ABSTRACT

Linguistic diversity at Czech schools has increased in the last decade, and it has become a new everyday reality. Nevertheless, there is still a lack of studies investigating lived experiences with managing multilingualism at schools. Our study examines schools as multilingual social spaces in which the visible language choice on signs reveals the language regime based on ideologies and policies. We contextualize our study according to top-down language policy, and the essential theoretical concepts such as social space or language regime are explained. The linguistic landscapes at schools (so-called schoolscapes) are analysed and interpreted to capture schools as multilingual social spaces. The focus lies on (1) displayed languages; (2) authorship of the object: (3) location of the object. The data from schoolscaping are complemented by interviews with school principals, who are responsible for language choice decisions. The investigation took place in four schools, where multilingualism plays an essential role. The results indicate that despite the multilingual reality and the promotion of multilingualism by anchoring it in the agenda of inclusive education, language homogenization is operative in schools. Our results are relevant for exploring the linguistic environments and language regimes at schools and reveal possible explanations for linguistic homogenization.

1. Introduction

This article describes language regimes at four urban schools in the Czech Republic, where multilingualism is an everyday reality. Due to social and partially also historical circumstances such as migration, free movement of persons in the EU and political development, multilingualism is becoming a norm in today’s diverse society and the same phenomenon is emerging in schools. Therefore, it is beneficial to explore how schools develop ways of managing linguistic diversity also termed as a school’s language regime. This is an important issue for at least two reasons:

Firstly, the discrepancy between the linguistic repertoire of pupils and the languages of schools is recognized as a barrier to the educational success of migrant children (e.g. García and Sylvan Citation2011). At the same time, some studies indicate that pluralistic approaches are, at least on a conceptual level, well-accepted in schools (Lundberg Citation2019). Secondly, previous research has shown (partial) cognitive advantages of multilingual pupils (e.g. Bialystok Citation2009), however, in the context of transnational migration, language is seen as a factor in (social) exclusion at schools (Piller Citation2012). Therefore, analysing language regimes and their justifications could shed a light on the ambiguous perception of multilingualism at schools.

In our study, we work on the assumption that multilingualism concerns individuals and groups using and sharing different languages in one place, which gives rise to multilingual social spaces. Schools represent a deliberate and planned environment where learners are subjected to powerful messages about language(s) from local (and transnational) authorities (Brown Citation2005) or language ideology. Our study draws on an analysis of the linguistic landscape (Landry and Bourhis Citation1997) that is located at school, the so-called schoolscape, as analysing the visual part of the language regime shows assumptions and expectations for what is normal, appropriate, and legitimate (Brown Citation2005). We understand linguistic landscaping as a methodological framework, that allows us to analyse the school as a social space. To enrich the data from schoolscaping, we conducted interviews with principals, who provided us an insight into decision-making practices about including the language(s) in the school environment and their location. They also described the specific interactions among school members, specifically through signs used in the school space (Scollon and Scollon Citation2003). This approach provides an original perspective on language regimes; it allows us not only to describe the visual part of the linguistic landscapes of multilingual schools but also the intentions behind them.

2. Contextualization: Language policy and real-life multilingualism

Albeit multilingualism is becoming a norm in the Czech Republic, there are insufficient data on linguistic diversity; we know only that the total number of ‘foreigners’ has been constantly rising in the last 20 years.Footnote1 In 2019, the total number of foreigners was 5.8% of the population in the Czech RepublicFootnote2 (Data on number of foreigners Citation2021). Urban localities are, however, characterized by a considerably higher proportion of foreigners.

From the perspective of languages in education in the Czech Republic and Europe, there is a general ideological agreement that Europeans should strive to be multilingual. The aim settled in ‘Barcelona Conclusions’ (Presidency Conclusions … Citation2002) is that every European citizen should know and understand at least two foreign languages. The European language policy called 1 + 2, i.e. ‘mother tongue + two foreign languages’, has been developed to achieve this aim. Among other things, this language policy entails an ideological position on languages: there is a precise categorization of ‘mother tongues’ in contrast to ‘foreign languages’ and their hierarchical positioning.Footnote3

In terms of language policy in the Czech Republic, we can observe great interest in monitoring foreign languages.Footnote4 However, the data on so-called real-life multilingualism (e.g. Vetter Citation2013) in schools in the Czech Republic are missing. Moreover, surveying linguistic diversity is complicated by the mixing of language categories with categories related to ethnicity and nationality. For instance, the Czech Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sports surveyed only the number of ‘pupils-foreigners’Footnote5; their number in the school year 2020/2021 was around 3.1% (Statistická ročenka školství … Citation2021). From the perspective of nationality, the majority of ‘pupils-foreigners’ at schools hold a Vietnamese, Slovak, Ukrainian, Russian, or Mongolian citizenship (Statistická ročenka školství … Citation2021).

The real-life multilingualism and family languages of pupilsFootnote6 stand outside of the interest of the language policy. Despite curricular documents acknowledging linguistic diversity and multilingualism, Czech is automatically considered the national language, the mother tongue of pupils and, at the same time, the only language of instruction (The framework educational … Citation2021). This ideological position is reinforced by the fact that the issue of linguistic diversity in the Czech Republic is addressed as a matter of inclusive education. It follows The Salamanca Statement … (Citation1994), which provides a framework for including children with disadvantages and disabilities, including children from linguistic and ethnic or cultural minorities, into schools. From this perspective, multilingualism is seen as a ‘disadvantage’, and it reinforces the idea of necessity of inclusion of multilingual pupils into the (imagined) Czech-speaking majority. This stance is often supported by the researchers who approach the issue of linguistic diversity from the field of social and special education, (e.g. Denglerová, Kurowski, and Šíp Citation2020; Kostelecká, Hána, and Hasman Citation2017; Radostný et al. Citation2011). In other words, Czech language policy in education attempts, under the label of inclusion, to ‘homogenize’ the linguistic diversity, i.e. to keep the dominance of one language (so-called monolingual habitus, Gogolin Citation1998) and to ‘narrow’ the linguistic repertoire (Busch Citation2012) used by pupils in schools to that of 1 + 2.

3. Schools as multilingual spaces with specific language regimes

Our study assumes that linguistic practices are not to be regarded as stable or even arbitrary but as rooted in a situation and strongly related to the social contexts of their use (Canagarajah Citation2018; Pennycook Citation2010; Scollon and Scollon Citation2003). Then, multilingualism is not what individuals have or lack but what the environment enables and disables them to deploy (Blommaert, Collins, and Slembrouck Citation2005, 213). In other words, multilingualism is structured and regulated by different social spaces.

Understanding space as social space draws our attention to objects and social and personal relationships and their positioning in the space (Lefebvre Citation1991). Space also has a constructive and performative function. In the social connotation, the term ‘space’ is always connected to power (in Foucault’s senseFootnote7). Social space, as we conceive it in this study, is: (1) constructed through interaction and therefore a product of social relations (Massey and Massey Citation2005, 9; Purkarthofer Citation2014, 16–17); (2) multiple and ‘discoherent’ (Purkarthofer Citation2018, 218). Far from being uniform, social space is considereda site where various narratives meet, interact, co-exist, or compete. Following the sociolinguistic tradition, space can be understood as a potentiality in how language practices and language regimes can be put together (Blommaert, Collins, and Slembrouck Citation2005).

To get an insight into linguistic practices within the social space, an analytical view on the linguistic landscape (Landry and Bourhis Citation1997) seems to be beneficial. A linguistic landscape can be understood as the ‘scene where the public space is symbolically constructed’ (Ben-Rafael, Shohamy, and Barni, Citation2010, xi). In Lefebvre’s conception of social space (Citation1991), signs and written elements in public places refer to representations of space, to what is planned and conceived.

The specific location is crucial for language use, language choice, reception of language (e.g. Scollon and Scollon Citation2003; Blommaert, Collins, and Slembrouck Citation2005), or even for the language regime. According to Coulmas (Citation2005, 7), ‘[a] language regime can be described as a set of constraints on individual language choices’ that regiments language use in different ways (whether explicit or implicit), and is composed of habits, legal provisions, and ideologies.Footnote8 However, these components are not always in accordance with one another and can demonstrate inconsistencies in the language regime (Coulmas Citation2005).

It must be emphasized that a school as a social space evinces some specific characteristics that need to be mentioned. Willems and Eichholz (Citation2008, 871) point out that a school can in no way be seen as a singular space but rather as a complex configuration of interactive spaces that might co-exist or overlap, persist or change, exist simultaneously or successively. Nevertheless, a school is an institution that significantly influences the language use and acquisition of many individuals (Purkarthofer Citation2014, 10).

Previous research has shown how school space is influenced by the linguistic environment (especially signs and signages) and, specifically, by the sign makers (teachers, e.g. Morgan Citation2004; administrators, e.g. Eaton Citation2005; or students, e.g. Prior Citation2009). Furthermore, researchers revealed that at schools, a dominant and constantly reproduced ideology of positioning the majority language as the only language of communication is still present (Blackledge and Creese Citation2010).

4. Methodology of the study

The study aims to explore language regimes at four different schools that view themselves as multilingual. More specifically, we focus on the description of the visible part of the language regime and of intentions behind linguistic landscapes.

In our research, to describe the visible part of the language regime, we conducted an investigation of the linguistic landscapes (schoolscapes) and interviews with the principals, to decribe intentions behind linguistic landscapes. Using this methodological framework, our research approach links the materialized (spatial) practice with a reflection of (spatial) language representations, which allowed us to focus on the constitution of language regime that is based on the representation of space.

4.1. Research sample

Our research was carried out at four urban schools (primary and lower secondary level) in Brno (Czech Republic).Footnote9 Three schools define themselves in relation to multilingualism in their School educational programs (SEP)Footnote10, and we added one school without any focus on language, but with a relatively high number of ‘pupils-foreigners’ (see ).Footnote11

Table 1. Research sample: Schools.

4.2. Capturing linguistic landscape of schools: schoolscaping

In our study, we used schoolscaping as a specific approach to linguistic landscaping (Landry and Bourhis Citation1997) in analysing the linguistic environment of schools (or educational institutions). According to Brown (Citation2005), schoolscape comprises the physical and social setting in which teaching and learning take place. Although schoolscaping is not very common in research debates, the interest of researchers in analysing the linguistic landscape in the educational context has been rising in the last decade (e.g. Astillero Citation2017; Bernardo-Hinesley Citation2020; Wu, Silver, and Zhang Citation2021).

The data were collected by photographing objects with written utterances on them. For each school, the area from the door and the entrance hall to the inner corridors was included.Footnote12 242 objects were detected and photographed. The data corpus includes signages, signs, and objects such as students’ projects and results of their works that display languages (see ). We must point out that the number of photographed objects does not correspond with the number of written utterances in different languages, i.e. in some instances, one photographed object could display more utterances in different languages. In some instances, some objects were photographed and included in the sample as they contained language (pupils’ names), even though they would not usually be understood as utterances.

Table 2. Number of photographed objects and number of written utterances in different languages.

We have employed the methodological approaches found in Purkarthofer (Citation2014) and Barni and Bagna (Citation2008) in which every single object is categorized with regard to the following categories:

Languages displayed on the object. In our analysis, we have not only identified and categorized each language, but we have also grouped them according to the conceptualization used by language policy as follows: (a) language of instruction, (b) foreign languages, (c) pupils’ family languages (other than the language of instruction).Footnote13

Authorship of the (photographed) object. We have divided objects into those produced by agents representing the school institution (incl. objects that have been created at the request of teachers) and products from the pupils.

Location of the object. We have made the distinction between elements located at the front door or in the entrance hall, which means that they are directed at a wider public or even visible from the outside, and elements located in inner parts of the school building that are mostly accessible only by the staff and the pupils.

To ensure the validity of the analysis, two researchers (authors) categorized and discussed the photographed objects and identified the languages.

4.3. Interviews with principals

Interviews with four principals (see ) were conducted. School principals are in a powerful position concerning establishing a language regime at school: they are responsible for creating an official school profile defined in the SEP and significantly contribute to co-constructing the linguistic space of the school in many respects.

Table 3. Research sample: Principals.

The data source of this part of our study are semi-structured interviews with the principals about: overall perception of languages, the role of languages at particular the school, the school-based language policy, foreign languages, languages of instruction, and pupils’ family languages.Footnote14 All interviews were transcribed and analysed using the qualitative content analysis method (Mayring Citation2010). For the analytical process, we decided on a deductive procedure with pre-defined categories (see ), i.e. we identified and coded all notions concerning language (idea units) and classified them into categories.Footnote15 The data were coded in MAXQDA program by two coders who consulted together on their results and coded again. After the final coding, the intercoder agreement was 79.3%.

Table 4. System of categories.

5. Results

In this section, we seek to explore how the linguistic landscapes of schools contribute to the constitution of multilingual spaces and what it conveys in terms of language regimes in place. Firstly, we present the general tendencies of all four schools and in the separate parts, we focus on each school in detail.

The overview of photographed objects (see ) indicates tendencies to keep the school environment linguistically homogenous, i.e.: There is a predominance of the language of instruction at all schools and almost all signs with informative function (e.g. Landry and Bourhis Citation1997) are written in the language of instruction. Other visible languages, primarily foreign languages, are predominantly only decorative in function, and they often present results of foreign language teaching. Pupils’ family languages (other than the language of instruction) are rarely displayed at schools, and they appear mostly as part of the student’s works and projects, or they are displayed on objects with decorative functions.

Table 5. Number of objects in displayed languages.

makes it evident that the institution produces the linguistic landscape in school. The pupils are little represented as authors of writings or other objects. Apart from learning posters that have probably been created at the request of teachers, there are almost no written traces left by students to be found in the corridors, toilets, or dressing rooms. Only four scratches were photographed with utterances written by pupils. It is evident that the school administrations are very much in control and pay careful attention to the design and arrangement of the space.

Table 6. Authorship of photographed objects.

Our data (see ) show that there are only relatively few signs in entrance halls. Information on signs is often linked to the rules at school or organizational directions. The Czech language is usually placed in the most prominent locations, thereby promoting the salience of Czech.Footnote16 The informational function was also sometimes fulfilled bilingually, i.e. in Czech and English. Although Czech is always displayed first, both languages express semantically equivalent information (Reh Citation2004). Thus, the informational function is linked to the political dimension: Czech represents the national language and English represents the lingua franca. Signs in other languages have mostly decorative functions, and they are often arranged in terms of ‘advertising’ multilingualism. Looking at the inner parts of the school buildings provides a much more diverse view of language regimes at schools, and for this reason, we address them in separate chapters.

Table 7. Location of the object.

Further, we focus on results from interviews with principals that gave us a better understanding of intentions that result in language regimes (see ).

Table 8. Number of categorized idea units in interviews.

The results of the overall conception of the school of multilingualism show that all principals promote their schools as a multilingual space, even if the term ‘multilingualism’ was not used. However, their declared commitment to multilingualism seems to have more of a symbolic function that merely indexes their acceptance of language diversity within the school establishment.

Surprisingly, principals did not thematize the issue of the language of instruction very often. As the language of instruction is undoubtedly set by the language policy (see chapter 1), there were no comments found that would acknowledge the possibility of instruction in a different language than Czech (or English at the international school).

Foreign languages were also rarely mentioned throughout the interviews. Even though they are not commented on very often, principals emphasize foreign languages often according to language policy or organization of foreign language teaching and not according to pupils` linguistic repertoire.

The issue of pupils’ family languages (other than the language of instruction)Footnote17 was addressed in terms of the inclusion of ‘pupils-foreigners’ into the school community and their participation on teaching, which is again held in one obligatory language of instruction. Further, principals pointed out that pupils’ family languages are not forbidden at any of their schools, but their potential for educational aims was not thematized.

5.1. School A: School focusing on ‘pupils-foreigners’

The findings show that, above all, most written utterances captured on photographs inside the school building are in the Czech language, i.e. language of instruction. Only 13 objects (out of 54) displayed languages other than Czech, however, mostly alongside Czech. Only four objects are exclusively in a foreign language without any explanation or translation in Czech. In over half of the cases where a language other than Czech appears, that other language is English.

The following languages are discerned in school A:

Czech (41)

Czech and English (4)

Only English (3)

Czech and German (1)

Czech and Vietnamese (1)

Czech and Russian (1)

Only Russian (1)

One word in several languages, including Czech (2)

Although, the inner space of the school is predominantly linguistically homogeneous, the principal from school A pointed out that multilingualism is perceived as part of the school's everyday reality, as the following quote makes clear:

When you walk down the corridor, and you hear several languages … Footnote18 (Principal A)

… our main priority is to teach children Czech … we try to teach them to behave like us, to integrate them into classes (Principal A)

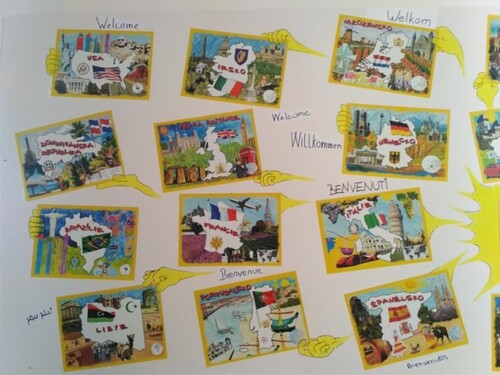

The wall in one of the inner corridors comprises a total of 39 sheets, each one showing the borderline silhouette of a political state, accompanied by the corresponding flag as well as the name of the country in the Czech language, and surrounded by figures wearing traditional clothing from that area as well as buildings, animals or landscapes stereotypically associated with the country of origin of pupils attending the school. Next to each paper presenting a country, the word ‘welcome’ is written in the official language of the respective state. However, the principal A mentioned that the sheets represent the countries of origin of pupils attending the school (including the Czech Republic) and not their languages.Footnote19

Figure 1. Decoration of the inner corridor in school A.

In the entrance hall, interesting usage of Czech combined with English was found. The signs are strongly linked to the announcement of rules, such as ‘Students are required to change their shoes when entering the school building’.

5.2. School B: School focusing on foreign languages

Most of the written utterances displayed on photographed objects inside the school building are in foreign languages, i.e. in German and English. Such foreign languages corresponded with languages offered as school subjects. In total, 30 (out of 49) objects display foreign languages or foreign languages combined with Czech, i.e. the language of instruction.

The following languages are discerned in school B:

Czech (19)

German (12)

English (9)

German and Czech (5)

English and Czech (4)

The predominance of foreign languages in the school space can be seen as a materialization of the stated self-concept of the school. However, in the interview, principal B pointed out efforts to work on the picture of an ‘ordinary school’ with a homogenous language profile as imagined by the language policy in education (see chapter 1). Pupils’ family languages are seen in a contradictory manner: On one hand, they are supported for everyday communication between pupils, according to the principal. On the other hand, they are perceived as a ‘disadvantage’ for the education process, and special educators or school psychologists are responsible for the agenda of inclusion of ‘pupils-foreigners’:

No, it's more like … , we don't do that [i.e. extra courses in Czech], even for pupils in first class, it's more like … , I have a special educator here, if I don't have one, then a psychologist. (Principal B)

Figure 2. A sign in German with an informative function (school B).

However, signs in the entrance hall and signs visible from the street are written only in Czech and they underline the ideological position of the school towards languages, especially the imagined monolingual perception of the broad public.

5.3. School C: International school

Most of the signs and signages displayed on photographed objects inside the school building are in English. The English language is the language of instruction at the school. 32 out of 70 objects display English, and nine display Czech and English. There were 13 objects found in Spanish, which is the dominant foreign language at the international school. Czech is, in this school, the language that is the least used for written signs.

Concerning languages, the following categories can be discerned:

English (32)

Spanish (13)

One word in several languages (11)

English and Czech (9)

Czech (5)

Although the school defines itself as ‘international’, the English language seems crucial for the school space.Footnote20 In fact, from the interview with the principal, it became apparent that English occupies a broad range of functions: it is the language of the curriculum, the language of instruction, foreign language, and pupils’ family language. The unquestionable position of English is relativized only in the sense of the relevance of the Czech language which is imagined as the language of communication with a broader public outside the school space. What is interesting is that other languages than English are addressed in the interview in terms of human rights and discrimination. In practice, it means that school C balances between language diversity and homogenization:

… such the all-intersecting principle that you are actually trying to set some rules and so that no one feels discriminated against at any moment … But on the other hand, there is the principle that everyone should understand … (Principal C)

Not surprisingly, the inner space of the school contains most of the objects and signs in the English language. Apart from English, many objects with Spanish on them were found, which represented foreign languages. Surprisingly, the Czech language is used for most official formal informative signs on safety or fire safety, which is the only visible mark of the Czech education system.

The entrance hall contained mainly signs with decorative and advertising functions, such as a sign with ‘Welcome’ in different languages (see ), which indicates a symbolic reference to an idealized image of multilingualism rather than an indexation of actually lived language diversity.

5.4. School D: School with no specific focus on languages

Most written utterances captured in photographs inside the school building are in the Czech language. Only 13 objects (out of 60) display languages other than Czech, i.e. the language of instruction. Only four objects are exclusively in a foreign language. These languages, however, are English and Russian, i.e. elite languages that students are educated to value. The actual family languages – primarily Vietnamese and Ukrainian – are almost not visible at this school.

Concerning languages, the following categories can be discerned:

Czech (47)

Czech and English (4)

Only English (3)

Czech and German (1)

Czech and Vietnamese (1)

Czech and Russian (1)

Only Russian (1)

One word in several languages, including Czech (2)

The dominance of Czech in the school building illuminates, again, the intention to keep the school linguistically homogeneous. The interview with principal D has also revealed the same perception of multilingualism as a ‘disadvantage’ as in school B (and, to a certain extent, in school A). Surprisingly, principal D heavily criticized interventions that are grounded in the agenda of inclusive education:

Because every ‘foreigner’ is a pupil with special needs at school, and if we need some relief for him … we send them to the counselling centre for pupils with special needs, where they will describe – or they should describe – how the child is cognitively, how – how they are socially (ehm), describes a family background, which is quite difficult, because parents usually do not speak Czech, so – so those reports are pointless because in the counselling centre they did not understand languages of pupils … (Principal D)

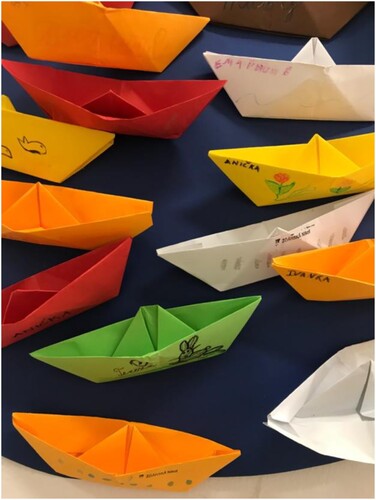

Figure 4. School project with pupils’ names in different languages in school D.

A fascinating practice was revealed in terms of signs with an informative function in the inner parts of the building. Although informative signs (e.g. school rules or announcements) are displayed only in the Czech, the interview with the principals has shown that information on the signs is translated into pupils’ family languages and provided separately to parents of multilingual pupils.

6. Discussion

Despite the different focus of the analysed schools, there were very similar practices in terms of language regime found:

‘Homogenization’ prevails over linguistic diversity. On one hand, our data from interviews emphasize that multilingualism and pupils` family languages are accepted and even, to some extent, promoted as a characteristic attribute of these schools, on the other hand, the almost substantial absence of languages other than Czech or elite foreign languages tells a different story. It reveals the merely symbolic nature of such declarations as they ultimately do not translate into practices that would anchor multilingualism in everyday school life. In other words, the language regimes in our schools tend to keep them linguistically homogeneous despite the fact, that principals are aware of the presence of real-life multilingualism. Furthermore, our study has revealed the discrepancy between manifestations and lived linguistic practices (Landry and Bourhis Citation1997) that illustrate the gap between policy in education and real-life multilingualism (e.g. Vetter Citation2013).

‘Homogenization’ is empowered by the language policy in education. As the language policy in education leads to ‘narrowing’ the linguistic repertoire of pupils in terms 1 + 2 (see chapter 1), the most displayed languagesFootnote21 in schools are ‘mother tongue’ and foreign languages, whereas ‘mother tongue’ is automatically perceived as pupils` family language, the language of instruction, and it is generally occupied by Czech as the (imagined) language of the majority. Other language constellations that would respect the pupils’ family languages were neither displayed nor mentioned in interviews. Thus, the decisions about the visible part of the language regime at schools are affected more by the language policy than by lived experiences with languages at schools. In doing so, the ideology of positioning the majority language is reproduced (e.g. Blackledge and Creese Citation2010).

Inclusion as a way to overcome linguistic diversity. Compared to other studies analysing schoolscapes in post-communist countries (e.g. Biró Citation2016; Szabó Citation2015) that usually explain linguistic homogenization in the context of empowerment of nationalistic ideologies, we have shown that setting of language regimes heading to linguistic homogenization is anchored in the agenda of inclusive education. Unfortunately, language regimes based on this agenda strengthen the perception of multilingualism as a ‘disadvantage’ and it shows a tendency to devalue real-life multilingualism as a ‘problem’ that must be overcome. Interestingly, very similar processes of linguistic assimilation in Catalonia (Spain) are described by Sáenz-Hernández et al. (Citation2021). Piller (Citation2012) explains the tendencies of linguistic homogenization as result of inclusion policies to render linguistic repertoire invisible, and to render inequalities, discrimination, and socio-economic exclusion invisible. The problematic intersection between inclusion and multilingualism indicated in our study is empowered by the policy represented by OECD, which perceives other languages as language(s) of instruction also as ‘barriers’ for education (e.g. Hajisoteriou and Neophytou Citation2022).

7. Conclusions

The language regimes of the schools investigated are disconnected as real-life multilingualism is not mirrored within the schools’ linguistic landscape. This is underlined by the fact that educational policy incorporates language diversity and the issue of inclusive education (‘multilingualism as a problem’), which results in tendencies to keep schools linguistically homogenous. Therefore, despite the declared acknowledgment of multilingualism, the monolingual habitus (Gogolin Citation1998) remains operative in all four analysed schools. Thus, we suggest that multilingual spaces should be fostered within schools to motivate developing proficiency in different languages (e.g. Astillero Citation2017; Bisai and Singh Citation2018; Gorter and Cenoz Citation2015). Languages of pupils’ families should also be included to let all the pupils use their complete linguistic repertoire (e.g. Blackledge and Creese Citation2010; García and Kleyn Citation2016). Further research should focus on pupils` perceptions of languages such as dominant language constellations (Aronin and Vetter Citation2021), and investigate relations between language regimes and pupils` family languages used at home and at schools.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Miroslav Janík

Miroslav Janík is an assistant professor at the Institute for Research in School Education at the Faculty of Education of Masaryk University (Czech Republic) and a lecturer at the university in Trier (Germany). In his research activities, he concentrates on various forms of multilingualism at schools and foreign language teacher education.

Marie-Antoinette Goldberger

Marie-Antoinette Goldberger is currently working as a project collaborator at the Institute for Research in School Education at the Faculty of Education of Masaryk University (Czech Republic) and teaching German as a second language at a private language school in Vienna (Austria). Her research focuses on migration-related multilingualism and the discursive construction of migrant children in media.

Notes

1 Languages of ethnic groups or minority groups are not surveyed in the Czech Republic, and they are not the main focus of this study.

2 The following ethnic groups were dominant in the Czech Republic: Ukrainian, Slovak, Russian, Vietnamese, Romanian, Bulgarian, Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian, and Roma. Typical migrant groups are: Ukrainian, Vietnamese, Slovak and Russian. More information about migration in the Czech Republic: International Migration Outlook Citation2020 (Citation2021). This situation rapidly changed after the migration wave from Ukraine in 2022.

3 Unquestionable first position of mother tongue, a preference for European languages, and a specific position of English as the first foreign language.

4 The data from Eurostat show that 98% of pupils at the secondary level (ISCED 2) learn two foreign languages in the Czech Republic. In 2016, 99.2% of pupils learned English, 60% learned German, 14% learned French, and 12% learned Spanish (Foreign Languages Learnt per Pupil in Upper Secondary Education Citation2018). Pupils must start learning the first foreign language by the age of 8–9 years and the second foreign language by 13–14 (Key Data on Teaching Languages at School in Europe Citation2017).

5 The term ‘pupil-foreigner’ is often used by a top-down language policy, it is not based on any scientific background, and it does not have any English equivalent. It covers a description of pupils with non-Czech citizenship who can be multilingual, or come from a migrant background, or belong to different ethnic minorities with other citizenship than Czech. We use quotation marks to show the authors’ reservations about using this term.

6 The term family language refers to the language of socialisation of multilingual children within the family (De Houwer Citation2009; Slavkov Citation2017).

7 It means that ‘power is everywhere’, diffused and embodied in discourse, knowledge and ‘regimes of truth’.

8 Language ideology refers to explicit or implicit representations on the intersection of language and how human beings exist in social world (Woolard Citation1992).

9 The education system in Czech Republic is essentially egalitarian, differences between schools are based on various school focus (sport, arts, sciences, languages …), size of the school, management, founder etc.

10 Curricular documents in the Czech Republic are developed at two levels – state level and school level. The state level is represented by the The Framework Educational Programme for Basic Education (FEP). The school level is represented by School educational programmes (SEPs).

11 Selection of schools was conducted following an analysis of SEPs in all schools (96) in Brno (Czech Republic). If schools describe themselves in connection with languages, they do so in the following ways: schools focusing on foreign pupils (11 schools), international and European schools (4 schools), and schools focusing on foreign languages (11 schools). In our sample, we selected one representative school from each group.

12 Classrooms were not included in the sample because at Czech schools ‘class teachers’ are traditionally responsible for decorating them and the linguistic landscape of classrooms does not automatically have to match the school-based language regime.

13 We decided on a deductive procedure with pre-defined categories based on categorization of languages in the FEP (see above).

14 The average length of interviews with principals was 33:17 min (Principal A: 33:14 min, Principal B: 34:07 min, Principal C: 28:46 min, Principal D: 37:02 min).

15 Since the principals used mainly the terminology of educational policy which mirrors the categorization of displayed languages based on FEP, we decided not to do inductive coding and use the same categories plus one category capturing the overall conception of multilingualism at the school.

16 In the international school, this position is taken over by English.

17 Terms pupils' family languages (other than the language of instruction) and family languages will be used synonymously.

18 All extracts were translated into English by the authors. The presented extracts just illustrate the discussed phenomena, i.e. it is not complete and exhausting summary of all utterances on the particular phenomena.

19 This illustrates also mixing of language categories with categories related to ethnicity and nationality in schools that is typical for the language policy (see chapter 1).

20 In the context of so-called international schools, English is the common language of instruction (Hayden and Thompson Citation1995).

21 The relationship of language policy and schoolscape was described by e.g. Landry and Bourhis (Citation1997).

22 The choice of elementary school is entirely up to the parents. But each public school has its ‘catchment area’. The district school must preferentially accept children who live in its ‘catchment area’, incl. pupils with migration background, who live in the ‘catchment area’.

23 The school offers courses in Czech, organizes classes with language assistants, and cooperates intensively with the regional integration centre.

24 The international school follows the curriculum of Cambridge International Education. Additionally, the school offers Czech as foreign language and Czech classes according to The Framework Educational Programme for Basic Education. Parents are required to pay a tuition fee.

25 Two different numbers are caused by the fact that the international school pupils' family languages (other than the language of instruction) correspond for some pupils with foreign languages.

References

- Aronin, L., and E. Vetter, eds. 2021. Dominant Language Constellations Approach in Education and Language Acquisition. Cham: Springer Nature.

- Astillero, S. F. 2017. “Linguistic Schoolscape: Studying the Place of English and Philippine Languages of Irosin Secondary School.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education, Arts and Sciences 4 (4): 30–37.

- Barni, M., and C. Bagna. 2008. “A Mapping Technique and the Linguistic Landscape.” In Linguistic Landscape, edited by E. Shohamy and D. Gorter, 166–180. New York: Routledge.

- Ben-Rafael, E., E. Shohamy, and M. Barni. 2010. "Introduction: An Approach to an ‘Ordered Disorder’." In Linguistic Landscape in the City, edited by E. Ben-Rafael, E. Shohamy, and M. Barni, xi–xxviii. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Bernardo-Hinesley, S. 2020. “Linguistic Landscape in Educational Spaces.” Journal of Culture and Values in Education 3 (2): 13–23. doi:10.46303/jcve.2020.10.

- Bialystok, E. 2009. “Bilingualism: The Good, the bad, and the Indifferent.” Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 12 (1): 3–11. doi:10.1017/S1366728908003477.

- Biró, E. 2016. “Learning Schoolscapes in a Minority Setting.” Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Philologica 8 (2): 109–121. doi:10.1515/ausp-2016-0021.

- Bisai, S., and S. Singh. 2018. "Rethinking Assessment–A Multilingual Perspective." Language in India 18 (4): 308–319.

- Blackledge, A., and A. Creese. 2010. Multilingualism: A Critical Perspective. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Blommaert, J., J. Collins, and S. Slembrouck. 2005. “Spaces of Multilingualism.” Language & Communication 25 (3): 197–216. doi:10.1016/j.langcom.2005.05.002.

- Brown, K. D. 2005. “Estonian Schoolscapes and the Marginalization of Regional Identity in Education.” European Education 37 (3): 78–89. doi:10.1080/10564934.2005.11042390.

- Busch, B. 2012. “The Linguistic Repertoire Revisited.” Applied Linguistics 33 (5): 503–523. doi:10.1093/applin/ams056.

- Canagarajah, S. 2018. “Translingual Practice as Spatial Repertoires: Expanding the Paradigm Beyond Structuralist Orientations.” Applied Linguistics 39 (1): 31–54. doi:10.1093/applin/amx041.

- Coulmas, F. 2005. “Changing Language Regimes in Globalizing Environments.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 175–176: 3–15. doi:10.1515/ijsl.2005.2005.175-176.3.

- Data on number of foreigners. (2021). “Czech Statistical Office.” https://www.czso.cz/csu/cizinci/number-of-foreigners-data.

- De Houwer, A. 2009. Bilingual First Language Acquisition. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Denglerová, D., M. Kurowski, and R. Šíp. 2020. “Communication as a Means of Development in a School with a High Percentage of Foreign Pupils.” Orbis Scholae 13 (3): 39–58. doi:10.14712/23363177.2020.4.

- Eaton, S. E. 2005. 101 Ways to Market Your Language Program: A Practical Guide for Language Schools and Programs. 2nd ed. Calgary: Eaton International Consulting.

- Foreign languages learnt per pupil in upper secondary education (general), 2011 and 2016 (%). (2018). “Eurostat.” https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=File:Foreign_languages_learnt_per_pupil_in_upper_secondary_education_(general),_2011_and_2016_(%25)_ET18.png.

- The Framework Educational Programme for Basic Education. 2021. “Ministry of Education, Uouth and Sports.” https://www.msmt.cz/areas-of-work/basic-education-1.

- García, O., and T. Kleyn. 2016. Translanguaging with Multilingual Students. Learning from Classroom Moments. New York: Routledge.

- García, O., and C. E. Sylvan. 2011. “Pedagogies and Practices in Multilingual Classrooms: Singularities in Pluralities.” The Modern Language Journal 95 (3): 385–400. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01208.x.

- Gogolin, I. 1998. “Sprachen Rein Halten – Eine Obsession.” In Über Mehrsprachigkeit, edited by I. Gogolin, S. Graap, and G. Liste, 71–96. Tübingen: Stauffenburg.

- Gorter, D., and J. Cenoz. 2015. “Translanguaging and Linguistic Landscapes.” Linguistic Landscape 1 (1-2): 54–74. doi:10.1075/ll.1.1-2.04gor.

- Hajisoteriou, C., and L. Neophytou. 2022. “The Role of the OECD in the Development of Global Policies for Migrant Education.” Education Inquiry 13 (2): 127–150. doi:10.1080/20004508.2020.1863632.

- Hayden, M., and J. Thompson. 1995. “International Schools and International Education: A Relationship Reviewed.” Oxford Review of Education 21 (3): 327–345. doi:10.1080/0305498950210306.

- International Migration Outlook 2020. (2021). “OECD.”

- Key Data on Teaching Languages at School in Europe. Eurydice Brief. (2017). “European Commision”.

- Kostelecká, Y., D. Hána, and J. Hasman. 2017. Integrace žáků-Cizinců v širším Kontextu. Pedagogická Fakulta. Praha: Univerzita Karlova.

- Landry, R., and R. Y. Bourhis. 1997. “Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 16 (1): 23–49. doi:10.1177/0261927X970161002.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. “The production of space.” In The People, Place, and Space Reader, edited by J. J. Gieseking, W. Mangold, C. Katz, S. Low, and S. Saegert, 289–293. New York: Routledge.

- Lundberg, A. 2019. “Teachers’ Beliefs About Multilingualism: Findings from Q Method Research.” Current Issues in Language Planning 20 (3): 266–283. doi:10.1080/14664208.2018.1495373.

- Massey, D., and D. B. Massey. 2005. For Space. London: SAGE.

- Mayring, P. 2010. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Grundlagen und Techniken. Frankfurt: Beltz.

- Morgan, B. 2004. “Teacher Identity as Pedagogy: Towards a Field-Internal Conceptualisation in Bilingual and Second Language Education.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 7: 172–188. doi:10.1080/13670050408667807.

- Pennycook, A. 2010. Language as a Local Practice. London: Routledge.

- Piller, I. 2012. “Multilingualism and Social Exclusion.” In The Routledge Handbook of Multilingualism, edited by M. Martin-Jones, A. Blackledge, and A. Creese, 297–312. New York: Routledge.

- Presidency conclusions. 2002. “Barcelona European Council 15 and 16 March 2002.” https://ec.europa.eu/invest-in-research/pdf/download_en/barcelona_european_council.pdf.

- Prior, J. 2009. “Environmental Print: Real-World Early Reading.” Dimensions of Early Childhood 37 (1): 9–13.

- Purkarthofer, J. 2014. Sprachort Schule: Zur Konstruktion von Mehrsprachigen Sozialen Räumen und Praktiken in Einer Zweisprachigen Volksschule. Wien: Hochschulschrift.

- Purkarthofer, J. 2018. “Children’s Drawings as Part of School Language Profiles: Heteroglossic Realities in Families and Schools.” Applied Linguistics Review 9 (2–3): 201–223. doi:10.1515/applirev-2016-1063.

- Radostný, L., K. Titěrová, P. Hlavničková, D. Moree, B. Nosálová, and I. Brychnáčová. 2011. Žáci s Odlišným Mateřským Jazykem v českých školách. Praha: Meta, ops.

- Reh, M. 2004. “Multilingual Writing: A Reader-Oriented Typology — With Examples from Lira Municipality (Uganda).” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 2004: 1–41. doi:10.1515/ijsl.2004.2004.170.1.

- The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. 1994. “United Nations and Ministry of Education and Science Spain.”.

- Sáenz-Hernández, I., C. Lapresta-Rey, C. Petreñas, and M. A. Ianos. 2021. “When Immigrant and Regional Minority Languages Coexist: Linguistic Authority and Integration in Multilingual Linguistic Acculturation.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 1–14. doi:10.1080/13670050.2021.1977235.

- Scollon, R., and S. Scollon. 2003. Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World. London: Routledge.

- Slavkov, N. 2017. “Family Language Policy and School Language Choice: Pathways to Bilingualism and Multilingualism in a Canadian Context.” International Journal of Multilingualism 14 (4): 378–400. doi:10.1080/14790718.2016.1229319.

- Statistická ročenka školství - výkonové ukazatele [Statistical Yearbook of Education - Performance Indicators]. 2021. “Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports.” http://toiler.uiv.cz/rocenka/rocenka.asp.

- Szabó, T. 2015. “The Management of Diversity in Schoolscapes.” Apples - Journal of Applied Language Studies 9 (1): 23–51. doi:10.17011/apples/2015090102.

- Vetter, E. 2013. “Where Policy Doesn’t Meet Life-World Practice – the Difficulty of Creating the Multilingual European.” European Journal of Applied Linguistics 1 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1515/eujal-2013-0005.

- Willems, H., and D. Eichholz. 2008. “Die Räumlichkeit des Sozialen und die Sozialität des Raumes: Schule zum Beispiel.” In Lehr(er)Buch Soziologie: Für die Pädagogischen und Soziologischen Studiengänge, Band 2, edited by H. Willems, 865–907. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. doi:10.1075/prag.2.3.01woo.

- Woolard, K. A. 1992. “Language Ideology: Issues and Approaches.” Pragmatics 2 (3): 235–249.

- Wu, Y., R. E. Silver, and H. Zhang. 2021. “Linguistic Schoolscapes of an Ethnic Minority Region in the PRC: A University Case Study.” International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–25.