ABSTRACT

School leaders have an important role in supporting implementation of inclusive education practices in schools. Therefore, it is necessary to understand how school leaders’ attitudes towards inclusive education are formed. We used the Attitudes Toward Inclusive Education Scale that was developed to measure different facets of attitudes towards inclusive education for all students. The instrument was completed by 301 school leaders in Estonia. Three factors describing attitudes in facets of inclusive education practices, vision, and supports were distinguished. Structural Equation Modelling revealed that school leaders’ practices towards implementing inclusive education approaches are driven more strongly by their vision than the support available to them, although both aspects have a significant effect on their attitudes towards these practices. However, participation in in-service courses focusing on inclusive education and working as a school leader in a special school had negative association with school leaders’ attitudes towards inclusive education practices.

Introduction

Drawing on the idea of social justice, inclusive education has become an important aim of education worldwide (Arcidiacono and Baucal Citation2020; Odom Citation2000; Soukakou Citation2012; Vlachou and Fyssa Citation2016). According to the UNESCO Salamanca Statement and the 1994 Framework for Action, the inclusion of disabled children should be the norm (UNESCO Citation1994). This means that all children have to be enrolled in mainstream schools unless there are compelling reasons for doing otherwise. The Framework for Action adopted in the Salamanca conference states that inclusion and participation are essential for human dignity and could be considered as an exercise of human rights. It means that all children should learn together in mainstream schools that must recognise and respond to the diverse individual needs of their students.

This study focuses on inclusive education in Estonia. Like many Eastern European countries, Estonia has had a long history of special education. This history has influenced the acceptance of inclusive education principles and their implementation. The principles of inclusive education were established at the legislative level in 2010. In 2019 Estonia had 516 schools providing basic education of which 39 were special schools. Moreover, schools have possibilities to compose special classes to support students with special educational needs (SEN students). The term inclusive education has not been defined in Estonian legislation and the guidelines for inclusive education give references to European documents. Following, inclusive education is understood as SEN students having the right to study in their schools of residence with their peers (Basic Schools and Upper Secondary Schools Act Citation2010, Citation2019). It has also been understood as a learning approach that is organised in a way that at least 80% of learning is carried out jointly for all students in mainstream classes (Räis, Kallaste, and Sandre Citation2016). A significantly broader definition has been provided by Nelis and Pedaste (Citation2020) based on a systematic literature review, and this is guiding Estonian research and development work on inclusive education. According to this, inclusive education is ‘an educational approach that takes into account human rights and provides all children with access to high quality education in a learning environment where children feel social integration and belongingness in their wider social network despite their special needs; it is achieved by the meaningful participation of all children and personalised support in the development of each child’s full potential’ (162). These understandings resemble the idea of inclusive education for all (see Kielblock Citation2018; Miles and Singal Citation2010) or as it has been termed earlier by Peters (Citation2004, 47) ‘Education for All-Together’.

However, since the term has not been clearly defined in the legislative frameworks, there are also variety of understandings and interpretations to it (Kivirand et al. Citation2020) and data is not systematically collected on the state level according to this definition. There is no recent data about the ratio of students studying in mainstream or special classes in mainstream schools and those studying in special schools, but over a period of five years, from 2010 to 2014, special classes in mainstream schools became much more popular – the percentage of students studying in special classes increased from 4.3 to 9.1. At the same time, the ratio of students studying in mainstream classes decreased from 81.2 to 78.5, and in special schools from 14.6 to 12.3. According to the recent Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS), teachers in Estonia feel that they do not have the necessary competence to teach students with diverse needs in the same class (OECD Citation2020). Teachers have emphasised the need for more support staff, while school leaders have reported not having enough resources to organise an inclusive learning environment (Balti Uuringute Instituut Citation2015). Häidkind and Oras (Citation2016) showed that Estonian school-teachers felt support staff (speech therapist, psychologist, social pedagogy teacher, special needs teacher) were responsible for supporting children’s development in their institution. Thus, the principle that SEN students should study in mainstream schools is legislatively accepted in Estonia, but learning is often organised in segregated classes, which might not guarantee academic and social inclusion of SEN students. Several researchers have associated the implementation of inclusive education principles to agency (see Miller et al. Citation2020 for a review). For example, it strongly depends on the agency of teachers and school leaders if they decide to form additional special classes or provide education for all students in the mainstream classes.

Agency refers to an individual’s active participation in and shaping of practices and is generally considered an important precondition for the successful functioning of a workplace and other spheres of life (Billett Citation2006). Agency is domain-specific. A professional can have more agency related to some aspects of their work (e.g. using ICT in teaching) and less related to other aspects (e.g. supporting SEN students). Biesta, Priestley, and Robinson (Citation2015) developed an ecological model of agency. According to this model, agency is a decision-making process influenced by professional’s past practices and competencies (e.g. knowledge and experiences related to supporting SEN students in an inclusive classroom), professional purposes that describe their vision and goals (e.g. if it would be good to apply inclusive education or segregate students or why inclusive education might be valuable), and the environmental characteristics that can either support or hinder the application of their competences and the achievement of their purposes (see Leijen, Pedaste, and Lepp Citation2020; Biesta, Priestley, and Robinson Citation2015). This model implies that teachers’ decision-making regarding inclusive education is influenced by all these dimensions (own competences, purposes, and environmental support). Regarding the latter, collaborative school culture and horizontal relations between peers (e.g. fellow teachers and support staff at school) seem to be strong environmental facilitators for agency development (see e.g. Juutilainen et al. Citation2018; Priestley, Biesta, and Robinson Citation2015). School leaders have a key role in establishing the vision of the school and in developing the organisational culture and managing structural and material conditions, also in the context of inclusive education (see e.g. Ricci, Scheier-Dolberg, and Perkins Citation2020; Van Mieghem et al. Citation2020).

In line with the ecological model of agency, the practical application of inclusive education might depend on several characteristics of school leaders or their schools. For example, school leaders working in a special school or those that have been working in an inclusive classroom might have more positive attitudes towards inclusive education practices based on their experience. Similarly, participation in in-service courses focusing on inclusive education should increase competence needed in forming positive attitudes (see e.g. Grogan Citation2013). Longer experience working as a school leader as well as the school leader’s age could also be predictors of positive attitudes because with time school leaders gain more experience and competence. However, attitudes could also depend on the level of school characteristics. It might be expected that a smaller number of students in a school may have a positive effect on attitudes towards the practice because it is easier to take into account the diversity of the students’ needs if the classes are not too large.

As already noted, attitudes are important in applying inclusive education both based on the ecological model of agency (Biesta, Priestley, and Robinson Citation2015) and several studies focusing on the predictors of inclusive education practices (see e.g. Avramidis and Norwich Citation2002; Bruns and Mogharberran Citation2007). Positive attitudes towards inclusive education are crucial for implementing inclusive practices (Kielblock Citation2018). They support the natural use of instructional strategies effective in mainstream classrooms and can increase the feeling of competency (Campbell, Gilmore, and Cuskelly Citation2003). Further, positive attitudes play an important role to enhance the reliance on inclusive practices and achieve positive educational outcomes (Peters Citation2004). Conversely, negative attitudes can create lower expectations for achievement and social status and support inappropriate behaviour among students with disabilities (Larrivee Citation1985; Larrivee and Horne Citation1991) or lead to reduced expectations and fewer learning opportunities for students (Idol Citation2006; Shade and Stewart Citation2001).

Several studies have also shown that school leaders’ attitudes are significantly related to the commitment of the entire school staff to implement inclusive education (Ainscow and Sandill Citation2010; Al-Mahdy and Emam Citation2017; O’Laughlin and Lindle Citation2015; Sumbera, Pazey, and Lashley Citation2014). Van Mieghem et al. (Citation2020) recommended in a meta review that attitudes of school leaders should be more often reported in the studies. Thus, it is important to understand the school leaders’ attitudes towards inclusive education and how these attitudes towards practices are formed.

School leaders’ attitudes towards inclusive education have been described in several studies. For example, the ATIES scale of teachers’ attitudes (Wilczenski Citation1995) has also been used to study attitudes of administrators towards the integration of children with physical, academic, behavioural, and social difficulties into the mainstream classrooms in the USA (see e.g. O'Rorke-Trigiani (Citation2003). The MATIES survey instrument (Mahat Citation2008) to identify teachers’ attitudes have in some cases been used to measure school leaders’ affective, cognitive, and behavioural attitudes in regard to inclusion in Hong Kong (see e.g. Yan and Sin Citation2015). The PATIE instrument has been developed specifically for measuring school leaders attitudes, (Bailey Citation2004) but focuses largely on students with disabilities, which is not the entire focus of our study. However, the framework that seems best in line with the definition of inclusive education for all and the ecological model of agency (Biesta, Priestley, and Robinson Citation2015) is the model proposed by Kielblock (Citation2018). In his study, the ATIES scale was further developed in line with the contemporary approach of inclusive education for all and validated in the contexts of Australia and Germany. The dimensions of attitudes identified by Kielblock (Citation2018) were attitudes towards practices, differentiation, support, and vision, which are in line with the theoretical framework of agency introduced above, e.g. vision is related to purpose and support is related to cultural, structural, and also material conditions of an environment.

Therefore, the first goal in our study was to test Kielblock’s instrument for measuring school leaders attitudes towards inclusive education for all. Next, we aimed to assess school leaders’ attitudes and investigate how attitudes towards inclusive education practices, differentiation, vision, and support are related to each other. We hypothesised that the availability of support (support staff) and the vision of school leaders may predict attitudes towards practices of inclusive education. Further, we expected that some of the background variables describing school leaders and their schools may be significant in predicting attitudes. Our guiding question was: How can school leaders’ attitudes towards inclusive education practices be predicted based on their vision and perceived support in applying inclusive education approaches in school and based on background variables describing school leaders and their schools?

Methods

Estonian context

According to the Basic Schools and Upper Secondary Schools Act (Citation2019) inclusive education has been listed as a principle for all schools. The decentralised education system in Estonia offers great autonomy to local authorities and school leaders to organise compulsory education in their schools, including the provision of special needs education (Basic Schools and Upper Secondary Schools Act Citation2019). Although many school leaders understand the need for inclusive education, their primary concern is the lack of available support specialists, e.g. special educators and speech therapists (Räis and Sõmer Citation2016). In the last decade, many schools have made efforts to provide three-tiered (general, enhanced, and special) support for SEN students in mainstream schools and provide study opportunities, totally or partly, in an inclusive manner. In 2019, 14.8% of students received general support, 3.6% enhanced support, and 3.1% special support. Even though there are good examples of inclusive schools, most schools are in the early stages of the process of creating an inclusive school culture and practice (Räis, Kallaste, and Sandre Citation2016).

In addition to the lack of support, specialists, advisers, and educators for inclusive education, who usually have a background in special education, point out that SEN students are not sufficiently supported in mainstream schools because of the teachers’ insufficient knowledge and skills to cope with SEN students in an inclusive classroom (see Kivirand et al. Citation2020). Over the last decade, quite a few in-service training programmes have been conducted in Estonia in the field of inclusive education practice (for most recent developments see Kivirand et al. Citation2021). Teachers’ high involvement in professional development activities related to this area was also reported in the recent TALIS report (see OECD Citation2020). However, our analysis of the course content at one of the major universities in Estonia providing teacher education shows that the core content of these courses has typically focused on didactical methods to teach SEN students rather than on strategies of inclusive pedagogy, which according to Spratt and Florian (Citation2015) should respond to learners’ diversities in ways that avoid the marginalisation of SEN students.

Design of the study

The instrument developed by Kielblock (Citation2018) was translated to Estonian by the authors of the article. It was decided not to change the structure but to revise the items of the instrument so that these are applicable for both teachers and school leaders. The data was collected online. A list of contacts of all school leaders of Estonian schools where the language of study is Estonian was composed. All school leaders were contacted using a single email address saying that, as the ratio of students with special educational needs in mainstream schools in Estonia had steadily increased in recent years, we wished to explore the views and attitudes of school leaders and teachers towards inclusive education. The school leaders were asked to participate in the study on a voluntary basis. No incentives were provided to them to participate in the study. The participants’ informed consent was sought in the first question in the questionnaire. No data about school leaders’ identity or personal information was collected. They were also informed that their identity cannot be identified during the data analysis. The respondents were not related to the researchers and most of the members of the target group did not know the researchers in person. Therefore, we considered the study to be in line with ethical aspects provided by the national guidelines for research ethics. Indeed, we understood that the possibilities to make generalisations on the level of the population of Estonian school leaders might be limited in case the sample is not representative to the population.

Sample

The population of the study consisted of 706 school leaders at Estonian schools. The sample comprised 301 school leaders (43%). Eight variables were used to describe the sample:

type of school: 277 (92%) worked in a mainstream school and 24 (8%) in a special school;

number of students in a school: most of the schools had up to 100 students (97 schools, 32.2%), approximately one-fifth were quite large with 600 or more students (64 schools, 21.3%);

gender of school leaders: 62 were men (20.6%);

experience of school leaders: most had experience working at schools (not necessarily as a school leader) that ranged over 20 years (196 school leaders, 65.1%), while only 19 (6.3%) had less than five years of experience;

age of school leaders: four respondents were under 30 years (1.3%), 22 were aged between 31 and 40 years (7.3%), 95 were aged between 41 and 50 (31.6%), 118 were aged between 51 and 60 years (39.2%), and 62 were aged above 60 years (20.6%);

experience in working in inclusive classrooms: 82.1% of school leaders had experience working in inclusive classrooms;

completion of courses in inclusive education: approximately half the school leaders had not completed any course on inclusive education (159 school leaders, 52.8%), and only seven had participated in courses for at least 40 hours (2.3%); the rest had participated in a shorter in-service training programme that focused on inclusive education (135 school leaders, 44.9%);

self-evaluation on school leaders’ knowledge on inclusive education: most school leaders evaluated their perceived knowledge in inclusive education as good (144 school leaders, 47.8%) or at least as average (101 school leaders, 33.6%), and only 54 evaluated it as very good (17.9%); two school leaders evaluated their knowledge as insufficient.

Questionnaire on attitudes towards inclusive education for all

We adapted the Kielblock’s (Citation2018) questionnaire to measure the attitudes towards inclusive education for all. This instrument consists of 38 items divided into four factors: vision, differentiation, practice, and support. The first three were present in the original ATIES scale, and support was identified by Kielblock as an additional factor. All items were measured on a seven-point Likert-type self-evaluation agreement scale, where all values of the scale were described (−3 = very strongly disagree, −2 = strongly disagree, −1 = disagree, 0 = neither disagree nor agree, 1 = agree, 2 = strongly agree, 3 = very strongly agree). The Vision factor was described using statements such as ‘Inclusion facilitates socially appropriate behaviour for all students’, the Differentiation factor using statements such as ‘I am willing to adapt the curriculum to meet the individual needs of all students with inclusive classrooms’, the Practice factor with statements such as ‘It is possible to organise classes in a way that is suitable for all children’, and the Support factor with statements such as ‘I feel there are personnel from outside school to support me to address the unique educational needs of all students’.

We found that 33 out of 38 items were appropriate to the Estonian context, by drawing upon expert discussions. Two additional items were developed to highlight the collaboration among teachers. In the expert discussions, the wording of the items was slightly modified so that the items would be appropriate for both teachers and school leaders. Thus, the final ATIES-EST questionnaire was adapted to the Estonian context and language for both target groups – teachers and school leaders – and comprised 35 items. These items were expected to describe the same four facets as they did in Kielblock (Citation2018) – practice, differentiation, vision, and support.

Analysis

The factor structure of the questionnaire to measure attitudes towards inclusive education was tested using CFA. First, the normed chi-square index was calculated. Based on Kline (Citation1998) and Ullman (Citation2001), the model was considered acceptable if the value of the index was below 3 and good if it was below 2. The model was considered acceptable if the fit indices were the following (see Bowen and Guo Citation2012): Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) ≤.05, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) ≥.95, and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) ≥.95. Weighted Root Mean Square (WRMR) was used as suggested by Yu (Citation2002) in the event where some of the items were dichotomous or categorical. We applied one difference compared to the analysis of Kielblock (Citation2018). He treated all items as continuous variables, but we used them as categorical. The value of the WRMR index should be close to 1.0.

SEM was used to answer the primary research question on the model of predicting school leaders’ attitudes towards inclusive education based on their vision and perceived support in applying inclusive education approaches at school. In this case, the same fit indices as in the case of CFA were applied to assess the model fit. Mplus Version 7.4 (Muthén and Muthén Citation2016) was used to conduct the CFA and SEM analyses. SPSS version 26.0 was applied to derive the descriptive statistics.

Results

Factor structure of the questionnaire

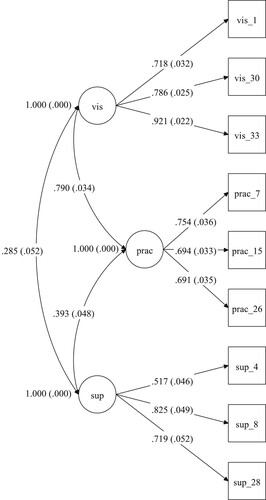

The ATIES-EST questionnaire was used to measure the school leaders’ attitudes towards inclusive education. It focused on four facets: practice, differentiation, vision, and support. First, we used all 35 items to test the factor structure. The CFA on our sample of school leaders in the case of the adapted questionnaire did not show an acceptable fit of the data with the model (χ²/df = 5.80, RMSEA = .125, CFI = .758, TLI = .740, WRMR = 2.230). Therefore, we restricted the use to the items used in the model alone, according to the model confirmed by Kielblock (Citation2018), where using the three items to describe all four factors was recommended, thus presenting a total of 12 items out of the 38 from the original questionnaire. The model constructed from these 12 items had a significantly better fit with the data (χ²/df = 5.34, RMSEA = .119, CFI = .914, TLI = .882, WRMR = 1.178). However, the model did not have an acceptable fit. Next, we followed the modification indices provided by Mplus and carefully analysed each suggestion. It appeared that all the factor loadings of items loaded in the Differentiation factor could be predicted strongly by other factors as well, such as the factor Practice. Based on these results, we decided to revise our theoretical model by dropping the Differentiation factor and testing the three-factor model, focusing only on the attitudes in the context of Practice, Vision, and Support. This revised model had a good fit with the data (see ) and was used in the following analysis. In this model, the factor loadings were all above .5. The internal reliability based on Cronbach’s alpha was .806 in the case of Vision, .731 in the case of Practice, and .665 in the case of Support. The correlation between the factor Support with the other factors was low, but between Vision and Practice was quite high.

Figure 1. Final factor model of school leaders (n = 301) attitudes towards practices (prac), vision (vis) and view of availability of support (sup) in inclusive education. Fit indices: χ²/df = 3.38, RMSEA = .089, CFI = .973, TLI = .959, WRMR = 0.789. Parameter estimates were obtained using WLSMV with THETA parametrisation, the values are standardised and significant. Numbers in rectangles are the item numbers in the questionnaire.

We compared the confirmed three-factor model with several other models to understand whether it had the best fit with the data. Some of the other models included a two-factor model, where the highly correlated facets of Vision and Practice form one factor, a second-order factor model, and a bifactor model. The comparison is presented in . The two-factor model had a worse fit to data. The second-order factor model had the same fit indices, but, in this model, the first-order factor Practice had the value of an unexplained variance below zero, and the loading of the second-order factor on this first-order latent variable was larger than 1. The bifactor model was promising because the CFI was even better than in the case of the tree-factor model, but the other indices were slightly worse. In the case of the bifactor model, the general factor had strong negative correlation with Support and moderate correlation with Practice but no statistically significant correlation with Vision. The factor loadings of Practice on two out of the three items were not significant in this model, while all the others were significant. This indicated that the highly correlated Vision and Practice in the three-factor model could be used as separate factors. In the bifactor model, two out of the three-factor loadings of Support on respective items were above 1. Therefore, in conclusion, we decided to use the three-factor model in the following analyses.

Table 1. Fit indices of the Confirmatory Factor Analysis models describing ATIES-EST test.

School leaders’ attitudes towards inclusive education

The descriptive statistics of school leaders’ attitudes towards inclusive education, based on the items used in the final three-factor model, are presented in . The results show that school leaders have a slightly positive vision towards inclusive education and beliefs in practices, but they have extremely negative attitudes in case of the availability of support. The most critical views appeared to be in the case of adequacy of resources to support them to address the unique educational needs of all students. The most positive views were on the belief that inclusion will foster understanding of differences among students, and good teachers can differentiate their practices, so they can teach all students in the class. The high variance in the answers based on the standard deviation, which is above 1 in the case of all items, is somewhat surprising.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of school leaders (n=301) attitudes towards inclusive ATIES-EST test (7-point scale, ranging from −3 to +3).

Formation of attitudes towards practices based on vision and support

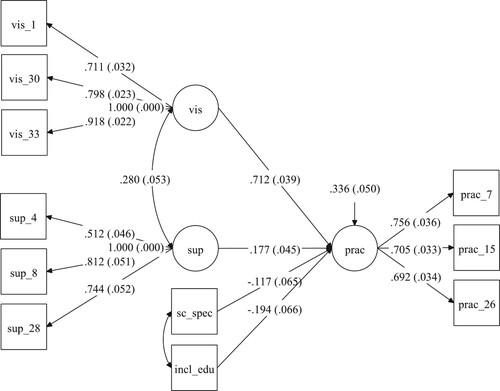

The SEM analysis showed that our hypothetical model to predict school leaders’ attitudes towards inclusive education practices based on their attitudes on vision and support and some background variables had a very good fit to the data (χ²/df = 1.50, RMSEA = .041, CFI = .978, TLI = .973, WRMR = 0.900), and it predicted 68% of the variance of the attitudes towards the practice of inclusive education. However, most of the background variables did not have a statistically significant regression on attitudes towards practice. The only statistically significant background variable, out of eight variables, was the type of school of the school leader – whether it was a mainstream school or a special school. Three more background variables showed some effect on the attitudes, although in these cases it was not statistically significant: women had a bit more positive attitudes, more experienced school leaders had slightly more negative attitudes, and surprisingly, participation in courses focusing on inclusive education had a negative effect on school leaders’ attitudes towards inclusive education practice. In the case of these three background variables, the regression coefficients were above .1.

In the next step, we decided to revise the model including only these four selected background variables. The fit indices of the revised model were slightly worse when compared to the model involving more variables, and the gender and general experience did not have a significant effect on attitudes towards practice (χ²/df = 2.22, RMSEA = .064, CFI = .969, TLI = .960, WRMR = 0.948). However, in the revised model, the participation in courses focusing on inclusive education had a statistically significant effect on the attitudes. Therefore, we simplified the model even more by using only the two significant ones as background variables. The final simplified model is shown in .

Figure 2. SEM model for predicting attitudes towards practice (prac) in inclusive education based on school leaders vision (vis), view of availability of support (sup), school type (se_spec; 1 = mainstream school, 2 = special school), and experience of participation in in-service courses focusing on inclusive education (incl_edu; 1 = not at all, 2 = slightly, 3 = a lot (at least 40 hours)). Fit indices: χ²/df = 2.50, RMSEA = .071, CFI = .973, TLI = .963, WRMR = 0.883. Parameter estimates were obtained using WLSMV with THETA parametrisation, the values are standardised and significant. The numbers in rectangles are the item numbers in the questionnaire.

The variance in the school leaders’ positive attitudes towards inclusive education practice was predicted by 66% based on their vision, adequacy of support, school type, and participation in in-service courses focusing on inclusive education. The strongest predictor was the vision of the school leaders, and the weakest was whether the school leaders worked in a mainstream or a special school. The latter was the only variable in this model that was not statistically significant, although it was statistically significant in the initial model, including all background variables. A positive vision towards inclusive education was a very strong predictor of positive attitudes towards inclusive education practice. Positive associations were also found with evaluation of the adequacy of support. However, in this case, the standardised regression coefficient was approximately four times smaller than in case of vision. Surprisingly, the school leaders working in a special school had more negative attitudes towards inclusive education practice, and the school leaders who had participated in in-service courses focusing on inclusive education had more negative attitudes towards inclusive education practice.

Discussion

We found that the factor structure found previously on teachers attitudes towards inclusive education was generally adaptable to school leaders. However, the factor of differentiation did not fit the model well. This may be explained by the fact that school leaders do not directly focus on differentiating among classroom practices, and, for them, inclusive education practice may be reflected better by a more general factor of attitudes towards inclusive education practice. Thus, the three-factor model seems to be more appropriate based on our findings.

The description of school leaders’ attitudes towards inclusive education based on the three items selected for describing each of the three factors in the final model indicated the following: on average, school leaders have slightly positive attitudes towards inclusive education vision and practice, but extremely negative attitudes towards adequacy of support, as also reported in a previous study on Estonian school leaders (Räis and Sõmer Citation2016). It shows that school leaders are generally not satisfied with support available either within their school or outside. However, it is remarkable that the variance in the results was quite high for all items. It indicates that different school leaders had significantly different attitudes towards inclusive education. Therefore, future studies should focus on distinguishing among groups of school leaders to demarcate those who are more positive from those who are very negative. An in-depth analysis of these groups may make it valuable to understand how attitudes will change and how these attitudes may have an effect on the actual practice of school leaders and their schools.

The SEM analysis in our study revealed that attitudes towards practice are predicted very strongly by the vision of the school leaders and much less by the support they have while applying an inclusive education. This is a very interesting finding that could be interpreted in line with the ecological model of agency (Biesta, Priestley, and Robinson Citation2015, Leijen, Pedaste, and Lepp Citation2020). It seems that changes in school start from creating a shared vision, as also shown by several other authors (Ricci, Scheier-Dolberg, and Perkins Citation2020; Van Mieghem et al. Citation2020). Therefore, school leaders should be supported in forming their vision and goals for education. Following the vision education for all, they might also be more willing to adapt the environment according to the vision and support the development of professional competence of teachers accordingly. Thus, vision towards inclusive education seems to be the key to positive changes towards applying inclusive education practices.

Regarding the background variables, it was found in our study that the school leaders working in special schools had more negative attitudes towards inclusive education practice than those working in mainstream schools. The reasons need to be examined further. The effect on actual practices as applied in different types of schools also needs to be examined further. As in many countries, the number of special schools has decreased in recent decades in Estonia. This may be because school leaders in special schools in Estonia feel a sense of uncertainty around the widespread use of inclusive education practices across the country. However, they might also be unsure in the quality of the education provided to the SEN students in the mainstream schools as also was indicated in the case of support staff (special educators, speech therapists, psychologists) studied by Räis and Sõmer (Citation2016) in the Estonian context.

Surprisingly, the school leaders who had participated in in-service courses focusing on inclusive education had significantly more negative attitudes towards inclusive education practice. In the Estonian context, these courses have usually been taught by educators who have a background in special education. It has been found earlier that more in-services training in special education and experiences in working with students with disabilities is related to more positive attitudes towards inclusive education (Van Reusen, Shoho, and Barker Citation2001). In describing the Estonian context, we also found that the in-service courses provided to teachers in Estonia over the last decade have largely focused on didactical methods of teaching SEN students and not on strategies of inclusive pedagogy. Thus, the studies might have not been in line with the suggestions presented by Spratt and Florian (Citation2015), who highlighted the importance of focusing on learners’ diversities in ways that avoid the marginalisation of SEN students. On the one hand, this raises a question as to whether continuing with these courses in the same way is desirable and in line with the inclusive education policy as agreed upon at the country level (Basic Schools and Upper Secondary Schools Act, Citation2010, Citation2019). A recent study conducted in the Estonian context (Kivirand et al. Citation2020) showed that advisers and educators of teachers in the area of inclusive education do not have a shared view on inclusive education and may advocate vastly different ideas. On the other hand, it may be true that school leaders who have learned about inclusive education have a more realistic view and are therefore not so positive towards applying inclusive education practices in the short term, especially because of their negative attitudes towards the adequacy of support. It may indeed be different in the case of a long-term vision. However, at least in the case of inclusive education vision, the effect of in-service courses was indeed negative and also in the case of practice, although not statistically significant. This indicates a concern regarding the currently provided in-service courses.

Conclusions

This study focused on the school leaders’ attitudes towards inclusive education practice. We confirmed that the ATIES instrument adapted to the Estonian context and language, as the ATIES-EST scale, could be used to measure school leaders’ attitudes towards inclusive education for all students. This study distinguished among three facets of attitudes related to inclusive education: attitudes towards vision, practice, and support. Further, it was found that school leaders in Estonia have slightly positive attitudes towards vision and practice of inclusive education but extremely negative attitudes towards adequacy of support. The availability and adequacy of support may be an important limitation in the process of applying inclusive education practice at school. In this study we only focused on identifying statistically significant predictors of attitudes towards inclusive education practices; however, it might be valuable to cluster schools or school leaders in the further studies to understand even better how to diversify interventions to support formation of positive attitudes towards inclusive education.

Surprisingly, the attitudes towards support did not predict attitudes towards practices as strongly as attitudes towards vision did. Therefore, it seems more important to start by framing the shared vision of school leaders towards inclusive education. Moreover, it is important that school leaders strengthen collaboration between teachers and support staff to empower teachers’ agency and to formulate shared vision and goals for inclusive education practices. We did not have data on the actual inclusive education practices in the schools to which the responding school leaders belonged. We also lacked data on the support available to them in these schools and these schools itself. Thus, the conclusions drawn here are somewhat limited. Therefore, in future studies, it would be valuable to also capture the actual practices of schools and the availability and type of support to understand how the attitudes towards practice, vision, and support predict actual practice. Further, it would be interesting to study the link between attitudes towards support and the availability and quality of the support itself and how different types of training have effect on both school leaders’ and teachers’ attitudes towards inclusive education. Another limitation of this study is that the attitudes towards practices of inclusive education and related vision factors were quite strongly correlated. This needs to be studied in the future, as well. Moreover, it would be valuable to study the attitudes of teachers and school leaders in the same school to understand how their attitudes influence each other.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Katrin Saks who contributed towards adapting the questionnaire calling for information on attitudes towards inclusive education to suit the Estonian context and language. We also thank Annika Aidla who contributed in adapting the questionnaire and collecting data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Margus Pedaste

Margus Pedaste, is a Professor of Educational Technology, his main research themes are educational technology, science education, teacher education, inquiry-based learning, technology-enhanced learning and instruction, and learning analytics.

Äli Leijen

Äli Leijen, is a Professor of Teacher Education, her main research themes are teacher education, teachers’ professional development, inclusive education, supporting students’ metacognitive processes, and, ICT for supporting teaching and learning.

Tiina Kivirand

Tiina Kivirand is an Assistant of Inclusive Education and a doctoral student of Educational Sciences. Her main research themes are inclusive education in school context and school leaders’ and teachers’ professional development related to inclusive education.

Pille Nelis

Pille Nelis is an Assistant of Educational Sciences and a doctoral student of Educational Sciences. Her main research themes are early childhood education and inclusive education in early childhood education context.

Liina Malva

Liina Malva was at the time of conducting research published in the article a Junior Research Fellow in Inclusive Education, a doctoral student of Educational Sciences and a Special Education Teacher at a primary school. Her main research themes we teachers’ knowledge, teacher education, and inclusive education.

References

- Ainscow, M., and A. Sandill. 2010. “Developing Inclusive Education Systems: The Role of Organisational Cultures and Leadership.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 14 (4): 401–416. doi:10.1080/13603110802504903.

- Al-Mahdy, Y. F. H., and M. M. Emam. 2017. “Much ado About Something’ how School Leaders Affect Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education: the Case of Oman.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 22 (11): 1154–1172. doi:10.1080/13603116.2017.1417500.

- Arcidiacono, F., and A. Baucal. 2020. “Towards Teacher Professionalization for Inclusive Education: Reflections from the Perspective of a Socio-Cultural Approach.” Eesti Haridusteaduste Ajakiri 8 (1): 26–47. doi:10.12697/eha.2020.8.1.02b.

- Avramidis, E., and B. Norwich. 2002. “Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Integration/Inclusion: A Review of the Literature.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 17 (2): 129–147. doi:10.1080/08856250210129056.

- Bailey, J. 2004. “The Validation of Scale to Measure School Principals’ Attitudes Toward the Inclusion of Students with Disabilities in Regular Schools.” Australian Psychologist 39 (1): 76–87. doi:10.1080/00050060410001660371.

- Balti Uuringute Instituut. 2015. Õpetajate täiendusõppe vajadused. Lõpparuanne. http://dspace.ut.ee/bitstream/handle/10062/45196/Opetaja_taiendoppe%20vajadus.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Basic Schools and Upper Secondary Schools Act. 2010. Riigi Teataja I, 2010,41,240. http://riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/ee/530102013042/consolide.

- Basic Schools and Upper Secondary Schools Act. 2019. Riigi Teataja I, 2019,120. http://riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/ee/Riigikogu/act/503062019007/consolide.

- Biesta, G., M. Priestley, and S. Robinson. 2015. “The Role of Beliefs in Teacher Agency.” Teachers and Teaching 21 (6): 624–640. doi:10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325.

- Billett, S. 2006. “Relational Interdependence Between Social and Individual Agency in Work and Working Life.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 13 (1): 53–69. doi:10.1207/s15327884mca1301_5.

- Bowen, N. K., and S. Guo. 2012. Structural Equation Modelling. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bruns, A. D., and C. C. Mogharberran. 2007. “The gap Between Beliefs and Practices: Early Childhood Practitioners’ Perceptions About Inclusion.” Journal of Research in Childhood Education 21 (3): 229–241. doi:10.1080/02568540709594591.

- Campbell, J., L. Gilmore, and M. Cuskelly. 2003. “Changing Student Teachers’ Attitudes Toward Disability and Inclusion.” Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 28 (4): 369–379.

- Grogan, M. 2013. The Jossey-Bass Reader on Educational Leadership. 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Häidkind, P., and K. Oras. 2016. “Kaasava Hariduse Mõiste Ning õpetaja ees Seisvad ülesanded Lasteaedades ja Esimeses Kooliastmes. [The Notion of Inclusive Education and Challenges for the Teacher in Kindergartens and the First Stage of School].” Eesti Haridusteaduste Ajakiri 4 (2): 60–88. doi:10.12697/eha.2016.4.2.04.

- Idol, L. 2006. “Toward Inclusion of Special Education Students in General Education: A Program Evaluation of Eight Schools.” Remedial and Special Education 27 (2): 77–94.

- Juutilainen, M., Metsäpelto, R. L., and A. M. Poikkeus 2018. "Becoming Agentic Teachers: Experiences of the Home Group Approach as a Resource for Supporting Teacher Students' Agency." Teaching and Teacher Education 76: 116–125.

- Kielblock, S. 2018. “Inclusive Education for All: Development of an Instrument to Measure the Teachers’ Attitudes.” Doctoral Dissertation, Justus Liebig University Giessen, Germany. Macquarie University Sydney, Australia.

- Kivirand, T., Ä Leijen, L. Lepp, and L. Malva. 2020. “Kaasava Hariduse Tähendus ja Tõhusa Rakendamise Tegurid Eesti Kontekstis: õpetajaid Koolitavate või Nõustavate Spetsialistide Vaade [The Meaning of Inclusive Education and Factors for Effective Implementation in the Estonian Context: a View of Specialists who Train or Advise Teachers].” Eesti Haridusteaduste Ajakiri 8 (1): 48–71. doi:10.12697/eha.2020.8.1.03.

- Kivirand, T., Ä Leijen, L. Lepp, and T. Tammemäe. 2021. “Designing and Implementing an In-Service Training Course for School Teams on Inclusive Education: Reflections from Participants.” Education Sciences 11 (4): 166. doi:10.3390/educsci11040166.

- Kline, R. B. 1998. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modelling. NY: Guilford Press.

- Larrivee, B. 1985. Effective Teaching for Successful Mainstreaming. New York: Longman.

- Larrivee, B., and M. D. Horne. 1991. “Social Status: A Comparison of Mainstreamed Students with Peers of Different Ability Levels.” Journal of Special Education 25: 90–101.

- Leijen, Ä, M. Pedaste, and L. Lepp. 2020. “Teacher Agency Following the Ecological Model: How it is Achieved and how it Could be Strengthened by Different Types of Reflection.” British Journal of Educational Studies 68 (3): 295–310. doi:10.1080/00071005.2019.1672855.

- Mahat, M. 2008. “The Development of a Psychometrically-Sound Instrument to Measure Teachers’ Multidimensional Attitudes Toward Inclusive Education.” International Journal of Special Education 23 (1): 82–92.

- Miles, S., and N. Singal. 2010. “The Education for All and Inclusive Education Debate: Conflict, Contradiction or Opportunity?” International Journal of Inclusive Education 14 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1080/13603110802265125.

- Miller, A. L., C. L. Wilt, H. C. Allcock, J. A. Kurth, M. E. Morningstar, and A. L. Ruppar. 2020. “Teacher Agency for Inclusive Education: an International Scoping Review.” International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–19. doi:10.1080/13603116.2020.1789766.

- Muthén, L. K., and B. O. Muthén. 2016. Mplus. Version 7.4 [Computer Software]. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

- Nelis, P., and M. Pedaste. 2020. “Kaasava Hariduse Mudel Alushariduse Kontekstis: Süstemaatiline Kirjandusülevaade [A Model for Applying Inclusive Education in the Context of Estonian Preschool Education: Systematic Literature Review].” Eesti Haridusteaduste Ajakiri 8 (2): 138–163. doi:10.12697/eha.2020.8.2.06.

- O'Rorke-Trigiani, J. 2003. “Attidues (ie Attitudes) Toward Inclusive Education of Elementary and Middle School Administrators, School Counselors, Special Education Teachers, Fifth Grade Regular Education Teachers, and Eight Grade English Teachers” Doctoral Dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park, USA.

- Odom, S. L. 2000. “Preschool Inclusion: What we Know and Where We Go from Here.” Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 20 (1): 20–27. doi:10.1177/027112140002000104.

- OECD. 2020. TALIS 2018 Results (Volume II): Teachers and School Leaders as Valued Professionals. TALIS, OECD. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/19cf08df-en.

- O’Laughlin, L., and J. C. Lindle. 2015. “Principals as Political Agents in the Implementation of IDEA’s Least Restrictive Environment Mandate.” Educational Policy 29 (1): 140–161.

- Peters, S. J. 2004. Inclusive Education: An EFA Strategy for all Children. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

- Priestley, M., G. J. J. Biesta, and S. Robinson. 2015. Teacher Agency: An Ecological Approach. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Räis, M.-L., M. Kallaste, and S.-L. Sandre. 2016. Haridusliku erivajadusega õpilaste kaasava hariduskorralduse ja sellega seotud meetmete tõhusus. Uuringu lõppraport. Eesti Rakendusuuringute Keskus CENTAR.

- Räis, M.-L., and M. Sõmer. 2016. Haridusliku erivajadusega õpilaste kaasava hariduskorralduse ja sellega seotud meetmete tõhusus. Temaatiline raport: kaasamise tähenduslikkus. Eesti Rakendusuuringute Keskus CENTAR.

- Ricci, L. A., S. B. Scheier-Dolberg, and B. K. Perkins. 2020. “Transforming Triads for Inclusion: Understanding Frames of Reference of Special Educators, General Educators, and Administrators Engaging in Collaboration for Inclusion of all Learners.” International Journal of Inclusive Education.

- Shade, R. A., and R. Stewart. 2001. “General Education and Special Education pre-Service Teachers Attitude Toward Inclusion.” Preventing School Failure 46 (1): 37–41. doi:10.1080/10459880109603342.

- Soukakou, E. 2012. “Measuring Quality in Inclusive Preschool Classrooms: Development and Validation of the Inclusive Classroom Profile (ICP).” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 27: 478–488. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.12.003.

- Spratt, J., and L. Florian. 2015. “Inclusive Pedagogy: From Learning to Action. Supporting Each Individual in the Context of Everybody.” Teaching and Teacher Education 49: 89–96. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2015.03.006.

- Sumbera, M. J., B. L. Pazey, and C. Lashley. 2014. “How Building Principals Made Sense of Free and Appropriate Public Education in the Least Restrictive Environment.” Leadership & Policy in Schools 13 (3): 297–333. doi:10.1080/15700763.2014.922995.

- Ullman, J. B. 2001. “Structural Equation Modeling.” In Using Multivariate Statistics, edited by B. G. Tabachnick, and L. S. Fidell, 4th ed, 653–771. Needham Heights: Allyn & Bacon.

- UNESCO. 1994. Final Report: World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality. Paris: UNESCO.

- Van Mieghem, A., K. Verschueren, V. Donche, and E. Struyf. 2020. “Leadership as a Lever for Inclusive Education in Flanders: A Multiple Case Study Using Qualitative Comparative Analysis.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 1741143220953608.

- Van Reusen, A. K., A. R. Shoho, and K. S. Barker. 2001. “High School Teacher Attitudes Toward Inclusion.” The High School Journal 84 (2): 7–20.

- Vlachou, A., and A. Fyssa. 2016. “Inclusion in Practice: Programme Practices in Mainstream Preschool Classrooms and Associations with Context and Teacher Characteristics.” International Journal of Disability, Development and Education 63 (5): 529–544. doi:10.1080/1034912X.2016.1145629.

- Wilczenski, F. L. 1995. “Development of a Scale to Measure Attitudes Toward Inclusive Education.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 55 (2): 291–299. doi:10.1177/0013164495055002013.

- Yan, Z., and K. F. Sin. 2015. “Exploring the Intentions and Practices of Principals Regarding Inclusive Education: an Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour.” Cambridge Journal of Education 45 (2): 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2014.934203.

- Yu, C. Y. 2002. “Evaluating Cutoff Criteria of Model Fit Indices for Latent Variable Models with Binary and Continuous Outcomes (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation).” University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA.