Abstract

This paper introduces and recommends a particular approach to the structuring of courses of bioethics education, an approach that has the merits of being both relevant to a wider nonprofessional audience and readily applicable to the circumstances in which ordinary people are called upon to make bioethical decisions. As an explanatory preamble, the first part of this paper analyzes the process of a notable ethics committee as it addressed the topic of medical futility. This paper draws attention to the merits of the committee's structuring a response to its complex bioethical challenge in a particular interdisciplinary fashion. The next section of this paper then applies lessons from the analysis of the ethics committee process to the field of ethics education more generally, and attention is given to the practicalities of ethics course design and implementation. The educational functions of a central question, discrete disciplinary elements, and culminating interdisciplinary integration are explained. An illustrative example of one ethics course designed according to the suggestions of this paper is presented. The paper ends by indicating the merits of this approach to bioethics education, given the current cultural circumstances.

Introduction

It is widely acknowledged in contemporary medicine that there is a pressing need for greater familiarity with the ethical dimension of health care. This need exists among health and social welfare professionals and also among the population at large. In the case of a person called upon to act as a surrogate or proxy for a loved one approaching the end of life, for example, a facility with relevant ethical concepts (autonomy, justice, dignity, etc.) will better equip him or her to navigate an increasingly fraught terrain of complex decisions that matter personally, here and now. Taking its cue from the innovative approach of a unique ethics committee, this paper explores the possibilities of a nuanced model for structuring bioethics education. This model stands on its own feet as a promising means of bioethics education. Moreover, the approach is also relevant to a wider nonprofessional audience and promotes skills applicable to the actual circumstances in which ordinary people are called upon to make bioethical decisions. In this sense, the model promises to help meet the wider social need for practical facility with complex medical decision making. That is, this approach demonstrates the kind of interdisciplinary deliberation that all people, health and social welfare professionals and others, will increasingly be called upon to engage in. The potential for this educational approach's serving as a model for wider community engagement (in a sense varying according to cultural and national context) is an important social consideration in its favor.

In order to understand the nature and rationale of this model for structuring bioethics education, it is necessary to take an excursus to consider the work of a unique ethics committee. The ethics committee's approach illustrates the educational function of a focusing question and the process of analyzing a complex question into discrete disciplinary elements.

The Community Ethics Committee

The Community Ethics Committee (CEC) is a volunteer group of Boston area community members who are diverse in terms of age, religious affiliation, socioeconomic status, cultural and language groups, and educational background.Footnote1 The CEC was developed to serve both as a policy-review resource to the teaching hospitals affiliated with Harvard Medical School (HMS) and as an educational resource to the varied communities from which the members come. HMS Division of Medical Ethics felt the need for such a consultative group was long evident since individuals currently serving as community members on hospital ethics committees were not able to be broadly representative of multiple communities. Solicitation for membership on the committee is cast widely through community, business, and church groups, with a specific application process to ensure selection of a diverse and effective working group. As preparation for committee discussion and deliberation, each June new CEC members attend the Harvard Clinical Bioethics Course at the HMS Division of Medical Ethics for an introduction to bioethical concepts and deliberation.

Striving to represent the community's voice for over six years, the CEC has submitted reports to healthcare institutions (on pediatric organ donation on cardiac death, withholding nontherapeutic CPR, medical staff's use of social media, and palliative sedation), to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health (on crisis standards of care), and to the Presidential Commission on Bioethical Issues (on recommended protections for participants in research). It also circulated a White Paper to the Massachusetts voting public regarding a November 2012 Death with Dignity Petition. In January 2013, the CEC completed its report Medical Futility: Strategies for Dispute Resolution When Expectations and Limits of Treatment Collide.Footnote2

Consideration of the process by which the CEC responded to this last bioethical topic, medical futility, is instructive for a determination of those means by which learning may be fostered and demonstrated in bioethics education courses.

The clinical situations that bring cases of so-called medical futility to institutional ethics committees are troubling, time-consuming, and traumatizing. The CEC met with numerous staff members from Boston area hospitals who came to share their narratives of challenging situations in which medical interventions were continued even though they were without therapeutic effect and only served to cause pain and suffering to a vulnerable dying patient. The CEC heard of patients subjected to painful interventions at the end of their lives, families tragically unable to move on from destructive grief processes, and caregivers traumatized by the demand to provide ‘bad care’ that seemed to some to approach outright medical torture. The CEC also heard from family members who shared the enduring effects of this kind of care, causing profound pain long after the death of the loved one. In addition to monthly meetings, CEC members corresponded by e-mail and shared articles and information on medical futility. CEC members also discussed these issues with their own families, friends, and colleagues. The central question with which the CEC was forcibly confronted was: how can our society minimize the occurrence of intractable disputes between families and healthcare authorities over the care of those approaching the end of life, and for whom further curative treatments appear futile?

Bios, Logos, Pathos, and Ethos

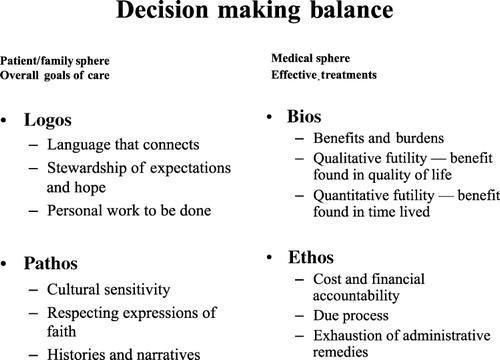

As the CEC struggled to understand the intricacies of medical futility, progress was greatly aided by an approach that emerged spontaneously from its discussions of this multifaceted question. One CEC member, an English teacher, suggested that three aspects of the topic might profitably be separated out: logos, pathos, and ethos. The Chair later suggested the addition of a fourth aspect, bios. Warming to these suggestions, other members subsequently reported that this approach gave each member a path into a topic that might otherwise have resisted comprehension altogether. The committee developed an ‘analytical grid’ () to enable it to contribute its perspectives in a meaningful way, looking separately at the biological aspects of the futility of additional treatment options (bios), the words used and the communication skills needed when discussing end-of-life care (logos), the ‘heart issues’ of culture and religion and family systems that underpin these decisions (pathos), and the societal concerns of paying for end-of-life care and instituting procedures to resolve intractable disputes when they do arise (ethos)Footnote3.

The committee divided its inquiry into the separate areas of focus, each looking at a single aspect of medical futility, and subcommittees were formed to address these separate areas. The final CEC Report mirrored this structure, ‘so that we can present our perspectives about Medical Futility in the only way we could discern would make any significant contribution to a discussion of this topic’ (p. 4). Viewed in terms of its structural contribution to the CEC's educational process in engaging with its central question, each of these areas can be understood as a discrete disciplinary focus.

Brief consideration of each area of the CEC's deliberations will help to clarify the educational lessons that can be drawn from the committee's process.

Bios—The Biology of Futility

The CEC examined whether there were any physical attributes of a patient's medical situation that made continued treatments automatically futile. Is dialysis for a terminally ill cardiac patient always futile? Is chemotherapy for a terminally ill cancer patient always futile? Such a determination may be based upon qualitative futility criteria when the harm done to the patient by the medical intervention far outweighs the benefit of an extended period of life in a significantly compromised physical state. Or such a determination may best be based upon quantitative futility criteria—the probability of more time is so insignificant as to not warrant further medical interventions. In such determinations of medical futility, the biological benefits are judged to be significantly out of balance with the burdens of the medical interventions being considered.

The CEC concluded that biological information does not provide the sole basis for making the best decision to pursue or to terminate medical interventions (p. 5). Nevertheless, biological markers such as a diagnosis of multiple irreversible organ failure, shared with patients and their families, might help them understand that a moment of medical futility may be on the horizon. However, those biological markers alone are insufficient to enable patients to make good medical decisions. The medical staff, the CEC argued, must take the time to ask questions to elicit the patient's overall goals of care in the context of the biological indicators. With a focus on what can be done to meet those goals of care and a reasoned and compassionate response to those goals that cannot be met, the physician might provide the patient and family with a basis for good decision making that can avoid a futility situation that ends in an intractable dispute between the family and the care team over the appropriate care for a patient.

Logos—Words Used at the End of Life

The CEC stated in its report that medical care teams must be able to communicate well, listening attentively and using words and manners that enable patients and their families to understand the medical treatment options available to them and the likely course of treatment. Amid recent research strongly linking early communication with less aggressive treatment during a patient's final days, the CEC was struck by the fact that poor communication is central to the development of intractable disputes. Communication among stakeholders when faced with challenging end-of-life decision making is often incomplete and biased. Loss of trust is a primary component of these disputes, and deficient communication skills are a clear precipitant to that loss of trust. Any limitations of good communication on the part of the physician can be compounded by a difficulty in comprehending on the part of the patient and family, who can seem to exist in an alternate reality, a combination of conflicted emotions, fear, grief, and loss of control over what is transpiring. The patient's and family's understandable difficulties in processing impending death can create additional barriers to productive discussion and comprehension. Accordingly, the study of communication joined the science of biology as an irreducible component in any appropriate committee response to its charge.

The CEC noted that, even when people speak the same language, cultural influences can make what is said and what is heard two different things. Learning about the internal logic of how faith informs some patients' decisions can help healthcare providers be more sensitive in presenting care recommendations. Equally, nonprofessional communities' greater understanding of end-of-life care can ultimately help patients and their surrogates/families make more informed decisions about life-sustaining treatments and end-of-life care.

Pathos—‘Heart Issues’ at the End of Life

A patient's perspective on treatment is shaped by a unique combination of cultural, ethical, and religious beliefs which often appear in bold relief when facing mortality and which are at the core of end-of-life decision making. Such is the content of the discipline of cultural studies. In addition to one's cultural and religious views of death, individuals are influenced by personal narratives of grief and loss occasioned by the dying and death of family members and loved ones. The CEC concluded that intractable disputes are more likely to arise when these personal histories are filled with distrust, fear, or a sense of despair (pp. 5–6). Other participants in a medical futility dispute—the surrogate, family, friends, physicians, nurses, other medical caregivers, chaplains, and social workers—also come with their personal histories and cultural and religious world views. Among particular religious communities, there can be an insistence on preserving life indefinitely to give the Deity time to work a miracle. Followers may believe their stewardship of life calls them to preserve life at all costs whatever the circumstance.Footnote4

Ethos—Social Structures Affecting End-of-life Care

Finally, there are social structures relevant to medical futility, including judicial and less formal procedural approaches to solutions and cost concerns raised by any limitation of access to care at end of life. The CEC recognized that the ethos of contemporary Western societies makes some futility disputes inevitable. Steeped in a culture of avoidance, such societies hold tightly to the denial of death and the rights both to life and to choice. The CEC looked at two distinctly separate kinds of social approach to disputes arising out of medical futility situations: financial considerations and dispute resolution options, whether these be judicial or other procedural paths to resolving intractable disputes (pp. 6–10).

The issue of cost presents itself forcefully when a family feels disenfranchised and distrustful of the system and its members are convinced they are not heard, respected, and cared for. When there is any sense that decisions to forgo medical interventions may be based upon ability to pay, then effective and cooperative decision making becomes impossible.

The CEC recognized there are situations in which no amount of enhanced communication, no exercise of cultural sensitivity and understanding, and no facilitated discussion can cross the divide between the family and the medical team. Availing itself of the relevant knowledge furnished here by the discipline of law, the CEC found that options exist for resolving futility disputes in such cases: the healthcare team can capitulate, providing treatment even if futile; they can unilaterally withdraw or withhold treatment judged to be nontherapeutic; the appointment of a different surrogate can be sought; the hospital may seek mediation/adjudication by an institutional ethics committee; or it may seek an adjudication by a Court or Quasi-Judicial Board. The CEC reasoned that in such cases of intractable dispute the patient's interests must be made paramount and the suffering stakeholders must be protected. It concluded that an independent review panel was the best advocate for that ‘patient in the bed’.

Application to Bioethics Education

It is the process, not the consequent recommendations, of the CEC medical futility deliberations that is of interest here. The argument of this paper is that the CEC's process suggests a promising model for the structuring of bioethical education in general, not only for consideration of medical futility. The CEC experience provides a striking instance in which authentic and profound engagement with a complex question compelled a collaborative group to analyze a challenge into discrete disciplinary elements, considering each element separately and on its own disciplinary terms, before creatively integrating these elements in such a way as to yield an effective response to the initial challenge.Footnote5 The result is, whatever else one might think of the details of the CEC's recommendations, a nuanced, sophisticated, relevant response, one that could not have been attained on the basis of one discipline alone.

There is clearly considerable overlap between the particular interpretations of bios, logos, pathos, and ethos articulated above. Sophisticated and effective interdisciplinary integration involves the creative exploration of just these areas of overlap for purposes of responding to a practical challenge. Discrete approaches or disciplinary lenses can overlap without being thereby obsolete or superfluous. Initially analyzing the distinctive features of a complex problem so as to more deliberately and consciously manage their synthesis is an essential precursor to an effective response to the challenge at issue. The CEC process in responding to the topic of medical futility suggests how, in the present cultural circumstances, promoting facility with the nuanced skills of effective and sophisticated synthesis and decision making may be more educationally valuable than an approach that places primary value on an analysis of ethical concepts themselves.Footnote6 While bioethics education is an important topic in the context of training for health and social care professionals, the CEC story serves to open up an additional, wider context, that of promoting community engagement with the challenges of complex medical decision making, challenges that appear to be becoming ever more pressing and acute.

In the next three sections below, this paper presents, by reflecting on the CEC process, a model of bioethics education. The following section then contextualizes the model, both thematically in terms of prominent existing approaches to such education and institutionally in terms of the educational settings in which the model can be applied.

The Model

Educational objectives

Appropriately structured bioethics education can foster a cluster of valuable related skills that are not always directly targeted in bioethics education efforts. Such an approach helps students become familiar with each of a number of relevant disciplines, showing understanding of disciplinary purposes, knowledge (accepted findings, concepts, and theories), and methods. In the CEC medical futility illustration, these disciplines were biology, communication studies, cultural studies, law, and economics—a daunting array of disciplines indeed. Just as CEC members reported finding that an initial disciplinary breakdown of their task offered them a path into an otherwise almost insuperable challenge, so too interdisciplinary courses in general can offer students a series of entry points into otherwise forbidding territory.Footnote7

Students need to develop critical awareness, being mindful of the purpose and means by which the several disciplines have been brought together and of the limitations of the disciplines and integration in light of the central question to be addressed.Footnote8 This kind of awareness includes a measure of appropriate self-doubt, humility, openness to changing one's mind over time, and empathy. The CEC Report gives ample testimony of the humility, empathy, and open-minded dialog that characterized the committee's most productive engagements with its task.

Finally, students will need to grow in their understanding of, and facility in responding to, the central ethical challenge, demonstrating that they have developed a new model, perspective, insight, or solution that could only have been made possible by integrating more than one disciplinary lens.Footnote9 In the CEC example, the all-important response to the challenge brought to it by the numerous Boston area hospital staff and other involved parties was its painstakingly composed report on medical futility.

It is in its promotion of these educational objectives that this model for bioethics education finds its justification. Aptitude for and confidence with effective and creative synthesis are increasingly vital qualities of responsible medical decision makers in our culture, be they health and social welfare professionals or others, and this educational model may be better suited for the promotion of such qualities than existing alternatives.

The question and the disciplines

While it is instructive to consider the CEC's process and its particular charge, it may also be helpful to take alternative sample questions as a means of considering how this model works. For example,

What is the most responsible way to manage patient information from genetic testing? and

What dangers are involved in recruiting volunteers for nontherapeutic medical research in developing countries? How might such dangers be mitigated?

The nature of the additional disciplines to be introduced depends upon the character of the essential question. Other disciplines that would naturally be included are: (1) economics and information technology as well as biology and with (2) political and social history as well as biology. From a practical pedagogical standpoint, there are various models for the provision of discrete disciplinary introductions, from team teaching of the whole course (expensive but often effective) to visiting faculty from the relevant academic department and to a deliberate and explicit disciplinary shift on the part of a single educator of appropriately rich educational background.Footnote11

Answering the question

The ultimate educational value of discrete disciplinary contributions lies with the complex integrative challenge that, taken together, they present to students in a given scenario: how is one to best take account of this wealth of information and approaches in responding to the central question? Students are now supported in integrating the distinct disciplinary elements for themselves in the course of fashioning an effective response to the central question that has motivated the inquiry from the outset. This process is challenging (witness the CEC's struggles in processing, considering, and responding to its specific charge), and students need guidance and encouragement in constructing their own responses. Collaborative work drawing on students' particular area(s) of skill is important. Illustrative examples of carefully considered responses may be used as case studies of appropriate resolutions. It is important to communicate that there is not always a single best answer; carefully thought through and effective responses may integrate the disciplinary contributions in ways that yield different answers to the central question.Footnote12

Educational context

It is helpful, by way of setting this approach to bioethics education in a broader context, to consider how it relates to existing approaches. There are different kinds of relevant context. First, one can distinguish thematic variety in how such education may be pursued. There are traditional principlist approaches, problem/case-based approaches, relational learning approaches, and other kinds of ‘interdisciplinary’ approaches.Footnote13

A second important contextual consideration is that bioethics education is delivered in varying institutional contexts: high/secondary school, undergraduate and advanced education (professional and nonprofessional), further/continuing education (professional and nonprofessional), and in the wider context of broader community outreach. Also noteworthy here is variety according to regional, national, and international context.Footnote14

As regards thematic context, the approach advocated in this paper contrasts with a traditional principlist approach to bioethics education that takes its central goals to be conveying understanding of the moral principles of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice, and fostering skill in the sensitive application of these principles to actual cases.Footnote15 This paper's approach shares with contemporary problem-based approaches dissatisfaction with the risk of philosophical abstraction inherent in principlism, given the practical orientation of many bioethics education contexts. By contrast, the approach favored here, like problem/case-based efforts, strives for relevance by focusing on a practical question that calls for an appropriate response through collaborative problem solving.Footnote16

On the other hand, it is in its explicit and deliberate introduction of discrete disciplinary scaffolding (as distinct from other kinds of teacher/facilitator support) in order to structure student engagement with the problem that this paper's approach differs from most problem/case-based approaches, as seen with the sample course presented below. Carefully structuring exploration of bioethical problems by the measured introduction of relevant disciplines equips students with relevant skills and concepts just as it enables them to manage cognitive load. CEC members report being overwhelmed by the magnitude and complexity of its medical futility charge until they initiated this process of disciplinary parsing with their challenge.

Turning to the next prominent thematic approach to bioethics education, relationship-based approaches are founded on the conviction that the most important learning in this field occurs in the context of relationships among the people involved in a given case, usually practitioners, patients, and family members.Footnote17 Improvisation, interdisciplinary role-play, video recording and playback, discussion, and reflection are characteristic methods for developing relevant relational skills. On this model, bioethics education is the sensitive fostering of this set of complex human skills.

In the field of bioethics education, the term ‘interdisciplinary’ usually marks out those collaborations that involve members of distinct but related professions, such as physicians, nurses, social workers, and chaplains. Both relational learning and problem-based initiatives can be interdisciplinary in this sense.Footnote18

The educational approach introduced in this paper shares with relational and ‘interdisciplinary’ approaches both a practical focus on a pressing challenge and an acknowledgment of the demands of the irreducible human complexity of such challenges in the bioethical domain. By contrast, conceiving of bioethical education as fundamentally consisting of exploring the application of ethical principles, as with principlism, just is not sufficiently nuanced to respond to these tasks.

However, where there is a difference in emphasis between these education efforts and that recommended in this paper is in the weight given by the latter to the deliberate and planned disciplinary ‘tooling’ or scaffolding for students, as will become more evident with the sample course outlined below.Footnote19 It is important to note, further, that ‘interdisciplinary’ in the sense used in the recommended approach does not refer solely to collaborations among professional disciplines within medical, social, and pastoral care but to academic disciplines more generally, as in the analysis of those disciplines found relevant to the CEC's medical futility deliberations (law, economics, biology, and so forth). In its conception of the educational role of such disciplines, this paper follows the recommendations of research from Project Zero at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (see footnote 5) in advocating giving time to the deliberate, explicit introduction of each such discipline on its own terms, followed by the consideration of what light the discipline sheds on the challenge at issue. Structuring education efforts in this way equips students with relevant skills and concepts and enables them to manage an otherwise daunting cognitive load, as indicated by the CEC experience.

As regards the second set of contextual considerations, having to do with the institutional context of bioethics education, it is noteworthy that bioethics education efforts along various thematic lines exist in different institutions from high school to professional education settings. One can have principlist, problem-based, relational learning and interdisciplinary approaches in any of these settings. The structural approach recommended here is suited to any educational context in which there is opportunity for the discrete and deliberate introduction of disciplinary elements together with an opportunity to foster an effective, creative synthesis in responding to a motivating question. Accordingly, the approach can, subject to contingencies of time and resources (of which more in the example section below), be appropriate for any of the delineated institutional contexts.

A final contextual point concerns the relevance of the recommended approach to a social charge of wider community outreach promoting reflection and discussion of bioethical issues such as those involving end-of-life care. The ongoing experience of the community volunteers of the CEC is instructive. Though the educational approach introduced here stands on its own feet as an effective means of bioethics education, there is an additional social benefit: the approach can demonstrate for the wider community the kind of interdisciplinary deliberation that all people, health and social welfare professionals and others, are increasingly being called upon to engage in. As the excursus into the CEC process with its medical futility charge indicates, the potential for this educational approach's serving as a model for wider community engagement, in a sense varying according to cultural and national context, is an important social consideration in its favor.

An illustrative example of an ethics course designed according to the suggestions of this paper is presented below.

An Illustrative Example

The Rivers School is a small, independent, college preparatory day school outside Boston. Rivers' nine interdisciplinary senior electives encourage students to construct effective responses to a wide range of complex questions and challenges, from the domain of Game Theory to an investigation of the Enlightenment period and to the study of infectious disease. Exploring Ethics: Language, Literature, and the Brain is one such course that takes an interdisciplinary approach to the investigation of the concepts of free will, duty, empathy, and virtue. Students are required to integrate disciplinary contributions from literature, biology, and philosophy in order to fashion their own answers to central questions:

What role do empathy and imagination have in moral thinking? and

How do contemporary developments in neuroscience reshape our ideas of responsibility and free will?

In the literature unit of the course, taught by an experienced teacher of that discipline, students read Ambrose Bierce, ‘A Horseman In the Sky’; Victor Hugo, ‘The Bishop and the Candlesticks’, excerpted from Les Miserables; Albert Camus, The Stranger; Ryunosuke Akutagawa, ‘In a Grove’; Ursula LeGuin, ‘The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas’, or an excerpt from Aldous Huxley, Brave New World; and Fyodor Dostoevsky, ‘Rebellion’, from The Brothers Karamazov. Some texts are used to introduce specific topics such as duty or virtue, but their function is also to help students consider the role that literature has in cultivating empathy and moral imagination.

In the second unit, students study the discipline of philosophy with an appropriately trained teacher of that discipline in order to consider how to apply the central disciplinary skills of conceptual clarification and precision to our notions of duty, free will, and truth. Using James and Stuart Rachels' The Elements of Moral Philosophy, students explore some leading theories about the nature of moral goodness (deontology, utilitarianism, and virtue theory) and different theories about the logical status of moral truth: realism, relativism, and subjectivism.Footnote20

In the science unit, the course sacrifices breadth of coverage for depth of exploration, a central concern being to introduce a scientific study of those features of the body and brain that are involved in conscious willing. Benefitting from co-teaching by a faculty member from the science department with a research interest in neuroscience, the course uses Sam Harris's Free Will to examine neuroscientific work that raises questions about the extent to which we are free and undetermined, and students are guided to consider the implications for notions of agency, responsibility, and humanity.Footnote21

In the planning of such courses, disciplines need to be to carefully selected according to their value in equipping students to respond to the course's essential questions, just as the questions themselves need to be selected according to their complexity, interest for students, and fit with the institution's resources and areas of teaching expertise. The overriding educational objective of each of these interdisciplinary courses is the same: to help students develop skill and confidence with the creative integration of diverse disciplinary elements in order to respond effectively to a complex challenge.

The points at which students are to synthesize the disciplines must be anticipated and indexed to opportunities for assessment. Working toward performance assessments helps students to grow in respect of their interdisciplinary facility, and student work and assessments are planned accordingly, consisting of both personal and analytical responses, journal reflections, role-play activities, presentations, and in the case of the Ethics course, a culminating seminar organized along the lines of a hospital ethics committee deliberation. The students' ethical studies are evaluated according to the degree to which they furnish the students with effective responses to the driving questions with which the course began.Footnote22 Teaching faculty members engage with the ongoing challenges of appropriately evaluating student work of this kind and of giving clear feedback that will help students improve.

While the educational settings of the CEC and Rivers School illustrations are widely different, they exhibit the same approach to structuring learning that this paper has introduced and commended. Both enterprises are motivated, focused, and sustained by complex ethical questions that are of pressing interest in that context. Both scaffold their addressing of this question by an explicit and measured consideration of the disciplinary elements that shape it. Both enterprises conceive of their greatest educational value in terms of the effectiveness of the group in responding to the motivating question(s) and developing critical awareness of the complexities of the issues and the limitations of its own response. The CEC approach emerged spontaneously, whereas the Rivers School approach is planned. The CEC is a volunteer group that meets monthly, whereas The Rivers School teaches middle and high school/secondary school students. In the most pertinent educational respects, however, these contexts are of one kind.

This model's flexibility according to educational setting is a noteworthy feature in its favor given the institutional, social, and geographical variety of ethics education contexts. Different national and regional health and social welfare priorities yield different essential questions that call for resolution. Applying the approach to a given context requires time and resources in order to fashion a structure that is appropriate given the essential question(s). Because the approach applies a number of disciplinary perspectives, the demands on faculty time and expertise are significant. As with other interdisciplinary enterprises, planning and implementing this approach makes some demands on the professionalism and goodwill of the disparate personnel called upon to collaborate for a common educational goal.

Conclusion

In her blog post of 13 November 2013, ‘Evidence Is Only One Data Point in Our Treatment Decisions’, Jessie Gruman recalls the famous face-vase example of figure–ground perception and expresses concern that:

the frantic drive toward evidence-based medicine as a strategy for quality improvement and cost reduction sets clinicians and patients up for a figure-ground conflict about our shared picture of health care … [Clinicians] hew to evidence-based guidelines as the basis for their treatment recommendations and plans … For us, however, the evidence constitutes only one data point in our decision to proceed with a treatment … Will it hurt? What are the side effects? Will I be able to drive? Work? … What is the price—financially and in terms of inconvenience? … What will be required of others to make this treatment work for me, now and over the long term? … How will I feel? … Do I have the time to take this on when my job is insecure? … Will I need to hire help? How can I summon the energy to organize even a modest change in my routine when I am so depressed and overwhelmed? … The success of our mutual enterprise … requires that the polarity of those views [between patients and their clinicians] be reduced. (Center For Advancing Health, http://www.cfah.org/blog/2013/evidence-is-only-one-data-point-in-our-treatment-decisions)

Bioethics is a discrete field of study, but such study withers in isolation from the practical questions and challenges that motivate it and the other related disciplines that give it context and meaning. Bioethics can be incorporated within a wider context of developing skills of effective and informed decision making. Bioethical learning is thus informed, motivated, and enhanced by an appreciation of its wider medical and socioeconomic context. Moreover, in the sense suggested here, our societies' timely engagement with medical decision making can ultimately be enhanced. In a culture facing (not facing?) the need to improve its competency in addressing a whole class of urgent, complex decisions, there is a corresponding need for this approach to bioethics education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The committee was created under the auspices of the Harvard Ethics Leadership Group and functions as a part of the nonprofit Community Voices in Medical Ethics, Inc., established in 2011 in order to enhance the CEC's mission to bring the issues of medical ethics into the community as well as to include the community's voice in the dialogue already occurring in healthcare institutions, government, and academia. Some of the following material on the CEC and its medical futility deliberations is based on Powers et al. (Citation2013).

2. Medical Futility: Strategies for Dispute Resolution When Expectations and Limits of Treatment Collide. http://www.medicalethicsandme.org/p/publications-of-cec.html.

3. See Powers et al. (Citation2013).

4. One of the committee's recommendations is that healthcare institutions implement training that is focused on cultural literacy and sensitivity to patient and family ethnic, religious, and cultural belief systems.

5. This conception of interdisciplinary understanding is based on the analyses in Boix Mansilla, Miller, and Gardner (Citation2000) and Boix Mansilla and Dawes Duraising (Citation2007).

6. One may well not be forced to choose between approaches. A bioethics unit of the kind described below may be profitably included within the context of a different kind of bioethics education effort.

7. The Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania is one well-recognized example of a center for interdisciplinary bioethics education.

8. See Boix Mansilla and Dawes Duraising (Citation2007, 228–229).

9. Boix Mansilla and Dawes Duraising (Citation2007, 225–228).

10. The first module of the National Institutes of Health (Citation2009) biology curriculum supplement Exploring Bioethics introduces bioethical concepts and reasoning at the high school level.

11. Among other possibilities, of special promise are those involving use of online educational and research resources and collaborative use of software such as Google Docs. A discussion of interdisciplinary teaching practices can be found in Wentworth and Davis (Citation2002) and Bystrom (Citation2002).

12. H. M. Curtler applies the techniques of critical thinking to an array of scenarios, thereby showing how one discipline—philosophy—can improve ethical decision making by, inter alia, helping one avoid logical fallacies (see Curtler Citation2004). Attempts at interdisciplinary integration can be evaluated by reference to canons of reasonableness and consistency, but it is nonetheless true that ‘objectivity’ is harder to come by here.

13. A given bioethics education effort may offer a combination of different thematic approaches, and there are certainly areas of thematic overlap between some approaches outlined here. Lehmann et al. (Citation2004) and Goldie (Citation2000) demonstrate the diversity of approaches to medical ethics education that exists at medical schools in Canada and the USA.

14. Mattick and Bligh (Citation2006) surveys UK medical schools' ethics teaching, finding the integration of ethics with other course areas to be most valued by teachers and students alike over against ‘dry’ ethical theory. Ashcroft et al. (Citation1998) is a seminal consensus statement in the UK context: ‘Teaching Medical Ethics and Law within Medical Education: A Model for the UK Core Curriculum’.

15. Beauchamp and Childress (Citation2008).

16. Barrows (Citation1996). See also Siegler (Citation2001).

17. One leading exponent of this approach in the professional education context is The Institute for Professionalism and Ethical Practice at Children's Hospital Boston. See Browning et al. (Citation2007) and also Meyer et al. (Citation2009).

18. For an example of the first, see Browning and Solomon (Citation2005) and Solomon et al. (Citation2010). For an example of the second, see Ellman and Fortin (Citation2012).

19. As with the problem-based comparison above, it may be that relationship-based approaches can incorporate these elements to some degree. See footnote 6—one is not always forced to choose between approaches.

20. Rachels and Rachels (Citation2011).

21. Harris (Citation2012).

22. Boix Mansilla and Dawes Duraising (Citation2007).

References

- Ashcroft, R., D. Baron, S. Benstar, S. Bewley, K. Boyd, J. Caddick, A. Campbell, A. Cattan, G. Claden, and A. Day. 1998. “Teaching Medical Ethics and Law within Medical Education: A Model for the UK Core Curriculum.” Journal of Medical Ethics 24: 188–192.

- Barrows, H. S. 1996. “Problem-based Learning in Medicine and Beyond: A Brief Overview.” New Directions for Teaching and Learning 68: 3–12.

- Beauchamp, T. L., and J. F. Childress. 2008. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 6th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Boix Mansilla, V., and E. Dawes Duraising. 2007. “Targeted Assessment of Students' Interdisciplinary Work: An Empirically Grounded Framework Proposed.” Journal of Higher Education 78 (2): 215–237.

- Boix Mansilla, V., W. C. Miller, and H. Gardner. 2000. “On Disciplinary Lenses and Interdisciplinary Work.” In Interdisciplinary Curriculum: Challenges to Implementation, edited by P. Grossman and S. Wineburg, 17–38. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Browning, D. M., E. C. Meyer, R. D. Truog, and M. Z. Solomon. 2007. “Difficult Conversations in Health Care: Cultivating Relational Learning to Address the Hidden Curriculum.” Academic Medicine 82 (9): 905–913.

- Browning, D. M., and M. Z. Solomon. 2005. “The Initiative for Pediatric Palliative Care: An Interdisciplinary Educational Approach for Healthcare Professionals.” Journal of Pediatric Nursing 20 (5): 326–334.

- Bystrom, V. 2002. “Teaching on the Edge.” In Innovations in Interdisciplinary Teaching, edited by C. Haynes, 67–93. Westport, CT: Oryx Press.

- Curtler, H. M. 2004. Ethical Argument: Critical Thinking in Ethics. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Ellman, M. S., and F. H. Fortin. 2012. “Teaching Medical Students How to Communicate with Patients Having Serious Illness: Comparison of Two Approaches to Experiential, Skill-based, and Self-reflective Learning.” Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 85 (2): 261–270.

- Goldie, J. 2000. “Review of Ethics Curricula in Undergraduate Medical Education.” Medical Education 34 (2): 108–119.

- Harris, S. 2012. Free Will. New York: Free Press.

- Lehmann, L. S., W. S. Kasoff, P. Koch, and D. D. Federman. 2004. “A Survey of Medical Ethics Education at U.S. and Canadian Medical Schools.” Academic Medicine 79 (7): 682–689.

- Mattick, K., and J. Bligh. 2006. “Teaching and Assessing Medical Ethics: Where Are We Now?” Journal of Medical Ethics 32 (3): 181–185.

- Meyer, E. C., D. E. Sellers, D. M. Browning, K. McGuffie, M. Z. Solomon, and R. D. Truog. 2009. “Difficult Conversations: Improving Communication Skills and Relational Abilities in Health Care.” Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 10 (3): 352–359.

- National Institutes of Health. 2009. Exploring Bioethics. Newton, MA: Education Development Center.

- Powers, C., M. Jurchak, P. McLean, and P. Smith. 2013. “An Aide to Addressing Medical Futility Cases.” Poster presented at the annual meeting of the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities, Atlanta, October 24–27.

- Rachels, J., and S. Rachels. 2011. The Elements of Moral Philosophy. New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

- Siegler, M. 2001. “Lessons from 30 Years of Teaching Clinical Ethics.” Virtual Mentor 3 (10). Accessed July 3, 2014. http://virtualmentor.ama-assn.org/2001/10/medu1-0110.html

- Solomon, M. Z., D. M. Browning, D. L. Dokken, M. P. Merriman, and C. H. Rushton. 2010. “Learning That Leads to Action: Impact and Characteristics of a Professional Education Approach to Improve the Care of Critically Ill Children and Their Families.” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 164 (4): 315–322.

- Wentworth, J., and J. R. Davis. 2002. “Enhancing Interdisciplinarity through Team Teaching.” In Innovations in Interdisciplinary Teaching, edited by C. Haynes, 16–37. Westport, CT: Oryx Press.