ABSTRACT

This paper sets out to bridge the gap between theory and practice by suggesting activities and resources that could be used in the audiovisual translation (AVT) classroom when training students to achieve credible and natural-sounding dialogue in dubbing. Following a competence- and task-based approach, these activities have been implemented by the author when teaching English into Spanish dubbing at master’s level and explore the advantages of using translation technology (e.g. translation memory and corpus management tools) in the AVT classroom. When suggesting activities, the emphasis is also placed on what can be learnt from other disciplines, such as creative writing, and on the links that can be established with other subjects (e.g. translation technology) in order to improve future audiovisual translators’ instrumental competences and understanding of the specific features of original and dubbed audiovisual dialogue.

1. Introduction

The credibility and verisimilitude of dialogue is assumed to be one of the tacit criteria used by audiences worldwide to appraise fictional telecinematic productions, regardless of their origin. In the case of translated audiovisual material, and dubbed versions in particular, mirroring spontaneous conversation is of paramount importance, with the translator/dialogue writer taking the role of the scriptwriter and being expected to master the linguistic features available in the target language to produce convincing dialogue. Given this, it is no surprise that Chaume (Citation2007) considers credible dialogue to be one of the standards that determine the quality of a dubbed production, which is influenced by the translation itself, but also by technical and dramatisation-related aspects.

The importance of this standard is frequently discussed in social media (see the hashtag #traduconsejo used by Spanish translators, often in reference to audiovisual translation (AVT) scenarios) and has been foregrounded by the increasing demand of dubbed content, instigated by popular streaming platforms like Netflix over the past years. A recent article published in The New York Times discussed the effort this media conglomerate is placing on making dubbed programmes sound more spontaneous or less dubby, understood as ‘anything that is not speech-like – jarring diction or awkward wording – or is conspicuously out of time with how the actors mouths are moving onscreen’ (Goldsmith Citation2019, online). The article suggests this is part of Netflix’s intent on enhancing the prestige of dubbing, especially in the US, as well as shifting audience perception of this AVT mode as being inferior, of poor quality and often associated with parody.

Defined as ‘corrupt, deracinating and deodorising’ (Nornes Citation2007, 192), dubbing in general, and its language in particular, have been subjected to harsh criticism from scholars, intellectuals, viewers and film directors (Yampolsky Citation1993). This perception is not exclusive to regions where dubbing is not prevalent. In so-called dubbing countries, as is the case of Spain, scholars like Duro (Citation2001) have warned about the creation of a stilted, fake and contaminated language in dubbed versions. While some authors attempt to define the language of dubbing or dubbese objectively as ‘a culture-specific linguistic and stylistic model for dubbed texts’ (Marzà and Chaume Citation2009, 36), many others ‘have resorted to negatively connoted expressions such as fake, artificial, anti-realistic, stereotyped orality or language’ (Pavesi Citation2018, 104). The latter is supported by research reporting unnatural or unidiomatic uses of specific traits such as prosodic features (Baños Citation2014a; Sánchez-Mompeán Citation2019), discourse markers and intensifiers (Romero-Fresco Citation2009) or interjections (Matamala Citation2009), to name but a few.

Given the importance attached to achieving credibility and verisimilitude in dubbing, by both academia and the industry, it is worth reflecting on how this can be approached in AVT training. This is particularly relevant since didactic proposals with a focus on dubbing and its language are scarce with only some exceptions (Chaume Citation2008), and orality features are identified as a key topic to be included in dubbing and voice-over courses (Cerezo-Merchán Citation2018, 472). With this in mind, this paper sets out to bridge the gap between theory and practice, suggesting potential activities and resources that could be used in the AVT classroom when training students to achieve credible and natural-sounding dialogue in dubbing. In doing so, the article also highlights the usefulness of computer-aided translation (CAT) tools for the translation of fictional audiovisual programmes for dubbing purposes, discussed in detail elsewhere (Baños Citation2018).

Following a competence- and task-based approach, the emphasis will also be on what can be learnt from other disciplines (e.g. creative writing) and which links can be established with other subjects (e.g. translation technology) in order to improve future audiovisual translators’ instrumental competences and understanding of the specific features of telecinematic dialogue. The aim is therefore to put forward some didactic proposals to target two areas of paramount importance in AVT, i.e. creation of natural-sounding dialogue and knowledge of technological developments, which have not received enough attention in dubbing training so far. These proposals will be preceded by a brief introduction to the pedagogical and methodological approaches that have guided their design and implementation when teaching dubbing to postgraduate students in the UK.

2. Competence- and task-based approach in dubbing training

In line with extant pedagogical and methodological approaches to translation training in general, and to AVT training in particular, the proposals put forward in this article are envisaged to be implemented within a competence- and task-based approach. As Cerezo-Merchán (Citation2018) explains, competence-based training is a pedagogical approach to translation training that has gained significant ground in recent years and revolves around the notion of translation competence. The latter is made up of a set of sub-competences activated in every act of translation and is understood as ‘the underlying system of knowledge, skills and attitudes needed to translate’ (PACTE Group Citation2017, 294). Although some controversy surrounds the concept of translation competence (Kelly Citation2005) and there seems to be no general consensus among the scholarly community on which translation sub-competences comprise it, this term is widely used in Translation Studies and will be used throughout this paper.

Given that ‘little attention has been paid to unravelling how translation competence intertwines with the various AVT modes’ (Bolaños-García-Escribano and Díaz-Cintas Citation2019, 211), it is worth discussing this concept in the case of dubbing. In an attempt to identify the competences that make up the professional profile of audiovisual translators and drawing on the existing literature on translation competence in AVT training, Cerezo-Merchán (Citation2018) summarises audiovisual translation sub-competences as follows: contrastive competences, extralinguistic competences, methodological and strategic competences, instrumental competences and translation problem-solving competences. Yet, while some of these are common to all AVT modes, others are more central to specific types. For instance, it could be argued that some methodological and strategic competences are central to dubbing but not necessarily relevant to other AVT modes, e.g. mastery of revoicing techniques, mastery of techniques to comply with dubbing synchronies, use of symbols and timecodes for dubbing, and the capacity to analyse various genres and reproduce their discursive features (e.g. false orality). Regarding the latter, the list below illustrates how all five sub-competences are pivotal in the creation of natural and spontaneous-sounding dialogue in dubbing:

Contrastive competences, which encompass: (1) good understanding of how naturalness and pretended spontaneity are conveyed in the source language (SL) and in the target language (TL); and (2) mastery of the TL, especially as regards the use of orality markers or carriers, understood as ‘features typifying spontaneous spoken register used in prefabricated dialogue to reinforce its orality and to convey a false sense of spontaneity’ (Baños Citation2014a, 408–409);

extralinguistic competences, including (1) good knowledge of target audiences’ expectations and habits as regards dubbed dialogue; and (2) familiarity with the characteristics of audiovisual dialogue in a wide range of texts/genres (i.e. variations in their mode of discourse);

methodological and strategic competences, such as (1) the ability to analyse various genres and reproduce their discursive features (e.g. false orality) considering dubbing-specific constraints (capacity of synthesis and mastery of synchronisation techniques); and (2) the ability to use creative language resources to mirror spontaneous-sounding conversation;

instrumental competences, such as dexterity with strategies and relevant tools/software to retrieve information on orality markers in the SL and TL;

translation problem-solving competences, such as knowledge of translation strategies and techniques to translate different registers and dialogue exchanges with differing degrees of false orality.

This categorisation underlines the aspects to be targeted in class, highlighting how translation sub-competences can inform the design of tasks or activities aimed at the creation of credible and spontaneous-sounding dialogue. A task-based methodological approach (González-Davies Citation2004) is therefore embraced to enable students to practice specific skills and acquire particular sub-competences, in order to meet professional dubbing standards at a later stage. The emphasis is therefore placed on pedagogic activities, understood as concrete and brief exercises, which could also be part of a longer task with the same global aim. Likewise, they could be integrated in projects or ‘multicompetence assignments that enable the students to engage in pedagogic and professional activities and tasks and work together towards an end product’ (ibid, 28).

3. Didactic proposals for writing credible dialogue in dubbing

Following González-Davies (Citation2004), a step-by-step presentation is provided for each of the activities detailed below together with information about their main aims, approximate timing and grouping. As regards their level, these activities are targeted at master’s students and have been envisaged to be implemented in a Higher Education context, in the UK, in a module on voice-over and dubbing, whose learning outcomes are in line with those illustrated by Bolaños-García-Escribano and Díaz-Cintas (Citation2019). Nonetheless, the activities can be easily adapted to other levels and settings, and pitched accordingly. The materials needed are also included in the description. While priority is given to the use of authentic materials in order to enhance students’ employability and preparation for the dubbing industry, purposefully-created materials might be more suitable for initial tasks and to ensure a sound pedagogical progression.

The sub-competences addressed in each activity vary, with the first activities (1 and 2) having an emphasis on contrastive and extralinguistic competences. The focus then shifts towards methodological and strategic competences (3 and 5) and instrumental competences (6 and 7), while activity 4 could be said to address a wider range of competences and, in particular, translation problem-solving ones.

3.1. Activity 1. Audiovisual dialogue analysis: usage of orality markers

Aims:

To understand the nature of original audiovisual dialogue in the SL.

To reflect on how orality markers are used in texts with a slightly different mode of discourse as regards their degree of planification (oral spontaneous; oral semi-planned; and oral fully-planned, to be spoken as if not planned).

To identify what makes a text sound natural/spontaneous in a particular language and why.

To grasp key differences as regards the use of orality markers in the SL and TL.

Grouping: Individual, in pairs.

Approximate timing: 45 minutes.

Materials:

Table summarising key orality markers in the language studied (see Appendix A for a sample table with English as SL).

Written texts showing different degrees of orality.

Steps:

Part 1 – Familiarisation with orality markers

Students receive a table with a summary of key orality markers in the SL and are asked to read it carefully. They are also invited to ask questions, come up with scenarios in which such markers would normally be used, and provide further examples not included in the table. Depending on the focus of the course in which this activity is inserted, the discussion could delve deeper into topics related to sociolinguistics and pragmatics.

Part 2 – Analysis of orality markers

Students are provided with three short written texts: an extract from a spontaneous conversation that can be taken from an existing corpus such as the British National Corpus, an example from an interview in a documentary, and an extract from a conversation between characters from a film or series.

With the help of the table provided to them, students are asked to work in pairs to highlight which orality markers or features typical of spontaneous conversation are used in the various texts. While doing so, they are asked to reflect on how false orality or (pretended) spontaneity is achieved in these texts and to identify if features tend to belong to a specific language level, that is, phonetic, morphosyntactic or lexical level.

Students are asked to place the texts in the continuum shown in and to try to identify the origin of the texts provided. This can lead to interesting discussions on how different degrees of spontaneity are perceived by students, as well as on the role played by different orality markers.

The origin of the texts is revealed and a discussion on the contextual and linguistic differences between the three texts follows. If available, the oral/audiovisual versions of the texts can be played and/or screened to the class and discussed further.

As a follow-up activity, students could be asked to carry out this activity at home, in their TL, and compile a similar table to the one included in Appendix A. This could lead to pertinent discussions on differences between SL and TL orality markers in class or on online forums, through a virtual learning environment (VLE) such as Moodle.

3.2. Activity 2. Comparison of pre- vs. post-production scripts

Aims:

To understand the changes that original scripts undergo in audiovisual programmes.

To draw parallelisms between dialogue writing for original productions and for dubbing purposes.

To reflect on key notions such as synchronisation and improvisation in original productions and in dubbing.

Grouping: Individual, in pairs.

Approximate timing: 30–45 minutes (depending on the number/length of examples analysed).

Materials:

Written excerpts from pre- and post-production scripts.

Steps:

Students receive a document showing excerpts from pre- and post-production scripts arranged in two columns. An example in Spanish, taken from Baños (Citation2014b, 80), is displayed in , with additions and changes underlined in the post-production script. Ideally, examples should contain texts written originally in the SL and TL, so that students can establish further comparisons between both. Pre-production material can be difficult to source online, especially in some languages, but tutors can resort to existing publications such as Ruiz-Gurillo (Citation2013), for examples from stand-up comedy monologues in Spanish, or contact scriptwriters directly.

Table 1. Example of pre and post-production scripts from the Spanish sitcom Siete Vidas (Baños Citation2014b, 80)

Students are prompted to work in pairs to identify the differences between pre-production scripts and the final audiovisual dialogue received by the target audience, paying especial attention to orality markers. In , for instance, the focus can be on the addition of new orality markers introduced by actors when interpreting their lines (repetitions, hesitations, vocatives such as tío>mate), as well as on the richness of the Spanish language, in this case, and how important it is for translators to be familiar with this repertoire when looking for alternatives to comply with different types of dubbing synchronies. For example, both oye [listen] and bueno [well] are discourse markers that can be used in similar contexts depending on dubbing constraints. Students can also be asked to identify the potential reasons behind the changes, leading to a discussion on the ability of actors to improvise while recording a scene, and whether this is at all possible in dubbing.

Students are asked to share their findings with the rest of the class. If examples have been provided in both the SL and TL, differences and similarities could also be established during the discussion. Students could also be asked to reflect on whether specific orality markers, such as expletives and dialectal marks, can be considered appropriate in dubbed dialogue.

3.3. Activity 3. Dialogue writing in the TL

Aims:

To experience the challenges of scriptwriting as regards: a) achieving spontaneous-sounding dialogue; and b) agreeing on a final version when writing a short piece of dialogue in groups.

To learn about the importance of reading dialogue aloud to ascertain that it sounds spontaneous and can be easily interpreted by actors.

To practise the use of specific conversational routines in the TL.

To gain awareness of potential restrictions (e.g. use of dialect) and of the linguistic features that reinforce orality and spontaneity in the TL.

Grouping: 3–4 students.

Approximate timing: 45–60 minutes.

Material:

Description of a scene from a clip in the SL.

Video clip in the SL to be played without sound.

Software to record dialogue (optional).

Steps:

Students receive a document with the description of a short audiovisual scene and are asked to read it individually. An example taken from the popular TV series Friends (David Crane, Marta Kauffman, 1994–2004) has been included in for illustration purposes.

If tutors consider it necessary, for instance, to illustrate the age or look of the characters and for students to be able to make a more informed decision regarding how they will address each other, the scene can be played to the class without sound.

Students are divided into groups of three or four and are asked to write a dialogue in their TL together, reflecting what is going on in this scene, along the lines of a creative writing/scriptwriting exercise. They should be encouraged to use linguistic features that are both typical of spontaneous conversation and acceptable in audiovisual dialogue.

As they write their dialogue in groups, students are encouraged to interpret the lines and to introduce changes accordingly, if a specific passage is difficult to read or does not sound like natural conversation.

Students share their work with the rest of the class, depending on the setting and students’ needs. If all students share the same language, they could be asked to represent the scene they have come up with in front of the class. Alternatively, they could be asked to record their text using relevant software like Audacity, either in class or at home, and share it with the rest of the class through the VLE platform/tool used. Recording their own lines is an excellent way for students to ascertain if the dialogue they have created sounds spontaneous and can be easily interpreted by actors. If students do not have the same language combination, they could still share their creations, either in written or audio form, as well as reflect on the theoretical aspects they have learnt from this exercise.

This activity can be followed by a discussion which could broach not only aspects related to orality markers in the TL (e.g. the use of conversational routines or forms to address people from a different generation) and their appropriateness (e.g. dialect, slang, relaxed phonetic articulation), but also culture-specific aspects. For instance, the use of the description in can lead to interesting discussions on the term ‘baby shower’ and similar traditions in different cultures.

Provided that students are not translating into English, a logical way to follow up this activity would be to ask students to translate the given clip, as described in Activity 4 below. This would consolidate their understanding of the restrictions characterising dubbing and give them an opportunity to reflect on how notions such as adaptation, fitness for purpose and fidelity to the source text (ST) are materialised in a dubbing context. As such, undertaking Activity 4 after Activity 3 might encourage students to use some orality markers in the TL because they are fit for purpose and not necessarily because they appear in the ST.

Table 2. Description of the opening scene of episode 190 from the TV series Friends

3.4. Activity 4. Translating spontaneous-sounding dialogue into the TL for dubbing purposes

Aims:

To develop the linguistic skills necessary to produce a dubbed version of a spontaneous-sounding dialogue.

To reflect on cultural differences between the source and target cultures and how these are materialised through text and image.

To learn about the importance of reading dialogue aloud to ascertain that it sounds spontaneous, can be easily interpreted by actors and synchronised with the original.

To practise the implementation of dubbing conventions.

To gain a deeper awareness of which linguistic features reinforce orality and spontaneity in the TL.

Grouping: Individual, in small groups.

Approximate timing: 90–120 minutes plus 45 minutes (revision task to undertake as homework).

Material:

Short clip in the SL (2–3 minutes; 300–400 words).

Post-production script of the clip in the SL.

List of dubbing conventions to be followed.

Software to record dialogue (optional).

Steps:

Students translate the clip provided into their TL with the support of the post-production script, making sure their translation contains features typical of spontaneous conversation. They should pay attention to conversational routines and follow specific dubbing conventions for their TL, which would have been discussed in class previously.

Depending on the length of the course, students could be asked: 1) to use a text editor such as MS Word to type their translation as they would do with a written translation; 2) to use a given template or format in MS Word; 3) to divide the dubbing script into takes accordingly and using macros if relevant (Cerezo-Merchán et al. Citation2016); or, 4) to use a cloud-based platform such as ZOOdubs (www.zoodigital.com/services/localize/dubbing) or VoiceQ Cloud (www.voiceq.com/voiceq-cloud) and adopt different roles (project manager, translator, dialogue writer, reviewer) in order to simulate a real dubbing project.

Once finished, students could be asked to record their translation to ensure that its length is appropriate to maintain isochrony and that it sounds natural. Recording their own lines would allow them to understand the importance of dubbing synchronies and the challenges of complying with them.

Students could also be asked to review the translation of one of their peers, to make suggestions as regards the use of orality markers and return these suggestions in a relevant format. This could be an opportunity to reflect on the challenges of reviewing someone else’s work, as well as to introduce existing marking criteria so that students become familiar with these and understand how their work will be assessed at a later stage.

3.5. Activity 5. Writing natural-sounding dialogue as collaborative work

Aims:

To understand the changes that translated scripts undergo and the role of the different part-takers in the dubbing process.

To evaluate the changes implemented as regards the use of orality markers during the dubbing process.

To draw parallelisms between dialogue writing for original productions and for dubbing purposes.

To reflect on key notions such as synchronisation and improvisation in dubbing.

Grouping: In pairs.

Approximate timing: 30 minutes.

Material:

Written excerpts containing both translated-only dialogue and translated dialogue after synchronisation.

Steps:

Students receive a document containing the translated and synchronised dialogue of a dubbed scene. The process of dubbing should have been discussed in advance and students should be aware that, once translated, the text needs to be adapted and synchronised. This can be done by the translator, if they have received relevant training, or by a different professional, known as the dialogue writer or adapter. Modifications to the synchronised version might also be introduced while recording the new lines. Students will thus be asked to compare all these versions or textual sources of the ‘dubbing black box’ (Richart-Marset Citation2013). An illustrative example borrowed from Baños (Citation2020) is included in . Tutors can resort to existing publications (De los Reyes Lozano Citation2016; Richart-Marset Citation2013; Zanotti Citation2014) or contact professional translators or dialogue writers to source this material, though this might be an arduous task.

Students work in pairs to identify the changes introduced during the different dubbing phases, paying particular attention to orality markers. In the example provided in , the focus could be on new orality markers inserted and/or removed in the dialogue writing phase (discourse markers, use of language- and/or country-specific dubbing symbols such as ‘DE-FP’Footnote1 in Spain, instead of ‘(OFF)’, etc.), as well as on debating the reasons that could have motivated such changes (synchronisation, dubbing conventions).

Students share their findings with the rest of the class and the tutor moderates further discussion on topics such as the likely reasons behind the changes to the work submitted by translators and the collaborative authorship of dubbing scripts.

Table 3. Example of different versions in Spanish from Ocean’s Eleven scene 12

3.6. Activity 6. Compilation and interrogation of monolingual corpora

Aims:

To acquire relevant instrumental competences to complement the resources used to carry out background research within the translation process.

To acquire new strategies to justify translation decisions, especially those related to usage and the naturalness of a particular term/expression in the TL.

Grouping: Groups of 2–3 students.

Approximate timing: 30–45 minutes for corpus interrogation (corpus compilation to be undertaken at home).

Materials:

Monolingual corpus.

Corpus management tool such as AntConc (www.laurenceanthony.net/software/antconc) or SketchEngine (www.sketchengine.eu).

A short exercise for corpus interrogation with a focus on orality markers.

Steps:

In preparation for the translation of a short scene for dubbing purposes (see Activity 4), students source a small number of parallel texts in the TL, belonging to the same genre as the text being translated. If students are asked to translate a scene from a sitcom, they should collect scripts, and their corresponding clips, from sitcoms produced in their TL.

Students work in groups and agree beforehand on the criteria to be used for the selection of texts (authorship, number of texts, publication date, language variety, etc.). Ideally, each student should collect at least two short texts so that enough results can be obtained. If constrained by time, tutors can provide the corpus to students, although the learning process of compiling a small ad hoc corpus in groups can be very fruitful.

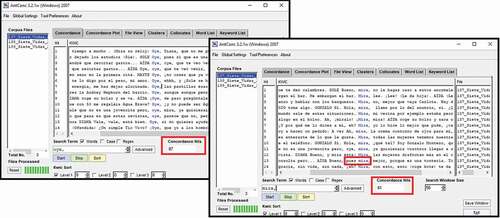

Once the corpus has been compiled, and before undertaking the translation of the clip, students are asked to complete a short exercise to interrogate or query the corpus and obtain information as regards the use of orality markers. includes examples of questions that could be asked throughout this process.

Table 4. Potential questions to guide the students’ interrogation of the monolingual corpus compiled

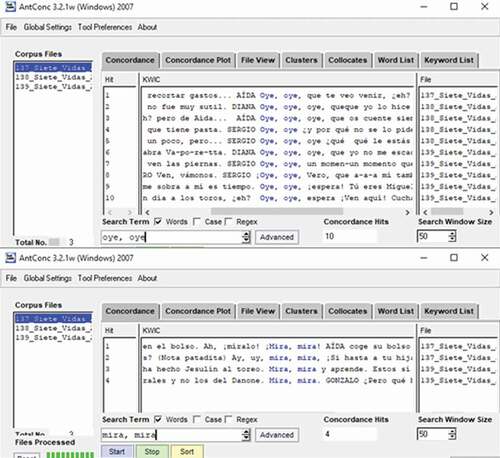

For example, when working from English into Spanish, the first question from could prompt students to look for the discourse markers oye [listen] and mira [look] in Spanish and to learn more about how they are used in fictional dialogue. As shown in , which presents results using the corpus management tool AntConc 3.2.1, oye is used slightly more often than mira in the corpus compiled, which consists of three episodes of the Spanish TV series Siete Vidas (120 minutes and 25,000 words approx.).

Figure 2. Concordance results of discourse markers oye and mira in a corpus of the Spanish TV series Siete Vidas

While both discourse markers are used frequently at the beginning of the sentence, they can also be used mid-sentence and, more importantly, combined with other discourse markers (oye, mira or pues mira). The results of the concordance search also show that they can both be repeated in the same sentence, in succession, for emphasis (oye, oye and mira, mira), as shown in . These examples illustrate the usefulness of ad hoc monolingual corpora when working with audiovisual texts and investigating the usage of orality markers in the TL.

Figure 3. Concordance results of oye, oye and mira, mira in a corpus of the Spanish TV series Siete Vidas

To answer these questions students should be familiar with corpus management tools, thus requiring additional time. Yet, there are very intuitive and free tools such as AntConc or SketchEngine, which should make this process less cumbersome for tutors and students.

Students are asked to reflect on the usefulness of the monolingual ad hoc corpus compiled for the translation of the clip chosen for dubbing purposes.

3.7. Activity 7. Compilation of bilingual corpora and translation of dubbing script using a CAT tool

Aims:

To acquire relevant instrumental competences that complement the documentation resources used in the translation process.

To acquire new strategies to justify translation decisions, especially those related to usage and the naturalness of a particular term/expression in the TL.

To reflect on the suitability of existing CAT tools to translate audiovisual texts for dubbing purposes.

To explore new features recently introduced in CAT tools to translate audiovisual texts.

Grouping: Individual, groups of 2–3 students.

Approximate timing: 45–60 minutes for translation using a CAT tool (corpus compilation to be undertaken as homework wherever included in the task).

Materials:

Short clip in the SL (2–3 minutes; 300–400 words).

Post-production script of the clip in the SL.

List of dubbing conventions to be followed.

Bilingual corpus, translation memory (TM) file.

CAT tool (memoQ, SDL Trados Studio).

This activity can be integrated with the translation of a short scene for dubbing purposes, illustrated in Activity 4 above, and explained below.

Steps:

Students use a CAT tool to complete the translation of a short clip (see Activity 4). Depending on the time available and the students’ previously acquired competence using CAT tools, they could be asked to create a TM (i.e. a database containing source segments and their corresponding translation paired up to be consulted at a later stage when translating similar material) from existing translations (by means of text alignment). For instance, in preparation for Activity 4, students could be given the ST and target text (TT) of one or two previous episodes of the TV series Friends, to be aligned and saved in .tmx format. To undertake the task of creating a TM file suitable for the completion of this activity, students could work individually or in groups. Popular CAT tools such as memoQ or SDL Trados Studio provide users with alignment features with a high degree of automation, making this task possible. Otherwise, students can be provided with the .tmx file already aligned by the tutor. Sourcing the materials should not be problematic in the case of popular TV series, which are also more suitable than other entertainment productions to be translated with TM tools, given their continuity and the need for consistency across episodes.

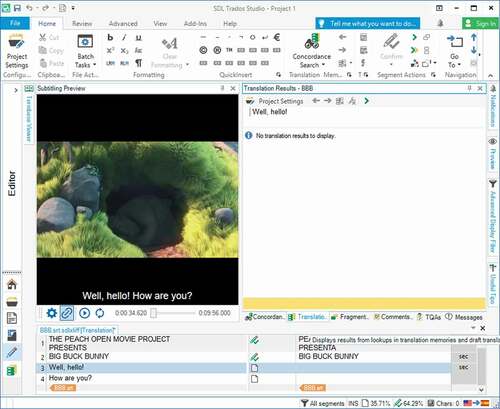

Students translate the clip provided into their TL by importing and opening the ST in a CAT tool such as SDL Trados Studio or memoQ. As discussed below, these CAT tools provide support, albeit limited, to translate subtitle files and therefore to work with audiovisual material and not only with the text to be translated.

Students should make sure their translation contains features typical of spontaneous conversation, paying particular attention to conversational routines, and follow specific dubbing conventions for their TL, which would have been previously discussed in class. The tutor could moderate a discussion on the impact that translating with CAT tools may have on students’ creativity when creating natural-sounding dialogue exchanges in the TL.

Students should be made aware that the purpose of using CAT tools in AVT is not solely related to consistency or terminology mining, as is often the case when dealing with scientific and technical translation, but rather to find out how specific orality markers have been translated previously by professional translators and deciding whether these solutions are also appropriate in the case at hand.

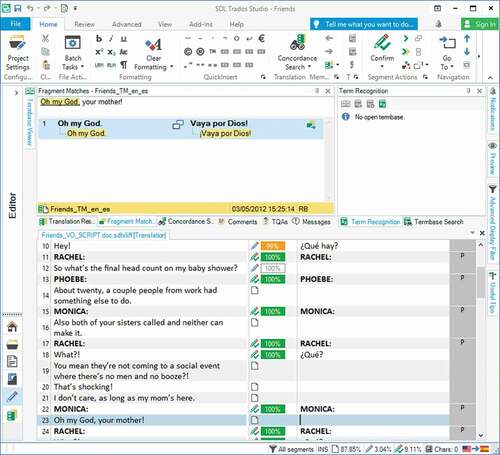

In addition to the TM system’s feature that allows to automatically insert the translation provided for a source segment that is already saved in the database, such as character names or common sentences like ‘What?’ or ‘I don’t know’, some programmes can also identify if specific phrases are already stored in the TM. Potential results that could be obtained are shown in in the case of SDL Trados Studio 2019, where the ST in .docx format (a short extract from the opening scene of episode 190 from the TV series Friends) was pre-translated using a TM containing a previously translated episode (406 segments or translation units), providing both exact (100%) and fuzzy (99%) matches, and where suggestions are also made in the form of so-called fragment matches.Footnote2

In a similar vein, concordance searches could be carried out for ideas to deal with interjections like ‘Oh my God!’. As shown in , such a search can suggest solutions that might not have occurred to students whilst translating from scratch (¡Por Dios! or simply ¡jo!) which are more natural-sounding in the TL than counterparts closer to the original, such as ¡Oh, Dios mío! Nonetheless, the latter is also found in the corpus as it is frequently heard in Spanish dubbed versions, and also read in subtitles.

Figure 5. Concordance searches undertaken using SDL Trados Studio 2019 to translate for dubbing purposes

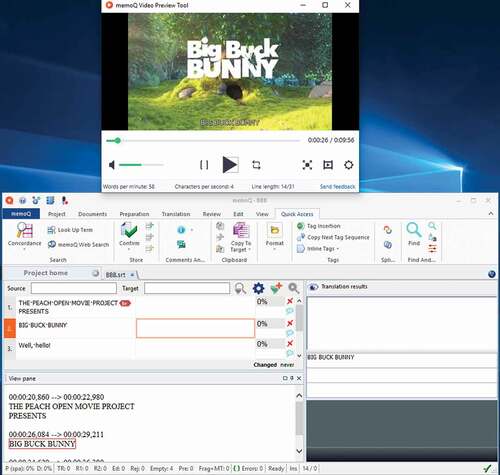

CAT tools such as memoQ allow translators to use monolingual and bilingual corpora as additional resources (i.e. memoQ’s LiveDocs), making it possible to integrate this activity with Activity 6 above and combine the use of both bilingual and monolingual corpora.

Once finished, students could be asked to record their translation to ensure that its length is appropriate and that it sounds natural. In order to do this, they will have to use additional software, as the existing versions of SDL Trados Studio or memoQ do not support audio recording.

Students could also be asked to review the translation of one of their peers within the relevant CAT tool, make suggestions as regards the use of orality markers and return these suggestions using the features provided by the software (insertion of comments, bilingual review feature in SDL Trados Studio, etc.).

As discussed earlier, this activity could be set up as part of a project, being the perfect example of how ‘situated learning experiences that showcase cutting-edge technologies’ can be integrated in the dubbing classroom to boost ‘students’ employability and resilience in a mercurial industry heavily driven by technological changes’ (Bolaños-García-Escribano and Díaz-Cintas Citation2019, 221). Yet, it is worth noting that the support provided by current TM technology for the translation of audiovisual material is very limited and often restricted to subtitle files only. In order to navigate the video and textual content at the same time, while using the CAT tools discussed above for dubbing purposes, a subtitle file with the relevant time codes would be needed. While producing a dubbing script from a subtitle file is not impossible, this workflow is far from ideal and not in line with current industry practices (Spiteri-Miggiani Citation2019). Another downside is that separate apps and plug-ins need to be installed in addition to the relevant CAT tool. For instance, memoQ currently requires the download and installation of a separate app called memoQ Video Preview tool, which runs separately from the main tool ().

SDL Trados Studio also requires the download and installation of the Studio Subtitling plugin. Unlike in memoQ, in SDL Trados Studio it is possible to open the video within the main tool, previewing subtitles and translating these in the Editor window, as shown in .

Figure 7. Subtitle file opened in SDL Trados Studio 2019 after installing the Studio Subtitling plugin

This lack of support for dubbed audiovisual material stands in stark contrast with the increase of programmes needing translation, especially online, with web video traffic predicted to account for 82% by 2022 (Cisco Citation2020), as well as with the so-called ‘dubbing revolution’ (Roxborough Citation2019, online) spearheaded by Netflix. This could be an interesting debate to bring to the classroom, as is the potential impact of TM tools on orality and naturalness. As discussed in the literature, the segmentation imposed by these tools and their rigidity may affect the quality of the translation in terms of its naturalness (Bowker Citation2002). Translators have reported that using CAT tools can make their job less creative and more segment-oriented (Christensen and Schjoldager Citation2016), contribute to error propagation and make them ‘lazy and increasingly passive’ (LeBlanc Citation2013, 7). Recent research has nevertheless demonstrated that the impact of using TM tools on linguistic interference depends on a wealth of factors, and that while it can lead to more interference in some linguistic and textual categories, results might be the opposite for others (Martín-Mor Citation2019). In light of these findings, it is our role as educators of future generations of AVT professionals to make students aware of these and related topics, and to invite them to reflect on the relationship established between humans and machines in a critical yet realistic manner.

4. Final remarks

The previous section has provided an overview of some of the activities that could be exploited in the dubbing classroom, with a focus on sub-competences relevant for the achievement of credible and natural-sounding dialogue in dubbing. In doing so, professional and pedagogic aspects have been taken into consideration, as well as the specificities of the language of dubbing and of dubbing as an AVT mode. While some activities mirror exercises often resorted to in other disciplines (creative writing or scriptwriting in Activity 3) and types of translation (specialised translation in Activity 7), they all tackle challenging aspects dubbing students will face when they work in a professional environment.

Although these proposals have been designed in a very specific context (technology-driven curriculum in a UK higher-education institution), they could be easily adapted to different settings and students’ needs. Due to space constraints, aspects such as how these activities, designed mainly to provide formative feedback, are integrated in the wider assessment strategy have not been discussed. The same applies to how these activities would lead to the acquisition of general and specific competences and the attainment of relevant learning outcomes. These are areas to be further developed, especially given that the topic of assessment in AVT is largely unexplored in the existing literature and that quality assessment is a thorny issue. In particular, it would be interesting to reflect on how professional assessment practices could be transposed and successfully implemented in the dubbing classroom as far as the language of dubbing is concerned, and how to establish an appropriate balance between pedagogical approaches and professional practices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. The symbol DE (De Espaldas), used in many dubbing studios in Spain, means that Frank is initially with his back to the camera and then out of shot (FP: Fuera de Plano in Spanish).

2. TM systems compare the new source segments to be translated with the information available in the TM and present the user with different types of matches. While an ‘exact match is 100% identical to the segment that the translator is currently translating, both linguistically and in terms of formatting’ (Bowker Citation2002, 95), a fuzzy match ‘retrieves a segment that is similar, but not identical, to the new source segment’ (ibid, 99). TM systems can also compare fragments within a segment and therefore retrieve sub-segment or fragment matches. In Figure 4, for instance, when translating the segment ‘Oh my God, your mother!’, the first part of the segment, ‘Oh my God’ is retrieved as a fragment match.

References

- Baños, R. 2014a. “Orality Markers in Spanish Native and Dubbed Sitcoms: Pretended Spontaneity and Prefabricated Orality.” Meta 59 (2): 406–435. doi:https://doi.org/10.7202/1027482ar.

- Baños, R. 2014b. “Insights into the False Orality of Dubbed Fictional Dialogue and the Language of Dubbing.” In Media and Translation: An Interdisciplinary Approach, edited by D. Abend, 75–95. London: Bloomsbury.

- Baños, R. 2018. “Technology and Audiovisual Translation.” In An Encyclopedia of Practical Translation and Interpreting, edited by C. Sin-wai, 3–30. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press.

- Baños, R. 2020. “Insights into The Dubbing Process: A Genetic Analysis of the Spanish Dubbed Version of Ocean’s Eleven.” Perspectives 29 (1): 879-895. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2020.1726418.

- Cerezo-Merchán, B., F. Chaume, X. Granell, J. L. Martí Ferriol, J. J. Martínez Sierra, A. Marzà, and G. Torralba Miralles. 2016. La traducción para el doblaje en España: Mapa de convenciones. Castelló de la Plana: Universitat Jaume I.

- Bolaños-García-Escribano, A., and J. Díaz-Cintas. 2019. “Audiovisual Translation: Subtitling and Revoicing.” In The Routledge Handbook of Translation and Education, edited by M. González-Davies and S. Laviosa, 207–225. London: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367854850-14.

- Bowker, L. 2002. Computer-Aided Translation Technology: A Practical Introduction. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

- Carter, R., and M. Michael. 1997. Exploring Spoken English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cerezo-Merchán, B. 2018. “Audiovisual Translator Training.” In The routledge handbook of audiovisual translation, edited by L. Pérez-González, 468–482. London: Routledge. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315717166-29.

- Chaume, F. 2007. “Dubbing Practices in Europe: Localisation Beats Globalisation.” Linguistica Antverpiensia 6: 203–217.

- Chaume, F. 2008. “Teaching Synchronisation in a Dubbing Course: Some Didactic Proposals.” In The Didactics of Audiovisual Translation, edited by J. Díaz-Cintas, 129–140. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.77.13cha.

- Christensen, T. P., and A. Schjoldager. 2016. “Computer-Aided Translation Tools – The Uptake and Use by Danish Translation Service Providers.” The Journal of specialised translation 25: 89–105.

- Cisco. 2020. Cisco Visual Networking Index: Forecast and Trends, 2017–2022 White Paper. https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/solutions/collateral/executive-perspectives/annual-internet-report/white-paper-c11-741490.html.

- De los Reyes Lozano, J. 2016. “Genética del doblaje cinematográfico. La versión del traductor como proto-texto en el filme Rio.” Linguistica Antverpiensia 14: 149–167.

- Duro, M. 2001. “‘Eres patético’: El español traducido del cine y de la televisión.” In La traducción para el doblaje y la subtitulación, edited by M. Duro, 161–185. Madrid: Cátedra.

- Goldsmith, J. 2019. “Netflix Wants to Make Its Dubbed Foreign Shows Less Dubby.” In The New York Times, July 19. www.nytimes.com/2019/07/19/arts/television/netflix-money-heist.html.

- González-Davies, M. 2004. Multiple Voices in the Translation Classroom. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Kelly, D. 2005. A Handbook for Translator Trainers: A Guide to Reflective Practice. Manchester: St Jerome.

- LeBlanc, M. 2013. “Translators on Translation Memory (TM). Results of an Ethnographic Study in Three Translation Services and Agencies .” Translation & Interpreting 5 (2): 1–13.

- Martín-Mor, A. 2019. “Do Translation Memories Affect Translations? Final Results of the TRACE Project.” Perspectives 27 (3): 455–476. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2018.1459753.

- Marzà, A., and F. Chaume. 2009. “The Language of Dubbing: Present Facts and Future Perspectives.” In Analysing Audiovisual Dialogue. Linguistic and Translational Insights, edited by M. Pavesi and M. Freddi, 31–39. Bologna: Clueb.

- Matamala, A. 2009. “Interjections in Original and Dubbed Sitcoms in Catalan: A Comparison.” Meta 54 (3): 485–502. doi:https://doi.org/10.7202/038310ar.

- Nornes, M. 2007. Cinema Babel: Translating Global Cinema. Minessota: University of Minnesota Press.

- PACTE Group. 2017. “Conclusions: Defining Features of Translation Competence.” In Researching Translation Competence by PACTE Group, edited by A. Hurtado Albir, 281–302. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/btl.127.

- Pavesi, M. 2018. “Reappraising Verbal Language in Audiovisual Translation: from Description to Application.” Journal of Audiovisual Translation 1 (1): 101–121. doi:https://doi.org/10.47476/jat.v1i1.47.

- Richart-Marset, M. 2013. “La caja negra y el mal de archivo: Defensa de un análisis genético del doblaje cinematográfico.” TRANS 17: 51–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.24310/TRANS.2013.v0i17.3227.

- Romero-Fresco, P. 2009. “Naturalness in the Spanish Dubbing Language: A Case of Not-So-Close Friends.” Meta 54 (1): 49–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.7202/029793ar.

- Roxborough, S. 2019. “Netflix’s Global Reach Sparks Dubbing Revolution: ‘The Public Demands it.” The Hollywood Reporter, August 13. www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/netflix-s-global-reach-sparks-dubbing-revolution-public-demands-it-1229761.

- Ruiz-Gurillo, L. 2013. “Narrative Strategies in Buenafuente’s Humorous Monologues.” In Irony and Humor. From Pragmatics to Discourse, edited by L. Ruiz-Gurillo and M. B. Alvarado-Ortega, 107–140. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.231.

- Sánchez-Mompeán, S. 2019. “Prefabricated Orality at Tone Level: Bringing Dubbing Intonation into the Spotlight.” Perspectives 28 (2): 284–299. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2019.1616788.

- Spiteri-Miggiani, G. 2019. Dialogue Writing for Dubbing: An Insider’s Perspective. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Yampolsky, M. 1993. “Voice Devoured: Artaud and Borges on Dubbing.” October 64: 57–77.https://doi.org/10.2307/778714

- Zanotti, S. 2014. “Translation and Transcreation in the Dubbing Process: A Genetic Approach.” Cultus 7: 107–132.

Appendix A.

Sample table summarising key orality markers in English to be used in Activity 1.

The examples featured in these tables have been compiled from a wide range of sources, from real-life conversations to oral texts included in ready-made corpora and monographs on spoken English, such as Carter and Michael (Citation1997).

Phonetic features

Morphosyntactic features

Lexical features