ABSTRACT

This paper provides fresh insights on how PIs (Polarity Items) in non-veridical contexts (questions and conditionals) are represented in the grammar of multilingual learners of Catalan at different stages of development. It explores how this non-native grammatical system interacts with other previously acquired systems of negation and the implicit and explicit evidence about the negative system as presented in textbooks. We test 89 Ln learners of Catalan (L1 English/Italian/Spanish/Portuguese) on the interpretation of PIs in non-veridical contexts. The findings reveal that initially, learners exhibit both facilitative and non-facilitative transfer from their prior languages (L1/L2), and that grammatical restructuring in L3/Ln development is influenced by learners’ language background, syntactic context, and proficiency in Catalan. The results indicate a tendency towards stagnation and reduced accuracy throughout the learning process, especially among learners whose L1 had a facilitative effect either during initial transfer or later stages of development. These observations are discussed in the context of theories of morphosyntactic transfer in L3/Ln acquisition, as well as L3 development. The paper also evidences that the presentation of PIs in textbooks can shape and restructure learners’ interpretation of these items and proposes acquisitionally and pedagogically informed criteria for the instruction of PIs to Catalan learners.

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, there has been a growing interest in understanding the nature of L3 representations (see Bardel & Sánchez, Citation2020, Rothman et al., Citation2019; Pinto & Alexandre, Citation2021; for recent overviews). Within L3 morphosyntax research, most have focused on modelling the source (e.g. Bardel & Falk, Citation2017; Fallah & Jabbari, Citation2018; Flynn et al., Citation2004; Rothman, Citation2015; Westergaard et al., Citation2017; Slabakova, Citation2017), and to a certain extent, the timing (González Alonso & Rothman, Citation2017), and nature of transfer selection (Schwartz & Sprouse, Citation2021a, Citation2021b). However, less attention has been given to going beyond the initial stages of L3 research, with only a few exceptions that explore L3 grammatical developmental patterns (e.g. Cabrelli et al., Citation2020; Cabrelli & Iverson, Citation2023; Puig-Mayenco et al., Citation2022; Stadt, Citation2019).

This study focuses on understanding the nature of Catalan polarity items (PIs) in the grammar of multilingual speakers of Romance languages and English across different levels of proficiency. It aims to contribute to L3 development theorising with relevant insights from a study combining an empirical investigation and an examination of Catalan Foreign Language (CFL) textbooks. We examine factors that have been previously addressed, and take a step further by considering the impact of instruction, in conjunction with other factors such as L1, L2, lexical items, and construction frequency, on the overall process of acquisition, similarly to what’s been done in L2 acquisition research (Gil et al., Citation2019; Marsden et al., Citation2018).

Furthermore, in response to Tomlinson’s (Citation2016: xiv) call for interaction between SLA research and materials development, we engage in a dialogue between our results and the analysis of CFL textbooks. Based on this dialogue, we propose key principles for designing an acquisitionally and pedagogically-informed teaching sequence on the negative system for Catalan L3/Ln learners. Ultimately, this study promotes a bidirectional, effective, and beneficial exchange between research and practice, paving the way for future practice-based research studies (Sato & Loewen, Citation2022).

2. Background

2.1. The negative system in Catalan and English, Italian, spanish and Portuguese involved in the study

Although the semantic concept of negation is expressed in all natural languages, the way it is expressed is not uniform. Languages can be divided into different types depending on: (i) the number of paradigms of polarity-sensitive items they have; (ii) the availability and characteristics of Negative Concord, and (iii) the non-negative contexts (i.e. non-veridical contexts) in which polarity-sensitive items can occur. Especially relevant for our aims are the paradigms of polarity-sensitive items of Catalan and the non-veridical contexts in which they can occur.

Catalan presents a set of indefinites and adverbs (e.g. ningú ‘no-one/nobody’, cap ‘none/any’, res ‘nothing/anything’, gens ‘at all’, mai ‘never/ever’, enlloc ‘nowhere/anywhere’) which display a hybrid behaviour regarding their polarsensitivity properties. One the one hand, they can occur isolated, as negative fragments answers (1), and they can appear in preverbal position in declarative negative sentences, where they can also license postverbal indefinites without the need for an overt negative marker (2).

(1) A: Qui ha anat a la plaça?

who have.aux.3sgo.part to art square

B: Ningú.

n-one

‘No-one.’

(2) Ningú (no) ha anat (mai) a la plaça.

n-one not have.aux.3S go.part ever to art square

‘No one has (ever) gone to the square.’

On the other hand, in post-verbal position, Catalan NCIs behave as ‘polarity sensitive items’ (Linebarger, Citation1987; Progovac, Citation1994; Giannakidou, Citation1998, Citation2000; Martins, Citation2000), as their grammatical use is determined by specific licensing conditions. Specifically, they need to appear under the scope of a non-veridical (Zwarts, Citation1995) operator that is responsible for ensuring their existential reading.Footnote2 Due to their sensitivity to non-veridicality (see Zwarts, Citation1995), the elements studied here can be licensed in interrogative sentences (3) and conditional clauses (4).

(3) Has vist res?

See.2nd.past n-thing?

‘Have you seen anything’

(4) Truca’m si la doctora diu res.

Call. imp.2.PS me. if the doctor say.3rd.PS. n-thing.

‘Call me if the doctor says anything’

Table 1. The cross-linguistic licensing of PIs in non-veridical contexts.

Regarding the formal account of both the NCI and PI properties of the set of negative elements in Catalan studied here, Espinal and Tubau (Citation2016) consider them polar items (with a scalar semantic feature). The use of such scalar polar items as NCIs in preverbal position and as fragment answers is explained by a last-resort negative feature [uNeg] which ensures their participation in negative concord relations in agreement with an [iNeg] semantic operator. Espinal et al. (Citation2021) and Espinal and Llop (Citation2022) argue that the double nature of such elements can be explained by the existence of two different homophonous sets of NCIs and PIs. Regardless of the specificities of the formal approach, when studying the acquisition of such items by speakers of Catalan Ln, it is crucial to determine whether: (i) learners’ grammars will include a representation of such items with a polarity feature – Tubau (Citation2008), Llop (Citation2020) – or a non-veridical feature (in terms of Gil & Marsden, Citation2013) which can be properly licensed in non-veridical contexts, or (ii) whether such items will be incorporated into learners’ grammars directly as NCIs, unable to appear in contexts other than anti-veridical environments.

In this study, we only focused on two of the non-veridical contexts (interrogatives and conditionals) because these are the only non-veridical contexts mentioned in the Curriculum for the teaching and learning of Catalan as a Foreign Language (Generalitat de Catalunya, Citation2022), restricted to the more advanced levels (C1 and C2). This limitation of the contexts presented to students during the whole path of the instruction on the negative system – albeit not representative of the complexity of the polarity system in Catalan –, is coherent with: (i) the saliency and frequency of interrogative and conditional contexts in daily life communication with respect to all the other contexts in ; and (ii), the fact that out of all the non-veridical context, these are also the most accepted by Catalan native speakers Catalan in grammatical judgement tests (see Llop, Citation2020).Footnote4

2.2. Instructed properties of the negative system and non-veridical contexts in Catalan Foreign Language textbooks

While the study of the influence of classroom instruction in the development of the Ln language was not the central aim of this research, an analysis of CFL textbooks was carried out to outline the blind spots of the teaching resources and to explore how the teaching pathway of negation in textbooks could be redesigned to overcome the challenges identified in the empirical research.Footnote5

The analysis of the textbooks showed that the presentation of the target elements is atomic, and lexical items are never seen as part of the same system (except for some of the grammar summaries at the end of the books). All the items are presented spread between the beginner levels (A1-A2) and the lower intermediate level (B1) – depending on the textbook. More importantly, after they have been presented for the first time, polar items are not thoroughly explored anymore (except for some sporadic mentions in Veus 3, B1, and a more detailed presentation of interrogative and conditional contexts in only one book, A punt 4, B2).

Interestingly, some of the textbooks corresponding to advanced levels (C1-C2) mention interrogative and conditional uses, but do not refer to any of the remaining non-veridical contexts. Cross-linguistic comparisons and chances to highlight the parallels or divergence of the nature of the set of items studied with respect to learners already-acquired languages are non-existent. The target elements are presented linked to the communicative needs of speakers in different contexts.Footnote6 Crucially, these items are pervasively presented in anti-veridical contexts (with the only exception of some examples found in indirect or incidental input). Specifically, the preferred structure for the first appearances of PIs in Catalan Foreign Language textbooks is thenegative concord configuration where the polar item occupies the postverbal position (i.e. No + V + PI). As a matter of fact, preverbal configurations in which the elements combine with a negative marker conveying a single negation reading (PI + no + V) are very rare across the instruction pathway. Overall, the analysis of textbooks depicts a scenario in which Catalan PIs are effectively presented (both in explicit and implicit input) as NPIs, only able to be licensed in anti-veridical contexts (see Espinal & Llop, Citation2022; who use the term NPI to refer to what other authors in the literature call strong NPIs).

Moreover, regarding the interaction with the linguistic phenomenon, learners are exclusively and repeatedly asked to complete fill-in the gap activities, and there are no activities to process data with input processing tasks, or to reflect upon the linguistic forms and the impact of linguistic choices on meaning.Footnote7

2.3. L3 development

Although our study was never designed to test theoretical proposals of L3 morphosyntax directly, the data from ab initio participants can certainly have some insights for models of transfer selection. And so, herein we present a succinct summary of these proposals (see González Alonso, Citation2023; Rothman et al., Citation2019; Westergaard et al., Citation2023 for a comprehensive overview). Broadly speaking, theoretical proposals on transfer selection can be grouped into two main blocks: those that default transfer selection to the L1 (e.g. Hermas, Citation2010; Hermas, Citation2014; Na Ranong & Leung, Citation2009) or L2 (Bardel & Falk, Citation2007; Bardel & Falk, Citation2012; Bardel & Falk, Citation2012; Bardel & Sánchez, Citation2020; Falk & Bardel, Citation2011) and those that do not set a default status to either of the languages, but instead propose a variety of factors. To date, the available literature suggests that transfer selection is, indeed, not defaulted to either the L1 or L2, as there is ample evidence showing cases in which the L1 is transferred and other in which the L2 is (Rothman et al., Citation2019). Within those approaches that do not set a default status, they differentiate amongst them because they propose different factors to delimit the selection. The Linguistic Proximity Model (Westergaard et al., Citation2017) and the Scalpel Model (Slabakova, Citation2017) both argue that transfer takes place on a property-by-property basis. The former establishes linguistic proximity at the property level to be the determining factor for selection, whereas the latter claims that L3 transfer selection is complex and dynamic, and suggests a variety of factors, such as construction frequency and language dominance. There are also approaches to argue there is full transfer in line with Full Transfer (Schwartz & Sprouse, Citation1996) in L2 acquisition. The Typological Primacy Model (Rothman, Citation2010, Citation2013, Rothman et al., Citation2019) claims that the determining factor for transfer selection is holistic structural similarity (see Rothman et al., Citation2019 for an elaboration of what determines such similarity). The Primary Language of Communication (Fallah & Jabbari, Citation2018) argues that learners rely on the most dominant language widely used in the immediate context to determine transfer selection.

Ultimately, irrespective of the factors that delimit transfer selection in L3 acquisition, one can make developmental predictions based on the starting point of the process. And so, we will keep the above theories in mind when discussing developmental trajectories. To date, there is only one hypothesis that directly attempts to explain L3 grammatical developmentFootnote8 in relation to overcoming initial non-faciliation: the Cumulative Input Threshold Hypothesis (CITH: Cabrelli & Iverson, Citation2023). Such hypothesis claims that the rate of over-coming non-facilitation in L3 grammatical development will be inversely related to the lifetime linguistic input received in the transferred language. The hypothesis is formulated based on evidence from Spanish-English bilinguals acquiring L3 Brazilian Portuguese in relation to Differential Object Marking and raising across dative experiencer (a property that is not commonly taught in the language classroom). Their results show that only those learners who acquired Spanish as an L2 manage to converge to the L3 grammar, indicating that overcoming Spanish transfer from an L2 needs less time (and consequently input) than doing so from an L1. Puig-Mayenco et al. (Citation2022) tested CITH in the context of Catalan-Spanish bilinguals acquiring L3 English. Their results also show that linguistic experience in the transferred language does modulate the rate at which non-facilitation is overcome in L3 acquisition. However, in this study it does not seem to be Age of Acquisition (i.e. L2), contra CITH, but language dominance that modulates the rate of development. The study shows that those who transfer their less dominant language, irrespective of it being the L1 or an early acquired L2, overcome it quicker than those who transferred their more dominant language.

3. Study design

3.1. Research questions

The aim of the current empirical study is to understand the nature of Catalan PIs in the grammar of multilingual speakers of Romance languages across different levels of proficiency. Ultimately, as our results speak directly to the instruction of the negative system in CFL, we also seek to suggest some pedagogical implications drawing upon the dialogue of the results of the empirical study and the analysis of Catalan Ln textbooks (as seen in Section 2.2).

The currentempirical study entertains the following research questions:

Do learners of Catalan manage to acquire non-veridical readings of PIs(in questions and conditions) and if so, are there any defined developmental patterns for the two contexts under investigation?

Are the developmental patterns modulated by intralinguistic factors (L1, lexical items)?

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Background measures

Participants first responded to two tasks tapping into background information. There was a background questionnaire where participants were asked to indicate their L1 and other languages they spoke and/or studied, as well as their exposure to Catalan and the university where they were taking their course. There was also a self-designed proficiency task that involved 18 multiple-choice questions to assess learners’ morphosyntactic and lexical competence. Each item had three possible answers with an ‘I’m not sure’ response in case participants did not want to commit to an answer. Questions were ordered according to the different proficiency levels, that is, from A1 to C2 levels, and contained three items per designated level.Footnote9 Participants had 20 s to answer each question. The proficiency score served two purposes: determine learners who were beginner (A1) learners, and classify those who were not into two further groups (Beginner A2 and Intermediate B1/B2).

3.2.2. Main task

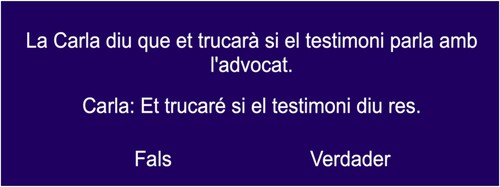

The main task consisted of a truth-value judgement task (of a duration of approximately 20 minutes) in which participants read a context and were given a sentence which they had to assess as true or false according to the context (see below); participants were also given the option to indicate they were not sure. The experiment consisted of three conditions with 16 items in each: 32 items to test the non-veridical condition and 16 items for the anti-veridical condition. We also included 24 fillers and 24 distractors that were used to control for attention and accuracy.Footnote10 Only those participants that had 80% accuracy in the distractors were included in the final analysis. Regarding the non-veridical condition, the 32 items were divided into the two sub-conditions under study: PIs in interrogative and conditional structures targeting existential readings (see below). With respect to the anti-veridical condition, we tested 16 items involving PIs in preverbal position co-occurring with sentential negation, which we do not further investigate in the present study. Within each condition we manipulated the PI by including sentences with ningú, res, mai and cap with four items per lexical item in each condition (see supplementary materials for a table including examples of all conditions). Additionally, we also manipulated the expected response to control for a potential bias towards TRUE responses, so half of the items in each condition had a TRUE expected answer and the other half had a FALSE expected answer. The task was piloted by 8 Catalan native speakers.

3.3.3. Participants

We gathered data from 92 Catalan L3/Ln learners, who were students enrolled at a university in the United Kingdom, Portugal and Brasil, Spain and Italy, their ages ranged from 18 years to 24. Participants were divided across two dimensions: their L1 (L1 English, n = 41; L1 Italian, n = 26; and L1 Spanish/Portuguese, n = 12 + 13) and their proficiency level (Beginner A1, n = 31; Beginner A2, n = 29; Intermediate B1/B2, n = 32).Footnote11 We gathered information regarding their knowledge of other foreign languages learnt prior to the learning of Catalan, and L1 Romance speakers participants reported having learnt English and Spanish or French; L1 English speakers reported having L2 Spanish and/or French. It must be noted that the L1 English participants were Advanced (>B2) speakers of Spanish, a fact we considered to be relevant to understand the results obtained from the experiment (see Section 4). Amongst the participants who did not speak a Romance language as their L1, we excluded those who had French as their only Romance foreign language.Footnote12 Participants provided information regarding their exposure to Catalan and there were no cases with substantial outside-the-classroom exposure. The participants’ recruitment was done in collaboration with Institut Ramon Llull (the Catalan public institution responsible for promoting the Catalan language and culture abroad and that coordinates Catalan studies in 150 universities around the world), as all our participants were enrolled in Catalan studies courses that were part of the university network XarxaLlull.

3.3.4. Procedure and ethical considerations

All tasks were hosted online via Pavlovia.org and scripted in PsychoPy. Prior to the tasks, tutors and students were sent the information sheet and consent form online. Once they agreed to take part in the test, they were sent the code to access the battery of experiments and instructions. The participants took part in the experiment between 2021 and 2022. This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Research Ethics Committee at King’s College London and the protocol was approved by the ethics committee at the School of Education, Communication and Society at King’s College London (MRA-20/21-21537). All subjects gave informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

4. Results

4.1. Data trimming

Results were coded binarily. The target context was coded based on the reading given (single negation vs. existential reading) – recall that we only focus on the non-veridical contexts (questions and conditions) for which the expected reading in Catalan was the existential one. Our analysis was conducted in the R environment (R Core Team, Citation2020). Separate models were employed for each context, as they targeted different readings. Given the binary nature of the data, we used Generalised Mixed-Effects Logistic Regression models to explore the effects of group – L1-English, L1-Spanish/Portuguese, L1-Italian –, proficiency – beginner (A1), high beginner (A2); intermediate (B1-B2) –, lexical items – ningú, res, mai, cap – Footnote13, and syntactic context (question, conditional) on the binary readings. We discuss model selection and the factors that made it to the model with the best fit below.

4.2. Analysis of the results

We first analysed the results of the distractor itemsand only one participant was excluded due to their low accuracy (<80%). The data showed that participants exhibited high levels of accuracy across all groups and proficiency levels (see supplementary materials for the descriptive results). We take this to suggest that participants were able to complete the task and effectively interpret the target sentences in relation to the provided context.

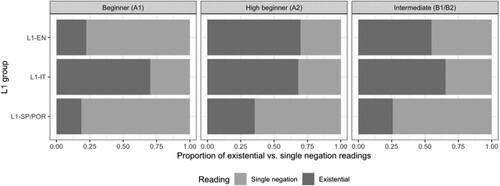

We now turn our focus to the context of interest – the non-veridical context. Recall that this context consisted of two conditions: questions and conditionals. below displays the proportion of single negation and existential readings provided by participants, categorised by L1 group and proficiency level, in relation to the question condition.Footnote14

Firstly, within the Beginner (A1) groups, only the L1-IT group exhibited high proportions of existential readings (M = .71; SD = .45), whereas the other two groups displayed low proportions of existential readings (L1-EN: M = .22; SD = .41, & L1-SP/POR: M = .18, SD = .39). Moreover, within the High beginner (A2) groups, we observed a sharp increase in the proportion of existential readings for the L1-EN group (M = .69; SD = 46), which is comparable to that of the L1-IT group (M = .68; SD = 46). Conversely, the L1-SP/POR group did not exhibit much improvement within the High beginner (A2) group, and their proportion of existential readings remained relatively low (M = .35; SD = 48). In the Intermediate groups (B1/B2), the L1-IT groups continued to show similar proportions of existential readings (M = .65; SD = .47), while the L1-SP/POR group demonstrated a low proportion of existential readings (M = .25; SD = 44). Interestingly, the L1-EN group displayed a decrease in the proportion of target existential readings (M = .54; SD = 49) in the Intermediate (B1/B2) group as compared to the High beginner (A2) group.

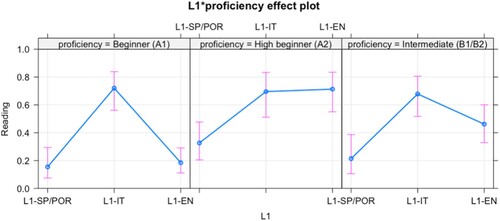

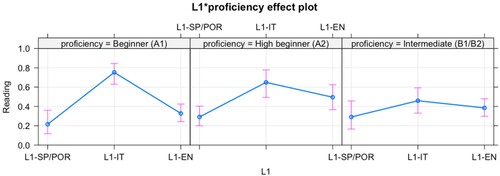

To investigate the factors that influenced participants’ responses, we conducted a generalised linear mixed-effect logistic regression and we started off with the following fixed-effects: L1 (L1-EN, L1-IT, L1-SP/POR), Proficiency (Beginner, High Beginner, Intermediate), and Lexical Item (res, ningú, mai, cap) as fixed effects and all possible interactions. We also incorporated random effects of participant and experimental item, as well as random slope of participant by experimental item. Beginning with the full model, we applied backward selection performing a maximum likelihood ratio comparison between models until we arrived at the best-fit model. Our final model included L1, Proficiency group, and their interaction (L1*Proficiency_Group). The statistical analysis showed that these factors significantly influenced the proportion of existential readings (see supplementary materials for the full model). The outcomes showed that the L1-IT group displayed a significantly greater proportion of existential readings compared to the L1-POR group (β = 2.68, p > .001), while the L1-EN group exhibited a similar proportion of existential readings (β = .21, p = .595). With regards to Proficiency groups, the High beginner group (A2) demonstrated a significantly higher proportion of existential readings than the Beginner (A1) group (β = .99, p = .019), whereas the Intermediate group yielded proportions like those of the Beginner groups (β = .41, p = .418). below visualises the two-way statistical interaction, revealing a differential outcome modulated by L1 and Proficiency group. We further investigated this interaction through planned post-hoc comparisons.

The post-hoc comparisons (see supplementary materials) showed that the only significant contrasts involved the L1-EN groups. Specifically, the High beginner group demonstrated a significant increase in the proportion of existential readings compared to the Beginner group, indicating a more target-like interpretation at the higher proficiency level. However, the L1-EN Intermediate group showed a significant decrease in target-like interpretation compared to the High beginner groups, suggesting a potential loss of such interpretation at higher proficiency levels.

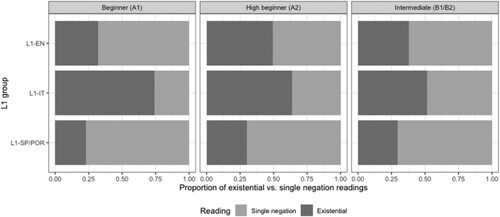

We now shift our focus to the second condition of interest, the conditional condition. below displays the distribution of existential and single negation readings assigned by participants, grouped by both L1 and proficiency level.

In the conditional structure condition, we observed a pattern like the one seen with questions. Specifically, within the Beginner (A1) groups, the L1-IT group had a higher proportion of existential readings (M = 74.1; SD = .44) compared to the other two Beginner groups, which had lower proportions of such readings (L1-EN: M = .32, SD = .46, & L1-SP/POR: M = .22, SD.42). Across the High Beginner groups, all three groups showed similar proportions of existential readings (L1-EN: M = .49, SD = .50, L1-IT: M = .63, SD = 48, & L1-SP/POR: M = .31, SD.46). For the Intermediate groups (B1/B2), the L1-EN (M = .37, SD = .48) and L1-SP/POR groups (M = .29, SD = .46) exhibited a similar pattern. Notably, the L1-IT group showed moderately lower proportions of existential readings (M = .45, SD = .51) than the other two L1-IT groups.

We performed a similar analysis to the one conducted in the question condition, where we started off with the same fixed effects in the maximal structure and applied backward selection until arriving at the model with the best fit. The final model included L1 and Proficiency Group, as well as their interaction. The statistical model confirmed that L1, Proficiency group and their interaction significantly affected the proportion of existential readings – outcomes of the model can be found in the supplementary material file.

The model revealed that the only significant difference was between the L1-IT group and the L1-POR group, with the former having significantly higher proportions of existential readings (β = 2.41, p > .001). This is illustrated in the effect plot shown in below.

To investigate these differences further, we conducted planned post-hoc comparisons (see supplementary materials). The findings indicate that the L1-SP/POR and L1-EN groups did not exhibit significant differences across proficiency groups within the same L1 group. However, the L1-IT group demonstrated a significant contrast between the Beginner and Intermediate group, suggesting a gradual decline in target-like readings.

5. Discussion

Our aim was to investigate how multilingual learners of Catalan acquire the distribution of Catalan Polarity Items. Additionally, we used this study to gain further insights into L3/Ln grammatical development and how such development interacts with certain linguistic factors such as lexical items, L1, proficiency level, as well as with the way these items are taught in the Catalan Foreign Language classroom. Our initial research question focused on whether learners of Catalan could successfully acquire non-veridical readings of PIs, and if so, whether any discernible developmental patterns emerged. Prior to delving into the developmental aspect, we first examined how beginner learners with low proficiency and limited exposure to Catalan interpreted such items. This was extremely important as it allowed us to establish a starting point in the acquisition process, which is crucial for mapping and predicting subsequent developmental patterns (González Alonso & Rothman, Citation2017; Rothman et al., Citation2019).

5.1. L3/Ln initial stages

The results from the two L1 Romance groups (L1-IT and L1-SP/POR) provide evidence of initial transfer from Italian and Spanish/Portuguese respectively. This can be seen in two distinct outcomes. Firstly, the L1-IT Beginner (A1) group demonstrates high proportions of existential readings in both questions and conditionals, which Italian also licences. On the other hand, the L1-SP/POR Beginner (A1) group exhibits significantly low proportions of existential readings in Catalan, which both Spanish and Portuguese disallow. Thus, the results indicate transfer from Italian and Portuguese/Spanish. The data so far is consistent with a potential L1 default approach (Hermas, Citation2010, p. 2014), the Typological Primacy Model (Rothman, Citation2010, Citation2011, Citation2015; Rothman et al., Citation2019) and the Language of Communication Model (Fallah & Jabbari, Citation2018) – all of which would predict transfer from Italian, Portuguese and Spanish, though for different reasons.

Interestingly, the results for the L1-EN Beginner (A1) group are not as straightforward. As discussed above, their proportion of existential readings in Catalan is relatively low, similar to that of the L1-SP/POR Beginner (A1) group. It is worth noting that English negative polarity items allow these readings in questions and conditionals. Therefore, if English transfer had occurred, one would expect a higher proportion of existential readings in line with the L1-IT group’s results. However, the low proportion of existential readings has, at the very least, two potential explanations.

Firstly, considering that English encompasses two sets of items, namely negative polarity items and negative quantifiers, learners may have mapped Catalan PIs onto negative quantifiers instead of negative polarity items. However, this explanation seems unlikely. As mentioned in Section 2.2 earlier, the review of textbooks revealed consistent presentation of these items within negative concord configurations, where polar items occupy postverbal position (i.e. No + V + PI). This presentation effectively establishes them as strong Negative Polarity Items (NPIs) licensed only by anti-veridical operators. Consequently, learners would receive little implicit or explicit evidence suggesting that Catalan PIs would be best mapped onto with English negative quantifiers. The second possible explanation is that L1-EN Beginner (A1) learners did not transfer English, but Spanish instead, their L2. All participants in this group had advanced (>B2) knowledge of Spanish. And recall that Spanish, unlike English, does not permit existential readings in these contexts. This aligns with the existing L3/Ln literature, which consistently demonstrates that when previous linguistic knowledge of a Romance language exists, there is Romance-to-Romance transfer (XXX). This phenomenon is well-documented in studies examining Spanish-English bilinguals acquiring L3 Brazilian Portuguese (e.g. Cabrelli et al., Citation2020; Giancaspro et al., Citation2015; Ionin et al., Citation2015; Montrul et al., Citation2011; Parma, Citation2017), as well as other studies involving various Romance languages (e.g. Foote, Citation2009; Bruhn de Garavito & Perpiñán, Citation2014).Footnote15

Therefore, it seems plausible to argue that the L1-EN Beginner (A1) group transferred their Spanish to Catalan. And so, the data from the three groups, coupled with the existing literature on Romance-Germanic-Romance language triads, indicates that, similar to the L1-IT and L1-SP/POR Beginner groups, the L1-EN Beginner group relies on holistic structural similarity as a determining factor for transfer selection during the initial stages, consistent with the Typological Primacy Model (TPM).Footnote16

5.2. L3/Ln development

Now that we have established the point of departure in the initial stages of acquisitionregarding the participants in our study, our focus shifts to L3/Ln development. Regarding our first research question, we hypothesised that learners would exhibit varying degrees of success at acquiring the target-like interpretation of PIs in these contexts, modulated by different factors. The results demonstrate asymmetrical development both across groups and within contexts within the groups.

The L1-IT Beginner group displayed target-like readings for the target items. However, as proficiency increased, the High Beginner (A2) and Intermediate (B1) groups exhibited moderately lower proportions of existential readings in both questions and conditionals, indicating a gradual decline in accuracy. This raises an important question: why do learners, who initially demonstrated target-like readings, experience a decrease in accuracy as their proficiency increases? The answer may lie in the textbook review, which can serve as a proxy for the input learners receive at this stage. In the Catalan FL context, learners are exposed to evidence that suggests such elements are only licensed in anti-veridical contexts. Consequently, L1-IT learners gradually restrict the licensing possibilities initially afforded by Italian, transitioning from non-veridical licensing to solely anti-veridical licensing conditions. Similar findings were observed in a study involving Catalan-Spanish learners of L3 English (Puig-Mayenco et al., Citation2022).

Shifting our attention to the L1-SP/POR groups, the results present some differences. The L1 SP/POR Beginner (A1) group already exhibited low proportions of existential readings, which persisted across different proficiency levels. Neither the L1 SP/POR High Beginner (A2) nor the L1 SP/POR Intermediate groups surpassed this initial lack of facilitation, as evidenced by consistently low proportions of existential readings. These learners appear unable to acquire the licensing of Catalan PIs in non-veridical contexts, while the initial NPI mapping remains throughout the development process. This persistence can be attributed to the limited evidence learners receive, which predominantly supports the anti-veridical (i.e. negative readings) licensing of these items in Catalan. These learners needed observable evidence to help overcome the initial non-facilitation and reconfigure the mapping assigned to these items as PIs, leading to the emergence of existential readings in questions and conditionals.

The L1-EN groups behave distinctively. As mentioned in the results the High Beginner (A2) group exhibited higher proportions of existential readings compared to the Beginner (A1) group indicating some restructuring of the PIs. However, these gains in accuracy were observed solely in the Question condition. Similar to the L1-IT groups, there was a decrease in accuracy when comparing the Intermediate (B1) group to the High Beginner (A2) group, indicating a loss of initially acquired knowledge. In the conditional condition, there appeared to be a trend of initial improvement followed by a subsequent decline in accuracy, although it did not reach statistical significance. As predicted based on the frequency and saliency of these items in questions, the Question condition was acquired first. It is important to note that although not explicitly taught at these levels, learners are likely to encounter PIs in questions with non-veridical readings implicitly. Additionally, since English, one of the languages they speak, permits this, it may facilitate the initial increase in accuracy. However, we expected that acquiring this in questions would extend to the Conditional condition, which is not supported by the data here. As discussed earlier, there is an absolute lack of explicit and implicit evidence regarding the availability of these readings in conditional structures in textbooks ranging from A1 to B1 levels. Therefore, the absence of such evidence hinders acquisition, even if these readings could have been recoverable from English. This suggests that learners do not generalise existential readings across non-veridical contexts. It is also worth noting that the initial improvement observed in the Questions condition diminishes as proficiency increases, mirroring the findings in the L1-IT group. Once again, this can be explained by the consistent presentation of Catalan PIs in textbooks as licensed exclusively in anti-veridical contexts.

The overall post-beginner picture reveals that the development of Catalan PI is a complex process that can provide insights into theoretical questions regarding L3/Ln development. Our findings align with the claims of the Cumulative Input Threshold Hypothesis (CITH) (Cabrelli & Iverson, Citation2023). Recall that CITH predicts that initial non-facilitation is overcome more rapidly when it comes from a transferred L2 rather than a transferred L1. As previously mentioned, evidence supporting CITH is limited and mixed, with some studies indicating a strong effect of order of acquisition (Cabrelli et al., Citation2020; Cabrelli & Iverson, Citation2023), and others highlighting the influence of language dominance (Puig-Mayenco et al., Citation2022). Our study confirms the tenets of CITH, demonstrating that the initial transferred source plays a significant role in shaping the grammatical development of an L3/Ln. In our study, we observed that transferring an L2 can lead to more rapid restructuring than transferring an L1, as evident in the results of the L1-EN groups, who exhibited traces of acquisition at a faster pace compared to the L1-SP/POR groups. Considering that all participants were learning Catalan in a context where their L1 was the dominant language, it is reasonable to assume that they maintained dominance in their L1, making their L2 the least dominant language. Our data do not allow us to disentangle whether the faster restructuring arises from transferring the L2 or the least dominant language. An additional significant finding is the non-linear developmental patterns observed, which further contribute to the complexities of L3 grammatical development. Only by integrating all these factors and considerations can we obtain a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of L3 grammatical development.

6. Pedagogical implications

The empirical findings indicate that the polar nature of Catalan PIs, and consequently their non-veridical licensing, is not fully acquired by the different L1 speakers included in this study. There is a tendency for Catalan PIs to be categorised as NPIs licensed by anti-veridical operators. These results align with the analysis of Catalan Ln textbooks, where the input and instruction regarding these elements are primarily focused on their licensing in anti-veridical contexts (see Section 2.2). Marsden et al.’s (Citation2018) study on the acquisition of the PI properties of any in L2 English by Najdi Arabic-speaking learners demonstrates that learners’ most robust knowledge of any corresponds to what is covered in textbooks. Our results align with this observation, as our participants’ implicit understanding of Catalan PIs coincides with the presentation in textbooks as well. Considering that Catalan textbooks predominantly adopt an anti-veridical licensing-oriented approach to Catalan PIs, learners have limited opportunities to acquire the polar interpretation of these items. Furthermore, our cross-sectional study reveals a stagnation and subsequent decrease in the expected interpretation of the non-existential reading of Catalan PIs among all learners as their proficiency increases. Additionally, L1-POR/SP learners face challenges in overcoming initial non-facilitation.

Pedagogically, our results highlight the challenges that, without observable evidence in explicit and incidental input, learners face when it comes to note the ‘gap’ or ‘mismatch’(following the terms used by Ellis, Citation1994, Citation2006) in their grammars – regardless of their L1/L2/Ln status. Among all non-veridical contexts, questions and conditionals are the only two contexts that are partially presented in some textbooks, albeit with limited exposure and relatively late in the sequence. We argue that these contexts should continue to be included as they are the most frequent, salient, and representative contexts illustrating the polar behaviour in Catalan (Llop, Citation2020). However, the acquisition of the polar nature of PIs in Catalan would benefit from early exposure and instruction to these contexts, integrated as part of a system that encompasses other productive non-veridical contexts. Providing transparent instruction on the polar nature of the target elements from the early stages of the instructional pathway, while gradually introducing more complex non-veridical contexts, would contribute to reinforcing learners’ understanding of Catalan PIs. This approach is particularly reasonable considering our results, which contradict those of Marsden et al. (Citation2018). Our findings demonstrate that learners do not fully acquire the distribution of PIs beyond the instructed contexts found in textbooks. If anything, the current presentation of PIs does not assist some learners in overcoming initial non-facilitation and leads others to lose their initial facilitation.

Herein, we articulate the preliminary tenets of a proposal for the instruction of PIs in Catalan adapting for the sequencing of grammar content the following criteria that Long (Citation2015) proposed for the sequencing of tasks.

Valency: it refers to the communicative value, reach or coverage of the target linguistic elements and what they are used for. Although the association of PIs with communicative tasks is already visible in some CFL textbooks (see Section 2.2 for a summary), the sequence should incorporate more opportunities to explore each individual item framed as part of a system to enhance the overall acquisition. This could be done, in the context of task-based sequences, by means of focus on form activities (Long, Citation1991).

Frequency, complexity, and difficulty: the teaching of the negative system should follow a planned spiral curriculum-based approach (Bruner, Citation1960), where learners would be exposed to explicit and implicit input throughout the learning path. This approach would give learners the opportunity to see multiple and various cues that would allow them to reinforce their knowledge of PIs and the negative system, as well as it would expose them to further evidence to subsequently access the full distribution of PIs – see Carrell et al. (Citation1988) and Edmonds et al. (Citation2021) encoding variability hypothesis.Footnote17

Learnability: Following Pienemman’s (Citation1989) learnability (and teachability hypothesis), the instructional sequence should be harmonised with developmental sequences. In that respect, studies such as this one, contributing to understanding the complexity of the comprehension of non-veridical contexts, are pivotal in putting forward instructions that are coherent with the building of the interlanguage (Selinker, Citation1972). For the instruction to progress according to learners’ psycholinguistic difficulty to access (and interpret) the linguistic forms, the teaching sequence should create opportunities to first present more frequent, salient and communicatively useful forms and contexts (i.e. interrogative sentences followed by conditionals). Progressively, the input should be enhanced, and the availability, saliency and accessibility of more difficult and opaque forms increased (see Collins et al., Citation2009). Specifically, regarding our study, the gradual decline in accuracy could be reverted if, following Bjork and Bjork (Citation2011), learners were faced with practice presenting desirable difficulties. These difficulties, following Edmonds et al. (Citation2021) are ‘conditions that may create short-term challenges for learning but that ultimately optimise retention’ (Edmonds et al., Citation2021: Section 2).Footnote18

The preliminary tenets presented above are an attempt to build dialogue between empirical results and the review of textbooks; a symbiosis which, ultimately, allows us to outline a list of theory and research-driven principles on how to present (implicit and explicit input) and how to sequence the teaching of the Catalan negative system. Additionally, the study developed helps us know how to design a teaching sequence able to cater to learners’ built-in syllabus (Corder, Citation1967; Long, Ellis, Citation2005), including both learners’ different previously acquired linguistic knowledge (L1 and Lns), and their readiness to develop explicit knowledge and, more importantly, implicit knowledge of the target grammar.

7. Conclusion

Our study reveals that the grammatical development of L3/Ln learners is characterised by significant variation and complexities, aligning with the claims made by Slabakova (Citation2017) and Cabrelli and Iverson (Citation2023). To obtain a comprehensive understanding of L3/Ln developmental patterns, it is crucial to consider factors such as the learners’ L1 and the order of acquisition of the transferred language. These factors have proven to be instrumental in comprehending the developmental patterns of PIs in the context of Catalan as a Foreign Language. Notably, our results demonstrate that the acquisition of PIs occurs as a system and is not influenced by specific lexical items. Interestingly, the findings also highlight the influential role of how PIs are presented in CLF textbooks in shaping and restructuring learners’ understanding of PIs within their grammar. Thus, the empirical study serves as a foundation for outlining preliminary principles for a sequenced approach to teaching Catalan PIs and the negative system as a whole. This initial proposal bridges our research with Instructed Second Language Acquisition studies and sets the stage for a Practice-based research study (following the line of Sato & Loewen, Citation2022; Spada & Lightbown, Citation2022) to assess the impact of an acquisitionally and pedagogically-informed teaching sequence on the development of the negative system in Catalan L3/Ln learners. Ultimately, although our study has a limited focus, we believe that the design, outcomes, and principles of the teaching sequence can be extended to other linguistic domains, language triads, and instructional contexts.

ijm-1848-File002

Download MS Word (25.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Institut Ramon Llull and their instructors of Catalan Foreign Language courses in Italy, Spain, Portugal, Brazil and the United Kingdom for their assistance in the data collection. We would also like to thank the audiences at xxxx for their enriching insights on previous versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The experimental materials for the three tasks (background questionnaire, proficiency task and truth-value judgement task) will be made available upon acceptance for publication on the IRIS database (www.irisdatabase.org). The raw data will be made available upon request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The reader must bear in mind that Catalan can behave as both a strict and non-strict NC language. Although NC relations were part of the phenomena studied in the wider project of which this piece of research is part, they do not constitute the focus of this article.

2 In this paper we refer to standard Catalan, and we leave aside those dialects (mainly Catalan spoken in Tortosa and Valencia), where the items studied behave as NCIs and do not show any of the PIs characteristics, as in the other Catalan varieties.

3 Data from Arnaiz (Citation2002) for Catalan have been adapted according to IEC (Citation2016: 35.4.1.3); Spanish data have been modified according to Bosque (Citation1980, p. 3.2), who also includes ordinals such as primero and último as licensers of PIs. Data for French have been adapted according to Mosegaard Hansen (Citation2013, p. 72), based on Muller (Citation1991, p. 265), with differences within this language being linked to the variability in the licensing conditions of each of the lexical items of the French system (with jamais being the item which can be licensed in more different non-veridical contexts, followed by rien, aucun, personne. The licensing conditions of nulle part,nul and plus are very restricted).

4 Llop (Citation2020) points out an ongoing process of linguistic change regarding the acceptance of the licensing of the elements studied in different age groups of Catalan native speakers, with elder informants accepting non-veridical licensing in a wide range of contexts, and younger speakers restricting it to interrogative and, to a lesser extent, conditional clauses.

5 The CFL textbooks analysed were a selection of 22 of the most recent and common textbooks in CFL classrooms (see the full list in the supplementary materials file). The aspects analysed regarding the general presentation of the Catalan negative system were the following ones:

(a) the way that the elements integrating the negative system were presented (as lexical items linked to a communicative function) or as part of a system;

(b) the contexts that were explicitly part of the instruction and the nature of the overt input that accompanied the instruction regarding the licensing conditions of Catalan PIs;

(c) the implicit input in textbooks, through which learners were indirectly or incidentally exposed to the use of PIs in non-veridical contexts;

(d) negative evidence was also taken into consideration in order to determine which contexts and uses were neither covered by instruction nor frequently observable in the input.

Additionally, regarding the instruction of the phenomenon studied, three aspects were analysed:

i. the properties and the sequencing of the components of the negative system presented to students;

ii. the consistency of the sequencing of grammatical contents and the concerns for the L2/Ln development; and

iii. the model of grammar teaching: including the metalanguage used, the syllabus, the instructional strategies and the inclusion of activities regarding multilingualism awareness and mediation.

6 Gens, cap and res ‘(not) at all’ are presented for the first time with other degree quantifiers when talking about quantities of food; mai ‘never’ makes its first appearance in those units focusing on the frequency of daily life activities. Ningú is introduced in A2 and B1 textbooks to refer to the absence of people involved in different social activities.

7 The only textbook that include input processing activities regarding the meaning and interpretation of polar items are A punt 4 (B2; unit 5).

8 Although CITH is the only hypothesis to date that directly attempts to model L3 grammatical development, some of the current proposals on transfer/CLI in L3 acquisition do discuss development as transfer/CLI is not envisioned by the models to be restricted to the initial stages (See Slabakova, Citation2017; Westergaard et al., Citation2017; Westergaard, Citation2021)

9 The proficiency taskwas self-designed due to the lack of a standardised test for Catalan. Example (i) is one of the questions created for this task. It is taken from the A1 level section.

2. Els gossos _____________ aigua de la font i _____________ al riu quan fa calor.

‘Dogs (verb 3rd pl) water from the fountain and (pronominal verb 3rd pl) in the river when it’s hot.

a. beuen / banyen (they drink / they swim)

b. veuen / es banyen (they see / they swim)

c. beuen / es banyen (they drink / they swim)

d. No ho sé. (I don’t know)

10 The distractors in the study consisted of sentences with the same syntactic structure as the target sentences but did not include negative elements in them. This was done to ensure that participants saw conditionals and questions without negative elements in it.

11 The participants distributed as follows: L1-English (beg = 14, beg.A2 = 10, intermediate = 17); L1-Italian (beg = 8, beg.A2 = 11, intermediate = 7); L1-Spanish/Portuguese (beg = 9, beg.A2 = 8, intermediate = 8).

12 This was done primarily for two reasons: (a) the licensing of French PIs in the contexts of our study are more dependent on lexical items and speakers (Hansen, Citation2013: table 2.3; Muller, Citation1991, p. 265), making it less uniform than what the behaviour of these items in the other languages under investigation; and (b) although this subgroup would have been interesting as a group for our study, we only had six participants the L1-EN group that fit this profile and therefore the subgroup was too small to be included in the statistical analysis – we, however, briefly touch upon this in the discussion section.

13 Of all the items in the negative paradigm in Catalan, we decided to manipulate the items cap, res, ningú and mai because of its higher frequency in use compared to other negative elements, such as gens and enlloc (data from the Diccionari de freqüències, Institut d’Estudis Catalans). Despite its polar use, gaire was not considered for this experiment because it does not show any NCI properties.

14 Descriptive statistics for both conditions can be found in the supplementary materials.

15 Further evidence supporting this argument comes from the six participants who possessed advanced knowledge of French instead of Spanish. It is important to note that we excluded these participants due to (a) the specific (and sometimes idiosyncratic) distribution of these items in French and (b) the insufficient number of participants with this profile to form a separate subgroup. However, upon closer examination of their data, it becomes apparent that language typology plays a significant role. Specifically, these participants appeared to interpret Catalan PIs based on French patterns (recall from table 1 and footnote 3 above that French allows for non-veridical licensing modulated by condition and lexical item). Participants have a high proportion of existential readings in the question condition (M = .71, SD = .26), which is less restricted in French, but a comparatively low proportion in the conditional structure (M = .41, SD = .29), which is more restricted. These findings suggest that initially, these participants transferred French to Catalan rather than English.

16 However, see Westergaard (Citation2021) for an alternative explanation of why Romance transfer is likely to occur in our study.

17 Following Ellis (Citation2022, p. 39), we suggest that the instruction pathway should rely on and foster ‘explicit consolidation of a construction to allow for a subsequent repeated usage/practice/processing/prediction process which results in better learning outcomes in terms of accuracy/entrenchment/automatization/fluency/breadth/depth/richness/precision/idiomaticity and nativelike selection in collocation and phraseology/proficiency/pragmatic competence’.

18 See A punt 6 (C2; unit 6, in press) for an implementation of these principles in higher levels (C1-C2). Two of the authors of this paper were involved in the design and creation of these materials as authors [Ares Llop Naya, Anna Paradís] and content coordinator [Ares Llop Naya]. In unit 6, the textbook presents a task-based learning sequence in which the use of PIs in questions and conditionals is revised, and more complex non-veridical contexts (such as the ones in ) are presented to learners. The items are framed within a meaningful communicative context, and are brought to the attention of learners by means of an oral comprehension, different input processing activities, guided output-production exercises and a task to compare and contrast the use of PIs in the languages known by the learners of the class.

References

- Arnaiz, A. (2002). Palabras-N en contextos no negativos. Lexis, XXVI(1), 79–115.

- Bardel, C., & Falk, Y. (2007). The role of the second language in third language acquisition: The case of Germanic syntax. Second Language Research, 23(4), 459–484. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658307080557

- Bardel, C., & Falk, Y. (2012). The L2 status factor and the declarative/procedural distinction. In J. Cabrelli Amaro, S. Flynn, & J. Rothman (Eds.), Third language acquisition in adulthood (pp. 61–78). John Benjamins.

- Bardel, C., & Falk, Y. (2012). Behind the L2 Status factor: A neurolinguistic framework for L3 research. In J. Cabrelli Amaro, S. Flynn, & J. Rothman (Eds.), Third language acquisition in adulthood (pp. 61–78). John Benjamins.

- Bardel, C., & Sánchez, L. (2017). The L2 status factor hypothesis revisited: The role of metalinguistic knowledge, working memory, attention and noticing in third language learning. In T. Angelovska & A. Hahn (Eds.), L3 syntactic transfer: Models, new developments and implications (pp. 85–102). John Benjamins.

- Bardel, C., & Sánchez, L. (Eds.). (2020). Third language acquisition: Age, proficiency and multilingualism. Language Science Press. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4138753

- Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. In M. A. Gernsbacher, R. W. Pew, L. M. Hough, & J. R. Pomerantz (Eds.), Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society (pp. 56–64). Worth Publishers.

- Bosque, I. (1980). Sobre la negación. Cátedra.

- Bruhn de Garavito, J., & Perpiñán, S. (2014). Subject pronouns and clitics in the Spanish interlanguage of French L1 speakers. In: Canadian Linguistic Association Conference Proceedings.

- Bruner, J. (1960). The process of education. Harvard University Press.

- Cabrelli, J., & Iverson, M. (2023). Why do learners overcome non-facilitative transfer faster from an L2 than an L1? The cumulative input threshold hypothesis. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–27, ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2023.2200252

- Cabrelli, J., Iverson, M., Giancaspro, D., & Halloran González, B. (2020). Implications of L1 versus L2 transfer in L3 rate of morphosyntactic acquisition. In K. V. Molsing, C. Becker Lopes Perna, & A. M. TramuntIbaños (Eds.), Linguistic approaches to Portuguese as an additional language (pp. 11–33). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Carrell, P., Devine, J., & Eskey, D. (Eds.). (1988). Interactive approaches to second language Reading. CUP.

- Collins, L., Trofimovich, P., White, J., Cardoso, W., & Horst, M. (2009). Some input on the easy/difficult grammar question: An empirical study. The Modern Language Journal, 93(3), 336–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00894.x

- Corder, S. P. (1967). The significance of learners’ errors. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 5, 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral.1967.5.1-4.161

- Edmonds, A., Gerbier, E., Palasis, K., & Whyte, S. (2021). Understanding the distributed practice effect and its relevance for the teaching and learning of L2 vocabulary. Lexis [Online]. https://doi.org/10.4000/lexis.5652

- Ellis, R. (1994). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford University Press.

- Ellis, R. (2005). Principles of instructed language learning. Science Direct, 33, 209–224.

- Ellis, R. (2006). Current issues in the teaching of grammar: An SLA perspective. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 83–107. https://doi.org/10.2307/40264512

- Ellis, N. (2022). Second language learning of morphology. Journal of the European Second Language Association, 6(1), 34–59. https://doi.org/10.22599/jesla.85

- Espinal, M. T. (2002). La negació. In J. Solà, M. R. Lloret, J. Mascaró, & M. PérezSaldanya (Dirs.), Gramàtica del catalàcontemporani (Vol. 3, pp. 2729–2793). Empúries.

- Espinal, M. T., Etxeberria, U., & Tubau, S. (2021). On the nature and limits of polarity sensitivity, negative polarity and negative concord. Ms. UniversitatAutònoma de Barcelona and CNRS/IKER.

- Espinal, M. T., & Llop, A. (2022). (Negative) Polarity items in catalan and other trans-pyrenean romance languages. Languages, 7(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7010030

- Espinal, M. T., & Tubau, S. (2016). Meaning of words, meaning of sentences. Building the meaning of n-words. In S. Fischer & C. Gabriel (Eds.), Manual of grammatical interfaces in romance linguistics (pp. 187–212). Mouton de Gruyter.

- Falk, Y., & Bardel, C. (2011). Object pronouns in German L3 syntax: Evidence for the L2 status factor. Second Language Research, 27(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658310386647

- Fallah, N., & Jabbari, A. A. (2018). L3 acquisition of English attributive adjectives: Dominant language of communication matters for syntactic cross-linguistic influence. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 8(2), 193–216. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.16003.fal

- Flynn, S., Foley, C., & Vinnitskaya, I. (2004). The cumulative-enhancement model for language acquisition. Comparing adults’ and childrens’ patterns of development in first, second and third language acquisition. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790710408668175

- Foote, R. (2009). Transfer in L3 acquisition: The role of typology. In Y. I. Leung (Ed.), Third language acquisition and universal grammar (pp. 89–114). Multilingual Matters.

- Generalitat de Catalunya. (2022). Decret 243/2022, de 18 d'octubre, pelquals'estableixenels currículums de nivellBàsic (A2) i del nivellAvançat (C1 i C2) delsensenyaments de règim especial de diversos idiomes. Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya Núm. 8777 - 21.10.2022.

- Giancaspro, D., Halloran, B., & Iverson, M. (2015). Transfer at the initial stages of L3 Brazilian Portuguese: A look at three groups of English/Spanish bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 18(2), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728914000339

- Giannakidou, A. (1998). Polarity sensitivity as (non)veridical dependency. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Giannakidou, A. (2000). Negative … concord? Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 18(3), 457–523. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006477315705

- Gil, K., & Marsden, H. (2013). Existential quantifiers in second language acquisition: A feature reassembly account. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 3, 117–149. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.3.2.01gil

- Gil, K., Marsden, H., & Whong, M. (2019). The meaning of negation in the second language classroom: Evidence from ‘any’. Language Teaching Research, 23(2), 218–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168817740144

- González Alonso, J. (2023). Generative approaches to third language acquisition. In J. Cabrelli, A. Chaouch-Orozoco, J. González Alonso, S. M. Pereire Soares, E. Puig-Mayenco, & J. Rothman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of third language acquisition (pp. 23–42). Cambridge University Press.

- González Alonso, J., & Rothman, J. (2017). Coming of age in L3 initial stages transfer models: Deriving developmental predictions and looking towards the future. International Journal of Bilingualism, 21(6), 683–697. doi: 10.1177/1367006916649265

- González Alonso, J., & Rothman, J. (2017). Coming of age in L3 initial stages transfer models: Deriving developmental predictions and calling for theory conservatism. International Journal of Bilingualism, 21, 683–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006916649265

- Hansen, M. M. (2013). Negation in the history of French. In D. Willis (Ed.), The history of negation in the languages of Europe and the Mediterranean: Vol. I: Case studies (pp. 51–76). Oxford University Press.

- Hermas, A. (2010). Language acquisition as computational resetting: Verb movement in L3 initial state. International Journal of Multilingualism, 7(4), 202–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2010.487941

- Hermas, A. (2014). Multilingual transfer: L1 morphosyntax in L3 English. International Journal of Language Studies, 8(2), 1–24.

- IEC (Institut d'Estudis Catalans). (2016). Gramàtica de la llengua catalana. Institut d'Estudis Catalans.

- Ionin, T., Grolla, E., Santos, H., & Montrul, S. (2015). Interpretation of NPs in generic and existential contexts in L3 Brazilian Portuguese. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 5(2), 215–251. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.5.2.03ion

- Laka, I. (1990). Negation in syntax: On the nature of functional categories and projections [PhD thesis]. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, United States.

- Linebarger, M. C. (1987). Negative polarity and grammatical representation. Linguistics and Philosophy, 10(3), 325–387. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00584131

- Llop, A. (2020). Perspectives diacròniques en la variació microsintàctica sincrònica. Reanàlisis i cicles en els sitemes negatius del català i d'altres varietats del contínuum romànic pirinenc. Edicions i Publicacions de la Universitat de Lleida.

- Long, M. (1991). Focus on form: A design feature in language teaching methodology. In K. Bot, R. Ginsberg, & C. Kramsch (Eds.), Foreign language research in cross-cultural perspectives (pp. 39–52). John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/sibil.2.07lon

- Long, M. (2015). Second language acquisition and task-based language teaching. Wiley Blackwell.

- Marsden, H., Whong, M., & Gil, K. (2018). What’s in the textbook and what’s in the mind: Polarity item any in learner English. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 40(1), 91–118. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263117000018

- Martins, A. M. (2000). Polarity items in Romance: Underspecification and lexical change. In G. Pintzuk & A. Warner (Eds.), Diachronic syntax: Models and mechanisms (pp. 191–219). Oxford University Press.

- Montrul, S., Dias, R., & Santos, H. (2011). Clitics and object expression in the L3 acquisition of BrazilianPortuguese: Structural similarity matters for transfer. Second LanguageResearch, 27, 21–58.

- Muller, C. (1991). La négation en Français: Syntaxe, sémantique et éléments de comparaison avec les autres langues romanes. LibrairieDroz.

- Na Ranong, S., & Leung, Y. (2009). Null objects in L1 Thai – L2 English – L3 Chinese: An empirical take on a theoretical problem. In Y. Leung (Ed.), Third language acquisition and universal grammar (pp. 162–191). Multilingual Matters.

- Parma, A. (2017). Cross-linguistic transfer of object clitic structure: A case of L3 Brazilian Portuguese. Languages, 2(3), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages2030014

- Pienemann, M. (1989). Is language teachable psycholinguistic experiments and hypotheses. Applied Linguistics, 10(1), 52–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/10.1.52

- Pinto, J., & Alexandre, N. (Eds.) (2021). Multilingualism and third language acquisition: Learning and teaching trends. Language Science Press.

- Progovac, L. (1994). Negative and positive polarity. A binding approach to polarity sensitivity. Cambridge University Press.

- Puig-Mayenco, E., Rothman, J., & Tubau, S. (2022). Language dominance in the previously acquired languages modulates rate of third language (L3) development over time: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(5), 1641–1664. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1792408

- R Core Team. (2020). R Core Team (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing. Available at: http://www.R-project.org

- Rothman, J. (2010). On the typological economy of syntactic transfer: Word order and relative clause high/low attachment preference in L3 Brazilian Portuguese. IRAL: International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 48, 245–273. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral.2010.011

- Rothman, J. (2011). L3 syntactic transfer selectivity and typological determinacy: The typological primacy model. Second Language Research, 27(1), 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658310386439

- Rothman, J. (2013). Cognitive economy, non-redundancy and typological primacy in L3 acquisition: Evidence from initial stages of L3 romance. In S. Baauw, F. Dirjkoningen, & M. Pinto (Eds.), Romance languages and linguistic theory 2011 (pp. 217–247). John Benjamins.

- Rothman, J. (2015). Linguistic and cognitive motivations for the typological primacy model (TPM) of third language (L3) transfer: Timing of acquisition and proficiency considered. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 18(2), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1017/S136672891300059X

- Rothman, J., González Alonso, J., & Puig-Mayenco, E. (2019). Third language acquisition and linguistic transfer. Cambridge University Press.

- Sato, M., & Loewen, S. (2022). The research–practice dialogue in second language learning and teaching: Past, present, and future. The Modern Language Journal, 106(3), 509–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12791

- Schwartz, B., & Sprouse, R. A. (1996). L2 cognitive states and the full transfer/full access model. Second Language Research, 12(1), 40–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/026765839601200103

- Schwartz, B., & Sprouse, R. A. (2021a). In defense of ‘copying and restructuring’. Second Language Research, 37(3), 489–493. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658320975831

- Schwartz, B., & Sprouse, R. A. (2021b). The full transfer/full access model and L3 cognitive states. Keynote Article. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 11(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1075/lab.20055.sch

- Selinker, L. (1972). Interlanguage. Product Information International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 10, 209–241. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral.1972.10.1-4.209

- Slabakova, R. (2017). The scalpel model of third language acquisition. International Journal of Bilingualism, 21(6), 651–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006916655413

- Spada, N., & Lightbown, P. (2022). In it together: Teachers, researchers, and classroom SLA. The Modern Language Journal, 106, 635–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12792

- Stadt, R. (2019). The influence of Dutch (L1) and English (L2) on third language learning: The effects of education, development and language combinations. LOT Publications.

- Tomlinson, B. (Ed.). (2016). Sla research and materials development for language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315749082

- Tubau, S. (2008). Negative concord in English and romance: Syntax-morphology interface conditions on the expression of negation. LOT.

- Watanabe, A. (2004). The genesis of negative concord: Syntax and morphology of negative doubling. Linguistic Inquiry, 35(4), 559–612. https://doi.org/10.1162/0024389042350497

- Westergaard, M. (2021). L3 acquisition and crosslinguistic influence as co-activation: Response to commentaries on the keynote ‘Microvariation in multilingual situations: The importance of property-by-property acquisition’. Second Language Research, 37(3), 501–518. https://doi.org/10.1177/02676583211007897

- Westergaard, M., Mitrofanova, N., Mykhaylyk, R., & Rodina, Y. (2017). Crosslinguistic influence in the acquisition of a third language: The linguistic proximity model. International Journal of Bilingualism, 21(6), 666–682. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006916648859

- Westergaard, M., Mitrofanova, N., Rodina, Y., & Slabakova, R. (2023). Full transfer potential in L3/Ln acquisition: Crosslinguistic influence as a property-by-property process. In J. Cabrelli, A. Chaouch-Orozoco, J. González Alonso, S. M. Pereire Soares, E. Puig-Mayenco, & J. Rothman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of third language acquisition (pp. 219–224). Cambridge University Press.

- Zwarts, F. (1995). Nonveridical contexts. Linguistic Analysis, 25, 286–312.