Abstract

In the current debate, there is no consensus on the relationship between knowledge and values in students’ reasoning and argumentation in socio-scientific and sustainability issues, i.e. if these should be addressed as separate entities or rather treated as a whole. In this study, we address this question empirically, with students engaging in two language games – aesthetic and epistemological – as they deliberate on ethical issues associated with genetic engineering. The study reports on a course unit that includes lectures, group work and student-led value-clarification exercises. The ways in which the language games interact were analysed using the established methods of Practical Epistemology Analysis (PEA) and analysis of Deliberative Educational Questions (DEQ). Our results show that aesthetic and epistemological language games were intricately intertwined in the students’ reasoning. Given this close entanglement, each language game was conducive to the development of the other and in so doing, deepened the understanding of the content as a whole.

1. Risk in socio-scientific issues

Today humanity faces several acute and unprecedented threats that lack linear solutions. Global warming, biodiversity loss, health and wellbeing or consumption are all examples of issues concerning sustainable development. What from one perspective seems to represent a quick resolution may present new challenges from another point of view. What appears reasonably easy to solve in a circumscribed context may become significantly more intractable in a context of greater complexity. Such challenges, sometimes referred to as ill-structured or wicked problems (Weber and Khademian Citation2008), are often referred to as risks (Beck Citation1992; Schenk et al. Citation2018; Schenk et al. Citation2019). Deliberation concerning risk is therefore useful when dealing with sustainability and socio-scientific issues in education (Christensen Citation2009; Cross Citation1993; Kolstø Citation2006; Ratcliffe, Grace, and Cremin Citation2005; Ryder Citation2009; Weber and Khademian Citation2008). Technically, risk may be defined both qualitatively and quantitatively. A common definition of risk is the expected value rendered from the product of the probability and consequences of a negative event (Aven Citation2012; Schenk et al. Citation2019). Not least in times of increasing flux of disinformation and ‘fake news’ it is crucial to have access to such fact-based information. Yet, because these issues also have to do with the degree of severity attributed to particular consequences, decision-making on issues concerning risk cannot be based on factual knowledge alone (Aven and Renn, Citation2009; Hansson Citation2010). Thus, such a deliberation also includes decisions about what is perceived as right and wrong, good and evil, and in the end, political standpoints based on what people cherish and care for. Risk assessments need to be made by considering facts from various scientific areas in relation to value-based decisions on an individual as well as on a societal level (Schenk et al. Citation2019). Therefore, an integration of scientific knowledge (on probability and consequences) and socially constructed values (on the assessment of severity) becomes crucial in all kinds of decision-making on issues concerning risk in the public space, not least when it comes to issues of sustainable development (ibid.). An example of issues where risk is at the forefront is about how sustainability issues, concerning heath and biodiversity loss, can be addressed with the help of genetic engineering. In this study, we examine the interaction between knowledge and values in high school students’ deliberations concerning risks associated with gene technology.

1.2. Facts or values in student deliberation, earlier research

Although issues connected to sustainability and risk are considered both interesting and relevant in contemporary education, they are also connected to certain teaching challenges concerning how to handle student’s use of facts and values in their deliberation. The attention that students, when reasoning, use both insights and opinions, containing facts as well as values, has stimulated different approaches to research and education within this area. Some argue that a higher level of content-specific knowledge and a qualified learning about how to sort out reliable scientific knowledge from simplified thoughts and values are needed (Grace and Ratcliffe Citation2002; Sadler and Donnelly Citation2006; Albe Citation2008; Lindahl Citation2009; Lee and Brown Citation2018). Other studies have focussed specifically on the value aspects of the issues at stake, where the students’ personal experiences, family background and popular culture may influence their rational judgements. These studies argue that teaching should give special consideration to students’ moral growth (Sadler and Zeidler Citation2004; Fowler, Zeidler, and Sadler Citation2009; Zeidler and Keefer Citation2006). “If we want students to think for themselves, then they need opportunities to engage in informal reasoning, including the contemplation of evidence and data, and express themselves through argumentation” (Sadler Citation2004, 533). Yet other studies (Nielsen Citation2012; Citation2013) ask for the need of further scrutinising the distinction between facts and values in students’ reasoning, and highlight that, “the widespread focus on students’ abilities to cite evidence should be substituted by a focus on how students articulate evidence vis-à-vis other factors in socio-scientific activities” (Nielsen Citation2013, 381).

In sum, to determine the relation between statements based on knowledge and statements based on values (epistemological and/or aesthetic judgements) in students’ reasoning on socio-scientific issues is urgent. Thus, it seems important to (1) investigate what it means to study reasoning based on facts or values in student deliberation empirically, and (2) contribute to an educational framework on this. What’s also needs to be clarified here is that we use the concept deliberation simply to describe students’ variegated ways of reaching a more commonly considered decision.

2. Theoretical background – two language games

The study is conducted within a pragmatic framework, in which the students’ meaning making is discerned as their immediate interactions in the classroom (Wickman and Östman Citation2002). Traditionally, education has often been interpreted psychologically (Wickman Citation2006), where students’ behaviours or utterances were interpreted as expressions of inner states of mind.

In this study, based on a pragmatic framework we instead study how utterances based on knowledge and values in the students’ mutual interactions lead to further meaning making that is, how the content at hand becomes intelligible and at the same time acquires aesthetic meaning in the ongoing interaction (Wickman Citation2006; Lundegård Citation2018). Thus, we analyse language as communicative action rather than as mental representations of hidden, private meaning (Dewey Citation1925; Rorty Citation1992; Wickman Citation2006). This is also what Wittgenstein (Citation1953/1997) refers to as an analysis of the language games people are involved in as they use words to reach certain consequences. According to this framework, our operationalisation is based on an analytical distinction between two different language games which relate to what kind of statements the students use in their deliberations. Either they use an epistemological language game, arguing about things based on factual reasoning, or an aesthetic language game where evaluative judgements take place. These ways of creating meaning are reasoned about on a theoretical/philosophical level by Cavell (Citation1979/1999) and further concretised through empirical studies by Lundegård (Citation2018).

The epistemological language game, rests on rational factual arguments and reasoning which, from a third-person perspective, may be related to criteria, usually for whether something ‘is’ the case or not (Cavell Citation1979/1999). It is obvious, of course, that this epistemological reasoning can be understood from many different perspectives, based on scientific as well as everyday experiences. This kind of reasoning may be said to answer the questions: How do you know this and what criteria do your knowledge rest on?

The aesthetic language game, in turn, concerns an ‘ought’ in relation to different evaluative choices and thereby directions for future action. When, for example Dewey (Citation1934/1980), pragmatically talks about an aesthetic experience, he does not differentiate between the true, the beautiful or the good (Wickman Citation2006). The statements based on these kinds of experiences may all be said to answer the question: What do you praise and care for? (Cavell, Citation1979/1999). This kind of reasoning is also what we refer to when we claim that the students are taking part in an aesthetic language game (Wickman Citation2006; Lundegård Citation2018).

To sum up: In this study and analysis, we highlight two ways to reason and deliberate as different language games. In what is here referred to as an epistemological language games people add puzzle pieces of criteria based on factual, logical, empirical arguments, which may form the basis of knowledge in a certain area. (Cavell Citation1979/1999). Especially in science education (the context in which this study takes place), where teaching is often concerned with helping students to build logically valid and empirically based narratives and structures, this is usually referred to as real and important learning. The aesthetic language game on the other hand, does not rest primarily on facts or criteria. When someone claims to honour, love, trust or care for something, they are not normally required to substantiate these utterances with facts. Yet, this language game sometimes has the power to overturn the entire epistemologically grounded conclusion of an argument (Cavell Citation1979/1999). Theoretically, such a phenomena and concept, containing both epistemological and aesthetic reasoning, have earlier been referred to as a ‘thick ethical concept’ (Williams Citation1985). Some examples of such concepts, holding both description and values, could be wealth, democracy, freedom, or sustainable development.

From this theoretical starting point, we may state the following: Students’ deliberations may be studied through a lens of what is referred to as ‘language games’. Their reasoning within an aesthetic language game revolves around questions about what ‘ought’ to be done, which choices to make, and which paths to take. Reasoning within an epistemological language creates and recreates logical and systematic claims about what ‘is’ actually the case. It is thereby possible to examine if, and in what way aesthetic and epistemological reasoning are deliberated and integrated in the students’ ‘thick comprehensions’ on issues associated with risk.

Based on the analytical framework presented, we may state the research question thus:

What epistemological and aesthetic language games emerge and interact in students’ reasoning on issues concerning risk within gene technology?

3. The study design

3.1. Educational setting and lesson design

The study was conducted in a first-year high school class with 32 Swedish students, 17 girls and 15 boys, between 17 and 18 years old, all from a middle-class background. The programme they participated in emphasises the links between science and society. The difference between this programme and one focussed on natural sciences (i.e. Biology, Chemistry and Physics) is that the latter delves deeply into the academic subjects, whilst this programme provides students not only with an overview of natural science but also a rich range of social science. This study was conducted with a Biology class that focused on genetics. The teaching was part of the regular course work, but participation in the research part of the sequence and being recorded was voluntary, and informed consent was collected in writing from students prior to starting the teaching sequence.

The particular teaching sequence that was examined began after a period of eight weeks of regular teaching about genetics. In the first lesson, the teacher (second author) in the research team introduced concepts and methods related to genetic engineering to the whole class. The students also received a brief introduction to the concept of risk and how to use a matrix for evaluating risk. In the next lesson The Hot Chair (Byréus Citation1992) was introduced as a method for conducting a value-clarification exercise (Kirschenbaum et al. Citation1977). The Hot Chair is an exercise where students indicate agreement or disagreement with a statement, in this case ʻI would never eat genetic modified salmon’, by moving between chairs. A student who disagrees indicates this by moving to another chair whereas a student who agrees remains seated (there should always be one more chair than participants). Then these immediate reactions by the students are raised to a reflective deliberation based on further arguments, which of course is the overall purpose with the exercise. During this, they are free to move back and forth if the arguments of others are perceived as more convincing. The purpose of starting with these two lessons was to give the students a context and a method for formulating, justifying and reflecting on an area of genetic engineering associated with risk.

These lessons were followed by three lessons consisting of small-group work on eight different areas of genetic engineering. The aim was that the students (two in each group) should prepare to present a particular area and lead a value-clarification exercise on this topic with their peers. Each group was given one of the following genetic engineering areas to delve into: prenatal diagnosis, genetic testing, pharmacogenetics, DNA-based forensics, gene banks and biodiversity, gene therapy, cloning, and genetically modified organisms (GMOs). The instructions for the assignment were:

Find out information about opportunities, risks and moral concerns in your given genetic-engineering area.

Write a summary of the information and display this on a digital poster.

Use the information to formulate two value-clarification statements that require your peers to deliberate and take a decision on risks in your genetic engineering area.

Prepare a short oral presentation (5 minutes) of background information needed for the value-clarification statements, using the poster as a point of departure.

Prepare for some follow-up questions in case the discussion stalls.

At the end of the unit each group presented on their particular area of genetic engineering and thereafter led two value-clarification exercises in a half-class session (120 min).

3.2. The student-led value clarification exercises

Each value-clarification exercise was led by two students who had prepared a presentation giving the others a background. This was followed by a student-led discussion about a prepared value-clarification statement using The Hot Chair method described above (Byréus Citation1992). The value-clarification statements were connected to the risks that the different groups had identified as being involved in genetic engineering. Below we provide examples of areas of value clarification produced by the students:

The right to have an abortion if the foetus has a chromosome abnormality.

The right of police to access all citizens’ DNA.

Gene therapy as a potential way to advance human development.

Providing genes to gene banks.

Employers’ rights to demand that their employees undergo genetic testing.

Retrieving stem cells from a miscarried foetus to make a clone.

The use of genetically modified organisms.

The whole unit ended with the teacher summarising the discussion. Some factual misunderstandings that had emerged during the student-led value-clarification exercises were corrected and clarified by the teacher. provides a brief overview of the whole activity.

Table 1. Documented teaching activities according to six steps in the teaching activity.

3.3. Data collection and analysis

Primary data for this study were video and audio recordings from 23 value-clarification exercises produced by 12 groups of students in three sessions of 120 min each. The summaries and posters produced, and notes taken by the research team were collected digitally (see ). First, all value-clarification exercises were analysed with a focus on identifying the epistemological and aesthetic language games in the students’ deliberations. Second, we wanted to make visible in what order they interacted and exchanged. To accomplish this, we used a combination of practical epistemological analysis, PEA; (Wickman and Östman Citation2002) and analysis of deliberative educational questions (DEQ; Lundegård and Wickman Citation2007). Through PEA, discourse is studied as participation in specific language games. Such an analysis rests on four key concepts – purposes, encounters, relations, and gaps. First, an important part of PEA is to identify what the students are engaged in and what the purpose of the activity is about. Second, an activity always takes place as encounters with the physical environment and other people. Third, the analysis concerns what verbal relations the participants establish with these encounters during the teaching activity; in this particular case the value-clarification activity. The last important step in PEA is to identify what gaps are bridged as the relation becomes established. One way of making those gaps visible is to reformulate them as questions or issues that the language games deal with i.e. deliberative educational questions DEQs (Lundegård and Wickman Citation2007). DEQ is thus an analytical method where the relations the students form in their communicative exchange are turned into a choice. That choice then translates into an issue between the two options it offers. Accordingly, through the identification of DEQs, it was possible to identify the issues at stake in our students’ deliberations and, further, to which language game – epistemological or aesthetic – these could be linked. It is important to bear in mind that the deliberative questions (issues at stake) presented in the results were primarily formulated through the analysis and were not questions that the students themselves posed during the activity.

Thus, we conducted our analysis in two steps. First, we identified DEQs consecutively in all the transcripts through analyses of established relations and gaps noticed. Second, these DEQs were characterised as either epistemological, as an answer to the question ‘is’ or aesthetic as an answer to ‘ought’, what is praised and cared for. This first part of the analysis may be summarised in the following two analytic questions that we posed when analysing the transcripts:

What DEQs in the students’ deliberations can be referred to as an aesthetic language game?

What DEQs in the students’ deliberations can be referred to as an epistemological language game?

How the theoretical framework was used to extract the different language games is more thoroughly described in close connection to the transcript presented in pages 10–16. Thirdly, to answer the study’s overall research question about where the two language games emerge and interact, we took a closer look at how they were performed in the actual deliberation presented in the exercise below. This part of the analysis may be summarised in the following analytic question directed to this particular transcript:

What do the interaction and shift between the two language games look like in the student deliberations?

4. Claims and issues at stake – an overview

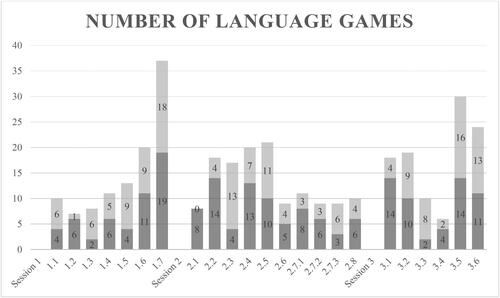

All 23 exercises except one performed over three sessions contained both aesthetic and epistemological reasoning, based on our analysis, but to varying degrees. In all, a total of 184 aesthetic and 161 epistemological issues were rendered. All but one of the particular value-clarification exercises contained both aesthetic and epistemological language games but again, to varying degrees. (in Appendix 1.) shows the different value-clarification claims posed by the students.

The dark part of the bars = Aesthetic; The light part of the bars = Epistemological ().

Figure 1. Number of language games represented in each value-clarification exercise (see Appendix 1).

4.1. Language games in continuous exchange

The analysis of the students’ deliberations during the value-clarification exercises generated epistemological as well as aesthetic DEQs. In all excerpts but one it was evident that the two language games alternated during the conversations. The transcript below has been taken out as an example that illustrates how the students’ deliberation continued through most of the exercises and how the analysis was made out from this. That a similar process took place in most exercises is shown in connection with the problems the students identified in (Appendix 1.). In the following transcript we show how the two language games evolved in a continuous exchange when nine students deliberated on the concept of genetic testing, (Group III, 3.2). The value-clarification statement formulated by the group leading the exercise concerned risks associated with agreeing to be genetically tested before being employed. The conditions were those described above for The Hot Chair method (Byréus Citation1992), with the two students who lead the discussion sitting beside each other and the other seven on chairs in a circle around them. The deliberation on this statement lasted 15 min and 45 s.

When we reconnect to the theoretical framework described above, then the different concepts render the following functions:

The encounter was what the students were part of when they were confronted with each other and argued about these issues.

The purpose was to give an answer to the question of whether companies would have access to information about the employees’ genetic constitution, and together become wiser in relation to this question.

The relations are what statements the students what statements the students came up with in their discussions in their discussion.

The gaps are what these relations bridged over, here reformulated into DEQ’s.

In the column to the right, below, we display the transcript of the deliberations. In the left column we provide a description of this discussion based mainly on PEA. Here we also present the epistemological (E-DEQ) and aesthetic (A-DEQ) issues that could be extracted through the analysis. In the excerpt, the students’ names have been changed, but gender identity (as perceived by original name) has been retained.

4.2 How did the aesthetic and epistemological language games exchange during the conversation?

From the analysis of the conversation, we can observe how the students employed epistemological issues, i.e. criteria and facts in the context of ‘is’ concerning issues like type of job, state of disease, probability of events and type of information, as well as aesthetic issues in the context of ‘ought’ relating to matters such as protecting people’s lives, and concerns about how long it takes for a disease to manifest, integrity, security and trust in people’s reasoning. During the short sequence reported above, 19 issues could be distinguished. When we study how they interchange each other, the pattern is as follows (A = aesthetic, E = epistemological).

E – E – A – E – A – E – E – E – E – A – A – A – A – E – A – A – A – E – A.

As in all other examples but one, we see that they appeared in an exchange; where the aesthetic language game preceded the epistemological and vice versa, i.e. that the aesthetic utterances created a need for additional facts which then lead to the aesthetic language game to change as new knowledge is added (cf. , Appendix 1.). Once again, it is important to notice that when we present the issues as DEQs, these are derived through the analysis of the deliberation and not from questions posed by the students themselves. Furthermore, one may notice that the epistemological DEQs did not exclusively include knowledge related to genetics and gene technology, but also to other areas of science as well as societal facts (how these alternates are reported in , Appendix 1).

It is obvious that the opening value-clarification statement in this kind of exercise calls for a choice based on both factual knowledge and aesthetic considerations. Issues about whether we want to transfer information about our genes to authorities and companies (cf. 3.2, , Appendix 1.), whether we are willing to create clones from stem cells (cf. 1.5, , Appendix 1.), or whether we have access to information about inherited diseases (cf. 3.1, , Appendix 1.), are all about both the knowledge we have about these issues and how we evaluate consequences related to the choices we make. In only one of the examples (2.1) did the students discuss the statement only based on the aesthetic language game and none of them deepened the discussion epistemologically. This was probably also the reason why the deliberation soon faded. In some of the examples, the students got stuck in one language game for a while before switching to the other. More often, however, they did not delve into one language game for a series of turns, but instead passed from one to the next within a single turn. In this study, we have not, on a microlevel, been able to investigate what causes the conversation to shift in either one direction or the other. This could be an interesting question for further investigation. What we have seen however, is that there is an ongoing interaction between the two language games in which each feeds and creates a demand for knowledge in the other. This close interaction thus deepens the discussion on both the aesthetic and the epistemological level.

5. Epistemology and aesthetics in continuity – two main conclusions

In our analysis above we provide a detailed, empirically grounded example of that aesthetic and epistemological language games interact during students’ deliberations about risks associated with gene technology. The study makes two suggestions for further studies within this field.

First and most important, we have been able to show that a continuity between the aesthetic concerns and the epistemological criteria is created continuously in the students reasoning. In this way, an aesthetic language game in which students are engaged seems to create a basis and a demand for new knowledge and criteria within an epistemological language game, while the epistemological language game in turn might enable new, value-based choices to be expressed in the aesthetic. To proceed with the deliberative activity the students continually identify new things to care for, and in order to defend these they need to rely on new epistemological criteria.

Second, and as a consequence of the empirical ambitions of the study we have been able to suggest a method of distinguishing, in a structured way, how value-based and knowledge-based arguments interact in students’ deliberations on socio-scientific issues associated with risk. Analysis of what questions (issues at hand) the students pay attention to in the process makes it possible to be sensitive to changes in and interactions between the two ways of deliberating the issues. The fact that these are described as two language games does not mean that fact and value positions are separated a priori. On the contrary, the nature of their transactional relationship is an empirical question worthy of study.

5.1. Reasoning about risk through ‘thick comprehensions’

Although we did not see any specific, regular pattern in the exchange between the two language games, we could recognise a mutual back-and-forth transition between them. In a value-clarification exercise of the kind used in this study (Kirschenbaum et al. Citation1977), in which the students initially switch chairs to indicate their response to a value-clarification statement, the physical displacement itself forms the initial part of the deliberation. The students react to an issue that requires them to take a somewhat unreflected stance through a bodily action based on their lived experience. Thus, some of them choose to move while others remain seated. After this initial reaction, wesee how they eventually also became involved in an epistemological language game which demanded new fact-based knowledge to assist them to make new or modified decisions. However, to do this, they are forced to negotiate new points of departure for the assessment of risk severity, meaning that they once again become involved in an aesthetic language game about what to defend: human life, equity, personal integrity or other values. And so, the intricate entanglement of facts and values (epistemology and aesthetics) continues.

Theoretically as mentioned above, such phenomena and concepts, containing both aesthetic and epistemological components, have been referred to as ‘thick ethical concepts’ (Williams Citation1985). In this study, with its action-oriented, pragmatic base, we are more interested in studying in what way the epistemological and aesthetic language games exchange in the students’ process of engaging with critical issues. Given the empirical basis of our study, we label this process thick comprehension. Such an idea contributes in two ways to how one views the relation between knowledge and values in teaching: (1) by the term ‘comprehension’ we emphasise the process of making meaning through deliberation, and (2) by the term ‘thick’ we emphasise that epistemology and aesthetics are entangled in this process.

5.2. Implications for teaching

This study’s point of departure is teaching aimed at providing students with knowledge that helps them to take decisions on ill-structured or wicked problems, often closely connected to moral and political issues linked to sustainability. Often such courses of action are treated in terms of risk. The assessment of risk is connected both to what we know and what we care about (Schenk et al. Citation2019) In such a context, reasoning based on knowledge (epistemological criteria) as well as values (aesthetic judgement) is a significant part of what students need to experience in education.

This study’s point of departure is teaching aimed at providing students with knowledge that helps them to take decisions on ill-structured or wicked problems, often closely connected to moral and political issues linked to sustainability. Discussion has focussed on whether SSI-teaching indeed leads to any deeper knowledge of the subject matter, which in this case would be genetics and gene technology. Some researchers argue that students take decisions by invoking immediate, value-based reactions rather than by applying the appropriate scientific knowledge (Grace and Ratcliffe Citation2002), while others claim that students tend to assign too much importance to scientific data (Albe Citation2008). However, the results of this study show clearly that, although part of their epistemological reasoning concerned knowledge areas other than science, the students requested factual clarification of aspects related to the subject matter. As regards the fact–value debate, we have shown that their reasoning takes the form of an emulsion of what sometimes habitually is referred to as two separate domains. The question, then, is whether science teaching should teach students to sort out an absolute distinction between an ‘is’ and an ‘ought’ (Grace and Ratcliffe Citation2002; Sadler and Zeidler Citation2005; Sadler and Donnelly Citation2006; Albe Citation2008; Lindahl Citation2009). Based on the results of our study, we suggest that the task is rather to help students discover what they refer to in their deliberation, and in so doing help them to reflect on how a rich synthesis of these aspects contributes to a more complete picture of the whole (Nielsen Citation2012; Citation2013).

Perhaps the most important result of this study is the finding that each language game gave rise to sorting out issues in the other. An important didactic question thus requiring further study is how teachers can take the aesthetic reasoning with which students often begin their deliberations and use this as scaffold for a more explicit exploration of the scientific knowledge. One option here could be to engage students in this kind of deliberation early in a unit, and then more explicitly asking them what knowledge they require in order to take a decision on a certain issue. These design ideas are currently being trialled in new studies, in which the interaction between knowledge and values is used to generate new designs for science teaching where students are inspired to request and seek out additional and deeper knowledge related to the subject matter.

Issues containing risk are at the heart of socio-scientific issues and education for sustainable development, ESD. To adopt a risk perspective on these issues is to include fact-based information about probability and consequences while simultaneously evaluating the severity of a future scenario. We have shown that this kind of constant interplay is evident when students are confronted with matters of this nature. Consequently, and in the interests of developing meaningful science teaching practices, we welcome further research that examines the interaction and exchange patterns in student deliberations on issues associated with risk in science and sustainability education.

ceer_a_2031900_sm1150.docx

Download MS Word (44.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential confl ict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Iann Lundegård

Iann Lundegård [email protected] corresponding author, is associate professor in science education. His research interest is educational philosophy associated with high school students’ deliberations and meaning making on sustainable development.

Leena Arvanitis

Leena Arvanitis second author is lecturer in Biology and Science studies and holds a PhD in Plant Ecology. Her research interest is how teaching with socio scientific issues may be used for increasing student’s motivation and inclusion in science as well as for improving student learning of subject matter.

Karim Hamza

Karim Hamza co-author, is associate professor in Science Education. His research focuses on methodological approaches for developing knowledge about teaching in collaboration with practicing teachers, as well as on development and refinement of didactic models for teaching certain science subject matter.

Linda Schenk

Linda Schenk co-author, holds a PhD in Risk and Safety. Her research focuses on the identification, assessment and management of risk with chemical substances, in which understanding of risk, communication and education about risks play important roles.

Andrzej Wojcik

Andrzej Wojcik co-author, is professor of radiation biology. He focuses on studying the cellular effects of radiation, with special focus on combined exposure to radiations of different qualities. He is also interested in radiological protection and teaching about health risks from exposure to ionising radiation.

Karin Haglund

Karin Haglund co-author, is a teacher in physics, chemistry and mathematics and holds a PhD in Biophysics. Her interest is developing physics and chemistry education.

References

- Albe, V. 2008. “Students’ Positions and Considerations of Scientific Evidence about a Controversial Socioscientific Issue.” Science & Education 17 (8-9): 805–827. doi:10.1007/s11191-007-9086-6.

- Aven, T. 2012. “The Risk Concept—Historical and Recent Development Trends.” Reliability Engineering & System Safety 99: 33–44. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2011.11.006.

- Aven, T., and O. Renn. 2009. “On Risk Defined as an Event Where the Outcome is Uncertain.” Journal of Risk Research 12 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1080/13669870802488883.

- Beck, U. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity (M. Ritter, Trans.). London: Sage.

- Byréus, K. 1992. Du har huvudrollen i ditt liv: om forumspel som pedagogisk metod för frigörelse och förändring. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Cavell, S. 1979/1999. The Claim of Reason: Wittgenstein, Skepticism, Morality, and Tragedy. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Christensen, C. 2009. “Risk and School Science Education.” Studies in Science Education 45 (2): 205–223. doi:10.1080/03057260903142293.

- Cross, R. T. 1993. “The Risk of Risks: A Challenge and a Dilemma for Science and Technological Education.” Research in Science & Technological Education 11 (2): 171–183. doi:10.1080/0263514930110206.

- Dewey, J. 1925/1996. “Experience and Nature.” In L. Hickman (Ed.), Collected Works of John Dewey, 1882-1953: The Electronic Edition (Later Works, Volume 1). Charlottesville, VA: InteLex Corporation.

- Dewey, J. 1934/1980. Art as Experience. New York: The Berkely Publishing Group/Penguin Putnam Inc.

- Fowler, S. R., D. L. Zeidler, and T. D. Sadler. 2009. “Moral Sensitivity in the Context of Socioscientific Issues in High School Science Students.” International Journal of Science Education 31 (2): 279–296. doi:10.1080/09500690701787909.

- Grace, M. M., and M. Ratcliffe. 2002. “The Science and Values That Young People Draw upon to Make Decisions about Biological Conservation Issues.” International Journal of Science Education 24 (11): 1157–1169. doi:10.1080/09500690210134848.

- Hansson, S. O. 2010. “Risk: Objective or Subjective, Facts or Values.” Journal of Risk Research 13 (2): 231–238. doi:10.1080/13669870903126226.

- Kirschenbaum, H., Harmin, M. Leland, Howe, L., and Simon, S. B. 1977. “In Defense of Values Clarification.” The Phi Delta Kappan 58: 743–746.

- Kolstø, S. D. 2006. “Patterns in Students’ Argumentation Confronted with a Risk-Focused Socio-Scientific Issue.” International Journal of Science Education 28 (14): 1689–1716. doi:10.1080/09500690600560878.

- Lee, E. A., and M. B. Brown. 2018. “Connecting Inquiry and Values in Science Education.” Science & Education 27 (1-2): 63–79. doi:10.1007/s11191-017-9952-9.

- Lindahl, M. G. 2009. “Ethics or Morals: Understanding Students’ Values Related to Genetic Tests on Humans.” Science & Education 18 (10): 1285–1311. doi:10.1007/s11191-008-9148-4.

- Lundegård, I. 2018. “Personal Authenticity and Political Subjectivity in Student Deliberation in Environmental and Sustainability Education.” Environmental Education Resarch 24 (4): 1–12. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1321736.

- Lundegård, I., and P.-O. Wickman. 2007. “Conflicts of Interest: An Indispensable Element of Education for Sustainable Development.” Environmental Education Research 13 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/13504620601122566.

- Nielsen, J. A. 2012. “Co-Opting Science: A Preliminary Study of How Students Invoke Science in Value-Laden Discussions.” International Journal of Science Education 34 (2): 275–299. doi:10.1080/09500693.2011.572305.

- Nielsen, J. A. 2013. “Delusions about Evidence: On Why Scientific Evidence Should Not Be the Main Concern in Socioscientific Decision Making.” Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education 13 (4): 373–385. doi:10.1080/14926156.2013.845323.

- Östman, L. 1998. “How Companion Meanings Are Expressed by Science Education Discourse.” In Problems of Meaning in Science Curriculum, edited by D. A. Roberts & L. Östman, 54–71. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Ratcliffe, M., M. Grace, and H. Cremin. 2005. “Science Education for Citizenship: Teaching Socio-Scientific Issues.” British Educational Research Journal 31 (6): 807–809.

- Rorty, R. 1992. The Linguistic Turn: Essays in Philosophical Method. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Ryder, J. 2009. “Enhancing Engagement with Science-Related Issues: The Role of Students’ Understandings about the Nature of Science.” In International Handbook on Research and Development in Technology Education, edited by D. Hodson. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Sadler, R. 2004. “Informal Reasoning regarding Socioscientific Issues: A Critical Review of Research.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 41 (5): 513–536. VOL. NO. PP. doi:10.1002/tea.20009.

- Sadler, T. D., and L. A. Donnelly. 2006. “Socioscientific Argumentation: The Effects of Content Knowledge and Morality.” International Journal of Science Education 28 (12): 1463–1488. doi:10.1080/09500690600708717.

- Sadler, T. D., and D. L. Zeidler. 2004. “The Morality of Socioscientific Issues: Construal and Resolution of Genetic Engineering Dilemmas.” Science Education 88 (1): 4–27. doi:10.1002/sce.10101.

- Sadler, T. D., and D. L. Zeidler. 2005. “The Significance of Content Knowledge for Informal Reasoning regarding Socioscientific Issues: Applying Genetics Knowledge to Genetic Engineering Issues.” Science Education 89 (1): 71–93. doi:10.1002/sce.20023.

- Schenk, L., M. Enghag, I. Lundegård, K. Haglund, L. Arvanitis, K. Hamza, and A. Wojcik. 2018. “The Concept of Risk: Implications for Science Education.” In Electronic Proceedings of the ESERA 2017 Conference. Research, edited by O. E. Finlayson, E. McLoughlin, S. Erduran, & P. E. Childs, Practice and Collaboration in Science Education. Dublin, Ireland: Dublin City University.

- Schenk, L., K. Hamza, M. Enghag, I. Lundegård, K. Haglund, L. Arvanitis, and A. Wojcik. 2019. “Teaching and Discussing about Risk: Seven Elements of Potential Significance for Science Education.” International Journal of Science Education 41 (9): 1271–1286. doi:10.1080/09500693.2019.1606961.

- Weber, E. P., and A. M. Khademian. 2008. “Wicked Problems, Knowledge Challenges, and Collaborative Capacity Builders in Network Settings.” Public Administration Review 68 (2): 334–349. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00866.x.

- Wickman, P.-O. 2006. Aesthetic Experience in Science Education: Learning and Meaning-Making as Situated Talk and Action. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Wickman, P.-O., and L. Östman. 2002. “Learning as Discourse Change: A Sociocultural Mechanism.” Science Education 86 (5): 601–623. doi:10.1002/sce.10036.

- Williams, B. 1985. Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wittgenstein, L., 1953/1997. Philosophical Investigations. Translated by G. E. M. Anscombe. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Zeidler, D. L., M. Keefer, 2006. “The Role of Moral Reasoning and the Status of Socio-Scientific Issues in Science Education.” In The Role of Moral Reasoning on Socioscientific Issues and Discourse in Science Education [Electronic Resource], edited by D. L. Zeidler, 7–38. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Appendix 1

Table A1 . Issues at stake and order of language games in the value-clarification exercises dealt with over three sessions.