ABSTRACT

This study addressed the concept of ‘intersectionality’ relating to refugee status and disability. It examined whether differences in attitudes depending on disability type (physical disability vs. behavioural disorders) are present and how the refugee status and disability in girls interact to influence attitudes. The attitudes of 1377 participants towards the inclusion of Austrian girls with disabilities as well as of refugee girls with and without disabilities into a mainstream primary school were assessed. The respondents read a short description of a particular girl before answering a short questionnaire.

In general, the respondents showed more positive attitudes towards the inclusion of Austrian girls into a mainstream primary school than towards the inclusion of refugee girls. Furthermore, attitudes were more positive towards the inclusion of girls with a physical disability than towards the inclusion of girls with behavioural disorders, regardless of the refugee status. Due to the entanglements of the disability type and refugee status demonstrated in this research, it seems clear that no pure ‘disability effect’ or ‘refugee effect’ is evidenced when examining attitudes about inclusive education. Rather, both aspects should be considered simultaneously. Furthermore, respondents’ gender, educational level and cultural capital also influenced the attitudes.

Introduction

In 2014, 28,027 people had applied for asylum in Austria. By 2015, this number had reached 88,912. Most of these people fled wars in Syria or Afghanistan (BMI Citation2017a). Out of these applications, 14,233 came from children enrolled in schools in Austria, a country where education is mandatory for every child resident aged between 6 and 15 years, which includes refugee children as well (BMB Citation2016). Although data regarding numbers of refugees in Austrian schools exist, the data does not allude to the age group, country of origin, gender or disability. To provide adequate support, however, data regarding disability is sorely needed (Crock, Ernst, and McCallum Citation2013). The lack of data, as Crock, Ernst, and McCallum (Citation2013) note, demonstrates the neglect that disability research has received in the area of migration studies. Nevertheless, as Pisani and Grech (Citation2015, 422) point out, ‘sheer numbers of disabled people’ exist within each population group, which can also be applied to refugees (WHO Citation2011; UNHCR Citation2016). A project by HelpAge International and Handicap International (Citation2014), for example, claims that around 30% of Syrian refugees in Lebanon and Jordan have a disability. Furthermore, the UNHCR states that out of the 65 million forcibly displaced persons in 2016, almost 10 million have a disability (OHCHR Citation2017).

The idea that people can belong to two or more subordinated social groups (e.g. refugees with a disability) simultaneously ‘and suffer aggravated and specific forms of [prejudice and] discrimination in consequence’ (Makkonen Citation2002, 1) is termed intersectionality (Crenshaw Citation1989). Although intersectionality has historically focused on how race, gender and class (Crenshaw Citation1989, Citation1991) intersect and pose certain challenges to African American women, many other groups are affected by intersectional discrimination as well, such as refugee girls with disabilities.

An emphasis on the category of refugee girls with disabilities is important for three reasons. First, since 2015, there has been an influx of refugees arriving in Europe. Second, research shows that having a disability and being female is placing ‘wom[e]n with disabilities in double jeopardy for poverty, unemployment, and a bleak future upon leaving school’ (Rousso and Wehmeyer Citation2001, 2; Lindsay et al. Citation2017). We hold that disadvantaged statuses connected with being female, disabled or belonging to an ethnic minority is rooted in ‘society through pervasive biases, stereotypes, and discrimination’ (Rousso and Wehmeyer Citation2001, 2; Smith-Khan et al. Citation2014). When these stereotypes about girls merge with stereotypes about disability and refugee status, they can result in patterns of intersectional discrimination (Rousso Citation2003; Coleman, Brunell, and Haugen Citation2015). Third, one of the largest barriers to inclusive education for girls with disabilities and/or a refugee status is their invisibility, which is also due to a lack of research focussing specifically on girls (Rousso Citation2003; Taylor and Sidhu Citation2012; Bruneforth et al. Citation2016). This invisibility shows itself in the fact that in Austria boys are 2–3 times more likely to be identified as having special education needs (SEN) than girls (Bruneforth et al. Citation2016). The overestimation of SEN in boys lasts even if gender differences in prevalence rates of disabilities and clinical disturbances are taken into account. Boys are much more likely to receive (needed) resources, whereas girls are identified much later in their educational career (if at all) and are likely to miss out on important resources and adequate support (Arms, Bickett, and Graf Citation2008). According to Cioè-Peña (Citation2017, 907), ‘children who represent intersectional identities are often … left on the margins of inclusive classrooms, schools and society, leaving them in what can be considered as intersectional gap.’

Although scholars have warned against leaving out the experience of refugees with a disability when theorising about migration (Pisani and Grech Citation2015), research on the entanglement of disability and refugee status is scarce (Shaw, Chan, and McMahon Citation2011; Crock, Ernst, and McCallum Citation2013). This paper, aims at examining the intersection of disability and refugee status in girls by exploring general public’s attitudes towards the inclusion of (refugee) girls with(out) disabilities into mainstream primary schools. By examining the attitudes of the general public, this paper not only tries to address this research gap but it also brings disability and forced migration into focus and reframes it within the context of inclusive education. By ignoring this group in research, we would leave ‘a policy vacuum, needs are unattended to, and theory remains undeveloped and perhaps disembodied’ (Pisani and Grech Citation2015, 422).

Researchers have shown that public attitudes are an important factor in implementing inclusive education, affecting not only the adaption of immigrant/refugee students and students with disabilities in society and schools, but also legislation at the governmental level, shaping local policies and school practices (McBrien Citation2005; Scior Citation2011; UNICEF Citation2013). As Burge et al. (Citation2008) note, addressing public views on inclusive education is critical for those wanting to successfully implement it.

Identifying and addressing public attitudes on inclusive education is thus a crucial step in promoting inclusive efforts (Yazbeck, McVilly, and Parmenter Citation2004), particularly of refugee students with a disability. If communities do not embrace their diverse student body, it is likely that schools and many teachers in that community will not embrace them either (Walker, Shafer, and Liams Citation2004). According to Mittler (Citation2006, 2) we cannot forget that ‘those who work in schools are citizens of their society and local community, with the same range of beliefs and attitudes as any other group of people’ and what happens in schools and the educational system ‘is a reflection of the society in which schools function’.

Attitudes in general

Attitudes can be defined as an evaluative disposition directed towards an ‘object’ or a person (Zimbardo and Leippe Citation1991) that is linked to certain expectations and believed consequences (Ajzen and Fishbein Citation1973). Therefore, we understand attitudes towards a particular social group as evaluative tendencies towards members of that group. These attitudes are based on the individuals’ group membership and not on their individual characteristics (Strabac, Aalberg, and Valenta Citation2014). Research shows that various characteristics (e.g. respondents’ levels of education, gender, age) influence attitudes towards certain groups or people (Kunovich Citation2004; O’Rourke and Sinnott Citation2006; Semyonov, Raijman, and Gorodzeisky Citation2008). More precisely, research shows that respondents who were female (Avramidis and Norwich Citation2002; Kalyva, Georgiadi, and Tsakiris Citation2007; De Boer, Pijl, and Minnaert Citation2011), younger (Balboni and Pedrabissi Citation2000; Nowicki and Sandieson Citation2002Citation) and with a higher educational level (Kunovich Citation2004; Semyonov, Raijman, and Gorodzeisky Citation2008) held more positive attitudes towards people with disabilities and migrants.

Although research relating to general public’s attitudes towards people with a refugee status and a disability is scarce, there are a number of studies examining either only the attitudes towards inclusive education of children with disabilities, or investigating attitudes only towards immigrants.

Attitudes towards inclusion of children with disabilities

Numerous studies have found that attitudes of directly involved people (teachers, parents, peers) towards the inclusion of children with disabilities are determined by the nature and severity of the disabilities. The most positive attitudes were found towards children with physical disabilities, followed by children with sensory disabilities and mental disabilities. Negative attitudes were found towards children with behavioural and emotional disorders (Avramidis and Norwich Citation2002; Hastings and Oakford Citation2003; Mand Citation2007; De Boer, Pijl, and Minnaert Citation2010, Citation2011, Citation2012). Therefore, we specifically focus on the two groups: physical disabitilies (most positive attitudes) and behavioural disorders (most negative attitudes).

In addition to the attitudes of those directly involved, the public’s view about inclusive education also facilitates or constrains the implementation of inclusion (Gilmore, Campbell, and Cuskelly Citation2003; Burge et al. Citation2008). Studies on public attitudes replicate the previously mentioned results. A generalisation, however, cannot be easily made because results vary widely between countries. Furthermore, these studies focused mainly on attitudes towards people with intellectual disabilities. Besides the disability type, studies about general public’s attitudes have shown that respondents’ characteristics (gender, age and educational level) also influence the attitudes (Burge et al. Citation2008; Staniland Citation2010; Schwab et al. Citation2012).

Attitudes towards migrants and refugees

Research examining attitudes towards immigrants, especially anti-immigrant ones, is widespread. Research focusing on refugees, particularly children, however, is limited (Bridges and Mateut Citation2014). Moreover, existing research uses the terms ‘immigrants’, ‘refugees’ and ‘asylum seekers’ interchangeably, and ‘migrant’ is used as an umbrella term. Although scholars and the public tend to interchange these terms, this paper uses the term ‘refugee’ for two reasons. First, the data for this paper was gathered on the attitudes towards the inclusion of a Syrian refugee girl into a mainstream primary school. We chose the Syrian nationality due to the current situation in Austria where the majority of refugee children are Syrian (UNHCR Citation2015). Second, the term ‘refugee’ has a specific legal meaning according to the UN (see UNHCR Citation2010).

Although not examining refugees in particular, a current survey of EU Member States provides a clue for how Europeans see foreigners. In this survey, a clear majority saw migration in a negative light. Approximately 60% felt that immigration worsened crime and 42% felt that migrants have a negative impact on taxes and social services (European Social Survey Citation2016). Another study, conducted by the UNHCR (Citation2011), showed that Austrians have an overall negative view of refugees. About 59% of Austrians perceived refugees as more violent and criminal than other migrants in the country, and 69% saw them as a burden for the social system. Refugees were also viewed as less diligent than Austrians; only 19% of the respondents thought that Austrian society could benefit from refugees.

Nevertheless, the perceptions of migrants and refugees have not always been negative (Halilovich Citation2013). In the 1990s, for example, Austria was one of the main recipients of refugees from the former Yugoslavia (Herzog-Punzenberger Citation2003). During this period, around 90,000 people found refuge in Austria (Bauer Citation2008). For this group of refugees, attitudes were generally more positive, and refugees perceived Austria more or less as a safe haven (Halilovich Citation2013).

Since 2014, however, Austrian discourse surrounding the influx of refugees has been predominately negative (Scheibelhofer Citation2017). This negative discourse was present in both the presidential and the parliamentary elections by favouring the conservative party (ÖVP) and the right-wing populists (FPÖ) (The Guardian Citation2017), which firmly controlled the narrative of the election (centred squarely on immigration) (BMI Citation2017b). According to Rydgren (Citation2017), right-wing populists’ ‘overall policy objective is to safeguard the nation’s majority culture and to keep the nation as ethnically homogenous as possible’ (485). This resentment towards immigrants in Austria has also been influencing the education of refugees in the country. Currently, policy debates about how best to include refugee children into the school system largely advocate for solutions based on segregation, not inclusion. Although every child resident in Austria has the right to enrol in the school system, it is not clearly stated that the schooling should be inclusive in its nature.

Keeping this in mind, it is important to note that significant differences exist within the Austrian society regarding attitudes towards refugees. In particular, older persons and persons with low income or a low education level show predominantly negative attitudes towards refugees (Statistik Austria Citation2016). This group feels vulnerable to a supposed loss of status, and refugees are made responsible for it. A difference between rural and urbanised regions within the country also exists. Persons from the bigger cities (Vienna, Graz) show a more positive attitude towards refugees compared to their counterparts in rural areas. A reason for this may be the fact, that persons in cities have more personal contact with refugees and, therefore, show a more positive attitude (Statistik Austria Citation2016).

The mainly negative attitudes towards immigrants in general—and refugees in particular—have been documented in various studies and in various countries (Zick, Küpper, and Wolf Citation2009; Transatlantic Trends Citation2014; Gerhards, Hans, and Schnupp Citation2016). Research on how the receiving society sees refugee children in the context of school, however, remains scarce.

In the school context, most research has focused in a more general manner on migrant children or Second Language (L2) Learners. Teachers’ attitudes towards these groups were both negative (Walker, Shafer, and Liams Citation2004) and positive (Reeves Citation2006; Byrnes, Kiger, and Manning Citation1997). Negative attitudes seemed to be linked to a lack of allocation of resources and the absence of readiness of teachers to deal with children with disabilities and diverse backgrounds. They perceived the children as a burden to classroom management and the cause of discipline problems. A further obstacle was based on the prejudice that children without disabilities and non-migrant children might learn less in classrooms with children with disabilities and migrants (Burge et al. Citation2008; Heckmann Citation2008).

Aim and research questions

This paper is part of a larger research project that examines the general public’s attitudes towards the inclusion of (refugee) children with(out) disabilities into mainstream primary schools. Our aim is to show that belonging to multiple subordinated groups is affecting the attitudes towards members of these groups in a different way.

To shed some light on this topic, the following research questions are addressed:

What are the attitudes of the general public towards the inclusion of (refugee) girls with(out) disabilities into mainstream primary schools and are there differences in attitudes depending on the type of disability (physical disability vs. behavioural disorders)?

Are refugee girls with a disability affected by intersectional discrimination due to their disability and their refugee status when analysing the general public’s attitudes towards the inclusion into mainstream primary schools?

Which variables (type of disability, nationality/refugee status, respondent’s gender, age, educational level, cultural capital) predict attitudes towards the inclusion of (refugee) girls with(out) disabilities into mainstream primary school?

Method

Sample

Attitudes from 1377 people towards the inclusion of a certain girl into mainstream primary school were investigated through a vignette study. This girl was described by one of five different vignettes. Each participant answered questions referring to only one fictional girl. The sample was stratified by age and gender (see procedure section). Respondents’ ages ranged from 16 to 87 years (M = 43.25 years, SD = 15.02) and 53.7% of the participants were female. Participants’ education level (apprenticeship/vocational training: 41%; higher education entrance qualification, GCE A-level equivalent: 21%; university degree: 29%) roughly matches the statistics for the rest of Austria (Statistik Austria Citation2014).

As already mentioned, five different vignettes existed, each describing a certain girl. Hence, there were also five subgroups of respondents (see ). Chi-square analyses showed that there were no differences between these subgroups concerning the distribution of gender (X2 (4) = .876, p = .928) and educational level (X2 (12) = 15.57, p = .212). Additionally, Analysis of Variance revealed no significant difference concerning age, F (4, 1366) = .384, p = .820. These results state that the participants were equally distributed across the five groups. shows the sample distribution within the groups.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for gender, age, and educational level across the respondents for the five vignettes.

Instrument

For this study, we adapted the ‘Attitudes Towards Inclusion Scale’ (ATIS: Schwab et al. Citation2012). This 14-item questionnaire aims to evaluate attitudes towards the inclusion of students with disabilities in primary schools. The 14 statements are referring to the impact that the class might have on the child in question (‘She will acquire social skills in the classroom’), the impact that the child in question might have on the classroom (‘She will have a negative impact on the other students’ performance’) and the effect of the inclusive classroom vs. special education on the child in question (‘She would learn more in a special classroom, where similar children are educated’). Half of the items have a negative wording. Each participant agreed or disagreed to these 14 statements. The statements were rated on a 7-point Likert scale with anchors from 0 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The score on the ATIS scale was calculated as mean of the 14 item scores (negative items reversed). Higher scores indicated a more positive attitude. Overall the questionnaire showed a good internal consistency of α = .83.

In order to keep this explorative study focussed, we simplified it by describing (a) just girls and (b) only two different kinds of disability. Hence, we used only vignettes regarding physical disability and behavioural disorders in girls. We created, however, each vignette twice: one presenting an Austrian girl (Hannah) and one introducing a Syrian refugee girl (Hanifa). In addition to the four mentioned vignettes, we created one more describing a refugee girl (Hanifa) without disabilities. Therefore, we had five different vignettes: (1) Austrian girl identified with a physical disability (APD); (2) Austrian girl identified with behavioural disorders (ABD); (3) refugee girl without disabilities (R); (4) refugee girl identified with a physical disability (RPD); and (5) refugee girl identified with behavioural disorders (RBD). The disability type was specified in one sentence. In the case of the girl with a physical disability, it was stated that: ‘She has a physical disability and uses a wheelchair’. The vignette representing behavioural disorders was described as: ‘She has behavioural problems: she is fidgety, restless and has difficulties focusing; she does not follow instruction’. The description of the Austrian and the refugee girl only differed in two sentences which referred to the fact that the girl is a refugee and that she is not yet able to speak or understand the language of instruction (German). The following description of the refugee girl with a physical disability provides an idea of the vignettes:

Hanifa is nine years old. She was born in Syria and moved to Austria two weeks ago. She does not speak nor does she understand German. She will be entering the third grade in a primary school in your neighbourhood. Hanifa has a physical disability and uses a wheelchair.

Socio-demographic background variables

Additionally, we collected information on the respondents’ socio-demographic background (age and gender) and socio-cultural background (educational level and the number of books at home).

Procedure

The research team and undergraduate as well as graduate students of Pedagogy collected the data. The students received training in a research method seminar and were instructed to gather data from the general public by asking people in their environment (colleagues at work, parents and friends) and people in public spaces (parks, on the street, etc.). Each student distributed 25 paper and pencil questionnaires in a sample stratified by age (with age ranging in five groups—as in five vignettes—from 16 to 87 years) and gender. Within each of five age groups, two respondents had to be women and three respondents had to be men, or vice-versa. Each respondent received a set of statements that referred to one of the five vignettes—APD (n = 276), ABD (n = 279), R (n = 274), RPD (n = 276), and RBD (n = 272).

Results

Descriptive statistics

summarises the sample description, whereby the individual characteristics of the five sub-groups (depending on the vignette the respondent’s questionnaire referred to) are displayed. As already mentioned, the sample of the five sub-groups did not differ significantly in the distribution of gender, age and educational level.

Differences in attitudes towards inclusion

In order to answer Research Question 1, an ANOVA was carried out. The five vignettes were used as the factor levels (APD, ABD, R, RPD, RBD) and the ATIS-score (the mean sum score of the 14 ATIS-items) was the dependent variable. The ANOVA revealed an overall statistically significant difference in the attitudes towards inclusion depending on the vignettes, Brown-Forsythe F (4, 1324) = 25.13, p = .000. Post-hoc comparisons, using the Games-Howell post-hoc procedure, were conducted to determine which of the five vignettes differed significantly from each other. The results of the post-hoc analysis are displayed in .

Table 2. Post hoc results for attitudes towards inclusion by vignette.

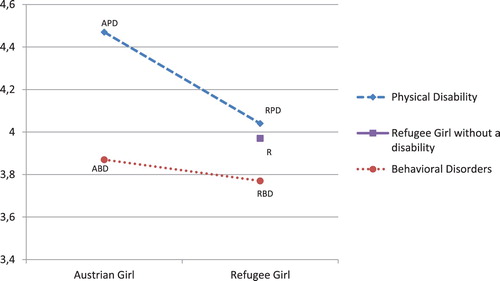

Attitudes towards the inclusion of the Austrian girl with a physical disability (APD: M = 4.47, SD = .766) were significantly more positive than the attitudes towards the other four vignettes—ABD (M = 3.87, SD = .068), R (M = 3.97, SD = .877), RPD (M = 4.04, SD = .956), and RBD (M = 3.77, SD = .990). In addition, the attitudes towards the inclusion of RPD were significantly more positive than the attitudes towards the inclusion of RBD (see ). Hence, within one nationality (Austrian or Syrian), the attitudes towards girls with a physical disability were significantly more positive than towards girls of the same nationality with behavioural disorders. Within the group of Syrian refugee girls, the attitudes towards the refugee girl with a physical disability and towards the refugee girl without any disability did not differ from each other. These results can be seen in .

shows the mean scores of the ATIS-items for all vignettes. It can clearly be seen that the attitudes towards APD (upper-left corner) are the most positive. As already shown in the post-hoc tests, the attitudes towards the APD vignette are significantly more positive than towards the other four vignettes. There are, however, no significant differences in the attitudes towards RPD (right-upper value), ABD (left-lower corner) and R (right-middle value). Meaning, that the attitudes towards the refugee girl with and without a physical disability and the Austrian girl with behavioural disorders do not significantly differ from each other and therefore the inclusion of these girls (R, RPD, ABD) is perceived to be equally challenging. Here, challenging means not only that the girl is perceived to negatively influence the class, but it also means that the class negatively affects her and a special school would be a better option. There was, however, one further significant difference displayed in the post-hoc tests and also visible in . A difference between the attitudes towards RPD (right-upper value) and RBD (right-lower value) was detected.

To summarise, the attitudes towards APD were the most positive, and therefore the inclusion into mainstream primary schools of a girl described by this vignette was perceived to be the least challenging. Furthermore, the inclusion of RPD was perceived to be less challenging than the inclusion of RBD. Surprisingly, the girl described by being ‘merely’ a refugee (without any disabilities or disorders) was perceived to be equally challenging to include as RPD, RBD and ABD.

Predicting attitudes towards inclusion

In order to examine which variables predicted the attitudes towards the inclusion of girls with and without disabilities (ATIS score), we conducted a hierarchical regression analysis. To analyse this research question with only one regression analysis, the vignette describing the refugee girl without disabilities was excluded. Hence, only four vignettes entered the analysis (APD, RPD, ABD, RBD). The predictor variables were added blockwise to the model.

All predictors concerning the respondents were entered in the model. As respondents’ variables, we entered the respondents’ gender (0 = male; 1 = female), their highest educational levels (1 = compulsory education, 2 = apprenticeship/vocational training, 3 = higher education entrance qualification, 4 = university or equivalent), the number of books at home as index for cultural capital (1 = up to 10, 2 = 11–15, 3 = 26–50, 4 = 51–100, 5 = 101–200, 6 = more than 200), and age. This model was significant and explained 6.4% of the variance, F (4, 1085) = 19.68, p < .000. Second, the predictors regarding the vignette were entered in a further step. The predictors regarding the vignette were dummy coded: disability type (0 = physical disability; 1 = behavioural disorder) and nationality/refugee status (0 = Austrian; 1 = Syrian refugee). The second model was also significant. Hence, the inclusion of the predictors regarding the vignette added further explanatory strength. This second model explained 14.2% of the variance, F (6, 1083) = 29.96, p < .000. shows the coefficients of both regression models as well as the R2 value and R2 change.

Table 3. Summary of hierarchical regression analysis for variables predicting ATIS-scores (N = 1090).

As seen in , all predictors apart from age were highly significant in Model 2. The variable respondents’ age lost its significant predictive value in the second model, when nationality/refugee status and disability type described in the vignette were added. However, the other variables—gender, educational level, number of books (cultural capital) and the vignette descriptions (nationality/refugee status and disability type)—were significant predictors of the attitudes towards inclusion. Women had a more positive attitude towards inclusion than men. Furthermore, people with higher educational levels and more books in their households also held a more positive attitude towards inclusion than people with lower educational levels and fewer books. In regard to the vignettes, results of the ANOVA could be replicated and refined; the regression analysis showed that the attitudes towards the inclusion of Austrian girls were more positive than towards the inclusion of refugee girls. In addition the attitudes were more positive towards the inclusion of girls with a physical disability than towards girls with behavioural disorders.

Discussion

In this paper we described aspects of intersectionality, a situation where one vulnerable group (refugee girls with disabilities) faces attitudinal barriers in the general public due to the belonging to multiple disadvantaged groups. The study showed that the characteristics of refugee status and type of disability were independently linked to more negative attitudes towards the inclusion of the described girls into mainstream primary schools. Both of the mentioned characteristics seem to influence the attitudes towards inclusion (i.e. both added predictive value). Therefore, it is justified to assume that refugee girls with disabilities experience intersectional discrimination. Their discriminatory experiences are aggravated due to the intersection of the refugee status and disability (Makkonen Citation2002). The risk for refugee girls with disabilities to experience intersectional discrimination lies within the stereotypes regarding girls, refugees and children with disabilities (Coleman, Brunell, and Haugen Citation2015; Rousso Citation2003).

According to previous research (Avramidis and Norwich Citation2002; De Boer, Pijl, and Minnaert Citation2010, Citation2011, Citation2012; Staniland Citation2010), it was expected that the type of disability impacted attitudes. This was true within the group of Austrian girls as well as within the group of refugee girls. In general, the inclusion of girls with a physical disability—independently of the nationality/refugee status (Austrian vs. Syrian refugee)—was perceived to be less challenging than of girls with behavioural disorders. Furthermore, the inclusion of a refugee girl without disabilities, a refugee girl with a physical disability and an Austrian girl with behavioural disorders were all perceived to be equally challenging. This result is important because the attitudes towards children with behavioural disorders are mainly negative and refugee girls with(out) physical disabilities are then perceived in a similarly negative manner.

Avramidis and Norwich (Citation2002) found in their meta-analysis that the reason for the most positive attitudes towards students with physical disability lies in the assumption that these children are the easiest ones to manage in the mainstream classroom. In contrast, the inclusion of children with behavioural disorders is seen as causing more concern than the inclusion of children with other disabilities (De Boer, Pijl, and Minnaert Citation2010). This is because children with behavioural disorders are perceived as negatively impacting other children in terms of disturbing the class and slowing other children down (Avramidis, Bayliss, and Burden Citation2000; De Boer, Pijl, and Minnaert Citation2011). Another reason is that the schools are perceived as not having enough resources (e.g. personnel resources, teaching materials etc.) and the teachers do not feel prepared to cope with students with behavioural disorders (Bešić et al. Citation2016).

Similar arguments are found in studies about L2 learners/migrant students (Youngs and Youngs Citation1999; Gitlin et al. Citation2003; Reeves Citation2006). These research results, then, might also explain why the attitudes of the general public concerning the inclusion of an Austrian girl with a physical disability were more positive than towards the inclusion of a refugee girl without any disabilities. Here we assume that the language barrier (not speaking or understanding German as described in the vignette) was perceived as a bigger challenge for including a child in a primary school than having a physical disability because L2 learners are perceived as negatively impacting the class (i.e. more work for teachers, need for explanations and special attention). This result, however, needs to be taken with care because refugee status and language abilities are linked and it is hard to disentangle the effects of these factors.

The attitudes presented in this study ‘[might reflect the perception] that inclusion should be accessible only to those students who can make it rather than adapting the space to guarantee success for all’ (Cioè-Peña Citation2017, 9). These results provide support for the claim that the respondents evaluate the inclusion of Austrian and refugee girls with disabilities differently due to their refugee status/language proficiency. This underlines the need for an intersectional perspective in inclusive education and for considering how belonging to multiple subordinated groups might influence the perception of children in educational settings and moreover their school experience. Therefore, an understanding of the particular situation of the individual refugee child with(out) disabilities in question is necessary, because refugees have different experiences (Elder Citation2015). In this regard Crock, Ernst, and McCallum (Citation2013, 756) argue for ‘serious research into the incidence of disability, and the nature of disabilities suffered by [refugees]’, otherwise ‘it is not possible to make categorical statements about the barriers presented’ to this group.

The final takeaway from the results, consistent with earlier findings, is that respondents’ characteristics—gender, educational level and cultural capital (De Boer, Pijl, and Minnaert Citation2011)—together with students’ characteristics—nationality/refugee status and disability type (Avramidis and Norwich Citation2002)—influenced the attitudes towards inclusion of the described girls.

Limitations of the study and recommendations for future research

The present study could only scratch the surface of the complex topic of attitudes towards refugee girls with(out) disabilities. Due to the research method, we were only able to examine public’s attitudes towards inclusion and not the reasons underlying them. Further research investigating the reasons underlying these attitudes is strongly warranted. Another limitation is the use of vignettes that only describe girls. As there might be differences in the attitudes depending on student’s gender, general public’s attitudes towards the inclusion of (refugee) boys with(out) disabilities should be investigated by using the same vignettes with boys’ names and comparing the results with the girls’ vignettes. Other limitations are related to the type of disability or the nationality of the children. Future studies could address a wider range of disabilities and different nationalities. Furthermore, the people directly involved in inclusive education (i.e. teachers, peers, parents) should be examined as well. By revealing their attitudes, one might also derive information concerning their needs for resources, training and knowledge. It is also crucial to better understand what refugee children with(out) disabilities need in inclusive education, from their perspective, to be successfully included in the educational environment. Qualitative and participatory approaches might be used to investigate this topic in more detail.

Finally, the present study did not manage to separate language issues from the refugee status. Since the vignette combined the two variables (refugee status and limited language proficiency), no clear statement can be made concerning which of them caused certain attitudes. By introducing vignettes that differ in these variables, future research can shed light on this topic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Edvina Bešić is a junior researcher at the Inclusive Education Unit, Institute of Educational Sciences at the University of Graz, Austria. Her research areas are inclusive education of marginalised students, evaluation research, participatory research with children, and intercultural education.

Lisa Paleczek is a junior researcher at the Catholic University College for Education Graz, Austria. Her research focuses on inclusion of children with special educational needs in the school system as well as reading and language development in L1 and L2 learners at elementary school.

Peter Rossmann is a senior researcher at the Inclusive Education Unit, Institute of Educational Sciences at the University of Graz, Austria. His research focuses on typical and atypical development in childhood and adolescence, in particular relating to the causation, detection, prevention, and treatment of behavioural disorders in children and adolescents; and pedagogical-psychological diagnostics.

Mathias Krammer is a junior researcher at the Inclusive Education Unit, Institute of Educational Sciences at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests are inclusive education, inclusive teaching practices, response to intervention, student monitoring.

Barbara Gasteiger-Klicpera is a senior researcher and Dean of the Faculty of Regional, Environmental and Educational Sciences at the University of Graz, Austria. Her main areas of interest are the inclusive education of students with special educational needs, social and emotional disorders in children, development and prevention of reading and spelling disabilities, development and prevention of behavioural difficulties.

References

- Ajzen, Icek, and Martin Fishbein. 1973. “Attitudinal and Normative Variables as Predictors of Specific Behaviors.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 27 (1): 41–57.

- Arms, Emily, Jill Bickett, and Victoria Graf. 2008. “Gender Bias and Imbalance: Girls in US Special Education Programmes.” Gender and Education 20 (4): 349–359.

- Avramidis, Elias, Phil Bayliss, and Robert Burden. 2000. “A Survey Into Mainstream Teachers’ Attitudes Towards the Inclusion of Children with Special Educational Needs in the Ordinary School in one Local Education Authority.” Educational Psychology 20 (2): 191–211.

- Avramidis, Elias, and Brahm Norwich. 2002. “Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Integration / Inclusion: A Review of the Literature.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 17 (2): 129–147.

- Balboni, Guilia, and Luigi Pedrabissi. 2000. “Attitudes of Italian Teachers and Parents Toward School Inclusion of Students with Mental Retardation: The Role of Experience.” Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities 35 (2): 148–159.

- Bauer, Werner. 2008. Zuwanderung nach Österreich [Immigration to Austria]. Wien: ÖGPP.

- Bešić, Edvina, Lisa Paleczek, Mathias Krammer, and Barbara Gasteiger-Klicpera. 2016. “Inclusive Practices at the Teacher and Class Level: The Experts’ View.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 31 (3): 1–17.

- BMB. 2016. Flüchtlingskinder und – jugendliche an österreichischen Schule [Refugee Children and Youth in Austrian Schools]. https://www.bmb.gv.at/ministerium/rs/2016_15_beilage.pdf?61edvi.

- BMI. 2017a. Asylum Statistics. http://www.bmi.gv.at/301/Statistiken/start.aspx.

- BMI. 2017b. Nationalratswahl [Parliamentarian Elections]. http://www.bmi.gv.at/412/Nationalratswahlen/Nationalratswahl_2017/start.aspx.

- Bridges, Sarah, and Simona Mateut. 2014. “Should they Stay or Should they Go? Attitudes Towards Immigration in Europe.” Scottish Journal of Political Economy 61 (4): 397–429.

- Bruneforth, Michael, Lorenz Lassnigg, Stefan Vogtenhuber, Claudia Schreiner, and Simone Breit, eds. 2016. Nationaler Bildungsbericht Österreich 2015, Band 1: Das Schulsystem im Spiegel von Daten und Indikatoren [National Education Report Austria]. Graz: Leykam.

- Burge, Philip, Héléne Quellette-Kuntz, Nancy Hutchinson, and Hugh Box. 2008. “A Quarter Century of Inclusive Education for Children with Intellectual Disabilities in Ontario: Public Perceptions.” Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy (87): 1–22.

- Byrnes, Deborah A., Gary Kiger, and M. Lee Manning. 1997. “Teachers’ Attitudes About Language Diversity.” Teaching and Teacher Education 13 (6): 637–644.

- Cioè-Peña, María. 2017. “The Intersectional gap: How Bilingual Students in the United States are Excluded from Inclusion.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 21 (9): 906–919.

- Coleman, Jill M., Amy B. Brunell, and Ingrid M. Haugen. 2015. “Multiple Forms of Prejudice: How Gender and Disability Stereotypes Influence Judgments of Disabled Women and men.” Current Psychology 34 (1): 177–189.

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989 (1): 139–167.

- Crenshaw, Kimberle. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299.

- Crock, Mary, Christine Ernst, and Ron McCallum. 2013. “Where Disability and Displacement Intersect: Asylum Seekers and Refugees with Disabilities.” International Journal of International Law 24 (4): 735–764.

- De Boer, Anke, Sip J. Pijl, and Alexander Minnaert. 2010. “Attitudes of Parents Towards Inclusive Education: A Review of the Literature.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 25 (2): 165–181.

- De Boer, Anke, Sip J. Pijl, and Alexander Minnaert. 2011. “Regular Primary Schoolteachers’ Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education: A Review of the Literature.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 15 (3): 331–353.

- De Boer, Anke, Sip J. Pijl, and Alexander Minnaert. 2012. “Students’ Attitudes Towards Peers with Disabilities: A Review of the Literature.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 59 (4): 379–392.

- Elder, Brent. 2015. “Stories from the Margins: Refugees with Disabilities Rebuilding Lives.” Societies Without Borders 10 (1): 1–27.

- European Social Survey. 2016. Attitudes Towards Immigration and their Antecedents: Topline Results from Round 7 of the European Social Survey. London: European Social Survey ERIC.

- Gerhards, Jürgen, Silke Hans, and Jürgen Schnupp. 2016. “German Public Opinion on Admitting Refugees.” DIW Economic Bulletin 6 (21): 243–249.

- Gilmore, Linda A., Jennifer Campbell, and Monica Cuskelly. 2003. “Development Expectations, Personality Stereotypes, and Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education: Community and Teacher Views of Down Syndrome.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 50 (1): 65–76.

- Gitlin, Andrew, Edward Buendía, Kristin Crosland, and Fode Doumbia. 2003. “The Production of Margin and Center: Welcoming-Unwelcoming of Immigrant Students.” American Educational Research Journal 40 (1): 91–122.

- The Guardian. 2017. Austria Rejects Far-Right Candidate Norbert Hofer in Presidential Election. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/dec/04/far-right-party-concedes-defeat-in-austrian-presidential-election.

- Halilovich, Hariz. 2013. “Bosnian Austrians: Accidental Migrants in Trans-Local and Cyber Spaces.” Journal of Refugee Studies 26 (4): 524–540.

- Hastings, Richard P., and Suzanna Oakford. 2003. “Student Teachers’ Attitudes Towards the Inclusion of Children with Special Needs.” Educational Psychology 23 (1): 87–94.

- Heckmann, Friedrich. 2008. Education and Migration: Strategies for Integrating Migrant Children in European Schools and Societies: Lessons From Research for Policy-Makers. Brussels: European Commission.

- HelpAge International and Handicap International. 2014. Hidden Victims of the Syrian Crisis: Disabled, Injured and Older Refugees. London: HelpAge International.

- Herzog-Punzenberger, Barbara. 2003. Die „2.Generation“ an zweiter Stelle? Soziale Mobilität und ethnische Segmentation in Österreich [The “Second Generation” in second place? Social Mobility and Ethnic Segmentation in Austria]. https://www.tirol.gv.at/fileadmin/themen/gesellschaft-soziales/integration/downloads/Leitbild-neu-Stand_Jaenner_2009/AK1-Bildung/2.Generation_an_2.Stelle_Bestandaufnahme-_Herzog_03.PDF.

- Kalyva, Efrosini, Maria Georgiadi, and Vlastaris Tsakiris. 2007. “Attitudes of Greek Parents of Primary School Children Without Special Educational Needs to Inclusion.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 22 (3): 295–305.

- Kunovich, Robert M. 2004. “Social Structural Position and Prejudice: An Exploration of Cross-National Differences in Regression Slopes.” Social Science Research 33 (1): 20–44.

- Lindsay, Sally, Elaine Cagliostro, Mikhaela Albarico, Neda Mortaji, and Dilakshan Srikantha. 2017. “Gender Matters in the Transition to Employment for Young Adults with Physical Disabilities.” Disability and Rehabilitation. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2017.1390613

- Makkonen, Timo. 2002. Multiple, Compound and Intersectional Discrimination: Bringing the Experiences of the Most Marginalized to the Fore. Turku: Åbo Akademi University: Institute for Human Rights.

- Mand, Johannes. 2007. “Social Position of Special Needs Pupils in the Classroom: A Comparison Between German Special Schools for Pupils with Learning Difficulties and Integrated Primary School Classes.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 22 (1): 7–14.

- McBrien, Lynn J. 2005. “Educational Needs and Barriers for Refugee Students in the United States: A Review of the Literature.” Review of Educational Research 75 (3): 329–364.

- Mittler, Peter. 2006. Working Towards Inclusive Education: Social Contexts. London: David Fulton.

- Nowicki, Elizabeth A., and Robert Sandieson. 2002. “A Meta-Analysis of School-Age Children’s Attitudes Towards Persons with Physical or Intellectual Disabilities.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 49 (3): 243–265.

- OHCHR. 2017. Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Opens Eighteenth Session in Geneva. http://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=21969&LangID=E.

- O’Rourke, Kevin H., and Richard Sinnott. 2006. “The Determinants of Individual Attitudes Towards Immigration.” European Journal of Political Economy 22 (4): 838–861.

- Pisani, Maria, and Shaun Grech. 2015. “Disability and Forced Migration: Critical Intersectionalities.” Disability and the Global South 2 (1): 421–441.

- Reeves, Jenelle R. 2006. “Secondary Teacher Attitudes Toward Including English-Language Learners in Mainstream Classrooms.” The Journal of Educational Research 99 (3): 131–142.

- Rousso, Harylin. 2003. “Education for All: a Gender and Disability Perspective.” Paper commissioned for the EFA global monitoring report 2003/4, The leap to equality.

- Rousso, Harilyn, and Michael L. Wehmeyer, eds. 2001. Double Jeopardy: Addressing Gender Equity in Special Education. New York: SUNY Press.

- Rydgren, Jens. 2017. “Radical Right-Wing Parties in Europe What’s Populism got to do with it?” Journal of Language and Politics 16 (4): 485–496.

- Scheibelhofer, Paul. 2017. “‘It Won’t Work Without Ugly Pictures’: Images of Othered Masculinities and the Legitimisation of Restrictive Refugee-Politics in Austria.” NORMA 12 (2): 96–111.

- Schwab, Susanne, Markus Gebhardt, Elfriede M. Ederer-Fick, and Barbara Gasteiger Klicpera. 2012. “An Examination of Public Opinion in Austria Towards Inclusion. Development of the ‘Attitudes Towards Inclusion Scale’ – ATIS.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 27 (3): 355–371.

- Scior, Katrina. 2011. “Public Awareness, Attitudes and Beliefs Regarding Intellectual Disability: A Systematic Review.” Research in Developmental Disabilities 32 (6): 2164–2182.

- Semyonov, Moshe, Rebeca Raijman, and Anastasia Gorodzeisky. 2008. “Foreigners’ Impact on European Societies.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 49 (1): 5–29.

- Shaw, Linda R., Fong Chan, and Brian T. McMahon. 2011. “Intersectionality and Disability Harassment: The Interactive Effects of Disability, Race, Age, and Gender.” Rehabilitation Counselling Bulletin 55 (2): 82–91.

- Smith-Khan, Laura, Mary Crock, Ben Saul, and Ron McCallum. 2014. “To ‘Promote, Protect and Ensure’: Overcoming Obstacles to Identifying Disability in Forced Migration.” Journal of Refugee Studies 28 (1): 38–68.

- Staniland, Luke. 2010. Public Perceptions of Disabled People: Evidence from the British Social Attitudes Survey 2009. London: Office for Disability Issues.

- Statistik Austria. 2014. “Bevölkerungsstand und Struktur- Volkszählungen, Registerzählung, Abgestimmte Erwerbsstatistik” [Population and Structure Censuses, Registry Censuses, Coordinated Employment Statistics]. https://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/menschen_und_gesellschaft/bevoelkerung/index.html.

- Statistik Austria. 2016. “Migration und Integration” [Migration and Integration]. https://www.integrationsfonds.at/fileadmin/content/migrationintegration-2016.pdf.

- Strabac, Zan, Toril Aalberg, and Marko Valenta. 2014. “Attitudes Towards Muslim Immigrants: Evidence from Survey Experiments Across Four Countries.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (1): 100–118.

- Taylor, Sandra, and Ravinder K. Sidhu. 2012. “Supporting Refugee Students in Schools: What Constitutes Inclusive Education?” International Journal of Inclusive Education 16 (1): 39–56.

- Transatlantic Trends. 2014. “Transatlantic Trends. Key Findings 2014.” Washington, DC.

- UNHCR. 2010. Convention and Protocol: Relating to the Status of Refugees. Geneva: UNHCR.

- UNHCR. 2011. ““Stimmungslage der österreichischen Bevölkerung in Bezug auf Asylsuchende: Eine quantitative Untersuchung durchgeführt von Karmasin Motivforschung” [General Attitudes of the Austrian Population Towards Asylum Seekers: A Quantitative Study Carried out by Karmasin Motivforschung].” Paper presented at the meeting of the Ombudsman Board, Vienna.

- UNHCR. 2015. Flucht und Asyl in Österreich - die häufigsten Fragen und Antworten [Refuge and Asylum in Austria – The Most Frequent Questions and Answers]. 4th ed.Wien: UNHCR.

- UNHCR. 2016. “Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2015.” Geneva. http://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/576408cd7/unhcr-global-trends-2015.html.

- UNICEF. 2013. The State of the World’s Children 2013. Executive Summary: Children with Disabilities. New York: UNICEF.

- Walker, Anne, Jill D. Shafer, and Michelle Liams. 2004. ““Not in my Classroom”: Teacher Attitudes Towards English Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom.” Journal of Research and Practice 2 (1): 130–160.

- WHO. 2011. World Report on Disability. Geneva: WHO. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789240685215_eng.pdf.

- Yazbeck, M., K. McVilly, and T. R. Parmenter. 2004. “Attitudes Toward People with Intellectual Disabilities: An Australian Perspective.” Journal of Disability Policy Studies 15 (2): 97–111.

- Youngs, George A., Jr., and Cheryl S. Youngs. 1999. “Mainstream Teachers’ Perceptions of the Advantages and Disadvantages of Teaching ESL Students.” Minne TESOL/WITESOL 16 (1): 15–29.

- Zick, Andreas, Beate Küpper, and Hinna Wolf. 2009. “European Conditions. Findings of a Study on Group-Focused Enmity in Europe.” Accessed April 24, 2017. http://www.amadeu-antonio-stiftung.de/w/files/pdfs/gfepressrelease_english.pdf.

- Zimbardo, Philip G., and Michael R. Leippe. 1991. The Psychology of Attitude Change and Social Influence. McGraw-Hill series in social psychology. New York: McGraw-Hill.