Abstract

Permanent campaigning has been widely examined in electoral scholarship. However, few studies have looked at paid online political advertising or compared the degree to which different types of actor engage in permanent campaigns. To fill these gaps, we present an in-depth study of online political advertising within the UK to provide new insight into the dynamics of the permanent campaign. Analyzing data from the Facebook advertising archive between 2018 and 2021, we reveal how Facebook advertising is utilized by parties, party leaders and nonparty campaign groups during electoral and non-electoral periods. We find that parties, political leaders and satellite campaign groups focus their activity primarily on general election periods and often invest little outside these periods. In contrast, nonpartizan campaign groups utilize advertising more evenly in electoral and non-electoral periods. Our findings raise questions about the extent to which online political advertising is used for permanent campaigning by different groups.

The idea of the permanent campaign suggests that “political representatives need to pursue actions consistent with election campaigning in non-electoral periods to maintain a positive image among the public and thus enable future electoral successes” (Joathan and Lilleker Citation2020, 2). Developed in the 1970s, this concept has evolved over subsequent decades, with scholars studying the evolving characteristics of campaigning throughout the electoral cycle. Most recently, this idea has been applied to digital campaigning (Gibson Citation2020). Whilst some actors have claimed that “online communication has facilitated the conditions for permanent political debates and campaigns, thus making it difficult to distinguish political communication in non-electoral periods from that in electoral periods” (Council of Europe Citation2022, Preamble), other studies have raised questions about the degree to which digital media are used beyond election campaigns (Larsson Citation2016; Vasko and Trilling Citation2019; Vergeer, Hermans, and Sams Citation2011). This debate has so far focused on the use of particular digital technologies, examining the use of websites and social media profiles within and outside of election campaigns. To date, two important dimensions have been neglected. First, despite the widespread adoption of online political advertising within campaigns (Fowler et al. Citation2021), scholars have not yet examined whether and how online advertising is utilized for permanent campaigning. Second, despite recognition that “online platforms have enabled a wide array of actors with political agendas to take part in political communication and advertising” (Council of Europe Citation2022, Preamble), analysis has focused on the campaign activities of political parties and leaders, overlooking the behavior of nonparty campaign organizations.

To address these gaps, we offer the first empirical study of permanent campaigning via online political advertising. Using computational methods to analyze data from the Facebook political advertising archive in the UK between December 2018 and December 2021, we investigate how the use of online political advertising varies throughout the electoral cycle and by different actors.Footnote1 In total, we collected 668,239 adverts placed by 40,534 unique advertisers from the Facebook Ad Library. Out of this number, we analyzed 129,685 adverts from 74 unique advertisers based on accounts registered with the UK Electoral Commission.

Our analyses show that, first, the use of online political advertising by parties and political leaders is focused on election periods, raising questions about the extent of permanent campaigning activity. Exploring the strategies of different parties and political leaders to interrogate the uniformity of this trend, we find different uses of online advertising in terms of advert frequency and spend, but evidence of only limited investment in online advertising outside the general election period. Second, we investigate the activity of nonparty campaign organizations who registered with the Electoral Commission due to their activity campaigning during election periods. We identify two types of nonparty campaign organizations: satellite campaign groups and nonpartizan campaign groups. We find that satellite campaigners mirror parties’ and leaders’ use of online political advertising, whilst nonpartizan groups use online political advertising more evenly in electoral and non-electoral periods.

In terms of contribution, our analysis raises questions about the degree to which the use of online political advertising is consistent with the notion of permanent campaigning. Spotlighting significant fluctuations in the number of adverts and expenditure across the electoral cycle, we show that parties, political leaders and satellite campaigns often neglect this activity beyond the general election, whilst nonpartizan campaign groups invest more consistently. This raises questions about the utilization of digital media for campaigning, suggesting that offline strategies are not automatically employed online, and that different actors are willing and able to utilize digital communication channels to different degrees.

The article is structured as follows. First, we provide an overview of existing research on permanent campaigning, with a particular focus on studies of digital campaign activity. Identifying two gaps in existing knowledge, we generate hypotheses that guide our analysis. Second, we provide an overview of our methodology, explaining how computational methods inform our analysis. Third, we present an overview of data from the UK, detailing how online political advertising was used by political parties, leaders and nonparty campaign groups within and outside of election campaigns. Finally, we discuss the significance of our findings for conceptions of modern campaigning, arguing there is limited evidence of permanent campaigning in the use of online political advertising, but important variations in the behavior of different actors.

Literature review

The concept of permanent campaigning originated in the United States when political consultant Patrick Caddell advised President-elect Jimmy Carter in 1976 that it was strategically wrong to separate campaigning from governing because “governing with public approval requires a continuing political campaign” (Blumenthal Citation1980, 39). The idea suggests that political actors need to make constant campaign efforts during non-election periods in order to maximize the chance of their future electoral success, shifting their focus “beyond the month-long official campaign to everyday politics between elections” (Norris Citation1997, 117). Activities such as fundraising, polling, advertising, and image-building have therefore come to be seen as permanent aspects of political activity, rather than periodic and electorally-focused undertakings (Doherty Citation2014; Ornstein and Mann Citation2000). The permanent campaign is associated with perpetual campaign activity undertaken with “calculated purpose” (Marland, Giasson, and Esselment Citation2017, 4). Whilst often linked to campaign practices in the US (Marques, Aquino, and Miola Citation2014), this phenomenon has been studied in the contexts of Ecuador (Conaghan and de la Torre Citation2008), Canada (Marland, Giasson, and Esselment Citation2017), Australia (Van Onselen and Errington Citation2007), Poland (Domalewska Citation2018), Greece (Koliastasis Citation2020), Norway and Sweden (Larsson Citation2016), the UK (Diamond Citation2019; Lilleker Citation2015) and elsewhere.

Existing research has primarily focused on traditional campaigning activities that are evident offline, seeking to determine whether permanent campaigning exists and what is indicative of this trend. However, current studies advance slightly different understandings and measures of the permanent campaign. A meta-analysis by Joathan and Lilleker (Citation2020, 5) has shown three different types of indicators to be used within existing research, manifest as a focus on either “capacity building and strategy,” “paid and owned media and […] political communication produced for direct consumption by citizens,” or “earned media which is political communication designed to generate positive media coverage.” Specifically, studies have examined campaign strategies including the constant fundraising of parties, the greater use of negative campaigning, attempts to generate positive media coverage and using travel to target electorally important areas, amongst other factors (Ibid.). Monitoring trends over time and in different media, numerous studies have concluded that politicians and political parties invest in year-round electoral activity and often utilize state resources to support their campaigns both within and beyond American and European contexts (Conaghan and de la Torre Citation2008).

More recently, questions have emerged about the significance of “changes and transformations brought about by the digital revolution” for permanent campaigning (Ceccobelli Citation2018, 124), reflecting a trend within literature to examine the adoption of social media for political purposes (Bimber et al. Citation2015; Elmer, Langlois, and McKelvey Citation2014). To date, studies using publicly available data from Twitter or Facebook Pages (Ceccobelli Citation2018; Larsson Citation2015; Larsson Citation2016; Vasko and Trilling Citation2019; Wen Citation2014) have raised questions about the existence of permanent campaigning. Examining the use of Twitter by EU Parliamentary representatives, for example, Larsson noted the potential for varied practices by different party groups, but overall found “online permanence on Twitter to be rather limited” (2016, 161). Similarly, findings from Vasko and Trilling’s analysis of Twitter use by Members of Congress in the US did “not point to a state of permanent campaigning” (2019, 355), whilst Vergeer, Hermans, and Sams (Citation2011) show that online campaigning activity in elections for the European Parliament is predominantly centered around electoral periods. Indeed, one study of online campaign tools in eighteen countries found that “an ideal-typical application of permanent campaign theory, for which ‘every day is election day,’ does not fit with the empirical reality” (Ceccobelli Citation2018, 136). Instead, it appears that political actors are employing “differing strategies” in their use of digital technologies (Lilleker and Jackson Citation2010).

Two important gaps, however, exist in our understanding. First, in expanding to study campaign trends in the online sphere, existing studies have focused on organic campaign activity, meaning contents shared by online users without payment (Fulgoni Citation2015). Due to the limited availability of data (Bruns Citation2019; Møller and Bechmann Citation2019; Tromble Citation2021), scholars have not historically been able to examine the use of online paid media such as targeted advertising in campaigns. This gap is significant because paid media and online political advertising have rapidly become an important component of political campaigns (Fowler et al. Citation2021). At the UK 2019 general election, political parties and nonparty advertisers spent at least £7.7 million on Facebook and Google advertising (Dommett and Bakir Citation2020, 212). Meanwhile in the United States, the amount of digital political advertising ($1.6 billion) accounted for 19% of total political advertising spend in the 2019–2020 election cycle, compared to a mere 2–3% in the 2015–2016 election cycle (Homonoff Citation2020). Such figures focus, however, on payments made within election periods. Less is known about the extent to which this medium is used during the rest of the year. In drawing on newly available data from the Facebook advertising archive to investigate this topic, we are particularly interested in examining the degree to which variations in campaign activity exist and determining whether paid digital media is used differently to organic digital content. In line with existing findings, and given the financial costs of accessing paid advertising, we hypothesize that political parties and political leaders will concentrate their online political advertising activity on election periods, manifesting as increased numbers of adverts and elevated spending during electoral periods as compared to non-electoral periods. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H1: Political parties and political leaders will place higher numbers of adverts during electoral periods than non-electoral periods.

H2: Political parties and political leaders will elevate spending during electoral periods as opposed to non-electoral periods.

A second gap relates to our understanding of the different actors engaged in permanent campaigning. Existing studies have tended to focus on presidential elections (Ceccobelli Citation2018; Larsson Citation2015; Larsson Citation2016; Wen Citation2014) and particularly on the activities of what Blumenthal (Citation1980) described as “elite political operations.” As a result, political parties and political leaders have been the primary object of analysis (Lilleker Citation2006, 143). However, as Elmer, Langlois, and McKelvey (Citation2012) have argued, digital technology has facilitated the “proliferation of new political actors and communicators” in and around election campaigns, resulting in what Dommett, Kefford, and Power (Citation2021) have described as the “digital ecosystem.” These trends mean a range of other actors are now often engaged in election campaigns that do not stand candidates themselves, a role termed as “non-party campaigners”Footnote2 by the UK Electoral Commission. These actors have gone largely unexplored in studies of permanent campaigning due to a focus on elites. Yet, with growing recognition that digital technology enables “centrifugal diversification,” meaning that it is possible for “more diverse content to be produced; more voices to be heard and more audience members to be reached by such material” (Blumler Citation2016, 25-26), it is increasingly important to understand how these actors behave and take part in online campaigning.

In investigating these organizations, we argue that it is useful to differentiate between different types of nonparty campaigners. First, we identify satellite campaign groups, termed by Dommett and Temple (Citation2018). These are groups which, whilst distinct from a political party or candidate, are engaged in partisan activity – often via support for or opposition to a particular partisan agenda. Evident as Political Action Committees in the US, for example, this type of organization has been shown by electoral scholars to play an important role in campaigns (Smith Citation1995). Second, we identify a type of nonparty campaign group that is active in election periods but is not engaged in partisan activity. We term this category nonpartizan campaign groups. Evident in the form of charities or NGOs, these groups tend to engage in more issue-based and diverse forms of political campaigning, often in the online sphere (Katz-Kimchi and Manosevitch Citation2015). What is presently unclear is whether these two types of nonparty campaign groups engage in permanent campaigning and whether their strategies differ. Focusing first on satellite campaign groups, given the proximity of these actors to official campaigns, we would expect to see similar uses of online political advertising as those exhibited by parties and political leaders in and outside electoral periods. For this reason, we hypothesize:

H3: Satellite campaign groups will place higher numbers of adverts during electoral periods than non-electoral periods.

H4: Satellite campaign groups will elevate spending during electoral periods as opposed to non-electoral periods.

Turning to nonpartizan campaign groups, we would expect that campaigning activity is more or less even across the electoral cycle, as these organizations are not solely focused on electoral objectives. We accordingly hypothesize:

H5: Non-partisan campaign groups will place similar numbers of adverts during electoral periods and non-electoral periods.

H6: Non-partisan campaign groups will devote similar levels of spending within electoral periods and non-electoral periods.

Collectively, these six hypotheses allow us to probe whether there is evidence of permanent campaign activity for online political advertising and how these practices vary by actor, addressing the two identified gaps in the literature.

Methods

In the following analysis, we conduct a large-scale study of online political advertising on Facebook in the UK to test our hypotheses. This context is informative as existing studies have already found evidence of permanent campaigning by parties and political actors (Diamond Citation2019; Lilleker Citation2015). Online political advertising is also widely utilized for campaign activities (Dommett and Bakir Citation2020; Fowler et al. Citation2021), with the UK exhibiting the highest advertising expenditure in Europe and the fourth largest advertising market in the world in 2021 (Statista Citation2021). More instrumentally, the UK context provides access to two types of data: Facebook archives and registration records of partisan and nonpartisan campaign groups. Facebook’s political advertising archiveFootnote3 was released in the UK in 2019, which enables scholars to track activity online via an Application Programming Interface (API). This makes it possible to gather historic detail on advertising characterized by Facebook as political.Footnote4,Footnote5 Whilst scholars have begun to use this resource, to date the data has not been examined for evidence of permanent campaigning.

In addition, the UK Electoral Commission maintains a list of registered political parties active in elections and a list of nonparty campaignersFootnote6 defined as those who “campaign in the run up to elections but do not stand as political parties or candidates” (Electoral Commission n.d.). Hand-coding advertising accounts from the Facebook archive in accordance with the Electoral Commission’s record, we further classify nonparty campaigners into 1) satellite campaigns, which overtly focus on promoting or campaigning against particular political parties and electoral campaigns, and 2) nonpartizan campaigns, whose primary focus is not campaigning for or against a particular party or candidate. Whilst not encompassing all nonparty campaign groups active in the UK, it may be expected that because these organizations register with the Electoral Commission,Footnote7 they are more likely than unregistered groups to be engaged in elections (at least in terms of campaign spend).

Combining these resources, we used computational methods to extract political adverts placed by parties, political leaders, and our two types of nonparty campaign groups. More specifically, we used the Meta Ad Library API (formerly known as the Facebook Ad Library API) version 12.0 to perform customized keyword search of ads in the library. To search the archive and collect all ads for any given period, a user must have prior knowledge of keywords for each individual ad. As this is impossible, the API provides no guarantee of completeness. To ensure the sample of ads we collected is large enough or approximately covers content placed in our chosen period, we use a full-stop as a search term with the assumption that there is a tendency of a full-stop contained in the textual content of ads.

Our analysis focused on the period between 1st December 2018 and 31st December 2021,Footnote8 which resulted in a total of 668,239 adverts placed by 40,534 unique advertisers. Some of our predefined UK political actors did not have adverts in the archive within the specified dates, nonetheless we found 11 out of 12 political parties, 11 out of 26 party leaders, and 52 out of 80 nonparty campaign accountsFootnote9 (including 27 satellite campaign groups and 25 nonpartizan campaign groupsFootnote10) with advertising records in the Facebook archive. Altogether, 74 actors placed a total of 129,685 adverts (). Among these 74 actors, 72 of them placed duplicate adverts containing either the same or similar content for a specific running schedule. We observe that these duplicate adverts are similar in textual content but usually differ in small ways with, for example, slight differences in the images used in different variations. In our analysis, we choose not to remove duplicate adverts because they are part of the total spend in the data archive, but this means we do not report on the number of unique adverts placed by our actors.

Table 1. Number of adverts identified from different types of actor within the Facebook advertising archive between 1st December 2018 and 31st December 2021.

Having identified this data, we build on existing studies in comparing activity during and outside of election periods (Larsson Citation2016). Within the dates of study, the UK held a general election as well as local and mayoral elections. We took the decision to focus on three electoral periods, concentrating on the official campaign periodsFootnote11 for the 2019 general election and the 2019 and 2021 local electionsFootnote12 (). We also collected data for the period when the 2020 local election should have occurred but was postponed due to Covid-19 (Johnson Citation2020). To study non-electoral activity, we took two approaches: initially, we looked at all adverts placed outside our electoral periods to provide a simple comparison. Whilst informative in many regards, we found evidence of other elections - namely party leadership contests (Online Appendix ) - that caused spikes in party-level activity. Given our interest in public-facing electoral activity as evidence of permanent campaigning, we selected three periods that did not contain internal elections and that were so well in advance of electoral periods that election-related activity would be least likely to be in evidence (unless permanent campaigning was in effect). To determine the length of our selected non-electoral periods, we took an average of the number of days covered by our election periods, and then starting from the first of each month identified three periods that contained the average number of days. The precise dates examined are presented in .

Table 2. Types, dates, and duration of electoral and non-electoral periods.

Table 3. Number of adverts placed by political parties, party leaders, satellite campaign group, and nonpartizan campaign group.

Our period of study notably contained the Covid pandemic, which involved three periods of national lockdown and resulted in the postponement of the 2020 local election (Institute for Government, no date). As our primary purpose is not testing the effect of the pandemic on campaigning practice, we do not discuss this variable in detail, however we did ensure that our selected periods capture times at which lockdowns were and were not in place to look for possible variation in campaign practice. For this reason, we retained a focus on the canceled local election in 2020 and included one non-election period in which there was a lockdown (Jan–Feb 2021).

In reporting on data gathered within these periods, we consider two metrics available from the Facebook advertising archive: 1) number of adverts and 2) expenditure on adverts to explore permanent campaign activity. Interpreting our findings, it is important to bear in mind that online political advertising is one form of online campaigning and hence we do not claim that our data is indicative of all online campaigning activity in different media.

Findings

Findings 1: Political parties and party leaders

We begin looking at the aggregate data for political parties and party leaders across the entire 3-year period. This allows us to gain an impression of the overarching trend in the placement of online political advertisements across the electoral cycle, contextualizing our more specific analysis on electoral and our selected non-electoral periods.

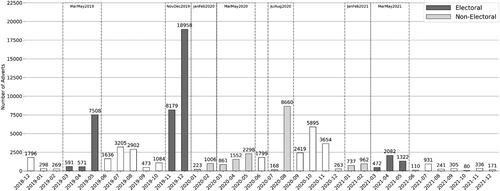

depicts the number of advertisements placed in each month by all our actors between December 2018 and December 2021, with our three electoral periods shaded dark grey and our four non-electoral periods in light grey. Immediately obvious from this figure is the prominence of the UK general election in December 2019. We found 18,958 adverts placed in that month alone, with the second most prolific month being November of that year. This concentration of activity far exceeds the average of 2,271 adverts being placed each month by political parties and party leaders over the three years examined. We can also see that our selected non-electoral periods are broadly representative of activity across the entire non-electoral period.

Figure 1. Number of adverts placed in each month by political parties and leaders between December 2018 and December 2021.

To answer H1, we looked for evidence of permanent campaigning in the form of activity across our selected both electoral and non-electoral periods, shows continuous but low-level activity, suggesting that advertising is used but to a very limited extent outside of general election periods.Footnote13 This finding resonates with work by Vergeer, Hermans, and Sams (Citation2011), which suggests that parties and politicians primarily use social media platforms during election periods. On this evidence, it appears that the use of both paid online advertising on Facebook and organic social media content does not align with the notion of permanent campaigning.

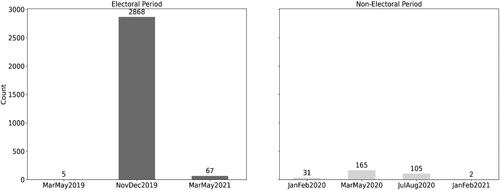

Figure 2. Total number of adverts placed by political parties and party leaders in electoral and non-electoral periods.

To understand the extent to which the general election dominated each actor’s activity, we looked at the ratios of advertising frequency by comparing the average number of adverts placed per day by parties and political leaders at the general election with the number placed in our other election periods ().Footnote14 This analysis showed that, for parties, for every one advert placed per day in other election periods, just under 12 adverts were placed per day at the general election. For party leaders, this trend was even more pronounced, with almost 83 adverts placed per day at the general election for every one per day in our other election periods. There is accordingly a high degree of variation between our selected electoral periods.

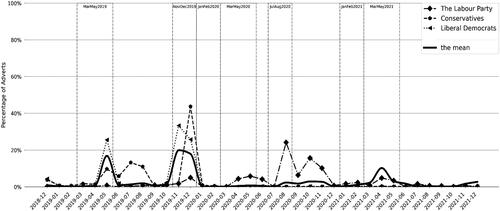

To gain a more detailed understanding of how advertising is used by the actors of interest in H1, we now look into the advertising activities of specific political parties and leaders. We first analyze the practices of 11 political parties in . For non-UK readers, it is worth noting that during this period the Conservative Party was in Government, with Theresa May and then Boris Johnson as Prime Minister (for more information, see House of Commons Library Citation2020).

Table 4. Adverts placed by each party between December 2018 and December 2021.

shows that different political parties did not utilize online political advertising to the same extent, with the Labor Party, Conservative Party and Liberal Democrat Party placing a significantly higher total number of adverts than other parties. Considering evidence of permanent campaigning, we found variations in the number of adverts placed by each party during our specified electoral and non-electoral periods. Only these three major parties placed more than a nominal number of adverts in our selected non-electoral periods, suggesting that not all parties engage in (even low levels of) permanent campaigning. We also found that only the Labor Party placed almost equal numbers of adverts during our electoral and non-electoral periods, whilst all other parties placed their ads predominantly in electoral periods. These findings are important for H1 and suggest differentiation in parties’ use of online advertising. In line with our expectations, it appears that parties use advertising primarily in election periods. For many smaller parties, there is little evidence of permanent campaigning. Even for the Liberal Democrats and Conservatives, there is only minimal investment in this activity outside of electoral periods. There might be different reasons to account for this. It could, for example, be that the Conservatives are drawing on Governmental advertising accounts to engage in campaign activity (Van Onselen and Errington Citation2007). Initial exploratory analysis found that the UK Government account placed just 30 ads (spending £486,935), and the UK Prime Ministerial account 3 (spending £21,798.5) in our selected non-electoral periods, suggesting this may not be the case, but further study is needed to explore this. What is notable is that the Labor Party engages in more consistent campaigning. Our qualitative analysis of Labor’s adverts outside of election periods shows the party to be using advertising to particularly gather data through surveys, with advert text such as:

The Labour Party wants to know how you’re doing. And what you think the Government should do for jobs and the local economy in your area. Take a minute to fill out our short survey. ?️

This kind of activity is akin to the polling activity cited as evidence of permanent campaigning by Joathan and Lilleker (Citation2020, 5), as it represents an effort to acquire more information about the electorate. On this evidence it appears that Labor is utilizing online advertising to engage in permanent campaigning.

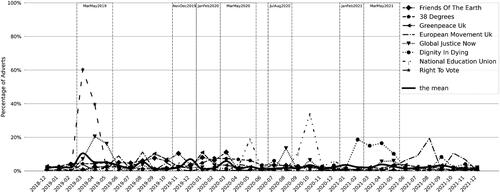

Given the apparent dominance of online advertising in the general election period (), we further examined the relative intensity of advertising placed by the three major parties, normalizing the distribution of adverts over time to compare strategies. By normalizing within each actor across a span of three years, we convert the distribution of adverts with varying ranges to a common, comparable scale without distorting differences in the original ranges of values. offers a more nuanced depiction of how the three major parties are using advertising year-round, with the mean (the solid black line) showing the average number of adverts placed by all parties included in our analysis. It appears that in terms of relative activity, different parties increase their advertising activity at different times, with some intensifying activity in local election periods (i.e., Liberal Democrats in May 2019) and others increasing advertising frequency outside these periods (i.e., Labor in August and October 2020). This analysis suggests that different parties employ advertising in non-uniform ways, making it problematic to draw conclusions about parties’ engagement in permanent campaigning in singular terms.

Figure 3. Percentage of adverts placed in each month by each party: Labor, Conservatives and Liberal Democrats.

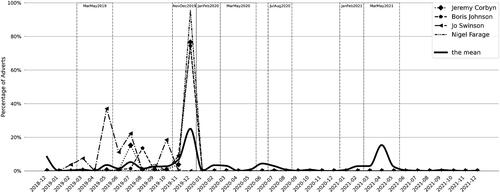

Turning to consider the use of online political advertising by party leaders (), for these accounts, we once again found that adverts were primarily placed in the general election period, with relatively few placed in our other election periods or non-electoral periods. Indeed, across the entire period examined, an average of 167 adverts were placed each month, compared to the average 2,104 adverts fielded per month by political parties.

Looking at the activity of individual leaders, we found a similar pattern. Analysis is somewhat complicated due to the fact that many parties changed leaders during this three-year period (Online Appendix ). It is also worth re-stating that we were not able to find adverts placed by all party leaders within the Facebook ad library, meaning some leaders are not listed here. Nevertheless, we find that most party leaders, including Jeremy Corbyn, Nigel Farage, Teresa May, Colum Eastwood, Nicola Sturgeon, and Boris Johnson placed the vast majority of their adverts in election periods (). Only Keir Starmer and Ed Davey (who were only party leaders for the latter part of this period), and Adam Price (who placed very small numbers of adverts overall) deviate from this trend. In general, we find further support for H1.

Table 5. Adverts placed by each party leader between December 2018 and December 2021.

To further interrogate the pattern of usage within election periods and to consider the strategies by different leaders,Footnote15 we again normalized the number of adverts to look at the distribution over time (). This allows us to see, regardless of the total number of adverts placed, how the timing of those adverts was distributed. Focusing on leaders in office at the 2019 general election, we look at the activity of the leaders of the three main political parties (Labor, Conservative, Liberal Democrat) and Brexit/Reform UK. We can see the leaders focused attention on the general election, with the mean (the solid black line) depicting the average distribution of adverts placed by all political leaders included in our analysis. For the most part, our analysis of specific leaders mirrors our above finding, suggesting that these accounts become largely inactive outside of general election campaigns. Where they are used, adverts tend to relate to party-specific events (such as leadership elections). These findings suggest that party leader accounts are used differently to party accounts, exhibiting less evidence of permanent campaigning.

Figure 5. Percentage of adverts placed in each month by party leaders: Jeremy Corbyn, Boris Johnson, Jo Swinson, and Nigel Farage.

Combining these findings, we find partial support for H1. Our data suggests that political parties and political leaders have higher numbers of adverts during electoral periods than non-electoral periods. However, it appears that their adverts are concentrated on general election periods as opposed to other elections. Drawing this conclusion, we also note unexpected variations in parties’ and leaders’ use of online political advertising. Not only do we find differences in specific parties’ level of engagement beyond election periods, but we also find that party leaders advertised less frequently outside of general election periods than their party equivalents. In terms of permanent campaigning, these findings cumulatively suggest only parties make a limited investment in advert numbers outside of electoral periods.

Having reviewed data on the amount of adverts, we now turn to consider the spending on adverts across these time periods to test H2. In terms of the amounts expended, Facebook provides bracketed data on the minimum and maximum spend on each given advertisement rather than precise spending figures. Accordingly, the data doesn’t allow us to provide an accurate figure for exactly what is spent. To facilitate analysis, we looked at the midrange spend by adding together the minimum and maximum spend and dividing by two.

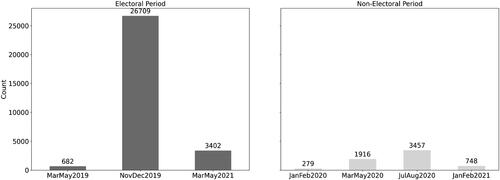

Concentrating on the activity of political parties and party leaders, we can see large differences in the total amounts spent by these two groups of actors (). Parties spent significantly more than leaders, with the midrange spend suggesting that parties spent over £7.1 million and party leaders just £1.1 million. In terms of the distribution of spending between our electoral and non-electoral periods, we can see that election periods command far higher levels of spend. Parties therefore spent £3.7 million in election periods but only £333,202 in non-election periods. Looking at the ratios of spending, this means that for every £1 spent per day in a non-election period, £15 per day was spent in an election period. In contrast, leaders spend £804,028 in election periods and £16,598 in non-election periods, meaning that for every £1 spent per day in our selected non-election periods, almost £65 was spent per day in an election period. This data therefore supports H2, but again we can see that the general election period dominated spending. If we look at the ratios of spending within the electoral periods, we see that, for parties, for every £1 spent per day in both local election periods, £17 was spent per day during the general election. For leaders, however, the trend is again starker, for every £1 spent per day in the local election periods, £102 was spent per day at the general election.

Table 6. Midrange spend for the different account types by electoral and non-electoral periods.

Summary of findings on H1 and H2

Overall, our findings partially support H1 and H2. We show that political parties and political leaders do concentrate investment in online political advertising – in terms of both the amount of adverts and total spend on adverts – on election periods. However, most of their activity is focused on general elections. Underneath these headline trends, we find variations between advertising use by parties and party leaders – with the latter using online advertising almost exclusively for general election campaigns. We also show the difficulties of talking in uniform terms about the behavior of different parties and leaders, showing specific actors to exhibit different strategies. In regard to permanent campaigning, our findings provide only limited evidence of this phenomenon and suggest that, when evident, it is manifest in low level investment outside of electoral periods by some (rather than all) parties, and not by party leaders.

Findings 2: Satellite campaigns

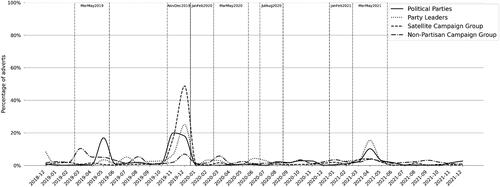

Turning to our remaining hypotheses, to contextualize our findings, we first compare the number of adverts placed by parties, leaders and both types of nonparty campaign groups over the entire three-year period. To look at the distribution of adverts in comparable terms, we normalized the number of adverts by actor to see whether there were similar patterns in when adverts were placed (). Drawing initial insights from this data, we can see that satellite campaign groups appear to mirror the activity of political parties and leaders, as there is a marked increase in the frequency of adverts placed during the general election period. In contrast, nonpartizan campaign groups do not appear to exhibit the same intensification in activity but appear to place adverts more uniformly over time.

Figure 6. Percentage of adverts placed in each month by account type: political parties, party leaders, satellite campaign group, and nonpartizan campaign group.

To interrogate this trend in greater detail, we focused on the specific behavior of satellite and nonpartizan campaign groups in our chosen electoral and non-electoral periods (). In terms of the relative distribution of adverts across our selected electoral and non-electoral periods, we can see that satellite campaign groups concentrated their attention on electoral periods, placing 8,235 in these periods, and just 308 in our non-electoral periods. Looking at the ratios of activity, this means that for every 1 advert placed per day in a non-electoral period, almost 36 per day were placed in an electoral period, showing a more pronounced focus on these moments than evident for ratios for party leaders (13) or parties (6). Accordingly, we find evidence in support of H3. As with previous analysis, we observed a significant focus of attention on the general election. Indeed, comparing the electoral periods, we find that for every one advert placed per day in other election period, 82 were placed per day in the general election period - closely mirroring the trend found for party leaders (83).

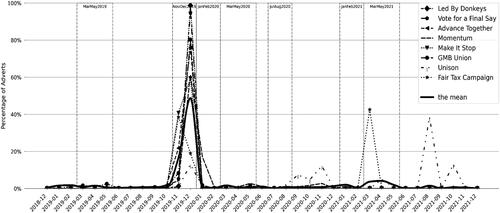

To consider differences in the behavior exhibited by specific satellite campaign groups, we normalized the number of adverts placed by the eight most active satellite campaign groups (in terms of number of adverts) and mapped the distribution to see when adverts were placed (). Confirming the trend above, we can see that most of these groups focused their activity almost exclusively on the general election. There was, however, no complete uniformity in approach, with, for example, Vote for a Final Say (one satellite group) showing a spike in advertising in March and August 2020 (). For the most part, however, we find support for H3.

Figure 7. Percentage of adverts placed in each month by eight most active satellite campaign groups.

Looking again at the financial insights offered in above, we can also see that in regard to spending on adverts, satellite campaign groups concentrated their spending on election periods, exhibiting similar spending patterns to political parties and leaders. Comparing spend in our election periods with our chosen non-electoral periods, we can see that satellite campaigns spent a total of £1.6 million, with nearly £1.3 falling in election periods, and £36,346 falling in our non-election periods. Considering the ratio of spend, this means that for every £1 spent per day in non-electoral periods, £47 was spent per day in electoral periods. Once again, we also found that spending within election periods was concentrated on general elections, with a ratio of every £1 spent per day in other election periods compared to £34 per day for the general election. The campaign behavior of satellite campaign groups – in terms of advert numbers and spend – therefore followed the patterns of political parties and particularly political leaders, offering support to H3 and H4.

Findings 3: Nonpartizan campaigns

In relation to H5, shows the amount of adverts placed by nonpartizan campaign groups during electoral and non-electoral periods. In contrast to the analysis of our other type of actor, we did not find that the use of advertising was focused predominantly on election periods. Indeed, whilst 5,000 adverts were placed in election periods, 6,353 were placed in our selected non-election periods. Looking at the ratios, this means that there was an approximate 1:1 ratio between election and non-election days in terms of the number of adverts placed. In line with H5, we therefore find evidence that nonpartizan campaign groups do place similar numbers of adverts during electoral periods and non-electoral periods.

Digging further into these results, we looked at the activity of specific nonpartizan campaign groups to again look for different possible strategies (). Focusing on the activity of the eight most active groups (in terms of number of adverts placed) we can see a far more regular frequency of advertising. A small number of advertisers exhibit spikes in activity (e.g., Right to Vote in March and April 2019 and National Education Union in October 2020), but most field a relatively consistent number of adverts across the entire period. Although there may therefore be individual exceptions to the rule, it appears that most nonpartizan groups place similar numbers of adverts during electoral and non-electoral periods.

In terms of financial data, suggests that nonpartizan groups also distributed their spending more equally than others in electoral and non-electoral periods. Looking at their ratios of spending across our electoral and non-electoral periods, we found that for every £1 spent per day in a non-election period by nonpartizan groups, there was only, on average, a single pound spent per day in electoral periods. This suggests a vastly different pattern of expenditure to other actors and provides evidence of investment in permanent campaigning. Whilst we did find that the general election period was still the single highest period for spending – at £440,419 – the ratio of spending was far lower than for our other groups, with just under £3 spent per general electoral day compared to each £1 spent per other electoral period day. In regard to H6, we therefore find evidence that nonpartizan campaign groups do devote similar levels of spending to electoral periods and non-electoral periods. Looking at H5 and H6, we therefore find support for the idea that nonpartizan campaign groups use online political advertising in ways more traditionally associated with permanent campaigning than most parties, leaders, or satellite campaign groups.

Discussion

In this paper we set out to explore the use of online political advertising by political parties, party leaders and two different types of nonparty campaign groups, exploring a hitherto unexamined form of digital campaign activity. Looking for evidence of permanent campaigning, we sought to address two important gaps in the literature by examining the use of online political advertising and the behaviors of different types of actors engaged in political campaigns. Posing six hypotheses, we have found, first, that parties and political leaders do place a higher number of adverts in electoral periods as opposed to non-electoral periods (H1) and also expend more money on advertising during electoral periods (H2). And yet, our data provided more nuanced insights into these hypotheses, revealing that spend was almost exclusively concentrated on general elections and that parties and leaders exhibited different advertising strategies. Indeed, we showed that leaders’ accounts were largely inactive outside of general election periods, and that individual parties engaged in permanent campaign activity to different degrees. Looking beyond elite political actors, we found evidence that satellite campaign groups exhibit similar behavior to parties and political leaders. In terms of advertising frequency (H3) and spend (H4), we therefore found increased attention placed on election periods, with a particular focus on the general election period. We also showed that nonpartizan campaign groups exhibit a different pattern of usage, placing a similar number of adverts in electoral and non-electoral periods (H5) and devoting similar expenditure within these periods (H6).

Cumulatively, these findings are significant as they provide only limited evidence of permanent campaigning via online political advertising. Amongst political parties, we found that many did not place adverts in our selected non-electoral periods, and the Liberal Democrats and Conservatives did not use this medium extensively outside of election campaigns. We also found that party leaders’ accounts were barely used for advertising beyond general and, in some cases, other election campaigns. Similar trends were also evident amongst satellite campaign groups. These findings suggest that the digital revolution has not prompted political actors to engage in continuous campaigning on the internet and social media (Klinger Citation2013). Echoing the findings of numerous studies of organic social media campaigning (often on Twitter), our research suggests there is a degree of continuity in the use of organic and paid digital media, as parties, leaders and satellite campaign groups do predominantly focus their activity on electoral periods, and specially on general elections (Vergeer, Hermans, and Sams Citation2011; see also Ceccobelli Citation2018, Vasko and Trilling Citation2019).

Our findings did, however, suggest that it is problematic to talk about actors in uniform terms. Looking at the particular advertising practices of different parties, we observed variations. The Labor party, for example, placed relatively equal numbers of adverts within and outside of our chosen periods and exhibited the kind of continuous data collection activity previously deemed indicative of permanent campaigning (Joathan and Lilleker Citation2020). This supports the idea that particular actors exhibit “differing strategies” in their use of digital technologies (Lilleker and Jackson Citation2010) and suggests that different actors can “harness and otherwise manage the opportunities wrought by new information and communication technologies” (Elmer, Langlois, and McKelvey Citation2012, 4) in different ways. Interestingly, our analysis suggests that resource may play a role as there were variations in practice between larger and smaller parties (Kefford et al. Citation2022; Power Citation2020). Yet other factors also appear at play, – as the Conservative Party (a party with significant resource (Electoral Commission Citation2022)) did not exhibit evidence of permanent campaigning. This may be due to the party’s use of Governmental communication channels to field online political advertising (Van Onselen and Errington Citation2007). Whilst our initial exploratory analysis raises questions about this explanation, further exploratory study is required.

Our data also raises interesting questions about the status of different actors involved in electoral campaigns. Our analysis suggests that political leaders primarily place adverts during general election periods and exhibit little activity outside of these moments. Given recent scholarship diagnosing the personalization of politics in the UK (Langar Citation2020), this trend is surprising as it might be expected that individual leaders (as opposed to parties) would be used to engage electors year-round. Further qualitative investigation is needed to consider the strategies behind the use of different accounts, but our data suggests that the trend toward personalization may not be played out in this element of campaign practice.

Perhaps most significantly, this study has extended previous work on permanent campaigning by looking at nonparty campaign groups. Offering new insight into the ways that different actors use campaign tools, we have shown that satellite groups mirror parties and political leaders and engage in limited permanent campaigning. In contrast, nonpartizan campaign groups appear to play a more permanent and consistent role in placing political advertising. Emerging from this finding, a range of questions for further study arise, particularly about the degree to which the content of materials placed by nonpartizan groups varies over time. We would accordingly urge future studies to explore whether the content fielded by nonpartizan groups is similar within and outside of election periods to detect whether elections influence these groups’ campaigning focus.

Our study was of particular interest as it spanned the period of the Covid pandemic and hence contained periods of national lockdown that were captured in our selected periods. Whilst it was not our primary focus to examine the impact of Covid on election campaigning we interestingly did not see significant variations in campaign activity. This suggests that periods of national lockdown did not have a clear effect on campaigning patterns, however, future study devoted to the impact of Covid on campaigning is required to verify this finding.

It is also important to acknowledge the limitations of our analysis. Due to the availability of data, we were only able to examine the evidence of permanent campaigning on Facebook paid-for advertising. It is possible that during the same period our actors also fielded adverts on other online platforms as part of their digital campaigning. We therefore do not claim to have fully scrutinized our actors’ online advertising activity and urge future studies to compare and contrast advertising usage on multiple platforms.

The trends we observe from the major political parties attest Wring and Ward (Citation2015, 235) argument that parties take different approaches to utilizing digital technology and that “party context is at least as significant as the technology itself in shaping their campaigns.” Indeed, our findings indicate that even parties with similar levels of resource - Labor and the Conservatives - employ different strategies. This may reflect their relative position in Government, with Labor, as the official opposition party needing to engage more in permanent campaigning through their party accounts, whereas the Conservatives may be able to utilize Government accounts. Permanent campaigning activity via different actors is therefore likely to reflect a range of factors including campaign strategies, financial resources, incumbency status and election competitiveness. Future research should attempt to test the impact of these factors with available data.

Whilst our study has focused on the UK, these findings are likely to be of interest to scholars in a range of geographic contexts. Spotlighting the use of online political advertising, and challenging the idea of permanent campaigning, this study raises questions about the degree to which similar trends are likely to be found elsewhere. Our analysis shows variation in the degree to which different actors utilize online advertising throughout the electoral calendar, but questions remain about the drivers of these differing behaviors. Comparative analysis has the potential to reveal whether similar parties in different contexts exhibit similar strategies, and whether there are underlying drivers of the trends we observe. Our study can accordingly be used to generate future hypotheses that help to understand differences in campaign activity.

Conclusion

This paper set out to examine evidence of permanent campaigning in online political advertising. Addressing two gaps in the extant literature, we have conducted a large-scale analysis of online political advertising between 2018 and 2020 in the UK. Mapping the practices of political parties, party leaders, satellite campaign groups and nonpartizan campaign groups, we have shed light on the use of online political advertising and challenged the idea that this tool is widely used for permanent campaigning. Analyzing trends in the frequency of adverts and spending devoted to advertising in electoral and non-electoral periods, we have found that parties, leaders, and satellite campaign groups focus attention on electoral periods and specifically general elections, with only parties exhibiting low levels of activity outside this period. In contrast, we find that nonpartizan campaign groups exhibit more similar levels of spending within and outside election periods. It is only therefore amongst this latter group that we find strong evidence for permanent campaigning. In addition, we have found variations in the strategies deployed by specific actors in each of these categories, showing nuance in the way online political advertising is deployed in campaigns. These findings are significant for our understanding of the way in which different types of media are used for campaign activity, suggesting that paid media is utilized intermittently by most actors advancing partisan objectives, and that adoption is not uniform.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (43.7 KB)Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In focusing on Facebook, we recognise that online political advertising can appear on other platforms and therefore our data is not indicative of all online political advertising activity. However, as Facebook is the most commonly used platform by all parties, we focus our attention on this outlet.

2 For details, see: https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/non-party-campaigners-where-start.

3 According to Meta, the purpose of the Ad Library is to improve advertising transparency by offering a comprehensive, searchable collection of all ads that are running across Meta technologies. Anyone can explore the ad library, with or without a Facebook account. An ad will appear in the Ad Library within 24 hours from the time it gets its first impression. Any changes or updates made to an ad will also be reflected as well. For ads on social issues, elections, or politics in particular, Meta requires advertisers to include information about who paid for them, with a ‘Paid for by’ disclaimer. These political ads are stored in the archive for seven years. For more information, see: https://www.facebook.com/help/259468828226154.

4 According to Meta, ads about social issues, elections or politics are: made by, on behalf of or about a candidate for public office, a political figure, a political party, a political action committee or advocates for the outcome of an election to public office; or about any election, referendum, or ballot initiative, including “go out and vote” or election campaigns; or about social issues in any place where the ad is being published; or regulated as political advertising. Source: https://en-gb.facebook.com/business/help/1838453822893854.

5 See Dommett and Bakir (Citation2020), Kreiss and Barrett (Citation2020), and Edelson et al. (Citation2019) for an overview of political advertising archives.

6 A single, comprehensive list of parties and campaign groups is not available from the Electoral Commission. We accordingly compiled our own list of all the parties and organisations registered at any point in the time period we study by tracing month-by-month variations in the Electoral Commission’s records.

7 Individuals or organisations (e.g., a UK registered trade union, a UK charitable incorporated organisation) are required to register with the Electoral Commission as a registered non-party campaigner when they spend over £20,000 in England or £10,000 in any of Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland during a regulated period. For more details, see: https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/sites/default/files/pdf_file/sp-registering-npc.pdf.

8 Facebook archive provides available UK advertising data from 29th November 2018 to present. Our analysis started from December 2018 to cover three years of political advertising activities in and outside of electoral periods. Data was downloaded on 24th January 2022.

9 See Online Appendix for an overview of classified accounts.

10 See Online Appendix for details.

11 The official campaign period is specified by Parliament. For more information, see: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn05262/.

12 It’s useful to note that the 2019 European Parliament election was held on Thursday 23 May 2019. In this paper, however, we decided to only focus on UK-level elections.

13 Comparing and , it initially appears in that our first electoral period (March-May 2019) exhibited a large number of adverts, but closer analysis shows that the majority of these adverts were placed after the election. Therefore, whilst 8,670 adverts in total were placed between March to May 2019 (), only 682 fell within the local election period examined (). This is because a significant proportion of adverts were placed after 2nd May 2019 and targeted towards the European Parliament election, which was held on 23rd May 2019.

14 Note the total number of adverts for electoral and non-electoral periods does not add up to the total number of adverts in because these are only our selected periods, which do not capture all periods.

15 We gathered data from the accounts of all the individuals who acted as party leader during our chosen time period. Not all party leaders placed adverts in this time period. For the most part the adverts we collected were placed whilst that individual was party leader, but our data did contain small numbers of ads placed before or after their election, for example, during leadership campaigns.

References

- Bimber, B., M. Cunill, L. Copeland, and R. Gibson. 2015. “Digital Media and Political Participation: The Moderating Role of Political Interest across Acts and over Time.” Social Science Computer Review 33 (1):21–42. doi: 10.1177/0894439314526559.

- Blumenthal, S. 1980. The Permanent Campaign: Inside the World of Elite Political Operatives. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Blumler, J. G. 2016. “The Fourth Age of Political Communication.” Politiques de Communication 1:19–30. doi: 10.3917/pdc.006.0019.

- Bruns, A. 2019. “After the ‘APIcalypse’: Social Media Platforms and Their Fight against Critical Scholarly Research.” Information, Communication & Society 22 (11):1544–66. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2019.1637447.

- Ceccobelli, D. 2018. “Not Every Day is Election Day: A Comparative Analysis of Eighteen Election Campaigns on Facebook.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 15 (2):122–41. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2018.1449701.

- Conaghan, C., and C. de la Torre. 2008. “The Permanent Campaign of Rafael Correa: Making Ecuador’s Plebiscitary Presidency.” Press/Politics 13 (3):267–84. doi: 10.1177/1940161208319464.

- Council of Europe. 2022. “Recommendation CM/Rec(2022)12 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on Electoral Communication and Media Coverage of Election Campaigns.” Accessed April 21, 2022. https://search.coe.int/cm/pages/result_details.aspx?objectid=0900001680a6172e

- Diamond, P. 2019. The End of Whitehall? Government by Permanent Campaign. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Doherty, B. J. 2014. “Presidential Reelection Fundraising from Jimmy Carter to Barack Obama.” Political Science Quarterly 129 (4):585–612. doi: 10.1002/polq.12253.

- Domalewska, D. 2018. “The Permanent Campaign in Social Media: A Case Study of Poland.” Central and Eastern European eDem and eGov Days 331:461–8. doi: 10.24989/ocg.v331.38.

- Dommett, K., and L. Temple. 2018. “Digital Campaigning: The Rise of Facebook and Satellite Campaigns.” Parliamentary Affairs 71 (suppl_1):189–202. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsx056.

- Dommett, K., and M. Bakir. 2020. “A Transparent Digital Election Campaign? The Insights and Significance of Political Advertising Archives for Debates on Electoral Regulation.” In Britain Votes: The 2019 General Election, edited by L. Thompson, J. Tonge, and S. W. Heeg, 208–24. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dommett, K., G. Kefford, and S. Power. 2021. “The Digital Ecosystem: The New Politics of Party Organization in Parliamentary Democracies.” Party Politics 27 (5):847–57. doi: 10.1177/1354068820907667.

- Edelson, L., S. Sakhuja, R. Dey, and D. McCoy. 2019. “An Analysis of United States Online Political Advertising Transparency.” Working paper, Cornell University. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1902.04385.

- Electoral Commission. 2022. “UK Political Parties’ Accounts Published.” https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/media-centre/uk-political-parties-accounts-published-0.

- Electoral Commission. n.d. “Guidance: Non-Party Campaigner.” Accessed January 10, 2022. https://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/i-am-a/campaigner/non-party-campaigner

- Elmer, G., G. Langlois, and F. McKelvey. 2012. The Permanent Campaign: New Media, New Politics. New York: Peter Lang.

- Elmer, G., G. Langlois, and F. McKelvey. 2014. “The Permanent Campaign Online: Platforms, Actors, and Issue-Objects.” In Publicity and the Canadian State: Critical Communications Perspectives, edited by K. Kozolanka, 240–61. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Fowler, E., M. Franz, G. Martin, Z. Peskowitz, and T. Ridout. 2021. “Political Advertising Online and Offline.” American Political Science Review 115 (1):130–49. doi: 10.1017/S0003055420000696.

- Fulgoni, G. M. 2015. “How Brands Using Social Media Ignite Marketing and Drive Growth: Measurement of Paid Social Media Appears Solid but Are the Metrics for Organic Social Overstated?” Journal of Advertising Research 55 (3):232–6. doi: 10.2501/JAR-2015-004.

- Gibson, R. K. 2020. When the Nerds Go Marching in: How Digital Technology Moved from the Margins to the Mainstream of Political Campaigns. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Homonoff, H. 2020. “2020 Political Ad Spending Explored: Did it Work?” Accessed January 10, 2022. https://www.forbes.com/sites/howardhomonoff/2020/12/08/2020-political-ad-spending-exploded-did-it-work/

- House of Commons Library. 2020. “. General Election 2019: Results and Analysis.” Accessed January 10, 2022. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8749/CBP-8749.pdf

- Institute for Government. n.d. “Timeline of UK Government Coronavirus Lockdowns and Restrictions.” https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/charts/uk-government-coronavirus-lockdowns.

- Joathan, ., and D. G. Lilleker. 2020. “Permanent Campaigning: A Meta-Analysis and Framework for Measurement.” Journal of Political Marketing 22 (1):1–19. doi: 10.1080/15377857.2020.1832015.

- Johnson, N. 2020. “Coronavirus: FAQs on Postponed Elections.” Accessed January 10, 2022. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/coronavirus-faqs-on-postponed-election/

- Katz-Kimchi, M., and I. Manosevitch. 2015. “Mobilizing Facebook Users against Facebook’s Energy Policy: The Case of Greenpeace Unfriend Coal Campaign.” Environmental Communication 9 (2):248–67. doi: 10.1080/17524032.2014.993413.

- Kefford, G., K. Dommett, J. Baldwin-Philippi, S. Bannerman, T. Dobber, S. Kruschinski, S. Kruikemeier, and E. Rzepecki. 2022. “Data-Driven Campaigning and Democratic Disruption: Evidence from Six Advanced Democracies.” Party Politics, Online First doi: 10.1177/13540688221084039.

- Klinger, U. 2013. “Mastering the Art of Social Media: Swiss Parties, the 2011 National Election and Digital Challenges.” Information, Communication & Society 16 (5):717–36. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2013.782329.

- Koliastasis, P. 2020. “The Permanent Campaign Strategy of Prime Ministers in Parliamentary Systems: The Case of Greece.” Journal of Political Marketing 19 (3):233–57. doi: 10.1080/15377857.2016.1193835.

- Kreiss, D., and B. Barrett. 2020. “Democratic Tradeoffs: Platforms and Political Advertising.” The Ohio State Technology Law Journal 16 (2):493–519.

- Langar, A. O. 2020. The Personalisation of Politics in the UK. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Larsson, A. O. 2015. “The EU Parliament on Twitter: Assessing the Permanent Online Practices of Parliamentarians.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 12:149–66. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2014.994158.

- Larsson, A. O. 2016. “Online, All the Time? A Quantitative Assessment of the Permanent Campaign on Facebook.” New Media & Society 18 (2):274–92. doi: 10.1177/1461444814538798.

- Lilleker, D. G. 2006. Key Concepts in Political Communication. London: Sage.

- Lilleker, D. G. 2015. “Interactivity and Political Communication: Hypermedia Campaigning in the UK.” Comunicação Pública 10 (18):1–16. doi: 10.4000/cp.1038.

- Lilleker, D. G., and N. A. Jackson. 2010. “Towards a More Participatory Style of Election Campaigning: The Impact of Web 2.0 on the UK 2010 General Election.” Policy & Internet 2 (3):69–98. doi: 10.2202/1944-2866.1064.

- Marland, A., T. Giasson, and A. L. Esselment, eds. 2017. Permanent Campaigning in Canada. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Marques, F., J. Aquino, and E. Miola. 2014. “Congressmen in the Age of Social Network Sites: Brazilian Representatives and Twitter Use.” First Monday 19 (5):1–16. doi: 10.5210/fm.v19i5.5022.

- Møller, L., and A. Bechmann. 2019. “Research Data Exchange Solution.” Accessed April 18, 2022. https://www.disinfobservatory.org/download/26541

- Norris, P. 1997. “The Battle for the Campaign Agenda.” In New Labour Triumphs: Britain at the Polls, edited by A. King, D. Denver, I. Mclean, P. Norris, P. Nortan, D. Sanders, and P. Seyd, 113–44. Chatham House Publishers, Chatham, New Jersey.

- Ornstein, N. J., and T. E. Mann. 2000. The Permanent Campaign and Its Future. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute Press.

- Power, S. 2020. Party Funding and Corruption. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Smith, R. A. 1995. “Interest Group Influence in the US Congress.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 20 (1):89–139. doi: 10.2307/440151.

- Statista. 2021. “. Advertising spending in the world’s largest ad markets in 2021.” Accessed April 18, 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/273736/advertising-expenditure-in-the-worlds-largest-ad-markets/

- Tromble, R. 2021. “Where Have All the Data Gone? A Critical Reflection on Academic Digital Research in the Post-API Age.” Social Media + Society 7 (1):1–8. doi: 10.1177/2056305121988929.

- Van Onselen, P., and W. Errington. 2007. “The Democratic State as a Marketing Tool: The Permanent Campaign in Australia.” Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 45 (1):78–94. doi: 10.1080/14662040601135805.

- Vasko, V., and D. Trilling. 2019. “A Permanent Campaign? Tweeting Differences among Members of Congress between Campaign and Routine Periods.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 16 (4):342–59. doi: 10.1080/19331681.2019.1657046.

- Vergeer, M., L. Hermans, and S. Sams. 2011. “Online Social Networks and Micro-Blogging in Political Campaigning: The Exploration of a New Campaign Tool and a New Campaign Style.” Party Politics 19 (3):477–501. doi: 10.1177/1354068811407580.

- Wen, W. C. 2014. “Facebook Political Communication in Taiwan: 1.0/2.0 Messages and Election/Post-Election Messages.” Chinese Journal of Communication 7 (1):19–39. doi: 10.1080/17544750.2013.816754.

- Wring, D., and S. Ward. 2015. “Exit Velocity: The Media Election.” Parliamentary Affairs 68 (suppl_1):224–40. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsv037.