ABSTRACT

Work Discussion, developed at the Tavistock Clinic in London, is a specific psychoanalytical method which is used in order to stimulate, encourage and support the development of a wide range of psychoanalytic skills and attitudes of relevance for psychotherapy and related fields of psychosocial work. For this aim Work Discussion is an element of several psychoanalytically based Master’s degree programmes. In the paper, it is discussed how the use of Work Discussion can be evaluated and the impact of Work Discussion on the development of psychoanalytic skills and attitudes can be investigated. With special respect to two Master’s degree programmes offered in Vienna, it is shown that teachers ranked Work Discussion as the most important element of a psychagogic Master’s programme and how Work Discussion seminar papers have been analysed in order to evaluate the professional developments of psychotherapeutic candidates of two psychoanalytic training institutes.

1. Looking for appropriate designs in order to evaluate Work Discussion

In 2017 Delia Schöck analysed 31 German publications of authors who published between 2002 and 2015 about the impact of Work Discussion on the acquisition of professional skills and attitudes (Schöck, Citation2018).Footnote1 She systemized the authors’ assumptions concerning the formation of these skills and attitudes and she discussed the way these authors give reason for their beliefs and conclusions. In these publications Work Discussion is characterized as a specific psychoanalytic teaching method which is used in order to stimulate, encourage and support the development of a wide range of competences. Schöck identified two dominant types of argumentation these authors give for this approach:

In some publications authors emphasize a structural correspondence between the peculiarity of Work Discussion and the peculiarity of these skills and attitudes which should be developed, often with reference to psychoanalytic theories and concepts like containment, affect regulation or mentalization. Datler and Datler (Citation2014) underline, for example, (i) that people who work in psychosocial fields have to understand their emotional processes, people’s emotional processes they work with and the close relation between these emotional processes with special reference to psychodynamic aspects as well as possible, (ii) and they argue that exactly this is taught in Work Discussion seminars. Thus authors explain theoretically that there are good reasons for the assumption or belief that Work Discussion is an appropriate approach for the formation of skills and attitudes which are highly relevant or even essential for psychotherapy, counselling, education and similar fields of work.

In some publications case material is also presented: authors refer more or less in detail to excerpts from working papers as well as discussions from the seminar. They illustrate the way in which the Work Discussion seminar was helpful in order to understand conscious and unconscious processes better which apparently took place in the reported situations, and sometimes authors describe, in which way the presenters’ quality of work increased during the Work Discussion seminar process. Thus, authors create casuistic evidence concerning the impact of Work Discussion on the development of psychoanalytic skills and attitudes.

From the background of a scientific interest in Work Discussion and its impacts both types of argumentation are indispensable: Statements about any subject are less of worth if these statements are not embedded in theory. And since Freud (Citation1895, p. 160 f.) published his epilogue to the report of his psychotherapeutic work with Elisabeth von R. in Studies on Hysteria it is well known that case reports which are written like short novels are necessary if a deep understanding of psychodynamic processes will grow (Datler, Citation2004). It would be particularly useful to study descriptions of individual cases, from which we can learn about the nature of the learning processes set in train by participation in a Work Discussion seminar.

Nevertheless, it has to be considered that single case reports are liable to be strongly determined by the subjective intentions, interpretations and decisions of the publishing person. As a consequence and according to comments published by Rustin and Pollard (Citation2018) it is therefore necessary to develop a broader scope of research designs and strategies in addition to those research activities which are currently dominant in German and probably also in English publications. Some rare examples for additional or alternative research designs and strategies can be found in Austria at the Alpen-Adria-University Klagenfurt (Sengschmied, Citation2017, p. 211; Turner & Ingrisch, Citation2009) and in Great Britain at the Tavistock Clinic (Hartland-Rowe, Citation2016) as well as at the University of Roehampton (Elfer, Greenfield, Robson, Wilson, & Zachariou, Citation2018).

In this paper, we report on two designs and strategies which have been developed at the University of Vienna in order to evaluate the impact of Work Discussion on the development of psychoanalytic skills and attitudes. We also present the first results. The Work Discussion seminars described are elements of two Master’s degree programmes offered at the University of Vienna.Footnote2 We refer to these programmes as ‘Programme A’ and ‘Programme B’.

2. Work Discussion in a Master’s degree programme for teachers (Programme A)

2.1. The curriculum of the Master’s degree programme (Programme A)

At the University of Vienna a particular Master’s degree programme is offered for experienced teachers: ‘Inclusive Education of Children and Adolescents with severe Emotional and Social Problems in the Context of Schools’.Footnote3 This Master’s programme lasts six semesters (three years) and is attended by about 25 teachersFootnote4 who wish to qualify for working with children and adolescents who are struggling with severe emotional and social problems. Once the teachers have qualified, they may legitimately refer to themselves as ‘psychagogues’.Footnote5 Within the organization of a school, they may then be working in a broad variety of settings, both with pupils and their familial and school-related environments.

In this course, numerous modules are delivered which are intended to enable the participants to acquire a basic psychoanalytic understanding of relationships (Wagner-Deutsch, Citation2017, p. 68). This should place them in a position to take a more differentiated view of phenomena occurring in their work, and thus to become more helpful to the children and adolescents as well as the parents and teachers with whom they come into contact. The curriculum of this programme covers a variety of theoretical seminars, three semesters of group analysis, group supervision as well as one-to-one supervision or personal psychotherapy. We call these items ‘course elements’. Each course element belongs to a module but indicates more precisely each significant part of the curriculum.

Observation and Work Discussion according to the Tavistock model are taught in three course elements:

During the first three semesters, participants have to attend seminars where Observation and Work Discussion according to the Tavistock model are taught: For the first one-and-a-half semesters each participant has to observe a single child in a school or kindergarten weekly. Written reports of these observations are presented in turn and discussed in a weekly observation seminar of five or a maximum of six students. In the following one and a half semesters, Work Discussion on the Tavistock model takes the place of observation. This course element is named ‘Observation and Work Discussion’.

During the sixth semester a very intensive Work Discussion seminar takes place. All the participants are then re-distributed into new groups – again with maximum five to six participants. Each group meets weekly for two 105 minutes sessions where two Work Discussion reports are presented and discussed. This course element is named ‘Work Discussion’.

In the 4th and 5th semester, a case discussion seminar takes place where almost weekly case material is discussed with a more explicit reference to theory. Although this seminar does not include weekly discussions of Work Discussion reports, participants have to write Work Discussion reports which are sometimes discussed in the seminar and sometimes by students in peer group seminars. This course element is named ‘Case Discussion Seminar’.

Readers may glean from this that Work Discussion is taught very intensively in this Master’s programme. This involves a high degree of commitment:

Participants are required to write, present and discuss a lot of Work Discussion reports in a large number of seminars, which takes a great deal of time and emotional involvement.

There is a financial cost to the course as well, as a large number of small Observation and Work Discussion groups need to be timetabled. These seminars are by far the most expensive elements of the course. It is not surprising that the course director and teachers are frequently asked whether all this effort and intensive input is necessary and worth the cost.

For this reason, among others, the course team began to evaluate the course.

2.2. The design of the evaluation of ‘Programme A’

At the end of the first course, initial interviews were conducted with selected students and instructors who had taken part in it. Based on the first analysis of these interviews we developed a specific form of interview to investigate the value, in the minds of participants, of the different modules of the course. We conceived these interviews as follows:

19 former participants of the training course, who agreed to be interviewed about six months after having finished the course, were sent an email requesting them to comment on five questions in the interview:

Question 1: Which element in the course was the most important for acquiring the highest number of valuable skills of value for doing psychagogic work?

Question 2: Which element was most important for acquiring the most relevant theoretical and background information for accomplishing psychagogic tasks?

Question 3: Which element was most helpful during the attendance of the course to enable me to assume psychagogic tasks?

Question 4: Which element was most helpful for enabling me to think clearly about my own psychagogic thoughts and actions?

Question 5: If, in the future the course team had to take out one element from the curriculum, which would be the one, in your view, which would be least missed.

During the interview itself the former students were given 19 small cards, each of which carried the name of the elements, and the name of the element teacher. Then they were presented with the first question and asked to spread the cards in a particular sequence, to indicate the relative value of the skills, knowledge contents and attitudes which they believed they had learnt, in relation to the performance of their psychagogic tasks. The course element on position 1 was ranked highest (‘most important or helpful’), the course element on position 19 was ranked lowest. The interviewee also was asked to explain his or her ranking.

The same procedure was then followed for the remaining four questions, in which the order of these 5 questions changed from interview to interview. The ranking of course elements concerning ‘Question 5’ had to be valued inverse: When an element was put on the lowest position the interviewee valued this element as ‘most important or helpful’. Concerning ‘Question 5’ the lowest position was therefore indicated as position 1.

When all the 19 interviews were done, every interviewee had ranked each course element with regard to each question on a position between 1 and 19. This enabled a research team to figure out statistically with regard to each question how each course element was ranked in relation to all the other elements by all interviewees (Datler, Katschnig, & Wagner-Deutsch, Citation2019; Wagner-Deutsch, Citation2017, p. 69). From this background, it was possible to find for each course element a position between 1 and 19 indicating the value of the element ranked with regard to each question by all interviewees. Finally, it was also possible to figure out an overall ranking on the basis of all data.

2.3. First results of the evaluation of ‘Programme A’

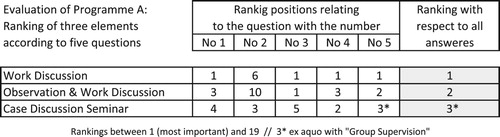

shows how the three course elements, which contained Work Discussion, were ranked:

With respect to the questions 1, 3, 4 and 5 the seminar ‘Work Discussion’ was ranked as the most important and helpful course element. The Work Discussion seminar got also the highest ranking when all the answers to all questions concerning all course elements were statistically analysed.

With respect to the Questions 1, 3, 4 and 5 the course element ‘Observation and Work Discussion’ was ranked on positions between 1 and 3. This seminar got the second highest ranking when all the answers to all questions concerning all course elements were statistically analysed.

With respect to the Questions 1–5 the course element ‘Case Discussion Seminar’ ranked on positions between 2 and 5. This course element got the third highest ranking, ex aquo with ‘Supervision in a group setting’, when all the answers to all questions concerning all course elements were statistically analysed.

Obviously the interviewees experienced Question 2 in relation to all the other questions differently. Nevertheless, it has to be noted: with respect to Question 2 none of these three elements were ranked lower than on position 10.

There is more to learn about this when these results will be linked with the evaluation of the comments which explain the sequencing of the cards (Wagner-Deutsch, Citation2017, p. 86). When the comments were categorized most comments were assigned to the category ‘Work discussion was helpful for a better understanding of work situations’: When the 19 interviewees explained their rankings they mentioned for 44 times that Work Discussion opened up new vistas of understanding and led definitely to a deeper understanding (Wagner-Deutsch, Citation2017, p. 159).

Although a broader discussion of the results of the content analysis will lead to valuable insights, the findings are limited: The interviewees’ comments tend to be generally short and do not explain in detail whether or not and to what extent ‘psychoanalytic skills, knowlege contents and attitudes’ have been developed. We took this into account when we discussed the design of the evaluation of ‘Programme B’.

3. Work Discussion in a Master’s degree programme in psychotherapy (Programme B)

3.1. The curriculum of the Master’s degree programme (Programme B)

In Austria, the education of psychotherapists is in two phases. The first is ‘Psychotherapeutic propaedeutics’ in which basic knowledge, skills and attitudes are taught. When this first phase has finished each candidate has to decide whether he or she wants to become during his or her second phase of the training a candidate in a psychodynamic/psychoanalytic, behavioural, systemic or humanistic training at a relevant specialist institute.

In 2004 the University of Vienna started a close cooperation with two psychoanalytic training institutions which are recognized by the Austrian government as psychotherapeutic training institutes for the second phase of the psychotherapeutic training: the Austrian Association of Individual Psychology (ÖVIP) and the Viennese Circle of Psychoanalysis and Self Psychology (WKPS). The Master’s degree programme, ‘Psychotherapy: Individual Psychology and Self Psychology’ is a four-year training whose graduates earn a qualification which enables them to become licensed psychotherapists, and to register on the approved with Austrian Ministry of Health.Footnote6 We call this Master’s degree programme, ‘Programme B’.

In the course of completing this training, there are a number of elements the participants must engage in: a personal training analysis, supervision, psychoanalytic/psychotherapeutic work, seminars on psychoanalysis and psychoanalytic research and a Work Discussion seminar. Sixteen to twenty participants are assigned to four, normally weekly Work Discussion groups for the first four terms.

Work Discussion primarily sets out to achieve two objectives:

Work Discussion is to help participants to think about situations and relationships at work with a psychoanalytic attitude before, at a later stage of their training, they begin working psychotherapeutically with their patients. For this reason, the Work Discussion seminars give a broad perspective in the analysis and description of occurrences in the ‘here and now’, taking account of both ‘internal’ and ‘external’ dimensions in a work situation.

Through Work Discussion, the participants are intended to experience from their first semester just how and in what respects the acquisition of psychoanalytic insights may be helpful in the shaping of their day-to-day psychosocial work.

Work Discussion as an obligatory element of a psychotherapeutic course as described here is unique in Austria. For this reason, the question arose how the significance of this element of training in a programme for acquiring professional psychoanalytic capacities could be interrogated more precisely.

3.2. Focussing the development of mentalization capacities

One of the authors of this paper, Michael Wininger, brought to this inquiry his interest in ‘mentalization’ which is a rapidly-growing field of study. By mentalization, we mean capacities that enable people to understand their own behaviour as well as the behaviour of other people as a meaningful expression of internal psychic processes.

In this context we differ (i) between such a general understanding of mentalization, (ii) particular theories about mentalization and the development of mentalization capacities, and (iii) particular methodological or technical approaches which were created in order to increase mentalization capacities. Furthermore, we presume that, seen from the background of a general understanding of mentalization, a broad variety of theories and publications about mentalization is existing although the term ‘mentalization’ is not to be found explicitly in some of these theories and publications. From this background the conceptualization of mentalization published by Peter Fonagy, Mary Target, Anthony Bateman and others is a particular conceptualization among other conceptualizations (see Allen, Fonagy, & Bateman, Citation2008; Bateman & Fonagy, Citation2019; Bevington, Fuggle, Cracknell, & Fonagy, Citation2017; Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist, & Target, Citation2002).

We noticed that developing capacity for mentalization is an objective of numerous educational and continuing education programmes, even though the term mentalization itself is only sometimes explicitly employed. But there has so far been little investigation of whether running such educational and continuing education programmes in fact leads to a growth in these capacities. A method was devised for the assessment of mentalization capacities, in the form of the Adult Attachment Interview (Hesse, Citation1999) and the Reflective Function Scale (RFS) (Fonagy, Target, Steele, & Steele, Citation1998). However, this method in its original form was not well adapted for investigating mentalization capacities in the professional fields where the participants of such an educational and training programme often work.

A relevant modification of the Adult Attachment Interview procedure, developed by Ariane Slade and her colleagues in New Work, was identified (Slade, Citation2005; Slade, Aber, Berger, Bresgi, & Kaplan, Citation2005). We modified it further, in order to gather information, from the perspective of attachment theory, about the relationship between professional workers and their clients, and their internal mental representations from the content and way of speaking (Wininger, Citation2017).Footnote7

Using this new procedure, we conducted interviews with 35 students, who were at the beginning of Programme A or Programme B. We shall repeat these interviews at the conclusion of the programme. With the help of the Reflective Functional Scale (RFS) it is intended to establish whether, and to what degree, mentalization capacities have grown.

Such an evaluation employed at the beginning and end of a course of training leaves questions unanswered about which specific changes are the outcome of which specific processes, and at what stages of the programme these take place. From this, another question arises as to whether changes in mentalization capacities can already be found to occur within the first four semesters of our Programme B Work Discussion seminars.

3.3. The analysis of Work Discussion seminar papers

Our interest in investigating this question was enhanced by the circumstance that the participants in our Work Discussion seminars had to prepare a short seminar paper, roughly three pages long, at the end of each semester. Their task was plainly stated. They were asked to select an excerpt from one Work Discussion report and to analyse it according to the principles by which work in the Work Discussion seminars should have been carried out. These principles were described in a paper circulated amongst all the participants (Datler & Datler, Citation2014). According to these principles, the method was to go through a report line by line and paragraph by paragraph, always in search of answers to the same three questions:

How might the people described have experienced the situations which can be found in the report?

How, when seen against this background, could the behaviour of the people, as described, be understood?

How did people experience the subsequent situation, which was lead to by their behaviour.

Once the seminar papers had been handed in, the seminar leaders responsible for Work Discussion met to discuss and assess them.Footnote8 In the context of these discussions, the seminar leaders and our research group defined, step by step, four dimensions to be used in assessing the seminar papers in order to identify specific mentalizing capacities.

To illustrate our method, we now present excerpts from the first and fourth seminar paper of one of the students, Narin Yilmaz (N.Y.).Footnote9

3.3.1. The assessment of Paper No 1

Ms. Yilmaz works at an institution where counselling and psychotherapy is offered to refugees and migrants. In her first seminar paper she quotes from one of her reports where a dialogue between her and a young father, named Arda, is described:

Arda: I no longer feel comfortable at home. It is funny somehow.

N.Y.: Arda, do you maybe not feel welcome here?

Arda: Yes, exactly. And I feel better at my sister's place. She's good to me and she cracks jokes and I can laugh with her. But at home I somehow always feel miserable. […]

N.Y.: Arda, do you think people at home don't take you seriously?

Arda: No, not taking me seriously at all. Somehow, nobody really listens to me at all. Everybody's talking with each other and amongst each other. But my sister takes me seriously. She's also taking care of me. She asks me how I am, and tries to make me laugh and so … (He smiles, himself, thinking about it.) […]

Arda: I know I felt worse the last few days, worse than I did a few days ago. Going out didn't do me any good. I want to see my sister, she's simply good to me. Also, I can speak with her in my own mother tongue. Can you tell me if I could pay my debts from Southern Tyrol, too? Or what kind of work I could do there? […]

N.Y.: Well, let's finish our talk for today and we'll meet again tomorrow, since you've got music therapy now.

Arda: Oh yes, that right. Good, thank you very much, Ms. Yilmaz, for talking just with me alone. It's done me a lot of good, and so I think I'll look for a psychiatrist in Southern Tyrol as well, because I think that it's important. (He shakes my hand and we say goodbye, as he leaves the room with a smile.)

When the Work Discussion seminar leaders read the excerpt they discussed with reference to ‘Dimension 1’ whether a lively and dense interaction process in the form of consecutive sequences of activities has been described in detail. Concerning this, they were asking whether, while reading the report, a lively picture arises in the imagination which gives an idea of a sequence, like watching a film. Their response was:

Well, this is not the case: The author cut some parts of the dialogue. Getting a detailed imagined picture of the interaction between Arda and the author is, not least because of that, impossible.

Regarding ‘Dimension 3’ the seminar leaders assessed whether the author had developed comprehensible thoughts, about the impact of explicitly described inner processes in the reported behaviour of all persons described in the report, with special respect to emotions and affect regulation. Did the description of inner states of mind in the report make it possible to understand in what respects they had influenced the described behaviour?

The seminar leader concluded that the author’s comments did include thoughts about feelings, emotions, wishes and intentions. But at the end of the first term, these comments were precise only at a rather limited level of reference. They did not show in what respects the described behaviour could be understood to be the result and expression of inner activities and processes.

Regarding ‘Dimension 4’ the seminar leaders discussed whether the author had focused, again step by step, the impact of the behaviour of each person on the emotional state of all the other people who were present in the described situation. This was in order to take into account the specific way each person influenced in detail the course of the interaction. The seminar leaders found some comments which were in accord with ‘Dimension 4’ in the first paper of the author. However, those comments were not developed sequentially or systematically.

3.3.2. The assessment of Paper No 4

When the seminar leaders read the author’s fourth paper written at the end of the fourth term, they recognized with delight the extent to which the quality of the paper had changed for the better. The author quoted from a Work Discussion report of a group session she was conducting:

N.Y.: Well then, Mr. J., what's your impression about the group? How would you assess this particular group?

Mr. J.: I find it interesting and I feel quite well here.

N.Y.: Yes, that's important and nice that you feel comfortable in the group, and it increases the motivation to collaborate. But my question was, because you were saying earlier, that discussions displayed social competence. How would you assess this group?

Mr. J. (laughing): Ms. Y., don't try to get me to say that this group is naughty. I won't say it.

N.Y.: No, look, Mr. J., I asked you how you would assess this group.

Mr. J.: No, I won't say that the group is bad. […]

The broader context of this dialogue is not known and therefore grasping its entire meaning is not easy. Nevertheless, we do get information about consecutive activities. A sequence similar to the plot of a film can be read, according to ‘Dimension 1’.

When the author refers her analysis, she presents her comments step by step linked to the sequence of reported activities. She again quotes from her report, dwelling on each contribution to the procedure of the described interaction separately in the sense of ‘Dimension 2’.

Furthermore the author makes it clear, according to ‘Dimension 3’, the respect in which the described behaviour can be understood as a result and expression of explicitly mentioned internal activities and processes. At the beginning of her analysis she is quoting, and by that means, focussing on the reported question she addressed to Mr. J.:

Well then, Mr. J., what's your impression as an outsider? How would you assess this particular group?

I ask myself why I put this question directly to Mr. J. My impression is that I value his assessment. For one thing, I know him well, and for another, he is cognitively more in touch than some of the other participants. So my expectation was that I'd receive an ‘objective’ assessment from him.

Another reason for asking an individual member a direct question is that if I just toss a question to the whole group, the group will tend to discuss matters in a disorganized way. Listening to one another and taking turns to talk doesn't seem to work in this group. This is why I address one person specifically, to avoid having all the others chime in as well.

While writing this paragraph I am overcome by the fantasy that I am disappointed by this group, because they haven't fulfilled my expectations. But since I'm conscious of the situation of the participants, namely, that many of them have short attention spans and experience difficulties in learning, I start to wonder if I am not perhaps expecting too much of them. Maybe that's why I try to repress my anger and disappointment. I want to guide Mr J., but also the other participants, through loaded questions and discussions, to arrive at placing themselves in my shoes and so to understand me better. Do I expect more empathy from this group? Do I want them to understand me, as I understand them? Well, at least I experience disappointment and anger, as I reread the sentence. Among other things, I'm unhappy with the way I start the sentence, with that hard little phrase, ‘Well then!’ It sounds pretty serious.

I find it interesting and I feel quite well here.

Although our summary of these considerations is a little more structured than the author’s own text, there is no doubt that the author is discussing explicitly the impact of the behaviour of each acting person on the emotional state of the other person in the sense of ‘Dimension 4’. By doing this she is also now highly reflective regarding her own role in this interaction.

3.4. Some final remarks

We want to conclude by focusing on three points:

Assessing seminar papers in the way we described and looking for the development of mentalizing capacities according to the outlined ‘Dimensions 1–4’ give information from a particular point of view about the acquisition of psychoanalytic skills and attitudes. The mentalizing capacities (and activities) described here are necessary preconditions for working with a psychoanalytic approach. This approach includes, for example, the development of thoughts concerning dynamic unconscious activities and processes and the explicitly use of countertransference in the ‘here and now.’

The author’s ‘Paper 4’ includes some passages with considerations concerning dynamically unconscious activities and processes, and the definitions of the ‘Dimensions 1-4’ have to be extended and specified if we have to become able to assess papers from the perspective of the development of particular psychoanalytic skills and attitudes.

We noted a remarkable change had taken place from the author’s ‘Paper 1’ to ‘Paper 4’. We do not suggest that this kind of development can be found in all seminar papers of all participants. But we are convinced that analysing seminar papers in this way is of interest and value.

By analysing a seminar paper in this way, we do not obtain information which has validity in establishing whether changes were the result of the specific experience of Work Discussion, for the author and her subjects were at the same time engaged in parallel training activities (e.g. seminars, training analysis, work placement). Taking this into consideration it will be necessary to extend and refine our research methodology.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Dr Wilfried Datler is Professor at the University of Vienna, where he is running the research unit ‘Psychoanalysis and Education’ at the Department of Education and psychoanalytic-oriented Master's degree programmes at the Postgraduate Centre. He is a training analyst of the Austrian Association of Individual psychology (ÖVIP) and a member of the Infant Observation Study Group Vienna (IOSGV).

Dr Margit Datler is Professor at the University College of Teacher Education Vienna/Krems and is a Lecturer at the University of Vienna. She is a Psychoanalyst (IPA) and a member of the Infant Observation Study Group Vienna (IOSGV).

Dr Michael Wininger is Assistant Professor at the ‘Department Psychotherapy’ of the Bertha von Suttner Private University St. Pölten (Austria), Psychoanalyst in private practice and Lecturer at the University of Vienna.

Notes

* An earlier version of this paper was given at the ‘First International Conference on Work Discussion’ which took place at the University of Vienna in June 2016 (see Klauber, Citation2016; Rustin & Pollard, Citation2018). Many thanks to Michael Rustin for essential comments and Trudy Klauber for significant contributions to the final version of the paper.

1 An analogous investigation of English publications is planned with special respect to papers about Work Discussion published in the journal ‘Infant Observation’ and in books edited by Rustin and Bradley (Citation2008) and Armstrong and Rustin (Citation2015).

2 In Austria, Work Discussion is also taught in other Bachelor's and Master’s degree programmes. See e.g. Diem-Wille, Steinhardt, and Reiter (Citation2006) and Hover-Reisner, Fürstaller, and Wininger (Citation2018).

3 Datler, Geiger, and Datler (Citation2011). For more information see: https://www.postgraduatecenter.at/weiterbildungsprogramme/bildung-soziales/integration-von-kindern-und-jugendlichen-mit-emotionalen-und-sozialen-problemen-im-kontext-von-schule/

4 Members of the teaching staff decide on the basis of an interview about the admission of interested teachers to the programme. If a group of about 25 experienced teachers have finished the programme after three years, the programme starts with a new group of about 25 teachers.

5 ‘Psychagogue’ is a term in particular used in Vienna to give a professional title to those students who have qualified in the way here described (Wagner-Deutsch, Citation2017, p. 30).

6 For further information see Gstach et al. (Citation2015) and https://www.postgraduatecenter.at/weiterbildungsprogramme/gesundheit-naturwissenschaften/fachspezifikum/

7 Many thanks to Mary Target who discussed the modification during her stay as a visiting professor at the University of Vienna.

8 In ‘Programme B’ four Work Discussion seminars took place. In the first semester, each seminar was run by two seminar leaders. All seminar leaders – Edith Bayer, Barbara Lehner, Gerhard Pawlowsky, Christine Rosner, Irmgard Sengschmied, Peter Zumer, Margit and Wilfried Datler – assessed all seminar papers written at the end of each of the first four semesters of the programme.

9 We want to express our thanks to Narin Yilmaz for giving us permission to quote from her seminar papers.

References

- Allen, J. G., Fonagy, P., & Bateman, A. W. (2008). Mentalizing in clinical practice. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric.

- Armstrong, D., & Rustin, M. J. (Ed.). (2015). Social defences against anxiety. Explorations in a paradigm. London: Karnac.

- Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (Eds.). (2019). Handbook of mentalizing in mental health practice. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric.

- Bevington, D., Fuggle, P., Cracknell, L., & Fonagy, P. (2017). Adaptive mentalization-based integrative treatment. A guide for teams to develop systems of care. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Datler, W. (2004). Wie Novellen zu lesen … : Historisches und Methodologisches zur Bedeutung von Falldarstellungen in der Psychoanalytischen Pädagogik [It’s like reading short stories … : Historical and methodological comments on the importance of case studies in psychoanalytic pedagogy]. Jahrbuch für Psychoanalytische Pädagogik [Yearbook of psychoanalysis and education 14] (pp. 9-41). Gießen: Psychosozial-Verlag. Retrieved from https://www.univie.ac.at/bildungswissenschaft/papaed/seiten/datler/Artikel/111_Wie_Novellen_zu_lesen%20a.pdf

- Datler, W., & Datler, M. (2014). Was ist „Work Discussion“? Über die Arbeit mit Praxisprotokollen nach dem Tavistock-Konzept [What is „Work Discussion“? The discussion of reported work situations according to the Tavistock Model]. University of Vienna: Phaidra. Retrieved from https://services.phaidra.univie.ac.at/api/object/o:368997/diss/Content/get

- Datler, W., Geiger, B., & Datler, M. (2011). Grundzüge der psychagogischen Ausbildung in Wien – Das Lehrgangskonzept [Essentials of the education of psychagogues in Vienna – The basic concept of the programme]. heilpädagogik / Fachzeitschrift der Heilpädagogischen Gesellschaft Österreich [Special Education / Journal of the Austrian Association of Special Education], 54(4), 2–6.

- Datler, W., Katschnig, T., & Wagner-Deutsch, X. (2019). Teachers’development of psychoanalytic skills and attitudes: The impact of Work Discussion on professional education from the vista of participants (draft title.) In preparation.

- Diem-Wille, G., Steinhardt, K., & Reiter, H. (2006). Joys and sorrows of teaching infant observation at university level – implementing psychoanalytic observation in teachers’ further education. Infant Observation, 9(3), 233–248. doi: 10.1080/13698030601070656

- Elfer, P., Greenfield, S., Robson, S., Wilson, D., & Zachariou, A. (2018). Love, satisfaction and exhaustion in the nursery: Methodological issues in evaluating the impact of Work Discussion groups in the nursery. Early Child Development and Care, 188(7), 1–13. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2018.1446431

- Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, E., & Target, M. (2002). Affect regulation, mentalization, and the development of the self. New York, NY: Other Press.

- Fonagy, P., Target, M., Steele, H., & Steele, M. (1998). Reflective-functioning manual. Version 5.0 for Application to adult attachment interviews. London: University College London.

- Freud, S. (1895). Fraulein Elisabeth v. R. In J. Breuer & S. Freud (Eds.), Studies on hysteria. Translated from the German and edited by James Strachey in collaboration with Anna Freud. (Reprint of Volume II of the Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud.) London: Hogarth Press, 1955, pp. 135-183.

- Gstach, J., Bisanz, A., Datler, W., Pawlowsky, G., Schipflinger, S., Tomandl, C., … Zumer, P. (2015). “Soll die Psychoanalyse an der Universität gelehrt werden?” Zur Einrichtung des Lehrgangs “Psychotherapeutisches Fachspezifikum: Individualpsychologie und Selbstpsychologie” an der Universität Wien [Is psychoanalysis to be taught at university? On the occasion of the Master’s degree programme “Psychotherapy: Individual Psychoology and Self Psychology”]. Zeitschrift für Individualpsychologie [Journal of Individual Psychology], 40(2), 136–149. doi: 10.13109/zind.2015.40.2.136

- Hartland-Rowe, L. (2016). Lost in translation: The application of a psychoanalytic framework through Work Discussion. Unpublished paper presented on June 11, 2016, at the First International Conference on Work Discussion, University of Vienna.

- Hesse, E. (1999). The adult attachment interview: Historical and current perspectives. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment (pp. 395–433). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Hover-Reisner, N., Fürstaller, M., & Wininger, A. (2018). ‘Holding mind in mind’: The use of work discussion in facilitating early childcare (kindergarten) teachers’ capacity to mentalise. Infant Observation, 21(1), 98–110. doi: 10.1080/13698036.2018.1539339

- Klauber, T. (2016). First international conference on Work Discussion in Vienna from 10 to 12th June 2016: Let’s talk about work! Work Discussion in practice and research. Infant Observation, 19(2), 171–175. doi: 10.1080/13698036.2016.1229211

- Rustin, M. E., & Bradley, J. (2008). Work Discussion. Learning from reflective practice in work with children and families. London: Karnac.

- Rustin, M. J., & Pollard, L. (2018). Introduction to the symposium on Work Discussion. Infant Observation, 21(1), 48–56. doi: 10.1080/13698036.2018.1540124

- Schöck, D. (2018). Lernprozesse in der Work-Discussion. Eine systematische Untersuchung von deutschsprachigen Publikationen über die Darstellung von Lernprozessen in Work-Discussion-Seminaren [Formation processes in Work Discussion. A systematic investigation of German publications on the presentation of learning processes in Work Discussion seminars] (Master’s theses). The research unit, Psychoanalysis and Education, Department of Education of the University of Vienna.

- Sengschmied, I. (2017). Emotion – Lehrerhandeln – Lehrerbildung. Ein psychoanalytisch-pädagogischer Beitrag zur Diskussion über Standards in der Lehrerbildung und zum „Wissen-Können-Problem“ [Emotion – teachers‘ actions – teacher education. A psychoanalytic-pedagogical contribution to the discussion of standards in the formation of teacher education and the knowledge-tacit-problem] (Doctoral thesis). Faculty of Philosophy and Education of the University of Vienna.

- Slade, A. (2005). Parental reflective functioning: An introduction. Attachment and Human Development, 7(3), 269–281. doi: 10.1080/14616730500245906

- Slade, A., Aber, J. L., Berger, B., Bresgi, I., & Kaplan, M. (2005). Parent Development Interview Revised (PDI-R2). Unpublished manuscript.

- Turner, A., & Ingrisch, D. (2009). Erfahrungslernen durch die psychoanalytische Beobachtungsmethode. Auf dem Weg zu einer neuen Lernkultur? - Über das Verstehen der eigenen Emotion und der von SchülerInnen aus der Perspektive von LehrerInnen [Learning by experience by the use of the psychoanalytic model of observation. Towards a new culture of learning? - About understanding of own emotions and emotions of pupils from the perspective of teachers]. In G. Diem-Wille, & A. Turner (Eds.), Ein-Blicke in die Tiefe. Die Methode der psychoanalytischen Säuglingsbeobachtung und ihre Anwendungen (pp. 157–181). Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

- Wagner-Deutsch, X. (2017). Eine Evaluation des Universitäts- und Hochschullehrgangs zur Ausbildung von Psychagoginnen und Psychagogen in Wien: Welche Elemente werden von den Absolventinnen und Absolventen als besonders wertvoll erachtet und wie wird dies begründet? [An evaluation of a Master’s degree programme dedicated to the education of psychagogy in Vienna: Which programme elements are considered as particular valuable by former participants and which reasons do they give?] (Master’s theses). The research unit “Psychoanalysis and Education”, Department of Education of the University of Vienna.

- Wininger, M. (2017). The Reflective Functioning in Vocational Training-Interview (RFVT-I). Unpublished manuscript.