ABSTRACT

Building upon the interrelationship between learning and changing, this study investigates how cyclical engagement in reflexive practice influences the teachers’ professional development. We implemented our video-enhanced ‘Reflexive Practice Triplication Model’ which we developed in our specific context. We conducted the research with 8 secondary school teachers of English at a private K12 school in Ankara, Turkey. Drawing on multiple sources of data, we used a triangulation technique to reveal the qualitative and quantitative impact of reflexive practice. The findings showed that collaborative engagement in reflexive practice contributed substantially to EFL teachers’ professional development traceable in the changes in beliefs on reflexivity, attitudes towards collaboration, contextual and pedagogical knowledge. The study provides implications as to how reflexive practice can be used in local contexts where specific needs are to be considered.

Introduction

In constantly developing second language education, a well-qualified teacher of English is expected to comply with all the innovations in the field. Although there are numerous studies on pre-service EFL teachers’ engagement in reflective practice (Altalhab et al., Citation2021; Jantori, Citation2020; Karakaş & Yükselir, Citation2020; Yong-jik & Davis, Citation2017), there is a dearth of studies with in-service EFL teachers (Adams, Citation2009; Burhan-Horasanlı & Ortaçtepe, Citation2016; Cholifah et al., Citation2020; Cirocki & Widodo, Citation2019; Hung & Thuy, Citation2021; Moradkhani et al., Citation2017).

Reflexivity comprises constant reflection (Reich, Citation2017) during which research is being conducted and shaping the process (Nadin & Cassell, Citation2006) through the interrelationship between learning and changing (Antonacopoulou, Citation2004). Reflexivity concentrating on self-reference, self-awareness and self-understanding enables teachers to have ‘a better understanding of situations through a better understanding of ourselves’ (Matthews & Jessel, Citation1998, p. 233). Therefore, teachers should identify their needs in teaching by using research diaries or having discussions with fellows (Nadin & Cassell, Citation2006). Also, they should question their actions and values that shape their practices (Cunliffe, Citation2009; Ripamonti et al., Citation2016).

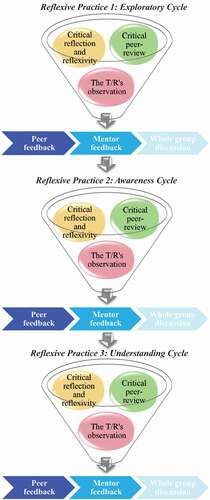

The central problem lies in EFL teachers’ needs for reflexivity and collaboration with colleagues. Therefore, the researchers investigated how the reflexive practice has influenced in-service EFL teachers’ professional development through critical reflective and reflexive reports (RRR), critical peer-reviews (CPR) and focus group discussions (FGD). This study suggests a model which enables in-service EFL teachers to gain insight into reflection upon their teaching within three cycles: exploratory cycle, awareness cycle and understanding cycle. Different from most studies in which reflective practice is held once, the model in the current study was designed as three cycles since one of the challenges of reflective practice is repetitive cycles (Karakaş & Yükselir, Citation2020; Korucu-Kış & Kartal, Citation2019).

This research addresses this gap by revealing the impact of reflexive practice on EFL teachers through video-enhanced observation. To achieve this, we sought the following research questions:

(1) In what ways have the reflexive cycles influenced EFL teachers?

(2) To what extent does the Reflexive Practice Triplication Model enhance EFL teachers’ teaching performances in the classroom?

Literature review

Lately, studies have concentrated on reflection as an essential instrument for change (Avalos, Citation2011). As a crucial part of the cycle of ‘learning from experience’ (Dewey, Citation1933), reflective thought begins when having some difficulties (Mezirow, Citation1991; Rogers, Citation2001) in the classroom. To dispense with the possibility of poor learning outcomes caused by ineffective teaching, teachers should be bound to reflexive thinking. As long as teachers evaluate their teaching recurrently, they can develop deeper insight into their classrooms (Ferraro, Citation2000; Fines, Citation2014).

Becoming a reflexive practitioner

Reflection is a conscious activity to develop new understandings by looking at experiences (Boud et al., Citation1985; Dewey, Citation1933). The idea of reflective teaching (Cruickshank, Citation1987; Schön, Citation1983, Citation1987) helps practitioners ‘learn from experience about themselves, their work, and the way they relate to significant others’ (Bolton, Citation2010, p. 3). Being slightly different from this, reflexivity embraces ‘a reaction occurring immediately in response to something that happens’ (Collins, Citation2004, p. 1206). This process allows us figure out what we do and how we do it. The situation is scrutinized ‘through the eyes of others’ (Bolton, Citation2010, p. 13).

Reflexivity aims to enhance the reflection process; comprising the mental activities in reflective practice and emphasizing ‘the way in which our reflective practice works back in an effectual manner’ (Lisle, Citation2010, p. 222). Through reflexive practice, rather than just focusing on implications, teachers question their practices through a ‘critical lens’ (Fairley, Citation2020, p. 1046), use their own research results (Reich, Citation2017) and become aware of experiences and perceptions of others; which is a reconstruction of experience-based learning as ‘practical reflexivity’ (Cunliffe, Citation2009; Cunliffe & Easterby-Smith, Citation2004).

Collaborative engagement in reflexive practice

Engagement in real-life problems through cooperation and constructing solutions (Freyn et al., Citation2021) enables teachers to become more integrated and goal-oriented (Butler & Schnellert, Citation2012) since professional development is social and interactive in nature. The success of collaborative engagement depends on how well the interaction is (Godínez Martínez, Citation2022) among teachers whose attitudes, beliefs and knowledge are both the determinants of and affected by the process.

Collaborative engagement involving active cognitive processes brings about collaborative skills and knowledge construction (Järvelä et al., Citation2016) with the help of shared reflexivity in which teachers think and work together to sustain professional growth (McArdle & Coutts, Citation2010). This engagement also allows teachers to reveal collaboration challenges and failures in teaching (MacDonald, Citation2011).

Method

Research design and implementation

Based on the empirical data on teacher research, this study settles teachers to act as both individuals and partners, contributing to the process through their knowledge and expertise. In that regard, this participant-oriented research concentrates on the inclusion of individuals with their experiences (Wright & Diener, Citation2020). A predominantly qualitative data-driven methodology was applied with the incontrovertible support of quantitative data analysis. Triangulation technique was used to analyse the data obtained through the interview, RRR, CPR checklists, the teacher/researcher (T/R)’s observation diary, FGD and open-ended questionnaire.

Setting and participants

The current research was conducted in a private K-12 institution in Ankara, Turkey with voluntarily chosen secondary school English teachers (n = 8). During the research, they both collaborated with pairs and worked individually. Not only the participants but also the T/R had specific roles such as collaborative mentoring and cooperative peer work during this research.

Research tools

To inspect language teachers’ awareness of their teaching and to find out their self-identified needs for effective teaching; first, the T/R held a pre-interview to. After a discussion with colleagues about what puzzles them in teaching, the questions were formulated with the help of an expert opinion. The interview was made in the participants’ mother tongue to help them share their emotions and ideas comfortably. Next, the participants wrote critical RRR regarding their videoed practices in light of some guiding questions. The reports were named ‘reflective and reflexive’ since they were applied both after each practice and recurrently during the process. Then, peers evaluated each other using a checklist with 10 items in two domains; classroom management and using instructional strategies and guiding and motivation. This collaborative engagement provided the participants with developing new skills such as peer learning, providing constructive feedback and evaluating their colleagues’ practices without having power over each other. Along with these, the T/R took some observation and FGD notes during and after each cycle. Lastly, an open-ended questionnaire was applied to figure out how efficient the model was and what the participants thought about it.

The trustworthiness of the study

Since this is a mostly qualitative research, trustworthiness (Connelly, Citation2016) is a critical issue. Firstly, we practised member checking (Birt et al., Citation2016; Carlson, Citation2010). All the participants read the transcriptions of their interviews and confirmed the accuracy of the match between what they actually meant and what was written by the T/R. Secondly, we relied on different sources of information and found evidence for themes to maximise triangulation (Creswell, Citation2007) and to increase reliability (Lietz et al., Citation2006; Loh, Citation2013). We provided evidence with some quotes from the data. Having peer-debriefed the emerging meanings during the data analysis to negotiate overemphasized or underemphasized themes (Shenton, Citation2004), we also invited another academic to provide insight into the emerging codes to minimize and avoid potential bias.

In addition, we calculated inter-coder reliability via NVivo. For this calculation, we used one participant’s pre-interview that has the closest number of words to the average. Considering five codes, Kappa coefficient showed that there was a moderate agreement between the coders in classroom management inefficacy (with value .56), curiosity and eagerness to learn (with value .44), desire for personal and professional development (with value .42) and need for collaboration (with value .59) even though there was a fair agreement between the coders in deficiency of guidance and motivation (with value .36).

Data collection

Data were collected from two perspectives: research methods (through the interaction between the participants and the researcher) comprising interviews, observation diary and mentor feedback, and authentic methods (through the interaction among the participants) including critical peer-review, peer feedback and whole group discussions. The researchers took time and learning effect between the practices into consideration while collecting the data, which also helped the participants build confidence and rapport with each other. It took four months (from October to February) to collect the data. The detailed data collection procedure is given in .

Table 1. Data collection procedures

Grounded on the concept of experiential learning (Dewey, Citation1938; Kolb, Citation1984) which considers professional development as a spiral in which learning from one cycle triggers the other one (Dewey, Citation1986), the model in the study included three repetitive cycles; teaching practice (video recording, observation, RRR and CPR), focus group discussion (peer feedback, mentor feedback and whole group discussion) and coding. Following the completion of all three cycles, the T/R applied a post open-ended questionnaire (written interview) and supervised an overall discussion. The suggested model can be seen in .

Moreover, Video Stimulated Recall (VSR) was used to connect actual behaviour with the way of thinking. VSR is a critical method to investigate what happened in the classroom and why it happened. The participants had a chance to watch their performance as many times as they wanted. Furthermore, analysing their videos fostered their ability to identify areas for improvement, to reflexively interpret their classroom practices and to construct their future actions.

Data analysis

As this data-driven study entailed, inductive content analysis was predominantly used to figure out meanings and relationships of words and themes. The research was participant-oriented, in which the participant teachers’ needs in teaching were investigated through pre-interviews before the implication of reflexive cycles. The interviews were recorded, transcribed and analysed using inductive analysis. The participants answered three questions mainly focusing on:

- how they define themselves in managing their classrooms and motivating students.

- whether they exchange ideas with colleagues and if so, to what extent

- what they would like to change or improve in their teaching

After inserting the data gathered through the interviews, reflective and reflexive reports and peer-reviews into NVivo 12, coding process started regarding the research questions. Then, the codes were examined thoroughly to seek if it was necessary to merge some of them or create sub-codes. Finally, following the confirmation of the codes and themes by an outsider researcher, five sub-themes were created and made meaningful for the reader (Appendix 1).

In addition, CPR checklist and the T/R’s observation checklist were analysed with some non-parametric tests. Assumptions of the parametric tests include normal distribution; yet the size of the sample is of high significance (Pallant, Citation2010). According to Büyüköztürk (Citation2011), the number of participants should be over 30 to certify normal distribution. Therefore, Friedman Test, Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test and Spearman Correlations were applied due to the small size of participants (n < 30, n = 8), as non-parametric tests are ‘useful when you have very small samples’ (Pallant, Citation2010, p. 213). First, the points given by both peers and the mentor during the teaching practices were compared using the Friedman Test. Then, the Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test was applied to highlight whether the difference between paired samples was significant (Büyüköztürk, Citation2011).

Findings

Reflexive practice for professional development

In what ways these reflexive cycles have influenced teachers’ professional development was aimed to find out. Regarding the information gathered through the extracts from the written interview and overall discussions, the researchers constructed some nodes which are shown in .

Table 2. Nodes compared by number of items coded

Beliefs on reflexivity

Since the participants were eager to participate in this exploratory practice, they were believed to have positive attitudes towards reflecting repetitively on their teaching. Except one of the participants, they were all encouraged to be recorded and observed. For instance, P2 stated, ‘I was nervous at first. Then, it was nice to realize my strengths’. Similarly, P5 specified, ‘These cycles have contributed to me a lot. I think it is an effective method for a teacher to monitor his stance, tone of voice and gestures’. Also, P7 wrote, ‘I was really eager to participate in this study. It was a great opportunity and I feel one step ahead’. They also emphasized that reflecting on their teaching had a constructive effect on their future lessons.

Attitudes towards collaboration

Need for collaboration was one of the self-identified needs detected in pre-interview. P1 claimed, ‘Our exchange of ideas was very informative’. and likewise, P5 stated, ‘Both my self-criticism and my friend’s feedback made me more comfortable and confident in my third practice. This mutual observation and criticism improved me’. P8, also, highlighted, ‘It was nice to share ideas and exchange feedback with my colleagues. We learned a lot from each other’.

21st century teachers are supposed to be willing to learn from colleagues and gain new insights. In this research, via FGD, they gave constructive feedback to one another and learn from each other’s experiences. P2 emphasized the merits of the positive language used in feedback. Correspondingly, P3, stated ‘Our feedback sessions were highly valuable. It was exactly how it should be. My partner made some negative comments on my performance in such a nice way that I even liked them’. P7, similarly, indicated they gave feedback to each other respectfully. Ultimately, they highlighted the value of collaboration for their upcoming practices.

Contextual and pedagogical knowledge

The study aimed to contribute to the teachers’ professional development and improve their way of thinking from different perspectives. P1 claimed he learned a lot from his colleague indicating, ‘Seeing a different teaching style made me look at myself from a different perspective. I learned how to keep motivation high and what to pay attention to for effective classroom management’. P3 also stated, ‘I am glad that I invested in myself. I believe I will review and improve my teaching method thanks to these reports’. In parallel with these, P5 stated this process has contributed a lot to him thanks to observing another teacher’s techniques and strategies, and added, ‘I learned what to do differently and how to change the atmosphere in the classroom as well as how to strengthen my emotional bond with children’. Besides, P8 indicated, ‘Participating in such a study encouraged me to pursue my professional development and prompted me to explore ways to teach children better’. Consequently, increasing contextual and pedagogical knowledge within the concept of reflexivity enabled teachers to gain new insights and become reflexive practitioners.

Evaluation of engagement and individual improvement

To engage the participants in reflexive practice, the researchers synthesized the 21st century skills of an EFL teacher with mediational tools and implications in the study. While observing both themselves via VSR and their peers, the participants thought critically and interpreted on both their colleagues’ and own practices. Reflecting on classroom management, instructional strategies, guiding and motivation; they focused on problem solving skills. Rather than solely gaining problem solving skills, each participant found an opportunity to understand the meaning of their experiences in terms of the self (Nguyen et al., Citation2014; Palacios et al., Citation2021). Further, video enhanced observation aided them to analyse why they behaved in that way. They also used self-regulation skills by writing RRR and regulating their upcoming practices, which require openness and willingness (Marshall, Citation2019; Marshall et al., Citation2021; Nguyen et al., Citation2014). In addition, through CPR and FGD, they evaluated and gave constructive feedback to their peers, and shared ideas about their own experiences, which was a great example of collaboration. Lastly, they showed their creativity and openness to innovation during the reflexive cycles. After each cycle, they tried new strategies, either created by themselves or learnt from their colleagues.

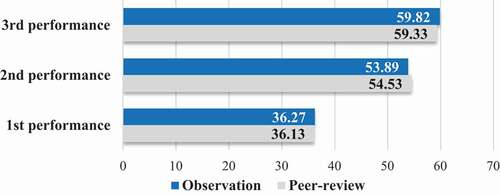

An analysis of peer review and the T/R’s observation checklist scores (converted into T-score) revealed a noteworthy increase in their performances. Interestingly, the improvement between the first two teaching practices was higher than the one between the second and the third practices as shown in .

According to the Friedman test, three teaching practices were significantly different from each other both in CPR χ2 (2, n = 8) = 11.400, p < .005 and observation scores χ2 (2, n = 8 = 11.120, p < .005). In addition, Wilcoxon Signed Rank tests (adjusted for Bonferroni correction, setting significance level at p < .016) were applied to see the differences thoroughly. After Bonferroni correction, the difference between the 1st and the 2nd CPR was significant (z = −2.414; p = .016), with a large effect size (r = .16). Similarly, the difference between the 1st and the 3rd CPR was significant (z = −2.536; p = .011), with a large effect size (r = .21). In contrast, there was not a significant difference between the 2nd and the 3rd CPR scores (z = −879; p = .380). On the other hand, the researchers found out that the significance in difference between peer and observer scores were not similar. After Bonferroni correction, none of the teaching practices were significantly different from each other regarding the observation scores.

To figure out why peer review scores and observation scores differed, the researchers investigated correlations between them. They positively correlated in the 1st (rho = .73, n = 8, p < .05) and the 3rd (rho = .85, n = 8, p < .01) reflexive cycles. However, there was no correlation between the peer scores and the observation scores in the 2nd reflexive cycle (rho = .15, n = 8, p > .05). Therefore, the topics were separately examined to understand the reason. Both the scores on classroom management (rho = .22, n = 8, p > .05) and guiding and motivation (rho = .17, n = 8, p > .05) did not correlate with each other, which means the 2nd teaching performance was evaluated diversely by the peers and the observer.

As for individual improvement, the participant teachers’ performances were examined and shown in . The scores were calculated out of 18 points for each teaching practice.

Table 3. The points collected during practices

According to the scores, it can be concluded that P4, with more than 10 years of experience and a PhD, did not show much improvement. Likewise, findings show that P3 (experienced more than 10 years) showed the least improvement. On the other hand, as an inexperienced teacher, P5 showed a great improvement.

Discussion

The findings verified the Reflexive Practice Triplication Model was resourceful. The effectiveness of the reflexive cycles was investigated within three aspects: self-efficacy, collaboration skills and teacher autonomy. In this section, the interactive relationship of these with reflexive practice will be discussed.

As understood from the scores in , the participants may have believed they learnt how to perform better in the 2nd practice and did not put any effort in the 3rd practice. In that regard, reflexive cycles may not contribute much in the long term. P2, P3 and P4 showed less effort and improvement in the 3rd practice. This could be because of having high self-efficacy – P3 and P4 were determined to have a high self-efficacy considering their experience, their elucidations in reports and pre-interview – or attributing poor performance to their mood (P2). Therefore, it is indisputable that high self-efficacy perceptions (Wheatley, Citation2002; Wyatt, Citation2013, Citation2015) and attributions Erten (Citation2015) had a negative impact on teaching practice, even could have been ‘challenging’ (Wyatt, Citation2015) in contrast to many studies in the field.

On the other hand, self-efficacy perceptions may cause teachers to feel stressed towards new challenges (Wyatt, Citation2013). It was not easy for less experienced teachers with low self-efficacy to make reflexive interpretations on their teaching. In TALIS 2018, teachers’ self-efficacy perceptions concerning the quality of their teaching were examined and it is found that teachers with 5 years or less experience have lower efficacy about teaching skills and managing classroom than senior teachers. The participants with low self-efficacy (Wheatley, Citation2002) and who may need support (Wyatt, Citation2015) were more willing to share what they need in teaching. Jerald (Citation2007) highlighted teachers with higher self-efficacy were more open to experimentation (Chesnut & Burley, Citation2015); however, in this study, P5 with lower self-efficacy was more open to gain new insights and improve professionally.

Further, peer observation is known to support collaborative skills and contribute to professional development (Bozak, Citation2018; Kapçık, Citation2018; Kasapoğlu, Citation2002). Wyatt and Dikilitaş (Citation2017) also highlights group discussions enhance self-efficacy beliefs due to ‘the collaborative nature of the process’ (p. 561). In the study, collaborative engagement (observing others, peer-review, focus group discussions) appeared to enhance the participants’ self-efficacy. Ciampa and Gallagher (Citation2016) also claimed social interactions such as observing each other and receiving feedback play a great role to improve teachers’ self-efficacy. Kapçık (Citation2018), conducted a study on teachers’ attitudes towards observation and concluded that they ‘gained new insights into their teaching’ (Barkhuizen, Burns, Dikilitaş, and Wyatt, Citation2018, p. 56) The findings showed that collaboration throughout the study was enlightening and helped the teachers become reflexive practitioners. P1, P5, P7 and P8 underlined how collaboration was useful and how it affected their feelings and future actions. Akin to Dikilitaş and Mumford (Citation2019), the participants learnt to reflect both on their teaching and on their peers’ practices, thus contributed to the study individually and collaboratively.

As another aspect, teacher autonomy is tied up with critical reflection Dikilitaş and Mumford (Citation2019) (Ramos, Citation2006; Smith, Citation2001). Ramos (Citation2006) claims, ‘Autonomy is developed through observation, reflection, thoughtful consideration, understanding, experience, evaluation of alternative’ (p. 190). Still, many teachers do not know ‘how to analyse their weaknesses and take actions to improve them’ (Buğra, Citation2018, p. 79). This could be due to lack of strategies or scarcity of reflexive thinking skills. Thus, engaging in professional development activities brings along autonomy (Dikilitaş and Griffiths, Citation2017). In the current study, the positive impact of engagement in reflexive practice on teacher autonomy ([Dikilitaş & Comoglu, Citation2020; Leat et al., Citation2015) and interaction between autonomy and motivation (Dikilitaş & Mumford, Citation2019; Ushioda, Citation2011) were clearly seen. Like in Erten (Citation2015)’s study showing that having control over their learning might develop students’ autonomy, teacher autonomy can also be enhanced via engagement in reflexivity in which teachers have control over their teaching by ‘dealing with problems’ (Dikilitaş & Griffiths, Citation2017, p. 2) and overcoming the challenges in classrooms. This also helps teachers understand their potential as ‘controllers of their own development’ (Dikilitaş & Mumford,Citation2019, p. 254). In the same vein, P3 confirmed the RRR enabled her to concentrate more on how to guide students, which provided her with having ‘control over her professional development and practice’ (Dikilitaş & Griffiths, Citation2017, p. 35).

Conclusion and suggestions

In light of the findings, it can be finalized that the teachers who monitor and reflect on their teaching regularly and iteratively can address their needs and enhance their understanding of teaching. Nevertheless, since ‘knowing what to reflect upon out of the whole of one’s professional experience is not a clear process’ (Bolton, Citation2010, p. 8), teachers might need to be mentored as to what to reflect and how to benefit from this reflexive process.

A methodological limitation that needs to be acknowledged might lie with the inherent potential for bias concerning subjectivity in data analysis due to the inclusion of open-ended responses (Collet-Klingenberg & Kolb, Citation2011). Being an insider T/R might also have influenced the power relationship and bias, but the authors minimized these by (re)negotiating emerging themes. We are well aware of these limitations, and we, therefore, provided transparent thick descriptions of all the relevant information for the reader to assess the potential interposing bias within the study.

We suggest that the model be applied in various contexts to different groups of teachers. The effects of reflexive cycles on students’ learning outcomes might be investigated, which we did not address in this study. Besides, some certain trainings related to teachers’ needs may take place between the cycles to see if they influence teachers’ future practices. In addition, teachers might keep journals following each practice to figure out if they change their perceptions or improve them professionally. Lastly, long-term effects of such a reflexive cycle may be investigated.

Appendix.docx

Download MS Word (14.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ayça Aslan

Ayca Aslan is a highly focused, motivated and passionate EFL Teacher with more than a decade of successful experience in a private K12 institution in Ankara, Turkey, where she has been the head of English Department for secondary school. Ayça regularly assists teachers with effective teaching strategies and continuing professional development. She also holds a PhD degree in Foreign Languages Education from Hacettepe University, Turkey. She has dedicated her time and self both personally and professionally into gaining new insights and global perspectives in education and expanding her knowledge in order to bring innovations into the field through research. Her research interests comprise educational pedagogy and teacher education.

İsmail Hakkı Erten

İsmail Hakki Erten was a professor of applied linguistics and English language teaching at Hacettepe University, Turkey. His research focused on reading processes and vocabulary acquisition, affective aspects of learning English as an additional language, and teacher education. His recent research focused on academic self-concept and achievement attributions in language learning, and teacher motivation. His work appeared in scholarly journals such as System, European Journal of Teacher Education, Hacettepe University Journal of Education, and Reading in a Foreign Language. He served as the editor-in-chief of Eurasian Journal of Applied Linguistics (www.ejal.eu).

Kenan Dikilitaş

Kenan Dikilitas is a Professor of University Pedagogy at the University of Stavanger in Norway, where he is supporting professional development of academics as well as teaching 'Qualitative Research in Higher Education' as a graduate course. Kenan's research interests include teacher education, mentoring and investigating action research, as well as bilingual education focusing on in-service teachers' development in pre-school context. He has co-authored two monographs on 'Developing Language Teacher Autonomy through Action Research' (2017) and 'Inquiry and Research Skills for Language Teachers' (2019) published by Palgrave and published research articles in international journals.

References

- Adams, P. (2009). The role of scholarship of teaching in faculty development: Exploring an inquiry-based model. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 3(1), n1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2009.030106

- Altalhab, S., Alsuhaibani, Y., & Gillies, D. (2021). The reflective diary experiences of EFL pre-service teachers. Reflective Practice, 22(2), 173–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2020.1865903

- Antonacopoulou, E. P. (2004). The dynamics of reflexive practice: The relationship between learning and changing. Organizing Reflection, 47–64.

- [author(3)]

- Avalos, B. (2011). Teacher professional development in Teaching and Teacher Education over ten years. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(1), 10–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007

- Birt, L., Scott, S., Cavers, D., Campbell, C., & Walter, F. (2016). Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1802–1811. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316654870

- Bolton, G. (2010). Reflection and reflexivity: What and why. Reflective Practice: Writing and Professional Development, 3–24.

- Boud, D., Keogh, R., & Walker, D. (1985). Promoting reflection in learning: A model. In D. Boud, R. Keogh, & D. Walker (Eds.), Reflection: Turning experience into learning (pp. 18–40). Nichols.

- Bozak, A. (2018). The points of school directors on peer observation as a new professional development and supervision model for teachers in Turkey. World Journal of Education, 8(5), 75–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v8n5p75

- Buğra, C. (2018). A Journey into the exploration of the self through developing self-reflective skills in an EFL context. In G. Barkhuizen, A. Burns, K. Dikilitaş, & M. Wyatt (Eds.), Empowering teachers, empowering learners (pp. 79–88). Kent: UATEFL.

- Burhan-Horasanlı, E., & Ortaçtepe, D. (2016). Reflective practice-oriented online discussions: A study on EFL teachers’ reflection-on, in and for-action. Teaching and Teacher Education, 59, 372–382. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.07.002

- Butler, D. L., & Schnellert, L. (2012). Collaborative inquiry in teacher professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(8), 1206–1220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.07.009

- Büyüköztürk, Ş. (2011). Sosyal Bilimler için Veri Analizi El Kitabı. (1. bs.). Pegem Akademi.

- Carlson, J. A. (2010). Avoiding traps in member checking. The Qualitative Report, 15(5), 1102–1113.

- Chesnut, S. R., & Burley, H. (2015). Self-efficacy as a predictor of commitment to the teaching profession: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 15, 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.02.001

- Cholifah, A. N., Asib, A., & Suparno, S. (2020). In-service EFL teachers’ engagement in reflective practice: What tools do in-service teachers utilize to reflect their teaching? Pedagogy: Journal of English Language Teaching, 8(1), 24–33. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.32332/pedagogy.v8i1.1960

- Ciampa, K., & Gallagher, T. L. (2016). Teacher collaborative inquiry in the context of literacy education: Examining the effects on teacher self-efficacy, instructional and assessment practices. Teachers and Teaching, 22(7), 858–878. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2016.1185821

- Cirocki, A., & Widodo, H. P. (2019). Reflective practice in English language teaching in Indonesia: Shared practices from two teacher educators. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research, 7(3), 15–35. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.30466/IJLTR.2019.120734

- Collet-Klingenberg, L. L., & Kolb, S. M. (2011). Secondary and transition programming for 18-21 year old students in rural Wisconsin. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 30(2), 19–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/875687051103000204

- Collins, C. H. (2004). Collins Cobuild Advanced Learner’s English Dictionary.

- Connelly, L. M. (2016). Trustworthiness in qualitative research. Medsurg Nursing: Official Journal of the Academy of Medical-Surgical Nurses, 25(6), 435–437.

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage publications.

- Cruickshank, D. R. (1987). Reflective teaching: The preparation of students of teaching. Reston, Association of Teacher Educators.

- Cunliffe, A. L. (2009). Reflexivity, learning and reflexive practice. The SAGE Handbook of Management Learning, Education and Development, 405–418. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507608099315

- Cunliffe, A. L., & Easterby-Smith, M. (2004). From reflection to practical reflexivity: Experiential learning as lived experience. Organizing Reflection, 30–46.

- Dewey, J. (1933). How We Think. Heath & Co.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. MacMillan.

- Dewey, J. (1986). Experience and education. The Educational Forum, 50(3), 241–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00131728609335764

- Dikilitaş, K., & Comoglu, I. (2020). Pre-service English teachers’ reflective engagement with stories of exploratory action research. European Journal of Teacher Education, 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1795123

- Dikilitaş, K., & Griffiths, C. (2017). Developing Language Teacher Autonomy Through Action Research. Cham: Springer.

- Dikilitaş, K., & Mumford, S. E. (2019). Teacher autonomy development through reading teacher research: agency, motivation and identity. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 13(3), 253–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2018.1442471

- Erten, H. (2015). Attribution retraining in L2 classes: prospects for exploratory classroom practice. Teacher-Researchers in Action, 357–367.

- Fairley, M. J. (2020). Conceptualizing language teacher education centered on language teacher identity development: A competencies-based approach and practical applications. TESOL Quarterly, 54(4), 1037–1064. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.568

- Ferraro, J. M. (2000). Reflective practice and professional development. ERIC Digest.

- Fines, B. G. (2014). The power of a destination: How assessment of clear and measurable learning outcomes drives student learning. Browser Download This Paper. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2529086

- Freyn, S. L., Sedaghatjou, M., & Rodney, S. (2021). Collaborative engagement experience-based learning: A teaching framework for business education. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 11(5), 1252–1266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-08-2020-0182

- Godínez Martínez, J. (2022). Action research and collaborative reflective practice in English language teaching. Reflective Practice, 23(1), 88–102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2021.1982688

- Hung, D. M., & Thuy, P. T. (2021). Reflective teaching perceived and practiced by EFL teachers-A case in the south of Vietnam. International Journal of Instruction, 14(2), 323–344. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2021.14219a

- Jantori, P. (2020). Examining digital practices of Thai pre-service EFL teachers through reflective journals. Human Behavior, Development and Society, 21(4), 47–56.

- Järvelä, S., Järvenoja, H., Malmberg, J., Isohätälä, J., & Sobocinski, M. (2016). How do types of interaction and phases of self-regulated learning set a stage for collaborative engagement? Learning and Instruction, 43, 39–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.005

- Jerald, C. D. (2007). Believing and achieving. In The center for comprehensive school reform and improvement.

- Kapçık, A. C. (2018). Examining the effect of structured peer observation on EFL teachers’ perceptions, attitudes and feelings. In G. Barkhuizen, A. Burns, K. Dikilitas, & M. Wyatt (Eds.), Empowering teachers, empowering learners.

- Karakaş, A., & Yükselir, C. (2020). Engaging pre-service EFL teachers in reflection through video-mediated team micro-teaching and guided discussions. Reflective Practice, 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2020.1860927

- Kasapoğlu, A. E. (2002). A suggested peer observation model as a means of professional development [Doctoral Dissertation]. Bilkent University.

- Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs.

- Korucu-Kış, S., & Kartal, G. (2019). No pain no gain: Reflections on the promises and challenges of embedding reflective practices in large classes. Reflective Practice, 20(5), 637–653. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2019.1651715

- Leat, D., Reid, A., & Lofthouse, R. (2015). Teachers’ experiences of engagement with and in educational research: What can be learned from teachers’ views? Oxford Review of Education, 41(2), 270–286. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2015.1021193

- Lietz, C. A., Langer, C. L., & Furman, R. (2006). Establishing trustworthiness in qualitative research in social work: Implications from a study regarding spirituality. Qualitative Social Work, 5(4), 441–458. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325006070288

- Lisle, A. M. (2010). Reflexive practice: Dialectic encounter in psychology & education. Xlibris Corporation.

- Loh, J. (2013). Inquiry into issues of trustworthiness and quality in narrative studies: A perspective. The Qualitative Report, 18(33), 1–15. http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR18/loh65.pdf

- MacDonald, K. (2011). A reflection on the introduction of a peer and self assessment initiative. Practice and Evidence of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 6(1), 27–42.

- Marshall, T. (2019). The concept of reflection: A systematic review and thematic synthesis across professional contexts. Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 20(3), 396–415. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2019.1622520

- Marshall, T., Keville, S., Cain, A., & Adler, J. R. (2021). On being open-minded, wholehearted, and responsible: A review and synthesis exploring factors enabling practitioner development in reflective practice. Reflective Practice, 22(6), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2021.1976131

- Matthews, B., & Jessel, J. (1998). Reflective and reflexive practice in initial teacher education: A critical case study. Teaching in Higher Education, 3(2), 231–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1356215980030208

- McArdle, K., & Coutts, N. (2010). Taking teachers’ continuous professional development (CPD) beyond reflection: Adding shared sense-making and collaborative engagement for professional renewal. Studies in Continuing Education, 32(3), 201–215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2010.517994

- Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Moradkhani, S., Raygan, A., & Moein, M. S. (2017). Iranian EFL teachers’ reflective practices and self-efficacy: Exploring possible relationships. System, 65, 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.12.011

- Nadin, S., & Cassell, C. (2006). The use of a research diary as a tool for reflexive practice. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 3(3), 208–217. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/11766090610705407

- Nguyen, Q. D., Fernandez, N., Karsenti, T., & Charlin, B. (2014). What is reflection? A conceptual analysis of major definitions and a proposal of a five-component model. Medical Education, 48(12), 1176–1189. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12583

- Palacios, N., Onat-Stelma, Z., & Fay, R. (2021). Extending the conceptualisation of reflection: Making meaning from experience over time. Reflective Practice, 22(5), 600–613. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2021.1938995

- Pallant, J. (2010). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using SPSS. Open University Press.

- Ramos, R. C. (2006). Considerations on the role of teacher autonomy. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, (8), 183–202. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.10510

- Reich, Y. (2017). The principle of reflexive practice. Design Science, 3, 1–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/dsj.2017.3

- Ripamonti, S., Galuppo, L., Gorli, M., Scaratti, G., & Cunliffe, A. L. (2016). Pushing action research toward reflexive practice. Journal of Management Inquiry, 25(1), 55–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492615584972

- Rogers, R. R. (2001). Reflection in higher education: A concept analysis. Innovative Higher Education, 26(1), 37–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010986404527

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner. Temple Smith.

- Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. Jossey-Bass.

- Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-2004-22201

- Smith, R. C. (2001). Teacher education for teacher-learner autonomy. Language in Language Teacher Education. http://homepages.warwick.ac.uk/~elsdr/Teacher_autonomy.pdf

- Ushioda, E. (2011). Why autonomy? Insights from motivation theory and research. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 5(2), 221–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2011.577536

- Wheatley, K. F. (2002). The potential benefits of teacher efficacy doubts for educational reform. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00047-6

- Wright, C. A., & Diener, M. L. (2020). Advancing participant-oriented research models in research intensive universities: A case study of community collaboration for students with autism. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 24(1), 143–152.

- Wyatt, M. (2013). Overcoming low self-efficacy beliefs in teaching English to young learners. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(2), 238–255. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2011.605082

- Wyatt, M. (2015). Using qualitative research methods to assess the degree of fit between teachers’ reported self-efficacy beliefs and their practical knowledge during teacher education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(1), 7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2015v40n1.7

- Yong-jik, L., & Davis, R. (2017). Literature review of microteaching activity in teacher education programs: Focusing on pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs. Culture and Convergence, 34(7), 203–222.