Abstract

This research investigates the state of student participation in the Eco-Schools programme in two selected secondary schools located in Spain and the Netherlands. The focus is on understanding the levers of student participation and of the factors leading to a whole-school approach. Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model is used as an analytical framework. The study also reflects on the merits and shortcomings of this framework. The analysis of the two cases revealed contradictions in the intended effect of the Eco-School programme on fostering student-led change towards sustainability and a whole-school approach. The research suggests that student participation in Eco-School programme can be fostered by using an activity-based ‘whole institution’ approach that interlinks a reflective and action-based procedure, by adapting the students’ learning environment according to their needs and capabilities, by providing for close teacher guidance in Eco-School activities and establishing good student-teacher-relationships, and, finally, by incorporating the Eco-School programme into the school’s overall educational framework.

Introduction

The Earth has entered a critical era – the Anthropocene, where the impact of the human being is more visible than ever leading to a wide range of urgent interlinked sustainability challenges globally such as: climate change, massive biodiversity loss, food and water security, etc. All those challenges are characterised by their systemic nature, high uncertainty, and contested scientific knowledge and by causes that are deeply grounded in our current values, mind-sets, and corresponding ways of living (Wals and Corcoran Citation2012). Essential changes in all areas of current human practices, such as economic production, consumption, and governance operations, are needed in order to enable more sustainable ways of living (Mogensen and Mayer Citation2005; Corcoran, Weakland, and Wals Citation2017). Young people thereby play a very crucial role in this transformation process since eventually they will become leaders and shapers of the world (Arnold, Cohen, et al. Citation2009; Hickman and Riemer Citation2016).

Current learning and teaching practices within the contemporary school system have been criticized for insufficiently preparing and motivating young people to engage with today’s urgent sustainability challenges (Wals and Corcoran Citation2012). As a contemporary environmental educational approach, Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) therefore aims to develop people’s willingness, commitment, and qualities in order to make a change upon existing structures for a more sustainable future. Those qualities include skills and competences, such as critical and systemic thinking, creativity, reflexivity and empathy, that enables people to make their own informed judgements and reasonable decisions on how to act on sustainability issues, which eventually might lead them to a more caring attitude towards their environment and ultimately to the adaption of more sustainable lifestyles (Corcoran, Weakland, and Wals Citation2017; Schusler, Krasny, and Decker Citation2017; Krasny Citation2020). ESD thereby aims to establish a feeling of global social responsibility towards those issues and an awareness of how actions of today affect future generations (Van Poeck and Vandenabeele Citation2014). Within ESD the focus often lies on student-centred, interactive, and inquiry-based approaches to learning and teaching as well as on the transformation of schools into places where interaction and joint learning between the school and local community members can flourish. This flourishing includes the kindling collectively motivated action towards sustainability within their local environment (Jensen and Schnack Citation1997; Tilbury and Wortman Citation2005; Mogensen and Schnack Citation2010; Hedefalk, Almqvist, and Lidar Citation2014; Hofman Citation2015).

One topical pedagogy within ESD that resonates strongly with the reorientation described above, is the ‘whole-school approach’, which emerged during the 1990s. Having multiple interpretations and ways of implementation, this approach generally aims to create a holistic learning environment by reorienting the school’s conventional functionality, including its infrastructure, management, resource consumption, curriculum, purpose of learning, teaching and extracurricular activities towards sustainability. It thereby seeks to enhance students’ learning opportunities by actively making practice-based improvements in their own environment (Mogren, Gericke & Scherp Citation2019; Mogren Citation2019). In this approach, students are seen as the main mediators of social change and it is assumed that their competences and capacities enlarge when they are enabled to assume their own responsibilities as change agents to find their own appropriate solutions for sustainability issues in their surroundings (Henderson and Tilbury Citation2004; Tilbury and Wortman Citation2005; Hargreaves Citation2008; Reid, et al. Citation2008; Mathar Citation2014). In this way, participation and democratic action are considered central elements within whole-school approaches (Shallcross and Robinson Citation2008). By involving students more actively into school processes they are more likely to become immersed in learning experiences that can help them transform into responsible citizens that are able to bring about change and to cope with sustainability issues in a democratic way (Mogensen and Mayer Citation2005; Reid et al. Citation2008).

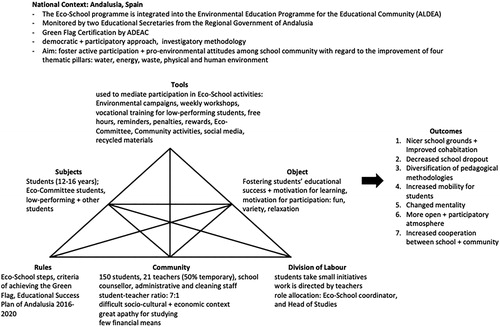

Among the various international whole-school initiatives is the Eco-Schools programme. Established by the Foundation for Environmental Education (FEE) in 1992, the programme now represents the largest international network of students and teachers. Eco-Schools claims that their programme has been implemented in 59,000 schools in more than 68 countries (Eco-Schools 2020). The Eco-Schools programme has been recognised by the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (DESD) (2005–2014) and by UNEP as a model programme for ESD (Eco-Schools Citation2017a, Citation2017b). In the Eco-Schools programme, a whole-school approach is supposed to be created by applying a Seven Steps Framework () and various Eco-School Themes which can vary from country to country and also within countries. (Eco-Schools Citation2017b). Students are positioned as the main protagonists in the Eco-Schools programme. They are in charge of steering the Eco-Committee (EC) at their school and are included into decision-making processes on how to deal with certain sustainability issues within their environment (Mogensen and Mayer Citation2005; Eco-Schools Citation2017b). Eco-Schools assumes that students feel empowered and/or can become empowered by tackling of environmental matters that lead to improvements that they can attribute to their own actions. One of the main goals of the Eco-Schools programme is to involve everyone in the school community by working, as much as is possible, on locally relevant issues at the interface of school, environment, and community. Schools are entitled to receive the Green Flag for good practices of the Eco-Schools programme. Every participating country has one national operator organisation who cooperates with FEE and who is responsible for the implementation, monitoring, and certification of the Eco-Schools programme at the specific country (Eco-Schools Citation2017b). However, the implementation varies greatly among the different countries, from light green ad-hoc project and environmental management-oriented approaches to dark green more systemic integrative approaches (Goldman et al. Citation2018).

Figure 1. The Seven Step Framework of the Eco-Schools Programme (based on source: Eco-Schools Citation2017a). It starts with the formation of an Eco-Committee, consisting of various members from the school community which is responsible for all the conduction of all steps shown. In all of the seven steps, students play the main role in their execution and the development of actions and activities.

A vast amount of research in various countries and contexts exists that investigated the impact and influences of the Eco-School programme on students.

In their study, Krnel and Naglic (Citation2009) investigated the level of environmental literacy among students from Eco- and ordinary schools in Slovenia. It revealed that Eco-School students possessed a slightly higher level of environmental knowledge. However, their environmental attitude and behaviour remained unchanged. In Flanders, more than 100 Eco-Schools were surveyed on the effect of students concerning their environmental knowledge, attitude and behaviour in two studies from Boeve-de Pauw and Van Petegem (2011, 2013). Their study demonstrated similar results in a way that Eco-School students demonstrated an increase in environmental knowledge, but the programme had no influence on their attitudes and behaviour. Also other studies that compared environmental knowledge, attitudes and behaviour of students from schools that participate in ESD programmes to students from schools that did not participate in such programmes suggest that the influence of those programmes rather lies in cognitive outcomes within students (Hallfredsdóttir Citation2011; Berglund, Gericke, Chang Rundgren Citation2014; Olsson, Gericke, Chang Rundgren Citation2016; Boeve-de Pauw and Van Petegem 2017; Lace-Jeruma and Birzina Citation2019; Olsson, Gericke, Boeve-de Pauw, Berglund, Chang Citation2019).

Based on these results the question arises why the programme could not motivate or engage those students to actively participate in their environment in order to become “change agents,” demonstrating all the desired outcomes, including increased environmental attitude and behaviour. In their research, Cincera and Maskova (Citation2011) did demonstrate that the lack of impact of the examined environmental education programme was related to issues with the implementation of the programme in the investigated schools and changes with regard to implementation of the programme were recommended. This suggests that the disappointing impact of school-based environmental education programs like Eco-Schools and other programmes are likely related to their implementation and enactment. The current Seven Step Framework might be sound on paper but when implemented does not necessarily provide adequate conditions for students to develop further non-cognitive features and might not lead into a whole-school approach.

Studies that investigated the implementation processes within schools participating in the Eco-School programme revealed several factors crucial for boosting students’ motivation to participate in environmental activities and for creating a whole-school approach. A study conducted by Cincera and Krajhanzl (Citation2013) showed that the students’ “perceived participation in decision-making processes at the school” (p. 117) was the most important factor that was linked with students’ action competence and the programme’s success. Another study by Cincera et al. (Citation2019) that focused on implementation strategies, confirmed the relevance of the students’ perceived participation for the success of the programme. Gan et al. (Citation2019) compared the implementation of the Eco-School programme in Hungary and in Israel and highlighted the importance of the commitment and dedication of the teaching staff and the principal for the success of the programme. Boeve-de Pauw et al. (Citation2015) showed the effect of different pedagogical approaches in Swedish schools. More frequent sustainability behaviour was noticed among students from schools where a more pluralistic approach has been put into practice. Another study in Flanders by Boeve-de Pauw and Van Petegem (Citation2017) investigating factors that promote learning outcomes, underlined the importance of a school’s policy making capacities, didactical approaches and the use of natural elements at school in strengthening the impact of the programme on the students’ behaviour in the long-term.

This paper wants to add to the body of Eco-School literature with a two-fold purpose. In the first place, this paper aims to empirically compare the state of student participation in two Eco-Schools. The focus is on understanding the levers of student participation and of additional factors that support the development of a whole-school approach and contribute to a more successful implementation of the programme.

Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model was identified as an analytical tool in conduction the research. This model is characterized by a basic activity system triangle model and seems particularly suitable when trying to analyse and understand student participation in Eco-School activities in its systemic learning environment and socio-cultural context (see the next section). A secondary objective of this study is to critically reflect on the utility of the model in conceptualizing, analysing and illustrating the Eco-Schools programme’s impact or influence on student participation.

Materials and methods

Conceptual framework

In this research, Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model (Engeström Citation1987) was applied as both a conceptual and analytical framework. Through its application certain contradictions and tensions in the two Eco-School approaches in this paper could be revealed, which can be used as a source of innovation and improvement of the Eco-School programme. Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model is based on Cultural-Historical Activity Theory (CHAT), which is an analytical and methodological approach for understanding and describing complex human activities in processes of learning within their socio-cultural contexts (Jonassen and Rohrer-Murphy Citation1999; Engeström Citation2000; Yamagata-Lynch Citation2010).

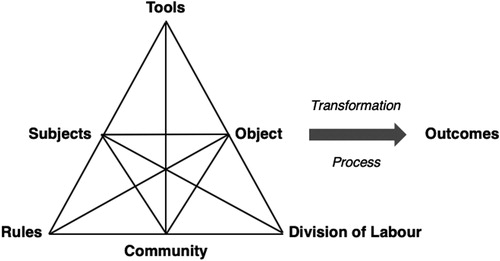

Engeström’s model incorporates interacting entities, such as Subject, Object, and Community, and mediating components of human activity, including Tools, Rules and the Division of Labour. It consists of two parts and can be visualised in a triangle diagram (see ). The upper part of the triangle diagram represents Vygotsky’s concept of ‘mediated action,’ which depicts the interaction of an individual (Subject) with the environment (Object) through tool mediation. The lower part (Rules, Community, Division of Labour) represents Leontiev’s concept of ‘collective object-oriented activity,’ which provides a collective or societal dimension. Thus, the Object incorporates multiple individual goals, which motivate individual actions, but which may differ from the overall motive (= social need1) (Yamagata-Lynch Citation2010; Silo Citation2011; Blunden Citation2015). Therefore, an activity system is a many-voiced construction where different perspectives of the diverse participants are incorporated. The whole activity leads to an Outcome, which represents the changed situation of all components due to the activity (ibid.).

Figure 2. Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model (Engeström Citation1987) (based on source: Mwanza Citation2001). It demonstrates human activity in its socio-cultural context.

The activity systems model maps the interaction between individuals and their environment as well as their interrelationships. Thereby, all components in the activity systems model are in a direct dialectic relationship to each other, meaning each component influences the activity and the interactions between the other components. When a component changes, different structural tensions and contradictions within the activity system, that can enable or constrain the attainment of the object, arise (Engeström Citation1987; Yamagata-Lynch Citation2010; Silo Citation2011). Primary and secondary contradictions are contradictions that occur within each and between different components of the activity system accordingly. Tertiary contradictions refer to tensions between the object/motive of the activity system’s dominating mode and its “culturally more advanced form” (Engeström Citation1987, p. 103), which represents the ‘object motive’ or the ideal mode of an activity. Contradictions can grow and accumulate and ultimately function as sources of innovative change for the system due to their capability to trigger learning processes (Engeström Citation2000; Yamagata-Lynch Citation2010; Silo Citation2011). Due to internal contradictions every component within the activity systems model is experiencing constant transformative change, which changes the activity. Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model therefore depicts the current status of an activity. Tools have a particular importance in the activity since they co-construct the ways in which humans interact with reality and link the activity with its socio-cultural context (Mwanza Citation2002; Silo Citation2011).

The conceptual framework was further operationalised using Mwanza’s (Citation2001) Eight Step Model, which enabled the creation of thematic categories for the data collection process through its open-ended questions (please refer to Appendix 1). During and after data collection and analysis, the themes of the components of Engeström’s model were fine-tuned. Furthermore, a 9th component was added, to recognize the broader context (here: national context) in which the activity system is embedded.

Research questions

This research pursues the following research questions:

How are students participating in the Eco-School approaches in the two examined schools?

What contradictions and tensions, in terms of CHAT, arise from the Eco-School approaches at the schools?

Which factors can be revealed that promote a whole-school approach of the Eco-School programme?

What are the benefits of using Engeström’s Second Generation Activity System to analyse student participation in Eco-School activities?

Research methodology

This research used a qualitative research methodology with a case study design. The research methodological procedures were mainly derived from the following authors: Mack et al. (Citation2005); Yamagata-Lynch (Citation2010); Kumar (Citation2011); Green and Thorogood (Citation2014); Punch and Oancea (Citation2014). In this research, one case in Spain and one case in the Netherlands were chosen to study two distinct cases of student participation in the Eco-School programme. The CHAT framework thereby is said to be very compatible to case study research since it helps to set boundaries for the case through the set of components of CHAT (Yamagata-Lynch Citation2010).

Study cases selection

Cases were selected that significantly diverged in school situation and socio-economic context. Given the practical constraints of research time, budget and the researcher’s language skills, schools were sought in the Netherlands and Spain. Two specific study cases were chosen in consultation with the national operators of the Eco-School programme in Spain (ADEAC) and in the Netherlands (SME Advies) according to the following criteria: The school should 1) be a secondary education institute, 2) have some experience with the Eco-School programme in the sense that the school should have participated in the programme for some years, 3) have a good implementation of the Eco-School programme according to the national operators. For data protection reasons the names of the two selected schools have been anonymized and are further referred to as “School 1” (Spain) and “School 2” (Netherlands). Both selected schools have been participating in the Eco-School programme since the school year 2013/14 and were awarded with their first Green Flag in April 2017 (School 1) and September 2016 (School 2). School 1 has thereby been recognised as pioneers within Andalusia with regard to their programme implementation and School 2 has been chosen from a pool of various suitable options according to the given criteria.

Data collection methods

Multiple qualitative data collection methods were applied in order to collect a broad range of qualitative data (please refer to Appendix 2 in the appendices). As primary data source collection semi-structured interviews and observations were conducted during five-days-visits at each school.

Purposive and snowball sampling was applied for selecting relevant interviewees. In both schools, most interviewees were recruited by the Eco-School coordinators. This method was chosen, since the coordinators knew best who was involved in the Eco-School programme at the school in order to obtain appropriate data for this research. Convenience sampling was applied for selecting interviewees within the school community members that were not very much involved in the Eco-School programme in order to gain a full range of information. Almost all interviews were recorded and notes were made on the characteristics of the interviewee and atmosphere while interviewing. Unrecorded interviews were captured through notes. Interviews were conducted with school community members as well as with FEE and national operating organisations (ADEAC, SME Advies). In School 1, 20 recorded (in sum: around 8 h) and 2 non-recorded interviews were conducted. Interviewees included Eco-Committee participants (5), other students that participate actively in Eco-School activities (8), Eco-School coordinator, head of studies, school counsellor, school principal, two other teachers, and one parent, which has been part of the Eco-Committee. In School 2, 10 recorded (in sum: around 5 h) and 6 non-recorded interviews were performed. The former included interviews with Eco-Committee students (5), Eco-Committee teachers (3), one other teacher from the school community as well as the school principal. The latter included conversations with one teacher and with five groups of students at the entrance hall during lunch break. Interviews were conducted in Spanish (School 1), English and Dutch (School 2). Open-ended questions for the interviews were derived from the theme categories formed when operationalising the conceptual framework.

Observations were recorded in forms of notes and photos and included non-participant and participant observation of e.g.school infrastructure, formal and informal gatherings, school breaks, and meetings with the Eco-Committee. In all schools, a tour around the school was given by either the Eco-School coordinator (School 1) or by Eco-Committee students (School 2). Following Glesne’s (Citation2005) participant-observer continuum an observer perspective was chosen when participating in activities in the visited schools in order to keep a certain objectivity and neutrality for data collection.

Secondary data source collection included the analysis of school and policy documents, and the schools’ social media websites, which was conducted before and after the school visits. School and policy documents served to receive information about the general schooling environment and the context. Social media were searched for information on the Eco-School programme in that specific school.

Data analysis

The data analysis combined Activity Systems Analysis (ASA) as outlined in Yamagata-Lynch (Citation2010) with thematic content analysis (Green and Thorogood (Citation2014)). Before data were analysed, all qualitative data were prepared. Interview recordings were listened to again and transcribed verbatim. Information from documents and social media as well as from observation materials and field notes were summarized. This research didn’t make use of any data analysis programme, but data was coded and organised manually on paper. Interviewees were given numbers and letters when their statements were coded. Data were coded horizontally in a deductive way (ASA) categorizing them according to the pre-defined main concepts of Engeström’s Second Generation Activity System and vertically in an inductive way within the main concepts following a thematic content analysis in order to form themes within each concept. Through the operationalisation of Engeström’s Second Generation Activity System using Mwanza (Citation2001)’s Eight Step Framework, the main concepts were already pre-defined. However, they needed to be adapted after fieldwork completion as well as during data analysis. The changes made within each component are further outlined in Appendix 1.

Interview data represented most of the data collected and were therefore used the most for the analysis. During the whole data analysis procedure, an analytical memo was kept in order to record ideas. Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Models were constructed to characterize and compare the situation of student participation in the Eco-School programme as well as the constitution of the students’ learning environment in both school contexts. Since in this research one central activity system was applied only emerging primary, secondary, and tertiary contradictions could be analysed (please refer to the section “Conceptual Framework” for an explanation of the term “contradiction”). Contradictions were analysed according to how tools, prevailing rules, and the division of labour mediated towards the object (secondary contradictions) and how the attained object in the examined Eco-Schools correlates with FEE’s interpretation and expectations of the Eco-School programme (tertiary contradictions).

Results

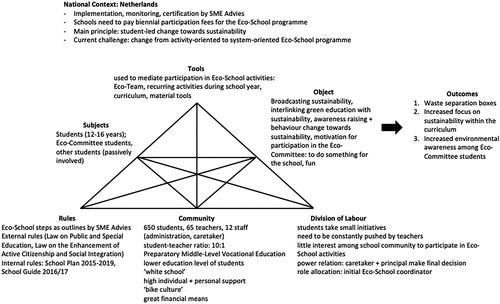

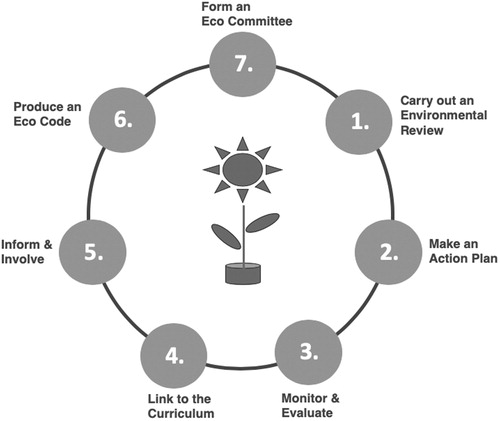

The following section is divided in three subsections. The first subsection presents the analysed state of student participation in School 1 and School 2 in a comparative manner by means of Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model. Discovered contradictions in both activity systems are outlined in the second subsection. At last, identified components that are conducive for student participation in Eco-School activities are elaborated and discussed.

The state of student participation in school 1 and 2

National context - implementation of the Eco-School programme

The implementation of the Eco-School programme varies greatly among regions and both schools therefore demonstrated different forms of implementation.

The Eco-School programme in Andalusia, Spain, followed a rather institutionalized form. Here, the programme is directed by the Ministry of Education (Consejería de Educación) in collaboration with the Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning (Consejería del Medio Ambiente y Ordenación del Territorio) and is integrated into the Environmental Education Programme for the Educational Community ALDEA (Programa de Educación Ambiental para la Comunidad Educativa). The latter belongs to a range of various educational programmes that are offered by the Regional Government of Andalusia to schools in that region in order to diversify and individualise their educational activities according to local needs and interests (RGA Citation2016d). The interview with the national operator of the programme (ADEAC), who is responsible for the handover of the Green Flag, revealed that the focus of the Eco-School programme is especially about citizenship, values education and the motivation of students to participate in urgent sustainability issues of this century, such as climate change, biodiversity loss, etc. The programme composes water, energy, waste, and physical and human environment as thematic pillars.

In the Netherlands, the Eco-School programme is offered by a consultancy organisation SME Advies against the payment of a biennial participation fee. SME Advies is responsible for the coordination, facilitation, and certification of the Eco-School programme. According to SME Advies, the main principle of the programme is student-led change towards sustainability. Through an investigatory methodology, students need to find solutions for different sustainability themes at their school in line with the school’s possibilities. On average, the Green Flag is granted after two years of participation in the Eco-School programme and a re-evaluation is conducted every two years (Eco-SchoolsNL Citation2017). As the interview with SME Advies revealed most Eco-Schools follow an activity-oriented approach. It poses a challenge to bring them to a system-oriented level.

Rules

In Andalusia, participating schools need to follow specific steps that are fixed to certain timelines. Instructions and didactical materials are provided by the Regional Government of Andalusia and ADEAC. According to Eco-School materials, an investigative methodology is pursued by the participating school: The Eco-Committee starts awareness raising activities about a determined environmental theme within the school. Eco-Audits are performed and propositions for improvement are given to the Eco-Committee, which elaborates the Action Plan and Eco-Code. The former needs to be included into the educational project of the school. An annual working plan is prepared by the Eco-School coordinator and teachers, which includes an analysis of the initial educational situation and a Specific (Environmental) Educational Project referring to educational objectives, activities, and monitoring measures (RAE Citation2015; RGA Citation2016b, Citation2016c, Citation2016d). Schools are granted pedagogical autonomy and are allowed to choose their own educational projects and methodology within the Educational Success Plan of Andalusia 2016–2020 (RGA Citation2016a). An overarching goal of this plan is to increase the number of students who successfully accomplish the Obligatory Secondary Education in Andalusia (ibid.).

According to materials from SME Advies, the methodology for the Eco-School programme is based on ISO 14001 – Environmental Management, which provides a framework for companies or organisations to reduce their environmental impact (Eco-SchoolsNL Citation2017). It includes the Seven-Step-Plan and Ten Themes (Waste & Resources, Communication, Energy, Building & Environment, Health & Hygiene, Green, Mobility, Safety & Citizenship, Food, and Water). The Eco-Committee develops an action plan for improving the specific theme after an Eco-Scan, monitors and evaluates the conducted actions. The theme is then integrated into the curriculum by participating teachers. At last, the wider school community is informed and motivated to create an Eco-Code. Dutch schools are granted freedom and autonomy with regard to their finance, pedagogies, didactics, and educational contents within their legal boundaries and in line with national quality standards according to the Law on Public and Special Education (Dutch Constitution, Article 23) (CIEB Citation2017). Furthermore, all schools in the Netherlands are obliged to enhance active citizenship and social integration within their educational practices and policies following the Law on the Enhancement of Active Citizenship and Social Integration (Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment Citation2014).

Community – social, geographic and educational setting

School 1 is located at the outskirts of a small village of around 3,200 inhabitants next to a natural park in the province of Huelva in Andalusia, Spain. The local population has been described by several interviewees as a largely low-qualified working class that mostly engages in seasonal and day labour work. The head of studies was indicating the difficult socio-cultural and economic circumstances that affect about 80% of the students’ families several times during the interview. The school counsellor stated that due to these circumstances every fourth student in Andalusia finishes the Obligatory Secondary Education without any degree. All interviewees described the school atmosphere as very good, familiar, open, and collaborative. There is a close relation between teachers, students, and the students’ families due to the very small and familiar environment. Observation data revealed a colourful and handcrafted decoration of the interior part of the school building.

School 2 is located in ‘s-Hertogenbosch – a city of 150,000 inhabitants in the province of North Brabant of the Netherlands. According to the Study Coordinator, School 2 provides a ‘Preparatory Middle-Level Vocational Education’ (Voorbereidend Middelbaar BeroepsOnderwijs, VMBO) for students between 12 and 16 years with lower education levels. It offers practical ‘Green Education’ subjects like Animal Care, Nutrition, Outdoor Recreation, Flower or Greenery. Observation data revealed an open and joyful atmosphere of the school building. A teacher indicated that the school building has been recently reconstructed while taking into consideration the school’s green and sustainable profiling. The school has a greenhouse, various vegetable patches and an animal stable for several animals. The relation between teachers and students has been described as good by all interviewed teachers. However, several students reported that bullying and conflict situations among students occur on a daily basis. One teacher described students as spoiled and selfish.

Subjects

The analysis of interview and observation data found that in School 1 almost every student participates in Eco-School activities since the Eco-School programme is integrated into the whole school. On the contrary, the Eco-School programme in School 2 constitutes a project within the school and therefore only a few students participate in the programme.

In School 1, participating students can be divided into four different groups: students involved in the Eco-Committee, students that actively participate in Eco-School activities during their free time or within the weekly workshop, low-performing students and other students from the school community. However, a student from year 4 mentioned that many students from her year could rarely participate due to high school preparation.

Subjects from School 2 mainly refer to students that participate in the Eco-Committee since other students are only passively involved in some activities within their curriculum or in recurring activities (see Tools). An Eco-Committee student from year 3 stated that year 4 was relatively inactive due to their preparation for the final exams.

Object

Both schools followed distinct goals and approaches for their educational activities as well as a different motivation to join the Eco-School programme. In School 1, the school principal, counsellor, and several teachers explained that the overall aim of this school is to foster the students’ educational success and personal development including their entrepreneurial and citizenship skills. This they realize through the participation in various educational programmes. The head of studies explained that School 1 has used the Eco-School programme as an overarching framework for its educational project since the school year 2015/16 when seeing the potential of the programme in improving the students’ motivation to participate in educational activities. This enabled to unify all co-existing educational programmes at School 1 and to build a new educational concept to improve the school’s functionality, learning environment, and pedagogical qualities while considering the students’ needs and interests. The Eco-School programme therefore seemed to constitute an integral part of School 1 and interviewed students demonstrated a high affection towards Eco-School activities stating that they would participate voluntarily in their free hours in painting or craft activities. The majority of the students interviewed explained their motivation due to entertainment and the provision of a playful variety to their traditional theoretical classes.

Materials from School 2 and an interview with a teacher revealed that School 2 emphasises personalised, experience-oriented, and entrepreneurial education inside and outside the school. Students thereby receive close personal guidance and individual support with regard to their educational activities and social environment. Furthermore, the principal stated that School 2 emphasizes interactive learning, teamwork and opportunities for students to make a meaningful contribution to their environment. The two teachers who are mainly responsible for the Eco-School programme at the school explained that the school’s motivation for participating in the Eco-School programme was to incorporate sustainability into the whole school. This should be thereby stimulated through the Eco-Committee. Achieving the second Green Flag constituted one of their main objectives besides further optimizing the school building and environment according to the school guide 2016/17. Several students interviewed explained their motivation for joining the Eco-Committee in enjoyment.

Tools

In both schools, students make use of a variety of tools to engage in Eco-School activities although the variety of tools seemed much bigger in School 1 than in School 2. In School 1, the Eco-School coordinator outlined that the Eco-School programme started with already previously designed environmental campaigns embedded in her natural sciences classes as a continuation of other environmental education programmes. Students are engaged in an investigatory process towards an environmental problem and guided towards conducts and actions, which they then present within the whole school community. Two Eco-School workshops are hold once per week, where students are engaged in different manual activities, such as making soap from recycled cooking oil, sowing plants in the greenhouse or doing wall paintings in the courtyard. Those workshops simultaneously form daily vocational-training-like educational activities for two groups of low-performing students as the head of studies and school counsellor stated.

The Eco-Committee of the school year 2016/17 from School 1 consisted of the Eco-School coordinator, head of studies, school counsellor, one administrative staff person, one parent that works at the local municipality, and seven students from all school years. The role of the Eco-Committee was perceived differently among interviewees. Eco-Committee students perceived their role as being internal supervisors of other students regarding the Eco-Code and as student representatives for external visitors or activities. Interviewed non-Eco-Committee students were uncertain about the actual role of the Eco-Committee. According to Eco-Committee adults, the Eco-Committee is responsible for the environmental campaigns’ organisation and evaluation, activity planning, the Action Plan’s and Eco-Audits’ evaluation, Eco-Code revision, and the assessment of the general process of the Eco-School programme.

Several interviewees reported that students are reminded and sometimes punished to comply with environmental conducts. However, they also stated that they are rewarded when bringing recyclable materials to their exams with extra points. According to the head of studies, School 1 holds a close collaboration with the local municipality, and other educational institutions and associations for the organisation of activities within the local community.

In School 2, interview material revealed that the main Eco-School activity constitutes the Eco-Committee, which consisted of one student from year 1, one student from year 2, three students from year 3, six students from year 4, five teachers, and one parent in the school year 2016/17. According to Eco-Committee members, the role of the Eco-Committee is to make the school more environmentally friendly and to raise awareness towards sustainability among students. Several Eco-Committee interviews stated that actions organised by the Eco-Committee within the last three school years included the installation of waste separation boxes, a competition for the design of the Eco-Code, and various recurring activities to raise awareness towards electricity use (Warm Sweater Day), water drinking (Water Challenge), and waste disposal (Clean-Up Day in the nearby neighbourhood). The latter are periodically organised by teachers and facilitated by Eco-Committee students. Observation data revealed that material tools used for activities are provided by private companies.

Division of labour

Both schools demonstrated different approaches with regard to their role allocation within the Eco-School programme as well as different dynamics within and between Eco-Committee members and the school community.

In School 1, several students stated that the election of Eco-Committee students in the school year 2016/17 was conducted through an election process in class to find the most ‘responsible’ student. The election process was guided by tutors as well as the Eco-School coordinator and the head of studies. Adult members of the Eco-Committee showed specific roles. According to interview material, the Eco-School coordinator and the head of studies are regarded as the main contact persons and final decision-makers with regard to Eco-School activities. They also guide the two Eco-School workshops and the two groups of low-performing students. The Eco-School coordinator thereby functions as the main responsible person regarding the process of the Eco-School programme and manages the school’s social media websites. She is also in charge in the supervision of correct waste separation and recycling practices within the school community. Being part of the management team, the head of studies is concerned of issues regarding school dropout and social relations at school. On site observations revealed a difference between Eco-Committee students and adults regarding their leadership of conversations as well as initiating actions. Several interviewees confirmed that until now students have contributed with rather small ideas within the Eco-School activities and are rather led by teachers in activities and conversations. However, the head of studies, the Eco-School coordinator and the school counsellor reported that they always motivate students to initiate something if it is feasible economically and spatially. However, it still constitutes a long-term goal to foster the students’ initiative-taking attitude.

In School 2, the five Eco-Committee teachers are engaged in integrating sustainability topics into the curriculum and to motivate other teachers to participate in the Eco-School programme according to the former Eco-School coordinator. However, two Eco-Committee teachers reported that it has been rather difficult to motivate other teachers to participate in the Eco-School programme since they show little interest. Eco-Committee students and teachers explained that the role of Eco-Committee teachers is to select students for the Eco-Committee according to their motivation and educational performance, and to guide students within the Eco-Committee. As interviews with Eco-Committee teachers demonstrated, most actions have been developed by the former Eco-School coordinator and Eco-Committee students have contributed with ideas within their theme groups but the realisation of those ideas has been difficult so far. Interview and observation data revealed that there is little interest among the school community towards the Eco-School programme and Eco-Committee activities were perceived as ‘boring’. During the interview, the former Eco-School coordinator pointed out that the Eco-Committee rather operates in the background of the school and that there is little communication between the Eco-Committee and other students.

Outcomes

The outcomes of School 1 and 2 demonstrate vast differences. School 1 shows a much wider range of positive outcomes than School 2 in terms of physical changes in the environment and behavioural changes within students related to the Eco-School programme.

Overall, the Eco-School programme in School 1 has contributed to a complete transformation of the school’s environment, including physical, social, and pedagogical changes. All interviewees confirmed that the participation in the Eco-School programme led to the creation of more pleasant school grounds. A student described:

“Before it looked like a prison, (…) there was only concrete, inside only brick. (…) now you enter the school and you see (…) the colours, the painted walls, the green house, in the classrooms you see everywhere more joy.”

The school also improved significantly at an ecological level. As the last Eco-Audit of 2017 demonstrated the school was able to reduce its electricity, water, and paper consumption by more than 50% in the last four years. Several interviewees indicated that the majority of students is behaving according to the Eco-Code and has internalised environmental habits into their homes. Furthermore, the principal and a teacher stated that a more participatory, open, and caring atmosphere has developed where students are given opportunities to play a more active role as school community members to care for their environment. The school counsellor stated:

“(…) they [the students] are part of the project and through this we achieve that this school converts into their school”.

Several interviewees reported that through the diversification of pedagogical methodologies, the enthusiasm for educational activities among students significantly improved. According to the head of studies, the early school dropout2 decreased from 20% to 2% within the last four years since participating in the Eco-School programme and the school was honoured for this achievement with a regional price.

As already mentioned before, School 2 demonstrated much fewer outcomes than School 1. According to interview data from School 2 new waste separation boxes had been established, which has been a joined effort between the Eco-Committee and the school management. According to various teacher interviewees students have been learning about diverse sustainability-related topics due to an increased attention towards sustainability within the curriculum through the Eco-School programme. However, the environmental awareness only increased among Eco-Committee students as several interviewees reported. Despite those achieved outcomes mentioned, all adult interviewees stated that more efforts need to be made to change the school community’s mind-set towards sustainability. As the school principal noted:

“I think we can do much more. When I see how students sometimes leave the classroom, all the rubbish on the ground… That is a wrong mind-set of children. (…) Often we have the windows open and the heating on.”

The situation of student participation in each school is visually summarized by means of Engeström's Second Generation Activity Systems Model in and .

Contradictions in both activity systems

Several contradictions have been discovered from the analysis of the two activity systems regarding the situation of student participation in the Eco-School programme at both schools. As already outlined in the section Conceptual Framework, contradictions and tensions are sources of innovative change and improvement and can lead to learning processes.

The analysis of both cases demonstrated that following the current Seven-Step-Framework did not result into the occurrence of the expected student-led version of the Eco-School programme. In terms of CHAT, this could be characterized as a tertiary contradiction in both activity systems. Neither School 1 nor School 2 demonstrated the expected picture of students, as a ‘driving force’ of the Eco-School programme, leading the Eco-Committee on democratic principles in order to develop conscious actions for improving their environment towards sustainability but rather a picture of students being engaged into teacher-led activities and initiatives. This contradicts with the general expectation of FEE’s Eco-School programme of being an opportunity for students to experience student-led change towards sustainability and feelings of achievement and empowerment when seeing tangible outcomes of their own actions.

In School 1, secondary contradictions existed between Rules, Tools, Division of Labour and the Object of participation. As the analysis of the activity system of School 1 shows, School 1 had started with a distinct approach with regard to the Eco-School programme methodology: Instead of starting with the formation of an Eco-Committee, School 1 had started with awareness raising activities towards environmental problems that were monthly embedded into the Eco-School coordinator’s natural sciences class. In these activities, students investigated the causes and effects of various environmental problems (including water pollution, consumption of water and electricity, waste disposal or recycling of various materials) and were guided towards the development of specific environmental conducts and actions that would combat the problem. As a second step, students were engaged in creating environmental campaigns in order to share their learning experience with the whole school community. In a third step, assessments with regard to the success of environmental campaigns in changing the behaviour of school community members towards more environmental ones were conducted every trimester by the Eco-School coordinator and the head of studies. In a fourth step, the Eco-Committee was created which started to function in its entirety with students in their fourth year of the Eco-School programme. Eco-Committee students were chosen democratically and reunions were conducted that served to elaborate the Action Plan and the Eco-Code as a fifth and sixth step as well as to prepare the Green Flag evaluation. At last, Eco-Audits were conducted by the Eco-School coordinator and the head of studies and not by the students. However, although School 1 followed a distinct approach with regard to the Eco-School programme methodology, a whole-school approach where the whole school community enthusiastically participated in the Eco-School programme appeared in School 1.

In School 2, the participation in the Eco-School programme did not result in a whole-school although the Seven-Step-Framework was followed more or less. Secondary contradictions between the intended object of a whole-school process and the limited reach and engagement of subjects existed in the activity system of School 2. As the section before demonstrates, the Eco-School programme at School 2 only constituted a project of the school and was not implemented into the educational project of the school. Furthermore, students needed to be constantly engaged in developing environmental actions and activities within the school and the realisation of students’ ideas posed difficulties due to a lack of persistence within students and support from the school management. There was also a low involvement of other community members into Eco-School activities. Instead, the Eco-Committee acted as a separate group within the school community and organised Eco-School activities were perceived by other students as uninteresting and ‘boring’.

Components conducive to participation in Eco-School activities

As both cases show, the Seven-Step-Approach of the Eco-School programme does not necessarily lead to a whole-school approach. However, both Eco-School programme approaches in the two schools resulted into distinct outcomes as shown in the activity systems of each school (please refer to and ). School 1 thereby showed a much wider range of positive outcomes than School 2, in terms of the students’ increased motivation for educational activities, environmental awareness, feeling of belonging to the school, decreased early school dropout as well as a stronger network of collaborating partners. Through their distinct approach regarding the Eco-School methodology, School 1 achieved the creation of a more participatory environment where students are more involved into school activities. This boosted the students’ motivation for educational activities and their responsibility to care for their environment. As has been stated by several interviewees, the majority of students in School 1 had started to internalise environmentally friendly habits into their daily lives at school and at their homes whereas in School 2 this effect could only be achieved within some Eco-Committee students. This observation raises the question of which components within the Eco-School approach of School 1 have been triggering a more successful outcome and a more whole-school approach with regard to the Eco-School programme in contrast to School 2, which can be used as a source of improvement for learning effects of students and the Eco-School programme implementation in terms of a whole-school approach at schools. Some of the discovered components can be related to important factors found in other studies that investigated a successful implementation of ESD pedagogies and a whole-school approach. In total, five components have been discovered in this research, which are further discussed below.

The first component discovered that invited student participation in Eco-School activities in School 1 was the application of an activity-based and community co-operative approach as a method for enabling experiential learning. As it has been mentioned in the section before, School 1 followed a distinct approach with regard to the Eco-School programme methodology. As the Eco-School coordinator from School 1 explained during the interview, School 1 had started the Eco-School programme with environmental activities within the curriculum, such as the environmental campaigns and the weekly workshops, which were expanded towards the school and towards the local community at last. Since the activity was related to locally relevant issues, such as water pollution and waste issues, students were more able to relate to the specific environmental topic. Furthermore, through environmental campaigns that were organised within the local community, students received the opportunity to practice their role as active citizens directly. Several researches confirmed the importance of a community co-operative approach with regard to implementing ESD at schools. In their non-exhaustive list of ‘quality criteria’ for ESD schools, Breiting, Mayer, and Mogensen (Citation2005) stressed the idea of ESD for transforming schools into active institutions that produce locally relevant knowledge. The community is thereby regarded as a “resource for fieldwork and active learning” (p. 42), which enables students to practice their future citizenship role. Also Mogren and Gericke (Citation2017) listed the cooperation with the local society as one of their four main quality criteria that guided school leaders during implementing ESD at their schools. In this way, the education provided to students is made more tangible, which provides a better understanding of the underlying environmental issue.

The second component discovered relates to the simultaneously adapted reflective and an action-oriented approach of learning, which engaged and motivated students to participate in tackling the examined environmental issue at their school. During the interview, the Eco-School coordinator explained that before the environmental campaigns were conducted, an initial understanding and concern of the investigated environmental problem among students was created. In a first step students were engaged to investigate the causes and effects of a specific environmental problem. As a second step, students in collaboration with the Eco-School coordinator deliberated their possible contribution to combat the problem. Those contributions were connected to creative and practical activities, such as making soap in order to recycle cooking oil, constructing vertical gardens out of recycled plastic bottles, designing bags out of old t-shirts, establishing creative containers for various waste types (batteries, paper, organic, plastic, waste, etc.) that were used to establish various cleaning points at school. In a last step, students shared their learnings in form of environmental campaigns with the rest of the school and later with the local community. In this way, each student contributed personally in combatting the specific environmental problem. In his critical pedagogy approach, Freire (Citation1970) emphasized that both components, reflection and action, are crucial to foster a constructive action-taking. Also, Breiting, Mayer, and Mogensen (Citation2005) as well as Mogensen and Mayer (Citation2005) highlighted the importance of an action-oriented approach to learning, which incorporates an action and a reflective component, in their research for ESD quality criteria. Thereby, students in collaboration with their teachers prepare and conduct actions to tackle environmental problems. This real-life experience generates a kind of learning process for students that has a specific meaning and purpose. Mogensen and Mayer (Citation2005) argue that this kind of understanding becomes ‘emotional’ and therefore more permanent and transferable.

The third component discovered relates to the constant adaptation of the students’ learning environment according to their needs and capacities through an annual Eco-School working plan. The latter included specific educational activities and desired educational outcomes and ensured a close guidance of students. This process relates very closely to Vygotsky’s theory of the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), which emphasizes the importance of teachers in the learning process and cognitive growth of students. Teachers thereby constantly expand the students’ zone of individual task accomplishment through providing meaningful guidance within a student’s potential learning zone (ZPD) (Berk and Winsler Citation1995; Silo Citation2011). In this way, teachers play an important part in fostering the process of ‘student-led change’ through enabling students to make meaningful contributions within their environment according to their capabilities and to constantly enlarging those capabilities. In their research, Eilam and Trop (Citation2010) as well as Mogren and Gericke (Citation2017) confirmed that learning is most meaningful when topics are made relevant to the need and interests of students and when students are actively engaged in the knowledge creation. Breiting, Mayer, and Mogensen (Citation2005) and Mogensen and Mayer (Citation2005) do not only relate meaningful participation to democracy but also to the teacher’s focus on the students’ capacities. Students are thereby put at the centre of the learning process and are provided ownership and responsibility over their own learning. Hereby, having the possibilities of choice is considered an important factor for students in this approach (Mogensen and Mayer Citation2005). Also the students’ perceived participation as well as their perceived ownership seems to foster the success of the Eco-School programme as has been noticed by Cincera et al. (Citation2019) in their research.

The fourth component discovered relates to emotional education for teachers, which facilitates a good school climate and presents to be crucial to motivate and empower students to participate in Eco-School activities. School 1 has put high emphasis on ‘emotional education’ as a training possibility for teachers that enabled a better connection of teachers with their students. As the analysis of observation and interview data revealed, Eco-School coordinator demonstrated an especially good relation to the students which allowed her to transmit her enthusiasm and importance towards those environmental problems onto the students. In their research study, Jennings and Greenberg (Citation2009) demonstrated the importance of supportive relationships among students and teachers, which are conducive to positive learning and developmental outcomes of students. Also Frenzel et al. (Citation2009) demonstrated that the teacher’s enthusiasm fosters the students’ enjoyment of a certain topic. A good relationship between students and teachers facilitates a positive school climate at school conducive to a situation where students dare to contribute with their own ideas as confirmed by several studies (Breiting, Mayer, and Mogensen Citation2005; Eilam and Trop Citation2010). A good relationship between teachers and students, which enables a good school climate is therefore crucial to motivate and empower students to participate in Eco-School activities.

The fifth component concerns the application of the Eco-School programme as an overall educational framework of the school, which resulted in a more integral and systemic effect of the Eco-School programme and enabled the support of the whole school community. When seeing the potential to decrease the school dropout with Eco-School activities, School 1 decided to use the Eco-School programme as their overall educational framework. Due to a rather institutionalised implementation of the Eco-School programme in Andalusia, School 1 also needed to develop an elaborated working plan in consultation with the relevant educational centre that includes specific educational goals and measures and that would determine the direction of their Eco-School approach. Through this procedure, a rather systemic effect of the Eco-School programme could be developed, which boosted the collaboration of the majority of the school staff in order to work towards a similar goal according to the interview with the head of studies of School 1. As the analysis of data demonstrated, the Eco-School programme in School 2 constituted only part of the school with a small group of community members were responsible for the development of the programme. Furthermore, School 2 did not need to establish an elaborated working plan including a concrete mission and objectives with regard to the Eco-School programme, which resulted in a lack of binding commitment and collaboration of other teaching staff and the school management. This demonstrates that an elaborated mission and action plan of the Eco-School programme that is integrated into the educational project of the school as a commitment constitutes an important component for a successful whole-school implementation of the Eco-School programme since it distributes the responsibility among the whole school community to work on the development of the programme collaboratively. Several studies confirmed the importance of an overall framework for the implementation of a whole-school approach. Component 5 relates closely to the notion of ‘collaborative interaction and school development’ by Mogren and Gericke (Citation2017) and the dimension of ‘holism’ by Mogren, Gericke, and Scherp (Citation2019). The former constitutes a major quality criterion for a whole-school approach at school organisation level. The authors reported in their studies that the application of a holistic vision created a commonly shared responsibility of learning and teaching, which enabled a successful ESD implementation (Mogren and Gericke Citation2017; Mogren, Gericke, and Scherp Citation2019). Also Boeve-de Pauw and Van Petegem (2018) confirmed the importance of “common goals” within the policy-making capacity of schools as a process factor for a successful implementation of the Eco-School programme.

Using Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model as a framework to depict student participation in Eco-School activities

The use of Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model as a conceptual framework for this research allowed to provide a rich and multi-facetted picture of the situation of student participation in the Eco-School programme at the two examined schools. Thereby, it enabled the analysis and understanding of student participation in Eco-School activities in each socio-cultural context by considering the various factors that influence each other, including characteristics of the school community, implementation of each Eco-School approach, motivational or mediational aspects of student participation in the Eco-School programme as well as outcomes. Depicting each systemic learning environment according to Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model, created a greater understanding of how each Eco-School approach evolved. Therefore, Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model appears to be a useful framework for analysing a situation of human practices in its entirety as well as in its context (Silo Citation2011).

Furthermore, the application of Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model enabled to demonstrate how various components of the activity system interact and influence student participation in Eco-School activities and how this affects the interpretation of the object of their participation. In this way, Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model provides a useful framework for revealing the students’ and the schools’ motivation for participating in the Eco-School programme and how the socio-cultural context influences the mediation of student participation in Eco-School activities. It also uncovered distinct perspectives regarding student participation in an Eco-School community as well as tensions and contradictions within both activity systems. In addition, Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model demonstrated to be useful not only in illustrating the systemic situation of student participation at each school, but also in illuminating how participation evolves within individual students and how the development of cognition could be enlarged through the use of the zone of proximal development by Vygotsky (Yamagata-Lynch Citation2010; Silo Citation2011).

For data collection, Mwanza (Citation2001)’s Eight Step Framework was used, which proved to be helpful for operationalising each component of Engeström’s Second Generation Activity System and for creating categories for data collection. The open-ended questions from Mwanza’s Eight Step Model on the various components of the activity system enabled to adapt this model to the situation being examined. In this way, areas of interest and necessary resources for the investigation could be determined. The addition of the 9th component (= national context) into the activity system revealed a useful application because it demonstrated the broader context in which the activity system is embedded and could show the distinct implementations of the Eco-School programme in each national context. Along the research it was noticed that CHAT leads to an easy accumulation of huge amounts of data, which can pose a difficulty when organising the data in the analysis.

As a data analysis tool of Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model, the Activity Systems Analysis (ASA) as outlined by Yamagata-Lynch (Citation2010) helped organise complex sets of qualitative data into manageable units and to communicate the results in a visual, systemic, and meaningful way.

Discussion

In total, five components conducive to student participation in Eco-School activities have been discovered in this research on the basis of the analysis of collected data, which were presented in the previous section: 1) employing an activity-based and community co-operative approach, 2) simultaneously using an adapted reflective and an action-oriented approach of learning, 3) continuously adaptating the students’ learning environment to their needs and capacities, 4) providing emotional education of teachers as a component of creatinga good school climate, and 5) utilizing the Eco-School programme as an overall educational framework of the school.

In general, what we can learn from those five components is that they fostered a successful implementation of the programme and created a situation of a supportive and participatory school community in School 1. Undoubtedly, there are other components involved that foster a whole-school approach, such as specific pedagogical and didactical approaches, community involvement, etc. Further research needs to be conducted on finding and confirming more of those components or factors. The latter can be used – apart from the 7-Step-Framework – to evaluate not only the learning but also the developmental process of students as well as the Eco-School programme at the participating school. Guidelines, similar to the “Quality criteria for ESD Schools” identified by Breiting et al. (Citation2005) or a model comparable to the one evaluated by Eilam and Trop (Citation2010) could guide schools to orient their development and ensure a successful implementation of a whole-school approach under the umbrella of the Eco-School programme.

Using Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model as a framework to depict student participation in Eco-School activities

Overall, the use of Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model as a conceptual framework for this research proved to be useful. However, during the research several issues have been noted that need further attention.

As already noticed by Yamagata-Lynch (Citation2010), it takes huge time efforts to study and completely understand CHAT and Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model due to its complexity and specific idiom, and different interpretations (see, for instance, Kaptelinin Citation2005 on the object of the activity system). This can make it difficult for outsiders to access studies based on CHAT and Engeström’s model. To counter this problem, it is important to provide a clear explanation and operationalisation of each component used in the research, and to explicitly refer to the specific literature used in applying CHAT. To improve the reader’s understanding, we chose a more common language for the elaboration of the results and discussion.

It is also worth noting that there is a certain subjectivity attached to the application of the framework since the researcher has to make decisions in the operationalisation of concepts and in the selection of data that cannot be based on theory alone, and are substantially influenced by his/her own interpretations. We concur with Yamagata-Lynch (Citation2010) in stressing that more research is needed on how to keep trustworthiness, comparability, and validity when engaging in qualitative research work with regard to Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model.

Shortcomings of the research related to data collected

Although the use of a case study design demonstrated a useful approach to outline particularities of each Eco-School case, several shortcomings during the data collection phase occurred, which can be related to the conceptual framework used. As already mentioned in the previous section, the application of Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model led to the accumulation of a huge amount of data. On the one hand, this huge amount enabled the provision of a rich picture on the specific implementation of the Eco-School programme as well as the situation of student participation in each school. On the other hand, it posed a difficulty to organise these data and to build up the argumentation of this paper. Therefore, a vast amount of collected data from interviews or observations could not be included in this research.

Another critique that should be discussed here is the choice of selected interviewees. As already mentioned before, the majority of interviewees were selected and recruited by the Eco-School coordinators, which might have had a bias towards the situation of student participation in each school. However, since a variety of different research methods had been chosen by the authors for this research, observation data mostly confirmed the positive experience in School 1 and the rather negative experience in School 2.

During the whole data collection process, an observer perspective following Glesne’s (Citation2005) participant-observer continuum was chosen. This choice led into the lack of data related to knowledge when participating in the activity as well as information on that is only shared with participants of the activity. According to Yamagata-Lynch (Citation2010), it is important to “experience observable and mental activities” (p. 29) in order to also understand students’ cognitive processes within those activities. An additional participant perspective, which enables the researcher to become a full participant of the activity, would have therefore given a more comprehensive picture of students’ experiences in Eco-School activities. This would also have required a longer stay at each school in order to experience all kinds of activities conducted within the framework of the Eco-School programme.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this research highlights the five components discovered in School 1 that are conducive for student participation in Eco-School activities based on analysed research data. An initial activity-based and community co-operative approach of the Eco-School programme as well as the interlinkage of a reflective and action-based procedure fostered the motivation of students to participate in the programme. A close guidance by teachers, a focus on emotional training for teachers, and a constant adaptation of the students’ learning environment according to their needs and capabilities enabled an improved learning process and invited students to participate in Eco-School activities. The adoption of using the Eco-School programme as an overall framework of the school, enabled a whole-school approach in School 1. The lack of comparable components – particularly an initial activity-based and community co-operative approach as well as the application of the Eco-School programme as an overall educational framework – in School 2 plausibly contributed to the limited outcomes for motivation and participation there. Using Engeström’s Second Generation Activity Systems Model as a framework for this research proved to be very useful to demonstrate the situation of student participation of Eco-School activities at each school but also to show components that motivate and facilitate student participation in Eco-School activities. Because of its limited scope, this research cannot provide conclusions, let alone guidelines, on the application of these five components in Eco-Schools elsewhere. However, our findings suggest that this deserves further investigation.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (38.7 KB)Acknowledgements

Our sincere thanks goes to the Foundation for Environmental Education (FEE) for their collaboration and for giving the possibility to conduct research on their Eco-Schools programme. Special thanks also go to the national operators in Spain (ADEAC) and the Netherlands (SME Advies) as well as to the two Eco-Schools, School 1 and School 2 (the names have been anonymized due to data protection issues), for providing great support for the data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Laura-Marie U. Schröder

Laura-Marie U. Schröder graduated in Environmental Sciences from Wageningen University and Research Centre in the Netherlands in 2017. She majored in Environmental Policy and also holds a minor in Environmental Education and Communication for Sustainability. Her main research areas of interest are the development of capacity building processes for sustainability on individual, institutional and societal level as well as the contribution of environmental organizations and institutions to global environmental governance.

Arjen E. J. Wals

Arjen E. J. Wals is a Professor within the Education and Learning Sciences Group at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. He also holds the UNESCO Chair of Social Learning and Sustainable Development and a Guest Professor in Whole School Approaches to Sustainability at the Norwegian Life Sciences University. His teaching and research focus on designing learning processes and learning spaces that enable people to contribute meaningfully to sustainability.

C. S. A. (Kris) van Koppen

C. S. A. (Kris) van Koppen is an Associate Professor within the Environmental Policy Group at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. He is also a former professor of Environmental Education at Utrecht University. His area of research and education is sociology of nature, with a special interest in social and organisational learning.

Notes

1 The “social need” refers to the intrinsic need of a particular community that motivates its members to participate in certain activities. For a more detailed explanation of this term see: Yamagata-Lynch (Citation2010), Silo (Citation2011), and Blunden (Citation2015).

2 % early school dropout = % of students that finish the Obligatory Secondary Education without any degree

References

- Arnold, H. E., F. G. Cohen, and A. Warner. 2009. “Youth and Environmental Action: Perspectives of Young Environmental Leaders on their Formative Influences.” The Journal of environmental education 40(3): 27–36. doi:10.3200/JOEE.40.3.27-36.

- Breiting, S., M. Mayer, and F. Mogensen. 2005. Quality Criteria for ESD-Schools: Guidelines to Enhance the Quality of Education for Sustainable Development. Vienna: Austrian Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Culture.

- Berglund, T., Gericke, N. N., and S. N. Chang Rundgren. 2014. “The Implementation of Education for Sustainable Development in Sweden: Investigating the Sustainability Consciousness among Upper Secondary Students.” Research in Science & Technological Education 32 (3): 318–339. doi:10.1080/02635143.2014.944493.

- Berk, L. E., and A. Winsler. 1995. Scaffolding Children’s Learning: Vygotsky and Early Childhood Education. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

- Blunden, A. 2015. “Lecture 9. The Object of Activity in Leontyev, Engeström and Vygotsky.” Concepts of Cultural Historical Activity Theory, March 14. Accessed 3 August 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Oek0RDjkT_c&t=2658s.

- Boeve‐de Pauw, J., and P. Van Petegem. 2013. “The Effect of Eco-Schools on Children’s Environmental Values and Behaviour.” Journal of Biological Education 47 (2): 96–103. doi:10.1080/00219266.2013.764342.

- Boeve‐de Pauw, J. and P. Van Petegem. 2017. “Eco-school Evaluation Beyond Labels: The Impact of Environmental Policy, Didactics and Nature at School on Student Outcomes.” Environmental Education Research 24(9):1250–1267. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1307327.

- Boeve‐de Pauw, J., and P. Van Petegem. 2018. “Eco-School Evaluation beyond Labels: The Impact of Environmental Policy, Didactics and Nature at School on Student Outcomes.” Environmental Education Research 24 (9): 1250–1267. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1307327.

- Boeve‐de Pauw, J., and P. Van Petegem. 2011. “The Effect of Flemish Eco-Schools on Student Environmental Knowledge, Attitudes, and Affect.” International Journal of Science Education 33 (11): 1513–1538. doi:10.1080/09500693.2010.540725.

- Center on International Education Benchmarking (CIEB). 2017. “Netherlands Overview.” Accessed 7 November 2017. http://ncee.org/what-we-do/center-on-international-education-benchmarking/top-performing-countries/netherlands-overview/.