Abstract

Education for Sustainability (EfS) seeks to empower children with knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes to address global challenges while adhering to sustainability principles. This study investigates the conceptual understanding and pedagogical practices of EfS among early childhood education (ECE) teachers in Norway. Using mixed-methods design, data were collected through reflection notes, surveys, and didactic development projects, revealing fragmented understanding primarily focused on action-oriented, fact-based, and normative aspects of sustainability. The teachers emphasised waste sorting, recycling, and nature experiences, with limited attention to holistic and pluralistic perspectives. Despite curriculum mandates, sustainability had low implementation in ECE educational plans and collaboration meetings. The findings highlight the need for comprehensive teacher education and support to promote EfS and foster agents for sustainability in the context of ECE.

Introduction

Sustainability is a normative value system with three moral imperatives: satisfying human needs, ensuring social justice, and respecting environmental limits (Holden et al. Citation2017). Thus, Education for Sustainability (EfS) is motivated by a need for an education that empowers children of all ages with knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes to address the global challenges we face (Chen and Liu Citation2020; Van Poeck, Östman, and Öhman Citation2019). This motivation implies a deep understanding and adherence to the principles and aims of sustainability, such as empowering children with agency, empowerment, and action competence. The latter is an educational ideal that is closely connected to democratic and political education, as well as related to solving controversial problems in various domains (Mogensen and Schnack Citation2010; Sass et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, according to the 2030 Agenda, of the UN, children are considered as critical ‘agents of change’, which is enhanced by transformative education to support their experiences in discovery, participation, and agency of change (Rieckmann Citation2018). Therefore, EfS should not only provide fact-based knowledge about sustainability, but also involve a learning arena where children can experience the ability to influence the environment or local community (Van Poeck, Östman, and Öhman Citation2019).

In recent decades, many European countries have integrated sustainability into early childhood education (ECE) and school curricula. In Norway, sustainability has been part of the national ECE framework plan (hereafter, curriculum) for many years. In the last revision, sustainability has gained a significant place as a core value; thus, sustainability is relatively explicitly stated compared to other countries’ curricula (Weldemariam et al. Citation2017). Consequently, it should be integrated into all pedagogical and didactic work in ECE (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2017). The ECE curriculum states that ECEs shall ‘promote democracy, diversity, mutual respect, equality, sustainable development, life skills, and health’ (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2017, 7). Furthermore, ECEs shall, by fostering the children’s ability to think critically, act ethically, and show solidarity, enable them to understand that their actions today have consequences for the future (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2017, 10). In addition, the ECE teachers are responsible for children gaining ‘knowledge about nature and sustainability, learning from nature, developing respect, and beginning understanding of how they can take care of nature’ (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2017, 52).

ECE teachers play an essential role in the development of sustainability understanding in children and, ultimately, in their awareness and interest in living sustainability. Dewey claims that, ‘Teachers are the agents through which knowledge and skills are communicated and rules of conduct enforced’ (Dewey Citation1916). The teacher’s responsibility involves the selection and delivery of specific content, while also guiding and directing children toward a deeper understanding of the subject matter. The curriculum provides the framework within which teachers make their choices. As a result, teachers should possess the knowledge to select appropriate didactic practices for a particular subject and comprehend which content is appropriate within the boundaries established by the children, their ECE institution, and society (Öhman and Sund Citation2021).

The decisions made by teachers in their didactic practice are described as ‘teacher moves’ (Östman, Van Poeck, and Öhman Citation2019; Öhman and Sund Citation2021), which refer to the various actions a teacher takes to facilitate a conducive learning environment for the children. These moves are based on the teacher’s choices regarding the content and methods used, and on their rationale for these choices. In EfS, three main teaching traditions and orientations have been recognised, fact-based, normative, and pluralistic (Borg et al. Citation2014; Hedefalk, Almqvist, and Östman Citation2015; Rudsberg and Öhman Citation2010; Öhman and Östman Citation2019). Even if these teaching traditions not necessarily contradict each other, the fact-based tradition is criticised for omitting sustainability values, and the normative tradition focuses on the socialisation of predetermined norms and values. In contrast, pluralistic traditions focus on the ability of children to critically evaluate and take a stand on sustainability issues; it supports democratic competence (Öhman and Östman Citation2019). However, pluralistic traditions are also criticised for having an anthropocentric viewpoint without including environmental ethics (Kopnina Citation2012).

Thus, EfS should emphasise developing children’s critical thinking ability and seeing connections (Borg et al. Citation2014). However, the didactic plans and practices of the ECE teachers are often associated with play-based, nature-rich educational approaches, including movement in nature, social interaction, observation, and conversation without dealing with explorative questions and dilemmas (Yıldız et al. Citation2021; Ardoin and Bowers Citation2020). Although positive childhood experiences in nature are associated with increasing environmental commitment and sensible environmental behaviour (Chawla and Cushing Citation2007; Chawla Citation2009; Chawla Citation2020; Rosa, Profice, and Collado Citation2018), and both unstructured and structured activities in nature increase children’s environmental knowledge while positively affecting their cognitive, social, and emotional development (Ardoin and Bowers Citation2020). Nevertheless, researchers have argued that outdoor activities do not automatically lead to engagement in sustainability issues (c.f. Moen and Vårnes Citation2019; Elliott and Young Citation2016). Van Poeck, Östman, and Öhman (Citation2019) highlight the need to include problem-solving in EfS and the teacher’s responsibility in designing arenas where the children’s perspectives, knowledge, and values are recognised as resources (Caiman and Lundegård Citation2014). Furthermore, earlier empirical research has shown the importance of activities that involve imagination and creativity in children’s meaning-making processes (Caiman and Lundegård Citation2018; Caiman, Hedefalk, and Ottander Citation2022) and hence teachers’ ability to listen to children’s ideas carefully is essential (Davies Citation2011; Luff Citation2018). In this sense, inquiry-based learning is vital to creating interconnectedness and a deeper understanding of sustainability issues in ECE (Ampartzaki, Kalogiannakis, and Papadakis Citation2021). Öhman and Sund (Citation2021) also highlight EfS practices that promote sustainability commitment at the intersection of intellectual, emotional, and practical dimensions (Dewey 1934/1980/2005). It posits that the intellectual aspect is crucial in grounding the commitment with scientific rigour and critical thinking, while emotions play a vital role in fostering children’s dedication. Additionally, the ability to enact appropriate actions for change is necessary to contribute to a sustainable societal transformation. Taken together, this reflects agency, which is assumed to play a pivotal role in enabling children to construct meaning in connection with inquiries about sustainability (Caiman and Lundegård Citation2014).

Previous research on teachers and their didactical practices indicates that teachers who comprehend and internalise concepts beyond sustainability adopt a more expansive approach to teaching and learning. Conversely, a limited understanding is often linked to narrower teaching methodologies (Borg et al. Citation2014). Previous research has also shown that ECE teachers often view sustainability as dealing with fragmented issues and are primarily associated with ecological concerns rather than from a holistic perspective, including all dimensions, environmental, social, and economic (Borg, Winberg, and Vinterek Citation2017; Borg and Gericke Citation2021; Birdsall Citation2014). Earlier studies in Norwegian ECE contexts also find that sustainability is mainly given a one-dimensional understanding (Grindheim et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, Håberg, Ryslett, and Høydalsvik (Citation2023) and Sageidet (Citation2014) have found that implementation processes take time, and EfS-related activities are action-oriented and primarily based on existing didactic practices. Studies on ECE teachers’ understandings and practices in EfS in Japan, Australia, and Korea also support these findings (Inoue, O’Gorman, and Davis Citation2016; Inoue et al. Citation2017).

Hedefalk et al. (Citation2021) highlight that the (student) teacher must be able to stand in the tension between the curriculum’s mandates, the EfS didactical practice, and the child’s participation. Lave and Wenger (Citation1991) emphasise that in implementation processes, teachers must be motivated, supported, and foster professional communities of practice and teams, which we expect will also apply to the implementation of sustainability. Thus, in this study, we have chosen a collaborative design approach. The teacher works closely with their team, and we can examine the understanding and practice of sustainability in organisational and professional ECE practice contexts, following e.g. Ertesvåg and Roland (Citation2013).

According to this, didactic choices (how and what) and didactic reason (why) in EfS would depend on the conceptual understanding of sustainability by teachers and how it is implemented in ECE institutions. Thus, we need information on how ECE teachers in a co-created learning process between peers express their conceptual understanding of sustainability and how they translate it into didactics. Therefore, this study investigates the teacher’s understanding of sustainability and how their daily pedagogical practices in education for sustainability become evident to children in ECE. Furthermore, we want to determine whether the sustainability concept is implemented in local ECE curricula and professional collaboration. Therefore, our specific research question is as follows.

What understandings are expressed regarding sustainability for ECE teachers in the Norwegian ECE context?

Materials and methods

Study context and participants

We collected data in autumn 2020, 2021 and 2022 from ECE teachers () representing 35 geographically distributed ECE institutions. In a Norwegian context, we define a teacher in ECE as someone who has completed a bachelor’s degree and is a leader for a defined group of children aged 1–5 years and other staff members. All participants attended different part-time professional development courses about EfS at the same teacher education institution. Parallelly through the further education courses, all participants worked as ECE teachers in their respective ECEs.

Table 1. Information about ECE institutions and participants.

Participation was voluntary. Participants signed informed consent and data were processed anonymously.

Data collection

The study used an exploratory sequential mixed method design (Creswell and Guetterman Citation2021), where we, as researchers, had an objective role. The data used in this study were from the initial stage of the part-time professional development course for teachers to map the current situation in the ECE institutions according to the understanding of the sustainability of ECE teachers, the practice of EfS and the implementation of EfS in the ECE institutions. In one of the part-time professional development courses, data was also collected from the required sustainability coursework of the participants (see Sequence 3). The teachers participated in three data collection sequences that will be interpreted as an integrated part of our mixed-method design. Sequence 1 was a reflection note from each institution to which the participants belonged (n = 20). Teachers were encouraged to ask another pedagogical employee in their ECE institution and together brainstorm and generate five core concepts about their overall understanding of the sustainability concept in daily ECE practice. In our mixed methods design, these reflection notes were chosen as an alternative to interviews with only one in each institution. The intention was that the reflection notes would work as interventional questions for the entire personnel group in each of the twenty institutions.

In Sequence 2, teachers participated in a small-scale survey to map understanding and current practices related to EfS in the ECE institution (n = 35). The survey had claims evaluated by participants using a five-point Likert scale with answer options ‘strongly disagree’, ‘disagree’, ‘agree nor disagree’, ‘agree’ and ‘strongly agree’. The survey was inspired by the sustainability mapping tool developed by OMEP. As this was the second sequence of our mixed method design, participants were encouraged to let the survey become part of the staff meeting in their ECE-institution. Data on age range, seniority range and number of participating teachers were collected (). The survey claims were divided into three parts: first (C1–3) was about understanding sustainability, second (C4–5) was about didactic practice in sustainability, and third (C6–8) was about what place sustainability has in ECE as an organization.

Finally, in sequence 3, teachers were asked to plan and carry out an activity involving children in the environmental dimension of sustainability as a didactic development project (n = 28). This project was limited to the environmental dimension of sustainability for practical and professional reasons. The teachers were asked to submit a written report that showed the theme of the activity, how it was to be carried out, and reflections related to the actual implementation and didactic choices. As researchers, we followed the plan and implementation period of the participants in each of the participating ECE institutions (n = 28).

These three sequences together build our mixed methods design in which the 20–35 participating ECE teachers represent processes in reflections, didactic planning, and implementation of pedagogical development work. Although the sample size is small from a quantitative approach, the cooperation structure means that we have gained insight into the conceptual understanding and implementation from a larger selection of ECE teachers (in the Norwegian context, rough estimate on 175 ECE teachers, see ).

Analysis

The data came from three sources: (1) reflection note with core concepts given by a colleague (n = 11/9, 2021 and 2022), (2) the survey (n = 15/11/9, 2020, 2021 and 2022 respectively), and (3) the didactic developmental project in the ECEs (n = 19/9, 2021 and 2022).

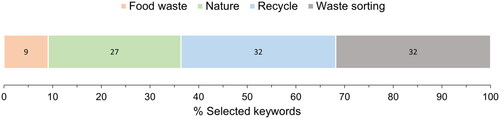

To obtain thematic overviews of the core concepts (100 in total) of the participants and what they associated with sustainability related to daily practice in ECE, the data were analysed by Bryman’s four stages of qualitative data analysis (Bryman Citation2008) by reading and rereading, categorising, and recategorising, coding, and recoding, before building a hierarchical matrix of codes. For each core concept, we independently suggested a set of categories that identify common themes in the expressed view of the respondents. During this iterative process, we first ended up with 23 categories named (1) waste sorting, (2) recycling, (3) food waste, (4) learn about biodiversity, (5) nature conservation, (6) nature experience, (7) consumer society, (8) future-oriented thinking, (9) learn about the weather, (10) less waste, (11) food production, (12) equality, (13) health promotion, (14) plastic reduction, (15) knowledge development, (16) development of the will, (17) attitudes and values, (18) resource reduction, (19) future opportunities, (20) organic food, (21) reduce pollution, (22) nature as a playground, and (23) natural materials. We counted the number of times (frequency) each participant’s core concept fits into each category. We decided to report the results of the initial stage of the analysis to show the whole variation in the core concepts, as presented in . Still, in the last stage, we ended up with four parent codes named (1) waste sorting, (2) recycling, (3) nature-related content and (4) food waste and counted the number of times each participant’s core concept fits into the parent code names, as presented in . All researchers had an equal role in analysing the core concept from the reflection notes.

Figure 1. Word cloud showing frequency (proportional letter size) of the 23 categories of core concepts from the first iterative coding process.

Figure 2. Percentage distribution (numbers in bar chart) of keywords in four parent codes from the last iterative coding process.

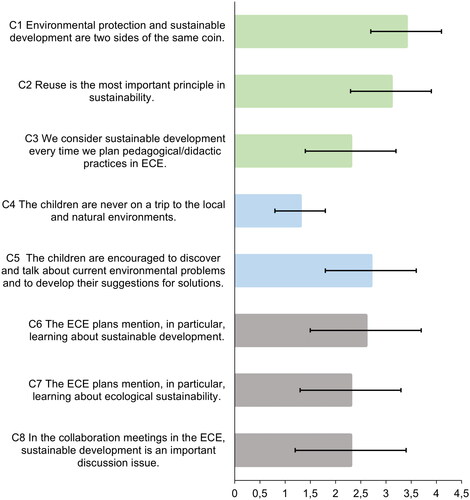

Quantitative information from the survey was numerically coded: 1 = strongly disagrees, 2 = moderately disagrees, 3 = moderately agrees, 4 = strongly agrees, 0 = do not know. Mode, mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated (Creswell and Guetterman Citation2021). Due to the few participants (low N), only descriptive statistics were presented using non-transformed data ().

Figure 3. Mean (±SD) of an agreement to claims presented in the survey. Green bars (C1–3) concern the understanding of sustainability, blue bars (C4–5) concern didactic practice in sustainability, and grey bars (C6–8) concern what place sustainability has in ECE as an organisation.

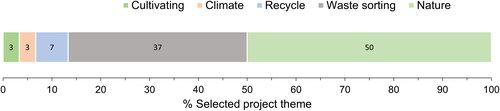

Furthermore, information on selected development projects of institutions was again analysed using Bryman (Citation2008) four stages of qualitative data analysis (Bryman Citation2008). We read through the written report and re-reading, categorising, and re-categorising, coding, and recoding, before a hierarchical matrix of codes was constructed. We sorted the data into four categories and in this data-driven process, these four categories became visible and interpreted as their sustainability selections of the development project theme: (1) reuse, (2) climate, (3) explore nature, and (4) waste/recycling (). We also analysed the didactic practice which became visible when the ECE teachers had to carry out the activity. We read through the written report and re-reading, categorising, and re-categorising, coding, and recoding, before a hierarchical matrix of codes was constructed. We ended up with four categories: (1) practice that emphasised observation and conversation by the child, (2) posing questions and encouraging reflections by the child, (3) appeal to the senses and create wonder, and (4) inquiry-based learning. All researchers had an equal role in analysing the content of the development projects.

Results

Understanding of the sustainability concept

The results of the first iterative analysis process showed that waste sorting and recycling were mainly associated with ECE teachers’ understanding of the concept of sustainability in daily practice, with 19% and 18% of the core concepts generated, respectively. Nature-related content, such as nature conservation, biological diversity, and nature experience, was generated in 5% of the core concepts. Sustainability as a change-maker concept, such as knowledge, development of will, equality, attitudes, and values, was generated in 2% of the core concepts (). The results from the last stages of our data analysis showed that waste sorting, recycling, nature, and food waste with 32%, 32%, 27%, and 9% of the core concepts generated, respectively ().

Teachers’ statements on sustainability in ECE

There was an overall conception that the environment was synonymous with sustainability and reuse was the most important principle in sustainability (C1: Mean = 3.4, SD = 0.7, mode = 4, n = 20; C2: Mean = 3.1, SD = 0.8, mode = 3, n = 20), but the teachers evaluated the degree of implementation in the didactic plans as low (C3: Mean = 2.3, SD = 0.9, mode = 2, n = 20). The physical practices involved trips to the local environment and nature areas (high disagreement with C4: Mean = 1.3, SD = 0.5, mode = 1, n = 35), and the practices also involved children engaging in discoveries, conversation, and solutions to current environmental problems (C5: Mean = 2.7, SD = 0.9, mode = 3, n = 35). Teachers evaluated the degree of sustainability implementation in plans and collaborations meetings as low (C6: Mean = 2.6 SD = 1.1, mode = 3 n = 20; C7: Mean = 2.3, SD = 1, mode = 3, n = 35; C8: Mean = 2.3, SD = 1.1, mode = 1, n = 20). For more information, see .

Choice of theme in didactic development project

Teachers were free to concretise whatever theme within the environmental dimension for their own didactic developmental project to carry out in their ECE. The results showed that when the teachers chose activities, 50% chose activities related to nature, 36% had activities related to waste sorting, 7% related to recycle and only 3% chose activities related to climate or cultivation (). The teachers planned activities that emphasised observation and conversation by the child as a didactic practice in 80% of the selected activities, posing questions and encouraging reflections by the child was selected in 12% of the activities, appeal to the senses and create wonder was selected in 4% of the activities and inquiry-based learning was expressed as a didactic practice in 4% of the activities.

Discussion

Based on teachers’ reflection notes, reported didactic development projects and the survey, our findings indicate that the teacher’s understanding of sustainability is given a fragmented, activity-oriented, and fact-based, normative understanding and to a lesser extent is related to sustainability as pluralistic teaching tradition (). Although nature is highlighted as important with respect to the environmental dimension of sustainability (), it does not seem to be equally important in the overall understanding of sustainability ( and ). The result of our survey shows a general low implementation of sustainability in local steering documents and collaboration processes (). Our conclusion is that teacher education to a greater degree must integrate sustainability into ECE teacher education, and the teachers must have the ability to develop their didactic practice.

The teachers’ expressions about sustainability showed a fragmented understanding, mainly focused on a few individual, normative, and fact-based actions ( and ). This expression about sustainability suggests that teachers should gain agency thinking and a more critical awareness of sustainability as a concept for transformative education. Our findings show a need for what we interpret as sustainable awareness and what this means for ECE teachers’ practical choice of activities and content in their didactic activities (teacher moves). The complex and complicated concept of sustainability is simplified into an answer that contains only a few simple explanations. Our results correspond to previous Nordic and international studies (Birdsall Citation2014; Håberg, Ryslett, and Høydalsvik Citation2023; Inoue, O’Gorman, and Davis Citation2016; Inoue et al. Citation2017). However, these findings contradict the curriculum mandate, which states that ECE should promote the children’s ability to think critically, act ethically and show solidarity, thus promoting values, attitudes, and practices for more sustainable local communities, which is in accordance with agency making (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2017, 10; Caiman and Lundegård Citation2014). Öhman and Sund (Citation2021) highlight the need for a didactic practice that encourages the development of sustainability commitment, where EfS didactics should not only present knowledge and practical aspects but encourage responding to feelings and concerns and constructively try to manage and cope with feelings.

In this study, we found that most ECE teachers explain sustainability in an action-oriented way. We interpret our results to see an understanding of sustainability that to a lesser extent provokes holistic and pluralistic thinking in teachers (). The results of the survey on the teachers’ understanding of sustainability () and how it translates into the didactic work () reinforce the findings from the core concepts ( and ) where sustainability is broken down into individual action-oriented concepts. The teachers we have followed need to distinguish between environmental protection and sustainability in a better way, since they look at it as two sides of the same coin. The results show that reuse is the most crucial principle in sustainability (), consistent with the choice of project development theme delimited to the environmental dimension in sustainability (). As we interpret it, this dimension is principally accessible for teachers to transfer from ‘understanding’ to ‘ECE didactics’, as it may be following earlier practices before sustainability was a substantial part of the curriculum. This finding contradicts the concept of action competence within EfS which emphasises knowledge (e.g. individual and societal norms and critical reflection), willingness (e.g. commitment and passion), and confidence (e.g. outcome expectancy and efficacy expectations) in sustainability (Sass et al. Citation2020). This concept is also closely related to sustainability commitment, as Öhman and Sund (Citation2021) stated. This concept is built on Dewey’s pragmatic perspective, where a comprehensive learning journey comprises a sequence of interconnected elements or facets, wherein disciplinary knowledge alone falls short in addressing situations that require empathy towards someone or something (Dewey Citation1934/1980, Citation2005). Therefore, to have a successful EfS, children must be challenged to become sustainability agents (Rieckmann Citation2018; Van Poeck, Östman, and Öhman Citation2019). More than three decades have passed since the concept of sustainability became part of joint European states strategies (Holden et al. Citation2017) and thus has become a part of the curriculums in ECE and schools. A somewhat unexpected finding is that sustainability is still, to some extent, an action-oriented concept that only weakly activates the ECE teachers’ values and attitudes. Following Borg et al. (Citation2014), we ask whether a successful EfS is possible without the conceptual understanding of sustainability by ECE teachers.

In part of the part-time professional development courses, we challenged teachers to develop a didactic development project on the environmental dimension of sustainability. Our results showed that the choice of project development theme () followed the general knowledge of sustainability ( and ). However, activities in natural environments received more attention, and our survey results substantiate that trips to natural environments (for example, forests and rocky tidal zones) are an essential part of daily practice in Norwegian ECE (). Our results show that teachers usually plan activities that emphasise observation, but use inquiry-based learning to a lesser extent. However, the results of the survey show that the didactic practice, in relatively many cases, invites children to discover and discuss environmental problems and come up with suggestions for solutions (). Although this reflects a crucial didactic practice, we question whether it is enough to develop children’s action competence or commitment to sustainability (Sass et al. Citation2020; Öhman and Sund Citation2021). The ECE teachers primarily break sustainability down into dealing with waste sorting, recycling, and simple trips to natural environments. One explanation for our results could thus be that ECE teachers perceive sustainability as environmental problems seeking a solution, not as a concept of seeing ecological connections, a deeper understanding of nature, which invites to critical thinking and reflections. Thus, this view primarily supports the dominant post-industrial neoliberal anthropocentric discourse that sees sustainability as dealing with human needs without including the intrinsic values of non-human species or nature (Kopnina Citation2012). Teachers primarily link their didactic practice in EfS to an already established practice and do not consider sustainability a concept requiring a new practice and way of thinking. Although the ECE curriculum expressly states that teachers must promote children’s critical thinking skills (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2017, 10) and that children should gain knowledge about nature and sustainability, learn from nature, develop respect, and begin to understand how they can take care of nature (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2017, 52).

Successful EfS depends on teachers’ motivation, commitment, or knowledge of EfS and the organisational and professional elbow room for ECE practice (Borg, Winberg, and Vinterek Citation2017; Borg and Gericke Citation2021). Our results show that sustainability as a general concept and the environmental dimension have a low implementation in the educational plans of ECE ( and ). Additionally, our results indicate that the critical discussion about sustainability as part of collaboration meetings at ECE is not very common (). These findings follow earlier studies from, e.g. Sweden and Germany (Engdahl, Samuelsson, and Ärlemalm-Hagser Citation2021; Singer-Brodowski et al. Citation2019) where EfS is described as ‘business as usual’ rather than treating EfS as a new field. The small degree of implementation may be an essential explanation for our findings; if sustainability implementation is low in the ECE institution, it will also negatively influence the teacher’s commitment, motivation, and knowledge of sustainability. Therefore, we must expect teachers to refrain from developing their understanding or changing didactic practices related to sustainability, too. Successful implementation requires educational institutions to have a concrete vision for EfS (Bascopé, Perasso, and Reiss Citation2019; Boeve-de Pauw et al. Citation2015; Andersson Citation2017). A future goal should therefore focus more on supporting teachers in these processes to achieve a successful implementation in Norwegian ECE practices. In our sample, where teachers have worked in ECE for several years, they must develop a critical conceptual approach to sustainability. Hopefully, the implementation is underway, and teachers understand and act against the new requirements that the 2017 national curriculum gave them. Our interpretation, however, is that they are still only at an early stage in these processes six years after the implementation.

In conclusion, we underscore the pedagogical implications for teacher education. Policymakers and teacher educators are responsible for fostering and nurturing EfS competence in ECE and schools. Therefore, teacher education must undergo a substantial transformation, encompassing a significantly deeper integration of EfS than is currently practised. This shift carries immediate pedagogical ramifications, as educators must be well-informed about the formal mandate to prioritise sustainability education. From an agency perspective, the overarching objective is to stimulate agents of sustainability (Rieckmann Citation2018). EfS should empower children as catalysts for change in their early years and challenge established educators to elevate their consciousness regarding sustainability dilemmas while pursuing ongoing professional development.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank all the teachers who participated voluntarily in the study. We are also grateful to the editors and reviewers for their constructive and valuable comments on this paper.

Disclosure statement

The authors report that there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Ampartzaki, M., M. Kalogiannakis, and S. Papadakis. 2021. “Deepening Our Knowledge about Sustainability Education in the Early Years: Lessons from a Water Project.” Education Sciences 11 (6): 251. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11060251

- Andersson, K. 2017. “Starting the Pluralistic Tradition of Teaching? Effects of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) on Pre-Service Teachers’ Views on Teaching about Sustainable Development.” Environmental Education Research 23 (3): 436–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1174982

- Ardoin, N. M., and A. W. Bowers. 2020. “Early Childhood Environmental Education: A Systematic Review of the Research Literature.” Educational Research Review 31: 100353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100353

- Bascopé, M., P. Perasso, and K. Reiss. 2019. “Systematic Review of Education for Sustainable Development at an Early Stage: Cornerstones and Pedagogical Approaches for Teacher Professional Development.” Sustainability 11 (3): 719. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030719

- Birdsall, S. 2014. “Measuring Student Teachers’ Understandings and Self-Awareness of Sustainability.” Environmental Education Research 20 (6): 814–835. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.833594

- Boeve-de Pauw, J., N. Gericke, D. Olsson, and T. Berglund. 2015. “The Effectiveness of Education for Sustainability Development.” Sustainability 7 (11): 15693–15717. https://doi.org/10.3390/su71115693

- Borg, C., N. Gericke, H.-O. Höglund, and E. Bergman. 2014. “Subject-and Experience-Bound Differences in Teachers’ Conceptual Understanding of Sustainability.” Environmental Education Research 20 (4): 526–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.833584

- Borg, F., and N. Gericke. 2021. “Local and Global Aspects: Teaching Social Sustainability in Swedish Preschools.” Sustainability 13 (7): 3838. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073838

- Borg, F., M. Winberg, and M. Vinterek. 2017. “Children’s Learning for a Sustainable Society: Influences from Home and Preschool.” Education Inquiry 8 (2): 151–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2017.1290915

- Bryman, A. 2008. Social Research Methods. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Caiman, C., M. Hedefalk, and C. Ottander. 2022. “Pre-School Teaching for Creative Processes in Education for Sustainable Development – Invisible Animal Traces, Purple Hands, and an Elk Container.” Environmental Education Research 28 (3): 457–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.2012130

- Caiman, C., and I. Lundegård. 2014. “Pre-School Children’s Agency in Learning for Sustainable Development.” Environmental Education Research 20 (4): 437–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2013.812722

- Caiman, C., and I. Lundegård. 2018. “Young Children’s Imagination in Science Education and Education for Sustainability.” Cultural Studies of Science Education 13 (3): 687–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-017-9811-7

- Chawla, L. 2009. “Growing up Green: Becoming an Agent of Care for the Natural World.” The Journal of Developmental Processes 4 (1): 6–23. https://naaee.org/eepro/research/library/growing-green-becoming-agent-care

- Chawla, L. 2020. “Childhood Nature Connection and Constructive Hope: A Review of Research on Connecting with Nature and Coping with Environmental Loss.” People and Nature 2 (3): 619–642. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10128

- Chawla, L., and D. F. Cushing. 2007. “Education for Strategic Environmental Behavior.” Environmental Education Research 13 (4): 437–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620701581539

- Chen, S.-Y., and S.-Y. Liu. 2020. “Developing Students’ Action Competence for a Sustainable Future: A Review of Educational Research.” Sustainability 12 (4): 1374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041374

- Creswell, J. W., and T. C. Guetterman. 2021. Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Vol. 6. Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited.

- Davies, B. 2011. “Open Listening: Creative Evolution in Early Childhood Settings: OMEP XXVI World Conference, August 11–13, 2010, Gothenburg, Sweden.” International Journal of Early Childhood 43 (2): 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-011-0030-1

- Dewey, J. 1916. “Democracy and Education.” Schools 5 (12): 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1086/591813

- Dewey, J. 1934/1980. Art as Experience. New York, NY: Perigee Books.

- Dewey, J. 2005. Art as Experience. New York, NY: Perigee Books (First edition 1934).

- Elliott, S., and T. Young. 2016. “Nature by Default in Early Childhood Education for Sustainability.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 32 (1): 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/aee.2015.44

- Engdahl, I., P. Samuelsson, and E. Ärlemalm-Hagser. 2021. “Swedish Teachers in the Process of Implementing Education for Sustainability in Early Childhood Education.” New Ideas in Child and Educational Psychology 1 (1): 3–23. https://doi.org/10.11621/nicep.2021.0101

- Ertesvåg, S. K., and P. Roland. 2013. Ledelse av endringsarbeid i barnehagen. Oslo, Norway: Gyldendal akademisk.

- Grindheim, L. T., Y. Bakken, K. H. Hauge, and M. P. Heggen. 2019. “Early Childhood Education for Sustainability through Contradicting and Overlapping Dimensions.” ECNU Review of Education 2 (4): 374–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/2096531119893479

- Håberg, L. I. A., K. Ryslett, and T. Høydalsvik. 2023. “How Kindergarten Teachers Support Nascent Understanding of Sustainability among Children: A New Label on an Old Practice?” Nordic Early Childhood Educational Research 19 (3): 203–222.

- Hedefalk, M., J. Almqvist, and L. Östman. 2015. “Education for Sustainability in Early Childhood Education: A Review of the Research Literature.” Environmental Education Research 21 (7): 975–990. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2014.971716

- Hedefalk, M., C. Caiman, C. Ottander, and J. Almqvist. 2021. “Didactical Dilemmas When Planning Teaching for Sustainable Development in Preschool.” Environmental Education Research 27 (1): 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2020.1823321

- Holden, E., K. Linnerud, D. Banister, V. J. Schwanitz, and A. Wierling. 2017. The Imperatives of Sustainability: Needs, Justice, Limits. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Inoue, M., L. O’Gorman, and J. Davis. 2016. “Investigating Early Childhood Teachers’ Understandings of and Practices in Education for Sustainability in Queensland: A Japan-Australia Research Collaboration.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 32 (2): 174–191. https://doi.org/10.1017/aee.2016.4

- Inoue, M., L. O’Gorman, J. Davis, and O. Ji. 2017. “An International Comparison of Early Childhood Educators’ Understandings and Practices in Education for Sustainability in Japan, Australia, and Korea.” International Journal of Early Childhood 49 (3): 353–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-017-0205-5

- Kopnina, H. 2012. “Education for Sustainable Development (ESD): The Turn Away from ‘Environment’ in Environmental Education?” Environmental Education Research 18 (5): 699–717. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2012.658028

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Luff, P. 2018. “Early Childhood Education for Sustainability: Origins and Inspirations in the Work of John Dewey.” Education 3-13 46 (4): 447–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2018.1445484

- Moen, C. H., and T. K. Vårnes. 2019. “Å leve i samklang med naturen -lettere sagt enn gjort!.” In Bærekraft i praksis i barnehagen, edited by I V. Bergan and K. E. W. Bjørndal, 37–51. Oslo, Norway: Universitetsforlaget.

- Mogensen, F., and K. Schnack. 2010. “The Action Competence Approach and the ‘New’ Discourses of Education for Sustainability, Competence, and Quality Criteria.” Environmental Education Research 16 (1): 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620903504032

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. 2017. "Framework Plan for Kindergartens: Contents and Tasks." Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, Norway. https://www.udir.no/globalassets/filer/barnehage/rammeplan/framework-plan-for-kindergartens2-2017.pdf

- Öhman, J., and L. Östman. 2019. “Different Teaching Traditions in Environmental and Sustainability Education.” In Sustainable Development Teaching: Ethical and Political Challenges, edited by K. Van Poeck, L. Östman, and J. Öhman, 70–81. Milton: Routledge.

- Öhman, J., and L. A. Sund. 2021. “Didactic Model of Sustainability Commitment.” Sustainability 13 (6): 3083. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063083

- Östman, L., K. Van Poeck, and J. Öhman. 2019. “A Transactional Theory on Sustainability Teaching: Teacher Moves.” In Sustainable Development Teaching: Ethical and Political Challenges, edited by K. Van Poeck, L. Östman, and J. Öhman, 126–137. Milton: Routledge.

- Rieckmann, M. 2018. “Learning to Transform the World: Key Competencies in Education for Sustainable Development.” In Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development, edited by A. Leicht, J. Heiss, and W. J. Byun, 39–59. Paris, France: UNESCO Publishing.

- Rosa, C. D., C. C. Profice, and S. Collado. 2018. “Nature Experiences and Adults’ Self-Reported Pro-Environmental Behaviors: The Role of Connectedness to Nature and Childhood Nature Experiences.” Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1055. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01055

- Rudsberg, K., and J. Öhman. 2010. “Pluralism in Practice: Experiences from Swedish Evaluation, School Development and Research.” Environmental Education Research 16 (1): 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620903504073

- Sageidet, B. M. 2014. “Norwegian Perspectives on ECEfS: What Has Developed since the Brundtland Report?.” In Research in Early Childhood Education for Sustainability, edited by J. Davies and S. Elliott, 112–124. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Sass, W., J. Boeve-de Pauw, D. Olsson, N. Gericke, S. De Maeyer, and P. Van Petegem. 2020. “Redefining Action Competence: The Case of Sustainable Development.” The Journal of Environmental Education 51 (4): 292–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2020.1765132

- Singer-Brodowski, M., A. Brock, N. Etzkorn, and I. Otte. 2019. “Monitoring of Education for Sustainable Development in Germany–Insights from Early Childhood Education, School and Higher Education.” Environmental Education Research 25 (4): 492–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2018.1440380

- Van Poeck, K., L. Östman, and J. Öhman. 2019. Sustainable Development Teaching: Ethical and Political Challenges. Milton: Routledge.

- Weldemariam, K., D. Boyd, N. Hirst, B. M. Sageidet, J. K. Browder, L. Grogan, and F. Hughes. 2017. “A Critical Analysis of Concepts Associated with Sustainability in Early Childhood Curriculum Frameworks across Five National Contexts.” International Journal of Early Childhood 49 (3): 333–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-017-0202-8

- Yıldız, T. G., N. Öztürk, T. İ. İyi, N. Aşkar, Ç. Banko Bal, S. Karabekmez, and Ş. Höl. 2021. “Education for Sustainability in Early Childhood Education: A Systematic Review.” Environmental Education Research 27 (6): 796–820. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.1896680