ABSTRACT

Despite a growing interest in posthuman research methodologies within educational research, there has been limited research to date which applies this theory to music education. We consider that there is much that posthumanism and music education may offer each other, particularly within the context of the global COVID-19 pandemic which challenges us to innovate rapidly within our educational and research practices. We explore the potential of this methodology through conducting a ‘diffractive analysis,’ an approach to enquiry associated with posthuman theory. Drawing on data collected during a participatory music project involving children with SEND [Special Educational Needs and Disabilities], professional musicians, trainee generalist primary teachers and ourselves as facilitators and researchers, we draw out the potential of a diffractive analysis by putting it into dialogue with a thematic analysis of the same data. In documenting this we describe our own process of co-becoming as researchers, entangled with our research and our data. We describe the research processes that we followed, and through a comparison of materials produced during our initial analysis, we consider the similarities, differences and conversations that emerge.

Introduction

There is a growing interest in posthuman research methodologies within educational research (Snaza and Weaver Citation2014; Taylor and Hughes Citation2016; Taylor and Gannon Citation2018). Situated within the ‘ontological turn’ (Bodén et al. Citation2019), and also described as new materialist or post-qualitative (Lather and Pierre Citation2013), these research approaches emphasise difference, decentre the human, and attend to the vitality of matter, both human and nonhuman (Bennett Citation2010). To date there is limited research which applies this theory to music education (Woods Citation2019, Citation2020); we consider that posthumanism and music education have much to offer each other. Posthuman theories emphasise pluralities and difference, drawing our attention to all of the musical and material participants (e.g. sounds, bodies, spaces, instruments) in our co-creativities (Hickey-Moody and Page Citation2016). Similarly, in music making in education, we seek to enter into non-hierarchical musical dialogues with not only human but sonic, spatial and instrumental participants. In this moment of global crisis where digital technology has become a co-participant in all our interactions – bringing us together as much as it emphasises our distance – engaging with new ways of viewing pedagogical and musical spaces seems ever more pressing (Camlin and Lisboa Citation2021).

To explore this potential we present a dialogue between two approaches to analysing data collected following a participatory music project embedding live performance within teacher education. We begin with an interpretive thematic analysis of qualitative responses to a questionnaire and interview, and move to a diffractive analysis of the same data set. Diffractive analysis is characteristic of posthuman research, following work by Haraway (Citation2000), Barad (Citation2007) and Mazzei (Citation2014) all of whom propose diffraction as an alternative to the more common research metaphor of reflection. In documenting this dialogue we are seeking to open up space for new thinking, informed by Bakhtin’s (Citation1981) conception of the dialogic imagination, within which ‘the dialogic orientation of a word among other words (of all kinds and degrees of otherness) creates new and significant artistic potential in discourse’ (275). In this case we orientate not words but research methodologies, following a precedent set by Bozalek and Zembylas (Citation2017), who consider diffraction and reflection as different research practices by ‘putting the two practices in conversation, delving more deeply into their continuities and breaks’ (117). Our dialogue is situated specifically within the experience of researching in music education; by engaging with the entanglement of ourselves and our methodologies, we reflect the dialogic approach that lies at the heart of our pedagogy as music educators (Alexander Citation2017; Camlin Citation2015).

The research that we discuss explores a partnership project between a national music outreach programme, two musicians, three SEND (special educational needs and disabilities) schools, staff and trainee generalist Primary teachers [trainees] at an English university, and ourselves – Ursula and Hermione – as project facilitators and researchers. From the outset we acknowledge our embedded, embodied involvement in the research: Ursula as a PhD researcher and former programme director for the partner music organisation, Hermione as a former lecturer on the primary teacher training course involved. We therefore draw attention to the contrasting starting positions we can adopt as reflexive interpretivists located in the world and as posthumanists intra-acting as part of the world. As interpretive researchers, we start from a subjective epistemological position, reflexively locating our positionality in the world (Pillow Citation2003). As posthuman researchers, we adopt the concept of intra-acting with/in our research from Barad (Citation2007). Intra-action articulates the idea that individuals, or ‘distinct entities … do not precede, but rather emerge from/through their intra-actions’ (Barad Citation2007, 33). We are in a constant process of intra-acting with, and therefore co-becoming with, our research. As we intra-act with our data in our diffractive analysis – re-discovering it as data-objects, asking it questions and listening carefully with all our senses for its response – we reject the idea of ourselves as in any sense ‘observers’, external to the world we see around us. Instead, we embody Barad’s onto-epistemology, becoming ‘part of the world in its ongoing intra-activity’ (185). Through placing the two analyses next to and in dialogue with each other, we allow these differences of onto-epistemological position to co-exist through the article, remaining attentive to what may emerge from the conversation.

This article therefore focusses on a dialogue between two approaches to data analysis; in documenting this we also describe our own process of co-becoming as researchers. We describe the specific application of these approaches to research in a music education context, and therefore also acknowledge the entanglement of live music in our research. Since the research has taken place in the unprecedented context of the COVID-19 pandemic, we also acknowledge the place of the virus in our conversation, causing its own diffraction of our research, and continuing to produce disruption and difference.

A music project

Trainee generalist teachers’ confidence to teach music is frequently low, for well-documented reasons which it is beyond the scope of this article to examine, but include prior musical experiences (Henley Citation2017), musical identities and self-concepts (Draves Citation2021), gaps in pedagogical and content knowledge (Atkinson Citation2018), and limited opportunities provided during training (Biasutti, Hennessy, and de Vugt-Jansen Citation2014). One area that we felt had the potential to address some of these issues was access to live music and an understanding of how children might engage with experiencing both performances and partnership working. We wanted to offer trainees an opportunity to engage with their musical selves as co-participants with children in a live musical experience, deciding to bring children, trainees, and musicians together in a ‘strong experience’ (Gabrielsson Citation2011) of shared live performance that hopefully would inspire them to seek out such opportunities in their developing careers as teachers. The project also allowed us to address some of the trainees’ preconceptions about ‘classical’ music, since the musicians involved came from a classical background and performed repertoire by Shostakovitch, Mozart and Elgar.

Integrated within the trainees’ pedagogy and subject knowledge curriculum, the music project took place over two days in October 2019. 88 trainees participated in group workshops introducing partnership working and focusing on how they as teachers could make best use of the opportunities afforded by visiting professional musicians. The sessions were run in partnership with the music lecturer, a project facilitator and two musicians. Each worked with the students through practical music making including aspects of performance, creative engagement through listening and exploration of instruments, and group work on basic musical skills including pulse, rhythm and dynamics. The professional musicians were integrated into the activities throughout, in turn leading and working alongside the students. This material was extended into a concert on each day which was attended by 27 children and 10 members of staff from three local special schools, alongside the trainee teachers. This gave the trainees the opportunity to see the interactions between children, staff, music and musicians at first hand. Concert repertoire included classical music and arrangements of well-known popular music; echoing the workshop content, the musicians engaged the audience imaginatively in listening and joining in with practical games that explored different aspects of the music presented. There were also a wealth of more informal interactions such as dancing, singing (both invited and spontaneous), and conversation, and children were supported by their teachers to respond freely to the music throughout.

Data collection

Planning the project initially as a pilot for future partnership work, our research was focussed on exploring trainees’ and performers’ perceptions of experiencing the workshops and live performances, and exploring what kinds of learning those participants felt that they had gained from the experience. Our intention was to draw on the findings to inform our subsequent development of the partnerships involved.

We situated our research at the data collection stage within a constructivist paradigm (Denzin and Lincoln Citation2011), acknowledging our subjective filtering of the material but hoping to foreground the participants’ experiences (Pring Citation2004). In order to capture as broad a range as possible of student experiences whilst making the process straightforward, we designed an online questionnaire, administered during teaching time in the week following the project; 75 out of the 88 students completed the questionnaire.

The first section of the questionnaire aimed to capture students’ prior musical experiences to give context to their responses, using questions based on those Hermione had previously used to guide planning and delivery of sessions with similar cohorts of students. The main body of the questionnaire explored how the students had experienced the workshop and performance, particularly in terms of their status as beginning teachers; we asked about pedagogical approaches, and impacts on themselves and their future practices as teachers. Unstructured interviews (Barbour and Shostak Citation2011) were conducted with the two performers on the second day of workshops and performances and a reflective diary was also produced by Ursula, who co-led the taught sessions. Ethical permission for the research was granted by the University ethics committee, participation was voluntary, and all of the participants gave written informed consent prior to taking part.

Conducting a thematic analysis

Our initial approach to data analysis embodied Peshkin’s (Citation2000) characterisation of interpretation in qualitative enquiry as ‘an act of imagination and logic’ (9), using thematic analysis (Gibson and Brown Citation2009) and informed by constant comparison (Butler-Kisber Citation2010). Taking a ‘flexible, iterative, [and] naturalistic’ (Gibson and Brown Citation2009, 8) approach, we did not commence the analysis with a pre-defined coding schema, but adopted a data-driven approach (Gibbs Citation2007). We began by scanning the results of our questionnaire and interview transcription, looking for notable text, ‘pre-coding’ (Saldaña Citation2009, 16) and allowing ourselves to engage with the concert and workshop again through the eyes of the participants. We inevitably played a strong role in the research ourselves, acting in an interpretive way from the outset, considering multiple meanings that could be suggested or developed from the data, informed by our own positionality in the field and specific roles in the project under consideration (Peshkin Citation2000).

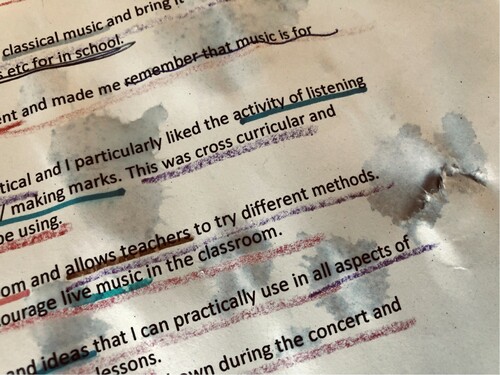

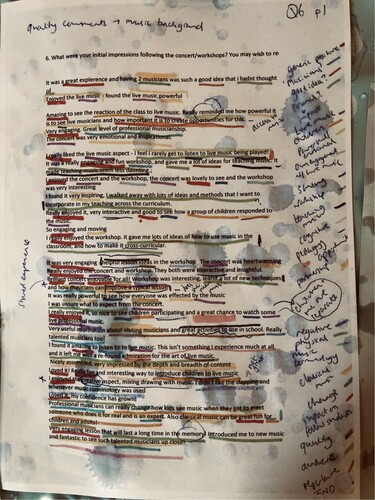

We then moved to a more granular approach, producing a range of descriptive codes, categories and analytic codes (Gibbs Citation2007). We looked for these codes concurrently, using an approach derived from simultaneous coding (Saldaña 2009) to allow us to engage with the richness of the data. There was a slowness to this experience: using hard copies of the data and coloured pens borrowed from Ursula’s children, we engaged deeply with the text, lingering over individual words and teasing out meanings, implications and connections. Our engagement with the data was embodied and playful; we enjoyed choosing different colours to highlight, underline and comment, and frequently stopped to express our joy at the success of the project as captured by the students’ and musicians’ words.

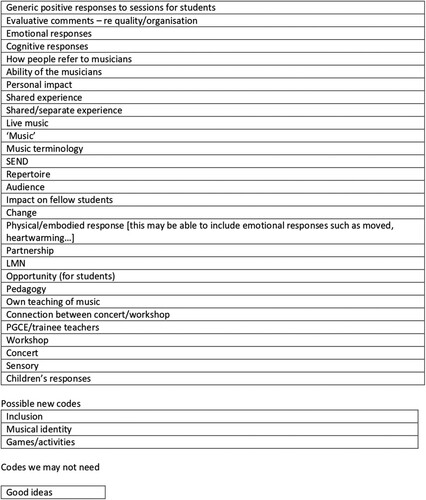

These codes were then grouped into initial themes (Saldaña 2009); as can be seen from , this remained a work in progress.

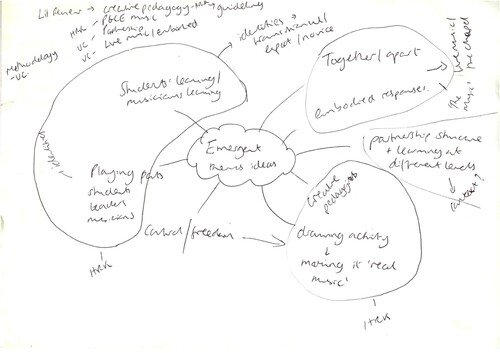

We began the process of grouping these initial themes into larger over-arching themes; Hermione’s sketched mind-map, , captures our thoughts at this stage in the analysis process.

Our initial findings from our thematic analysis reassured us that some of our intentions for the project – to communicate the powerful potential of experiences of live music for children – had been successful. There is no need to restate well-rehearsed arguments here (for example, Hallam Citation2015), but we were pleased to achieve this goal of the project. Our findings were grouped around three thematic areas, each of which suggested potential for further exploration in research and practice. Overarching thematic groupings at this first stage of analysis were:

Together-apart

Identities

Creative pedagogies

Together-apart: Trainees talked about the sense of togetherness they felt at hearing live music performed alongside children. Responses were described in embodied, visceral, emotional terms – for themselves as audience, and for the children present. Emerging from the data though was also a feeling of separateness – between the trainees, ‘the music’ and the ‘musicians’, and also between the trainees and the children as witnesses to the live performance. This latter sense may have the potential to reinforce ideas both of teacher-pupil and musician-teacher hierarchical relationships (Partington Citation2018), and it would be worthwhile exploring how partnership work of this kind between ITE providers and music outreach organisations could directly seek to reconsider these relationships.

Identities: Reflections also emerged on trainees’ musical identities and transitional/emergent teacher identities (Pellegrino Citation2019). Participants in the project played the part of student, of trainee teacher, of musician – parts which were varyingly new or familiar to them, and sometimes overlapped, sometimes were separated by (perceived) hierarchical relationships. We also observed the notion of expert and novice – yet transitional – musical and pedagogical identities. The trainees identified themselves as in the process of becoming teachers, and noticed how this musical experience might impact on their past and future conceptions of themselves of musicians. An earlier vision for this project had involved more extensive collaborative work, which would have provided further opportunities for role switching, in particular between musicians and trainee teachers: we consider that there is now potential to explore this further within the partnership model that we have developed.

Creative pedagogies: A further strand running through the data related to the creative pedagogies used during the workshop part of the project. Trainees responded particularly positively to an activity where they were asked to draw in response to a piece of music, drawings which then were used as a ‘score’ for them to play from, alongside the musicians. Several trainees mentioned this activity when asked about their strongest memory of the day. They talked about their drawings as scores, and themselves as composers and creative collaborators. It was not until we asked this question (the tenth in the questionnaire) that this activity was mentioned so frequently, which caused us to reflect on this as an example of the ‘together/apart’-ness of the trainees and musicians. The experience here seemed to be of togetherness in creating and playing but also of a sense of separation from ‘the musicians’. We reflected further on whether this activity chimed in particular with the trainees because it made their musical ideas ‘real music’. This finding points towards potential insight to be found in investigating further the integration of emerging teacher identity, partnership practice and creative pedagogies (Cremin and Chappell Citation2019; Hall and Thomson Citation2017).

Conducting a diffractive analysis

The idea of ‘diffraction’ in research is taken from the work of Barad (Citation2007, 73) who describes a ‘diffraction apparatus’ as a device that intervenes and entangles itself in research, producing and highlighting difference. It contrasts with the metaphor of reflection, often used in qualitative research, with its emphasis on representations of reality. Diffraction in physics is a process that occurs when waves encounter an obstruction, for example parallel ocean waves passing through a narrow gap and spreading out in a different pattern (Barad Citation2007). Similarly, diffractive research is about a researcher ‘entering the assemblage’ and producing what Mazzei (Citation2014, 743) describes as ‘multiplicity, ambiguity, and incoherent subjectivity’. Our process of coding the data had led us to search through it for patterns and similarities. Re-engaging with it diffractively, we were looking for ways to meet with the data differently, and to stay attuned to the differences that might emerge.

Diffraction 1

23 March 2020: across the UK the first COVID 19 lockdown began. Stuck at home in different parts of the country, with varying pressures and responsibilities, our research came to a stop. Despite good intentions to revisit the data and to use the time to prepare an article, weeks passed and the data gradually collected dust. Events were cancelled, and larger projects than this one were postponed or simply abandoned. Considering the data and thematic analysis was like returning to a vanished world: bringing groups of students, musicians and school pupils together now seemed impossible for the foreseeable future. The original premise for our research – to develop and learn from a live music partnership project – seemed irrelevant. The global COVID-19 pandemic inveigled itself uninvited into our research, changing the nature of our data, our research process, and ourselves as researchers. As such, we came to understand COVID-19 itself as a diffraction of our research data; an enforced awakening to a new reality where we had less control, and less of a central position than we at first thought within our research. In subsequent diffractions, taking place from June 2020 onwards, we took a more active role in meeting our data, yet the pandemic remained entangled in the process and products of our emerging research: a difference had emerged that we couldn’t undo.

Diffraction 2

In the next diffraction of our data, we engaged in particular with the work of MacLure (Citation2013), specifically her concept of a ‘glow moment’. MacLure describes this as an ‘occasion when one becomes especially “interested” in a piece of data’ (660); ‘the detail that arrests our gaze and makes us pause; the connections that start to fire up; the conversation that gets faster and more animated’ (662). We understood this as allowing particular aspects or moments within the data to invite our attention, to call to us, and to provoke questioning. Reviewing the data, our attention was quickly drawn to an extract from the interview conducted with the two musicians immediately following the last of the project workshops.

Also the students’ responses to the concerts, I was really shocked at that [yeah] to see students – the amount of people who said they got emotional, I never expected that, and I don’t know why because I felt quite like a little bit emotional [you do, don’t you] – and you just …

What do you think it was that made them kind of have that, because it was really noticeable, a lot of them said they had tears in their eyes and talked about kind of having an emotional connection with the music, um …

I think it’s seeing it not through, like not on video, not on like in some article, it’s seeing it live, happen, it’s seeing children having a lovely time doing something they don’t often do

Yup

And then you’ve got the music on top of it which is always emotional anyway, or emotive

And I also think it’s surprising how easy it is to sort of get that reaction, like I think if you see it on the TV or something, because we’re constantly watching things where they say ‘oh, music’s very valuable, you need to protect it, music in schools’ and I think until you actually see it you think oh, they’re just picking out the best bits but actually that reaction is pretty standard for music.

I felt quite like a little bit emotional [you do, don’t you] – and you just …

What do you think it was that made them kind of have that, because it was really noticeable, a lot of them said they had tears in their eyes

A series of questions and ‘wonderings’ emerged from this process, for example:

Sense in which ‘affect’ still moving through interview data

How do students place themselves in relation to music/ to their students? What questions are their tears raising for this?

What is the agency of tears in the data?

How are the tears materialising a relationship with the children watching the concert?

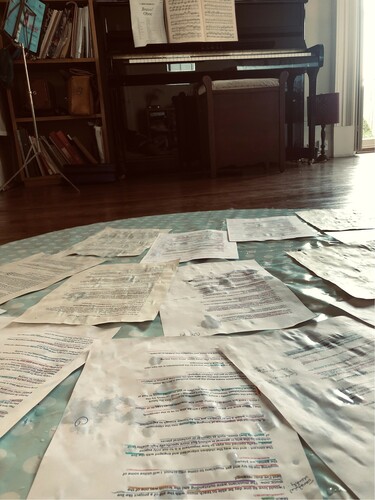

Apparent from this diffraction was an opening up of some surprising questions that, although tangential, seemed to be bringing some understandings to our research that were different from those that appeared from the thematic analysis. Hoping to pursue this, we decided to investigate one of our questions further, intentionally selecting a question that we felt it was unlikely we would have come to through our thematic analysis. The question that emerged for further investigation between ourselves and our data was ‘what is the agency of tears in the data’? We drew here on Koro-Ljungberg’s (Citation2016, 45) work on ‘data-wants and data entanglements’ in which she encourages us to consider our relationship with data, paying attention to how data might ‘take or provoke action’ (46), changing the dynamics of the data-researcher relationship. We considered also Renold and Ringrose’s (Citation2019) art-ful practices, in which they bring arts-informed action/activism and data together to craft what they term ‘da(r)taphacts’ – more-than-human materialities that trouble our ideas of data, carry affect, and move us on from ‘fixed, knowable and measureable social science facts.’ Giving ourselves permission to shift from given data to crafted ‘da(r)taphact’, and considering the action that our data seemed to provoke, we therefore thought about how we might introduce more tears to our data set. Laying out multiple pages from the thematic analysis and interviews, we splashed the pages with water that had been lightly coloured to represent tears, as shown in .

Two extracts from the data became the basis for further exploration through subsequent diffractions:

Diffraction 3

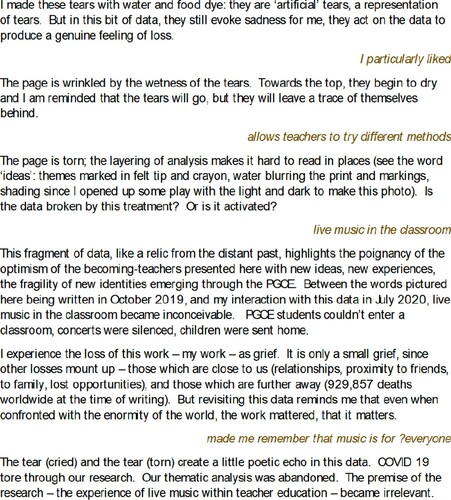

For diffraction 3, Ursula considered the question ‘what is the agency of tears in the data?’ by attending closely to the data extract shown in , considering its materiality and her own embodied, affective response. In this, she was drawing again on Koro-Ljungberg (Citation2016), and in particular her invitation to consider how data creates or changes researchers: acknowledging the affect of the data on herself as a recognition of this process in action. She cut her own writing together with textual extracts from the data, allowing the two to continue to interact, as shown in .

Diffraction 4

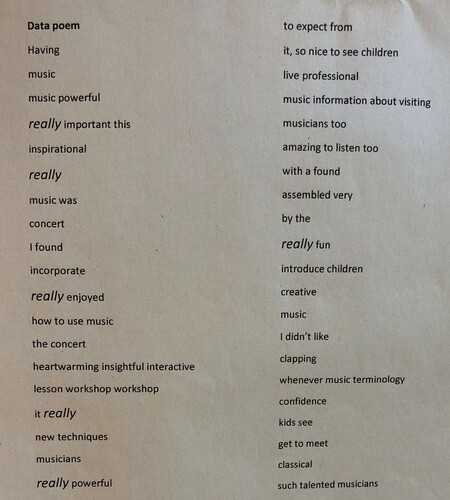

In diffraction 4, we attempt to move further away from the notion of data as awaiting human interpretation and sense making (Taylor and Gannon Citation2018). We respond to Koro-Ljungberg, MacLure, and Ulmer’s (Citation2018) comments on normalising human-centred research processes, which they critique for constraining what may be potentially productively ‘troubling’ aspects of data. presents a data poem as it appeared as a ‘found object’ from the data set: it has been (re)produced by typing the words that were selected by the ‘tears’ introduced to the data set (see ).

Conversing

Bozalek and Zembylas (Citation2017, 124) describe diffraction as ‘a tool of analysis, for attentive and detailed reading of a text intra-actively through another for the consequential differences that matter’. As we now put our processes of thematic and diffractive analysis more directly into conversation, we are searching for ways to read one through the other, looking for these ‘consequential differences that matter’. We proceed with this differential reading, acknowledging that our relationship with both qualitative and posthuman research has been complex and porous, an ongoing entangled performance of research. As we encountered our data as thematic analysts, we pondered deeply over our interpretations. As we encountered our data again in the spirit of posthuman explorers, we rediscovered our print-outs, notes and drawings as artefacts of our earlier process of researching. We began to re-engage with these artefacts as actants in their own right, seeing them not as somehow ‘representing’ the experience of the music project, but as new entities which we met with curiosity.

Considering similarity

To place our data in conversation, we therefore started from the material documentary data we had produced – what we had begun to characterise as the data objects emerging from our ‘research machine’ (Stenliden, Martín-Bylund, and Reimers Citation2018). Sitting down to explore these data objects, we were drawn to Hermione’s list of codes with handwritten annotations () and Ursula’s data poem (), as the similarity of their form on the page jumped out. We put them next to each other on the floor and considered how they spoke to each other, or how each commented on the other. We were struck initially by the similarity of their content: this was surprising, given the extremely different processes that had led to their creation. One seemed rigorous while the other seemed playful, but our initial impression was of similarity.

The data gave us a feeling of zooming in and zooming out. The juxtaposition of fragments of text in the data poem retains the character of the teardrop – distorting but also magnifying moments from the data.

In the fragment illustrated in , we saw similarity to well-rehearsed themes in the literature about the lack of confidence that generalist primary teachers report in their subject knowledge for music (Hennessy Citation2018). A sense of an audience was also evoked by the word ‘clapping’. Perhaps the tears were distorting the original data here, where clapping referred to clapping games, and confidence belonged to a comment by a different student. But the sense we had ‘magnified’ by the tear was one of discomfort around terminology and performativity.

Zooming out with the list of codes allowed us to see similar themes emerging in the bigger context of the project, the list also serving to highlight the multifaceted nature of the project, its complexity, and the range of participants’ responses.

Considering difference

Considering the points of divergence in more detail, we went back to the artefacts and identified several differences in what they communicated. For example, a clear message from the thematic analysis was the importance of shared experience, which seemed silent in the data poem.

We also began to characterise the coding artefact as informational, whilst the data poem felt emotive and immediate. This also reflected our interactions with the two data objects: we felt that the coding artefact was transmitting information to us, whilst the poem emphasised an ambiguity and incompleteness which seemed to invite us into a dialogue. A sense of an individual ‘author’ of the poem, full of vulnerability and the freshness of their response to the experience, also came through. In , we get the sense of how the importance of music was palpable in the poem, as was a sense of urgency with the repeated word ‘really’ (see the full poem, ).

Considering connections

We reflected on the way one document enabled the other. In a literal sense, the data poem was created by manipulating the coded data, but in a broader representation of the evolution of research methodology, our playful engagement with the materiality of the data had been enabled by a series of challenges to the orthodoxy of educational research. By allowing the dialogue between the two documents, we did not find the documents, or the research processes, incompatible. Rather, we found that they enabled different kinds of knowledge of the data, each of which may be considered a valid knowledge. Although we have described our sense of zooming out through the thematic analysis and zooming in with the diffractive analysis, this did not imply a limitation to the micro in the latter, but rather a concern with the particularity of difference and how this may change our perspective.

Our own connection with the data and with the music project was reawakened through our renewed interaction with the data. Returning to the data poem we noticed the dialogue between the beginning and end sections, shown in , which encapsulated something about how we conceptualised and experienced the project.

In one sense we had set out to provoke this response from the students – we wanted them to experience that music is powerful, important and inspirational. Experiencing the project alongside them, and through the series of diffractions of the data, we were surprised to reconnect with this sense for ourselves. Cooke (Citation2020, 406), reflecting on the relationship between music education, research and posthumanism, positions the researcher and teacher as ‘living in and with the learning, not judging and assessing from the side-lines’. We experienced this engagement with the music as a productive aspect of working with posthuman approaches to music education. Moving to the final segment of the poem though, we noticed a less comfortable response which raised questions for us. The sense coming through this text is that the experience is for the children – not the trainee teachers – to see and meet the musicians. The final two fragments (‘classical’ and ‘such talented musicians’) seem to suggest a feeling of separateness highlighting the sense in which students were both ‘together’ in the music, but also ‘apart’ from the ‘talented musicians’.

An unending

We draw together here some strands of our dialogue between research methodologies, ourselves and our data, and what we find in the new spaces which this process opened and continues to open up. We challenged ourselves to engage with the data in a less-representational way – allowing the data objects produced during the thematic analysis to enter the research assemblage as actants in their own right. Alongside this, we have engaged in a detailed textual analysis. We have found ourselves inhabiting a liminal space between the two approaches to inquiry, oscillating between the two: we analyse, we generate different data and interact with it, we interpret and analyse again, we invite pieces of data into the article intact, so that they might act in their own way on our writing.

When we ask where the research has taken us, we don’t find a conclusion, but rather a dynamic entanglement of ourselves in two different processes of research and of two different processes of research with each other. We acknowledge ourselves embedded in both practices: in our qualitative researching we continue to concern ourselves with representation of our data, which we mediate through our research positionality. As we venture into posthuman practices we observe the data in a still more entangled process of becoming with ourselves as researchers (Stenliden, Martín-Bylund, and Reimers Citation2018) – separate but together, and both implicated in the other.

During this research we have taken some steps from the safe space of qualitative research into the more unknown territory of posthumanism. Solnit (Citation2005, 5), reflecting on the experience of the unknown, suggests that whilst scientists ‘transform the unknown into the known, haul it in like fishermen; artists get you out into that dark sea’. This is evocative for us of our research process, particularly as it has played out during the ongoing pandemic. It has reminded us that inhabiting the unknown space can be productive in its discomfort. Posthumanism invites us to engage with this difference, change and uncertainty (Chappell Citation2018), viewing the emergent dialogue as a driver of new musical/creative processes.

As we look forward through the unknown development of the pandemic, we are part of a community of music educators, rapidly considering new ways of producing simple moments of musical connection through the complexities and distances of new technologies and socially distanced educational practices. In considering the dialogue between qualitative and posthuman methodologies, we hope to have opened up further spaces to explore how these practices might work; COVID-19 imposes new materialism upon us, with the digital space overwhelming the physical, and we hope to have shown how we might embrace the potentiality afforded by a posthuman lens upon a rapidly changing ‘reality’.

We recall working with the trainees on the music project. Debriefing after the concerts, trainees reflected on their own experience of the live music and asked whether it was acceptable as a teacher to be personally moved or to show their emotional responses (the ‘tears in their eyes’). This echoes our feelings of entering an unplanned, unknown space as we have conducted our research, revealing our own affective responses to the experience, particularly as we have considered the dialogue between qualitative and posthuman methods. Live performance has acted as a space both for the trainees and for us as researchers to get out into the ‘dark sea’, to move away from curriculum and from prescribed research methods, towards a more open ended, emergent, felt engagement with our work.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the support of the Wellcome Centre for Cultures and Environments of Health for initial project work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ursula Crickmay

Ursula Crickmay is currently studying for a PhD at the University of Exeter, in which her research focus is on posthuman theory and creative music workshop practices. She also teaches at the University of Exeter on the Creative Arts in Education MA programme. Her professional background is in developing and managing creative learning programmes with artists and arts organisations. Ursula studied music, and community music, at the University of York.

Hermione Ruck Keene

Hermione Ruck Keene taught Music in Primary schools for several years before completing a PhD in Sociology of Music. She has been working in ITE and Creative Arts Education since 2014, at the universities of Exeter, Reading, Brunel, Oxford Brookes and Cumbria. Hermione has worked on transdisciplinary arts/science research projects as well as developing her own research into musical identities and participation.

References

- Alexander, R. 2017. Towards Dialogic Teaching: Rethinking Classroom Talk. Thirsk: Dialogos.

- Atkinson, R. 2018. “The Pedagogy of Primary Music Teaching: Talking About Not Talking.” Music Education Research 20 (03): 267–276. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2017.1327.

- Bakhtin, M. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglements of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Barbour, R. S., and John Shostak. 2011. “Interviewing and Focus Groups.” In Theory and Methods in Social Research, edited by Bridget Somekh, and Cathy Lewin, 61–68. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Biasutti, Michele, Sarah Hennessy, and Ellen de Vugt-Jansen. 2014. “Confidence Development in Non-music Specialist Trainee Primary Teachers After an Intensive Programme.” British Journal of Music Education 32 (02): 143–161. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265051714000291.

- Bodén, Linnea, Hillevi Lenz Taguchi, Emilie Moberg, and Carol A. Taylor. 2019. “Relational Materialism.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education, July 29. Accessed July 22, 2021. https://oxfordre.com/education/view/https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-789.

- Bozalek, Vivienne, and Michalinos Zembylas. 2017. “Diffraction or Reflection? Sketching the Contours of Two Methodologies in Educational Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 30 (2): 111–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2016.1201166.

- Butler-Kisber, Lynn. 2010. Qualitative Inquiry: Thematic, Narrative and Arts-Informed Perspectives. London: Sage Publications Limited.

- Camlin, Dave. 2015. “‘This Is My Truth, Now Tell Me Yours’: Emphasizing Dialogue Within Participatory Music.” International Journal of Community Music 8 (3): 233–257. doi:https://doi.org/10.1386/ijcm.8.3.233_1.

- Camlin, David A., and Tania Lisboa. 2021. “The Digital ‘Turn’ in Music Education.” Music Education Research 23 (2): 129–138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2021.1908792.

- Chappell, Kerry. 2018. “From Wise Humanising Creativity to (Post-humanising) Creativity.” In Creativity Policy, Partnerships and Practice in Education, edited by Anne Harris, Kim Snepvangers, and Pat Thomson, 279–306. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cooke, Carolyn. 2020. “On Methodological Accounts of Improvisation and “Making with” in Science and Music.” In Why Science and Art Creativities Matter: (Re-)Configuring STEAM for Future-Making Education, edited by Pamela Burnard, and Laura Colucci-Gray, 402–422. Leiden: Brill.

- Cremin, Teresa, and Kerry Chappell. 2019. “Creative Pedagogies: A Systematic Review.” Research Papers in Education 36 (3): 299–331. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2019.1677757.

- Denzin, Norman, and Yvonna Lincoln. 2011. “The Discipline and Practice of Qualitative Research.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualititative Research, edited by Norman Denzin, and Yvonna Lincoln, 1–32. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Draves, Tami. 2021. “Exploring Music Student Teachers’ Professional Identities.” Music Education Research 23 (1): 28–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2020.1832059.

- Gabrielsson, Alf. 2011. Strong Experiences With Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gibbs, Graham. 2007. Analysing Qualitative Data. London: Sage Publications Limited.

- Gibson, William, and Andrew Brown. 2009. Working with Qualitative Data. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Hall, Christine, and Pat Thomson. 2017. “Creativity in Teaching: What Can Teachers Learn from Artists?” Research Papers in Education 32 (1): 106–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1144216.

- Hallam, Susan. 2015. The Power of Music: A Research Synthesis of the Impact of Actively Making Music on the Intellectual, Social and Personal Development of Children and Young People. London: Institute of Education University College.

- Haraway, Donna. 2000. How Like a Leaf: An Interview with Thyrza Nichols Goodeve. New York: Routledge.

- Henley, Jennie. 2017. “How Musical are Primary Generalist Student Teachers?” Music Education Research 19 (4): 470–484. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2016.1204278.

- Hennessy, Sarah. 2018. “Improving Primary Teaching: Minding the Gap.” In Music and Music Education in People’s Lives, edited by Gary McPherson, and Graham Welch, 265–269. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hickey-Moody, Anna, and Tara Page, eds. 2016. Arts, Pedagogy and Cultural Resistance: New Materialisms. London: Bowman and Littlefield.

- Koro-Ljungberg, Mirka. 2016. Reconceptualizing Qualitative Research: Methodologies without Methodology. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Koro-Ljungberg, Mirka, Maggie MacLure, and Jasmine Ulmer. 2018. “D … a … t … a … , Data++, Data, and Some Problematics.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by Norman K. Denzin, and Yvonna S. Lincoln, 462–484. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Lather, Patti, and Elizabeth St Pierre. 2013. “Post-Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 26 (6): 629–633. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788752.

- MacLure, Maggie. 2013. “Researching without Representation? Language and Materiality in Post-Qualitative Methodology.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 26 (6): 658–667. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2013.788755.

- Mazzei, Lisa. 2014. “Beyond an Easy Sense: A Diffractive Analysis.” Qualitative Inquiry 20 (6): 742–746. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800414530257.

- Partington, Julia. 2018. ““Ideal Relationships”: Reconceptualizing Partnership in the Music Classroom Using the Smallian Theory of Musicking.” In Musician–Teacher Collaborations: Altering the Chord, edited by Catharina Christophersen, and Ailbhe Kenny, 159–170. London: Routledge.

- Pellegrino, Kirsen. 2019. “Music Teacher Identity Development.” In The Oxford Handbook of Preservice Music Teacher Education in the United States, edited by Colleen Conway, Kristen Pellegrino, Ann Marie Stanley, and Chad West, 269–294. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Peshkin, Alan. 2000. “The Nature of Interpretation in Qualitative Research.” Educational Researcher 29 (9): 5–9.

- Pillow, Wanda. 2003. “Confession, Catharsis, or Cure? Rethinking the Uses of Reflexivity as Methodological Power in Qualitative Research.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 16 (2): 175–196. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839032000060635.

- Pring, Robert. 2004. Philosophy of Educational Research. London: Continuum.

- Renold, Emma, and Jessica Ringrose. 2019. “JARring: Making Phematerilaist Research Practices Matter.” MAI: Feminism and Visual Culture, 4. Retrieved January 29, 2022, from https://maifeminism.com/introducing-phematerialism-feminist-posthuman-and-new-materialist-research-methodologies-in-education/Saldaña.

- Saldaňa, Johnny. 2009. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Snaza, Nathan, and John Weaver, eds. 2014. Posthumanism and Educational Research. New York: Routledge.

- Solnit, Rebecca. 2005. A Field Guide To Getting Lost. Edinburgh: Canongate Books.

- Stenliden, Linnéa, Anna Martín-Bylund, and Eva Reimers. 2018. “Posthuman Data Production In Classroom Studies – a Research Machine Put to Work.” Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology 9 (2): 22–37. https://journals.oslomet.no/index.php/rerm.

- Taylor, Carol, and Susanne Gannon. 2018. “Doing Time and Motion Diffractively: Academic Life Everywhere and all the Time.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 31 (6): 465–486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2017.1422286.

- Taylor, Carol, and Christina Hughes, eds. 2016. Posthuman Research Practices in Education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Woods, Peter. 2019. “Conceptions of Teaching in and Through Noise: A Study of Experimental Musicians’ Beliefs.” Music Education Research 21 (4): 459–468. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2019.1611753.

- Woods, Peter. 2020. “Reimagining Collaboration Through the Lens of the Posthuman: Uncovering Embodied Learning in Noise Music.” Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy 18 (1): 45–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15505170.2020.1786747.