ABSTRACT

Throughout the early twentieth century, the widespread growth of coffee drinking in Sweden led for calls by health reformers, doctors and scientists to implement measures to curtail what they deemed “coffee abuse.” Debates about the dangers of coffee took place in Swedish Parliament and trickled out into the popular press. It was not long before canny manufacturers saw an opportunity to capitalize upon this, introducing coffee substitutes onto the Swedish market. One of the most popular brands was the roasted wheat bran drink Postum. This article seeks to investigate the early marketing practices of Postum in Sweden and how the brand used advertisements to exploit the public’s growing fears around coffee and put itself forward as a viable substitute that was essential for good health. Using a dataset of 200 advertisements published in Svenska Dagbladet between 1926 and 1940, it demonstrates how Postum skewed scientific/medical knowledge on caffeine to their advantage, urging consumers to buy Postum to protect themselves against neurasthenia, insomnia and digestive disorders. In doing so, Postum went far beyond its role as a drink, instead tapping into discourses of wellbeing, morality and productivity, which remain a central part of food marketing today.

Introduction

At the beginning of the twentieth century, a major discussion was taking place in Sweden about the dangers of caffeine. Rapidly developing scientific and medical discoveries had led to an increased public understanding of the connection between food, bodies and health (Lundqvist Wanneberg Citation2019), sparking a growing health reform movement which put pressure on the government to clamp down on what they called kaffemissbruk (coffee abuse). Throughout the 1910s and 1920s, debates took place in the Riksdag (Swedish Parliament) about whether to impose a ban on coffee and quickly spilled out into the popular press, where arguments were often elaborated and embellished (Eklund Citation2022). It was not long before canny manufacturers – both national and international – saw an opportunity to capitalize upon this hot topic and its scaremongering discourse by launching a range of “healthy” coffee substitutes onto the Swedish market.

One of the bestselling coffee substitutes was Postum – a roasted grain beverage first developed in the US by the Postum Cereal Company and introduced to Sweden in 1926 by the general agent AB Hugo Österberg. Postum had achieved major success across North America in the pre-First World War era, but had since experienced a decline in sales following the increased surveillance of medical claims in advertising (Prendergast Citation2010). Sweden offered an interesting new market for Postum because there were no regulations in place at the time to govern false advertising (Åström Rudberg Citation2019). This made it possible for the in-house marketing team of local distributor AB Hugo Österberg to tap into anxieties around the country’s caffeine debate and make bold scientific claims about the health-giving properties of the beverage. These advertisements took inspiration from past US examples created by Postum’s in-house advertising agency, yet were localized to fit the Swedish context, accentuating Postum’s ability to “cure” neurasthenia, insomnia and digestive disorders. They were aimed particularly at the middle classes who had greater disposable income and could be easily swayed by the rhetoric of science, technology and modernity (Stendahl Citation2016).

This paper seeks to investigate the early marketing practices of Postum in Sweden and how advertisements were used to exploit the public’s growing fears around coffee and frame the product as a viable substitute that was essential for good health. The collected advertisements come from the Svenska Dagbladet Newspaper Archive and were published between 1926 and 1940. They are approached through the theoretical framework and methodological toolkit of multimodal critical discourse analysis (MCDA)—a way of uncovering how language and other semiotic choices are used to make meaning in texts (Ledin and Machin Citation2018, Citation2020). Through MCDA, I demonstrate how Postum skewed scientific and medical knowledge on caffeine to their advantage, often overstretching the truth to frighten consumers into buying their product to “protect” themselves against a range of health issues. In doing so, Postum went far beyond its role as a drink, instead tapping into broader societal discourses of wellbeing, morality and productivity.

To date, studies on the use of (pseudo)science in food marketing have been predominantly carried out in a contemporary setting. Research has explored probiotic yogurts (Koteyko Citation2009), margarine (Jovanovic Citation2014), protein snacks (Chen and Eriksson Citation2019), oat milk (Ledin and Machin Citation2020) and nootropic drinks (Chen and Eriksson Citation2021), to name but a few examples. While these studies are valuable, in focusing on a modern context, many risk overstating the novelty of (pseudo)science in food marketing and fail to recognize the long-established relationship that dates back to the mid-nineteenth century. In recent years, a body of important historical research has been developed to change this perception, most notably by O'Hagan (Citation2020a, Citation2021b, Citation2021a, Citation2022b) and Eriksson and O’Hagan (Citation2021, Citation2022). Some investigations have also been conducted on the use of (pseudo)science in historical advertisements for baby food (Cesiri Citation2022), breakfast cereals (Kideckel Citation2018) and fruit and vegetables (Nelson, Das, and Ahn Citation2020). However, most historical explorations are still largely focused on patent medicines (Marcellus Citation2008; Petty Citation2019; Segal Citation2019) and beauty products (Walker Citation2007; Scott Citation2015; Santos Citation2020). Furthermore, they tend to have a US or UK focus and employ archival methods only, meaning that our understandings of how (pseudo)science has been historically employed in food marketing is geographically and methodologically limited.

Thus, this paper breaks new ground in its focus on the marketing of a coffee substitute in early twentieth-century Sweden, using a previously unpublished dataset and an MCDA perspective. This approach helps identify how word, image, color, typography, layout and composition work together to convey meaning about the “dangers” of caffeine, as well as to tease out any buried discourses, their functions and potentially contradictory messages, particularly in the context of health and wellbeing. The findings will illustrate the deeply entrenched link between food marketing, changing scientific/medical knowledge and public debates around health and morality. This has the potential to contribute new knowledge on the historical marketing of coffee substitutes and how the meaning potentials of semiotic resources can be mobilized by those in positions of power for their own personal agendas, often taking advantage of consumer anxieties to sell products.

The politics and discourses of coffee in Sweden: an historical perspective

Coffee has never been a neutral drink. Ever since its introduction to Europe in the sixteenth century, it has gone through fluctuating periods of popularity, influenced by trade policies, political debates, associations with “good” and “bad” health and broader discourses around social revolts, moral decay and fears of modernity (Burnett Citation1999). In Sweden, coffee was seen as a major threat to the country from the very beginning. Strict regulations were imposed on the opening hours of coffee houses based on concerns that they would serve as meeting places to plan revolutions, while five separate coffee bans were established by the Riksdag throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Lindberg Citation2018). While the bans served to promote the consumption of domestic goods and reduce the import of foreign products, major propaganda campaigns were launched to convince the public that coffee was dangerous (ibid). Techniques ranged from the publication of “scientific” treatises to coffee experiments,Footnote1 with regular “coffee raids” carried out to catch anybody caught with the beverage; the guilty parties were subsequently fined or imprisoned and publicly shamed in the local newspaper (Knutsson and Hodacs Citation2021).

Once the final coffee ban was overturned in 1823, the drink became more popular than ever, served openly in swisseries (sit-down bakeries), during workplace breaks and at church coffee mornings. Reduced import charges meant that coffee could also now be enjoyed in the comfort of one’s own home (Lindberg Citation2018). However, this widespread growth of coffee drinking raised alarm bells for health reformers, doctors and scientists who became particularly concerned that coffee consumption was posing a threat to the future of Sweden (Nilsson Citation2015). The health reform movement adhered to the strict belief of the link between health and morality and saw nutrition as embedded in nationalist rhetoric: i.e., it was one’s moral duty to be a “strong” citizen and to neglect health through poor diet was deemed selfish and inexcusable (O’Hagan Citation2020b). They focused their attention on mothers who they felt were becoming “sickened” by coffee abuse and risked producing weak, unhealthy children due to their increased nerves and stomach disorders, which would result in an overall degeneration of the Swedish population. Much of this discourse was governed by growing fears around modernity and the changing role of women, with many in favor of new regulations on coffee using the drink as a scapegoat in order to promote their desire to return to a premodern Gemeinschaft free of industry, technology and busy urban life (Eklund Citation2022).

Under increasing pressure from the health reform movement, in 1911, Carl Lindhagen of the Swedish Social Democratic Party agreed to introduce a bill to the Riksdag demanding an investigation into coffee abuse. Over the next two decades, the “dangers” of coffee formed a central topic in Swedish politics. As the topic of alcohol prohibition was also being discussed during this period, it was inevitable that the two issues became swiftly linked together, with those against the alcohol ban blaming the sobriety movement for coffee abuse and arguing that their anti-alcohol campaigns encouraged excessive coffee consumption (ibid).

Such debates spilled out into the popular press, where they took on a whole new life of their own. While some newspaper reports carried an element of truth (e.g., the link between caffeine and insomnia, anxiety and heartburn), others were rather farfetched, claiming that “coffee poisoning” was linked to poverty, insanity and premature death and that abstinence could cure blindness and boost life expectancy. Reports also perpetuated the discourse of the “failing housewife,” particularly when figures on coffee drinking amongst children were published in 1914, which “proved” that many young people were addicted to coffee and, therefore, hampering the strength of the nation. Leading figures, such as health reformer Are Waerland and teacher Dr Henrik Berg, also came forward to promote the “perils” of coffee consumption through public lectures and books. Berg (Citation1917) likened coffee to a famous sculpture of St Göran and the dragon, coffee being the dragon that needed to be slayed in order to save the Swedish people from harm.

All sorts of suggestions were put forward in the Riksdag on how to combat kaffemissbruk, from replacing morning coffee with porridge or milk at one end of the spectrum to a total ban on coffee in public establishments at the other. More nuanced proposals included investing in a healthy, stimulating “folk drink” to compete with coffee, introducing restrictions on coffee in public places and promoting coffee substitutes – caffeine-free drinks that imitated coffee (Johannisson Citation1991). Shrewd marketers had been closely following such debates and quickly latched onto the notion of coffee substitutes, seeing an opportunity to launch a new range of products onto the Swedish market. Although coffee substitutes had existed in Sweden since the mid-eighteenth century, these were homemade solutions and had never been commercially manufactured before. However, fueled by daily press reports on “the caffeine danger,” the public were extremely conscious of their civic responsibility to stay healthy. Thus, when new surrogates appeared advertised as healthy alternatives to coffee, they were rapidly embraced. Central to this successful sales drive was the lack of advertising regulations in Sweden at the time, which enabled bold claims to be made about the surrogates’ health benefits. These claims drew upon tried-and-tested methods of using (pseudo)science to advertise products, dating back to the mid-nineteenth century.

(Pseudo)science and the Swedish advertising market

The Great Exhibition of 1851 is often seen as the major impetus for the introduction of (pseudo)science into advertising. Displays of the latest scientific and technological innovations inaugurated a new way of seeing things and fashioned a mythology of consumerism, which quickly spread across Europe (Richards Citation1990). From this date onwards, advertisements for old products started to emphasize their improved scientific processes or health benefits, while advertisements for new products began to foreground their scientific or medical origins (Loeb Citation1994, 10). However, at the same time, these products were surrounded with a deliberate air of mystique, which turned them into magical elixirs (ibid, 6).

This practice increased throughout the nineteenth century as goods became branded and food manufacturers recognized their privileged position as knowledge shapers (Church Citation2000, 632). Advertisements began to incorporate a combination of statistics, infographics, buzzwords, technical descriptions and testimonials from doctors and scientists to produce narratives of health and wellbeing (Eriksson and O’Hagan Citation2021). These narratives became key in differentiating products from competitors and building consumer trust, even if the claims made were false or dubious at best. Through this marketing, the public gained a new idea that certain food products could be beneficial for them and their families and were encouraged to buy them, even if they did not fully understand what those supposed benefits were.

Concerned that the introduction of (pseudo)science to food advertising built upon the earlier fraudulent marketing of quack medicines, many countries sought to introduce legislation to protect consumers. The US established the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906, while the UK followed one year later with the Public Health (Regulation as to Food) Act. Sweden, however, remained unregulated for much of the twentieth century due to the unique setup of its advertising market, which was controlled and influenced by a cartel agreement between the Association of Swedish Advertising Agencies and the Association of Swedish Newspaper Publishers (Åström Rudberg Citation2019). Although the cartel played an active role in creating, shaping, propagating and debating regulatory regimes of advertising, it had no interest in restricting false or misleading advertising (Funke Citation2015).

Cartel regulations dictated that advertisements could only be placed by certified agencies who were financially stable with an established customer base and experienced leadership. Thus, in order to market a product, companies had two choices: approach newspapers directly or employ an advertising agency. The agency was responsible for all contact with the newspapers and worked on a commission of roughly 15–20% per advertising space (Arnberg Citation2019). This meant that they earnt money every time an advertisement was published, which incentivized them to publish the same advertisement as many times as possible in different newspapers (Åström Rudberg Citation2019, 53)

Throughout the 1920s, Swedish retail and wholesale organizations put forward proposals to regulate marketing practices, but the cartel deemed these as a potential threat to long-term economic interests and they were ignored (ibid, 93). Under mounting pressure, a new law was agreed against disloyal competition in 1931 (and updated in 1942), but it failed to have an impact on market behavior because of its narrow scope, limited applicability and vague statutes, as well as prosecutors’ lack of interest in applying the legislation (ibid, 94). While laws were passed in the 1940s to regulate pharmaceuticals and pesticides, food marketing was not properly regulated until the Market Practices Act of 1971.

Given the complexities of the Swedish advertising market, we can see how, at the time of the great coffee debate, the lack of regulations on false marketing enabled companies to draw upon a range of linguistic and visual cues to create a buzz around coffee surrogates and their assumed health properties. Postum excelled in this area, having had over thirty years’ experience in the US. Thus, the company thrived in the new unregulated context of Sweden, able to draw upon many of the marketing techniques that it had previously been using across the Atlantic.

Postum in Sweden

Postum was a US coffee substitute made of roasted wheat bran and molasses and created in 1895 by C.W. Post of the Postum Cereal Company. Post had developed an interest in dietetics when he was a patient at the Battle Creek Sanitorium operated by Dr. John Harvey Kellogg (Zimmerman Citation1945). Believing that caffeine was a poison that caused physiological, developmental and moral deficiencies, he sought to develop a drink that would help consumers recover from coffee abuse and improve their health within just ten days.Footnote2 Postum was an instant success and, by 1905, it had accrued more than $10 million in capital. This was, in no small part, down to the $400,000 that the company spent on advertising per year (ibid).

Initially, Post took out advertisements with the C.H. Fuller Advertising Agency in Chicago, all of which he wrote himself, but in 1903, he decided to set up his own in-house advertising agency (ibid). Postum’s advertisements made strong use of scaremongering language, which took advantage of the public’s fascination with contemporary science and medicine to fuel anxieties around caffeine (O’Hagan Citationn.d.). This strategy was effective and, by 1906, the company had grown enough for a branch to be set up in the UK under the Grape Nuts Company Ltd subsidiary (Zimmerman Citation1945). As regulations on false advertising were tightened in the US over the next decade and sales began to fall, Postum continued to focus its attention on Northern Europe, expanding into Germany, Holland and then Sweden at the height of the coffee abuse debate in 1926.

Postum was distributed in Sweden by the general agent AB Hugo Österberg – a Stockholm company that was set up in 1910 and specialized in American imports. The company also imported other Postum Company products (such as Grape Nuts and Post Toasties), as well as Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, Campbell’s soup, Rumford baking powder, Jell-O, Welch’s tomato juice, Certo pectin, Ivory soap and Maxwell House coffee. It would later add British imports to its inventory, including HP sauce.Footnote3 AB Hugo Österberg employed its own in-house marketing team who were responsible for producing all advertisements for the products that they distributed. While inspiration was taken from their US counterparts in terms of content and themes, all Swedish advertisements were designed specifically with a Swedish audience in mind. So confident in its abilities, the company took out a full-page advertisement in Svenska Dagbladet in Citation1933 [7 October] to promote its marketing team, outlining their experience and how “clever advertising of strong goods always pays off,” accompanied by the photo and signature of company founder Hugo Österberg. A Citation1947 advertisement for an advertising job at the company (also in Svenska Dagbladet) gives some indication of what was expected of team members:

Tasks: creating ideas for advertisements and printed matter, design of layout and text, as well as general advertising work. Previous experience at an advertising agency or advertising department required. Special preference for those who speak English

Through their highly skilled team and effective marketing campaigns, AB Hugo Österberg ensured that Postum quickly outsold its competitors, growing to become the biggest coffee substitute in Sweden.

Research design

This study uses a sample of 200 Postum advertisements published in Svenska Dagbladet between 1926 and 1940. These years mark the date that Postum was first launched onto the Swedish market and the date that debates about kaffemissbruk in the Riksdag and national press started to subside, which brought about a decrease in coffee substitute advertisements. Founded in 1884, Svenska Dagbladet is one of Sweden’s largest newspapers. It is based in Stockholm and covers national and international news, as well as local coverage of the Greater Stockholm region. It began as a right-wing publication, although it has been “unbound moderate” since 1977, promoting liberal-conservative ideas in terms of market economy. During the time that the Postum advertisements under study were published, the newspaper attracted a largely middle-class audience, although some of its readers came from the skilled working classes. Svenska Dagbladet has a fully searchable online newspaper archive (https://www.svd.se/arkiv), which enabled the advertisements to be collected through a manual search of “Postum” and the date criteria “1926–1940.” While this search initially brought up 396 advertisements in total, repeated advertisements were discounted from the dataset, reducing the final number to 200.

shows a breakdown of the collected advertisements by year. As to be expected, there is a large number of advertisements in the first year of Postum’s existence, with the figure generally remaining steady over time. There are also peaks in 1933 and 1939, perhaps due to a motion passed in the Riksdag to increase duty on coffee to finance unemployment and the introduction of coffee rationing in response to the outbreak of World War Two, respectively. These increases show how AB Hugo Österberg kept up-to-date with current affairs, keen to capitalize upon anything that might affect the selling of coffee and use a push in marketing to attract new consumers.

Table 1. Breakdown of collected postum advertisements by year.

Specifically, the study seeks to answer the following questions:

How did Postum use their advertisements to exploit the public’s growing fears around coffee and frame itself as a viable substitute that was essential for good health?

How were these fears exploited through the use of language and other semiotic resources and embedded in broader medical and scientific knowledge in order to appear credible?

How did the target of these fears change over time from 1926 to 1940?

To address these questions, the collected advertisements are analyzed through multimodal critical discourse analysis (MCDA). MCDA provides a systematic way to study the co-deployment of language and other semiotic resources in texts and how they shape what we do, how we think and how we experience the world (Ledin and Machin Citation2018, Citation2020). Specifically, it can help uncover the types of identities, actions and circumstances that are foregrounded, abstracted or concealed in texts through particular visual and verbal devices, thereby pointing to their broader ideological and political consequences (Machin Citation2013, 352). In the context of this study, the analytical tools of MCDA can help bring to light how Postum overexaggerated scientific and medical knowledge of caffeine in order to convince consumers that the product was necessary to safeguard health.

My approach to MCDA draws particularly on the work of Ledin and Machin (Citation2018, Citation2020) and concerns the following key elements:

language (e.g., vocabulary, grammar, use of metaphor, rhetoric);

image (e.g., people, actions, perspectives, angles, distance);

color, particularly meaning potentials in terms of emotions, attitudes, and values;

typography, especially the cultural connotations of certain typefaces;

texture and materiality in terms of their physical and symbolic meanings;

layout and composition, made up of salience, framing, coordination, and hierarchies.

Crucial to MCDA is the concept of “modality,” understood as the truthfulness and reliability of a message (Machin and Mayr Citation2012). When exploring Postum advertisements, modality can be assessed through the presence or absence of modal verbs (e.g., may, will, must) and expressions (possible, probable, likely), the use of adverbial intensifiers (e.g., very, most, remarkably), the causality between graphic elements, the symbolization of specific shapes, and the general orientation of text and image. Modality is, thus, a way to assess the validity of the arguments put forward in Postum advertisements. As advertisements work as part of a wider dialogue with the social world, the MCDA will also be embedded in first-hand evidence from historical newspaper articles, parliamentary debates and medical and scientific journals in order to provide necessary context to aid interpretation (cf. O’Hagan Citation2019).

The collected advertisements were split into groups based on recurring patterns in their arguments and their use of language and other semiotic resources. This process revealed that early advertisements (1926–1928) targeted the dangers of caffeine on a broad level, generally scaremongering rather than focusing on one particular health issue. Once Postum was established on the Swedish market and built a consumer base, this strategy then changed, with advertisements now targeting three specific problems: neurasthenia, insomnia and digestive disorders. These three topics remained unchanged from 1928 to 1940. shows a breakdown of the collected advertisements by theme.

Table 2. Breakdown of collected postum advertisements by theme.

In what follows, a selection of prototypical advertisements representative of the above themes will be analyzed. Their verbal and visual strategies, as well as the arguments made, are reflective of those that frequently reoccur across the collected advertisements and are supported by supplementary evidence from the broader dataset. Overall, the study reveals how Postum advertisements cleverly tapped into discourses of wellbeing, morality and productivity, moving the product far beyond its role as a drink into a provider of a particular way of life – a “healthy” way of life that was supposedly fundamental to the future integrity of Sweden.

Establishing the caffeine danger, 1926–1928

When Postum launched onto the Swedish market in 1926, it immediately embarked upon an aggressive advertising campaign centered around the dangers of coffee and the threat that its regular consumption posed to one’s health. Although the arguments made had some medical and scientific rationale, they were often overinflated to scare consumers into breaking their daily habit of drinking coffee and switch to Postum instead. Furthermore, these early advertisements tended to incorporate as many issues related to caffeine as possible – often echoing debates in the Riksdag and the popular press – in order to cast a broad net over consumers and retain their interest. Right from the beginning, AB Hugo Österberg ensured that Postum formed alliances with reputable department stores, such as NK, Bröderna Dahl, Wikanders and Herman Winberg, offering daily demonstrations and free samples so as to increase the validity of the product and spread its message directly to in-store customers.

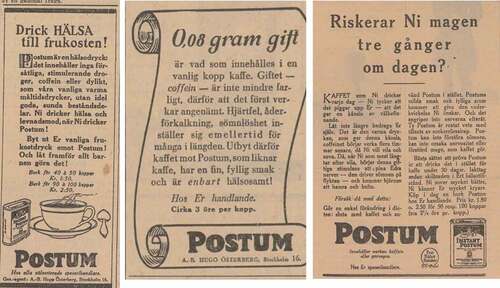

In this early stage of marketing, the Postum advertisements rely largely on persuasive linguistic strategies, including rhetorical questions, collective pronouns and value-laden language, to build credibility. Direct forms of address, such as “Do you want to prevent the harmful effects of coffee?” “Are you looking for a drink that won’t make you ill?” or “Are you risking your stomach three times a day?” () leave little room for doubt that coffee is dangerous and that it is necessary to find an alternative if consumers want to stay healthy. Moreover, specific words like “risk” and “prevent” create a dichotomy between “responsible” and “irresponsible” citizens (O’Hagan Citation2021a), generating a sense of guilt by suggesting that those who do not drink Postum may fall ill and, therefore, place a burden on the state. In addition, statements like “We must stop using hot drinks that contain the harmful ingredient caffeine” employ the personal pronoun “we” to build a sense of camaraderie and suggest that getting rid of coffee is a collective mission for the good of the Swedish nation.

Figure 1. Establishing the caffeine danger. (a) Drink health for breakfast Svenska Dagbladet, 11 March 1926, p. 5. (b) 0.08 grams of poison … Svenska Dagbladet, 15 October 1926, p. 10. (c) are you risking your stomach three times a day? Svenska Dagbladet, 8 March 1928, p. 7.

Postum also makes all sorts of general, bold claims about health and wellbeing: that the product will give customers “clearer eyes,” “fresher skin,” “a better appetite,” “youth,” “fresh energy” and a “sense of humor,” protect them from “headaches,” “arteriosclerosis,” “bad stomachs,” “damaged nerves,” “insomnia” and “neurasthenia,” and increase their “work ability.” Postum even intrudes into social relationships and homelife, stating that it can solve “disputes at home” and restore “home comfort,” which is “ruined” by coffee. It argues that coffee is responsible for “stray words” because it “upsets the equilibrium of a modern person.” These assertions are squarely aimed at women who were seen as responsible for maintaining household harmony (Loeb Citation1994), while the emphasis on “modern” is a subtle nod to the dangers of women’s emancipation and their move away from traditional roles in Swedish society. As Eklund (Citation2022) shows in his study of discussions around coffee abuse in the Swedish popular press during this period, the fight against coffee became conflated with a general fight against modernity, with coffee standing in as a metonym for modern life. For many, coffee itself was not the problem, but rather what it represented in terms of people abandoning traditional ways of life in favor of mass society, urbanism and rationalism. Similar notions are at work in such statements as “Modern life takes up every ounce of our energy. Don’t waste time with nerve-wracking caffeine drinks,” which suggest that abstaining from coffee will improve people’s ability to cope with everyday life.

Exploiting the debates in both the Riksdag and popular press about “morning coffee” needing to be eliminated (Eklund Citation2022), AB Hugo Österberg constantly tells consumers to “drink health for breakfast” (). Although the act of “drinking health” overexaggerates the potentials of Postum, the use of the imperative leaves little room for maneuver in forming a counteropinion. The constant reference to Postum being a “health drink” also operates in a consonant manner, representing an empty buzzword that is used to construct a halo of health around Postum (O’Hagan Citation2021b). “hHealth drink” is a buzzword that appears frequently in early twentieth-century advertisements across a range of beverages from radioactive water to fruit salts, thereby demonstrating how brands colonize, shape and remarket specific words time and time again to increase their competitivity and financial gain. At no time do the advertisements explain exactly what Postum is or its main ingredients; the closest they come are descriptions of the product as a “coffee-like drink without the dangerous effects of caffeine” or “a coffee-like drink with no insidious stimulant drugs.” It is somewhat ironic that, in wanting to disassociate itself from coffee, Postum emphasizes its similarities to coffee. We see this irony also in the rare images that appear in these largely textual advertisements, which show steaming cups of freshly brewed Postum. Its visual similarity with coffee implies that Postum looks and even tastes like coffee, but, unlike coffee, is good for your health. Similar textual and visual arguments can be found in early advertisements for margarine, which positioned itself as a healthy alternative to butter (O’Hagan Citation2022a).

Some advertisements go even further with their insistence on the dangers of coffee, labeling the drink as a “poison” and warning customers that coffee is “a dangerous habit” and they should drink from “nature’s own well of health” rather than “poison stores.” This stark contrast between the life-giving beauty of nature (e.g., Postum) and the dangerous, artificial poison (e.g., coffee) is powerful, even if the claim is false and plays down the fact that Postum is created through a relatively complex manufacturing process and is, therefore, not natural. We see this in , which states that “0.08 grams of poison is what is in a regular cup of coffee” and that “the poison – caffeine – is no less dangerous just because it seems pleasant at first.” The advertisement goes on to claim that, over time, caffeine causes “heart defects, atherosclerosis, insomnia” and that the solution is to switch to Postum, which is “only healthy!” The choice to print the advertisement on a rolled-out scroll is significant as it immediately connotes ancient mysticism and alchemy, thereby imbuing Postum with the status of a magical elixir and increasing its “truth value” (Ledin and Machin Citation2018, 208).

Segmenting the caffeine danger, 1928–1940

While the Riksdag and popular press tended to focus on the dangers of coffee to women and children, AB Hugo Österberg recognized the benefits of appealing to all demographics of the market in order to increase Postum’s impact and uptake. Consequently, once the brand had successfully caught the attention of the Swedish population with its scaremongering marketing campaign upon launch, AB Hugo Österberg set about creating a segmented market based around three popular health concerns in the country: neurasthenia, insomnia and digestive disorders. A similar strategy was adopted by the British brand Virol who focused on malnutrition, constipation and anxiety in their advertisements throughout the 1920s and 1930s (O’Hagan Citation2021a).

Postum as a cure for neurasthenia

Throughout the early twentieth century, a constant topic in both the Riksdag and the popular press was the link between coffee and neurasthenia. Doctors also frequently warned that coffee was an instigator of neurasthenia and led to anxiety, stress and depression (Lillestøl and Bondevik Citation2013). Neurasthenia was a term popularized by neurologist George Miller Beard in the late nineteenth century to describe a condition of nervous exhaustion in response to the stresses of modernity. It quickly became seen as a “prestige disease” associated with overworked middle-class men who led busy lifestyles and had active minds (Johannisson Citation1990; Gijswijt-Hofstra Citation2005). Until at least the mid-1930s, neurasthenia continued to be used as a “one-size-fits-all” diagnosis term in Sweden (Pietikainen Citation2007). AB Hugo Österberg was, thus, quick to take note of this and use it to its advantage.

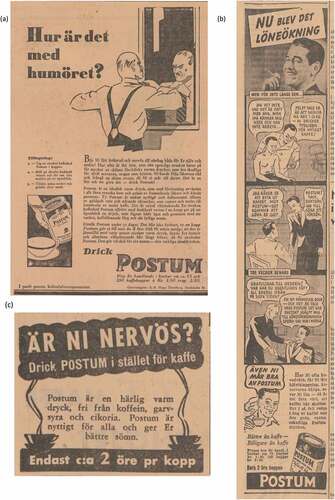

The widespread belief that neurasthenia only affected men is reflected in Postum advertisements, which show images of male figures in smart suits in their offices or at home looking distressed. The advertisements target readers directly with bold headlines that tap into their insecurities: “Do you feel worried?” “Are you nervous?” “Are you feeling down?” In addition to the rhetorical questions, readers are provided with supposedly factual statements, such as “your worries increase with caffeine” or “caffeine is bad for your nerves.” Although these statements carry an element of truth, they are not supported by references or testimonials. Furthermore, they imply that all nervous disorders are caused by coffee and discount any other possible reasons. Nonetheless, the use of the direct pronoun “you” and value-laden language such as “bad” is eye-catching and likely to encourage readers to engage further to find out how they can “protect” themselves. A case in point is , which is headlined “How’s your mood?” and shows a man tying his tie in front of the hallway mirror, presumably before going to work. His reflection in the mirror shows a scowling face, with eyebrows knitted together and jaw clenched, implying that he is unhappy. The accompanying body of text asks the question “Do you get easily irritated or nervous to the point of discomfort to yourself and others?” before blaming this on “treacherous warm drinks that are harmful for the nerves.” Readers are then advised to “follow doctors’ advice” and “drink Postum!” which is “healthy” and “wholesome.” Here, Postum is presented as a wonder cure for neurasthenia that has supposedly been approved by the medical profession, which increases the effectivity of its message (cf. O’Hagan Citation2021a).

Figure 2. Postum as a cure for neurasthenia. (a) How is your mood? Svenska Dagbladet, 10 April 1931, p. 5. (b) Now there’s a payrise! Svenska Dagbladet, 11 March 1938, p. 5. (c) are you nervous? Svenska Dagbladet, 21 June 1935, p. 17.

AB Hugo Österberg also frequently used cartoon strips to demonstrate Postum’s “curative” abilities. Cartoons were a clever way of masking advertisements within newspapers, meaning that they could potentially reach a higher readership and their message be transferred covertly. They were a common marketing strategy in Sweden at this time (cf. Eriksson and O’hagan Citation2021). Postum’s cartoons all tend to follow the same format. They feature titles, such as “Now I feel calm again” or “Dad is never down again” and contain three vignettes: the first presenting a problem (nerves), the second offering a solution (Postum) and the third showing the result (a cure). The result could also extend beyond health, however, and lead to positive life changes, such as a reconciliation between spouses, a job promotion or top marks in an exam. We see this in the cartoon in entitled “Now there’s a pay rise!” accompanied by a photograph of a winking man smoking a cigarette. The caption below, which states “But not long ago … ,” sets the scene, leading into the first vignette of a man – who we suppose is a cartoon version of the man in the photograph – being examined by a doctor. He tells the doctor that he “feels down” and “can’t work” to which the doctor responds that his “nerves are shot” from drinking too much coffee. In the second vignette, the doctor advises him to replace coffee with Postum. In the third vignette (marked three weeks later), a clear change has overcome the man; he looks happier and is sitting upright in his chair. His colleague is congratulating him on working so hard and having so much energy. The man explains that he is a “new person” thanks to Postum and that the drink even helped him get a pay rise from his manager. This imaginary scenario demonstrates how AB Hugo Österberg capitalizes upon consumers’ vulnerabilities, overpromising Postum’s benefits in order to frame the product as not just a health choice, but also a lifestyle choice.

In addition to the use of images and cartoons, AB Hugo Österberg also uses shapes, symbols and colors in advertisements for dramatic effect. , for example, is dominated by a large black cloud – a signifier of evil, pain and darkness (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006, 348) – and contains the headline “Are you nervous? Drink POSTUM instead of coffee.” From the cloud shoots two bolts of lightning, which further connotes feelings of discomfort and danger. However, the bolts’ interconnection with the teacups below offers a shift in meaning (Ledin and Machin Citation2020, 182) when the image is read from the bottom up, thereby transforming the lightning into soothing steam and changing the tone of the advertisement from negative to positive. Read in this way, the cloud also transforms into a thought bubble, toning down the direct question “Are you nervous?” and giving the reader more time to reflect over their answer. Together, these elements suggest that Postum has the ability to change one’s mood and mental state, which is further emphasized by the text framed between the cloud which describes it as a “lovely warm drink free from caffeine, tannin or chicory” that is “healthy for everyone.”

Postum as a cure for insomnia

Throughout the kaffemissbruk debates of the early twentieth century, insomnia was often talked about in the Riksdag and Swedish popular press. This “threat to man’s natural sleep cycle” (Eklund Citation2022) caused by coffee was seen as a problem that affected both genders: women who, as leaders of the sobriety movement, often served coffee at their late-night committee meetings and men, who drank coffee late at night, despite having to get up early for work. While insomnia is mentioned in Postum advertisements from the product’s launch in 1926, it does not become a major theme until around 1935. Prior to this date, “insomnia,” or “sleeplessness” as it was more often called, was considered a symptom of neurasthenia. However, as neurasthenia stopped being used as a diagnostic category, insomnia gradually became recognized as a condition in its own right.Footnote4 Doctors started to promote the improvement of “sleep hygiene” through lifestyle modifications, one of which was avoiding coffee (Smiley, Gould, and Melby Citation1930). In Sweden, interest in insomnia extended beyond the medical sphere following the publication of Vilhelm Moberg’s novel Sömnlös (Sleepless) in 1937 about the “existential and relational distress of insomnia” (Bäckryd Citation2021). Always keen to keep up with the latest in medical (and cultural) knowledge, AB Hugo Österberg shifted its focus increasingly toward insomnia in its advertisements.

Just as we saw with the advertisements focused on neurasthenia, insomnia advertisements directly address consumers with bold rhetorical questions in their headlines, such as “Are you sleepless?” “Do you have bad sleep?” or “Was it hard for you to sleep last night?” These types of questions serve to engage readers and suggest that Postum cares about their wellbeing and wants to help. Once readers are drawn in, the follow-up statements tend to be rather dramatic: “Sleepness nights. How long they are! How terrible the next day! Why drink coffee? A poisonous stimulant that prevents sleep.” Here, the order of the short sentences connotes logic and establishes a “causality” (Ledin and Machin Citation2018, 165) between insomnia and coffee, suggesting that there is no other possible reason why a person may struggle to sleep. These statements are further strengthened by supporting images, which show hands reaching out to the bedside table to check the time or figures lying awake in bed and looking frustrated. The advertisements end by offering a solution to this problem: “buy Postum!” Apple (Citation1995, 19) describes this technique as the “negative appeal” because it emphasizes the dangers to one’s health if coffee is not replaced with Postum (see for an example).

Figure 3. Postum as a cure for insomnia. (a) Was it hard for you to sleep last night? Svenska Dagbladet, 2 April 1931, p. 14. (B) Those endless sleepless nights Svenska Dagbladet, 17 January 1939, p. 13. (c) Good sleep makes me fresh Svenska Dagbladet, 10 January 1940, p. 7.

Other insomnia advertisements follow the same cartoon format that was used for neurasthenia, indicating how a person’s life suddenly changes for the better once they drink Postum. However, even more common than this is the use of “before” and “after” vignettes. These vignettes tend to show a person before and after taking Postum, their physical features clearly showcasing the marked changes that the product brings about. Such an example can be seen in . The top of the advertisement shows a man lying awake in bed; his forehead is wrinkled and he is frowning, while a speech bubble states “These endless sleepless nights.” This is in contrast to the bottom of the advertisements, which shows the same man sleeping soundly with a content look on his face. Outside of the frame but overlapping his hand is a jar of Postum, suggesting that this is the reason why he is sleeping better. This composition fits with Kress and van Leeuwen’s (Citation2006, 181) unreal/real theory, which states that the top of a page tends to show a generalized overview of a scenario, while the bottom provides informative and practical knowledge. Coupled with the man’s lack of eye contact, this format positions viewers as onlookers who watch a development over time and are made to reflect on its relevance to their lives. The text in between aids comprehension by informing potential consumers that if they “lie awake at night and cannot sleep,” then Postum is the “ideal go-to-bed drink” for them. It also claims that the drink is “calming and sleep-giving” because it “puts the blood into circulation and draws it away from the head”—a medically inaccurate statement which, nonetheless, sounds credible.

Just the “after” image is shown in other advertisements in order to depict the positive effects that Postum will have on a person. We see men and women jumping out of bed excitedly in the morning, engaging in morning gymnastics (a common Swedish practice at this time), walking to work with a spring in their step or talking animatedly on the phone. Here, modality draws upon interpersonal, rather than ideational, meaning to convey truthfulness, serving to represent ideas that shape readers’ understanding of truths rather than express absolute truths (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006, 154). In other words, Postum’s functions are extended beyond its role as a “healthgiver” to something that will change a person’s entire life. This is apparent in , which shows a young man dancing dressed in his pajamas and slippers. The accompanying cup of Postum and the headline “good sleep makes me fresh” leaves no doubt that this is early morning and that he has slept well thanks to Postum. The steam rising from the cup has a visual similarity to music notes, further accentuating the positive tone of the advertisement, while the man’s direct gaze at the viewers and his raised fist serve as statements of intent, encouraging them to try Postum for themselves (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2006, 119).

Postum as a cure for digestive disorders

Another major focus of the kaffemissbruk debate in both the Riksdag and the popular press was the link between coffee and digestive disorders. While the effects of coffee on the gastrointestinal system had been known for centuries (see Porciúncula et al. Citation2013), greater attention began to be paid to the issue in the early 1930s when gastroenterology became an established subbranch of medicine, leading to the introduction of specific university programmes and specialized hospital units. This paved the way for increased research in the area and the invention of numerous important diagnostic instruments, including the semi-flexible gastroscope, which advanced the examination, diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal disorders (Kirsner Citation2004). Following these innovations and discussions closely, AB Hugo Österberg began to introduce a focus on digestive disorders in its advertisements, encouraging consumers to ditch “dangerous” coffee, which caused heartburn, indigestion, gastritis and even stomach ulcers. Unlike neurasthenia and insomnia, digestive disorders were physical, rather than mental, and were likely to affect everybody at some point in their lives. Furthermore, as gastroenterology was constantly in the press at this time due to frequent scientific breakthroughs, consumers had a basic understanding and interest in the topic. Both aspects, thus, made it easier for Postum’s messages on digestive disorders to resonate with the Swedish population.

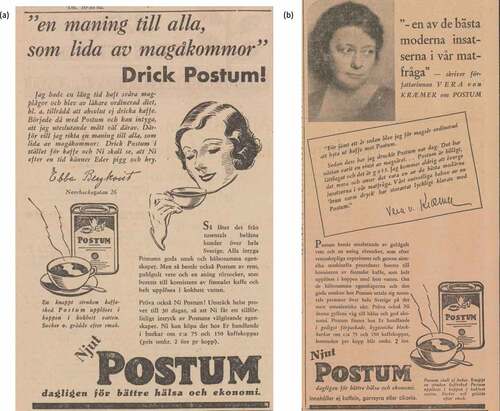

The “trendiness” of gastroenterology and the Swedish public’s fascination with the topic may also explain AB Hugo Österberg’s advertising strategy, which varies considerably to its other Postum advertisements that targeted neurasthenia and insomnia. In this case, they rely on two techniques only: the consumer testimonial and the celebrity endorsement. Both techniques follow the same format, with the consumer or celebrity outlining how Postum has cured their stomach problems. In these testimonials/endorsements, the voices of the doctors are cleverly masked through depersonalized verbs (e.g., “I was advised to exchange coffee for Postum”), which creates the impression that the consumer has “role model authority” (van Leeuwen Citation2008, 187) and gives them a false sense of control. This is emphasized by the description of each consumer/celebrity as “one of our Postum friends,” which indicates trust and camaraderie.

We see such an example in , which shows the testimonial of Ebba Bergvist. The headline states, “A call to everyone who suffers from stomach upsets” and underneath is Ebba’s personal story of how she had stomach pain for many years, but switching to Postum (on her doctor’s advice) immediately took it away. The indented paragraph and use of italics connotes that Ebba’s testimonial is a written letter; Barker (Citation2009) has traced these types of testimonial letters back to late Georgian medical advertising, arguing that they mimic the language and rhetoric of court witness statements and affidavits, which gives them a high level of credibility. In the context of the early twentieth century, these testimonials also build credibility by creating a sense of community and encouraging other consumers to gain confidence in a particular product because of the collective experience around it (Loeb Citation1994, 143). Credibility is further granted by the inclusion of Ebba’s signature and her full name and address. An investigation of census records and street directories indicate that Ebba did not actually exist. However, unknowing readers are likely to assign her status because she stands in for the typical everyday contacts who would have provided word-of-mouth reputations when towns were smaller and populations were less diverse (Barker Citation2009, 396). The caricature of a woman drinking a cup of Postum alongside the testimonial also encourages readers to link the words with the image and assume that it is Ebba, which further frames the statement as honest, provides reassurance that Postum works and legitimizes its use for those unconvinced of its benefits.

Figure 4. Postum as a cure for digestive disorders. (a) a call to everyone who suffers from stomach upsets Svenska Dagbladet, 12 January 1934, p. 10. (b) One of the best modern efforts in our food question Svenska Dagbladet, 15 October 1934, p. 10.

A similar example can be seen in , this time featuring the endorsement of famous author Vera Von Kraemer. Again, the headline is attention-grabbing, with the claim that Postum is “one of the best modern efforts in our food question,” while the endorsement from Vera below stating that her stomach ulcer has disappeared thanks to Postum leaves no room for doubt. Like with the Ebba example, Vera’s signature grants authenticity. However, in this case, the authenticity is furthered by the rectangular border around the endorsement (i.e., visually resembling a postcard), the photograph and Vera’s celebrity status. The early twentieth century was marked by a burgeoning cult of celebrity, which led manufacturers to shift toward consumer-centered advertising using famous figures to associate their products with new ideas (Schweitzer Citation2004). This shift was reflective of a broader change in networks of trust across Victorian society, with people moving away from “thick” networks of friends and family to “thin” networks based around institutions and authority figures (Putnam Citation2000). What is interesting here, however, is that no scientists or doctors are used in any of Postum’s endorsements. Endorsements come instead from Johan Lindström Saxon, author and major advocate of vegetarianism; Ebbe Lieberath, the leader of the Boy Scouts; Hugo Engelbrecht, military veteran; and even a number of well-known pastors and professors. This absence, thus, suggests that Postum was not scientifically or medically endorsed. Nonetheless, science features majorly in the advertisement, with claims that Postum was created “after scientific experiments and through ingenious mechanical procedures.” There is a certain irony in this statement, given that “modernity” was a major reason why coffee came under heavy scrutiny. However, as Loeb (Citation1994, 78) notes, these types of statements make consumers assign brands status on the grounds that they know something that they do not and, therefore, are likely not to question the information presented.

Conclusion

Throughout the early twentieth century, the widespread growth of coffee drinking in Sweden led for calls by health reformers, doctors and scientists to implement measures to curtail this kaffemissbruk. Debates about the dangers of coffee took place in the Riksdag and trickled out into the popular press. It was not long before canny manufacturers saw an opportunity to capitalize upon this, introducing coffee substitutes onto the Swedish market. One of the most popular brands was the roasted wheat bran drink Postum. Already commercially successful in the US and UK, Postum was distributed by AB Hugo Österberg who used their in-house marketing team to draw upon tried-and-tested US methods to convince the Swedish population to replace coffee with Postum. The lack of regulations on false advertising in the country enabled them to make outrageous claims that would not have been possible elsewhere, and they did so through a range of techniques, including cartoon strips, before and after vignettes, consumer testimonials, celebrity endorsements and the creative use of symbols, shapes, colors and images, as well as persuasive linguistic strategies like rhetorical questions, collective pronouns and direct address.

Upon its launch in Sweden in 1926, Postum advertisements were very much focused on the general dangers of coffee, framing it as a poison that caused a wide range of medical issues. These scaremongering techniques served to catch consumers’ attention and, once caught, more targeted campaigns were then produced that centered around neurasthenia, insomnia and digestive disorders – all in keeping with major medical/scientific discussions of the day. All three conditions were presented as separate causes of coffee addiction, despite the fact that there was a clear link between them. This enabled AB Hugo Österberg to cast a net around a broad range of consumers, even though public debates often centered around the dangers of coffee to women only. Furthermore, AB Hugo Österberg framed each health issue as something caused by coffee and coffee only, thereby discounting the numerous other reasons why a person might feel anxious, be unable to sleep or have stomach pain. Although there were elements of truth in all the claims that AB Hugo Österberg put forward, they never relied on actual evidence in the form of doctor/scientist testimonials, infographics and statistics, which were a common feature of other advertisements at this time. This is likely because, while the negative effects of caffeine could be corroborated, no studies existed on the nutritional benefits of Postum itself.

Contrary to the debates in the Riksdag and popular press about the dangerous effects of caffeine on children and the need for mothers to protect them, children are surprisingly not a major focus of Postum advertisements. There are some scant mentions that children should be trained with good health habits, as well as warnings that coffee can hinder growth and should, thus, be avoided by all under 15s, but Postum does not go beyond this. This is in stark contrast to Great Britain, where cursory research shows that Postum advertisements were predominantly focused on children’s health. This warrants further study, but may be tied up to Britain’s National Fitness Campaign at the time in response to malnutrition, and showcases how Postum adapted its strategies by country to play upon national anxieties and remain relevant to consumers.

In 1929, the Riksdag finally demanded an investigation into feasible measures to clamp down on coffee misuse. However, by the end of the 1930s, interest gradually fizzled out and nothing came of the investigation. According to Lindgren (Citation1993), there are multiple reasons for this, including competition from the alcohol issue, no common action programme that could be agreed on, disinterest from the sobriety movement, the state’s own financial interest, difficulties in enforcing violations and the attachment of coffee to other contemporary problems. This growing disinterest is also reflected in Postum advertisements, which decrease significantly from the 1940s onwards and focus predominantly on sleep, all mentions of neurasthenia and digestive disorders now omitted. As Sweden’s status as coffee drinkers consolidated throughout the twentieth century, sales of Postum declined until it finally disappeared from the Swedish market in the mid-1950s.

Coffee is now an integral part of the Swedish “way of life,” making those days when it posed a danger seem very far away indeed. Nonetheless, the discourses of wellbeing, morality and productivity that coffee surrogates like Postum promoted remain a central part of food marketing today, where consumers are constantly told to take responsibility for their own health to limit the burden they might place upon society. This pursuit of personal health and wellbeing as a supreme goal – or healthism (Scrinis Citation2013) – is often framed as a contemporary phenomenon, yet this study shows that it has its origins in the early twentieth century. It, therefore, emphasizes how the food industry has long exploited science and medicine to appeal to the concerns of anxious consumers, as well as how vulnerable these consumers can be to such claims. Viewing the issue from a historical perspective encourages the lay public to take a more critical stance toward their experiences of contemporary marketing practices and reflect on fuzzy scientific or medical references, thereby making better informed choices about products that are framed as indispensable for their health.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. The most notable experiment was carried out on two twins condemned to death. One was made to drink three pots of coffee per day for the rest of her life, while the other was to drink the same amount of tea. Two physicians were appointed to supervise the experiment and report its findings to the King. The experiment was a failure, however, with both doctors and the King dying before it was completed. Of the twins, the tea drinker ended up being the first to die (Sempler 2006).

2. Post also developed the breakfast cereals Grape Nuts (in 1897) and Post Toasties (in 1911).

3. Information gathered through a comprehensive study of advertisements in the Svenska Dagbladet newspaper archive.

4. The “insomniac” had emerged as a distinct pathological and social archetype in the UK and the USA in the late nineteenth century, while “insomnia” became a recognized term in 1908 following the publication of Insomnia and Nerve Strain by Henry Swift Upson. However, its widespread use in medicine did not take place until the 1930s, especially in Sweden.

References

- Anon. 1933. “Erfarenheten talar….” Svenska Dagbladet, October 7.

- Anon. 1947. “Assistent till reklamchefen.” Svenska Dagbladet, January10.

- Apple, R. 1995. “Constructing Mothers: Scientific Motherhood in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.” Social History of Medicine 8 (2): 161–178. doi:10.1093/shm/8.2.161.

- Arnberg, K. 2019. “Selling the Consumer: The Marketing of Advertising Space in Sweden, Ca. 1880–1939.” Journal of Historical Research in Marketing 11 (2): 142–164. doi:10.1108/JHRM-10-2017-0062.

- Åström Rudberg, E. 2019. “Sound and Loyal Business: The History of the Swedish Advertising Cartel, 1915-1965.” Doctoral dissertation., Stockholm School of Economics.

- Bäckryd, E. 2021. “The Pharmaceuticalisation of Life? A Fictional Case Report of Insomnia with a Thought Experiment.” Philosophy, Ethics and Humanities in Medicine 16 (1). doi:10.1186/s13010-021-00109-7.

- Barker, H. 2009. “Medical Advertising and Trust in Late-Georgian England.” Urban History 35 (3): 379–398. doi:10.1017/S0963926809990113.

- Berg, H. 1917. Om kaffemissbruket bland svenska folket. Stockholm: Norstedt.

- Burnett, J. 1999. Liquid Pleasures: A Social History of Drinks in Modern Britain. London: Routledge.

- Cesiri, D. 2022. “The Representation of Baby Food Advertisements in the UK and the US from the Late 1880s to the 1940s.” Childhood in the Past 15 (4909): 1–9. doi:10.1080/17585716.2022.2095171.

- Chen, A., and G. Eriksson. 2019. “The Mythologization of Protein: A Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis of Snacks Packaging.” Food, Culture, and Society 22 (4): 323–445. doi:10.1080/15528014.2019.1620586.

- Chen, A., and G. Eriksson. 2021. “Connoting a Neoliberal and Entrepreneurial Discourse of Science Through Infographics and Integrated Design: The Case of ‘Functional’ Healthy Drinks.” Critical Discourse Studies 19 (3): 290–308. doi:10.1080/17405904.2021.1874450.

- Church, R. 2000. “Advertising Consumer Goods in Nineteenth-Century Britain: Reinterpretations.” The Economic History Review 53 (4): 621–645. doi:10.1111/1468-0289.00172.

- Eklund, M. 2022. “Upp till allvarlig kamp mot kaffemissbruket! Kaffemissbruksfrågan i svensk dagspress 1910–1940.” unpublished undergraduate dissertation., Jönköping University.

- Eriksson, G., and L. A. O’Hagan. 2021. “Selling ‘Healthy’ Radium Products with Science: A Multimodal Analysis of Marketing in Sweden, 1910–1940.” Science Communication 43 (6): 740–767. doi:10.1177/10755470211044111.

- Eriksson, G., and L. A. O’Hagan. 2022. “Modern Science, Moral Mothers, and Mythical Nature: A Multimodal Analysis of Cod Liver Oil Marketing in Sweden, 1920–1930.” Food & Foodways 30 (4): 231–260. doi:10.1080/07409710.2022.2124725.

- Funke, M. 2015. “Regulating a Controversy: Inside Stakeholder Strategies and Regime Transition in the Self-Regulation of Swedish Advertising 1950–1971.” Doctoral dissertation., Uppsala University.

- Gijswijt-Hofstra, M. 2005. “Introduction: Cultures of Neurasthenia: From Beard to the First World War.” In Cultures of Neurasthenia: From Beard to the First World War, edited by M. Gijswijt-Hofstra and R. Porter, 1–31. London: BRILL.

- Johannisson, K. 1990. Medicinens öga: sjukdom, medicin och samhälle - historiska erfarenheter. Stockholm: Norstedt.

- Johannisson, K. 1991. “Folkhälsa: det svenska projektet från 1900 till 2:a världskriget.” In Lynchnos: Årsbok för idehistoria och vetenskapshistoria, edited by Karin Johannisson, 139–195. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Jovanovic, M. 2014. “Selling Fear and Empowerment in Food Advertising: A Case Study of Functional Foods and Becel® Margarine, Food.” Culture & Society 17 (4): 641–663. doi:10.2752/175174414X14006746101871.

- Kideckel, M. S. 2018. “Fresh from the Factory: Breakfast Cereal, Natural Food, and the Marketing of Reform, 1890–1920.” Unpublished PhD thesis., Columbia University.

- Kirsner, J. B. 2004. “Blossoming of Gastroenterology During the Twentieth Century.” World Journal of Gastroenterology 10 (11): 1541–1542. doi:10.3748/wjg.v10.i11.1541.

- Knutsson, A., and H. Hodacs. 2021. “When Coffee Was Banned: Strategies of Labour and Leisure Among Stockholm’s Poor Women, 1794–1796 and 1799–1802.” Scandinavian Economic History Review 1–23. doi:10.1080/03585522.2021.2000489.

- Koteyko, N. 2009. “‘I Am a Very Happy, Lucky Lady, and I Am Full of vitality!’ Analysis of Promotional Strategies on the Websites of Probiotic Yoghurt Producers.” Critical Discourse Studies 6 (2): 111–125. doi:10.1080/17405900902749973.

- Kress, G., and T. van Leeuwen. 2006. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge.

- Ledin, P., and D. Machin. 2018. Doing Visual Analysis. London: SAGE.

- Ledin, P., and D. Machin. 2020. Introduction to Multimodal Analysis. London: Bloomsbury.

- Lillestøl, K., and H. Bondevik. 2013. “Neurasthenia in Norway 1880-1920.” Tidsskrift for den Norske Legeforening 133 (6): 661–665. doi:10.4045/tidsskr.12.1221.

- Lindberg, J. 2018. “Det svenska hånet mot kaffe: “Medicin för de feta.” Svenska Dagbladet, January 18. https://www.svd.se/a/VRPjr/det-svenska-hanet-mot-kaffe-medicin-for-de-feta.

- Lindgren, S. Å. 1993. “Den hotfulla njutningen: att etablera drogbruk som samhällsproblem 1890–1970.” Unpublished PhD thesis., Gothenburg University.

- Loeb, L. A. 1994. Consuming Angels: Advertising and Victorian Women. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lundqvist Wanneberg, P. 2019. “The Weight Attached to Dieting: Health, Beauty and Morality in Sweden from the End of the Nineteenth Century to the Present Day.” Athens Journal of Health and Medical Sciences 6 (4): 243–260. doi:10.30958/ajhms.6-4-4.

- Machin, D. 2013. “What is Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis?” Critical Discourse Studies 10 (4): 347–355. doi:10.1080/17405904.2013.813770.

- Machin, D., and A. Mayr. 2012. How to Do Critical Discourse Analysis: A Multimodal Introduction. London: SAGE.

- Marcellus, J. 2008. “Nervous Women and Noble Savages: The Romanticized “Other” in Nineteenth-Century US Patent Medicine Advertising.” Journal of Popular Culture 41 (5): 784–808. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5931.2008.00549.x.

- Nelson, M. R., S. Das, and R. J. Ahn. 2020. “A Prescription for Health: (Pseudo)scientific Advertising of Fruits and Vegetables in the Early 20th Century.” Advertising & Society Quarterly 21 (1). doi:10.1353/asr.2020.0007.

- Nilsson, R. 2015. “När kaffet kom till staden: Uppsalabornas te- och kaffekonsumtion från 1750 til 1850.” unpublished undergraduate dissertation, Uppsala University.

- O’Hagan, L. A. 2019. “Towards a Multimodal Ethnohistorical Approach: A Case Study of Bookplates.” Social Semiotics 29 (5): 565–583. doi:10.1080/10350330.2018.1497646.

- O’Hagan, L. A. 2020a. “Packaging Inner Peace: A Sociohistorical Exploration of Nerve Food in Great Britain.” Food and History 17 (2): 183–222. doi:10.1484/J.FOOD.5.121084.

- O’Hagan, L. A. 2020b. “Pure in Body, Pure in Mind: A Sociohistorical Perspective on the Marketisation of Pure Foods in Great Britain.” Discourse, Context and Media 34: 34. doi:10.1016/j.dcm.2019.100325.

- O’Hagan, L. A. 2021a. “‘Blinded by science?’ Constructing Truth and Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Virol Advertisements.” History of Retailing and Consumption 7 (2): 162–192. doi:10.1080/2373518X.2021.1983343.

- O’Hagan, L. A. 2021b. “Flesh-Formers or Fads? Historicising the Contemporary Protein-Enhanced Food Trend.” Food, Culture and Society 25 (5): 875–898. doi:10.1080/15528014.2021.1932118.

- O’Hagan, L. A. 2022a. ‘Classifying’ Margarine: The Early Class-Based Marketing of a Butter Substitute in Sweden (1923-1933). Global Food Studies. doi:10.1080/20549547.2022.2136876.

- O’Hagan, L. A. 2022b. “All That Glistens is Not (Green) Gold: Historicising the Contemporary Chlorophyll Fad Through a Multimodal Analysis of Swedish Marketing, 1950–1953.” Journal of Historical Research in Marketing 14 (3): 374–398. doi:10.1108/JHRM-11-2021-0057.

- O’Hagan, L. A. n.d. “Welcome to Pure Food City”: Tracing Discourses of Health and Wellbeing in the Promotional Publications of the Postum Cereal Company, 1920-1925.” Journal of Historical Research in Marketing.

- Petty, R. D. 2019. “Pain-Killer: A 19th Century Global Patent Medicine and the Beginnings of Modern Brand Marketing.” Journal of Macromarketing 39 (3): 287–303. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146719865770.

- Pietikainen, P. 2007. Neurosis and Modernity: The Age of Nervousness in Sweden. Leiden: BRILL.

- Porciúncula, L. O., C. Sallaberry, S. Mioranzza, P. H. S. Botton, and D. B. Rosemberg. 2013. “The Janus Face of Caffeine.” Neurochemistry International 63 (6): 594–609. doi:10.1016/j.neuint.2013.09.009.

- Prendergast, M. 2010. Uncommon Grounds: The History of Coffee and How It Transformed Our World. New York City: Basic Books.

- Putnam, R. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Renewal of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Richards, T. 1990. The Commodity Culture of Victorian Britain. London: Verso.

- Santos, L. J. 2020. Half Lives. London: Icon Books.

- Schweitzer, M. 2004. “Uplifting Makeup: Actresses’ Testimonials and the Cosmetics Industry, 1910-1918.” Business and Economic History 1: 1–14.

- Scott, L. M. 2015. “Woodbury Soap: Classic Sexual Sell or Just Good Marketing?” Advertising & Society Review 16 (1). doi:10.1353/asr.2015.0008.

- Scrinis, G. 2013. Nutritionism: The Science and Politics of Dietary Advice. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Segal, J. Z. 2019. “The Empowered Patient on a Historical-Rhetorical Model: 19th-Century Patent-Medicine Ads and the 21st-Century Health Subject.” Health 24 (5): 572–588. doi:10.1177/1363459319829198.

- Sempler, K. 2006. “Gustav IIIs odödliga kaffeexperiment.” Ny Teknik (15 March), http://www.nyteknik.se/nyheter/it_telekom/allmant/article247458.ece

- Smiley, D. F., G. Gould, and E. Melby. 1930. The Principles and Practices of Hygiene. New York: Macmillan.

- Stendahl, J. 2016. “Reklamens historia: Från väggmålning till varumärke.” Biz Stories, 16 February, https://www.bizstories.se/foretagen/reklamens-historia-fran-vaggmalning-till-varumarke/

- van Leeuwen, T. 2008. Discourse and Practice: New Tools for Critical Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Walker, S. 2007. Style and Status: Selling Beauty to African American Women, 1920-1975. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.

- Zimmerman, S. H. 1945. 50 Years at Post Products. Battle Creek: Post Products Division of General Food Corporation.