ABSTRACT

The existing body of knowledge on the global experiences of im/migrant parents within early childhood education and care (ECEC) settings reveals a broad spectrum of concerns, which encompass various aspects of institutional education and care, as well as the parents’ own patterns of engagement in this realm. Navigating through the multitudinous and increasingly diverse array of parental perspectives, which are often marked by conflicting opinions, poses a significant challenge for ECEC practitioners. Against this background, this article draws on a collection of im/migrant and refugee parents’ experiences in the ECEC settings of the very different socio-cultural contexts of Tanzania and Norway. It explores how these voices can serve as sources of inspiration for the development of professional learning communities (PLC) among ECEC professionals. Furthermore, this article examines how professionals can manoeuvre through the impossibilities of satisfying every parent and instead create arenas for constructive dialogue (and disagreement).

Introduction

The international and interdisciplinary research community generally agrees on the comprehensive advantages of parental involvement in early childhood education (Epstein Citation2011; Garvis et al. Citation2022; Hornby Citation2011; Hryniewicz and Luff Citation2020; Hujala et al. Citation2009; Janssen and Vandenbroeck Citation2018; Sadownik and Visnjic Jevtic Citation2020; Vuorinen Citation2018). The importance of establishing a strong relationship between families and early childhood education and care (ECEC) settings has become even more crucial in the context of increasingly diverse and complex societies (Tobin Citation2020; Tobin, Arzubiaga, and Adair Citation2013). However, this diversity and complexity also make the relationship between ECEC and families harder to establish and maintain.

In their attempts to acknowledge the diversity of families and their values, ECEC practitioners tend to experience intense tension between cultural responsiveness and their own notion of best practices as anchored in the curriculum (Tobin, Arzubiaga, and Adair Citation2013; Tobin 2013). Regardless of the practitioners’ attempts, many im/migrant parents seem to ‘drop out’ from these arenas of communication and involvement (Glasser Citation2018; Leareau and McNamara Horvat Citation1999; Solberg Citation2018; Sønsthagen Citation2020), as they cannot relate to and engage with the meanings transmitted by the ECEC settings (Sadownik Citation2022; Solberg Citation2018). This ‘dropping out’ should not be interpreted as a form of disinterest in their children’s development, learning, and well-being, but rather as a mode of self-expression that seems to be the only option for relating to the unfamiliar ECEC services underpinned by majority discourses (De Gioia Citation2015; Solberg Citation2018; Van Laere and Vandenbroeck Citation2017; Van Laere, Van Houtte, and Vandenbroeck Citation2018).

The existing knowledge suggests two quite different strategies for handling the challenges that arise in collaboration between im/migrant families and ECEC. While some argue for the necessity of families’ internalisation of the ‘right’ cultural and social capital to allow for their participation in ECEC settings (Gedal Douglass et al. Citation2021), other underline the importance of a deep acknowledgement of each family’s culture and linguistic practices, together with their socio-emotional, spiritual, and religious/ethical ways of life (Gapany et al. Citation2022; Nagel and Wells Citation2009; New, Mallory, and Mantovani Citation2000; Taylor et al. Citation2008). A small number of qualitative studies conducted in Norway (Sadownik Citation2022; Sønsthagen Citation2020) and Finland (Lastikka and Lipponen Citation2016) has shown that attention and deep, culturally responsive explanations of ECEC practices provided during personalised meetings with the staff can transform the parental understanding of the ECEC settings and encouraged the migrant parents to reconsider own way of involvement in the ECEC and renegotiate it with a particular ECEC setting. Such findings are an empirical illustration of Van Laere et al.’s (2018) argument for creating policies and practices that would facilitate ‘communicative spaces for parents, professionals and researchers in which multiple, yet opposing, meanings can be discussed’ (187).

However, as many im/migrant parents enter ECEC settings with limited knowledge about the practiced pedagogy, which anchors their perceptions in experiences with (early childhood) education systems in their origin countries, and lead to misunderstandings and/or reduction of communication activities (Leareau and McNamara Horvat Citation1999). This is why Fenech and Skattebol (Citation2021) argue for the necessity of equipping individuals for inclusion. This could be done by satisfying the parental need for a deep understanding of institutional practices (Crosnoe Citation2007; Tobin, Arzubiaga, and Adair Citation2013) and reducing the asymmetries in power relations between the practitioners and the parents (Morrow and Malin Citation2004). A deeper understanding of ECEC services in the country of destination lifts migrant parents into a much less vulnerable position in their relations and resulting communications with the ECEC representatives. This is a position from which negotiations and disagreements are possible (Morrow and Malin Citation2004).

Creating the spaces for disagreements on pedagogies, practices and content between the im/migrant families and ECEC (Vandenbroeck Citation2009) requires however also a reflective preparation that in our view must be done by the ECEC practitioners. Specifically, the practitioners’ deep reflection on their own practices from the parental point of view (Sadownik, Sulen, and Hansen Citation2022), together with a consideration of how these practices could be sensitively and responsively communicated (Sadownik, Sulen, and Hansen Citation2022), needs to precede the dialogues/disagreements. Otherwise, the initiated dialogues will probably just confirm the existing pattern of cultural responsiveness reduced to ‘adjustments for religious diets, using children’s home languages in the morning greetings, (…) and celebrate[ing] a range of holidays’ (Tobin Citation2020, 15), while the established pedagogy will stay the same (Tobin, Arzubiaga, and Adair Citation2013).

In this paper, we demonstrate how knowledge of the im/migrant parent perspective can encourage professionals’ reflection of own/institutional practices (through the enablement of professional learning communities – PLCs) and thus potentially give the ECEC practitioners the insights necessary to engage in authentic dialogues full of dilemmas and disagreements (Anderstaf, Lecusay, and Nilsson Citation2021). By showing how migrant parents experience ECEC in very different cultural contexts, here Tanzania and Norway, we embrace both the complexity and universality of the migrant parents’ experiences. In doing so, we discuss how knowledge of these experiences may inspire PLC and help ECEC professionals authentically respond to these very different parental concerns.

Migrant parents’ perspectives enabling professional learning communities

Sharmahd et al. (Citation2017) argue that ‘the complex multi-diverse societies in which we live make it indeed impossible today to find standardised solutions for all families/children’ (Sharmahd et al. Citation2017, 5), which is why reflection and critical interrogations of existing practices in professional learning communities (PLCs) are so important. Such critical interrogations are, however, not possible without opening the community of practice up to other knowledges, other perspectives, and other understandings of the existing practices. This means that the staff meeting to reflect on and discuss their own practices on their own has little chance of being a legitimate PLC and will rather end up in either confirming the existing routines or inventing small, practical adjustments. Opening the door to new knowledge and perspectives of one’s own practice, either in the form of inviting another professional in person, or through ‘forcing’ themselves to see one’s own practice through the im/migrant parents’ eyes, can lift the community of practice to the PLC level. We believe that the migrant parent experience can function as the other perspective and inspire reflection, learning, and authentic practice improvements. This requires, however, openness about dilemmas and ‘cultivating conversational practices that open up and sustain attention to problems of practice’ (Little and Horn Citation2007, 89).

The Tanzanian and Norwegian contexts of ECEC

Before outlining the details of our study, we will describe how the ECEC sector is organised in Norway and Tanzania. These are two very different countries, where ECEC is anchored in two different traditions (Bennet Citation2010): the social pedagogy tradition, with an emphasis on play and well-being (Norway), and the preschool tradition, with an emphasis on early academic learning and school readiness (Tanzania).

In 2014, the recognition of ECEC as a great investment in society’s future led the Tanzanian government to organise a two-year-long compulsory pre-primary class for children aged four/five, free of charge for the families, and with safeguarded public funding. All of this was done to ensure that children starting primary school at the age of seven shared the same basis of experiences, cultural references, and skills. Therefore, the daily activities focused on those that are generally perceived as unavailable for children in their family environments, which facilitated literacy, numeracy, communication, and socio-emotional competences (MoEST Citation2016). The curriculum is competence-based and emphasises the use of play as a learning tool (MoEST Citation2016). A typical pre-primary classroom in Tanzania is organised with learning corners that reflect the five foundational skills a child should develop: (1) language, literacy, and communication; (2) personality and socio-emotional development; (3) creative, expressive, and aesthetic development; (4) mathematical and logical thinking; and (5) health and physical development (MoEST Citation2016). The obligatory and free-of-charge character of the pre-primary class increased enrolment in pre-primary education from 34% in 2016 to 95% in 2021 (MoEST Citation2021), making the pre-primary experience an almost universal one for children at that age. However, the rather low numbers of qualified teachers together with limited funding make the average child–teacher ratio 98:1 in public preschools and 15:1 in private preschools (MoEST Citation2021).

Norwegian ECEC settings, called kindergartens (Norwegian: barnehage), are organised under the Ministry of Education and Research and are offered to children aged 1–5, usually with separate units for toddlers (1–3) and older children (3–5). Due to guaranteed ECEC placement for every one-year-old and diverse payment reductions, 97.4% of children aged 3–5 and 87% of children aged 1–2 attend kindergartens in Norway (Statistics Norway Citation2022). All kindergartens must follow the same Framework Plan for Kindergarten (UDIR Citation2017), which describes democratic and sustainable values, as well as areas of knowledge and experiences that the kindergarten shall introduce the children to and make available for them. In this way, the Framework Plan outlines the goals for the staff, so that they provide all children with sufficient conditions for holistic development and well-being. Play is seen as the children’s way of being in the world and as an intrinsic value (UDIR Citation2017), which is why the policy-imposed content shall be made available for children through materials and activities inspiring children-initiated play.

The basic norms for the adult–child ratios, which are 1:3 for children aged 1–3 and 1:6 for children aged 3–6, require at least one staff member with a bachelor’s degree in ECEC teacher education per seven children under the age of three, and one ECEC teacher per fourteen children over the age of three.

Methodology

The reported study takes departure in very different ECEC traditions, as represented by Tanzania and Norway, to understand the complex variety of migrant parents’ experiences while also adding a kind of universality of the issue that applies regardless of where the children attend the ECEC setting. To gain insight into the parents’ perceptions, understandings, and experiences and ensure the possibility of a systematic analysis, we decided to use semi-structured interviews (Kvale Citation2008). The interviews were structured by three main topics, concerning (a) a story of migration to Norway/Tanzania, (b) enrolment in ECEC services, and (c) experiences of the ECEC services. The interview guide was developed in English – a common language of us – and was translated into Kiswahili and Norwegian, the languages in which the interviews were conducted.

Research participants and conducting the interviews

The research participants were parents from im/migrant backgrounds who had their children in ECEC services in Norway or Tanzania. In total, 67 parents were interviewed: 22 mothers and 11 fathers in Norway (between September 2020 and June 2021) and 15 fathers and 19 mothers in Tanzania (between August and October 2021).

The Norwegian participants were of both work-migrant and refugee backgrounds, representing countries in Eastern and Western Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. The Tanzanian participants were of refugee backgrounds from Burundi, Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, Somalia, Mozambique, and Uganda.

Research ethics

The part of the project conducted in Norway was approved by the Norwegian Centre of Research Data as being in line with GDPR and Norwegian legal guidelines on research. In Tanzania, ethical clearance was obtained from the National Bureau of Statistics and the ministry responsible for local government authorities. Further, a written permission from the UNHCR field office and refugee camp authorities was obtained to conduct research in their respective areas. All the participants were informed about the anonymous and voluntary nature of participation in the research and the free possibility of withdrawal.

An important ethical aspect of this study relates to power and loyalty relations. In the Norwegian context, the data were gathered by a researcher who was herself a work-migrant mother with a child in Norwegian ECEC. This was perceived by the researcher as a factor that facilitated trust among the migrant parents. Shared social experiences of being a non-Norwegian were mirrored in the participants’ utterances, such as ‘you know what I mean’, or ‘you were probably also shocked’. In the Tanzanian context, the researcher was Tanzanian, which could have influenced the responses from the participants (e.g. through a perceived need to express loyalty to the country that hosts them in a vulnerable life situation). Phrases used that made us reflect over power and loyalty relations were, for example, ‘far better than in my own country’ and ‘in my country, I would never have afforded pre-primary education’. Although both researchers were experienced in conducting qualitative research with human participants in different (also vulnerable) life situations and did their best to address the participants with sensitivity and respect, outside power relations could have had an impact on the interview results (Kvale Citation2007).

Data analysis

By focusing on identifying diverse aspects of the parents’ experiences, we conducted a thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). The main themes developed in the analysis were availability, care, and education. In this article, however, we present the subthemes related to the care and education themes, as these relate to migrant parents’ experiences of ECEC work (and not the bureaucracy of its availability).

The abbreviations used in the presentation of the findings are MM: ‘migrant mother’ and MF: ‘migrant father’ for describing the work migrants; and RM: ‘refugee mother’ and RF: ‘refugee father’ for parents with refugee backgrounds. All abbreviations are followed by numbers and the letters T or N for ‘Tanzania’ or ‘Norway’, respectively.

Findings

The subthemes below reflect the migrant parents’ shock, surprise, and disappointment, but also the appreciation of diverse practices, each of which will be presented briefly. Our findings confirm this existing research, particularly of Tobin, Arzubiaga, and Adair (Citation2013; Tobin 2016; Citation2020) on migrant parents’ experiences of ECEC. This significant overlap with the existing body of knowledge allows us to affirm that the presented perceptions of ECEC in these very different socio-cultural contexts of Norway and Tanzania capture the universality of the im/migrant parent experience. Specifically, this universality is captured in our analysis below through the two complex themes of care and education.

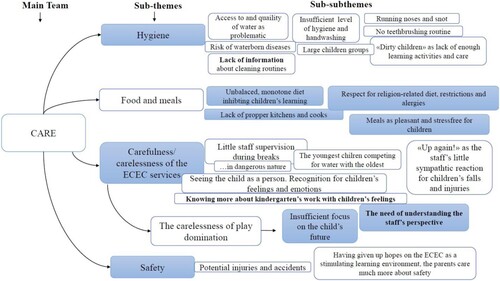

Care

below provides an overview of the subthemes and sub-subthemes associated with the care theme.

The subtheme hygiene was related to a wide spectrum of both Norwegian and Tanzanian ECEC routines, such as an insufficient level of handwashing, no tooth brushing routines, running noses, large children’s groups, risks for waterborne diseases, and ‘dirty children’ seen as lacking enough learning activities or good enough care. The lack of information about cleaning routines was also highlighted. As one mother put it,

It’s not clean enough – well, given my standards, it’s not clean enough … but if I knew how they think of and organise the cleaning, and that they really organise it, I could be calmer about it. (RM6_N)

The subtheme food encompassed sub-subthemes describing low quality and a lack of proper kitchens or staff improperly qualified in cooking, as well as unbalanced and monotonous diets inhibiting children’s learning. The im/migrant parents interviewed in both Norway and Tanzania expressed great concerns over the nutrition provided to their children. Nevertheless, they also appreciated ECEC services’ respect for religious diet restrictions and allergies and were generally happy about meals being pleasant and stress-free situations for the children.

The next subtheme, the carelessness/carefulness of the services, comprised parental concerns related to institutional lack of awareness and care about issues that were very significant to the parents when safeguarding their children’s well-being and well-becoming. In Norway, the concerns were related to outdoor sleeping routines (also in temperatures below zero) and the practitioners’ reactions to children who fell, which was often ‘get up again’ (whereas in the parents’ culture, it was natural to show more empathy for the child’s injury). In Tanzania, carelessness was associated with the children’s limited access to fresh water (one tap for both pre-primary and primary classes), little staff supervision during breaks when the children were very close to dangerous features of nature, and the teachers’ lack of focus on the children’s educational futures. Even though many parents in both countries perceived ECEC’s lack of an educational focus as careless, they also expressed the need to gain insight into the professionals’ perspectives:

I’m really wondering how they think about play and why it is so good for my son. I feel so helpless without knowing how they think. (MM8_N)

The next subtheme, safety, encompassed parental worries about potential accidents and injuries that (could) happen during play (in nature) or under a sleeping routine. These safety-related insecurities seem to worry the parents in both countries, and even more so if they were already unsure of whether the child was in a stimulating learning environment: ‘I already gave up the hope that he would learn something here, but please at least take care of him here! [laughter]’ (RM9_T). Apart from her giving up on the quality of education, we also read in this mother’s utterance that if the staff succeeded in explaining how play-based learning was happening, she would have been more understanding of the eventual accidents and injuries.

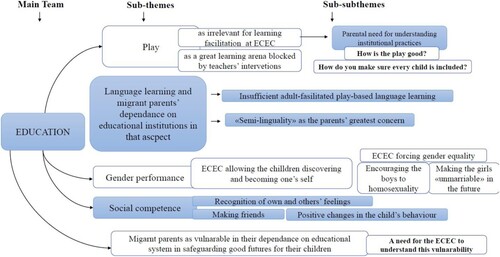

Education

As shown in , the theme of education was generally (both by migrant parents encountering the Norwegian and Tanzanian ECECs) understood as opposite to play and seen as a limitation of the children’s learning opportunities. As one father put it,

Let me tell you something, mister researcher: in our homes, play is everywhere. Children can play anytime. We send them to school to ensure that they learn the necessary skills that they cannot otherwise learn at home. However, in this school, children spend a lot of time playing outside their classrooms or singing and dancing in the classroom. How is this good? (RF8_T)

In the research material from both Tanzania and Norway, parents recognised play as a legitimate institutional practice and learning arena for the children, one that was particularly relevant to the development of essential socio-emotional skills like enhancing and maintaining relationships and managing anger. These parents were more concerned about criteria for the adults’ interventions in children’s play, or about their children not engaging in the play (the main and most developmental activity). What the parents in both countries had in common was a lack of understanding of how the ECEC institutions understood, reflected over, and organised play for the children, and how they made sure that every child was included.

The need to know that the ECEC staff reflected on play and learning was strongly relevant to the next subtheme: language learning and migrant parents’ dependence on educational institutions. This subtheme encompassed parents’ shared concerns regarding the successful introduction of the children to the majority language, something that the migrant parents neither in Norway nor Tanzania could provide based on their own cultural resources. ‘What I really don’t want is for my child to struggle with the Norwegian language like I do’ (RM3_N), reported one parent, which was why observing language learning as progressing slowly, or that the child was ‘somewhere between Somali and Kiswahili’ (RF11_T) was the greatest parental concern. Similarly, the parents seem to appreciate the critical role of children’s mastery of the language of instruction. One of them revealed that ‘but I think teaching preschool children in language which they do not master is not fair’ (RF12_T). Further, this subtheme entails concerns about power relations and existing trust between ECEC service providers and immigrant parents. For instance, an immigrant father in Tanzania said ‘but I think we (immigrant parents?) do not have much say in what children are learning and I don’t think we need to as long as experts are there, we need to just trust them’ (RF13_T).

In contrast, the subthemes on developing social competence and making friends were valued very positively in both countries, both in terms of changes in the child’s behaviour and in supporting relationships and networks that could contribute to the child’s more natural language development and thus well-being. Nevertheless, regardless of the positive perception of social competence, some parents (both in Tanzania and Norway) expressed their concerns regarding gender socialisation that was perceived as too equal rights-oriented, resulting in their daughters becoming too independent for marriage and female duties in the community, or their sons being encouraged to engage in homosexuality. More liberal parents, however, were appreciative of the ECEC’s attitude of allowing the child to create one’s self, including their gender orientation. Knowing how ECEC perceives and works with gender is a product of good conversations, in which these aspects of practice are explained to the caregivers:

It was such a relief hearing that they recognised him crying on long trips in the cold and rain. He is so delicate … I’m glad he can be himself, and that no one forces him to be tough and pretend all is great. (MM14_N)

Discussion

Our findings confirm the existing reports of im/migrant parents’ experiences, particularly Tobin’s (Citation2020) conclusion regarding im/migrant parents’ very pragmatic expectations of ECEC services as originating from their great dependence on educational systems to provide good futures for their children. Many of the parents participating in our study were aware of the limits of their own cultural capital and would agree with Tobin, Arzubiaga, and Adair (Citation2013) and Tobin (Citation2020), who showed that im/migrant parents’ understanding of ECEC is based on the values and logics from other socio-cultural contexts and further supported by gossip and knowledge spread among im/migrant communities. Many of the parents participating in our study saw this as their own weakness in contact with the ECECs of their children, which is why they expressed a need to understand the pedagogy and other diverse aspects of the institutional practices.

These basic needs of the im/migrant parents may be related to the empowerment strategy, which starts with equipping for inclusion (Fenech and Skattebol Citation2021). In this case, equipping for change would involve addressing the parental need for information and providing a responsive explanation of the ECEC practices. However, the culturally responsive explanation of the ECEC pedagogies needs to be preceded by the staff’s deep reflection on their own practice – a reflection that takes departure from other perspectives that challenge the unquestionable obviosity of existing practices and provide an explanation that would ‘talk’ to the parents. Only such a responsive explanation can encourage a dialogue (and open for disagreement). We argue thus for the acknowledgement of diverse/opposite parental perceptions as an important and legitimate base for the reflective PLCs.

‘Forcing’ oneself to perceive for ex. one’s own hygiene and nutrition routines from another cultural standpoint may help the ECECs to sympathise with the parents and more deeply understand their worries. For organisational and economic reasons, it is not always possible to improve certain hygiene standards, access to clean water, or nutrition. However, it is possible to acknowledge parental concerns, or even further, to join professional and parental forces and pressure local authorities (Epstein Citation2011) to provide better-quality water and nutrition for children. Another important dimension of PLC communication with parents could be about the providing parents with insights into meal situations that are unavailable for them. Explaining the meals as not nutrition, but also social settings (Ciren Citation2021; Sadownik Citation2022) that strengthen friendships and language development, and thus facilitate participation in more formal learning activities, could potentially extend parental perception of food at the kindergarten and respond to their concerns about the children’s learning. Analogically, and explanation of a ‘dirty child’ as not necessary a lack of care, but as symptom of the child’s intense exploration and learning could also potentially respond to the parental concerns.

Emphasising with the im/migrant parents in feeling totally dependent on the educational system for providing their children with a better future can stimulate a deep collective reflection on how to appropriately acknowledge, respect and respond to this vulnerability. ECEC staff confronting themselves in their own position of power, and their impact on the children’s futures, can facilitate deep professional, ethical, and intercultural reflection that affects daily practices in the ECEC institutions and provides reassuring ways of communicating these practices to the parents.

Imagining what it might be like not to understand or not being able to express oneself in the majority language may allow the PLC to understand the parental worries of their children never achieving ‘normal language development’. The PLC could then reconsider the ways in which they are facilitating language accusation and find a way to communicate changes in practices that would reassure the parents. The PLC may also work on strengthening the developmental opportunities for every child and safeguarding all children’s participation in play and other daily activities.

Knowing the different gender-related standpoints of the parents, the PLC is in a better position to reflect on more culturally/individually responsive argumentation for policy-imposed gender socialisation. An interesting potential for the PLC’s reflective work could be to confront the parental ambitions for the children (of all genders) with their rather conservative gender values (limiting educational opportunities of the girls). Respect for the family’s values, together with the ECEC service showing how gender equality relates to the full realisation of the developmental potential of the child, could thus create a communicative space for the parents and the ECEC teachers to (dis)agree.

Conclusions

The existing knowledge of migrant parents’ experiences of ECEC can, in our view, inform the PLCs’ critical interrogation of their own practices and improve the development of culturally sensitive and responsive ways of communicating these practices to parents. The responsively communicated information can encourage further dialogue and the negotiation of practices, as well as joining of forces, to strive for better conditions for ECEC facilities. This will say that through the reflective work of PLCs can facilitate parental involvement of all parents, regardless their background, in alignment with the ECEC policies of Tanzania, Norway and majority of the countries worldwide. However, the greater challenge lies in safeguarding the economic, structural and political conditions necessary for the functioning of PLC’s work in ECECs settings across various regions of the world.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderstaf, S., R. Lecusay, and M. Nilsson. 2021. “‘Sometimes We Have to Clash’: How Preschool Teachers in Sweden Engage with Dilemmas Arising From Cultural Diversity and Value Differences.” Intercultural Education (London, England) 32 (3): 296–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2021.1878112.

- Bennet, J. 2010. “Pedagogy in Early Childhood Services with Special Reference to Nordic Approaches.” Psychological Science and Education 3: 16–21.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Ciren, B. 2021. “Food and Meal Policies and Guidelines in Kindergartens in Norway and China: A Comparative Analysis.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 29 (4): 601–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2021.1941170.

- Crosnoe, R. 2007. “Early Child Care and the School Readiness of Children from Mexican Immigrant Families.” International Migration Review 41 (1): 152–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2007.00060.x.

- De Gioia, K. 2015. “Immigrant and Refugee Mothers’ Experiences of the Transition Into Childcare: A Case Study.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 23 (5): 662–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2014.970854.

- Epstein, J. 2011. School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Preparing Educators and Improving Schools (2nd ed.). Boulder: Westview Press.

- Fenech, M., and J. Skattebol. 2021. “Supporting the Inclusion of low-Income Families in Early Childhood Education: An Exploration of Approaches Through a Social Justice Lens.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 25 (9): 1042–1060. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1597929.

- Gapany, D., M. Murukun, J. Goveas, J. Dhurrkay, V. Burarrwanga, and J. Page. 2022. “Empowering Aboriginal Families as Their Children’s First Teachers of Cultural Knowledge, Languages and Identity at Galiwin’ku FaFT Playgroup.” Australian Journal of Early Childhood 47 (1): 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/18369391211038978.

- Garvis, S., S. Phillipson, H. Harju-Luukkainen, and A. R. Sadownik. 2022. Parental Engagement and Early Childhood Education Around the World. London: Routledge.

- Gedal Douglass, A., K. M. Roche, K. Lavin, S. R. Ghazarian, and D. F. Perry. 2021. “Longitudinal Parenting Pathways Linking Early Head Start and Kindergarten Readiness.” Early Child Development and Care 191 (16): 2570–2589. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1725498.

- Glasser, V. 2018. Foreldresamarbeid. Barnehagen i et Mangfoldig Samfunn. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Hornby, G. 2011. Parental Involvement in Childhood Education: Building Effective School-Family Partnerships. New York: Springer.

- Hryniewicz, L., and P. Luff. 2020. Partnership with Parents in Early Childhood Settings. London: Taylor & Francis Group.

- Hujala, E., L. Turja, M. F. Gaspar, M. Veisson, and M. Waniganayake. 2009. “Perspectives of Early Childhood Teachers on Parent–Teacher Partnerships in Five European Countries.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 17 (1): 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930802689046.

- Janssen, J., and M. Vandenbroeck. 2018. “(De)constructing Parental Involvement in Early Childhood Curricular Frameworks.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 26 (6): 813–832. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2018.1533703.

- Kvale, S. 2007. “Domination Through Interviews and Dialogues.” In Livshistorieforskning og kvalitative interview, 198–221. Viborg: Forlaget PUC.

- Kvale, S. 2008. Doing Interviews. London: SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849208963.

- Lastikka, A.-L., and L. Lipponen. 2016. “Immigrant Parents’ Perspectives on Early Childhood Education and Care Practices in the Finnish Multicultural Context.” International Journal of Multicultural Education 18 (3): 75–94. https://doi.org/10.18251/ijme.v18i3.1221.

- Leareau, A., and E. McNamara Horvat. 1999. “Moments of Social Inclusion and Exclusion Race, Class, and Cultural Capital in Family-School Relationships.” Sociology of Education 72 (1): 37–53. https://doi.org/10.2307/2673185.

- Little, J. W., and I. S. Horn. 2007. “‘Normalizing’ Problems of Practice: Converting Routine Conversation Into a Resource for Learning in Professional Communities.” In Professional Learning Communities: Divergence, Depth and Dilemmas, edited by L. Stoll, and K. Seashore Louis, 79–92. Maidenhead: McGraw Hill Open University Press.

- Ministry of Education, Science and Technology - MoEST. 2016. Pre-primary and Early Grades Curriculum. Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Institute of Education.

- Ministry of Education, Science and Technology - MoEST. 2021. Basic Education Statistics in Tanzania. Dar Es Salaam: Government Publication.

- Morrow, G., and N. Malin. 2004. “Parents and Professionals Working Together: Turning the Rhetoric into Reality.” Early Years 24 (2): 163–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/0957514032000733019.

- Nagel, N. G., and J. G. Wells. 2009. “Honoring Family and Culture: Learning from New Zealand.” YC Young Children 64 (5): 40–44.

- New, R. S., B. L. Mallory, and S. Mantovani. 2000. “Cultural Images of Children, Parents and Professionals: Italian Interpretations of Home-School Relationships.” Early Education & Development 11 (5): 597–616. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15566935eed1105_4.

- Sadownik, A. 2022. “Narrative Inquiry as an Arena for (Polish) Caregivers’ Retelling and re-Experiencing of Norwegian Kindergarten.” Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education 6 (1), https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.4503.

- Sadownik, A. R., A. G. Sulen, and B. R. Hansen. 2022. “Kollektive Læringsprosesser i de Daglige Møtene med Foreldre.” In Barnehagelæreren som Medforsker – en Arbeidsbok for Utvikling i Barnehagen, edited by J. Birkeland, Ø Glosvik, M. Oen, and E. E. Ødegaard, 146–170. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Sadownik, A. R., and A. Visnjić Jevtić. 2020. (Re)theorising More-Than-parental Involvement in Early Childhood Education and Care (1st ed., Vol. 40). Cham: Springer.

- Sharmahd, N., J. Peeters, K. Van Laere, T. Vonta, C. De Kimpe, S. Brajković, L. Contini, and D. Giovannini. 2017. Transforming European ECEC Services and Primary Schools Into Professional Learning Communities: Drivers, Barriers and Ways Forward. NESET II Report. Luxemburg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://nesetweb.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/AR2__2017.pdf.

- Solberg, J. 2018. “Kindergarten Practice: The Situated Socialization of Minority Parents.” Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE) 2 (1): 39–54. https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.2238.

- Sønsthagen, A. G. 2020. “Early Childcare as Arenas of Inclusion: The Contribution of Staff to Recognising Parents with Refugee Backgrounds as Significant Stakeholders.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 28 (3): 304–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2020.1755486.

- Statistics Norway. 2022, March 3. Kindergartens. https://www.ssb.no/utdanning/barnehager/statistikk/barnehager.

- Taylor, L. K., J. K. Bernhard, S. Garg, and J. Cummins. 2008. “Affirming Plural Belonging: Building on Students’ Family-Based Cultural and Linguistic Capital Through Multiliteracies Pedagogy.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 8 (3): 269–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798408096481.

- Tobin, J. J. 2020. “Addressing the Needs of Children of Immigrants and Refugee Families in Contemporary ECEC Settings: Findings and Implications from the Children Crossing Borders Study.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 28 (1): 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2020.1707359.

- Tobin, J. J., A. E. Arzubiaga, and J. K. Adair. 2013. Children Crossing Borders: Immigrant Parent and Teacher Perspectives on Preschool. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Utdanningsdirektoratet - UDIR. 2017, January 8. “Framework Plan for Kindergartens.” Content and Tasks. https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/barnehage/rammeplan/framework-plan-for-kindergartens2-2017.pdf.

- Vandenbroeck, M. 2009. “Let Us Disagree.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 17 (2): 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930902951288.

- Van Laere, K., and M. Vandenbroeck. 2017. “Early Learning in Preschool: Meaningful and Inclusive for all? Exploring Perspectives of Migrant Parents and Staff.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 25 (2): 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2017.1288017.

- Van Laere, K., M. Van Houtte, and M. Vandenbroeck. 2018. “Would it Really Matter? The Democratic and Caring Deficit in ‘Parental Involvement’.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 26 (2): 187–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2018.1441999.

- Vuorinen, T. 2018. “‘Remote Parenting’: Parents’ Perspectives on, and Experiences of, Home and Preschool Collaboration.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 26 (2): 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2018.1442005.