienced difficulties in school since teachers interpreted his inability to engage with certain tasks as a problem of willpower and obedience. After obtaining a university degree and doing some job-hopping in the finance sector, he was headhunted to work for a prestigious asset management company. He recounts how, in all these workplaces, he experienced a mismatch between employer expectations and his ‘different’ abilities, causing difficulties as a waged employee:

My brain works in a particular way, I can do some things very well, like forecast the future, shape the future, I can stand tall in the biggest chaos, but what I can’t do is plan and administrate, for that I need team members to support me. I am a hammer, and without nails or the hands of a good carpenter, I’m worth nothing. This is essentially why I had to leave my previous employers; they would not provide me with the circumstances and support that I needed to stay above water. I can still cry over this now. […] Whenever I tried to explain that I could not handle administration, I got a response like “Do you think you are better than someone else? Everyone has to clean up their own mess around here.”

I never had any guidance, any help, not at home and not in the workplace. I would have benefitted from a professional buddy, someone to pour my heart out from time to time, who knows you, knows the way your brain works and does not think of you as ‘the annoying guy’ in the office. […] At one point, my boss said, “stop telling people you have ADHD, you’re making me and my company look bad”.

One day Marc [HR manager] told me we needed to talk. He reassured me that I need not to be afraid, and that they were not going to fire me. He took me out for lunch and said he wanted to tell me here [restaurant, outside the office] because it might hit me hard. He said, “Geoffrey [the boss] would like you to work from home from now on whenever he is in the building”. [long silence]

I didn’t even dare tell my friends about this, it was so embarrassing. I thought to myself, what is this? It was as if I was hit with a sledgehammer. And the more I could sense that my boss disliked me, the longer I would continue working in the evenings to try to do good. […] But then things quickly got worse because at home, I was going nuts, I am such a social person, and I need others around me. So basically, they were happy to have me for my disharmonic intelligence profile, the good parts of it, but were not willing to accept the negative ones. They did not even bother to deal with it, it was like: “Fuck off with your personality, but stay here with your skills”. I did for a short while, but then I told Benny and Eric [current business partners], do whatever you guys want but I’m resigning and starting my own business. They [management] were furious, furious!

In sum, Bert is made to feel abnormal or othered since childhood, an ableist microaggression that was closely entangled with the lack of recognition and support in his schooling system. The othering process continues on in his professional career, where he is refused an adjusted work package and support buddy. The ableist microaggression of being denied personhood becomes especially tangible when he is expelled from working in the building and spatially ‘zoned’ (Jammaers Citation2023a; Van Laer, Jammaers, and Hoeven Citation2022) which initiates an urge for emulation within Bert (Campbell Citation2009). Indeed, by working late in the evenings, he tries to convince his boss of his ‘good intentions’ and restore an image of wholeness. Yet taking up an identity ‘other than his own’ becomes unattainable in the long run and the only way to put a stop to the affective disablement is by starting his own business on his own terms (Jammaers and Zanoni Citation2020).

Vignette 3: confronting the ableist gaze through pride as a disabled actor

The third vignette is a fictitious account based on media coverage. Derek, an actor born with spina bifida openly resists the way disabled people are still predominantly stereotyped as passive charity cases in the media. He explained why this is upsetting for him:

There was one particular TV show that made me sick to my stomach. It was a dating show for disabled people, and they were only allowed to date other disabled peers! Hideous! How do I explain to my three children that the people in this show could only date look-a-likes, but I somehow ‘managed’ to marry their [non-disabled] mother? What message does that send to young children?

For a long time, I was silently complaining, to my wife only, about the passive, silly roles I was being offered. I never spoke up, because I always feared burning my chances for jobs in the cultural sector if I put down my foot. But the open letter of public figure X resonated with me. I just thought, fuck this, why would I put up with it any longer as a grown man? Disabled people have real jobs in everyday life too, they are not solely living off unemployment benefits and wasting away their days being dependent on care facilities. So why can’t I be asked to play a pharmacist or a prime minister or whatever?

I love performing in theatre [as opposed to in TV shows], because when you play a role as a disabled actor, you don’t have to explain yourself or give the audience a ‘warning in advance’. On the theatre stage, the sky is the limit, you just perform and everyone is on board, whatever the storyline or the body of the person playing it.

Casting directors will be surprised to see me turn up to a casting in a wheelchair. ‘Why did you not tell us up front?’ It’s about confronting them with their own prejudice and then showing them a different side to disability they had never considered before. As a disabled person, I can be authentic and vulnerable, and this is a valued characteristic of actors. At the same time, I think representation on the screen is important and so if that means I still have to put away my pride every now and then, I’ll do it. Representation is the first step and we are long not there yet.

Discussion and conclusion

This study aimed to better understand how people become affectively disabled in the workplace through incidents of ableist microaggression. Although the concept of microaggression has been rightfully questioned by critical scholars as a means for researchers and managers to disassociate inequality from its historical context and depoliticise issues of institutionalised -isms (racism, sexism, ableism, classism, etc.) (see, e.g. McClure and Rini Citation2020; Pérez Huber and Solorzano Citation2015), we believe that a structural perspective on microaggressions as applied in our article has merit to identify and name subtle, sometimes even well-intended forms of affective disablism - although the examples shown are hardly well-intended. With this paper, we try to show that, even if microaggressions occur at the interpersonal level, their effects are far from micro because these ableist slurs and incivilities are embedded into the macro-structures of an ableist society that structurally equates impairment, chronic illness and neurodivergence to inferiority and fails to recognise the value of otherness. Indeed, they are often pardoned and go by almost unnoticed. Yet, through endless repetition, they impact the targeted individual severely on an affective level, as our vignettes show, leading to shame, doubt and a reduced sense of self worth.

Since the first qualitative study by Keller and Galgay (Citation2010), scholars in the rehabilitation field have worked on developing and validating a measurement scale for ableist microaggression (Conover, Israel, and Nylund-Gibson Citation2017). Such studies revealed how microaggressions occur across disability type and correlate with several negative mental health outcomes, such as anxiety and depression (Kattari Citation2020). Our study adds to this knowledge a deeper understanding of their origins and nature in the context of work. Zooming in on our vignettes, we discovered how disabled people became affectively disabled through various (in)direct, (un)intentional, (non)verbal acts (Conover, Israel, and Nylund-Gibson Citation2017; Sue et al. Citation2007) such as co-workers’ indirect gossip about ‘faking’, being avoided by one’s boss, or being offered the same stereotypical roles over and over again by recruitment agencies. Such acts carry with them the message that the labouring bodyminds of disabled people are lacking. This allowed us to firmly locate the origins of ableist microaggression and the resulting affective disablism in the norm of able-bodied/minded workers as ideal workers, fuelling an expectation of hyper-ablebodiedness in different work contexts that disabled people themselves may appropriate and reproduce (Goodley Citation2014). For the purpose of analytical clarity, the vignettes highlighted forms of ableist microaggression that were not so subtle nor well-intended. Future research should further extend knowledge on more subtle and benevolent forms of work-related ableist microaggressions through innovative methodological designs like diary studies or setting up longitudinal field experiments to find successful ways for managers and employees to eliminate them.

Next, our analysis showed how disabled workers’ experience of negative affect from co-workers is intimately tied to material arrangements, an interplay that is often neglected in psychological and sociological accounts of workplace disablism. Marjan’s co-workers openly questioned the value of disabled workers by dismissing the authenticity of their co-worker’s illness, whilst her employer materially individualised the ‘burden of disability’ by not providing substitution for her reduced productivity in the team. Bert’s supervisor sent out a clear message about his social undesirability and physically banned him from entering the office while the boss was present. Derek worked hard to avoid disablism in the workplace by refusing to play demeaning roles that casting agencies offered in abundance. The negative workplace affect afforded to disabled workers was sustained through the denial of appropriate reasonable accommodation (Robert and Harlan Citation2006), spatial restrictions (Jammaers Citation2023a; Van Laer, Jammaers, and Hoeven Citation2022) and stereotypical roles (Jammaers and Ybema Citation2023). In such a business context, rife with ideals of bodily perfection and productivity (Johansson, Tienari, and Valtonen Citation2017; Riach and Cutcher Citation2014), microaggressions systematically placed disabled employees in the position of ‘imperfect others’ at the very intersection of affective and socio-material relations. Yet, pride served as a powerful affect to question the ableist norm, as seen in the vignette of Derek, which illustrates how disabled people can become conscious of their risk of being turned into ‘a receptacle of the emotional excess of others’ (Hughes et al. Citation2005, 267) and actively refuse the role of ‘dustbin of disavowal’ (Shakespeare Citation1994, 283) in their workplace.

Looking at disablism in the workplace using a framework that combines affective disablism and microaggressions, our analysis exhibited how – more or less – subtle acts and sociomaterial arrangements all add up to feeling less valued as a worker, which fuels an affective disablism as a ‘barrier in here’ (Goodley and Runswick-Cole Citation2011; Scholz and Ingold Citation2021). Yet, focusing on a structural understanding of microaggressions (McClure and Rini Citation2020), our analysis exposed that these microinequities do not happen in a ‘social vacuum’. On the contrary, they are embedded in existing hierarchies of oppression and inclusion – and they perpetuate them in, often unnoticed, everyday situations. Hence, by showing their ‘functional role’, our analysis demonstrated how, on the individual level, microaggressions are internalised and add up to affective disablism, but they have severe effects on the social positioning of these disabled people. For people in the work-life – both managers and colleagues – this means that rather than looking for solutions in the mental state of perpetrators of microaggressions or ‘fixing the victim’ of microaggressions, the structural aspects of microaggressions must be addressed. In the realm of work, our analysis has shown that a high workload and a hyper-fixation on productivity are key aspects that structure how disabled people can be seen at work. Accordingly, questions of distribution of work, the role of work in life and the centrality of capitalist surplus value must be addressed.

To end, we thank our respondents for sharing their affect-rich stories with us. Although we normally send respondents the published version of a paper and a written or spoken summary in layman’s words, the reviewers of this journal made us realise this falls short of an emancipatory research method as it does not provide any real opportunity to make changes. In light of this concern, we re-contacted the three respondents during the revisions process of this paper and shared with them a brief summary of the theoretical framework and how their vignette was written up. We were however unable to reach Marjan who retired, despite numerous attempts. Bert was happy with ‘the way we were perfectly able to capture his sentiments’. Finally, the third vignette was replaced by a fictitious account inspired by recent media events, as the original respondent’s booking agent informed us they wanted to ‘withdraw from the study, as the interview had become outdated’. We see the latter as evidence of the hurt that reliving microaggressions can cause and as a reminder of the responsibility we have as scholars to critique ableist structures in society, without further damaging the individuals burdened by them. Hence, we opted to replace their account with a similar one that was covered in the media to represent the important aspect of disability pride when facing microaggressions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahmed, S. 2004. “Affective Economies.” Social Text 22 (2): 117–139. https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-22-2_79-117.

- Ahmed, S. 2013. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. London and New York: Routledge.

- Alcoff, L., and L. Gray. 1993. “Survivor Discourse: Transgression or Recuperation?” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 18 (2): 260–290. https://doi.org/10.1086/494793.

- Ashforth, B. E., and R. H. Humphrey. 1995. “Emotion in the Workplace: A Reappraisal.” Human Relations 48 (2): 97–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679504800201.

- Ashkanasy, N. M., and C. E. J. Härtel. 2014. “Positive and Negative Affective Climate and Culture: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.” In The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Climate and Culture, edited by B. Schneider, K. M. Barbera, 136–152. London: Oxford University Press.

- Barnes, C., and G. Mercer. 2005. “Disability Work and Welfare: Challenging the Social Exclusion of Disabled People.” Work Employment and Society 19 (3): 527–545. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017005055669.

- Beatty, J. E., D. C. Baldridge, S. A. Boehm, M. Kulkarni, and A. J. Colella. 2019. “On the Treatment of Persons with Disabilities in Organizations: A Review and Research Agenda.” Human Resource Management 58 (2): 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21940.

- Beyes, T., and C. Steyaert. 2012. “Spacing Organization: Non-Representational Theory and Performing Organizational Space.” Organization 19 (1): 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508411401946.

- Black, R. S., and L. Pretes. 2007. “Victims and Victors: Representation of Physical Disability on the Silver Screen.” Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities 32 (1): 66–83. https://doi.org/10.2511/rpsd.32.1.66.

- Bougie, R., and U. Sekaran. 2019. Research Methods for Business: A Skill Building Approach. Chichester: Wiley.

- Byrne, B. 2022. “How Inclusive is the Right to Inclusive Education? An Assessment of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities’ Concluding Observations.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 26 (3): 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1651411.

- Campbell, F. K. 2009. Contours of Ableism: The Production of Disability and Abledness. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Carr, M., and E. K. Kelan. 2023. “Between Consumption, Accumulation and Precarity: The Psychic and Affective Practices of the Female Neoliberal Spiritual Subject.” Human Relations 76 (2): 258–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267211058577.

- Clough, P. T., G. Goldberg, R. Schiff, A. Weeks, and C. Willse. 2007. “Notes towards a Theory of Affect-Itself.” Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organization 7 (1): 60–77.

- Clough, P. T., and J. Halley. 2007. The Affective Turn: Theorizing the Social. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Conover, K. J., T. Israel, and K. Nylund-Gibson. 2017. “Development and Validation of the Ableist Microaggressions Scale.” The Counseling Psychologist 45 (4): 570–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000017715317.

- Dobusch, L. 2017. “Gender, Dis-/Ability and Diversity Management: Unequal Dynamics of Inclusion?” Gender, Work & Organization 24 (5): 487–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12159.

- Dolmage, J. T. 2017. Academic Ableism: Disability and Higher Education. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Fleischmann, A., L. Holck, H. Liu, S. L. Muhr, and A. Murgia. 2022. “Organizing Solidarity in Difference: Challenges, Achievements, and Emerging Imaginaries.” Organization 29 (2): 233–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/13505084221083907.

- Fotaki, M., and A. Pullen. 2019. Diversity, Affect and Embodiment in Organizing. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fotaki, M., K. Kenny, and S. J. Vachhani. 2017. “Thinking Critically about Affect in Organization Studies: Why It Matters.” Organization 24 (1): 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508416668192.

- Geiger, B. B., K. A. Van Der Wel, and A. G. Tøge. 2017. “Success and Failure in Narrowing the Disability Employment Gap: Comparing Levels and Trends across Europe 2002–2014.” BMC Public Health 17 (1): 928. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4938-8.

- Goodley, D. 2014. Dis/Ability Studies. London and New York: Routledge.

- Goodley, D. 2020. Disability and Other Human Questions. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Goodley, D., and K. Runswick-Cole. 2011. “The Violence of Disablism.” Sociology of Health & Illness 33 (4): 602–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01302.x.

- Goodley, D. 2003. “Against a Politics of Victimisation: Disability Culture and Self-Advocates with Learning Difficulties.” In Disability, Culture and Identity, edited by S. Riddell, N. Watson, 105–130. London and New York: Routledge.

- Harpur, P., and P. Blanck. 2020. “Gig Workers with Disabilities: Opportunities, Challenges, and Regulatory Response.” Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation 30 (4): 511–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-020-09937-4.

- Hein, P. H., and S. Ansari. 2022. “From Sheltered to Included: The Emancipation of Disabled Workers from Benevolent Marginalization.” Academy of Management Journal 65 (3): 749–783. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2020.1689.

- Hemmings, C. 2012. “Affective Solidarity: Feminist Reflexivity and Political Transformation.” Feminist Theory 13 (2): 147–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700112442643.

- Hochschild, A. R. 1983. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. London: University of California.

- Holmqvist, M., C. Maravelias, and P. Skålén. 2013. “Identity Regulation in Neo-Liberal Societies: Constructing the ‘Occupationally Disabled’ Individual.” Organization 20 (2): 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508412438704.

- Hughes, B. 2012. “Fear, Pity and Disgust: Emotions and the Non-Disabled Imaginary.” In Routledge Handbook of Disability Studies, edited by N. Watson, A. Roulstone, C. Thomas, 67–78. London: Routledge.

- Hughes, B., L. McKie, D. Hopkins, and N. Watson. 2005. “Love’s Labours Lost? Feminism, the Disabled People’s Movement and an Ethic of Care.” Sociology 39 (2): 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038505050538.

- Jammaers, E., P. Zanoni, and J. Williams. 2021. “Not All Fish Are Equal: A Bourdieuan Analysis of Ableism in a Financial Services Company.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 32 (11): 2519–2544. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1588348.

- Jammaers, E. 2023a. “On Ableism and Anthropocentrism: A Canine Perspective on the Workplace Inclusion of Disabled People.” Human Relations 76 (2): 233–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267211057549.

- Jammaers, E. 2023b. “Theorizing Discursive Resistance to Organizational Ethics of Care through a Multi-Stakeholder Perspective on Disability Inclusion Practices.” Journal of Business Ethics 183 (2): 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05079-0.

- Jammaers, E., and J. Williams. 2023. “Turning Disability into a Business: Disabled Entrepreneurs’ Anomalous Bodily Capital.” Organization 30 (5): 981–1003. https://doi.org/10.1177/13505084211032312.

- Jammaers, E., and P. Zanoni. 2021. “The Identity Regulation of Disabled Employees: Unveiling the ‘Varieties of Ableism’ in Employers’ Socio-Ideological Control.” Organization Studies 42 (3): 429–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840619900292.

- Jammaers, E., and P. Zanoni. 2020. “Unexpected Entrepreneurs: The Identity Work of Entrepreneurs with Disabilities.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 32 (9-10): 879–898. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2020.1842913.

- Jammaers, E., and S. Ybema. 2023. “Oddity as Commodity? The Body as Symbolic Resource for Other-Defying Identity Work.” Organization Studies 44 (5): 785–805. https://doi.org/10.1177/01708406221077770.

- Janssens, M., and C. Steyaert. 2019. “A Practice-Based Theory of Diversity: Respecifying (in) Equality in Organizations.” Academy of Management Review 44 (3): 518–537. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2017.0062.

- Johansson, J., J. Tienari, and A. Valtonen. 2017. “The Body, Identity and Gender in Managerial Athleticism.” Human Relations 70 (9): 1141–1167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716685161.

- Jones, M. 2022. “COVID-19 and the Labour Market Outcomes of Disabled People in the UK.” Social Science & Medicine 292: 114637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114637.

- Kafer, A. 2013. Feminist, Queer, Crip. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

- Katila, S., A. Kuismin, and A. Valtonen. 2020. “Becoming Upbeat: Learning the Affecto-Rhythmic Order of Organizational Practices.” Human Relations 73 (9): 1308–1330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719867753.

- Kattari, S. K. 2020. “Ableist Microaggressions and the Mental Health of Disabled Adults.” Community Mental Health Journal 56 (6): 1170–1179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00615-6.

- Keevers, L., and C. Sykes. 2016. “Food and Music Matters: Affective Relations and Practices in Social Justice Organizations.” Human Relations 69 (8): 1643–1668. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715621368.

- Keller, R. M., and C. E. Galgay. 2010. “Microaggressive Experiences of People with Disabilities.” In Microaggressions and Marginality: Manifestation, Dynamics, and Impact, edited by D. W. Sue, 241–267. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.

- Kim, J. Y., and A. Meister. 2023. “Microaggressions, Interrupted: The Experience and Effects of Gender Microaggressions for Women in STEM.” Journal of Business Ethics 185 (3): 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05203-0.

- Klinksiek, I. D., E. Jammaers, and L. Taskin. 2023. “A Framework for Disability in the New Ways of Working.” Human Resource Management Review 33 (2): 100954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2023.100954.

- Lett, K., A. Tamaian, and B. Klest. 2020. “Impact of Ableist Microaggressions on University Students with Self-Identified Disabilities.” Disability & Society 35 (9): 1441–1456. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1680344.

- Lourens, H., and A. Zeyen. 2024. “Experiences within Pharmacies: Reflections of Persons with Visual Impairment in South Africa.” Disability & Society 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2024.2328587.

- Lui, P., and L. Quezada. 2019. “Associations between Microaggression and Adjustment Outcomes: A Meta-Analytic and Narrative Review.” Psychological Bulletin 145 (1): 45–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000172.

- McClure, E., and R. Rini. 2020. “Microaggression: Conceptual and Scientific Issues.” Philosophy Compass 15 (4): 11. https://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12659.

- McTernan, E. 2018. “Microaggressions, Equality, and Social Practices.” Journal of Political Philosophy 26 (3): 261–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopp.12150.

- Menges, J., and M. Kilduff. 2015. “Group Emotions: Cutting the Gordian Knots concerning Terms, Levels of Analysis, and Processes.” Academy of Management Annals 9 (1): 845–928. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2015.1033148.

- Mik-Meyer, N. 2016. “Othering, Ableism and Disability: A Discursive Analysis of co-Workers’ Construction of Colleagues with Visible Impairments.” Human Relations 69 (6): 1341–1363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715618454.

- Mühlhoff, R., and J. Slaby. 2018. “Immersion at Work: Affect and Power in post-Fordist Work Cultures.” In Affect in Relation: Families, Places, Technologies, edited by B. Röttger-Rösler, J. Slaby, 154–174. London and New York: Routledge.

- Negri, A. 1999. “Value and Affect.” Boundary 2 26 (2): 77–88.

- Parke, M. R., and M. G. Seo. 2017. “The Role of Affect Climate in Organizational Effectiveness.” Academy of Management Review 42 (2): 334–360. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0424.

- Pérez Huber, L., and D. G. Solorzano. 2015. “Racial Microaggressions as a Tool for Critical Race Research.” Race Ethnicity and Education 18 (3): 297–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2014.994173.

- Pierce, C. M. 1974. “Psychiatric Problems of the Black Minority.” American Handbook of Psychiatry 2: 512–523.

- Price, M. 2015. “The Bodymind Problem and the Possibilities of Pain.” Hypatia 30 (1): 268–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/hypa.12127.

- Pulrang, A. 2022. 3 Disability Microaggressions And Why They Matter. Forbes Magazine, February 26. https://www.forbes.com/sites/pulrang/2022/02/26/5-disability-microaggressions-and-why-they-matter/

- Reeve, D. 2002. “Negotiating Psycho-Emotional Dimensions of Disability and Their Influence on Identity Constructions.” Disability & Society 17 (5): 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590220148487.

- Reeve, D. 2006. “Towards a Psychology of Disability: The Emotional Effects of Living in a Disabling Society.” In Disability and Psychology: Critical Introductions and Reflections, edited by D. Goodley and R. Lawthom, 94–107. London: Palgrave.

- Reeve, D. 2013. “Psycho-Emotional Disablism and Internalised Oppression.” In Disabling Barriers – Enabling Environments, edited by J. Swain, C. Thomas, C. Barnes, S. French, 92–98. London: Sage.

- Riach, K., and L. Cutcher. 2014. “Built to Last: Ageing, Class and the Masculine Body in a UK Hedge Fund.” Work, Employment and Society 28 (5): 771–787. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017013506773.

- Robert, P. M., and S. L. Harlan. 2006. “Mechanisms of Disability Discrimination in Large Bureaucratic Organizations: Ascriptive Inequalities in the Workplace.” The Sociological Quarterly 47 (4): 599–630. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2006.00060.x.

- Samoy, E., and L. Waterplas. 2012. “Designing Wage Subsidies for People with Disabilities, as Exemplified by the Case of Flanders (Belgium).” Alter 6 (2): 94–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alter.2012.02.014.

- Sanmiquel-Molinero, L., and J. Pujol-Tarrés. 2020. “Putting Emotions to Work: The Role of Affective Disablism and Ableism in the Constitution of the Dis/Abled Subject.” Disability & Society 35 (4): 542–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1650719.

- Scholz, F., and J. Ingold. 2021. “Activating the ‘Ideal Jobseeker’: Experiences of Individuals with Mental Health Conditions on the UK Work Programme.” Human Relations 74 (10): 1604–1627. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726720934848.

- Schur, L., D. Kruse, and P. Blanck. 2013. People with Disabilities: Sidelined or Mainstreamed? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Shakespeare, T. 1994. “Cultural Representation of Disabled People: Dustbins for Disavowal?” Disability & Society 9 (3): 283–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599466780341.

- Shakespeare, T. 2006. Disability Rights and Wrongs. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Shildrick, M. 2009. Dangerous Discourse of Disability, Subjectivity and Sexuality. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Singer, J. 1999. “Why Can’t You Be Normal for Once in Your Life? From a Problem with No Name to the Emergence of a New Category of Difference.” In Disability Discourse, edited by M. Corker, S. French, 59–70. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Sue, D., C. Capodilupo, G. Torino, J. Bucceri, A. Holder, K. Nadal, and M. Esquilin. 2007. “Racial Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Implications for Clinical Practice.” The American Psychologist 62 (4): 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271.

- Swain, J., and S. French. 2000. “Towards an Affirmation Model of Disability.” Disability & Society 15 (4): 569–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590050058189.

- Thomas, C. 2007. Sociologies of Disability and Illness: Contested Ideas in Disability Studies and Medical Sociology. London: Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Vachhani, S. J., and A. Pullen. 2019. “Ethics, Politics and Feminist Organizing: Writing Feminist Infrapolitics and Affective Solidarity into Everyday Sexism.” Human Relations 72 (1): 23–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718780988.

- van Amsterdam, N., D. van Eck, and K. Meldgaard Kjær. 2023. “On (Not) Fitting In: Fat Embodiment, Affect and Organizational Materials as Differentiating Agents.” Organization Studies 44 (4): 593–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/01708406221074162.

- Van Laer, K., E. Jammaers, and W. Hoeven. 2022. “Disabling Organizational Spaces: Exploring the Processes through Which Spatial Environments Disable Employees with Impairments.” Organization 29 (6): 1018–1035. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508419894698.

- Washington, E. F., A. H. Birch, and L. M. Roberts. 2020. “When and How to Respond to Microaggressions.” Harvard Business Review, July 3, 2020. https://hbr.org/2020/07/when-and-how-to-respond-to-microaggressions

- Watermeyer, B. 2012. Towards a Contextual Psychology of Disablism. London and New York: Routledge.

- Watermeyer, B., and L. Swartz. 2008. “Conceptualising the Psycho-Emotional Aspects of Disability and Impairment: The Distortion of Personal and Psychic Boundaries.” Disability & Society 23 (6): 599–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590802328477.

- Waters-Lynch, J., and C. Duff. 2021. “The Affective Commons of Coworking.” Human Relations 74 (3): 383–404. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726719894633.

- Wendell, S. 1996. The Rejected Body: Feminist Philosophical Reflections on Disability. New York and London: Routledge.

- Williams, J., and S. Mavin. 2012. “Disability as Constructed Difference: A Literature Review and Research Agenda for Management and Organization Studies.” International Journal of Management Reviews 14 (2): 159–179. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2012.00329.x.

- Zeyen, A., and O. Branzei. 2023. “Disabled at Work: Body-Centric Cycles of Meaning-Making.” Journal of Business Ethics: JBE 185 (4): 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05344-w.