Abstract

Construct: Pimping is a controversial pedagogical technique in medicine, and there is a tension between pimping being considered as “value adding” in some circumstances versus always unacceptable. Consequently, faculty differ in their attitudes toward pimping, and such differences may be measurable and used to inform future research regarding the impact of pimping on learner outcomes. Background: Despite renewed attention in medical education on creating a supportive learning environment, there is a dearth of prior research on pimping. We sought to characterize faculty who are more aggressive in their questioning style (i.e., those with a “pimper” phenotype) from those who are less threatening. Approach: This study was conducted between December 2015 and September 2016 at Johns Hopkins University. We created a 13-item questionnaire assessing faculty perceptions on pimping as a pedagogical technique. We surveyed all medicine faculty (n = 150) who had attended on inpatient teaching services at two university-affiliated hospitals over the prior 2 years. Then, using responses to the faculty survey, we developed a numeric “pimping score” designed to characterize faculty into “pimper” (those with scores in the upper quartile of the range) and “nonpimper” phenotypes. Results: The response rate was 84%. Although almost half of the faculty reported that being pimped helped them in their own learning (45%), fewer reported that pimping was effective in their own teaching practice (20%). The pimping score was normally distributed across a range of 13–42, with a mean of 24 and a 75th percentile cutoff of 28 or greater. Younger faculty, male participants, specialists, and those reporting lower quality of life had higher pimping score values, all p < .05. Faculty who openly endorsed favorable views about the educational value of pimping had sevenfold higher odds of being characterized as “pimpers” using our numeric pimping score (p ≤ .001). Conclusions: The establishment of a quantitative pimping score may have relevance for training programs concerned about the learning environment in clinical settings and may inform future research on the impact of pimping on learning outcomes.

Keywords:

Introduction

Pimping is a well-known term in the medical lexicon, described by Brancati as occurring when an “attending poses a series of very difficult questions to an intern or student [emphasis added].”Citation1(p89) It is also a controversial pedagogical technique in bedside medical education.Citation2,Citation3 On one hand, pimping can teach, motivate, and involve the learner in clinical rounds;Citation4–7 on the other hand, it may be interpreted as learner mistreatment.Citation8,Citation9 With reference to the latter, Kost and Chen suggested that the definition of pimping should be restricted to “questioning with the intent to shame or humiliate the learner to maintain the power hierarchy in medical education [emphasis added].”Citation3(p21) Heightened concerns for medical student and trainee mistreatment have recently placed renewed scrutiny on the practice of pimping.Citation10,Citation11 Nonetheless, there remains a spectrum of opinion toward pimping in clinical practice and in the literature, with some promoting the potential virtues of this practice and others who feel it is a shameful relic of the past that should be banished from modern medical education. This spectrum is enabled by the lack of a universally agreed-upon definition for what pimping actually is; for example, the term can mean different things to different people ranging from Socratic banter to a more malignant belittlement. Thus, there is a tension between pimping being considered as “value adding” in some circumstances versus pimping as being always unacceptable.

Contributing to the controversy and uncertainty regarding the value of this technique is the paucity of research addressing the role of pimping in medical education.Citation2 Multiple gaps in our understanding exist as to the prevalence of pimping in modern academic medical centers, faculty perceptions about pimping, demographic and attitudinal correlates with pimping, and the impact of pimping on student satisfaction and learning outcomes. The objective of the current study was to examine faculty perceptions about pimping and to develop an instrument designed to characterize clinical teaching faculty as “pimpers” or “nonpimpers.” Such an instrument could in theory facilitate faculty development efforts, quality improvement directed toward the local learning culture, and further research on the impact of pimping on learner outcomes. Second, we set out to correlate pimping behaviors with other professional factors, such as faculty demographics and their well-being. While attempting to be unbiased as to the pros and cons of this pedagogical technique, we hypothesized that faculty reporting diminished professional well-being (e.g., burn out or poor quality of life) would be more likely to be characterized as pimpers. This hypothesis was grounded in prior literature suggesting that pimping may occur or be perceived more frequently in negative learning environments.Citation5

Method

Study design, subjects, and setting

For this cross-sectional study, we surveyed Department of Medicine faculty at one of two locations: Johns Hopkins Hospital (a large, tertiary-referral academic medical center) and Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center (a smaller academic hospital). Both locations provide comprehensive clinical education to medical students and graduate medical education trainees (interns, residents, and fellows). Each has a geographically distinct internal medicine residency program. The survey was sent electronically to all faculty who had attended for 2 or more weeks during the past 2 years on any of the following three teaching services at either hospital: general medicine wards, medical intensive care units, or cardiac intensive care units.

Survey development

The survey instrument was designed with three objectives in mind: (a) to probe faculty perspectives on pimping as a pedagogical strategy, (b) to characterize faculty respondents as pimpers or nonpimpers based on their self-reported bedside teaching questioning style (using a pimping scale), and (c) to test relationships of these characterizations with other variables of interest.

The survey instrument was developed using an iterative process over several months. First, the research questions, hypotheses, and candidate survey questions were presented to a group of Johns Hopkins medical education experts at a research-in-progress academic conference in December 2015. The choice of candidate survey questions was informed by examination of the literature. The literature review and feedback obtained from content experts provided content validity evidence to the pimping scale. This process resulted in a pilot survey of 40 questions. Of these, 25 were core questions addressing the pimping construct, and 15 were supplementary demographic questions and questions designed to establish relation to other variables validity evidence.

Next, we conducted two rounds of survey piloting, analyzing responses, and soliciting feedback from 18 purposively preselected faculty members. These faculty were selected to pilot the survey by the authorship team on the basis of their reputations and predilections toward or against pimping behaviors. Questions were modified and iteratively revised based on feedback obtained during these two rounds of testing, whereas others were eliminated because of either skewed responses by all or an apparent inability to discriminate between respondents. Ultimately, 11 core questions tied to pimping questioning style remained in the final pimping scale. To minimize any social desirability bias, these 11 core questions did not include any reference to the term pimping. Two further attitudinal questions were included at the end of the survey that directly asked faculty about their perspectives on pimping (here we defined the term loosely as “repeatedly asking challenging questions to reveal medical knowledge deficiencies that may result in embarrassment,” so as to strike a balance between the benign and malignant interpretations of the practice). As such, the survey included 13 questions addressing the pimping construct. Response options for the survey questions used Likert scales. Those questions tied to frequency of behaviors had six response options (never, rarely, sometimes, often, most of the time, and always) and those tied to level of agreement had four response options (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree; see Appendix , which provides details on the full survey).

Table 1. Baseline faculty demographics according to self-reported attitude toward pimping

Data collection

The survey was disseminated in July 2016, and responses were collected and recorded through September 2016. The survey was hosted on the Qualtrics platform (http://www.qualtrics.com; Qualtrics, Provo, Utah) using a secure institutional account that allowed anonymous completion by faculty respondents. To encourage participation, there were weekly drawings of Amazon gift certificates for respondents. We targeted a response rate of greater than 80%. The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol (date April 20, 2016; protocol number IRB00098488).

Data analysis

Demographics and other baseline variables were compared among the faculty respondents using analysis of variance, Kruskal-Wallis, or chi-square testing, as appropriate. Using similar statistical approaches, we also compared survey question responses of general internal medicine faculty versus specialty medicine faculty.

To characterize faculty respondents as pimpers or nonpimpers, we calculated a summative pimping score for each faculty respondent by adding up their numeric responses to the first 11 core questions in the pimping scale. Specifically, for the frequency questions, a response of never was assigned a value of 1 through always, which had a value of 6. Similarly, for the level of agreement questions, the four responses were assigned values of 1 through 4 (Appendix ). Higher values of this summative score suggest more of a predilection toward pimping behaviors; the theoretical range of possible values was 11 to 50. Exploratory analysis prior to dissemination of the final survey revealed that preselected faculty in our pilot with known predilections toward pimping had higher mean values on this summative score than those known to have more supportive and less intimidating educational approaches (two-sided t test, p = .03).

Among faculty who completed the final survey, we tested the distribution and normality of this pimping score using Kernel Density plots and the Shapiro-Wilk test. Associations between faculty exposure variables (e.g., demographics, teaching setting, and self-reported metrics of well-being) and the pimping score value were determined using unadjusted and adjusted multivariable linear and logistic regressions (depending on whether the pimping score was analyzed as a continuous or a categorical outcome variable). In the categorical analyses, we defined the binary (yes/no) outcome of pimper phenotype based on whether a faculty member was in the fourth quartile of the pimping score distribution (i.e., a pimping score ≥28) and then used logistic regression to identify predictors of being designated a pimper.

Relation to other variables validity evidence was assessed by correlating the binary pimper phenotype with responses to the two direct attitudinal pimping questions included at the end of the survey. To address response process validity evidence, faculty participating in the pilot testing commented on their interpretation of what the questions were asking and rated clarity and lack of ambiguity for each. Further, for analytic purposes, we included data only from faculty who answered all survey questions. In addition, we reviewed the distribution of responses for each survey item to ensure that faculty were not selecting the same option for each item to complete the survey quickly. All analyses were performed using STATA-13 (Stata, College Station, TX) and two-sided p values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 150 faculty who received the survey, one faculty member disclosed that they were ineligible because they had not served as an inpatient teaching attending within the last 2 years. Of the 149 eligible faculty, 125 responses were obtained (84% response rate). The mean age of the faculty sample was 49 years; 61% were male, and 70% were White. The median number of weeks per year that faculty reported serving as inpatient teaching attending was 6, with an interquartile range from 3 to 12 weeks. Approximately 40% of respondents reported they were general internal medicine physicians, and 49% self-identified as clinician educators. With respect to well-being in the sample overall, 4% of faculty reported poor quality of life, up to 18% reported being dissatisfied with work–life balance, 34% reported feeling burned out more than once a month, and 22% reported feeling more callous toward people over their time practicing medicine (see Appendix , which tabulates descriptive data for aggregate responses to the survey questions).

Comparison of faculty based on positive or negative attitude toward pimping

compares demographic and well-being data among faculty who agreed with the statement “Being pimped by my teachers helped me learn when I was a medical trainee” (n = 56) versus those who disagreed (n = 69). The faculty with positive attitudes toward having been pimped were more likely to work in the larger tertiary-referral academic medical center (p < .001) and were more likely to be specialists (p = .03). Faculty who appreciated being pimped also appeared more likely to endorse a poor quality of life (7% vs. 1%) and feelings of callousness (29% vs. 16%), although these differences did not reach statistical significance.

Responses to survey questions addressing the core construct of pimping

summarizes the responses to each of the core survey questions pertaining to pimping, comparing the general medicine to the specialty faculty. Specialty faculty were more likely to provide affirmative responses in 11 of the 13 questions, with four of these reaching statistical significance. In addition, specialists were also statistically more likely than generalists to assert that pimping of learners is an effective teaching method during rounds (p = .01).

Table 2. Responses to questioning style survey questions according to general versus specialist medical practice

Distribution of the summative pimping score

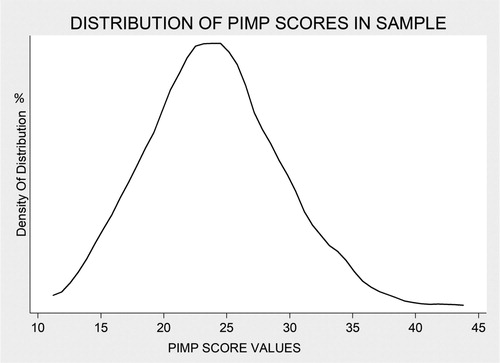

The range of values for the summative pimping score derived from faculty responses to the first 11 pimping survey questions was 13 to 42 (potential range of 11–50), with a mean and median of 24 and a normal distribution (; Shapiro-Wilk p value = .4). The quartile cutoffs for this score were as follows: first quartile ≤20 (n = 32), second quartile 21–23 (n = 30), third quartile 24–27 (n = 33), and fourth quartile ≥28 (n = 30). The mean summative pimping score value was significantly higher among specialists (25) than that seen in the generalist faculty members (22, p = .05; ).

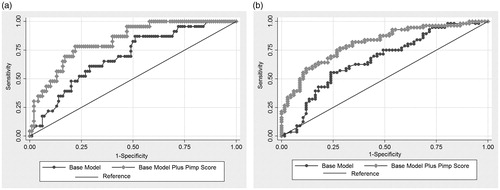

Figure A1. (a) The ability to predict faculty who agree or strongly agree with the first attitudinal question about pimping was significantly improved by adding the pimping score to a base model that included age, gender, medical practice (GIM versus specialty), and teaching location (c-statistic for base model of 0.69 vs. c-statistic of 0.83 for base model plus pimp score p=0.006) (eFigure 1a). (b) The ability to predict faculty who agree or strongly agree with the second attitudinal question about pimping was also significantly improved by adding the pimp score to the same base model (c-statistic for base model of 0.66 vs. c-statistic of 0.81 for base model plus pimp score p<0.001) (eFigure 1b).

Pimping score values and independent predictors of the ‘pimper’ phenotype

Faculty who were younger, were male, were working in the larger tertiary-referral academic medical center, and practice as specialists were statistically more likely to have higher mean values of the pimping score (see Appendix , which demonstrates results from unadjusted linear regression models and models adjusted for faculty age, gender, and race). Similar to the findings for differences in mean pimping score value, crude and adjusted logistic models demonstrated that pimpers (i.e., faculty with pimping scores in fourth quartile) were more likely to be younger (approximately 5% lower odds of being a pimper per year increase in age) and working at the larger tertiary-referral academic medical center (). Specialists were also 3 to 4 times more likely to be pimpers than nonspecialists (e.g., odds ratio [OR] = 3.7, p = .01), and there was a significantly lower odds of being a pimper among faculty reporting higher quality of life. As expected, faculty members who answered often, most of the time, or always (N = 12) to Question 3 of our survey were 9 times more likely to be identified as pimpers using our score, after adjustment for age, gender, and race (p = .003).

Table 3. Unadjusted and adjusted associations of faculty demographics with odds of being characterized a “pimper”

Table A1. Aggregate responses to the full survey

Table A2. Unadjusted and adjusted associations of faculty demographics with mean differences in self-reported pimping score value

Correlation between pimper phenotype and reported pimping attitude (construct validity)

Faculty designated as pimpers based on their pimping score value were more likely to agree that “Pimping of students or residents is an effective teaching strategy on clinical rounds” (OR = 4.9, p = .002), 95% CI [1.8, 13.4], adjusted for age, gender, and race. Similarly, pimper faculty were more convinced that “Being pimped by my teachers helped me learn when I was a medical trainee” (OR = 6.6, p < .001), 95% CI [2.4, 17.7], adjusted for age, gender, and race. Our pimping score also accurately discriminated faculty who agreed with these latter two direct questions, with results provided in the appendix.

Discussion

This study characterizes the questioning practices of attending physicians who lead teams of learners in inpatient settings at two academic teaching hospitals. Almost half of the faculty surveyed reported some positive attitudes about the value of pimping. The survey responses were used to derive a novel quantitative pimping score that is supported by validity evidence and allows for discrimination of faculty who are pimpers from those who are not. This score may enable further medical education research, including the ability to link faculty pimping behavior to higher level educational outcomes. Further work from our group is under way in this regard. In the current study, we were able to describe demographic features and other correlates that were associated with the pimping phenotype in our sample.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first published works to describe clinical teaching faculty’s views about pimping.Citation12 Accordingly, these results inform our understanding of faculty perceptions about pimping of medical trainees. For example, although almost half the faculty appeared to recall being the subject of pimping in positive terms, they were much less likely to report that they themselves thought pimping was effective in their own teaching practice. This phenomenon has been seen in a similar survey of pharmacists.Citation12 One may hypothesize that many faculty have purposively chosen not to be the source of pimping themselves, perhaps because of their preference to be viewed as a source of support rather than an instigator of stress. Nonetheless, faculty with stronger self-reported predilections toward pimping behavior in their teaching practice (based on the numeric responses to our pimping scale) were more likely to recall and believe that being pimped had helped them to learn when they were training. As such, it appears that, for pimping, prior learning experiences may inform future teaching behaviors.

The association between younger faculty, male faculty, and specialists with higher pimping score values is of interest and may reflect, at least in part, a desire by faculty with these characteristics to be respected and feared by their juniors.Citation7,Citation13 Such a position is hard to prove definitively, and there may also be other more benign reasons behind this finding. Furthermore, the association between faculty reporting lower quality of life with predictions toward pimping behavior is in keeping with the more negative perspectives on this pedagogical practice.Citation3,Citation14 In the quarter century since Brancati’s publication on the topic,Citation1 the pimping of trainees has been increasingly called into question by virtue of its presumed link with student mistreatment.Citation3,Citation8,Citation11 However, whether pimping truly represents learner mistreatment is unclear, and there remains a case in favor of the practice depending on how one defines it. We believe that pimping is an interactional phenomenon and that its virtues or drawbacks may ultimately come down to one’s perceived definition of “pimping,” how it is internalized by the learner,Citation15 the learning environment, and the intention of the attending physician.Citation2

The few small studies published on pimping to date have reported inconsistent findings and evaluated lower level educational outcomes only, such as students’ reactions to pimping.Citation14–17 Our pimping score may be useful in future medical education research on this topic or for educational program leaders wanting to learn the style and approaches of those selected to teach learners (and how these approaches may or may not be grounded in best practices for learning). First, the survey is short and can be easily disseminated via e-mail. Second, the 11 core questions included in the scale do not make reference to the term pimping and as such minimize any bias in responses. If the two attitudinal questions making direct reference to pimping are included in future scholarly efforts using our pimping scale, we recommend that these questions be included at the end of the survey so that they do not influence responses to the 11 core questions. Third, the pimping score derived from these data appeared to help identify cohorts of faculty (e.g., younger, males, specialists) in whom pimping may be more likely to occur and could identify target groups where interventions to reduce pimping behaviors may be more necessary. In addition, it is known that learners themselves have varied opinions about pimpingCitation2,Citation14,Citation15; thus, our score could be used to match students with faculty who exhibit either pimping or nonpimping phenotypes, based on students’ preferences regarding the practice. Finally, we are conducting follow-up studies testing whether our pimping score can be used to assess the relationship between faculty pimping behaviors and higher level educational outcomes (such as knowledge acquisition) and clinical outcomes (like accurate diagnoses versus medical errors and more thoughtful testing with efficient high value care).Citation18 Future studies are also necessary to determine the significance of differences in our score on meaningful educational outcomes.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, self-report of teaching style is subject to social desirability and other biases. The pimping score is a surrogate for teaching behavior, and it is not based on direct observations. Therefore, we cannot always be sure that faculty identified as pimpers using our score are pimpers in reality. However, because the score is based largely on frequency of performing specific acts, this may be more accurate than attitudinal assessments.Citation19 Second, faculty who responded to the survey may have been more interested or favorably predisposed toward pimping as compared with nonrespondents. However, our 84% response rate among all eligible faculty is reassuring that the results should be internally generalizable. With regards to external generalizability, one cannot assume that the perspectives in this cohort would match those of faculty affiliated with other departments or schools, so additional validation studies in other cohorts is necessary. Third, there are limitations to this type of survey research when dealing with a topic like pimping, which often incites emotional responses and which tends to polarize opinion. Finally, we understand that program-level attitudes, cultures, and behaviorsCitation20 may have an even greater impact on the learning environment or trainee well-being than do individual, faculty-level behaviors.

In conclusion, pimping behaviors continue at teaching hospitals in contemporary medical education. This study describes a pimping scale as a tool that allows for the identification and phenotyping of clinical teachers who use this questioning style in their educational approach. Although there may be many applications of the tool and possibilities for future research, it may be most useful for faculty to be aware of and reflect upon how they relate to learners.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board on April 20, 2016 (reference number 00098488).

Previous presentations

Oral abstract presentation in Baltimore, Maryland on July 2017 at the JHU Masters of Education in the Health Professions (MEHP) Summer Conference: Advancing Careers through Interprofessional Health Professions Education-Teach, Research, Lead.

Acknowledgments

This paper represents the thesis work Dr. McEvoy undertook as part of his MEHP degree course. Dr. Wright is the Anne Gaines and G. Thomas Miller Professor of Medicine and is supported through the Johns Hopkins Center for Innovative Medicine.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brancati FL. The art of pimping. JAMA. 1989;262(1):89–90.

- McCarthy CP, McEvoy JW. Pimping in medical education: lacking evidence and under threat. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2347–2348.

- Kost A, Chen FM. Socrates was not a pimp: changing the paradigm of questioning in medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90(1):20–24.

- Antonoff MB, D'Cunha J. Retrieval practice as a means of primary learning: Socrates had the right idea. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;23(2):89–90.

- McConnell MM, Eva KW. The role of emotion in the learning and transfer of clinical skills and knowledge. Acad Med. 2012;87(10):1316–1322.

- Hautz WE, Schroder T, Dannenberg KA, et al. Shame in medical education: a randomized study of the acquisition of intimate examination skills and its effect on subsequent performance. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29(2):196–206.

- Healy JM, Yoo PS. In defense of “pimping.” J Surg Educ. 2015;72(1):176–177.

- Reifler DR. The pedagogy of pimping: educational rigor or mistreatment? JAMA. 2015;314(22):2355–2356.

- Lucey C, Levinson W, Ginsburg S. Medical student mistreatment. JAMA. 2016;316(21):2263–2264.

- Mavis B, Sousa A, Lipscomb W, Rappley MD. Learning about medical student mistreatment from responses to the medical school graduation questionnaire. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):705–711.

- Fnais N, Soobiah C, Chen MH, et al. Harassment and discrimination in medical training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):817–827.

- Williams EA, Miesner AR, Beckett EA, Grady SE. “Pimping” in pharmacy education: a survey and comparison of student and faculty views. J Pharm Pract. 2018;31(3):353–360.

- Angoff NR, Duncan L, Roxas N, Hansen H. Power day: addressing the use and abuse of power in medical training. J Bioeth Inq. 2016;13(2):203–213.

- Scott KM, Caldwell PH, Barnes EH, Barrett J. Teaching by humiliation and mistreatment of medical students in clinical rotations: a pilot study. Med J Aust. 2015;203(4):185–186.

- Lo L, Regehr G. Medical students' understanding of directed questioning by their clinical preceptors. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29(1):5–12.

- Wear D, Kokinova M, Keck-McNulty C, Aultman J. Pimping: perspectives of 4th year medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2005;17(2):184–191.

- Zou L, King A, Soman S, et al. Medical students' preferences in radiology education a comparison between the Socratic and didactic methods utilizing powerpoint features in radiology education. Acad Radiol. 2011;18(2):253–256.

- Parker K, Burrows G, Nash H, Rosenblum ND. Going beyond Kirkpatrick in evaluating a clinician scientist program: it's not “if it works” but “how it works.” Acad Med. 2011;86(11):1389–1396.

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. The prediction of behavior from attitudinal and normative variables. J Exp Social Psychol. 1970;6(4):466–487.

- Slavin SJ, Schindler DL, Chibnall JT. Medical student mental health 3.0: improving student wellness through curricular changes. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):573–577.