ABSTRACT

In Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) programmes, non-linguistic content is taught and assessed in an additional language. Hence, CLIL teachers, most of whom are content subject specialists, may encounter difficulties in evaluating students’ content knowledge independent of their L2 proficiency and in aligning objectives, instruction and assessment. These concerns are closely related to teachers’ assessment literacy, which is seen as integral to teachers’ pedagogical content knowledge and plays a crucial role in effective instruction and assessment. While frameworks for teachers’ assessment literacy exist, there have been calls to re-examine this important construct with reference to specific disciplinary contexts. Given the curricular complexities of CLIL, this paper seeks to conceptualise the assessment literacy of teachers in such programmes. It will first tease out the complexities of assessment in CLIL programmes. It will then review some relevant literature on teachers’ assessment literacy, based on which a conceptual framework for CLIL teachers’ assessment literacy is proposed. It will also include an illustrative case of how the framework could be applied in research. The framework will establish a theoretical grounding for future empirical research in the field and have important implications for CLIL teacher education.

1. Introduction

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) can be broadly defined as ‘any type of pedagogical approach that integrates the teaching and learning of content and second/foreign languages’ (Morton and Llinares Citation2017, 1). With this broad definition, CLIL can be used as an umbrella term for an array of educational programmes and instructional approaches, including immersion and English-medium education (EMI), though researchers need to acknowledge the variation in sociolinguistic contexts, objectives, and teacher and student profiles among programmes (Cenoz, Genesee, and Gorter Citation2014). On the assumption that learning non-linguistic content subjects can facilitate additional language (L2) learning (Morton and Llinares Citation2017), CLIL programmes have been adopted in different world locations, including Asia and Europe, where language majority students in school settings are expected to develop the target L2 (e.g. English) through use in subject teaching-learning activities (e.g. Science). The worldwide spread of CLIL has resulted in a high demand for CLIL teachers. Recent literature has proposed some essential qualities and knowledge of CLIL teachers, including understanding of the theoretical underpinnings of CLIL, knowledge about teaching language, content and their integration, as well as lesson planning and pedagogy (Morton Citation2016). Such discussion about the expertise of CLIL teachers has so far focused on pedagogy, without paying too much attention to assessment. Assessment, particularly formative assessment, plays an important role in effective teaching and learning, as it can provide evidence of students’ achievement and provides feedback to inform instruction and learning (Leung Citation2014). However, how to design assessments in CLIL is a complicated issue and the existing paucity of research reflects that there is a lack of training or guidance for CLIL teachers (Otto and Estrada Citation2019). This paper sets out to address this research gap by investigating in the CLIL context the construct of ‘teachers’ assessment literacy’, which is defined as teachers’ knowledge and skills in evaluating and supporting student learning through assessment (DeLuca, LaPointe-McEwan, and Luhanga Citation2016). By exploring and conceptualising the components of CLIL teachers’ assessment literacy, this paper aims at providing a theoretical framework for future research on CLIL assessment with significant implications for CLIL teacher education.

2. Complexities of assessments in CLIL

The fact that CLIL students’ content knowledge is assessed in the target L2 gives rise to several issues regarding validity and fairness. In terms of validity, CLIL teachers are expected to design appropriate forms of assessment that can diagnose students’ learning in content and L2, both of which are the learning targets of CLIL. Yet, this is not easy as content and language are inseparable and it is extremely difficult to tease out students’ performance as two distinguishable aspects of performance (Otto and Estrada Citation2019). Also, as aforementioned, CLIL encompasses a variety of programmes, some of which are more content-oriented (e.g. immersion and EMI) and some are more language-oriented (e.g. content-based language instruction). Hence, the relative emphasis on assessing content and language, and how to assess the two aspects, are challenging for teachers in different CLIL programmes (Leontjev and deBoer Citation2020a). In terms of fairness, as assessments should, in theory, be similar for both CLIL and non-CLIL students, teachers should ensure that CLIL students are not disadvantaged on content because of the language of instruction and assessment (Brinton, Snow, and Wesche Citation2003). This is not easy either, since students may find it difficult to understand the assessment questions and demonstrate their content knowledge or higher-order thinking skills in their less-proficient L2 (Lo and Fung Citation2020). In this sense, CLIL assessments are likely to underestimate students’ learning, thereby being unfair.

Indeed, these validity and fairness issues have been widely discussed in other contexts where the content knowledge of English Language Learners (ELLs) and immigrant students is assessed in their L2, which is the default medium of instruction in mainstream education (Shohamy Citation2011). These studies have shown underestimation of the academic achievement of ELLs and immigrant students due to the language barrier (Attar, Blom, and Le Pichon Citation2020), and have indicated that some accommodations (e.g. providing bilingual versions of the assessment, simplifying language features of questions) would enhance those students’ performance (Abedi and Lord Citation2001). Some researchers have also proposed to allow bi/multilingual students to utilise all their linguistic resources (e.g. through translanguaging practices) in assessment so that they can manifest their actual content knowledge (Gorter and Cenoz Citation2017). These issues are equally applicable to CLIL learners, whose content knowledge is also assessed in a language that they are concurrently acquiring as an L2. Yet, it has been only recently that researchers have begun to scrutinise assessments in CLIL. There are several major directions of research in this aspect.

First, some researchers have proposed frameworks for designing assessment tasks and assessment rubrics in CLIL. Massler, Stotz, and Queisser (Citation2014) proposed a CLIL assessment framework comprising the dimensions of subject-specific themes (i.e. content knowledge), subject-specific skills and competencies (i.e. cognitive skills) and foreign language communicative competencies. They demonstrated how such a framework could be used to design and describe some assessment tasks in European CLIL programmes. In a similar vein, Lo and Fung (Citation2020) proposed a matrix comprising the dimensions of cognitive skills, receptive language skills and productive language skills, each of which consists of 3–4 levels. The framework allows a fine-grained analysis of what assessment tasks/questions require students to do. Quartapelle (Citation2012) exemplified how different types of assessment rubrics (e.g. holistic rubrics, analytic rubrics) could be used to assess students’ integrated content and language learning, or their respective performance in content and language dimensions, while Shaw (Citation2020) proposed a Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR)-referenced rating scale for academic language proficiency in History. This scale details what students can do with language in different aspects (e.g. text processing, reading, writing) at different History levels.

Second, some studies have sought to explore the mediating role of language in students’ performance in CLIL assessments. Lo, Fung, and Qiu (Citation2021) analysed the relationship between students’ performance and the cognitive and linguistic demands of questions in Biology public examination in Hong Kong. This study compared the potential impact of the language of testing on the performance of students who took the examination in L2 (English) and first language (L1; Chinese). They found that linguistic demands, especially productive linguistic demands (e.g. responding to test items in written sentences and passages), had significantly depressed the performance of students taking the test in their L2. These results imply that students whose content knowledge is assessed in their L2 may be disadvantaged.

These studies have focused more on students’ learning outcomes at a particular point in time for such purposes as grading and selection. These can be regarded as assessment of learning, which is often juxtaposed with assessment for learning, which aims to collect data about student learning to inform teaching and learning (Shepard Citation2019). Some recent research attention has been put into assessment for learning and classroom-based assessment in CLIL so as to explicate the relationship between teaching, learning and assessment in CLIL (Leontjev and deBoer Citation2020a). Xavier (Citation2020) presented some authentic examples of how teachers incorporated classroom-based assessment tasks (e.g. peer assessment tasks) in primary CLIL settings. She underscored the importance of engaging students in the assessment processes, and of providing feedback to support learning. With an in-depth analysis of the classroom interaction episodes between one teacher and student in a CLIL classroom in Finland, Leontjev, Jakonen, and Skinnari (Citation2020) demonstrated how the teacher could assess the student’s learning in both content and language, and support the student’s learning through asking different types of questions (e.g. yes/no, why questions).

Fourth, some studies have examined CLIL teachers’ perceptions and practices of assessment. Most CLIL teachers find it ‘extremely difficult to assess content knowledge without taking proficiency into account’ (Otto and Estrada Citation2019, 33). Although most CLIL teachers put more emphasis on content when designing assessment tasks and marking rubrics, they also recognise the role played by students’ L2 proficiency in affecting the overall grade awarded (Hönig Citation2010; Otto and Estrada Citation2019). CLIL teachers also encounter difficulty when selecting appropriate assessment tools for CLIL students. In some contexts, given concerns over fairness, CLIL teachers adopt assessment tools based on those designed for non-CLIL students (usually written tests consisting of essay questions), even though they are aware that other assessment tools (e.g. oral presentations) may better capture student learning in CLIL (Otto and Estrada Citation2019). These studies reveal the inconsistencies between teachers’ perceptions and practices when assessing CLIL students, and their concerns when designing CLIL assessments. These all relate to the fundamental construct of teachers’ assessment literacy, which is the focus of this paper.

3. Teachers’ assessment literacy

Assessment literacy is defined as the knowledge of educational assessment and the skills to apply such knowledge to measure student achievement (Xu and Brown Citation2016). It is an integral part of teacher professional knowledge (Abell and Siegel Citation2011). Since the term was coined in the early 1990s, repeated attempts have been made to elaborate the list of skills and competencies that assessment-literate teachers should possess. These include skills in:

choosing and developing assessment methods appropriate for instructional decisions;

administering, scoring and interpreting assessment results;

using assessment results to inform instruction;

communicating assessment results to stakeholders;

cultivating fair assessment conditions for all students;

understanding ethical issues related to assessment; and

understanding psychometric properties of assessment (DeLuca, LaPointe-McEwan, and Luhanga Citation2016; Stiggins Citation1995).

While the existing conceptual frameworks and studies outline the core competencies for teachers to be assessment literate in general, additional competencies are deemed to be necessary for CLIL teachers, since assessment literacy should be situated and contextualised (Xu and Brown Citation2016). That may explain why there have been attempts to conceptualise the assessment literacy for teachers of different disciplines, including Science teachers (Abell and Siegel Citation2011) and language teachers (Levi and Inbar-Lourie Citation2020). In particular, Levi and Inbar-Lourie (Citation2020) analysed the assessment tasks designed by a group of language teachers during a professional development course on generic formative classroom assessment. They observed that the assessment literacy of those language teachers as reflected in their assessment tasks was ‘an amalgamation of different skills: the generic, the language-specific and the contextual’ (179). Following the same argument for discipline-specific assessment literacy, this paper seeks to conceptualise the assessment literacy of CLIL teachers, who shoulder dual responsibilities of content and language teaching. Bearing such dual responsibilities does not mean that CLIL teachers’ assessment literacy is simply the sum of assessment literacy in content subject and language. It is how the two can be integrated according to the classroom and educational contexts. We hope such complexities could be captured with our conceptual framework, which will be illustrated next.

4. Conceptual framework for CLIL teachers’ assessment literacy

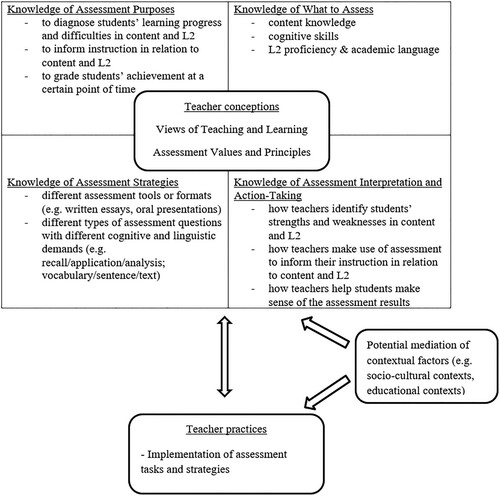

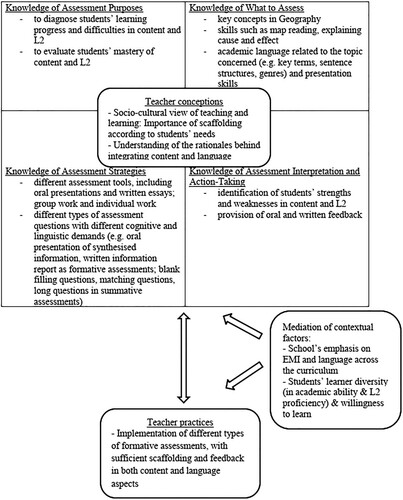

Based on previous literature on CLIL assessments and teachers’ assessment literacy (Abell and Siegel Citation2011; Lam Citation2019; Xu and Brown Citation2016), a conceptual framework capturing CLIL teachers’ assessment literacy is proposed in . The components will be elaborated below, followed by an illustrative case in the next section.

(i) Teacher conceptions: A fundamental component of teachers’ assessment literacy is their views of teaching and learning, as well as their perceived values and principles of assessment (Abell and Siegel Citation2011). Teachers’ beliefs about how students learn will affect how they view and design assessments (Leung Citation2014). When the behaviourist theory of learning was dominant between 1950s and 1970s, learning was believed to be a process of imitation, reinforcement or immediate correction and then habit formation. Hence, teaching at that time was mainly teacher-centred and focused on content delivery, whereas assessment was dominated by timed, learning-sequence-end tests which aim at measuring the knowledge and skills students have memorised (James Citation2008). These views of learning and assessment practices are still affecting teachers in many contexts (Levi and Inbar-Lourie Citation2020), but other possible views have emerged. Since 1980s, cognitive constructivist views of learning have become more popular. In this perspective, learning involves learners’ thinking, meaning-making and knowledge construction processes. Hence, assessment practices focus on students’ understanding of concepts and problem solving, and the formats are no longer restricted to ‘tests’, but ‘tasks’ such as essays, open-ended assignments and projects. Another contemporary view of learning is socioculturally oriented, which argues that all kinds of learning take place through social interaction, during which more able peers (e.g. teachers) mediate the environment for learners and provide scaffolding to facilitate learning (Mercer and Howe Citation2012). Following this view of learning, assessment is seen as a useful means to gather evidence about student learning process and outcomes for teachers to adapt their instruction and for students to improve their learning (Shepard Citation2019).

In the context of CLIL, we would argue that in addition to the general theories of learning and principles of assessment, the component of teacher conceptions should also include teachers’ perceptions of what CLIL is and their views on how content and language are learned. This is an important aspect, as previous research (e.g. Skinnari and Bovellan Citation2016) has shown that CLIL teachers, especially those who have been trained as content specialists, often see themselves as content teachers only, and they do not think it is their responsibility to teach language. They may not understand the theoretical underpinnings behind content and language integration, or adopt pedagogical strategies of integrating the two dimensions during teaching (Cammarata and Haley Citation2018). In particular, content specialists are heavily influenced by the cognitive constructivist view of learning and tend to focus on students’ development of conceptual understanding and cognitive skills during assessment (James Citation2008). On the other hand, contemporary views of language learning underscore the role of language in shaping meaning-making, identity construction and social interaction (Levi and Inbar-Lourie Citation2020). It is hence important to examine how CLIL teachers may reconcile the different views of learning in different disciplines and translate such reconciled views into their instruction and assessment practices. Regarding the values and principles of assessments, the issues concerning validity and fairness deserve teachers’ attention in CLIL programmes, owing to the inseparable nature of content and language (see the discussion in Section 2). These should also form the basis of CLIL teachers’ assessment literacy.

(ii) Knowledge of assessment purposes: Assessment can serve different purposes in education. In the past, teachers tended to focus on assessment of learning (or summative assessment), which aims to measure students’ achievement at a certain point of time, so that teachers could make judgement about students’ learning. While teachers still do assessment of learning (e.g. end of term examinations, high-stakes public examinations), there have been consistent calls for more attention to assessment for learning (or formative assessment), which aim to understand students’ learning progress, strengths and difficulties so that teachers could adjust their instruction and provide feedback to further promote students’ learning (Shepard Citation2019). These different types of assessments with their different purposes are also applicable to CLIL assessments. However, considering the nature and dual goal of CLIL programmes, teachers should be aware of both content and language dimensions when they consider the purposes of assessment. In particular, when implementing assessment of learning, teachers aim at measuring students’ mastery of content knowledge and (academic) language at a certain point of time; when implementing assessment for learning, teachers seek to diagnose students’ learning progress and difficulties in both content and language learning, and the evidence gathered will inform instruction in relation to content and language. For instance, Leontjev and deBoer (Citation2020b) demonstrated how CLIL teachers should understand both students’ learning process (e.g. their co-construction of content knowledge and academic language through their group discussion in class and on discussion forum) and students’ product (e.g. their PowerPoint presentation on the topic and their script), so as to gain a more comprehensive picture of students’ current learning progress, how it has developed and how it can be further extended.

(iii) Knowledge of what to assess: Theoretically speaking, both content and language should be assessed, as they are the dual goal in CLIL programmes. In real practice, the relative emphasis on content and language in assessments depends on the nature of the CLIL programme in question (Otto Citation2018). For example, in CLIL programmes where content specialists are responsible for implementing CLIL, the content curriculum often guides the parameters for assessment (Hönig Citation2010). However, in the conceptual framework of CLIL teachers’ assessment literacy, teachers need to be aware of the inseparable relationship between content and language in assessments, irrespective of the CLIL contexts they are in. For more content-oriented CLIL, teachers may put more emphasis on assessing students’ content knowledge and cognitive skills, but they should not ignore the role of language in mediating students’ ability to express their knowledge and skills. Snow, Met, and Genesee’s (Citation1989) notions of ‘content obligatory’ and ‘content compatible’ language are relevant here. ‘Content obligatory’ language refers to the language required for learning the subject content (usually the subject-specific vocabulary of a particular topic), whereas ‘content compatible’ language is language that can be incorporated in content subject lessons (e.g. grammar items, sentence patterns, typical genres). These two registers of content-related language are largely echoed by Coyle, Hood, and Marsh’s (Citation2010) language of learning (language needed to access key concepts and skills relating to a particular topic) and language through learning (language that emerges when students are actively involved in developing new knowledge and thinking skills), with the addition of language for learning, which is the language needed to participate in CLIL lessons. Teachers may target at content obligatory language (or language of learning) in assessments in content-oriented CLIL since it is essential for student learning of content, but at the same time, they should make sure content obligatory language (or language through learning) does not interfere with students’ ability to express their knowledge and skills. For more language-oriented CLIL, teachers may be more interested in assessing students’ L2 proficiency, but they should not overlook the meaningful contexts provided by ‘content’, and their assessment focus should be different from more traditional foreign language classrooms where accuracy is paramount. Instead, the assessment focus should be on whether students could use appropriate language resources to express their meaning in relation to particular content topics (Otto Citation2018).

(iv) Knowledge of assessment strategies: This component concerns the question ‘how to access?’. Part of this is related to assessment formats, which may include written tests, portfolios, oral presentations, teachers’ observation, students’ self-evaluation and manipulatives. Having a variety of assessment formats is important for CLIL students, since some of them may encounter language barriers when expressing their content knowledge in their L2. Some researchers also advocate better use of multimodal resources (Leontjev and deBoer Citation2020b) and different languages (Gorter and Cenoz Citation2017) when assessing students’ content knowledge. However, this is not yet a common practice in CLIL assessments, which are still dominated by written tests (e.g. structured questions, essay questions) (Otto and Estrada Citation2019). CLIL teachers need to be aware of different assessment formats and tools, and employ different tools to better diagnose students’ learning progress in both content and language dimensions.

Apart from the varied assessment formats, teachers should also include questions with different levels of cognitive and linguistic demands. The rationale is to have a better picture of students’ learning progress in content and language. If all questions are cognitively and linguistically challenging, when students fail to answer the questions, it is hard for teachers to know whether students have problems with content, cognitive skills, language or a combination of all (Coyle, Hood, and Marsh Citation2010). The conceptual frameworks for designing CLIL assessments reviewed above (e.g. Lo and Fung Citation2020; Massler, Stotz, and Queisser Citation2014) may provide useful reference tools for teachers to design questions of varied levels in different dimensions.

(v) Knowledge of assessment interpretation and action-taking: For assessment to provide feedback for teaching and learning, it is essential for teachers to know how to interpret the data collected through assessments and take follow-up actions. Data interpretation typically involves identifying students’ strengths and weaknesses. Based on such interpretation, teachers can decide what to do in the next learning-teaching-assessment cycle to help students improve their learning (Shepard Citation2019). In recent years, assessment as learning has been advocated. This type of assessment can be regarded as a sub-group of assessment for learning, but its focus lies on helping students to become their own assessors and independent learners (Earl Citation2003). In line with such a trend, in addition to adjusting their instruction, teachers could help students make sense of the assessment results and decide which areas they need to improve and how they can do so. In CLIL contexts, it is important for teachers to diagnose students’ learning progress in both content and L2 dimensions. Morton (Citation2020) suggested how teachers could analyse students’ work (e.g. short essays) to diagnose their learning progress in both content knowledge and language, and then decide on the follow-up instruction. For example, it was observed that students did not know how to write formal definitions or comparisons. Teachers could then think about some instructional activities (e.g. asking students to comment on some examples of definitions and comparisons) to help students write definitions and comparisons with appropriate language.

(vi) Teacher practices and mediation of contextual factors: Teachers’ conceptions and knowledge can be broadly referred to teachers’ cognition, which is closely related to teachers’ practices (Borg Citation2003). However, such a relationship is not straightforward, in the sense that teachers’ cognition may not be directly translated into teachers’ real practices, because their practices are also affected by other factors such as contextual factors (e.g. the socio-cultural contexts, school culture and policies, types of students). Leung’s (Citation2009) notions of ‘sponsored professionalism’ and ‘independent professionalism’ of teachers may further explicate such a relationship. ‘Sponsored professionalism’ is the kind and level of disciplinary knowledge, skills and practical experience teachers are expected to have, as endorsed by the public and professional bodies in their educational contexts. At the same time, teachers are engaged in critical examination of such assumptions and rountised practices with reference to their disciplinary knowledge, views and beliefs as well as the wider social values. These teachers, who are informed by a sense of ‘independent professionalism’, will then modify their practices so that they are aligned with teachers’ beliefs and values in their own contexts (e.g. particular classrooms and schools). The navigation between the two types of professionalism can then explain the complicated relationship between teachers’ conceptions and knowledge of assessment, real practices and contextual factors. For example, in Otto and Estrada’s (Citation2019) study, the teachers were aware of the need to diversify their assessment strategies, so as to alleviate the potential language barriers faced by CLIL students. However, they still employed written essays as the main assessment tool, because they also considered fair comparison between CLIL and non-CLIL students. This then serves as an example to illustrate the mediating effect of contextual factors on the mismatch between teachers’ conceptions and practices. The presence of ‘mediation of contextual factors’ in the framework can enhance the generalisability or applicability of the framework to different variants of CLIL programmes. For example, in programmes which are more content-oriented, content learning outcomes are usually prioritised in the curriculum and high-stakes examination. This may in turn affect teachers’ conceptions of assessment purposes, content and strategies, and their assessment practices; in programmes which put explicit emphasis on language learning goals, teachers may pay more attention to assessing students’ language development in different aspects (e.g. reading, writing, listening and speaking), and their assessment strategies and practices are different from teachers in more content-oriented programmes.

5. Illustration of the application of the framework

To illustrate how the conceptual framework of CLIL teachers’ assessment literacy can be applied in research, this section presents a brief analysis of one teacher’s assessment literacy. The data of this teacher came from a larger-scale projectFootnote1, which aimed to investigate the assessment practices in CLIL. Contextualised in Hong Kong, where the label of EMI is more commonly used, one key stage of the project was to conduct multiple case studies to understand the alignment of objectives, instruction and assessment practices of EMI teachers in Hong Kong. In this stage, 12 teachers teaching Biology or Geography in English (students’ L2) were recruited as cases, and from each case, different sources of data were collected so as to get a comprehensive understanding of the teacher’s beliefs and practices. In this section, the conceptual framework is applied to understand the assessment literacy of a teacher, Miss T, who was an experienced Geography teacher in a secondary school in Hong Kong. The school is a girls’ school and the students’ academic ability, according to Miss T, was average, with the majority of students being categorised as band 2 (the middle tier of the three-tier categorisation system of primary school leavers). However, Miss T mentioned that some diversity in terms of academic ability and English proficiency could be observed among the same cohort of students. The school used to be Chinese-medium (teachers’ and students’ L1) for all content subjects, but since 2010/11, two content subjects, Integrated Science and Geography, were taught through English. This resembles the practice of CLIL in some European countries, where part of the school curriculum is taught through the target language (Goris, Denessen, and Verhoeven Citation2013). As will be further illustrated under the section of ‘contextual factors’, the school where Miss T was working attempted to enhance the effectiveness of EMI teaching through promoting language across the curriculum and encouraging content subject teachers to incorporate more language scaffolding into their lessons. Miss T herself had attended different workshops offered by the Education Bureau and universities on teaching content subjects through English, and had participated in projects on designing teaching materials to integrate content and language teaching. These may have affected her beliefs about the relationship between content and language. These will be illustrated with the framework below.

Regarding the data collected from this case, the research team observed Miss T’s four lessons in the unit ‘Problems in the Oceans’ in Grade 9 (aged 14–15). This group of students should have at least 9 years of learning English as an additional language (since Grade 1) and almost three years of learning content subjects through English (since Grade 7). Their English level could be regarded as intermediate. By the end of the unit, students were expected to understand the causes and effects of some of the problems, including overfishing, marine pollution and problems related to reclamation. Students were guided to read for information of these problems and describe these problems through an oral presentation and an information report. During lesson observations, the research team jotted notes on Miss T’s in-class instructional and assessment practices. The lessons were also recorded for more detailed analysis. When the observed teaching unit was completed, some sample work from students was gathered. Students’ performance and the teacher’s marking practices as reflected in the sample work were analysed. Lastly, semi-structured interviews were conducted with Miss T to gather her perceptions of EMI teaching and learning, classroom practices and assessments. As the aim of the project was not primarily on teachers’ assessment literacy, not all the components of the conceptual framework could find sufficient data. In what follows, we try to briefly illustrate what the research team could observe in each component.

5.1. Teacher conceptions

Miss T’s conceptions of teaching, learning and assessment could be inferred from what she said about her teaching and assessment practices. Miss T seemed to understand the rationales behind learning content subjects through English and she was receptive of her responsibilities for teaching content and language. Regarding her school’s decision to start teaching some content subjects through English since 2010/11, she commented,

Whether students should learn Geography through Chinese or English, I think there are both pros and cons. Of course, if we are to follow the school’s policy, EMI, then the richer the language environment, the better. It would be better if more content subjects could follow this.

In the lesson I will highlight the question words so that students know what they need to answer … After that, I will teach them the structure of the essay. For example, this is paragraph one, paragraph two, and then the whole framework. I will also teach them how to build-up an introduction … sentence structures … and how to use connectives to connect their ideas.

5.2. Knowledge of assessment purposes

It is evident that Miss T understood different types of assessment (formative vs summative assessments) and their purposes. During the interview, Miss T described how and why she designed different assessment tasks. For example, in the unit observed by the research team, there were two assignments, a group oral presentation on the ocean problems students identified from some given news articles and an individual written essay (an information report on ocean problems). Miss T described the oral presentation as a ‘warm up’ for the written essay. Students’ performance would not be ‘assessed with scores’ and she provided immediate feedback after students’ presentations (e.g. the richness of the content and the language used), so that they knew how to improve their work when they wrote the information report. For the written essay, Miss T would also provide feedback, particularly positive reinforcement, ‘I will highlight good use of connectives and sentences with some symbols … for content, I will write 2–3 points to appreciate their rich content.’ To Miss T, the purpose of these assignments was to provide feedback for students, so that ‘students would be more confident’. Hence, these assignments aligned with the purpose of formative assessments. When it comes to end-of-unit quizzes, term tests and examinations, Miss T was aware that these aimed at evaluating students’ learning outcomes, especially in terms of the content knowledge and subject-specific language.

5.3. Knowledge of what to assess

Similar to other content subject teachers, Miss T agreed that ‘it is normal for content subject teachers to focus on students’ concepts. If students’ ideas or concepts are not clear, how can they express them (with language)?’ Yet, being a language-aware content teacher, Miss T also demonstrated her understanding of the role played by language in content subject assessments, as she commented,

Regarding the role of language in content assessment, I think it is different between junior and senior secondary … For S.1 (Grade 7) students, if they can master the key terms, I am satisfied. For S.2 (Grade 8) students, if they can write the key terms and phrases, they have shown some improvement. It would be even better if they could talk about cause–effect relationship …

For example, if it is a question about map reading and I ask the students to draw a cross-section, I am evaluating their application ability … this will not involve too much language … but when it comes to long questions, they will involve grammar and writing skills.

5.4. Knowledge of assessment strategies

As aforementioned, Miss T included different assessment formats, including an oral presentation and a written essay in the unit observed by the research team. She also allowed students to work in groups before they completed the essay on their own. When she designed written assessments (e.g. unit quizzes or tests), Miss T was conscious of including different types of questions. She reported,

If we don’t want to scare the students, we will include more fill in the blanks or matching questions. Then there will be a long question, which usually accounts for 8–10 marks. It will impose more language demands on students.

5.5. Knowledge of assessment interpretation and action-taking

Miss T believed in the importance of providing feedback for the students, especially positive feedback. She would give feedback on both content and language after students have finished their assessment tasks (e.g. oral presentations and written essays). In addition to the feedback practices reported previously, Miss T mentioned, ‘Sometimes if time allows, I will show students’ work with a visualiser in the lesson and then we can analyse why this essay is good.’ Hence, it can be seen that Miss T could identify students’ strengths in both content and language. She would also identify students’ weaknesses. For example, during the interview, Miss T shared some sample work with the researcher, and she pointed out that some students missed some key points in the essay, while others failed to write the conclusion. However, as she emphasised several times in the interview, she paid more attention to appreciate students’ strengths in class so as to give them more confidence. It was not very clear whether she would take follow-up actions regarding students’ weaknesses. But she did mention how she kept modifying her teaching materials (e.g. the provision of support) according to her experience of using those materials.

5.6. Teacher practices

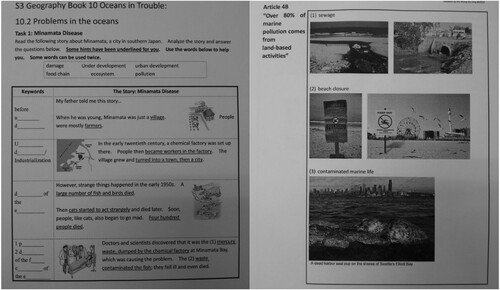

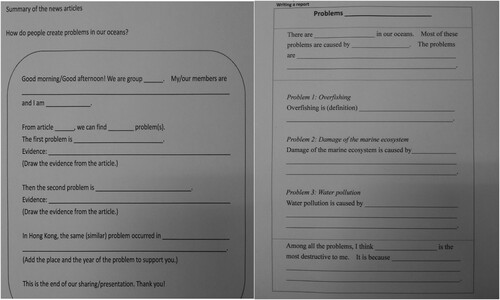

From the lesson observations, Miss T’s conceptions and knowledge of CLIL assessments were translated into her practices to a large extent. For example, to prepare students for the oral presentation and written information report, Miss T designed materials which incorporated sufficient language support. Before the oral presentation, students were given a group reading task with clear written instructions. Visual support (i.e. pictures) together with the verbal equivalents (i.e. subject-specific words/phrases) were abundant in the reading materials, whereas choices of vocabulary or first letters were given for fill-in-the-blank questions (see ). Templates which outlined the format of an oral presentation and an information report were also provided to the students (see ).

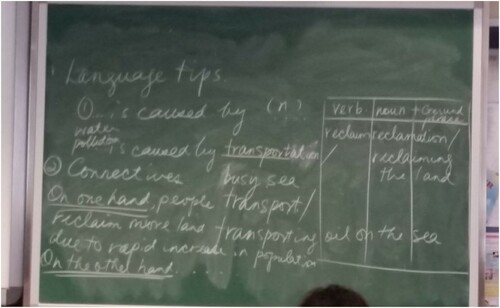

In the observed lessons, Miss T further explained the guidelines and requirements of the assessment tasks. For example, before students wrote the written report, Miss T highlighted the structure of the report and some ‘language tips’, such as connectives and verb phrases indicating cause–effect and contrast (see ). Based on students’ oral presentations in class and the collected samples of written work, these scaffolding activities enabled students to complete the assessment tasks by themselves, thereby working with content knowledge and language simultaneously.

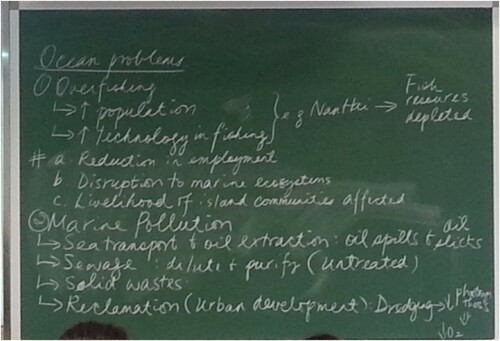

Miss T emphasised feedback provision in the interview, and this is also reflected in her practices. After students presented their ideas, Miss T reorganised the content knowledge together with students on the blackboard (see ), so that students’ ideas were presented in a more logical way. Miss T also assisted students with the correct pronunciation of certain subject-specific words (e.g. ‘contaminated’, ‘sewage’, ‘pesticide’), and commented on their oral presentation skills (e.g. eye contact, gesture, voice projection).

Figure 5. Organised content of students’ oral presentation, co-constructed by Miss T and the students.

In the written information reports, Miss T provided feedback on both content and language. For example, she would appreciate students’ attempt to provide ‘detailed explanation of the ocean problems’ and would suggest that ‘cause-and-effect of the problems should be closely linked’; in terms of language, Miss T would mark some lexico-grammatical errors on students’ reports and highlight some key language issues in the written feedback (e.g. ‘mind the sentence structures’). The Appendix includes two students’ written reports, with Miss T’s marking and comments on both content and language.

Owing to the time of data collection, the research team could only observe Miss T’s formative assessments but not the summative ones. Hence, there is no evidence regarding to what extent Miss T’s knowledge was reflected in other types of assessment.

5.6. Contextual factors

The discussion above shows that Miss T’s beliefs and practices of assessments were largely aligned. Some contextual factors have been identified and these may enable Miss T to translate her conceptions and knowledge to her practice. First, since the school started teaching the subjects Integrated Science and Geography in English in 2010/11, it has encouraged teachers to help students learn English more effectively. One way to do so is to promote language across the curriculum, which encourages content subject teachers to incorporate more language scaffolding into their teaching. With the view of enhancing students’ language proficiency and awareness, according to Miss T,

The school has formulated some guidelines or a blueprint regarding assessment design. According to these guidelines, there should be a progressive increase in the proportion of long questions in tests or examinations. If I remember correctly, the long question will take 30 marks for S.1 (Grade 7) and it will increase gradually.

The second contextual factor is related to the students. The lessons and students observed on the project were in junior forms, and hence Miss T did not ‘have the pressure from the public examination’, which is taken by Grade 12 students. Although there existed learner diversity, Miss T commented that the students were generally ‘good and willing to try’, and they were not particularly afraid of language. With cooperative students who were responsive to her assessment and instructional practices, Miss T could implement what she believed in.

summarises Miss T’s assessment literacy according to the proposed conceptual framework. Situated in the centre of the framework is Miss T’s socio-cultural view of teaching and learning, as well as her understanding of the rationale behind integrating content and language learning. Such conceptions in turn shape her knowledge of assessment in different aspects, particularly her attention paid to both content and language, instead of focusing on content only. As she was teaching in a school which also aimed to enhance the effectiveness of EMI through incorporating more language scaffolding into content subject lessons, Miss T was able to put her beliefs and knowledge into her assessment practices. We would argue that Miss T possessed a high level of assessment literacy in CLIL, since she was aware of the learning outcomes (which include both content and language outcomes) and aligned her assessment practices with such learning outcomes (Leontjev and deBoer Citation2020a). Perhaps what is missing (or what the research team could not observe during data collection) is Miss T’s practices of summative assessments and her follow-up actions after interpreting assessment results.

6. Conclusions

Teachers’ assessment literacy is crucial for effective educational assessment. Several studies have listed the competencies that assessment-literate teachers need to possess (Stiggins Citation1995) and proposed frameworks to conceptualise teachers’ assessment literacy (Xu and Brown Citation2016). However, these frameworks have been found too general to capture specific competencies required by teachers of different disciplines, leading to calls for discipline-specific conceptualisation of teachers’ assessment literacy (Levi and Inbar-Lourie Citation2020). This is what this paper sets out to achieve for teachers in CLIL programmes, most of whom are content subject specialists. Since students’ content knowledge is assessed in their usually less-proficient L2, it is reasonable to expect that CLIL teachers should possess some specific knowledge of what to assess, how to assess it, and how to interpret the assessment data to inform their teaching. By proposing a framework conceptualising what CLIL teachers’ assessment literacy entails, this paper offers a conceptual advance in CLIL assessment research and lays a theoretically informed foundation for further empirical studies in the field. With an illustrative case, this paper has demonstrated how the framework could be applied to analyse the assessment literacy of CLIL teachers and factors affecting such literacy. We acknowledge that further empirical research is needed to validate the conceptual framework. For example, the assessment literacy of different teachers could be analysed and compared with the framework, so as to identify teachers’ knowledge of assessment in different aspects (e.g. assessment content, purpose, strategies), how such knowledge affects their assessment practices and whether these are aligned with the learning outcomes of the CLIL programmes in their educational contexts; teachers working in different CLIL programmes and contexts could also be examined to reveal the applicability and compatibility of this framework. We believe this conceptual framework could serve as a diagnostic tool for teachers’ on-going professional development and reflective practices. These will in turn facilitate CLIL teacher education, especially concerning how teachers can design valid assessments that reflect the underlying principles of CLIL programmes and that are fair for all learners regardless of language proficiency.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yuen Yi Lo

Yuen Yi Lo is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Education of the University of Hong Kong. Her research interests include Medium of Instruction policy, Content and Language Integrated Learning, language across the curriculum and assessment.

Constant Leung

Constant Leung is Professor of Educational Linguistics in the School of Education, Communication and Society, King's College London. His research interests include education in ethnically and linguistically diverse societies, additional/second language curriculum and assessment, language policy and teacher professional development. He is a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences (UK).

Notes

1 The project was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Hong Kong (approval number: EA1603026). Informed consent from the teacher, students and their parents/guardians was secured.

References

- Abedi, J., and C. Lord. 2001. “The Language Factor in Mathematics Tests.” Applied Measurement in Education 14 (3): 219–234.

- Abell, S. K., and M. A. Siegel. 2011. “Assessment Literacy: What Science Teachers Need to Know and be Able to Do.” In The Professional Knowledge Base of Science Teaching, edited by D. Corrigan, J. Dillon, and R. Gunstone, 205–221. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Attar, Z., E. Blom, and E. Le Pichon. 2020. “Towards More Multilingual Practices in the Mathematics Assessment of Young Refugee Students: Effects of Testing Language and Validity of Parental Assessment.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, doi:10.1080/13670050.2020.1779648.

- Borg, S. 2003. “Teacher Cognition In Language Teaching: A Review of Research on What Language Teachers Think, Know, Believe, and Do.” Language Teaching 36 (2): 81–109.

- Brinton, D. M., M. A. Snow, and M. B. Wesche. 2003. Content-Based Second Language Instruction. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Cammarata, L., and C. Haley. 2018. “Integrated Content, Language, and Literacy Instruction in a Canadian French Immersion Context: A Professional Development Journey.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21 (3): 332–348.

- Cenoz, J., F. Genesee, and D. Gorter. 2014. “Critical Analysis of CLIL: Taking Stock and Looking Forward.” Applied Linguistics 35 (3): 243–262.

- Coyle, D., P. Hood, and D. Marsh. 2010. CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- DeLuca, C., D. LaPointe-McEwan, and U. Luhanga. 2016. “Approaches to Classroom Assessment Literacy: A New Instrument to Support Teacher Assessment Literacy.” Educational Assessment 21 (4): 248–266.

- Earl, L. 2003. Assessment as Learning: Using Classroom Assessment to Maximise Student Learning. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press.

- Goris, J., E. Denessen, and L. Verhoeven. 2013. “Effects of the Content and Language Integrated Learning Approach to EFL Teaching: A Comparative Study.” Written Language & Literacy 16 (2): 186–207.

- Gorter, G., and J. Cenoz. 2017. “Language Education Policy and Multilingual Assessment.” Language and Education 31 (3): 231–248.

- Hönig, I. 2010. Assessment in CLIL: Theoretical and Empirical Research. Saarbrücken. Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag Dr. Müller.

- James, M. 2008. “Assessment and Learning.” In Unlocking Assessment: Understanding for Reflection and Application, edited by S. Swaffield, 20–25. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Lam, R. 2019. “Teacher Assessment Literacy: Surveying Knowledge, Conceptions and Practices of Classroom-Based Writing Assessment in Hong Kong.” System 81: 78–89.

- Leontjev, D., and M. deBoer. 2020a. “Conceptualising Assessment and Learning in the CLIL Context: An Introduction.” In Assessment and Learning in CLIL Classrooms: Approaches and Conceptualisations, edited by M. deBoer, and D. Leontjev, 1–27. Cham: Springer.

- Leontjev, D., and M. deBoer. 2020b. “Multimodal Mediational Means in Assessment of Processes: An Argument for a Hard-CLIL Approach.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, doi:10.1080/13670050.2020.1754329.

- Leontjev, D., T. Jakonen, and K. Skinnari. 2020. “Assessing (for) Understanding in the CLIL Classroom.” In Assessment and Learning in CLIL Classrooms: Approaches and Conceptualisations, edited by M. deBoer, and D. Leontjev, 205–228. Cham: Springer.

- Leung, C. 2009. “Second Language Teacher Professionalism.” In Cambridge Guide to Second Language Teacher Education, edited by A. Burns, and J. C. Richards, 49–58. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leung, C. 2014. “Classroom-based Assessment: Issues for Language Teacher Education.” In Companion to Language Assessment (Vol. III), edited by A. Kunnan, 1510–1519. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Levi, T., and O. Inbar-Lourie. 2020. “Assessment Literacy or Language Assessment Literacy: Learning from the Teachers.” Language Assessment Quarterly 17 (2): 168–182.

- Lo, Y. Y., and D. Fung. 2020. “Assessments in CLIL: The Interplay Between Cognitive and Linguistic Demands and Their Progression in Secondary Education.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 23 (10): 1192–1210.

- Lo, Y. Y., D. Fung, and Y. Qiu. 2021. “Assessing Content Knowledge Through L2: Mediating Role of Language of Testing on Students’ Performance.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, doi:10.1080/01434632.2020.1854274.

- Massler, U., D. Stotz, and C. Queisser. 2014. “Assessment Instruments for Primary CLIL: The Conceptualisation and Evaluation of Test Tasks.” Language Learning Journal 42 (2): 137–150.

- Mercer, N., and C. Howe. 2012. “Explaining the Dialogic Processes of Teaching and Learning: The Value of Sociocultural Theory.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 1 (1): 12–21.

- Morton, T. 2016. “Conceptualizing and Investigating Teachers’ Knowledge for Integrating Content and Language in Content-Based Instruction.” Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education 4 (2): 144–167.

- Morton, T. 2020. “Cognitive Discourse Functions: A Bridge Between Content, Literacy and Language for Teaching and Assessment in CLIL.” CLIL Journal of Innovation and Research in Plurilingual and Pluricultural Education 3 (1): 7–17.

- Morton, T., and A. Llinares. 2017. “Content and Language Integrated Learning: Type of Programme or Pedagogical Model?” In Applied Linguistics Perspectives on CLIL, edited by A. Llinares, and T. Morton, 1–16. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Otto, A. 2018. “Assessing Language in CLIL: A Review of the Literature Towards a Functional Model.” LACLIL 11 (2): 308–325.

- Otto, A., and J. L. Estrada. 2019. “Towards an Understanding of CLIL in a European Context: Main Assessment Tools and the Role of Language in Content Subjects.” CLIL Journal of Innovation and Research in Plurilingual and Pluricultural Education 2 (1): 31–42.

- Quartapelle, F. 2012. Assessment and Evaluation in CLIL. www.aeclil.altervista.org.

- Shaw, S. 2020. “Achieving in Content Through Language: Towards a CEFR Descriptor Scale for Academic Language Proficiency.” In Assessment and Learning in CLIL Classrooms: Approaches and Conceptualisations, edited by M. deBoer, and D. Leontjev, 29–56. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Shepard, L. A. 2019. “Classroom Assessment to Support Teaching and Learning.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 683 (1): 183–200.

- Shohamy, E. 2011. “Assessing Multilingual Competencies: Adopting Construct Valid Assessment Policies.” The Modern Language Journal 95 (3): 418–429.

- Skinnari, K., and E. Bovellan. 2016. “CLIL Teachers’ Beliefs About Integration and About Their Professional Roles: Perspectives from a European Context.” In Conceptualising Integration in CLIL and Multilingual Education, edited by T. Nikula, E. Dafouz, P. Moore, and U. Smit, 145–167. Multilingual Matters.

- Snow, M. A., M. Met, and F. Genesee. 1989. “A Conceptual Framework for the Integration of Language and Content in Second/Foreign Language Instruction.” TESOL Quarterly 23 (2): 201–217.

- Stiggins, R. J. 1995. “Assessment Literacy for the 21st Century.” Phi Delta Kappan 77 (3): 238–245.

- Xavier, A. 2020. “Assessment for Learning in Bilingual Education/CLIL: A Learning-Oriented Approach to Assessing English Language Skills and Curriculum Content in Portuguese Primary Schools.” In Assessment and Learning in CLIL Classrooms: Approaches and Conceptualisations, edited by M. deBoer, and D. Leontjev, 109–136. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Xu, Y., and G. T. L. Brown. 2016. “Teacher Assessment Literacy in Practice: A Reconceptualization.” Teaching and Teacher Education 58: 149–162.

Appendix. Two students’ written reports with Miss T’s marking and comments