ABSTRACT

Respeaking is an effective way to make live and pre-recorded television, as well as live events, accessible to a wide audience. Respeakers use speech-recognition software to repeat or paraphrase what is heard through a microphone in a robotic voice while enunciating punctuation and adding colours or labels to identify the speakers. Until now, most respeaking has been done within the same language (intralingual respeaking). As a recent development, interlingual respeaking has the potential to provide a new access service for a wider audience, including those with hearing loss, language learners, foreigners, migrants, refugees, etc. To ensure quality, respeakers must receive systematic and appropriately designed training. As part of the EU-funded project Interlingual Live Subtitling for Access (ILSA), whose goal is to develop a training course for interlingual live subtitlers, this paper presents the results of the largest experiment on interlingual respeaking conducted so far. The aim was to identify the skills required for interlingual respeaking and determine the best-suited professional profile for an interlingual live subtitler to inform training. The results show a varied and complex landscape where subtitlers and interpreters must learn different skills to perform effectively as interlingual respeakers.

1. Introduction

Over the past decades, the need to provide access to audiovisual media for various audiences has positioned media accessibility (MA) as one of the most thriving areas of research, training and professional practice in the field of audiovisual translation (AVT). As a matter of fact, although MA has traditionally been considered a subarea within AVT devoted to specific groups of users like the d/Deaf and the blind, some researchers are now adopting a wider or universalist approach (Greco Citation2018). In their view, MA is not only intended for people with hearing or sight loss but also for anyone who, for whatever reason (language-related, age-related, etc.), may not have access to original audiovisual content, thus blurring the boundaries between MA and AVT.

Given the importance of live programmes for TV viewers (Romero-Fresco Citation2015), live subtitling is a key practice within MA. Of the different methods currently available to produce live subtitles, stenography and respeaking are the most popular, the latter being:

a technique in which a respeaker listens to the original sound of a (live) programme or event and respeaks it, including punctuation marks and some specific features for the deaf and hard-of-hearing audience, to a speech-recognition software, which turns the recognized utterances into subtitles displayed on the screen with the shortest possible delay.

(Romero-Fresco Citation2011, 1)

Although the process involved here is one of (intralingual) simultaneous interpreting, and that the interpreting community initially showed interest in it (Marsh Citation2004; Baaring Citation2006; Mack Citation2006; Remael and van Deer Veer Citation2006; Eugeni Citation2008), respeaking is now regarded as a new mode within AVT. This is reflected in respeakers’ working conditions, including remuneration, which are closer to those of pre-recorded subtitlers than to those of interpreters, and in their training, which is normally delivered as part of AVT courses or in-house by subtitling companies (Robert, Schrijver, and Diels Citation2019a).

Recently, the need to provide access to live programmes and events delivered in a foreign language has triggered a demand for interlingual live subtitling (ILS), through interlingual respeaking, or transpeaking (Pöchhacker and Remael Citation2019). However, given that, as shown by these authors, the addition of language transfer to respeaking turns it into a more complex task than simultaneous interpreting, a few questions arise: is high-quality interlingual respeaking attainable? What are the main task-specific skills required? How can these skills be trained? What is the most suited professional profile?

As an output of the EU-funded Erasmus+ project ILSA (Interlingual Live Subtitling for Access) and in an attempt to answer some of these questions, Section 3 presents a summary of a large-scale online experiment that was informed by a small-scale pilot experiment (Dawson Citation2019). The aim of the large-scale experiment was to identify the skills required for interlingual respeaking and to determine the best-suited professional profile for an interlingual live subtitler to inform future training. While Section 2 describes the methodology of the experiment, Sections 3 and 4 present the quantitative and qualitative results obtained. This is followed by a discussion on the nature and development of interlingual respeaking training (Section 5) and a final conclusion (Section 6).

2. Main experiment: methodology

2.1. Design

An integral part of the methodology of the large-scale experiment took a train, practice and test approach, which involved delivering an online interlingual respeaking course to train 50 participants and allowing them to practice interlingual respeaking before testing their performance. This enabled participants from different backgrounds to reach a similar respeaking standard before being tested.

The course, delivered via the online platform Google Classroom, lasted 4 weeks and included three weekly sessions on dictation, intralingual respeaking (Spanish into Spanish) and interlingual respeaking (English into Spanish), followed by an interlingual respeaking test.

In the first week, participants answered a pre-experiment questionnaire about their profile, background, language competence, expectations on their performance and the ideal skills and background for an interlingual respeaker. They also watched a few videos illustrating respeaking in action and carried out dictation practice in order to train their voice profiles and to get familiarised with the speech-recognition (SR) software. The second week introduced intralingual respeaking and guidelines on how to successfully complete the task, including tips on error correction, multitasking step-by-step, pace, pauses, intonation, punctuation, using visual clues and dealing with omissions and condensation. Participants were set reading tasks to foster subtitling skills such as condensation (Díaz-Cintas Citation2003, 205–208), reformulation (Díaz-Cintas and Remael Citation2007, 150–161), punctuation (Romero-Fresco Citation2011, 101–106) and rhythm in respeaking (ibid, 107–111). Participants were asked to complete two intralingual respeaking exercises (section 3.1). The third week introduced interlingual respeaking with guidelines on delay, décalage, monitoring textual output, anticipation, and omissions and condensation in language transfer. There was also an introduction to the importance of interpreting skills, with literature on effort models in interpreting (Gile Citation2009, 157–174) and split attention (Romero-Fresco Citation2011, 95–101), before completing two interlingual respeaking exercises. Finally, in week four, participants took two interlingual respeaking tests and answered a post experiment questionnaire which collected information on their perceived performance, the course resources they found useful and the skills and professional background best suited to interlingual respeaking.

2.2. Material

illustrates the genre, duration and speech rate of the videos respoken by the participants. In weeks 2 and 3, participants were given the option to watch each video (V1–V4) before respeaking it and were able to train Dragon with potentially difficult terms. In week 4, participants were instructed to respeak the two test videos (V5–V6) without watching them beforehand. They used Dragon and Screencast-O-Matic, which proved very useful when assessing recognition errors.

Table 1. Details of video clips used during the experiment

2.3. Participants

Of the 46 native Spanish participants who took part in the course, only the performance of 44 could be analysed. As they all had previous interpreting and/or subtitling experience, two groups were established: interpreters and subtitlers.

Each group had participants with a ‘clear-cut’ background of only interpreting/subtitling training, and participants with a background of mainly interpreting training with some subtitling experience and vice versa. The interpreting group was made up of 27 participants, of which 13 had a clear-cut interpreting background (with an average of 17 months interpreting training) and 14 had an interpreting background with some subtitling experience (with an average interpreting training of 15 months and average subtitling training of 4 months). Of the subtitling group, 10 participants had a clear-cut subtitling background (with an average of 3.4 months of subtitling training) and 7 participants formed a group of subtitlers with some interpreting experience (with an average subtitling training of 15 months and average interpreting training of 7 months).

Regarding the demographic of the sample (), 34 were female and 10 male, with an average age of 25, the youngest being 21 and the oldest 40. Most participants had a language-related degree and were completing, or had already completed, a PG course.

Table 2. Details of participants

Table 3. Intralingual accuracy rates of each group

Table 4. Average translation errors for all subgroups

Table 5. Average recognition errors for all subgroups

Table 6. Effective editions vs. content omissions by group

Table 7. Interlingual accuracy rates of each group

2.4. Quality assessment

A total of 264 texts were analysed, which amounts to approximately 135,000 words, 7500 subtitles and 140 hours of respeaking practice. The 88 intralingual texts (two for each of the 44 participants) were assessed with the NER model (Romero-Fresco and Martínez Citation2015), shown in , which is widely used to assess intralingual live subtitling and has been adopted by bodies like the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC Citation2019). The NER model is also recommended by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the United Nation’s agency that is responsible for information and communication technologies (ITU Citation2019, 6). The NER model draws upon the basic requirements of the WER (Word Error Rate) model (Dumouchel, Boulianne, and Brousseau Citation2011), while emphasising the need for human intervention. It considers the number of words in the respoken text (N), the number of edition errors caused by strategies applied by the respeaker (E) and the number of recognition errors that are usually caused by mispronunciations, mishearing or errors with the SR technology (R). These errors can in turn be classified as minor (an error that can be recognised or the loss of a small piece of information), standard (an error that causes confusion or the loss of a large piece of information, such as a full sentence) or serious (an error that introduces information that is false/misleading but also credible in the context in which it occurs). The threshold for a set of intralingual live subtitles to be considered acceptable is 98%, which has been found to be in line with the users’ subjective views in different countries (2016Working Group Citation2018; Szarkowska et al. Citation2018). The need for human intervention is highlighted through the two additional elements of the model: correct editions (CE), which account for editing that has not caused a loss of information, and the final assessment, in which the evaluator can comment on issues such as speed, delay and flow of the subtitles.

Figure 1. The NER model (Romero-Fresco and Martínez Citation2015, 32)

The 176 interlingual texts (four for each of the 44 participants) were assessed with the NTR model (Romero-Fresco and Pöchhacker Citation2017), presented in , which considers the number of words in an interlingually respoken text (N), the translation errors (T) and the recognition errors (R) to calculate the accuracy rate. Thus, the NTR model uses a NER-based formula and accounts for the shift from intralingual to interlingual by replacing edition errors (E) with translation errors (T). The latter are in turn subdivided into content (omissions, additions and substitutions) and form (correctness and style) errors. As in the NER model, errors are also classified according to three degrees of severity (i.e. minor, major and critical) and the minimum accuracy rate required is 98%. For this experiment, the accuracy rate has been converted to a 1/10 scale, where 98% is 5/10 and 100% is 10/10. Although quality assessment models such as the NTR model focus on the end product, they can also be used in training as a form of self-assessment as the quantities of errors could aid trainees to identify their strengths and weaknesses in interlingual respeaking (Dawson Citation2020).

Figure 2. The NTR model (Romero-Fresco and Pöchhacker Citation2017)

As far as evaluation workflow is concerned, a sample of the 88 intralingual respoken texts from V1 and V2 and the 88 interlingual respoken texts from V3 and V4 was second marked and the amendments were applied to all texts by the first marker. All 88 interlingual tests, V5 and V6, were first and second marked. The inter-rater disagreement, or difference between the first and second markers assessment, of intra- and interlingual respoken texts was 0.16% and 0.19%, respectively. This figure was calculated by averaging the difference between first and second marking for the 264 respoken texts produced by the 44 participants in this experiment. The inter-rater disagreement obtained in the Ofcom study (Romero-Fresco Citation2016) and the LiRICS project (Romero-Fresco et al. Citation2019) was 0.09% and 0.24%, respectively, though both studies were on intralingual live subtitling. Despite the difficulty in assessing the quality of a live translation,Footnote1 as there can be various ways to convey a message, subjectivity when using the model does not appear to be a concern, as the overall inter-rater disagreement (0.19%) is very low and is the equivalent of a change in accuracy rate of 0.5 in a scale of 1–10, which may be regarded as satisfactory.

3. Quantitative results

The overall results show that the training delivered may be sufficient to provide high-quality intralingual live subtitles (98.24%, 5.5/10) but not high-quality interlingual live subtitles (97.36%, 3.5/10). Still, the results for interlingual respeaking are not far off the threshold for good quality, which means with longer training it may be feasible. The following section takes a closer look at the performance of each group of participants: the interpreters and the subtitlers.

3.1. Intralingual results

V1 and V2 were used to respeak intralingually from Spanish into Spanish. Participants obtained a significantly lower accuracy rate in V1 with 98.05% (5/10) than in V2 with 98.45% (6/10).

Minor errors are the most common edition errors made in the intralingual exercises, with an average of 5.9 errors (penalised at −0.25) made per participant per video. On average, 1.6 standard errors (penalised at −0.5) and 0.6 serious errors (penalised at −1) were made. The most common recognition errors, caused by the participants’ use of Dragon, in the intralingual exercises are minor errors (9.2), followed by standard errors (3.5) and then serious errors (0.5). Participants made fewer correct editions in V1 (2.5) than in V2 (34.1). The higher speed of V2 introduces the need to condense more text to keep up with the source text. The difference in content could also be significant as V1 was delivered in a structured way and was carefully pre-prepared, while V2 was delivered spontaneously and contained filler words and repetitions.

The interpreters achieved the highest accuracy rate for intralingual respeaking (Spanish into Spanish) with averages of 98.28% (5.5/10) for the clear-cut interpreters and 98.46% (6/10) for the interpreters with subtitling training, which points to the need to develop skills from both areas to perform well. In the clear-cut interpreting group, the high performers achieved 99.14% (8/10) while the low performers achieved 97.55% (4/10). Although many professional intralingual respeakers that work in media corporations are not interpreters (Robert, Schrijver, and Diels Citation2019a), these results show that high-performing interpreters are immediately well positioned to work as intralingual respeakers, as they are accustomed to listening and speaking at the same time.

The clear-cut subtitlers achieved 97.98% (4/10) and subtitlers with some interpreting experience achieved 98.11% (5/10). It appears that having only subtitling experience may not be enough to perform well with such little training. Subtitlers may require further and longer training, as, unlike interpreters, they are not used to having to produce and vocalise such immediate translations.

3.2. Interlingual exercises

V3, V4, V5 and V6 were used by participants to complete interlingual respeaking exercises (English into Spanish). The following sections offer an analysis of the translation and recognition errors made by the interpreting and subtitling groups. Participants obtained a lower accuracy rate in V4 (96.81%) than in V3 (97.56%), V5 (97.45%) and V6 (97.69%). As the differences between accuracy rate and subgroup were not statistically significant, it suggests that the participants’ background may not play a part in interlingual respeaking performance; however, this will become clearer with an analysis of translation and recognition errors for all groups.

3.2.1. Translation errorsFootnote2

Translation errors can be assessed as either content errors or form errors. Definitions for each subtype of translation error and examples can be found below.

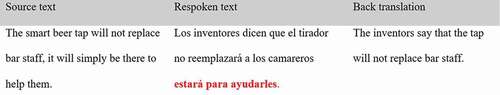

Content omission (cont-omiss) errors are omitted text of dependent or independent idea units. shows respeaker has omitted the idea “it will simply be there to help them”. This is an omission of a dependent idea unit (the ‘what’ piece of information) and so it is a minor content omission error.

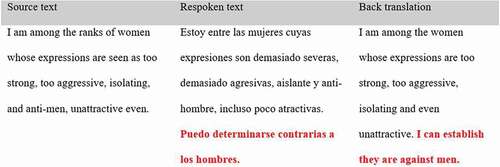

Content substitution (cont-subs) errors are substituted text that results in a mistranslation. highlights the respeaker’s translation introduces the opposite meaning than what is in the source text, so this is a critical content substitution error.

Content addition (cont-add) errors are additions in the target text that do not appear in the original text. illustrates the respeaker has added a whole sentence that does not make sense. The addition concerns an independent idea unit and it is confusing, so it is a major content addition error.

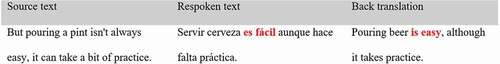

Form correctness (form-corr) errors refer to poor use of grammar or punctuation. shows the respeaker used a full stop instead of a question mark. The respoken text can be understood, so this is also a minor form-correctness error.

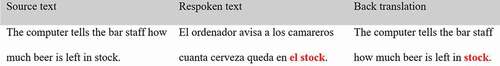

Form style (form-style) errors are variations in the appropriateness, naturalness and register of the text. demonstrates the respeaker should have made “stock” accessible and used the Spanish term “en reserva” instead of the English calque. The translation is unnatural, but it could still be understood so it is a minor error.

Effective editions (EE) are variations in the target text that do not cause any loss of information and could improve the target text (i.e. condensation of filler words and unnecessary repetitions). shows the respeaker has omitted ‘now’, ‘more or less’, ‘or so’ and the repetition of ‘much more’. The respoken text still maintains the main meaning and can be followed with ease as it is not as cumbersome as the source text.

The most common translation errors for every video and subgroup are omissions, followed by substitutions (mistranslations), whereas the least common are those related to grammar and style. Participants made on average 13.4 translation errors in V3, 22.8 in V4, 19 in V5, and 16.3 in V6. As for the groups, the clear-cut interpreters made the least amount of omissions, mistranslations and style errors, indicating that they were able to respeak more information, to translate more accurately and to maintain the register. The subtitlers made the least amount of addition errors, which implies that they did not have as much time as the other groups and could not add content, that they generally respoke less text or that they are not as used as the interpreters when it comes to creating coherence to fill gaps in the text.

3.2.1.1. Content errors

More minor omission errors were made than major, which indicates that participants were able to maintain the main idea of a sentence as they omitted dependent idea units (the who, what, where, when, why, how piece of information) as opposed to independent idea units (full sentences). V4 has the highest number of omissions, particularly major omissions. This could be due to challenging content and terminology that led participants to omit more full sentences. V3 has the lowest number of omissions and the simplest content, pointing to a correlation between the difficulty of the videos’ content and number of errors made. On the other hand, there is no correlation between speech rate and number of errors made.

It was expected that interpreters would be able to translate more concepts as they were thought to be more accustomed to producing an accurate live translation than subtitlers due to previous experience in this area. However, there was only one significant difference between the four groups: clear-cut interpreters made fewer major substitution errors (1) than interpreters with subtitling (2.5). Participants made more minor substitution errors in V4 (4) than in V3 (2.6) and V6 (2). Likewise, participants made more major substitution errors in V4 (2.6) than in V3 (1.6), V5 (1.3) and V6 (1.3). Again, this could be put down to the dense content of V4.

Interpreters showed signs of being able to produce a respoken text faster than subtitlers, with fewer major omission errors. The interpreters incurred more addition errors and may have had more time to add content, whereas the subtitlers could not always keep up with the content and made fewer additions.

3.2.1.2. Form errors

Participants made more minor form correctness (grammatical) errors in V5 (3.7) than in V3 (1), V4 (0.7), and V6 (1.4), showing that both groups made errors in which the correct forms could be recognised or that the mistakes could be recognised as errors as opposed to confusing an audience or introducing false meanings. Form style errors do not appear to cause difficulty for respeakers, nor contribute to substantial changes in accuracy rate.

3.2.2. Recognition errors

The most common recognition error for every group is minor and the least common error is critical, which demonstrates that participants from all four groups were either able to control error severity, or that minor errors are easier to make than major or critical errors. There are no significant differences in performance between the interpreters and the subtitlers for minor, major or critical errors. However, significantly fewer recognition errors were made in V4 (9.8) than in V3 (18.9), V5 (16.3) and V6 (18.6). Good recognition results for V4 could be put down to the participants respeaking less text and, therefore, having fewer chances of incurring recognition errors, or that they noticed the translation was not going well and so they chose to concentrate on clear dictation to obtain good recognition results instead.

Interpreters made the lowest number of recognition errors, further highlighting that previous interpreting training in speaking in a clear voice and delivering live translations may have contributed to the groups’ good results.

3.2.3. Effective editions

Edited text that does not cause loss of information would be scored as an effective edition, whereas any loss of information would be penalised as an omission. It appears that effective edition and content omission errors go hand in hand, as videos with a low number of omissions also have a low number of effective editions, and videos with a high number of omissions also have a high number of effective editions. Effective editions can be made unwillingly, for instance, if text has been omitted but it has not caused any loss of information it would be scored as an effective edition, but the respeaker may have opted to omit text through not being able to keep up or not understanding the source text.

There is a significant difference in the number of effective editions made, as participants made fewer effective editions in V3 (2.5) than in V4 (6.6), V5 (4.3) and V6 (4.3). V3 had the simplest content, therefore, is expected to have been easier to translate. No significant differences were observed between interpreters and subtitlers. Effective editions may be good to keep a reasonable display rate of subtitles that can be viewed comfortably so, from a didactic perspective, trainees should understand the negative impact that omissions can have on a respoken text and the positive impact that effective editions can have.

The clear-cut interpreters made the lowest amount of omission errors and effective editions, which highlights they were able to keep up with the original without omitting or condensing information. The groups with a higher number of omissions and the most effective editions were not able to keep up and therefore did not respeak as much text.

3.2.4. Analysis of overall interlingual performance

The clear-cut interpreting group achieved the highest average accuracy rate for interlingual respeaking with 97.78% (4.5/5), followed by the subtitlers with interpreting (97.36%, 3.5/10), the clear-cut subtitlers (97.30%, 3.5/10), and the interpreters with subtitling (97.05%, 2.5/10). It should be noted that the high-performing group of interpreters obtained an average of 98.57% (6.5/10) and the low-performing group achieved 97.07% (2.5/10), which shows that the difference between high- and low-performing interpreters is greater than the difference between interpreters and subtitlers.

These overall results highlight that if more training is provided to deal with translation and recognition errors, the performance of trainees should be of a higher standard. As there were no significant differences between the interpreters’ and the subtitlers’ performance, it appears that the success of interlingual respeaking training depends on how individuals perform and their ability to develop and build upon the required task-specific skills, rather than the particular professional profile of individuals. The low-performing participants, whether interpreters or subtitlers, will need to develop their skills further to perform well.

4. Qualitative results

4.1. Level of difficulty

Regarding the level of difficulty of the test, 21 of the 44 participants (48%) rated it as very difficult or difficult, 18 (41%) rated it as sound and 5 (11%) as easy. There is no correlation between participant performance and perceived level of difficulty. Speech rate was ranked as the most difficult aspect to deal with by all groups, even though it does not seem to have played a significant role in the quantitative results. All subtitlers and interpreters deemed V1 and V2 as the easiest videos to respeak, most likely because they were both intralingual exercises and the added difficulty of language transfer was not present. The most difficult interlingual video to respeak, which indeed caused the lowest accuracy rate despite its speech rate not being the highest one, was the interview in V4 because of its specialised vocabulary and dense content.

4.2. Opinion of the course

The training delivered for the experiment met the participants’ expectations. Many of them (28, 64%) mentioned they wanted to gain an idea of how respeaking works as well as the skills and tasks required for the job and 14 (32%) wanted to find out how the software worked. Seven participants (15%) mentioned the course was too short to master the required skills and one participant specifically noted that an intra- or interlingual respeaking course could take up a whole semester or even an academic year.

Videos for reference and readings about respeaking were found to be useful for all groups and were rated higher than readings on subtitling or interpreting, perhaps because participants were already familiar with those subjects. A total of 29 (66%) respondents deemed communicating with others via the online forum to be the least useful resource.

4.3. Participants’ opinion of the task-specific skills required for an interlingual respeaker

When asked about the task-specific skills that a professional interlingual respeaker should have, all groups deemed multitasking, live translation and dictation skills to be the most important. Language and comprehension skills were also rated highly.

Other skills noted by the interpreting group were proficient knowledge of language and culture, concentration, managing stress or pressure and quick thinking. The subtitling group noted knowledge about subtitling, condensation, knowledge of current affairs and the ability to remain calm and focussed while respeaking. Participants with mixed backgrounds highlighted skills required for both disciplines, such as memory (especially short-term memory) and split attention skills. Some participants also noted patience and anticipation as important characteristics for an interlingual respeaker.

4.4. Participants’ opinion of the best-suited professional profile required for an interlingual respeaker

Out of five options: an interpreter, intralingual respeaker, subtitler, translator and a linguist, participants highly rated an interpreter to be the best-suited profile for an interlingual respeaker. This was closely followed by an intralingual respeaker. Participants did not think a subtitling or translation background would be suitable and considered linguistics to be the least suited background.

5. Discussion on interlingual respeaking training

Research has been connected to intralingual respeaking training, as recommendations for a scaffolded training proposal have been put forward by Fresno and Romero-Fresco (CitationForthcoming), which is based on empirical findings of the pilot project QualiSpain. In a similar way, the empirical results presented in this article have shed light on important aspects that should be borne in mind when developing interlingual respeaking training. This discussion considers results from the intra- and interlingual respeaking exercises and offers recommendations for potential course structure, modules and exercises for dictation, intralingual respeaking, sight translation, interlingual respeaking and quality assessment.

Participants who achieved good accuracy rates in intra- and interlingual respeaking experienced minimal technical issues and dictated clearly, with good volume and at a steady pace. These results show that extensive dictation and software practice is needed to train the voice profile and reduce recognition errors. Clear-cut interpreters appeared to have an advantage with dictation and achieved the best recognition results, most likely because they were already accustomed to delivering live translations, which requires them to enunciate clearly and avoid hesitation. When it comes to enunciation, the difference between interpreting and respeaking is that in the latter case the translation must be dictated rather than spoken in a pleasant tone, which requires becoming accustomed to the software and its functionality. Ensuring that all trainees can master the SR software by dictating clearly, using pauses correctly, maintaining the rhythm of the source text, using the microphone correctly, making live corrections to reduce errors and creating and working with macros to save valuable time and avoid recognition errors are all essential to achieving good results.

To keep recognition errors to a minimum, a module on dictation and software management could be beneficial before carrying out any intra- or interlingual respeaking practice. An essential part of using SR software is understanding the basic mechanics of how it works, so initial tasks could entail trainees exploring different types of software, such as Web Captioner and Dragon to compare them. Dictation exercises should include easy-to-read texts that only require the use of the three basic commands that are always needed such as ‘comma’, ‘full stop’ and ‘question mark’. Then, trainees can expand their use of custom commands and use less frequent ones such as ‘exclamation mark’, ‘brackets’, ‘quotation marks’, etc. Although not explored in the large-scale experiment, trainees should also be encouraged to create custom commands to include information needed by a d/Deaf audience such as for speaker identification and sound labels. If using Dragon in a subtitling software such as WinCaps Q4 trainees could also experiment with using colours for speaker identification.

The top performers in the intralingual respeaking exercises also performed well in interlingual respeaking and reached the 98% threshold overall, indicating that it may be necessary for training to start with intralingual respeaking before adding the extra complexity of language transfer. Given the similarities between interpreting and respeaking at the process level, it may also be beneficial to include a module on simultaneous interpreting, either preceding or running alongside an intralingual respeaking module. This would allow trainees to learn interpreting techniques that they can then apply to intralingual respeaking. Initial intralingual respeaking practice could include five respeaking exercises to introduce trainees to the five tasks involved in respeaking: (1) listening to the source text, (2) respeaking the target text, (3) monitoring the output, (4) watching the images on screen and (5) correcting the target text. Trainees could be asked to add a step for each exercise they complete so they progressively work up to the full respeaking task. Audiovisual material could also be organised in order of difficulty, so trainees could start off by respeaking slow speeches, then sports, the news and finally interviews.

An interesting aspect to consider is the question of whether intralingual respeaking training is needed for a simultaneous interpreter to become an interlingual respeaker. As shown above, dictation practice with the software is essential, but it may be possible to skip intralingual respeaking practice and move on directly to respeaking with language transfer. This would be difficult to organise in a university setting but may be applicable in a professional context for language professionals who are looking to add interlingual respeaking to their simultaneous interpreting or intralingual respeaking profile. On the other hand, the excellent results obtained in intralingual respeaking by the interpreting group shows that this intralingual training may offer simultaneous interpreters a new promising job opportunity. This is even more relevant now that the demand for interlingual respeakers is rising, as broadcasters consider the service especially for live events (Robert, Schrijver, and Diels Citation2019b). Companies have their own intralingual respeaking training but training in interlingual respeaking is yet to be developed (Robert, Schrijver, and Diels Citation2019a). In universities, only the University of Vigo and the University of Antwerp have full courses in respeaking.

Sight translation could be seen as the interlingual equivalent of the dictation practice that trainees will have explored at the beginning of training. To prepare trainees to progress from intra- to interlingual respeaking, the language transfer process could also be introduced with the help of sight translation exercises that would allow trainees to read a text (in their head) in one language and dictate the translation into another language, but without the time pressure of producing a live translation and keeping up with a video.

For interlingual respeaking exercises, audiovisual materials should cover different genres, topics and speech rates and be chosen carefully in order of difficulty, so that they contribute to the trainees’ progression. Introducing videos with easy content, a low speech rate and long pauses would allow trainees to listen and speak at the same time. Increasing speech rates, content difficulty and density with each exercise would give trainees a sense of progression and would allow them to minimise recognition errors, which are far easier to tackle than translation errors. In this respect, an interlingual respeaking module could be split into three levels of difficulty: (1) easy with speech rates of 100–140 wpm, (2) intermediate at 140–180 wpm and (3) advanced at 180–220+ wpm. The nature of easy audiovisual material for TV may include slow speeches and non-specialised documentaries that are typically delivered slowly, by one speaker, with frequent pauses. Intermediate material may include sports and weather, which contain visual elements that a viewer would have access to so a respeaker can respeak less content when the information is already available on screen. Advanced material could include multiple speakers and more difficult and dense content such as the news, chat shows, interviews and parliamentary debates. Material for live events could take the form of lessons delivered in classrooms, church services, conferences and other public events. During the preparatory phase of each respeaking task, trainees could create word lists with unfamiliar names and relevant terminology that may not be recognised by the SR software but is needed to respeak the material. Prior preparation could reduce the chances of incurring recognition errors and help trainees to achieve good results from the start.

Aside from interlingual respeaking practice being organised by level of difficulty, it may also be advantageous for tasks to focus on the five subtypes of translation error: (1) content omissions, (2) substitutions, (3) additions, (4) form correctness and (5) style errors. Content omission errors were the most common in the large-scale experiment, accounting for 53% of translation errors overall, followed by content substitutions (36%). These results show that keeping up with the text, understanding the original dialogue and producing an accurate live translation are challenging tasks. Specific exercises should be designed to hone these skills and make trainees aware of the causes and consequences of such errors. An example of an exercise could be for trainees to pay attention to omissions, highlighting the communicative importance of dependent and independent idea units. Trainees could be asked to analyse the transcript of the source text and to identify the dependent and independent idea units and the impact that their omission would have on the target text. When submitting an NTR analysis, trainees could be asked to answer questions such as: How many of your errors were caused by omitted text? How many omissions were due to missing dependent idea units? And how many were due to independent idea units? A similar approach could be taken around content substitution errors and once a respeaking exercise and quality assessment have been carried out trainees could collectively reflect on their performance and share information on the following questions: How many of your errors were caused by mistranslated text? How serious are the errors? Can the message be understood? Do they cause loss of information? Do they introduce false information? Have you managed to achieve fewer mistranslations than in the previous text? How do you think you can avoid mistranslations errors?

Training in quality assessment may be of benefit as the correct use of the NTR model could allow trainees to analyse the accuracy rates of their own texts and to identify errors and their severity. This could afford trainees a better understanding of how and why translation and recognition errors are made, giving them space to reflect on their strengths and weaknesses and to develop techniques to manage errors or avoid them altogether. Encouraging peer review tasks among trainees can help encourage their critical analysis skills and reduce subjectivity when analysing their own work.

5.4. Task-specific skills and best-suited professional profile

In terms of the task-specific skills required for interlingual respeaking, multitasking was rated as the most-needed skill, followed by live translation and dictation, making this practice more complex than simultaneous interpreting (Pöchhacker and Remael Citation2019). illustrates all task-specific skills that came to light during the experiment, all of which should be trained through task-specific exercises:

Although there were high and low performers within the interpreting and subtitling groups, the quantitative results show that those with more interpreting experience tended to perform better than those with solely subtitling experience and were at their best in terms of recognition and translation errors. The high-performing interpreters were strong live translators and were able to keep up with the speed of the videos and with the multitasking involved in respeaking. Much like the high-performing interpreters, participants that performed well in the subtitling group had clear dictation, good live translation skills and seemed to keep up with the text.

Questionnaire responses show that most participants deemed interpreters and intralingual respeakers to be the best-suited professional profiles for interlingual respeaking. And, although it appears that interpreters may be initially better equipped to deal with the complexity of interlingual respeaking, those with a subtitling background also have, or may be able to acquire, the necessary task-specific skills to perform well. In this sense, the most important aspect may be the development of the task-specific skills that they lack from previous experience rather than having a particular professional profile.

6. Conclusions

The experiment on interlingual respeaking presented in this article provides some tentative answers to the four questions posed in the introduction: (1) Is high-quality interlingual respeaking attainable?; (2) What are the main task-specific skills required?, (3) How can these skills be trained?; and (4) What is the most suited professional profile?

Firstly, although the average accuracy rate obtained by the participants in the experiment (97.37%, 3.5/10) does not meet the required 98% threshold, it can still be hailed as a good result considering that they only had three weeks of training and that some, mostly from the interpreting group, managed to obtain percentages over 98% for some of the videos. The duration of the training may be a crucial factor. Indeed, in a recent online interlingual respeaking course delivered by the University of Vigo, Spain, after eight weeks of training, the average accuracy rate for the 16 videos respoken interlingually by all seven trainees was 98.14% (5.5/10), with some of them obtaining an overall average accuracy rate of 99% (8/10). Time and professional practice will tell whether interlingual respeaking can obtain good results in all contexts (e.g. television, live events) and for all types of material, but these initial results suggest that it is indeed feasible.

Secondly, drawing on both the participants’ performance and their opinion, the top three most important task-specific skills involved in interlingual respeaking are dictation, multitasking and live translation. Dictating in a clear manner is essential to avoid or reduce recognition errors and can be acquired with extensive dictation and software practice. Trainees should be able to find a personal dictation mode that works for them and enables them to obtain near-perfect accuracy when speaking to the SR software. Multitasking, which in this case involves listening and speaking at the same time without being distracted, will allow trainees to keep up with the original text to avoid omissions which have proved to be the most recurrent translation issue. Producing a fast and accurate live translation is essential to avoid substitutions (mistranslations), which is the second most recurrent translation error. To hone these skills, trainers should resort to multitasking exercises, providing trainees with videos of increasingly fast speech rates and complex terminology and adopting a paced approach to multitasking and live translation. This could involve trainees first few exercises to be only listening + speaking; then the next few exercises listening + speaking + watching the screen; then, finally, listening + speaking + watching the screen + correcting on-screen errors. This would allow trainees to build up to the complex task of interlingual respeaking little by little.

Finally, participants with an interpreting background performed generally better than subtitlers, though this does not mean that all simultaneous interpreters automatically qualify to be interlingual respeakers or that subtitlers should not be considered for this job. The greatest difference in performance has not been found between (clear-cut) backgrounds, but between high- and low-performing interpreters and subtitlers. High performing interpreters seem very well positioned to produce interlingual respeaking as long as they manage to add certain aspects to their skills set (knowledge about subtitling for the deaf and hard of hearing, oral punctuation) and adapt others (from speaking in a natural and pleasant tone to dictating in a monotonous tone for the SR software). Likewise, good quality interlingual respeaking can also be produced by intralingual respeakers with knowledge of foreign languages and strong live translation skills and also by subtitlers with the ability to dictate clearly as well as good multitasking and live translation skills. Given that most translation and interpreting students at higher education institutions are likely to receive training in both areas, it may make sense for interlingual respeaking training to have specific pre-requisites of simultaneous interpreting or interlingual subtitling so that students will already have knowledge on the process or the product respectively. Tutors would also need to be aware of the students’ backgrounds and pay special attention to the skills that are needed by either group.

To conclude, it is hoped that this analysis and discussion can be embraced to help inform future training in interlingual respeaking. After all, interlingual respeaking has the potential to provide full written access to audiovisual productions and live events not only for viewers with hearing loss but for those with a language barrier too.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and conducted within the framework of the EU-funded project ILSA (Interlingual Live Subtitling for Access), under Grant 2017-1-ES01-KA203-037948.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In this article, live translation is referred to both as a task-specific skill required for interlingual respeaking and as a process of listening in one language and speaking in another (Dawson Citation2020).

2. Due to zero or close to zero variance, models for critical content omission, substitution, addition and form correctness and style errors were not calculated.

References

- 2016Working Group. 2018. “Findings and Proposal of the 2016Working Group.” 16 January. https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/archive/2019/2019-9.htm

- Baaring, I. 2006. “Respeaking-based Online Subtitling in Denmark”. InTRAlinea, (Special Issue: Respeaking). http://www.intralinea.org/specials/article/Respeaking-based_online_subtitling_in_Denmark

- CRTC 2019. “Broadcasting Regulatory Policy CRTC 2019-308.” Ottawa: Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. August 30. https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/archive/2019/2019-308.htm

- Dawson, H. 2019. “Feasibility, Quality and Assessment of Interlingual Live Subtitling: A Pilot Study.” Journal of Audiovisual Translation 2 (2): 36–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.47476/jat.v2i2.72.

- Dawson, H. 2020. “A Research-informed Training Course for Interlingual Respeaking.” Journal of Audiovisual Translation 3 (3): 204–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.47476/jat.v3i2.2020.126.

- Díaz-Cintas, J. 2003. Teoría y práctica de la subtitulación: Inglés – Español. Barcelona: Ariel.

- Díaz-Cintas, J., and A. Remael. 2007. Audiovisual Translation: Subtitling. Manchester: St Jerome.

- Dumouchel, P., G. Boulianne, and J. Brousseau. 2011. “Measures for Quality of Closed Captioning.” In Audiovisual Translation in Close-up: Practical and Theoretical Approaches, edited by A. Şerban, A. Matamala, and J.-M. Lavaur, 161–172. Bern: Peter Lang. doi:https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-0351-0209-3.

- Eugeni, C. 2008. “A Sociolinguistic Approach to Real-time Subtitling: Respeaking Vs. Shadowing and Simultaneous Interpreting.” In English in International Deaf Communication, edited by C. J. Kellett Bidoli and E. Ochse, 357–382. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Fresno, N., and P. Romero-Fresco. Forthcoming. “Strengthening Respeakers’ Training in Spain: The Research-practice Connection.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer.

- Gile, D. 2009. Basic Concepts and Models for Interpreter and Translator Training. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Greco, G. M. 2018. “The Case for Accessibility Studies.” Journal of Audiovisual Translation 1 (1): 204–232. doi:https://doi.org/10.47476/jat.v1i1.51.

- ITU. 2019. “Technical Paper.” Geneva: International Telecommunication Union. 17 October. https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-t/opb/tut/T-TUT-FSTP-2019-ACC.RCS-PDF-E.pdf

- Mack, G. 2006. “Detto Scritto: Un Fenomeno, Tanti Nomi.” InTRAlinea (Special Issue: Respeaking). http://www.intralinea.org/specials/article/Detto_scritto_un_fenomeno_tanti_nomi

- Marsh, A. 2004. “Simultaneous Interpreting and Respeaking: A Comparison.” MA diss., University of Westminster.

- Pöchhacker, F., and A. Remael. 2019. “New Efforts? A Competence-oriented Task Analysis of Interlingual Live Subtitling.” Linguistica Antverpiensia 18: 130–143.

- Remael, A., and B. van Deer Veer. 2006. “Real-time Subtitling in Flanders: Needs and Teaching.” InTRAlinea (Special Issue: Respeaking). http://www.intralinea.org/specials/article/Real-Time_Subtitling_in_Flanders_Needs_and_Teaching

- Robert, I. S., I. Schrijver, and E. Diels. 2019a. “Live Subtitlers Who are They? A Survey Study.” Linguistica Antverpiensia 18: 101–129.

- Robert, I. S., I. Schrijver, and E. Diels. 2019b. “Trainers’ and Employers’ Perceptions of Training in Intralingual and Interlingual Live Subtitling: A Survey Study.” Journal of Audiovisual Translation 2: 1–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.47476/jat.v2i1.61.

- Romero-Fresco, P. 2011. Subtitling Through Speech Recognition: Respeaking. Manchester: St Jerome.

- Romero-Fresco, P., and J. Martínez. 2015. “Accuracy Rate in Live Subtitling: The NER Model.” In Audiovisual Translation in a Global Context: Mapping an Ever-changing Landscape, edited by J. Díaz-Cintas and R. Baños-Piñero, 28–50. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137552891.

- Romero-Fresco, P. 2015. The Reception of Subtitles for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing in Europe. Oxford: Peter Lang.

- Romero-Fresco, P. 2016. “Accessing Communication: The Quality of Live Subtitles in the UK.” Language & Communication 9: 56–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2016.06.001.

- Romero-Fresco, P., and F. Pöchhacker. 2017. “Quality Assessment in Interlingual Live Subtitling: The NTR Model.” Linguistica Antverpiensia 16: 149–167.

- Romero-Fresco, P., S. Melchor-Couto, H. Dawson, Z. Moores, and I. Pedregosa. 2019. “Respeaking Certification: Bringing Together Training, Research and Practice.” Linguistica Antverpiensia 18: 216–236.

- Szarkowska, A., K. Krejtz, Ł. Dutka, and O. Pilipczuk. 2018. “Are Interpreters Better Respeakers?” Interpreter and Translator Trainer 12 (2): 207–226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2018.1465679.