ABSTRACT

Environmental Assessment is a globally mandated tool for helping to deliver sustainable development, yet decision makers frequently use it to legitimise trade-offs between socio-economic gains and environmental losses. As a result, environmental assessment is frequently criticised for its inability to prevent incremental environmental degradation. However, new frameworks stipulating what can be deemed as ‘sustainable investment’ or ‘sustainable economic activity’ for financing under sustainable finance frameworks are being developed. These are known as taxonomies of sustainable investments, and they have the potential to radically change the environmental outcomes of decision making, based on a ‘significant contribution’ and ‘do no significant harm’ approach to critical environmental components. We illustrate how they can change the mindset for the sustainable development expectations associated with policy tools like environmental assessment. Further, we demonstrate that emerging taxonomies can benefit from integration with existing environmental assessment systems. Conversely, an appropriate use of taxonomies of sustainable investments in environmental assessment systems can further strengthen the existing EA systems and allow them to better address the environmental sustainability priorities of the 21st century.

1. Introduction

In 1969, the United States Congress passed the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) (Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America Citation1969) which required all Federal agencies to submit detailed statements when deciding on proposed actions that may significantly affect the quality of the human environment. The process up to, and including, the preparation and consultations on these statements later became known as Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and marked a radical departure from traditional practices that were mainly based on checklists, guidebooks, and procedural manuals that did not support integrated environmental decision-making (Caldwell Citation1988).

NEPA gave an inspiration to other countries and international development agencies that begun developing their own EIA systems. Currently, EIA systems are present in all countries in the world as the formalized decision-support tools for helping to deliver sustainable development (Bond et al. Citation2020). Over 60 countries also used lessons from EIA systems to establish Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) systems that addresses the environmental impacts of plans, programmes and sometime also strategies and policies (International Atomic Energy Agency Citation2018).

However, now, 50 years after the passage of NEPA, the ability of EIA to support sustainable development and protect the environmental bottom lines is increasingly questioned in terms of continuing impacts to, in particular, biodiversity, climate, and water. Growing concern over the continuing loss of biodiversity (Pereira et al. Citation2010; Hooper et al. Citation2012; Cardinale et al. Citation2012; Sandbrook et al. Citation2019) has led to questions over the ability of EIA to prevent incremental loss (Bond et al. Citation2021) and to increasing policy requirements to deliver biodiversity no net loss, or even net gain to try to redress the losses (Brownlie and Botha Citation2009; BBOP – Business and Biodiversity Offsets Program Citation2012; Bull and Strange Citation2018). Similar arguments are played out in the context of climate change, with strong evidence of increasing threats to the environment (Rockström et al. Citation2009; McGlone Citation2021; Masson-Delmotte et al. Citationin Press) allied to a failure of EIA (or SEA) to prevent this (Wende et al. Citation2012). EIA processes have also been criticized for their limited consideration of long-term trends and cumulative impacts that are required in sustainable water management (Jiang Citation2015; UNESCO Citation2019; Jenkins Citation2020). On top of these specific concerns about the ability of EIA to deliver specific environmental protection objectives, it is also under threat in some jurisdictions because of perceived or real inefficiencies (Bond et al. Citation2014).

While some of these issues are being resolved with more stringent assessment instruments, we would like to draw the attention of the EIA professional community to a rapidly advancing development of taxonomies of green projects or sustainable activities (hereafter collectively termed as taxonomies of sustainable investments). These frameworks are being developed in various jurisdictions to define ‘green’ or ‘sustainable’ for major institutions and corporations involved in sustainable finance. The recent commitments of over $130 trillion of private capital to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050 at the latest made within the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (Citation2021) can well illustrate the scale of systemic implications that taxonomies of sustainable investments may have on the existing – or should we perhaps say former? – environmental decision-making systems.

This paper assumes that taxonomies of sustainable investments have a power to significantly influence EIA and SEA systems globally. It uses an example of the recent EU Taxonomy for sustainable investments and seeks to investigate: i) what do the evolving taxonomies imply for the evolving understanding of environmental sustainability? And ii) what are their implications for future evolution of EIA systems that serve as the tool of choice for informing sustainable decision-making since the 1992 Earth Summit (United Nations Citation1992)?

To answer these questions, in the next section we introduce the concept of taxonomies of sustainable investments and presents the main requirements of the EU Taxonomy, which is often perceived as the current global benchmark in this field (Bloomberg Citation2021). This is followed by an analysis of the potential for this Regulation to deliver a shift in mindsets that could signal an end to the incremental loss of environmental capital that continuing development currently causes (Fang Citation2022; Fanning et al. Citation2022). The fourth section considers the role EIA can play in implementing the new Taxonomy. Finally, we consider the next steps; that is, what needs to happen in order for the EU Taxonomy to deliver a change in mindsets, and what role might EIA play in this?

2. Introduction to taxonomies of sustainable investments

Taxonomies of sustainable investments are a specific tool within the broad family of various approaches that try to align financial investments with climate and other sustainability goals and encompass diverse arrangements ranging from Environmental, Social and Governance rating methodologies, to benchmarks and verification and certification schemes (SFWG Citation2021). While all these tools should in the future follow the voluntary principles for international coordination in this field defined at G20 level (see Box 1), taxonomies try to articulate what ‘green investments’ or ‘sustainable activities’ mean in very detailed terms. By so doing, they aim to bring clarity into fragmented markets, improve the reporting on sustainable finance, and facilitate policy and regulatory actions in this field (OECD Citation2020).

Box 1. High-level principles for aligning approaches and international coordination on sustainable finance

Green taxonomies originate back to the first ‘taxonomy’ launched by the Climate Bonds Initiative in 2012, followed by two different green bond endorsed project catalogues by the People’s Bank of China and China’s National Development and Reform Commission (Tripathy et al. Citation2020). In 2016, the European Commission decided to develop a European ‘Taxonomy’ which in 2019 culminated in the European Union Regulation 2020/852 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate (environmentally) sustainable investment, commonly referred to as the EU Taxonomy for sustainable activities (European Union Citation2019). In the meantime, other jurisdictions, such as Japan, India, South Africa, France, Kazakhstan and Indonesia have either developed or are currently formulating their own taxonomies that are often inspired by the basic framework used in the EU Taxonomy (OECD Citation2020, OECD Citation2017). In addition, taxonomies of sustainable investments are being regularly revised – as demonstrated, e.g., by the example of the 2021 Edition of the Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue by the People’s Bank of China (PBC Citation2021). Jones et al. (Citation2021) observed that, by October 2021, ‘more than 30 taxonomies outlining what is and isn’t a green investment are being compiled by governments across Asia, Europe and Latin America, each one reflecting national economic idiosyncrasies that can jar with a global capital market which has seen trillions pour into sustainable funds’.

Given the EU’s soft but influential regulatory power (Bradford Citation2015), the EU Taxonomy became the most debated taxonomy within the international finance community (Bloomberg Citation2021). At the most fundamental level, it defined common criteria for determining whether a given economic activity is environmentally sustainable or not. And when doing so, it moved beyond mechanistic listing of environmental-friendly activities and spelled out six policy environmental objectives where improvements need to be achieved in order to advance environmental sustainability:

climate change mitigation;

climate change adaptation;

the sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources;

the transition to a circular economy;

pollution prevention and control;

the protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems.

Using the backbone of the above environmental objectives, the EU Taxonomy declared that an economic activity can be recognized as sustainable if it:

makes a substantial contribution to at least one of these environmental objectives;

does no significant harm to any other environmental objectives;

complies with minimum social safeguards; and

complies with technical screening criteria established by the European Commission through so-called Delegated Acts.

The basic criteria for determining whether the activity substantially contributes to the above environmental policy objectives are defined in Articles 10–15 of the Taxonomy. Article 17 of the EU taxonomy stipulates that an activity cannot be treated as sustainable if it would impede the other environmental objectives from being achieved. The determination of the potential significant harm at the same time requires a holistic consideration covering both the environmental impact of the activity itself but also of the environmental impact of the products and services provided by that activity throughout their life. In other words, any assessment whether the activity can significantly harm any headline environmental objectives needs to adopt a life-cycle approach and consider the full range of direct and indirect impacts of the activity, its products and services over their lifespan – e.g. the production, use and end of life. See Box 2 and Box 3 for examples of Taxonomy requirements for climate change mitigation and biodiversity protection.

Box 2. Selected provisions of the taxonomy: climate change mitigation

Box 3. Selected provisions of the taxonomy: protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems

Following the issuance of the Taxonomy, the European Commission developed so-called Delegated Acts that define technical screening criteria specifying core parameters of ‘sustainable economic activities’ that make a substantial contribution to a given environmental objective without significantly harming the other objectives. These criteria aim to support sustainability-related disclosure by all entities offering financial products on EU financial markets: asset managers, institutional investors, insurance companies, pension funds, and financial advisers in all investment processes.

The EU Taxonomy is also being gradually phased into various EU policy initiatives – such as the future EU Ecolabel criteria for financial products and the EU Green Bond Standard. Other EU operations – such as the Recovery and Resilience Facility which provides over $800 billion to EU member states and the EU Regional, Cohesion and Social funds include references to the ‘do no significant harm principle’ within the meaning of EU Taxonomy Regulation. In addition, the European Commission foresees that companies, investors and project promoters can use the EU Taxonomy criteria as an input to their environmental and sustainability transition strategies and plans. They can also use the EU Taxonomy criteria in their due diligence or choose to meet the criteria of the EU Taxonomy with the aim of attracting investors aiming to achieve a positive environmental impact (European Commission 2021b).

Lastly, while the US currently does not plan to prepare its own taxonomy of sustainable investments, some analysts (Farmer and Thompson Citation2020) expect that US investors may use the EU Taxonomy to gauge whether an investment contributes to an ‘environmental objective,’ such as climate change mitigation or adaptation.

3. A new paradigm for environmentally sustainable development?

In 2019, the International Association for Impact Assessment (IAIA) ran its annual international conference based on the theme of: Evolution or Revolution: where next for Impact Assessment? The journal Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal published a special issue in 2020 (Volume 38, Issue 2) which drew on this conference and asked what the future of impact assessment should look like (Bice and Fischer Citation2020), and also highlighted the need for impact assessment to better protect the environment (Therivel Citation2020). Based on an understanding that ‘Evolution sees the gradual development of organizations, practice, and systems from simple to more complex forms’, whereas ‘Revolution represents a dramatic and wide-ranging shift to an entirely new paradigm’ (International Association for Impact Assessment Citation2019), the following arguments set out why we feel the advent of Taxonomies of sustainable investments represent a revolution in thinking.

Even a quick glance at the EU Taxonomy reveals that it has created an ambitious and innovative framework for assessing positive and adverse environmental impacts of economic activities. We argue that the EU Taxonomy changes the current sustainable development narrative towards one that:

does not allow trade-offs between the environmental, social and economic capital by placing emphasis on the need for development to ‘do no significant harm’ (DNSH) (see, for example, European Commission Citation2021a);

puts emphasis on the need for the positive contribution of development.

The EU Taxonomy aims to define sustainable economic activities in very clear terms that do not allow environmental trade-offs and aims to protect critical environmental capital. This marks a potentially major shift in mindsets over how sustainable development is conceived in practice. In order to illustrate this argument, below we conceptualise ecological versus economic framings of sustainable development, and explain where the Taxonomy, and the current EIA processes, fit in.

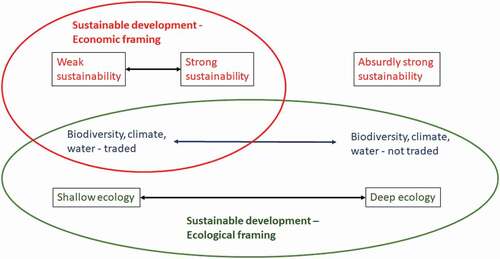

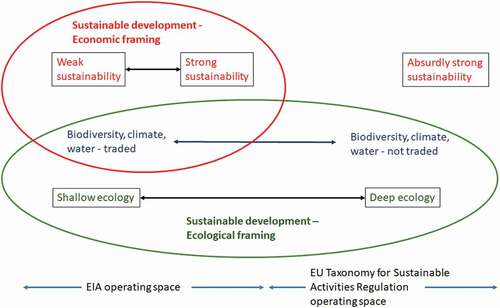

illustrates the difference between economic and ecological framings of sustainable development, illustrating the limits to environmental protection afforded by an economic framing. In , protection of biodiversity to a level where no species goes extinct is labelled as ‘absurdly strong sustainability’ after Daly et al. (Citation1995), which points to a mindset where environmental capital should never stand in the way of development. Bond et al. (Citation2021) have argued that EIA has been interpreted as fitting an economic framing for sustainable development, such that environmental losses can be traded against economic gains. Whilst an economic framing for strong sustainability resists the loss of environmental capital to transfer to future populations, it can facilitate this through offsetting environmental loss for one component against gains in another, which can lead to continuous degradation in key environmental stock elements like biodiversity. Bond et al. (Citation2021) argued that this framing facilitates incremental environmental losses, and global analyses seem to suggest that social advancement continues to take place at the expense of the environment (Fang Citation2022; Fanning et al. Citation2022). The ‘do no significant harm’ policy frameworks that are likely to mushroom around the word following the adoption of the G20 Sustainable Finance Roadmap can be subject to this same interpretation of the acceptability of trade-offs, leading to accusation of ‘greenwashing’.

Figure 1. The failure of an economic discourse on sustainable development to protect the environment. Adapted from Bond et al. (Citation2021)

An ecological framing, and deep ecology specifically, does not accept ecological losses under any circumstances. This framing aligns much more closely with the Taxonomy in resisting the labelling of development as sustainable where any biodiversity, climate, or water metrics are threatened by financial investments (see ). This represents a change in mindset related to interpretations of sustainable development from an economic framing to a more ecological framing. One which protects the bottom line.

Figure 2. Operating space for EIA and EU taxonomy for sustainable activities regulation in the context of sustainable development framings.

Bond et al. (Citation2020) have argued that policymakers and industry have embraced EIA precisely because it facilitates trade-offs and provides a legitimising vehicle for environmentally destructive projects (see ). In identifying impacts and providing evidence to decision makers, it not only highlights environmental loss, it also provides the evidence that facilitates the trade-offs for socio-economic gain, thereby operating within the economic framing boundaries for sustainable development outlined in .

Moreover, the weak sustainability focus that has been the basis for many EIA systems, and that is only concerned with the total sum of economic, social and environmental capital regardless of the balance between the three components, does not acknowledge that healthy ecosystems are a critical foundation for effective and lasting economic development.

This change in emphasis related to sustainable development framing has the potential to deliver a change in mindset related to the role of EIA. Where sustainable development is defined as protecting the bottom line, rather than simply facilitating trade-offs in the name of economic development, there are implications for the way that significance is interpreted within EIA (potentially raising the bar such that any losses become highly significant). At the same time, this can potentially lead to a much increased emphasis on the ability of EIA to facilitate a positive contribution of development in a highly efficient way. This is because EIA is already a legal process worldwide. Capacity therefore already exists to undertake the necessary assessments and inform sustainability ratings under the Taxonomy.

However, there are still risks of poor application, especially when it comes to the DNSH principle. If some elements of the Taxonomy, particularly in the application of DNSH would be deployed softly or without due verification, the environmental contributions of the taxonomy to averting the progressing environmental degradation may be significantly reduced as has happened in various ESG systems (Yu et al. Citation2020; Gyonyorova et al. Citation2021). This could represent a slide back towards an economic framing for sustainable development, which is a worry not only for NGOs (e.g. Atici Citation2021) but also for the key actors in prudent banking practices. For instance, an advisory material on taxonomy prepared by an influential Bank for International Settlements (Ehlers et al. Citation2021, p.19) suggests that a high-quality and consistent verification process will be critical for mitigating the risk of greenwashing that falsely asserts favorable placement within a taxonomy and advises that ‘supervisors and regulatory authorities should provide uniform standards of conduct for the providers of certification and verification services. Ex post assessment of performance should also be conducted’.

Obviously, the aim to ‘limit “greenwashing”’ is a core objective of the EU Taxonomy (Cornillie et al. Citation2021, p.3). In this regard, a question arises as to whether EIA or SEA systems will be used for verification of Taxonomy-related information. And if so, how exactly EIA will fulfil such a role? This question is important because EIA is already applied globally to better understand the implications of potentially harmful developments, and there are both overlaps between EIA application and the scope of financing projects subject to the emerging taxonomies. Whilst this has practical ramifications, it also extends further since the gradual evolution of taxonomies may have important implications for the future development of EIA systems, recognising that the efficiency of any environmental policy innovation is likely to be highly contested.

4. Potential linkages between taxonomies of sustainable economic investments and EIA systems

With any environmental policy or legislation, there remains a question about the benefits that will accrue ‘if the parties lack the ability to comply’ (VanDeveer and Dabelko Citation2001, p.19). Any new environmental policy imposed on a jurisdiction creates a need for capacity development, to establish systems where they did not previously exist and to make these systems operate as intended. Van Loon et al. (Citation2010) highlight the need to develop capacity in terms of resources (tools); technical; scientific; human; organisational; and institutional. This all takes considerable time and resources, much of which can be bypassed through integration with EIA practice. This benefits not just the new taxonomies, but also presents a solution for long-called for improvements to EIA practice. The rapidly evolving taxonomies of sustainable economic investments basically offer an integrated and holistic framework for environmental scrutiny of proposed investments that satisfies earlier calls for EIA practice to shift its focus towards environmental sustainability assurance. This can ensure a substantive contribution to the goal of sustainable development. For instance, the International Study of the Effectiveness of Environmental Assessment proposed to move towards ‘the use of EA as a sustainability assurance (rather than an impact minimization) mechanism’ (Sadler Citation1996, p.iv) and lift standards of EIA practice gradually and pragmatically through a better focus on environmental bottom lines to ensure natural capacities were not exceeded. This would help to ensure no further loss of high value environmental stock and require compensation for losses to ensure no net loss.

The use of the EU taxonomy could, in particular, facilitate the evolution of the EIA system to make it fit for the realities of the challenges of 21st century as it needs to better protect the environment. This essentially means that EIA has to be used in a decision context that embraces ‘do no significant harm’ rather than facilitating trade-offs.

The basic linkages to EIA systems are already present. For instance, several criteria guiding the EU Taxonomy implementation – particularly those related to protection of biodiversity and sustainable water management – refer to outcomes of EIA processes. Other criteria (e.g. climate change adaptation) require assessments that may be directly or indirectly linked to EIA processes.

Yet, more could be done since many EIA systems could – after some minor modifications – have the power to easily consider whether the proposed investments meet the requirements of the EU Taxonomy during:

Scoping;

Consideration of alternatives and mitigation and enhancement measures;

Assessing whether and how the proposed activity meets the criteria laid down in the Taxonomy; and

EIA review and issuance of EIA statements.

Beyond these practical uses, more could be done to reposition the role of EIA in environmental decision-making in the new era of sustainable finance frameworks. One can easily envision the situation when future EIA systems directly support discussions on project financing through formal verification on whether the proposed economic activity fits within any given taxonomy of sustainable investments.

However, for this to happen, the current EIA systems need to evolve. First, the regulatory frameworks should either mandate or at least allow the EIA processes to generate certificates of compliance with any relevant taxonomy of sustainable investments where a project seeks financing. By doing so, the EIA systems would generate much needed information of taxonomy-related deliberations that would be properly reviewed, formally certified, and much cheaper to obtain than any information generated by, e.g. advisory or audit companies that support financial market participants or project development process.

Second, the EIA systems should shift focus beyond adverse impacts and risks and proactively explore positive impacts and environmental enhancement aspirations formulated through sustainable finance frameworks. And they should document and ideally certify that positive impacts claimed by the proposed projects are tangible and real.

5. Next steps: Using the Taxonomy to change mindsets in EIA and SEA processes

The EU Taxonomy has created innovative obligations for the financial sector participants that are, in their significance and implications, commensurate to obligations established by NEPA for decision-making processes in the US in 1970.

Similarly to NEPA, the EU Taxonomy focuses on information provision. It has been designed primarily for financial institutions that offer financial products on the European market and requires that these corporate actors (listed companies, banks, insurance companies or other companies designated by national authorities) disclose to what extent the activities that they carry out meet its criteria. While it has been designed primarily for the financial market participants, it may have direct linkages to environmental decision-making systems in the EU and could possibly influence like-minded developments in other parts of the world. We argue that the EU Taxonomy represents a change in mindset in the way sustainable development is understood and, more importantly, applied. This has significant potential to change the way that EIA is used in decision making if it becomes accepted wisdom that ‘do no significant harm’ is the basis for sustainability.

Common sense dictates that there are huge efficiency gains possible, given the need for capacity development, through the use of EIA as the means through which evidence is delivered to operate the emerging taxonomies. Since the EU Taxonomy is set to affect companies well beyond European borders, we invite interested experts and professionals in the EU and beyond to consider whether or not it would be beneficial, feasible and practical to consider the framework obligations laid down in the Taxonomy in EIA systems. Should the EU Taxonomy-related review criteria be found relevant or useful, it may be useful to know what their best entry points into the EIA systems are and how they could be best considered or amended to fit the local contexts in which various EIA systems operate.

The growing environmental pressures and the emerging appetite for reorienting the future investment decision-making to business opportunities associated with the protection of environmental public goods and on prevention of the breakdown in Earth’s life-support systems, create a perfect momentum for such an inquiry. This is a unique opportunity to deliver: the long called-for change to the EIA system – a change in mindsets related to the use of environmental policy instruments in decision-making – highly efficient and effective capacity development for the implementation of taxonomies of sustainable investments. Surely, there is great potential for a win – win – win situation?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Article 17, paragraph 2 of the Regulation (EU) Citation20202020/852 requires such life-cycle approach also in all other remaining determinations of potentially significant harm on the five remaining environmental objectives presented in this paper.

References

- Atici H. 2021. ‘EU taxonomy is greenwashing tactic, say NGOs’. Accessed 2021 Oct 27. https://greencentralbanking.com/2021/04/21/eu-taxonomy-is-greenwash-say-ngos/.

- BBOP - Business and Biodiversity Offsets Program. 2012. Standard on biodiversity offsets. Accessed 2018 Feb 28th. http://www.forest-trends.org/documents/files/doc_3078.pdf.

- Bice S, Fischer TB. 2020. Impact assessment for the 21st century–what future? Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 38(2):89–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2020.1731202.

- Bloomberg. 2021. applying the EU taxonomy to your investments, how to start? bloomberg professional services january 11, 2021. Accessed 2021 Oct 27. https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/blog/applying-the-eu-taxonomy-to-your-investments-how-to-start/.

- Bond A, Pope J, Fundingsland M, Morrison-Saunders A, Retief F, Hauptfleisch M. 2020. Explaining the political nature of environmental impact assessment (EIA): a neo-Gramscian perspective. J Clean Prod. 244:118694. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118694.

- Bond A, Pope J, Morrison-Saunders A, Retief F. 2021. Taking an environmental ethics perspective to understand what we should expect from EIA in terms of biodiversity protection. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 86:106508. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2020.106508.

- Bond A, Pope J, Morrison-Saunders A, Retief F, Gunn JAE. 2014. Impact assessment: eroding benefits through streamlining? Environ Impact Assess Rev. 45:46–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2013.12.002.

- Bradford A. 2015. Exporting standards: the externalization of the EU’s regulatory power via markets. Int Rev Law Econ. 42:158–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irle.2014.09.004.

- Brownlie S, Botha M. 2009. Biodiversity offsets: adding to the conservation estate, or ‘no net loss’? Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 27(3):227–231. doi:https://doi.org/10.3152/146155109X465968.

- Bull JW, Strange N. 2018. The global extent of biodiversity offset implementation under no net loss policies. Nat Sustainability. 1(12):790. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-018-0176-z.

- Caldwell LK. 1988. Environmental impact analysis (EIA): origins, evolution, and future directions. Policy Stud Rev. 8(1):75–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-1338.1988.tb00917.x.

- Cardinale BJ, Duffy JE, Gonzalez A, Hooper DU, Perrings C, Venail P, Narwani A, MacE GM, Tilman D, Wardle DA, et al. 2012. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature. 486(7401):59–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11148.

- Cornillie J, Delbeke J, Vis P, Zeilina L. 2021. ‘Will the EU sustainable finance rules deliver?’, STG Policy Papers, 2021/13: 8.

- Daly HE, Jacobs M, Skolimowski H. 1995. On Wilfred Beckerman’s critique of sustainable development. Environ Values. 4(1):49–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.3197/096327195776679583.

- Ehlers T, Gao D, Packer F. 2021. ‘A taxonomy of sustainable finance taxonomies: principles for effective taxonomies and proposed policy actions. Bank for International Settlements; Accessed 2021 Oct 27. https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap118.pdf.

- European Commission. 2021a. Commission notice: technical guidance on the application of “do no significant harm” under the recovery and resilience facility regulation. European Commission; Accessed 2021 Oct 27. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/c2021_1054_en.pdf.

- European Union. 2019. Regulation (EU) 2019/2088 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2019 on sustainability‐related disclosures in the financial services sector. Off J European Communities. L317:1–16.

- European Union (2020), ”Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 June 2020 on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment, and amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088”, Official Journal of the European Communities, L198, pages 13–43.

- Fang K. 2022. Moving away from sustainability. Nat Sustainability 5:5–6.

- Fanning AL, O’Neill DW, Hickel J, Roux N. 2022. The social shortfall and ecological overshoot of nations. Nat Sustainability 5 . 26–36.

- Farmer A, Thompson S. 2020. The ripple effect of EU taxonomy for sustainable investments in US Financial sector. Accessed 2021 Oct 20. https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2020/06/10/the-ripple-effect-of-eu-taxonomy-for-sustainable-investments-in-u-s-financial-sector/.

- Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero. 2021. Amount of finance committed to achieving 1.5°C now at scale needed to deliver the transition. Accessed 2021 Nov 25. https://www.gfanzero.com/press/amount-of-finance-committed-to-achieving-1-5c-now-at-scale-needed-to-deliver-the-transition/

- Gyonyorova L, Stachoň M, Stašek D. 2021. ESG ratings: relevant information or misleading clue? evidence from the S&P global 1200. J Sustainable Finance Investment. 36 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2021.1922062.

- Hooper DU, Carol Adair E, Cardinale BJ, Byrnes JEK, Hungate BA, Matulich KL, Andrew Gonzalez JED, Gamfeldt L, O’Connor MI, O’Connor MI. 2012. A global synthesis reveals biodiversity loss as a major driver of ecosystem change. Nature. 486(7401):105. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11118.

- Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Pirani A, Connors SL, Péan C, Berger S, Caud N, Chen Y, Goldfarb L, Gomis MI, et al. (ed.) in Press. Climate change 2021: the physical science basis. contribution of working group i to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge).

- International Association for Impact Assessment. 2019. ‘IAIA19 Brisbane Australia. 39th Annual Conference of the International Association for Impact Assessment’, IAIA, Accessed 2021 Nov 29. https://conferences.iaia.org/2019/index.php.

- International Atomic Energy Agency. 2018. Strategic Environmental Assessment for Nuclear Power Programmes: guidelines. IAEA:Vienna.

- Jenkins B. 2020. resilience considerations related to water resource management: the Case of Te Waihora/Lake Ellesmere. IAIA symposium, our interconnected world: impact assessment, health and the environment. Online: IAIA

- Jiang Y. 2015. China’s water security: current status, emerging challenges and future prospects. Environ Sci Policy. 54:106–125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2015.06.006.

- Jones H, Abnett K, Jessop S. 2021. Analysis: investors face myriad green investing rules. Accessed 2021 Nov 29. https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/one-taxonomy-rule-them-all-investors-face-myriad-green-investing-rules-2021-10-19/.

- McGlone C. 2021. Adapt or die’: EA warns people will die unless UK does more to prepare for climate change, Environmental Data Services. Accessed 2021 Oct 13. https://www.endsreport.com/article/1730210/adapt-die-ea-warns-people-will-die-unless-uk-does-prepare-climate-change.

- OECD. 2017. Mobilising bond markets for a low-carbon transition, green finance and investment. Paris: OECD Publishing. Accessed 2021 Nov 24. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264272323-en

- OECD (2020), ”Developing Sustainable Finance Definitions and Taxonomies, Green Finance and Investment”, available at last accessed 27 October 2021.

- PBC. 2021. green bond endorsed projects catalogue (2021 edition). People’s Bank of China; 2021 Apr 21, Accessed 2021 Nov 30. http://www.pbc.gov.cn/goutongjiaoliu/113456/113469/4342400/2021091617180089879.pdf.

- Pereira HM, Leadley PW, Proença V, Alkemade R, Scharlemann JPW, Fernandez-Manjarrés JF, Araújo MB, Balvanera P, Biggs R, Cheung WWL. 2010. Scenarios for global biodiversity in the 21st century. Science. 330(6010):1496–1501. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1196624.

- Rockström J, Steffen W, Noone K, Persson Å, Chapin FS, Lambin EF, Lenton TM, Scheffer M, Folke C, Schellnhuber HJ, et al. 2009. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature. 461(7263):472–475. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/461472a.

- Sadler B. 1996. International study of the effectiveness of environmental assessment final report - environmental assessment in a changing world: evaluating practice to improve performance. Vol. 248. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada.

- Sandbrook C, Fisher JA, Holmes G, Luque-Lora R, Keane A. 2019. The global conservation movement is diverse but not divided. Nat Sustainability. 2(4):316–323. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0267-5.

- Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America. 1969. The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969’, US Government; Accessed 2019 Oct 15. https://www.energy.gov/sites/prod/files/nepapub/nepa_documents/RedDont/Req-NEPA.pdf.

- SFWG. 2021. ‘G20 sustainable finance working group - 2021 synthesis report. 2021 Oct 7, Accessed 2021 Oct 27. https://g20sfwg.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/G20-SFWG-Synthesis-Report.pdf.

- Therivel R. 2020. Impact assessment: from whale to shark. Impact Assess Project Appraisal. 38(2):118–121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14615517.2019.1676070.

- Tripathy A, Mok L, House K. 2020. Defining Climate-Aligned Investment: an Analysis of Sustainable Finance Taxonomy Development. J Environ Investing. 10(1): 80–96 .

- UNESCO. 2019. Water security and the sustainable development goals. UNESCO international centre for water security and sustainable management, Accessed 2021 Oct 15. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3807832.

- United Nations. 1992. Report of the United Nations Conference on environment and development. UNCED Report A/CONF.151/5/Rev.1’, United Nations. Accessed 2021 Oct 13. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_CONF.151_26_Vol.I_Declaration.pdf.

- Van Loon L, Driessen PPJ, Kolhoff AJ, Runhaar HAC. 2010. An analytical framework for capacity development in EIA - the case of Yemen. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 30(2):100–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2009.06.001.

- VanDeveer SD, Dabelko GD. 2001. It’s capacity, stupid: international assistance and national implementation. Global Environl Polit. 1(2):18–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/152638001750336569.

- Wende W, Bond A, Bobylev N, Stratmann L. 2012. Climate change mitigation and adaptation in strategic environmental assessment. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 32(1):88–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2011.04.003.

- Yu EP-Y, Van Luu B, Huirong Chen C. 2020. Greenwashing in environmental, social and governance disclosures. Res Int Bus Finance. 52:101192. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2020.101192.