ABSTRACT

Background

Medical professionalism education intends to produce virtuous and humanistic healthcare professionals who demonstrate perseverance and professional integrity. However, today’s medicine has embodied a mammoth transformation of medical practice towards sns and the digital realm. Such paradigm shift has challenged the medical professional’s values, behaviors, and identities, and the distinct boundaries between personal and professional lives are blurred. This study aims to develop a framework for healthcare professionals coping with the challenges of medical professionalism in the digital realm.

Methods

We followed a systematic approach for the development of a framework about e-professionalism. Qualitative data was collected from a systematic review and a delphi study, while quantitative data was collected by administering a validated questionnaire social networking sites for medical education (snsme). Subsequently, categorization of the selected data and identifying concepts, deconstruction and further categorizing concepts (philosophical triangulation), integration of concepts (theoretical triangulation), and synthesis and resynthesis of concepts were performed.

Results

The initial process yielded six overlapping concepts from personal, professional, character (implicit) and characteristic (explicit) domains: environment, behavior, competence, virtues, identity, and mission. Further integration of data was done for the development of the medical education e-professionalism (meep) framework with a central concept of a commitment to mission. The mission showed deep connections with values (conformity, beneficence, universalism, and integrity), behaviours (communication, self-awareness, tolerance, power), and identity (reflection, conscientiousness, self-directed, self-actualization). The data demonstrated that all medical professionals require updated expertise in sns participation.

Conclusion

The meep framework recognises a mission-based social contract by the medical community. This mission is largely driven by professional values, behaviors and identity. Adherence to digital standards, accountability, empathy, sensitivity, and commitment to society are essential elements of the meep framework.

Introduction

Medical professionalism is a multifaceted construct that encompasses the expected virtues, behaviours and attitudes of healthcare professionals. Electronic, or e-professionalism entails the attitudes and behaviors described through traditional professionalism strands, that are manifested through SNS [Citation1]. Similarly, digital professionalism, may be considered an interchangeable term with e-professionalism, referring to ‘the use of traditional concepts of medical professionalism while drawing attention to the particular opportunities and challenges afforded by professionals’ use of digital media and how the profession is changed by this use’ [Citation2]. Use of Social Networking Sites (SNS) has expanded, and this phenomenon has catalyzed both the speed and scale of our interactions [Citation3]. Amplified by the power of the Internet and Internet-based technologies, enormous volumes of information and content can be accessed instantly, by individuals and allows interaction with other users. Today’s users of SNS often value speed-of-access to information, rather than accuracy [Citation4]. A plethora of digital interfaces such as vlogs, microblogs, folksonomies, wikis, and other Internet-based applications are being used for marketing, social, and educational purposes [Citation5]. As it stands, the use of SNS has significantly expanded among healthcare professionals, but the education and training of e-professionalism have not advanced reciprocally [Citation6].

In the medical discipline, healthcare professionals use SNS for networking, education, marketing, promotion, patient care and awareness campaigns [Citation7,Citation8]. Healthcare professionals use SNS such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn and WeChat to secure professional relations and communication with patients and their families [Citation9–12]. SNS provide a powerful means for information exchange, immediate access to healthcare information, and even emotional and psychological consultancy [Citation13]. Another outright benefit of SNS comes from its usage for medical research for collecting patient-data, understanding perceptions, and assessing public impact [Citation14,Citation15]. SNS may also provide platforms for medical communities of practice to interact both professionally and socially and provide and receive training and education. However, its usage amongst the medical community becomes sensitive on account of its characteristics of being ‘powerful’, ‘permanent’, and ‘public’ especially as the third party rights of patients are at stake [Citation16].

There are concerns by healthcare professionals that the expanding usage of SNS in the medical field is not without hazards. Despite securing privacy settings, the borderless horizons of the digital world can be accessed by infinite clients in one way or another [Citation17]. Unfortunately, boundaries between professional and personal lives become blurred, and lapses in professional behaviour can result, which can leave both a permanent and very visible digital imprint [Citation18]. A proliferation of reports, have highlighted online violations of professional ethics by medical students, faculty, and healthcare professionals [Citation19]. An example is excessive self-disclosure by healthcare professionals on SNSs, which is considered an utter violation of professional conduct [Citation20]. A large body of literature has reported the illegal posting of patients’ photos and personal data by healthcare professionals, often without explicit consent, which can adversely affect patient–doctor relationships [Citation21]. The American Medical Association has warned that the ubiquitous use of SNS by healthcare professionals has resulted in an information ecosystem that contains true and false information, with the potential to confuse or misinform patients and the public [Citation21]. Such ‘Fake news’, disinformation, or poor-quality health information can undermine patients’ confidence in healthcare professionals and the profession. Furthermore, unprofessional acts witnessed on SNS by healthcare professionals have included venting, profanity, discriminatory language, and inappropriate remarks about patients [Citation22]. Clearly, these should not be tolerated in either the physical or virtual world.

Although there is a staggering rise of SNS usage among healthcare professionals, patients, and their families, little is known of the impact this has had on privacy, confidentiality, and other important aspects of our professional codes of conduct. The concept of e-professionalism is still in its’ infancy in the medical field, and policies for the use of SNS amongst medical professionals are considered primitive and rudimentary [Citation23]. In order to address the ethical conduct of healthcare professionals, three separate frameworks have been published which focus on different constructs of medical professionalism. First, the virtue-based professionalism framework focuses on moral character and reasoning with an emphasis on a set of values steered by moral reasoning [Citation24]. Second, the behaviour-based professionalism framework relies on professional milestones and competencies, which appreciates correct behaviors and applies sanctions to unprofessional behaviors [Citation25,Citation26]. Third, the professional identity formation (PIF) based framework recognizes the importance of positive role models and has the ability to alert healthcare professionals about the occurrence of negative role models [Citation27]. However, these three diverse approaches have not yet been unified into a single coherent framework for medical professionals that describes the expected professional virtues, behaviors and identity in respect to e-Professionalism. Furthermore, the rapidly evolving landscape of SNS, and digital communication, brings repeated challenge to embrace new methods of communication, representation and conduct. In this context, there is no current framework of medical professionalism that can address the new discourse of e-professionalism.

This study aims to develop a Medical Education e-Professionalism (MEeP) framework which can describe healthcare professionals’ expected conduct using SNSs. This will help us to understand the complexity of e-professionalism, the issues related to the blurring of personal and professional boundaries and arising from liberal information sharing. We have attempted to incorporate professional values, behaviours, and identity from the digital realm in a single framework that complement, and help unify, three separate construct-based professionalism frameworks.

Study design

We designed our study strategy by using the research philosophy of Bilau et al., which uses three fundamental steps for conducting a framework-developing investigation [Citation28]. This approach included; ontology, the perception of being subjective or objective in the real world; epistemology, the realm of understanding from reflections; and axiology, the researchers’ persona of opinions and beliefs. Integrating these three legacies, we performed a deductive (rigorous evaluation of several propositions emerging from theory) as well as inductive (analysis of a given phenomenon by recognition of themes and trends) approaches in our study [Citation29].

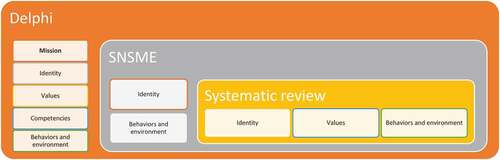

We conducted this study by performing a systematic review for an in-depth analysis of the published literature, a survey-based investigation using a validated inventory Social Networking Sites for Medical Education (SNSME) [Citation30,Citation31], and performing a Delphi study for capturing the experts’ opinions. outlines our research philosophy and paradigms, including research questions for developing the Medical Education e-Professionalism (MEeP) framework.

Table 1. Research philosophy and paradigms

Systematic Review [Citation32]

We used Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for data mining and selection of the studies for this systematic review [Citation33]. Our research questions were based on Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation and Research type (SPIDER) [Citation34]. We looked into the published literature for the desired values and behaviors for a digital professional identity formation and the impact of SNS in an educational setting. On 11 May 2020, we performed a search on PubMed, ProQuest, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, and EBSCO host using keywords (professionalism AND (professionalism OR (professional identity) OR (professional behaviors) OR (professional values) OR (professional ethics) AND (SNS) AND (SNS) OR (social networking sites) OR Twitter® OR Facebook® OR Instagram® OR WeChat®) AND (healthcare professionals) for the English-language articles published between 1 January 2015 and 30 April 2020 (Appendix 1). We defined our sample ‘healthcare professionals’ as individuals engaged in the delivery of the healthcare system, including healthcare professionals, nurses, dentists, physiotherapists, and pharmacists. The phenomenon of interest was defined as the digital world including SNS, social networking sites, Twitter®, Facebook® and Instagram®, and WeChat®. The original research articles with qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies about digital professionalism, e-professionalism in the digital age, guidelines for the usage of SNS, and the degree and extent of usage of SNS by healthcare professionals for educational, professional and personal purposes were included. We excluded systematic reviews, scoping reviews, meta-analysis, editorials, and commentaries from our search. While the thematic analysis was used for emerging concepts and theories, the leading themes and concepts were further analyzed in discussion to reach consensus for future implementation. For the analysis itself, the SSG and SYG coded all articles and constructed a coding tree. Later on, other investigators critically analyzed and selected final themes about digital professionalism.

Survey-based research

The SNSME questionnaire was distributed to all undergraduate medical students at the Royal College of Surgeons Ireland – Medical University of Bahrain (RCSI-MUB) through SurveyMonkey®. The medical curriculum at RCSI-MUB is delivered in a six-year programme, comprising Foundation Year till year 5. The curriculum is the same as the one delivered in RCSI Dublin [Citation35]. The students are from 38 nationalities giving a very diverse and multicultural aspect to the student cohort. The SNSME inventory contains 29 questions about the frequency and type of personal electronic communication for the general, educational and professional use of SNS (e.g., Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, LinkedIn, WeChat, and Flickr) on a 5-point Likert agreement scale (Appendix 2). There was one open-ended question about the participants’ opinions about e-professionalism in SNS. The data analysis was done using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) v.20. As all statements were arranged on an ordinal scale, inferential statistics were performed by non-parametric tests. As a prerequisite to using other non-parametric tests, the normality of data was verified by a one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the differences between genders, while the Kruskal Wallis test was applied to compare the differences between more than two independent groups. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

Delphi technique

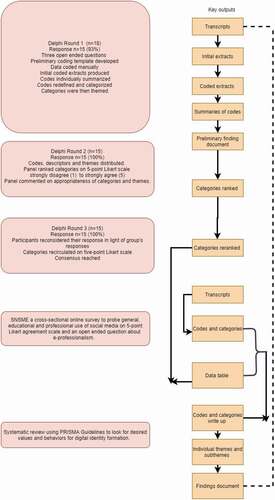

Delphi technique collects anonymous opinions from a panel of experts to forecast future trends on a given research topic [Citation36]. The process starts with Delphi questions which focus on identifying problems and tangible solutions. The research statements and concerns for the subsequent rounds are generated from the responses of preceding rounds. The process comes to an end on receiving answers to the research question. In our research, a representative group of 36 experts on SNS usage, professionalism and e-professionalism traits from different regions, nationalities, ethnicity and culture were invited to contribute to the Delphi study on e-professionalism. The expert panel was recruited by using the maximum variation sampling technique [Citation37]. Participants were required to respond across all three rounds to complete the Delphi process. A dropout rate of 20% was expected over the three rounds. Upon agreement, round 1 questionnaire was administered via SurveyMonkey®, which asked for single words or short statements (descriptors) to be submitted against each of the following three questions:

1. Who is the Man (Person) of character in the digital world?

2. Who is the Man (Person) of characteristics in the digital world?

3. How is professional identity acquired in the digital world?

During round 2, the descriptors were grouped into categories which were then classified into themes [Citation38]. All descriptors, categories, and themes were distributed to the expert panel to rank from strongly disagree to strongly agree. There was no option for free-text responses in round 2. The returned rankings of the expert panel were manually analyzed. In round 3, each participant received an individualized survey comprising all categories, which were presented alongside the participants’ own responses and the group’s responses (percentage agreement/disagreement) from round 2. Participants were asked to reconsider their responses in the light of the group’s responses for a final review and opinion. A consensus on essential values and behaviours leading to PIF in the digital world was sought.

To develop the framework using the data from the three studies, we followed a structured process using a grounded theory approach, which suggested a continuous interplay between data and analysis [Citation39,Citation40]. During this process the results were identified as being in agreement (convergence), offering complementary information on the same topic (complementarity), or appearance of information contradicting each other (discrepancy or dissonance) [Citation41].

Mapping the selected data sources

Extensive reading, categorization of the selected data, and identification of concepts

Mapping of concepts across studies – philosophical triangulation

Integration of concepts – theoretical triangulation

Synthesis, resynthesis, and making it all make sense – Development of the MEeP framework

Ensuring research rigor

We followed the four standard steps by Lincoln and Guba 1994 [Citation42] for ensuring research rigor; credibility, transferability, dependability, and conformability. These included administration of relevant questions with a detailed context (credibility), theoretical underpinnings of our findings that can be generalized by other researchers for their studies (transferability). We integrated methods and results (dependability) and reduced researchers’ bias by an iterative approach of data analysis during different stages of the research to ensure that results were not unduly swayed (conformability).

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the University Sains Malaysia (USM/JEPeM/19050291) and by the Royal College of Surgeons Ireland Medical University Bahrain (RCSI-MUB/REC/15032020). All participants provided informed consent to participate at the beginning of the online survey and in the Delphi process. All data were handled in accordance with the European General Data Protection Regulation [Citation43] as well as all relevant regulations and Data Protection legislation in Bahrain.

Results

Mapping the selected data sources

A mapping of the collected evidence was carried out by triangulation of the retrieved data from a methodological perspective. ()

Figure 1. A structured algorithm of methodological triangulation of scoping review, SNSME survey and Delphi study

The systematic review initially yielded 4055 references. Further analysis shortlisted 44 articles for further analysis. Most studies were based in the USA (15/34%), while other studies were based in Canada (8/18%), UK (4/9%), China (3/7%), UAE (3/7%), and New Zealand (1/3%). The staged analysis of the selected studies generated four leading threads; (1) an escalating rise in the use of SNS by healthcare professionals and students, (2) a negative impact of SNS on digital professionalism, (3) blurring of medical professional values, behaviors, and identity in the digital era, and (4) a shred of limited evidence for teaching and assessing digital professionalism. A high occurrence of a violation of patient privacy and professional integrity and cyberbullying was observed.

Of 977 invitees, 381 [244 (64%) female and 137 (36%) male] responded to the SNSME survey (a response rate of 39%). The majority of respondents 213 (56%) were in the age group 18–20 years, 122 (32%) students were in 21–23 years, and 46 (12%) students were older than 23 years. The data showed that there were 59 (15.4%) students from foundation year, 75 (19.6%) students from 1st year, 49 (12.9%) students from 2nd year, 74 (19.5%) students from 3rd year, 64 (16.9%) students from 4th year, and 60 (15.7%) 5th year students. The majority (105; 27.6%) students used email once a week to share educational material, while 223 (58.6%) students used SNS to remain in touch with their peers and tutors. Interestingly, 88 (23%) students used SNS for sharing education-related information 3 to 5 times a day. As many as 109/381 (28.7%) students did not get any formal instructions for the use of SNS by their institution, while only 118/381 (31%) were aware of a formal SNS policy. Generally, though the use of SNS for leisure and fun was high, the students were not aware of its code of conduct and legislative complexities (Appendix 3 and Appendix 4). Using the Mann-Whitney U test for the comparison of genders’ responses, showed a significant variation in two statements (p < 0.05). The responses of male students were significantly in favour of the statement ‘social networking sites help me access educational resources’ with a high mean rank of 147.13 compared to 121.39 mean rank for female students. In contrast, female students’ responses significantly favoured the statement ‘I have posted content (images/videos/text) on SNS that could be considered unprofessional’ than the male counterparts, mean ranks of 140.69 and 113.20, respectively. Comparing the students’ responses across years of schooling, the results of Kruskal Wallis test showed significant differences for two statements for educational use of SNS, and one statement for professional use of SNS, respectively (p < 0.05). The most significant difference was noted for the statement ‘social networking sites are useful in developing reading and writing web skills’, where senior students agreed much more than the junior students. The responses to the open-ended question of the SNSME inventory highlighted the importance of being honest, responsible, and possess good communication and interpersonal skills. ‘User ratings’ and the complexity of acquiring an appropriate digital identity were prominent.

In the Delphi study, of the 36 invited experts, 18 participants completed round 1 (response rate 50%), 15 of 18 completed round 2 (response rate 83.3%), and 15 of 15 completed round 3 (response rate 100%). Approximately 118 descriptors were analyzed and were subsumed into 39 categories which generated 13 themes (Appendix 5). The number of categories with strongly agree consensus improved significantly for each theme from rounds 2 to 3. In round 2, 100% consensus was achieved for 20/39 (51.2%) categories, which rose to 100% for all categories in round 3. The identified themes were categorised as follows.

Conformity: self-restraint and subordination of one’s own inclinations to the expectations of others

Benevolence: preserve and enhance welfare of those with whom one is in frequent personal contact

Power: status and prestige, control people and resources

Self-direction: autonomous thought and action (idea of agency)

Universalism: tolerance and concern for welfare of all others

Achievement: competitive personal success

Honest

Responsible

Self-aware

Reflective

Conscientious

Altruistic

Communicator

Extensive reading, categorization of the selected data, and identification of concepts

We applied a bottom-up approach, and the discrete findings were linked with each other, thus classifying patterns and identifying unique concepts [Citation44]. We analyzed the data from systematic review, SNSME survey, and Delphi study, where recurring descriptors and categories were generated carrying common links with themes by SSG and SYG. These descriptors, categories and themes were further cross verified and validated by other four authors DWH, AR, MZN and MSBY. An excerpt, of quotations from different studies is presented in a tabular format as Appendix 6

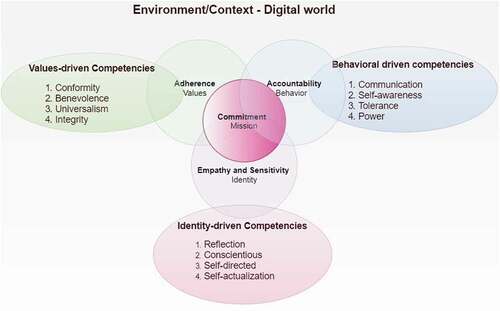

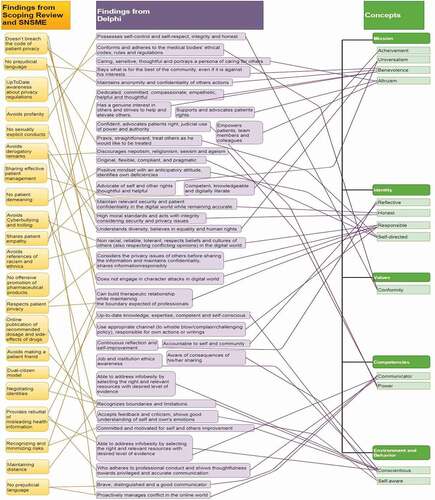

During this data analysis process, the bespoke relevance of categories and themes emerged as concepts; digital environment, behaviours, competencies, values, identity, and mission. Interestingly, though not intended purposefully, the concepts of our research analysis fit closely with Korthagen’s model of change [Citation45]. A comprehensive demonstration of the phased emergence of concepts and their integration towards the conceptual analysis is shown in .

Figure 2. A structured layout of the phased emergence of concepts of e-professionalism and their integration towards the MEeP framework

We considered the identified concepts. The digital environment was considered as fluid, diverse, autonomous, and connected. The Behaviors, as the correct conduct in the digital environment, which in turn is heavily influenced by Competencies, which constitute the knowledge, skills, and attitudes which determine the potential for correct conduct. Values and beliefs reflect the degree of conscious awareness of one’s abilities and knowledge of digital world. Identity pertains to personal and professional characteristics, values, and norms; the ‘who am I: personal and professional self’. Finally, Mission, signifies the driving force that fosters a specific role of self, or ‘status’.

Mapping of concepts across studies – philosophical triangulation

Data from systematic review and SNSME deduced idealism, interpretive, and value-laden characteristics of a healthcare professional in the digital world. In contrast, the data from Delphi study valued realism, pragmatism and value-free traits of e-professionalism in the medical field. The concept mapping from systematic review, SNSME survey, and Delphi study highlighted the overlapping similarities except for mission that emerged from Delphi study only. The outcome of triangulation from each study is shown in .

Integration of concepts – theoretical triangulation

At this stage, we integrated the collected concepts with theoretical perspectives. This exercise showed six concepts from personal and professional paradigm. Values, identity and mission represent implicit aspects, while competencies and behaviours in environment are more explicit expressions. Individuals relate to each other in different social roles; hence the concept of personal and professional identity emerges. At the same time, a continuous presentation of ‘Professional self’ can undermine personal identity formation, which was not the case in the pre-internet world. Henceforth there is a need for a single identity in the digital world as there are no personal and professional boundaries. That digital identity can be achieved if one has the driving force and commitment that fosters a specific role of ‘self’.

Synthesis, resynthesis, and making it all make sense – Development of framework

Following an iterative process of synthesis and resynthesis, the researchers reached a consensus to develop the MEeP framework ().

The iterative nature of data analysis from these different lenses emphasized, the complexities of the digital world, and that mere alignment of all these concepts could not attain the mission. Instead the three essential concepts; of values, behavior and identity need to complement each other and converge on a cynosure; a ‘Mission.’ That Mission, a commitment to the social contract of a medical professional with society, intertwining professional values (adherence to standards), behaviors (accountability) and identity (empathy and sensitivity). To achieve that mission, a specific set of competencies are required from all three levels.

Discussion

This study represents a structured approach to the development of a unifying Medical Education e-Professionalism (MEeP) Framework for the digital realm. The mainstay of the framework is the ‘Mission’, – a commitment by the medical profession to society through a social contract to deliver healthcare services with appropriate professional values, behaviors and identity. The MEeP framework addresses the medical mission, reflecting a list of competencies () that can be used by academics for curricular reforms and by learners for their own self-assessment and reflection. In the pursuit of this mission, in the digital-era healthcare professionals should preserve and embody professional values, behaviors, and identities. Medical professionalism incorporates a code of healthcare ethics and constitutes the execution of professional virtues in practice. Virtues which demonstrate an intermix of values, attitudes, and behaviors to promote a patient-centered and compassionate care, delivered through perseverance and with integrity [Citation24]. Correspondingly, our framework has revealed a special symbiotic relationship between our commitment to mission and adherence to standards (values), accountability (behaviors), and empathy and sensitivity (identity). This mission based MEeP framework is further interconnected with competencies from values, behaviors, and identity that when embraced may assist healthcare professionals as they carefully navigate their conduct through the digital world.

Medical professionalism has a fundamental ethos of morality, which underpins the need to understand the Man (Person) of character and the Man (Person) of characteristics who is deciding or executing crucial actions in the digital realm. In this digital environment, the attention capacities, memory process, and social cognition have profoundly deteriorated [Citation46]. Continuous presence in the digital environment has been shown to exhaust cognitive reserves and undermine neuro-cognitive outcomes leading to impaired impulse-control and decision-making [Citation47]. These mechanisms predict the social behaviors of Internet users and may also potentially influence behaviors of healthcare workers on SNS. While developing a narrative-based framework for medical professionalism, Dr Jack Coulehan has asserted the need for a technical professional identity [Citation48]. If we accept this narrative, tech-savvy and digitally expert medical professionals would be preferred in the modern world as they may be better equipped to recognize personal and professional territories without endangering patient’s integrity, privacy, and social norms [Citation49]. Similarly, self-awareness and narrative competence are considered to be essential facets in fostering healthcare workers’ fitness to practice [Citation50]. Our framework brings up the role of a medical professional by being mindful of the expected professional values, behaviors, and identities. The MEeP framework advocates that being a Man (Person) of character, a healthcare worker would acquire competencies of professional values (conformity, benevolence, universalism, integrity) while interacting with colleagues, patients and their families, and community stakeholders. On the other hand, being a Man (Person) of characteristics, a healthcare professional is accountable for communication, self-awareness, tolerance and self-restrained in the digital world.

An essential construct of our MEeP mission-based framework is based on professional behaviors in the digital realm. Healthcare professionals’ behaviors in the digital environment may not predict the healthcare professionals’ behaviors in the physical environment; they may be professionally sound in the hospitals while they may behave unprofessionally on SNS. An example is the online sharing of a patient’s picture or a part of the body without formal consent. According to the theory of connectivism, SNS usage is impulsive, uninhibited, and immersive [Citation51,Citation52]. There is a thin line between personal and professional landscapes in SNS, and that’s where infringements of professional behaviors can occur. The ubiquity of the Internet access and its’ numerous intersections with diverse professional activities such as communication, consultations, awareness, and accountability mean digital professionalism should be folded into modern medical competencies and entrustable professional activities [Citation2]. There is a pressing need to embed a thread of core principles of e-professionalism into the fabric of all medical curriculum, for undergraduate, postgraduate and continued professional education.

We have viewed the main concepts from both personal and professional paradigms. When examined through the optics of identity in the digital era, Holden at al., have argued that a gap exists in the conduct of a virtuous person between his (their) physical and online space [Citation53]. Knight and Mattick, have eluded that the epistemological perceptions of medical students and healthcare workers gradually evolve by experience, incremental self-awareness, and self-identities with a resultant PIF [Citation54]. It follows therefore, since such experiences are not consistent, that the various incongruous events individual may encounter will result in ‘identity patching’ with deficits in some perhaps crucial areas. With further experience, medical professionals tend to secure ‘identity splinting’ where their PIF supports their patched identity to minimise those deficits. These phenomena become crucial in the digital world as we experience a context collapse, which denotes a widening aperture between physical and cyberspace [Citation55]. Context collapse takes place when heterogeneous groups, content, and moral values from diverse settings converge through SNSs [Citation56]. Henceforth, an understanding of the environment (contextualized work) plays a vital role in mitigating the risk of collapsed contexts. Otherwise, this phenomenon can flatten versatile audiences into a common group with a weak situation-specific dimension of PIF. There is a wealth of research about the blurring of contextual boundaries while using SNSs by medical professionals [Citation3,Citation31,Citation57]. This highlights how the personal and professional aspects of one’s life can be managed in the co-existence of physical space. However, once the environment is devoid of this buffering effect, the pervasive context collapse blurs this separation in the digital world. Although numerous strategies to offset this contextual collapse are used, such as self-disclosures, self-censorship, audience-specific digital adaptations, and privacy settings, there remain situations where online presence is inappropriate in terms of values, competencies, behaviors, and identities. The between and betwixt; a liminal approach [Citation58] cannot work in the digital realm and demands an early convergence and alignment of multiple identities to one ‘Self’ to ‘Status’ [Citation59]. Where status may equate to our ‘Mission’ – a conception of self-existence. That’s how the concept of ‘Mission’ emerged in our study, which remains unchanged irrespective of the digital or physical environment.

Analysing mission from a different perspective, the Hippocratic oath eloquently testifies that, carrying a noble mission, a medical graduate will embrace universal ethics, beneficence, and non-maleficence [Citation60,Citation61]. However, in the digital world, preserving professional identity and self-presentation during interactions on SNS has shown precarious instances of how healthcare professionals construe their conduct [Citation62]. Beneficence might have been preserved in the physical world, but, unknowingly, a physician might have posted a patient’s details on SNSs with an infringement of codes of confidentiality and privacy. This brings up the value of the MEeP framework to revisit the professional identities while adhering to the core mission of medicine [Citation63–65]. As evident from the literature, SNS has transformed the medical field into a web-based avenue for PIF and socialization [Citation66]. There is a need to cultivate a presentation of self that is devoid of personal and professional aspects, but at the same time meet the demands of both.

The aforementioned concepts with theoretical and philosophical triangulations have helped us to develop the mission based MEeP framework, which focuses on singularity rather than a plurality of the individual. For healthcare professionals, the core tenets of e-professionalism, including reflections, caring, conscientiousness, accountability, and commitment to duty, should be mastered along with a sound knowledge of SNS. Alignment of such sets of competencies with the digital environment, which is impulsive, intercultural, and powerful, will diversify the scope of medical professionals. Currently, there is a scarcity of instructions and guidelines in medical curricula about the professional use of SNS in the digital realm. Our study demands formal training and evaluation of the medical trainees and professionals to prepare them for their future digitally enhanced medical practice.

Considerations for Implementation

Due to the complex nature of teaching behavioural skills, more novice learners can be educated about the professional mission and identity (status and self) components of the framework by introducing exercises which focus on self-reflection and self-actualization. Once the learners grasp the main concepts of the medical profession’s mission and their own professional identities, the value-driven components of the MEeP framework (e.g., conformity, integrity and benevolence) can be introduced into the curriculum. Vertical integration of MEeP framework components is recommended and will reinforce concepts for learners.

Study limitations

This study used a diverse range of research methodologies to triangulate and analyse data. The research design is a kind of mixed methods protocol where both quantitative and qualitative approaches were adopted. Despite a thorough protocol, the chances of eliminating research bias cannot be guaranteed. More evidence-based multi-centre studies on this novel phenomenon would be advantageous. We didn’t explicitly used TikTok in our search strategy.

Conclusion

This study has developed a novel and unifying mission-based Medical Education e-Professionalism (MEeP) Framework, which focuses on the core principles of professionalism and the duties of our social contract. Recognizing that SNS, due to online disinhibition and both reach and permanency of digital footprint, are challenging environments for the maintenance of appropriate professional values, behaviors, and identities. Henceforth, we propose that our MEeP framework may guide the acquisition of necessary competencies of e-Professionalism and enable us to fulfill our commitments to society through the creation of an appropriate ‘one own self’ in the digital environment. This framework can be conveniently adopted by medical institutions and healthcare authorities to guide healthcare professionals in the digital realm for the acquisitions of desired attributes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cain J, Romanelli F. E-professionalism: a new paradigm for a digital age. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2009;1(2):66–25.

- Ellaway RH, Coral J, Topps D, et al. Exploring digital professionalism. Med Teach. 2015;37(9):844–849.

- Guraya SY. The usage of social networking sites by medical students for educational purposes: a meta-analysis and systematic review. N Am J Med Sci. 2016;8(7):268.

- Desai SP, Lele V. Correlating internet, social networks and workplace-a case of generation Z students. J Comm Manage Thought. 2017;8(4):802.

- Goldie JGS. Connectivism: a knowledge learning theory for the digital age? Med Teach. 2016;38(10):1064–1069.

- Fenwick T, Edwards R. Exploring the impact of digital technologies on professional responsibilities and education. Europ Educat Res J. 2016;15(1):117–131.

- Zimba O, Radchenko O, Strilchuk L. Social media for research, education and practice in rheumatology. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40(2):183–190.

- Alhusseini N, Banta JE, Oh J, et al. Social Media Use for Health Purposes by Chronic Disease Patients in the USA. Saudi J Med Med Sci. 2021;9(1):51.

- Hill SS, Dore FJ, Steven TE, et al. Twitter use among departments of surgery with general surgery residency programs. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(1):35–42.

- Alleje ML, Austria BC, Shrestha PA. Social media etiquette in medicine. Br J Hosp Med. 2019;80(9):130–132.

- Luan H, Wang M, Sokol RL, et al. A scoping review of WeChat to facilitate professional healthcare education in Mainland China. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1):1782594.

- Zeng F, Deng G, Wang Z, et al. WeChat: a new clinical teaching tool for problem-based learning. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:119.

- Eghtesadi M, Florea A. Facebook, Instagram, Reddit and TikTok: a proposal for health authorities to integrate popular social media platforms in contingency planning amid a global pandemic outbreak. Can J Public Health. 2020;111:389–391.

- Bour C, Schmitz S, Ahne A, et al. Scoping review protocol on the use of social media for health research purposes. BMJ Open. 2021;11(2):e040671.

- Singh T, Roberts K, Cohen T, et al. Social Media as a Research Tool (SMaaRT) for risky behavior analytics: methodological review. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(4):e21660.

- Spector ND, Matz PS, Levine LJ, et al. e-Professionalism: challenges in the age of information. J Pediatr. 2010;156(3):345–346.

- Seidel RL, Jalilvand A, Kunjummen J, et al. Radiologists and social media: do not forget about Facebook. J Am College Radiol. 2018;15(1):224–228.

- Patel MS, Davis MM, Lypson ML. Advancing medical education by teaching health policy. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(8):695–697.

- Monrouxe LV. Identity, identification and medical education: why should we care? Med Educ. 2010;44(1):40–49.

- Gholami-Kordkheili F, Wild V, Strech D. The impact of social media on medical professionalism: a systematic qualitative review of challenges and opportunities. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(8):e184.

- Chou W-YS, Oh A, Klein WM. Addressing health-related misinformation on social media. Jama. 2018;320(23):2417–2418.

- Peck JL. Social media in nursing education: responsible integration for meaningful use. J Nurs Educ. 2014;53(3):164–169.

- Muls J, Thomas V, De Backer F, et al. Identifying the nature of social media policies in high schools. Educat Inform Technol. 2020;25(1):281–305.

- Brody H, Doukas D. Professionalism: a framework to guide medical education. Med Educ. 2014;48(10):980–987.

- Billett S. Cooke, M., Irby, DM & O’Brien, BC. Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

- Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, Holmboe ES, Carraccio C, Swing SR, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638–645.

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, et al. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: a guide for medical educators. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):718–725.

- Bilau AA, Witt E, Lill I. Research methodology for the development of a framework for managing post-disaster housing reconstruction. Procedia Eng. 2018;212:598–605.

- Corti L. The European landscape of qualitative social research archives: Methodological and practical issues. InForum: Qualitative Social Research 2011 (Vol. 12, No. 3). FQS.

- Guraya SY, Almaramhy H, Al-Qahtani MF, et al. Measuring the extent and nature of use of Social Networking Sites in Medical Education (SNSME) by university students: results of a multi-center study. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(1):1505400.

- Guraya SY, Al-Qahtani MF, Bilal B, et al. Comparing the extent and pattern of use of social networking sites by medical and non medical university students: a multi-center study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:575.

- Guraya SS, Guraya SY, Yusoff MSB. Preserving professional identities, behaviors, and values in digital professionalism using social networking sites; a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):1–12.

- Guraya S. Prognostic significance of circulating microRNA-21 expression in esophageal, pancreatic and colorectal cancers; a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2018;60:41–47.

- Cooke A, Smith D, Beyond BA. PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–1443.

- Morgan MP, Thomas W, Rashid-Doubell F. Academic staff perspectives on delivering a shared undergraduate medical module on three transnational campuses: practical considerations and lessons learned. Med Teach. 2020;42(1):36–38.

- Hsu -C-C, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12(1):10.

- List D. Maximum variation sampling for surveys and consensus groups. Adelaide: audience Dialogue. J Qualitat Res EducatJOQRE. 2004.

- Saldana J. Analyzing longitudinal qualitative observational data. Handbook of longitudinal research: design, measurement, and analysis. 2008;297–311.

- Watling CJ, Lingard L. Grounded theory in medical education research: AMEE Guide No. 70. Med Teach. 2012;34(10):850–861.

- Farmer T, Robinson K, Elliott SJ, et al. Developing and implementing a triangulation protocol for qualitative health research. Qual Health Res. 2006;16(3):377–394.

- Foster RL. Addressing epistemologic and practical issues in multimethod research: a procedure for conceptual triangulation. Adv Nurs Sci. 1997;20(2):1–12.

- Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handbook Qualitat Res. 1994;2(163–194):105.

- Yuan B, Li J. The policy effect of the general data protection regulation (GDPR) on the digital public health sector in the european union: an empirical investigation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(6):1070.

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, and Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). London, UK: Sage publications; 2014.

- Korthagen FA. In search of the essence of a good teacher: towards a more holistic approach in teacher education. Teaching Teacher Educ. 2004;20(1):77–97.

- Choudhury S, McKinney KA. Digital media, the developing brain and the interpretive plasticity of neuroplasticity. Transcult Psychiatry. 2013;50(2):192–215.

- Firth J, Torous J, Stubbs B, et al. The “online brain”: how the Internet may be changing our cognition. World Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):119–129.

- Coulehan J. Today’s Professionalism: engaging the Mind but Not the Heart. Acad Med. 2005;80(10):892–898.

- Schenarts PJ. Now arriving: surgical trainees from generation Z. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(2):246–253.

- Jha V, Brockbank S, Roberts T. A framework for understanding lapses in professionalism among medical students: applying the theory of planned behavior to fitness to practice cases. Acad Med. 2016;91(12):1622–1627.

- Crone EA, Konijn EA. Media use and brain development during adolescence. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1–10.

- PrakashYadav G, Rai J. The Generation Z and their social media usage: a review and a research outline. Global J Enterprise Inform Syst. 2017;9(2):110–116.

- Holden M, Buck E, Clark M, Szauter K, Trumble J.Professional identity formation in medical education: The convergence of multiple domains. HEC Forum. 2012;24:245–255.

- Knight LV, Mattick K. ‘When I first came here, I thought medicine was black and white’: making sense of medical students’ ways of knowing. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(4):1084–1096.

- Davis JL, Jurgenson N. Context collapse: theorizing context collusions and collisions. Inform Comm Soc. 2014;17(4):476–485.

- Marwick AE, Boyd D. I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Med Soc. 2011;13(1):114–133.

- Kesselheim JC, Batra M, Belmonte F, et al. New professionalism challenges in medical training: an exploration of social networking. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(1):100.

- Gordon L, Rees CE, Jindal‐Snape D. Doctors’ identity transitions: choosing to occupy a state of ‘betwixt and between’. Med Educ. 2020;54(11):1006–1018.

- Bergner RM, Holmes JR. Self-concepts and self-concept change: a status dynamic approach. Psychotherapy. 2000;37(1):36.

- Antoniou SA, Antoniou GA, Granderath FA, et al. Reflections of the Hippocratic Oath in modern medicine. World J Surg. 2010;34(12):3075–3079.

- Kohlberg L, Hersh RH. Moral development: a review of the theory. Theory into Pract. 1977;16(2):53–59.

- O’Regan A, Smithson WH, Spain E. Social media and professional identity: pitfalls and potential. Med Teach. 2018;40(2):112–116.

- Erikson EH. Eight ages of man. Int J Psychiat. 1966.

- Marcia JE. Development and validation of ego-identity status. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1966;3(5):551.

- Van Der Zwet J, Zwietering P, Teunissen P, et al. Workplace learning from a socio-cultural perspective: creating developmental space during the general practice clerkship. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2011;16(3):359–373.

- Ruan B, Yilmaz Y, Lu D, et al. Defining the Digital Self: a Qualitative Study to Explore the Digital Component of Professional Identity in the Health Professions. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9):e21416.

Appendix 1.Search strategy – PUBMED 12 May 2020 (n = 1388)

Search: (((((((Professionalism) OR (‘professionalism’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘professionalism/education’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘professionalism/ethics’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘professionalism/trends’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘professionalism/standards’[MeSH Terms])) OR (professional attributes)) OR (professional values)) OR (professional behaviors)) OR (professional identity)) AND ((((SNS) OR (‘SNS’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘SNS/ethics’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘SNS/standards’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘social networking’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘social networking/ethics’[MeSH Terms])) OR (Twitter)) OR (facebook))) AND (healthcare professionals) Filters: Journal Article, from 2015–2020

((((((((((((((((‘professional’[All Fields] OR ‘professional s’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalism’[MeSH Terms]) OR ‘professionalism’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionality’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalization’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalize’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalized’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalizing’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionally’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionals’[All Fields]) OR ((((‘professionalism’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘professionalism/education’[MeSH Terms]) OR ‘professionalism/ethics’[MeSH Terms]) OR ‘professionalism/trends’[MeSH Terms]) OR ‘professionalism/standards’[MeSH Terms])) OR (((((((((((‘professional’[All Fields] OR ‘professional s’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalism’[MeSH Terms]) OR ‘professionalism’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionality’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalization’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalize’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalized’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalizing’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionally’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionals’[All Fields]) AND ((((((((‘attributable’[All Fields] OR ‘attribute’[All Fields]) OR ‘attribute s’[All Fields]) OR ‘attributed’[All Fields]) OR ‘attributes’[All Fields]) OR ‘attributing’[All Fields]) OR ‘attribution’[All Fields]) OR ‘attributional’[All Fields]) OR ‘attributions’[All Fields]))) OR (((((((((((‘professional’[All Fields] OR ‘professional s’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalism’[MeSH Terms]) OR ‘professionalism’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionality’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalization’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalize’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalized’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalizing’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionally’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionals’[All Fields]) AND (‘value’[All Fields] OR ‘values’[All Fields]))) OR (((((((((((‘professional’[All Fields] OR ‘professional s’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalism’[MeSH Terms]) OR ‘professionalism’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionality’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalization’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalize’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalized’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalizing’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionally’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionals’[All Fields]) AND (((((((((((((((((‘behavior’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘behavior’[All Fields]) OR ‘behavioral’[All Fields]) OR ‘behavioural’[All Fields]) OR ‘behavior s’[All Fields]) OR ‘behaviorally’[All Fields]) OR ‘behaviour’[All Fields]) OR ‘behaviourally’[All Fields]) OR ‘behaviours’[All Fields]) OR ‘behaviors’[All Fields]) OR ‘pattern’[All Fields]) OR ‘pattern s’[All Fields]) OR ‘patternability’[All Fields]) OR ‘patternable’[All Fields]) OR ‘patterned’[All Fields]) OR ‘patterning’[All Fields]) OR ‘patternings’[All Fields]) OR ‘patterns’[All Fields]))) OR (((((((((((‘professional’[All Fields] OR ‘professional s’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalism’[MeSH Terms]) OR ‘professionalism’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionality’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalization’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalize’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalized’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionalizing’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionally’[All Fields]) OR ‘professionals’[All Fields]) AND (‘identities’[All Fields] OR ‘identity’[All Fields]))) AND (((((‘SNS’[MeSH Terms] OR (‘social’[All Fields] AND ‘media’[All Fields])) OR ‘SNS’[All Fields]) OR ((((‘SNS’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘SNS/ethics’[MeSH Terms]) OR ‘SNS/standards’[MeSH Terms]) OR ‘social networking’[MeSH Terms]) OR ‘social networking/ethics’[MeSH Terms])) OR ((‘twitter’[All Fields] OR ‘twitter s’[All Fields]) OR ‘twitters’[All Fields])) OR (“facebook “[All Fields]))) AND ((((‘health personnel’[MeSH Terms] OR (‘health’[All Fields] AND ‘personnel’[All Fields])) OR ‘health personnel’[All Fields]) OR (‘health’[All Fields] AND ‘professionals’[All Fields])) OR ‘healthcare professionals’[All Fields])

Translations

Professionalism: ”professional”[All Fields] OR ‘professional’s’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalism’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘professionalism’[All Fields] OR ‘professionality’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalization’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalize’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalized’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalizing’[All Fields] OR ‘professionally’[All Fields] OR ‘professionals’[All Fields]

professional: ”professional”[All Fields] OR ‘professional’s’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalism’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘professionalism’[All Fields] OR ‘professionality’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalization’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalize’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalized’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalizing’[All Fields] OR ‘professionally’[All Fields] OR ‘professionals’[All Fields]

attributes: ”attributable”[All Fields] OR ‘attribute’[All Fields] OR ‘attribute’s’[All Fields] OR ‘attributed’[All Fields] OR ‘attributes’[All Fields] OR ‘attributing’[All Fields] OR ‘attribution’[All Fields] OR ‘attributional’[All Fields] OR ‘attributions’[All Fields]

professional: ”professional”[All Fields] OR ‘professional’s’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalism’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘professionalism’[All Fields] OR ‘professionality’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalization’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalize’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalized’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalizing’[All Fields] OR ‘professionally’[All Fields] OR ‘professionals’[All Fields]

values: ”value”[All Fields] OR ‘values’[All Fields]

professional: ”professional”[All Fields] OR ‘professional’s’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalism’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘professionalism’[All Fields] OR ‘professionality’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalization’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalize’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalized’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalizing’[All Fields] OR ‘professionally’[All Fields] OR ‘professionals’[All Fields]

behaviors: ”behavior”[MeSH Terms] OR ‘behavior’[All Fields] OR ‘behavioral’[All Fields] OR ‘behavioural’[All Fields] OR ‘behavior’s’[All Fields] OR ‘behaviorally’[All Fields] OR ‘behaviour’[All Fields] OR ‘behaviourally’[All Fields] OR ‘behaviours’[All Fields] OR ‘behaviors’[All Fields] OR ‘pattern’[All Fields] OR ‘pattern’s’[All Fields] OR ‘patternability’[All Fields] OR ‘patternable’[All Fields] OR ‘patterned’[All Fields] OR ‘patterning’[All Fields] OR ‘patternings’[All Fields] OR ‘patterns’[All Fields]

professional: ”professional”[All Fields] OR ‘professional’s’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalism’[MeSH Terms] OR ‘professionalism’[All Fields] OR ‘professionality’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalization’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalize’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalized’[All Fields] OR ‘professionalizing’[All Fields] OR ‘professionally’[All Fields] OR ‘professionals’[All Fields]

identity: ”identities”[All Fields] OR ‘identity’[All Fields]

SNS: ”SNS”[MeSH Terms] OR (‘social’[All Fields] AND ‘media’[All Fields]) OR ‘SNS’[All Fields]

Twitter: ”twitter”[All Fields] OR ‘twitter’s’[All Fields] OR ‘twitters’[All Fields]

facebook: ”facebook”[All Fields] OR ‘facebook’s’[All Fields]

healthcare professionals: ”health personnel”[MeSH Terms] OR (‘health’[All Fields] AND ‘personnel’[All Fields]) OR ‘health personnel’[All Fields] OR (‘health’[All Fields] AND ‘professionals’[All Fields]) OR ‘healthcare professionals’[All Fields]

ProQuest 13 May 2020 (n = 1348)

Databases:

Ebook Central

Health Research Premium Collection

ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global

Narrowed by:

Entered date: 2015–05-13 – 2020-05-13;Subject: higher education; nursing; health education; medicine; students; medical personnel; health care; pedagogy; professionals; nurses; behavioral psychology; health sciences; hospitals; questionnaires; medical research; instructional design; medical education; attitudes; medical ethics;Language: English

ISI Web of Science (n = 50)

Science direct/Scopus (n = 1230)

Medical professionalism AND SNS

EBSCO host (2015-2020) 13 May 2020 (n = 39)

Professionalism AND SNS AND Healthcare professionals

Appendix 2 . Social Networking Sites in Medical Education (SNSME)

Age (in years)

Country of residence:

Is country of residence same as nationality: Yes No

(If no, please specify) -

Gender Male Female Prefer not to disclose

Year in MBBS course FY 1 2 3 4 5 6

29. Please write any other ideas and opinions about e-professionalism in SNS that you consider to be important.

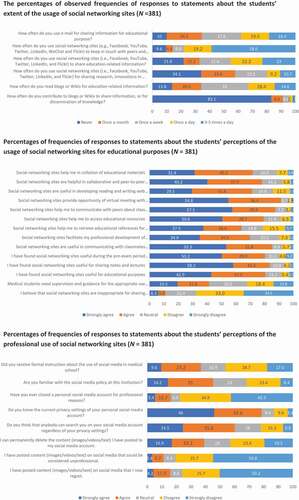

Appendix 3. Pictorial presentations of SNSME Results

The percentages of observed frequencies of responses to statements about the students’ extent of the usage of social networking sites (N = 381)

Percentages of frequencies of responses to statements about the students’ perceptions of the usage of social networking sites for educational purposes (N = 381)

Percentages of frequencies of responses to statements about the students’ perceptions of the professional use of social networking sites (N = 381)

Appendix 4. Tabular presentations of SNSME Results

The percentages of observed frequencies of responses to statements about the students’ extent of the usage of social networking sites (N = 381)

Percentages of frequencies of responses to statements about the students’ perceptions of the usage of social networking sites for educational purposes (N = 381)

Percentages of frequencies of responses to statements about the students’ perceptions of the professional use of social networking sites (N = 381)

The results of the Mann-Whitney U test showing the comparison of the students’ perceptions about the usage of social networking sites among gender (N = 381)

The results of the Kruskal Wallis test showing the comparison of the students’ perceptions about the usage of social networking sites across age groups (N = 381)

The results of the Kruskal Wallis test showing the comparison of the students’ perceptions about the usage of social networking sites for educational purposes across years of schooling (N = 381)