Abstract

The aim of this research is to test the role of corporate image in predicting credibility, trust, and brand recognition. In addition, it is intended to verify whether these variables can explain the attitudes and future intentions of fitness centre users to better understand their behaviour. Through an online survey, the opinions of 325 fitness centre users were collected regarding the previously mentioned variables. A structural equation model was made by means of EQS 6.4 to confirm, first, the reliability of the scales used and subsequently test the different relationships between variables. The results show the importance of corporate image as a starting point to explain future intentions. Between 78% and 91% of the variance of credibility, trust, and recognition and, consequently, up to 90% of attitudes and 62% of future intentions can be explained by the equation. Thus, managers should not only focus on the variables related to the experience or performance of the service but also attend to brand variables. This research represents a contribution to the literature on brand perception and its relationship with consumer behaviour in fitness centres, an uncommon topic in this context.

1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in the offerings of fitness centres attending to different segments of the population. According to the European Health & Fitness Market Report (Deloitte, Citation2020), there are 63,644 centres with a total of 64.8 million members, which means a growth of 3.8% and a total revenue of 28.2 billion euros, demonstrating that fitness centres are important within the sports sector. Parallel to this growth, there has also been an increase in the literature related to sports management in these fitness centres, with the intention of better understanding their peculiarities and analysing possible improvements in such management. Therefore, the sport management literature has analysed aspects such as perceived quality, perceived value, satisfaction, and future intentions (e.g., Baena-Arroyo et al., Citation2020; Biscaia et al., Citation2021; García-Pascual et al., Citation2020; Newland & Yoo, Citation2021; Yu et al., Citation2014).

Marketing has a lot to contribute to the improvement of sports services management, in the same way that it has been helpful in other contexts, providing useful information to managers to establish strategies in a more appropriate way. It is known that marketing is a fundamental element for understanding consumer behaviour (De Mooij, Citation2019) and that the analysis of brand image has had great impact (Balmer et al., Citation2020; Iglesias et al., Citation2019; Lin et al., Citation2021). Although there are some related studies in the field of professional sport, sport sponsorship and esports (e.g., Alonso-Dos-Santos et al., Citation2018; Amor et al., Citation2020; Grohs, Citation2016), the literature analysing this construct in sports services is very scarce, even more so if we focus on fitness centres. Therefore, the research problem we aim to address is the lack of literature on the benefits and consequences of working corporate image to improve future intentions in fitness centres.

This lack of information forces sport managers to decide based on the information of different contexts, which can make those decisions inadequate; therefore, we want to use specific data on the fitness sector and its peculiarities to make more effective decisions. This research would help sport managers to better understand their context and the importance of working on the brand because the brand has proven to be an important aspect to understanding consumer behaviour (Chopra et al., Citation2021; Kunkel & Biscaia, Citation2020). Therefore, this research is novel because it addresses a non-common methodological approach in the sporting context—brand perception and the growing sector of fitness centres—a research topic that is attracting increasing attention from researchers and sport managers.

2. Theoretical background and hypotheses

2.1. Corporate image and Brand image

Corporate image has attracted the attention of researchers over time and continues to referenced in the study of brands (Balmer et al., Citation2020; Da Silva & Alwi, Citation2008; Dennis et al., Citation2007; Greyser & Urde, Citation2019). Corporate image includes the analysis of different factors (Bravo et al., Citation2010), and it is related to the physical and behavioural attributes of the brand, such as business name, products/services offered, tradition, and the quality communicated through each person interacting with the brand’s clients (Nguyen & Leblanc, Citation2001). At a conceptual level, corporate image is understood as a sum of the impressions and expectations that consumers and nonconsumers have about the brand (Howcroft, Citation1991) and as an image that the public has about an organization created thanks to the accumulation of all the information received (Fombrun, Citation1997). According to other definitions, corporate image is the mental picture of a company that appears from the moment someone sees the logo or hears about it (Gray & Balmer, Citation1998). This is why it is so important to develop and manage corporate image properly from the moment the brand is born.

In that sense, the closely related concepts of brand identity, corporate image and brand image can cause confusion (Martínez-Cevallos et al., Citation2020). Identity has to do with how a brand wants to be perceived and is related to the mission, vision and values of the organization (Ruzzier & De Chernatony, Citation2013). On the other hand, corporate image relates to the general impression of consumers about a company (Barich & Kotler, Citation1991) oriented to a wide range of stakeholders (Chang et al., Citation2015) considering corporate aspects such as ethics (Souiden et al., Citation2006) or corporate social responsibility (Ali et al., Citation2020; Kraus et al., Citation2021). Finally, brand image refers to the set of meanings that consumers have about a brand (Dowling, Citation1986), in this case of those brands through which companies advertise and sell their products (Capriotti, Citation1999). This brand image, in contrast to corporate image, will be primarily targeted at current and potential consumers (Martínez-Cevallos et al., Citation2020).

2.2. Credibility, trust and recognition

When addressing credibility, we understand the concept to mean the promises an entity makes and how those promises are or are not subsequently fulfilled (Herbig & Milewicz, Citation1995). Other authors link it to the credibility of the product's information contained in a brand (Erdem & Swait, Citation2004). Moreover, credibility does not correspond to a specific moment; it addresses the cumulative effects of marketing activities carried out over time, influencing psychological processes and transferring an objective quality into a subjective one (Erdem et al., Citation2002). Therefore, if the brand ever fails to ensure the quality of its product, consumers credibility towards it will be diminished (Lee & Kim, Citation2020). Furthermore, this concept is related to signal theory (Spence, Citation1974). This theory states that there is an agent that transmits information to a receiver, so if the signals it transmits are credible, they will be more effective and may influence the improvement of certain aspects such as brand usefulness (Spry et al., Citation2011). In marketing, brands become an essential element, especially in the service context, since there is a high level of asymmetric information (Mahadevan et al., Citation2017; Spence, Citation1974; Zhang & Xu, Citation2021). In addition, there are situations where information on the service may be incomplete so that brands and their credibility will serve to determine the success of the company (An et al., Citation2018) and contribute to changing the beliefs, attitudes and behaviour of users (Abu Zayyad et al., Citation2021; Wang & Scheinbaum, Citation2018).

Trust, on the other hand, is related to the feeling of security that consumers have when interacting with a brand (Delgado-Ballester et al., Citation2003). This concept is also related to the hope that if a problem arises, the brand will do everything possible to solve it (Kim et al., Citation2018). Brand trust is another element that determines the relationship that a brand can have with a consumer, since, as Sobel's theory (1985) established, consumers must decide whether to grant credibility and whether to trust the other part with which they interact. In this sense, generating trust reduces the uncertainty of the commercial relationship (Frasquet et al., Citation2017). Therefore, it is clear that brand trust has an important influence on the relationship established in the purchasing process (Cuong, Citation2020; Kim & Walker, Citation2013; Sanny et al., Citation2020).

Brand recognition is related to the extent to which the user is able to recognize the brand, being an influential element in the attitudes he or she develops towards it (van Grinsven & Das, Citation2016). Other authors define recognition as the quickness with which a consumer recognizes a brand, discriminating it through visible elements, such as the logo (Keller, Citation1993; Machado et al., Citation2021). In this regard, consumers mainly choose things that are familiar to them (Coates et al., Citation2006). This is in line with the idea of heuristic recognition proposed by Goldstein and Gigerenzer (Citation2002), which states that when we do not know the right answer in a situation, we tend to choose those things that we recognize.

Therefore, if brands try to increase their exposure, they will achieve higher levels of recognition and will be able to generate more positive attitudes towards the brand. This is especially for complex logos, since these relationships would mean short-term benefits for visually simple brands and long-term benefits for complex logos (van Grinsven & Das, Citation2016). In this sense, Pieters et al. (Citation2010) establish that the complexity of a brand's advertising is an aspect that favours attracting the attention of users and creating favourable attitudes towards such advertising. Finally, to increase brand exposure, different strategies can be followed in the sports context including event or athlete sponsorship actions as well as collaborations with influencers or celebrities through social media.

From a corporate point of view, credibility is related to consumers' perception of the company and its ability to implement the necessary management activities (Kim et al., Citation2014). In addition, credibility is also related to the promises made by the company (Herbig & Milewicz, Citation1995) and its trustworthiness and expertise to carry them out (Erdem & Swait, Citation2004). Therefore, the extent to which the entity meets these requirements make its corporate image more credible to consumers, which leads us to propose H1.

In the same way, corporate image has been shown to be an important element since the image of the entity affects the behaviour of stakeholders (Yu et al., Citation2021), including consumers, which is why companies strive to develop and properly manage their image (Upamannyu et al., Citation2015). This relationship also exists between corporate image and trust (Flavián et al., Citation2005; Purwanto et al., Citation2020) since consumers feel trust and like more brands when they perceive the company as a more desirable organization (Moon, Citation2007). This leads us to propose H2. On the other hand, the relationship between credibility and trust and its importance for the establishment of commercial relations between brands and consumers has also been discussed (Lou & Yuan, Citation2019). If consumers perceive a brand as more credible, they have higher levels of trust (Alguacil et al., Citation2020; Ngo et al., Citation2020) and that trust leads to better expectations of the brand's intentions (Pauwels-Delassus & Descotes, Citation2013; Rather et al., Citation2019). This leads us to propose H3. Finally, corporate image is linked to consumer recognition; for instance, the communication of ethical aspects to consumers at a corporate level leads to recognition benefits (Iglesias et al., Citation2019). In the same way that visual aspects are used, corporate logos trigger positive emotions and improve brand recognition (Foroudi et al., Citation2014; Müller et al., Citation2013; van der Lans et al., Citation2009). This leads us to propose H4.

For these reasons, here we propose H1, H2, H3, and H4:

H1. Corporate image is significantly related to credibility.

H2. Corporate image is significantly related to trust.

H3. Credibility is significantly related to brand trust.

H4. Corporate image is significantly related to brand recognition.

2.3. Attitudes towards the Brand and future intentions

Attitudes refer to a state of mind of disposition, which is organized through experience and influences the response of individuals in the situations in which they find themselves (Allport, Citation1935). Other authors with more marketing-oriented definitions, Eagly and Chaiken (Citation2007), stated that attitudes are related to the disposition that consumers have towards a brand; it is the psychological tendency that is expressed when evaluating a particular entity with a certain degree of agreement or disagreement. Interest in knowing attitudes has led to the emergence of different theories and models that attempt to explain the consumer information processes influencing their decisions (Arnould et al., Citation2002; Copeland & Zhao, Citation2020; Nimri et al., Citation2020; Xiao, Citation2020). Within these models and theories, we find, for instance, the theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behaviour, or the tri-component model of attitudes (Makanyeza, Citation2014). According to this last model, which has been used to understand consumer behaviour (Asiegbu et al., Citation2012; Pangriya & Kumar, Citation2018), consumer behaviour is formed by three components: affect (feelings/emotions), cognition (thinkings/beliefs), and conative (behaviour).

In these components, we can work from brand management to generate perceptions, emotions, or feelings towards it and establish beliefs to obtain the desired behaviour through it. These concepts interact and cause a greater or lesser extent of cognitive dissonance during the purchasing process. As explained by Festinger's theory of cognitive dissonance (1957), any dissonance that makes the consumer uncomfortable will lead them to try to eliminate that dissonance. Usually, it is understood that the way to eliminate this dissonance is not only by buying the product but also by the convincing the consumer, through other aspects or perceived benefits of the brand, that he or she truly needs the product, which also makes the dissonance disappear and allows more space for managers to try to trigger these mechanisms.

In the case of brands, through advertising, attempts are made to transmit their characteristics and benefits, and the users are the ones who evaluate it and begin to create positive or negative attitudes towards the brand (Low & Lamb, Citation2000). These attitudes are also related to other important aspects at a business level, such as ethics and corporate social responsibility (Ferrell et al., Citation2019; Vizcaíno et al., Citation2021). In relation to the hypothesis, if a brand is more credible, attitudes are improved (Chin et al., Citation2020; Nayeem et al., Citation2019). In the same way, greater trust will improve those attitudes (Kim et al., Citation2019). Finally, as mentioned, brand recognition leads to improved attitudes towards the brand (Norman et al., Citation2020). All this leads us to propose H5, H6, and H7.

H5. Credibility is significantly related to attitudes.

H6. Brand trust is significantly related to attitudes.

H7. Brand recognition is significantly related to attitudes.

Finally, in support of H8, that attitudes favour future intentions, as previously mentioned, users evaluate brands, and accordingly they generate positive or negative attitudes that are never neutral (Ratneshwar & Shocker, Citation1991). Obviously, when we talk about brands and specifically about services, trying out the service is an element that can either reinforce positive attitudes or negative attitudes. In any case, whether positive or negative, attitudes have an effect on purchase intentions (Shah et al., Citation2012) since they are responsible for mediating the effect of perceptions on brand advertising and purchase intentions (Sarkar et al., Citation2019) on the basis of the general perception of the brand (Ko et al., Citation2008). From these premises, we propose H8:

H8. Attitudes are significantly related to future intentions.

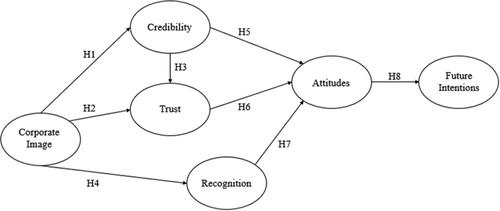

For all the abovementioned reasons, this research aims to verify how, from corporate image perceptions of a fitness centre, brand image perceptions of its users can be improved, specifically in terms of perceived credibility, trust, and recognition. Consequently, it is intended to test whether this has an impact on their attitudes and future intentions (see ). With this proposal, we contribute scientific literature analysing corporate image, brand image, and fitness centre users' behaviour. This provides specific information on this context to managers so that they can perform better management.

3. Methods

3.1. Instrument

The instrument used was an online questionnaire developed from validated scales extracted from the literature. shows the detailed items as well as the mean values and standard deviations obtained from their opinions. First, the corporate image scale was extracted from Balmer et al. (Citation2006) and is made up of five items, while the credibility scale (three items) was adapted from Sweeney and Swait (Citation2008). On the other hand, the trust scale is composed of three items extracted from the contribution of Hur et al. (Citation2014), and the brand recognition scale is based on the proposal of Tong and Hawley (Citation2009) with three statements. Finally, the attitude scale is composed of four items (Besharat, Citation2010; Gwinner & Bennett, Citation2008) and the future intentions scale contains four items and is based on the contribution of Zeithaml et al. (Citation1996).

Table 1. Items and descriptive values.

As shown in the results section, all the scales that make up the instrument show adequate psychometric properties, with composite reliability (CR) values above .70 (Hair et al., Citation2006), Cronbach's alpha values above .70 (Hair et al., Citation2006), and average variance extracted (AVE) values above .50 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Regarding discriminant validity, the Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) criterion that indicates that the correlations between pairs should not exceed the value of the square root of AVE is met, but not strictly in two cases. In this sense, recognized authors such as Folger (Citation1989) recommend not treating the AVE-SV outcome as binary but rather that validity should be studied in combination with other indicators. So, given that the cut-off levels are minimally exceeded in these cases and the rest of the indicators are adequate, discriminant validity is considered to be adequate ().

Table 2. Discriminant validity indicators.

3.2. Procedure

First, the questionnaire through which the data would be collected was elaborated. This questionnaire was made up of validated scales, as previously mentioned in the instrument section. Once the questionnaire was created, was reviewed by research and marketing experts, and subsequently the items were transferred to an online platform, through which the survey could be sent to the users of the fitness centre, always in coordination and with the permission and transfer of the data from the director of that centre. To collect the data, the respondents were properly informed, clarifying that their participation was voluntary and anonymous, and their answers were only used for academic purposes. The survey was available for completion for two weeks, and at the end of this time, thanks to the online survey all the data was automatically transferred to the SPSS statistical program for subsequent analysis.

3.3. Sample

The target population of this research corresponds to users of fitness centres. Specifically, the sample of participants is composed of 325 users of a fitness centre located in Seville. The convenience sample was collected from a total target population of 3000 users, and information was collected through an online questionnaire sent by e-mail. Of the 325 participants,147 were men (45.2%), and 178 were women (54.8%). In terms of their sociodemographic characteristics, 5.2% (n = 17) were under 20 years old, 36% (n = 117) between 21 and 30, 20.9% (n = 68) between 31 and 40, 19.4% (n = 63) between 41 and 50, 13.2% (n = 43) between 51 and 60, and 5.2% (n = 17) over 60 years old. On the other hand, in relation to the frequency of attendance, 1.8% (n = 6) of the total respondents reported attending less than once a week, 3.1% (n = 10) once a week, 19.4% (n = 63) twice a week, 42.5% (n = 138) 3 times a week, and 33.2% (n = 108) more than 4 times a week.

In terms of the time they have been registered at the centre, 17.5% (n = 57) reported that they have been there less than 3 months, 18.8% (n = 61) between 3 and 6 months, 8.9% (n = 29) between 6 and 12 months, 14.8% (n = 48) between 1 and 2 years, and 40% (n = 130) for over 2 years. Finally, as to whether they had previously been enrolled at another centre,29.8% (n = 97) reported that they had not been registered in another centre before belonging to the fitness centre analysed, 8.6% (n = 28) reported that they had been registered in that same centre, while 61.5% (n = 200) reported that they had been registered in a different centre before being enrolling in the fitness centre where the study was conducted.

3.4. Statistical analysis

To carry out the statistical analysis, first, using SPSS software (Statistical package, version 25, IBM corporation, NY, USA) a frequency and percentage analysis was carried out to determine the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. Later, already centred in the structural model by means of EQS 6.4 software, a confirmatory factorial analysis was carried out applying robust maximum likelihood estimation (MLR) since it enables correction of the possible absence of normality in our data, considering Satorra-Bentler's chi-square statistic (Chou et al., Citation1991). This allows us to verify, on the one hand, that the proposed measurement model obtained an appropriate model fit within the parameters indicated by the literature.

On the other hand, the scales that conform the model fulfilled the reliability criteria that assure their suitability for the measurement of the proposed constructs. Finally, with the EQS 6.4 software, an analysis of the structural model was carried out to check whether the model complied with the necessary model fit indicated by the literature. Additionally, we checked whether the proposed relationships were significant and, if so, to what extent and their capacity to predict the different variables of interest.

4. Results

4.1. Measurement model and scale reliability

First, a confirmatory factor analysis was carried out to check that the proposed measurement model had a good fit (S-Bχ2 = 360.97; χ2 = 522.82; df = 194; χ2/df = 2.69; NFI = .95; NNFI = .97; CFI = .98; IFI = .98; RMSEA = .05). In this sense, the value of the χ2/df ratio is below 3 (Byrne, Citation2013), the fit indexes are above the threshold of .90 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999) and the error is below the criterion of .08 (Browne & Cudeck, Browne & Cudeck, Citation1993). The reliability values of the scales used (see ) all met the reliability criteria, with Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability values above .70 (Hair et al., Citation2006), factorial weights of the items above .60 (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1988), and AVE values above .50 (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981).

Table 3. Scale reliability.

4.2. Structural model

Once the reliability and suitability of the structural model were confirmed, the analysis of the structural equation model was carried out. This analysis is composed of six factors—corporate image, credibility, trust, recognition, attitudes, and future intentions—and the eight relationships between them that correspond to hypotheses. The results of the analysis indicate that the structural model has an adequate fit (S-Bχ2 = 389.73; χ2 = 562.56; df = 201; χ2/df = 2.80; NFI = .95; NNFI = .97; CFI=.97; IFI = .97; RMSEA = .05), again meeting the criteria outlined above (Browne & Cudeck, Citation1993; Byrne, Citation2013; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999).

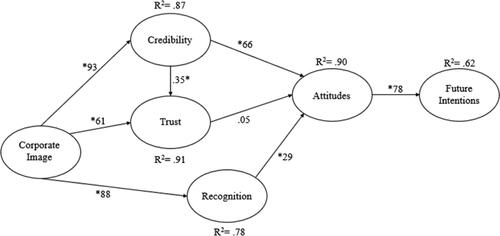

For the results of the proposed relationships (see ), all of them were significant, with the exception of the relationship that links trust with attitudes. More specifically, corporate image is significantly related to credibility, trust, and recognition (β =. 93; p < .05; β = .61; p<.05, and β = .88; p < .05, respectively) and credibility with trust (β = .35; p<.05). On the other hand, credibility and recognition are significantly associated with attitudes (β=.66; p<.05; and β=.29; p<.05, respectively), while they are not the same in the case of trust (β=.05; p>.05).

Finally, we confirm the significant relationship between attitudes and future intentions (β=.78; p<.05). Considering the explanatory capacity of the model, from the corporate image, up to 87% of the credibility and 78% of the brand recognition can be explained at a theoretical level, while from the corporate image and credibility, up to 91% of the brand trust can be explained. On the other hand, credibility and recognition significantly influence attitudes towards the brand and how these attitudes significantly predict the future intentions of users, with explanatory percentages of 90% and 62%, respectively.

Finally, to conclude with the results obtained, shows the summary of the 8 hypotheses raised in the study that were tested by creating the structural equation model.

Table 4. Summary of the hypotheses.

5. Discussion

Brand image and corporate image has been widely studied in the field of marketing in different aspects throughout the literature (Gray & Balmer, Citation1998; Iglesias et al., Citation2019; Nguyen & Leblanc, Citation2001; Ramesh et al., Citation2019). More specifically, there are also examples in the sports context (Ko et al., Citation2008; Martínez-Cevallos et al., Citation2020; Pope & Voges, Citation2000); however, the study of brands in the sports context has less input, and is an emerging topic.

In relation to the present study, it has been confirmed that corporate image has an effect on credibility, trust, and recognition. This is in line with other studies, such as Flavián et al. (Citation2005). Therefore, sports or marketing managers must develop and manage their brand very carefully from the beginning; otherwise, they may create perceptions that work against them. In the same way, credibility has been shown to influence the trust generated by users. This relationship has been studied in the literature (Lou & Yuan, Citation2019), indicating that credibility decreases perceived risk, an aspect that, by reducing uncertainty, lessens the importance of trust (Moorman et al., Citation1992). Therefore, one must fulfil what is promised and have a good disposition to try to carry it out, since it has been demonstrated that the willingness to accomplish what has been promised is more important than the real capacity to achieve it (Erdem & Swait, Citation2004).

On the other hand, we see that credibility influences attitudes towards the brand, as is the case in other studies (Chin et al., Citation2020). It is logical to think if we perceive an organization as credible, it is more likely that there will be a favourable disposition towards it. However, trust has not shown any influence on attitudes. This absence of influence contradicts the findings in contributions such as Chaudhuri and Holbrook (Citation2001), in which they confirm the relationship of trust with improved attitudinal loyalty. Perhaps the fact that credibility and trust, which are related variables, are part of the same prediction influences the weight of the relationship contributed by each variable, it would be interesting to analyse these possible influences. Finally, we see that brand recognition favours attitudes, which was expected from marketing publications that discuss the influence and moderating role of recognition on such attitudes (Evans et al., Citation2017; van Grinsven & Das, Citation2016). The same happens with the attitudes that the users of the fitness centre have towards the brand, since they explain to a great extent their future intentions, a relationship that has been widely studied in the context of sports services marketing (Ahn & Back, Citation2018; Alguacil et al., Citation2020) but not often in the specific case of fitness centres.

6. Implications, limitations, and future lines of research

The results and conclusions drawn from this study have different implications. On a theoretical level, the findings contribute to our understanding of fitness centres, providing new information on how the variables relate to each other and what influence they have on others to improve the future intentions of consumers. This serves to help to lay the foundations and to progressively learn more about this topic, while attending to its peculiarities and not following the guidelines for general marketing studies or those in other contexts. On a practical level, the contribution helps to gather new specific information about this context for the managers of fitness centres in relation to the work of their brand. This new information will help them understand how the relationships of these variables function in the context of fitness centres to better orient their strategies. In addition, it allows us to verify the importance of working on the corporate image of the service, showing managers that this is a key aspect to which they need to pay more attention to improve business performance. Moreover, with this type of research, we contribute to the increasing knowledge of the behaviour of the sports consumer in fitness centres. Therefore, this study also benefits users, who may receive a service more in line with their needs and interests.

Regarding the limitations of the study, analysing only one centre makes the results difficult to generalize. However, this type of study is an initial step towards contributing to the analysis of brand image in fitness centres, which is vastly understudied. In the same way, carrying out a study on future intentions in which there is no subsequent follow-up enables assessing participants’ intentions but not whether they have been expressed in a concrete behaviour. Finally, it would be important to establish a sample balance to ensure that all target groups have a representative sample and that this is not random. In future studies, it would be interesting not only to include more centres but also to differentiate by typologies and price positioning (low-cost, premium) and even examine perceptions of the users of each centre according to the frequency and type of use or activities within the service. Considering these aspects, we will be able to better understand how brand variables develop and interact according to the different types of centres and user profiles. Furthermore, it would be interesting to carry out studies on future intentions of consumers with a subsequent follow-up to determine whether the intentions resulted in specific actions; this would also allow us to understand the relationship between intentions and final behaviours.

7. Conclusions

The results confirm the importance of corporate image to trigger brand trust and brand recognition through credibility and its significant influence on the attitudes and future intentions of users. This highlights a new approach that differs from that currently conceived in sports centres, confirming that not only service experience and tangible features influence consumer behaviour. This contribution demonstrates that based on brand perceptions, which are modifiable using the appropriate strategies, we can improve variables to help increase the future intentions of fitness centre users. Therefore, the work of the brand must be considered carefully by sports managers, starting from a clear identity, to communicate a desirable corporate image. This, together with the rest of the tools, will allow us to carry out appropriate strategies to improve those variables that are key for the success and sustainability of any company.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abu Zayyad, H. M., Obeidat, Z. M., Alshurideh, M. T., Abuhashesh, M., Maqableh, M., & Masa’deh, R. E. (2021). Corporate social responsibility and patronage intentions: The mediating effect of brand credibility. Journal of Marketing Communications, 27(5), 510–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2020.1728565

- Ahn, J., & Back, K. J. (2018). Influence of brand relationship on customer attitude toward integrated resort brands: A cognitive, affective, and conative perspective. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(4), 449–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2017.1358239

- Alguacil, M., Sánchez-García, J., & Valantine, I. (2020). Be congruent and I will be loyal: The case of sport services. Sport in Society, 23(2), 234–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1607305

- Ali, H. Y., Danish, R. Q., & Asrar‐Ul‐Haq, M. (2020). How corporate social responsibility boosts firm financial performance: The mediating role of corporate image and customer satisfaction. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(1), 166–177. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1781

- Allport, G. W. (1935). Attitudes. In C. Murchison (Ed.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 798–844). Clark University Press.

- Alonso-Dos-Santos, M., Rejón-Guardia, F., Pérez-Campos, C., Calabuig, F., & Ko, Y. J. (2018). Engagement in sports virtual brand communities. Journal of Business Research, 89, 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.053

- Amor, J. S. C., Pérez-Campos, C., & Molina-García, N. (2020). Brand image in esports events. Difference between players and non-players. Journal of Sports Economics & Management, 10(2), 102–113.

- An, J., Do, D. K. X., Ngo, L. V., & Quan, T. H. M. (2019). Turning brand credibility into positive word-of-mouth: Integrating the signaling and social identity perspectives. Journal of Brand Management, 26(2), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-018-0118-0

- Arnould, E. J., Price, L., & Zinkhan, G. M. (2002). Consumers. McGraw-Hill.

- Asiegbu, I. F., Powei, D. M., & Iruka, C. H. (2012). Consumer attitude: Some reflections on its concept, trilogy, relationship with consumer behaviour, and marketing implications. European Journal of Business and Management, 4(13), 38–50.

- Baena-Arroyo, M. J., García-Fernández, J., Gálvez-Ruiz, P., & Grimaldi-Puyana, M. (2020). Analyzing consumer loyalty through service experience and service convenience: Differences between instructor fitness classes and virtual fitness classes. Sustainability, 12(3), 828. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12030828

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02723327

- Balmer, J. M., Lin, Z., Chen, W., & He, X. (2020). The role of corporate brand image for B2B relationships of logistics service providers in China. Journal of Business Research, 117, 850–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.03.043

- Balmer, J. M., Mukherjee, A., Greyser, S. A., Jenster, P., Souiden, N., Kassim, N. M., & Hong, H. J. (2006). The effect of corporate branding dimensions on consumers' product evaluation. European Journal of Marketing, 40(7–8), 825–845.

- Barich, H., & Kotler, P. (1991). A framework for marketing image management. MIT Sloan Management Review, 32(2), 94.

- Besharat, A. (2010). How co-branding versus brand extensions drive consumers' evaluations of new products: A brand equity approach. Industrial Marketing Management, 39(8), 1240–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2010.02.021

- Biscaia, R., Yoshida, M., & Kim, Y. (2021). Service quality and its effects on consumer outcomes: A meta-analytic review in spectator sport. European Sport Management Quarterly, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2021.1938630

- Bravo, R., Montaner, T., & Pina, J. M. (2010). Corporate brand image in retail banking: Development and validation of a scale. The Service Industries Journal, 30(8), 1199–1218. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642060802311260

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Tesing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Sage.

- Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge.

- Capriotti, P. (1999). Strategic planning of corporate image. IIRP.

- Chang, A., Chiang, H. H., & Han, T. S. (2015). Investigating the dual-route effects of corporate branding on brand equity. Asia Pacific Management Review, 20(3), 120–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmrv.2014.10.001

- Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.65.2.81.18255

- Chin, P. N., Isa, S. M., & Alodin, Y. (2020). The impact of endorser and brand credibility on consumers’ purchase intention: The mediating effect of attitude towards brand and brand credibility. Journal of Marketing Communications, 26(8), 896–912. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2019.1604561

- Chopra, A., Avhad, V., & Jaju, A. S. (2021). Influencer marketing: An exploratory study to identify antecedents of consumer behavior of millennial. Business Perspectives and Research, 9(1), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/2278533720923486

- Chou, C. P., Bentler, P. M., & Satorra, A. (1991). Scaled test statistics and robust standard errors for non‐normal data in covariance structure analysis: A Monte Carlo study. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 44(2), 347–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1991.tb00966.x

- Coates, S. L., Butler, L. T., & Berry, D. C. (2006). Implicit memory and consumer choice: The mediating role of brand familiarity. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 20(8), 1101–1116. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1262

- Copeland, L. R., & Zhao, L. (2020). Instagram and theory of reasoned action: US consumers influence of peers online and purchase intention. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 13(3), 265–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/17543266.2020.1783374

- Cuong, D. T. (2020). The role of brand trust as a mediator in the relationship between brand satisfaction and purchase intention. International Journal of Psychosocial Rehabilitation, 24(6), 14726–14735.

- Da Silva, R. V., & Alwi, S. F. S. (2008). Online corporate brand image, satisfaction and loyalty. Journal of Brand Management, 16(3), 119–144. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550137

- De Mooij, M. (2019). Consumer behaviour and culture: Consequences for global marketing and advertising., SAGE Publications.

- Delgado-Ballester, E., Munuera-Alemán, J. L., & Yagüe-Guillen, M. J. (2003). Development and validation of a brand trust scale. International Journal of Market Research, 45(1), 35–54.

- Deloitte. (2020). European health & fitness market report. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/de/Documents/consumer-business/European-Health-and-Fitness-Market-2020-Reportauszug.pdf

- Dennis, C., King, T., & Martenson, R. (2007). Corporate brand image, satisfaction and store loyalty. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 35(7), 544–555.

- Dowling, G. R. (1986). Managing your corporate images. Industrial Marketing Management, 15(2), 109–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/0019-8501(86)90051-9

- Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (2007). The advantages of an inclusive definition of attitude. Social Cognition, 25(5), 582–602. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2007.25.5.582

- Erdem, T., & Swait, J. (2004). Brand Credibility, brand consideration, and choice. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1086/383434

- Erdem, T., Swait, J., & Louviere, J. (2002). The impact of brand credibility on consumer price sensitivity. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 19(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8116(01)00048-9

- Evans, N. J., Phua, J., Lim, J., & Jun, H. (2017). Disclosing Instagram influencer advertising: The effects of disclosure language on advertising recognition, attitudes, and behavioral intent. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 17(2), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2017.1366885

- Ferrell, O. C., Harrison, D. E., Ferrell, L., & Hair, J. F. (2019). Business ethics, corporate social responsibility, and brand attitudes: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Research, 95, 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.039

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

- Flavián, C., Guinaliu, M., & Torres, E. (2005). The influence of corporate image on consumer trust. Internet Research, 15(4), 447–470. https://doi.org/10.1108/10662240510615191

- Folger, R. (1989). Significance tests and the duplicity of binary decisions. Psychological Bulletin, 106(1), 155–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.106.1.155

- Fombrun, C. (1997). Reputation. Realizing value from corporate image. Harvard Business School Press.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Foroudi, P., Melewar, T. C., & Gupta, S. (2014). Linking corporate logo, corporate image, and reputation: An examination of consumer perceptions in the financial setting. Journal of Business Research, 67(11), 2269–2281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.06.015

- Frasquet, M., Mollá-Descals, A., & Ruiz-Molina, M. E. (2017). Understanding loyalty in multichannel retailing: The role of brand trust and brand attachment. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 45(6), 608–625. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-07-2016-0118

- García-Pascual, F., Prado-Gascó, V., Alguacil, M., Valantine, I., & Calabuig, F. (2020). Future intentions of fitness center customers: Effect of emotions, perceived well-being and management variables. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2425. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.547846

- Goldstein, D. G., & Gigerenzer, G. (2002). Models of ecological rationality: The recognition heuristic. Psychological Review, 109(1), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.109.1.75

- Gray, E. R., & Balmer, J. M. (1998). Managing corporate image and corporate reputation. Long Range Planning, 31(5), 695–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0024-6301(98)00074-0

- Greyser, S. A., & Urde, M. (2019). What does your corporate brand stand for? Harvard Business Review, 1(2), 82–89.

- Grohs, R. (2016). Drivers of brand image improvement in sports-event sponsorship. International Journal of Advertising, 35(3), 391–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2015.1083070

- Gwinner, K., & Bennett, G. (2008). The impact of brand cohesiveness and sport identification on brand fit in a sponsorship context. Journal of Sport Management, 22(4), 410–426. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.22.4.410

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. (2006). Multivariate data analysis. Uppersaddle River.

- Herbig, P., & Milewicz, J. (1995). The relationship of reputation and credibility to brand success. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 12(4), 5–11.

- Howcroft, J. B. (1991). Customer satisfaction in retail banking. The Service Industries Journal, 11(1), 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069100000002

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Database] https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hur, W. M., Kim, M., & Kim, H. (2014). The role of brand trust in male customers' relationship to luxury brands. Psychological Reports, 114(2), 609–624.

- Iglesias, O., Markovic, S., Singh, J. J., & Sierra, V. (2019). Do customer perceptions of corporate services brand ethicality improve brand equity? Considering the roles of brand heritage, brand image, and recognition benefits. Journal of Business Ethics, 154(2), 441–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3455-0

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299305700101

- Kim, E. J., Kim, S. H., & Lee, Y. K. (2019). The effects of brand hearsay on brand trust and brand attitudes. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(7), 765–784. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2019.1567431

- Kim, S. S., Lee, J., & Prideaux, B. (2014). Effect of celebrity endorsement on tourists’ perception of corporate image, corporate credibility and corporate loyalty. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 37, 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.11.003

- Kim, M. S., Shin, D. J., & Koo, D. W. (2018). The influence of perceived service fairness on brand trust, brand experience and brand citizenship behaviour. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(7), 2603–2621. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-06-2017-0355

- Kim, M., & Walker, M. (2013). The influence of professional athlete philanthropy on donation intentions. European Sport Management Quarterly, 13(5), 579–601. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2013.837942

- Kim, M., Yin, X., & Lee, G. (2020). The effect of CSR on corporate image, customer citizenship behaviors, and customers’ long-term relationship orientation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88, 102520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102520

- Ko, Y. J., Kim, K., Claussen, C. L., & Kim, T. H. (2008). The effects of sport involvement, sponsor awareness and corporate image on intention to purchase sponsors' products. International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship, 9(2), 79–94.

- Kraus, S., Cane, M., & Ribeiro-Soriano, D. (2021). Does doing good do well? An investigation into the relationship between consumer buying behavior and CSR. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2021.1970605

- Kunkel, T., & Biscaia, R. (2020). Sport brands: Brand relationships and consumer behaviour. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 29(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.32731/SMQ.291.032020.01

- Lee, S., & Kim, E. (2020). Influencer marketing on Instagram: How sponsorship disclosure, influencer credibility, and brand credibility impact the effectiveness of Instagram promotional post. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 11(3), 232–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2020.1752766

- Lin, Y. H., Lin, F. J., & Wang, K. H. (2021). The effect of social mission on service quality and brand image. Journal of Business Research, 132, 744–752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.054

- Lou, C., & Yuan, S. (2019). Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 19(1), 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2018.1533501

- Low, G., & Lamb, C. (2000). The measurement and dimensionality of brand associations. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 9(6), 350–368. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420010356966

- Machado, J. C., Fonseca, B., & Martins, C. (2021). Brand logo and brand gender: Examining the effects of natural logo designs and color on brand gender perceptions and affect. Journal of Brand Management, 28(2), 152–170. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-020-00216-4

- Mahadevan, B., Hazra, J., & Jain, T. (2017). Services outsourcing under asymmetric cost information. European Journal of Operational Research, 257(2), 456–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2016.07.020

- Makanyeza, C. (2014). Measuring consumer attitude towards imported poultry meat products in a developing market: An assessment of reliability, validity and dimensionality of the tri-component attitude model. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(20), 874–881. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n20p874

- Martínez-Cevallos, D., Alguacil, M., & Calabuig, F. (2020). Influence of brand image of a sports event on the recommendation of its participants. Sustainability, 12(12), 5040. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125040

- Moon, J. (2007). Corporate image effects on consumers’ evaluation of brand trust and brand affect. Journal of Global Academy of Marketing Science, 17(3), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/12297119.2007.9707259

- Moorman, C., Zaltman, G., & Deshpande, R. (1992). Relationships between providers and users of market research: The dynamics of trust within and between organizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(3), 314–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379202900303

- Müller, B., Kocher, B., & Crettaz, A. (2013). The effects of visual rejuvenation through brand logos. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.026

- Nayeem, T., Murshed, F., & Dwivedi, A. (2019). Brand experience and brand attitude: Examining a credibility-based mechanism. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 37(7), 821–826. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-11-2018-0544

- Newland, B. L., & Yoo, J. J. E. (2021). Active sport event participants’ behavioural intentions: Leveraging outcomes for future attendance and visitation. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 27(1), 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766720948249

- Ngo, H. M., Liu, R., Moritaka, M., & Fukuda, S. (2020). Effects of industry-level factors, brand credibility and brand reputation on brand trust in safe food: Evidence from the safe vegetable sector in Vietnam. British Food Journal, 122(9), 2993–3007. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-03-2020-0167

- Nguyen, N., & Leblanc, G. (2001). Corporate image and corporate reputation in customers’ retention decisions in services. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 8(4), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-6989(00)00029-1

- Nimri, R., Patiar, A., & Jin, X. (2020). The determinants of consumers’ intention of purchasing green hotel accommodation: Extending the theory of planned behaviour. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 535–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.10.013

- Norman, J., Kelly, B., McMahon, A. T., Boyland, E., Chapman, K., & King, L. (2020). Remember Me? Exposure to unfamiliar food brands in television advertising and online advergames drives children’s brand recognition, attitudes, and desire to eat foods: A secondary analysis from a crossover experimental-control study with randomization at the group level. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 120(1), 120–129.

- Pangriya, R., & Kumar, M. R. (2018). A study of consumers' attitude towards online private label brands using the tri-component model. Indian Journal of Marketing, 48(5), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.17010/ijom/2018/v48/i5/123440

- Pauwels-Delassus, V., & Descotes, R. M. (2013). Brand name change: Can trust and loyalty be transferred? Journal of Brand Management, 20(8), 656–669. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2013.7

- Pieters, R., Wedel, M., & Batra, R. (2010). The stopping power of advertising: Measures and effects of visual complexity. Journal of Marketing, 74(5), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.74.5.048

- Pope, N. K., & Voges, K. E. (2000). The impact of sport sponsorship activities, corporate image, and prior use on consumer purchase intention. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 9(2), 96–102.

- Purwanto, E., Deviny, J., & Mutahar, A. M. (2020). The mediating role of trust in the relationship between corporate image, security, word of mouth and loyalty in m-banking using among the millennial generation in Indonesia. Management & Marketing. Challenges for the Knowledge Society, 15(2), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.2478/mmcks-2020-0016

- Ramesh, K., Saha, R., Goswami, S., & Dahiya, R. (2019). Consumer's response to CSR activities: Mediating role of brand image and brand attitude. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(2), 377–387.

- Rather, R. A., Tehseen, S., Itoo, M. H., & Parrey, S. H. (2019). Customer brand identification, affective commitment, customer satisfaction, and brand trust as antecedents of customer behavioral intention of loyalty: An empirical study in the hospitality sector. Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science, 29(2), 196–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/21639159.2019.1577694

- Ratneshwar, S., & Shocker, A. D. (1991). Substitution in use and the role of usage context in product category structures. Journal of Marketing Research, 28(3), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379102800303

- Ruzzier, M. K., & De Chernatony, L. (2013). Developing and applying a place brand identity model: The case of Slovenia. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.05.023

- Sanny, L., Arina, A., Maulidya, R., & Pertiwi, R. (2020). Purchase intention on Indonesia male’s skin care by social media marketing effect towards brand image and brand trust. Management Science Letters, 10(10), 2139–2146.

- Sarkar, J. G., Sarkar, A., & Yadav, R. (2019). Brand it green: Young consumers’ brand attitudes and purchase intentions toward green brand advertising appeals. Young Consumers, 20(3), 190–207. https://doi.org/10.1108/YC-08-2018-0840

- Shah, S. S. H., Aziz, J., Jaffari, A. R., Waris, S., Ejaz, W., Fatima, M., & Sherazi, S. K. (2012). The impact of brands on consumer purchase intentions. Asian Journal of Business Management, 4(2), 105–110.

- Sobel, J. (1985). A theory of credibility. The Review of Economic Studies, 52(4), 557–573. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297732

- Souiden, N., Kassim, N. M., & Hong, H. J. (2006). The effect of corporate branding dimensions on consumers' product evaluation: A cross‐cultural analysis. European Journal of Marketing, 40(7–8), 825–845. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560610670016

- Spence, M. (1974). Competitive and optimal responses to signals: An analysis of efficiency and distribution. Journal of Economic Theory, 7(3), 296–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0531(74)90098-2

- Spry, A., Pappu, R., & Cornwell, T. B. (2011). Celebrity endorsement, brand credibility and brand equity. European Journal of Marketing, 45(6), 882–909. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561111119958

- Sweeney, J., & Swait, J. (2008). The effects of brand credibility on customer loyalty. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 15(3), 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2007.04.001

- Tong, X., & Hawley, J. M. (2009). Measuring customer‐based brand equity: Empirical evidence from the sportswear market in China. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 18(4), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420910972783

- Upamannyu, N. K., Bhakar, S. S., & Gupta, M. (2015). Effect of corporate image on brand trust and brand affect. International Journal of Applied Science-Research and Review, 2(1), 20–33.

- van der Lans, R., Cote, J. A., Cole, C. A., Leong, S. M., Smidts, A., Henderson, P. W., Bluemelhuber, C., Bottomley, P. A., Doyle, J. R., Fedorikhin, A., Moorthy, J., Ramaseshan, B., & Schmitt, B. H. (2009). Cross-national logo evaluation analysis: An individual-level approach. Marketing Science, 28(5), 968–985. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1080.0462

- van Grinsven, B., & Das, E. (2016). Logo design in marketing communications: Brand logo complexity moderates exposure effects on brand recognition and brand attitude. Journal of Marketing Communications, 22(3), 256–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2013.866593

- Vizcaíno, F. V., Martin, S. L., Cardenas, J. J., & Cardenas, M. (2021). Employees’ attitudes toward corporate social responsibility programs: The influence of corporate frugality and polychronicity organizational capabilities. Journal of Business Research, 124, 538–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.11.016

- Wang, S. W., & Scheinbaum, A. C. (2018). Enhancing brand credibility via celebrity endorsement: Trustworthiness trumps attractiveness and expertise. Journal of Advertising Research, 58(1), 16–32. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR-2017-042

- Xiao, M. (2020). Factors influencing eSports viewership: An approach based on the theory of reasoned action. Communication & Sport, 8(1), 92–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479518819482

- Yu, W., Han, X., Ding, L., & He, M. (2021). Organic food corporate image and customer co-developing behavior: The mediating role of consumer trust and purchase intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 59, 102377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102377

- Yu, H. S., Zhang, J. J., Kim, D. H., Chen, K. K., Henderson, C., Min, S. D., & Huang, H. (2014). Service quality, perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intention among fitness centre members aged 60 years and over. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 42(5), 757–767. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2014.42.5.757

- Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60(2), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299606000203

- Zhang, Y., & Xu, L. (2021). Quality incentive contract design in government procurement of public services under dual asymmetric information. Managerial and Decision Economics, 42(1), 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.3211