ABSTRACT

Despite a focus on successful transitions to school, transition to School Aged Care (SAC) has largely been overlooked. This paper shares insights into transition programs provided for children commencing in SAC, at or close to their transition to school. Educators working in SAC programs in Victoria, Australia, participated in an online survey exploring their practices, beliefs, and understandings regarding children’s transition into SAC in their Foundation year of school. Findings highlighted that whilst transition to SAC should be considered an integral component of a child’s broader transition to school program, very few SAC programs are formally included in the process. Findings also showed that the programs that do offer transition to SAC programs for children commencing their Foundation year of school tend to design and implement these externally to the broader transition-to-school process. Furthermore, SAC educators share a strong consensus that clear integration of transitions into SAC and school should occur.

Introduction

In 2020 across Australia almost half a million children (n = 489,800) aged between five years and twelve years accessed formal school aged care (SAC) programs (Department of Education, Skills and Employment Citation2020), also referred to as Outside School Hours Care (OSHC) (Department of Education and Training Citation2022). This reflects overall trends in Australia with increasing numbers of young children accessing SAC ‘doubling every decade since 1996’ (Simoncini, Caltabiano, and Lasen Citation2012, 108). Simoncini, Cartmel, and Young (Citation2015, 114) corroborated this growth in later research finding that SAC ‘is the fastest growing sector of childcare services in Australia’. Defined as ‘recreation, play and leisure-based programmes for children aged 5–12 years in before and after school settings, and in the vacation periods’ (Cartmel Citation2007, iii), these programs provide a conduit for children between their home lives and school lives (Cartmel Citation2019). Many SAC settings in Australia are co-located on school sites yet remain separate from the educational profile and program of the school (Dockett and Perry Citation2016). Whilst some are managed by the school and the SAC educators school employees, many are often managed by external management groups with the staff employed by this external management arrangement. Early years programs in Australia are all governed by a National Quality Framework (Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority Citation2012) that incorporates both regulatory and quality systems as well as approved learning frameworks to guide practice in both early childhood education and care (ECEC) and SAC programs. Building on from the early years learning framework, ‘My Time, Our Place’ (MTOP) was developed to specifically reflect the practice and context of SAC and aims to extend and enrich children’s wellbeing and development in school-aged care settings (Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations Citation2011; Australian Government Department of Education Citation2022b). Featured as a key practice principle in both these documents is a focus on the transitions for children within and across services and settings.

‘As children make transitions between settings (including school) educators from school age care settings, schools and other children’s services, support the transitions by sharing appropriate information about each child’s capabilities and interests’ (Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations Citation2011, 17).

Many children transition into SAC services at or immediately prior to commencing in their Foundation year of compulsory school education (CSE). Transition from preschool to compulsory school education (CSE) is a significant milestone for young children and their families. A positive start to school is associated with long-term positive learning and well-being outcomes for children (Margetts Citation2014). Collaborative partnerships between each of the sectors (ECEC, CSE and SAC) can countermand any discontinuities that may arise for children and families during the transition process (Dunham et al. Citation2016). When teachers and educators across the sectors develop collaborative partnerships, enabled through an emphasis on relationships, continuity, congruence and shared language (Dockett and Perry Citation2007; Griebel and Neisel Citation2013; Jerome, Hamre, and Pianta Citation2009), opportunities arise to amalgamate diverse perspectives and approaches, leading to continuity and more effective transitions for young children (Dockett and Perry Citation2016, Citation2014; Moss Citation2013). However, despite a focus on successful transitions, a focus on transition to SAC as part of the life stage event seems to have largely been overlooked (Dockett and Perry Citation2014).

In order to partially address this gap, this paper will report on a study which sought to gain insights into transition programs provided for children commencing in SAC at or close to the transition into their Foundation year of CSE. Educators working in SAC programs were invited to participate in an online survey that included both closed and open-ended questions to enable respondents to respond to the framing research question:

What are the practices, beliefs, understanding of SAC educators regarding children’s transition into SAC in their Foundation year of CSE?

The findings highlight that whilst transition to SAC should be considered an integral component of a child’s broader transition to school program, very few SAC programs are formally included in the process. The programs that do offer transition to SAC programs for children commencing their Foundation year of CSE tend to design and implement these externally to the broader transition-to-school process. However, despite this, the findings demonstrated a strong consensus by the SAC participants that clear integration of transitions into SAC and school should occur.

Transition into SAC

Transitions in schooling and education involve change as children move into new educational environments. This is true of children transitioning from ECEC into the school environment, which for many includes not only the school and classroom, but the Outside School Hours Care they participate in before and after the school day, and also during the school vacation periods. Dockett and Perry (Citation2016, 312) highlight that rather than being a point in time ‘educational transitions occur over time, beginning well before children move into a new educational environment and extending to the point where they, their families and educators recognise a sense of belonging in that space’. Transitions are located within a specific time of change in children’s lives and require ongoing negotiation and navigation, as individuals build new relationships. They go on to argue that the process of transition affords opportunities to build relationships, promote continuity, recognise change and acknowledge the significance of the change in the lives of all involved.

When children commence in a SAC program, they become members of that SAC community, and whilst this new community may include some aspects of the children and families’ wider school or social networks, the children may also be joining a community where they will be building new connections. In the context of transition to SAC, children make the transition between school and SAC regularly, often daily, involving the physical movement between contexts (such as home to SAC and SAC to school). These transition experiences involve a process of adjustment for both children and families (Dockett et al. Citation2017) as they will be navigating new relationships, ‘rules’ contexts and expectations. Dockett and Perry’s (Citation2016) study investigating children’s transitions into SAC found that process and actions which involved building relationships by connecting with children, families, and other professionals, as well as the provision of flexible and responsive transition programs were effective in supporting positive transitions into SAC. These connections with children and families included strategies such as providing information to families about the SAC program, children having an opportunity to visit the setting prior to starting in the program, and the sharing of information between parents and SAC educators. Additionally, some of the participants in their study also participated in the broader transition to school processes that were occurring in the local community in the lead up to children starting school.

Whilst there is a body of literature which focuses on children’s transition to school, and the importance of including SAC in this process (see for example Dockett and Perry Citation2014), there is very little literature which examines children’s transition into SAC separately to the transition to school process. Whilst many children make the transition into SAC when they make the transition from ECEC to school, this is not always the case. Dockett and Perry (Citation2014) however, argue that although this literature is scant, the same elements which underpin many other educational transitions also apply to the transition into SAC. Effective transitions are those which are child-centred and contextually relevant, and heavily geared towards building effective collaborations between children, families and the setting. Additionally, good relationships between professionals which are underpinned by respectful and reciprocal relationships between educators across sectors are at the heart of positive transitions (Cartmel and Hayes Citation2016; Dockett Citation2018; Karila and Rantavuori Citation2014). Collaborative relationships between school and SAC educators require engagement which is open and non-judgmental, and has mutual regard for each other’s perspectives (Cartmel and Grieshaber Citation2014; Dockett and Perry Citation2014), however Pálsdóttir (Citation2014) argues that SAC educators are not always perceived as a valued member of the school community.

Collaborative relationships

Cross-sector relationships have been identified as a key practice in both the Australian early years learning framework (EYLF) (Australian Government Department of Education Citation2022a) and MTOP (Australian Government Department of Education Citation2022b), however systemic influences have meant that these relationships cannot always be effectively established. While many SAC programs are located on school sites, many SAC programs are managed and staffed by management groups external to the school (Cartmel Citation2019) and as such educators are not necessarily considered members of the school’s staff (Dockett and Perry Citation2014).

SAC programs provide ‘stimulating developmental, social and recreational activities for children, while meeting the care requirements of families’ (Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations Citation2011, 13). Societal attitudes to SAC have led to a lack of understanding and appreciation of the role played by SAC in the lives of children and families, with SAC is often viewed as child-minding – fulfilling a parental need, rather than being of benefit to children (Cartmel and Hayes Citation2016). Whilst school staff mainly see their role as education-based, the view of SAC as being a time for recreation, play and leisure (Cartmel Citation2007) can lead to a lack of valuing and understanding between school and SAC staff regarding the important role SAC educators play in children’s live. This can result in SAC educators being positioned, or positioning themselves, as outsiders in the school or educational environment (Dockett and Perry Citation2016). Recent research has focused on the role of the SAC professional and their developing identity in the primary school space (Cartmel and Hayes Citation2016; Cartmel and Grieshaber Citation2014). These researchers highlighted a lack of appreciation of their role in school aged settings by principals and teachers within the school, with the SAC staff not considering their professional self is valued in interactions with other non-SAC staff. The role that SAC programs play in supporting children’s social, emotional, wellbeing, development and sense of agency (Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations Citation2011) is not always recognised when SAC is viewed as just play and recreation and the work of the educators is not seen by the school staff as belonging in the school (Pálsdóttir Citation2014).

Collaborative relationships between and across the education sector do not only involve the relationship between schools and SAC programs, but also recognise the importance of continuity for children and families between their early childhood experiences and the transition into SAC as a key component of the transition into formal schooling (Department of Education and Training Citation2017; Dockett and Perry Citation2014; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Citation2017). There have been calls for educators in prior-to-school and school settings to build relationships that support a ‘strong and equal partnership’ with educators across the broad school sector (Bennett Citation2013). Yet despite the importance of collaborative connections as children transition from their early childhood setting into SAC, there is little focus on this in the transition literature, and anecdotal experience of the authors would suggest that whilst there are collaborations between the teachers in the prior-to-school programs and the teachers in the schools, connections and collaborations between prior-to-school and SAC educators rarely occur.

Transition as a ‘bridge’: a theoretical framework

Huser, Dockett, and Perry (Citation2016) drawn on the metaphor of a bridge in conceptualising children’s transitions from ECEC to compulsory schooling. Drawing on the notion of a bridge is relevant when examining children making the transition from ECEC to school and all this entails, as bridges represent an opportunity to explore what lies on either side of the expanse, and to journey into new areas. This paper draws on the analogy of transitions as a bridge in framing the way children transition into SAC. Huser, Dockett, and Perry (Citation2016, 444) go on to suggest that there are ‘many bridges that may be constructed and/or traversed as children make the transition to school’, and for children transitioning into SAC, this transition is just one of the many bridges they must traverse. SAC is the bridge for children that connects home and school, the school and their experiences outside of school, and for many children the bridge connecting their prior-to-school setting and the school environment. In analysing the findings from this study, this analogy can be further explored. An image of a bridge is one where there are connecting strands, ropes holding these strands and the bridge together to make it sturdy, and planks to support the traveller as they journey across. When one component of the bridge is faulty, the journey can be compromised.

On the transition to school bridge, it could be interpreted that the families, the foundation school teachers (first year of compulsory school education), the ECEC teachers and the SAC program are all critical components that hold the bridge together and allow the child to cross. When one component is less strong, such as the connection between the prior-to-school setting and the SAC, or the SAC and the school, then the bridge becomes less sturdy, making it more challenging for children and families to transverse across and make a strong and enduring connection with the SAC program.

Research methodology and design

This study drew from responses to an anonymous online survey which included questions requiring both quantitative and qualitative responses, to provide a fully and more complete picture of the phenomenon (Denscombe Citation2014). In this study the phenomenon was the beliefs and practices of the SAC educators regarding transition into SAC. Qualtrics software was used to generate the survey, which included 16 closed questions that required either a Yes/No response, or selection from a range of pre-populated options. An additional 15 open ended questions were included that invited participants to provide a free text response that provided an opportunity for richer description and reflection regarding beliefs and practices.

Information about the project and a link to the online Qualtrics survey was posted on Facebook platforms used by SAC educators inviting interested SAC educators to participate. Author two who is a member of these professional Facebook groups emailed the administrator seeking approval to post information on the Outside School Hours Care (SAC) Network and Victorian SAC Educators sites. Access to the survey was available for a period of six weeks.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval to conduct the study was granted by the University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number HAE-21-048). To ensure informed consent, a Plain Language Statement was provided on the landing page of the survey, where participants were provided with the option to participate in the survey by checking the box: ‘yes, I have read the Plain Language Statement and I consent to participate in the survey’. The landing page also advised that any participant could withdraw by exiting the survey at any time. Once this was checked, participants were taken to the survey questions. The online survey was anonymous providing confidentiality for participants. This eliminated any power relationship between the researchers and the participants.

The participants

Sixty-one participants, undertaking a range of roles in SAC responded to the survey, although not all participants completed all the questions (see ).

Table 1. Breakdown of respondents by role.

Most survey respondents had worked in SAC programs for more than 10 years (33% – n = 21); with twenty-four percent (n = 15) between 6 and 10 years, and twenty-one percent (n = 13) between 3 and 5 years. Three participants (4%) had been working in SAC for 1–2 years and eight (13%) for less than a year. The survey asked a series of questions focusing on transition to school and SAC the majority of which referred to transition for all children and 14 of which focused on transition to school and SAC for children starting their foundation year of CSE. Twenty (of the total 61) participants specifically responded to the questions that referenced children starting their Foundation year of CSE. This paper reports on the survey findings that explored Foundation children’s transition to SAC and school.

Findings

Once the survey was closed to participants a report of all responses was generated, using the report function in the Qualtrics software program. The report was generated as both a Word Document and an Excel Spreadsheet. As the responses included both numeric data as located in the closed questions provided, and qualitative open-ended responses to the questions providing opportunity for participants to add additional text, a twofold approach to analysis was utilised. The closed questions required a simple aggregation of the responses which was undertaken by adding the number of responses indicating either Yes or No to the specific question, or in the case of questions with the option for multiple responses, adding the number of responses to each item in the list. The open-ended responses were then analysed by reading through the responses to each question and identifying patterns across the data (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Only some participants provided responses to these open-ended questions. The written responses were initially grouped through the development of several broad categories, which were further coded to identify key themes. This coding was undertaken simultaneously by all three authors examining the responses and sharing thoughts regarding the with the appropriation of categories. This process resulted in identification of the following key themes: Implementation of transition to SAC programs; connections with teachers; SAC participation in the transition to school process; and, connecting with parents in the transition to SAC process. These key themes will now be examined in depth.

Implementation of transition to SAC programs

From the survey responses it is apparent that children in their Foundation Year of school mostly commence SAC either at the start of the school year (n = 24) or within the first few weeks of starting school (n = 12). Three participants indicated that the Foundation Year students commence SAC during the Summer Vacation Care program prior to the start of the school year (see ).

Participants were asked if they felt there should be a transition program for the Foundation children commencing SAC. Eighteen responses to this question were provided. Interestingly, eleven participants indicated that yes there should be a transition program specific to the Foundation children commencing SAC, whilst two replied no. Five participants responded that they had never thought about it. Participants were invited to expand on their response and indicative comments include:

It would be great for students to be able to have a guided transition rather than throwing them into the deep end.

As they are going through one of a major change in their lives they need to be supported through this change

This way the children know what to expect and can begin to build a sense of belonging

One participant, who indicated that her SAC does not offer a formal transition program for Foundation children, clarified that:

We encourage children to come to Summer Vacation Care as a means of transition and it has worked very well.

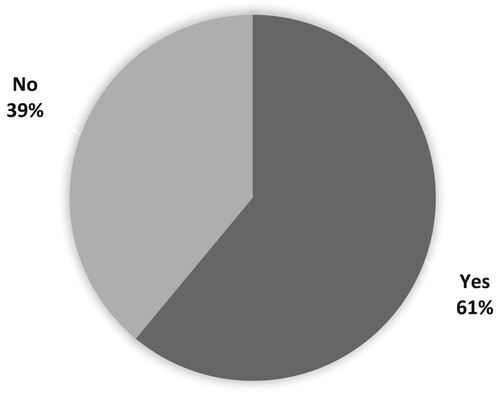

Participants were asked to identify whether a transition program for children commencing SAC was offered in their service. Of the 59 participants who responded to this question, 61 percent (n = 36) indicated they do have a transition program for children commencing SAC whilst 39 percent (n = 23) indicated they did not (see ). Of the 36 participants indicating they did offer a transition program, only some (n = 19) offered a separate, tailored transition program for children transitioning into SAC in their first year of school (Foundation). Participants were asked about the timing of the transition to SAC program. Four respondents indicated that this commenced in the final months of the child’s preschool year; four indicated the transition program commenced in the first week of the school year; four respondents indicated that this occurred in the weeks prior to the school year commencing; and two suggested the transition program occurred on the day the child commenced the SAC program ().

When asked why there was no transition program offered by their service, 18 participants responded. One indicated that the management had made a decision not to provide a transition program, whilst 12 indicated that it had not been considered. The remaining five responses included lack of time, a belief that families did not see it as a priority, and one indicated she did not know why there was not a transition program offered at her SAC service.

Connection with teachers

Four questions specifically sought information regarding the way the SAC service connected with the child’s teachers – both the Foundation teacher and the child’s previous preschool teachers. In relation to having contact with the children’s Foundation teacher, fifteen responses indicated that this did occur and 5 indicated that contact with school teachers did not occur. Contact with school teachers mainly included:

Attending orientation sessions at the school in the final term prior to the child starting school;

Meeting with the teacher daily or when required so that information can be exchanged.

Taking the child to the classroom (at both ends of the day); helping the children settle into their classroom at the start of the school day;

For children who have additional learning needs, there was an indication by two participants that they met with the Foundation teacher to develop individual learning and behaviour plans. When asked if this should occur 16 (of 20) responded positively. Further elaboration in the open-ended questions mainly focused on building holistic understanding of the child’s strengths, interests and needs: ‘So that everyone is on the same page regarding the children’ was an indicative comment. For the participants who indicated that they did not connect with the Foundation teacher, only two elaborated, explaining that ‘time issues’ and not being co-located were key factors that affected their ability to connect.

When asked about connections with the child’s previous preschool teacher, 20 participants responded to this question. Six respondents provided positive responses, whilst 14 provided a negative response. When these connections do occur, the responses indicated that this mainly occurs if the preschool is on the same site as the SAC program and involves the sharing of information regarding children’s challenges. One respondent suggested that ‘ELCs [early learning centres] don’t consider OSCH as important learning spaces’. However, when asked if connections between the SAC program and the child’s preschool teacher should occur, of the 20 responses received, 16 provided a positive response, and four responded negatively. The responses to the open-ended questions centred on the benefits of these connections for building holistic understanding of the children, their needs, likes, and gaining further background information. Of the negative responses, not being co-located was cited as a reason, along with one participant expressing that it was not necessary as ‘the child has graduated from preschool’

SAC participation in the transition to school process

Participants were asked to share their beliefs and practices in relation to their connection with the broader transition to school processes for the children making the transition from preschool into school. Of the 37 participants who responded to this series of questions, overwhelmingly there was a belief that the SAC educators should be included in this process (33 of 37 responses). A survey prompt asked respondents to select from a range of options identifying the ways that SAC educators could be included in the transition process. A tally of the responses are listed in (multiple responses were permitted), with the most popular responses being their attendance at school parent information sessions, hosting SAC parent information sessions and being part of school tours for families. However, when asked if they are currently involved in the wider transition to school program, only ten (of 38) participants indicated that they were included in the process ().

Table 2. Ways SAC educators can be included in the Transition to School Process.

The transition to school policy documents

The transition to school policy and process for children in Victoria includes the use of a transition learning and development statement (TLDS) for each child, developed by the child’s preschool teacher and made available to the school the child will be attending. This document is electronically sent by the Preschool teacher to the school and is usually accessed by the Foundation Year teachers to use for planning and curriculum design. However, there is also an expectation in the policy documents regarding transition to school in Victoria (Department of Education and Training Citation2017), that SAC programs are able to access or receive these statements also to support the children making the transition not only into the school classroom and school environment, but into the SAC program as well.

The participants were asked to identify if they received a copy of the child’s transition to school statement. Thirty-eight participants responded to this question. Five responses indicated that they did not know what the transition statement is, 26 responded that they did not receive the statement and seven respondents indicated that they did receive a copy of this TLDS. Three of the participants who confirmed that they do receive a copy, indicated these had been provided by the parents, two participants received their copy from the school teacher and two received their copy from the pre-school teacher.

In 2017, the state education department produced a transition to school resource kit that provided guidance and best practice approaches to support effective and collaborative processes across the CSE, ECEC, SAC and specialist services. Participant were asked about the usage of this Kit. Thirty-eight responses were provided. Two participants indicated that they did use the Kit, eleven responded that they did not and 26 participants indicated that they did not know of it. Included in this resource kit is a suggestion that SAC programs should be part of a professional community transition to school network. When asked about this, of the 39 responses provided, only nine indicated that they were part of a professional transition to school network, whilst the remaining 30 were not.

Connecting with parents in the transition into SAC

The importance of connecting with parents in their child’s learning is a key understanding across education globally. The survey data indicated that parents are connected to the transition to SAC process, and these connections are enabled through engaging with parents in a variety of ways. Participants were asked to check all the options (n = 10) that applied to them. Responses are identified in the table below, with the most popular responses being the provision of information about their program via pamphlets and brochures (among other means), completion of enrolment details and seeking to learn of the child’s interests, strengths, friendships and likes/dislikes directly from parents ().

Table 3. Processes and approaches to engaging with families.

Discussion

In seeking to gain insights into transition programs provided for children commencing in SAC at the same time, or close to the transition into their Foundation year of CSE, it appears that for the participants in this study there is a level of ambiguity and ambivalence in the way they approach the transition process. For most of the participants, the children they work with mainly transition into SAC as they commence the school year, providing little opportunity for children and families to ease into the program slowly. This is contextually important as in Victoria, Australia where this study was undertaken, very few ECEC programs are co-located alongside schools, where most of the SAC services are located. In revisiting the bridge metaphor, a bridge is about accessibility and connectivity. Transitioning into SAC at the start of the school year disconnects the child from their previous ECEC service, losing familiarity and a sense of connection, as they make connections with a new service type, new adults and new children. Very rarely does the transition into SAC commence in the final months of the child’s preschool year, but more commonly children commence SAC at the time they commence school. Commencing SAC at the same time as starting school results in an approach to transition that can only commence when children officially begin attending the service. This is reinforced by the findings that showed very few respondents undertake a formal transition program with children prior to commencing school, and transition can be viewed as commencing at a point in time, rather than as Dockett and Perry (Citation2016) suggest starts in the year prior and continues until children feel a connection with the program. The SAC educators’ practices offered a differing view of what a ‘transition program’ is understood to be, where for the children transition has a starting point rather than being a continual process. For many children there are minimal opportunities to slowly transition into the SAC program and there is limited connectivity between SAC and their prior to school experiences. The findings indicated that the transition process was more informal, with practices put in place to support the children to connect with the program once they had started, build relationships with peers and educators, and feel a sense of belonging within the program.

Some children do commence SAC in the vacation period prior to starting school. Whilst this provides a valuable opportunity for children to connect with the school, the school environment, and the SAC program prior to commencing school, it could be argued that this is not of itself allowing a transition process if children have little opportunity to engage with the service prior to commencing vacation care. Attending SAC during vacation prior to starting school provides important contextual opportunities for the child and is an integral component of transitioning into school. By starting at the school in the recreation and play based program offered in SAC, children are able to develop a familiarity with the school environment, and begin to form both horizontal and vertical peer relationships with children at the school. Through playing with peers, children can develop pro-social skills and cultivate friendships (Pálsdóttir and Kristjánsdóttir Citation2018). However, as a process of transitioning into SAC, it shifts the transition process to starting at a specific point in time. Many of the SAC educators reported the adoption of intentional planning and strategies to support these children to feel connected with the service, and identified that these occur for a number of weeks.

The enabling factors or the integrity that makes for a strong connecting bridge lies in the strength of the strands or ropes holding it together, all of which contribute to making the bridge sturdy so as to support the traveller as they journey across. A key ‘rope’ that contributes to the robust and sturdy integrity of the transition to SAC bridge is the forming of ‘strong and equal partnerships’ between educators across the broad education sector, which has been recognised in both literature and policy documents internationally (Australian Government Department of Education Citation2022a; 2022b: Bennett Citation2013; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Citation2017). In regard to SAC and school teachers, it is clear that some SAC educators do connect with the child’s Foundation teacher. These connections are viewed as opportunities to share information between the school and SAC about the child’s day, or to exchange information to pass on to or from families. They are seen as positive, and integral to children’s transition into SAC. The opportunities provided created a feeling for the SAC educators of continuity for the child. However, it was also noted that these connections did not always occur, as there were a number of participants who identified little to no connection with the Foundation teachers. This lack of connection between SAC and CSE is not just the perception of these participant. Simoncini, Cartmel and Young’s (2015, 115) study presenting children and staffs’ insights about SAC found ‘great diversity’ exists in the ‘structures of communication’ between school and SAC. Additionally, this resonates with Dockett and Perry’s (Citation2016, 310) suggestion that SAC is disconnected from the overarching ‘profile of the school’. Dockett and Perry go on to suggest that this generates a ‘together but apart’ notion which could attribute to constraints a continuity for children across the services.

When considering connections with prior to school educators and SAC educators however, such connections were considerably less frequent, suggesting that the ropes creating a robust and sturdy bridge may be faulty. Whilst many of the participants in the study noted the importance of these connections there was very little connection with the child’s prior-to-school program. Given the number of participants for whom this was important it can be posited that many educators from the prior-to-school settings do not see SAC as important when thinking about children’s transition into the CSE environment. It is interesting to examine this in the context of the transition to school literature and policy as this could provide some insights into why this may be. In the Starting Strong V Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (Citation2017) publication, there is a large section focusing on continuity between ECEC and CSE, and the importance of continuous professional connections, however reference to SAC is absent in the document. Additionally, whilst policy documents (Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations Citation2009, Citation2011) focus on continuity during transitions discussion is quite broad in noting other community settings as being important, or using generic terms such as school educators (Dockett Citation2018), rather than drawing the same specific connections as found between ECEC and CSE. The focus on children’s learning can in many ways tunnel ECEC teachers into disregarding SAC as something children will be participating in when they commence school. Despite the data which shows the increased number of children attending SAC programs, with SAC being somewhat invisible in the thinking of ECEC, reinforcing Simoncini, Cartmel, and Young’s (Citation2015) assertion that SAC has been considered the ‘poor relative’ in the ECEC space. It could even be suggested that it is an ‘invisible’ relative to many ECEC settings in the transition to school process.

The literature (see for example Dockett Citation2018; Dockett and Perry Citation2016; Simoncini, Cartmel, and Young Citation2015) highlights the importance of collaborative connections between and across the schooling and education sectors, and there was an overwhelming belief by the participants that they should be included as an integral component of the broader transition to school process. Whilst most of the Foundation children tend to commence the SAC program at the start of their school year, many of the SAC educators identified that they are marginalised in the transition process and often not considered in any decision-making regarding transition programs. This is despite government policy which identifies that SAC is a key aspect of children’s transition to school and should be included in decision making and in the sharing of information to inform planning and individual programs to support children to settle into this new environment (Department of Education and Training Citation2017). The SAC educators identified a number of ways that they could be included in the broader to transition process but in keeping with the findings of Simoncini, Cartmel, and Young (Citation2015) don’t feel that they have a voice or capacity to share their ideas. Should SAC educator be included in the decision-making process, our study shows that such collaborations would invite greater potential for supporting continuity as it would provide SAC educators more opportunities to connect with prior-to-school programs as well. Thus, reframing transition from having a starting point at the beginning of the school year, would reinforce the notion of transition as being a continuous process (Dockett and Perry Citation2016).

The importance of families being partners with educators in their child’s learning and development is recognised across the literature and in policy in many western countries (Hadley and Rouse Citation2021; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Citation2017). The My Time Our Place practice framing document recognises the importance of SAC educators creating a ‘welcoming and culturally safe environment where all families are ‘respected regardless of background, ethnicity, languages spoken, religion, family makeup or gender’ (Australian Government Department of Education Citation2022b, 15). Connections with parents is therefore a critical component, and was shown to be valued by the SAC educators in this study, with many ways of connecting with families identified by the participants. However, many of the ways the SAC participants connected with families involved the unidirectional transmission or provision of information about the service, or when bidirectional, in simply seeking information from the family in relation to the enrolment process. It can be argued that whilst this level of involving parents in the program is facilitates connections with families, there is little mutuality and reciprocity present where families are empowered equal partners in decision making (Rouse Citation2012). What seemed apparent from the survey responses was that there was little sense of the role of families in collaborating with educators about ‘program decisions in order to ensure that experiences are meaningful’ (Australian Government Department of Education Citation2022b, 15). In this aspect, the voice of the families as an equal and valued partner (Lehrer et al. Citation2023) was largely absent from the responses.

Conclusion

The analogy of ‘transition as a bridge’ (Huser, Dockett, and Perry Citation2016) has been a useful metaphor to explore the transition experiences of children into a SAC program. Whilst this study included only the voices and perspectives of the educators, it was apparent that for some children, the components that contribute to the integrity of the bridge – a bridge used to support children to traverse from pre-SAC experiences to SAC – were not always present. It is well recognised that good transitions are those that occur both before the child starts, in addition to post-commencement in the new program (Dockett and Perry Citation2007, 2014, 2016; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Citation2017). This study has outlined that for many children commencing SAC, the opportunity for them to begin the transition process before they commence in the program was denied them, and that there were little connections between children’s prior to school experiences and their SAC program. For the SAC participants in this study, the opportunities to establish strong connections with both the prior to school programs and the broader school community has been absent in the transition process, leaving the educators to design what they are seeing as a transition program for children when they commence the service, rather than what good practice dictates should commence well before children start school (Dockett and Perry Citation2016). There is a sense that the SAC program is invisible when it comes to a connected and considered transition to school program and process, leaving the ‘bridge’ to be at risk. Whilst there is a clear message in the policy context that SAC is of equal and valued importance in children’s transition into CSE, disappointingly it seems there is still much work to be done. Whilst the findings of the study are relevant largely to the Australian early years context, wider consideration of the implications for international practice and approaches to positioning SAC as a key component of many young children’s lives warrants further investigation. Given that Starting Strong V (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Citation2017) was produced to provide global insights into transitions from ECEC to primary school. SAC, however, is largely absent from this document, signalling the invisibility of SAC in the wider transition to school conversation – an omission that needs to be redressed.

Limitations

Whilst this paper is situated within the Australian SAC context it has identified some interesting insights into SAC educators’ perceptions regarding transition into SAC that can inform SAC programs and educator practice more globally. It is also acknowledged that these findings are not without their limits. Being a small-scale online survey that SAC educators could opt into meant that it was only those who felt they wanted to contribute to the dialogue responded. There were only 61 participants in total and not all of these chose to respond to questions relating to children in their foundation year. This is a small number when seen in the context of the numbers of SAC programs operating across Australia. Additionally, the respondents were mainly from Victoria, resulting in the responses in many ways being context specific. It may be argued that in other contexts, responses may have differed. The study only drew on the voices of the SAC educators and as such there is an opportunity for further research that seeks the views of the ECEC and CSE teachers, families and the children themselves.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority. 2012. National Quality Framework. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/national-quality-framework.

- Australian Government Department of Education. 2022a. Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia (V2.0). Australian Government Department of Education for the Ministerial Council. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-01/EYLF-2022-V2.0.pdf.

- Australian Government Department of Education. 2022b. My Time, our Place: Framework for School Aged Children in Australia (V2.0). Australian Government Department of Education for the Ministerial Council. https://www.acecqa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-01/MTOP-V2.0.pdf.

- Bennett, J. 2013. “A Response from the Co-Author of ‘A Strong and Equal Partnership’.” In Early Childhood and Compulsory Education: Reconceptualising the Relationship, edited by Peter Moss, 52–71. London: Routledge.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Cartmel, J. 2007. Outside School Hours Care and Schools. (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation). Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane. http://eprints.qut.edu.au/17810/1/Jennifer_Cartmel_Thesis.pdf.

- Cartmel, J. 2019. “School Age Care Services in Australia.” International Journal for Research on Extended Education 7 (1): 114–120. doi:10.3224/ijree.v7i1.09.

- Cartmel, J., and S. Grieshaber. 2014. “Communicating for Quality in School age Care Services.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 39 (3): 23–28. doi:10.1177/183693911403900304.

- Cartmel, J., and A. Hayes. 2016. “Before and After School: Literature Review About Australian School Age Child Care.” Children Australia 41 (3): 201–207. doi:10.1017/cha.2016.17.

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2017. Research Methods in Education. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Denscombe, M. 2014. Good Research Guide: For Small-Scale Social Research Projects. Berkshire, UK: Open University Press.

- Department of Education and Training. 2017. Transition: A Positive Start to School Resource Kit, Melbourne: State Government of Victoria https://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/childhood/professionals/learning/Transition%20to%20School%20Resource%20Kit%202017%20FINAL.pdf.

- Department of Education and Training. 2022. Outside School Hours Care — Decision Making Regarding the Provision of OSHC https://www2.education.vic.gov.au/pal/outside-school-hours-care-decision-making-regarding-provision-oshc/policy.

- Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. 2009. Belonging, Being and Becoming: The Early Years Learning Framework for Australia. Canberra, ACT: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations. 2011. My Time, our Place: A Framework for School Aged Children in Australia. ACT: Government of Australia.

- Department of Education, Skills and Employment. 2020. Childcare in Australia report March quarter 2020. https://www.dese.gov.au/key-official-documents-about-early-childhood/early-childhood-and-child-care-reports/child-care-australia/child-care-australia-report-march-quarter-2020.

- Dockett, S. 2018. “Transition to School: Professional Collaborations.” Australian Educational Leader 40 (2): 16–19.

- Dockett, S., and B. Perry. 2007. Starting School: Perceptions, Expectations and Experiences. Sydney: UNSW Press.

- Dockett, S., and B. Perry. 2014. Continuity of Learning: A Resource to Support Effective Transition to School and School age Care. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government Department of Education.

- Dockett, S., and B. Perry. 2016. “Supporting Children’s Transition to School age Care.” The Australian Educational Researcher 43 (3): 309–326. doi:10.1007/s13384-016-0202-y.

- Dockett, S., B. Perry, A. Garpelin, J. Einarsdottir, S. Peters, and A.-W. Dunlop. 2017. “Pedagogies of Educational Transitions: Current Emphases and Future Directions.” In Pedagogies of Educational Transitions: European and Antipodean Research, edited by N. Ballam, B. Perry, and A. Garpelin, 275–292. Switzerland: Springer. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-43118-5_17

- Dunham, A., H. Skouteris, A. Nolan, S. E. Edwards, and J. Small. 2016. “A Cooperative Pedagogical Program Linking Preschool and Foundation Teachers: A Pilot Study.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 41 (3): 66–75. doi:10.1177/183693911604100309.

- Griebel, W., and R. Neisel. 2013. “The development of parents in their first child’s transition to primary school.” In International Perspectives on Transition to School: Reconceptualising Beliefs, Policy and Practice, edited by K. Margetts, and A. Klienig, 101–110. London: Routledge. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-43118-5_17

- Hadley, F., and E. Rouse. 2021. Educator Partnerships with Parents and Families with a Focus on the Early Years. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0272

- Huser, C., S. Dockett, and B. Perry. 2016. “Transition to School: Revisiting the Bridge Metaphor.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 24 (3): 439–449. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2015.1102414.

- Jerome, E. M., B. K. Hamre, and R. V. Pianta. 2009. “Teacher–Child Relationships from Kindergarten to Sixth Grade: Early Childhood Predictors of Teacher-Perceived Conflict and Closeness.” Social Development 18 (4): 915–945. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00508.x.

- Karila, K., and L. Rantavuori. 2014. “Discourses at the Boundary Spaces: Developing a Fluent Transition from Preschool to School.” Early Years 34 (4): 377–391. doi:10.1080/09575146.2014.967663.

- Lehrer, J., K. Van Laere, F. Hadley, and E. Rouse. 2023. “Introduction: Why we Need to Move Beyond Instrumentalization When Discussing Families and Early Childhood Education and Care.” In Relationships with Families in Early Childhood Education and Care: Beyond Instrumentalization in International Contexts of Diversity and Social Inequality, edited by J. Lehrer, F. Hdley, K. Van Laere, and E. Rouse, 1–13. London, UK: Routledge.

- Margetts, K. 2014. “Transition and the Adjustment to School.” In Transitions to School: International Research, Policy and Practice, edited by B. Perry, S. Dockett, and A. Petriwskyj, 5–88. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Moss, Peter. 2013. Early childhood and compulsory education: reconceptualising the relationship. UK: Routledge.

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. 2017. Starting Strong V: Transitions from Early Childhood Education and Care to Primary Education. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/9789264276253-en

- Pálsdóttir, K. 2014. “The Professional Identity of Recreation Personnel.” BARN 32 (3): 75–89.

- Pálsdóttir, K., and S. Kristjánsdóttir. 2018. “Leisure-time Centres for 6–9 Year old Children in Iceland; Policies, Practices and Challenges.” International Journal for Research on Extended Education 5 (2): 211–216. doi:10.3224/ijree.v5i2.08.

- Rouse, E. 2012. “Family-centred Practice: Empowerment, Self-Efficacy, and Challenges for Practitioners in Early Childhood Education and Care.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 13 (1): 17–26. doi:10.2304/ciec.2012.13.1.17.

- Simoncini, K., N. Caltabiano, and M. Lasen. 2012. “Young School-Aged Children’s Behaviour and Their Care Arrangements After School.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 37 (1): 108–118. doi:10.1177/183693911203700113.

- Simoncini, K., J. Cartmel, and A. Young. 2015. “Children’s Voices in Australian School Age Care: What do They Think About Afterschool Care?” International Journal for Research on Extended Education 3: 114–131.