Abstract

Numerous attempts to explain the puzzle of the party-voter relationship have been made. Researchers explain vote choice referring to one’s social status, individual or group interests, sense of identity. All of them offer an interesting, but not complete explanation of the decisionmaking process. In the present paper, we study this phenomenon, using the brand personality approach, which focuses on consumers’ identity and emotional needs, according to which voter chooses a party which best resonates with an expression of the self he wishes to demonstrate (Street 2003). To examine the personalities of political brands, we refer to the concept of archetypes - a wellknown marketing research tool that enables to study of emotions and subconscious motivations that accompany all people’s choices. Using a mixed methodology, we verify what personality characteristics and dimensions (archetypes) voters use to describe Polish political parties and what needs and emotions accompanying party choice these archetypes indicate. The result is a portrait of political parties and their voters going beyond the traditional comparison of party manifestos, giving an insight into functional and emotional needs voting for a particular party meets.

Introduction

There are numerous studies that recognize political parties as brands, bringing about a possibility to analyze the party-voter relations from the political brand perspective, complementing the shortcomings of existing approaches, such as party identification theory or rational choice theory-based approaches (Phil Harris and Lock Citation2001; Smith Citation2001; White and de Chernatony Citation2002; Schneider Citation2004; Needham Citation2005, Citation2006; Scammell Citation2007; French and Smith Citation2008; Smith and French Citation2009; Nielsen Citation2017).

The political brand approach enables comprehensive explanation of how voters learn about parties, how they perceive them and how they behave when it comes to consumer’s (voters’) choice. It better describes the relationship between parties and voters in changing political environment (related to emergence of catch-all parties and the de-alignment process) where traditional cleavages and stable party identification are no longer useful (Knutsen Citation2007, Deegan-Krause Citation2007).

The need for a new approach is of particular importance in case of Poland, where neither party identification nor rational choice theory enabled a satisfactory explanation of the relationship between parties and voters (Markowski Citation2013). The existence of party identification in post-communist democracies is particularly questionable due to unfavorable systemic conditions (weak civil society and instable party system, especially in the very first years after transition) and impossibility to satisfy the condition of its transgenerational transmission (Tucker Citation2001, Vlachová Citation2001; Tworzecki Citation2003; Holmberg Citation2007).

The competitive theory of rational based party identification created by Fiorina (Citation1981), according to which the support for the party is determined by evaluation of previous party performance could better explain vote choice in Poland (Rudi Citation2006; Markowski Citation2013). However, the instrumental model of party identification requires voters to be fully informed about parties, politicians, manifestos, etc. Research shows that people are not very interested in politics, and they do not collect political information in a systematic and unbiased way (Zaller Citation1992, Jasiewicz et al. 2014, Prior Citation2018). These negatively influence the overall evaluation of party performance and impair the explanatory power of the Fiorinian model. The political brand approach overcomes these deficiencies and better explains the link between parties and their adherents in terms of consumer-brand relationship (for a review see: Nielsen Citation2017; Farhan and Ahmad Citation2015).

Even though there are various theoretical arguments for application of this concept in Poland (related to the predominance of catch-all parties, low interest in politics and high electoral volatility), studies of party brands in Poland are scarce (Holewa and Gorbaniuk 2007; Krzyszych and Gorbaniuk Citation2011; Turska-Kawa Citation2013; Cwalina, Falkowski Citation2015; Cwalina and Drzewiecka Citation2022).

In the present paper we study this phenomenon, using the brand personality approach, which focuses on consumer’s identity and emotional needs, according to which voter chooses a party which best resonates with an expression of the self he wishes to demonstrate (Street Citation2003). To examine the personalities of political brands, we refer to the concept of archetypes – categories based on symbolism which people assign to brands (Hartwell and Chen Citation2012). Archetypes are a known marketing research tool which enables to study emotions and subconscious motivations that accompany all people’s choices. Vote choice, similarly, to all consumers’ decisions, is driven not only by conscious, rational calculation of benefits, but also by emotions and unconscious motives (Campbell et al. Citation1960, Staiger et al Citation2010, Demertzis 2013). Archetypes that provide such knowledge not only allow better understanding of mechanisms behind the choice made at the ballot, but also enable adjusting the political offer of parties to voter’s hidden needs and provide them a competitive advantage on the political market. Although archetypes are well described and broadly used in branding research, they have not been analyzed in political context. The present paper is the first attempt to analyze archetypes of political parties.

Using mixed methodology and marketing tools and techniques, we verify which what personality characteristics and dimensions (archetypes) do voters use to describe Polish political parties and what needs and emotions resulting from the archetypes accompany party choice. As a result, we receive the portrait of political parties and their voters going beyond the traditional comparison of party manifestos, providing some insight into voter’s subconscious emotions and motivations. The results provide a broader picture of Polish political scene and enrich our knowledge on the electoral decision-making process.

Literature review

Political branding

The central element of political brand approach – the political brand – is defined as an associative network of interconnected political information and attitudes, composed of experiences, feelings, images, issues, sentiments, or symbols, that reflect the general sentiment surrounding various parties (Smith Citation2005). The networks are composed of pieces of information encountered by voters in their daily lives and stored in a memory as a set of nodes and links which may be activated snowballing once a stimulus (e.g. brand name) appears (Anderson Citation1983). Voters create associative networks using bits and pieces of information based on public sentiment without particular focus and order (Nielsen and Larsen Citation2014, 157).

Evaluation of political brands depends on information about parties people collect in everyday lives (deliberately or accidentally) from all possible sources (Schneider Citation2004; Henneberg and Chen 2007; Davies and Mian Citation2010; Smith and French Citation2011; Vössing Citation2021). The approach does not require neither active and systematic collection of information nor sophistication in its processing (Smith and French Citation2011). Political brand approach is more in line with the way people get informed about politics in a real world and better reflects the quality of political information people acquire (Delli Carpini and Keeter Citation1996; Prior Citation2018; Knobloch-Westerwick et al. Citation2020; Vössing Citation2021, Kuklinski et al. Citation2000).

Also, political brand approach provides a theoretical framework which better explains party-voter relationship in changing political context. The rapid rise of popularity of mass media (internet included) reshaped relationship between parties and voters and changed patterns of political behavior. Better educated and informed voters became more likely to make rational decisions based on actual content of policies and performance (Thomassen Citation2005). This led to higher volatility and growing popularity of emerging parties. Political branding does not require that voters are always loyal to one party, they can choose a party which is the most attractive for them at the moment (Aaker Citation1991; Kapferer Citation2004; Schneider Citation2004; French and Smith Citation2008; Smith and French Citation2009). Multiple sources and content of information implicate weaker stability of brand voters (in comparison to party identifiers), who may switch from voting for the party once it departs from its usual image (loses credibility or behaves in unexpected way - Aaker, Fournier, and Brasel Citation2004). The switch is possible even if party policy remains stable, as the change of support for a party may also be a result of changing public sentiments, or a desire for change, caused by curiosity, boredom, or disappointment with party performance (Newman Bruce Citation1999).

Empirical study on the Brand relationship between parties-voters

The popularity of the political brand approach effected in proliferation of empirical studies (for review, see Nielsen Citation2017, Farhan and Ahmad Citation2015). Despite the common denominator being the political brand, the researchers use multiple theories, conceptual frameworks, and methodologies. In the present paper we refer to Sigge Nielsen’s (Citation2017) typology of six conceptual frameworks used by researchers based on the understanding of the voter and his role in the political brand construction.

Three first approaches mentioned by Nielsen are consistent with political science knowledge on the party-voter relationship. They consider voters passive subjects of party treatments, that provide their support based on functional needs the party meets („ I vote for this party because it gives me…”). According to the community approach (equivalent to the Michigan party identification approach) voters’ support is derived from the sense of belonging to a community or tribe, which constitutes the meaning-making structure through which these voters comprehend politics (Nielsen Citation2017,14). The relational approach assumes voters support parties they feel related to (Needham Citation2005, Nielsen Citation2017). The relationship, like interhuman relationships, such as love, friendship, or acquaintance, can be based on emotional as well as rational grounds (which makes the approach close to expressive or instrumental model of party identification).

The economic political brand approach, derived from economic rational voter theory well recognized in the political science literature (Downs Citation1957) explains party-voter relationship in terms of transactional interaction: at the ballot voter chooses the party that best fits his current needs (Phil Harris and Lock Citation2001, Nielsen Citation2017).

The very few political science qualitative studies of the meaning of party-voter relationship confirm that voters’ attachment to parties is of either transactional (this party has the best manifesto/it will bring me biggest benefits) or habitual nature (I always vote for this party), some voters support party because of relational attachment (I like this party - Mayer 2019). These explanations are consistent with the Michigan party identification approach and rational choice-based approaches (such as the Fiorinian model) with all their merits and limits discussed above.

The voter-centric, cultural and brand personality frameworks focus more on identity needs (If I vote for this party, I would be perceived as…) and emotional needs (Voting for this party I feel…). They claim it is a voter who endows emotional meaning to a brand either using the cognitive and affective map of politics formed of from pieces of information encountered in everyday life (Campbell et al. Citation1967; French and Smith Citation2008; Smith and French Citation2011) or interpreting narratives in society (Nielsen Citation2017). Voter chooses a party which best resonates with an expression of the self they he to demonstrate (Street Citation2003). This requires the voter to understand the symbolic and emotional benefits support for party brings about. The brand personality approach is the most consistent with the archetype approach we apply in the present paper.

Brand personality approach

The brand personality approach assumes people perceive brands as non-human entities and attribute to them a whole range of human traits, emotions, or intentions (Aaker Citation1997). The approach is widely used in marketing research, as it provides better insight into the consumers’ brand perception enabling the recognition of emotions that the brand evokes instead of technical characteristics of the product (Patterson, Khogeer, and Hodgson Citation2013). Also, it enables a consumer to express his own identity through the use of a brand (Aaker Citation1997).

The concept of brand personality quickly spread over other disciplines, political marketing included. Political brand personality studies focus on the human-like features voters ascribe to parties (Schneider Citation2004; Voeth and Herbst Citation2008; Smith Citation2009; Guzmán and Sierra Citation2009; Rutter, Hanretty, and Lettice Citation2018). The approach enables a deeper understanding of the party-voter relationship as it provides an insight into voters’ emotional and identity needs, providing a better understanding of the motivations behind party support.

The perception of parties as human beings is related to all advantages of the approach. It makes the brand more salient and thus easier to recognize and remember, which is particularly important in multiparty settings (Turska-Kawa Citation2013). It enables the formation of a strong and durable relationship between party and voter (Smith Citation2009). It serves as an informational shortcut, lowering the costs of gathering political information, and making a choice (Needham Citation2005), and reducing a perceived risk of voting for a wrong party (Smith Citation2009).

For a long time, the brand personality approach was considered uncontroversial (French and Smith Citation2008; Rutter et al. Citation2018). Recently it is being criticized for the lack of universality, conceptual precision, questionable assumptions on generalizability, and the problem of anthropomorphization (for a detailed critique see: Oklevik et al. Citation2020). This leaves a space for a new framework that would enable comprehensive analysis of how voters perceive the party brands (Guzmán and Sierra Citation2009; Schneider Citation2004; Smith Citation2001; de Chernatony Citation2007; Smith and French Citation2011; Pich and Armannsdottir Citation2015). The present paper is an attempt to fulfill this gap.

The research aims to answer four basic questions:

Q1: What personality characteristics do voters use to describe Polish political parties?

Q2: What are the dimensions of personality traits (archetypes) attributed to Polish political parties?

Q3: What needs and emotions resulting from the archetypes accompany party choice?

To answer the above questions, we adjust and apply the brand archetype framework which organizes associations people have with political parties, related inter alia to personality traits, into arranged categories, enabling drawing in-depth conclusions.

The interplay between Brand archetype framework and Brand personality

The identification of emotional and identity needs is not easy, especially when it comes to more complex matters, such as politics (see the debate related to rational voter – Downs 1957; Simon Citation1990, Citation1991). It resulted very hard to explore them with traditional research tools, such as surveys. That is why researchers look for new techniques to deal with these difficulties. One of the approaches refers to its archetypical roots.

Archetypes are defined as “collective unconscious, deeply embedded personality patterns that resonate within us and serve to organize and give direction to human thought and action” (Jung et al. Citation1954, 77). They are universal yet the culture may influence their shape and importance. Fairytales and myths all around the world are based on the same motifs: the warrior, the rebel, the ruler, the sage, the jester, the lover, although the forms of their expression can be completely different (one can fight against the dragon, the witch, terrorists, demonized ethnic minorities or opposition).

It was quickly recognized that identification of values related to archetypes and entering them into the brand’s DNA is a key to success (Plummer Citation1984, Aaker Citation1997, Kotler and Keller Citation2012). Use of archetypes enables marketers to understand emotions that shape consumers’ needs and brand image (Hartwell and Chen Citation2012). The right brand personality pattern, together with consequent marketing strategy (logo, colors, actions, story etc.) act as a magnet for value-sensitive consumers. The brand becomes easily identifiable, credible, and attractive. At the same time, the knowledge of values and needs related to each archetype provides quick and easy explanation of people’s behaviors, beliefs, attitudes.

We believe the same is true for political parties: anchoring the party brand to an iconic image should make its symbolism (and therefore voters’ needs and party image) easier to identify. Despite many advantages the archetypes framework has not been applied to party-voter relationship analysis. It was used by party experts as a diagnostic tool to recognize voter’s needs and motivations, as well as party distinguishing features. Less often they served as a guide to consciously shape party message related to the question about its role in citizens’ lives.

We believe that archetypes may be a useful tool for researchers to analyze and explain political preferences and vote choice. The key advantage of archetypes, which makes them fit to political context, is their universality. Archetypes appeal to easily recognizable feelings and behaviors, which are accessible to everyone, no matter the level of sophistication. Due to the universal message, they enable individuals to act in emotional, unobvious situations where one misses complete information indispensable to make a rational decision (Staniszewski Citation2018). This description perfectly fits the political situation and choice of preferred party.

NeedScope archetypes framework

In the present study we use the NeedScope archetypes framework based on Heylen’s model of motivations and needs inspired by the works of Gustaw Carl Jung (Dirk, Riedl Citation2004, Karczmarczuk, Forycka-Zawadka Citation2021). It assumes the existence of a universal set of human motivations applicable to all areas of life, which can be illustrated with a two-dimensional model, where one-dimension measures interactions with people (it extends from a need for a status to a need to belong), and the second dimension captures external relations (from expression to control – Dirk, Riedl Citation2004). The motivations are expressed using the archetypes which are related to personality attributes (Munteanu et al. Citation2010, Bechter et al. Citation2016).

The research on brands usually uses the Jungian archetypes framework which identifies the 12 core archetypes: innocent, sage, explorer, outlaw, magician, hero, lover, jester, everyman, caregiver, ruler, and creator, which represent basic human motivations (Stevens Citation2006). NeedScope groups archetypes by the similar motivations they express in a different way, creating six sub-archetypes used in analyses ().

Table 1. NeedScope archetypal families.

Although NeedScope has not been used for political brand analysis, its applicability to measure the drivers of social and political attitudes and decisions seems unquestionable. The present paper is the first attempt to apply this marketing model to analyze political choices and party brands. Using the NeedScope tool we verify which archetypes are related to Polish political scene, we map the values people ascribe to them, and we assign Polish political parties to these archetypes.

Methodology

To answer our research questions, we use mixed methods approach combining qualitative (focus group interviews) and quantitative (survey) approach. Use of mixed methodology provided better quality of data (we avoided subjective choice of survey items that would not fit the categories real people use to think and talk about parties) and ensured breadth and depth of understanding of the party-voter relationship. It also enabled verification of the generalizability of our results, in line with the advantages of the triangulation of methods that have been long known and well described in the literature in social sciences (Tashakkori and Teddie Citation2003, Teddlie and Tashakkori Citation2009). The above-described advantages indicate a need for the use of more mixed methods research in political marketing as the discipline is dominated by single-based approach, with quantitative studies as the most common source of data (the qualitative research, although present is much less frequent).

To reach beyond simple survey answers, we applied projective techniques in both qualitative and quantitative studies. Traditional research methods and tools bring often biased results (just to mention the overreporting or desirability bias typical for abstract questions and declarative survey measures). This made researchers move toward more subtle approaches based on behavioral psychology and economy. Projective techniques have become one of the most successful methods in many research fields, as they enable reaching the unconscious world of people’s opinions, attitudes and decisions which cannot be secured through direct questioning (Haire Citation1950, Kotler and Keller Citation2012, for brand research see for example: Hofstede et al. Citation2007; Pich and Armannsdottir Citation2015; Spry and Pich Citation2021).

Qualitative study

The first part of the study consisted of the process of mapping associations with seven political parties. The data was collected through focus group interviews with partisans of six parties: Law and Justice, Civic Platform, Polish Peasants’ Party, Modern, Kukiz’15, Democratic Left Alliance and Together. In total, six two-hour interviews were conducted, each with a group of six people with homogeneous political preferences.

Homogeneous focus groups were designed to prevent emotional and non-informative disputes between political adversaries. Such selection may trigger desirability bias among the participants. To avoid this, we carefully selected contestants using not only their socio-demographic characteristics (see the appendix), but also their psychological predispositions to have open and outspoken individuals with moderate attitude toward political parties. Moreover, the interview scenario was complemented by two projective techniques (described below), which take respondents out of the current political and social context, reducing the probability of social desirability bias and providing better insight into peoples’ justifications of party preferences (Fisher Citation1993; Neeley and Cronley Citation2004).

The projective approach that asks respondents imagine that a brand is a person has a long tradition in the literature (Zober Citation1956; Kotler and Keller Citation2012; Pich et al. Citation2015; Oklevik Citation2020; Ciąćka Citation2021). The Brand Persona techniqueFootnote1 uses a set of stimulating visual aids to enable the detailed description of the brand image as well as the benefits for different groups of consumers. The same approach enables to retrace each party image extended by elements related to social status of the party and - indirectly - its supporters (their profiles, expectations, etc). The Brand Party techniqueFootnote2 moves the personalized brand to a social setting like a party to reveal the relationships and dependencies between competitive brands (dominant brand, similar brands, different brands, outsider brand, etc. – Ciąćka and Rąbińska Citation2021). This technique provided information related to the images of party leaders and their relationships with their parties not limited to their current activity.

All the interviews were semi structured, conducted according to the same scenario, containing questions about participants’ perception and evaluation of given political party (contrasted with other parties if need be), its leader and key politicians and proposed policies. The questions concerned not only current perception of the party but also its past performance and perspective for future.

The qualitative data were first subjected to open coding procedure (supported by Atlas software) aiming at capturing the topics, opinions and experiences present in the statements of the respondents. Then, as part of the closed coding procedure, the preliminary codes were systematized and classified into various dimensions related to party archetypes. The results were then uses as basis for a survey questionnaire to verify the generalizability of the findings.

Quantitative study

The second part of the research consisted of a CAWI survey on representative adult Internet users’ sample (N = 2005 realized in December 2018). In the study we applied the NeedScope methodology which enabled not only quantitative verification of qualitative results, but also revealed consumer’s archetypical needs and emotions accompanying party choice.

During the key stage of the research process – the Positioner stage – respondents were presented six standardized collagesFootnote3 with people’s faces (different for men and for women) that reflected emotions corresponding to six archetypes discussed above. First respondents were asked to match collages with political parties (Think about [party name]. Which of these people would be most prone to vote for this party?). Next, we asked a range of questions related to what people think about the matched party, what they expect, how they feel about it etc.

The NeedScope methodology is designed to capture motivations and needs that drive people’s choices. Therefore, the model provides brand image perceived by users of the brand. Knowing that political parties enhance not only positive emotions and associations we also created the reversed Positioner stage, asking the opponents of political parties to assign the least preferred brand to the collage. Such provided us party perception by their adherents and opponents.

The results of the quantitative study were used to assign political parties to one of six brand archetypes and to decode hidden needs that voting for a particular party brings about.

Empirical analyses

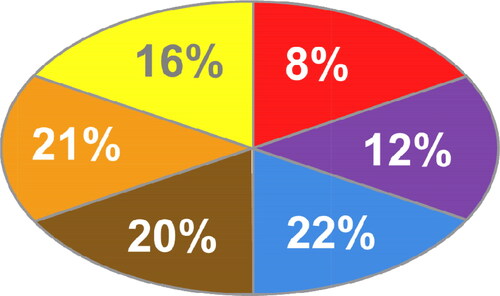

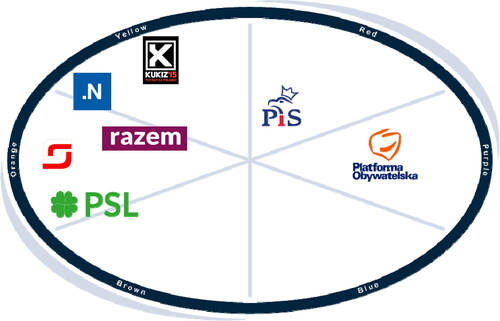

The projective techniques made it possible to measure the needs of the Poles derived from the archetypical images (). There are three types of archetypes at similar level of importance: first, parties associated with consequence, carrying about the future and economic development (the blue archetype chosen by 22% of respondents); second - mild, moderate parties (the orange archetype chosen by 21% of respondents) and third – honest, but also “homey”, “native” parties (the brown archetype chosen by 20% of respondents). The study reveals that choosing a party, people are introvert and group oriented; they request competence, safety, and unity. The extravert (yellow) or individualistic (red and purple) segments had significantly lower results. This may be related to perception of parties as representatives of social groups’ interests, their performance is not perceived throughout personal benefits.

Voters were also asked to describe the party in each segment. Red parties were described as aggressive, competitive, and conflicting. Purple parties are self-confident, strong, and cosmopolitan. Blue parties are future oriented, consequent, they have high political culture, they care about the economic development of the country, the position of Poland in the world. Brown parties are mild, „homey” and honorable. They are close to the people, represent important values and make voters feel safe about their country. Orange parties are mild, voters-oriented and carrying about the position of Poland in the world. Yellow parties are associated with openness, sincerity, and equality.

Next, we linked political parties with archetypes based on the opinions of their partisans () and opponents (). The categorization is based on standard deviations of the party assignments to a given collage.

According to their voters, Law and Justice (PIS), Civic Platform (PO) and Democratic Left Alliance (SLD) supporters choose the party which – in their opinion – will best care for their wellbeing, as well as the good of the country. The Polish Peasant’ Party (PSL) voters perceive their party as honest and responsible. Smaller opposition parties: Modern (Nowoczesna – a liberal party) and Together (Razem – a small left party) are perceived as less serious and spontaneous. Such a perception of these parties can be related to the lesser stake at game: the support for these parties is close to electoral threshold, thus their political significance can be perceived as lower. Kukiz’15 – a rightist party founded by a rock musician – is perceived as brave and dynamic.

The perception of political parties in the eyes of their opponents (those who declared they would never vote for a particular party) is rather consistent with the perception of the partisans in majority of cases (). The biggest significant difference was noted in case of Law and Justice party which is recognized by opponents as aggressive and focused on conflict. In case of the two other parties perceived differently the shift is much less significant: the opponents regard Democratic Left Alliance as moderate, familiar, party and Kukiz’15 is perceived as artistic and not very serious. These divergences can be attributed to high levels of out-group derogation performed by their opponents or different messages these two groups receive from “their” information bubbles.

Another important finding is related to the way partisans would like to be perceived. We asked the indirect question: „What does vote for this party tells us about the personality of these people? What kind of voters are they?”. Support for party is very informative as far as our image is concerned ().

Respondents who identified with the red collage would like to be perceived as full of life, entertaining, brave, and adventurous. Those who chose the purple collage consider themselves as ambitious, energetic, successful. The blue ones are intelligent, thinking, responsible, engaged, ordered, but also careful and prudent. They want to be perceived as rational. The browns are also reasonable and responsible, but also loyal, trustworthy, helpful, and friendly. The latter set of features also characterizes those who belong to orange segment, next to spontaneity and joy, which on the other hand connects them with the yellow segment. The yellows would also like to be perceived as energetic, full of life, joyful and successful.

It’s worth emphasizing that, regardless of the segment, there are two needs that were indicated the most often: everyone wants to be perceived as intelligent and thinking but also reasonable and responsible. These can be considered as generic need of self-expression while making any kind of choice.

When we compare the parties and voters’ perception it results that the former characteristics were less salient. This can be attributed to the fact that the party-voter relationship is archetypical, based on emotional attachment rather than rational evaluation of election promises or a party manifesto.

Discussion

Despite plethora of empirical papers studying party brands, researchers point to the need to elaborate a broader framework that would enable better understanding of how voters perceive political parties. The existing marketing inspired frameworks based on party image, personality or equity analysis do not provide satisfactory answers (see Farhan and Ahmad Citation2015). The brand archetypes framework seems to be a solution, which addresses several problems related to analysis of party-voter relationship in contemporary world where party identification, running tally of experience with the party or rational choice models resulted insufficient.

The traditional political science approaches do not allow to fully explain voters’ attitude toward parties. Party identification fails to explain volatility and propensity to support newly emerged parties. Rational choice-based models’ explanatory power is week because of voters’ deficiencies, such as political apathy, incomplete information, and insufficient sophistication, that disable reliable evaluation of political parties. The archetypes approach not only deals with the above stated problems, but also enables researchers to go beyond functional needs voters ascribe to parties and discover their hidden motivations of party support.

The archetype framework enabled us to reach latent needs of voters, providing better understanding of the matter and demonstrating that the needs parties are expected to meet go beyond the party manifestos (or pork-barreling) and party campaign image. We diagnosed the identity and emotional needs Polish voters seek to meet supporting a party are related to protection and care, warmth, and expertise. The Law and Justice best meets these needs according to its adherents. However, the results juxtaposed with party preferences let us hypothesize that not all voters support parties that best meet their most important needs. Strategic voting (supporting a bigger party with higher chance for victory) could provide explanation to this puzzle.

Despite the results of preliminary analysis that led us to conclusion that voters not necessarily support parties that best meet their most important needs, the more detailed study reveals the image of voters belonging to each archetype and the image of the party they support are consistent. The analyses reveal the same set of values ascribed to parties’ and voters’ images. The Law and Justice (brown archetype) voters value the most reliability, trustworthiness, consequence and together with the Left Democratic Alliance supporters (blue archetype) concern for people’s wellbeing (). The Civic Platform voters (purple archetype) value success and economic wellbeing. The Modern adherents (orange archetype) value moderation and loyalty. For the Together followers (yellow archetype) the sincerity is most appreciated. Finally, Kukiz ‘15 voters (red archetype) prize bravery and dynamism.

Table 2. Image of voters according to archetypes.

The most interesting finding demonstrates that despite the needs typical for each segment there is one universal need of being perceived as intelligent and rational, shared by all voters. This finding is to some extent in line with the findings related to the rationalization process, according to which people make irrational, emotional decisions while voting and post factum justify their choices with logical, plausible reasons (Achen and Bartels Citation2016).

Our findings have several theoretical implications. We managed to corroborate our assumption that political brand – party – is perceived by consumers-voters in the same way as market brands. What’s the most important, not only the brand image matters. We managed to confirm that party brand, similarly to other brands has its own functional, emotional and identity benefits, they have own personality and – last but not least – the user (voter). The voting decision making process can be thus explained from the consumer’s point of view, however it should be kept in mind that party image is much less stable than consumer brands, and it strongly depends on the leader’s and key politicians’ image and actions. A new party leader can completely change the perception of the party (and lead to its success or failure).

There is no doubt the knowledge we acquired is useful for student of party-voter relationship. Also, it can be particularly useful for political marketers, as archetypes constitute a very powerful political marketing tool which facilitates building strong and positive relation between party and its voters. The archetype ascribed to a party (and its meaning) enable relevant brand management, based not only on manifesto propositions, but also on the values, emotions, and subconscious needs. The relationship with party-brand can become more profound with its use.

What is more, the archetypes enable finding the right niche in the market – the voters, and the creation of coherent image and running proper narrative emphasizing the right issues and policies – all concordant with the archetype makes it easier for parties to reach voters (people put more attention when emotions and important values are engaged). Building a distinctive image of the brand that is positive, strong, and credible leads to greater party salience and enables building positive relationship between party and voter, which in turn affects not only momentaneous electoral support for the party, but also building durable relationship beyond electoral context (French and Smith Citation2008; Smith and French Citation2009; Nielsen and Larsen Citation2014).

Our research revealed some areas for further study. First and foremost, in-depth study of archetypes is needed. The present paper is a verification of existing models, revealing voters’ archetypical expectations and needs voters try to meet throughout voting and supporting a party. Archetypes are proxies that enable to describe consumer’s (voters’) motivations. A more detailed analysis related to the voters’ understanding of archetypical needs would enable better comprehension of the phenomenon under study.

Second, the analysis of archetypes (and their content) for various sociodemographic groups is required. The previous research on various aspects of party-voters relationship indicate differences at least between representatives of various social and demographic strata. The futher analysis on how these differences can be applicable to archetypical needs, which are defined as universal.

Finally, the relationship between perception of political brand archetypes and vote choice requires further examination. The few existing studies of the relationship between political brand and vote choice confirm that strength, favorability, and uniqueness of the brand influence voters’ decision on how to cast the ballot (Woon and Pope 2008; Nielsen and Larsen Citation2014, Farrag and Shamma Citation2014; Cwalina, Falkowski Citation2015; Schofield and Reeves Citation2015). To our best knowledge there is no study that would analyze voters’ expectations and needs related to political parties and their effect on vote choice. The attempt to explain benefits voters have (or expect) from voting going beyond manifestos and electoral campaign promises, would certainly shed new light on the bonds between parties and voters and the behavior these bonds cause.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The instruction for Brand Persona task was: And now let’s try to use our imagination: imagine the [name of political party] is a human. Where does he live? In what surroundings? In what kind of housing? What kind of car does he drive? What does he wear? What does he eat? What is his hobby? How does he spend free time? Does he practice any sport? What kind of music does he listens to? What does he watch (film? Tv programs?) How does he spend holidays? Does he have any pet?

2 The instruction for Brand Party task was: Imagine that party leaders take part in international conference. Tell me please how they behave during the debate, what is their speech about, who is their audience, what is the relationship between various leaders, who they talk to. And now imagine that there is a party after the conference – how do leaders behave during the party? what do they eat, drink? Who they talk to? how they are dressed? Etc.

3 The collage sets were elaborated for different regions and quantitatively tested against standardized batteries of attributes.

References

- Aaker, D. A. 1991. Managing Brand Equity. New York: The Free Press.

- Aaker, J. 1997. “Dimensions of Brand Personality.” Journal of Marketing Research 34 (3): 347–57. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/002224379703400304.

- Aaker, J.L., S. Fournier, and S.A. Brasel. 2004. “When Good Brands Do Bad.” Journal of Consumer Research 31 (1):1–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/383419.

- Achen, Ch, and L. Bartels. 2016. Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Anderson, J. R. 1983. The Architecture of Cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bechter, C., G. Farinelli, R. Daniel, and M. Frey. 2016. “Advertising Between Archetype and Brand Personality.” Administrative Sciences 6 (2):5. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci6020005.

- Campbell, A., P. E. Converse, W. E. Miller, and D. E. Stokes. 1960. The American Voter. New York: John Wiley.

- Campbell, A., P. E. Converse, W. E. Miller, and D. E. Stokes. 1967. Elections and the Political Order. New York: John Wiley.

- Ciąćka, P., and B. Rąbińska. 2021. “„Badania Jakościowe – Klasyczne Metody FGI Oraz IDI.” in: M. J. Lutostański, A. Łebkowska, M. Protasiuk, Badanie Rynku. Jak Zrozumieć Konsumenta? Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

- Cwalina, W., and M. Drzewiecka. 2022. “How Trust Wins against Criticism: Promise Concept as a Political Branding Tool. Lessons from Polish Politics.” In: Political Branding in Turbulent Times, edited by M. Moufahim, 123–40. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cwalina, W., and A. Falkowski. 2006. Marketing Polityczny. Perspektywa Psychologiczna. Gdańsk: Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne.

- Cwalina, Wojciech, and Andrzej Falkowski. 2015. “Political Branding: Political Candidates Positioning Based on Interobject Associative Affinity Index.” Journal of Political Marketing 14 (1-2):152–74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2014.990842.

- Davies, G., and T. Mian. 2010. “The Reputation of the Party Leader and of the Party Being Led.” European Journal of Marketing 44 (3/4):331–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561011020453.

- Deegan-Krause, K. 2007. New dimensions of political cleavages. In: R. Dalton, H. D. Klingemann (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- de Chernatony, L. 2007. From Brand Vision to Brand Evaluation. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Delli Carpini, M., and S. Keeter. 1996. What Americans Know about Politics and Why It Matters. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Demertzis, N. 2013. Introduction: Theorizing the Emotions-Politics Nexus. In: Demertzis N. (eds) Emotions in Politics. Palgrave Studies in Political Psychology series. Palgrave Macmillan, London. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137025661_1.

- Dirk, F., and P. Riedl. 2004.“Theoretical Foundations of Contemporary Qualitative Market Research [63 paragraphs].” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 5(2)): Art. 30, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0402307.

- Downs, A. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper and Row.

- Falkowki, A., and W. Cwalina. 2015. “Political Branding: Political Candidates Positioning Based on Inter-Object Associative Affinity Index.” Journal of Political Marketing 14(1): 152–74.

- Farhan, A., and A. Ahmad. 2015. “A Review of Political Branding Research.” Global Journal of Business and Social Science Review 4:340–8.

- Farrag, D. A. R., and H. Shamma. 2014. “Factors Influencing Voting Intentions for Egyptian Parliament Elections.” 2011. “Journal of Islamic Marketing 5 (1): 49–70. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-01-2013-0003.

- Fiorina, M. P. 1981. Retrospective Voting in American National Elections. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Fisher, R. 1993. “Social Desirability Bias and the Validity of Indirect Questioning.” Journal of Consumer Research 20 (2): 303–15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/209351.

- French, A., and I. G. Smith. 2008. “Measuring Political Brand Equity: A Consumer Approach.” Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Political Marketing, Manchester Business School, March.

- Guzmán, F., and V. Sierra. 2009. “A Political Candidate’s Brand Image Scale: Are Political Candidates Brands?” Journal of Brand Management 17 (3): 207–17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2009.19.

- Haire, M. 1950. “Projective Techniques in Marketing Research.” Journal of Marketing 14 (5): 649–56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/002224295001400501.

- Hartwell, M., and J. Chen. 2012. Archetypes in Branding: A Toolkit for Creatives and Strategists. New York: HOW Books; Spi edition

- Hofstede, A., J. van Hoof, N. Walenberg, and M. de Jong. 2007. “Projective Techniques for Brand Image Research: Two Personification‐Based Methods Explored.” Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal 10 (3): 300–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/13522750710754326.

- Holewa, A., O. Gorbaniuk, 2009. Taksonomia wolnych skojarzeń z partiami politycznymi w czasie wyborów parlamentarnych w 2007 roku: badania studentów lubelskich uczelni. In A. Oleszkowicz, P. Dybek, (ed.), Psychologia ilości, psychologia jakości. Uzupełniające się skojarzenia, Wrocław: Atut, ss. 71–85.

- Holmberg, S. 2007. “Partisanship Reconsidered.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior, edited by R. Dalton, H.-D. Klingemann, 557–70. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jasiewicz-Betkiewicz, A., M. Cześnik, M. Kotnarowski, M. Wenzel, and M. Żerkowska-Balas. 2017. Co tam Panie w polityce? Struktura potocznej wiedzy politycznej Polaków. Kultura I Społeczeństwo 61 (4):27–47. doi: https://doi.org/10.35757/KiS.2017.61.4.2.

- Jung, C. G., 1954. “Psychological Aspects of the Mother Archetype.” In The Collected Works of C, G. Jung, edited by H. Read, M. Fordham, and G. Adler, Vol. 9, 75–110. London: Routledge.

- Kapferer, J. N. 2004. The New Strategic Brand Management: Creating and Sustaining Brand Equity Long Term. London: Kogan Page.

- Karczmarczuk, A., and A. Forycka-Zawadka. 2021. “Badania Służące Segmentacji Rynku, Czyli Jak Wyróżnić i Opisać Swoją Grupę Docelową.” In: Badanie Rynku. Jak Zrozumieć Konsumenta?, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, edited by M. J. Lutostański, A. Łebkowska, and M. Protasiuk, Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

- Kotler, P., and K. L. Keller. 2012. Marketing Management. Harlow: Pearson Education.

- Knobloch-Westerwick, S., C. Mothes, and N. Polavin. 2020. “Confirmation Bias, Ingroup Bias, and Negativity Bias in Selective Exposure to Political Information.” Communication Research, 47(1): 104–124. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650217719596.

- Knutsen, O. 2007. The decline of social class?. In: R. Dalton, H.D. Klingemann, (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Krzyszycha, G., and O. Gorbaniuk. 2011. “Zbieżność percepcji siebie i “osobowości” partii politycznej a preferencje polityczne wśród studentów, [w:] I. Hofman (red.), Marketing polityczny.” Teoria i praktyka, Lublin: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej.

- Kuklinski, J., P. Quirk, J. Jerit, D. Schwieder, and R. Rich. 2000. “Misinformation and the Currency of Democratic Citizenship.” The Journal of Politics 62 (3):790–816. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-3816.00033.

- Le Duc, L. 1981. “The Dynamic Properties of Party Identification: A Four-Nation Comparison.” European Journal of Political Research 9 (3):257–68.

- Markowski, R. 2013. “„Identyfikacja Partyjna w Nowych Demokracjach: przypadek Europy Środkowo-Wschodniej.” Studia Polityczne 32:45–73.

- Munteanu, A., I. Costea, R. Palos, and A. Jinaru. 2010. “Entering in the Essences of Personality – Studies over Archetypes.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 5:2272–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.448.

- Needham, C. 2005. “Brand Leaders: Clinton, Blair and the Limitations of the Permanent Campaign.” Political Studies 53 (2): 343–61. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2005.00532.x.

- Needham, C. 2006. “Brands and Political Loyalty.” Journal of Brand Management 13 (3):178–87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2540260.

- Neeley, S.M., and M. Cronley. 2004. “When Research Participants Don’t Tell It like It is: Pinpointing the Effects of Social Desirability Bias Using Self Vs. Indirect-Questioning.” NA - Advances in Consumer Research 31:432–3.

- Newman Bruce, I. 1999. The Mass Marketing of Politics: Democracy in an Age of Manufactured Images. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Nielsen, S. W. 2017. “On Political Brands: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Journal of Political Marketing 16 (2):118–146. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2014.959694.

- Nielsen, S. W., and M. V. Larsen. 2014. “Party Brands and Voting.” Electoral Studies 33:153–65.

- O’Shaughnessy, Nicholas J., and Stephan C. Henneberg. 2007. “The Selling of the President 2004: A Marketing Perspective.” Journal of Public Affairs 7(3): 249–68. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.265.

- Oklevik, O., M. Supphellen, and N. Maehle. 2020. “Time to Retire the Concept of Brand Personality? Extending the Critique and Introducing a New Framework.” Journal of Consumer Behaviour 19 (3):211–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1805.

- Patterson, A., Y. Khogeer, and J. Hodgson. 2013. “How to Create an Influential Anthropomorphic Mascot: Literary Musings on Marketing.” Make-Believe and Meerkats 29 (1/2): 69–85.

- Phil, H. and L. Andrew. 2001. “Establishing the Charles Kennedy Brand: A Strategy for an Election the Result of which is a Foregone Conclusion.” Journal of Marketing Management 17 (9-10):943–956. doi: https://doi.org/10.1362/026725701323366683.

- Pich, C., and G. Armannsdottir. 2018. “Political Brand Image: An Investigation into the Operationalisation of the External Orientation of David Cameron’s Conservative Brand.” Journal of Marketing Communications 24 (1):35–52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2015.1072577.

- Plummer, J.T. 1984. “How Personality Makes a Difference.” Journal of Advertising Research 24:27–31.

- Prior, M. 2018. Hooked: How Politics Captures People’s Interest. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rudi, T. 2006. “What Kind of Party Identification Does Exist in Emerging Democracies in Central and Eastern Europe?.” Paper Presented at the ECPR Joint Sessions of Workshops. 2006. Nicosia: Cyprus.

- Rutter, R.,. C. Hanretty, and F. Lettice. 2018. “Political Brands: can Parties Be Distinguished by Their Online Brand Personality?” Journal of Political Marketing 17 (3):193–212. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15377857.2015.1022631.

- Scammell, M. 2007. “Political Brands and Consumer Citizens: The Rebranding of Tony Blair.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 611 (1):176–92. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716206299149.

- Schneider, H. 2004. “Branding in Politics – Manifestations, Relevance and Identity-Oriented Management.” Journal of Political Marketing 3 (3):41–67. doi: https://doi.org/10.1300/J199v03n03_03.

- Schofield, P., and P. Reeves. 2015. “Does the Factor Theory of Satisfaction Explain Political Voting Behaviour ?” European Journal of Marketing 49 (5/6): 968–6. (doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-08-2014-0524.

- Simon, H. 1990. “A mechanism for social selection and successful altruism” Science 250: 1665–1668.

- Simon, H. 1991. “Bounded Rationality and Organizational Learning” Organization Science 2 (1): 125–134.

- Smith, G. 2001. “The 2001 General Election: Factors Influencing the Brand Image of Political Parties and Their Leaders.” Journal of Marketing Management 17 (9-10):989–73. /10):doi: https://doi.org/10.1362/026725701323366719.

- Smith, G. 2005. “Politically Significant Events and Their Effect on the Image of Political Parties: A Conceptual Approach.” Journal of Political Marketing 4 (2/3):91–114. doi: https://doi.org/10.1300/J199v04n02_05.

- Smith, G. 2009. “Conceptualizing and Testing Brand Personality in British Politics.” Journal of Political Marketing 8 (3):209–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15377850903044858.

- Smith, G., and A. French. 2009. “The Political Brand: A Consumer Perspective.” Marketing Theory 9 (2): 209–26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593109103068.

- Smith, G., and A. French. 2011. “Measuring the Changes to Leader Brand Associations during the 2010 Election Campaign.” Journal of Marketing Management 27 (7-8): 718–35. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2011.587825.

- Spry, L., and C. Pich. 2021. “Enhancing data collection methods with qualitative projective techniques in the exploration of a university’s brand identity and brand image.” International Journal of Market Research 63 (2):177–200. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1470785320943045.

- Staiger, J., A. Cvetkovich and A. Reynolds. (Eds.). 2010. “Political Emotions (1st ed.).” Routledge. doi: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203849538.

- Staniszewski, M. 2018. Archetypy w Marketingu. ICAN Institute. Available online: https://www.ican.pl/b/archetypy-w-marketingu/P186t4PAC

- Stevens, A. 2006. “The Archetypes.” In: The Handbook of Jungian Psychology, edited by. R. Papadopoulos, New York: Routledge.

- Street, J. 2003. “The Celebrity Politician: Political Style and Popular Culture.” In Media and the Restyling of Politics, edited by J. Corner and D. Pels, 85–99. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Tashakkori, A., and C. Teddlie. (Eds.). 2003. Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Teddlie, C., and A. Tashakkori. 2009. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research. Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Thomassen, J. ( 2005. ed.). “The European Voter.” A Comparative Study of Modern Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tucker, J. 2001. “Economic Conditions and the Vote for Incumbent Parties in Russia.” Post-Soviet Affairs, 17 (4): 309–31. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2001.10641506.

- Turska-Kawa, A. 2013. “„Marka Idealnej Partii Politycznej w Opinii Wyborców o Różnych Preferencjach Ideologicznych i Partyjnych.” Political Preferences 5:29–47.

- Tworzecki, H. 2003. “Learning to Choose.” Electoral Politics in East-Central Europe. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Vlachová, K. 2001. “Party Identification in the Czech Republic: Inter-Party Hostility and Party Preference.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 34 (4): 479–99. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-067X(01)00015-0.

- Voeth, M., and U. Herbst. 2008. “The Concept of Brand Personality as an Instrument for Advanced Non-Profit Branding–an Empirical Analysis.” Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing 19 (1):71–97. doi: https://doi.org/10.1300/J054v19n01_04.

- Vössing, K. 2021. “The Quality of Political Information.” Political Studies Review 19(4): 574–90. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929920917618.

- White, J., and L. de Chernatony. 2002. “New Labour: A Study of the Creation, Development and Demise of a Political Brand.” Journal of Political Marketing 1(2/3): 45–52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1300/J199v01n02_04.

- Zaller, J. 1992. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zober, M. 1956. “Some Projective Techniques Applied to Marketing Research.” Journal of Marketing 20 (3): 262–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/002224295602000306.

Appendix 1.

FGI sample selection

The Focus groups interviews were held by Kantar research agency.

Time: 29-31 January 2018.

Duration: 2 hours per interview.

Moderation: two moderators per session, with experience in social-political and brand studies.

Localization (chosen according to official party support in 2015 parliamentary elections and socio-demographic traits of each party electorate):

– Civic Platform (PO) – Warsaw

– Modern (Nowoczesna) – Warsaw

– Law and Justice (PIS)- Siedlce

– Polish Peasants’ Party (PSL) – inhabitants of villages near Siedlce

– Democratic Left Alliance (SLD) - Łódź

– Kukiz ‘15 – Łódź

Each Focus group answered questions about three parties: the closest (a party they voted for), second closest and the most distant (most similar and most distant to the closest one, selected based on PNES 2015 results of left-right and issue scales –see table below).