ABSTRACT

Teacher and headteacher assessments and professional development are deemed critical levers for improving quality education in an increasing number of countries and contexts. However, prioritising improvement is not always evident, given that sometimes those subjected to assessments are not effectively informed about their performance (e.g. from national teacher examinations) or how to improve their work via feedback. This paper explores the bridging role of feedback concerning teacher and headteacher assessments and continuing professional development in the Mexican context, where scarce research exists. This mixed-methods research contributes evaluation evidence of Mexico’s 2013–2018 education reform, including high-stakes staff assessments and individual feedback reports. Survey data from 122 primary school teachers and headteachers and thirteen interviews with teachers, headteachers and policymakers indicate the feedback report made it difficult to distinguish between poor and proficient performance and identify strengths and weaknesses. Challenges regarding suitable continuing professional development following assessment feedback are put forward.

Introduction

Teacher and headteacher assessments and continuing professional development (CPD) are two critical areas of policy and research concerned with whether and how monitoring and training education workers contribute to quality education improvement, mainly in primary and lower secondary (Barber & Mourshed, Citation2007; Muijs et al., Citation2014; OECD, Citation2005; Reynolds et al., Citation2012). However, the benefits or otherwise of explicit linkage between these two approaches have been scarcely empirically explored in previous literature, especially in the Mexican context. The extent of separation between the purposes and operationalisation of staff assessment and CPD systems varies in different countries and contexts. For example, teacher and headteacher assessment may be conducted concerning accountability by employing school inspections or screening criteria for employment, such as standards and frameworks for teachers and school leaders (Catano & Stronge, Citation2007; Ehren et al., Citation2016; Martinez et al., Citation2016; Martínez Rizo, Citation2016; Ofsted, Citation2019). In addition, assessments can be concerned with enhancing teaching and leadership competencies for which different forms of CPD are commonly used (Cortez Ochoa, Citation2020; Day & Sachs, Citation2004; Fullan, Citation2009; Harris et al., Citation2006; Mitchell, Citation2013; Timperley et al., Citation2007; Timperley, Citation2011).

In this paper, teacher and headteacher assessments are understood and explored as a central process steered by the educational authority aiming at fulfilling accountability and development goals. Furthermore, it is essential to emphasise that while a related term, i.e. evaluation, refers to broader performance monitoring approaches, individual teacher assessments involve predetermined tasks that are practical and situated processes seeking to determine adherence to expected performance levels (Cortez Ochoa & Thomas, Citation2023; Goldring et al., Citation2009).

In some contexts, the information teacher and headteacher assessments provide about improving teaching and headteachers’ duties is often managed and interpreted by decision-makers and less commonly by those subjected to them, which does not necessarily translate into enhancing teaching and school management, administration or leadership more broadly (Lillejord & Børte, Citation2020). In the context of evaluation systems with consequences for the job, such as that implemented in Mexico, sharing this information with those subjected to assessments could be critical for improvement. In this paper, Mexico’s National Teacher Evaluation (including headteachers), which prevailed between 2013 and 2018, will be reviewed, drawing on original mixed-methods data from primary school teachers and headteachers evaluated in 2015 and 2016. Policymakers’ views are also brought to the fore to provide an integral account of the reform and its implications for the education system and, more specifically, for improving teaching and headteachers’ performance.

The Mexican case is unique because of two main reasons. First, at the policy level, its emergence is linked to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) consulting on suitable approaches to teacher assessment in Mexico (Cuevas-Cajiga & Moreno-Olivos, Citation2016; Moreno Salto et al., Citation2022). Second, at the practice level, unlike in previous similar assessments in the country, teachers and headteachers were provided with feedback on their performance, which was meant to inform on strengths, weaknesses and decisions on further professional development.

The efficacy of teacher and headteacher assessments and how this links to opportunities for professional development as suitable approaches to improve the quality of education have also been subjected to debate in the academic literature (Isoré, Citation2009; Lavigne, Citation2014; Martínez Rizo, Citation2016; Papay, Citation2012; Santiago et al., Citation2012). In part, this might occur because staffing evaluation systems are often criticised regarding their validity, reliability, and fairness (Kane & Douglas, Citation2012); also because the relationship between training and educational improvement is far from straightforward (Guskey, Citation2002, Citation2013; Timperley et al., Citation2007; Timperley, Citation2011). Therefore, this paper explores the bridging role of feedback between national teacher and headteacher assessments and opportunities for continuing professional development to understand whether this component is suitable for education improvement. By contrasting the views of teachers, headteachers and policymakers, the paper seeks to provide insight into how different actors perceived the usefulness of feedback for enhancement and potentially the different applicability of this evaluation component for teachers versus headteachers to improve educational quality in Mexico.

The remainder is organised as follows. First, a context is provided, including an overview of Mexico’s education system, characteristics of Mexico’s teacher workforce, previous teacher assessment schemes in Mexico, and a summary of the 2013 reform. After this, a literature review addresses current debates about teacher and headteacher assessments, feedback, and continuing professional development. The research methods, findings, discussion and policy recommendations are provided separately. The paper seeks to respond to the following research questions:

What are teachers’, headteachers’ and policymakers’ perceptions about feedback reports informing on professional strengths and areas for improvement in the context of the new Mexican teacher evaluation system?

How informative are feedback reports regarding appropriate support for future continuous professional development?

What are the tensions between what teachers and headteachers were asked to improve via a feedback report and their self-perceived professional development needs and CPD uptake?

Research context

An overview of the Mexican education system

In Mexico, access to education from preschool to higher education is a legal right. Public educational services are funded through taxes and managed by the central federal authority through the Secretariat of Public Education (SEP in Spanish) in coordination with the 32 States that integrate this democratic republic (DOF, Citation2019). Mexico’s education system is organised as follows: basic education (preschool (3–6 year-olds), primary (6–12 year-olds) and lower-secondary (12–15 year-olds)), upper-secondary (15–18-year-olds), and higher education. Basic education and upper secondary are mandatory, and in 2016–2017, more than 240 thousand schools and about 1.5 million teachers provided compulsory state-funded education to more than 30 million pupils (INEE, Citation2018).

Teachers and the teachers’ union

The federal authority mainly pays basic education teachers’ salaries; however, teachers employed by the States may receive different wages and perks compared with those who work for the federal government (Barrera & Myers, Citation2011). Most Mexican teachers working in state-funded schools are unionised under The National Union of Education Workers (SNTE in Spanish). The SNTE represents 1.5 million teachers, the approximate number of teachers working in basic education during 2016–2017 (INEE, Citation2018). The median teachers’ age at the primary level is 39, with female teachers making up 67% of the total (INEE, Citation2015a, p. 31). Approximately 74% of the teachers in primary education hold a permanent contract, and 64% are full-time teachers (Backhoff & Pérez-Morán, Citation2015).

Previous teacher evaluation schemes

Since the early 1990s, Mexico’s government has adopted educational reforms to improve the quality of education (Cordero et al., Citation2013; Escárcega & Villarreal, Citation2007; Santibañez et al., Citation2007). Teacher and headteacher assessments and access to different forms of CPD were deemed essential to these changes. However, researchers have documented that previous schemes and training were mainly used for salary improvement and promotion (Santibañez & Martínez, ; Schmelkes, Citation2017). Furthermore, these assessments were voluntary schemes to reward teachers and headteachers if they complied with administrative requirements, such as participating in training, sitting written examinations, and accumulating years of experience. Reviews of the impact of previous evaluation schemes in Mexico suggest modest improvement in education quality indicators (Barrera & Myers, Citation2011; Cerón et al., Citation2006; Santibañez et al., Citation2007). These more lenient versions of national evaluations took on a different tone during the federal administration period between 2012–2018, incorporating accountability components and making participation in future assessments mandatory for all teachers and headteachers (i.e. universal) in the state-funded sector (Echávarri & Peraza, Citation2017; Peraza & Betancourt, Citation2018; Torres, Citation2019).

Mexican education reform 2013–2018

In December 2012, the former president of Mexico, Enrique Peña Nieto from the PRI party, alongside the leading political parties in the Federal Congress, endorsed the Pacto por México [Pact for Mexico]. The political agreement included an education reform to guarantee the right to quality education. Researchers and policy actors further maintained that this change would help the Mexican government recover control of education affairs from the teachers’ union (Arnaut, Citation2014; Cuevas-Cajiga, Citation2018; Ornelas & Luna Hernández, Citation2016; Pérez Ruiz, Citation2014). A new universal and compulsory teacher and headteacher evaluation system [hereafter teacher evaluation] was central to the reform and changes to teacher CPD. The legislative initiative was passed and published in the Federal Official Gazette on 26th February 2013 (DOF, Citation2013).

The new teacher evaluation was set to improve the quality of state-funded education by determining suitable professional standards and rewarding merit (DOF, Citation2013; Ramírez & Torres, Citation2016). This new scheme regulated entry to the professional education service (hiring), including regulation of temporary contracts; career development pathways (promotion); and ongoing in-service teacher performance appraisal, at least every four years, with consequences for the job (retaining the post) of basic education and upper-secondary teachers and headteachers. Given the high-stakes components of the evaluation system, it can be argued that the intention was to equip the scheme with summative consequences, including rewards and sanctions. Still, unlike its predecessors, the new teacher evaluation system would provide participants with individual feedback to inform decisions on further professional development. This formative component was novel and foresaw teachers and headteachers as active agents of their professional improvement via targeted training.

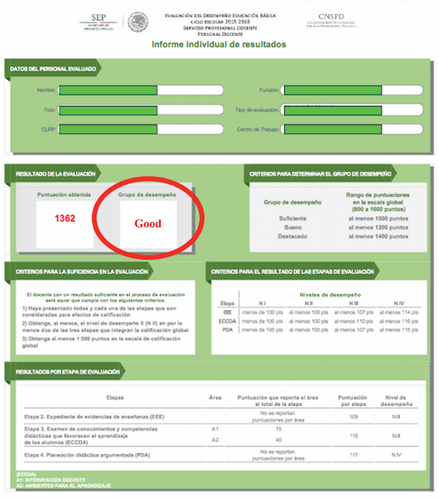

Results in the assessments were communicated via individual online feedback reports as follows; entrants to the service, headteachers and those participating in obtaining a promotion, e.g. a headteacher post, could receive one of two outcomes: non-proficient or proficient. In-service teachers who participated in retaining their position could receive one of four outcomes: insufficient, sufficient, good, or outstanding. In addition, an overall numeric score and rubric-like descriptors of performance, with no particular orientation regarding future CPD, were presented in the same report. Appendix 1 shows an example of an individual feedback report. Participation was mandatory by law, so those who did not sit the evaluation could be dismissed (DOF, Citation2013).

Before the education reform, no national normative references existed for ‘good’, ‘suitable’, or ‘acceptable teaching’ in Mexico (INEE, Citation2015b; OREALC/UNESCO, Citation2016). Instead, the teacher workforce was regulated by a code of conduct, positing rights and duties (Barrera & Myers, Citation2011; Cuevas-Cajiga, Citation2018; DOF, Citation1946). Thus, professional profiles were generated in the wake of education reform to standardise teachers’ and headteachers’ performance expectations.

Teaching standards in mexico’s teacher evaluation

In February 2014, Teacher and Headteacher profiles were issued (SEP, Citation2017). These profiles ‘are the references for the teacher assessments because they define the characteristics of a good teacher [and headteachers] in terms of knowledge, skills and professional responsibilities oriented towards quality teaching’ (INEE, Citationn.d.., p. 8). Previous research suggests the profiles were arguably based on Danielson’s Framework for Teaching and draw on a similar experience in the region, such as The Good teaching framework from Chile, all informed by consultancy from the OECD to the Mexican government (Barrera & Myers, Citation2011; Cortez Ochoa, Citation2015; Cuevas-Cajiga & Moreno-Olivos, Citation2016; Galaz Ruiz et al., Citation2019). presents the five dimensions of the Teacher and Headteacher profiles.

Table 1. Five dimensions of the professional profiles for primary teachers and headteachers.

Teacher evaluation instruments

Teacher entry assessments and promotion to headteacher, superintendent, and technical pedagogical advisors relied on exams about general content knowledge and professional and ethical responsibilities (Ruiz, Citation2018). The 2015 and 2016 evaluations randomly selected 10% of in-service teachers and headteachers and assessed them through various phases (see ). While the SEP stated that phase 1 was to be used as a diagnostic (Vargas, Citation2016), the National Institute for Educational Evaluation (INEE) argued that it was incorporated into the feedback report handed to evaluated teachers (INEE, Citationn.d..). However, the inclusion of phase 1 in the individual feedback is not evident, an issue that is addressed later in this paper.

Table 2. Phases of the new staff evaluation system.

Classroom observations, either in-person or videotaped, were not part of the evaluation (Cordero et al., Citation2013; Schmelkes, Citation2015) due to their high cost (OREALC/UNESCO, Citation2016). Therefore, this new system was constrained to indirectly evaluate teachers’ and headteachers’ knowledge of the profession, actual classroom practice, and other observable skills, such as school management. Unlike previous programmes, neither the teachers’ years of experience nor certificates from participation in CPD were considered for marks (Cordero & González, Citation2016). Certified evaluators marked the teachers’ responses to the assignments and the exam using rubrics and guidelines from the INEE (SEP, Citation2016, Citation2019). Computer interfaces and the Internet were used for all evaluation phases, and participants were required to sit some parts of the evaluation in secure centres across the country.

Literature review

This section provides an overview of the literature on teacher evaluation systems, the role of feedback following assessments, and opportunities to engage with continuing professional development. Research gaps are identified and reflected on in relation to Mexico’s education reform.

Teacher evaluations systems, common uses and contentious aspects

Education authorities worldwide increasingly adopt teacher evaluation systems for hiring, managing performance, as well as to providing incentives schemes to teachers, removing ineffective personnel and making decisions on CPD (Isoré, Citation2009; Martínez Rizo, Citation2016; OECD, Citation2013; Santiago et al., Citation2012; Stewart, Citation2013). Monitoring teachers and headteachers is deemed one resource governments use to gradually improve the workforce’s quality and the education service (Donaldson & Papay, Citation2014; Hallinger et al., Citation2014). Nevertheless, such a relationship is neither linear nor unproblematic (Lavigne, Citation2014; Tuytens & Devos, Citation2014; Tuytens et al., Citation2020). Research shows that depending on the consequences of the evaluation system, those subjected to assessments can either resist the reform, approve it, or comply without genuine commitment (Jiang et al., Citation2015; Martínez Rizo, Citation2016; Ávalos & Assael, Citation2006). Similarly, resistance is more likely to happen when a values dissonance occurs between what is proposed by the evaluations and the teacher’s self-sense of a mission (Jiang et al., Citation2015; Tuytens & Devos, Citation2009).

Tuytens et al. (Citation2020) conducted a literature review on teacher evaluation systems worldwide between 2000 and 2016 and identified three broader outcomes from teacher assessments: changes in ability, motivation, and behaviour. The way these evaluations typically operate is by attaching accountability components (summative) and developmental aspects (formative) (Delvaux et al., Citation2013; Isoré, Citation2009; Papay, Citation2012; Scheerens et al., Citation2003). While summative assessments might lead to rewards or sanctions, providing feedback to teachers, headteachers, and decision-makers are typical forms of the formative components of a teacher evaluation and often are meant to inform professional development opportunities (Cortez Ochoa et al., Citation2018; Hargreaves & Shirley, Citation2009; Lillejord et al., Citation2018; Sahlberg, Citation2011).

Some scholars recommend a combination of formative and summative consequences to address different purposes of assessments (Darling-Hammond, Citation2001; Guerra & Serrato, Citation2015; Strong, Citation2016) — as in the Mexican evaluation. However, others have claimed that integrating both targets at the same time is ineffective (Callahan & Sadeghi, Citation2015; Marzano, Citation2012; Popham, Citation1988); mainly because ‘[…] its formative function contaminates its summative function, and vice versa’ (Popham, Citation1988, p. 271). Thus, leading to policies that ‘neither remove nor improve teachers’ (Popham, Citation1988, p. 271). Others have raised concerns that when high-stakes consequences are attached to teacher and headteacher assessments, making up evidence of good performance might occur, not leading to improvement and still satisfying monitoring and evaluation criteria; this has been named performativity (Ball, Citation2003; Webb, Citation2006).

These debates in the field are ongoing and lead to reflection on a suitable approach to improve teaching while a degree of accountability is also achieved. These issues also spark questions about whether teacher and headteacher assessment results provide adequate information to the appropriate actors of the education systems. In that sense, one critical knowledge gap relates to whether assessment participants receive the feedback they need to enhance their practice and what use they give to it. These points are further explored in the next section.

Feedback in the context of teacher and headteacher assessments

Feedback for teaching and leadership improvement in the context of high-stakes evaluation systems, mainly those contributing information on the summative and formative strands, is a less explored research area than, for instance, research about formative assessments and feedback provision from school leaders to teachers following low-stakes appraisals (Mireles-Rios & Becchio, Citation2018; Rigby et al., Citation2017; Roberge, Citation2014). Some district- and state-wide teacher evaluation programmes in the USA have included feedback. For instance, in Cincinnati, Taylor and Tyler (Citation2012) explored a scheme that included year-round classroom observations and personalised performance information based on the evaluations. Such an evaluation system had consequences for the teachers’ jobs, such as denying contract renewal for novice teachers who underperformed in the four-year programme and limiting promotions for tenured teachers. Their study supports the introduction of teacher assessments to improve effectiveness during the year of the evaluation and beyond. In particular, they stress the role of written feedback school supervisors provide to teachers and its potential to prompt reflections and professional conversations with colleagues, leading to improvement.

Another example is the Measures of Effective Teaching study from which the Gathering Feedback for Teaching report was released (Kane & Douglas, Citation2012). The authors wanted to understand whether combining different sources of information could predict teacher effectiveness better than single measures. They concluded that teacher effectiveness could be predicted more reliably when combining classroom observations, student surveys, and value-added measures. Still, the outcomes of such research seemed to have served academics and decision-makers rather than informed individual teachers. As often occurs with large-scale performance assessments, the information from external performance assessments rarely reaches teachers or headteachers in a way that enables them to make informed decisions on what and how to improve (Lillejord & Børte, Citation2020). Researchers argue that feedback provision must be contextualised for successful improvement, making sense to those who receive it and allowing reflection on three main regards: ‘Where am I going? (What are the goals?), How am I going? (What progress is being made towards the goal?), and Where to next? (What activities need to be undertaken to make better progress?)’ (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007, p. 86). Thus it becomes more apparent that following assessments and timely supply of feedback to different agents in an education system, the next step is continuing professional development provision, which is addressed next.

Continuing professional development

Mounting research supports continuing professional development as a fundamental lever for teaching and quality education improvement (Boudah et al., Citation2017; Cordingley et al., Citation2018; Elizondo & Gallardo, Citation2017; Thomas et al., Citation2018). Opportunities to engage in training have been classified as formal and informal, i.e. those purposively designed and delivered by training organisations, and others less structured and happening in everyday settings, respectively (Darling-Hammond & Wei, Citation2009; Eraut, Citation2004; Mitchell, Citation2013; Ávalos, Citation2011). Teachers and headteachers typically engage in both types of professional development; however, this paper explores the take-up of formal CPD provided by the education authority through their established national training catalogues. It is recognised that the provision of formal CPD can pursue additional teaching and leadership enhancement purposes. For instance, participation in training can be used to decide on promotions and reward those who participate more in further training (Day & Sachs, Citation2004; Harris et al., Citation2006; Sørensen, Citation2017). This was the approach followed in Mexico before the education reform of 2013, where the number of hours and certificates of participation counted towards marks for promotion.

In-service training has a privileged status as a suitable method to address underperformance and initial preparation deficits (Collinson et al., Citation2009; Ingvarson et al., Citation2005; Kennedy, Citation2016). However, the relationship between participation in CPD and improvement is not straightforward. In part, this is because teachers’ and headteachers’ motivations to join further training alongside previous experiences with professional development and the effects it has had on teaching and learning are all critical in whether CPD is a successful venture or not (Guskey, Citation2002, Citation2016; Timperley et al., Citation2007; Timperley, Citation2011). CPD, rather than an abstract almighty tool for improvement, is an ever-changing adaptative method with varying effects and results in different contexts and times (Firestone, Citation2014; Fullan, Citation1998; Timperley et al., Citation2007). In that sense, gaining insight into stakeholders’ experiences with the new Mexican evaluation system is critical. Specifically, whether feedback reports successfully inform strengths and areas of improvement and effectively advise on professional development needs while bridging summative and formative purposes of assessments.

Materials and methods

This paper draws on primary data collected via sequential mixed-methods design (Creswell, Citation2014; Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2004; Morgan, Citation2007). The article focuses on the success or otherwise, purpose and usefulness of feedback reports handed to those who sat the national assessments to uncover stakeholders’ views of the formative aspect of the evaluation, mainly its function as a bridge between the assessments and opportunities for further training. This section explains the data collection instruments comprising a questionnaire and interview schedule, the sampling approach, and data analysis. Data collection was conducted between August 2017 and January 2018.

Data collection methods: an overview of the instruments

The Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) teacher questionnaire (OECD, Citation2014) was used as a reference point and adapted for an online teacher/headteacher survey. The instrument contained (i) a presentation and consent form and (ii) 37 questions distributed into four parts. Demographic data, such as gender, age, and academic degree, were collected in the first part of the questionnaire. The remaining three sections addressed CPD opportunities before and after the reform and the perceived strengths and weaknesses of the new feedback report. The questionnaire was piloted and, once finalised, administered in Spanish to primary teachers and headteachers in Mexico via online communities of teachers and email. The average questionnaire completion time was 20 minutes. provides a summary of questionnaire items relevant to this research article.

Table 3. Questionnaire items related to the feedback report and additional professional development.

Semi-structured interviews were also used for additional data collection. The interview protocols were designed drawing on previous relevant local and international research (Harris et al., Citation2006; INEE, Citation2016) and refined through piloting. Interviews aimed to gain in-depth data on the participants’ experiences with teacher evaluations, feedback, and CPD before and after the education reform of 2013. The face-to-face interviews were conducted in Spanish and lasted 45 minutes on average. The interviews were conducted across three regions: Southwest, Southeast, and Central Mexico. The following are examples of semi-structured interview questions relevant to this paper’s findings:

In your view, what is the purpose of the feedback report following the assessment?

How does the feedback report provide insight (or not) about areas of strength and improvement?

How did the different sections (e.g. evaluation instruments) inform professional development needs?

What is the relationship between the feedback and the CPD options approached after this evaluation?

Sampling approach and research participants

The empirical quantitative data of this research was gathered via convenience sampling (De Vaus, Citation2002; Etikan, Citation2016) from primary teachers (n = 69) and headteachers (n = 53) who had been evaluated in 2015 or 2016 (total n = 122). According to Etikan (Citation2016), convenience sampling relates to nonprobability samples drawn from a population that share specific characteristics suitable for research, such as willingness to participate, and their geographic accessibility, among others. Access to the questionnaire sample participants was achieved via publicly available lists of teacher contact details (INEGI, Citation2014) and social media, an approach supported by previous research (Brickman, Citation2012; Kapp et al., Citation2013; Ramo & Prochaska, Citation2012).

Qualitative data was collected via semi-structured interviews with a subsample of those responding to the questionnaire. Maximum variation sampling was used to select eight teachers, two headteachers, and three elite policymakers, i.e. closely involved in the inception of reform. This type of purposive sampling seeks to gather an ample range of research participants (Etikan, Citation2016). For this research, it was considered necessary to collect the views of teachers and headteachers from a range of results in the national assessments. summarises the data collection instruments, sampling method and the number of participants in this research. The research received approval from the School of Education University of Bristol’s ethics committee, and participants were provided with appropriate background information to inform consent. Consent was obtained from the participants in written form before collecting data.

Table 4. Data collection instruments and sample: a summary.

Data analysis

The questionnaire results were analysed using SPSS software and are reported separately for teachers and headteachers, mainly using descriptive statistics, i.e. percentages and frequencies. Verbatim transcripts of the interviews were analysed using NVivo software and a six-step approach to thematic analysis (Braun et al., Citation2015). Two researchers inductively coded across the datasets, followed by a deductive review. Four themes were generated from the interview data in relation to the research questions and are listed in the findings section. The questionnaire and interview findings are contrasted between teachers, headteachers, and policymakers to address the specific research questions.

Limitations

The sampling strategy might have omitted the perspectives of participants who, for different circumstances, rarely use online channels for communication and participation in research. In this regard, it is critical to reassert the potential non-generalisability of the findings to the broader population of teachers in Mexico and thus, inferential tests were not used to make claims regarding causality or statistical significance. Nevertheless, the sample size allowed us to confidently conduct descriptive statistical analyses to identify relevant patterns in the data. The study was conducted in Spanish, so speakers of local languages might not have participated, limiting the representativeness of such groups. Finally, collecting perceptions regarding teaching performance can be subject to social desirability (Deakin & Wakefield, Citation2014; Gosgling et al., Citation2004; Sue & Ritter, Citation2007). Although the degree to which this might have happened was not assessed, it is expected that the anonymity and confidentiality guaranteed to participants lessened such a situation in the present study.

Findings

This section presents the findings using the paper’s research questions as subheadings. The results are informed by jointly quantitative and qualitative data, using descriptive statistics from the questionnaires and four themes generated from the semi-structured interviews, typescript in italics for easy recognition. The qualitative interview themes are the following:

Standardisation of feedback reports

Feedback for CPD decision-making and development

Challenges and tensions regarding CPD uptake following feedback

CPD requirements leniency for outstanding and proficient staff

RQ1

What are teachers’, headteachers’ and policymakers’ perceptions about feedback reports informing on professional strengths and areas for improvement in the context of the new Mexican teacher evaluation system?

Following the assessments, teachers and headteachers received an electronic feedback report stating their overall performance in the evaluation (category & numeric score) alongside qualitative descriptors of their competence in the various assessment phases. The questionnaire participants were asked about the extent of informativeness of the different sections in their feedback reports, mainly concerning strengths and weaknesses in their respective roles. As shown in , over half of teachers and headteachers found all elements of the feedback report informative in detecting areas for improvement. However, comparing teachers’ and headteachers’ responses, larger proportions of teachers expressed moderate or much informativeness in the non-exam elements of the feedback, mainly regarding the lesson plan and student portfolio section. Overall, teachers found feedback relating to the exam less informative than the non-exam elements, while the opposite result was found for headteachers. The reason for this is unclear, but it possibly suggests a difference in the quality and relevance of different elements of the assessments for teachers and headteachers, which may need to be reviewed in future research. It is also plausible that because exams typically assess factual knowledge, this assessment phase appeared more relevant to headteachers’ administrative duties and less to teachers who are more familiar with lesson planning and collecting students’ learning evidence.

Table 5. Evaluation sections and perceived informativeness about areas for improvement.

Although most teachers and headteachers found the different sections of the feedback informative, a large minority, 36–48% of teachers and 40–49% of headteachers, were less optimistic regarding the different feedback elements. Qualitative interview data permits further inquiry regarding the informativeness of the feedback report to identify potential areas of improvement. The first theme relates to a perceived standardisation of feedback reports, as illustrated in quotes from a teacher, headteacher and policymaker below:

I compared my results with the first place of the group of outstanding teachers who received a monetary incentive, and I couldn’t see a big difference between our scores (Emma – teacher, sufficient).

Some colleagues have 25 years of experience, and they have been assessed and given feedback under an evaluation that is not taking into account many things, like teaching experience (Oscar – headteacher, proficient MTE).

The feedback reports are not very different from person to person and not very accurate regarding the teachers’ performance. We have received some claims and witnessed the same recommendation for a teacher with a good result given to another with insufficient or sufficient category (David, policymaker).

The quotes above might indicate that while feedback reports were meant to inform about improvement areas, providing a standard format to each evaluation participant reduced the reports’ capacity to offer tailored recommendations on what to improve and, most importantly, how to improve it. Interestingly, while teachers and policymakers found the feedback to be standard across evaluation performance categories, headteachers were more concerned with standardisation irrespective of professional experience, suggesting that different actors expected different insights following the evaluation, something that standardised reports were unable to provide. Further, Emma’s and David’s quotes also suggest that teachers might have prioritised one of the components of the report: the category in which the evaluated teacher or headteacher was located, e.g. sufficient, good, proficient. This situation might have deviated attention from the formative value of feedback, including targeted information about teaching and leadership strengths and weaknesses.

Questionnaire data also suggest mixed findings regarding the feedback reports as helpful in identifying teachers’ and headteachers’ strengths and weaknesses, as shown in . Teachers are less convinced than headteachers about the detailed insight the feedback could provide on their strong and weak areas, although the percentage differences between them are small, and in both cases, below 50% of the total surveyed participants.

Table 6. Perceptions on the identification of strengths, weaknesses and further CPD.

RQ2

How informative are feedback reports regarding appropriate support for future continuous professional development?

Survey data also revealed that less than half, 40.6% and 43.4% of teachers and headteachers, respectively, agreed or strongly agreed that the feedback reports facilitated decision-making about suitable CPD to tackle the identified teaching and leadership weaknesses. These proportions suggest somewhat inconclusive evidence on whether the feedback has been helpful. Nevertheless, qualitative findings provide some further light. A second identified theme named: feedback for CPD decision-making and development suggests that some perceived the feedback report as beneficial to informing about weaknesses that could eventually contribute to the development and uptake of CPD. Example participant quotes are shown below:

According to my feedback, I got low grades on the content knowledge exam; therefore, I sought CPD about teaching strategies in language and maths. Also, I failed many questions regarding SEN; hence, I need to diversify my plan to serve this kind of student

I am taking CPD based on my assessment results because I want to get up to date, and I feel good about it. Also, if CPD allows me to do my work better and impact the students’ learning, I would be happy

The evaluation is useful for the teachers, so they know what CPD to undertake

We share this information with the teachers’ union so that teachers can work with their schools and representatives from the union, and the Secretariat of Education

When the teacher is insufficient, we develop a course for them. The workshop is tailored to the phases of the evaluation and is offered in many states across the country

Across the range of interview participants, it is evident that the feedback report was perceived as a component that teachers and headteachers can use for deciding on their future CPD. Leon and Martin see further professional development positively impacting their students’ learning. Also, policymakers perceived a direct relationship between the feedback report and continuing professional development. Still, their approach to training teachers varies substantially. For instance, Helen seemed to trust the teachers’ judgement on what CPD to take following the assessments and notification of their results in the feedback. David saw the report as informing primarily the teachers’ union, which, before the education reform of 2013, played a minimal role in teacher training. He also perceived this as a hierarchical relationship between teachers and education authorities. Furthermore, Alex framed teacher professional development as designed and offered to teachers top-down, i.e. steered by the education authority.

In sum, the perspectives on the role of the novel feedback report included in the new teacher evaluation system are divided. Some teachers and headteachers found the feedback helpful in identifying areas for improvement, but less than half do so regarding CPD. In addition, policymakers see the report as instrumental for CPD development. Given the standardisation of the feedback report, teachers and headteachers found it difficult to distinguish between poor and appropriate performance. In contrast, policymakers were particularly pleased about the availability of this resource, as it was seen as helpful in addressing professional development needs at a national- or state-wide scale.

RQ3

What are the tensions between what teachers and headteachers were asked to improve via a feedback report and their self-perceived professional development needs and CPD uptake?

Several tensions were found regarding teachers’, headteachers’, and policymakers’ views of the feedback regarding CPD needs and uptake. Questionnaire participants expressed their most needed areas of CPD following the evaluation (). Notably, the highest proportions concentrate mainly on training topics related to addressing student personal development needs (e.g. Special Education Needs), psychological development, school administration and management, and teaching in multicultural settings. These areas are typically less available in centrally managed, formal professional development opportunities (SEP, Citation2012). Contrarily, traditional CPD areas and those most likely targeted in staff assessments, such as content knowledge, pedagogy and student assessment, are at the bottom of the self-perceived professional development needs after the national evaluation. This tension is worth gaining the attention of CPD decision-makers which illustrates that teachers and headteachers have ideas about what they need to enhance professionally. Their interest in the characteristics of the most recent curriculum was expected because changes to it were undergoing at the time of data collection. Given their professional duties, it was also expected that headteachers were more interested than teachers in CPD relating to School administration and management.

Table 7. Areas of professional development most needed after the assessments.

In addition to the above, qualitative data presents a third theme called challenges and tensions regarding CPD uptake following feedback which illustrates how different actors perceive the role of further professional development following the national evaluation. Example teacher, headteacher and policymaker quotes include:

Once I received my feedback report, I sought additional training to pass the evaluation because that is all that matters

My report indicated that I needed training related to management and the superintendent’s responsibilities. However, I couldn’t find anything related to that. Instead, I am undertaking one course about annual plan design

I see no congruence. It is said that schools are communities of learning, but the only one undergoing CPD is the headteacher [or the teacher] who was assessed. Then, that is not a community

When teachers take the training, we are no longer talking about it as a simple certificate; we are talking about their professionalisation to enhance the practice

Interestingly, while teacher Simon, who was destined to sit the national assessments again due to his result, i.e. insufficient, perceived additional CPD as a way to comply with the norm and potentially succeed the next time he was assessed, teacher Julia tried to follow the feedback report and take training on her areas of improvement. However, in her case, such professional development was unavailable when she wanted to take it, leading her to take something else. The latter illustrates a downside of teacher evaluation systems that fail to address all parts of the process, particularly readiness and sufficient capacity to offer professional development opportunities in line with detected performance weaknesses.

Martin raised another critical aspect related to equal access to CPD for school staff. Because the Mexican evaluation targeted only 10% of in-service teachers and headteachers in 2015 and 2016 (this paper’s focus), it is likely that at the school level, staff members would have experienced the processes of being assessed and participating in professional development at different paces. This situation might have limited headteachers’ capacity to lead their personnel as a learning community, as expressed by this interviewee. For Alex, CPD participation under this new evaluation system represented a shift in purpose beyond credentialism as in previous evaluation schemes in Mexico. Still, it is worth noting that such a view contrasts with teachers who see professional development as a compliance component of their contractual relationship with the education authority, like Simon.

The case of teachers and headteachers who got the highest marks in the evaluation, i.e. outstanding and proficient, respectively, is worthy of the last analytical theme of this paper related to the perceived CPD requirements leniency for outstanding and proficient staff, as illustrated by the following quotes:

This report described what areas I got the lowest grades. However, because mine was an outstanding result, there were a few areas for improvement

No, we have not been told what CPD to take, really. In my school, I have asked those who have been evaluated, me included, to share with the rest of the teachers the procedures of the evaluation so that they get first-hand information about it

A more senior teacher with a good result in the assessments might not need the same CPD as one who is in their early years and gets similar results via feedback

In this theme, interview participants with the highest possible results in the assessments, as illustrated by teacher Tanya and headteacher Oscar, seemed to have been unable to identify what to improve and how to do it via CPD. However, this did not prevent participants in these categories from being proactive and locating additional training that would suit their perceived needs, as shown in previous quotes from research participants. Further, Helen considers that in-service experience was not taken into account when recommending CPD via the feedback report. In the broader interview, she referred to a need for more closely monitored training of less experienced teachers and more freedom for those with more years in the education sector.

Discussion

This paper explored teachers’, headteachers’, and policymakers’ perspectives on the usefulness of feedback reports following teacher and headteacher performance assessments. Insofar scarce research in Mexico has addressed the bridging role of feedback in the light of large-scale high-stakes assessments and opportunities for improving teaching and headteachers’ performance via further professional development. The role of feedback in informing about strengths and weaknesses, leading to additional, pertinent training, was contrasted with research participants’ views on self-perceived professional development needs and CPD uptake.

This research did not find conclusive evidence on the perceived informativeness of the feedback reports to advise teachers or headteachers on areas for improvement. The standardisation of feedback might have played a critical role in the negative perceptions of some research participants. This is in line with previous international literature challenging the effectiveness of evaluation systems with a limited capacity to distinguish individuals who perform in line with standards and those who do not (Callahan & Sadeghi, Citation2015; Marzano, Citation2012). If feedback reports are unclear regarding what teachers and headteachers of varying performances should improve, this drawback needs attention.

Nevertheless, findings indicate that while teachers find feedback regarding their performance in the ‘lesson plan and student portfolio’ more helpful about areas for improvement than headteachers with regard to the comparable ‘school management project’, the latter were proportionally more in agreement with feedback regarding the exam component. These findings align with Mireles-Rios and Becchio (Citation2018) research, who found that when teachers receive feedback related to their classroom duties and includes information on their areas for improvement alongside aspects regarding their strengths, they respond positively to assessments, enhancing their confidence and sense of accomplishment, similar to the change in behaviour identified in other studies (Tuytens et al., Citation2020). On the contrary, this research’s results deviate from knowledge regarding headteachers’ perspectives on the matter (see, Alkaabi & Almaamari, Citation2020; Ridder, Citation2018), as the Mexican headteacher participants seemed to be more confident in getting confirmation about factual knowledge of management and administrative duties, as assessed via the exam. These findings might relate to the history of evaluation systems in this country and the use of exams to get rewards and get promoted (Schmelkes, Citation2017).

As shown, feedback reports included summative and formative components, and this situation might have led teachers and headteachers to care more for the aspects related to their permanence in the job or those associated with incentives and sanctions. Research in the field continues a heated debate between those who favour combining evaluation purposes and those against it (Marzano, Citation2012; Popham, Citation1988; Strong, Citation2016). Interview findings suggest that teachers, headteachers and policymakers tended to refer to the overall result in the assessments more markedly than the developmental aspects of feedback. Therefore, presenting both summative and formative purposes in the same report may not have been appropriate. Still, the evaluation served an instrumental purpose for education authorities and other actors, including officials of the teachers’ union and the Secretariat of Education regarding CPD provision. This view contrasted with perspectives indicating that the feedback report was imprecise in guiding decisions regarding professional development. Predominantly, the feedback report was seen as a one-size-fits-all device that could serve the needs of individual teachers and CPD providers from the teachers’ union and the Secretariat of Education.

Given the limitations made visible by this research, the Mexican experience should be examined in further depth by think tanks and international organisations that promote suitable approaches to teacher assessment, especially the OECD, given that the evaluation reform was based on their policy advice (Cortez Ochoa, Citation2015; Cuevas-Cajiga & Moreno-Olivos, Citation2016; Moreno Salto et al., Citation2022).

Several tensions related to feedback and CPD were identified. Teachers and headteachers with the highest marks in the evaluations were notably less provided with tailored guidance on improving their areas for improvement or for maintaining good performance in the future. As noted in the literature (Lillejord & Børte, Citation2020; Timperley, Citation2011), it is fundamental to let teachers know what to improve and the necessary steps to enhance their professional performance. In this research, it was challenging to distinguish between the participants’ motivations for further CPD from the feedback report or their self-initiated interest in other professional development. This situation casts doubt on the effectiveness of the feedback to inform further professional development grounded on evidence of performance.

Arguably, the assessments leaned towards aspects relating to teacher content and pedagogical knowledge and student learning assessment, but also about headteachers’ knowledge of school management and administration, as hinted by the new teacher and headteacher profiles and assessment methods. Thus, it might be anticipated that the participants would most likely gravitate to professional development opportunities related to those areas after the assessments. However, this research revealed that those topics were least preferred – except for school administration and management —, and others related to inclusion and student well-being were favoured. These findings illuminate recurrent tensions between what decision-makers imagine as suitable to address underperformance and the participants’ views on what they need to cope with day-to-day teaching, learning, and school leadership challenges (Collinson et al., Citation2009; Guskey, Citation2016; Ingvarson et al., Citation2005; Kennedy, Citation2016). School leaders were particularly under the pressure of a new national evaluation system that included several components demanding their optimal performance in managing personnel and the school more broadly, which might explain their higher interest in management and administration CPD.

The tensions extend to various viewpoints about engaging in professional development following their assessment. This article identified that across research participants, there is a perceived relationship between CPD and enhancing students’ learning. In this regard, previous research has noted that teachers are in a continuous decision-making process where prior experiences impact present and future behaviours in the profession (Mitchell, Citation2013; Timperley et al., Citation2007; Yoon et al., Citation2007). Nevertheless, CPD was also seen as a bureaucratic aspect that must be fulfilled, and a means to maintain the teaching position. This is a clear example of performativity (Ball, Citation2003; Webb, Citation2006), where those subjected to assessment adhere to professional criteria and perform as expected by the employer to maintain the status quo. This attitude is pernicious to enhancing teaching and education quality and should be addressed. This could be tackled in the Mexican teacher assessments if underperformers and teachers with ‘pass’ marks in the evaluations were equally motivated to participate in opportunities for CPD in line with their competences and professional needs. Otherwise, further training becomes a punishing component rather than developmental.

This research found evidence that some teachers and headteachers opted for tackling self-identified professional development needs. Previous research has noted that performance assessments and personalised feedback can motivate self-prescribed professional development to address perceived areas of underperformance (Firestone, Citation2014; Fullan, Citation1998; Timperley et al., Citation2007). Yet, while some participants seemed to have discerned what CPD to take – based on their feedback report – the unavailability of suitable further training was a limitation. This is an issue decision-makers could address when designing evaluation systems focusing on teaching and school leadership improvement via additional professional development. Finally, headteachers found it problematic to have a minority of personnel under evaluation and CPD (given only 10% selected to participate) as it limited their capacity to lead and manage their schools as a community (see Nguyen et al., Citation2022), although this is an area that deserves further research.

Recommendations for policy and practice

Based on the evidence, four recommendations for policy and practice arose. First, given the standardisation of feedback reports and their associated pitfalls, it is sensible to incorporate the views of headteachers and superintendents in the appraisal and improvement of teachers and headteachers – with prior relevant training on this matter. As mentioned in the context section, their viewpoints were not included in the feedback teachers received following the assessments (see Appendix 1). This information could be valuable for contextualising and informing CPD decisions in line with development needs. Second, it was evidenced that a combined format where teachers know about their summative and formative results might not be appropriate if a critical aim of the policy is to promote teacher and headteacher development. Recent research in Norway (Lillejord & Børte, Citation2020) restated the pernicious effects on improvement when both evaluation purposes are combined. As informed in the broader literature (Callahan & Sadeghi, Citation2015; Marzano, Citation2012; Popham, Citation1988), the summative effects tend to eclipse the developmental side of assessments, potentially leading to little or no improvement.

Third, in contrast to Taylor and Tyler (Citation2012), evaluating teachers per se does not necessarily improve teaching, but improvements are more likely associated with the evaluation feedback domain and further professional development. In that sense, it is imperative to revindicate the role of CPD in helping teachers enhance their practice. In the Mexican context, CPD has been variously employed as part of rewards and sanctions, possibly distorting professional development intention. Thus, it may be appropriate to untag CPD to either gain something in economic terms or avoid something, for instance, being dismissed or sanctioned for not taking it. Finally, this research permits recommending the generation of CPD opportunities for teachers and headteachers that accommodate training grounded on external appraisal and self-identified needs. Doing so could contribute to the revindication of professional development previously argued.

Disclosure statement

The authors reported no potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Artemio Arturo Cortez Ochoa

Artemio Arturo Cortez Ochoa is a Lecturer in Education and pathway lead of the MSc in Educational Leadership and Policy at the School of Education, University of Bristol, UK. He was a Research Associate at the REAL Centre, University of Cambridge, UK, in the Leaders in Teaching initiative – Rwanda. His research interests include quality education, teacher evaluation systems and continuous professional development in low- and middle-income contexts. He also authored the Review of evaluation approaches to school principals, International Encyclopedia of Education 4th Edition. Elsevier Ltd.

Sally M. Thomas

Sally M. Thomas is a Professor of Education at the School of Education, University of Bristol (UoB), and has conducted and led academic research studies for 30+ years. Previously, she was Director of the UoB’s Centre for Assessment and Evaluation Research (CAERe) 2012-17, an Associate Director and founding member of the International School Effectiveness and Improvement Centre at the London Institute of Education 1993-2000, and has also worked at the University of Oxford and the London School of Economics. Her main publications are on different aspects of educational quality, which have examined a variety of factors, indicators and processes related to school, teacher and institutional effectiveness and improvement, both in the UK and internationally (China, Latin America and Africa).

Israel Moreno Salto

Israel Moreno-Salto is Assistant Professor of Educational Sciences at the Universidad Autónoma de Baja California in northern Mexico. He holds a PhD in Education from the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge. His research interests intersect different aspects of education policy and practice, comparative education, large-scale assessments and governance, and teacher education.

References

- Alkaabi, A. M., & Almaamari, S. A. (2020). Supervisory feedback in the principal evaluation process. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 9(3), 503–509. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijere.v9i3.20504

- Arnaut, A. (2014). Lo bueno, lo malo y lo feo del Servicio Profesional DocenteReforma Educativa, Qué estamos transformando? Debate informado (G. Del Castillo & G. Valenti, Eds.). FLACSO, México.

- Ávalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in Teaching and Teacher Education over ten years. Teaching & Teacher Education, 27(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007

- Ávalos, B., & Assael, J. (2006). Moving from resistance to agreement: The case of the Chilean teacher performance evaluation. International Journal of Educational Research, 45(4–5), 254–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2007.02.004

- Backhoff, E., & Pérez-Morán, J. C. (2015). Segundo Estudio Internacional sobre la Enseñanza y el Aprendizaje (TALIS 2013) Resultados de México. Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación. https://www.oecd.org/education/school/Mexico-TALIS-2013_es.pdf

- Ball, S. J. (2003). The teacher’s soul and the terrors of performativity. Journal of Education Policy, 18(2), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093022000043065

- Barber, M., & Mourshed, M. (2007). How the world’s best-performing school systems come out on top. McKinsey & Company. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-008-9075-9

- Barrera, I., & Myers, R. (2011). N° 59 Estándares y evaluación docente en México: el estado del debate. PREAL. (Issue October

- Boudah, D. J., Blair, E., Mitchell, V. J., Boudah, D. J., Blair, E., Implementing, V. J. M., & Mitchell, V. J. (2017). Implementing and sustaining strategies instruction: Authentic and effective professional. Development or “Business as Usual”? 2835(February. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327035EX1101

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Terry, G. (2015). Thematic Analysis. In P. Rohleder & C. L. Anotnia (Eds.), Qualitative research in clinical and health psychology (pp. 95–113). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brickman, C. B. (2012). Not by the Book: Facebook as a Sampling Frame. Sociological Methods & Research, 41(1), 57–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124112440795

- Callahan, K., & Sadeghi, L. (2015). Teacher perceptions of the value of teacher evaluations: New Jersey’s archive NJ. International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation, 10(1), 46–59.

- Catano, N., & Stronge, J. H. (2007). What do we expect of school principals? Congruence between principal evaluation and performance standards. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 10(4), 379–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603120701381782

- CEMABE-INEGI. (2014). Censo de Escuelas, Maestros y Alumnos de Educación Básica y Especial 2013: Atlas educativo. http://cemabe.inegi.org.mx

- Cerón, M. S., Corte Cruz, F. M., & Del, S. (2006). Competitividad y exclusión. Una década de carrera magisterial en Tlaxcala. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, XXXVI(número 3–4), 293–315.

- Collinson, V., Kozina, E., Lin, Y. -H., Ling, L., Matheson, I., Newcombe, L., & Zogla, I. (2009). Professional development for teachers: A world of change. European Journal of Teacher Education, 32(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619760802553022

- Cordero, G., & González, C. (2016). Análisis del Modelo de Evaluación del Desempeño Docente en el Marco de la Reforma Educativa Mexicana. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 24(46), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.24.2242

- Cordero, G., Luna, E. S., & Patiño, N. X. (2013). La evaluación docente en educación básica en México: Panorama y agenda pendiente. Sinéctica: Revista Electrónica de Educación, 41(2), 2–19.

- Cordingley, P., Greany, T., Crisp, B., Seleznyov, S., Bradbury, M., & Perry, T. (2018). Developing Great Subject Teaching Rapid Evidence Review of subject-specific CPD in the UK. Wellcome Trust. https://wellcome.org/sites/default/files/developing-great-subject-teaching.pdf

- Cortez Ochoa, A. A. (2015). Teachers’ evaluation in Mexico and its potential impact on quality education: lessons from the US and Chile: a library-based study of frameworks for teaching, instruments and outcomes. (Issue September). Unpublished Masters dissertation. University of Bristol.

- Cortez Ochoa, A. A. (2020). Amidst reforms: Mexican Teacher Evaluation and Professional Development from the perspective of teachers, headteachers, and policymakers [ PhD Thesis, University of Bristol]. https://ethos.bl.uk/OrderDetails.do?did=1&uin=uk.bl.ethos.818033

- Cortez Ochoa, A. A., & Thomas, S. M. (2023). Review of evaluation approaches for school principals. In R. J. Tierney, F. Rizvi, & K. Erkican (Eds.), International encyclopedia of Education (Fourth Edition) (pp. 453–468). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818630-5.05074-0

- Cortez Ochoa, A. A., Thomas, S., Tikly, L., & Doyle, H. (2018). Scan of International Approaches to Teacher Assessment. University of Bristol. http://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/education/documents/ScanofInternationalApproachestoTeacherAssessment.pdf

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Cuevas-Cajiga, Y. (2018). La Reforma Educativa 2013 vista por sus actores. First). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. http://ru.ffyl.unam.mx/handle/10391/6682

- Cuevas-Cajiga, Y., & Moreno-Olivos, T. (2016). Políticas de Evaluación Docente de la OCDE: Un Acercamiento a la Experiencia en la Educación Básica Mexicana. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 24, 120. Education Policy Analysis. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264047839-zh.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2001). Teacher testing and the improvement of practice. Teaching Education, 12(1), 11–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210123029

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Wei, R. C. (2009). Professional learning in the learning profession: a status report on teacher development in the United States and Abroad a Status report on teacher development in the United States and Abroad. National Staff Development Council, February, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1006/jfbi.2002.2063

- Day, C., & Sachs, J. (2004). Professionalism, Performativity and Empowerment: Discourses in the Politics, Policies and Purposes of Continuing Professional Development. In Day , C., & Sachs, J. (Eds.), International handbook on the continuing professional development of teachers. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Deakin, H., & Wakefield, K. (2014). Skype interviewing: Reflections of two PhD researchers. Qualitative Research, 14(5), 603–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794113488126

- Delvaux, E., Vanhoof, J., Tuytens, M., Vekeman, E., Devos, G., & Van Petegem, P. (2013). How may teacher evaluation have an impact on professional development? A multilevel analysis. Teaching & Teacher Education, 36, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.06.011

- De Vaus, D. (2002). Surveys in Social Research. Fifth). Allen & Unwin. https://doi.org/10.2307/2071069

- DOF. (1946). Reglamento de las condiciones generales de trabajo del personal de la Secretaría de Educación Pública. https://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_to_imagen_fs.php?codnota=4568071&fecha=29/01/1946&cod_diario=195555

- DOF. (2013). DECRETO por el que se expide la Ley General del Servicio Profesional Docente. https://www.diputados.gob.mx/sedia/biblio/prog_leg/082_DOF_11sep13.pdf

- DOF. (2019). Ley reglamentaria del artículo 3º. de la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, en materia de mejora continua de la educación. https://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/pdf/LRArt3_MMCE_300919.pdf

- Donaldson, M. L., & Papay, J. P. (2014). Teacher evaluation for accountability and development. In M. E. G. Helen & F. Ladd (Eds.), Handbook of research in education finance and policy (2nd ed., pp. 174–196). Routledge.

- Echávarri, J., & Peraza, C. (2017). Modernizing schools in Mexico: The rise of teacher assessment and school-based management policies. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 25, 90. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.25.2771

- Ehren, M., Jones, K., & Perryman, J. (2016). Side Effects of School Inspection; Motivations and Contexts for Strategic Responses. In Ehren , M. (Ed.), Methods and modalities of effective school inspections. Springer, Cham.

- Elizondo, J., & Gallardo, K. E. (2017). Desarrollo profesional docente en escuelas de educación primaria: un estudio diagnóstico desde una perspectiva internacional. Revista Panamericana de Pedagogía, 0(24), 135–170.

- Eraut, M. (2004). Informal learning in the workplace. Studies in Continuing Education, 262. https://doi.org/10.1080/158037042000225245

- Escárcega, R. M., & Villarreal, S. V. (2007). Un acercamiento al impacto de carrera magisterial en la educación primaria. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, XXXVII(números 1–2), 91–114.

- Etikan, I. (2016). Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Firestone, W. A. (2014). Teacher evaluation policy and conflicting theories of motivation. Educational Researcher, 43(2), 100–107. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X14521864

- Fullan, M. (1998). Educational Reform as Continuous Improvement. Keys Resource Book. https://michaelfullan.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/13396039520.pdf

- Fullan, M. (2009). Large-scale reform comes of age. Journal of Educational Change, 10(2–3), 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-009-9108-z

- Galaz Ruiz, A., Jiménez-Vásquez, M. S., & Díaz-Barriga, Á. (2019). Evaluación del desempeño docente en Chile y México. Perfiles educativos, 41(163), 156–176. https://doi.org/10.22201/iisue.24486167e.2019.163.58935

- Goldring, E., Cravens, X. C., Murphy, J., Porter, A. C., Elliott, S. N., & Carson, B. (2009). The evaluation of principals: What and how do states and urban districts assess leadership?. The Elementary school journal, 110(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1086/598841

- Gosgling, S. D., Vazire, S., Srivastava, S., & John, O. P. (2004). Should We Trust Web-Based Studies?: A Comparative of Six Preconceptions About Internet Questionnaires. The American psychologist, 59(2), 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.93

- Guerra, M., & Serrato, S. (2015). Michael Scriven: Evaluación formativa. Revista Para Docentes y Directivos. sep-dec, 2, 1–103. http://www.sev.gob.mx/upece/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/1.3-Michel-Scriven-Evaluaci%C3%B3n-formativa.pdf

- Guskey, T. (2002). Professional Development and Teacher Change. Teachers & Teaching, 8(3/4), 381–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/135406002100000512

- Guskey, T. (2013). Does It Make a Difference? Evaluating Professional Development. Redesigning Professional Development. http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/mar02/vol59/num06/Does-It-Make-a-Difference¢-Evaluating-Professional-Development.aspx

- Guskey, T. (2016). Gauge Impact with 5 Levels of Data. Gurskey Website. https://tguskey.com/wp-content/uploads/Professional-Learning-1-Gauge-Impact-with-Five-Levels-of-Data.pdf

- Hallinger, P., Heck, R. H., & Murphy, J. (2014). Teacher evaluation and school improvement: An analysis of the evidence. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 26(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-013-9179-5

- Hargreaves, A., & Shirley, D. (2009). The fourth way: The inspiring future for educational change. In The Fourth Way. The Inspiring Future for Educational Change. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452219523

- Harris, A., Day, C., Goodall, J., Lindsay, G., & Muijs, D. (2006). Evaluating the impact of CPD. Scotish Educational Review, 4(1), 23–29.

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

- INEE. (2015a). Los Docentes En México: Informe 2015. Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación. https://www.inee.edu.mx/publicaciones/los-docentes-en-mexico-informe-2015/

- INEE. (2015b). Política Nacional de Evaluación de la Educación Documento Rector Noviembre 2015. Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación. https://www.inee.edu.mx/images/stories/2014/Normateca/2014/Documento-Rector-PNEE1.pdf

- INEE. (2016). Evaluación del desempeño desde la experiencia de los docentes Consulta con docentes que participaron en la primera evaluación del desempeño 2015. Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación. https://www.inee.edu.mx/portalweb/suplemento12/evaluacion-del-desempeno-docente.pdf

- INEE. (2018). Panorama educativo de Mexico: Indicadores del Sistema Educativo Nacional 2017 Educación básica y media superior. Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación. https://www.inee.edu.mx/publicaciones/panorama-educativo-de-mexico-2018-educacion-basica-y-media-superior/

- INEE. (n.d.). Consideraciones sobre la validez y la justicia en las evaluaciones del desempeño docente. Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación. https://www.inee.edu.mx/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Validez_y_Justicia_.pdf

- Ingvarson, L., Meiers, M., & Beavis, A. (2005). Factors affecting the impact of professional development programs on teachers’ knowledge, practice, student outcomes & efficacy. Education policy analysis archives, 13, 13(10. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v13n10.2005

- Isoré, M. (2009). Teacher Evaluation: Current Practices in OECD Countries and a Literature Review. In Education Working Papers ( No. 23; Issue September). https://doi.org/10.1787/223283631428OECD

- Jiang, J. Y., Sporte, S. E., & Luppescu, S. (2015). Teacher Perspectives on Evaluation Reform : Chicago ’ s REACH Students. Educational Research, 44(2), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X15575517

- Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed Methods Research: A Research Paradigm Whose Time Has Come. Educational Researcher, 33(14), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033007014

- Kane, T., & Douglas, O. (2012). Gathering Feedback for Teaching: Combining High-Quality Observations with Student Surveys and Achievement Gains. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED540960.pdf

- Kapp, J. M., Peters, C., & Oliver, D. P. (2013). Research Recruitment Using Facebook Advertising: Big Potential, Big Challenges. Journal of Cancer Education, 28(1), 134–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-012-0443-z

- Kennedy, M. M. (2016). How Does Professional Development Improve Teaching?. Review of educational research, 86(4), 945–980. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315626800

- Lavigne, A. L. (2014). Exploring the Intended and Unintended Consequences of High-Stakes Teacher Evaluation on Schools, Teachers, and Students. Teachers College record, 116(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811411600103

- Lillejord, S., & Børte, K. (2020). Trapped between accountability and professional learning? School leaders and teacher evaluation. Professional Development in Education, 46(2), 274–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2019.1585384

- Lillejord, S., Elstad, E., & Kavli, H. (2018). Teacher evaluation as a wicked policy problem. Assessment in education: Principles, policy & practice, 25(3), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2018.1429388

- Martínez Rizo, F. (2016). La evaluación de docentes de educación básica. Una revisión de la experiencia internacional [Teacher Evaluation in Basic Education. A Review of the International Experience]. INEE.

- Martinez, F., Taut, S., & Schaaf, K. (2016). Classroom observation for evaluating and improving teaching: An international perspective. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 49, 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.03.002

- Marzano, R. J. (2012). The Two Purposes of Teacher Evaluation. Educational Leadership, 70(3), 14–19.

- Mireles-Rios, R., & Becchio, J. A. (2018). The Evaluation Process, Administrator Feedback, and Teacher Self-Efficacy. Journal of School Leadership, 28(4), 462–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268461802800402

- Mitchell, R. (2013). What is professional development, how does it occur in individuals, and how may it be used by educational leaders and managers for the purpose of school improvement?. Professional Development in Education, 39(3), 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2012.762721

- Moreno Salto, I., Robertson, S., & Cortez Ochoa, A. A. (2022). The OECD, the Vehicularity of Ideas, Wormholes and Teacher Education in Mexico. In Menter, I. (Ed.), The Palgrave Handbook of Teacher Education Research. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Morgan, D. (2007). Methodological Implications of Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Methods. Journal of mixed methods research, 1(1), 48–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/2345678906292462

- Muijs, D., Kyriakides, L., van der Werf, G., Creemers, B., Timperley, H., & Earl, L. (2014). State of the art - teacher effectiveness and professional learning. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25(2), 231–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2014.885451

- Nguyen, D., Boeren, E., Maitra, S., & Cabus, S. (2022). A Review on the Empirical Research of PLCs in the Global South: Evidence and Recommendations. https://www.vvob.org/en/downloads/review-empirical-research-plcs-global-south-evidence-and-recommendations

- OECD. (2005) . Teachers Matter: Attracting, Developing and Retaining Effective Teachers. OECD publishing.

- OECD. (2013). Teachers for the 21st Century: Using Evaluation to Improve Teaching. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/site/eduistp13/TS2013%20Background%20Report.pdf

- OECD. (2014). TALIS 2013 Results An International Perspective on Teaching and Learning. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264196261-en

- Ofsted. (2019). How valid and reliable is the use of lesson observation in supporting judgements on the quality of education? | 190029 | Ofsted. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/936246/Inspecting_education_quality_Lesson_observation_report.pdf

- OREALC/UNESCO. (2016). Evaluación de desempeño de docentes, directivos y supervisores en educación básica y media superior de México: Análisis y evaluación de su implementación 2015-2016 Informe final parte I. Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación.

- Ornelas, C., & Luna Hernández, V. (2016). La reforma educativa en México: Los primeros libros ensayo bibliográfico. Education Review//Reseñas Educativas, 23(July). https://doi.org/10.14507/er.v23.2110

- Papay, J. P. (2012). Refocusing the Debate: Assessing the Purposes and Tools of Teacher Evaluation. Harvard educational review, 82(1), 123–141. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.82.1.v40p0833345w6384

- Peraza, S. C., & Betancourt, L. R. (2018). La Política Educativa En El Proyecto De Nación: Balance Y Perspectivas. Entretextos, 9(28), 75–94.

- Pérez Ruiz, A. (2014). La profesionalización docente en el marco de la reforma educativa en México: EBSCOhost. Revista de La Realidad Mexicana, 28(184), 113–120. 8p.

- Popham, J. (1988). The dysfunctional marriage of formative and summative teacher evaluation. Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education, 1(3), 269–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00123822