ABSTRACT

This study investigated the concept, role and potential of intergenerational learning (IGL) as a pedagogical strategy in five Irish early childhood education (ECE) services, through exploring the perspectives on IGL of educators (5), children (70) and their parents (43). Informed by socio-cultural theories of learning and aligned to key principles of IGL, a qualitative methodological approach was adopted. Data was gathered using semi-structured interviews with educators, ‘draw and talk’ strategies with children and informal written feedback with parents. Key findings demonstrated that children’s happiness, socio-emotional competences and executive functions, all key elements of successful learning and living, were strongly supported through IGL, reinforcing its potential as a relational pedagogy (Papatheodorou, T., and J. Moyles. 2009. Learning Together in the Early Years: Exploring Relational Pedagogy. London: Routledge.). Additionally, IGL created rich opportunities for children’s participation and contribution as citizens in communities, underscoring the potential of IGL as a strong and transformative pedagogical strategy (Sánchez, M., J. Sáez, P. Díaz, and M. Campillo. 2018. “Intergenerational Education in Spanish Primary Schools: Making the Policy Case.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 16 (1-2): 166–183.) for Irish ECE services.

Introduction

The concept of intergenerational learning (IGL) is as old as humankind, predating any type of formal education and typically involving the informal transmission of knowledge, skills and values in multigenerational families as part of daily living (Jessel Citation2009; Watts Citation2017). The introduction of formal schooling and the separation of family life and work life led to the decline of this traditional form of IGL. Over time, ideas about learning and education adapted to these changes until learning, at least in the public arena, began to be associated with formal educational institutions and only for children and young people (Hager and Halliday Citation2007). It was not until the late twentieth century that interest in planned, extra-familial intergenerational practice emerged (Bottery Citation2016), broadly understood as ‘the way people of all ages can learn together and from each other’ (ENIL Citation2012, 4). Planned, extra-familial IGL builds on key elements of traditional forms of IGL, particularly the importance of relationships and informal contexts of everyday life for learning and the contributions of wide-ranging social groups outside the family to the learning and development of children and adults (Kaplan Citation2002; Sánchez et al. Citation2018). The main agents of planned IGL are people who are not trained, paid or acknowledged as teachers (Boström Citation2003) and the learning space is the place where those people interact, typically through informal encounters in local communities (ENIL Citation2012). IGL places equal emphasis on learning together, learning from each other and learning about each other in real life contexts (Schmidt-Hertha, Krašovec, and Formosa Citation2014). Importantly, in the process IGL creates possibilities for increased solidarity between generations, as well as mutual enrichment and benefits to individuals and communities (Cabanillas Citation2011; Newman and Hatton-Yeo Citation2008; UNESCO Citation2000).

However, despite the emphasis in IGL on learning, the primary focus of IGL policy and practice since its emergence in the late twentieth century has been on its potential to address societal changes and challenges (TOY Citation2013). These include ageing populations, increasing segregation of generations due to urbanisation, migration and family change, social isolation and, to a lesser extent, individuals’ right to lifelong learning (Cortellesi and Kernan Citation2016; Kaplan et al. Citation2020).

More recently, a growing interest internationally in IGL as a pedagogical strategy has begun to emerge (Sánchez et al. Citation2018), with some agreement in the literature that IGL as a learning approach includes the following key ideas: it facilitates socially-constructed learning through collaborative relationships in authentic cultural contexts; it promotes positive views of the strong capacity of people of all ages to participate in their own learning; it mobilises the resources of the community to enrich the learning of young and old and it operationalises principles of lifelong and lifewide learning (Hatton-Yeo Citation2015; Jarrott and Smith Citation2011; Kaplan and Sánchez Citation2014; Kump and Krašovec Citation2014; Sánchez et al. Citation2018; VanderVen Citation2011).

Crucially, in this study, these understandings of IGL bring to life key concepts of contemporary thinking on young children’s learning and development. These concepts are encapsulated in Bruner’s (Citation1996, 84) broad definition of human learning as ‘participatory, proactive, communal, collaborative and given over to constructing meanings rather than receiving them’. More recently, key principles of a quality framework for ECE services proposed by the European Commission strongly resonate with IGL policy and practice. The framework foregrounds ideas of the child as co-creator of knowledge with people of all ages, as well as the importance of providing a social, cultural and physical space in preparing children for life and citizenship in society (European Commission, Citation2014). The importance of socio-emotional learning and the role ECE services play in supporting individuals to learn to live together in heterogeneous societies further resonate with IGL principles and with recommendations for high quality ECE systems (European Council Citation2019).

However, IGL is neither reflected in well-regarded ECE curricula internationally, nor in Irish curricular and quality frameworks (CECDE Citation2006; NCCA Citation2009), despite its common aspirations with ECE. This raises the question if, and how, IGL could extend and enrich learning opportunities and add value to the traditional pedagogical strategies offered in ECE services (Cartmel et al. Citation2018; McAlister, Briner, and Maggi Citation2019). Importantly, IGL offers the possibility of developing educational spaces that are broader and more inclusive than those currently available, capitalising on the life experiences and richness of mixed age groups in community spaces in the process of which, IGL could be reframed as a potential new model in education (Cabanillas Citation2011).

This study (Fitzpatrick Citation2021) grew out of the researcher’s participation in a larger European study of IGL forming part of the Together Old and Young (TOY) project. The TOY project consortium comprised members from seven EU countries, who undertook research on IGL policy and practice between young children and older adults (2012-2014) and delivered a pilot online training course for those involved in IGL (2016-2018) www.toyproject.net.

Specific research questions addressed in this article are: What are the views of childhood and learning among a sample of educators undertaking IGL in Irish ECE services? What are the educators’ experiences and views of IGL undertaken in their ECE services? The full study reporting on children’s and parents’ perspectives as well as the IGL implementation process, including interactions between children and older adults can be accessed at https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc/106.

Theoretical framework

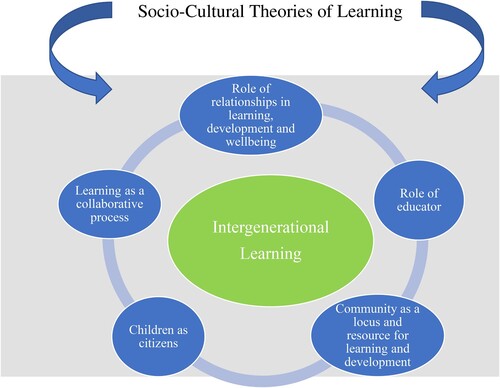

Socio-cultural theories of learning, which contend that development and learning are embedded in the context of social relationships in children’s social and cultural contexts (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979; Rogoff Citation1990), served as the theoretical framework for the study. Socio-cultural theories of learning are strongly reflected in contemporary ECE pedagogy, both in Irish (NCCA Citation2009) and international (European Commission, Citation2014) contexts. Drawing on the social constructionist understanding of learning and development, the concepts deemed most useful in exploring the research questions included: the central role of relationships in learning and development; learning as a participatory, collaborative process (Lave and Wenger Citation1991; Rogoff Citation2003); the key role of the educator in supporting children’s learning (Smith Citation1996); the community as a locus for learning and development (Nimmo Citation2008; Rogoff Citation2003) and children as active, agentic citizens in all aspects of their lives and learning (Alanen Citation2014) (see on page 4). These concepts resonate powerfully with key characteristics of IGL outlined above (Cartmel et al. Citation2018; Sánchez et al. Citation2018).

Methodology

A qualitative research design was adopted, reflecting the social constructionist paradigm in which the study was positioned. This facilitated a focus on the unique insider perspectives of the adult and child participants, giving them voice and encouraging reflection as they attributed meaning to their experiences (Lapan, Quartaroli, and Riemer Citation2012). A collaborative approach to data-gathering with children was a key element of the research design and contributed significantly to the authenticity of the study. The researcher collaborated with educators to agree guidelines that directed the data-gathering process with children, following which educators gathered data with children over time in their natural environments without the researcher being present in the ECE service. All the educators participating in the study regularly engaged in co-constructing knowledge with children and were experienced in listening to, clarifying, interpreting and documenting children’s views and experiences.

The study sample comprised five educators who had completed the TOY pilot training programme and were implementing IGL in their ECE services, 70 children (aged 3 - 5 years) attending those services and 43 parents of those children.

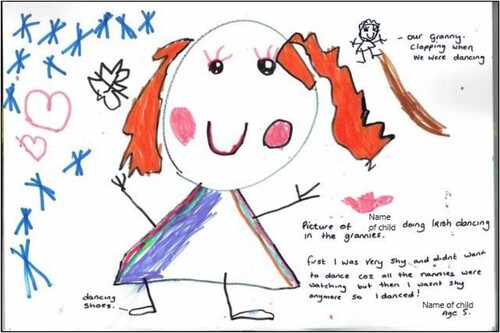

Data was collected over a nine-month period in 2019, beginning with two semi-structured interviews with educators. The first interview focused on educators’ constructions of childhood, their views on learning and the role of the ECE service. The second interview focused specifically on educators’ views and experiences of IGL and was carried out 4–5 months later to maximise educators’ experiences of IGL. This was followed by data-gathering with children and parents over a 4-month period. Data was gathered from parents through informal written feedback. Two main strategies were used to gather data with children: ‘draw and talk’ (Clark Citation2017; Einarsdottir, Dockett, and Perry Citation2009; Lipponen et al. Citation2016) and ‘talking and listening’ (Broström Citation2012; Clark and Moss Citation2011), both of which were already being used by children and educators in all the ECE services. Educators documented and collated children’s drawings, conversations and observations in notebooks provided by the researcher, an example of which can be seen in :

… our granny clapping when we were dancing … first I was shy and didn't want to dance coz all the nannies were watching but then I wasn't shy anymore, so I danced … (Child A, aged 5).

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval granted by Technological University Dublin Ethics Committee. https://www.tudublin.ie/media/website/research/postgraduate-research/graduate-research-school/documents/TU-Dublin-Code-of-Conduct-for-Research.pdf combined with the ethical framework of the Irish government for undertaking research with children (DCYA Citation2012) informed decision-making throughout the study.

Limitations of study

The study has limitations in terms of generalisation and scope. As the research involved a small, self-selected, motivated and highly-trained sample of educators who had completed IGL training and had chosen to introduce IGL in their ECE service, a relatively positive view of IGL might have been expected. Additionally, the study presents a snapshot of IGL in a relatively short timeframe and therefore does not reflect how perspectives on the IGL experiences may change positively or negatively for all participants over time. Importantly, the views of the older adults, who are key stakeholders in IGL, were not a focus of this study.

Overview of IGL experiences undertaken in the ECE services

Each of the five ECE services had developed IGL experiences with services for older adults (generally serving adults 65 years+), including nursing homes (care homes), day-care services and independent living centres, resulting in children interacting with adults of varied ages, abilities and life experiences from backgrounds that were diverse socially, culturally and geographically. A wide range of IGL experiences were implemented, with conversation, music, singing, arts and crafts, and eating together being the most frequently cited. The regularity of children’s IGL experiences ranged from weekly, fortnightly, monthly to once or twice per school term.

Key findings and discussion

IGL relationships play a positive role in children’s wellbeing and learning

A main study finding was the educative value of the individualised, attuned, and affectionate relationships that developed between children and older adults and this was identified by all educators to be central to the value of the IGL experiences for children. The nurturing relationships were deemed important by educators for the significant role they played in supporting all aspects of children’s wellbeing and learning. Significantly, these nurturing relationships resonated with the crucial role that responsive relationships play in the development of proximal processes (Bronfenbrenner and Evans Citation2000; Tudge et al. Citation2021) and executive functions (Whitebread and Coltman Citation2011) in children’s holistic development. Educators identified children feeling loved and cared for in their engagement with older adults as a core strength of IGL, reflecting educators’ belief in the inextricable link between children’s emotional, social and cognitive development in what could be termed a nurturing or relational pedagogy (Hayes Citation2013; Papatheodorou and Moyles Citation2009):

… [for children in the service] to be happy … that is one of the most important things … (Educator E).

… everybody is happy to see each other … they [the children] sit on their [older adults’] laps, there’s high fives given, there’s hugs given … so definitely there’s a lovely relationship between them … (Educator C).

… the learning takes place because of the engagement between children and older adults … because the activity … we could do it here [in the ECE service] … definitely it’s the engagement … (Educator E).

… it’s organic and it’s just more natural and mutual … it’s not a directed kind of learning … (Educator E).

… I think if you try to over orchestrate it or direct it, you’ll stifle it … for learning to happen it has to be a little bit free … the older people they’re not here to be in a role of teaching … it’s about allowing it to evolve … just through the interactions … and I think that’s really the best way … (Educator D).

… when we drive past the nursing home, she [child] tells whoever is in the car about visiting the old people … ‘it’s my nursing home’ … (Parent A).

… they [older adults] like playing with me … (Child E).

… they [children] know how to deal with people who may have had a stroke and have a speech problem … and they know to listen a little bit carefully … (Educator C).

… somebody [older adult] said something about ‘during the war’ so the children were asking [about the war] … we wouldn’t really talk about that in Montessori … and that emerged in our curriculum because the next day they wanted to know about the war … (Educator C).

… one of the residents said ‘oh, I need to go to the toilet’ to the nurse and one of the children said … ‘does she have to ask to go to the toilet?’ … so I had to explain … ‘well, actually she finds it difficult to walk to the toilet so she needs a bit of help’ … (Educator E).

… one of the ladies when she holds the children’s hands … she won’t let go … so the children are giving her a wave instead of holding her hand, or they'll know that if they do hold hands that they can call one of us to come over and help the situation … (Educator E).

The real-life contexts afforded by the IGL experiences were also valued by educators as opportunities for authentic collaborative learning, with children taking on the roles of both learners and teachers, reflecting Rogoff’s (Citation2014) ideas of ‘learning by observing and pitching in’ to community activities:

… making the rice crispies [cakes] … we [educators] actually completely stepped away as childcare practitioners and let the children and the older people manage … opening the packets … one holding the bowl … the bingo game … having to match, listen, ask someone else ‘did you hear that?’ … those kinds of things are very important … (Educator R).

IGL as a vehicle to enhance children’s participation in communities

The strength of IGL as a vehicle for enhancing children’s participation as citizens in communities was a key study finding. Importantly, educators firmly believed that children were fully-fledged citizens with a right to participate not only within but also beyond the ECE service, and that educators should act as brokers in promoting children’s participation in the community. In supporting children’s participation and right to be embedded in the community (Bessell Citation2017; Fleer Citation2003) through IGL, educators emphasised two key features: the usefulness of adopting a relational perspective on participation in the context of young children’s lives and the crucial importance of children’s social contexts in affecting their participation:

… there is no point in putting them in this little place [the ECE service] and wrapping them in bubble wrap when the world is bigger than just here … (Educator M).

… nobody ever thinks of offering [children] one [a role in the community] … (Educator D).

… they are interested in being involved in the community because … they are now telling us what they want to do … (Educator C).

Educators highlighted how non-judgemental and caring children were in supporting older adults in practical ways such as listening carefully, helping them physically and sometimes anticipating their needs. The meaningful social roles created through the IGL experiences enhanced children’s views of themselves as active, contributing citizens (Hart Citation1997), contributors of social capital to the community, while also promoting positive views of the competence of children in the wider community (Nimmo Citation2008):

… they [children] help residents into their seats … [or] go over to them and say, ‘do you want to link my arm?’ … and they’ll walk with the walker with them … (Educator C).

… they [children] don't make assumptions … they just accept everybody for who they are … they just think … ‘my friend’ … that is it … it doesn't matter how old the friend is … (Educator M).

… they are the future people who are going to do the Tidy TownsFootnote2, do the Meals on WheelsFootnote3 … if we don't do it at this young age, it is not going to happen … (Educator C).

The educator as intentional teacher

The pivotal role of the educators and their autonomy in decisions around what and how they provided for the optimal development of children in the ECE service was a central finding in the study and one that is well-established in the literature (Ang Citation2014; Campbell-Barr Citation2019; Shonkoff and Phillips Citation2000). However, the impact of educators’ values and orientation on children’s learning and wellbeing are rarely perceived as legitimate contexts for critical reflection within ECE curricula (Ang Citation2014) or identified as issues for research (Anders Citation2015; Campbell-Barr Citation2019).

In this study, the importance of children’s happiness through feeling loved and cared for, children contributing to the lives of others and the richness of community life as a learning environment were values shared by educators and were instrumental in their decision to intentionally implement IGL. This finding, that educators’ explicit and implicit socio-cultural beliefs and understandings of children and learning, impacted powerfully in guiding their work (Freire Citation1972), resonating with what Ang (Citation2014, 194) refers to as the ‘unofficial curriculum’.

The happiness which the IGL relationships brought to children was a driving force in educators’ decision to adopt IGL as a pedagogical strategy. In calling attention to children’s happiness, educators addressed not only the relationship between children’s emotional security and their development as powerful learners, but also highlighted a contemporary debate on the nature of professionalism: balancing the requirements of policy and regulation with the affective and emotional elements of work with children (Osgood Citation2010).

Educators’ commitment to the right and desire of children to be valued in communities was also a motivating factor in introducing IGL, perceived by educators to be an effective vehicle for extending children’s participation beyond the ECE service. Importantly, it reflects educators’ belief in the role of the community in supporting children’s flourishing (Boyd Citation2019; Nimmo Citation2008):

… I think they do [want to play a role in their community] … I think they like having that bit of responsibility … they like being part of the community … (Educator M).

… children can give too … they’re like a burst of energy to the older people … and you could see that from the older people just being so amazed about how great they are … (Educator D).

… this time last year I never would have thought of a crèche visiting a day centre or a nursing home … why would you do such a thing … and now I’m asking ‘why would you not do such a thing?’ … (Educator R).

… I would have been up for going out on walks and things like that … but letting other people engage with the children … for other people to take on that role as well … I think this is possibly the first time that we’ve done it on this kind of scale … (Educator E).

… it is us having to go out into the community … to see what we can find for them to do … we come in with ideas and they [the children] start throwing out ideas and we start circling what they want to do … (Educator C).

The overwhelmingly positive views of parents in relation to IGL, a key finding of the study, was in some considerable measure due to the educators’ enthusiasm and expertise in introducing and implementing IGL. Educators anticipated and addressed potential parental concerns, which included acknowledging the tension between parents prioritising academic skills over educators’ emphasis on the value of positive social and emotional development; child safeguarding issues and how children with additional needs might experience IGL:

… some of our parents really wanted the children to do academic learning … we did focus groups with them … asked them to look at Aistear [curriculum framework] … then we tracked them [the children] for a few months and then asked them [parents] to look at it again … and they realised that … they’re learning so much … it doesn’t have to be academic … (Educator R).

… maybe they [parents] had concerns about where [the children] were going to be … were they going to be in the [bed]rooms or was it going to be an open room … they know we’re taking them from one safe environment to another … (Educator M).

… two children I brought down on their own [as part of the preparation], they had autism … I felt that was important because of the smells, the sounds … (Educator M).

Conclusion

Considering IGL as a pedagogical strategy raises important philosophical questions in imagining learning priorities for young children now and into the future, which may involve extending or challenging contemporary ideas of ECE practice. A humanistic rather than instrumental view of education, reflected in the lifeskills and potentialities evident in the study children’s interactions with the older adults, demonstrated educators’ commitment to relational pedagogy with a focus on future-building rather than future-proofing. Future-building, which challenges the dominating discourse in ECE in the Western world, in what Facer (Citation2019) refers to as the defensive position of future-proofing children, searches for possibilities in the present by questioning what we might desire for an unknown future, arguing that education is a site for future visions (Moss Citation2017).

This perspective understands education in the broadest sense as fostering children’s development and wellbeing and their ability to live a good life, with the goal that both the individual and society will flourish, embracing what could be considered a fundamental aspiration of education: to be transformative and lead to profound change for individuals and communities (Cabanillas Citation2011; Delors Citation1996; Freire Citation1972; Sanchez et al, 2018).

Importantly, IGL created opportunities for the community to contribute to the development and wellbeing of children. Through this reciprocal process, IGL created opportunities to address societal challenges, including age segregation, social isolation and lifelong learning. In opening up the spaces, physically and metaphorically, as inclusive places of encounter where children and older adults spend much time, extensive opportunities were accessed for the development of solidarity and sustainable communities. Moreover, doing so facilitated the valuable contribution ECE services can make to the realisation of the UN Sustainable Goals, including quality education and sustainable communities and cities (UN Citation2015). Opening up the ECE service and reimagining its role through the practice of IGL benefitted children, older adults and communities, while also empowering educators, parents and families. IGL strengthened relationships between educators and parents and created opportunities for the development of social capital enhancing social cohesion (Watts Citation2017) as parents became involved in IGL and/or other community experiences. Nonetheless however, and building on the results of this exploratory study, consideration should be given to possible negative aspects of IGL by conducting research on the implementation of IGL in a broader sample of ECE services over time.

Overall, this study highlights the value of IGL as a pedagogical strategy which draws on community spaces as rich and innovative learning environments, demonstrating how IGL offers a contemporary take on a long-established belief that it takes a village to raise a child.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Older people contributing their skills and life wisdom to younger generations to whom they are not related (Gallagher and Fitzpatrick Citation2018).

2 Tidy Towns is a national, annual competition encouraging communities to enhance their local environment.

3 A home delivery service of meals by volunteers to support individuals, usually older adults, to live independently.

References

- Alanen, L. 2014. “Theorizing Childhood.” Childhood 21 (1): 3–6.

- Anders, Y. 2015. Literature Review on Pedagogy. OECD Network on Early Childhood Education and Care. EDU/EDPC/ECEC (2015)7.

- Ang, L. 2014. “Preschool or Prep School? Rethinking the Role of Early Years Education.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 15 (2): 185–199.

- Bae, B. 2010. “Realizing Children's Right to Participation in Early Childhood Settings: Some Critical Issues in a Norwegian Context.” Early Years 30 (3): 205–218.

- Bessell, S. 2017. “The Role of Intergenerational Relationships in Children's Experiences of Community.” Children & Society 31 (4): 263–275.

- Boström, A. 2003. Lifelong Learning, Intergenerational Learning and Social Capital - from Theory to Practice. Stockholm: Institute of International Education.

- Bottery, T. 2016. “The Future of Intergenerational Learning: Redefining the Focus?” Studia Paedagogica 21 (2): 9–24.

- Boyd, D. 2019. “Utilising Place-Based Learning Through Local Contexts to Develop Agents of Change in Early Childhood Education for Sustainability.” Education 3-13 47 (8): 983–997.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2014. “What Can “Thematic Analysis” Offer Health and Wellbeing Researchers?” International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being 9 (1).

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1985. “The Future of Childhood.” In Children: Needs and Rights, edited by V. Greaney, 167–186. New York: Irvington Publishers.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., ed. 2005. Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., and G. W. Evans. 2000. Developmental Science in the 21st Century: Emerging Questions, Theoretical Models, Research Designs and Empirical Findings.” Social Development 9 (1): 115–125.

- Bronfenbrenner, U., and P. Morris. 1998. “The Ecology of Developmental Processes.” In Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical Models of Human Development, edited by W. Damon and R. M. Lerner, 993–1028. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

- Broström, S. 2012. “Children's Participation in Research.” International Journal of Early Years Education 20 (3): 257–269.

- Bruner, J. 1996. The Culture of Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Cabanillas, C. 2011. “Intergenerational Learning as an Opportunity to Generate New Educational Models.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 9 (2): 229–231.

- Campbell-Barr, V. 2019. “Professional Knowledges for Early Childhood Education and Care.” Journal of Childhood Studies 44 (1): 134–146.

- Carr, M., and W. Lee. 2012. Learning Stories: Constructing Learner Identities in Early Education. London: Sage.

- Cartmel, J., K. Radford, C. Dawson, A. Fitzgerald, and N. Vecchio. 2018. “Developing an Evidenced Based Intergenerational Pedagogy in Australia.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 16 (1-2): 64–85.

- Clark, A. 2017. Listening to Young Children: A Guide to Understanding and Using the Mosaic Approach. 3rd ed. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Clark, A., and P. Moss. 2011. Listening to Young Children: The Mosaic Approach. 2nd ed. London: National Children’s Bureau.

- Cortellesi, G., and M. Kernan. 2016. “Together Old and Young: How Informal Contact Between Young Children and Older People Can Lead to Intergenerational Solidarity.” Studia Paedagogica 21 (2): 101–116.

- [CECDE] Centre for Early Childhood Development and Education. 2006. Síolta – The National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education. Dublin: Centre for Early Childhood Development and Education.

- Dalli, C. 2008. “Pedagogy, Knowledge and Collaboration: Towards a Ground-up Perspective on Professionalism.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 16 (2): 171–185.

- Degotardi, S., J. Page, and E. J. White. 2017. “Joint Attention in Infant-Toddler Early Childhood Programs: Its Dynamics and Potential for Collaborative Learning.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 18 (4): 409–421.

- Delors, J. 1996. Learning: The Treasure Within. Report to UNESCO of the International Commission on Education for the 21st Century. Paris: UNESCO.

- Denham, S. A., and C. Brown. 2010. “‘Plays Nice With Others’: Social–Emotional Learning and Academic Success.” Early Education & Development 21 (5): 652–680.

- [DCYA] Department of Children and Youth Affairs, Ireland. 2012. Guidelines for Developing Ethical Research Projects Involving Children. Dublin: Government Publications.

- Desforges, C., and A. Abouchaar. 2011. The Impact of Parental Involvement, Parental Support and Family Education on Pupil Achievement and Adjustment: A Literature Review. [Research Report No. 433]. Department for Education and Skills, England.

- Edwards, S. 2017. “Play-based Learning and Intentional Teaching: Forever Different?” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 42 (2): 4–11.

- Einarsdottir, J., S. Dockett, and B. Perry. 2009. “Making Meaning: Children’s Perspectives Expressed Through Drawings.” Early Child Development and Care 179 (2): 217–232.

- Epstein, A. 2007. The Intentional Teacher. Choosing the Best Strategies for Young Children’s Learning. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

- Epstein, J. L., and S. B. Sheldon. 2016. “Necessary but Not Sufficient: The Role of Policy for Advancing Programs of School, Family, and Community Partnerships.” Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 2 (5): 202–219.

- European Commission. 2014. Proposal for Key Principles of a Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education and Care. Report of the Working Group on Early Childhood Education and Care under the auspices of the European Commission (Directorate-General for Education and Culture).

- European Council. 2019. Council Recommendation (2019/C 189/02) on High-quality Early Childhood Education and Care Systems.

- [ENIL] European Network for International Learning. 2012. Report on Intergenerational Learning and Volunteering. http://envejecimiento.csic.es/documentos/documentos/enil-ilv-01.pdf

- Facer, K. 2019. “Preventing the End of the Future.” In Schools of Tomorrow, edited by S. Fehrmann, 48–58. Berlin: Matthes & Seitz.

- Fattore, T., and J. Mason. 2017. “The Significance of the Social for Child Well-Being.” Children & Society 31 (4): 276–289.

- Fitzpatrick, A. 2021. “Intergenerational Learning: An Exploratory Study of the Concept, Role and Potential of Intergenerational Learning (IGL) as a Pedagogical Strategy in Irish Early Childhood Education (ECE) Services.” PhD diss., Technological University Dublin. https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc/106/

- Fleer, M. 2003. “Early Childhood Education as an Evolving ‘Community of Practice’ or as Lived ‘Social Reproduction’: Researching the ‘Taken-for-Granted’.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 4 (1): 64–79.

- Freire, P. 1972. The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Penguin.

- Gaffney, M. 2011. Flourishing. London: Penguin.

- Gallagher, C., and A. Fitzpatrick. 2018. “‘It’s a Win-Win Situation’ – Intergenerational Learning in Preschool and Elder Care Settings: An Irish Perspective.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 16 (1-2): 26–44.

- Geraghty, R., J. Gray, and D. Ralph. 2015. “‘One of the Best Members of the Family’: Continuity and Change in Young Children’s Relationships with Their Grandparents.” In The ‘Irish’ Family, edited by L. Connolly, 124–139. London: Routledge.

- Hager, P., and J. Halliday. 2007. Recovering Informal Learning: Wisdom, Judgement and Community. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Hanmore-Cawley, M., and T. Scharf. 2018. “Intergenerational Learning: Collaborations to Develop Civic Literacy in Young Children in Irish Primary School.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 16 (1-2): 104–122.

- Hart, R. A. 1997. Children’s Participation. The Theory and Practice of Involving Young Citizens in Community Development and Environmental Care. New York: UNICEF.

- Hatton-Yeo, A. 2015. “A Personal Reflection on the Definitions of Intergenerational Practice.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 13 (3): 283–284.

- Hayes, N. 2013. Early Years Practice. Getting it Right from the Start. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan.

- Hayes, N., L. O’Toole, and A. Halpenny. 2017. Introducing Bronfenbrenner – A Guide for Practitioners and Students in Early Years Education. London: Routledge.

- Hedges, H., and M. Cooper. 2018. “Relational Play-Based Pedagogy: Theorising a Core Practice in Early Childhood Education.” Teachers and Teaching 24 (4): 369–383.

- Horgan, D., C. Forde, S. Martin, and A. Parkes. 2017. “Children’s Participation: Moving from the Performative to the Social.” Children's Geographies 15 (3): 274–288.

- Jarrott, S. E., and C. L. Smith. 2011. “The Complement of Research and Theory in Practice: Contact Theory at Work in Nonfamilial Intergenerational Programs.” The Gerontologist 51 (1): 112–121.

- Jessel, J. 2009. Family Structures and Intergenerational Transfers of Learning: Changes and Challenges. London: Department of Education Studies, University of London, Goldsmith College.

- Kaplan, M. S. 2002. “Intergenerational Programs in Schools: Considerations of Form and Function.” International Review of Education/ Internationale Zeitschrift fr Erziehungswissenschaft/ Revue Inter 48 (5): 305–334.

- Kaplan, M., and M. Sánchez. 2014. “Intergenerational Programmes.” In International Handbook on Ageing and Public Policy, edited by S. Harper, and K. Hamblin (with J. Hoffman, K. Howse, & G. Leeson), 367–383. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Kaplan, M., L. L. Thang, M. Sánchez, and J. Hoffman. 2020. Intergenerational Contact Zones: Place-Based Strategies for Promoting Social Inclusion and Belonging. New York: Routledge.

- Kilderry, A. 2015. “Intentional Pedagogies: Insights from the Past.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 40 (3): 20–28.

- Kump, S., and S. J. Krašovec. 2014. “Intergenerational Learning in Different Contexts.” In Learning Across Generations in Europe: Contemporary Issues in Older Adult Education, edited by B. Schmidt-Hertha, S. J. Krašovec, and M. Formosa, 167–177. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Lapan, S. D., M. T. Quartaroli, and F. J. Riemer. 2012. Qualitative Research: An Introduction to Methods and Designs. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lipponen, L., A. Rajala, J. Hilppö, and M. Paananen. 2016. “Exploring the Foundations of Visual Methods Used in Research with Children.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 24 (6): 936–946.

- Mannion, G. 2010. “After Participation, the Socio-Cultural Performance of Intergenerational Becoming.” In A Handbook of Children and Young People’s Participation: Perspectives from Theory and Practice, edited by B. Percy-Smith and N. Thomas, 330–343. London: Routledge.

- McAlister, J., E. L. Briner, and S. Maggi. 2019. “Intergenerational Programs in Early Childhood Education: An Innovative Approach That Highlights Inclusion and Engagement with Older Adults.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 17 (4): 505–522.

- McLaughlin, T., K. Aspden, and C. McLachlan. 2015. “How do Teachers Build Strong Relationships? A Study of Teaching Practices to Support Child Learning and Social–Emotional Competence.” Early Childhood Folio 19 (1): 31–38.

- Mentha, S., A. Church, and J. Page. 2015. “Teachers as Brokers.” The International Journal of Children’s Rights 23 (3): 622–637.

- Moss, P. 2009. There are Alternatives! Markets and Democratic Experimentalism in Early Childhood Education and Care. Working Papers in Early Childhood Development: Number 53. The Hague: Bernard van Leer Foundation.

- Moss, P. 2014. Transformative Change and Real Utopias in Early Childhood Education: A Story of Democracy, Experimentation and Potentiality. London: Routledge.

- Moss, P. 2017. “Power and Resistance in Early Childhood Education: From Dominant Discourse to Democratic Experimentalism.” Journal of Pedagogy 8 (1): 11–32.

- [NCCA] National Council for Curriculum and Assessment, Ireland. 2009. Aistear, the Early Childhood Curriculum Framework.

- New, R. S., B. Mardell, and D. Robinson. 2005. “Early Childhood Education as Risky Business: Going Beyond What's ‘Safe’ to Discovering What's Possible.” Early Childhood Research and Practice 7 (2): 1–26.

- Newman, S., and A. Hatton-Yeo. 2008. “Intergenerational Learning and the Contribution of Older People.” Ageing Horizons 8 (10): 31–39.

- Nimmo, J. 2008. “Young Children's Access to Real Life: An Examination of the Growing Boundaries Between Children in Child Care and Adults in the Community.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 9 (1): 3–13.

- Nowell, L. S., J. M. Norris, D. E. White, and N. J. Moules. 2017. “Thematic Analysis.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16 (1), 160940691773384-13.

- [NSCDC] National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. 2011. Building the Brain’s “Air Traffic Control” System: How Early Experiences Shape the Development of Executive Function [Working Paper 11, National Forum on Early Childhood Policy and Programs]. Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. http://www.developingchild.net

- Osgood, J. 2010. “Reconstructing Professionalism in ECEC. The Case for the Critically Reflective Emotional Professional.” Early Years: An International Journal of Research and Development 26 (2): 187–199.

- Page, J. 2018. “Love, Care and Intimacy in Early Childhood Education and Care.” International Journal of Early Years Education 26 (2): 123–124.

- Papatheodorou, T., and J. Moyles. 2009. Learning Together in the Early Years: Exploring Relational Pedagogy. London: Routledge.

- Percy-Smith, B., and N. Thomas. 2010. A Handbook of Children’s and Young People’s Participation: Perspectives from Theory and Practice. London: Routledge.

- Rogoff, B. 1990. Apprenticeship in Thinking. Cognitive Development in Social Context. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Rogoff, B. 2003. The Cultural Nature of Human Development. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Rogoff, B. 2012. “Learning Without Lessons: Opportunities to Expand Knowledge.” Infancia y Aprendizaje 35 (2): 233–252.

- Rogoff, B. 2014. “Learning by Observing and Pitching in to Family and Community Endeavors: An Orientation.” Human Development 57 (3): 69–81.

- Sánchez, M., J. Sáez, P. Díaz, and M. Campillo. 2018. “Intergenerational Education in Spanish Primary Schools: Making the Policy Case.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 16 (1-2): 166–183.

- Schmidt-Hertha, B., S. J. Krašovec, and M. Formosa. 2014. Learning Across Generations in Europe - Contemporary Issues in Older Adult Education. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Shonkoff, J. P., and D. A. Phillips. 2000. From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Siraj-Blatchford, I. 2009. “Conceptualising Progression in the Pedagogy of Play and Sustained Shared Thinking in Early Childhood Education: A Vygotskian Perspective.” Educational and Child Psychology 26 (2): 77–89.

- Smith, A. 1996. “The Early Childhood Curriculum from a Sociocultural Perspective.” Early Child Development and Care 115 (1): 51–64.

- Sommer, D., I. Pramling Samuelsson, and K. Hundeide. 2013. “Early Childhood Care and Education: A Child Perspective Paradigm.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 21 (4): 459–475.

- [TOY] The Together Old and Young (TOY) Project Consortium. 2013. A Review of the Literature on Intergenerational Learning Involving Young Children and Older People. http://www.toyproject.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/TOY-literature_review_FINAL.pdf

- Trevarthen, C. 2012. “Finding a Place with Meaning in a Busy Human World: How Does the Story Begin, and who Helps?” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 20 (3): 303–312.

- Tudge, J. R. H., J. L. Navarro, E. A. Merçon-Vargas, and A. Payir. 2021. “The Promise and the Practice of Early Childhood Educare in the Writings of Urie Bronfenbrenner.” Early Child Development and Care 191 (7-8): 1079–1088.

- [UN] United Nations General Assembly. 2015. Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: UN.

- UNESCO. 2000. The Right to Education: Towards Education for All Throughout Life. World Education Report. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

- VanderVen, K. 2011. “The Road to Intergenerational Theory is Under Construction: A Continuing Story.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 9 (1): 22–36.

- Vygotsky, L. 1978. Mind in Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Watts, J. 2017. “Multi- or Intergenerational Learning? Exploring Some Meanings.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 15 (1): 39–51.

- Whitebread, D., and P. Coltman. 2011. “Young Children as Self-Regulating Learners.” In Beginning Teaching, Beginning Learning in Early Years and Primary Education, edited by J. Moyles, J. Georgeson, and J. Payler. 4th ed, 122–138. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Wyness, M. 2013. “Global Standards and Deficit Childhoods: The Contested Meaning of Children's Participation.” Children's Geographies 11 (3): 340–353.