ABSTRACT

To meet society’s changing demands, the responsive development of curricula is vital, and curriculum developers need to increasingly foresee and incorporate changes into their curricula in a timely manner. However, responsive curriculum development is a complex problem for curriculum developers in vocational and (higher) professional education, and comprehensive research on this theme is scarce. This study focused on responsive curriculum development processes in a Dutch higher professional education institution (N = 77 experts). A group concept mapping study into the supportive factors of this process revealed six factors: (1) a vision of education and learning, (2) a continuous and iterative development process, (3) teamwork, (4) involving stakeholders, (5) a conducive environment and conditions, and (6) agency. Participating experts highlighted the importance of ensuring that equal attention is devoted to each of these factors. However, the results also reveal the challenges that curriculum developers face. To deal with these, a framework of factors is suggested to facilitate curriculum conversations in which developers can negotiate – and give meaning to – the desired change in the curriculum context.

Introduction

To ensure the provision of high-quality training for future professionals, it is crucial that curricula align with the evolving needs of society (Cedefop Citation2022). Curricula in vocational and higher professional education are built upon vocational qualifications, shaped by the prevailing perception of professional competences and influenced by years of national policy discourse (Young Citation2006). These vocational qualifications serve several key functions, including (1) representing the necessary skills and knowledge for specific professions or sectors; (2) guiding the development of vocational educational curricula; (3) enabling mobility between different career paths; (4) providing valuable insights, support, and incentives for students; and (5) offering a means to assess the adequacy of educational provisions (quality control) (Young and Hordern Citation2022).

In 2016, the World Economic Forum introduced the term ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ to capture the ongoing era characterised by digitalisation, automation, robotisation, and interconnectedness, all aimed at enhancing manufacturing productivity, efficiency, and competitiveness (Loumpourdi Citation2021). Avis (Citation2020) and McGrath (Citation2022) emphasised the growing recognition of the modernity of the economy and the transformative influence of global market forces, which drive innovation and customer-oriented dynamics considered pivotal for maintaining economic competitiveness. Additionally, there is a joint effort to establish consensus on achieving an inclusive and sustainable society (e.g. Coll, Taylor, and Nathan Citation2003; Raffe Citation2013; Rusert and Stein Citation2023). However, despite transformations in how individuals live, work, and interact – in terms of scale, scope, and complexity – professional qualifications have been adapted slowly to these societal and labour market changes (Loumpourdi Citation2021). Several studies assert that curriculum developers in vocational education are challenged to realign with technological and social forces, which are expected to bring about notable shifts in the nature of work (Avis Citation2020; Billett Citation2000; Davis et al. Citation2012; OECD Citation2014). If vocational education fails to respond, increasing complaints might arise from the labour market and (teachers in) educational institutions about the lack of relevance of such curricula (Shalem and Allais Citation2018; Wheelahan Citation2007; Young and Hordern Citation2022). For example, both capacity and quality problems could emerge (e.g. graduates will not find jobs, despite a growing number of vacancies, or employees will not possess the right knowledge or skills).

Based on this challenge, a rich and lively international scholarly debate about the future shape, educational value, or even disappearance of vocational and (higher) professional curriculaFootnote1 has emerged, in which two possible future forms of vocational education are considered: first, a path that is predominately based on college study and informed by sectoral rather than job-specific requirements and, second, internship-based preparation for a specific profession, but with some elements of education relevant to the sector and the organisation of work (Young and Hordern Citation2022). In addition, an integrated model of the above two forms is proposed to enable students to move between paths. Such a view has significant implications for the development of vocational curricula (Young and Hordern Citation2022). The pathways require the participation and leadership of expert teachers, curriculum developers, practitioners, and researchers who understand both the educational context and the (changing) professional practice (Hager Citation2011).

However, a recent explorative study conducted by Vreuls et al. (Citation2022) revealed that actors engaged in the process of curriculum development in vocational and higher professional education, including education researchers, teachers, and employer representatives, often struggle with comprehending and effectively navigating responsive curriculum development processes. Consequently, curriculum developers find themselves in need of support. Vreuls et al. (Citation2022) stressed that a pressing concern within vocational education lies in the sluggish pace of curriculum development, hindered by constraints that prioritise stability over a continuous state of change. The researchers identified numerous dynamic challenges at the organisational level, encompassing social, cultural, and political dimensions, faced by curriculum developers. These challenges manifest as intricate social-political issues during stakeholder involvement in the curriculum development process, an inflexible and unyielding (both institutional and organisational) context in which curriculum development is situated, and curriculum developers who are inadequately equipped to execute their tasks or are overwhelmed by their multitude of roles and responsibilities (Bens, Kolomitro, and Han Citation2020; Hawick, Cleland, and Kitto Citation2017; Vreuls et al. Citation2022). Whitehead et al. (Citation2013) depicted such challenges as a ‘carousel of ponies’. The ponies circle round and round on the curricular carousel in the continual rediscovery of unsolvable, or hard-to-improve, educational problems that reappear over time, often in different forms. The moving ‘carousel’ also depicts the continuous use of quick and simple, instead of well thought out, solutions to these challenges. These are not effective because they do not target the engine of the carousel. Whitehead et al. (Citation2013) argued that more research is needed to deepen the understanding of how to support curriculum developers in breaking this vicious cycle.

Acknowledging the importance of employing a responsive approach to ensure the effectiveness of vocational education in preparing future professionals (Cedefop Citation2022), McGrath (Citation2022) highlighted the abundance of literature on the broader debate while noting the scarcity of writing concerning the implications for the development of vocational education curricula. Similarly, Cedefop (Citation2022) advocated for further research to enhance comprehension of the underlying processes involved in the responsive development of curricula. Additionally, Vreuls et al. (Citation2022) emphasised the necessity for additional research into the factors that facilitate curriculum developers. The aim of the current study is to examine the perspectives of experts on these processes and supportive factors, which hold institutional, national, and international significance within the ongoing discourse surrounding the future structure and educational importance of vocational and (higher) professional curricula. Studying these processes can encompass three phenomena (Goodlad Citation1979). The first phenomenon is substantive, which includes various aspects of a curriculum, such as goals, subject matter, and materials. The second phenomenon is socio-political, involving the political and social processes inherent in curriculum development. The third phenomenon is technical-professional, which encompasses the actual design, improvement, and implementation of curricula in practice. To gain an understanding of the key supportive factors associated with responsive curriculum development from a process-oriented perspective, this study primarily adopts a social-political and technical-professional approach.

Theoretical framework

Responsive curriculum development

Vocational education curricula are learning and development programmes to educate students in the knowledge, skills, and competences necessary for their future jobs (European Commission Citation2012). Besides domain-specific knowledge and skills, curricula also encompass more general objectives, such as active citizenship, personal development, and well-being (European Commission Citation2012). Developing such curricula is defined as an ‘intentional process or activity directed at (re)designing, developing, and implementing curricular interventions in formal or corporate education’ (Goodlad Citation1994). Curriculum development processes are often executed on the basis of analysis-design-development-implement-evaluate models (ADDIE; Branson Citation1978).

All these ADDIE steps are needed to accomplish a strong new curriculum and include activities such as performing problem, task, context, and content analysis; designing components of the curriculum (e.g. aims, objectives, learning, and instructional strategies, assessments); developing and revising curriculum prototypes; implementing the curriculum in practice; and evaluating the quality of the prototypes or final deliverable (Branson Citation1978). However, as far back as 1977, Halliburton provided an account of curricula becoming obsolete, attributing it to the ever-evolving role of education that continuously adapts to meet broad historical and social demands, emerging trends within professional education itself, or paradigmatic shifts and alterations in accepted disciplinary assumptions. Halliburton (Citation1977) categorised curricular change into three distinct processes of curriculum planning: (1) mechanism or statics, denoting a tinkering approach or maintenance of the curriculum rather than a complete overhaul; (2) dualism, representing curriculum changes that oscillate between popular trends of emphasis; and (3) knowledgism, emphasising alterations in disciplinary content. Halliburton (Citation1977) also emphasised that underlying assumptions, values, and practices of curriculum developers significantly influence the selection of the change processes utilised.

In practice, these processes are generally lengthy and cumbersome (Vreuls et al. Citation2022). However, when meeting current rapid changes and demands in society and professional practice, time is short (Vreuls et al. Citation2022). In addition, the connection between vocational education and the professional field is under pressure due to the pace of social and technological developments (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development OECD Citation2014. Given this dynamic, the OECD (Citation2014) argues that there is a need for responsiveness in vocational education. To be responsive, Cedefop (Citation2013, Citation2018, Citation2021) indicated that feedback mechanisms (formal and informal) of VET systems to labour market needs are increasingly important.

Responsiveness refers to the extent to which vocational education is able to respond in a timely manner to changes in the labour market and deliver professionals who are, and continue to be, employable in that market (e.g. De Vries Citation2016; Hoeve, Van Vlokhoven, and Nieuwenhuis Citation2021; OECD Citation2014; Vreuls et al. Citation2022). As such, a responsive curriculum development process is a cyclic process that increasingly involves a recalibration of the initiated processes and demands a way of thinking and working that delivers sufficient guarantees of quality (De Vries Citation2016; Hoeve, Van Vlokhoven, and Nieuwenhuis Citation2021; OECD Citation2014; Vreuls et al. Citation2022). This process requires cooperation with professionals in the field (Dutch EducationDutch Education Council [Onderwijsraad] Citation2014; OECD Citation2014) and, accordingly, agile, participative curriculum development models, which offer sufficient opportunities to respond in a timely manner to developments in the field (e.g. Allen and Sites Citation2012; Nieuwenhuis, Smulders, and Sessink Citation2021). In accordance with this premise, Nieuwenhuis et al. (Citation2021) presented a ‘responsive model’ for curriculum development (see ). This model emphasises interactive collaboration and co-makership among curriculum developers throughout every stage of curriculum development. The proposed approach entails utilising vocational qualifications as a framework of guidance rather than as an initial basis.

In the same vein, Könings et al. (Citation2007) argued that to deal with a changing society, continuous, iterative participatory curriculum development is important. They proposed an interdisciplinary spiral model of participatory design. The model consists of repeated cycles of planning, implementation, observation, and reflection. This model also provides useful guidelines for curriculum developers on when and whom to involve in each of these phases.

Vreuls et al. (Citation2022) mentioned the importance of stakeholder involvement in responsive curriculum development processes; however, they argued that to better understand how to support curriculum developers in this respect, consideration must be given to the further identification of factors affecting the responsive curriculum development process, as they play a significant role in the design decisions developers make and the delivery of a curriculum. This is a complicated issue, as a large part of the development process, factors that support this process and developers’ understanding remain implicit, both regarding the decisions they make and the resulting educational designs (Bouw, Zitter, and de Bruijn Citation2021). Understanding these factors may assist curriculum developers in reflecting on and anticipating the challenges regarding each development step and preparing them with effective alternative strategies. Each factor can be evaluated and considered a possible point of leverage for change (Anakin et al. Citation2018). However, to date, comprehensive studies on the factors supporting responsive curriculum development processes are lacking (Bhat, Pushpalatha, and Praveen Citation2017). The current study uncovers key factors (and their importance and feasibility) that inform, structure, and support responsive curriculum development.

Supporting factors

Although factors that support such a responsive curriculum development process remain unknown, there is a long tradition of studies that have explored those that affect (traditional) curriculum development processes, which are useful as input for this study (e.g. Anakin et al. Citation2018; Conrad and Pratt Citation1986; Halliburton Citation1977; Lattuca and Stark Citation2009; Viennet and Pont Citation2017).

For instance, Halliburton (Citation1977) emphasised the influential role played by curriculum developers, as their assumptions, values, and habits shape the curriculum development process. Aligning with Halliburton (Citation1977), Lattuca and Stark (Citation2009) adopted a socio-cultural perspective when considering curriculum development and roughly categorised influencing factors into two groups within their ‘academic plan model’: (1) external influences encompassing market forces, government policies, accrediting agencies, and disciplinary associations; and (2) internal influences encompassing institutional factors such as college missions, resources, and governance, as well as unit-level factors including faculty, discipline, and student characteristics. Conrad and Pratt (Citation1986) referred to these internal and external influences as ‘curricular design variables’ or ‘input variables’ that necessitate consideration during the decision-making process of curriculum developers. Both models concur regarding the non-linearity of the process and the multitude of influencing factors. Further, Lattuca and Stark (Citation2009) posited that curriculum developers yield two types of outcome variables: curriculum design outcomes and educational outcomes. The present study primarily focuses on curriculum design outcomes, which encompass the decisions that shape the academic plan.

Anakin et al. (Citation2018) conducted a study on the contextual nature of university-wide curriculum change. They divided the influencing factors into six factors that supported curriculum development at different levels of the universities involved: ownership (i.e. a shared responsibility, motivation, and scholarship); resources (i.e. control, distribution, and professional development); academic identity (i.e. teacher identity, territory, and reputation); leadership (i.e. vision and recognition); students (i.e. their learning needs and the benefits of innovative approaches to learning and student success); and quality assurance (i.e. compliance with the requirements).

Anakin et al. (Citation2018) noted, however, that the nature of curriculum development and the associated influencing factors were found in their specific contexts and argued for the need to investigate and clarify which factors are common across university settings.

In the same vein, a literature review by Viennet and Pont (Citation2017) showed that, at the national and international levels, the present complexity of curriculum development leads to a large number of factors that need to be taken into account when shaping a coherent curriculum development strategy, namely (1) smart policy design (e.g. a clear, compelling, and inspirational vision; policy tools, such as salary, training, and career paths; resources), (2) inclusive stakeholder engagement (e.g. communication, involvement, and transparency of responsibilities), and (3) a conducive environment (e.g. institutions, including rules, norms and strategies; capacity; policy alignment). They developed a framework based on the aforementioned factors. It assumes that curriculum development (and implementation) is an iterative process.

Viennet and Pont (Citation2017) identified several reasons why curriculum development processes are often ineffective, such as the lack of (recognition of the importance of) stakeholder involvement and the failure to identify the need to adapt curriculum development frameworks to new complex and changing systems. They argued that it is necessary to review current frameworks and approaches and adapt them to the 21st century.

Since several studies show that curriculum developers at the organisational level struggle with responsive curriculum development (e.g. Nieveen and van der Hoeven Citation2011; Nieveen, van den Akker, and Resink Citation2010; Pieters, Voogt, and Pareja Roblin Citation2019), it is questionable whether new answers to these challenges can be found by examining them in that context. Hence, this study aims to provide insight into the factors supporting the responsive curriculum development process from experts’ points of view. It also explores experts’ visions of the importance and feasibility of these factors.

Two research questions guided this exploration: (1) Which different factors support a responsive curriculum development process? and (2) How do experts value these factors in terms of importance and feasibility?

Materials and methods

A group concept mapping (GCM) method was used to uncover the supportive factors of responsive curriculum development processes, following Rosas and Kane’s (Citation2012) approach. GCM is a comprehensive structured mixed method for the fast and thorough generation, organisation, and visualisation of ideas from a group of participants. It provides insights into the conceptual knowledge of the participants, offers the opportunity for discussion, and assists the participants in reaching and identifying an objective consensus. The analysis, in the form of thematic clustering, provides a common understanding and picture of the factors supporting the responsive curriculum development process and of the importance and feasibility of each factor.

Curriculum development in the Dutch educational context

This study took place at a higher professional education institution in the Netherlands. This institution offers undergraduate tracks, professional bachelor’s and master’s degrees, and postgraduate programmes for specific professions, which correspond with ISCED level 5 and EQF levels 5 and 6. Curriculum developers in professional education in the Netherlands have considerable autonomy in developing curricula. Curricula are mostly developed by teams of teachers, sometimes extended to include other stakeholders (e.g. students, professionals from the associated professional field, clients, educationalists, and/or managers).

Although the current study was carried out in this context, the results are expected to be useful for other circumstances in which the connectivity between education and changes in society and professions is an important issue.

Participants

We recruited curriculum development experts tenured at a higher professional education institution to participate in the study based on the criterion that they had played an important role in curriculum development for a minimum of two years (82% had more than 5 years of experience). Most participants were members of a curriculum committee (curriculum development experts based on their experience), educational advisers (trained to develop curricula), or members of educational research groups/educational scientists. Of the participants, 56% had finished a Master of Science degree, 26% had completed a PhD, 6% had finished a Bachelor of Science degree, and the remaining 12% did not respond to this question. Rosas and Kane (Citation2012) suggested that 20 to 35 participants are needed for each step of a GCM method.

These guidelines were followed by involving 22–29 experts per step, leading to a total of 77 experts (53% women, 34% men, 13% unknown). Due to the considerable time investment, not all participants were able to participate in every step of the study. To ensure sufficient participants per step, we invited other experts to participate in each research step (with similar expertise and using the same inclusion criterion).

Data collection

Procedure

The GCM method distinguishes five steps: (1) preparation by the principal researcher, (2) brainstorming by the experts, (3) structuring/editing of the generated statements by the research team, (4) thematic sorting of the statements by the experts, and (5) evaluation by the experts. After these five steps, the research team analysed, interpreted, and reported the results. An online environment, Groupwisdom©, was used for both data collection and analysis. For each step, the experts were given four weeks of access to the online research environment, with a reminder after two weeks.

Step 1: Preparation

First, the research team obtained ethical approval from the Open Universiteit Ethical Committee (cETO): U/2020/01656/MQF. Second, the Groupwisdom© environment was prepared, and informed consent forms were developed and uploaded to the site. In this environment, each participant remained anonymous, meaning that their identity was not visible in the system, and there were no additional face-to-face meetings. The experts were asked to create their own usernames and passwords (to be able to return to their answers). Third, a focus prompt was developed to generate and sort ideas based on the following research question:

Modern curricula in vocational and (higher) professional education must be able to handle rapid changes in the relevant field of work. Generate as many statements as possible about the actors, factors, and preconditions that play a role in the development process of such curricula by curriculum development teams.

Lastly, the experts were recruited and invited to participate through emails sent to their offices or via their managers.

Step 2: Brainstorming – Generating statements

In this second step, 22 experts participated individually in the Groupwisdom© environment. They generated as many statements as possible regarding the focus prompt. The Groupwisdom© environment allowed them to view the statements generated by other experts. Seeing other experts’ statements stimulated them to generate more statements. The experts had two to four weeks to complete this step. During this time, they could pause and return indefinitely to add more statements. This process resulted in an unstructured initial list of 100 factors supporting responsive curriculum development.

Step 3: Structuring/editing the generated statements

The main purpose of the third step was twofold: to ensure that all the generated statements (1) addressed the focus prompt and (2) were comprehensible for the experts for sorting and rating in the fourth step. First, the research team members individually reviewed the statements in detail and proposed including or excluding (parts of) the statements. The criteria for the selection of statements included the following: (1) Is the statement relevant to the focus prompt? (2) Are there identical or comparable statements? In this case, which is the most representative one? and (3) Can the statement be rated? Second, statements that contained more than one idea were divided to ensure that every statement represented a unique idea. Third, to enable sorting of the statements, the researchers individually assigned codes to each one. Codes are words that place ideas under the same higher-order themes. Lastly, the statements were uploaded again to the Groupwisdom© (2021) software system, randomised, and made available to the experts for sorting and rating in Step 4.

Step 4: Sorting the generated statements

In this step, 26 experts sorted the statements into groups related to the prompt and labelled each group. To do so, the following instruction was given in the Groupwisdom environment©:

Welcome! In this activity, you are asked to sort a list of statements.

To do so, sort each statement by adding it to a stack in such a way that it makes sense to you. Sort statements according to their meanings. In this way, each stack will contain a set of substantive, related ideas.

Each expert determined the number of labels and named them based on their own interpretation of (the underlying concepts of) the statements. The experts were free to decide on the number of stacks formed and the labels associated with them. In addition, experts received a note informing them that the statements should not be sorted by simply labelling them based on adjectives (e.g. easy/difficult to achieve, important/not important) or by categorising a stack as ‘remaining’ or ‘other’.

Step 5: Evaluation of the statements

In this final step, 29 experts rated each statement on a 5-point Likert scale based on two criteria: (1) How important is this statement? (1 = relatively unimportant to 5 = extremely important) and (2) How feasible is this statement? (1 = very difficult to implement to 5 = very easy to implement).

Data analysis

The data analysis concerned the evaluation of Steps 4 and 5. The data analysis in Step 4 involved determining which statements were more often sorted together into groups and which were not. To do this, multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) was used. This technique converts experts’ ‘raw’ qualitative sorting data into quantitative information in a similarity matrix. An individual similarity matrix contains individual experts’ raw groups of statements consisting of as many columns and rows as the number of statements. The total similarity matrix merges all individual similarity matrices.

When experts sort two statements together, a ‘1’ is assigned to the cell; otherwise, a ‘0’ is used. MDS generates a stress index (a value between 0 and 1) to indicate the extent to which the concept map (i.e. the output of the GCM method) reflects the raw sorting as represented by the similarity matrix.

Second, a hierarchical cluster analysis was performed. This analysis provides insights that support the decision regarding a suitable number of statement clusters. This statistical procedure iteratively merges statements step by step until all the statements are combined into one cluster.

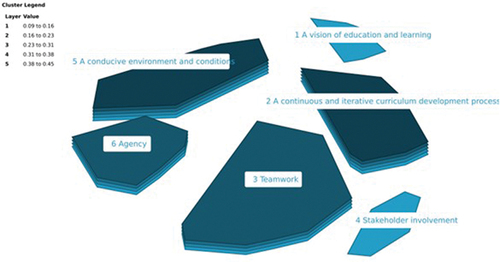

In their meta-analytical study, Rosas and Kane (Citation2012) concluded that to decide on the number of clusters, the procedure should preferably start with 16 cluster solutions and continue until 5 clusters are obtained, seeking a balance between revealing the bigger picture and providing sufficient detail. For this analysis, the Groupwisdom© software produced a map for each cluster solution (see the ‘cluster map’ in ).

To decide on the number of clusters, the system calculates the average bridging values per cluster (values between 0 and 1). A bridging value represents the extent to which statements within the cluster are sorted with nearby statements. A lower bridging value means that a statement within the cluster is more often sorted with nearby statements, whereas a higher bridging value indicates that the statement is sorted together with statements that are further apart. In contrast to factor analysis, there is no correct number of clusters. In accordance with Kane and Trochim’s (Citation2007) suggestions, the research team took these bridging values in each cluster solution into account (i.e. the statements with the lowest bridging values represent the best suitable cluster), assisted by the Groupwisdom© software.

In addition, the research team reviewed the content of each cluster to determine which overarching theme best represented the majority of the included statements. To decide on the labels of the conceptual clusters, the researchers checked the suggestions given by the software, which uses an algorithm to identify the best-fitting cluster labels.

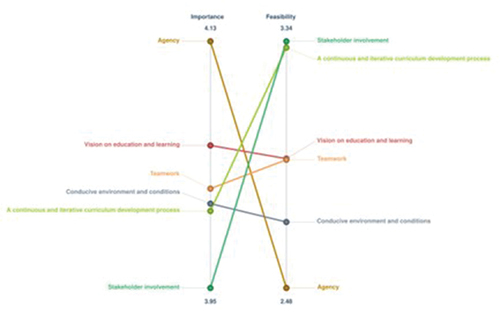

Lastly, the data from Step 5 (i.e. rating each statement based on two criteria: [1] importance and [2] feasibility) were analysed. The analysis of the rating data resulted in a ladder graph. A ladder graph presents the correlation between ratings of importance and feasibility in each cluster (i.e. whether a very important cluster was also considered highly feasible or if a very important cluster was considered difficult to achieve).

Results

Generating and editing statements (steps 2 and 3)

In Step 2, the experts generated 100 statements (e.g. co-creation with professional practice; focus on relinquishing existing doctrines; develop modular and non-sequential programmes; a flexible mindset; an agile organisation that supports educational development). When editing these statements, the research team agreed to retain all the statements, and only one statement was split into two statements because it consisted of two distinctive ideas.

Analysis of the sorted data (step 4)

The data analysis in Step 4 determined which statements were more often sorted together in groups and which were not. First, MDS showed an acceptable stress index of 0.24, indicating satisfactory reliability (Rosas and Kane Citation2012).

Second, when discussing the results of the hierarchical cluster analysis, the research team agreed on a six-cluster solution (see ; this figure presents the cluster map with six clusters that depict the influencing factors on responsive curriculum development). The bridging values in this cluster solution varied between 0.09 and 0.45, and the cut-off point for our decision was < 0.50 (i.e. the chosen cluster solution did not contain a bridging value of < 0.50).

Third, the clusters were labelled. To do so, the research team reviewed the content of each cluster to determine which overarching theme represented the majority of the statements in the cluster. Each researcher checked the suggestions for labels given by the software, which uses an algorithm to identify the best-fitting cluster labels. The solutions were discussed until consensus was reached.

The research team decided on the following labels for the clusters: a vision of education and learning; a continuous and iterative development process, teamwork, involving stakeholders; a conducive environment and conditions; and agency. Assessing the average bridging values per cluster, the most coherent clusters were a vision of education and learning and stakeholder involvement, with average cluster bridging values of 0.09 to 0.16, meaning that the experts agreed most consistently on the sorting of the statements in these clusters. These cluster labels, or factors, may look generic; nonetheless, the experts’ statements within these clusters provide a further specification of their meaning for responsiveness (also see ), which will be further explained and related to the literature hereafter.

Table 1. Factors, subtopics, and illustrating quotes.

A vision of education and learning

A vision of education and learning was identified as one of the factors supporting a responsive curriculum development process (bridging value: 0.09–0.16). This factor encompasses four key aspects: the vision itself, the desired content, the coherence of the curriculum, and the structure of the curriculum. Notably, a strong relationship was observed between this factor and the continuous and iterative curriculum development process factor, which became apparent by their close proximity. A shared curriculum vision, coupled with open content and coherence, and a clear structure play a pivotal role in fostering a responsive curriculum development process. In particular, a shared vision of an open and flexible curriculum seems relevant for responsiveness.

This shared vision engenders emotional and social support for the necessary ongoing and iterative changes to the curriculum while also providing social structures to facilitate the dissemination of innovations (Anakin et al. Citation2018; Viennet and Pont Citation2017). This finding is underscored by various statements emphasising the realisation of a shared vision of a flexible, open curriculum, such as ‘Create an open curriculum’ (Statement 4), ‘Create a shared vision’ (Statement 35), and ‘Develop modular and non-sequential education’ (Statement 47).

A continuous and iterative curriculum development process

A continuous and iterative curriculum development process also emerged as a supporting factor (bridging value: 0.38–0.45). The topics that contributed to this factor, such as smart policy design and alignment, as well as continuous, iterative, and participatory development processes, confirm Vreuls et al.’s (Citation2022) findings. According to their study, a responsive curriculum development process must be ongoing, iterative, and participatory, with a strong connection to professional practice in order to be responsive.

The influence of these supportive conditions for responsiveness is demonstrated in statements such as: ‘Curriculum development is an iterative process’ (Statement 96); ‘Including examination boards in curriculum development’ (Statement 59); and ‘Participative design with all parties involved (the professional field, students, teachers, users)’ (Statement 33).

Teamwork

Teamwork was identified as another supporting factor (bridging value: 0.31–0.38). The topics that contributed to this factor encompassed ownership, team composition, team competencies, communication, and agency. This underscores the notion that entrusting curriculum development to teams serves as a favourable starting point for fostering responsive curriculum development.

Particularly pertinent to responsiveness, the experts highlighted the importance of ‘hybrid professionals’ (i.e. teachers who also hold positions in professional practice). This sentiment is demonstrated in various statements, such as ‘Stay ahead! Ensure that all stakeholders of the curriculum participate in future-oriented developments in professional practice’ (Statement 79). These hybrid professionals play a valuable role in keeping the curriculum up-to-date by actively seeking opportunities for change and generating innovative ideas. Furthermore, they contribute to the agency aspect by advocating for new ideas and pioneering their realisation and implementation.

Anakin et al. (Citation2018) also identified ‘ownership’ as a crucial influencing factor, whereas Viennet and Pont (Citation2017) solely incorporated stakeholder transparency, engagement, and communication. However, these authors did not specify the desired composition of a team, the requisite team competencies, or the importance of agency in their models, all of which emerged as important in our context, based on our data.

Involving stakeholders

This study also identified the supporting factor involving stakeholders (bridging value: 0.09–0.16), which aligns with previous findings by Könings et al. (Citation2017) and Vreuls et al. (Citation2022). This factor encompasses the consideration of which stakeholders to involve, when to involve them, and the establishment of sustainable relations. These findings underscore the importance of the sustained engagement of diverse stakeholders throughout the entire curriculum development process. It confirms that a responsive development process benefits from insights provided by different stakeholders, as they contribute diverse expertise in curriculum design and possess valuable professional and contextual knowledge (Alexander and Hjortsø Citation2019; Viennet and Pont Citation2017).

Numerous statements exemplified the relevance of stakeholder involvement, including ‘Build sustainable relationships with internal and external stakeholders’ (Statement 81) and ‘Develop through co-creation; involve all (internal and external) stakeholders from the outset: in needs analysis, trend analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation’ (Statement 97).

A conducive environment and conditions

A supporting factor pertaining to the responsive curriculum development process was the presence of a conducive environment and conditions (bridging value: 0.38–0.45), which aligns with the findings by Viennet and Pont (Citation2017). This factor encompassed various aspects, including knowledge and professional development, availability of (financial) resources, measurable results, flexibility in adapting or relinquishing existing doctrines, principles, and frameworks, as well as the presence of tranquillity. Within this factor, the interconnectedness between organisational development and curriculum development became apparent. Experts emphasised the importance of organisational flexibility, continuous learning, and allowing room for ongoing change in the entities involved in curriculum development, including their rules, frameworks, boards, and committees. This notion was exemplified in statements such as: ‘Relinquishing existing doctrines’ (Statement 65), ‘Ensuring sufficient knowledge and the professional development for the team and its members. Integrating curriculum development with team professional development’ (Statement 98), and ‘Providing teams with ample time and (financial) resources’ (Statement 72). Adequate attention to this factor is imperative for the success of responsive curriculum development, as its inadequate organisation has been shown to have the most detrimental effects on the process (Vreuls et al. Citation2022).

Agency

Lastly, agency emerged as a supporting factor (bridging value: 0.31–0.38). This factor encompassed various aspects, including self-efficacy, flexibility, a flexible mindset, vigour, willingness to change, leadership, and the willingness to challenge deeply ingrained beliefs, traditions, or established practices. Agency, defined as the capacity of actors to ‘critically shape their responses to problematic situations’ (Priestley, Biesta, and Robinson Citation2012, 8), forms a strong and pivotal foundation for the success of responsive curriculum development processes. Statements that exemplified this perspective included ‘Demonstrate educational leadership by relinquishing existing “doctrines”’ (Statement 31) and ‘Maintain flexibility in one’s mindset’ (Statement 57). There is a clear relationship between agency and all other factors, as the need for agency is emphasised in the various topics related to the other factors identified by the experts. Consistent with Harris and Graham’s (Citation2019), our study suggests that agency provides a crucial basis for addressing the institutional barriers encountered by curriculum developers in their pursuit of responsive curriculum development.

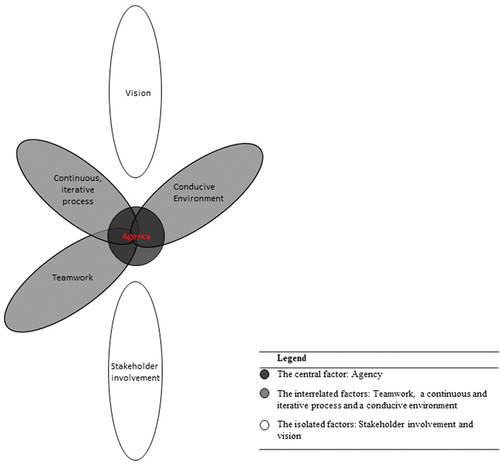

The close connection between agency and a conducive environment (institutional barriers) becomes visible in the related topics and the of these factors (in line with Leibowitz et al. Citation2012; see ). Aligning with this finding, Graf and Lohse (Citation2022) described certain modes of change closely linked to the social-political context, with stakeholders’ agency playing a significant role in shaping curriculum development. They acknowledged that change is driven by the agency and innovative potential of institutional actors, challenging the notion that change can only be externally induced through disruptive shocks, leading to radical transformation.

They describe four modes of change: (1) displacement (i.e. where existing rules are replaced by new ones), (2) layering (i.e. where new rules are added without replacing existing ones), (3) drift (i.e. where shifts occur in the external conditions of a rule, altering its impact while formally maintaining the same rule), and (4) conversion (i.e. where rules are interpreted and implemented in new ways while formally remaining unchanged). When advocates of the status quo possess significant veto powers, curriculum developers are more likely to opt for indirect modifications to the curriculum, such as layering and drift, rather than advocating for displacement or conversion. When institutions provide stakeholders with sufficient autonomy to develop the curriculum based on their own assumptions, values, and habits, drifts and conversions are more likely to occur (Graf and Lohse Citation2022).

However, the negative influence of prescriptive curriculum frameworks and a culture of accountability and performativity (e.g. inspection regimes) often undermine the degree of agency held by curriculum developers (Harris and Graham Citation2019). In our study, due to its relation to the other supporting factors, agency assumed a central role in the model compared to Anakin et al.’s (Citation2018) and Viennet and Pont’s (Citation2017) interpretations, in which only certain elements of agency (e.g. leadership, norms, and strategies) are considered.

Analysis of the rating data (step 5)

The analyses of the ratings of importance and feasibility revealed that all the clusters were rated as very important (M = 3.95–4.13) but neutral or moderate regarding feasibility (M = 2.48–3.34). The agency cluster was considered the most important cluster (M = 4.13). The cluster was also seen as difficult to implement (M = 2.48). The respondents deemed involving stakeholders the easiest cluster to implement (M = 3.34). This cluster ranked lowest in importance (M = 3.95). The correlation (Pearson product-moment) between the ratings of importance and feasibility was highly negative (r = −.82).

A significant difference was detected between the mean values of importance and feasibility (at the cluster level): a vision of education and learning (t(32) = 10.29, p < .000), a continuous and iterative development process (t(20) = 4.89, p < .000), teamwork (t(48) = 9.47, p < .000), involving stakeholders (t(28) = 4.78, p < .000), a conducive environment and conditions (t(28) = 13.45, p < .000), and agency (t (34) = 16.02, p < .000).

The ladder graph (see ) shows the relative positions of the clusters when compared based on the average ratings of the two values. On the left-hand side of the ‘ladder’, the clusters are ranked on importance and on the right-hand side, on feasibility (i.e. how easy/difficult they are to implement). The most important (agency) and most feasible (stakeholder involvement and a continuous and iterative development process) clusters are presented at the top of the ladder, with a decrease in importance and feasibility towards the bottom of the ladder.

These results underline the challenges curriculum developers at vocational educational institutes face when responsively developing curricula: important factors are mostly judged as less feasible, whereas factors that are less important are judged as relatively feasible (e.g. agency, stakeholder involvement, and conducive characteristics and principles of curriculum development). The conclusions based on RQ1 are as follows: (1) all the factors were rated as important (>3.95); (2) stakeholder involvement was rated the least important, but the most feasible; and (3) agency was rated the most important, but the least feasible. Regarding the success of responsive curriculum development processes, the experts indicated that agency is relatively hard to implement and requires support.

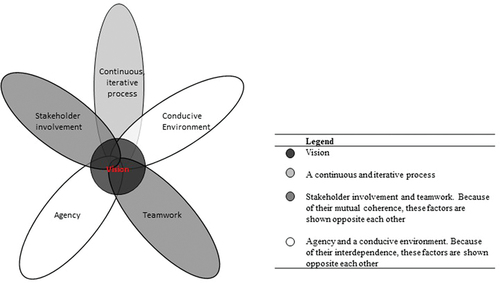

Discussion

The present study explored which factors support responsive curriculum development processes (RQ1) and analysed these factors’ importance and feasibility (RQ2). Six important supportive factors emerged: a vision of education and learning, a continuous and iterative development process, teamwork, involving stakeholders, a conducive environment and conditions, and agency. Furthermore, the explicit relationship between the aforementioned factors and their importance in fostering responsiveness within the curriculum development process was elucidated through illustrative statements provided by the participating experts. Building upon these findings, we propose that to develop curricula in a responsive manner, it is important to devote equal attention to each of these factors. We have depicted this interdependence and complementarity of the factors using the framework shown in . In accordance with Vreuls et al. (Citation2022), we suggest that this development process starts with a shared vision and a well-composed team consisting of internal and external stakeholders.

This curriculum development team should conduct a continuous iterative curriculum development process (Vreuls et al. Citation2022) in a conducive environment (Viennet and Pont Citation2017), in which mandates are arranged and developers are able to act as change agents (Priestley, Biesta, and Robinson Citation2012).

However, our data revealed the central position of agency, instead of vision, arising from environmental challenges. This central position became apparent from participants’ statements regarding agency within the conducive environment factor and from the presence of this factor within other factors (e.g. statements such as ‘Relinquishing existing doctrines’ and ‘challenging deeply ingrained beliefs, traditions, or established practices’).

The continuous and iterative development process, teamwork, conducive environment, and agency factors were interrelated, but vision and stakeholder involvement seemed to be more isolated activities (see ). This isolated position of both factors could mean that they are clearly defined and demarcated, but it could also indicate that experts perceived only a few links between these factors and the other factors representing their current (traditional) curriculum development process.

Based on the bridging values and locations of the themes in the cluster map solution, the framework presented in represents the actual situation. Curriculum developers mainly face hindrances regarding unsatisfactory environmental factors, such as institutional and organisational frameworks and regulations, resulting in a greater emphasis on agency as a factor to escape this ‘institutional concrete’. However, the experts also recognised the agency factor as being the least feasible. It seems that curriculum developers are facing ‘wicked problems’Footnote2 within the different levels of organisations, as our data pointed out continuously negative interactions and counterbalances or conflicts between these factors. In particular, the fact that agency is approached as what Waterman and Peters (Citation1982) called ‘a soft factor’ (i.e. a factor that is difficult to influence) appears problematic. The challenge is to turn this factor into a ‘hard factor’ and embed it in the strategy and structure of an organisation rather than leaving it to chance or to the team.

This can be accomplished by determining how goals will be achieved, discussing whether staff are prepared for changes and determining the manner of cooperation, hierarchy, and mandates within (every level of) the organisations involved (Waterman and Peters Citation1982).

Further, discussing the differences between the responsive situation and the current (traditional) one and mapping the interplay of factors provide tools to stopWhitehead et al.’s (Citation2013) running carousel of ponies. The analysis of the curriculum development context can be performed based on the framework presented in . This analysis can be used as a topic for discussion with the initiators of curriculum development. By doing so, enabling factors can be enhanced and hindering factors removed to prevent negative interacting or counterbalancing factors.

Such an approach also enables fine-tuning current policies and responsive curriculum development initiatives in vocational education institutions (Hoeve, Van Vlokhoven, and Nieuwenhuis Citation2021).

In the same respect, Anakin et al. (Citation2018) underlined the crucial importance of such an analysis at all levels of the organisations involved to address potential conflicts in the curriculum development process at the right level. In current practice, such challenges are often glossed over rather than analysed and profoundly addressed (Vreuls et al. Citation2022). An additional difficulty here is that many challenges are often signalled at other levels (e.g. the institutional, organisational, departmental, or team level) rather than thought through in advance (McKenney et al. Citation2015). As a result, they often remain invisible for a long time or are addressed at the wrong level. Nevertheless, by acknowledging them and addressing them at various organisational levels, we argue that structure can actually be enforced.

Our framework presented in can be categorised as a ‘reflective framework’ that may guide ‘curriculum conversations’ (e.g. see Fraser Citation2006; Myatt and Tomsett Citation2022).

This framework may serve to analyse a development process that can support the identification of possible areas of improvement, make more effective use of the structures of the organisations involved, or take into account the different conceptions of stakeholders to support the curriculum development process. These kinds of conversations are difficult to hold and do not take place automatically (Koeslag-Kreunen et al. Citation2018). Professionalisation programmes that intend to strengthen a faculty’s curriculum development skills will have to focus on facilitating critical conversations. Such conversations make the underlying assumptions and insights transparent and create new shared assumptions in such a way that the desired change makes sense for all the stakeholders involved (Koeslag-Kreunen et al. Citation2018). Therefore, developers must learn to focus not only on the artefacts of the curriculum but also on uncovering, sharing, evaluating, and modifying underlying basic assumptions and processes in these conversations (Schein Citation1992).

It is also important that superficial participation in discussions is prevented and that an understandable, common language is used (Fraser Citation2006). Hence, these conversations need to take place in partnerships at all levels of the institution, in which developers can negotiate – and give meaning to – the desired change in the curriculum context (Leeman et al. Citation2020). In addition, such conversations may create the ability to influence curriculum changes, encourage stakeholders to be more open to change, and enforce partnerships that are ‘constant, coherent, critically reflective and integrated into all aspects of the core business’ at all levels of the institution (Marshall Citation1998, 332). Moreover, ongoing critical conversations may enable educational institutions to deal with continuous change more effectively and may enable developers to lead, rather than passively undergo, responsive curriculum development processes in vocational education.

Our study responded to the need to translate existing traditional curriculum development approaches into responsive ones that fit 21st-century challenges (Viennet and Pont Citation2017). More specifically, our study provides unique insights into the supportive factors of a responsive curriculum development process. We presented a framework of factors () that invites curriculum developers at different layers in school organisations to consider (1) the vision of education and learning, (2) how to implement a continuous and iterative development process, (3) the teamwork and team composition required, (4) involving stakeholders and which stakeholders are important, (5) which environment and conditions are conducive, and (6) the necessary agency and mandates. Our framework adds a set of specific factors that support the responsiveness of a curriculum development process to existing frameworks. From a practical perspective, the presented framework may guide curriculum developers in several stages of the development process: (1) to check whether the progress is in line with ambitions during the design process, and (2) to evaluate the quality of the development process when it is realised and in action.

In contrast to curriculum development process models proposed by Conrad and Pratt (Citation1986) and Lattuca and Stark (Citation2009), which delineate factors as either internal or external influences on the process, the present study posits that supportive factors warrant contemplation as pivotal decision-making considerations throughout all phases of the process. It is imperative to seamlessly integrate the six factors into the educational environment and academic plan. This perspective advances beyond the models of Vreuls et al. (Citation2022; )) and Könings’ et al. (Citation2007), both of which exclusively incorporate stakeholder involvement as a decision-making consideration respectively solely at the inception and across all phases of the process. Consequently, the elucidations provided can aptly guide curriculum developers in rendering informed decisions to enhance the process’s responsiveness.

Implications for the VET curriculum debate

Vocational and (higher) professional curricula are of great importance, since they are linked to increasing productivity and employability and keeping pace with international competition (Cornford Citation1999). In response to the discussions surrounding the future form, educational value, and potential decline of vocational and (higher) professional curricula, we propose that in order for these curricula to thrive and provide effective training for future professionals, it is crucial to adopt a responsive approach to curriculum development. This means that curriculum developers should be capable of promptly addressing and adapting to the rapid changes inherent in the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Loumpourdi Citation2021), thereby ensuring the delivery of high-quality education. However, based on the current study, it can be argued that traditional curriculum development processes often do not achieve the desired level of responsiveness.

For example, at the organisational level, curriculum developers are hampered by rigid (institutional, organisational, and sometimes legal) frameworks, the limited involvement of stakeholders in the development process and a lack of agency on the part of designers and teachers.

We suggest that to be responsive, the following four conditions at three organisational levels are of great importance. First, at the institutional level, the reform of vocational education towards a more responsive model needs to start by tackling wider contextual issues and the long-held rigid visions of governments and the many key groups involved. Second, at the college/school level, professional qualifications need to be examined in a different way: they are no longer the starting point of curriculum development but rather serve as a frame of reference, as well as in quality controls. Third, at the departmental/team level, team leaders, curriculum developers, and teachers need to arrange mandates when given a considerable amount of autonomy to develop curricula.

Finally, these conditions do not occur automatically, and we assume that at all organisational levels, there is a need for more time, attention, effort, and the sustainability of a different – flexible—mindset and way of working, especially if a precondition for responsiveness presupposes a more open curriculum and continuous development process with various partners and different collective agreements.

Limitations and further research

A GCM approach was chosen as a suitable method for identifying the factors that support a responsive curriculum development process. From a methodological point of view, the GCM approach was implemented in line with key criteria, as suggested by Kane and Trochim (Citation2007) and Rosas and Kane (Citation2012). However, some of the common issues related to GCM may still have occurred.

For example, the participants’ reasoning remained mainly implicit because of the absence of the possibility of discussing their statements and sorting (e.g. participants sorted their statements individually according to their own reasoning of concepts, and there were no additional face-to-face sessions). As a result, the experts may have chosen different perspectives (e.g. addressing the questions as team members, team leaders, or initiators), which may have affected the feasibility, for instance. Furthermore, despite the anonymous environment, some participants may have refrained from expressing their opinions because they thought their ideas deviated too much from those of other experts.

Input for the current study was generated from experts in the context of Dutch higher professional education. Regarding the transferability of the findings, the factors affecting responsive curriculum development processes may differ depending on the educational systems in which the curriculum developers operate. For instance, the high degree of autonomy regarding curriculum design in the Netherlands may have influenced curriculum developers’ views (Thijs and Van den Akker Citation2009).

Further research is warranted to enhance our comprehension of responsive curriculum development challenges in professional or vocational education. This includes investigating whether our presented framework of factors effectively facilitates responsive curriculum development processes.

Additionally, it may be relevant to explore the applicability of our findings in other countries. Our research outcomes may also hold relevance for responsive curriculum development processes in different educational systems or countries, given the emphasis placed on the interconnection between professional or vocational education and societal and professional changes, which is recognised as a significant international concern. Today’s society is too dynamic to continue developing curricula in a conventional way. Steps need to be taken to arrive at other, more responsive approaches to curriculum development.

The (framework of) factors in the current study may contribute to supporting curriculum developers in responding more adequately to unforeseen changes in the nature of work in today’s and tomorrow’s society.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Open Universiteit Ethical Committee (cETO): U/2020/01656/MQF.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Hereafter, ‘vocational and (higher) professional education’ will be abbreviated as ‘vocational education’.

2. ‘Wicked problems’ are unstructured, complex problems. These problems have innumerable causes, are divergent and emergent, continuously evolving and associated with multiple social environments and actors, and have no single solution path. Wicked problems also have unpredictable side effects, which are, in turn, influenced by many dynamic social, cultural, and political factors. A characteristic of these problems is that they seem unsolvable (Hawick, Cleland, and Kitto Citation2017).

References

- Alexander, I. K., and C. N. Hjortsø. 2019. “Sources of Complexity in Participatory Curriculum Development: An Activity System and Stakeholder Analysis Approach to the Analyses of Tensions and Contradictions.” Higher Education 77 (2): 301–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0274-x.

- Allen, M. W., and R. Sites. 2012. Leaving ADDIE for SAM: An Agile Model for Developing the Best Learning Experiences. Alexandria, VA, USA: American Society for Training and Development.

- Anakin, M., R. Spronken-Smith, M. Healey, and S. Vajoczki. 2018. “The Contextual Nature of University-Wide Curriculum Change.” International Journal for Academic Development 23 (3): 206–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2017.1385464.

- Avis, J. 2020. Socio-Technical Imaginaries and the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Vocational Education in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Palgrave Pivot. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-52032-8_2.

- Bens, S., K. Kolomitro, and A. Han. 2020. “Curriculum Development: Enabling and Limiting Factors.” International Journal for Academic Development 26 (4): 481–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2020.1842744.

- Bhat, D., K. Pushpalatha, and K. Praveen. 2017. “Study of Faculty Viewpoints on Challenges and Factors Influencing Curriculum Development/Revision.” Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 11 (10): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2017/25697.10764.

- Billett, S. 2000. “Defining the Demand Side of Vocational Education and Training: Industry, Enterprises, Individuals and Regions.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 52 (1): 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820000200104.

- Bouw, E., I. Zitter, and E. de Bruijn. 2021. “Multilevel Design Considerations for Vocational Curricula at the Boundary of School and Work.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 53 (6): 765–783. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2021.1899290.

- Branson, R. K. 1978. “The Interservice Procedures for Instructional Systems Development.” Educational Technology 18 (3): 11–14. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44418942.

- Cedefop. (2013). Renewing VET provision: Understanding feedback mechanisms between initial VET and the labour market. Publications Office of the European Union. Cedefop Research Paper, No.(37). https://doi.org/10.2801/32921

- Cedefop. (2018). The Changing Nature and Role of Vocational Education and Training in Europe. Volume 3: The Responsiveness of European VET Systems to External Change (1995–2015). Publications Office of the European Union. Cedefop Research Paper, No. 67. http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/621137.

- Cedefop. (2021). Review and Renewal of Qualifications: Towards Methodologies for Analysing and Comparing Learning Outcomes. Publications References 107 Office of the European Union. Cedefop Research Paper, No. 82. http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/615021.

- Cedefop. (2022). The Future of Vocational Education and Training in Europe. Volume 1: The Changing Content and Profile of VET: Epistemological Challenges and Opportunities. Publications Office of the European Union. Cedefop Research Paper, No. 83. http://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2801/215705.

- Coll, R. K., N. Taylor, and S. Nathan. 2003. “Using Work-Based Learning to Develop Education for Sustainability: A Proposal.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 55 (2): 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820300200224.

- Conrad, C. F., and A. M. Pratt. 1986. “Research on Academic Programs: An Inquiry into an Emerging Field.” In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, edited by G. K. Davies and J. C. Smart, 235–273. Vol. 2. New York, USA: Agathon Press.

- Cornford, I. R. 1999. “Rediscovering the Importance of Learning and Curriculum in Vocational Education and Training in Australia.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 51 (1): 93–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636829900200072.

- Davis, J., T. Edgar, J. Porter, J. Bernadend, and M. Sarli. 2012. “Smart Manufacturing, Manufacturing Intelligence and Demand-Dynamic Performance.” Computers & Chemical Engineering 47 (20): 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compchemeng.2012.06.037.

- De Vries, B. 2016. [Een Permeabel Curriculum A Permeable Curriculum]. http://wijmakenhetonderwijs.nl/actueel/een-permeabel-curriculum-door-bregje-de-vries.

- Dutch Education Council [Onderwijsraad]. 2014. Een eigentijds curriculum [A contemporary curriculum]. Den Haag, The Netherlands: Excelsior.

- European Commission. 2012. Rethinking Education: Investing in Skills for Better Socio-Economic Outcomes (669 Final). Strasbourg, France: European Commission.

- Fraser, S. P. 2006. “Shaping the University Curriculum Through Partnerships and Critical Conversations.” International Journal for Academic Development 11 (1): 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13601440600578748.

- Goodlad, J. I. 1979. Curriculum Inquiry: The Study of Curriculum Practice. New York, USA: McGraw Hill.

- Goodlad, J. I. 1994. Educational Renewal: Better Teachers, Better Schools. San Francisco, CA, USA: Jossey-Bass.

- Graf, L., and A. P. Lohse. 2022. “Analyzing Vocational Education and Training Systems Through the Lens of Political Science.” In Internationales Handbuch der Berufsbildung. Vergleichende Berufsbildungsforschung–Ergebnisse Und Perspektiven Aus Theorie Und Empirie. Jubiläumsausgabe des Internationalen Handbuchs der Berufsbildung [Comparative Vocational Education Research–Results and Perspectives from Theory and Empirical Studies. Anniversary Edition of the International Handbook of Vocational Education and Training], 123–141. Bonn, Germany: Verlag Barbara Budrich.

- Hager, P. 2011. “Refurbishing MacIntyre’s Account of Practice.” Journal of Philosophy of Education 45 (3): 545–561. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9752.2011.00810.x.

- Halliburton, D. 1977. “Perspectives on the Curriculum.” In Developing the College Curriculum: A Handbook for Faculty and Administrators, edited by G. H. Quehl and M. Gee, 37–50, Washington, DC, USA: Council for the Advancement of Small Colleges.

- Harris, R., and S. Graham. 2019. “Engaging with Curriculum Reform: Insights from English History teachers’ Willingness to Support Curriculum Change.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 51 (1): 43–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2018.1513570.

- Hawick, L., J. Cleland, and S. Kitto. 2017. “Getting off the Carousel: Exploring the Wicked Problem of Curriculum Reform.” Perspectives on Medical Education 6 (5): 337–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-017-0371-z.

- Hoeve, A., A. Van Vlokhoven, and L. Nieuwenhuis. 2021. Het vizier op buiten: Leerplanontwikkeling voor een dynamisch beroep [Looking to the outside: Curriculum development for a dynamic profession]. NRO project 405-17-623. Arnhem/Nijmegen: HAN University of Applied Sciences. https://www.nro.nl/sites/nro/files/media-files/EindrapportageHetvizieropbuiten-leerplanontwikkelingvooreendynamischberoep.pdf.

- Kane, M., and W. M. K. Trochim. 2007. Concept Mapping for Planning and Evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Koeslag-Kreunen, M. G., M. R. Van der Klink, P. Van den Bossche, and W. H. Geijselaars. 2018. “Leadership for Team Learning: The Case of University Teacher Teams.” Higher Education 75 (2): 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0126-0.

- Könings, K. D., C. Bovill, and P. Woolner 2017. “Towards an Interdisciplinary Model of Practice for Participatory Building Design in Education.” European Journal of Education 52 (3): 306–317.

- Könings, K. D., S. Brand-Gruwel, and J. J. G. Van Merriënboer. 2007. “Teachers’ Perspectives on Innovations: Implications for Educational Design.” Teaching & Teacher Education 23 (6): 985–997. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.06.004.

- Lattuca, L. R., and J. S. Stark. 2009. Shaping the College Curriculum: Academic Plans in Context. San Francisco, CA, USA: John Wiley & Sons.

- Leeman, Y., N. Nieveen, F. de Beer, and J. Van der Steen. 2020. “Teachers as Curriculum-Makers: The Case of Citizenship Education in Dutch Schools.” The Curriculum Journal 31 (3): 495–516. https://doi.org/10.1002/curj.21.

- Leibowitz, B., S. van Schalkwyk, J. Ruiters, J. Farmer, and H. Adendorf. 2012. ““It’s Been a Wonderful life”: Accounts of the Interplay Between Structure and Agency by “Good” University Teachers.” Higher Education 63 (3): 353–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9445-8.

- Loumpourdi, M. 2021. “The Future of Employee Development in the Emerging Fourth Industrial Revolution: A Preferred Liberal Future.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2021.1998793.

- Marshall, S. J. 1998. “Professional Development and Quality in Higher Education in the Twenty-First Century.” Australian Journal of Education 42 (3): 321–333. https://doi.org/10.1177/000494419804200308.

- McGrath, S. 2022. “Vocational Education in the Fourth Industrial Revolution.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 74 (2): 352–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2021.2018227.

- McKenney, S., Y. Kali, L. Markauskaite, and J. Voogt. 2015. “Teacher Design Knowledge for Technology Enhanced Learning: An Ecological Framework for Investigating Assets and Needs.” Instructional Science 43 (2): 181–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-014-9337-2.

- Myatt, M., and J. Tomsett. 2022. Huh: Curriculum Conversations Between Subject and Senior Leaders. Melton, Woodbridge: John Catt Educational.

- Nieuwenhuis, L., H. Smulders, and R. Sessink. 2021. “Responsiviteit Als Opdracht [Responsiveness as a Mission.” In Handboek beroepsgerichte didactiek. Effectief opleiden in het mbo en hbo [Manual of vocational didactics. Effective training in MBO and HBO], edited by A. Hoeve, H. Van Vlokhoven, L. Nieuwenhuis, and P. Den Boer, 73–92. Huizen, The Netherlands: Pica.

- Nieveen, N., J. van den Akker, and F. Resink. 2010. “Framing and Supporting School-Based Curriculum Development in the Netherlands.” In Schools as Curriculum Agencies, 273–283. Brill.

- Nieveen, N., and M. van der Hoeven. 2011. Building the Curricular Capacity of Teachers: Insights from the Netherlands. Beginning Teachers: A Challenge for Educational Systems. Lyon, France: ENS de Lyon, Institut français de l’Éducation. CIDREE Yearbook 2011. https://www.cidree.org/fileadmin/files/pdf/publications/YB_11_Beginning_teachers.pdf

- OECD. (2014). Skills Beyond School: Synthesis report. OECD Reviews of Vocational Education and Training. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/edu/skills-beyond-school/Skills-Beyond-School- Synthesis-Report.pdf

- Pieters, J., J. Voogt, and N. Pareja Roblin. 2019. Collaborative Curriculum Design for Sustainable Innovation and Teacher Learning. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Priestley, M., G. J. J. Biesta, and S. Robinson. 2012. “Teachers as Agents of Change: An Exploration of the Concept of Teacher Agency.” Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC). https://www.stir.ac.uk/research/hub/publication/764037

- Raffe, D. 2013. “Challenges and Reforms in Vocational Education: Aspects of Inclusion and Exclusion.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 65 (2): 303–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2013.780330.

- Rosas, S. R., and M. Kane. 2012. “Quality and Rigor of the Concept Mapping Methodology: A Pooled Study Analysis.” Evaluation and Program Planning 35 (2): 236–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.10.003.

- Rusert, K., and M. Stein. 2023. “Chances and Discrimination in Dual Vocational Training of Refugees and Immigrants in Germany.” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 75 (1): 109–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2022.2148118.

- Schein, E. 1992. Organizational Culture and Leadership. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA, USA: Jossey-Bass.

- Shalem, Y., and S. Allais. 2018. “When is Vocational Knowledge Educationally Valuable?” In Knowledge, Curriculum and Preparation for Work, edited by S. Allais and Y. Shalem, 13–29, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill/Sense.

- Thijs, A., and J. Van den Akker, edited by 2009. Leerplan in Ontwikkeling [Curriculum in Development]. Enschede: SLO.

- Viennet, R., and B. Pont 2017. Education Policy Implementation: A Literature Review and Proposed Framework. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 162. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/fc467a64-en

- Vreuls, J., M. Koeslag-Kreunen, M. van der Klink, L. Nieuwenhuis, and H. Boshuizen. 2022. “Responsive Curriculum Development for Professional Education: Different Teams, Different Tales.” The Curriculum Journal 0 (4): 636–659. https://doi.org/10.1002/curj.155.

- Waterman, R. H., and T. J. Peters. 1982. In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best-Run Companies. New York, USA: Harper & Row.

- Wheelahan, L. 2007. “How Competency-Based Training Locks the Working Class Out of Powerful Knowledge: A Modified Bernsteinian Analysis.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 28 (5): 637–651. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690701505540.

- Whitehead, C. R., B. D. Hodges, and Z. Austin. 2013. “Captive on a Carousel: Discourses of ‘New’ in Medical Education 1910–2010.” Advances in Health Sciences Education 18 (4): 755–768. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-012-9414-8.

- Young, M. 2006. “Conceptualising Vocational Knowledge: Some Theoretical Considerations.” In Knowledge, Curriculum and Qualifications for South African Further Education, edited by M. Young and J. Gamble, 104–124, Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC Press.

- Young, M., and J. Hordern. 2022. “Does the Vocational Curriculum Have a Future?” Journal of Vocational Education & Training 74 (1): 68–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2020.1833078.