ABSTRACT

Background: More and more children are experiencing what have been termed adverse childhood experiences. An individual's response to these stressful events determines whether or not they are considered traumatic – whereby the experience is so overwhelming that it engulfs their coping mechanisms leading to lasting negative effects on wellbeing. Notably, childhood trauma is now recognised as a global health epidemic. Physical education (PE) is a unique context whereby participation is public, and the body plays a central role. Our work with care-experienced young people (who are likely to have experienced trauma) tells us that the depth of vulnerability felt by students who have been exposed to trauma is unlikely to be fully be recognised by PE teachers. Purpose: This paper therefore seeks to enhance practitioners’ understanding of how trauma manifests and the impact it can have on children and young people's engagements in PE. It is driven by two key questions. First, why is it important for physical educators to have an awareness and understanding of trauma? Second, what principles might underpin trauma-aware pedagogies for PE? Discussion: We note how childhood trauma has been found to consistently impact neurological, physiological and psychological development. Understanding the impact of trauma, and the responses it might evoke, is beneficial for those working with/for children and young people so as to help them comprehend the underlying reasons why some children and young people have difficulties with learning, building relationships and managing behaviour. In an effort to help mitigate the impact of trauma and prevent re-traumatisation, drawing on our collective experiences of working with care-experienced youth and practitioners in PE, physical activity and sport-related contexts, we suggest that the following five evidence-informed principles might be helpful when seeking to enact trauma-aware practice: (1) ensuring safety and wellbeing, (2) establishing routines and structures, (3) developing and sustaining positive relationships that foster a sense of belonging, (4) facilitating and responding to youth voice and, (5) promoting strengths and self-belief. Conclusion: The principles we identify all point to the need for creating safe environments, shaped by consistency, positive connections and opportunities for interaction and engagement. It is not our intention, however, to suggest that there is only one way to enact a trauma-aware pedagogy, rather that an understanding of trauma may enable physical educators to ask when, and for whom, it might be best to draw on particular models in the teaching of PE, through which these principles can be applied.

Introduction

This paper seeks to enhance practitioners’ understanding of how trauma manifests and the impact it can have on children and young people's engagements in physical education (PE). It is driven by two key questions. First, why is it important for physical educators – and, more broadly, those wider practitioners who deliver school-based PE (e.g., generalist teachers, sports coaches, PE specialists) – to have an awareness and understanding of trauma? Second, what principles might underpin trauma-aware pedagogies for PE? To address these, the paper first explores what trauma is and what the immediate and long-term effects of trauma might be before identifying which groups of children and young people may be at elevated risk of experiencing trauma. The discussion is contextualised in our recent work with care-experienced children and young people (those whose family are unable to look after them and who are temporarily or permanently placed in the care of the state) both in the UK (see Sandford et al. Citation2019; Quarmby et al. Citation2020) and Australia (Cox et al. Citation2017a, Citation2017b), before we present principles – informed by this work – that could be considered when engaging with trauma-aware pedagogies. This novel paper is particularly important since there are few in the field of PE (and sport/physical activity more broadly) that examine the role of trauma in shaping children and young people's engagement and learning, nor which identify principles that physical educators could adopt to help tailor their pedagogies to better reflect the diverse needs of those who may have experienced trauma.

One notable exception here is the work of Ellison, Walton-Fisette, and Eckert (Citation2019), which does touch on such issues and examines, in particular, the potential of the Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR) model as a means of facilitating trauma-informed practice. This paper aligns with some of these ideas, but also seeks to build on them by adopting a cross-disciplinary approach informed by empirical findings from two youth-voice led studies that worked with diverse groups of care-experienced young people in different geographical contexts. Further, in a concerted effort to move away from more deficit-based language, we also choose to focus on principles that might underpin trauma-aware pedagogies within this discussion. It is important to note that while the discussion may be framed around care-experienced youth, it holds broader relevance for other groups of children and young people who may have experienced some form of trauma. This would seem to be particularly pertinent given that, at the time of writing, the COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically impacted the lives – and educational experiences – of young people across the globe. Certainly, concerns regarding the impact of prolonged lockdown on children and young people's mental health have been central to much debate in recent times (Youth Sport Trust Citation2020) as they experience a sense of loss with regard to routines and relationships.

What might be considered a traumatic experience?

In order to understand what might be considered a traumatic experience, it is first important to consider what constitutes ‘adverse childhood experiences’ (ACEs) and how these might lead to trauma. ACEs is a term used to describe a range of stressful events that children and young people, up to the age of 18 years, have been exposed to whilst growing up (Felitti et al. Citation1998). In their original study on the influence of ACEs on health in adulthood, Felitti and colleagues (Citation1998) outlined ten markers of adversity. These include those that directly affect a child, such as exposure to physical, verbal or sexual abuse and physical or emotional neglect, along with those related to household dysfunction that affect the environment in which a child grows up, for instance, parental separation, domestic violence, substance misuse, mental illness and incarceration of a family member (Felitti et al. Citation1998).

These ten markers have, more recently, been expanded in an effort to recognise the limitations of ACEs being restricted to household effects, excluding those factors evident outside of the home. Hence, Smith (Citation2018) identified additional ACEs that might have implications for overall health and wellbeing in later life. These include facing racism, witnessing community violence, living in an unsafe neighbourhood, being bullied, experiencing foster care or suffering the death of a parent, as well as having a lack of food, being exposed to consistent parental arguments, holding low socioeconomic status, showing poor academic performance, having limited social capital and being rejected by peers.

Importantly, it is an individual's response to these ACEs that determines whether they are considered traumatic or not (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] Citation2014). Fundamentally, trauma is understood to be an overwhelming experience that undermines a person's belief in the world as a good and safe place (Downey Citation2007). Trauma, defined in various ways, occurs when an individual is exposed to an experience that engulfs both the internal and external coping resources available to them, creating a sense of extreme threat that has lasting negative effects on their functioning and wellbeing (SAMHSA Citation2014). According to the World Health Organisation (Citation1992, 120) trauma may result from a ‘natural or man-made disaster, combat, serious accident, witnessing the violent death of others, or being the victim of torture, terrorism, rape, or other crime’. Trauma may therefore result from an acute, sudden and unexpected event (e.g., in the form of a traffic accident) that has potential to cause physical or emotional harm or threaten life or as a result of chronic, repeated exposure over time (e.g., in the form of ongoing childhood abuse) (American Psychiatric Association [APA] Citation2000; SAMHSA Citation2014).

Childhood trauma is now recognised as a global health epidemic (Department of Health & Department for Education Citation2017). In England, a 2014 survey of 3,885 individuals aged 18–69 years revealed that nearly half of the respondents (47%) had experienced at least one type of adversity prior to the age of 18, while 9% had experienced multiple (four or more) ACEs (Bellis et al. Citation2014). A report from Australia also revealed that approximately five million adults had experienced childhood trauma (Kezelman et al. Citation2015), with 25% of Australian children impacted by child abuse alone (Segal Citation2015). Moreover, the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (Citation2017) reported that two-thirds of children in the United States had experienced at least one traumatic event, such as abuse, sudden or violent loss of a loved one, terrorism or natural disaster. ACEs, and as a result, trauma, are therefore increasingly prevalent.

The impact of trauma

Regardless of the type of exposure, traumatic experiences can have ongoing adverse impacts on an individual's overall functioning (SAMHSA Citation2014), and have been linked to detrimental health impacts associated with an increase in ‘risky’ behaviours such as substance misuse, eating disorders, high-risk sexual behaviours, as well as longer-term health, relationship and employment difficulties over the life course (DuPaul et al. Citation2014). It is thought that if an individual experiences trauma, the effects can be both short- and long-term and may occur immediately following exposure to adversity or have a delayed onset (SAMHSA Citation2014). The international literature evidences consistent impacts of trauma on three key aspects of development: (1) neurological, (2) physiological and (3) psychological (Dye Citation2018).

From a neurological perspective, Nemeroff (Citation2004) has argued that exposure to trauma in early childhood, such as abuse or neglect, impacts on the brain and hormonal systems that regulate stress. Such changes can affect information processing and memory as well as an individual's ability to regulate behaviour in response to subsequent stresses (Nemeroff Citation2004). Moreover, normal brain development is disrupted when an individual experiences trauma to the point that there becomes a clear distinction between biological age and developmental age (Perry Citation2006). It is thought that brain development is affected in several key areas including the brainstem (regulating stress and metabolism), the midbrain (responsible for sensory motor control, sleep and appetite), the limbic systems (regulate emotions, attachment, affiliation, mood, and pleasure) and the cortex (associated with cognition, language, and reasoning) (Dye Citation2018).

With regards to physiological development, those who have experienced childhood trauma, and specifically abuse, are more likely to be susceptible to chronic diseases, be obese, have diabetes, suffer from high blood pressure and have problems sleeping (Greenfield and Marks Citation2009; Dye Citation2018). While from a psychological perspective, Dye (Citation2018) suggested that experiencing trauma may lead to depression, anxiety, anger and aggression, abandonment issues, difficulty trusting others and hence, unstable relationships, as well a variety of disorders (including attention deficit and hyperactive disorder (ADHD), personality disorders and eating disorders). It is believed that early childhood trauma is more detrimental than trauma experienced in adulthood due to disruptions to these neurological, physiological and psychological developmental processes. As such, adults who experienced trauma as children have higher risks of physical and psychological problems (Edwards et al. Citation2003).

Importantly, all these neurological, physiological, and psychological disruptions ultimately impact on a young person's education and school-related outcomes. For instance, a systematic review by Perfect et al. (Citation2016) identified that those exposed to ACEs, and who had subsequently experienced trauma, had poorer outcomes with regards to cognitive functioning, including lower IQ scores, impaired memory and reduced verbal abilities, in comparison with those who had not experienced trauma. In addition, those who had experienced childhood trauma were likely to demonstrate poor discipline in school and were more likely to have low attendance and drop out altogether (Perfect et al. Citation2016). Therefore, for some children, experiencing trauma may lead to challenges associated with academic performance, school behaviour and forming relationships with peers (Sciaraffa, Zeanah, and Zeanah Citation2018). Understanding the impact of trauma and the responses it might evoke is beneficial for those working with/for children and young people so as to help them comprehend the underlying reasons why some children and young people have difficulties with learning, building relationships and managing behaviour. Indeed, having a greater understanding of how to meet the needs of those who have faced ACEs might better support practitioners to move such young people towards a place of learning (Ellison, Walton-Fisette, and Eckert Citation2019).

Who is likely to experience trauma?

Anyone, at any age, from any neighbourhood or background can be impacted by trauma. Research suggests, however, that a number of factors (such as nurturing family relationships) can protect children from the psychological distress associated with traumatic experiences. Having nurturing parents, stable family relationships, adequate housing, basic needs satisfied and caring adults outside of the home who act as mentors serve as preventive factors (Turner et al. Citation2012). However, such preventative factors are not necessarily present for all young people. One such group includes those who are ‘care-experienced’ – young people who have, at some point in their lives, been removed from their family and placed in the care of state, with another family member, in foster care, in a children's home or in an adoptive placement. While a number of terms exist internationally for this group of young people (e.g., in England, terms such as ‘looked-after children’ or ‘children in care’ are employed, while in Australia, ‘children in out-of-home care’ is used and in the United States the term ‘foster youth’ is prevalent), within our own work we choose to adopt the term care-experienced to foreground the experience of being in care and the influence it has on young people's present and future lives (Quarmby, Sandford, and Elliot Citation2018).

Arguably, regardless of terminology and/or context, the range of ACEs are disproportionately associated with care-experienced young people, since they are more likely to be exposed to family breakdown, deprivation and family mental illness (Simkiss Citation2018). Moreover, in England, the Department for Education (Citation2019) identify that 63% of children and young people enter care because of abuse and/or neglect – specific markers of adversity that may lead to trauma (Felitti et al. Citation1998). Children who enter care because of abuse and/or neglect are likely to have ‘experienced the “toxic trio” of parental domestic violence, substance misuse and mental illness’ which would inevitably lead to higher ACEs scores (Simkiss Citation2018, 26). In addition, care-experienced young people are one of the groups who are most vulnerable to being bullied (Gallagher and Green Citation2012), and simply being placed in foster care has itself been identified by Smith (Citation2018) as an ACE. A review of literature by Denton et al. (Citation2016) noted that care-experienced young people may be exposed to a range of prolonged traumatic events in their early development (including physical and sexual abuse), and the impact of prolonged exposure to multiple ACEs is associated with poorer outcomes in adulthood in comparison to exposure to just one traumatic event (Simkiss Citation2018).

What does our research tell us?

Our own experiences of working with care-experienced youth stem from the ‘Right to be Active’ (R2BA) project in the UK (Sandford et al. Citation2019; Quarmby et al. Citation2020) and the ‘HEALingFootnote1 Matters’ project in Australia (Cox et al. Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Pizzirani et al. Citation2020). Within the R2BA study, our focus on exploring the sport/physical activity experiences of care-experienced youth in England highlighted the complex social landscapes that these young people navigate on a day-to-day basis and noted the significance of people, places and activities in shaping these engagements (Sandford et al. Citation2019). We found, in particular, that for young people to have ‘good’ experiences of sport/physical activity there needed to be an intersection of these three key factors (people, places and activities) and that this relied, to a significant extent, on shared understandings and collaborative engagements. However, the complex structure of the care context – with its rules, procedures, and regulations – resulted, for many, in a shifting landscape where opportunity and access to activities were often problematic. Aligned with this was an evident lack of clarity regarding just whose responsibility it was to facilitate sport/physical activity opportunities for care-experienced young people (Sandford et al. Citation2019). For example, within the study it was evident that schools were a key space for care-experienced youth and, with regard to PE in particular, there were considerable expectations (from those outside of the school context) regarding the role of education in providing opportunities to engage in sport/physical activity. However, conversations with educators revealed that despite a desire to facilitate engagement in such activities for care-experienced youth, they often lacked specific knowledge with regard to the realities of their lives and had received little, if any, training regarding the potential role of trauma in shaping experiences.

Similarly, in our formative research for HEALing Matters, we examined the presence and impact of barriers to engaging in physical activity (including sports and/or recreation activities) for young people living in residential children's homes (Green et al., CitationUnder Review). Discussions with carers and young people identified a range of barriers, including: inadequate staffing (to transport young people to and from activities and support them during the activity), a lack of financial resources to fund physical activity, behavioural and safety concerns about young people (for both the individual and their peers), and individual barriers relating to substance misuse, self-esteem and ability. Interestingly, a common theme was identified around organised sports clubs lacking the capacity or resources to accept young people from residential children's homes into their community sports programmes, and young people feeling a sense of stigma when engaging within these settings. This finding led to a recommendation to work with the relevant state bodies (who have oversight of care arrangements) to build the capacity of sports coaches and volunteers to understand and engage young people from a trauma-aware perspective and to ensure they are able to respond to the increasingly complex needs of young people in care. These findings point to the importance of ensuring the broader community (including schools) are recognised as a key facilitator of physical activity.

Taken together, and with consideration of findings from related work we have collectively been involved with (e.g. Quarmby, Sandford, and Elliot Citation2018), we began to question to what extent are schools – and more specifically, teachers – equipped to work with care-experienced young people; how might our work help to inform teachers in this respect; and what might trauma-aware pedagogies ‘look like’ within PE? Certainly, it has been argued that more work needs to be done to help educators understand what underpins the disruptive behaviours that care-experienced young people often exhibit (APPG Citation2012). In their study, O’Donnell, Sandford, and Parker (Citation2019) outlined how PE teachers noted a lack of shared knowledge about care-experienced young people's behaviours within schools and identified a need for further, tailored training that would help them to better understand care-experienced youths’ broader contexts and the experiences that underpin problematic behaviours. Further, in England, trauma and post-traumatic stress have been identified as key areas where schools need guidance to promote mental health and wellbeing for children (Department of Health & Department for Education Citation2017). This is particularly important in relation to school-based PE, which is increasingly being seen to have an important role to play in relation to students’ health and wellbeing.

Why do physical educators need to be aware of trauma?

PE occupies a somewhat ‘special’ place within the school curriculum, for a number of reasons, but particularly with regard to the subject matter it covers, the environments in which learning takes place and the interactions that occur within these environments. On this, Ciotto and Gagnon (Citation2018, 28) note how ‘the activities that take place in [PE] may elicit different emotions and feelings than those in the academic classroom’. There are various reasons for this, but two that are particularly pertinent to our discussion are the public nature of participation and the centrality of the body within PE. We know, for example, that changing rooms have been identified as ‘highly charged’ spaces (O’Donovan, Sandford, and Kirk Citation2015) and that the often challenging culture may render them particularly problematic environments for care-experienced young people (Quarmby, Sandford, and Elliot Citation2018). Notably, the public nature of this space, in which the body is revealed to the ‘gaze’ of others, is perceived to cause tension for many, as they struggle to manage their presentation of self in relation to broader norms and ideals (O’Donovan, Sandford, and Kirk Citation2015). The perception of the ‘gaze’ of others may, however, be amplified for those who are care-experienced, who may have visible remnants of the abuse they have been subjected to. While those delivering PE may be aware that some students in their class might struggle with issues associated with body image and putting their physical self ‘on display’, the depth of vulnerability felt by students who have been exposed to trauma is unlikely to be fully be recognised. The interactions that take place in PE may also serve to further exacerbate the anxieties of care-experienced young people within this context – particularly those involving physical contact. Caldeborg, Maivorsdotter, and Öhman (Citation2019) note how intergenerational touch – physical contact between students and teachers – whilst sometimes necessary in PE, can be far from straightforward. They suggest that, whilst both students and teachers recognise the need and value of physical contact (e.g., to support whilst performing a balance in gymnastics, or to reassure when upset after having lost a race), it is context-relevant and there can be instances where this is unwelcome (Caldeborg, Maivorsdotter, and Öhman Citation2019). PE teachers can often be unaware of care-experienced young people's ‘cared-for’ status and the trauma they may have experienced in becoming so (O’Donnell, Sandford, and Parker Citation2019). As such, those who might have particular concerns with regard to physical contact – likely on account of having experienced physical abuse – may unknowingly be subject to further (unintentional) distress by a teacher (innocently) giving them a reassuring pat on the back.

The experience of childhood trauma can thus have specific implications for children and young people's engagements within PE, particularly with regard to the physical elements of practice. However, it can also present a number of obstacles for educational practice more broadly, negatively impacting an individual's learning, behaviour and relationships (Cole et al. Citation2005). Some of these challenges may stem from difficulties processing information, being able to distinguish between threatening and non-threatening situations, forming trusting relationships with peers and/or adults, and being able to regulate their emotions (Cole et al. Citation2005). Unfortunately, this can result in traumatised children adopting behavioural coping mechanisms (e.g., aggressiveness, defiance, social withdrawal, etc.) that can be difficult for teachers, in general, to manage. Within a PE context specifically, the symptoms of trauma may manifest in small fouls that escalate into physical conflict, where students refuse to be part of a team or display an inability to form connections with teammates. Moreover, students who struggle to adhere to the rules and demonstrate an inability to handle pressure situations during competition may also exhibit symptoms of trauma (Bergholz, Stafford, and D’Andrea Citation2016). However, Ellison, Walton-Fisette, and Eckert (Citation2019) also remind us about the individual nature of traumatic experiences, noting that a child's response to traumatic events will vary depending on personal characteristics (e.g., age, maturation, intelligence), their social environment (e.g., family and school support) and the nature of the experience itself (e.g., relationship to perpetrators). As such, it is possible for individuals with similar experiences – in terms of the nature of trauma – to have very different responses to the events.

Despite this, without the benefit of a ‘trauma-aware lens’, which allows PE teachers to better understand the reasons underlying these challenging presentations, student behaviours can be misinterpreted as intentional and within the student's control, rather than as a result of pain-based or survival responses triggered by the environment – triggers that may be internal and invisible. Misinterpretation of the intent of the behaviour and what the student is communicating – for example, seeing behaviour as ‘off-task’ or wilful disobedience – can result in disciplinary actions more likely to exacerbate the behaviour than to ameliorate it, and will likely result in a rupture of the teacher-student relationship. However, if educators are able to view challenging behaviours through a trauma-aware lens, they are less likely to regard trauma-related behaviours as intentional or the actions of an ‘unmotivated’ or ‘disobedient’ child, thus reducing punitive responses that can exacerbate the problem or be re-traumatising for the child (Cole et al. Citation2005).

A responsive approach to supporting students who may have been impacted by trauma requires understanding that prolonged activation of the survival areas of the brain, including those which regulate stress, can result in a heightened sensitivity to situations and being in a state of ‘high alert’ long before a PE lesson begins. A trauma-aware lens allows teachers to better understand and even predict triggering situations for students, and to work with them to help prevent triggering and re-traumatisation. In this way, students’ self-awareness is enhanced, and self-regulation skills are developed over time, whilst building and maintaining safe environments and caring teacher-student relationships. It is, however, important to note that it is not uncommon for teachers to experience uncertainty when working with children and young people affected by trauma, and to have limited training and knowledge to draw on in their practice (Alisic et al. Citation2012). That said, trauma-related confidence has been shown to relate to greater teaching experience, exposure to trauma-focused training, and involvement with traumatised children (Alisic et al. Citation2012).

What is trauma-aware pedagogy?

Internationally, there is increasing recognition of the importance of evidence-based, trauma-aware pedagogical approaches to help address the complex needs of trauma-affected children and young people (Brunzell, Stokes, and Waters Citation2016). Given their acknowledged status as a central field in young people's experiences – one in which there are various support systems and structures – schools are undoubtedly at the forefront of this and provide a unique opportunity to intervene. Ensuring that educators understand and draw from trauma-aware pedagogies can help teachers to cater for the behavioural and learning needs of trauma-affected students in a meaningful way, creating an environment that promotes inclusion, healing and personal growth (Brunzell, Stokes, and Waters Citation2016; Avery et al. Citation2020). With the ever-present pressures on teachers to incorporate a seemingly endless stream of additional ‘best practices’ and curriculum adaptations alongside already complex and demanding roles, hesitancy to consider further pedagogical change is understandable. However, trauma-aware pedagogies may share common ground with existing pedagogical strategies already linked to effective and inclusive teaching such as problem-solving and reflective practice.

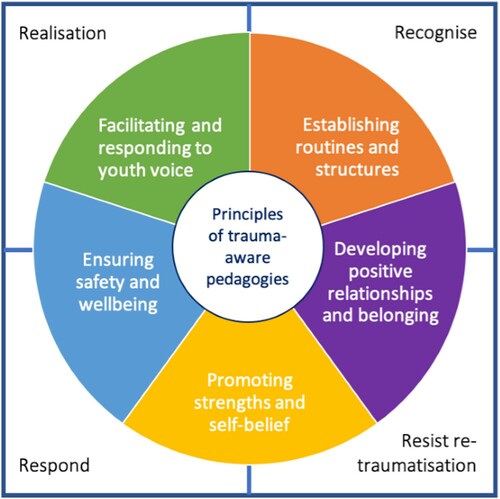

Before conceptualising what trauma-aware pedagogies might look like, SAMHSA (Citation2014) describe four key assumptions which underpin a trauma-aware approach, referred to as the four ‘R's’. These overarching assumptions should arguably apply across the whole school. The first indicates that people need to have a basic realisation about trauma and the adverse effects it can have on an individual. This means viewing people's behaviours in the context of their experiences and realising that behaviours often stem from the traumatised individual developing coping strategies to survive adversity and/or overwhelming situations. The second assumption is that people are able to recognise the signs of trauma, while the third assumes that the system (i.e., the school, staff, curriculum PE) responds in a way that embraces our understanding of trauma (i.e., staff are trained in evidence-based trauma practices and schools provide a physically and psychologically safe environment). The final assumption is that practices are put in place to resist re-traumatisation (i.e., practices are considered so they do not interfere with an individual's healing or recovery). Chafouleas et al. (Citation2019) argue that schools broadly have an opportunity to create safe and supportive environments by teachers applying these trauma-aware assumptions in their day-to-day practice.

Hence, trauma-aware pedagogies are foremost relational, acknowledging that trauma that occurs in a social context, is also healed in a social context (Bloom Citation2019); it is respectful of individuals, their strengths, personal values, identity and uniqueness, while fostering connections within the learning environment. Such social connections are facilitated by the everyday interactions PE teachers are afforded with students in the classroom, the sports hall or on the sports-field (Bloom Citation2013) and can, if transferred more broadly, contribute to developing a whole-school culture where every student feels safe and supported to succeed. Importantly, such an approach also benefits students who have not been affected by trauma, given the advantages for all students of safe learning environments that foster connections to schools or wider sporting communities (Thomas, Crosby, and Vanderharr Citation2019).

Trauma-aware pedagogies are inherently a paradigm shift in education, moving from teaching to the needs of the majority of students, to teaching to the needs of all students in the class. There is a fundamental relational context to such a paradigm that draws on mutual respect between PE teacher and student. Development of trauma-aware pedagogies necessitate an understanding of the impact of trauma on the whole child, their learning, social development, relationships and life-course trajectory. This can be a complex undertaking for those seeking to enact trauma-aware practice and as such, the development of principles might help support them in making this transition.

Developing principles for trauma-aware pedagogies in PE

PE presents a pertinent context for trauma-aware pedagogies as it affords opportunities for social interaction, personal development, life-skill development and collaborative action that are somewhat unique within the curriculum. In order to develop principles for trauma-aware pedagogies we began by consulting those identified by Fallot and Harris (Citation2009). For instance, Fallot and Harris (Citation2009) suggest that offering choice is a key principle since it allows for a degree of autonomy, which has often been compromised for those who have experience trauma. However, in the context of PE, offering choice may also be problematic; it can disrupt routine, increase feelings of uncertainty and impact negatively on skill learning. Hence, how teachers teach, and the learning environment itself, may be more important than simply offering choice. Given that Fallot and Harris’ (Citation2009) principles were developed for broader educational contexts, we drew on our collective experiences of working with care-experienced youth (who are likely to have experienced trauma) and practitioners in PE, physical activity and sport-related contexts (through R2BA and HEALing Matters) to suggest principles for trauma-aware pedagogies that are specific to PE. As such, we propose that the following five principles might be helpful when seeking to enact trauma-aware practice: (1) ensuring safety and wellbeing, (2) establishing routines and structures, (3) developing and sustaining positive relationships that foster a sense of belonging, (4) facilitating and responding to youth voice and, (5) promoting strengths and self-belief (see ). Importantly, these principles – each discussed below – can be seen to align with existing pedagogies already found in PE.

Ensuring safety and wellbeing

Young people who have experienced trauma often perceive the world as ‘unsafe’, which can manifest in hypersensitivity to anything that may threaten their safety. In relation to our own work, we have identified how care-experienced young people may experience feelings of stigma when engaging in physical activity (Quarmby et al. Citation2020; Green et al., CitationUnder Review), which can make them feel unsafe. Moreover, we have noted how the broad field of PE (including the context of the changing room) needs to be taken into consideration when ensuring student safety and wellbeing, since these spaces are frequently reported as problematic for those who have experienced trauma (Quarmby, Sandford, and Elliot Citation2018).

Providing a protective PE space requires an understanding of what is safe from the student's point of view, not simply procedural considerations such as facility risk assessments and equipment checks. Moreover, the concept of ‘safety’ should encapsulate both physical and emotional safety, enabling students to identify and name their feelings without judgement. We consider this to be an important part of the process of developing safe environments that lead to positive change. We agree with Tinning (Citation2020) who suggests that while PE cannot be responsible for healing young people with histories of trauma, it should, without doubt, cause no further harm. As such, PE teachers must demonstrate sensitivity, understanding, compassion and a non-judgemental attitude, and should seek to discuss factors that could potentially trigger or cause a student further harm (Ellison, Walton-Fisette, and Eckert Citation2019). Brief ‘check-ins’ to provide encouragement and support may be particularly useful in this regard and provide PE teachers with the opportunity to not only ensure safety, but also promote trust.

Establishing routines and structures

Routines and structures play a key role in ensuring security. For care-experienced young people, structure is an important way for them to begin to gain a sense of control and to feel like life can be regulated. Through establishing routines, PE teachers can help to provide a level of consistency for young people, re-establishing the belief that the world can be a safe and secure place. Our own work has frequently noted how care-experienced young people's lives are often complicated and fluid, with multiple placement movesFootnote2 resulting in changes in schools, social workers and peer groups (Quarmby, Sandford, and Elliot Citation2018; Sandford et al. Citation2019; Green et al., CitationUnder Review). We have seen how regular engagement with sports clubs, teams, and both formal and informal physical activities is repeatedly identified as being important for their sense of belonging. Thus, facilitating sustained engagement and establishing consistent routines/structures is vital.

In PE, preparing students for what will happen next, forewarning of any changes in plans and signalling how/when an activity will end, could reduce the likelihood of stress responses. Transition periods, including the beginning and end of PE lessons, can be challenging for those with a heightened stress response, yet knowing what is expected in advance could support students’ self-regulation. Similarly, providing visual details of the session – on a whiteboard, for example – might provide students with information they may miss when given as verbal instructions. Finally, enhanced communication between PE teachers and carers could also increase the sense of consistency across the ‘home’ and school settings, further enhancing a young person's sense of safety and wellbeing.

Developing and sustaining positive relationships that foster a sense of belonging

Young people who have experienced trauma have difficulty trusting adults and forming relationships with peers, though within our own work, we have identified how influential positive relationships can be in shaping sport/physical activity experiences for care-experienced youth. Care-experienced young people noted, specifically, how opportunities to engage with PE teachers in ‘different’ ways (compared to teachers in other subject areas) meant that they were sometimes an important contact, yet this was dependant on teachers knowing about and understanding the young person's background (Sandford et al. Citation2019). The importance of positive relationships was also identified in the pilot evaluation of HEALing Matters (Cox et al. Citation2017a). Positive relationships between both the carer and young person or programme coordinator and young person, increased motivation and engagement in physical or recreation activities – weaker relationships reduced the likelihood of engagement and participation.

In PE, developing positive relationships may set the foundations for more inclusive, socially just and equitable outcomes for all students (Mordal Moen et al. Citation2019). McCuaig, Öhman, and Wright (Citation2013) have claimed that in the search for more socially just PE settings, teachers should care more for those students who may be identified as problematic deviants. With such students, taking an interest and getting to know them, along with the ‘little things’ – such as greeting them, using their names, sitting on their level when speaking and being positive and encouraging – demonstrates an overall ethos of care, which has been noted to be influential in helping to develop and sustain positive relationships (Mordal Moen et al. Citation2019). In addition, by asking how they might be able to better support students or expressing enjoyment at having them as part of their lesson, PE teachers might also help to foster a sense of belonging for young people who have experienced trauma. By communicating relational concepts such as trust, empathy, kindness, caring and support, PE teachers can help to develop positive relationships and become trusted adults that the students can relate to.

Facilitating and responding to youth voice

By facilitating and responding to youth voice, teachers can begin to recognise young people as diverse and complex learners, although importantly this might require teachers to recognise and reflect on a student's circumstances before consulting with them about their needs. Facilitating and responding to youth voice may ultimately help build rapport between PE teacher and student and, as Ellison, Walton-Fisette, and Eckert (Citation2019) note, knowing that one adult is there for you can improve a student's ability to process and respond to stress – which is vital for those who have experienced trauma. In relation to our own work, care-experienced young people appreciated having opportunities for voice but felt these were often tokenistic. For instance, they reported that many formal meetings with ‘official adults’ involved being asked questions about their daily lives yet felt little changed as a result of these (Sandford et al. Citation2019). Within PE, therefore, it is important to recognise the boundaries to voice and consider the best/most appropriate way to help facilitate this.

Facilitating and responding to youth voice is common within many student-centred approaches in PE and can result in enhanced participation, enjoyment and meaningfulness (Beni, Fletcher, and Ni Chróinín Citation2017). Consistently facilitating and responding to student voice may therefore come in the form of after-lesson debriefs, similar to those utilised in activist approaches (e.g. Oliver and Oesterreich Citation2013) whereby PE teachers listen to students’ views about the lesson in order to respond in subsequent sessions. Building collaboration and ownership of the learning outcomes, and engaging students in how to meet the learning task using alternative activities, may also help to facilitate youth voice. Enabling participation in decision-making may also enhance fairness and trust further enhancing feelings of safety.

Promoting strengths and self-belief

Finally, there is a need for physical educators to recognise and value the strengths and skills that young people bring to PE – and to help students to recognise and value these. Students who have been exposed to trauma are more likely to view themselves negatively and so promoting the strengths of students in PE can help to build self-esteem and self-efficacy. We have previously reported that young people who are care-experienced enjoy the sense of achievement gained from participation in sport/physical activity. This includes feelings associated with learning new skills, winning and being awarded medals (Quarmby et al. Citation2020). For many, developing new skills also contributed to supporting the continuation of an educational journey. As such, promoting strengths and enhancing students’ self-belief in PE is not only important for helping young people to heal from trauma, but may also impact on their engagement with education more broadly.

In PE specifically, a focus on skill development can allow children and young people to develop competencies in a variety of different areas and can serve as a platform for identifying their strengths, which subsequently builds self-efficacy and self-esteem (Bergholz, Stafford, and D’Andrea Citation2016). Promoting strengths signals a shift from deficit approaches – normally associated with care-experienced youth who may have experienced trauma – to strengths-based approaches. In so doing, PE teachers could focus on what the student has achieved – even the simple fact that they have ‘turned-up’. Acknowledging effort and perseverance, and demonstrating belief in their potential to succeed, may signal a shift that success is about extending the students’ own abilities rather than being compared to their peers. Finally, PE teachers could also establish a routine for providing strengths-based feedback on, for example, how they interacted with their peers and/or school staff.

Summary and conclusion

Trauma has a significant impact on young people, particularly those from more marginalised or vulnerable groups (such as care-experienced young people). Education broadly, and PE specifically, have an important role to play in supporting those who have experienced trauma, with teachers needing to be prepared to deal with student worries or insecurities and offer support, even if trauma-affected students are not easily identifiable (Ellison, Walton-Fisette, and Eckert Citation2019). We have suggested five inter-related principles for trauma-aware pedagogies as a starting point for conversations in this area. We do not mandate a particular order to these principles, although we recognise that considering safety and wellbeing first may serve to lay the foundations on which some of the other principles may be built. It also allows practitioners to work towards facilitating and responding to youth voice, recognising that this is hard to do if the conditions are not right for it and may help facilitate a sense of belonging. While we have developed these principles specifically for PE, given our work in this field, we also note the need to consider them in relation to assumptions which underpin trauma-aware approaches more broadly – notably the four ‘R's’ (see ). Hence, we believe these principles have the potential to be extended across the whole school context.

As noted earlier, the principles we outline can be seen to align with existing pedagogies found in PE. For instance, they share common ground with existing pedagogical strategies already linked to effective and inclusive teaching such as problem-solving and reflective practice. Likewise, there are a number of elements within the TPSR model that help to position it as a trauma-aware pedagogy, such as establishing a trusting relationship, creating ‘safe spaces’, and establishing predictable routines. Indeed, Ellison, Walton-Fisette, and Eckert (Citation2019, 35) argue that the structure and format of TPSR facilitates the creation of a ‘trauma-sensitive learning environment’. We would argue that other existing pedagogical strategies, too, have features that are reflective of trauma-aware pedagogies. For instance, the principles we identify all point to the need for creating safe environments, shaped by consistency, positive connections and opportunities for interaction and engagement. This aligns well with notions of restorative practice (Hemphill et al. Citation2018) and the concept of pedagogies of affect (Kirk Citation2020). Hence, it is not our intention to suggest that there is one way to enact a trauma-aware pedagogy rather, that an understanding of trauma may enable physical educators to ask when, and for whom, it might be best to draw on particular models in the teaching of PE, through which these principles can be applied.

Trauma-aware pedagogies fit with recent agendas in education that are concerned with creating a more socially just and egalitarian society. For instance, acknowledging that students who have experienced trauma each differ in their support needs and taking active measures to provide for those supports, promotes social justice and acts as a means of enabling student engagement and inclusion. That said, we recognise that a shift in paradigm to trauma-aware pedagogies may be challenging for teachers. Adopting trauma-aware pedagogies may require teachers to integrate new beliefs and practices into what they currently know/do. Bringing about dispositional change in teachers is certainly challenging (Tinning Citation2020) and we are not suggesting that trauma-aware pedagogies can necessarily be embraced by teachers effortlessly. For current practitioners, a starting point may be to reflect upon what they already do, who their learners are and how these principles might relate to them. For prospective PE teachers, helping them to acquire the necessary skills and knowledge to enact trauma-aware pedagogies begins with PE teacher education programmes, that would need to engage student teachers with different content knowledge (e.g. about the impact/implications of trauma) and different pedagogical content knowledge (e.g. how to adapt activities to ensure they draw on/elucidate the strengths of young people) in order to help them become more sensitive to the needs, feelings and capacities of young people who have experienced trauma.

Finally, we suggest that these principles, framed by the key assumptions of trauma-aware approaches should be further explored with youth and teachers alike, whereby their shared experiences may help to co-produce further/more refined pedagogic practices/strategies that might help alleviate issues associated with trauma.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere thanks to Shirley Gray for acting as a critical friend and providing valuable feedback on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 HEALing stands for Healthy Eating Active Living.

2 Placement moves occur when a child/young person is moved from one setting (e.g. foster care or a residential home) to another setting as a result of breakdown in their current placement.

References

- Alisic, E., M. Bus, W. Dulack, L. Pennings, and J. Splinter. 2012. “Teachers’ Experiences Supporting Children after Traumatic Exposure.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 25 (1): 98–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20709.

- American Psychiatric Association. 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- APPG (All-Party Parliamentary Group for Looked-After Children and Care Leavers). 2012. Education Matters in Care. A Report by the Independent Cross-Party Inquiry into the Educational Attainment of Looked after Children in England. HMSO/UCU. London.

- Avery, J., H. Morris, E. Galvin, M. Misso, M. Savaglio, and H. Skouteris. 2020. “Systematic Review of School-Wide Trauma-Informed Approaches.” Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-020-00321-1.

- Bellis, M., K. Hughes, N. Leckenby, C. Perkins, and H. Lowey. 2014. “National Household Survey of Adverse Childhood Experiences and their Relationship with Resilience to Health-Harming Behaviours in England.” BMC Medicine 12: 72.

- Beni, S., T. Fletcher, and D. Ni Chróinín. 2017. “Meaningful Experiences in Physical Education and Youth Sport: A Review of the Literature.” Quest 69 (3): 291–312. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2016.1224192.

- Bergholz, L., E. Stafford, and W. D’Andrea. 2016. “Creating Trauma-Informed Sports Programming for Traumatized Youth: Core Principles for an Adjunctive Therapy Approach.” Journal of Infant, Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy 15 (3): 244–253.

- Bloom, S. 2013. Creating Sanctuary: Toward the Evolution of Sane Societies. New York: Routledge.

- Bloom, S. L. 2019. “Trauma Theory.” In Humanising Mental Health Care in Australia: A Guide to Trauma-Informed Approaches, edited by B. Richard, J. Haliburn, and S. King, 3–30. New York: Routledge.

- Brunzell, T., H. Stokes, and L. Waters. 2016. “Trauma-Informed Flexible Learning: Classrooms that Strengthen Regulatory Abilities.” International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies 7: 218–239.

- Caldeborg, A., N. Maivorsdotter, and M. Öhman. 2019. “Touching the Didactic Contract—A Student Perspective on Intergenerational Touch in PE.” Sport, Education and Society 24 (3): 256–268. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2017.1346600.

- Chafouleas, S., T. Koriakin, K. Roundfield, and S. Overstreet. 2019. “Addressing Childhood Trauma in School Settings: A Framework for Evidence-Based Practice.” School Mental Health 11: 40–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9256-5.

- Ciotto, C., and A. Gagnon. 2018. “Promoting Social and Emotional Learning in Physical Education.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance 89 (4): 27–33.

- Cole, S., J. O’Brien, M. Gadd, J. Ristuccia, D. Wallace, and M. Gregory. 2005. Helping Traumatized Children Learn: Supportive School Environments for Children Traumatized by Family Violence. Boston: Massachusetts Advocates for Children.

- Cox, R., H. Skouteris, M. Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. McCabe, B. Watson, A. D. Jones, S. Omerogullari, K. Stanton, L. Bromfield, and L. Hardy. 2017b. “A Qualitative Exploration of Coordinators’ and Carers’ Perceptions of the Healthy Eating, Active Living (HEAL) Programme in Residential Care.” Child Abuse Review 27 (2): 122–136.

- Cox, R., H. Skouteris, M. Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, B. Watson, A. D. Jones, S. Omerogullari, K. Stanton, L. Bromfield, and L. Hardy. 2017a. “The Healthy Eating, Active Living (HEAL) Study: Outcomes, Lessons Learnt & Future Recommendations.” Child Abuse Review 26 (3): 196–214.

- Denton, R., C. Frogley, S. Jackson, M. John, and D. Querstret. 2016. “The Assessment of Developmental Trauma in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review.” Child Clinical Psychology and Psychiatry 2: 1–28. doi:https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104516631607.

- Department for Education. 2019. Children Looked-after in England (Including Adoption), Year Ending 31 March 2019. London: Department for Education.

- Department of Health & Department for Education. 2017. Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Provision: A Green Paper. London: Department of Health & Department for Education.

- Downey, L. 2007. Calmer Classrooms: A Guide to Working with Traumatized Children. Melbourne: Child Safety Commissioner.

- DuPaul, G., R. Reid, A. Anastopoulos, and T. Power. 2014. “Assessing ADHD Symptomatic Behaviors and Functional Impairment in School Settings: Impact of Student and Teacher Characteristics.” School Psychology Quarterly 29 (4): 409–421.

- Dye, H. 2018. “The Impact and Long-Term Effects of Childhood Trauma.” Journal of Human Behaviour in the Social Environment 28 (3): 381–392. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2018.1435328.

- Edwards, V., G. Holden, V. Felitti, and R. Anda. 2003. “Relationship Between Multiple Forms of Childhood Maltreatment and Adult Mental Health in Community Respondents: Results from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study.” The American Journal of Psychiatry 160 (8): 1453–1460.

- Ellison, D., J. Walton-Fisette, and K. Eckert. 2019. “Utilizing the Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR) Model as a Trauma-Informed Practice (TIP) Tool in Physical Education.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 90 (9): 32–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2019.1657531.

- Fallot, R., and M. Harris. 2009. Creating Cultures of Trauma-Informed Care (CCTIC): A Self-Assessment and Planning Protocol. Washington, DC: Community Connections.

- Felitti, V., R. Anda, D. Nordenberg, D. Williamson, A. Spitz, V. Edwards, M. Koss, and J. Marks. 1998. “Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study.” American Journal of Preventative Medicine 14 (4): 245–258.

- Gallagher, B., and A. Green. 2012. “In, Out and after Care: Young Adults’ Views on their Lives, as Children, in a Therapeutic Residential Establishment.” Children and Youth Services Review 34 (2): 437–450.

- Green (nee Cox), R., L. Bruce, R. O’Donnell, T. Quarmby, D. Strickland, and H. Skouteris. Under review. “‘We’re Trying So Hard for Outcomes but at the Same Time We’re Not Doing Enough’: Barriers to Physical Activity for Australian Young People in Residential Out-of-Home Care.” Child Care in Practice.

- Greenfield, E., and N. Marks. 2009. “Violence from Parents in Childhood and Obesity in Adulthood: Using Food in Response to Stress as a Mediator of Risk.” Social Science & Medicine 68: 791–798.

- Hemphill, M., E. Janke, B. Gordon, and H. Farrar. 2018. “Restorative Youth Sports: An Applied Model for Resolving Conflicts and Building Positive Relationships.” Journal of Youth Development 13 (3): 76–96.

- Kezelman, C., N. Hossack, P. Stavropoulos, and P. Burley. 2015. The Cost of Unresolved Childhood Trauma and Abuse in Adults in Australia. Sydney: Adults Surviving Child Abuse & Pegasus Economics.

- Kirk, D. 2020. Precarity, Critical Pedagogy and Physical Education. London: Routledge.

- McCuaig, L., M. Öhman, and J. Wright. 2013. “Shepherds in the Gym: Employing a Pastoral Power Analytic on Caring Teaching in HPE.” Sport, Education and Society 18 (6): 788–806.

- Mordal Moen, K., K. Westlie, G. Gerdin, W. Smith, S. Linnér, R. Philpot, K. Schenker, and L. Larsson. 2019. “Caring Teaching and the Complexity of Building Good Relationships as Pedagogies for Social Justice in Health and Physical Education.” Sport, Education and Society. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1683535.

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network. 2017. Trauma-Informed Care: Creating Trauma-Informed Systems. https://www.nctsn.org/trauma-informed-care/creating-trauma-informedsystems.

- Nemeroff, C. 2004. “Neurobiological Consequences of Childhood Trauma.” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 65: 18–28.

- O’Donnell, C., R. Sandford, and A. Parker. 2019. “Physical Education, School Sport and Looked-after-Children: Health, Wellbeing and Educational Engagement.” Sport, Education and Society. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1628731.

- O’Donovan, T., R. Sandford, and D. Kirk. 2015. “Bourdieu in the Changing Room.” In Pierre Bourdieu and Physical Culture, edited by lisahunter, W. Smith, and E. Emerald, 57–64. London: Routledge.

- Oliver, K., and H. Oesterreich. 2013. “Student-Centered Inquiry as Curriculum as a Model for Field-Based Teacher Education.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 45 (3): 394–417. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2012.719550.

- Perfect, M., M. Turley, J. Carlson, J. Yohanna, and M. Saint Gilles. 2016. “School-Related Outcomes of Traumatic Event Exposure and Traumatic Stress Symptoms in Students: A Systematic Review of Research from 1990 to 2015.” School Mental Health 8 (1): 7–43.

- Perry, B. 2006. “Applying Principles of Neurodevelopment to Clinical Work with Maltreated and Traumatized Children: The Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics.” In Working with Traumatized Youth in Child Welfare, edited by N. B. Webb, 27–52. New York: Guilford Press.

- Pizzirani, B., R. O’Donnell, L. Bruce, R. Breman, M. Smales, J. Xie, H. Hu, H. Skouteris, and R. Green (nee Cox). 2020. “The Large-Scale Implementation and Evaluation of a Healthy Lifestyle Programme in Residential Out-of-Home Care: Study Protocol.” International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 25 (1): 396–406.

- Quarmby, T., R. Sandford, and E. Elliot. 2018. “‘I Actually Used to Like PE But Not Now’: Understanding Care-Experienced Young People (Dis)engagement with Physical Education.” Sport, Education & Society 24 (7): 714–726. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2018.1456418.

- Quarmby, T., R. Sandford, O. Hooper, and R. Duncombe. 2020. “Narratives and Marginalised Voices: Storying the Sport and Physical Activity Experiences of Care-Experienced Young People.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2020.1725099.

- Sandford, R., T. Quarmby, O. Hooper, and R. Duncombe. 2019. “Navigating Complex Social Landscapes: Examining Care Experienced Young People’s Engagements with Sport and Physical Activity.” Sport, Education and Society. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2019.1699523.

- Sciaraffa, M., P. Zeanah, and C. Zeanah. 2018. “Understanding and Promoting Resilience in the Context of Adverse Childhood Experiences.” Early Childhood Education Journal 46: 343–353.

- Segal, L. 2015. “Economic Issues in the Community Response to Child Maltreatment.” In Mandatory Reporting Laws and the Identification of Severe Child Abuse and Neglect. Child Maltreatment, edited by B. Mathews, and D. Bross, 193–216. New York: Springer.

- Simkiss, D. 2018. “The Needs of Looked after Children from an Adverse Childhood Experience Perspective.” Paediatrics and Child Health 29 (1): 25–33.

- Smith, M. 2018. “Capability and Adversity: Reframing the ‘Causes of the Causes’ for Mental Health.” Palgrave Communications 4 (13): 1–5.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2014. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Thomas, S. M., S. Crosby, and J. Vanderharr. 2019. “Trauma-Informed Practices in Schools Across Two Decades: An Interdisciplinary Review of Research.” Review of Research in Education 43 (1): 422–452. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X18821123.

- Tinning, R. 2020. “School PE and ‘Fat’ Kids: Maintaining the Rage and Keeping a Sense of Perspective.” Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education 11 (2): 101–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/25742981.2020.1773883.

- Turner, H., D. Finkelhor, R. Ormrod, S. Hamby, R. Leeb, J. Mercy, and M. Holt. 2012. “Family Context, Victimization, and Child Trauma Symptoms: Variations in Safe, Stable, and Nurturing Relationships During Early and Middle Childhood.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 82 (2): 209–219.

- World Health Organization. 1992. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Youth Sport Trust. 2020. Evidence Paper: The Impact of Covid-19 Restrictions on Children and Young People. Youth Sport Trust. https://www.youthsporttrust.org/system/files/resources/documents/Evidence%20paper%20-%20The%20impact%20of%20Covid%20restrictions%20on%20children%20and%20young%20people%20-%20Ver%202%20-%20July%202020.pdf.