ABSTRACT

Based on a sociocultural perspective, this study explores the outcome of using a model that combines storytelling and drama to teach young children science. The research question is: How is children’s learning affected when using a combination of storytelling and drama to explain a complex scientific concept?. Two preschools and one primary school were visited. Altogether 25 children aged 4–8 years participated. Each group listened to a story about The Rhinovirus Rita. No pictures were shown during storytelling. After the story was told, a play was performed with the children, telling the same story they just had listened to, and the children also made drawings. At a second visit to the schools, each child was interviewed individually and their drawings were used to stimulate recall. The results show that many of the children had learnt the names of immune system cells and how they work when someone has a cold. Moreover, they had also learnt that viruses cause colds. There were also a small number of children who did not show any learning development related to this specific content. Still, we argue that the combination of storytelling and drama is an instructional strategy that has positive potential when it comes to teaching children science.

Introduction

What matters the most regarding children’s knowledge development in science is not what they do, but how they perform the work (Harlen Citation1996). In Sweden, the primary school curriculum changed in 2011, resulting in a higher number of learning objectives in science compared to those of earlier curricula (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2011, Citation2016). Hence, current focus is mainly on what to teach (the learning objectives) and not on how to teach, which means there are higher demands on the teachers to find their own instructional strategies.

In Sweden, science education at preschool level is often dominated by thematic areas, such as water, the human body, floating and sinking, space, food, seasons, etc. (Sundberg et al. Citation2016). Even though science is part of the preschool curriculum, and thematic activities take place, preschool teachers argue that they do not feel comfortable when they teach science (Sundberg et al. Citation2016). Science is often avoided because preschool teachers have, as research has shown, low self-efficacy in teaching science (Gerde et al. Citation2018; Greenfield et al. Citation2009; Leon Citation2014; Roehrig et al. Citation2011). Primary school teachers often teach science as facts, and they do not always have the competence to teach science in a way so that pupils have the possibility to understand what science is good for or how to use the presented facts (Swedish Schools Inspectorate Citation2017). It has been argued that there is a need for teachers to develop strategies for teaching science at primary school level and that researchers should investigate different instructional strategies and their effects on learning at this level (e.g. Roth Citation2014).

Earlier studies have reported on the effects of using storytelling in science education (e.g. Klassen Citation2006; Rowcliffe Citation2004; Walan Citation2017), as well as on the use of drama when teaching science (e.g. Dorion Citation2009; McGregor Citation2012; Citation2014; McGregor and Precious Citation2010; Ødegaard Citation2003). However, few studies have investigated outcomes when storytelling and drama are combined in science education (Peleg et al. Citation2017). Bulunuz’s (Citation2013) study with a control group is one example using art, literacy, music and drama in linking scientific concepts, which resulted in a significant difference between the groups. The present study starts from the premise that aesthetic activities are an important part of the learning process (cf. Lindqvist Citation1996a; Vygotsky Citation1995), and the aim is to explore the outcome when combining storytelling and drama to teach young children science.

Storytelling and science education

Through the ages, adults have told stories to children, as stories can help children learn things more easily (e.g. Egan Citation1988). The tradition of storytelling should therefore be used a lot more in schools since children’s power of imagination is one of the strongest and most useful instruments in learning (Egan Citation1998). Bruner (Citation1991) has also argued that stories play a central role in human development and contribute to the creation of cultural traditions, tools and norms, and allow the individual to create meaning and relevance in experiences.

Negrete and Lartigue (Citation2004) have suggested that storytelling could facilitate an understanding of science and also create an interest in scientific knowledge. Stories have a structure that stimulates one’s imagination, which in turn facilitates the learning process (Solomon Citation1980). Both individuals’ own knowledge and the development of scientific knowledge draw on stories. For example, clarifying the course of events by telling them in the correct order facilitates understanding of the cause and effect of scientific phenomena (Sundberg et al. Citation2016).

In Swedish preschools, imagination and the use of stories have been and still are central and are often justified as being beneficial to children’s language development (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2019). Stories are readily linked to reading and conversations, which creates the possibility of visualizing content, structure and narrative as communicative tools. The kinds of stories being read to preschool children vary from realistic ones to classic tales about trolls and treasures (Björklund, Nilsen and Pramling Samuelsson Citation2016).

Although some researchers (e.g. Klassen Citation2006) have argued that storytelling is suitable at all levels of education, Rowcliffe (Citation2004) has claimed that storytelling is most suitable at the primary school level. In this study, storytelling is used both at preschool and primary school levels and we do not investigate whether the approach is more or less suitable at either of these levels.

Drama and science education

Drama, in its various forms, has become more widely used as an innovative pedagogy in recent decades (Dorion Citation2009). Using drama to enhance science education can promote the development of a variety of skills, such as conceptual understanding (e.g. Arieli Citation2007; Çokadar and Yılmaz Citation2010; Peleg and Baram-Tsabari Citation2011; Ødegaard Citation2003; Swanson Citation2016), and knowledge, for instance on the nature of science (e.g. Anderson and Baskerville Citation2016), or the dimensions of science in society (e.g. Ødegaard Citation2003). Drama has also been used in science education to stimulate the development of inquiry skills (McGregor Citation2012, Citation2014), as well as to assess how children progress in their knowledge and thinking about science (McGregor Citation2012).

There are several arguments for using drama in science education. Drama approaches in classrooms usually require social interaction and collaboration between participants (e.g. Dorion Citation2009). Abed (Citation2016) also discussed how drama can promote collaborative learning and thus increase students’ motivation to learn science. Furthermore, Alrutz (Citation2004) and Abed (Citation2016) reported that drama could be used successfully as a tool to stimulate students’ interest in learning science. McGregor and Duggan (Citation2017) observed that drama conventions used in strategic ways could even motivate students to want to become scientists and change the world.

However, drama is not used in schools to the same extent in different countries. In England, drama is seen as part of the curriculum (spoken English) for children aged 4–10 and pupils should be ‘enabled to participate in and gain knowledge, skills and understanding associated with the artistic practice of drama’ as well as ‘devise and script drama for one another’ to ‘rehearse, refine, share and respond thoughtfully to drama and theatre performances’ (Department for Education Citation2014). In Sweden, drama is not an independent subject in the compulsory school curriculum (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2011), but could be considered part of different subjects even if the word drama is not explicitly used. For instance, the biology curriculum states that teaching should help students develop different aesthetic expressions with scientific curriculum content. The preschool curriculum states that each child should develop their creative ability and ability to convey experiences, thoughts and experiences in many forms of expression such as play, image, movement, song, music, dance and drama (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2016). However, there are no specific instructions on how to use drama to teach science.

Theoretical framework

The study is based on a perspective stemming from who claimed that learning develops in an ongoing dialogue between the learner and the environment. This process is both reproductive and productive, which means that while we can remember and repeat what we have heard (in a broad sense), we can at the same time also shape and reshape conceptions. Vygotsky (Citation1995) called the productive aspect creativity or imagination. Imagination is commonly thought of as comprising stories, and children are thought told to have more imagination than adults. Vygotsky, however, claimed that imagination is the ability to combine experiences: the more experiences, the more material for the imagination. Hence, adults have more experience and thus more imagination. The reason why this is not always obvious, according to Vygotsky, is that children are less bound to what may or may not be possible than adults. Children might have problems with grasping complex subjects. According to Vygotsky, this is not a matter of biology, but a result of the fact that most children do not have enough experience, something which has also been claimed by Bruner (Citation1991).

Culture, art, and social processes are integrated in this holistic theory, and consciousness is a key concept and the principle of individual development. To children, play is the activity through which they become conscious, and in play, emotions, thoughts and will are united. In Vygotsky’s world, there is also a correspondence between a person’s consciousness (the internal environment) and the external environment. In play, a person’s conscious and the external environment meet in a creative process. Thus, there is an ongoing dialogue between the child and the environment in play, which promotes the child’s development (Vygotsky Citation1995). Play is therefore a powerful tool in children’s learning processes (Lindqvist Citation1996b).

Lindqvist (Citation1995, Citation1996a, Citation1996b) has developed the pedagogy of play based on Vygotsky’s theories. She gives numerous examples of how aesthetic expressions have been used in different ways to develop children’s knowledge. Storytelling and drama, as used in the present study, are seen as an important part of the learning process from this perspective, and not just an illustration to theoretical studies. They are considered aesthetic approaches serving as a link that supports the understanding of theoretical content (Lindqvist Citation1996a). In the present study, the children encounter something familiar in the form of storytelling and perhaps also dramatization, but also many new words in the content of the story itself.

Further claimed that repeating a topic at school can be boring if the revision is carried out in the same way as the topic was first presented. When a topic is repeated, a new aspect should be presented or the topic should be presented differently. Hannaford (Citation1995), who advocated repetition, stated that acting out a story is one method of repetition, which also gives a sensory understanding of the concepts involved and combines the separate parts into a whole. Batts (Citation1999) confirmed that this interactive way of solving problems, which combines visual and verbal communication, results in effective learning.

Even though there have been examples of studies integrating drama or storytelling and science, as mentioned, few studies have investigated the outcomes of using the combination of storytelling and drama as an instructional strategy when teaching science (Peleg et al. Citation2017), the focus of the current study. From Vygotsky’s theoretical perspective, this study explores the outcome of combining storytelling and drama to teach young children science. The research question is: How is children’s learning affected when using a combination of storytelling and drama to explain a complex scientific concept?

Method

This is a case study exploring the impact of combining storytelling and drama when teaching young children science.

Participants

Pupils from two Swedish preschools and two primary school classes were selected to take part in this study. We invited schools to participate based on convenience, namely their close location to the university where the researchers worked. Altogether 25 children were involved: 11 primary school children, 7–8 years old, and 14 preschool children, 4–6 years old. An overview of the participants is shown in . The parents had approved their children’s participation and gave their consent in writing. All of the children have been anonymised, using a number (1–25) as well as G (girl) and B (boy).

Table 1. Overview of participants.

Procedures: activity, data collection and analysis

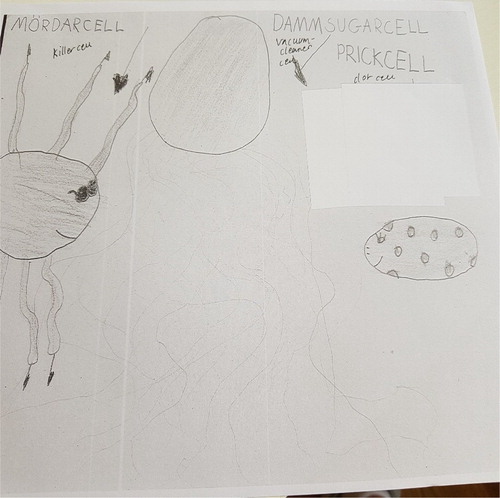

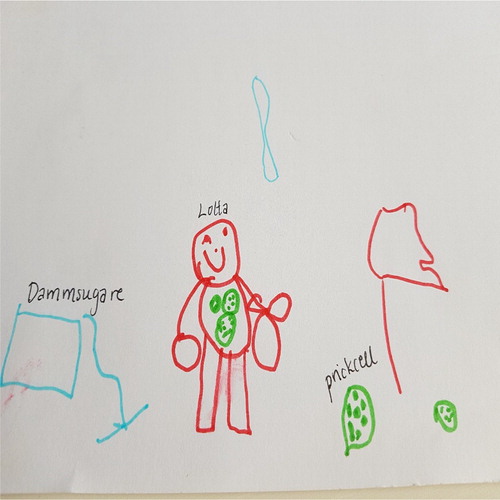

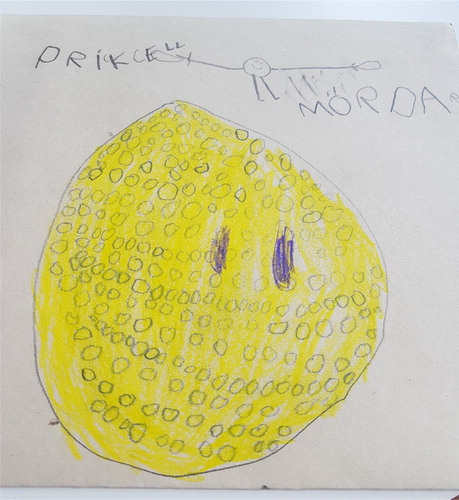

Groups of children at preschool and primary school levels were visited and the following session was held by the first author. First the researcher asked the children why people catch colds. The children replied that this is because people do not wear enough clothing or because some bacteria enter their bodies. The answers were similar in all groups. There were no differences between the children from the preschools and the primary schools. After the initial discussion a story was told to the children. The name of the story was Rhinoviruset Rita (i.e. The Rhinovirus Rita, an unpublished story written by Henrik Brändén, author of student literature in the fields of microbiology, immunology and genetics). The story is about a girl who catches a cold when a rhinovirus enters her body. The story then described how the immune system works in order to make the girl well again. Accurate scientific vocabulary is used in the story, but these concepts were also explained in simplified terms. Granulocytes were for example described as the cells with dots, and the dots as chemicals that can be used to fight against the viruses. Killer cells were not given any other name, but macrophages were talked about as vacuum-cleaner cells that ‘eat’ dead cells and viruses. The content taught in this study was way beyond the level of what is usually taught at preschool and primary school, and it does not form part of any learning objective in the curricula. The reason for choosing this content was to challenge the children and to investigate the potential of the teaching model, and also to be sure that the content had not already been taught. Furthermore, we had access to the story which had been written with this particular content and with the use of words that is of a higher level than traditional used for children. Finally, we believe that most of the children had experienced having a cold and thus they could relate to the context of the story.

No pictures were shown during storytelling. After the story had been told, a play was performed with the children, telling the same story they had just listened to. The researcher assigned a role to each of the children before the drama started. Some of the children were supposed to act as viruses and others as different parts of the immune system. The children were only supposed to follow the activities occurring in the story and try to illustrate them during the drama activity. They did not need to talk. The session was concluded by asking the children to make drawings connected to the story. The purpose of the drawings was to help the children recall and communicate their thoughts in the interview that would take place later on and not that the pictures would be a step in the learning process about the content. No discussions or guidance were made with the children when they made their drawings. The drawings were collected and saved. The whole session lasted for approximately 45 min per group.

One of the preschools and the primary school were revisited after three months, and the second preschool after five months. At the second visit, each child was interviewed individually. During the period between the visits, no feedback was given to the pupils regarding the story, the drama, or the science content in terms of conceptual knowledge about viruses and the immune system (according to information from the preschool and primary school teachers).

Each interview was semi-structured and lasted for about 20 min. All of the interviews were conducted by the first author, who talked to each of the children individually. The main questions in the interview were:

What was the story all about that you were told some time ago?

How do we catch a cold?

How do we get well again? What happens?

During the interviews, the drawings that the children had made during the first visit were shown to them and used to stimulate recall. The interviews were recorded, transcribed and inductively analysed through iterative reading of the transcripts, based on thematic coding as described by Robson (Citation2011). The coding showed a pattern of different levels of understanding of the content among the children. The two researchers agreed on the themes and five categories were identified that are described in the next section.

Results

The aim of this study was to test a model in which drama and storytelling were connected in order to facilitate learning processes in science for young children. The data analysis of the interviews with the participating children revealed diversity in their understanding of the content that was presented during the story and drama activity. Some of the children showed that they had gained knowledge about cells and how they function when we catch a cold; others only presented fragments of the content that had been presented during the activities. There were also children who did not remember much from the story and the drama activity, hence no learning could be identified. The answers given during the interviews were divided into five different categories. The children were placed in the five different categories as presented in . A more detailed description of the results from each of the categories follows below.

Table 2. Number of children per category, based on the interviews.

Category 1- learning about immune system cells and how they function when we catch a cold, connected to reality

During the interviews, two of the primary school children and two of the preschool children included the scientific names of the characters in the story and they were able to make the connection to reality, explaining to the interviewer that this is what happens in the body when we are sick and are getting well again. They also mentioned that viruses cause colds, saying for example:

Well, there are viruses. They came into the throat of the girl. It was rhinoviruses … .

They [the viruses] started to become lots and her throat started to hurt. Then the

cells with the dots came and started to fight against the viruses. But, they could not cope with them by themselves so more support came, the killer cells. Finally, when all of the viruses were killed the macrophages came and vacuum-cleaned the area and then the girl became well again, and that was the end of the story. But, this is also the truth; it is not only a story. You know, this is what happens in our body when we catch a cold and then the body fights and makes us well again. (G7, 8 years)

There were viruses in the throat and Lotta [the name of the girl in the story] felt that it was hurting. She also became tired and they noticed that she had fever. It was the brain that had started the fever to help to fight against the viruses. (B6, 5 years)

Category 2 - learning about immune system cells and how they function when we catch a cold, not connected to reality

Six of the primary school children and three of the preschool children were placed in the second category. They mentioned all the cell types and viruses. However, they did not make any connections showing that they understood that this is real. Typically the children placed in this category used phrases that are often part of stories, such as ‘once upon a time’, and ‘they lived happily ever after’. In the interviews, they for example said:

Well, the story was about rhinoviruses and they were destroying in the body and they became more and more … the girl had some pain and she needed help from the cells with the dots and killer cells and the vacuum-cleaner cells, and then everything was fine again and she lived happily ever after. (G1, 7 years)

Once upon a time there was this girl Lotta. She had some pain in her throat, because there were some things that had entered and they were causing the pain. She got some help from the cells with dots and killer clls and vacuum-cleaner-cells. And the brain made the body warmer so the girl needed to rest and then she became well again. (G12, 5 years) .

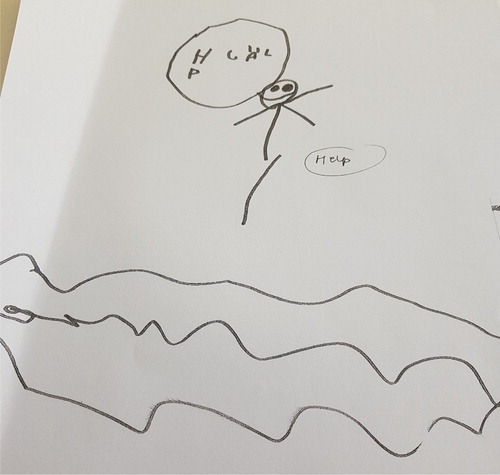

Figure 1. Drawing by a child (B6), who was placed in the first category, showing knowledge about the immune system cells and that viruses cause colds. The word ‘Hjälp’ (Eng. ‘Help’) is written in the picture.

Category 3 - fragmented learning on immune system cells

Three of the primary school children and two of the preschool children were placed in the third category, since it was only possible to identify fragments of learning about the content presented during the story and drama activity. In the interviews, children in this category for example said:

What I remember is that there were vacuum-cleaner cells, killer cells and dotted cells, and they tried to catch the viruses, somehow … I don’t remember that much … (B1, 8 years).

It was about the body. There were small round things inside the body. It was about how you get ill. The forehead is warm … (G15, 5 years) .

Category 4 – making up a new story that includes bacteria

Two of the preschool children made up their own stories during the interview. Both of these stories contained bacteria even though this was not part of the original story and drama activity. These children were placed in this fourth category, and examples from their stories include:

I have painted my father and he is the apple tree and he is sick … because there are bacteria … (G17, 4 years).

There are bacteria in the mouth and they also come out of the nose and they flew on a girl and then she became invisible, but a doctor came and he helped her to get well again. (G18, 4 years) .

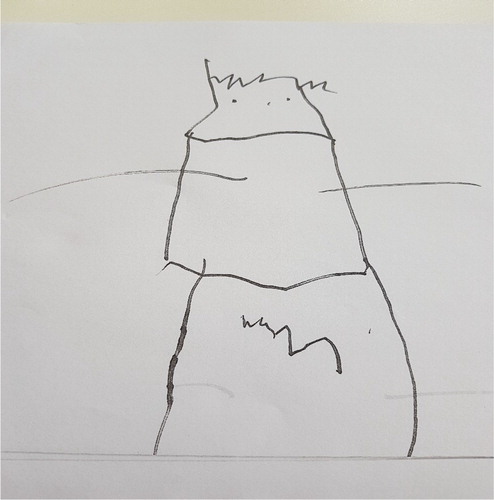

Category – no identified learning

Four of the preschool children were placed in a fifth category, as they were not able to recall much from the activities, not even with their drawings in front of them. Hence, these children used phrases like ‘I don’t remember’, or single words such as ‘bacteria’, not viruses. One of the children mentioned the name of the girl in the story and that she was ill, but not much more:

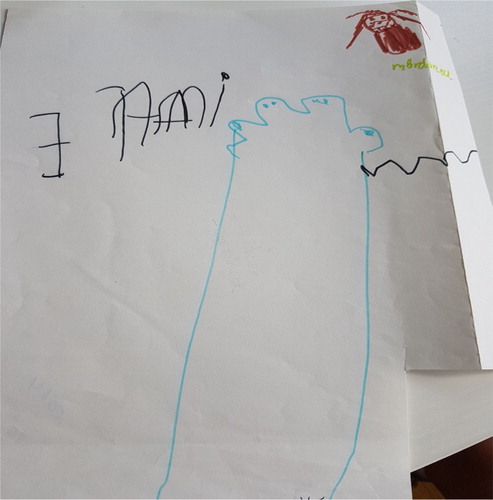

Figure 5. Drawing by a child (G18), placed in the fourth category, who made up her own story that includes bacteria.

Lotta, she became ill. (B4, 4 years) .

Finally, presents an overview of how many preschool and primary school children were placed in each of the categories. Many of the children were able to show some understanding of the content that was presented in the story and drama activities, as they thought that this happens in our bodies, or they at least knew the scientific concepts that had been presented. Only the youngest children were placed in the categories that did not represent anything of the science content presented in the story and the drama.

Discussion

Previous studies have argued that there is a need to develop instructional strategies for teaching children science (e.g. Roth Citation2014) and that storytelling (e.g. Negrete and Lartigue Citation2004), drama (e.g. McGregor Citation2012), and also the combination of art, literacy, music and drama (Bulunuz Citation2013) are successful strategies in this respect. This study therefore aimed to investigate how these strategies in combination could facilitate learning processes for young children. Although we thought it would be possible, we were still surprised that so many of the children were able to present as much of the content from the story and drama activities as they did, and that they in some cases also were able to relate to reality even though we only had one session, and no feedback was given between the intervention and the interviews. Furthermore, the scientific content presented to the children is complex and abstract and is usually only taught at higher school levels. Following Vygotsky (Citation1995), even young children can develop knowledge when they are given more experiences that can be combined. In this study, the scientific content was explained in several ways through play, which works as a link to support the understanding. Most the children showed that they had learnt that viruses are involved when we catch a cold. This was not mentioned by any child before the sessions. The children only talked about the content that had been presented during the teaching session and did not elaborate their thoughts by for example showing awareness about hygiene and diseases, since this was never discussed. However, we do not know if the children talked about the activity with their parents and because of this were further stimulated in their recall and learning about the process presented. Maybe it could be argued that children from academic backgrounds showed better results? However, in this case the children came from locations with heterogeneous socio-economic backgrounds, and the results could not be explained based on such assumptions.

All the primary school children showed a positive result in terms of demonstrating that they had learnt the names of immune system cells and how they work, as well as that viruses cause colds. In the preschools, the results were more varied. Although not all the children could show that they had learnt everything that was introduced during the session, many of them were still able to present quite a lot of the content after such a long time. The differences between the age groups is not surprising: the older a person is, the more experience he/she has from which to combine elements to build new knowledge (e.g. Bruner Citation1971; Vygotsky Citation1995). This does not mean that it would be a waste of time teaching preschool children. As is shown here, even some of the preschool children were placed in the first category, showing that they had learnt the scientific names of cells and also were able to understand that this really happens in our bodies. The others may perhaps find it easier to understand these concepts the next time they encounter them. Since unequal numbers of girls and boys participated in the study, we did not investigate whether there were any gender-based differences in the results. This could be of interest in future studies.

It is difficult to determine whether the instruction led to the result or whether young children could learn about viruses if taught differently, as there is not much research in this area. We did not compare our intervention with another way of teaching. Future studies could therefore compare the results from teaching the same content using different strategies (e.g. only using storytelling, only drama, using none of these strategies, or combining them). Conducting experimental studies like this one is complicated in school settings, since it is difficult to eliminate all factors that can have impact on learning. Here we have shown an example that seems to work well, but it was impossible to identify from the interviews with the children if they learned the content mainly because of being told the story, acting it out, or the combination of these activities. What we do know from earlier studies is that using stories (e.g. Negrete and Lartigue Citation2004) and drama (e.g. McGregor Citation2014; Ødegaard Citation2003) has a positive impact when teaching science. However, we believe that using these two strategies in combination can enhance learning based on the arguments from instance Batts (Citation1999), Hannaford (Citation1995) and also our theoretical framework drawing on the work of Vygotsky (Citation1995).

Finally, it could be argued that the children’s drawings perhaps had an impact on how they could recall the content of the story and the drama and explain what they knew about catching a cold and the immune system. Quillin and Thomas (Citation2015) claimed that it is difficult to imagine teaching and learning in science without using visual representations. They also encouraged students of all ages to create drawings, which has been considered a powerful tool for thinking and communicating in any discipline (Roam Citation2008). The use of drawings was not actually supposed to be part of the teaching model, but only to serve as a tool during the interviews. Maybe it could be argued that the use of pictures was a part of the model. Therefore, in future studies this also needs to be considered.

However, we cannot find any evidence for the impact of the drawings in our study, since the children’s drawings included more or less details. In the first category, for instance, the five-year-old boy only had a picture of what seems to be a person (), yet he presented all the details from the presented content and was able to relate the fact that this happens in our bodies when we catch a cold. Another example is a five-year-old girl who was placed in the second category; she talked about almost all of the scientific concepts from the activities, even though she only had a picture () of a dotted cell (granulocyte). According to we do not know exactly what makes a person react to aesthetic expressions, since he claims it is an individual process. Future studies could further explore the effect of using drawings when teaching science in early years.

Conclusion

We found that the combination of storytelling and drama is an instructional strategy that has a positive potential when it comes to teaching children science. As this a case study involved only a few children, it raises more questions than it provides answers, and some of these questions have been discussed above. Still we claim that this model is a way to make science and scientific concepts understandable, even to young children, and using the combination of drama and storytelling is an area of interest that should be explored further by preschool teachers and researchers. Moreover, authors writing children’s books could be encouraged to include scientific words if they also are explained. Doing so may help children to develop their scientific knowledge even more in the early years, and they indeed seem capable based on the results from this study from only one teaching session.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Susanne Walan http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9060-9973

References

- Abed, O. H. 2016. “Drama-based Science Teaching and its Effect on Students’ Understanding of Science Concepts and Their Attitudes Towards Science Learning.” International Education Studies 9 (10): 163–173.

- Alrutz, M. 2004. “Energy matters. An Investigation of Drama Pedagogy in the Science Classroom.” Dissertation. Arizona State University, Arizona.

- Anderson, D., and D. Baskerville. 2016. “Developing Science Capabilities Through Drama: Learning About the Nature of Science Through a Guided Drama–Science Inquiry Process.” Set: Research Information for Teachers 2016 (1): 17–23.

- Arieli, B. 2007. “The Integration of Creative Drama Into Science Teaching.” Doctoral Thesis, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KA. http://krex.kstate.edu/dspace/bitstream/2097/531/1/BrachaArieli2007.pdf.

- Batts, G. R. 1999. “Learning About Colour Subtraction by Role Play.” School Science Review 80 (292): 99–100.

- Björklund, C., M. Nilsen, and I Pramling Samuelsson. 2016. “Berättelser som redskap för att föra resonemang.” Nordic Early Childhood Education Research Journal 12 (5): 1–18.

- Bruner, J. S. 1991. På väg mot en Undervisningsteori (Toward a Theory of Instruction, 1966). Translated by S. Olsson. Lund: Gleerups.

- Bulunuz, M. 2013. “Teaching Science Through Play in Kindergarten: Does Integrated Play and Science Instruction Build Understanding?” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 21 (2): 226–249. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2013.789195.

- Çokadar, H., and G. Yılmaz. 2010. “Teaching Ecosystems and Matter Cycles with Creative Drama Activities.” Journal of Science Education and Technology 19 (1): 80–89. doi:10.1007/s10956-009-9181-3.

- Department for Education. 2014. The National Curriculum. www.gov.uk/dfe/nationalcurriculum.

- Dorion, K. 2009. “Science Through Drama: A Multicase Exploration of the Characteristics of Drama Activities Used in Secondary Science Classrooms.” International Journal of Science Education 31 (16): 2247–2270.

- Egan, K. 1988. Teaching as Storytelling: An Alternative Approach to Teaching and the Curriculum. London: Routledge.

- Gerde, H., S. Pierce, K. Lee, and L. Van Egeren. 2018. “ Early Childhood Educators’ Self-Efficacy in Science, Math, and Literacy Instruction and Science Practice in the Classroom.” Early Education and Development 29 (1): 70–90. doi:10.1080/10409289.2017.1360127.

- Greenfield, D. B., J. Jirout, X. Dominguez, A. Greenberg, M. Maier, and J. Fuccillo. 2009. “Science in the Preschool Classroom: A Programmatic Research Agenda to Improve Science Readiness.” Early Education and Development 20 (2): 238–264.

- Hannaford, C. 1995. Smart Moves: Why Learning is not all in Your Head. Arlington: Great Ocean Publishers.

- Harlen, W. 1996. Våga Språnget - Om att Undervisa Barn i Naturvetenskapliga ämnen. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Klassen, S. 2006. “A Theoretical Framework for Contextual Science Teaching.” Interchange 37 (1): 31–62.

- Leon, K. 2014. “Do You See What I See? Exploring preschool Teachers ‟ Science Practices.” Unpublished Mater dissertation California State University, Northridge. file:///C:/Users/Xx/Downloads/Leon_Katherine_thesis_2014.pdf.

- Lindqvist, G. 1995. “The Aesthetics of Play: A Didactic Study of Play and Culture in Preschools (Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, no 62).” Published Doctoral Dissertation. Uppsala: Uppsala University.

- Lindqvist, G. 1996a. Från konstens psykologi till en allmän teori om tänkandet (Utvecklingsrapport No. 96:2). Karlstad.

- Lindqvist, G. 1996b. Lekens Möjligheter [The Possibilities of Play]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- McGregor, D. 2012. “Dramatizing Science Learning: Findings From a Pilot Study to Reinvigorate Elementary Science Pedagogy to Five-to-Seven Year Olds.” International Journal of Science Education 34 (8): 1145–1165.

- McGregor, D. 2014. “Chronicling Innovative Learning in Primary Classrooms: Conceptualizing a Theatrical Pedagogy to Successfully Engage Young Children Learning Science.” Pedagogies: An International Journal 9 (3): 216–232.

- McGregor, D., and A. Duggan. 2017. “Theorising about Pedagogy To Teach Inquiry Science Using Process Drama: A Synthesis From Practice.” BERA Annual Conference 6.9.17 Sussex University.

- McGregor, D., and W. Precious. 2010. “Applying Dramatic Science to Develop Process Skills.” Science and Children 48 (2): 56–59.

- Negrete, A., and C. Lartigue. 2004. “Learning From Education to Communicate Science as a Good Story.” Endeavour 28 (3): 120–124.

- Ødegaard, M. 2003. “Dramatic Science. A Critical Review of Drama in Science Education.” Studies in Science Education 39 (1): 75–101.

- Peleg, R., and A. Baram-Tsabari. 2011. “Atom Surprise: Using Theatre in Primary Science Education.” Journal of Science Education and Technology 20: 508–524. doi:10.1007/s10956-011-9299-y.

- Peleg, R., M. Yayon, D. Katchevich, R. Mamlok-naman, I. Eilks, and A. Hofstein. 2017. “Teachers’ Views on Implementing Storytelling as a way to Motivate Inquiry Learning in High-School Chemistry Teaching.” Chemistry Education Research and Practice 18 (2): 304–309.

- Quillin, K., and S. Thomas. 2015. “Drawing-to-Learn: A Framework for Using Drawings to Promote Model-Based Reasoning in Biology.” CBE-Life Sciences Education 14: 1–16. doi:10.1187/cbe.14- 08-0128.

- Roam, D. 2008. Back of the Napkin: Solving Problems and Selling Ideas with Pictures. New York: Penguin.

- Robson, C. 2011. Real World Research: A Resource for Users of Social Research Methods in Applied Settings. 3rd ed. West Sussex: Wiley.

- Roehrig, G. H., M. Dubasky, A. Mason, S. Carlson, and B. Murphy. 2011. “We Look More, Listen More, Notice More: Impact of Sustained Professional Development on Head Start Teachers’ Inquiry-Based and Culturally-Relevant Science Teaching Practices.” Journal of Science Education Technology 20: 566–578.

- Roth, K. J. 2014. “Primary Science Teaching.” In Handbook of Research in Science Education, edited by N. G. Lederman and S. K. Abell (Vol. 2, pp. 361–394). London: Routledge.

- Rowcliffe, S. 2004. “Storytelling in Science.” School Science Review 86 (314): 121–126.

- Solomon, J. 1980. Teaching Children in the Laboratory. London: Croom Helm.

- Sundberg, B., S. Areljung, K. Due, C. Ottander, and B. Tellgren. 2016. Förskolans Naturvetenskap i Praktiken. Malmö: Gleerups utbildning AB.

- Swanson, C. 2016. “Positioned as Expert Scientists: Learning Science through Mantle of the Expert at Years 7/8.” PhD, Waikato University, Hamilton, New Zealand. http://hdl.handle.net/10289/9974.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. 2011. Curriculum for the Compulsory School System, the pre-School Class and the Leisure Time Centre 2011 (Revised 2016). Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. 2016. Läroplanen för förskolan Lpfö98. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. 2019. Flerspråkighet i förskolan. Retrived from https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/inspiration-och-stod-i-arbetet/stod-i-arbetet/flersprakighet-i-forskolan.

- Swedish Schools Inspectorate. 2017. Tematisk analys: Undervisning i NO-ämnen [Thematic Analysis: Teaching Science]. Stockholm: Swedish Schools Inspectorate.

- Vygotsky, L. S. 1995. Fantasi och kreativitet i barndomen (Voobraženie i tvorčestvo v detskom vozraste, 1930). Translated by K. Öberg Lindsten. Gothenburg: Daidalos.

- Walan, S.. 2017. “Teaching Children Science Through Storytelling Combined with Hands-on Activities – a Successful Instructional Strategy?” Education 3-13 47 (1): 34–46. doi:10.1080/03004279.2017.1386228.