ABSTRACT

The purpose of this literature review is to identify patterns and discuss key perspectives from empirical studies published during the last decade that explore how young children (birth to six years old) and teachers together engage with digital technologies in early childhood education and care institutions. An inductive thematic analysis results in five key perspectives: 1) digital play is real play; 2) disconnected contexts; 3) teachers’ knowledge and beliefs; 4) learning with and from technology; and 5) children as creators. The findings demonstrate the importance of defining digital technology in a broad way. Further, several of the articles highlight teachers’ reflections and judgements regarding how they can implement and embed digital technology into their pedagogical practice. Based on the findings, I suggest that a more explicit focus on digital technology be embedded into pedagogical practice in national ECEC curricula, as well as in national guidelines for EC teacher education.

Introduction

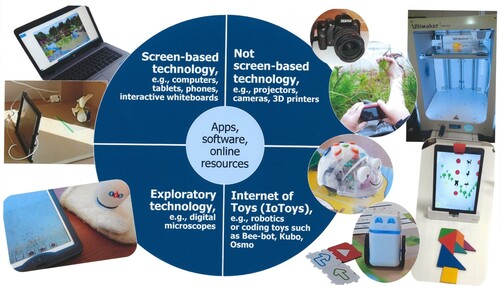

The purpose of this literature review is to identify patterns and discuss key perspectives from empirical studies exploring young children (birth to six years old) and teachers engaging together with digital technologies in early childhood education and care (ECEC) institutions. I will present a synthesis of empirical studies focusing on various digital technologies used together with children in ECEC by examining a sampling of studies conducted between 2010 and 2020. My definition of digital technology includes digital tools and devices as well as digital resources and media, in line with Fjørtoft, Thun, and Buvik (Citation2019, 111): ‘Digital tools refer to various types of computers and tablets, interactive screens, cameras, equipment for programming, and other types of digital production. Digital resources refer to the digital content used together with the children, both online content and apps or software to be installed’ (translated by the author).

Today, many young children grow up in societies with broad access to various digital technologies intertwined in their everyday lives (Arnott and Yelland Citation2020; Chaudron, Di Gioia, and Gemo Citation2018; Danby et al. Citation2018; Yelland Citation2017). For these children, digital technology, such as tablets and smartphones, has always been there: ‘Technology, as was once said, is not technology if it happened before you were born’ (Robinson Citation2011, 76). However, with the increasing use of digital technology in society, it is important to critically examine and reconsider the ways in which the children use and engage with the technology, at home and in ECEC institutions (Holloway, Green, and Livingstone Citation2013; Yelland Citation2017). In ECEC, children still need guidance and support from proximal teachers, who make critical reflections on the possibilities and limitations of integrating digital technology, teachers who reflect upon when, how and why when using digital technology together with the children (Gibbons Citation2010; Jernes and Engelsen Citation2012; Selwyn Citation2010; Stephen and Edwards Citation2018).

In this paper, the two perspectives of the children and the teachers will be central, as well as their engagement together as active participants, in line with a critical and reflective focus to understand the ‘state-of-the-actual’ of technology use in ECEC (Selwyn Citation2010, 69-70). I consider children’s active participation in society to be a core value, in line with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (Citation1989, Article 12). Consequently, only studies focusing on children as active participants are included.

Next, I will provide some insights into digital technology in ECEC by drawing on previous literature reviews before going deeper into the key perspectives.

Previous literature reviews

The first international literature reviews of the use of digital technology among young children and teachers in ECEC were conducted in 2003 and 2005; in these reviews the researchers describe the use of digital technology with 3- to 5-year-olds (Plowman and Stephen Citation2003; Stephen and Plowman Citation2003; Yelland and Masters Citation2007). At that time, the term digital technology mainly referred to computers, and the teachers mostly incorporated the technology into their existing practices as an ‘add-on’ – instead of looking at the new opportunities provided by the technology. Stephen and Plowman (Citation2003) conclude that digital technology can be a valuable addition to teachers’ practices, but this depends on teachers’ pedagogical knowledge and expertise. These three literature reviews are the only ones, to my knowledge, that have focused on both children’s and teachers’ technology use (Plowman and Stephen Citation2003; Stephen and Plowman Citation2003; Yelland and Masters Citation2007) (Appendix1).

Other previous reviews have focused on more specific aspects of technology use, such as technology and literacy (Belo et al. Citation2016; Burnett Citation2010; Kucirkova et al. Citation2019), technology and learning (Hsin, Li, and Tsai Citation2014), technology in relation to healthy practices, relationships, pedagogy and digital play (Mantilla and Edwards Citation2019), research design and methodologies (Miller et al. Citation2017), and the Internet of Toys (IoToys) (Ling et al. Citation2021) (Appendix 1). The researchers highlight a need for more research focusing on the way social interactions unfold during children’s engagement with digital technology (Miller et al. Citation2017), research that includes digital and non-digital activities and the teachers’ role (Belo et al. Citation2016), and research on young children’s use of a wide range of digital technologies (Burnett Citation2010).

Methodology

The purpose of this literature review is to identify patterns, discuss key perspectives, and provide new perspectives to the existing literature (Booth, Sutton, and Papaioannou Citation2016; Grant and Booth Citation2009). The literature review can be described as a configurative review (Booth, Sutton, and Papaioannou Citation2016) of peer-reviewed research articles published in national and international journals between 2010 and 2020. The research question is as follows: What are the key perspectives from research exploring how young children and teachers engage with digital technologies together in ECEC?

Search procedures

Systematic searches were performed in October 2020 in Academic Search Premier, ERIC, Scopus, Web of Science, and Idunn.Footnote1 I used two search strings across these databases: ‘(early childhood education OR preschool OR kindergarten OR early years) AND (digital tools) AND (technology OR technologies)’ and ‘(early childhood education or preschool or kindergarten) AND (digital technology OR digital technologies) AND (teachers OR educators) AND (pedagogy OR pedagogical)’. In Idunn, I also included similar search strings in Norwegian.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

By drawing on the wide definition of digital technology presented in the introduction, this literature review focuses on young children’s (0-6 years old) and teachers’ collaborative use of various digital technologies in ECEC institutions (). Children’s participation is essential, and studies of teachers using digital technology without including children are excluded, as are studies focusing on older children or adults. Moreover, children’s use of digital technology at home or together with parents and other caretakers are also excluded.

Table 1. Literature search.

Further, only English and Norwegian search terms are used, which limits the findings to articles presented in these languages. Two articles written by me are also included because they were found through the literature search. However, by only including articles found through searches in specific databases that can be accessed from a Norwegian university, other relevant articles may have been excluded. Reviewing previous research is essentially an act of interpretation; therefore, to ensure transparency, I have clearly stated the research question guiding this review and the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

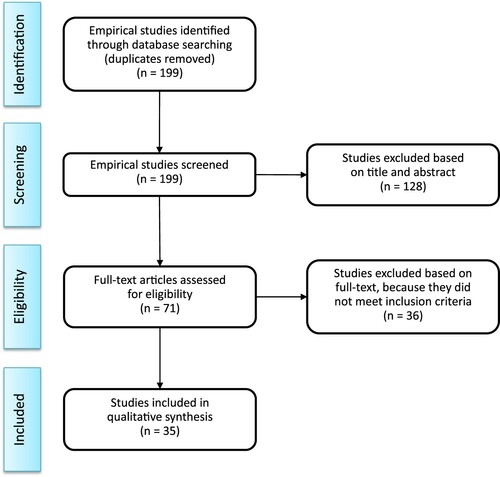

The searches resulted in 199 articles. Drawing on Booth, Sutton, and Papaioannou (Citation2016) and Moher et al. (Citation2009), these articles were scanned to assess their relevance based on the title, abstract and keywords (). Among these articles were 128 articles that focused on older children or adults, e.g. in higher education; these were excluded. The remaining 71 articles were then read thoroughly. Based on an informed filtering of what to include, more articles were excluded because they did not meet my inclusion criteria; they did not have a clear focus on digital technology used together with children in ECEC institutions. Ultimately, 35 peer-reviewed research articles were included in this literature review (see Appendix 2).

Figure 1. Process of selecting studies, adapted from Moher et al. (Citation2009, 3).

Analysis

To identify patterns and explore variations to point out key perspectives, an inductive thematic analysis of the 35 included articles was provided (Bearman and Dawson Citation2013; Braun and Clarke Citation2006). First, each article was read thoroughly to identify themes that represented how digital technology were used together with the children. Then, I explored how these themes emerged across the articles and the relationships between the themes. During this process, the themes were refined, adjusted and grouped together into five key perspectives that synthesises the findings: 1) digital play is real play; 2) disconnected contexts; 3) teachers’ knowledge and beliefs; 4) learning with and from technology; and 5) children as creators ().

Table 2. Key themes in relation to each study

Results

Overview of the reviewed studies

All the included articles were published in international journals between 2012 and 2020. The articles draw on studies conducted in several countries across the world (Appendix 2). Pedagogical or educational uses of digital technology in ECEC, such as children’s play and learning, creative processes, and teachers’ pedagogical beliefs are emphasised in 24 of the 35 articles (). This is not surprising, due to my search for studies exploring children’s and teachers’ collaborative engagement with digital technology in ECEC. Most of the reviewed studies are descriptive studies, and the researchers mostly describe the use of technology in a positive way. Six of the studies provide some critical perspectives (Alvestad et al. Citation2017; Hoel and Jernes Citation2020; Jernes and Engelsen Citation2012; McGlynn-Stewart et al. Citation2018; Skantz Åberg, Lantz-Andersson, and Pramling Citation2014; Undheim and Jernes Citation2020), but only one study can be described as being critical (Lafton Citation2019). Further, most of the studies draw on socio-cultural perspectives, which leaves room for further studies drawing on other theoretical perspectives, for example, multimodality or actor-network theory. Most of the studies use several data collection methods, such as interviews and observations of teachers and children. Only four studies include children under the age of three (Fleer Citation2020; Jernes and Engelsen Citation2012; Lafton Citation2019; Ljunggren Citation2016) (Appendix 2).

Digital technology used in an educational setting, such as in ECEC, is often described as educational technology; however, according to Jack and Higgins (Citation2019), no consistent definition of educational technology is available. While a narrow definition of digital technology often views technology only as computers or screens, a wider definition includes digital technology that may offer imaginative, creative and collaborative activities (Fleer Citation2019; Jack and Higgins Citation2019; Kewalramani et al. Citation2020; Palaiologou Citation2016), as presented in . Johnston, Highfield, and Hadley (Citation2018) highlight the importance of also including imaginary technology, such as non-functioning keyboards and phones, when defining digital technology; these technologies are often included in children’s play.

Digital play is real play

Traditional beliefs about play, particularly the value of open-ended and exploratory play, can be seen as barriers to digital technology integration in ECEC (Edwards et al. Citation2020). However, for many children growing up today, digital technology is as natural as any other artefact or tool (Edwards et al. Citation2020; Fleer Citation2020). Fleer (Citation2020) observed that the children used digital technology in distributed ways across the various activities and rooms in the ECEC settings and included the technology in their play. However, as the digital technology became part of the social practices in these ECEC settings, more complex social practices emerged, for example, when the children started to record each other’s play. Afterwards, when watching their recorded play, the children experienced a form of re-play. In this way, the digital equipment supported the children’s play by allowing the children to make the rules, roles and actions visible to themselves, each other and their teachers (Fleer Citation2020). These new possibilities inspired the children to re-imagine and re-create stories in their imaginary play by using a mix of artefacts and playful practices; further, it became impossible to separate the activities into ‘real’ play and digital play (Fleer Citation2019, 2020).

A similar finding is related to the IoToys (Kewalramani et al. Citation2020). When the IoToys were included in children’s play, mutual multilayer interactions among the teachers, the children and the IoToys emerged; this created new experiences and sparked children’s creative, communicative and problem-solving dispositions. The key is to understand the multiplicity of these interactions, according to Kewalramani et al. (Citation2020).

To meet these new and transformative conditions for children’s play, Edwards et al. (Citation2020) introduced the concept of converged play. As highlighted by several researchers (e.g. Edwards et al. Citation2020; Fleer Citation2019, 2020; Lafton Citation2019), it has become almost impossible to distinguish between ‘real’ play and digital play today because children’s various play practices are so interrelated with each other and continuously moving towards each other. According to Lafton (Citation2019), the spheres where technology and traditional toys are present overlap with each other in children’s play. Fleer (Citation2019, 214) describes these practices as a ‘coalition of practices’ that create new transformative conditions for children in a play-based learning environment. Converged play can be seen as the starting point of a movement towards helping teachers understand teaching and learning in the digital age – an age in which children’s experiences of digital technologies, media, and popular culture within their homes also must be taken into account (Edwards et al. Citation2020).

Disconnected contexts

Several researchers point to a gap – or a disconnect – between children’s access to and experiences with digital technology at home and that in ECEC (e.g. Aldhafeeri, Palaiologou, and Folorunsho Citation2016; Alvestad et al. Citation2017; Aubrey and Dahl Citation2014). Alvestad et al. (Citation2017), for example, found a gap between the children’s and teachers’ everyday experiences; when the children talked about games they played and TV programmes they watched at home, it was hard for the teachers to understand what the children were talking about. According to Aubrey and Dahl (Citation2014), many teachers express a poor awareness and understanding of the contribution that digital technology plays in young children’s lives outside of ECEC. Supporting children today is a diverse and complex issue that requires connections between the home and ECEC settings (Aldhafeeri, Palaiologou, and Folorunsho Citation2016). Further, it is important that EC teachers recognise that there is a ‘digital difference’ between these contexts (Aldhafeeri, Palaiologou, and Folorunsho Citation2016) and acknowledge children’s home experiences of digital technology, media, and popular culture (Edwards et al. Citation2020).

Teachers’ knowledge and beliefs

Several of the reviewed studies point to a lack of knowledge among the teachers of how to integrate technology into play-based pedagogy (Aubrey and Dahl Citation2014; Jack and Higgins Citation2019; Johnston, Hadley, and Waniganayake Citation2020; McGlynn-Stewart et al. Citation2017; Vidal-Hall, Flewitt, and Wyse Citation2020). In some of the studies, the teachers reported that they would like more professional support regarding the pedagogical uses of digital technology in ECEC (Aubrey and Dahl Citation2014; Jack and Higgins Citation2019). In some of the reviewed studies, the teachers were supported during the research in learning how to use certain technologies and how to integrate them into their practice; the teachers in these studies repeatedly expressed that these discussions and reflections were essential for their technological and pedagogical professional development (Johnston, Hadley, and Waniganayake Citation2020; McGlynn-Stewart et al. Citation2017; Vidal-Hall, Flewitt, and Wyse Citation2020).

On the one hand, teachers’ knowledge of digital equipment and resources impacted how the technology was integrated as a pedagogical resource (Jack and Higgins Citation2019). On the other hand, the integration of digital media was not constrained by a lack of knowledge alone, according to Vidal-Hall, Flewitt, and Wyse (Citation2020), but rather by how the teachers’ pedagogical beliefs and practices interacted with their beliefs about digital technology and young children. Some teachers’ beliefs about digital technology conflicted with their pedagogic principles of child-initiated play, which shaped their decisions about integrating digital technology into ECEC (Edwards et al. Citation2020; Vidal-Hall, Flewitt, and Wyse Citation2020). However, as shown in several articles, the teachers’ beliefs that do hinder technology use can be replaced with ‘new’ beliefs that support the use of digital technology through professional development, discussions and critical reflections (Johnston, Hadley, and Waniganayake Citation2020; McGlynn-Stewart et al. Citation2017; Vidal-Hall, Flewitt, and Wyse Citation2020).

According to several researchers, assumptions about the nature of play-based pedagogy and the potential uses of digital technology have created tensions and confusion among teachers in ECEC (Aldhafeeri, Palaiologou, and Folorunsho Citation2016; Palaiologou Citation2016; Sulaymani, Fleer, and Chapman Citation2018). While the teachers in some studies demonstrated fears about digital technology having a negative impact on children in terms of their well-being, social development and health (e.g. Vidal-Hall, Flewitt, and Wyse Citation2020), other studies observed that the teachers showed a positive attitude towards the use of digital technology (e.g. Aubrey and Dahl Citation2014; Jack and Higgins Citation2019).

Learning with and from technology

In several of the reviewed studies, the technology was seen as a useful resource in mathematical learning, literacy learning, and exploratory learning, to follow up on children’s interests in meaningful ways (Johnston, Highfield, and Hadley Citation2018). In an interview study (Dunn et al. Citation2018), the children highlighted the play possibilities when tablets were used. For the children, it was important to have a choice – not necessarily of which app to use, but the choices within the app were important for the children; for example, in open-ended apps, they could create their own content, unlike in closed apps that focused on drills and practice (Dunn et al. Citation2018). In some of the studies, technology is seen as a useful resource to learn from, but most of the studies focus on children’s learning with the technology, for example, in mathematical learning.

Mathematical learning

Three of the reviewed studies focus on the use of digital technology in children’s early mathematical learning (Bourbour and Masoumi Citation2017; Carlsen Citation2013; Carlsen et al. Citation2016), which can be described as learning with technology. However, digital technology carries both affordances and constraints with respect to participants’ collaboration (Carlsen et al. Citation2016). Some mathematical apps focus on doing something with mathematical objects, such as moving them. According to Carlsen, the technology has limitations with respect to actively engaging two children at the same time, especially when an app is used on a computer with a mouse – in contrast to an interactive whiteboard, which potentially allows more collaboration between the children. Hence, it is difficult to know how and if the app supports the children’s mathematical development because the digital equipment that is used may affect how difficult it is for the children to use the app (Carlsen Citation2013; Carlsen et al. Citation2016). Further, the mere fact of having or using an interactive whiteboard does not create a dynamic and rewarding learning environment – that depends on how the whiteboard is embedded into the pedagogical practice by the teachers (Bourbour and Masoumi Citation2017, 1829).

Literacy learning

Seven of the reviewed studies focus on children’s literacy learning or development with technology (Hoel and Jernes Citation2020; Ljunggren Citation2016; McGlynn-Stewart et al. Citation2017, Citation2018; Sandvik, Smørdal, and Østerud Citation2012; Skantz Åberg, Lantz-Andersson, and Pramling Citation2015; Yelland Citation2018).

Some of these articles explored children using open-ended iPad apps to document their work (McGlynn-Stewart et al. Citation2017, Citation2018; Yelland Citation2018). The multimodal affordances of the open-ended apps, such as photos, videos, drawings, texts and audio recordings, allowed the children to communicate, collaborate, explore and create products that were meaningful to them. The apps could be used in any way that the teachers or children chose and provided various learning scenarios (Yelland Citation2018). Several of the children integrated the apps with other resources, such as books, cards, pencils, crayons and sand, which enabled the children to experience early literacy concepts in dynamic interactive and multimodal contexts that built on and extended their ‘real-world’ play experiences (McGlynn-Stewart et al. Citation2017, Citation2018; Yelland Citation2018). Everything the children made could be saved, which scaffolded their reflection and encouraged them to continue to explore their interests over time (McGlynn-Stewart et al. Citation2018).

However, the technology may not always provide good learning opportunities. Hoel and Jernes (Citation2020) found that when digital picture book apps were used in shared dialogue-based reading activities with groups of children, the interactive affordances within the app limited the dialogue between the children and the teachers, especially during the first reading. The children were mostly engaged with the hotpots and concerned with who was next for clicking on the hotspots; the researchers observed a tension between the teachers’ didactical intension and the interactive picture book app. During the second reading, however, the teachers were more prepared and took more control of the situation. This study indicates that when reading digital books with groups of children, the less interactive the book is, the better – if the aim is shared dialogue around the book and the narrative (Hoel and Jernes Citation2020).

Exploratory learning

Another way digital technology is used in ECEC is in exploratory learning. Fleer (Citation2020) and Vartiainen, Leinonen, and Nissinen (Citation2019) describe projects where the teachers encouraged the children to observe and discover their surroundings by using tablets, digital microscopes and trail cameras, as well as to engage in collaborative meaning-making with their peers. The digital microscope enabled the children to look closely at soil samples from the compost bin and water samples from their outdoor play area (Fleer Citation2020), while the trail camera enabled the children to capture images of the wildlife in the local forest (Vartiainen, Leinonen, and Nissinen Citation2019). Through the use of digital technology, the teachers empowered the children to be actors in their inquiry by giving them time and room to explore (Fleer Citation2020; Vartiainen, Leinonen, and Nissinen Citation2019). In these studies, the children were learning with the technology.

In Johnston’s (Citation2019) study, however, the technology was used to support co-learning about a topic that was new and unfamiliar for both the teachers and the children. This study can be described as an example of learning from technology, in which the technology provided important information in terms of scientific concepts and enabled the teachers’ and children’s inquiry skills to be fostered (Johnston Citation2019).

Learning to use technology

During my search for previous research, I also found two articles focusing on how children learn to use digital technology (Bird and Edwards Citation2015; Edwards and Bird Citation2017). In these articles, a movement from epistemic play to ludic play with digital technology is described. In the children’s epistemic play, the researchers saw exploration, problem solving and skill acquisition, such as framing images when using the camera or tapping on the iPad screen. Ludic behaviours were more strongly associated with using technology in symbolic play, such as creating pretend play scenarios and then using the technology to record the play, for example, recording a puppet show or a movie with Lego cars with an iPad. According to Bird and Edwards, the children’s initial activities with the technology can be understood as ‘exploratory’ when the children are learning the functions. Then, when they ‘master’ the functions, the activities change into ludic or ‘true’ play, and the activities become ‘innovative’ (Bird and Edwards Citation2015; Edwards and Bird Citation2017). This shows that it is important for children to learn to use a tool before they can use it creatively. Instead of limiting imaginative play, digital technology can be seen as supporting children’s achievement and engagement in complex activities (Bird and Edwards Citation2015; Edwards and Bird Citation2017; Yelland Citation2017).

Children as creators

Seven of the reviewed studies focus on digital technology used in creation processes (Fleer Citation2020; Hatzigianni et al. Citation2020; Leinonen and Sintonen Citation2014; Skantz Åberg, Lantz-Andersson, and Pramling Citation2014, 2015; Undheim Citation2020; Undheim and Jernes Citation2020). In all these studies, the children are positioned as the creators of products that they can share with others; the children shift from being ‘consumers’ of digital technology to being ‘producers’. In Fleer’s (Citation2020) study, the making of an animation seemed to generate the need for the children to be simultaneously inside the narrative as the actors and outside the narrative as the audience. The idea of being part of an audience placed a new type of demand on the children, which Fleer describes as ‘psychological characteristics of digital play’ (Fleer Citation2020, 7). In Hatzigianni et al.’s (2020) study, the children even positioned themselves as future designers, innovators, engineers and scientists.

In one study, the technology provided the story-creation process with new possibilities, such as editing, photographing, recording sound, and creating animations (Undheim Citation2020). In another study, the technology seemed to limit the children in their digital story-making activities; much effort was directed at operating the technology and conventions of writing to perform the task given by the teacher (Skantz Åberg, Lantz-Andersson, and Pramling Citation2014). However, as I have pointed out earlier, it is difficult to know if this is related to the technology itself, to how the technology is used, to the task given to the children by their teacher, or maybe even to a combination of all these factors.

Discussion

Through an inductive thematic analysis of the empirical studies, five key perspectives emerge, themes that in various ways are concerned with the ‘state-of-the-actual’ by focusing on children’s and teachers’ collaborative and active engagement with digital technology in ECEC (Selwyn Citation2010): 1) digital play is real play; 2) disconnected contexts; 3) teachers’ knowledge and beliefs; 4) learning with and from technology; and 5) children as creators.

On the one hand, the reviewed studies show various ways in which digital technology can open up new possibilities for children (e.g. Fleer Citation2020; Hatzigianni et al. Citation2020; Kewalramani et al. Citation2020; Vartiainen, Leinonen, and Nissinen Citation2019; Yelland Citation2018). On the other hand, the studies also highlight multiple concerns regarding the suitability of digital technology for young children (e.g. Aldhafeeri, Palaiologou, and Folorunsho Citation2016; Vidal-Hall, Flewitt, and Wyse Citation2020). However, the suitability depends on how the technology is used in the pedagogical practice, in which teachers play a significant role (e.g. Bourbour and Masoumi Citation2017; Hoel and Jernes Citation2020; Jernes and Engelsen Citation2012). Teachers’ role is an aspect also discussed and highlighted previously by several researchers (e.g. Belo et al. Citation2016; Gibbons Citation2010; Selwyn Citation2010; Stephen and Edwards Citation2018; Stephen and Plowman Citation2003). Nevertheless, several of the reviewed studies highlight the need for more professional learning opportunities for teachers to support a broader understanding of children’s experiences with technology (e.g. Aubrey and Dahl Citation2014; Jack and Higgins Citation2019; Vidal-Hall, Flewitt, and Wyse Citation2020).

Young children’s contemporary play practices are characterised as a mixture of overlapping ‘real’ and digital play practices, in which non-digital and digital toys and tools are combined in various ways in their play (e.g. Edwards et al. Citation2020; Fleer Citation2019, 2020; Lafton Citation2019). Hence, it has become almost impossible to make a distinction between ‘real’ play and digital play (Edwards et al. Citation2020). Despite this, several researchers point to a disconnect between children’s home contexts and ECEC in relation to digital technology (e.g. Aldhafeeri, Palaiologou, and Folorunsho Citation2016; Alvestad et al. Citation2017; Aubrey and Dahl Citation2014). Research shows that teachers’ knowledge and beliefs about digital technology in ECEC influence how it is implemented and embedded in the pedagogical practice (Edwards et al. Citation2020; Vidal-Hall, Flewitt, and Wyse Citation2020). Several researchers call for a need to review and challenge the traditional ideology of play-based pedagogy (e.g. Edwards Citation2013; Edwards et al. Citation2020; Palaiologou Citation2016). It seems like a narrow definition of digital technology only as screens has created a gap between ‘real’ play and digital play. However, the empirical research presented in this literature review demonstrates that the use of digital technology in ECEC is not the same as sitting quietly in front of a screen (e.g. Edwards et al. Citation2020; Fleer Citation2020; Hatzigianni et al. Citation2020; Kewalramani et al. Citation2020; Undheim and Jernes Citation2020; Vartiainen, Leinonen, and Nissinen Citation2019). Through play, exploration, inquiry activities and creation processes, children and teachers collaboratively use digital technology in various ways. By drawing on these findings, I want to highlight the importance of defining digital technology in a broad way, which means including various kinds of digital technology, including children’s imaginary technology, in the definition. Further, I want to emphasise a play-based and child-centred practice where the teachers have knowledge of and acknowledge the children’s varying experiences with digital technology but, at the same time, provide proximal support and guidance when children explore, create, play and learn with the technology (e.g. Gibbons Citation2010; Jernes and Engelsen Citation2012; Mantilla and Edwards Citation2019; Stephen and Edwards Citation2018; Stephen and Plowman Citation2003).

Conclusion

Drawing on the findings from this literature review of young children’s (age 0–6 years) and teachers’ engagement with digital technology in ECEC, I call for more research focusing on how the technology is used by teachers and children together in their everyday life in ECEC, especially research drawing on children’s views, including the youngest children; for example, research focusing on social interactions as they unfold to capture moment-by-moment interactions, as suggested by Miller et al. (Citation2017). Further, in most of the reviewed studies, the researchers describe the use of technology in a positive way; hence, there is a need for more studies with a critical focus, to include more perspectives in the discussion.

Although the reviewed studies were conducted through a broad search in several databases, there are some limitations. First, to review previous research is essentially an act of interpretation; to ensure transparency, the inclusion and exclusion criteria as well as the analytical steps are clearly described. Second, only peer-reviewed research articles found through searches performed in October 2020 are included (), mostly from educational journals. Third, because this review uses only English and Norwegian search terms, the findings are limited to studies presented in these languages. Fourth, given the focus on children and teachers engaging together with digital technology in ECEC institutions, research articles focusing on teachers’ use of digital technology without including children and children’s use of digital technology at home are excluded. Nevertheless, this literature review highlights and discusses five key perspectives from a sample of 35 empirical peer-reviewed studies published in the last decade.

Based on the findings and the discussion in this paper, I want to present some recommendations and implications for practice and policy. First, it is important for policymakers and teachers to define digital technology in a broad way and acknowledge children’s varying experiences with digital technology. Second, even though many children are familiar to digital technology, it is important that teachers provide proximal support and guidance when children explore, create, play, and learn with the technology. Consequently, teachers need time and opportunities to reflect on and discuss how they can implement and embed digital technology into their pedagogical practice and how they can use it to support their own professional development in ECEC institutions and EC teacher education. Finally, I suggest a more explicit focus on digital technology embedded into pedagogical practice in national ECEC curricula, as well as in national guidelines for EC teacher education; such as the Norwegian Framework plan for kindergartens (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2017, 45) in which it is stated that the teachers shall ‘enable the children to explore, play, learn and create using digital forms of expression’ and ‘explore the creative and inventive use of digital tools together with the children’.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (51.4 KB)Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the researchers associated with the interdisciplinary research group Grensesnitt (Interfaces) for our valuable discussions and their constructive feedback during the process. I would also like to thank Margrethe Jernes and Trude Hoel for their valuable comments on earlier drafts. The research reported in this article was supported by the FILIORUM Centre for Research in Early Childhood Education and Care at University of Stavanger (https://www.uis.no/en/research/filiorum-centre-for-research-in-early-childhood-education-and-care).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Idunn is a Norwegian database for research articles: https://www.idunn.no

References

- Aldhafeeri, Fayiz, Ioanna Palaiologou, and Aderonke Folorunsho. 2016. “Integration of Digital Technologies Into Play-Based Pedagogy in Kuwaiti Early Childhood Education: Teachers’ Views, Attitudes and Aptitudes.” International Journal of Early Years Education 24 (3): 342–360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2016.1172477.

- Alvestad, Marit, Margrethe Jernes, Åse Dagmar Knaben, and Karin Berner. 2017. “Barns fortellinger om lek i barnehagen i en tid preget av moderne medier [Children’s Stories About Play in Kindergarten in a Time Characterised by Modern Media].” Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift 101 (01): 31–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1504-2987-2017-01-04.

- Arnott, Lorna, and Nicola Yelland. 2020. “Multimodal Lifeworlds: Pedagogies for Play Inquiries and Explorations.” Journal of Early Childhood Education Research 9 (1): 124–146. https://jecer.org/multimodal-lifeworlds-pedagogies-for-play-inquiries-and-explorations.

- Aubrey, Carol, and Sarah Dahl. 2014. “The Confidence and Competence in Information and Communication Technologies of Practitioners, Parents and Young Children in the Early Years Foundation Stage.” Early Years 34 (1): 94–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2013.792789.

- Bearman, Margareth, and Phillip Dawson. 2013. “Qualitative Synthesis and Systematic Review in Health Professions Education.” Medical Education 47: 252–260. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12092.

- Belo, Nelleke, Susan McKenney, Joke Voogt, and Barbara Bradley. 2016. “Teacher Knowledge for Using Technology to Foster Early Literacy: A Literature Review.” Computers in Human Behavior 60: 372–383. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.053.

- Bird, Jo, and Susan Edwards. 2015. “Children Learning to Use Technologies Through Play: A Digital Play Framework.” British Journal of Educational Technology 46 (6): 1149–1160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12191.

- Booth, Andrew, Anthea Sutton, and Diana Papaioannou. 2016. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Bourbour, Maryam, and Davoud Masoumi. 2017. “Practise What You Preach: The Interactive Whiteboard in Preschool Mathematics Education.” Early Child Development and Care 187 (11): 1819–1832. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2016.1192617.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Burnett, Cathy. 2010. “Technology and Literacy in Early Childhood Educational Settings: A Review of Research.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 10 (3): 247–270. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798410372154.

- Carlsen, Martin. 2013. “Mathematical Learning Opportunities in Kindergarten Through the Use of Digital Tools: Affordances and Constraints.” Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 8 (3): 171–185. 13/03/mathematical_learning_opportunities_in_kindergarten_through.

- Carlsen, Martin, Ingvald Erfjord, Per Sigurd Hundeland, and John Monaghan. 2016. “Kindergarten Teachers’ Orchestration of Mathematical Activities Afforded by Technology: Agency and Mediation.” Educational Studies in Mathematics 93 (1): 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-016-9692-9.

- Chaudron, Stephane, Rosanna Di Gioia, and Monica Gemo. 2018. Young Children (0-8) and Digital Technology: A Qualitative Study Across Europe [EUR 29070]. European Union. doi:https://doi.org/10.2760/294383.

- Danby, Susan, Marilyn Fleer, Christina Davidson, and Maria Hatzigianni. 2018. “Digital Childhoods Across Contexts and Countries.” In Digital Childhoods: Technologies and Children's Everyday Lives, edited by Susan Danby, Marilyn Fleer, Christina Davidson and Maria Hatzigianni, 1–14. Singapore: Springer.

- Dunn, Jill, Colette Gray, Pamela Moffett, and Denise Mitchell. 2018. “‘It’s More Funner Than Doing Work’: Children’s Perspectives on Using Tablet Computers in the Early Years of School.” Early Child Development and Care 188 (6): 819–831. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2016.1238824.

- Edwards, Susan. 2013. “Digital Play in the Early Years: A Contextual Response to the Problem of Integrating Technologies and Play-Based Pedagogies in the Early Childhood Curriculum.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 21 (2): 199–212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2013.789190.

- Edwards, Susan, and Jo Bird. 2017. “Observing and Assessing Young Children’s Digital Play in the Early Years: Using the Digital Play Framework.” Journal of Early Childhood Research 15 (2): 158–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X15579746.

- Edwards, Susan, Ana Mantilla, Susan Grieshaber, Joce Nuttall, and Elizabeth Wood. 2020. “Converged Play Characteristics for Early Childhood Education: Multi-Modal, Global-Local, and Traditional-Digital.” Oxford Review of Education 46 (5): 637–660. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1750358.

- Fjørtoft, Siw Olsen, Sylvi Thun, and Marte Pettersen Buvik. 2019. Monitor 2019: en deskriptiv kartlegging av digital tilstand i norske skoler og barnehager [Monitor 2019: A Descriptive Comprehensive Survey of the Digital Status of Norwegian Schools and Kindergartens]. Trondheim: Sintef. https://www.udir.no/contentassets/92b2822fa64e4759b4372d67bcc8bc61/monitor-2019-sluttrapport_sintef.pdf.

- Fleer, Marilyn. 2019. “Digitally Amplified Practices: Beyond Binaries and Towards a Profile of Multiple Digital Coadjuvants.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 26 (3): 207–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039.2019.1646289.

- Fleer, Marilyn. 2020. “Examining the Psychological Content of Digital Play Through Hedegaard’s Model of Child Development.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 26: 1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2018.04.006.

- Gibbons, Andrew Neil. 2010. “Reflections Concerning Technology: A Case for the Philosophy of Technology in Early Childhood Teacher Education and Professional Development Programs.” In Technology for Early Childhood Education and Socialization: Developmental Applications and Methodologies, edited by Satomi Izumi-Taylor and Sally Blake, 1–19. Hershey: IGI Global.

- Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. 2009. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information and Libraries Journal 26 (2): 91–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

- Hatzigianni, Maria, Michael Stevenson, Matt Bower, Garry Falloon, and Anne Forbes. 2020. “Children’s Views on Making and Designing.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 28 (2): 286–300. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2020.1735747.

- Hoel, Trude, and Margrethe Jernes. 2020. “Samtalebasert lesing av bildebok-apper: barnehagelærer versus hotspoter [Dialogue-Based Reading of Picture Book Apps: The Kindergarten Teacher Versus Hotspots].” Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift 104 (2): 121–133. doi:https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1504-2987-2020-02-04.

- Holloway, Donell, Lelia Green, and Sonia Livingstone. 2013. Zero to Eight: Young Children and Their Internet Use. LSE, London: EU Kids Online. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/52630/1/Zero_to_eight.pdf.

- Hsin, Ching-Ting, Ming-Chaun Li, and Ching-Chung Tsai. 2014. “The Influence of Young Children’s Use of Technology on Their Learning: A Review.” Educational Technology & Society 17 (4): 85–99.

- Jack, Christine, and Steve Higgins. 2019. “What Is Educational Technology and How Is It Being Used to Support Teaching and Learning in the Early Years?”. International Journal of Early Years Education 27 (3): 222–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2018.1504754.

- Jernes, Margrethe, and Knut Steinar Engelsen. 2012. “Stille kamp om makten: en studie av barns interaksjon i digital kontekst i barnehagen [Quiet Struggle for Power: A Study of Children’s Interactions in a Digital Kindergarten Context].” Nordic Studies in Education 32 (3-4): 281–296. http://www.idunn.no/ts/np/2012/03-04/stille_kamp_ommakten_-_en_studie_av_barns_interaksjon_i_di.

- Johnston, Kelly. 2019. “Digital Technology as a Tool to Support Children and Educators as Co-Learners.” Global Studies of Childhood 9 (4): 306–317. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2043610619871571.

- Johnston, Kelly, Fay Hadley, and Manjula Waniganayake. 2020. “Practitioner Inquiry as a Professional Learning Strategy to Support Technology Integration in Early Learning Centres: Building Understanding Through Rogoff’s Planes of Analysis.” Professional Development in Education 46 (1): 49–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2019.1647871.

- Johnston, Kelly, Kate Highfield, and Fay Hadley. 2018. “Supporting Young Children as Digital Citizens: The Importance of Shared Understandings of Technology to Support Integration in Play-Based Learning.” British Journal of Educational Technology 49 (5): 896–910. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12664.

- Kewalramani, Sarika, Ioanna Palaiologou, Lorna Arnott, and Maria Dardanou. 2020. “The Integration of the Internet of Toys in Early Childhood Education: A Platform for Multi-Layered Interactions.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 28 (2): 197–213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2020.1735738.

- Kucirkova, Natalia, Deborah Wells Rowe, Lucy Oliver, and Laura E. Piestrzynski. 2019. “Systematic Review of Young Children’s Writing on Screen: What Do We Know and What Do We Need to Know.” Literacy 53 (4): 216–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12173.

- Lafton, Tove. 2019. “Becoming Clowns: How Do Digital Technologies Contribute to Young Children’s Play?”. Contemporary Issues In Early Childhood (July 2019): 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949119864207.

- Leinonen, Jonna, and Sara Sintonen. 2014. “Productive Participation – Children as Active Media Producers in Kindergarten.” Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 9 (3): 216–236. https://www.idunn.no/file/pdf/66722073/productive_participation_-_children_as_active_media_produce.pdf.

- Ling, Li, Nicola Yelland, Maria Hatzigianni, and Camille Dickson-Deane. 2021. “Toward a Conceptualization of the Internet of Toys.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/18369391211007327.

- Ljunggren, Åsa. 2016. “Multilingual Affordances in a Swedish Preschool: An Action Research Project.” Early Childhood Education Journal 44 (6): 605–612. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0749-7.

- Mantilla, Ana, and Susan Edwards. 2019. “Digital Technology Use by and with Young Children: A Systematic Review for the Statement on Young Children and Digital Technologies.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 44 (2): 182–195. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1836939119832744.

- McGlynn-Stewart, Monica, Leah Brathwaite, Lisa Hobman, Nicola Maguire, and Emma Mogyorodi. 2018. “Open-Ended Apps in Kindergarten: Identity Exploration Through Digital Role-Play.” Language and Literacy 20 (4): 40–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.20360/langandlit29439.

- McGlynn-Stewart, Monica, Leah Brathwaite, Lisa Hobman, Nicola Maguire, Emma Mogyorodi, and Yeh Uhn Park. 2017. “Inclusive Teaching with Digital Technology: Supporting Literacy Learning in Play-Based Kindergartens.” LEARNing Landscapes 11 (1): 199–216. doi:https://doi.org/10.36510/learnland.v11i1.932.

- Miller, Jennifer L., Kathleen A. Paciga, Susan Danby, Leanne Beaudoin-Ryan, and Tamara Kaldor. 2017. “Looking Beyond Swiping and Tapping: Review of Design and Methodologies for Researching Young Children’s Use of Digital Technologies.” Cyberpsychology 11 (3). doi:https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2017-3-6.

- Moher, David, Alessandro Liberati, Jennifer Tetzlaff, Douglas G. Altman, and The PRISMA Group. 2009. “Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement.” PLoS Medicine 6 (7): 1–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. 2017. Framework Plan for Kindergartens. https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/barnehage/rammeplan/framework-plan-for-kindergartens2-2017.pdf.

- Palaiologou, Ioanna. 2016. “Teachers’ Dispositions Towards the Role of Digital Devices in Play-Based Pedagogy in Early Childhood Education.” Early Years 36 (3): 305–321. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2016.1174816.

- Plowman, Lydia, and Christine Stephen. 2003. “A ‘Benign Addition’? Research on ICT and Pre-School Children.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 19 (2): 149–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0266-4909.2003.00016.x.

- Robinson, Ken. 2011. Out of Our Minds: Learning to Be Creative. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Capstone.

- Sandvik, Margareth, Ole Smørdal, and Svein Østerud. 2012. “Exploring IPads in Practitioners’ Repertoires for Language Learning and Literacy Practices in Kindergarten.” Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 7 (03): 204–221. https://www.idunn.no/dk/2012/03/exploring_ipads_in_practitioners_repertoires_for_language_.

- Selwyn, Neil. 2010. “Looking Beyond Learning: Notes Towards the Critical Study of Educational Technology.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 26 (1): 65–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2009.00338.x.

- Skantz Åberg, Ewa, Annika Lantz-Andersson, and Niklas Pramling. 2014. “‘Once Upon a Time There Was a Mouse’: Children’s Technology-Mediated Storytelling in Preschool Class.” Early Child Development and Care 184 (11): 1583–1598. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2013.867342.

- Skantz Åberg, Ewa, Annika Lantz-Andersson, and Niklas Pramling. 2015. “Children’s Digital Storymaking: The Negotiated Nature of Instructional Literacy Events.” Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 10 (3): 170–189. https://www.idunn.no/file/pdf/66804637/childrens_digital_storymaking_-_the_negotiated_nature_of_i.pdf.

- Stephen, Christine, and Susan Edwards. 2018. Young Children Playing and Learning in a Digital Age: A Cultural and Critical Perspective. London: Routledge.

- Stephen, Christine, and Lydia Plowman. 2003. “Information and Communication Technologies in Pre-School Settings: A Review of the Literature.” International Journal of Early Years Education 11 (3): 223–234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966976032000147343.

- Sulaymani, Omar, Marilyn Fleer, and Denise Chapman. 2018. “Understanding Children’s Motives When Using IPads in Saudi Classrooms: Is It for Play or for Learning?”. International Journal of Early Years Education 26 (4): 340–353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2018.1454303.

- Undheim, Marianne. 2020. “‘We Need Sound Too!’ Children and Teachers Creating Multimodal Digital Stories Together.” Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy 15 (3): 165–177. doi:https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1891-943x-2020-03-03.

- Undheim, Marianne, and Margrethe Jernes. 2020. “Teachers’ Pedagogical Strategies When Creating Digital Stories with Young Children.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 28 (2): 256–271. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2020.1735743.

- United Nations. 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx.

- Vartiainen, Henriikka, Teemu Leinonen, and Saara Nissinen. 2019. “Connected Learning with Media Tools in Kindergarten: An Illustrative Case.” Educational Media International 56 (3): 233–249. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2019.1669877.

- Vidal-Hall, Charlotte, Rosie Flewitt, and Dominic Wyse. 2020. “Early Childhood Practitioner Beliefs About Digital Media: Integrating Technology Into a Child-Centred Classroom Environment.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 28 (2): 167–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2020.1735727.

- Yelland, Nicola. 2017. “Teaching and Learning with Tablets: A Case Study of Twenty-First-Century Skills and New Learning.” In Apps, Technology and Younger Learners: International Evidence for Teaching, edited by Natalia Kucirkova and Garry Falloon, 57–72. London: Routledge.

- Yelland, Nicola. 2018. “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Young Children and Multimodal Learning with Tablets.” British Journal of Educational Technology 49 (5): 847–858. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12635.

- Yelland, Nicola, and Jennifer Masters. 2007. “Rethinking Scaffolding in the Information Age.” Computers & Education 48 (3): 362–382. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2005.01.010.