ABSTRACT

We examine independent and joint influences of public service motivation (PSM), job prosocial impact, and job reward equity on public employee engagement. Using panel data collected from 56 public managers in Pakistan, we find that managers with high levels of PSM feel more engaged when they experience high reward equity but low job prosocial impact or when they experience high job prosocial impact but low reward equity. Managers with low to moderate levels of PSM, however, report being more engaged when both job reward equity and job prosocial impact are high. These findings provide a nuanced understanding of how PSM affects public employee engagement.

Introduction

Employee engagement has emerged as a key concept in human resource management (HRM) research and among HRM practitioners over the past two decades. Public sector organizations around the globe are implementing programmes designed specifically to improve employee engagement. For example, the Office of Personnel Management in the United States federal government is tracking predictors of employee engagement on an annual basis through administering surveys to improve agency performance and to recruit and retain talented employees (Hameduddin and Fernandez Citation2019). Similar efforts are being undertaken by governments in Australia, Canada, Ireland, and the United Kingdom (Hameduddin and Lee Citation2021).

A key reason behind such efforts is that employee engagement is positively correlated with organizationally beneficial work attitudes and behaviours (Borst et al. Citation2020). Hence, understanding factors that drive higher engagement among public sector employees has important implications. There is a large literature in general management research on the predictors of work engagement (Christian, Garza, and Slaughter Citation2011). Our study advances the literature by drawing on and connecting three separate lines of research investigating the important roles that public service values and outcomes can play in engaging public sector employees. Studies in public management have found that employee public service motivation (Bakker Citation2015; Borst Citation2018; Borst, Kruyen, and Lako Citation2019; De Simone et al. Citation2016; Levitats and Vigoda-Gadot Citation2019; Ugaddan and Park Citation2017), perceptions of their work’s prosocial impact (Freeney and Fellenz Citation2013) and perceptions of fairness in job-related rewards (Ghosh, Rai, and Sinha Citation2014; Kumasey, Delle, and Hossain Citation2021; Strom, Sears, and Kelly Citation2014) not only increase public employee engagement but also do so through similar mechanisms that strengthen the employee-organization relationship and the employee’s sense of meaningful accomplishment. Public service motivation (PSM) does this by increasing the general importance the employee places on the type of work (a more intrinsic desire to serve the public), while prosocial impact and work-related rewards do so by highlighting successful work accomplishments and the importance of these work outcomes for others.

Given that public management scholars argue that PSM, job prosocial impact, and job rewards influence public employee engagement through similar mechanisms, it is important to investigate the extent to which their influences are independent and additive, mutually reinforcing, or substitutive. Job prosocial impact and work-related rewards, for example, might strengthen the relationship between PSM and employee engagement by helping employees feel that their public service values are shared by the organization and are being realized in the work that they do (Borst, Kruyen, and Lako Citation2019; Corduneanu, Dudau, and Kominis Citation2020). Prosocial impact and rewards may also work independently of PSM. Prosocial impact and work-related rewards, for example, can enhance public employee engagement through other mechanisms highlighted as important by motivation theories in ways that do not require the presence of high levels of PSM (c.f., Adams Citation1963; Grant Citation2007; Wright Citation2007; Wright and Pandey Citation2008). Alternatively, given that all three factors can increase public employee engagement by improving perceptions of the importance of their work and person-job or person-organization fit, it is possible that they work in overlapping or redundant ways such that enhancing all three factors are not necessary to increase public employee engagement or that they may do so with diminishing rates of return.

The purpose of the current study is to examine these potential alternative explanations. We contribute to the growing literature on public employee engagement by assessing how PSM, perceptions of job reward equity, and job prosocial impact work together to enhance work engagement of a group of public sector managers, principals of vocational training institutes (VTIs) in Punjab, Pakistan. These public managers work in a challenging environment and under considerable resource constraints. They are not only responsible for the day-to-day management of the centres but also provide career counselling to at-risk youth in the community and help them find employment. They are also expected to develop partnerships with local businesses to leverage opportunities for at-risk youth and gather resources for their agencies. While the cultural context of our study is somewhat novel, VTI managers have job duties that are similar to the job duties of managers of job training programs in western countries (Herranz Citation2008).

Although many previous public management studies have examined performance of job training programs (c.f., Considine, Nguyen, and O’Sullivan Citation2018; Dias and Maynard-Moody Citation2007; Heinrich Citation1999, Citation2002), few have considered how PSM and day-to-day experiences of such managers shape their work engagement. In particular, we are interested to understand whether the influence of PSM on public managers’ work engagement is moderated by perceptions of reward equity and job prosocial impact over time. Drawing on existing research and theories of work motivation, we develop several nuanced theoretical expectations about how the relationship between PSM and VTI managers’ work engagement may be contingent on their perceptions of both job reward equity and prosocial impact. We test these theoretical expectations with data collected with surveys at seven points over three months from 56 VTI managers.

Our results show a positive association between PSM and repeated measures of work engagement. We also find that the VTI managers’ work engagement increase when they experience greater levels of prosocial impact of their work. While the perception of job reward equity does not appear to have a consistent direct influence on the managers’ work engagement, job reward equity, and job prosocial impact interact in ways to moderate the association between PSM and managers’ work engagement. Specifically, we observe that high PSM managers report being more engaged with their work when they perceive reward equity to be low but job prosocial impact to be high or when they perceive job prosocial impact to be low but perceive reward equity to be high. Managers with low to moderate levels of PSM, however, are more likely to be engaged when both reward equity and prosocial impact are high. In fact, our findings suggest that nearly half of our sample work under conditions where PSM is unrelated to employee engagement. Together, these findings provide new insight into how and when PSM and job-related factors affect public employee engagement in a developing country context.

Literature and hypotheses

Employee engagement

As noted previously, there is a vast academic and practitioner-oriented literature on employee engagement. Although a detailed review of which is beyond the scope of the current paper, work engagement is generally understood as ‘a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption’ (Schaufeli et al. Citation2002, 74). Thus, work engagement is a multidimensional construct that consists of three related components: vigour, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli et al. Citation2002). Vigour refers to experiencing high levels of energy and mental resilience while working; dedication is characterized as feeling a sense of significance, pride, and inspiration towards one’s work; absorption is characterized as being fully engrossed in one’s one work.

The benefits of engaged workers in public sector organizations are considerable. Kahn (Citation1990, 694) suggests that engaged workers invest their entire selves into their work. They find their work meaningful and bring all of their cognitive, emotional, and physical energies to performing their job role as well as possible (Kahn Citation1990). This perspective suggests that higher work engagement may lead to increased worker productivity and performance (Bakker Citation2015). Research shows that engaged workers are high performers, more willing to help their colleagues, and less likely to experience job burnout than those who are not engaged in their job (Christian, Garza, and Slaughter Citation2011). Although most of the research has been conducted in private sector organizations, some scholars have suggested that organizational characteristics more commonly associated with the public sector such as procedural and financial constraints, external oversight, and differences in goals and values may lead to different effects of employee engagement (Akingbola & van Den Berg Citation2019; Borst Citation2018; Perry and Vandenabeele Citation2015). But, even so, work engagement has been found to positively relate to employee in-role and extra-role performance in public sector organizations (Borst, Kruyen, and Lako Citation2019).

Public service motivation and impact

PSM theory suggests that individuals with a ‘predisposition to respond to motives grounded primarily or uniquely in public institutions and organizations’ (Perry and Wise Citation1990, 386) are more likely to pursue jobs in government as well as work harder and longer to satisfy their desire to help public and benefit society. Thus, it is not surprising that public management research often investigates the relationship between PSM and the beneficial employee behaviours and attitudes now commonly associated with employee engagement (Borst et al. Citation2020) as well as employee engagement itself (Borst, Kruyen, and Lako Citation2019; Levitats and Vigoda-Gadot Citation2019; Peretz Citation2020). Although a recent review of the literature found general support for these claims, the expected beneficial effects of PSM were only supported in 36% of the studies on turnover intention, 58% of the studies on individual performance, 62% of the studies on job satisfaction, and 68% of the studies on organizational commitment (Ritz, Brewer, and Neumann Citation2016).

One potential explanation for the inconsistent evidence of the relationship between PSM and beneficial employee attitudes and behaviours is that even if employees with higher PSM are drawn to work in public sector organizations, their work may not always sufficiently satisfy their desire to serve the public (Buchanan Citation1975; Steijn Citation2008; Wright, Hassan, and Christensen Citation2017). Employees with high PSM, for example, may hold views on what constitutes good public service that may seem to conflict with their organizations’ policies and procedures (Rainey Citation1982; Schott and Ritz Citation2018). In addition, jobs in public sector organizations often vary in terms of the difficulty in achieving or even just the ability to clearly see the positive impact of their work due to overly burdensome rules and administrative processes (Borst, Kruyen, and Lako Citation2019; Peretz Citation2020), the need to perform regulation work (such as policing or public inspections) where the contact with citizens are more often conflictual (De Simone et al. Citation2016; Kjeldsen Citation2014) or administrative work where the contact with beneficiaries and the ability to see clear service outcomes may not be as readily apparent (Bellé Citation2013, Citation2014; Bro, Andersen, and Bøllingtoft Citation2017). While PSM can increase work engagement and other desirable employee outcomes because public employees with high levels of PSM are more likely to find their work important and meaningful (Bakker Citation2015), it is difficult for public employees to maintain their effort and commitment to public service when they don’t feel that their efforts are successful (van Loon et al Citation2018; Wright Citation2007).

Helping employees see and understand how their work benefits citizens and society can initiate and sustain their motivation and commitment in two important ways. First, seeing the prosocial impact of their work helps employees feel a sense of meaning and personal responsibility for achieving outcomes that have significance to themselves or others (Hackman and Oldman Citation1980). A second albeit interrelated mechanism is that feelings of successful accomplishment and goal attainment can increase the employee’s confidence in their abilities which, in turn, increases their likelihood to attempt and persist in current and future public service activities even when facing obstacles (Grant Citation2007; Peretz Citation2020; Wright Citation2007). In other words, public employees are more likely to ‘persist in expending effort toward goal attainment if they see the relationship between what they are doing and the attainment of outcomes important to them’ (Latham, Borgogni, and Petitta Citation2008, 395).

Thus while PSM is likely to increase employee engagement through improving perceptions of the importance of their work (i.e. valence) and person-organization fit, job prosocial impact helps strengthen that relationship through its influence on other important factors (self-efficacy, instrumentality, behaviour-outcome contingencies, and achieving meaningful outcomes) that serve as the foundation for many of the most prominent and highly regarded work motivations theories (Miner Citation2005) including expectancy theory (Vroom Citation1964), job characteristics model (Hackman & Oldham Citation1980; Grant Citation2007) and goal theory (Latham, Borgogni, and Petitta Citation2008; Wright Citation2007). Public management research has also found that strategies to improve perceptions of the job prosocial impact can increase beneficial outcomes related to engagement such as job performance (Grant Citation2008), organizational commitment (Boardman and Sundquist Citation2009; Jensen Citation2018; Vogel and Willems Citation2020), and job satisfaction (Boardman and Sundquist Citation2009) regardless of their levels of PSM while other studies have illustrated how prosocial impact can strengthen the relationship between PSM and performance (Bellé Citation2013, Citation2014; Van loon et al Citation2018).

Although recent studies have begun to propose (Bakker Citation2015) and find a positive relationship between PSM and engagement (Borst Citation2018; Borst, Kruyen, and Lako Citation2019; De Simone et al. Citation2016; Levitats and Vigoda-Gadot Citation2019; Luu Citation2019; Peretz Citation2020; Ugaddan and Park Citation2017), job prosocial impact may enhance this relationship for the same reasons research suggests that it can enhance the relationship between PSM and performance, organizational commitment and job satisfaction. Prosocial impact not only can help strengthen employee’s experience of meaningfulness at work by highlighting how their desire to serve the public is being fulfilled, but it also enhances PSM’s ability to ‘strengthen the positive relationship between personal resources (e.g. optimism and self-efficacy) and work engagement’ (Bakker Citation2015, 729). Additional support for these claims is provided by research that has found a positive relationship between prosocial impact and employee engagement (Freeney and Fellenz Citation2013) and contends that the relationship between PSM and engagement ‘might depend upon on the degree to which employees feel that a particular organizational environment allowed them to fulfill their public service motives’ (Borst, Kruyen, and Lako Citation2019, 377; also see Bright Citation2007). Even so, additional research is necessary to enhance our understanding of and confidence in this relationship. Accordingly, we propose and test the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a: PSM is positively related to public managers’ work engagement.

Hypothesis 1b: The relationship between PSM and work engagement will be moderated by job prosocial impact such that PSM will have a stronger influence on manager engagement when perceived prosocial impact is high than when perceived prosocial impact is low.

Perceived job reward equity

One of the most common ways organizations try to influence employee engagement and behaviour is by providing extrinsic rewards and incentives. Although seeing a relationship between rewards and performance can incentivize behaviour and increase performance, their effectiveness in public organizations can be limited by both their application and attractiveness. Public sector organizations, particularly those in developing countries, face considerable resource and procedural constraints on their ability to provide performance-related rewards (Boyne, Poole, and Jenkins Citation1999; Perry, Engbers, and Jun Citation2009) and extrinsic rewards are thought to be less important to public employees because they are more likely to find the act of providing public service inherently rewarding (Perry and Wise Citation1990). Nevertheless, studies show that extrinsic rewards are not only important to individuals choosing government jobs (Asseburg et al. Citation2020; Christensen and Wright Citation2011; Dal Bó, Finan, and Rossi Citation2013; Wright and Christensen Citation2010) but also influence the importance that public employees place on their work (Wright Citation2007; Wright and Pandey Citation2008). Recent research suggests that, even after controlling for PSM, extrinsic rewards and performance recognition provided by their managers can increase public employee performance (Bellé Citation2015; Wright, Hassan, and Christensen Citation2017) and reduces counterproductive and unethical behaviour (Bashir and Hassan Citation2020).

One reason why extrinsic rewards and recognition are important even in the public sector is that their influence does not just rely on the economic value of the rewards to incentivize behaviour. In fact, many studies investigating the importance of extrinsic reward equity do so with measures that do not exclusively focus on (Hu, Schaufeli, and Taris Citation2013; Kumasey, Delle, and Hossain Citation2021; Strom, Sears, and Kelly Citation2014; Wright Citation2007) or even directly refer to pay or promotions (Ghosh, Rai, and Sinha Citation2014; Kurland and Egan Citation1999; Ohana and Meyer Citation2016). Drawing on the social exchange theory, organizational rewards and recognition are seen by employees as contributing to a state of interdependence between the employee and the organization based on trust, loyalty, and mutual commitments (Cropanzano and Mitchell Citation2005). Hence, rewards and recognition can also shape perceptions of the quality of the employee-organization relationship (Hassan Citation2021) and the match between the employee and the work factors considered to be related to employee engagement and burnout (Maslach, Schaufeli, and Leiter Citation2001).

A key way in which rewards and recognition increase employee engagement is through the role they play in establishing a sense of fairness and the norm of reciprocity (Bakker et al. Citation2000). When employees feel that they are receiving appropriate recognition for their work, they are more likely to feel that their relationship with the organization is based on mutual respect and appreciation. As a result, they are not only more likely to reciprocate with a greater commitment to and engagement in their work (Bakker et al. Citation2000; Cropanzano and Mitchell Citation2005; Gruman and Saks Citation2011; Hassan Citation2014) but also better able to cope with the demands of their job (Giauque, Anderfuhren-Biget, and Varone Citation2013; Hu, Schaufeli, and Taris Citation2013; Janssen Citation2001). In contrast, a lack of perceived fairness leads to greater distress and a tendency to restore fairness by psychologically withdrawing and disengaging themselves from their work (Adams Citation1963; Bakker et al. Citation2000; Buunk and Schaufeli Citation1999; Hassan Citation2014; Smets et al. Citation2004; Taris et al. Citation2001). Although arguments in support of this mechanism can be found in the public management literature for many years (Kurland and Egan Citation1999), recent studies have provided empirical support for the claim that employee perceptions of fairness in rewards can increase employee engagement (Ghosh, Rai, and Sinha Citation2014; Hassan Citation2013; Kumasey, Delle, and Hossain Citation2021; Strom, Sears, and Kelly Citation2014).

In other ways, employee perception of the fairness of job rewards functions very similarly to prosocial impact in its ability to enhance employee engagement. When employees receive recognition for their work it provides them with a sense of satisfaction and meaningfulness that is derived from a sense of personal responsibility for and knowledge of achieving outcomes that have significance to themselves or others (Hackman and Oldman 1980). These feelings of successful accomplishment and goal attainment also increase the employee’s confidence in their abilities which, in turn, increases their likelihood to attempt and persist in current and future public service activities even when facing obstacles (Grant Citation2007; Wright Citation2007).

As previously noted, rewards and recognition can help strengthen the interdependence between the employee and organization by illustrating their mutual commitment to shared values and goals (Maslach, Schaufeli, and Leiter Citation2001). This symbolic role of rewards may be particularly important for employees with high PSM because it suggests that their organization not only acknowledges the importance of their efforts but, in doing so, also signals that it shares the employees’ public service values (Wright and Pandey Citation2008; Wright, Hassan, and Christensen Citation2017). So while relying too much on extrinsic rewards to motivate employees may lower their engagement by crowding out or weakening the value placed on performing meaningful public service (Georgellis, Iossa, and Tabvuma Citation2011; Weibel, Rost, and Osterloh Citation2010), recognizing and rewarding employee performance can also help employees with high PSM strengthen their feelings of person-job and person-organization fit (Ohana and Meyer Citation2016; Steijn Citation2008; Wright and Pandey Citation2008). Even research on self-determination theory has suggested that extrinsic rewards are less likely to crowd out and may even enhance autonomous forms of motivation (like PSM) when rewards are ‘designed to be equitable and … acknowledge effective performance’ in autonomy-supportive environments (Gagne and Deci Citation2005, 354) or when the pursuit or use of the rewards help individual’s experience higher need satisfaction and well-being (Corduneanu, Dudau, and Kominis Citation2020). Under such conditions, performance-based rewards and recognition can help satisfy the basic need of relatedness by establishing feelings of mutual trust and shared values as well as enhancing feelings of competence and benevolence through positive performance feedback. Consistent with this expectation, performance-related pay has been found to be associated with higher job satisfaction among employees with higher PSM (Stazyk Citation2013). Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a: Employee perceptions of reward equity are positively related to public managers’ work engagement.

Hypothesis 2b: The relationship between PSM and employee engagement will be moderated by reward equity such that PSM will have a stronger influence on engagement when perceived reward equity is high than when perceived reward equity is low.

As noted above, employee perceptions of both prosocial impact and reward equity may influence employee engagement by enhancing their sense of meaningfulness at work. This raises questions regarding how they may work together or even compete in their influence on employee engagement. Their effects could be additive so that each can contribute and provide additional improvements to employee feelings of meaningfulness and efficacy.

Alternatively, there may be limits on either the levels of meaningfulness that can be experienced or on the ability of meaningfulness to increase employee engagement. Although either could occur, there are reasons to think that the influence of these mechanisms might be limited or even differ in their relative strength or influence due to differences in the source and importance of the information each provides. Job prosocial impact, for example, may influence the link between employee values and accomplishments more directly as perceptions of prosocial impact are often derived from the employee’s firsthand experience and assessments of how their work benefits the community or individuals they serve. In contrast, rewards and recognitions may provide more indirect and less powerful evidence of meaningful accomplishment as it relies on the organization’s ability to use rewards to convincingly communicate both their recognition of an employee’s accomplishments as well as their importance to individuals and community the employee is trying to serve.

That job prosocial impact may be more effective than rewards in convincing the employee that their PSM is being satisfied through work is consistent with expectations that extrinsic rewards are less effective in motivating public employees with high PSM (Perry and Wise Citation1990). When individuals with higher PSM also feel that their work has considerable prosocial impact and importance, their PSM may be more strongly activated and their jobs may seem so fulfiling that extrinsic rewards may not be as motivating or important. Conversely, performance-based rewards and recognition provided by the organization may be most effective in increasing employee engagement when employees with high PSM have difficulty seeing the prosocial impact of their work. Existing research provides some evidence in support of how the power/strength of the effects might differ. Several studies, for example, have found that increasing opportunities for employees to directly observe the importance of their work on beneficiaries produces higher performance and stronger feelings of person-organization fit than relying on leaders to articulate a compelling vision that emphasizes the importance of the work and values shared by the employee and organization (Bellé Citation2014; Jensen Citation2018). Hence, the last hypothesis we test in this study is as follows.

Hypothesis 3: The moderating effect of perceived reward equity on the relationship between PSM and employee engagement (Hypothesis 2b) will be stronger when perceived prosocial impact is low than when perceived job prosocial impact is high.

Data and methods

Sample and procedures

We tested the three hypotheses using survey data collected from 56 principals of vocational training institutes (VTIs) of the Punjab Vocational Training Council (PVTC). PVTC was established by the Government of the province of Punjab in the late 1980s. The mission of PVTC is to provide vocational training and employment opportunities to at-risk youth. The organization consists of 129 VTIs across the province, catering to 89,000 students annually. Most training programs last between 6 months to a year and are designed according to the needs of local businesses. The training programs are free, and the students also receive a small monthly stipend while enrolled. The VTIs are grouped into 10 geographical clusters in three regions, each of which is headed by an area manager. Each VTI is headed by a principal who oversees all operational matters of the training institute. The principal is also responsible for the identification and career counselling of at-risk youth in the community and helping graduates find employment.

Thirty principals from each of the three regions were selected and invited to participate in the study. The principals were informed that their participation in the study is entirely voluntary and data collected will remain confidential and not be shared with anyone in their organization. To facilitate the timely completion of the questionnaires, the principals were given both email and text message reminders. The principals were allowed to complete the bi-weekly questionnaires over the phone if they were travelling or had any computer-related problems.

All surveys were written in English because English is an official language in Pakistan. The first questionnaire was distributed in March of 2018 using Qualtrics. The purpose of the first survey was to gather data on principals’ PSM and perceived reward equity. We included these measures in the first survey assuming PSM and perceptions of extrinsic reward equity may not change much over a few months. The survey remained open for two weeks. We sent individual reminders to boost the survey response rate. A total of 61 principals agreed to participate in the study and completed the first survey for a response rate of 73.50%.

The principals’ ages ranged from 28 to 54 years with a mean of 38.5 years. Their tenures in PVTC ranged from 2 to 19 years with an average tenure of 10.78 years. All principals reported having a four-year college degree. The vast majority of the principals who completed the baseline questionnaire were male (90%). However, this is not surprising; participation of women in the labour force in Pakistan in 2018 was 25% and the representation of women in senior managerial positions is likely to be much lower. The gender distribution of the principals in our sample is similar to the gender distribution of all principals in PVTC (91% male).

The principals who agreed to participate in the study were asked to complete the background survey and six additional bi-weekly surveys. The bi-weekly surveys included questions about their work engagement, workload, procedural constraints, job prosocial impact, and supervisor support. The bi-weekly questionnaires were distributed on Wednesdays every other week and principals were asked to complete the questionnaire by Friday of that week. This was done to reduce any potential recall bias in the responses. Individual reminders (email and text messages) were sent to the principals to boost the surveys’ response rates. A total of 251 of the 366 bi-weekly questionnaires were completed for an overall response rate of 68.6%.

Measures

Because each principal was requested to complete a total of seven surveys, we used abbreviated scales to shorten the time it required them to complete the surveys. We measured perceived reward equity with two items in the first survey. The items were taken from Steer’s Task-Goal Attribute Scales (Citation1976). The items are ‘Pay and promotion in PVTC depend on how well employees perform their job’, and ‘Differences in employee performance in my organization are recognized in a meaningful way’. The items were measured on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha of the measure was .83.

We measured PSM with five items in the first survey. The items are: ‘Meaningful public service is very important to me’, ‘I am not afraid to stand up for the rights of others even if it means I will be ridiculed’, ‘Making a difference in society means more to me than personal achievements’, ‘I am prepared to make enormous sacrifices for the good of society’, ‘I am reminded by daily events about how dependent we are on one another’. The items come from the Merit System Protection Board Survey (Wright, Christensen, and Pandey Citation2013) and were measured on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha of the PSM measure was .57, which is lower than the typical threshold of .70. Upon examining item-level responses, we found that responses to the first item were negatively skewed (M = 4.85) and had limited variability (SD = .42). Furthermore, confirmatory factor analysis showed poor factor loading on the first item (λ = −.01) as well as the fifth item (λ = .29). The factor loadings on the remaining three items were high. The lack of variation in the responses of the first item might be due to social desirability bias (unlike the 3 remaining items, it does not ask about the importance of public service relative to its costs), while the other low factor loading might be because the wording of the item and its connection to public service may not transfer well to a non-western cultural context.Footnote1 We dropped these two items from our analysis to create a three-item PSM measure that focuses on the self-sacrifice dimension of the construct. Cronbach’s alpha of this abbreviated measure was .68.

We measured work engagement with five items in the bi-weekly surveys. The items were taken from the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (Schaufeli, Bakker, and Salanova Citation2006). The five items are ‘I felt bursting with energy at work’, ‘I was enthusiastic about my job’, ‘I felt happy when I was working intensely’, ‘I felt proud of the work that I did’, and ‘I was immersed in my work activities’. The items were measured on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha of the work engagement measure was .69.

We measured job prosocial impact with three items in the bi-weekly surveys. The items were taken from Grant’s perceived prosocial impact scale (Citation2012). The items are ‘I was fully conscious about the positive impact that my work had on others’, ‘I was fully aware of how my work benefited others’, and ‘I felt that my work made a positive difference in other people’s lives.’ The items were measured on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha of the measure was .78.

In our analysis, we include several control variables that may be related to our predictor measure, PSM, and outcome measure, work engagement. We control for supervisor support because it is an important predictor of work engagement and it may be related to changes in principals’ work resources and work demands (Ancarani et al. Citation2021; Demerouti and Bakker Citation2006). The variable was measured with six items in the bi-weekly surveys. The items were taken from the Managerial Practices Survey (Yukl, Gordon, and Taber Citation2002) and measured on a five-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = to a very great extent). The items are ‘Showed concerns for your needs and feelings’, ‘Provided you support and encouragement during a stressful task’, ‘Expressed confidence in your ability to accomplish a challenging task’, ‘Provided instruction about how to improve your job performance’, ‘Demonstrated you how to effectively accomplish your job tasks’, and ‘Arranged to get help or resources you needed to do your work effectively’. Cronbach’s alpha of this measure was .94.

We also control for manager workload because it is a predictor of work engagement (Bakker and Demerouti Citation2007) and may also be related to manager PSM. We measured workload with three items in the bi-weekly surveys. The items were adapted from Karasek’s Job Content Scale (Citation1985). The items are ‘I felt I needed more time to get everything done’, ‘I felt I could never seem to catch up’, and ‘I needed to do things hastily in order to get everything done’. The items were measured on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). The Cronbach’s alpha of the measure was .70.

Moreover, we control for procedural constraints because excessive burdensome rules and administrative procedures may diminish the influence of PSM on public employee engagement (Borst, Kruyen, and Lako Citation2019; Moynihan and Pandey Citation2007). Procedural constraints is measured with a single item, ‘Rules and administrative details made it difficult for me to get the work done’, in the bi-weekly survey. The item was adapted from the organizational constraints subscale of the situational strength scale (Meyer et al. Citation2014). The item was measured on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

We included several additional control variables in our analyses. We include principal gender (Female = 1, Male = 0), and organization tenure (in years) because these individual characteristics may be related to both PSM and work engagement (Parola et al. Citation2019). Data for principal gender and organization tenure were collected in the first survey. We included dummy variables for regions to control any regional variations in the survey responses.

Results

Preliminary analysis

Because of the nested structure of our data, we conducted a multi-level confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the construct validity of our measures. Because we measured procedural constraints with a single survey item, we excluded the measure from the CFA. As indicated in the Supplementary/Appendix , all scale items have statistically significant factor loadings (p < .01) for their respective latent constructs. The level 1 average variances extracted (AVEs) for PSM and reward equity are .75 and .89 respectively, while the level 2 AVEs of the prosocial impact and work engagement are .75 and .66 respectively. The fit indices obtained from the multi-level CFA are: χ2 (307) = 446.93, CFI = .99, TLI = .98 and RMSEA = .04. Overall, these CFA results suggest that the study measures have adequate construct validity.

shows the means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients of all study measures. The average managers in our sample report relatively high levels of PSM (M = 4.31/5, SD = .61) and job prosocial impact (M = 6.03/7, SD = .74), which suggest that even scores below one standard deviation below the mean for the two measures indicate moderate levels of PSM (3.7/5) and job prosocial impact (5.29/7). Looking at the correlations reported in , we see work engagement is associated positively to PSM (r = .385, p < .05), perceived reward equity (r = .345, p < .05), and supervisor support (r = .215, p < .05) and negatively to workload (r = −.182, p < .05). Job prosocial impact has the strongest positive association with work engagement (r = .502, p < .05). Among the predictor measures, we do not observe any unusually high bi-variate correlation. Perceived reward equity has a moderate positive relationship with PSM and supervisor support (r = .348, for both relationships, p < .05). Workload has a strong positive association with procedural constraints (r = .628, p < .05) and a moderate negative association with supervisor support (r = −.313, p < .05) and perceived prosocial impact (r = −.229, p < .05).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations (SD), and correlation coefficients.

Hierarchical linear modelling

We conducted Hierarchical Linear Modelling (HLM), also known as multi-level modelling, to test our hypotheses (Raudenbush and Bryk Citation2004). Before estimating the HLM models, we grand mean-centred values of the four Level 2 variables (i.e. PSM, reward equity, and tenure). We person mean-centred scores of the three Level 1 variables (i.e. prosocial impact, workload, procedural constraints, and supervisor support). Hence, the Level 1 regression coefficients represent only within-person effects without possible confounding of between-person influences, ensuring that the cross-level moderation effects reflect the impact of between-subject differences on the within-subject associations.

The HLM results are shown in . Following Raudenbush and Bryk (Citation2004), first, we estimated the empty/null model to determine whether HLM is the appropriate empirical approach for our analysis. Looking at the results shown in column 1 (i.e. the null model) in , we find that the intercept and two variance components of the model are statistically significant (p < .01). The estimates of variance components in the model suggest that 64.3% of the total variance in work engagement is within principals and 35.7% of the total variance is between principals. The relatively high intra-class correlation coefficient of .643 suggests that HLM is indeed the appropriate analytic approach for testing the hypotheses in our study.

Table 2. HLM results.

The second column in shows the effects of only the controls, while the third column shows the main effects of all level 1 and level 2 variables. The fourth column shows estimates of a model with all level 1 and level 2 variables plus two two-way interaction effects (PSM x Prosocial Impact, PSM x Reward Equity) to test Hypotheses 1b and 2b. In column 5, we report the HLM estimates of our final model that included all level 1 and level 2 variables, the two interaction terms included in model 4, and the three-way interaction effect (PSM x Reward Equity x Prosocial Impact) suggested by Hypothesis 3.

Looking at the results shown in model/column 5, we find a positive linear association between PSM and work engagement (γ = .237, p < .05), providing support to Hypothesis 1a. The estimate suggests that principals who have a very high level of PSM (one standard deviation above the mean), report, on average, a .24 point higher in their work engagement score than principals with a moderate (one standard deviation below the mean) level of PSM. We do not find support for Hypothesis 1b which suggested that the connection between PSM and work engagement would be moderated by the perception of job prosocial impact. While we observe a strong positive relationship between job prosocial impact and work engagement (γ = .419, p < .05), the interaction term for PSM and prosocial impact is not statistically significant.

We also do not find empirical support for Hypothesis 2a and 2b. The results show that perceived reward equity is positively related to managers’ work engagement (γ = .178), but this effect is not statistically significant (p > .05). The two-way interaction term for PSM and job reward equity is also not statistically significant (p > .05).

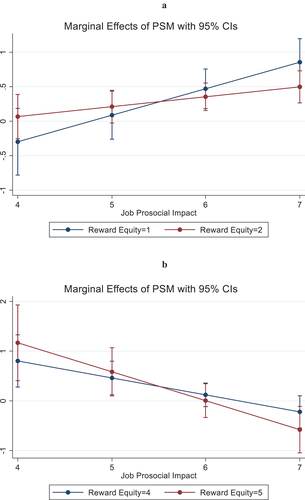

However, we find a statistically significant three-way interaction effect among PSM and perceived reward equity and job prosocial impact in predicting work engagement (γ = −.231, p < .05), as suggested in Hypothesis 3. To gain a better understanding of the complex three-way interaction effect, we conducted some additional analyses. First, we estimated the marginal effects of PSM on principals’ work engagement at different levels (Mean ± 1 SD) of perceived reward equity and job prosocial impact. The results of this analysis are shown in .

Table 3. The marginal effects of PSM on work engagement at low and high levels of perceived reward equity and prosocial impact.

Looking at the estimates shown in row 1 of , we find a positive connection between PSM and principals’ work engagement when reward equity and job prosocial impact scores are below 1 SD from the mean, but this effect is not statistically significant (p > .05). However, the estimates in rows 2 and 3 show a significant (p < .05) positive relationship between PSM and work engagement when reward equity scores at 1 SD below the mean and job prosocial impact scores are 1 SD above the mean and when reward equity scores are 1 SD above the mean and job prosocial impact scores 1 SD below the mean. Finally, the marginal effect of PSM (see estimates in row 4 in ) on work engagement is not statistically significant (p > .05) when both reward equity and job prosocial impact scores are both above 1 SD from the mean.

For a more nuanced understanding of the moderating effects of PSM on work engagement, we plotted the marginal effects of PSM when reward equity scores are low (i.e. 2/5) to very low (i.e. 1/5) and high (i.e. 4/5) to very high (5/5). The estimated effects are shown in . Looking at the upper right side of ), we see that PSM has a strong positive influence on employee work engagement when job prosocial impact is moderately high to very high and reward equity is very low. PSM has a strong positive influence on principals’ work engagement, as shown at the upper left side of ) when perceived reward equity is moderately high to very high and prosocial impact is low to moderate. Moreover, looking at the lower right side of ), we find that, at a very high level of reward equity and job prosocial impact, PSM has a significant negative impact on work engagement, although these conditions are very uncommon as they represent only six percent of our study sample.

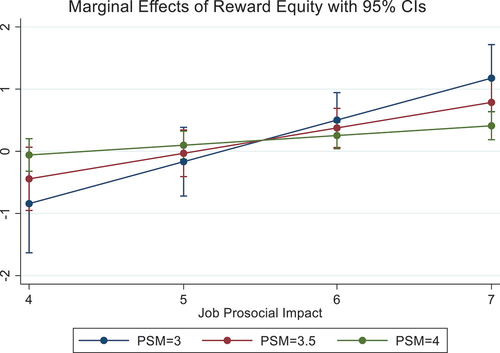

To understand situations where reward equity and job prosocial impact may work together (and not PSM) to influence principals’ work engagement, we created another interaction plot that shows the marginal effects of reward equity at low to moderate levels of PSM (i.e. PSM scores are at 3, 3.5, and 4 on a scale of 5) and at low to a high level of job prosocial impact. As shown in the upper right side of , for principals with low to moderate levels of PSM, perceived reward equity has a significant positive effect on work engagement when job prosocial impact is moderately high to very high. This suggests that these managers are likely to be more engaged when job prosocial impact and reward equity are high. Finally, the lower left side of shows that reward equity has a negative impact on work engagement when both PSM and job prosocial impact scores are very low, but such cases are pretty uncommon in our sample.

Discussion

Our study advances the understanding of public sector employee engagement in several key ways by drawing on and connecting three separate existing literatures investigating the important roles that PSM, job prosocial impact, and reward equity can play in influencing employee engagement. While all three factors have been found to be associated with higher levels of engagement and work through similar mechanisms that strengthen the employee-organization relationship and the employee’s sense of meaningful accomplishment, this is the first study to investigate how they may work together to enhance employee engagement.

In doing so, our findings support past studies that have found that both employee PSM (Bakker Citation2015; Borst Citation2018; Borst, Kruyen, and Lako Citation2019; De Simone et al. Citation2016; Levitats and Vigoda-Gadot Citation2019; Ugaddan and Park Citation2017) and their perceptions of their work’s prosocial impact (Freeney and Fellenz Citation2013; see also Boardman and Sundquist Citation2009; Jensen Citation2018; Vogel & Willems 2020) have important and yet independent positive relationships with employee engagement. These findings add confidence to the claims made by previous research by showing that employee PSM measured at the beginning of the study can predict levels of employee work engagement reported many weeks later, even after controlling for reward equity and important variation in employee perceptions of job resources (prosocial impact and supervisor support) and job demands (workload and procedural constraints) an employee experiences over time. Similarly, these findings also strengthen the evidence in support of claims that prosocial impact can facilitate greater levels of work engagement regardless of their PSM levels as we find support for this relationship even after controlling for the effects of PSM (Freeney and Fellenz Citation2013). That we find distinct and direct relationships for both employee PSM and their perceptions of prosocial impact of their work with work engagement is consistent with expectations that they operate through separate albeit related mechanisms (Boardman and Sundquist Citation2009). While PSM captures the general importance and the desire an employee places on public service that can direct and initiate work engagement when employees see their work as having a positive impact it signifies the behaviour-outcome contingency that also helps initiates and sustains motivation (Grant Citation2008).

Our study failed to confirm previous evidence of a simple direct relationship between reward equity (Ghosh, Rai, and Sinha Citation2014; Kumasey, Delle, and Hossain Citation2021; Smets et al. Citation2004; Strom, Sears, and Kelly Citation2014) and public employee engagement after controlling for employee PSM and perceptions of prosocial impact. This suggests that its role in increasing employee engagement may be more limited than previously expected and we do find evidence that reward equity can be more influential under the right conditions. Nonetheless, both the relatively low levels of reward equity reported in our sample as well as the failure to find a direct relationship with employee engagement are consistent with past arguments that public sector organizations face considerable financial and procedural constraints on their ability to provide performance-related rewards (Boyne, Poole, and Jenkins Citation1999; Perry, Engbers, and Jun Citation2009) and public employees may be more likely to find the act of providing public service inherently rewarding (Perry and Wise Citation1990).Footnote2

Our study also advances our understanding of public employee engagement in new ways by illustrating how PSM, job prosocial impact, and reward equity may work together to enhance engagement. Our first contribution concerns the role job reward equity and prosocial impact can play in enhancing PSM’s power to engage employees. Building on arguments previously made in the literature, we suggest that perceptions of both job prosocial impact and reward equity can provide employees with important feedback about person-organization fit as well as whether they can successfully perform their work and when they do, whether their work is meaningful. Although our findings suggest that both can strengthen the relationship between PSM and employee engagement in similar ways but this relationship seems strongest when only one is present. PSM, for example, is found to have the strongest influence on work engagement when employee perception of job prosocial impact is high and reward equity is low (conditions that represent nearly 40% of our study sample). For employees with strong PSM, job prosocial impact signals that their work efforts can and do provide an opportunity to satisfy their specific desire to perform meaningful public service. Consistent with this expectation, our findings reinforce the evidence that PSM’s effects on employee performance and related outcomes are moderated by employees’ ability to experience and understand the prosocial impact of their work (Bellé Citation2013, Citation2014; van Loon et al. Citation2018). When employees with higher PSM also feel that their work has considerable prosocial impact, their PSM may be more strongly activated and their jobs may seem so fulfiling that the awareness of their work’s prosocial impact can buffer the negative reactions that are often associated with extrinsic reward inequities.

We also find that employee perceptions of reward equity can strengthen the relationship between PSM and employee engagement but only when employees experience moderate to low levels of prosocial impact (conditions that only represent just over 5% of our study sample). Just as job prosocial impact may help mitigate the negative effects of low reward equity in employees with higher PSM, reward equity may also help when strong evidence of prosocial impact is not available. When employees with high PSM have difficulty seeing sufficiently high levels of prosocial impact of their work, the performance-based rewards and recognition provided by the organization may be especially effective in increasing employee engagement by signalling the importance and success of their work efforts. This not only strengthens the behaviour-outcome contingency that initiates and sustains motivation but also strengthens feelings of person-organization fit by signalling that the organization shares their public service values.

The second contribution of our study concerns identifying when it is reward equity and prosocial impact (and not PSM) that may drive employee engagement. In fact, our findings suggest that nearly half of our sample work under conditions where PSM is unrelated to employee engagement. PSM, for example, is not associated with increases in engagement when employees experience moderate to high levels of both prosocial impact and reward equity (conditions that represent just over one-third of our study sample). This may be because job prosocial impact and reward equity play such a powerful role in helping to elicit the expected critical psychology states like meaningfulness (Hackman and Oldham Citation1980; Grant Citation2007) or satisfy fundamental human needs like competence and relatedness (Breaugh, Ritz, and Alfes Citation2018; Gagne and Deci 2005; Grant Citation2007) that employees with lower PSM report being just as engaged in their work as employees with higher PSM. Consistent with this explanation, our findings indicate that employees with low to moderate levels of PSM (represent nearly one-third of our sample) are more likely to be engaged when both reward equity and prosocial impact are high. Conversely, we also found that PSM was not associated with increased employee engagement when prosocial impact and reward equity are both low (conditions that represent about 10% of our study sample). Perhaps such impoverished conditions do so little to activate critical psychological states, satisfy their basic needs, or their desire to serve the public that employees find it difficult to engage in or be inspired by their work. These findings and their interpretations are also consistent with previous research that suggests PSM may not be very important to employee job satisfaction after controlling the other types of motivation expected to satisfy essential human needs (Breaugh, Ritz, and Alfes Citation2018). These findings may help explain the inconsistent empirical support for PSM’s relationship with outcomes associated with employee engagement (Awan, Bel, and Esteve Citation2020; Ritz, Brewer, and Neumann Citation2016).

Finally, our analysis suggests that under relatively uncommon and extreme conditions where principals experience maximum levels of job prosocial impact and reward equity (conditions that represent about 6% of our study sample), higher levels of PSM are associated with a slight but statistically significant decline in work engagement. More research is needed to understand the mechanisms behind this unexpected finding. However, one potential explanation of this finding is that such public managers might feel less engaged in their work when job prosocial impact and performance reward equity are so high because higher PSM does not satisfy their need/willingness to self-sacrifice when providing service to others. That without greater self-sacrifice (not present with high performance reward equity) they may feel that there are other jobs/services/clients that need people like them more.

Although findings of our study contribute to research in public management by providing insights into when and how PSM influences employee engagement, the contributions of our study should be considered in light of its limitations. We examined the relationship between PSM and public employee engagement with repeated measures of work engagement. While the use of panel data allowed us to conduct a robust test of this relationship, we cannot infer a causal link between PSM and employee engagement. Additionally, to reduce the time it required managers to complete the surveys, we used abbreviated scales for several measures including PSM. Our PSM items capture primarily the self-sacrifice dimension of PSM. The other three dimensions – compassion, commitment to the public interest, and attraction to policy-making – are also likely to be related to public employee work engagement even though they were not examined in our study.

We examined the relationship between PSM and employee engagement using repeated measures of engagement. The use of a panel design allowed us to conduct a robust test of this relationship. But we cannot infer any causal relationship between PSM and employee engagement. Finally, the use of a small and arguably a unique sample limits our ability to generalize the findings to a broader population of public sector employees in Pakistan and other countries. Until recently, the bulk of PSM research has been conducted in Western countries (Van der Wal Citation2015). While the results of these studies appear to be partially (Kim Citation2009) or largely (Miao et al. Citation2018) consistent in East Asian cultural contexts, more work needs to be done to fully understand how PSM influences public employees’ work attitudes and behaviours in other cultural contexts. The contextual variation in PSM is often attributed to the differences along the dimensions of National Cultures as identified by Hofstede (Citation1980). Studies in Muslim majority countries show a relationship between PSM and religious identity and values (Hassan and Ahmad, Citation2021). Such a connection is bound to be relevant in a country like Pakistan that has a 97% Muslim population. Future studies should replicate and verify our results in other Muslim majority countries, especially in South and Southeast Asia, and with larger samples of public employees. Such studies can also help to understand whether religious identity moderates the effects of PSM on public employee work attitudes and behaviours.

Conclusion and implications for practice

Although additional research is needed to verify these findings in different samples and settings, this study has several potentially important implications for practitioners and scholars. Drawing on and connecting three separate existing studies investigating the important roles that PSM, prosocial impact and reward equity can play in influencing employee engagement, our findings suggest that supervisors may need to use different strategies to engage their employees depending on their levels of PSM and the potential to experience reward equity and prosocial impact in their jobs. When employees have high PSM and the potential to provide performance contingent rewards or recognition is low, it is important to take steps to maximize their ability to see the prosocial impact of their jobs. Perhaps by increasing beneficial contact and highlighting the importance of the employee’s work. When employees with high PSM work in jobs with very little direct contact with beneficiaries and the ability to clearly see meaningful service outcomes is difficult, creating a work environment where employees feel appropriately recognized if not rewarded for their accomplishments can help employee engagement by enhancing their task feelings of competence, task significance, and person-organization fit. For a potentially large percentage of their workforce employees with moderate to low levels of PSM, however, supervisors may find that enhancing employee feelings of both job prosocial impact and reward equity may be the most effective strategy to enhance employee work engagement.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.4 KB)Supplemental Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.2013069

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. A similar pattern was found in a recent study of Brazilian civil servants (Tavares, Lima, and Michener Citationforthcoming).

2. Another potential explanation for the differences between our findings and those of previous studies may be due to measurement differences. Our study’s measure of reward equity differed from many past studies in that it did not include employee perceptions of the equitable distribution of workload and responsibility equity that may strengthen its relationship with employee engagement (Ghosh, Rai, and Sinha Citation2014; Kumasey, Delle, and Hossain Citation2021; Strom, Sears, and Kelly Citation2014).

References

- Adams, J. S. 1963. “Towards an Understanding of Inequity.” The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 67 (5): 422. doi:10.1037/h0040968.

- Akingbola, K., and H. A. van Den Berg. 2019. “Antecedents, Consequences, and Context of Employee Engagement in Nonprofit Organizations.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 39 (1): 46–74. doi:10.1177/0734371X16684910.

- Ancarani, A., F. Arcidiacono, C. Di Mauro, and M.D. Giammanco. 2021. “Promoting Work Engagement in Public Administrations: The Role of Middle Managers’ Leadership.” Public Management Review 23 (8): 1234–1263. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1763072.

- Asseburg, J., J. Hattke, D. Hensel, F. Homberg, and R. Vogel. 2020. “The Tacit Dimension of Public Sector Attraction in Multi-incentive Settings.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 30 (1): 41–59. doi:10.1093/jopart/muz004.

- Awan, S., G. Bel, and M. Esteve. 2020. “The Benefits of PSM: An Oasis or a Mirage?” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 30 (4): 619–635. doi:10.1093/jopart/muaa016.

- Bakker, A. B., W. B. Schaufeli, H. J. Sixma, W. Bosveld, and D. Van Dierendonck. 2000. “Patient Demands, Lack of Reciprocity, and Burnout: A Five‐year Longitudinal Study among General Practitioners.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 21 (4): 425–441.

- Bakker, A. B. 2015. “A Job Demands–resources Approach to Public Service Motivation.” Public Administration Review 75 (5): 723–732. doi:10.1111/puar.12388.

- Bakker, A.B., and E. Demerouti. 2007. “The Job Demands‐resources Model: State of the Art.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 22 (3): 309–328. doi:10.1108/02683940710733115.

- Bashir, M., and S. Hassan. 2020. “The Need for Ethical Leadership in Combating Corruption.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 86 (4): 673–690. doi:10.1177/0020852318825386.

- Bellé, N. 2013. “Experimental Evidence on the Relationship between Public Service Motivation and Job Performance.” Public Administration Review 73 (1): 143–153. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02621.x.

- Bellé, N. 2014. “Leading to Make A Difference: A Field Experiment on the Performance Effects of Transformational Leadership, Perceived Social Impact, and Public Service Motivation.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 24 (1): 109–136. doi:10.1093/jopart/mut033.

- Bellé, N. 2015. “Performance‐related Pay and the Crowding Out of Motivation in the Public Sector: A Randomized Field Experiment.” Public Administration Review 75 (2): 230–241. doi:10.1111/puar.12313.

- Boardman, C., and E. Sundquist. 2009. “Toward Understanding Work Motivation: Worker Attitudes and the Perception of Effective Public Service.” The American Review of Public Administration 39 (5): 519–535. doi:10.1177/0275074008324567.

- Borst, R. T., P. M. Kruyen, and C. J. Lako. 2019. “Exploring the Job Demands–resources Model of Work Engagement in Government: Bringing in a Psychological Perspective.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 39 (3): 372–397. doi:10.1177/0734371X17729870.

- Borst, R. T., P. M. Kruyen, C. J. Lako, and M. S. de Vries. 2020. “The Attitudinal, Behavioral, and Performance Outcomes of Work Engagement: A Comparative Meta-analysis across the Public, Semipublic, and Private Sector.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 40 (4): 613–640. doi:10.1177/0734371X19840399.

- Borst, R. T. 2018. “Comparing Work Engagement in People-changing and People-processing Service Providers: A Mediation Model with Red Tape, Autonomy, Dimensions of PSM, and Performance.” Public Personnel Management 47 (3): 287–313. doi:10.1177/0091026018770225.

- Boyne, G., M. Poole, and G. Jenkins. 1999. “Human Resource Management in the Public and Private Sectors: An Empirical Comparison.” Public Administration 77 (2): 407–420. doi:10.1111/1467-9299.00160.

- Breaugh, J., A. Ritz, and K. Alfes. 2018. “Work Motivation and Public Service Motivation: Disentangling Varieties of Motivation and Job Satisfaction.” Public Management Review 20 (10): 1423–1443. doi:10.1080/14719037.2017.1400580.

- Bright, L. 2007. “Does Person-organization Fit Mediate the Relationship between Public Service Motivation and the Job Performance of Public Employees?” Review of Public Personnel Administration 27 (4): 361–379. doi:10.1177/0734371X07307149.

- Bro, L. L., L. B. Andersen, and A. Bøllingtoft. 2017. “Low-hanging Fruit: Leadership, Perceived Prosocial Impact, and Employee Motivation.” International Journal of Public Administration 40 (9): 717–729. doi:10.1080/01900692.2016.1187166.

- Buchanan B. 1975. Red-Tape and the Service Ethic: Some Unexpected Differences Between Public and Private Managers. Administration & Society, 6(4):423–444.

- Buunk, B. P., and W. B. Schaufeli. 1999. “Reciprocity in Interpersonal Relationships: An Evolutionary Perspective on Its Importance for Health and Well-being.” European Review of Social Psychology 10 (1): 259–291. doi:10.1080/14792779943000080.

- Christensen, R.K., and B.E. Wright. 2011. “The Effects of Public Service Motivation on Job Choice Decisions: Disentangling the Contributions of Person-organization Fit and Person-job Fit.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21 (4): 723–743. doi:10.1093/jopart/muq085.

- Christian, M. S., A. S. Garza, and J.E. Slaughter. 2011. “Work Engagement: A Quantitative Review and Test of Its Relations with Task and Contextual Performance.” Personnel Psychology 64 (1): 89–136. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x.

- Considine, M., P. Nguyen, and S. O’Sullivan. 2018. “New Public Management and the Rule of Economic Incentives: Australian Welfare-to-work from Job Market Signaling Perspective.” Public Management Review 20 (8): 1186–1204. doi:10.1080/14719037.2017.1346140.

- Corduneanu, R., A. Dudau, and G. Kominis. 2020. “Crowding-in or Crowding-out: The Contribution of Self-determination Theory to Public Service Motivation.” Public Management Review 22 (7): 1070–1089. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1740303.

- Cropanzano, R., and M. S. Mitchell. 2005. “Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review.” Journal of Management 31 (6): 874–900. doi:10.1177/0149206305279602.

- Dal Bó, E., F. Finan, and M. A. Rossi. 2013. “Strengthening State Capabilities: The Role of Financial Incentives in the Call to Public Service.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128 (3): 1169–1218. doi:10.1093/qje/qjt008.

- De Simone, S., G. Cicotto, R. Pinna, and L. Giustiniano. 2016. “Engaging Public Servants: Public Service Motivation, Work Engagement and Work-related Stress.” Management Decision 54 (7): 1569–1594. doi:10.1108/MD-02-2016-0072.

- Demerouti, E., and A. B. Bakker. 2006. “Employee Well-being and Job Performance: Where We Stand and Where We Should Go.” Occupational Health Psychology: European Perspectives on Research, Education and Practice 1: 83–111.

- Dias, J.J., and S. Maynard-Moody. 2007. “For-profit Welfare: Contracts, Conflicts, and the Performance Paradox.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 17 (2): 189–211. doi:10.1093/jopart/mul002.

- Freeney, Y., and M. R. Fellenz. 2013. “Work Engagement, Job Design and the Role of the Social Context at Work: Exploring Antecedents from a Relational Perspective.” Human Relations 66 (11): 1427–1445. doi:10.1177/0018726713478245.

- Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. 2005. Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362.

- Georgellis, Y., E. Iossa, and V. Tabvuma. 2011. “Crowding Out Intrinsic Motivation in the Public Sector.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 21 (3): 473–493. doi:10.1093/jopart/muq073.

- Ghosh, P., A. Rai, and A. Sinha. 2014. “Organizational Justice and Employee Engagement: Exploring the Linkage in Public Sector Banks in India.” Personnel Review 43 (4): 628–652. doi:10.1108/PR-08-2013-0148.

- Giauque, D., S. Anderfuhren-Biget, and F. Varone. 2013. “Stress Perception in Public Organisations: Expanding the Job Demands–job Resources Model by Including Public Service Motivation.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 33 (1): 58–83. doi:10.1177/0734371X12443264.

- Grant, A. M. 2007. “Relational Job Design and the Motivation to Make a Prosocial Difference.” Academy of Management Review 32 (2): 393–417. doi:10.5465/amr.2007.24351328.

- Grant, A. M. 2008. “Employees without a Cause: The Motivational Effects of Prosocial Impact in Public Service.” International Public Management Journal 11 (1): 48–66. doi:10.1080/10967490801887905.

- Grant, A. M. 2012. “Leading with Meaning: Beneficiary Contact, Prosocial Impact, and the Performance Effects of Transformational Leadership.” Academy of Management Journal 55 (2): 458–476. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.0588.

- Gruman, J. A., & Saks, A. M. 2011. Performance management and employee engagement. Human Resource Management Review, 21(2), 123–136.

- Hackman J.R. & Oldham G.R. 1980. Work Redesign.

- Hameduddin, T., and S. Fernandez. 2019. “Employee Engagement as Administrative Reform: Testing the Efficacy of OPM’s Employee Engagement Initiative.” Public Administration Review 79 (3): 355–369. doi:10.1111/puar.13033.

- Hameduddin, T., and S. Lee. 2021. “Employee Engagement among Public Employees: Examining the Role of Organizational Images.” Public Management Review 23 (3): 422–446. doi:10.1080/14719037.2019.1695879.

- Hassan, H. A., and A. B. Ahmad. 2021. The Relationship Between Islamic Work Ethic and Public Service Motivation . Administration & Society. doi:10.1177/0095399721998335.

- Hassan, S. 2013. “Does Fair Treatment in the Workplace Matter? An Assessment of Organizational Fairness and Employee Outcomes in Government.” The American Review of Public Administration 43 (5): 539–557. doi:10.1177/0275074012447979.

- Hassan, S. 2014. “Sources of Professional Employees’ Job Involvement: An Empirical Investigation in a Government Agency.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 34 (4): 356–378. doi:10.1177/0734371X12460555.

- Heinrich, C. J. 1999. “Do Government Bureaucrats Make Effective Use of Performance Management Information.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 9 (3): 363–394. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024415.

- Heinrich, C. J. 2002. “Outcomes–based Performance Management in the Public Sector: Implications for Government Accountability and Effectiveness.” Public Administration Review 62 (6): 712–725. doi:10.1111/1540-6210.00253.

- Herranz, Jr, J. 2008. “The Multisectoral Trilemma of Network Management.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1093/jopart/mum004.

- Hofstede, G. 1980. “Motivation, Leadership, and Organization: Do American Theories Apply Abroad?” Organizational Dynamics 9 (1): 42–63. doi:10.1016/0090-2616(80)90013-3.

- Hu, Q., W. B. Schaufeli, and T. W. Taris. 2013. “Does Equity Mediate the Effects of Job Demands and Job Resources on Work Outcomes?” Career Development International 18 (4): 357–376. doi:10.1108/CDI-12-2012-0126.

- Janssen, O. 2001. “Fairness Perceptions as a Moderator in the Curvilinear Relationships between Job Demands, and Job Performance and Job Satisfaction.” Academy of Management Journal 44 (5): 1039–1050.

- Jensen, U. T. 2018. “Does Perceived Societal Impact Moderate the Effect of Transformational Leadership on Value Congruence? Evidence from a Field Experiment.” Public Administration Review 78 (1): 48–57. doi:10.1111/puar.12852.

- Kahn, W. A. 1990. “Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work.” Academy of Management Journal 33 (4): 692–724.

- Karasek, R. A. 1985. Job Content Instrument: Questionnaire and User’s Guide. Lowell, MA.: University of Massachusetts Lowell, Department of Work Environment.

- Kim, S. 2009. “Testing the Structure of Public Service Motivation in Korea: A Research Note.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 19 (4): 839–851. doi:10.1093/jopart/mup019.

- Kjeldsen, A. M. 2014. “Dynamics of Public Service Motivation: Attraction‒selection and Socialization in the Production and Regulation of Social Services.” Public Administration Review 74 (1): 101–112. doi:10.1111/puar.12154.

- Kumasey, A. S., E. Delle, and F. Hossain. 2021. “Not All Justices are Equal: The Unique Effects of Organizational Justice on the Behaviour and Attitude of Government Workers in Ghana.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 87 (1): 78–96. doi:10.1177/0020852319829538.

- Kurland, N. B., and T. D. Egan. 1999. “Public V. Private Perceptions of Formalization, Outcomes, and Justice.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 9 (3): 437–458. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024417.

- Latham, G. P., L. Borgogni, and L. Petitta. 2008. “Goal Setting and Performance Management in the Public Sector.” International Public Management Journal 11 (4): 385–403. doi:10.1080/10967490802491087.

- Levitats, Z., and E. Vigoda-Gadot. 2019. “Emotionally Engaged Civil Servants: Toward a Multilevel Theory and Multisource Analysis in Public Administration.” Review of Public Personnel Administration. doi:10.1177/0734371X18820938.

- Luu, T.T. 2019. “Service-oriented High-performance Work Systems and Service-oriented Behaviors in Public Organizations: The Mediating Role of Work Engagement.” Public Management Review 21 (6): 789–816. doi:10.1080/14719037.2018.1526314.

- Maslach, C., W.B. Schaufeli, and M.P. Leiter. 2001. “Job Burnout.” Annual Review of Psychology 52 (1): 397–422. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397.

- Meyer, R. D., R. S. Dalal, I. J. Jose, R. Hermida, T. R. Chen, R. P. Vega, C. K. † Brooks, and V. P. Khare. 2014. “Measuring Job-related Situational Strength and Assessing Its Interactions with Personality and Voluntary Work Behavior.” Journal of Management 40 (4): 1010–1041. doi:10.1177/0149206311425613.

- Miao, Q., A. Newman, G. Schwarz, and B. Cooper. 2018. “How Leadership and Public Service Motivation Enhance Innovative Behavior.” Public Administration Review 78 (1): 71–81. doi:10.1111/puar.12839.

- Miner, J. B. 2005. Organizational Behavior: Essential Theories of Motivation and Leadership. New York: ME Sharpe.

- Moynihan, D.P., and S.K. Pandey. 2007. “The Role of Organizations in Fostering Public Service Motivation.” Public Administration Review 67 (1): 40–53. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00695.x.

- Ohana, M., and M. Meyer. 2016. “Distributive Justice and Affective Commitment in Nonprofit Organizations: Which Referent Matters?” Employee Relations 38 (6): 841–858. doi:10.1108/ER-10-2015-0197.

- Parola, H.O., M.B. Harari, D. E.L. Herst, and P. Prysmakova. 2019. “Demographic Determinants of Public Service Motivation: A Meta-analysis of PSM-age and -gender Relationships.” Public Management Review 21 (10): 1397–1419. doi:10.1080/14719037.2018.1550108.

- Peretz, H.V. 2020. “A View into Managers’ Subjective Experiences of Public Service Motivation and Work Engagement: A Qualitative Study.” Public Management Review 22 (7): 1090–1118. doi:10.1080/14719037.2020.1740304.

- Perry, J. L., and L. R. Wise. 1990. “The Motivational Bases of Public Service.” Public Administration Review 50 (3): 367–373. doi:10.2307/976618.

- Perry, J. L., T. A. Engbers, and S. Y. Jun. 2009. “Back to the Future? Performance-Related Pay, Empirical Research, and the Perils of Persistence.” Public Administration Review 69 (1): 39–51. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2008.01939_2.x.

- Perry, J. L., and W. Vandenabeele. 2015. “Public Service Motivation Research: Achievements, Challenges, and Future Directions.” Public Administration Review 75 (5): 692–699. doi:10.1111/puar.12430.

- Rainey, H. G. 1982. Reward Preferences among Public and Private Managers: In Search of the Service Ethic. The American Review of Public Administration, 16(4):288–302.

- Raudenbush, S.W., and A. S. Bryk. 2004. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. United Kingdom: Sage Publications, London.

- Ritz, A., G. A. Brewer, and O. Neumann. 2016. “Public Service Motivation: A Systematic Literature Review and Outlook.” Public Administration Review 76 (3): 414–426. doi:10.1111/puar.12505.

- Schaufeli, W. B., A. B. Bakker, and M. Salanova. 2006. “The Measurement of Work Engagement with a Short Questionnaire: A Cross–national Study.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 66 (4): 701–716. doi:10.1177/0013164405282471.

- Schaufeli, W. B., M. Salanova, V. González-Romá, and A. Bakker. 2002. “The Measurement of Engagement and Burnout: A Two Sample Confirmatory Factor Analytic Approach.” Journal of Happiness Studies 3 (1): 71–92. doi:10.1023/A:1015630930326.

- Schott, C., and A. Ritz. 2018. “The Dark Sides of Public Service Motivation: A Multi-level Theoretical Framework.” Perspectives on Public Management and Governance 1 (1): 29–42. doi:10.1093/ppmgov/gvx011.

- Smets, E. M., M. R. Visser, F. J. Oort, W. B. Schaufeli, and H. J. De Haes. 2004. “Perceived Inequity: Does It Explain Burnout among Medical Specialists.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 34 (9): 1900–1918. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02592.x.

- Stazyk, E. C. 2013. “Crowding Out Public Service Motivation? Comparing Theoretical Expectations with Empirical Findings on the Influence of Performance-Related Pay.” Review of Public Personnel Administration 33 (3): 252–274. doi:10.1177/0734371X12453053.

- Steers, R. M. 1976. “Factors Affecting Job Attitudes in a Goal-setting Environment.” Academy of Management Journal 19 (1): 6–16.

- Steijn, B. 2008. “Person-environment Fit and Public Service Motivation.” International Public Management Journal 11 (1): 13–27. doi:10.1080/10967490801887863.

- Strom, D. L., K. L. Sears, and K. M. Kelly. 2014. “Work Engagement: The Roles of Organizational Justice and Leadership Style in Predicting Engagement among Employees.” Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 21 (1): 71–82. doi:10.1177/1548051813485437.

- Taris, T. W., M. C. Peeters, P. M. Le Blanc, P. J. Schreurs, and W. B. Schaufeli. 2001. “From Inequity to Burnout: The Role of Job Stress.” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 6 (4): 303. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.6.4.303.

- Tavares, G. M., F. V. Lima, and G. Michener. forthcoming. “To Blow the Whistle in Brazil: The Impact of Gender and Public Service Motivation.” Regulation & Governance.

- Ugaddan, R. G., and S. M. Park. 2017. “Quality of Leadership and Public Service Motivation.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 30 (3): 270–285. doi:10.1108/IJPSM-08-2016-0133.