ABSTRACT

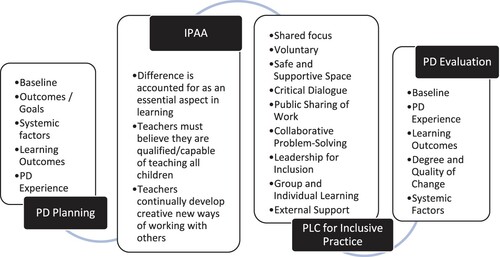

While inclusion has generally been accepted as orthodoxy, a knowledge – practice gap remains which indicates a need to focus on inclusive pedagogy. This paper explores how teachers in the Republic of Ireland primary school were supported to develop inclusive pedagogy to meet the needs of learners with special educational needs (SEN). It is underpinned by a conceptual framework which combines an inclusive pedagogical approach and key principles of effective professional development (PD) arising from the literature, which informed the development of a professional learning community (PLC) for inclusive practice in a primary school. The impact of the PD on teachers’ professional practice was explored using an evidence-based evaluation framework. Analysis of interview and observation data evidenced that engagement with inclusive pedagogy in a PLC, underpinned by critical dialogue and public sharing of work, positively impacted teacher attitudes, beliefs, efficacy and inclusive practice. This research offers a model of support for enacting inclusive pedagogy.

Introduction

This study explores how teachers in a primary school, in the Republic of Ireland, were supported to enact inclusive pedagogy. While it is acknowledged that the concept of inclusive education has moved beyond solely concerning persons with special educational needs (SEN) to extend to all persons at risk of marginalisation or exclusion in society, the inclusion of learners with SEN is the focus of this paper. Legislation advocating inclusion in schools is now common across the developed world, however the implementation of such continues to be met with myriad barriers. In the Irish context, the diversity of learners has dramatically increased in mainstream classrooms as a result of rapid policy and legislative reform over the past two decades (McConkey et al. Citation2016). The Education Act and the Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs Act (EPSEN) (Government of Ireland Citation1998; Citation2004) marked pivotal points in the progression of inclusive education, providing the legislative framework for policy development (Griffin and Shevlin Citation2011). However, full implementation of the EPSEN act has not yet been realised due to economic factors, which has negatively impacted policy development to support inclusion at school level (Rose et al. Citation2015). In addition to the challenge of varying school policies on inclusion, many teachers feel they lack the knowledge, skills, and understanding to create inclusive learning environments for learners with SEN (Rose et al. Citation2015; Travers et al. Citation2010). This lacuna can largely be attributed to the paucity of opportunities to develop teacher professional learning for inclusive practice across the continuum of teacher education (O’ Gorman and & Drudy Citation2010).

A further challenge to inclusion has emerged from the explicit policy focus (Department of Education and Skills (DES) Citation2011; Citation2017) on raising literacy and numeracy scores in international rankings. This policy focus excludes learners with SEN from norm-referenced standardised testing in literacy and numeracy and offers no direction regarding the development of inclusive assessment methods (King Citation2016). The prioritisation of achievement in supranational indicators mirrors global reform movements that arguably marginalise learners with SEN even further (McLaughlin and Dyson Citation2014). The preoccupation with standardised assessments, league tables, and competition, reinforces school structures which are underpinned by ‘bell-curve thinking’ and notions of fixed ability (Florian Citation2014). This system contributes to the legitimisation of ability grouping and the provision of additional support, which serves to reinforce marginalisation of learners with learning difficulties (McGillicuddy and Devine Citation2018; Spratt and Florian Citation2015). Teachers in the Irish context have shown to accept the principle of inclusion in a general sense, however hesitancy regarding the practical implementation of inclusion is palpable (Shevlin, Winter, and Flynn Citation2013). More than ever, teachers and schools need to be supported to challenge hegemonic assumptions regarding ability, and to develop a sense of responsibility for including all learners (Ainscow Citation2014). The focus of this paper is therefore to address the research gap relating to how teachers can be supported to enact inclusive pedagogy to meet the needs of all learners in the classroom in a way that avoids stigmatisation. Whether inclusive pedagogy is specialist or not warrants exploration in this regard.

Specialist or inclusive pedagogy?

The concept of what is special about special education is widely debated. Norwich and Lewis (Citation2007) acknowledge the complexity of this debate but contend that there is insufficient evidence to support specialist pedagogy for categories of SEN. However, they note that specialist knowledge relating to certain SEN groupings is valuable to inform pedagogical decisions. Others regard the separation of knowledge and pedagogy as potentially detrimental and assert that scientific knowledge about particular types of SEN is important in meeting the needs of all learners (Mintz and Wyse Citation2015). They argue for a concept of special pedagogy which refers to specialist knowledge of diagnostic categories and knowledge of the learner’s individual needs. In contrast, Norwich and Lewis proffer that in supporting learners with SEN, teachers draw on continua of strategies which reflect the adaptations of common teaching methodologies. Teaching at various points on the continua may look different but not qualitatively different to warrant specialist pedagogies. For example, some learners may need high levels of mastery learning or more bottom-up phonological approaches to reading but these approaches are not pedagogically disparate from teaching that encompasses less of these approaches (Norwich and Lewis Citation2007). This stance is supported by other researchers in the field who believe that all children can learn from the same pedagogical approaches, although adaptation and differentiation are key to meeting the diverse needs of all (Davis and Florian Citation2004; Rix and Sheehy Citation2014; Vaughn, Linan-Thompson, and Hickman Citation2003). Teachers often adapt strategies when working with different groups of children but once a learner is identified or diagnosed as having an SEN, they can feel inadequately prepared to meet the needs of such learners (Florian Citation2014). Individualised interventions, based on a response to a particular impairment or specific difficulty, can compound the problem of difference by marking the learner as different. Conversely, inclusive pedagogy involves the use of specialist knowledge to inform teaching, approaches to group work, and to attend to individual differences during whole-class teaching in ways that avoid stigmatisation (Florian Citation2014).

The inclusive pedagogical in action approach framework

The development of inclusive pedagogy emanated from a study of the craft knowledge of teachers who effectively supported the learning of all children in their classrooms, which included diverse learners, while avoiding stigmatisation of difference (Florian and Black-Hawkins Citation2011). It was further developed through a project which embedded inclusive pedagogy in a postgraduate initial teacher education (ITE) programme in Scotland. In this context, the Inclusive Pedagogical Approach in Action (IPAA) framework emerged as a support mechanism for teachers to develop responses to individual differences in ways that do not marginalise any learner (Spratt & Florian, Citation2015). It is suggested as a tool for researchers in the field of inclusive education and for use in teacher education and PD contexts to support students and teachers in examining their own inclusive pedagogy (Florian Citation2014; Florian and Spratt Citation2013). Heretofore, published research on how teachers enact inclusive pedagogy and the way in which the IPAA can support this enactment, has been predominantly focused on teachers who have engaged in a postgraduate ITE programme in Scotland (Florian and Spratt Citation2013; Spratt and Florian Citation2015). This study expands the research on how the IPAA can support practising teachers, in collaboration with an external facilitator, to enact inclusive pedagogy in the classroom.

The IPAA framework identifies three key assumptions that teachers must hold in order to enact inclusive pedagogy while also acknowledging the challenges of meeting the needs of all learners. Firstly, teachers must believe in the concept of transformability which refers to the belief that a child’s capacity to learn is not static nor pre-determined but can be transformed by the actions undertaken by the teacher in developing teaching and learning (Hart & Drummond, Citation2014). However, the dominance of ‘bell-curve’ thinking presents a challenge to rejecting deterministic beliefs about ability (Florian Citation2014). The second assumption of the IPAA refers to fostering teachers’ beliefs in their ability to teach students with SEN. Research studies have highlighted the need to address teacher efficacy for inclusive education as it can negatively impact teacher behaviour towards, and acceptance of, students with SEN (Dupoux, Wolman, and Estrada Citation2005; Forlin, Sharma, and Loreman Citation2014). Associated with the second assumption is the view that difficulties in learning are not within the learner but are problems for the teacher to solve. In this context, teachers must be prepared to commit to supporting the learning of all (Florian Citation2014). The third assumption relates to teachers being willing to work with others which aligns with the literature that deems teacher collaboration as central to implementing inclusive education (Ainscow Citation2014; Friend et al. Citation2010; Nevin, Thousand, and Villa Citation2009). Yet meaningful professional collaboration requires systemic and school support which can often prove limited (Kershner Citation2014; Travers et al. Citation2010).

Research on the classroom practices of newly qualified teachers (NQTs) who had engaged with the IPAA in a postgraduate ITE context indicated that the NQTs demonstrated responses learning difficulties in ways which considered every learner, rather than responses targeted at individuals (Spratt and Florian Citation2015). A variety of approaches were evident in these classrooms which included collaborative group work, formative assessment, and choice. Such teaching approaches have been identified as effective teaching strategies both for inclusion and in general and are necessary to respond to individual needs within the whole class context (Jordan, Schwartz, and McGhie-Richmond Citation2009). However, the challenge of inclusive pedagogy is to implement teaching approaches in a way that avoids the exclusion of any learner, as was demonstrated by the NQTs who had engaged with the IPAA (Spratt and Florian Citation2015).

There has been some criticism of inclusive pedagogy arising from a study of teachers’ practices for including learners with Autism in mainstream classrooms (Lindsay et al. Citation2014). This qualitative research study examined the strategies used by 13 mainstream class teachers in meeting the needs of learners with Autism in their classes. While teachers adhered to inclusive pedagogy, they also reported that they had to use specific strategies to manage behaviour that could be considered exclusionary, as they targeted individual students. The study concludes that while the IPAA is a valuable framework to support the implementation of inclusive pedagogy, it could benefit from some amendments to reflect the complexity of including learners with significant behavioural needs or the complex needs of some learners with Autism (Lindsay et al. Citation2014). Similarly, research on special education teachers (SETs) who had recently completed a Postgraduate Diploma in SEN in the Republic of Ireland highlighted the challenge of meeting individual targets for learners with SEN, as outlined in individual education plans, in mainstream classrooms (King, Ní Bhroin, and Prunty Citation2018). Based on the findings, it is recommended that PD should support teacher collaboration for whole school approaches to incorporating individual learning targets into planning and teaching (King et al., Citation2018).

Arguably the IPAA does not consider the levels of complexities of difference that may occur between learners, which may present varying levels of challenge to addressing individual learner differences in whole class contexts. However, it can support teachers to draw on a range of effective methodologies to meet the needs of all learners. In particular, it focuses on democratic teaching practices, such as differentiation through choice, which advocates providing learners with choice over how they engage in and display their learning (Florian Citation2014). Furthermore, the three key assumptions outlined in the IPAA are fundamental to positive dispositions towards including all learners in classrooms where individuals are valued. Yet these are complex concepts for teachers to consider, in particular when they have not met these concepts in their ITE programmes. Therefore, teachers need to be effectively supported in developing their understanding of inclusive pedagogy in order to challenge hegemonic assumptions about difference and to develop inclusive practice. In this study, such support was conceptualised in terms of evidenced-based approaches to transforming teacher learning for inclusive pedagogy.

Supporting teacher professional learning for inclusive pedagogy

There is some disagreement regarding which is impacted by change first: beliefs, practices or student learning. Guskey (Citation2002a) maintains that changes can occur in teachers’ beliefs and attitudes after they see evidence of improved student outcomes while others dismiss that change occurs in a linear progression and highlight the reciprocal relationship between changes in beliefs, practices and student learning (King Citation2014; Opfer and Pedder Citation2011; Rouse Citation2008). Opfer and Pedder (Citation2011) maintain that change can occur at any point. It is reciprocal, with a change in one element depending on change in another. However, for teacher learning to transpire, there must be a change in all three areas; beliefs, practices and student learning. Similarly, Rouse (Citation2008) describes the reciprocal triangular relationship between knowing, believing and doing. If teachers have positive beliefs about inclusion and support to implement new approaches, then they are likely to develop new knowledge about inclusive practice. Alternatively, a teacher who believes in inclusion but does not feel capable of implementing inclusive practice could undertake PD to develop his or her knowledge for inclusive practices, which may enhance teacher efficacy for inclusive practice. Teachers will differ in levels of knowledge, beliefs, and practices relating to inclusive practice but all three do not have to be in place to ensure teacher change, development of two elements is likely to influence development of the third (Rouse Citation2008). The challenge for teacher education is to support teachers’ understanding of the complexity of change and implementation of change (King Citation2014) and to employ effective pedagogies for teacher learning that develop the knowledge, beliefs and practices to support inclusive pedagogy (Florian Citation2008).

A meta-review of 24 physical education PD studies published between 2005 and 2015 verified three distinct pedagogies of effective teacher learning; critical dialogue, public sharing of work, and engagement in communities of learners (Parker, Patton, and O’Sullivan Citation2016). These pedagogies are delineated according to Shulman’s (Citation2005) signature pedagogy dimensions: surface, deep, and implicit structures. At the surface structure of critical dialogue there is a focus on reflection and inquiry through deep conversations that challenge teaching and evidence of student learning (Parker, Patton, and O’Sullivan Citation2016). At the deep structure of this pedagogy teachers construct meaning through collaborative discourse relating to teaching and learning. The implicit structure of critical dialogue aligns with the discursive practice approach which has shown to be an effective method for challenging and transforming deterministic beliefs about difference (Peters and Reid Citation2009). It is a form of resistance, exercised by disability scholars, that targets hegemonic theories of disability and impairment in order to reframe attitudes and beliefs to lead to transformative practice. Public sharing of work relates to teachers sharing practices, beliefs, values and artefacts of work at the surface level (Parker, Patton, and O’Sullivan Citation2016). The deep structure involves teachers creating and sharing elements of their practice that can be used by others in the classroom. While it can be daunting for teachers to share their classroom practices and evidence of student learning, at an implicit level it can lead to affirmation of their work and consequently improved self-confidence (Parker, Patton, and Sinclair Citation2016) which suggests the potential for improved efficacy. The pedagogy of communities of learners aligns with the professional learning community (PLC) model of teacher learning, in that it promotes collective knowledge building around a shared concern at the surface level. The deep structure provides the supportive conditions for such while the implicit structure provides a safe space for teachers to explore and challenge practices that are routine (Parker, Patton, and O’Sullivan Citation2016). The PLC model is a form of collaborative inquiry that can manifest the pedagogies of critical dialogue, public sharing of work and working in a community of learners and has been shown to hold promise for transformative teacher learning (Kennedy Citation2014; Stoll et al. Citation2006). However, this model of professional learning remains under-utilised for developing inclusive practice (Pugach and Blanton Citation2014).

Research approach

This research study explored how a PLC, underpinned by the IPAA, can support teachers in a primary school in the Republic of Ireland, to meet the needs of learners with SEN. The research approach was a qualitative, single-site case study that incorporated multiple methods of data collection. Ten participants were recruited through purposive sampling comprising eight mainstream class teachers, the deputy principal and the school principal, both of whom were in administrative positions. Of the eight mainstream teachers, two were NQTs, while the other six teachers ranged in teaching experience from 2 to 11 years. Prior to undertaking the study, ethical approval was obtained from Dublin City University Ethics Committee.

Monthly PLC meetings were held between January and June 2016 with each session lasting approximately 90 minutes. At the outset, participants were introduced to the IPAA framework. As characteristic of effective PLCs, the participants chose a shared focus – differentiation through choice – which is a key facet of inclusive pedagogy. Each month there was engagement in public sharing of work and critical dialogue on teachers’ practice and student learning in the classroom, followed by agreement on actions for the following month. In addition, the participants completed a reflective learning log at the end of each session in order to critically reflect on any new learning and to guide the researcher for the following session. Researcher observations from the PLC meetings were recorded in a researcher reflexive journal. Four participants consented to engage in observation of practice on two occasions during the study, in order to explore inclusive pedagogical approaches in action. This involved researcher observation of two lessons in the four participants’ classrooms. An observation schedule was devised based on the IPAA and ‘Levels of Use of New Practice’ from the PD Evaluation Framework (King Citation2014). Semi-structured interviews were undertaken with all participants at the end of the study.

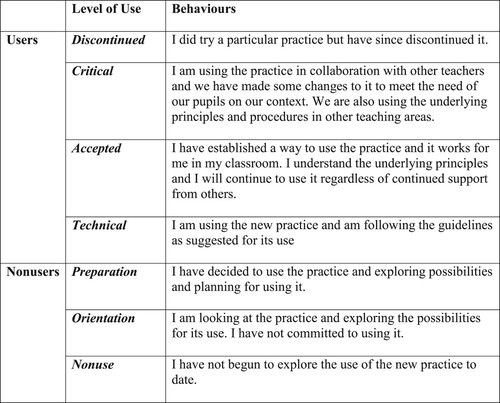

The use of the IPAA framework to support teacher learning was planned and evaluated using the evidence-based PD Evaluation Framework as PD is more likely to be effective when it is planned and evaluated (King Citation2014; Citation2016). The paucity of research on the evaluation of teacher PD prompted the development of the PD Evaluation Framework (King Citation2014). Building on previous research (Bubb and Earley Citation2010; Guskey Citation2002b; Hall and Hord Citation1987) it offers a refined evaluation tool to capture the complexities teacher professional learning. It was validated in a study which evaluated the long-term impact of a PD initiative on teachers’ professional learning in five primary schools in the Irish context (King Citation2014). The framework includes key criteria to consider when planning and evaluating professional learning (). The ‘Levels of Use of New Practice’ () is included in the framework to support the evaluation of changes in teachers’ practice and was used in the analysis of the research findings in this study.

Figure 2. Levels of use of new practice (King, Citation2014).

A six-step approach to thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) was adopted. Phase one of the coding process involved familiarisation with the data set. At the beginning of this process, the interviews were transcribed and collated with the data which had been transcribed throughout the research; observation schedules, field notes from the PLCs in the researcher reflexive journal and participant reflective logs from each PLC. Transcribed data were re-read and initial ideas were noted by the researcher. These data were imported into NVivo 11.4 along with the literature. Phase two involved the identification of interesting features or initial codes from across the data set. These codes were then collated into relevant themes in Phase three. Following this the themes were reviewed in relation to their relevance to the coded extracts which resulted in seven themes. The final round of coding involved refinement which resulted in the generation of definitions and names for each theme. The final themes from Phase five of the data analysis include; changes in teachers’ attitudes and beliefs towards inclusive practice, changes in teachers’ efficacy for inclusive practice, changes in teachers’ practice, factors that supported teacher change, and factors that hindered teacher change.

Findings

Analysis of observation and interview data evidenced that the IPAA framework was effective in supporting seven of the class teacher participants to enact an inclusive pedagogical approach at a critical level and one participant at a technical level (). Teacher professional learning relating to the three assumptions outlined in the IPAA () was discernible in the research findings.

Challenging deterministic beliefs about ability

Analysis of interviews and research field notes from the PLC meetings demonstrated that there was a shift in thinking relating to learner ability among the participants which aligns with the first assumption of the IPAA. In the second PLC meeting, there was a critical discussion about ability labelling. Emily, who was teaching a third class (8–9 years), reflected on how differentiation through choice had impacted her thinking about ability labelling. She reported that she became more aware of the negative impact of determining the level of each child and putting limits on what they can do, as opposed to giving them choice and allowing learners to determine their own level of engagement. Similarly, Rebecca, who was teaching a senior infant class (5-6 years), added that differentiation through choice improved her inclusive practice as she could differentiate for all without marking any one child as different. Rebecca elaborated on this point in the interview when she referred to the significant impact that teacher expectations can have on student learning:

… when you’re differentiating it’s your expectations deciding what they can achieve from the lesson. If you’re giving them the choice you have different options as how they are going to express themselves in the lesson. It’s really letting each child achieve. Because it’s differentiation by choice it’s including every child, every child has a chance to achieve to the best of their abilities but they’re not being pigeon holed as someone who is different. (Rebecca, Interview)

I kind of just think to a certain extent that anything is possible now … I do think if you plan the lesson correctly and use the right methods and everything that everyone can achieve something in the class. (Niamh, Interview)

It surprised me how productive they were when they were given that free choice and they were proud of their work … I found their strengths by letting them pick how they wanted to do things and it showed me their strengths and it showed me how to work with them. (Kieran, Interview)

Teacher efficacy for inclusive practice

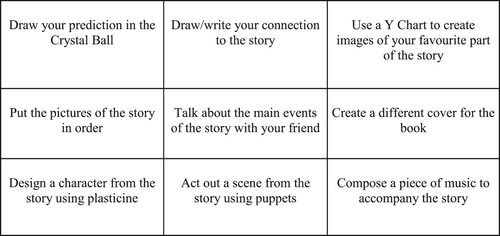

The second assumption of the IPAA framework refers to teachers believing that they are capable of teaching all children. The class teacher participants (n = 5) displayed increased efficacy for inclusive practice arising from successful outcomes in their classes which encouraged sustainability of new practices throughout the duration of the study (King Citation2014; Citation2016). Emily discussed the impact of differentiation through choice on one particular learner whom she had concerns about:

He is a reluctant learner but definitely, by giving him the choice he really flourished and he came up with some really creative stuff and it was really just amazing. (Emily, Interview 5)

Figure 3. Choice Board Example: Responding to a Text (Brennan, Citation2019).

There was also evidence of improved efficacy amongst other participants. In responding to whether engagement with the IPAA had impacted on her confidence in her capability to develop inclusive practice Niamh reflected:

Definitely, especially the two children which I originally came here for at first. They’re prouder of their work because to them they’re choosing what’s easiest or more interesting to them and they’re completing that first and by the time they get to something that they think might be difficult they’re on that roll and suddenly they’re doing it without even being aware. (Niamh, Interview)

Teacher collaboration

The development of inclusive schools depends on school leaders’ commitment to inclusion and the development of a culture of respect for difference through ongoing collaboration (Ainscow and Sandill Citation2010). The principal and deputy principal demonstrated this commitment to supporting teacher learning for inclusive pedagogy from the outset. They showed enthusiasm for collaborative PD and dialogue which bolstered the development of teacher professional learning for inclusive pedagogy. The principal commented: ‘I am very committed to the idea of teachers learning from each other. I think much of our most worthwhile learning comes from the dialogue we have with other teachers’ (Principal, Interview). This kind of support from school leaders is paramount to the success of teacher professional learning, as is emphasised in the literature time and again (Day et al. Citation2009; Harris and Jones Citation2010; Stoll et al. Citation2006). In addition, the principal demonstrated a commitment to inclusion which is fundamental to the development of inclusive schools (Mac Ruairc Citation2013). The participants highly valued the support from school leadership which empowered them to take agentic approaches to their practice and to collaboration, identified as important for developing teacher professional learning (King Citation2014; Citation2016).

The teachers in the study successfully enacted the third concept of the IPAA regarding working with others in creative ways to develop inclusive practice. The participants engaged in various forms of collaboration including collaborative problem-solving, shared planning, lesson study and observation, and the development of inclusive practice through co-teaching. Two of the class teachers were engaged in co-teaching with SETs during the study, something which was being piloted in the school. These teachers capitalised on this opportunity to support the development of inclusive pedagogy. They reported that this collaboration proved very effective in implementing new inclusive practices in the classroom and had some impact on the dissemination of new practice, as noted by Niall:

I think through the team teaching it spread because I know two of the learning support staff were in Niamh’s class and they were also coming down to my class and they could see we were trying similar things and they might say ‘oh Niamh tried it this way and it might work better that way’ so it is kind of filtering through. (Niall, Interview)

Challenges

Research on inclusive pedagogy has documented practices which are informative and valuable in understanding how teachers can enact inclusive pedagogy in their classrooms (Florian and Black-Hawkins Citation2011; Florian and Spratt Citation2013; Spratt and Florian Citation2015). However, there is a lack of research into how teachers can enact pedagogy that marks no one as different in situations where learners experience significant challenges. While participants in this study were successful in creating environments that provided learning opportunities for all learners without marking any individual as different most of the time, six participants reported that differentiation through choice did not work for all learners. There were some situations where the participants struggled to avoid approaches which marked some learners with SEN as different, despite engaging in critical dialogue and sharing of practice. For example, Kieran expressed disappointment regarding one child who had difficulty with choice:

perhaps part of that was a failing on my part for not teaching him how to make a choice and stick with it but it fed into other areas of school life as well. I think it’s a language disorder. (Kieran, Interview)

Another example of difficulty with differentiation through choice was observed during a lesson in Rebecca’s classroom, where a child with Autism struggled to stay on task and demonstrated frustration. Rebecca had taken an inclusive pedagogical approach by developing a whole class lesson, which accounted for the diverse learning needs of all learners, in addition to avoiding ability grouping. She reflected on how she had to give one learner a lot of individual support in order for him to engage in the task, which meant that she could not provide support to the other learners, demonstrating a conflict with the IPAA. However, this additional support enabled the learner to engage in the lesson.

Arguably the learners in the participants’ classes who needed ‘something different’ than their peers required pre-teaching before they were expected to engage in choice. Explicit instruction and modelled practice with the whole class in preparation for the lessons may have prevented the learners from encountering the level of difficulties that were experienced. Again, this finding demonstrates the importance of collaboration between the class teacher and the SET to focus on individual targets (King et al. Citation2018) in preparation for and/or in tandem with differentiation through choice. The teachers in these cases had to modify their teaching approaches to meet the needs of the learners who had difficulty with choice, demonstrating the notion of continua of teaching approaches that may be adapted to different degrees of intensity depending on learner needs (Norwich and Lewis Citation2007). However, considering the research findings, it could be argued that IPAA did not support the teachers to include some learners with SEN without marking them as different. This finding is consistent with research carried out by Lindsay et al. (Citation2014) which identified elements of the inclusive pedagogical approach that proved impracticable in certain cases. Lindsay et al. (Citation2014) suggest that inclusive pedagogy could prove difficult to enact for some learners with Autism, who may need individualised strategies to address behavioural issues, echoing arguments that learners with Autism may need different approaches (Jordan Citation2005). Contrary to the findings of Lindsay et al. (Citation2014) there was evidence of the IPAA supporting teachers to effectively include learners with Autism and other learners with SEN. In relation to one learner with Autism, Niall reported that ‘socially, getting to choose which group he was part of was of great benefit to him’ (Niall, Interview). While Diane expressed concern regarding including a learner with a Moderate GLD (Down Syndrome) engaging in choice, she successfully supported him to make choices by using pictures that were available to all the class. This reflects an inclusive pedagogical approach of responding to learner difficulties in ways that consider all children, rather than using strategies aimed at individual learners (Spratt and Florian Citation2015).

It is proffered that a minor adjustment to the IPAA would be beneficial, which could acknowledge that there may be certain cases where individualised strategies may be necessary to meet learner difficulties, as arguably no one strategy or approach will work with all learners in all contexts. However, teaching strategies which highlight difference serve to compound the marginalisation of learners who already experience isolation (Florian and Spratt Citation2013). Therefore, it is critical that any adjustment to the IPAA would not be a carte blanche for teachers to use exclusionary approaches in meeting the needs of learners with SEN, for example, deciding at the outset of a lesson that a learner with SEN will need additional support to engage in an activity or depending on overt differentiation such as differentiated expectations for learners. This demonstrates the importance of teachers developing a repertoire of pedagogies that can be drawn upon to meet different learning needs, rather than one set of pedagogies for all learners (Florian Citation2014; O’Gorman and & Drudy Citation2010). Furthermore, the third principle of the IPAA, working creatively with and through others, behoves class teachers and SETs to collaborate in ways that support the inclusion of learners with SEN without highlighting the difference. Such collaboration can support learners’ individual targets in a whole class setting (King et al., Citation2018).

Teaching dilemmas in inclusive practice cannot be simply solved by providing the same type of support or approaches, as differences in learners cannot be characterised as homogenous (Lawson, Boyask, and Waite Citation2013). In such cases, critical dialogue and public sharing of work are valuable teacher education pedagogies that can disrupt hegemonic beliefs about difference and disability. These pedagogies were critical to supporting teachers to enact inclusive pedagogy in this study. Critical dialogue and public sharing of work in the PLC diminished teacher isolation and subsequently affirmed participants’ practice and improved their self-confidence which corroborates research on the benefits of collaborative social learning (Ainscow and Sandill Citation2010; Cochran-Smith and Lytle Citation1999, Citation2009; Stoll et al. Citation2006) and research which demonstrates that this type of learning affirms teachers’ practice (Parker, Patton, and O’Sullivan Citation2016). The external expertise in this study facilitated these pedagogies and was also highly valued by the participants to support their engagement with the IPAA. While these pedagogies could be facilitated internally within schools, there is a danger that a collegial community will only serve to embed existing practice if it fails to challenge current teaching methods and lacks focus regarding meeting learners’ needs (Timperley Citation2008). Furthermore, models of collaborative professional inquiry will not transform practice if they are contrived efforts to promote external interests rather than meaningful teacher and student-driven collaboration (Kennedy Citation2014). Thus, external support may prove necessary in supporting teachers to engage in pedagogies such as critical dialogue and public sharing of work, which as evidenced in this research, can scaffold collaborative problem solving around teaching dilemmas.

Conclusion

Teacher learning for inclusive practice across the teacher education continuum is paramount to the development of inclusive schools. Yet the literature has demonstrated that initial teacher education does not sufficiently prepare teachers to effectively include all learners (Forlin Citation2010; O’Donnell Citation2012) and PD opportunities in inclusive education are insufficient (Rose et al. Citation2015; Shevlin, Kenny, and Loxley Citation2008; Travers et al. Citation2010). It is not suggested that the IPAA is a menu of options nor that the enactment of inclusive practice occurs in a typical way, it will depend on the unique context and the individual learners in the class context (Spratt & Florian, 2013). Hence, considering that each context, as well as each learner, is unique, it is unlikely that any one framework will cover all aspects and situations of practice in developing inclusive pedagogy. However, this study has shown that the IPAA can effectively support newly qualified and experienced teachers to enact inclusive pedagogy, with positive outcomes for teachers and learners This was a single-site case study and therefore the findings cannot be generalised to the population. Notwithstanding, the research findings demonstrate that the IPAA can position teachers to meet the needs of all learners when they are supported with engagement in critical dialogue and public sharing of work in a PLC. Furthermore, collaboration with SETs in this context could ensure an awareness of individual needs and may support class teachers in devising inclusive choices for learners.

Teachers work within a system in which difference can be viewed as a deficit and therefore as advocated by Lawson et al. (Citation2013), policy needs to support teachers to acknowledge, problematise, question, and rethink difference in a way that becomes embedded in practice at classroom level. As demonstrated in this study, external expertise can provide facilitation of effective pedagogies for teacher learning that challenge teacher beliefs. However, university-school partnerships could support teachers who have engaged in postgraduate studies in inclusive education to facilitate collaborative inquiry for inclusive pedagogy in their own contexts. The conceptual framework underpinning this study () presents a model to guide the development of such teacher professional learning. Furthermore, school leaders must encourage open dialogue within schools that explores difference and diversity and how it can be addressed in a way that is inclusive for all (Mac Ruairc Citation2013). In order to build an equitable society, educational endeavours must work towards eliminating deficit conceptualisations of disability. In this context, teachers need to be prepared to commit to supporting the learning of all learners without marking any one learner as different. In order to foster that commitment, teachers must be supported to develop an understanding of inclusive pedagogy for the benefit of all learners and how to enact it in the classroom. This research offers a model of how critical dialogue and public sharing of work in a PLC can support teachers to contribute to the goal of equality for all learners.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Aoife Brennan

Aoife Brennan is an assistant professor in the School of Inclusive and Special Education. She previously worked as a mainstream and learning support/resource primary teacher. Teaching across seven undergraduate and postgraduate teacher education programmes up to and including doctoral level, Aoife’s areas of teaching interest include inclusive pedagogy and differentiation, diversity and special and inclusive education, teacher professional learning, collaborative practice and leadership for inclusive schools. She is the Chair of the Professional Certificate/Diploma in Special and Inclusive Education.

Fiona King

Fiona King is an assistant professor in the School of Inclusive and Special Education, Dublin City University (DCU). Fiona began her career as a primary teacher and spent 25 years teaching in a variety of contexts including mainstream primary schools both in Ireland and the U.S. and a special school. In January 2014 she joined St. Patrick’s College of teacher education and now currently works in DCU, Institute of Education where she specialises in the following areas: teachers’ professional development and learning. leadership and teacher leadership, collaboration and collaborative practices, change, and inclusive practice. Fiona is Programme Chair for the Professional Doctorate in Education (EdD) in the Institute of Education.

Joe Travers

Dr Joseph Travers is an associate professor and the first Head of School of Inclusive and Special Education in Dublin City University (DCU) Institute of Education, the first education faculty in an Irish university. Previous to this he was Director of Special Education (2008–2016) in St. Patrick’s College, Drumcondra joining the College in 1998. He is a former primary school teacher (mainstream, special class, learning support/resource teacher for Travellers). He has published in the areas of policy and practice in special education/learning support for mathematics, inclusion, leadership and early intervention. He teaches across a range of teacher education programmes from initial to postgraduate Diploma, Masters and Doctoral level.

References

- Ainscow, M. 2014. “From Special Education to Effective Schools for all: Widening the Agenda.” In The Sage Handbook of Special Education, edited by L. Florian, 172–185. London: Sage.

- Ainscow, M., and A. Sandill. 2010. “Developing Inclusive Education Systems: The Role of Organisational Cultures and Leadership.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 14 (4): 401–416. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13603110802504903

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi: https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brennan, A. 2019. “Differentiation Through Choice as an Approach to Inclusive Practice.” REACH Journal of Special Needs Education in Ireland 32 (1): 11–20.

- Bubb, S, and S Earley. 2010. Helping Staff Develop in Schools. London: Sage.

- Cochran-Smith, M., and S. L. Lytle. 1999. “Relationships of Knowledge and Practice: Teacher Learning in Communities.” Review of Research in Education 24: 249–305.

- Cochran-Smith, M., and S. L. Lytle. 2009. Inquiry as Stance: Practitioner Research for the Next Generation. New York: Columbia University: Teachers College Press.

- Davis, P., and L. Florian. 2004. “Searching the Literature on Teaching Strategies and Approaches for Pupils with Special Educational Needs: Knowledge Production and Synthesis.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 4 (3): 142–147. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2004.00029.x

- Day, C., P. Sammons, D. Hopkins, A. Harris, K. Leithwood, G. Qing, E. Brown, E. Ahtaridou, and A. Kington. 2009. The Impact of School Leadership on Pupil Outcomes. Final report. Retrieved on 6th January 2019 from http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/11329/1/DCSF-RR108.pdf.

- Department of Education and Skills (DES). 2011. Literacy and Numeracy for Learning for Life: The National Strategy to Improve Literacy and Numeracy among Children and Young People 2011–2012. Dublin: DES.

- Department of Education and Skills (DES). 2017. National Strategy: Literacy and Numeracy for Learning for Life: 2011–2020 Interim Review: 2011–2016, New Targets: 2017–2020. Dublin: DES.

- Dupoux, E., C. Wolman, and E. Estrada. 2005. “Teachers’ Attitudes Toward Integration of Students with Disabilities in Haiti and the United States.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 52 (1): 43–58. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10349120500071894

- Florian, L. 2008. “Inclusion: Special or Inclusive Education: Future Trends.” British Journal of Special Education 35 (4): 202–208. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8578.2008.00402.x

- Florian, L. 2014. “Reimagining Special Education: Why new Approaches are Needed.” In The Sage Handbook of Special Education, edited by L. Florian, 9–22. London: Sage.

- Florian, L., and K. Black-Hawkins. 2011. “Exploring Inclusive Pedagogy.” British Educational Research Journal 37 (5): 813–828. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2010.501096

- Florian, L., and H. Linklater. 2010. “Preparing Teachers for Inclusive Education: Using Inclusive Pedagogy to Enhance Teaching and Learning for All.” Cambridge Journal of Education 40 (4): 369–386. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2010.526588

- Florian, L., and J. Spratt. 2013. “Enacting Inclusion: A Framework for Interrogating Inclusive Practice.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 28 (2): 119–135. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2013.778111

- Forlin, C. 2010. Teacher Education for Inclusion: Changing Paradigms and Innovative Approaches. Oxon: Routledge.

- Forlin, C., U. Sharma, and T. Loreman. 2014. “Predictors of Improved Teaching Efficacy Following Basic Training for Inclusion in Hong Kong.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 18 (7): 718–730. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2013.819941

- Friend, M., L. Cook, D. Hurley-Chamberlain, and C. Shamberger. 2010. “Co-teaching: An Illustration of the Complexity of Collaboration in Special Education.” Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation 20 (1): 9–27. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10474410903535380

- Government of Ireland. 1998. Education Act. Dublin: Stationery Office.

- Government of Ireland. 2004. Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs Act [EPSEN]. Dublin: Stationery Office.

- Griffin, S., and M. Shevlin. 2011. Responding to Special Needs Education: An Irish Perspective. Dublin: Gill Education.

- Guskey, T. R. 2002a. “Professional Development and Teacher Change.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 8 (3): 381–391. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/135406002100000512

- Guskey, T.R. 2002b. Does It Make a Difference? Evaluating Professional Development. Educational Leadership, 59 (6), 45–51.

- Hall, G. E., and S. M. Hord. 1987. Change in Schools: Facilitating the Process. New York: Suny Press.

- Harris, A., and M. Jones. 2010. “Professional Learning Communities and System Improvement.” Improving Schools 13 (2): 172–181. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1365480210376487

- Hart, S, and M Drummond. 2014. Learning Without Limits: Constructing a Pedagogy Free from Determinist Beliefs About Ability. In L. Florian (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Special Education (2nd edition, pp. 500–515). London: SAGE

- Jordan, R. 2005. “Autistic Spectrum Disorders.” In Special Teaching for Special Children? Pedagogies for Inclusion, edited by A. Lewis and B. Norwich, 110–122. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Jordan, A., E. Schwartz, and D. McGhie-Richmond. 2009. “Preparing Teachers for Inclusive Classrooms.” Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (4): 535–542. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.010

- Kennedy, A. 2014. “Understanding Continuing Professional Development: The Need for Theory to Impact on Policy and Practice.” Professional Development in Education 40 (5): 688–697. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2014.955122

- Kershner, R. (2014). “What do Teachers Need to Know About Meeting Special Educational Needs?” In The Sage Handbook of Special Education, edited by L. Florian, 841–858. London: Sage.

- King, F. 2014. “Evaluating the Impact of Teacher Professional Development: An Evidence-Based Framework.” Professional Development in Education 40 (1): 89–111. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2013.823099

- King, F. 2016. “Teacher Professional Development to Support Teacher Professional Learning: Systemic Factors from Irish Case Studies.” Teacher Development 20 (4): 574–594. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2016.1161661

- King, F., Ó Ní Bhroin, and A. Prunty. 2018. “Professional Learning and the Individual Education Plan Process: Implications for Teacher Educators.” Professional Development in Education 44 (5): 607–621. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2017.1398180

- Lawson, H., R. Boyask, and S. Waite. 2013. “Construction of Difference and Diversity Within Policy and Practice in England.” Cambridge Journal of Education 43 (1): 107–122. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2012.749216

- Lindsay, S., M. Proulx, H. Scott, and N. Thomson. 2014. “Exploring Teachers’ Strategies for Including Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream Classrooms.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 18 (2): 101–122. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2012.758320

- Mac Ruairc, G. 2013. “Including who? Deconstructing the Discourse.” In Leadership for Inclusive Education: Values, Vision and Voices, edited by G. Mac Ruairc, E. Ottesen, and R. Precey, 9–18. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- McConkey, R., R. Kelly, S. Craig, and M. Shevlin. 2016. “A Decade of Change in Mainstream Education for Children with Intellectual Disabilities in the Republic of Ireland.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 31 (1): 96–110. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2015.1087151

- McGillicuddy, D., and D. Devine. 2018. ““Turned off” or “Ready to fly” – Ability Grouping as an Act of Symbolic Violence in Primary School.” Teaching and Teacher Education 70: 88–99. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.11.008

- McLaughlin, M., and A. Dyson. 2014. “Changing Perspectives of Special Education in the Evolving Context of Standards-Based Reforms in the US and England.” In The Sage Handbook of Special Education, edited by L. Florian, 889–914. London: Sage.

- Mintz, J., and D. Wyse. 2015. “Inclusive Pedagogy and Knowledge in Special Education: Addressing the Tension.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 19 (11): 1161–1171. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1044203

- Nevin, A. I., J. S. Thousand, and R. A. Villa. 2009. “Collaborative Teaching for Teacher Educators – What Does the Research say?” Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (4): 569–574. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.009

- Norwich, B., and A. Lewis. 2007. “How Specialized is Teaching Children with Disabilities and Difficulties?” Journal of Curriculum Studies 39 (2): 127–150. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00220270601161667

- O’Donnell, M. 2012. “Teachers’ Efficacy Beliefs for Including Pupils with Special Educational Needs.” In Special and Inclusive Education: A Research Perspective, edited by T. Day and J. Travers, 69–84. Dublin: Peter Lang.

- O’Gorman, E., and S. & Drudy. 2010. “Addressing the Professional Development Needs of Teachers Working in the Area of Special Education/Inclusion in Mainstream Schools in Ireland.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 10 (1): 157–167. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01161.x

- Opfer, V. D., and D. Pedder. 2011. “Conceptualizing Teacher Professional Learning.” Review of Educational Research 81 (3): 376–407. doi: https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311413609

- Parker, M., K. Patton, and M. O’Sullivan. 2016. “Signature Pedagogies in Support of Teachers’ Professional Learning.” Irish Educational Studies 35 (2): 1–17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2016.1141700

- Parker, M., K. Patton, and C. Sinclair. 2016. “‘I Took This Picture Because … ’: Teachers’ Depictions and Descriptions of Change.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 21 (3): 328–346. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17408989.2015.1017452

- Peters, S., and D. K. Reid. 2009. “Resistance and Discursive Practice: Promoting Advocacy in Teacher Undergraduate and Graduate Programmes.” Teaching and Teacher Education 25 (4): 551–558. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.02.006

- Pugach, M., and L. Blanton. 2014. “Inquiry and Community: Uncommon Opportunities to Enrich Professional Development for Inclusion.” In The Sage Handbook of Special Education, edited by L. Florian, 873–888. London: Sage.

- Rix, J., and K. Sheehy. 2014. “Nothing Special: The Everyday Pedagogy of Teaching.” In The Sage Handbook of Special Education, edited by L. Florian, 459–474. London: Sage.

- Rose, R., M. Shevlin, E. Winter, and P. O’Raw. 2015. “Project IRIS – Inclusive Research in Irish Schools.” In A Longitudinal Study of the Experiences of and Outcomes for Pupils with Special Educational Needs (SEN) in Irish Schools. Trim: National Council for Special Education (NCSE).

- Rouse, M. 2008. “Developing Inclusive Practice: A Role for Teachers and Teacher Education.” Education in the North 16 (1): 6–13.

- Shevlin, M., M. Kenny, and A. Loxley. 2008. “A Time of Transition: Exploring Special Educational Provision in the Republic of Ireland.” Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 8 (3): 141–152. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2008.00116.x

- Shevlin, M., E. Winter, and P. Flynn. 2013. “Developing Inclusive Practice: Teacher Perceptions of Opportunities and Constraints in the Republic of Ireland.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 17 (10): 1119–1133. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2012.742143

- Shulman, L. S. 2005. “Signature Pedagogies in the Professions.” Daedalus 134 (3): 52–59. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/0011526054622015

- Spratt, J., and L. Florian. 2015. “Inclusive Pedagogy: From Learning to Action. Supporting Each Individual in the Context of ‘Everybody’.” Teaching and Teacher Education 49: 89–96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.03.006

- Stoll, L., R. Bolam, A. McMahon, M. Wallace, and S. Thomas. 2006. “Professional Learning Communities: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Educational Change 7 (4): 221–258. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8

- Timperley, H. 2008. Teacher Professional Learning and Development. Educational Practices Series-18. UNESCO International Bureau of Education. Retrieved on January 6, 2019 from http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Publications/Educational_Practices/EdPractices_18.pdf.

- Travers, J., T. Balfe, C. Butler, T. Day, M. Dupont, R. McDaid, M. O’Donnell, and A. Prunty. 2010. Addressing the Challenges and Barriers to Inclusion in Irish Schools: Report to Research and Development Committee of the Department of Education and Skills. Drumcondra: St. Patrick’s College.

- Vaughn, S., S. Linan-Thompson, and P. Hickman. 2003. “Response to Instruction as a Means of Identifying Students with Reading/Learning Disabilities.” Exceptional Children 69 (4): 391–409. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/001440290306900401