ABSTRACT

The global pandemic has forced academics to engage in remote doctoral supervision, and the need to understand this activity is greater than ever before. This contribution involved a cross-field review on remote supervision pertinent in the context of a global pandemic. We have utilised the results of an earlier study bringing a supervision model into a pandemic-perspective integrating studies published about and during the pandemic. We identified themes central to remote supervision along five theory-informed dimensions, namely intellectual/cognitive, instrumental, professional/technical, personal/emotional and ontological dimensions, and elaborate these in the light of the new reality of remote supervision.

Introduction

In the COVID-19 pandemic, doctoral supervision has become remote and largely gone online. There were examples of remote doctoral supervision prior to the pandemic (Nasiri & Mafakheri, Citation2015); however, it is not until now that academics on a broad scale have engaged in remote doctoral supervision. Throughout the pandemic, remote doctoral supervision has merged, and sometimes confused, the professional and the private, the home and the institution, and the physical and the digital. The home has become a proxy of the institution in a very tangible manner. The digital has become a predominant characteristic of any supervisory or research meeting between individuals. Notions of supervision, being and becoming academics, even notions of academia, may have changed in lasting ways. We present an analysis of the changed landscape of supervision in the current reality of doctoral candidates and supervisors.

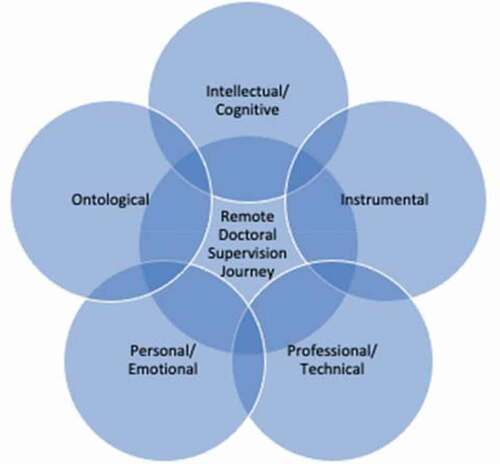

We explore what can be learned from the established and emerging literature on supervision that will be of relevance for understanding and developing remote doctoral supervision. To situate this work, we start from the five dimensions of doctoral learning journeys (Wisker et al., Citation2010/2011/2011): intellectual/cognitive, instrumental, professional/technical, personal/emotional and ontological (see ). These five dimensions account for doctoral candidates’ ‘learning leaps’ or, alternatively, ‘stuck places’ (Wisker et al., Citation2010/2011/2011, p. 22). We posed the following research question: What are the challenges and affordances of remote doctoral supervision?

Figure 1. Remote supervision of doctoral candidates and their research across the five dimensions of doctoral learning journeys (adapted from Wisker et al., Citation2010/2011/2011)

This work provides a contribution to literature and practice by extending the influential Doctoral Learning Journeys model to the new reality of remote doctoral supervision necessitated by the pandemic. Our analysis emphasises the ways that remote doctoral supervision affects the possibilities for doctoral candidates to make the kinds of learning leaps that are essential to degree progress (Wisker, Citation2010).

Method

We revisited recent literature on sound supervision processes and challenges, and remote supervision in particular, and aligned it with the adapted Doctoral Learning Journeys model. This contribution draws on literature about remote supervision pertinent in the context of the current pandemic and incorporates knowledge exchange within the author team about current challenges, affordances and effective practices. The Doctoral Learning Journeys model (Wisker et al., Citation2010/2011/2011) provided a scaffold for structuring our exchanges of knowledge and experience and analysing published literature relevant to understanding doctoral supervision in the context of the current pandemic.

We applied thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) on two levels. At one level, we searched literature on the five dimensions of the Doctoral Learning Journeys model, using keywords, such as ‘remote’, ‘distance’ and ‘online’. The authors research different aspects of doctoral learning and supervision as cued in the biographical notes, and these diverse experiences informed the selection of literature presented here. At another level, we identified challenges (i.e. aspects that restrain, impede or hamper) and affordances (i.e. aspects that facilitate or enrich) for remote doctoral supervision in the selected literature.

Results

We frame our analysis of challenges and affordances in remote supervision around the five dimensions of the Doctoral Learning Journeys model (Wisker et al., Citation2010/2011/2011).

Intellectual/cognitive dimension

Supervision involves supporting doctoral candidates in gaining knowledge, provoking critical thinking, and learning practical skills through feedback, demonstration, and dialogue. Supervisors provide structure to generate clear goals and expectations, advice and factual information to plan and conduct research, and practical assistance and resources to teach and complete research tasks (Overall et al., Citation2011). Supervision also entails individually responsive and developmental dialogues to ‘nudge’ research thinking and articulation (Wisker et al., Citation2003) and scaffolding to help candidates develop independent critical thinking and research skills (Mullen, Citation2020; Odena & Burgess, Citation2015).

Remote supervision transcends the limitations of physical distance and is a viable alternative to impart knowledge despite the constraints of time, space, costs, and even politics (Ghani, Citation2020). It is possible to screen share written work in progress and to have mutually beneficial, intellectual dialogues online (Wisker et al., Citation2003). Digital platforms allow asynchronous reviewing and opportunities for reflection (Miller, Citation2020). Given the richness of online interactions, doctoral candidates’ satisfaction with remote supervision may not be significantly weaker than for in-person supervision (Tarlow et al., Citation2020). However, demonstrations and hands-on assistance are challenging online (Gill et al., Citation2020), which has implications for cognitive engagement (Williamson & Williamson, Citation2020). Online feedback lacking auditory, visual, and physical cues may also be difficult to receive and interpret (Bengtsen & Jensen, Citation2015). Receiving both written and audio feedback supports a more in-depth cognitive presence than either mode alone (Rockinson-Szapkiw, Citation2012). Importantly, however, remote supervision alone may impede development of the academic atmosphere unless concerted efforts are made to build community. Cognitive engagement requires attention, presence, time, and possibilities to connect with role models in the field (Williamson & Williamson, Citation2020).

Instrumental dimension

Both access and engagement with rules and regulations relate to the instrumental domain. Access to a stable internet connection and technological tools that facilitate online supervision can be problematic when candidates are spread across the globe, and experience unequal technology or skill, requiring flexibility on the part of supervisor and candidate. Supervisors tend to make technological choices and maintain control over the functions (screen sharing, etc.), which may exacerbate power dynamics when candidates have fewer resources (Alebaikan et al., Citation2020).

Pedagogical work in the current pandemic has necessitated the adoption of alternative engagement strategies using various digital devices and platforms to enhance accessibility to relevant content, which might be affected by individual differences in technological literacy (Nasiri & Mafakheri, Citation2015; Sussex, Citation2008) and training (Unwin, Citation2007). Supervisors need to spend time and effort to manage the online environment (Kumar et al., Citation2020), to agree on supervision arrangements and to build trust in the absence of nonverbal cues and informal interactions (Kumar & Johnson, Citation2019).

As a result of the pandemic, many doctoral candidates meet with their supervisors at a distance, and new cohorts have likely not met their supervisors in person. Distance candidates with pre-existing relationships with their supervisors may be reluctant to reach out to supervisors with problems via email (Kumar et al., Citation2020). A planned, structured supervision ‘sandwich’ of kindly supportive personal interactions to start and finish supervision, and engagement with intellectual work, research, writing and developmental dialogues is beneficial to candidate interaction and progress (Wisker, Citation2020).

Professional/technical dimension

Mentors and supervisors have long focused on the importance of supporting candidates’ development of relevant research, technical, and professional skills to sustain their postgraduate studies and prepare them for a range of potential future careers (Kumar & Johnson, Citation2017; Mullen, Citation2020; Sinche et al., Citation2017). Extensive attention has been devoted to doctoral study as a form of research apprenticeship (Exter & Ashby, Citation2019; Mullen, Citation2020). Prior work has emphasised in particular the powerful learning potential of working side-by-side with other researchers as a means for doctoral candidates to develop research and technical skills, adopt identities as researchers, and become socialised as scholars in their chosen fields (Blaney et al., Citation2020; Maher et al., Citation2019; McGinn et al., Citation2013).

Diminished opportunities for research apprenticeship in remote doctoral supervision had already been acknowledged pre-pandemic (Kumar & Johnson, Citation2019). These challenges became more acute during the pandemic due to restricted access to research sites (Maranda et al., Citation2020; Sohrabi et al., Citation2021), especially when plans to collect first-hand data have been supplanted by a necessity to use existing data or shift to data that could be gathered from remote home locations (Gardner, Citation2020; Herbert, Citation2020; Jamal, Citation2020). Switching data or research foci may be particularly challenging for candidates and supervisors when there is no opportunity to sit together to engage in the research (Kumar & Johnson, Citation2017). Pandemic-related dislocation may also limit informal opportunities for discussion (Nasiri & Mafakheri, Citation2015). Disruptions to placements and field experiences have also diminished candidates’ access to field-based mentors who typically complement the support available from doctoral supervisors (Dempsey et al., Citation2021; Lasater et al., Citation2021).

Much attention has understandably focused on the limitations and challenges associated with the pandemic. There are, however, new or enhanced opportunities that have become available. Candidates with transferable skills have been called upon to contribute to vaccine administration, COVID-19 testing, and public health contact tracing. Whether involved directly or not in formalised practicum placements required for graduation or external opportunities presented in the current context, paid or unpaid, credit or non-credit, candidates have learned and applied new skills that may shape their future careers. Desai et al. (Citation2020) describe the clinical skills and ethics-related competencies that professional psychology doctoral candidates have developed as their programmes have shifted in response to the pandemic. Such opportunities would normally not arise so early or perhaps at all, in clinical psychology practice. For some, time away from the usual on-site work tasks has also created time and space for additional online training (Cheng & Song, Citation2020). It is important, however, that candidates receive encouragement from supervisors to see these new opportunities as enhancements rather than distractions from their studies.

During this time of physical distancing, travel restrictions, and capacity reductions, the vast majority of academic conferences and seminars have shifted to virtual formats, which has enhanced accessibility in promising ways that are expected to have lasting effects in a post-pandemic era (Chacón‐Labella et al., Citation2021; Sarabipour, Citation2020). It is challenging, however, for virtual offerings to incorporate the informal interactions, shared meals, and socialising functions that contribute to relationship building and knowledge sharing at in-person scholarly events (Cheng & song, Citation2020; Sohrabi et al., Citation2021; Wang & DeLaquil, Citation2020). Such informal and semi-formal activities have a formative influence on scholarly identity development (James & Lokhtina, Citation2018; McAlpine et al., Citation2009). Supervisors have felt challenged to make up for these shortcomings for doctoral candidates (Lasater et al., Citation2021), especially while they too may be feeling the absence of colleagues (Metcalfe & Blanco, Citation2021).

Personal/emotional dimension

Doctoral supervision has been characterised as an emotional venture (Doloriert et al., Citation2012). It is important to create time and space within the supervisory relationship to discuss the personal effects of the pandemic (Cameron et al., Citation2021). Research on distance education doctoral programs indicates that doctoral candidates are more likely to report feeling isolated and dissatisfied with doctoral supervision in online than in blended programs (Erichsen et al., Citation2014). Remote supervision creates additional challenges to the process of interaction (Gray & Crosta, Citation2019).

Emotional talk plays a different role in online than in-person settings (Zembylas, Citation2008). While sharing emotions in online learning may allow for taking perspective and creating a supportive emotional climate, it could intensify power and emotion dimensions (Doloriert et al., Citation2012). Supervisors and candidates need to manage a ‘delicate balance’ (Bastalich, Citation2017, p. 1147) and a high degree of adaptability. Heightened levels of stress, anxiety, depression and loneliness have emerged throughout the pandemic (Byrom, Citation2020; Deznabi et al., Citation2021). Without day-to-day interactions, there are fewer informal opportunities to engage with other scholars (Wang & DeLaquil, Citation2020). Working through these challenges requires compassion for self and others as plans, expectations and needs continue to evolve in unpredictable ways throughout the pandemic and recovery (Cameron et al., Citation2021). Now more than ever, supervisors need to prioritise equity and well-being in their interactions with doctoral candidates (Cameron et al., Citation2021; Lasater et al., Citation2021; Nocco et al., Citation2021).

Ontological dimension

The so-called ontological turn in higher education (Dall’Alba & Barnacle, Citation2007) emphasises intersections among personal being and becoming, knowledge practices and academic agency in a given setting. Pre-pandemic supervisors developed their habitus or dispositions for supervision in response to the structured system of social relations and procedures (Bourdieu, Citation1990), which may be incompatible with remote supervision. They may need to reposition their habitus and negotiate over the means and ways of engaging with/in the new social context of their institutions, which may necessitate additional support and facilitation from an institutional level. Supervisors who joined a new remote supervision setting in the pandemic may experience unfamiliar practices and expectations due to a new structure of social relations, which may prompt insecurity (see James & Lokhtina, Citation2018).

While the notion of ontology in higher education has long been connected to the condition of navigating in an unknown and unforeseeable future (Barnett, Citation2004), the focus has often been on unpredictable university and higher education futures – rather than unpredictable societal and cultural futures as faced in the current pandemic. In this context, we connect the notion of the ontological to academic being and becoming in relation to the meaning of the home (a ‘home-ontology’) (Nørgård & Bengtsen, Citation2016). Not only are supervisors and candidates working from home in a physical and socio-material sense of the term, but ‘homeliness’ in the world more generally has been disturbed and challenged. Heidegger’s (Citation2001, Citation2011) concepts of the home and the notion of dwelling provide a helpful lens for how the meaning and understanding of home, in the current situation, travel across physical, digital, institutional, professional, private, epistemic, and pedagogical realms. Are supervisors and candidates engaging in PhD supervision from home, or has the home itself become entangled into discursive and academic spaces and embedded into research and supervision practices?

It is key that supervisors and candidates find their home, and find themselves at home, in remote supervision to avoid splintering of the contact, diffusion of focus and disruption of the learning dialogue. To Heidegger (Citation2001, Citation2011), the home and the process of homecoming is not necessarily related to the home as a socio-physical place. To be at home does not necessarily mean to be physically at one’s home address – but this is exactly the case at the moment; the paradox is that supervisors and candidates have to try to be at home in the supervision while they are at home, albeit a home that has changed due to the pandemic. Paraphrasing Heidegger (Citation2011, p. 164), they are searching for a supervisory ‘homecoming’ and longing for a pedagogical ‘homeland’ – where ‘homeland … is [the] nearness to being’ and overcoming of the ‘homelessness’ of their pandemic homes. In remote supervision, supervisors and candidates must try to hold the home together and ensure a ‘pedagogical homecoming’. Creating a pedagogical homeliness in remote supervision requires that supervisors and candidates recognise, allow and acknowledge the tensions, paradoxes, vulnerability and exposedness that their homes express.

Conclusions

This contribution synthesises what can be learned from the established and emerging literature, and the dynamic exchanges of the experiences of the team of authors, utilising the supervision-focused framework adapted from the Doctoral Learning Journeys project (Wisker et al., Citation2010/2011/2011). In the current pandemic, remote doctoral supervision has revealed both challenges and affordances for candidates and supervisors. By organising the literature according to the dimensions of the doctoral learning journey, we have extended that earlier model to consider supervisor and candidate experiences in the new reality of remote supervision in a pandemic. Exploring these intertwined dimensions within pandemic conditions brings new perspectives to learning leaps and stuck places in doctoral learning and supervision (Wisker, Citation2010; Wisker et al., Citation2010/2011/2011). Our work contests some of the traditional dichotomies found in the literature, namely, doctoral supervision either as a physical or a digital pedagogy with focus on either formalised meetings or informal extracurricular activities, and being either an institutional(ised) pedagogy or a lifeworld trajectory. We argue that entangled, or ecological, doctoral pedagogies can overcome such dichotomies. Further research avenues may be pursued around pedagogical and lifeworld entanglements in doctoral supervision.

Finally, how we conceptualise the spaces we function in is not irrelevant. The home has become an in-between space, simultaneously ‘everywhere’ and ‘nowhere’. It has been invaded by work, study and socialising (on-screen) but has not stopped being a physical home. The cat still insists on attention as it walks across a keyboard during a sensitive meeting, and the (perhaps now home-schooled) children are still there – roaming around (often noisily!) in the background, or interrupting with cries for help as they have overcooked their lunch causing smoke to engulf the kitchen. Supervisors and candidates are everywhere and nowhere at the same time, and the supervisory ideals of attention, focus and listening have become challenged. Supervisors and candidates may not be at home in their supervision practices at the moment, but sharing this pedagogical homelessness with each other may create a new common ground – a remote pedagogical home.

Acknowledgments

This paper arose through an online seminar for SIG 24 Researcher Education and Careers of the European Association for Research on Learning and Instruction. The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gina Wisker

Gina Wisker is a doctoral supervisor and Assistant Professor in the International Centre for Higher Education Management, University of Bath, Professor 11 at the University of the Arctic, Tromso, Norway, visiting professor at the University of Johannesburg and Emeritus Professor of the University of Brighton. Her interests include researcher learning, doctoral supervision, higher education curriculum development, internationalisation, decolonisation, writing for academic publication, and literature.

Michelle K. McGinn

Michelle K. McGinn is Associate Vice-President Research and Professor of Education at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario, Canada. Her primary interests relate to research collaboration, researcher development, scholarly writing, and ethics in academic practice for postgraduate students and established scholars.

Søren S. E. Bengtsen is Associate Professor in higher education at the Department of Educational Philosophy and General Education, Danish School of Education, Aarhus University, and Co-Director of the ‘Centre for Higher Education Futures’. His main research areas include the philosophy of higher education, educational philosophy, higher education policy and practice, and doctoral education and supervision.

Irina Lokhtina is a Lecturer in Human Resource Management and Leadership at the University of Central Lancashire, Cyprus. She is a Certified Educator for Vocational Training and Executive Courses, and Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (UK). Her research interests are related to workplace learning, mentoring, academic identity development and well-being.

Faye He is a postdoctoral researcher in the graduate school of education at Peking University, Beijing. Her research interests relate to academic capabilities, supervisor–supervisee relationships, peer apprenticeship in doctoral education and teachers’ work and life in rural areas of China.

Solveig Cornér is a Postdoctoral researcher at the Faculty of Educational Sciences, University of Helsinki. Her research interests include social support and well-being in doctoral education, and research integrity.

Shosh Leshem is currently Professor in education at Kibbutzim Academic College of Education, Israel; Middlebury College, Vermont, USA; and Research Associate at Stellenbosch University, South Africa. Her main research interest areas and publications include doctoral education and supervision, teacher education, mentoring, teaching foreign/second languages.

Kelsey Inouye is currently a Research Assistant at the Department of Education, University of Oxford. Her research focuses on doctoral and research writing, post-PhD careers, and academic publishing practices.

Erika Löfström

Erika Löfström is Professor of Education at the University of Helsinki, Faculty of Educational Sciences where she leads elementary teacher education. Her research interests include research ethics and integrity, ethics in doctoral supervision, and teacher identity.

References

- Alebaikan, T., Bain, Y., & Cornelius, S. (2020). Experiences of distance doctoral supervision in cross-cultural teams. Teaching in Higher Education, 1–18. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2020.1767057

- Barnett, R. (2004). Learning for an unknown future. Higher Education Research & Development, 23(3), 247–260. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436042000235382

- Bastalich, W. (2017). Content and context in knowledge production: A critical review of doctoral supervision literature. Studies in Higher Education, 42(7), 1145–1157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1079702

- Bengtsen, S. S., & Jensen, G. S. (2015). Online supervision at the university: A comparative study of supervision on student assignments face-to-face and online. Tidsskriftet Læring Og Medier, 8(13), 1–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7146/lom.v8i13.19381

- Blaney, J. M., Kang, J., Wofford, A. M., & Feldon, D. F. (2020). Mentoring relationships between doctoral students and postdocs in the lab sciences. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 11(3), 263–279. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-08-2019-0071

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Polity.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Byrom, N. (2020). The challenges of lockdown for early-career researchers. eLife, 9 June 12 . Article e59634. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.59634

- Cameron, K., Daniels, L., Traw, E., & McGee, R. (2021). Mentoring in crisis does not need to put mentorship in crisis: Realigning expectations. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, 5(1 1–2), Article e16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2020.508

- Chacón‐Labella, J., Boakye, M., Enquist, B. J., Farfan‐Rios, W., Gya, R., Halbritter, A. H., Middleton, S. L., Van Oppen, J., Pastor-Ploskonka, S., Strydon, T., Vandvik, V., & Geange, S. R. (2021). From a crisis to an opportunity: Eight insights for doing science in the COVID‐19 era and beyond. Ecology and Evolution, 11(8), 3588–3596. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.7026

- Cheng, C., & Song, S. (2020). How early-career researchers are navigating the COVID-19 pandemic. Molecular Plant, 13(9), 1229–1230. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2020.07.018

- Dall’Alba, G., & Barnacle, R. (2007). An ontological turn for higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 32(6), 679–691. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070701685130

- Dempsey, A., Lanzieri, N., Luce, V., De Leon, C., Malhotra, J., & Heckman, A. (2021). Faculty respond to COVID-19: Reflections-on-action in field education. Clinical Social Work Journal. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-021-00787-y

- Desai, A., Lankford, C., & Schwartz, J. (2020). With crisis comes opportunity: Building ethical competencies in light of COVID-19. Ethics & Behavior, 30(6), 401–413. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2020.1762603

- Deznabi, I., Motahar, T., Sarvghad, A., Fiterau, M., & Mahyar, N. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the academic community. Results from a survey conducted at University of Massachusetts Amherst. Digital Government: Research and Practice, 2(2), 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/3436731

- Doloriert, C., Sambrook, S., & Stewart, J. (2012). Power and emotion in doctoral supervision: Implications for HRD. European Journal of Training and Development, 36(7), 732–750. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/03090591211255566

- Erichsen, E., Bolliger, D., & Halupa, C. (2014). Student satisfaction with graduate supervision in doctoral programs primarily delivered in distance education settings. Studies in Higher Education, 39(2), 321–338. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2012.709496

- Exter, M. E., & Ashby, I. (2019). Using cognitive apprenticeship to enculturate new students into a qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 24(4), 873–886. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol24/iss4/16/

- Gardner, B. (2020, June 17). Challenges of doing research in a pandemic: Reframing, adapting and introducing qualitative methods International Journal of Social Research Methodology . https://ijsrm.org/2020/06/17/challenges-of-doing-research-in-a-pandemic-reframing-adapting-and-introducing-qualitative-methods/

- Ghani, F. (2020). Remote teaching and supervision of graduate scholars in the unprecedented and testing times. Journal of the Pakistan Dental Association, 29(S), 36–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.25301/JPDA.29S.S36

- Gill, S. D., Stella, J., Blazeska, M., & Bartley, B. (2020). Distant supervision of trainee emergency physicians undertaking a remote placement: A preliminary evaluation. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 32(3), 446–456. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1742-6723.13440

- Gray, M. A., & Crosta, L. (2019). New perspectives in online doctoral supervision: A systematic literature review. Studies in Continuing Education, 41(2), 173–190. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2018.1532405

- Heidegger, M. (2001). Poetry, language, thought. HarperCollins.

- Heidegger, M. (2011). Basic writings. Routledge.

- Herbert, M. B. (2020, August 6). Creatively adapting research methods during COVID-19 International Journal of Social Research Methodology . https://ijsrm.org/2020/08/06/creatively-adapting-research-methods-during-covid-19/

- Jamal, A. (2020, November 17). Exploring unplanned data sites for observational research during the pandemic lockdown International Journal of Social Research Methodology . https://ijsrm.org/2020/11/17/exploring-unplanned-data-sites-for-observational-research-during-the-pandemic-lockdown/

- James, N., & Lokhtina, I. (2018). Feeling on the periphery? The challenge of supporting academic development and identity through communities of practice. Studies in the Education of Adults, 50(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2018.1520561

- Kumar, S., & Johnson, M. (2017). Mentoring doctoral students online: Mentor strategies and challenges. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 25(2), 202–222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2017.1326693

- Kumar, S., & Johnson, M. (2019). Online mentoring of dissertations: The role of structure and support. Studies in Higher Education, 44(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1337736

- Kumar, S., Kumar, V., & Taylor, S. (2020). A guide to online supervision. UK Council for Graduate Education. http://www.ukcge.ac.uk/article/guide-to-online-supervision-457.aspx

- Lasater, K., Smith, C., Pijanowski, J., & Brady, K. P. (2021). Redefining mentorship in an era of crisis: Responding to COVID-19 through compassionate relationships. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 10(2), 158–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-11-2020-0078

- Maher, M. A., Wofford, A. M., Roksa, J., & Feldon, D. F. (2019). Doctoral student experiences in biological sciences laboratory rotations. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 10(1), 69–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-02-2019-050

- Maranda, V., Yakubovich, E., & Shanahan, M.-C. (2020). The biomedical lab after COVID-19: Cascading effects of the lockdown on lab-based research programs and graduate students in Canada. Facets, 5(1), 831–835. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1139/facets-2020-0036

- McAlpine, L., Jazvac‐Martek, M., & Hopwood, N. (2009). Doctoral student experience in education: Activities and difficulties influencing identity development. International Journal for Researcher Development, 1(1), 97–109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/1759751X201100007

- McGinn, M. K., Niemczyk, E., & Saudelli, M. G. (2013). Fulfilling an ethical obligation: An educative research assistantship. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 59(1), 72–91 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11575/ajer.v59i1.55678.

- Metcalfe, A. S., & Blanco, G. L. (2021). “Love is calling”: Academic friendship and international research collaboration amid a global pandemic. Emotion, Space and Society, 38, Article 100763. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2021.100763

- Miller, L. (2020). Remote supervision in primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic: The “new normal”? Education for Primary Care, 31(6), 332–336. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14739879.2020.1802353

- Mullen, C. A. (2020). Practices of cognitive apprenticeship and peer mentorship in a cross‐global STEM lab. In B. J. Irby, J. N. Boswell, L. J. Searby, F. Kochan, R. Garza, & N. Abdelrahman (Eds.), The Wiley international handbook of mentoring: Paradigms, practices, programs, and possibilities (pp. 243–260). Wiley.

- Nasiri, F., & Mafakheri, F. (2015). Postgraduate research supervision at a distance: A review of challenges and strategies. Studies in Higher Education, 40(10), 1962–1969. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.914906

- Nocco, M. A., McGill, B. M., MacKenzie, C. M., Tonietto, R. K., Dudney, J., Bletz, M. C., Young, T., & Kuebbing, S. E. (2021). Mentorship, equity, and research productivity: Lessons from a pandemic. Biological Conservation, 255, Article 108966. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2021.108966

- Nørgård, R. T., & Bengtsen, S. (2016). Academic citizenship beyond the campus: A call for the placeful university. Higher Education Research and Development, 35(1), 4–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1131669

- Odena, O., & Burgess, H. (2015). How doctoral students and graduates describe facilitating experiences and strategies for their thesis writing learning process: A qualitative approach. Studies in Higher Education, 42(3), 572–590. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1063598

- Overall, N. C., Deane, K. L., & Peterson, E. R. (2011). Promoting doctoral students’ research self-Efficacy: Combining academic guidance with autonomy support. Higher Education Research and Development, 30(6), 791–805. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2010.535508

- Rockinson-Szapkiw, A. J. (2012). Should online doctoral instructors adopt audio feedback as an instructional strategy? Preliminary evidence. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 7, 245–258. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.28945/1595

- Sarabipour, S. (2020). Research culture: Virtual conferences raise standards for accessibility and interactions. Elife, 9 November 4 , Article e62668. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.62668

- Sinche, M., Layton, R. L., Brandt, P. D., O’Connell, A. B., Hall, J. D., Freeman, A. M., Harrell, J. R., Cook, J. G., Brennwald, P. J., & van Rijnsoever, F. J. (2017). An evidence-based evaluation of transferable skills and job satisfaction for science PhDs. PloS One, 12(9), Article e0185023. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185023

- Sohrabi, C., Mathew, G., Franchi, T., Kerwan, A., Griffin, M., Del Mundo, J. S. C., Ali, S. A., Agha, M., & Agha, R. (2021). Impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on scientific research and implications for clinical academic training. A review. International Journal of Surgery, 86 February , 57–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.12.008

- Sussex, R. (2008). Technological options in supervising remote research students. Higher Education, 55(1), 121–137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-006-9038-0

- Tarlow, K. R., McCord, C. E., Nelon, J. L., & Bernhard, P. A. (2020). Comparing in-person supervision and telesupervision: A multiple baseline single-case study. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 30(2), 383–393. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000210

- Unwin, T. (2007). Reflections on supervising distance-based PhD students. University of London. http://www.gg.rhul.ac.uk/ict4d/distance-based%20PhDs.pdf

- Wang, L., & DeLaquil, T. (2020). The isolation of doctoral education in the times of COVID-19: Recommendations for building relationships within person–environment theory. Higher Education Research & Development, 39(7), 1346–1350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1823326

- Williamson, D. G., & Williamson, J. N. (Eds.). (2020). Distance counseling and supervision: A Guide for Mental Health Clinicians. John Wiley & Sons.

- Wisker, G. (2020, August 18). Are we all still here? Remote supervision of doctoral candidates. The Hidden Curriculum in Doctoral Education. https://drhiddencurriculum.wordpress.com/

- Wisker, G., Morris, C., Cheng, M., Masika, R., Warnes, M., Trafford, V., Robinson, G., & Lilly, J. (2010/2011). . Higher Education Academy National Teaching Fellowship Scheme Project 2007–2010 (University of Brighton and Anglia Ruskin University). https://www.brighton.ac.uk/_pdf/research/education/doctoral-learning-journeys-final-report-0.pdf

- Wisker, G., Robinson, G., Trafford, V., Warnes, M., & Creighton, E. (2003). From supervisory dialogues to successful PhDs: Strategies supporting and enabling the learning conversations of staff and students at postgraduate level. Journal of Teaching in Higher Education, 8(3), 383–397. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510309400

- Wisker, G. (2010). The ‘good enough’ doctorate: Doctoral learning journeys. Acta Academica, 2010(sup–1), 223–242.

- Zembylas, M. (2008). Adult learners’ emotion in online learning. Distance Education, 29(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910802004852