ABSTRACT

Student populations have become increasingly diverse in the past decades, but Higher Education Institutions have not been evolving their assessment practices at the same rate. This study used a survey to investigate the barriers and enablers to diversifying assessment including using student choice of assessment. In examples where educators had diversified students’ assessment tasks, it also explored its benefits, outcomes and the association between familiarity, resources and success of the assessment implementation. The findings identified that student engagement and empowerment were key benefits to diversification. There was an overall perception that time and resources were the greatest barriers but this was not supported in the examples provided. The fear of grade inflation, when diversifying, appears to run counter intuitive to supporting student success in assessment. Further work needs to be done to interrogate what is meant by the concept of ‘diverse assessment’ and to support educators in its implementation.

Introduction

Context

The emerging national and international concept of student success (European University Association [EUA], Citation2020; Murray et al., Citation2019; Advance HE, Citation2019) relies on a higher education culture which ‘optimises the learning and development opportunities for each student’ (National Forum, Citation2019, p. 28). However, this can be a challenge given that higher education has never seen such diverse student cohorts. There are increasing numbers of international students, mature students, students with disabilities, in addition, there are many students with hidden diversities, for example, students travelling distances and students with different learning experiences. Higher education ‘however, is evolving at a slower rate than student cohorts are diversifying and barriers faced by students are inequitable’ (Mercer-Mapstone & Bovill, Citation2019, p. 1).

The first point of potential inequity is access to higher education. Irish policies are trying to address this inequity. Over the last twenty years there have been many initiatives focused on widening participation and access for students from under-represented groups. The National Access Policy sets targets to increase the participation of students with disabilities, mature students, part-time students, students from designated socio-economic groups and Irish Travellers (Higher Education Authority [HEA], Citation2015).

Access into a higher education institution is only part of the story of possible inequity, students also need equitable opportunities to succeed (National Forum, Citation2019). The authors’ institution, University College Dublin (UCD), has adopted a whole-institution approach to student inclusion which focuses on equitable access, progression and successful completion for all students. Although staff (from this point on known as ‘educators’) are becoming increasingly aware that they need to support both known and unknown diverse cohorts, this awareness has not been matched by an evolution of equitable assessment practices within higher education. For example, an Irish nationwide study showed that examinations remain the most common form of assessment (National Forum, Citation2016). Inclusive assessment frameworks, such as Universal Design for Learning (CAST, Citation2018), have been in place for some time but we have yet to see a related widespread shift in institutional assessment practices. In Ireland, there has been an increase of 220% in the number of students with disabilities registering for assessment accommodations in higher education in the last 10 years (AHEAD, Citation2020). In UCD in 2018–19, 32% of undergraduate students were part of the national access target groups for widening participation, in addition 29% of the full population were international students. It is clear that UCD, like most others, is now very diverse and the rate of those seeking accommodations based on a disability (the only proportion of this diverse cohort who can formally do so) is increasing annually. The increasing number of student cohorts seeking special accommodations for many of the so-called traditional assessments demonstrates that current assessment practices are not accommodating the needs of diverse students – flexibility and diversity is therefore required.

Diversity and choice of assessment

At one level diverse assessment is a contested concept, as what is diverse for one student, or educator, is not for another; an essay may be familiar to arts and humanities students but not to science students. There are, however, ‘traditional’ assessments that have been used frequently in many areas, such as the written exam, and specific ‘familiar’ assessment in some contexts, such as laboratory reports in Science (National Forum, Citation2016). Diversifying assessment with some significant level of change has been described as ‘innovative assessment’. Hounsell et al. (Citation2007, p. 60) defined innovation as that which is ‘novel in the eyes of the begetters and beholders and entails more than aminor or trivial adjustment or modification’. Diversifying assessment usually involves educators changing a more familiar assessment to a different approach. However, an extension of diversification is where educators may give students a choice between two or more assessments in the same module (Garside et al., Citation2009; Mogey et al., Citation2019; O’Neill, Citation2011, Citation2017). This has the additional advantages of allowing students to choose what suits them best, often, but not always, allowing the retention of the original traditional approach.

Diversifying assessment is not without its problems: students and educators may be resistant to change; they are unfamiliar with the approach; it can cause stress; and students can perform poorly as a result (Armstrong, Citation2014; Bevitt, Citation2015; Kirkland & Sutch, Citation2009; Medland, Citation2016). In addition, for international students in particular, ‘coping with novel assessment represents just one part of a much larger and slower process of adaptation’ (Bevitt, Citation2015, p. 116). Kirkland and Sutch (Citation2009) broadly categorises the barriers to diversification around: a) The Innovation: factors associated with the innovation; b) Micro-level influences: factors related to the educator themselves, such as their capacity, competence, confidence; c) Meso-level influences: local factors, such as the school culture, school management wider community; d) Macro-level influences: these factors relate to national policy, professional bodies. Zhao et al. (Citation2002) explore in their model the impact of the success of an innovation in relation to both the ‘distance’, akin to the idea of familiarity, and ‘dependence’, which relates to the level of resources required. They suggest that the closer the change is to the original assessment the more chance that it will be successful. However, Gibbs and Dunbar-Goddet (Citation2009) warn that students often don’t have the opportunity to become familiar with these changes.

In this study, therefore we wanted to explore:

What are the overall barriers and enablers to diversifying assessment?

In addition, where educators had diversified (an example of an implementation)

What are the benefits to diversifying assessment?

Was it successful?

What is the association between its familiarity, required resources (time, funding, etc.) and success?

It should be noted that this study was planned before the Covid-19 context, which resulted in many educators changing their assessment strategies due to the inability to hold traditional timed exams. Therefore, many of these changes were also captured in this study.

Methodology

Following ethical approval, this study was carried out in UCD which has circa 30,000 students across a wide range of disciplines. The authors decided to use an electronic survey methodology with both quantitative and qualitative questions. For this study, the authors developed a working definition of diversity and choice of assessment, piloting these definitions and the survey questions, with a small number (n = 5) of colleagues making changes based on their feedback. The definitions were as follows:

‘Diverse assessment method is where an assessment method is introduced that is less familiar (to you and/or the students) and increases the range of assessments in your discipline. For example, replacing an “end-of-semester exam” with a less familiar method such as an “essay” or an “online or take-home exam”’.

‘Choice of assessment is where each student in the module has a choice between two or more different assessment methods, for example, a poster or a presentation, and they choose one of these assessment methods’.

An invitation to participate in the survey was sent by email to all UCD module coordinators (educators) (n = 1,344). The survey was available from 6 May to 24 June 2020 (a copy of the survey is available at www.tinyurl.com/ONeillPadden2020). The educators’ participation was voluntary and they were informed of their rights to withdraw. Two months prior to the survey’s circulation educators had to suddenly move their teaching online, due to COVID 19. Therefore, the data includes assessments that were also diversified due to this context. The timing of the survey allowed for educators to have completed the grading process so they could determine relative success of these changes.

The initial quantitative question in the survey, with 16 statements, encouraged the educators to think about general barriers to diversification and choice of assessment methods, across the programme they teach on the most. These statements were created by the authors, a limitation of the study, but were based on the work of Kirkland and Sutch (Citation2009). They broadly focused on categories around: The innovation: micro-level influences; meso-level influences and macro-level influences. One open-ended question then explored the educators enablers to implementation.

Following this, where relevant, they were asked to describe in more detail an example of an implementation where they had diversified their assessment, giving priority to the choice of assessment if they had used it. These questions explored, for example, the implementation’s perceived benefits, external examiner feedback, the methods used and a qualitative question to elaborate on why it was, or was not, successful. A thematic analysis of responses (Flick, Citation2014) to this qualitative question was conducted manually by the authors using excel, to identify common or repeated patterns within the responses.

Finally, three quantitative questions (rated 1–100), building on Zhao et al.’s (Citation2002) Distance and Dependence model, explored perspectives of the educator on: 1) the extent to which they believed that their implementation example was a success; 2) how familiar it was to the students (distance); and 3) how resource intensive it was for them and their School (dependent on resources).

Findings and discussion

Demographics

One hundred and sixty module co-ordinators fully completed the survey, a response rate of 12% of the full sample UCD module coordinators. These educators were a relatively experienced group, with 81 (51%) with more than 15 years, and 55 (34%) with 6–15 years, assessment experience in higher education. This is quite reflective of educators in a module co-ordinator role in the institution. Only 19% had ever introduced a choice of assessment (n = 31). There was a wide cross-section of disciplines in the study, representing all 10 disciplines highlighted in the International Field of Study (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, Citation2014).

What are the overall barriers and enablers to diversifying?

The barriers

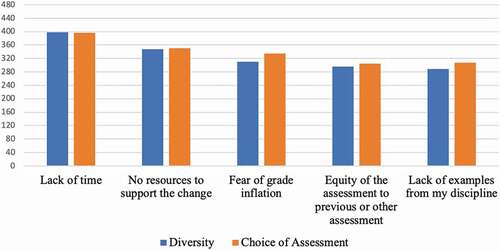

The educators were asked 16 statements on the general meso, macro and micro-level barriers to both a diverse assessment and choice of assessment where they were ‘not a barrier’, ‘a slight barrier’ or a ‘significant barrier’ (weighted score: level (3) x number of educators (n = 160) = Maximum of 480). There was a very similar pattern in the top five barriers in both of these approaches (See ).

Curiously, one of the lowest scored barriers in both approaches, particularly in choice of assessment, was ‘fear of students failing’. In comparing the barriers to the findings of Kirkland and Sutch’s (Citation2009) levels of influences, ‘time’ and ‘resources’ were also by far the greatest barriers in their study. Kirkland and Sutch (Citation2009, p. 24) also emphasise that ‘effective resourcing plays an important part in overcoming barriers to innovation’. This is supported by Jones (Citation2004) who highlights, in particular with technological innovation, that time, training equipment and technical support are vital. In a recent study in South Africa, Jakovljevic (Citation2019, p. 63) developed a set of 13 criteria for supporting innovation in higher education, one in particular highlighted that ‘teaching load, administrative support and incentives’ should be addressed to support innovation. In essence, the educators in this study were in line with other studies that diversification and innovation require time and other relevant resources.

Surprisingly, the educators were more concerned about the students’ grade inflation than they were about students failing. However, if diversifying allows more student cohorts to do well, this may well validly lead to grade inflation. One might query why educators would have concerns about students doing very well. This may be due to higher education’s inherent leaning towards norm-referenced criteria (Lok et al., Citation2016; Popham, Citation2014). It is common practice for exam boards to look for a normal curve. When a cohort of students are seen to all do well, many exam boards question this. This is also alluded to by Lok et al. (Citation2016) who maintain that grade inflation can erode public trust in the grading system. The literature also suggested that educators do not want to seem to be marking easily. Many educators feel that grade inflation undermines academic standards, for example, Seldomridge and Walsh (Citation2018) use the language of ‘waging the war on clinical grade inflation’ in Nursing. Educators beliefs on this can relate to their capacity, competence and/or confidence. Tannock (Citation2017, p. 1350) warned that grading to a normal curve can increase ‘social division among students depending on where they stand in the grading hierarchy, and particularly destructive impacts on the learning, esteem and identity of students at the lower end of this hierarchy’. However, Lok et al. (Citation2016) explained that norm and criterion-referenced assessment can complement each other if careful consideration is given to their advantages and disadvantages in institutional policy.

The enablers

In addition to barriers, educators were asked to identify a key enabler to the overall implementation of diversity and/or choice of assessment in their practices. A thematic analysis of these open-ended responses showed that resources (time, staffing and funding) and examples (discipline-specific and with clear evidence of success/impact) were identified as the key enablers for implementation. Providing examples are at the level of the ‘Innovation’ in Kirkland and Sutch’s model (Citation2009). This confirms that resources and examples are seen by educators as enablers to diversifying. These enablers, when not in place, are similar to what was described as barriers to diversification in this study.

Examples of implementation

The assessment methods

There were 124 examples described, 95 examples of diverse assessment and 29 examples of choice of assessment methods. Educators were asked to describe the methods of assessment they used in their example. A thematic analysis of the resulting data showed that the most commonly used diverse methods are not necessarily diverse to all educators as presentations, essays, reflective writing or journals came up most frequently. Other methods noted as diverse reflected the necessary pivot to online assessment due to Covid-19; most notably a shift from an in-person timed exam to one which was online, open book or take home. In relation to diverse assessment methods, of the 95 educators who provided such examples, 55 changed their continuous assessment, 21 changed end of semester examination method and 19 changed both. Also of note is that 14.7% of educators (n = 14) noted that their diverse assessment method was group-based. Where educators used choice of assessment the most frequent method was a choice between an essay or a presentation. Forty-two (44%) of those who gave examples of diversification, and 6 (20%) of those who gave choice of assessment examples, introduced them due to COVID 19. These educators would have had more limited time to reflect on the student feedback from these recent changes.

The benefits and successes in diversifying

Using a predefined list, the top three rated benefits for diversification perceived by the educators were ‘student engagement’, ‘student empowered’ and ‘accommodated the learning of diverse students in my module’. Choice of assessment was particularly strong on ‘empowering students’ and ‘accommodated the learning of diverse students’.

Educators were then asked to elaborate on why they thought this implementation was a success/not a success. The authors did not provide a definition of success, so the reasons provided were unprompted and could be validated through a further survey in the future. A thematic analysis of these open-ended responses revealed a variety of reasons for the implementation being deemed successful – from both the educators and student perspectives. Eighty-two educators elaborated on reasons for success of their implementation of diversity of assessment. These are broadly categorised as follows (where they were listed by more than four educators):

Improved student engagement (n = 22),

Improved learning experience (n = 18),

Positive student feedback (n = 16),

Good student performance (n = 14),

Assessed learning outcomes more accurately (n = 8).

Example 123 using online MCQs highlighted that it was successful because it had ‘100% engagement and improved student performance overall’, while Example 49 using a student journal and a student exhibition maintained it was successful as it was a ‘transformative experience for students’.

The pattern changes when looking at the implementation of choice of assessment. Of the 29 educators who provided such examples, 22 were deemed successful. The reasons choice of assessment was deemed successful were broadly categorised as follows (where they were listed by more than four or more educators):

Positive student feedback (n = 9),

Improved learning experience (n = 5),

Improved equity (n = 4).

Example 82 (a choice of assessment example) asked students to either a) create a personal brand website and a process report or b) write a project analysis consultancy report. They felt it was successful because ‘student commented favourably on the choice offered. Both options were taken up by different student’. Example 100 described their methods as ‘choice of either presenting a written essay or presenting a pre-narrated slide presentation’. When asked why they felt the intervention was a success, they noted: ‘It played to each student’s strengths …’

In 2019, the European Commission highlighted the ‘need to develop new forms of assessment through which learners have an active role, become aware of their learning processes and needs, and develop a sense of responsibility for their learning’ (Kapsalis et al., Citation2019, p. 11). Educators in this study did perceive that diversifying assessment seemed to support more active student engagement as did choice of assessment which also enhanced student empowerment. Student success according to a recent national report (National Forum, Citation2019) encompasses not just engagement but a range of different concepts to both students and educators. Student success in this study was also regularly described, by the educators, in relation to student performance, i.e. students getting good grades. High grades is one of the top measures of student rated success in the recent national report (National Forum, Citation2019). Other measures of success highlighted by educators in this study were related to transformative learning experiences; in particular, in the choice of assessment examples assessment was more equitable. Other studies have found that choice of assessment has great potential to support equity of assessment in diverse student cohorts (Garside et al., Citation2009; Mogey et al., Citation2019; O’Neill, Citation2017).

When analysing the qualitative responses where the implementation was not deemed clearly successful, concern for the integrity of the assessment method, student complaints and grade inflation where the responses which were listed most frequently.

Educators were asked if they received any feedback from the external examiner on their implementation (either for diversity or choice) and, if so, what was the nature of the feedback they received. Of the 95 educators who described implementing diversity of assessment, only 25 reported having received related comments and these were all reported as positive, e.g. ‘This assessment is an excellent example of a method that truly integrates theory and practice’. Of the 29 educators who described implementation of choice of assessment, eight reported positive comments from external examiners, two reported negative comments and 18 reported no comments. One of the negative comments was reported as ‘Some concern that grades were higher than in other modules’. This supports the trend in this study of a concern regarding grade inflation in diversifying and/or choice of assessment.

Success: Association with resources and familiarly

There was a high number of examples that could be considered successful according to the educators (above 50 out of 100). However, using a Pearson’s correlation (r), there was no statistically significant correlation found when exploring the rating (1–100) in the examples (n = 124):

Between their perceived ‘level of success’ and the ‘level of the resource intensiveness’ (r (122) = −.007, p > 0.05), or

Between perceived ‘level of success’ and ‘level of familiarity’ (r (122) = .104, p > 0.05).

Zhao et al. (Citation2002) maintained that there was an association between familiarity and success. The more familiar the more successful. In this study, there was no significant correlation between familiarity of the assessment to the students and perceived success by the educators. It is interesting to note, also, that a large number of examples scored high on success and scored low on familiarity. Familiarity can be a problematic term. For example, the study explored whether the educators thought the implementation was familiar to the students. However, educators may not be completely aware of the level of familiarity of assessment to students in a modularised curriculum. There were a variety of methods including online assessments, podcasts and presentations. It is unclear why this result is different to that expected by others such as Zhao et al. (Citation2002). For example, do students take more care with new, diverse assessments? Did they do better because there was move away from the examination in many examples? What do educators understand as unfamiliar, maybe it is unfamiliar to them and not to the students? This needs further investigation.

Conclusion and recommendations

Student engagement and empowerment was a key benefit of diversifying assessment in this study. In particular choice of assessment was strong on empowering students in their learning. Choice of assessment was not a common approach in this study, but it can have the advantage of using both familiar and less familiar approaches, giving these diverse cohorts of students the choice of either approach. Where possible, educators should consider choice of assessment as an approach to diversification.

Educators reported that many students succeeded with unfamiliar assessments. In the design of this research the authors spent some time grappling with the definition of diversity of assessment. What does diversity mean in this context? How unfamiliar does it have to be called diverse? While the definition of students choice of assessment is relatively clear, that of diversity of assessment may need further consideration. The authors feel that additional clarification on this definition would have been beneficial. It was clear in the responses that educators would like to see examples of both diversity and choice of assessment where they have been implemented in their own specific discipline/programme. Therefore, a key recommendation is that educators need to have knowledge of what assessment students are doing, or have done in the programme, to understand what is familiar. In addition, incentives to share examples within teaching and learning circles as well as among discipline-specific communities is clearly required. Institutions can make this process easier through local publication and showcasing.

One of the interesting findings of this research, is that despite the fact that time and resources, in line with other studies, were among the key general barriers to diversifying assessment, when exploring the examples of implementations there was no significant correlation between resources and the perception of the success of the implementation. It may well be that the assessment diversification due to COVID-19 created a context in which some of the educators did not require significant resources. Alternatively it is the perception, rather than the reality, of the required time which may prevent further implementation of diversity and choice within higher education. In this particular context, the findings need to be interpreted with caution.

Grade inflation was listed as a significant barrier to implementation of diversity and choice of assessment. Fear of grade inflation appears to run counter-intuitive to supporting student success. Assessment methods should align with the learning outcomes of the module, allowing students to demonstrate that they have met these outcomes by demonstrating their knowledge and understanding. Therefore, in a criterion-referenced approach if a student achieves the outcomes they should achieve the grade. It seems, however, that many educators fear the perception that their module is ‘easy’ and worry about the consequences of a skewed grade distribution. In an institutional context where criterion-referenced assessment is used, as in this study, it seems that there is some work to be done to realise the implications of assessment enhancements on grades and how to handle these fairly. It requires institutions to explore this in their assessment policies.

In conclusion, access to higher education is not enough, we also need to ensure the growing diverse cohorts of student also have an equitable chance to succeed. Diversifying assessment away from a reliance on the examination is one way to support a range of avenues to enhance student success (Advance HE, Citation2019; National Forum, Citation2019). The ‘micro-, meso-, macro-level of an educational system should be aligned to develop clear goals and reference points to guide innovative assessment’ (Kapsalis et al., Citation2019, p. 96). The barriers, benefits and enablers highlighted in this study, the authors hope, should guide this diversification.

Ethical procedure

This study was carried in an ethical manner, having been approved by the University College Dublin Ethics Committee on 20 February 2020 (UCD Research Ethics Reference Number: HS-E-20-33-ONeill-Padden).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Geraldine O’Neill

Dr Geraldine O’Neill is an Associate Professor and educational developer in UCD Teaching & Learning, University College Dublin. Her research and practical experience is in the area of assessment, feedback and curriculum design. She led a National Forum assessment project from 2016 to 2018 and was recently awarded one of the inaugural National Forum Teaching and Learning Research Fellowships. In 2018, she was awarded a UK HEA Principal Fellowship.

Lisa Padden

Dr Lisa Padden is Project Lead for University College Dublin’s University for All initiative. University for All is UCD’s whole-institution approach to student inclusion encompassing strategy and policy, teaching, learning and assessment, student supports and services, the built environment and technological infrastructure. Lisa’s research interests include Universal Design for Learning, widening participation, equitable access to education, and student inclusion.

References

- Advance HE. (2019). Essential frameworks for enhancing student success. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2020-05/Enhancing%20Student%20Success%20in%20Higher%20Education%20Framework.pdf

- AHEAD. (2020). Students with disabilities engaged with support services in higher education in Ireland 2018/19. https://www.ahead.ie/userfiles/files/Participation/AHEAD_Research_Report_2020_-digital.pdf

- Armstrong, L. (2014). Barriers to innovation and change in higher education. TIAA-CREF Institute. https://www.tiaainstitute.org/sites/default/files/presentations/2017-03/Armstrong_Barriers%20to%20Innovation%20and%20Change%20in%20Higher%20Education.pdf

- Bevitt, S. (2015). Assessment innovation and student experience: A new assessment challenge and call for a multi-perspective approach to assessment research. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(1), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.890170

- CAST. (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.2. CAST: Wakefield, MA, USA. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

- European University Association (EUA). (2020). Student assessment: Thematic peer group report: Learning & teaching paper # 10. https://eua.eu/resources/publications/921:student-assessment-thematic-peer-group-report.html

- Flick, U. (2014). An introduction to qualitative research (5th ed.). Sage.

- Garside, J., Nhemachena, J. Z., Williams, J., & Topping, A. (2009). Repositioning assessment: Giving students the ‘choice’ of assessment methods. Nurse Education in Practice, 9(2), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2008.09.003

- Gibbs, G., & Dunbar-Goddet, H. (2009). Characterising programme-level assessment environments that support learning. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(4), 481–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930802071114

- Higher Education Authority (HEA). (2015) . National plan for equity of access to higher education, 2015–2019.

- Hounsell, D., Falchikov, N., Hounsell, J., Klampfleitner, M., Huxham, M., Thomson, K., & Blair, S. (2007). Innovative assessment across the disciplines: An analytical review of the literature. Final report. Higher Education Academy. http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/assets/documents/teachingandresearch/Innovative_assessment_LR.pdf

- Jakovljevic, M. (2019). Criteria for empowering innovation in higher education. Africa Education Review, 16(4), 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/18146627.2017.1369855

- Jones, A. (2004). A review of the research literature on barriers to the uptake of ICT by teachers. Becta. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/1603/1/becta_2004_barrierstouptake_litrev.pdf

- Kapsalis, G., Ferrari, A., Punie, Y., Conrads, J., Collado, A., Hotulainen, R., Rämä, I., Nyman, L., Oinas, S., & Ilsley, P. (2019). Evidence of innovative assessment: Literature review and case studies. European Commission and EU Science Hub.

- Kirkland, K., & Sutch, D. (2009). Overcoming the barriers to educational innovation: A literature review. Futurelab. https://www.nfer.ac.uk/publications/FUTL61/FUTL61.pdf

- Lok, B., McNaught, C., & Young, K. (2016). Criterion-referenced and norm-referenced assessments; Compatibility and complementarity. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(3), 450–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1022136

- Medland, E. (2016). Assessment in higher education: Drivers, barriers and directions for change in the UK. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.982072

- Mercer-Mapstone, L., & Bovill, C. (2019). Equity and diversity in institutional approaches to student–staff partnership schemes in higher education, Studies in Higher Education, (45)12, 2541-2557, doi: 10.1080/03075079.2019.1620721

- Mogey, N., Purcell, M., Paterson, J. S., & Burk, J. (2019). Handwriting or typing exams – Can we give students the choice? (Version 1). Loughborough University. https://hdl.handle.net/2134/5555<img src=“” alt=“” class=“iCommentClass icp_sprite icp_add_comment chk-comment iCommentExist” data-username=“Geraldine O’neill” neill'=“” data-userid=“93627” data-content=“Mogey et al needs to be 2019 everywhere” data-time=“1612023143709” data-rejcontent=“” data-cid=“3” id=“Sat Jan 30 2021 16:12:23 GMT+0000 (Greenwich Mean Time)” corr_ord_id=“14” id0=“3” data-username0=“Geraldine O” data-userid0=“93627” data-content0=“Check Tagging” title=“Mogey et al needs to be 2019 everywhere” data-radio=“xmlradioYTS” data-userid-id2=“93627” data-username-user2=“Geraldine O’neill”>

- Murray, L., Moore, A., Hooper, L., Menzies, V., Cooper, B., Shaw, N., & Rueckert, C. (2019). Dimensions of student success: A framework for defining and evaluating support for learning in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(5), 954–968. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1615418

- National Forum. (2016). Profile of assessment practices in Irish higher education. National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching & Learning in Higher Education. https://www.teachingandlearning.ie/publication/profile-of-assessment-practices-in-irish-higher-education/

- National Forum. (2019). Understanding and enabling student success in Irish higher education. National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching & Learning in Higher Education. https://www.teachingandlearning.ie/publication/understanding-and-enabling-student-success-in-irish-higher-education/

- O’Neill, G. (Ed.). (2011). A practitioner’s guide to choice of assessment methods within a module. UCD Teaching and Learning. https://www.ucd.ie/teaching/t4media/choice_of_assessment.pdf

- O’Neill, G. (2017). It’s not fair! Students and educators views on the equity of the procedures and outcomes of students’ choice of assessment methods. Irish Educational Studies, 36(2), 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2017.1324805

- Popham, J. W. (2014). Criterion-referenced measurement: Half a century wasted? Educational Leadership, 71(6), 62–68. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1043719

- Seldomridge, L. A., & Walsh, C. M. (2018). Waging the war on clinical grade inflation the ongoing quest. Nurse Educator, 43(4), 178–182. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000000473

- Tannock, S. (2017). No grades in higher education now! Revisiting the place of graded assessment in the reimagination of the public university. Studies in Higher Education, 42(8), 1345–1357. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1092131

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2014) . International standard classification of education ISCED 2013.

- Zhao, Y., Pugh, K., Sheldon, S., & Byers, J. (2002). Conditions for classroom technology innovations. Teachers College Record, 104(3), 482–515. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9620.00170